Abstract

CD1a, CD1b, CD1c and CD1d proteins migrate through distinct subcellular compartments of antigen presenting cells and so can be considered to take four separate pathways leading to display of lipid antigens to T cell receptors. This review discusses the intersection of CD1 trafficking and lipid antigen loading mechanisms in cells, highlighting key controversies relating to CD1 gene expression, size mismatches between antigens and CD1 binding clefts and unexpected mechanisms of T cell receptor-based recognition.

Four Pathways of Lipid Antigen Presentation

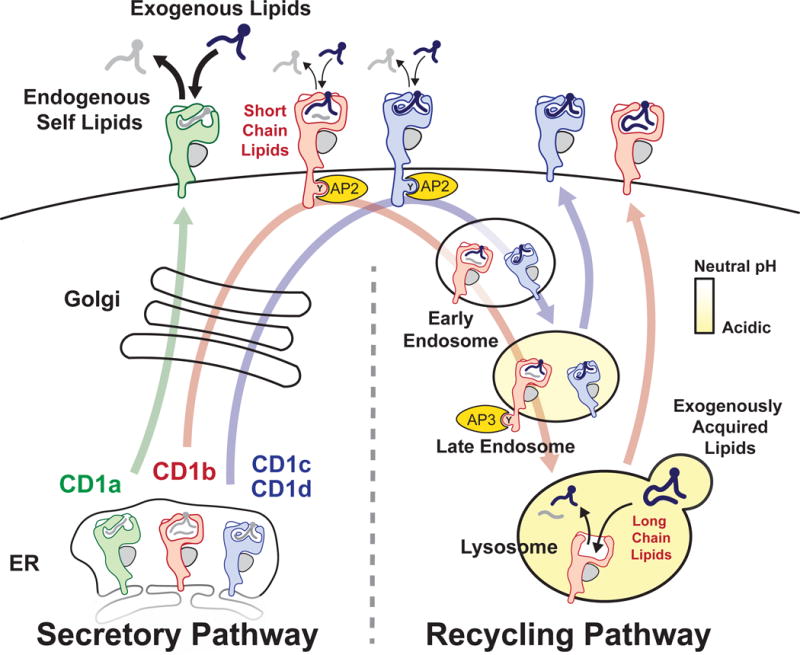

MHC I and MHC II proteins traverse largely separate subcellular pathways to capture peptide antigens, and points of overlap are known as cross-presentation [1]. Likewise, cellular pathways of lipid antigen capture by the four types of human CD1 antigen presenting molecules show both overlap and divergence (Figure 1). CD1a, CD1b, CD1c and CD1d navigate the secretory pathway in a similar manner: nascent CD1 heavy chains fold in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), bind β2 microglobulin (β2m), capture endogenous self lipids and egress the cell surface [2–4]. Thereafter, the mechanisms of lipid antigen capture and trafficking diverge. While at the cell surface, CD1a [5] and CD1c [6,7] readily capture exogenous lipids, but CD1b [8,9] and CD1d [10,11] do this to a lesser degree. All four protein types enter the endosomal network, but do so using distinct mechanisms. CD1a remains predominantly at the surface at steady state and undergoes an inefficient and shallow recycling pathway mediated by yet to be identified mechanisms of guidance [12–14]. CD1b, CD1c and CD1d traffic through endosomes using tyrosine residues in their cytoplasmic tails to bind to the μ-subunits of adaptor protein complexes (AP). Human CD1d and CD1c bind AP-2, targeting them for delivery to early and late endosomal compartments [6,7]. The particular tyrosine motif present in human CD1b (and mouse CD1d) mediates binding to AP-2 and AP-3, which provides strong redirection to late endosomes and lysosomes [8,11,15].

Figure 1. Subcellular pathways of lipid antigen capture by human CD1 proteins.

All four types of human CD1 proteins bind endogenous self lipids and egress to the cell surface through the secretory pathway [3,4]. Exchange of lipid cargo predominantly occurs at the surface for CD1a [5,12] and has been observed for CD1c [6]. CD1b, CD1c and CD1d proteins enter the endosomal network for specialized loading reactions [6–8,10] prior to recycling to the surface for contact with TCRs. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; AP, adaptor protein complex.

The extent to which each CD1 protein recycles through the endosomal network correlates with the degree to which an acidic pH is needed for lipid antigen capture. CD1c and CD1d capture antigens less efficiently when their recycling motifs are altered and more efficiently when at an acidic pH in loading assays [6,7,10]. CD1b has higher [8] or absolute requirements for an acidic pH when loading lipids, especially long chain lipids [9]. Acid releases interdomain tethers and otherwise denatures CD1 proteins to provide access to their clefts [16], allowing the formation of durable CD1-lipid complexes. Acid also permits the activity of acid-dependent proteases like cathepsins, which cleave prosaposin to activate this and other lipid transfer proteins [17–19]. Thus, the modern view is that the four CD1 proteins initially operate on the same track for capture of endogenous self lipids, but then each of the four human CD1 protein types fan out to distinct locations within the endosomal network for capture of exogenous lipids (Figure 1). Based on this widely accepted framework, we highlight gaps in knowledge and controversies related to how CD1 and lipid trafficking pathways intersect to form CD1-lipid antigen complexes.

CD1 gene regulation

While differing subcellular localization provides the key basis for considering four distinct CD1 pathways, a clear, but less widely recognized difference among the protein types relates to differing patterns of gene regulation. The co-discoverers of the human CD1 locus identified separate group 1 (CD1A, CD1B, CD1C) and group 2 (CD1D) genes based on differences in sequence homology [20]. This classification remains widely used, even though crystallization of human and mouse CD1 proteins did not identify CD1d as the most distinct in its three dimensional structure [21–24]. (Instead, CD1b is the structural outlier, as discussed below.) However, group 1 and 2 CD1 genes do differ in the extent to which they are regulated via inducible transcription mechanisms. The group 2 protein, CD1d, is constitutively expressed in blood and peripheral tissues, including B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells (DC) and epithelia. The group 1 proteins are not usually constitutively expressed in the blood or on epithelia [25], but instead show stimulus-dependent, inducible expression in response to GM-CSF [26] or bioactive IL-1β [27]. Group 1 CD1 protein expression on the surface of myeloid cells is transcriptionally regulated [28], distinct from the surface redirected trafficking of preformed stores of MHC II proteins [29,30]. Group 1 induction at the level of gene expression can be an all or nothing type mechanism to create competent lipid antigen presenting cells (APCs) [26,28]. Thus, inducible gene regulation is a key difference between group 1 and 2 CD1 proteins.

This overlooked perspective offers implications for biological response. First, the role of bioactive IL-1μ in conferring functional lipid antigen presentation implies that rapidly acting innate receptors, including Toll-like receptor 2 and the NALP-3 inflammasome, act upstream to control the emergence of some types of group 1 CD1 lipid antigen presentation over a days-long period [27,28]. The extreme restriction of expression of certain CD1 proteins, especially CD1b, on unactivated cells in the periphery creates a situation in which the appearance of CD1 proteins on APCs could be as important as the appearance of lipid antigens in triggering an immune response. Altered group 1 CD1 gene expression occurs in humans with lepromatous leprosy and tuberculosis infection [31,32], suggesting relationships between CD1 induction and disease. Yet, even basic information about promoters, enhancers and other mechanisms of CD1 gene regulation is lacking. Future studies of transcriptional control could provide basic insight into DC maturation as well as cell-type specific mechanisms by which CD1a is highly expressed on Langerhans cells and CD1d and CD1c appear on marginal zone B cells [25].

Early events in lipid capture

Lipids stabilize CD1 structures as they fold in vitro [22], and CD1 capture of phosphatidylcholine occurs in the ER [3]. However, the earliest mechanisms of self lipid capture in the ER have not been broadly studied so even basic questions remain unanswered. Do newly folded CD1 proteins capture few or many types of lipids? Do CD1a, CD1b, CD1c and CD1d capture the same or different profiles of lipids as they egress together through the secretory pathway? Do CD1 proteins use unguided mechanisms to capture nearly any self lipid or instead are they directed to capture certain types of self lipids using mechanisms that are the equivalent of tapasin or Class II invariant chain peptide (CLIP)?

The Donor Substrate Problem

How do water insoluble, self aggregating ligands move from their normal sites in fatty deposits or membranes and disaggregate to generate CD1-lipid complexes with one to one stoichiometry? Part of the answer involves lipid transfer proteins. Deletion of prosaposin or the individual saposin proteins blocks lipid antigen presentation by cells [17–19]. Saposin C and CD1e promote local disorder in membranes so that lipid monomers rise from membranes for interaction with glycosidases or true lipid carriers like saposin B [33–35]. Apolipoprotein E [36] and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein [37,38], which are most well known for their roles in generating apolipoprotien particles, also control CD1 function. Despite these advances, a step-wise picture of how lipids exit their aggregated states in sebum [39], adipocytes [40], apolipoproteins [36] and membranes to become antigens that reside as monomers in the CD1 cleft is not broadly understood. Cartoons of CD1 antigen processing depict lipid transfer proteins plucking lipid monomers for transport across the cytosol. Another plausible mechanism was suggested by an early study showing that CD1b localizes asymmetrically to one membrane in multi-lamellar lysosomes [41]. Keeping in mind that lysosomes [41] and Langerhans cell Birbeck granules [42] also have folded membranes, CD1-containing membranes might directly appose antigen-containing membranes so that the loading event is simply a flip from an opposing membrane into the cleft.

Elusive Antigen Motifs

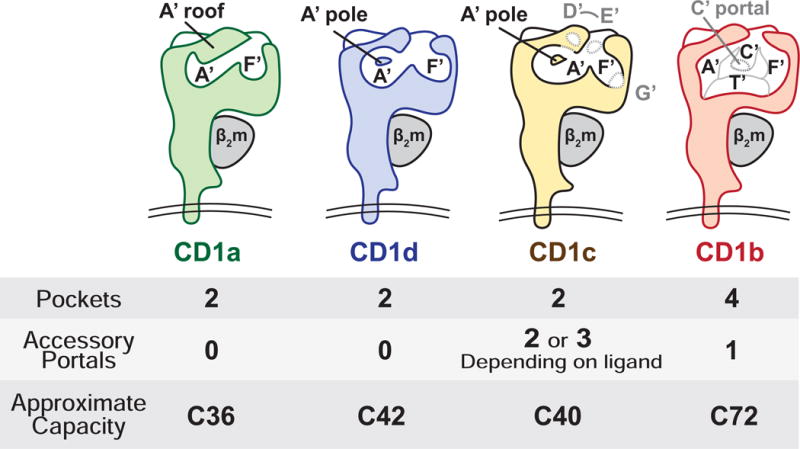

Efforts to map peptide epitopes in vaccination and disease are governed fundamentally by the limitations on antigen size and shape of MHC grooves. The closed ends on MHC I restrict binding to nonamer peptides, whereas the open-ended groove of MHC II binds longer peptides with ragged ends. Further, key residues at named positions 1 through 9 of the peptide make specific charge-charge or hydrogen bonding interactions with the MHC I groove, so sequence specific motifs are known. Now that the size and shape of the clefts present in the four types of human CD1 antigen presenting molecules are known [22–24,43] (Figure 2), do they likewise impose size or chemical motifs on the types of ligands bound? Because CD1 genes are non-polymorphic, any motifs identified would presumably apply to all humans.

Figure 2. CD1 antigen binding cleft architecture is defined by named pockets (black) and accessory portals (grey).

CD1 proteins form named pockets (black letters) and portals (grey letters). All CD1 proteins have an F’ portal through which antigens protrude for TCR contact. Some CD1 proteins have accessory portals, which are thought to allow antigens to protrude laterally from the cleft. CD1c stands out as having D’, E’, and G’ accessory portals [24], which confer structurally flexibility, allowing the α1–α2 superdomain to rearrange upon ligand binding [46]. Whereas other CD1 proteins have two pockets, CD1b has four named pockets (A’, F, C’, T’) and the largest interior capacity to display the longest lipids [22,52].

The clefts present in MHC proteins are known as ‘grooves’ because no surface covers the top of the cavity. The clefts of CD1 proteins however are substantially covered by structures known as A′ roofs, which form cave-like cavities with a defined molecular volume. CD1a, CD1c, and CD1d have two pockets, known as A′ and F′, which are analogous to the A and F pockets in the MHC I binding groove [44]. Clefts present in these three proteins are somewhat similar in volume and generally capture lipids with an overall chain length of C36–42 [22–24,43]. However, the shape and interconnectedness of A′ and F′ pockets differ (Figure 2). In CD1c and CD1d, the A′ pocket is a toroid that encircles a pole (formed by residue F70) [24,43]. Lipids can traverse this donut-shaped cavity in a clockwise or counterclockwise direction [45]. In CD1a, the A′ toroid is truncated so that it is more like a bent tube [23]. CD1c adopts different conformations depending on ligands captured [46]. Thus, although similar in volume, CD1a, CD1c and CD1d could plausibly capture differing lipid types. CD1b is the clear structural outlier in the human CD1 system. Its large cleft is comprised of four interconnected pockets: A′, F′, C′ and T′ [22], which can bind larger lipids up to C80 in length [9,47].

Despite clear architectural differences, motifs that would clearly distinguish the types of lipids bound by CD1a, CD1b, CD1c and CD1d have been slow to emerge. Sulfatide can be presented by each of the four human CD1 types [48], and eluents from cellular CD1 proteins show at least somewhat similar patterns of sphingolipid and phospholipid release [3,39,49]. One possibility is that the non-specific nature of hydrophobic interactions between alkane chains and the hydrophobic residues that line the interior of CD1 cleft render the architectural differences among the four CD1 proteins moot. However, recent studies hint that the spectrum of self lipids captured in cells is much more complex than previously thought [50], so the failure to identify motifs might simply result from insufficient sampling of the ligand repertoire. One type of size motif is established: CD1b captures foreign lipids that are much larger (C54-C82) than those found in association with other CD1 proteins [9,47,51,52]. However, comparatively large self lipids have not been detected, raising basic questions about endogenous ligands for CD1b.

The CD1b Size Problem

Which common self lipid could fill a cleft with the capacity to bind lipids up to C80 in length? Most membrane phospholipids and sphingolipids have two fatty acyl chains of ~ C36 in combined length and are therefore much too small. C95 dolichols or C60 triacylglycerides might be candidates, but they have not emerged as prominent ligands. One study suggests that the molecular size of all ligands eluted from CD1b is not larger than those bound by CD1a, CD1c or CD1d [50]. An unproven but attractive hypothesis to explain the mismatch between CD1b cleft volume with lipid anchor size is altered stoichiometry: the large CD1b groove might bind two lipids at once. Early crystallization studies showed that two or more lipids can be eluted from CD1b during protein refolding in the presence of bacterial lipids [22,53]. These studies suggest a two for one exchange mechanism, whereby two small self lipids are initially captured in the secretory pathway are subsequently released to capture one large bacterial lipid in the recycling pathway [50,53]. As a variation on this theme, one small self lipid might easily be ejected at neutral pH while at the cell surface, but ejection of both self lipids might require acidic conditions in lysosomes. This hypothetical mechanism might explain the curious findings that CD1b can capture small (C32) but not large (C80) lipids at the cell surface and that low pH removes the size selectivity of lipid capture [9] (Figure 1). However, most evidence for this mechanism is derived from artificial methods of lipid loading used in crystallography studies. The number and size of lipids captured by cellular CD1b proteins during natural loading reactions and the ejection process of self lipids have not been solved experimentally.

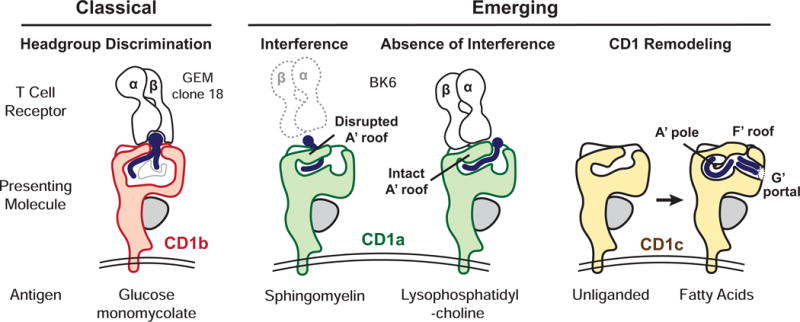

Absence of Interference

CD1-lipid complexes are recognized by αβ or γδ TCRs [26]. The classical mode of CD1-antigen recognition can be described as head group discrimination. The antigen’s alkyl chains are inserted within the CD1 binding cleft, while the carbohydrate, phosphate, sulfate or peptide headgroups protrude above the surface for contact with the TCR (Figure 3). This model derives from early studies showing TCR fine specificity for carbohydrate groups of glucose monomycolate (GMM) and α-galactosyl ceramide [54,55]. This model was ruled in for CD1d in 2007 [56], and the first ternary crystal structure of CD1b-glycolipid-TCR was solved during the past year [52]. Here the TCR α and β chains surround the glucose residue of GMM like tweezers, while also making contacts with CD1b. The headgroup discrimination model has parallels to the usual mode of TCR-peptide-MHC model in that the TCR contacts both antigen and antigen presenting molecule, showing high specificity for both. This model undoubtedly controls T cell responses to many amphipathic lipids and was thought to be a general explanation for antigen recognition in the CD1 system.

Figure 3. Three Models for CD1 Antigen Display.

In Head Group Recognition the TCR binds directly to the protruding carbohydrate present in α-galactosylceramide bound to CD1d [56] or glucose monomycolate bound to CD1b (shown) [52]. In Absence of Interference, the autoreactive BK6 TCR contacts the CD1a A’ roof but not the lysophosphatidylcholine ligand (right), which is bound to CD1a. Sphingomyelin however interferes with the CD1a A’ roof and blocks TCR binding (left) [57]. While unliganded CD1c appears collapsed, loading with fatty acid lipids causes extensive CD1 Remodeling in regions that are predicted to act as TCR recognition surfaces [46].

However, the identification of tissue-derived CD1a-presented autoantigens [39] and the first CD1a-lipid-TCR structure [57] provided a new and unexpected model, termed absence of interference. Squalene and free fatty acid antigens lack large hydrophilic groups that are normally the basis of head group recognition. Further, mass spectrometry detected hundreds of lipids in the eluate from CD1a-lipid-TCR complexes, suggesting that lipids diverse in structure broadly permit TCR-CD1a association. This surprising finding was explained by a ternary crystal structure showing that an autoreactive TCR bound the CD1a A′ roof without contacting the lipid carried by CD1a. In contrast, certain lipids with large headgroups like sphingomyelin block the TCR contact surface on the A′ roof of CD1a [39,57]. Thus, opposite to the predictions of the head group discrimination model, small lipids lacking head groups provided ‘absence of interference’ for CD1a-TCR binding. The key to this new model is that lipids emerge from right side of the cleft and the TCR binds to the left side of CD1a (Figure 3). In fact, the left-right asymmetry of CD1, which forces the ligand to emerges from the F′ portal on the right side of the platform represents a fundamental difference between the CD1 and MHC system [58]. MHC proteins position peptides symmetrically on the platform so peptide is present on the left and right.

CD1 Remodeling

A third model for TCR recognition of CD1-lipid complexes emerged recently [46]. As compared to unliganded CD1c, CD1c binding to C12-C18 fatty acids revealed a major structural reorganization: new contacts within the CD1c protein form a roof over the F′ pocket, and a new G′ portal opens up off the right side of the F′ pocket (Figure 3). This remodeled CD1c surface prompted speculation that the lipid might serve primarily to remodel TCR binding epitopes on CD1c instead of (or in addition to) directly contacting the TCR. Although TCR-lipid-CD1c ternary crystal structures are needed to test the CD1c remodeling model, the recent development of human CD1c tetramers offers the first glimpse into the role of lipids in mediating contact of CD1c with αβ [59] and γδ TCRs [60]. These studies show that exchanging lipid ligands in CD1c can mediate T cell-tetramer binding in a way that is not always highly specific for lipid structure, consistent with the CD1c remodeling hypothesis.

Conclusions

The emerging absence of interference and CD1 remodeling models provide case studies for a general theme in CD1 research: the CD1 system and MHC systems work differently. The cellular pathways (Figure 1), hollow antigen binding clefts (Figure 2) and TCR interaction mechanisms (Figure 3) do show parallels. These apparent similarities inspired experimentalists to use established concepts from MHC system to rapidly generate and test hypotheses on CD1-expressing APCs. However, the biochemical differences between lipids and peptides, the restricted nature of CD1 expression in tissues, the distinct modes of gene regulation and the simplified population genetics of CD1 all make the case for fundamentally different mechanisms of lipid and peptide antigen capture by APCs.

Highlights.

Human CD1a, CD1b, CD1c, and CD1d antigen presenting molecules all display lipids to T cells, but each uses distinct trafficking pathways and antigen capture mechanisms.

Stimulus dependent gene regulation is a prominent aspect of CD1a, CD1b and CD1c expression in cells, yet the upstream genetic regulators are unknown.

Unlike the shallow grooves in MHC molecules, CD1 antigen binding clefts are deep and their architecture is increasingly defined by the location of named portals through which antigens protrude.

Among human CD1 antigen presenting molecules, CD1b is the structural outlier based on its large interior volume and the lack of any known self lipid that fully fills the cleft.

CD1 molecules use three general mechanisms for T cell receptor contact, which are known as ‘headgroup discrimination,’ ‘absence of Interference’, and ‘CD1 remodeling.’

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Steve Porcelli and Jamie Rossjohn for advice. This work was supported by the NIH (U19 AI11124, R01 AI049313, R01 AR048632) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Annotated Bibliography

Highly recommend (two stars)

Mansour et al, in PNAS, 2015. Whereas most CD1 ligands have linear and flexible alkyl chains, CD1c can bind to a rigid and ringed lipid structure comprised of cholesterol. The lipid binding event dramatically altered the presumed TCR binding surface of CD1c.

Birkinshaw et al, Nature Immunology, 2015. The first structure of CD1a-lipid-TCR shows that the TCR binds to CD1a itself rather than the bound lipid. Such true CD1a autoreactivity might explain why CD1a autoreactive T cells are common in human blood and why self antigens lack hydropholic head groups for recognition.

Recommended (one star)

Gras et al., Nature Communications, 2016. The first ternary structure involving CD1b explains how germline encoded mycolyl reactive (GEM) T cells recognize glycolipid antigens. The carbohydrate headgroup rises out of the CD1 cleft and is extensively contacted using a tweezers-like mechanism of the TCR α and β chains.

Sugita in Science in 1996. This work identified the tyrosine-based recycling signal in CD1b, providing the foundation for the endosomal recycling pathways involving human CD1b, CD1c and CD1d as well as mouse CD1d. CD1b proteins traffic to multilammelar structures, leading to the speculation that lipids could load directly from contralateral membranes that appose CD1 proteins.

Publications Cited

- 1.Ackerman AL, Cresswell P. Cellular mechanisms governing cross-presentation of exogenous antigens. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:678–684. doi: 10.1038/ni1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMichael AJ, Pilch JR, Galfre G, Mason DY, Fabre JW, Milstein C. A human thymocyte antigen defined by a hybrid myeloma monoclonal antibody. Eur J Immunol. 1979;9:205–210. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830090307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park JJ, Kang SJ, De Silva AD, Stanic AK, Casorati G, Hachey DL, Cresswell P, Joyce S. Lipid-protein interactions: biosynthetic assembly of CD1 with lipids in the endoplasmic reticulum is evolutionarily conserved. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:1022–1026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307847100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briken V, Jackman RM, Dasgupta S, Hoening S, Porcelli SA. Intracellular trafficking pathway of newly synthesized CD1b molecules. EMBO Journal. 2002;21:825–834. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manolova V, Kistowska M, Paoletti S, Baltariu GM, Bausinger H, Hanau D, Mori L, De Libero G. Functional CD1a is stabilized by exogenous lipids. Eur J Immunol. 2006 doi: 10.1002/eji.200535544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briken V, Jackman RM, Watts GF, Rogers RA, Porcelli SA. Human CD1b and CD1c isoforms survey different intracellular compartments for the presentation of microbial lipid antigens. J Exp Med. 2000;192:281–288. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugita M, van Der W, Rogers RA, Peters PJ, Brenner MB. CD1c molecules broadly survey the endocytic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:8445–8450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150236797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackman RM, Stenger S, Lee A, Moody DB, Rogers RA, Niazi KR, Sugita M, Modlin RL, Peters PJ, Porcelli SA. The tyrosine-containing cytoplasmic tail of CD1b is essential for its efficient presentation of bacterial lipid antigens. Immunity. 1998;8:341–351. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80539-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moody DB, Briken V, Cheng TY, Roura-Mir C, Guy MR, Geho DH, Tykocinski ML, Besra GS, Porcelli SA. Lipid length controls antigen entry into endosomal and nonendosomal pathways for CD1b presentation. Nature Immunol. 2002;3:435–442. doi: 10.1038/ni780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spada FM, Koezuka Y, Porcelli SA. CD1d-restricted recognition of synthetic glycolipid antigens by human natural killer T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1529–1534. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugita M, Cao X, Watts GF, Rogers RA, Bonifacino JS, Brenner MB. Failure of trafficking and antigen presentation by CD1 in AP-3- deficient cells. Immunity. 2002;16:697–706. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00311-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugita M, Grant EP, van Donselaar E, Hsu VW, Rogers RA, Peters PJ, Brenner MB. Separate pathways for antigen presentation by CD1 molecules. Immunity. 1999;11:743–752. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunger RE, Sieling PA, Ochoa MT, Sugaya M, Burdick AE, Rea TH, Brennan PJ, Belisle JT, Blauvelt A, Porcelli SA, et al. Langerhans cells utilize CD1a and langerin to efficiently present nonpeptide antigens to T cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:701–708. doi: 10.1172/JCI19655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barral DC, Cavallari M, McCormick PJ, Garg S, Magee AI, Bonifacino JS, De Libero G, Brenner MB. CD1a and MHC class I follow a similar endocytic recycling pathway. Traffic. 2008;9:1446–1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawton AP, Prigozy TI, Brossay L, Pei B, Khurana A, Martin D, Zhu T, Spate K, Ozga M, Honing S, et al. The mouse CD1d cytoplasmic tail mediates CD1d trafficking and antigen presentation by adaptor protein 3-dependent and - independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2005;174:3179–3186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Relloso M, Cheng TY, Im JS, Parisini E, Roura-Mir C, DeBono C, Zajonc DM, Murga LF, Ondrechen MJ, Wilson IA, et al. pH-dependent interdomain tethers of CD1b regulate its antigen capture. Immunity. 2008;28:774–786. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang SJ, Cresswell P. Saposins facilitate CD1d-restricted presentation of an exogenous lipid antigen to T cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:175–181. doi: 10.1038/ni1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winau F, Schwierzeck V, Hurwitz R, Remmel N, Sieling PA, Modlin RL, Porcelli SA, Brinkmann V, Sugita M, Sandhoff K, et al. Saposin C is required for lipid presentation by human CD1b. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:169–174. doi: 10.1038/ni1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou D, Cantu C, III, Sagiv Y, Schrantz N, Kulkarni AB, Qi X, Mahuran DJ, Morales CR, Grabowski GA, Benlagha K, et al. Editing of CD1d-bound lipid antigens by endosomal lipid transfer proteins. Science. 2004;303:523–527. doi: 10.1126/science.1092009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calabi F, Jarvis JM, Martin L, Milstein C. Two classes of CD1 genes. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:285–292. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng Z, Castaño AR, Segelke BW, Stura EA, Peterson PA, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of mouse CD1: an MHC-like fold with a large hydrophobic binding groove. Science. 1997;277:339–345. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gadola SD, Zaccai NR, Harlos K, Shepherd D, Castro-Palomino JC, Ritter G, Schmidt RR, Jones EY, Cerundolo V. Structure of human CD1b with bound ligands at 2.3 A, a maze for alkyl chains. Nature Immunol. 2002;3:721–726. doi: 10.1038/ni821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zajonc DM, Elsliger MA, Teyton L, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of CD1a in complex with a sulfatide self antigen at a resolution of 2.15 A. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:808–815. doi: 10.1038/ni948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scharf L, Li NS, Hawk AJ, Garzon D, Zhang T, Fox LM, Kazen AR, Shah S, Haddadian EJ, Gumperz JE, et al. The 2.5 a structure of CD1c in complex with a mycobacterial lipid reveals an open groove ideally suited for diverse antigen presentation. Immunity. 2010;33:853–862. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dougan SK, Kaser A, Blumberg RS. CD1 expression on antigen-presenting cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;314:113–141. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69511-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porcelli S, Brenner MB, Greenstein JL, Balk SP, Terhorst C, Bleicher PA. Recognition of cluster of differentiation 1 antigens by human CD4-CD8-cytolytic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1989;341:447–450. doi: 10.1038/341447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yakimchuk K, Roura-Mir C, Magalhaes KG, de Jong A, Kasmar AG, Granter SR, Budd R, Steere A, Pena-Cruz V, Kirschning C, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi infection regulates CD1 expression in human cells and tissues via IL1-beta. European journal of immunology. 2011;41:694–705. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roura-Mir C, Wang L, Cheng TY, Matsunaga I, Dascher CC, Peng SL, Fenton MJ, Kirschning C, Moody DB. Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulates CD1 antigen presentation pathways through TLR-2. J Immunol. 2005;175:1758–1766. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hava DL, van der Wel N, Cohen N, Dascher CC, Houben D, Leon L, Agarwal S, Sugita M, van Zon M, Kent SC, et al. Evasion of peptide, but not lipid antigen presentation, through pathogen-induced dendritic cell maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11281–11286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804681105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chow A, Toomre D, Garrett W, Mellman I. Dendritic cell maturation triggers retrograde MHC class II transport from lysosomes to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2002;418:988–994. doi: 10.1038/nature01006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sieling PA, Jullien D, Dahlem M, Tedder TF, Rea TH, Modlin RL, Porcelli Sa. CD1 expression by dendritic cells in human leprosy lesions: correlation with effective host immunity. Journal of Immunology. 1999;162:1851–1858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seshadri C, Shenoy M, Wells RD, Hensley-McBain T, Andersen-Nissen E, McElrath MJ, Cheng TY, Moody DB, Hawn TR. Human CD1a deficiency is common and genetically regulated. J Immunol. 2013;191:1586–1593. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de la Salle H, Mariotti S, Angenieux C, Gilleron M, Garcia-Alles LF, Malm D, Berg T, Paoletti S, Maitre B, Mourey L, et al. Assistance of microbial glycolipid antigen processing by CD1e. Science. 2005;310:1321–1324. doi: 10.1126/science.1115301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leon L, Tatituri RV, Grenha R, Sun Y, Barral DC, Minnaard AJ, Bhowruth V, Veerapen N, Besra GS, Kasmar A, et al. Saposins utilize two strategies for lipid transfer and CD1 antigen presentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4357–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200764109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan W, Qi X, Tsang P, Kang SJ, Illarionov PA, Besra GS, Gumperz J, Cresswell P. Saposin B is the dominant saposin that facilitates lipid binding to human CD1d molecules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:5551–5556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700617104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van den Elzen P, Garg S, Leon L, Brigl M, Leadbetter EA, Gumperz JE, Dascher CC, Cheng TY, Sacks FM, Illarionov PA, et al. Apolipoprotein-mediated pathways of lipid antigen presentation. Nature. 2005;437:906–910. doi: 10.1038/nature04001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeissig S, Dougan SK, Barral DC, Junker Y, Chen Z, Kaser A, Ho M, Mandel H, McIntyre A, Kennedy SM, et al. Primary deficiency of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in human abetalipoproteinemia is associated with loss of CD1 function. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:2889–2899. doi: 10.1172/JCI42703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dougan SK, Salas A, Rava P, Agyemang A, Kaser A, Morrison J, Khurana A, Kronenberg M, Johnson C, Exley M, et al. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein lipidation and control of CD1d on antigen-presenting cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:529–539. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Jong A, Cheng TY, Huang S, Gras S, Birkinshaw RW, Kasmar AG, Van Rhijn I, Pena-Cruz V, Ruan DT, Altman JD, et al. CD1a-autoreactive T cells recognize natural skin oils that function as headless antigens. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:177–185. doi: 10.1038/ni.2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynch L, Nowak M, Varghese B, Clark J, Hogan AE, Toxavidis V, Balk SP, O’Shea D, O’Farrelly C, Exley MA. Adipose tissue invariant NKT cells protect against diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorder through regulatory cytokine production. Immunity. 2012;37:574–587. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugita M, Jackman RM, van Donselaar E, Behar SM, Rogers RA, Peters PJ, Brenner MB, Porcelli SA. Cytoplasmic tail-dependent localization of CD1b antigen-presenting molecules to MIICs. Science. 1996;273:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ray A, Schmitt D. Langerhans cell: CD1 antigens and the Birbeck granule. Pathol Biol(Paris) 1988;36:846–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koch M, Stronge VS, Shepherd D, Gadola SD, Mathew B, Ritter G, Fersht AR, Besra GS, Schmidt RR, Jones EY, et al. The crystal structure of human CD1d with and without alpha-galactosylceramide. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:819–826. doi: 10.1038/ni1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saper MA, Bjorkman PJ, Wiley DC. Refined structure of the human histocompatibility antigen HLA-A2 at 2.6 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1991;219:277–319. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90567-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Li Y, Kinjo Y, Mac TT, Gibson D, Painter GF, Kronenberg M, Zajonc DM. Lipid binding orientation within CD1d affects recognition of Borrelia burgorferi antigens by NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1535–1540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909479107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mansour S, Tocheva AS, Cave-Ayland C, Machelett MM, Sander B, Lissin NM, Molloy PE, Baird MS, Stubs G, Schroder NW, et al. Cholesteryl esters stabilize human CD1c conformations for recognition by self-reactive T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E1266–1275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519246113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng TY, Relloso M, Van Rhijn I, Young DC, Besra GS, Briken V, Zajonc DM, Wilson IA, Porcelli S, Moody DB. Role of lipid trimming and CD1 groove size in cellular antigen presentation. Embo J. 2006;25:2989–2999. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shamshiev A, Gober HJ, Donda A, Mazorra Z, Mori L, De Libero G. Presentation of the same glycolipid by different CD1 molecules. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1013–1021. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cox D, Fox L, Tian R, Bardet W, Skaley M, Mojsilovic D, Gumperz J, Hildebrand W. Determination of cellular lipids bound to human CD1d molecules. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang S, Cheng TY, Young DC, Layre E, Madigan CA, Shires J, Cerundolo V, Altman JD, Moody DB. Discovery of deoxyceramides and diacylglycerols as CD1b scaffold lipids among diverse groove-blocking lipids of the human CD1 system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:19335–19340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112969108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Batuwangala T, Shepard D, Gadola SD, Gibson KJC, Zaccai NR. The crystal structure of human CD1b with a bound bacterial glycolipid. J Immunol. 2003:2382–2388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gras S, Van Rhijn I, Shahine A, Cheng TY, Bhati M, Tan LL, Halim H, Tuttle KD, Gapin L, Le Nours J, et al. T cell receptor recognition of CD1b presenting a mycobacterial glycolipid. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13257. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Alles LF, Collmann A, Versluis C, Lindner B, Guiard J, Maveyraud L, Huc E, Im JS, Sansano S, Brando T, et al. Structural reorganization of the antigen-binding groove of human CD1b for presentation of mycobacterial sulfoglycolipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17755–17760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110118108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moody DB, Reinhold BB, Guy MR, Beckman EM, Frederique DE, Furlong ST, Ye S, Reinhold VN, Sieling PA, Modlin RL, et al. Structural requirements for glycolipid antigen recognition by CD1b-restricted T cells. Science. 1997;278:283–286. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, Ueno H, Nakagawa R, Sato H, Kondo E, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of Và14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borg NA, Wun KS, Kjer-Nielsen L, Wilce MC, Pellicci DG, Koh R, Besra GS, Bharadwaj M, Godfrey DI, McCluskey J, et al. CD1d-lipid-antigen recognition by the semi-invariant NKT T-cell receptor. Nature. 2007;448:44–49. doi: 10.1038/nature05907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birkinshaw RW, Pellicci DG, Cheng TY, Keller AN, Sandoval-Romero M, Gras S, de Jong A, Uldrich AP, Moody DB, Godfrey DI, et al. alphabeta T cell antigen receptor recognition of CD1a presenting self lipid ligands. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:258–266. doi: 10.1038/ni.3098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Rhijn I, Godfrey DI, Rossjohn J, Moody DB. Lipid and small-molecule display by CD1 and MR1. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:643–654. doi: 10.1038/nri3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ly D, Kasmar AG, Cheng TY, de Jong A, Huang S, Roy S, Bhatt A, van Summeren RP, Altman JD, Jacobs WR, Jr, et al. CD1c tetramers detect ex vivo T cell responses to processed phosphomycoketide antigens. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:729–741. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roy S, Ly D, Castro CD, Li NS, Hawk AJ, Altman JD, Meredith SC, Piccirilli JA, Moody DB, Adams EJ. Molecular Analysis of Lipid-Reactive Vdelta1 gammadelta T Cells Identified by CD1c Tetramers. J Immunol. 2016;196:1933–1942. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]