To explore barriers to clinical trial participation experienced by the black community in Boston, MA, the Lazarex‐MGH Cancer Care Equity Program at Massachusetts General Hospital partnered with the Center for Community Health Education Research and Service to implement a multiphase community‐engaged assessment. This assessment set out to identify black Bostonians' perceptions of cancer care and cancer clinical trials, drawing on qualitative research methods to inform programmatic and outreach activities. This article reports the implications of the findings in the context of care coordination and follow‐up between oncologists and primary care providers.

Keywords: Community‐engaged assessment, Barriers to cancer care, Cancer clinical trial, Minority clinical trial participation, Interpersonal aspects of cancer care, Cancer disparities

Abstract

Background.

Despite efforts to ameliorate disparities in cancer care and clinical trials, barriers persist. As part of a multiphase community‐engaged assessment, an exploratory community‐engaged research partnership, forged between an academic hospital and a community‐based organization, set out to explore perceptions of cancer care and cancer clinical trials by black Bostonians.

Materials and Methods.

Key informant interviews with health care providers and patient advocates in community health centers (CHCs), organizers from grassroots coalitions focused on cancer, informed the development of a focus group protocol. Six focus groups were conducted with black residents in Boston, including groups of cancer survivors and family members. Transcripts were coded thematically and a code‐based report was generated and analyzed by community and academic stakeholders.

Results.

While some participants identified clinical trials as beneficial, overall perceptions conjured feelings of fear and exploitation. Participants describe barriers to clinical trial participation in the context of cancer care experiences, which included negative interactions with providers and mistrust. Primary care physicians (PCPs) reported being levied as a trusted resource for patients undergoing care, but lamented the absence of a mechanism by which to gain information about cancer care and clinical trials.

Conclusions.

Confusion about cancer care and clinical trials persists, even among individuals who have undergone treatment for cancer. Greater coordination between PCPs and CHC care teams and oncology care teams may improve patient experiences with cancer care, while also serving as a mechanism to disseminate information about treatment options and clinical trials.

Implications for Practice.

Inequities in cancer care and clinical trial participation persist. The findings of this study indicate that greater coordination with primary care physicians (PCPs) and community health center (CHC) providers may be an important step for both improving the quality of cancer care in communities and increasing awareness of clinical trials. However, PCPs and CHCs are often stretched to capacity with caring for their communities. This leaves the oncology community well positioned to create programs to bridge the communication gaps and provide resources necessary to support oncologic care along the cancer continuum, from prevention through survivorship.

Introduction

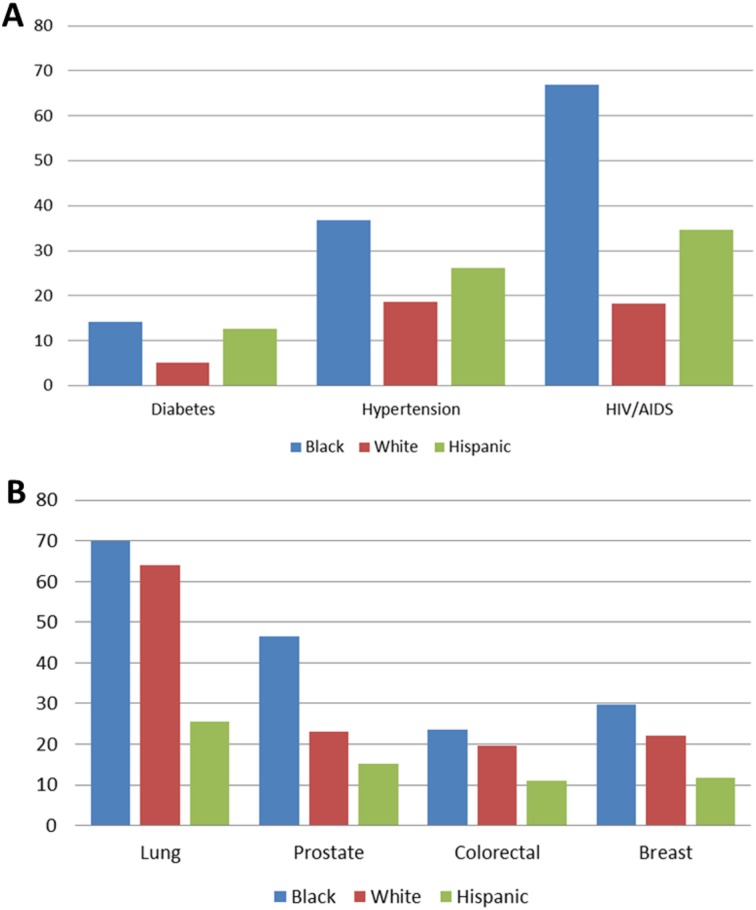

Boston is home to some of the most prestigious health care facilities and academic institutions in the world [1]. In fiscal year 2013, Boston area hospitals alone received $1.1 billion in research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [2]; the city is a national leader in NIH funding, having received nearly $29 billion between 1992 and 2013 [2]. However, not all Bostonians benefit from the health care advances the city is known for. Despite funding and infrastructure, a pronounced racial gap exists when it comes to health outcomes and access to health care in Boston [1], [3], [4], [5], [6]. Black Bostonians experience a disproportionate burden of chronic conditions when compared with whites, including increased incidence of diabetes (14.1% vs. 5.1%), hypertension (36.7% vs. 18.6%), and HIV/AIDS (66.9% vs. 18.2%; Fig. 1) [4]. Black Bostonians also have the worst cancer outcomes, with statistically significant cancer mortality across the top four cancer diagnoses (Fig. 1). Despite higher rates of cancer‐related morbidity and mortality nationally, blacks are far less likely than their white counterparts to enroll in clinical trials. One comprehensive report showed that between 1996–2002, the majority of trial participants were white, with the proportion of blacks and Hispanics limited to 3.0% and 7.9%, respectively [7]. Lack of participation by communities of color in cancer clinical trials may limit their access to cutting‐edge treatments.

Figure 1.

A sample of health disparities in Boston. (A): Incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and HIV/AIDS in Boston by race/ethnicity for 2015. (B): Age‐adjusted cancer mortality rates by race/ethnicity from 2005–2009. Blacks in Boston have the highest burden of chronic disease and worse cancer‐specific mortality than any other race/ethnicity. (Adapted from Health of Boston 2015 [4]).

A number of factors have been proposed to explain the underrepresentation of blacks in clinical trials. Challenges to engaging the black community in research include both historical and contextual factors. Systematic oppression, for example, including exploitation, violence, and cultural imperialism, have contributed to the black community's distrust and suspicion of the academic research enterprise [8], [9]. Furthermore, factors linked to poverty, a condition in which black people are overrepresented [10], such as long work hours, competing responsibilities, and barriers to transportation, impede access to health care as well as research participation [8]. Ford et al. theorized that acceptance or refusal to participate in cancer clinical trials is largely influenced by awareness and opportunity [11]. Awareness is characterized as knowledge, beliefs and attitudes, self‐efficacy, health literacy, and the organizational environments. Meanwhile, opportunity is described as provider knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, eligibility criteria, access, insurance, and disease state, among others [11]. However, there is a degree of complexity associated with both “awareness” and “opportunity” barriers experienced by the black community, which is socioeconomically, culturally, and linguistically diverse [12]. Furthermore, what it means to be “black” may vary by both spatial and social location [13]. What is missing in our knowledge of this complex issue is a nuanced understanding of within‐group barriers to clinical trial participation. Because community‐specific barriers to participation in clinical trials are shaped by histopolitical, socioenvironmental, and economic factors that produce and sustain the present‐day realities [14], addressing participation barriers begs an understanding of local ecologies, including the life circumstances and experiences of distinct communities [15].

To explore barriers to clinical trials participation experienced by the black community in Boston, the Lazarex‐MGH Cancer Care Equity Program at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) partnered with the Center for Community Health Education Research and Service (CCHERS), a community‐based organization, to implement a multiphase community‐engaged assessment [16]. Community‐engaged assessments help practitioners and researchers make sense of community norms and aid in the collection of nuanced data needed for the development of programming that is relevant to the unique priorities and context of a given community [17]. This assessment specifically set out to identify black Bostonians’ perceptions of cancer care and cancer clinical trials, drawing on qualitative research methods in order to inform programmatic and outreach activities. In this paper, we discuss the implications of our findings in the context of care coordination and follow‐up between oncologists and primary care providers (PCPs).

Materials and Methods

Mixed qualitative methods were employed to explore how black Bostonians conceptualize barriers to cancer clinical trials and cancer care. The assessment protocol was approved by the Northeastern University Institutional Review Board (IRB), which serves as the IRB of record for CCHERS.

Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted with a diverse group of community and health care leaders to inform the development of a focus group protocol. Purposive sampling, a nonprobable sampling strategy designed to identify elements of a population with specific knowledge, was employed [18], [19]. Recruitment was initiated via CCHERS collaborators; 15 potential participants were contacted by e‐mail and/or telephone. A description of the interviews and a copy of the consent form were sent to participants prior to the scheduled session; consent was administered at the time of the interview.

A semi‐structured interview guide was developed to elicit participant perspectives on (a) barriers to cancer clinical trials experienced by black residents, (b) barriers to cancer care, and (c) potential strategies or approaches for overcoming identified barriers. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Themes were identified and used to develop a codebook by two independent coders. The coding team met to review and reconcile the codes. Once consensus was reached, the data were re‐coded and text reports were generated by code. Data themes were presented to the MGH investigator, who provided additional context.

Focus Group Methodology

A focus group protocol was developed to explore perceptions of and barriers to participation in cancer clinical trials. Themes generated from key informant interviews were used to inform the direction of the focus groups. Themes included (a) awareness barriers, such as community knowledge of cancer clinical trials and ways to access the information; (b) opportunity barriers, including cost associated with clinical trials and the extent to which providers share information about trials; and (c) acceptance/refusal barriers like fear, family and work obligations, mistrust, and provider‐level factors. Strategies for overcoming described barriers were also explored.

A two‐step community‐engaged convenience sampling strategy was employed. Community leaders were purposefully selected to organize focus groups. Those who agreed to participate used availability and snowball sampling [20] to identify constituents appropriate for each of the six groups. Communities were selected based on percentage of black residents (range 55%–76%) [21]. Focus groups were held at partner organizations and in community spaces.

At the onset of the group, informed consent was obtained and participants were asked to complete a brief demographic screener. All groups were audio recorded and transcribed. Two independent coders conducted systematic content analyses of a sample of the groups (n = 2) and then met to reconcile codes line by line. Themes identified were used to develop a preliminary codebook, which was applied to the remaining group transcripts by a single coder and reviewed by the coding team. Additional nodes were added to the codebook during the coding process. The final codebook and coded transcripts were entered into NVivo QSR version 10.4 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia, http://www.qsrinternational.com) [22].

Results

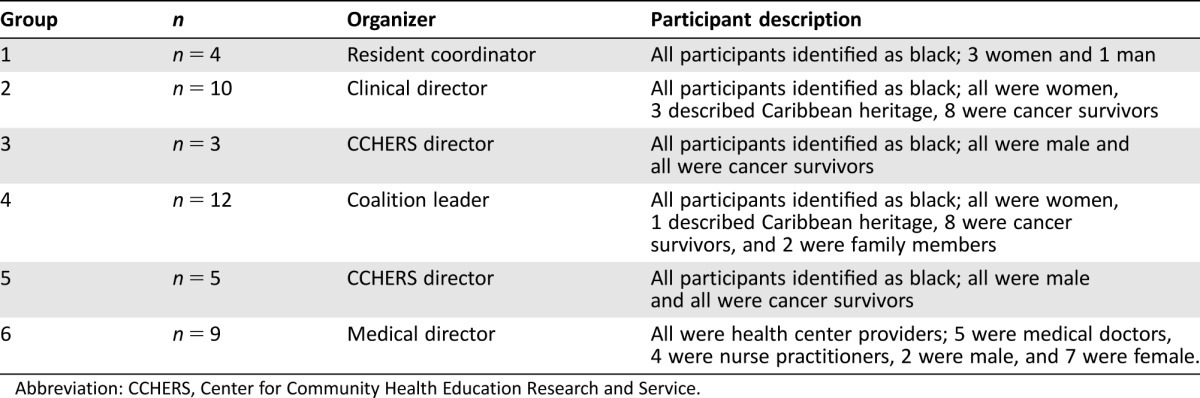

A total of eight key informant interviews and six focus groups were conducted. Key informants included the medical director of a community health center (CHC), an oncologist, two cancer care health educators, a religious leader with health ministries, two coalition leaders with a focus on health, and a cancer survivor. The six focus groups were conducted in three different neighborhoods with predominantly black residents. All groups were composed of self‐identified blacks, except for the focus group of providers (Table 1).

Table 1. Focus group participants.

Abbreviation: CCHERS, Center for Community Health Education Research and Service.

Key Informant Perceptions of Barriers

There was overlap in the themes discussed across key informants (Table 2). Overall, participants reported negative perceptions of clinical trials among their constituents, but noted variation based on generational status, knowledge, and personal experiences. For example, when asked about community perceptions of clinical trials, one religious leader who was just over 60 years of age reported the following:

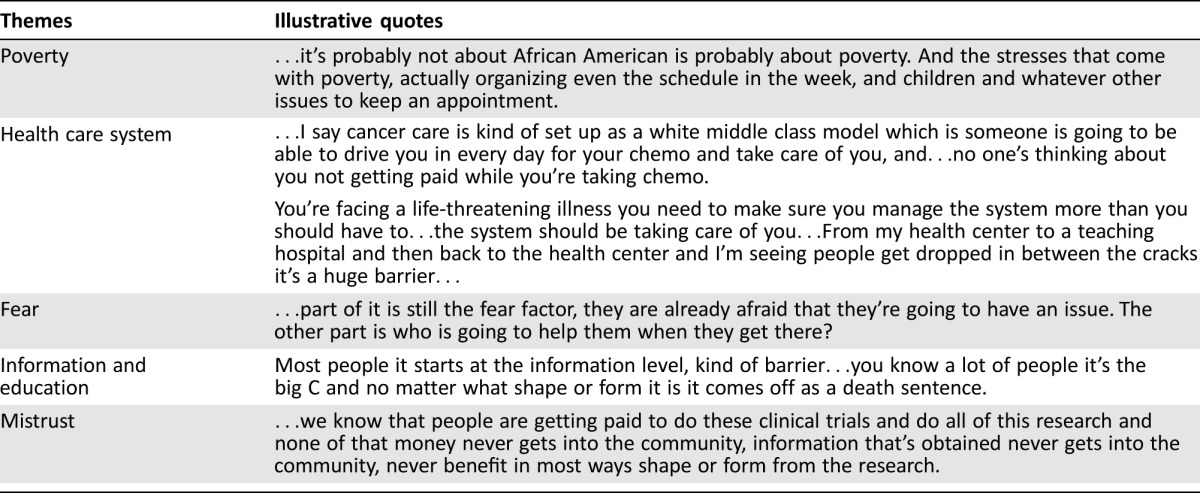

Table 2. General themes from key informant interviews.

“To be honest they are seen very negatively, especially with the people who are my age and older…[E]ven now you hear some people talk about the Tuskegee…it's like it happened yesterday for a lot of people.”

Knowledge of trials and provider trust repeatedly emerged as a moderating factor, as is illustrated by the following quote from an oncologist:

“[W]hen you talk to people and you explain what clinical trials are like, people are more likely to think about them. And I think people will go on clinical trials if they trust their clinician.”

Barriers to clinical trials perceived by key informants were described at the individual level (socioeconomic status [SES], access to information and health care experiences), health systems level (health care inequity and care coordination), and broader community level (transportation). Many of these factors are interrelated.

Socioeconomic Status.

Low SES was discussed as an indirect and direct barrier to clinical trial participation. Participants felt that living in poverty impedes participation in clinical trials and adherence to cancer care in general. Additionally, occupation can directly impact one's ability to make time to participate in cancer care and clinical trials. A coalition leader discussed the role of low SES:

“[M]aybe you have to take care of bills and other things; you have to do your job. This health thing is not the highest on your list because you really don't have time for it and that's probably one of the biggest barriers because people really expect you to drop everything in your life and take care of this cancer problem. Everything in your life has to stop, and you don't necessarily have a whole lot of people who can drive you in for chemotherapy every day and do all these things that we expect people to do. So I think one of the biggest barriers is really SES and money…the issue of time and money.”

Lack of Information.

Access to information also emerged as a barrier to clinical trial participation. A health educator shared that people are not informed about clinical trials and how to get involved, stating, “…we found out when we're out in the street doing these [educational sessions] that there is very little knowledge about the way clinical trials work today.” A coalition leader shared this sentiment:

“I think about people not understanding what's involved and I also think that, not just understanding what's involved but people who…need some prep before they get involved in these clinical trials; they need an understanding of what they're getting involved in…Someone comes up and talks about a clinical trial in the midst of everything that's going on, maybe they decide that they're going to do it, but it's not because they're very well informed. Might be because they put their trust in a physician.”

Systemic Barriers in Health Care.

Health care was seen as both a direct and indirect barrier to clinical trial participation. As described by an oncologist, the direct barrier was related to where individuals sought cancer care: “Most clinical trials are done in larger tertiary care centers and if you don't get referred in then you're not going to get access to those trials.” Similarly, a medical director discussed the importance of information about cancer care and clinical trials and care coordination. If cancer centers do not share information about clinical trials with the broader community and CHCs, local providers are less likely to know about clinical trials and support patient enrollment. A PCP commented, “we get letters from different trials”; however, there was no clear mechanism in place to track or share information about clinical trials. It seemed more dependent on individual oncologists: “[Dr.] has made huge strides for us in terms of finding out about clinical trials so that has been a big plus for us. Before that, I wasn't aware.”

Barriers at the Community Level.

Key informants focused mainly on physical barriers to care that influenced adherence to treatment plans. However, broader community‐level barriers described included transportation and trust. Transportation in this urban setting was centered around a lack of access to public transportation. Although most cancer centers are accessible by train, neighborhoods in the city where the majority of black residents live are not train accessible. This requires individuals without access to a vehicle to take one (or more) buses to reach train lines.

Themes from Focus Groups

Key themes that emerged from the focus groups were related to participant understanding of clinical trials, trust, and the interpersonal aspects of care. Most themes derived from the focus groups were consistent, with the exception of responses from group 1. This was the only group with no cancer survivors or clinical providers. Group 1 had a difficult time describing clinical trials, whereas participants in the other focus group were aware of and able to explain the general concept of clinical trials.

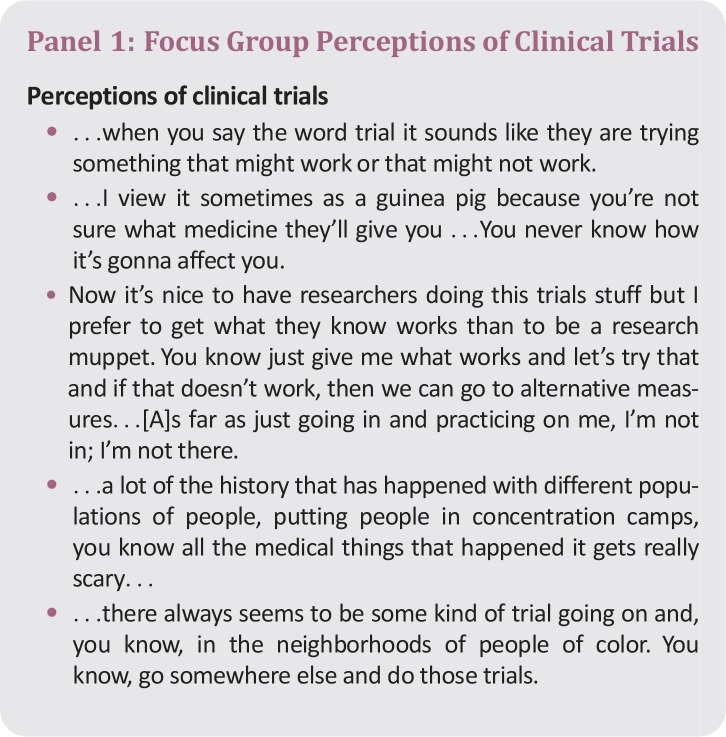

Perceptions and Understanding of Clinical Trials.

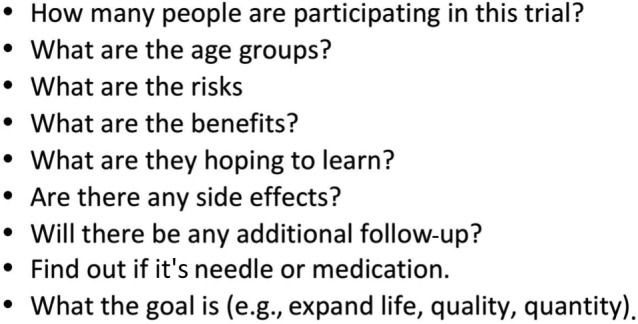

When participants from groups 2–6 were asked what they would tell a friend considering participating in a cancer clinical trial, they generated a detailed list of questions and comments. Participants identified important questions to ask providers when considering a clinical trial, including review of the risks and benefits, logistics, and overall study goals (Fig. 2). However, responses related to perceptions of clinical trials suggest a limited understanding of what clinical trials are (Panel 1). When asked what came to mind when they heard the phrase “clinical trial,” the majority of responses in the nonprovider groups described “experiments” that objectify people. There was uncertainty about whether enrollees would receive treatment or a placebo. Five groups voiced the word “guinea pig.” For others, clinical trials reportedly conjured images of “exploitation,” “risk,” “side effects,” and “invasive procedures,” as well as historical exploitation associated with the medical community. Despite being leery of clinical trials, some participants in the survivor groups saw benefit in research, acknowledging that new discoveries and treatment advances might result. They stated that results may give the “professional field a better insight on whatever the trial is getting towards.”

Figure 2.

Questions to ask when approached about a clinical trial. Focus group participants were asked what questions they would encourage a friend to ask if they were considering participation in a clinical trial.

The provider group also highlighted the benefits, describing clinical trials as “a way to learn new information” and “best treatment practices.” However, when asked to share their perspectives on how patients view clinical trials, responses shifted. It was reported that “[patients] get very skeptical.” When asked to explain, a second provider reported, “some people they don't want to because they feel like they're going to be a guinea pig.”

Impact of Fear.

This complex picture related to perceptions of cancer clinical trials is further distorted by general perceptions of cancer and cancer care. All groups described the fear of a cancer diagnosis. The diagnosis of cancer and associated fears may preclude thinking about clinical trials or treatment:

“It's the fear, like hey if I get it I get it, I'm gonna die anyway so let me die.

…the fears that come into place, going in by yourself, because some of us don't have the family support.”

Familial responsibilities impact perceptions of and access to cancer care; therefore, they influence participation in clinical trials. This was a particularly salient theme in cases where the main caregiver in the family is diagnosed with cancer. “I think people are worried about their families too, especially if they got kids.”

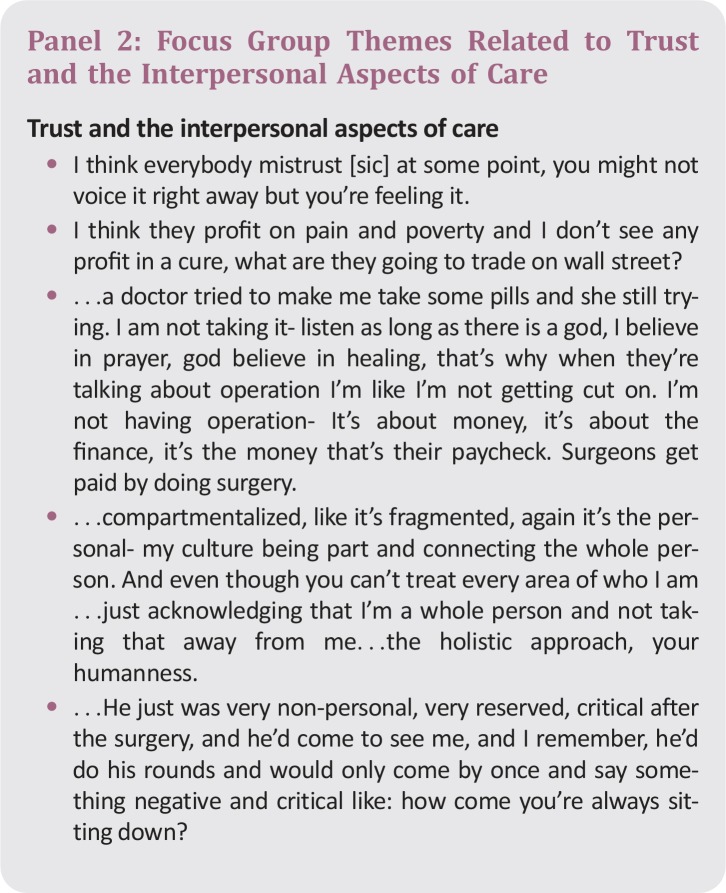

Trust and the Interpersonal Aspects of Care.

An important theme that developed from the focus groups with survivors and family members was mistrust and the interpersonal aspects of their cancer care (Panel 2). Several participants shared multiple stories about negative experiences they had with cancer care providers and at cancer centers. These negative experiences with the interpersonal aspects of cancer care were ameliorated by patient discussion with their PCPs. The trusted relationship with a known provider enabled them to make sense of information they received during the course of cancer care.

PCPs similarly remarked about the support and advice patients sought following a visit to their oncologist:

“[A patient] had a mammogram, and she's always kept up with mammograms and she ended up with cancer. So she went back to the hospital, saw the doctor. They gave her all her options. She could have mastectomy but they were sort of leaning towards lumpectomy so she came, made an appointment to see me…to see what did I think.”

A second provider chimed in to comment:

“I have the same situation…with colon cancer…when they come back [from the hospital], the family comes back, to talk to me—what is safe, what is my opinion, if I would redo the plan.”

The nine providers agreed that many of the patients diagnosed with cancer who see oncologists at various hospitals throughout the city come back to seek their advice. One of the doctors explained:

“…we have the great advantage of having a long‐term rapport with our patients, so by in large our patients will essentially do what we recommend. So they go to the hospitals completely different from our facility here, it's not quite warm and fuzzy…what I try to do is try to explain to the patients what to expect…kind of warm them up to what would happen.”

Although PCPs reported hearing from patients, when asked if they ever heard from oncologists, they admitted that care coordination between oncologists and community providers was limited.

Discussion

This qualitative assessment set out to explore the perceptions of and barriers to cancer care and clinical trial participation among a diverse community sample of black Bostonians. Overall, our findings were consistent with the literature in which stigma, patient‐provider interactions characterized by mistrust, limited health literacy, and competing interests have been documented as barriers to clinical trial participation and cancer care in general [23]. In this cohort, specifically, many individuals consider cancer care in general to be overwhelming. The stigma associated with a cancer diagnosis, combined with the impact of fear, financial concerns, and familial dynamics greatly impact decisions regarding care and the patient's ability to actively engage in their cancer care. These concerns may be compounded if cancer care is provided outside of a patient's health care home. Patients described a cycle of fear and mistrust associated with the interpersonal aspect of care during oncology appointments.

Although many focus group participants could articulate what questions to ask when approached about participation in a clinical trial, there was still a significant mistrust and misunderstanding about clinical trials. Although some focus group participants were able to describe the benefits of clinical trials and outline important questions to ask providers about the nature of clinical trials, some did not have a clear conceptualization of the goals and intent of clinical trials. Moreover, others took the word “trial” literally and were concerned about being test subjects for a remedy they felt would be less than the standard of care. Overall, there was great skepticism around the notion of clinical trials, which was further complicated by fear of a cancer diagnosis and financial concerns.

We found that negative experiences with cancer care erode patient trust and receptiveness to cancer care. The interpersonal aspects of care greatly influence patient engagement in their care; this may in turn influence likelihood of referral for clinical trials and patient willingness to participate. Our findings suggest that relationships with PCPs may help ameliorate some of the fear and distrust experienced by patients diagnosed with cancer. Health center PCPs described circumstances where patients returned to them seeking support and advice regarding their hospital‐based cancer treatment and consultations. These finding are timely given the recent report by the Lancet Oncology Commission, which calls for an expanded role of primary care in cancer control, given a focus on prevention and screening and an increasing number of cancer diagnoses [24]. If cancer care is to move towards a more holistic model that is patient centered, the PCP will need to play an integral role [24]. Based on our findings, we believe this shift in practice has important implications for cancer care in communities of color and for cancer clinical trials participation.

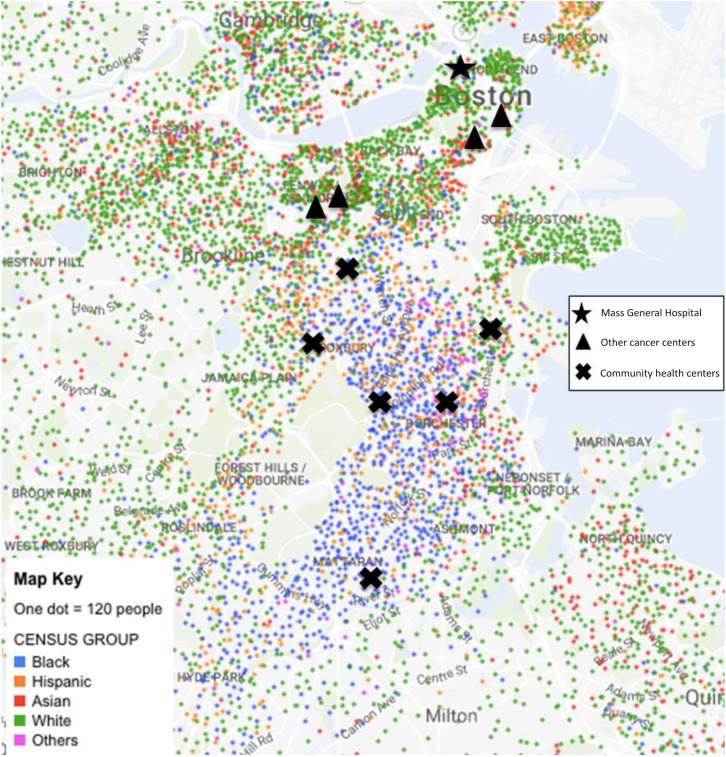

Community health centers play an integral role in providing care to underserved communities. In Boston, CHCs are nested in communities of color, making it easier for providers to become trusted partners in the health and well‐being of these traditionally underserved populations; this is in stark contrast to the location of Boston cancer centers (Fig. 3). Previous studies have shown that CHCs improve access to health care, provide continuous and high‐quality primary care, and reduce the use of more expensive care providers, such as emergency departments and hospitals [25]. Furthermore, evidence suggests they are effective in reducing disparities in health care access based on race, ethnicity, income, and insurance status [26]. In our study, participants described a level of trust with their PCPs that did not exist with their oncologists. Similarly, PCPs indicated that patients returned to them for discussions regarding cancer treatment options, but reported little care coordination from oncologists to help support an informed discussion between the PCP and their patient. If appropriately valued and supported, PCPs and health care providers at CHCs will become an invaluable member of the cancer care team by supporting patient decisions around cancer care and survivorship.

Figure 3.

Mapping black Boston. Map of Boston showing where the different racial/ethnic groups live in relation to the cancer centers and community health centers. Health centers shown have patient populations that are 55%–76% black. (Adapted from NYTimes Mapping Segregation Project [27])

Primary care physicians also described barriers to accessing information about cancer clinical trials. Greater coordination among primary care teams and cancer centers may increase awareness of clinical trials among PCPs and facilitate dissemination about and support for clinical trial enrollment. Greater care coordination and communication with PCPs may increase patient trust in oncologists, thereby improving the interpersonal aspects of cancer and reducing access barriers to cancer clinical trials.

This research is not without limitation. The results presented are the findings from a community‐engaged qualitative assessment. We employed a two‐stage convenience sampling methodology to explore perceptions of barriers to cancer clinical trials and treatment experienced by diverse black Bostonians. Although this method is appropriate for exploratory assessment and allowed us to engage a diverse group of black residents, cancer survivors, and providers, findings may not be generalizable to all communities. In addition, perceptions of the general population of black Bostonians was limited given the small number of participants who were not cancer survivors or caregivers (focus group 1). Despite small numbers of non‐survivor community members, our results are consistent with the literature suggesting that black populations in general lack awareness and knowledge of clinic trials [11]. Future explorations should include a greater focus on engagement of PCPs in cancer care, inclusion of participants who have not experienced a cancer diagnosis, and variations by nativity given the diversity of the black community.

Conclusion

Community health centers are an important and often‐overlooked health care asset for addressing the health needs of underserved populations. They are embedded in the community and are often a trusted community resource. Primary care physicians, particularly those based at CHCs, often have strong trust relationships with their patients, and can be critical partners in alleviating awareness and opportunity barriers related to cancer care and clinical trial participation.

Because PCPs and CHC systems are frequently already stretched to capacity with caring for their communities, the onus is on the oncology community to create programs to bridge the communication gaps and provide resources necessary to support oncologic care along the cancer continuum, from prevention through survivorship. The following simple steps may help address barriers:

At time of initial patient consultation, confirm name and address of PCP and scope of relationship

Inform patient that their PCP will be involved

Send report of initial consultation to PCP

If a cancer clinical trial is being considered, consider calling the PCP to review goals of study

Keep PCP informed of changes in care plan by sending a copy of appropriate clinical notes

At conclusion of treatment, update PCP, including a brief outline for follow‐up

Additionally, cancer centers may partner with CHCs and PCPs to create an educational forum for patients and providers to review current standards for cancer screening and treatment, discuss new advances in cancer care, share information about ongoing cancer clinical trials, and review goals of survivorship plans. Educational programming can be as simple as a monthly or quarterly educational program sponsored by the oncology care team or development of a more focused continuing medical education course. The most important consideration is not to create more work for the CHCs. It is critical to design community‐based programs in a collaborative way to ensure the needs of CHC providers and PCPs are being met. While poverty, work, and financial barriers persist, these simple steps may help reduce the perceived and real “awareness” and “opportunity” barriers related to cancer care and clinical trials experienced by underserved populations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Brittany McLaren (data analysis and literature review), Chidinma Osuagwa and Kojiro So (data collection and transcription), Elizabeth Powel and Emily Poles for their coordination of the project, and Dr. Gisele Perez‐Lougee for her thoughtful review and comments. Many thanks to the community partners who assisted in this assessment: Roxbury Multi‐Service Center, Mattapan Community Health Center, Madison Park Community Development Corporation, and the Franklin Field/Franklin Hill Dorchester Healthy Boston Coalition. This work was supported by the Lazarex Cancer Foundation.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Linda Sprague Martinez, Elmer R. Freeman, Karen Winkfield

Collection and/or assembly of data: Linda Sprague Martinez

Data analysis and interpretation: Linda Sprague Martinez, Elmer R. Freeman,

Manuscript writing: Linda Sprague Martinez, Elmer R. Freeman, Karen Winkfield

Final approval of manuscript: Linda Sprague Martinez, Elmer R. Freeman, Karen Winkfield

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.City of Boston . About Boston. Available at http://www.cityofboston.gov/visitors/about/. Accessed June 21, 2017.

- 2.Boston Redevelopment Authority. Boston top recipient of NIH funding for 19 consecutive years. 2014, Boston Redevelopment Authority/Research Division: Boston. Available at http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/3fa79965-4df8-4a7f-8b99-e68d2710d09d/.

- 3. Ashman H. Housing justice and racial inequality in Jamaica Plain: A reflection on the 5th Annual State of Our Neighborhood. Available at http://jamaicaplainforum.org/2015/03/13/soon-2015-in-review/. Accessed June 21, 2017.

- 4.Boston Public Health Commission. Health of Boston 2014–2015. 2015. Boston Public Health Commission: Research and Evaluation Office: Boston. Available at http://www.bphc.org/healthdata/health-of-boston-report/Documents/HOB-2014-2015/FullReport_HOB_2014-2015.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2017.

- 5.Massachusetts General Hospital. Widening inequality in Boston and beyond. Available at http://www.massgeneral.org/about/newsarticle.aspx?id=3506. Accessed June 21, 2017.

- 6. Sprague Martinez LS, Gute DM, Ndulue UJ et al. All public health Is local revisiting the importance of local sanitation through the eyes of youth. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1058–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen MS Jr, Lara PN, Dang JH et al. Twenty years post‐NIH Revitalization Act: Enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): Laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual. Cancer 2014;120(suppl 7)1091–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alvarez RA, Vasquez E, Mayorga CC et al. Increasing minority research participation through community organization outreach. West J Nurs Res 2006;28:541–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Young IM. Five faces of oppression. In: Henderson G, Waterstone M, ed. Geographic Thought: A Praxis Perspective. New York: Routledge, 2009:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tobier E. The Changing Face of Poverty. Trends in New York City's Population in Poverty: 1960–1990. New York: The Society, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ford JG, Howerton MW, Bolen S et al. Knowledge and access to information on recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: Summary. In: AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 1998. –2005: 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jennings J, Lewis B, O' Bryant R et al. Blacks in Massachusetts: Comparative demographic, social and economic experiences with whites, Latinos, and Asians. Boston: William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jones CP. Invited commentary: “Race,” racism, and the practice of epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Corbie‐Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2458–2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kagawa‐Singer M, Dadia AV, Yu MC et al. Cancer, culture, and health disparities: Time to chart a new course? CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:12–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winkfield K, Powell E, Osuagwa C et al. Abstract A26: Developing a community‐based partnership to facilitate a multilevel community engaged study exploring barriers to cancer care and clinical trial participation among black Bostonians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24(suppl 10):26a–26a. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community‐based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract 2006;7:312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chambliss DF, Schutt RK. Making sense of the social world: Methods of investigation. London: Sage Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tongco MDC. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobotany Research & Applications 2007;5:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heckathorn DD. Respondent‐driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl 1997;44:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jennings J. The state of black Boston: A select demographic and community profile. Boston:William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bazeley P, Jackson K. Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. London: Sage Publications Limited, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23. George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e16–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1231–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Proser M. Deserving the spotlight: Health centers provide high‐quality and cost‐effective care. J Ambul Care Manage 2005;28:321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Politzer RM, Yoon J, Shi L et al. Inequality in America: The contribution of health centers in reducing and eliminating disparities in access to care. Med Care Res Rev 2001;58:234–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The New York Times. Mapping Segregation, 2015. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/07/08/us/census-race-map.html. Accessed June 21, 2017.