Summary

Sustained spermatogenesis in adult males and fertility recovery following germ cell depletion are dependent on undifferentiated spermatogonia. We previously demonstrated a key role for the transcription factor SALL4 in spermatogonial differentiation. However, whether SALL4 has broader roles within spermatogonia remains unclear despite its ability to co-regulate genes with PLZF, a transcription factor required for undifferentiated cell maintenance. Through development of inducible knockout models, we show that short-term integrity of differentiating but not undifferentiated populations requires SALL4. However, SALL4 loss was associated with long-term functional decline of undifferentiated spermatogonia and disrupted stem cell-driven regeneration. Mechanistically, SALL4 associated with the NuRD co-repressor and repressed expression of the tumor suppressor genes Foxl1 and Dusp4. Aberrant Foxl1 activation inhibited undifferentiated cell growth and survival, while DUSP4 suppressed self-renewal pathways. We therefore uncover an essential role for SALL4 in maintenance of undifferentiated spermatogonial activity and identify regulatory pathways critical for germline stem cell function.

Keywords: germline stem cells, self-renewal, transcription factors, tumor suppressor genes, spermatogonia, SALL4

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Undifferentiated but not differentiating spermatogonia tolerate loss of SALL4

-

•

Long-term function of Sall4-deleted undifferentiated cells is compromised

-

•

SALL4 directly represses the tumor suppressor genes Foxl1 and Dusp4

-

•

FOXL1 and DUSP4 disrupt spermatogonial proliferation and self-renewal pathways

In this article, Hobbs and colleagues characterize a critical role for the transcription factor SALL4 in maintenance of undifferentiated spermatogonia in the testis. While undifferentiated cells initially tolerated acute Sall4 deletion, they were progressively depleted over time. SALL4 regulated undifferentiated cell function by repressing Dusp4 and Foxl1, which suppressed cell proliferation and survival and blocked self-renewal signals when aberrantly expressed.

Introduction

Maintenance of male fertility is dependent on germline stem cells within the testis seminiferous epithelium. Stem cell activity in the mouse is restricted to a population of undifferentiated spermatogonia (Figure 1A), generated postnatally from gonocytes (de Rooij and Grootegoed, 1998). The undifferentiated population consists of isolated A-type spermatogonia (Asingle or As) and cells remaining interconnected by cytoplasmic bridges after division; two-cell cysts are Apaired (Apr), while cysts of four or more cells are Aaligned (Aal). Steady-state self-renewal is restricted to cells expressing glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor receptor α1 (Gfra1), predominantly As and Apr (Hara et al., 2014). The majority of undifferentiated cells, particularly Aal, act as committed progenitors and express neurogenin 3 (Ngn3) and retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ, Rarg) (Ikami et al., 2015). Switching from stem to progenitor fates involves RARγ and sensitivity to the differentiation stimulus retinoic acid (RA) (Gely-Pernot et al., 2015, Ikami et al., 2015). Differentiation is marked by induction of c-KIT plus DNA methyltransferases 3A/3B (DNMT3A/3B) and formation of A1 cells that undergo rounds of mitosis to generate A2, A3, A4, intermediate (In), and B spermatogonia that enter meiosis and form pre-leptotene spermatocytes (Figure 1A) (de Rooij and Grootegoed, 1998, Shirakawa et al., 2013).

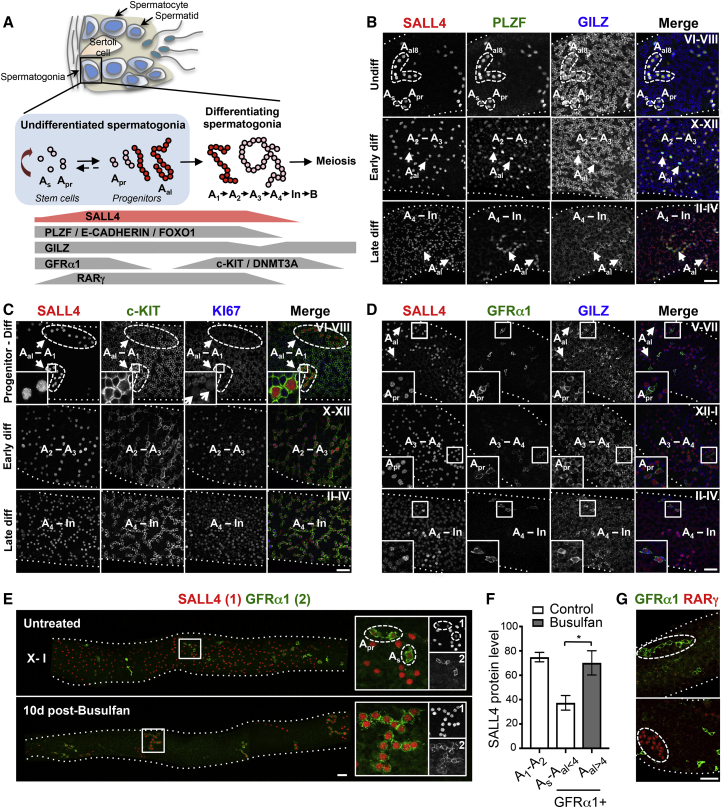

Figure 1.

Expression of SALL4 in Spermatogonia of Undisturbed and Regenerating Testis

(A) Schematic illustrating mouse seminiferous epithelium, spermatogonial hierarchy, and markers of populations.

(B–D) Representative whole-mount IF of wild-type (WT) adult seminiferous tubules. Inset in (C) shows low KI67 in SALL4+ Aal–A1 (arrowheads). Arrowheads in (B) and (D) indicate Aal cysts. Insets in (D) show SALL4 in GFRα1+ As and Apr. Dashed outlines indicate SALL4+ cysts.

(E) Representative whole-mount IF of untreated and busulfan-treated WT mice. Images were taken along the tubule then stitched together. Grayscale of each channel within the indicated regions are shown.

(F) SALL4 staining intensity from (E) using ImageJ. For controls, SALL4 was measured in GFRα1+ As, Apr, and Aal<4, and GFRα1− A1–A2. For busulfan-treated mice, SALL4 was measured in GFRα1+ Aal>4. Mean values ± SEM are shown (n = 4 mice per condition). At least 100 cells were analyzed from controls and 40 from busulfan-treated mice. ∗p < 0.05.

(G) Representative whole-mount IF demonstrating mutually exclusive GFRα1 and RARγ expression in cysts of regenerating tubules from (E).

Scale bars, 50 μm. Dotted lines indicate tubule profile. See also Figure S1.

Undifferentiated cell self-renewal requires glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) produced by supporting Sertoli cells, which signals via GFRα1 and c-RET receptors (Kanatsu-Shinohara and Shinohara, 2013). In the presence of GDNF and basic fibroblast growth factor, undifferentiated cells can be propagated in vitro while maintaining stem cell capacity. The transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) is an intrinsic regulator of spermatogonial self-renewal (Buaas et al., 2004, Costoya et al., 2004, Hobbs et al., 2010). We have identified a connection between PLZF and the zinc-finger transcription factor spalt-like 4 (SALL4) (Hobbs et al., 2012). SALL4 is essential for development and core transcription factor in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (Lim et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2006). In adults, Sall4 expression is restricted to the germline and detected within undifferentiated spermatogonia (Hobbs et al., 2012). Conditional Sall4 deletion suggested a role in spermatogonial differentiation associated with an ability of SALL4 to sequester PLZF and modulate PLZF targets (Hobbs et al., 2012). Culture-based studies suggest that SALL4 and PLZF coordinately regulate genes involved in GDNF-dependent self-renewal (Lovelace et al., 2016). However, the role of SALL4 within undifferentiated spermatogonia remains unclear.

Through development of a Sall4-inducible knockout (KO) model, here we uncover a critical role for SALL4 in undifferentiated cell function and demonstrate that SALL4 suppresses tumor suppressor genes in order to maintain stem cell activity.

Results

Sall4 Is Dynamically Expressed during Spermatogonial Differentiation and Regeneration

As Sall4 expression pattern in adult spermatogonia remains unclear (Gassei and Orwig, 2013, Hobbs et al., 2012), we analyzed whole-mount seminiferous tubules by immunofluorescence (IF) (Figure 1A). Spermatogenesis is a cyclic process divided into 12 stages in the mouse (I-XII) and tubules at a given stage contain cells at a specific differentiation step (Figure S1) (de Rooij and Grootegoed, 1998). Undifferentiated spermatogonia are present at all stages. To assist with cell identification, samples were counterstained for glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ), which marks spermatogonia and early spermatocytes (Figures 1A and S1) (Ngo et al., 2013).

Sall4 expression was compared with Plzf, which is expressed in undifferentiated spermatogonia and early differentiating cells (A1–A3) then downregulated (Figures 1A and S1) (Hobbs et al., 2012). Aal and early differentiating cells expressed Plzf and Sall4, while PLZF + As and Apr had lower SALL4 (Figure 1B). At late differentiating stages (A4–In), PLZF was barely detectable but SALL4 levels were similar to those in As and Apr. SALL4 thus marks all spermatogonia but expression peaks in progenitors and early differentiation stages (Figure 1A), consistent with RA-dependent regulation (Gely-Pernot et al., 2015). Sall4 expression in differentiating cells was confirmed by c-KIT staining (Figure 1C) (Schrans-Stassen et al., 1999). Differentiating cells were also strongly positive for KI67, demonstrating mitotic activity (Figure 1C). Importantly, self-renewing GFRα1+ As and Apr invariably expressed Sall4 although at lower levels than progenitors (Figures 1D and 1E). Sall4 expression is compatible with roles in both self-renewing and differentiating cells.

To test whether Sall4 expression in self-renewing cells was affected by cellular activity, we treated mice with the DNA-alkylating agent, busulfan, which depletes differentiating cells plus much of the undifferentiated pool and induces regeneration from remaining stem cells (Zohni et al., 2012). This response is characterized by formation of GFRα1+ Aal of 8 and 16 cells, potentially involved in stem cell recovery (Nakagawa et al., 2010). SALL4 was upregulated in regenerative GFRα1+ Aal compared with steady-state GFRα1+ As and Apr (Figures 1E and 1F), suggesting a role in germline regeneration. Regenerative GFRα1+ Aal were RARγ− (Figure 1G), indicating retention of self-renewal capacity (Ikami et al., 2015).

Differential Sensitivity of Undifferentiated and Differentiating Spermatogonia to Sall4 Ablation

To assess SALL4 function in adults, we developed an inducible Sall4 KO by crossing floxed mice with a line expressing tamoxifen (TAM)-regulated Cre from the ubiquitin C promoter (UBC-CreER) (Ruzankina et al., 2007). While TAM treatment of Sall4flox/flox UBC-CreER mice (Sall4TAM−KO) induces body-wide Sall4 deletion, Sall4 expression in adults is restricted to spermatogonia, thus allowing assessment of function within these cells. To assess UBC-CreER activity, we crossed UBC-CreER mice with a Z/EG reporter that expresses GFP upon Cre-mediated recombination (Novak et al., 2000). Seven days after TAM, GFP was induced in GFRα1+ As and Apr, SALL4+ progenitors and c-KIT+ cells, confirming transgene activity throughout the spermatogonial hierarchy (Figures 2A and S2A). GFP was detected in spermatocytes and spermatids but absent from Sertoli cells (Figure S2A). PLZF+ cells expressed GFP at 7 and 60 days post-TAM, demonstrating stable lineage marking of the undifferentiated pool (Figure S2B). GFP was expressed throughout the epithelium at day 60, confirming transgene expression in stem cells (Figures S2B and S2C) (Nakagawa et al., 2010).

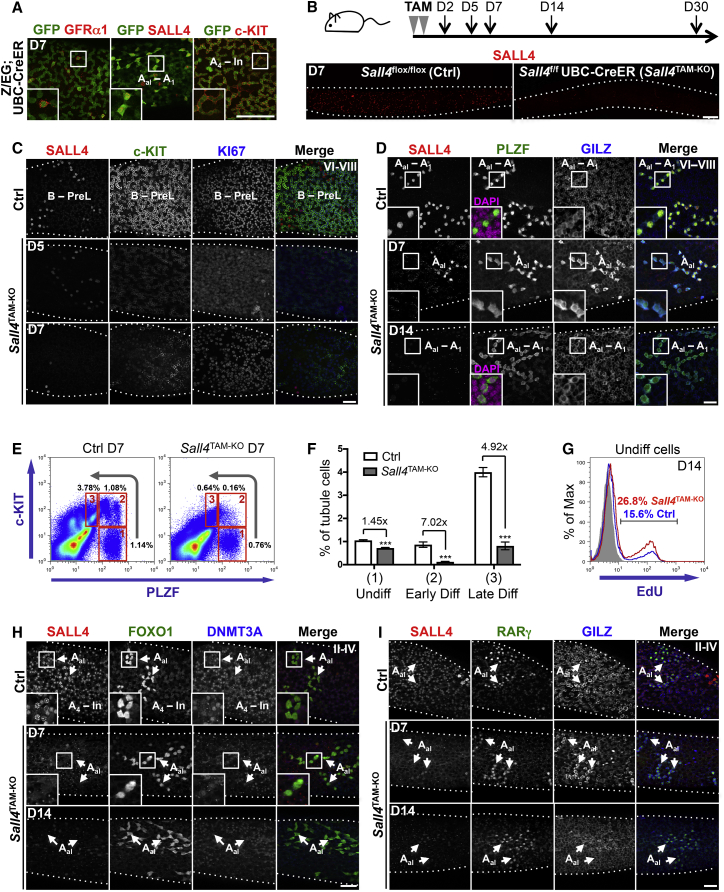

Figure 2.

Effects of Acute Sall4 Deletion on Spermatogonial Populations In Vivo

(A) Representative whole-mount IF of Z/EG; UBC-CreER tubules 7 days after TAM.

(B) Adult Ctrl and Sall4TAM−KO mice were treated with TAM and harvested at the indicated time points. Lower panels: representative whole-mount IF of seminiferous tubules 7 days post-TAM.

(C) Representative whole-mount IF of seminiferous tubules 5 and 7 days post-TAM. Three mice per genotype were analyzed at 5 days and seven per genotype at 7 days. Day 7 control tubules are shown. PreL denotes preleptotene spermatocytes.

(D) Representative whole-mount IF of tubules 7 and 14 days post-TAM. Seven mice per genotype were analyzed. Day 14 control tubules are shown. Insets demonstrate PLZF localization and DAPI identifies nuclei.

(E and F) Flow cytometry of testis cells from Ctrl and Sall4TAM−KO mice 7 days post-TAM. Populations no. 1 are undifferentiated cells, no. 2 early differentiating cells, and no. 3 late differentiating cells. Graph shows mean percentage of cells in each population ± SEM. Four mice per genotype were analyzed. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(G) Representative flow cytometry of EdU incorporation by undifferentiated cells (PLZF+ c-KIT−) from Ctrl and Sall4TAM−KO mice 14 days post-TAM as in (E). Only SALL4− cells are included from Sall4TAM−KO. Percentages of cells EdU+ are indicated.

(H and I) Representative whole-mount IF of seminiferous tubules 7 and 14 days post-TAM. Day 7 control tubules are shown. Arrowheads in Sall4TAM−KO indicate Sall4 null progenitor cysts.

Scale bars, 50 μm. Dotted lines indicate tubule profiles. See also Figures S2 and S3.

Sall4TAM−KO and Sall4flox/flox control mice were treated with TAM and harvested at different time points (Figure 2B). Depletion of SALL4+ cells in Sall4TAM−KO testis by 7 days post-TAM indicated effective gene deletion (Figure 2B). Some SALL4+ cells remained, in agreement with mosaic UBC-CreER activity (Ruzankina et al., 2007). Consistent with a role for SALL4 in maintenance of differentiating cells (Hobbs et al., 2012), Sall4 deletion triggered almost complete ablation of c-KIT+ KI67+ spermatogonia (Figure 2C). Depletion of c-KIT+ cells in Sall4TAM−KO testis was evident 5 days post-TAM but not at day 2 when SALL4 was still detected (Figures 2C and S2D). While control and Sall4TAM−KO tubules were compared at similar cycle stages, staging was not always possible in KOs due to loss of differentiating cells. In contrast, PLZF+ undifferentiated cells were readily detectable in KOs up to 14 days post-TAM (Figure 2D). From sections 7 days after TAM, 91.5% ± 4.37% of PLZF+ cells were SALL4+ in controls, while 13.0% ± 5.01% were SALL4+ in Sall4TAM−KO mice (n = 3), confirming gene deletion. Kinetics of Sall4 deletion in undifferentiated and differentiating cells post-TAM was similar (Figure S2E).

When comparing Sall4-deleted and Sall4-retaining PLZF+ cells in the KO, a shift in PLZF localization was apparent (Figure 2D). In SALL4+ spermatogonia, PLZF was predominantly nuclear but 7 days post-TAM was present in cytosol and nucleus of Sall4-deleted cells. Re-localization of PLZF to the cytosol in Sall4-deleted cells was particularly evident 14 days after TAM, indicating that SALL4 loss disrupts PLZF function (Figures 2D and S2F).

To quantify spermatogonial abundance, fixed and permeabilized testis cells 7 days post-TAM were stained for PLZF, c-KIT, and SALL4, and analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 2E) (Hobbs et al., 2012, Hobbs et al., 2015). Undifferentiated cells are PLZF+ c-KIT− (population no. 1), early differentiating cells (A1–A2) PLZF+ c-KIT+ (no. 2), and late differentiating cells (A3–In) PLZFlow c-KIT+ (no. 3). Abundance of early and late differentiating cells was dramatically reduced upon Sall4 deletion, while the undifferentiated population was intact (Figures 2E and 2F). Comparable results were obtained 5 and 14 days after TAM (Figures S3A–S3C). Sall4-deleted undifferentiated cells at 7 and 14 days post-TAM incorporated EdU to a similar extent as controls, demonstrating mitotic activity (Figures 2G and S3D). Sall4 KO in undifferentiated cells was confirmed (Figure S3E). Undifferentiated cells therefore tolerate acute SALL4 ablation while differentiating cells cannot. Notably, germline Sall4 deletion is associated with apoptosis of differentiating cells (Hobbs et al., 2012).

To confirm effects of Sall4 deletion, we analyzed independent spermatogonial markers (Figure 1A). DNMT3A+ cells were depleted following Sall4 deletion, confirming loss of differentiating cells (Figure 2H) (Shirakawa et al., 2013). FOXO1+ SALL4− spermatogonia were present in Sall4TAM−KO mice 7 and 14 days after TAM, demonstrating retention of Sall4-deleted undifferentiated cells (Figure 2H) (Goertz et al., 2011). RARγ+ SALL4− progenitors also remained following TAM, suggesting that differentiation-primed cells do not require SALL4 for maintenance while fully committed cells do (Figure 2I) (Ikami et al., 2015); consistent with abundant Sall4-deleted Aal (Figures 2D and 2H).

SALL4 Is Required for Long-Term Maintenance of Germline Stem Cell Activity

While undifferentiated spermatogonia persisted following Sall4 deletion, steady-state stem cells comprise a minor component and the effects of SALL4 loss on stem cell function were not immediately evident. In Sall4TAM−KO testis 7 days after TAM, Sall4-deleted GFRα1+ self-renewing cells were present, but an increased proportion were four- and eight-cell Aal, resembling a regenerative response (Figures 3A and 3B). Such a response is expected given the depletion of a large fraction of spermatogonia. Kinetics of SALL4 ablation in GFRα1+ and PLZF+ cells was similar (Figures S2E and S4). As with busulfan, induction of GFRα1+ Aal upon Sall4 deletion was transient and not evident 14 days post-TAM (not shown) (Nakagawa et al., 2010).

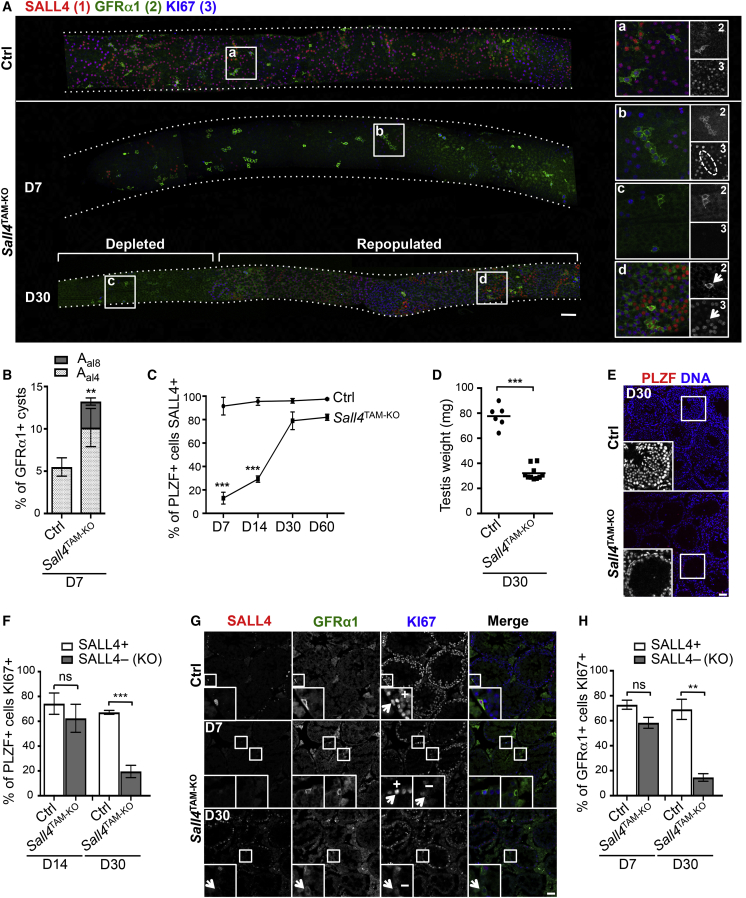

Figure 3.

SALL4 Is Required for Long-Term Maintenance of Spermatogonial Stem Cell Activity

(A) Representative whole-mount IF of seminiferous tubules from Ctrl and Sall4TAM−KO mice 7 and 30 days post-TAM. Images were taken along the tubule and stitched together. Seven mice per genotype were analyzed at 7 days and three per genotype at 30 days. Day 7 control tubules are shown. Regions of germ cell-depleted and recovering Sall4TAM−KO tubules at 30 days are indicated. Dashed outline in “b” indicates a GFRα1+ KI67+ Sall4-deleted regenerative Aal. Arrowheads in “d” mark a Sall4-retaining GFRα1+ As. Dotted lines indicate tubule profiles.

(B) Quantification of GFRα1+ cells/cysts that were Aal4 and Aal8 from the 7-day time point of (A). Three mice per genotype were analyzed and >2 cm of tubules scored per sample. Mean values ± SEM are shown.

(C) Quantification of PLZF+ cells expressing SALL4 in Ctrl and Sall4TAM−KO testis sections at indicated time points post-TAM. Three mice per genotype were analyzed at each time point and 100 PLZF+ cells scored per sample. Mean values ± SEM are shown.

(D) Testis weights of Ctrl and Sall4TAM−KO adult mice 30 days post-TAM. Horizontal bars represent the mean. Three Ctrl and five Sall4TAM−KO mice were analyzed.

(E) Representative IF of Ctrl and Sall4TAM−KO testis sections 30 days post-TAM. Inset shows DAPI stain of a tubule portion.

(F) Percentage of PLZF/SALL4+ cells from Ctrl testis sections and PLZF+ SALL4− (KO) cells from Sall4TAM−KO sections KI67+ 14 and 30 days post-TAM. Mean values ± SEM are shown. Four mice per genotype were analyzed at each time point and 100 PLZF+ cells scored per sample. ns, not significant.

(G) Representative IF of Ctrl and Sall4TAM−KO testis sections 7 and 30 days post-TAM. Arrowheads in insets refer to GFRα1+ cells scored as KI67+ and KI67−. Three mice per genotype were analyzed at each time point.

(H) Percentage of GFRα1+ cells KI67+ from (G) scored as in (F). Mean values ± SEM are shown. Three mice per genotype were analyzed at each time point and ≥30 GFRα1+ cells scored per sample.

∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; not significant (ns) p > 0.05. Scale bars, 50 μm. See also Figure S4.

At 30 days post-TAM, KO tubules contained regions of active spermatogenesis interspersed with areas almost devoid of germ cells (Figure 3A). Repopulated areas contained SALL4+ spermatogonia, indicating that germline recovery was mediated by Sall4-retaining stem cells. Occasional Sall4-deleted GFRα1+ cells were found but appeared unable to contribute to regeneration. Therefore, while undifferentiated cells tolerate SALL4 loss, they are functionally compromised as they are progressively depleted and replaced by Sall4-retaining cells. Accordingly, <15% of PLZF+ cells express Sall4 in KO testis 7 days post-TAM, but ∼80% are SALL4+ by day 30 (Figure 3C). Despite expansion of Sall4-retaining cells, Sall4TAM−KO testis weights at day 30 were lower than controls, indicating incomplete recovery of the seminiferous epithelium (Figures 3D and 3E).

Undifferentiated spermatogonia initially remained mitotically active following Sall4 deletion, but were gradually depleted suggesting defective self-renewal. While increased apoptosis may contribute to depletion of Sall4 KO undifferentiated cells (Hobbs et al., 2012), mitotic potential of Sall4-deleted PLZF+ cells declined over time as indicated by KI67 staining (Figure 3F). The majority of Sall4 KO GFRα1+ cells remaining 30 days post-TAM were KI67−, despite abundant Sall4-depleted KI67+ GFRα1+ cells 7 days post-TAM (Figures 3A, 3G, and 3H). These data indicate that Sall4 loss disrupts long-term proliferative capacity and maintenance of undifferentiated spermatogonia.

SALL4 Function within the Spermatogonial Pool Is PLZF Independent

SALL4 is suggested to associate with target genes indirectly via interaction with PLZF and other factors (Lovelace et al., 2016). PLZF loss should thus disrupt SALL4 function. However, nuclear retention of PLZF is SALL4 dependent (Figures 2D and S2F), indicating that SALL4 loss disrupts PLZF function. To test whether SALL4 requires PLZF to exert its function and whether disruption in PLZF activity contributes to the Sall4 KO phenotype, we crossed Sall4TAM−KO mice onto a Plzf −/− background and compared effects of Sall4 deletion in the presence and absence of PLZF.

Plzf −/− mice are viable but spermatogonial maintenance is disrupted (Costoya et al., 2004, Hobbs et al., 2010). Adult Plzf −/− tubules contained areas of active spermatogenesis interspersed with germ cell-depleted regions (Figure 4A). Spermatogenic regions occupied 53.6% ± 2.45% of the tubules (n = 3, ≥15 mm scored/mouse). Plzf −/−, Sall4TAM−KO, and Plzf −/− controls were treated with TAM, and then spermatogenic areas (containing GILZ+ germ cells) were analyzed 10 days later. While c-KIT+ differentiating cells were present in Plzf −/− tubules, Sall4 deletion in a Plzf −/− background resulted in c-KIT+ cell depletion, as occurs in a wild-type (WT) background (Figure 4B). E-cadherin+ undifferentiated cells were largely unaffected by Sall4 deletion in a Plzf −/− background, as when Plzf is expressed (Figure 4C) (Tokuda et al., 2007). Sall4/Plzf KO undifferentiated cells were often KI67+ indicating mitotic activity. As in a WT setting, GFRα1+ stem cells persisted following Sall4 loss in a Plzf −/− background and were often Aal, suggesting a regenerative response (Figure 4D). GFRα1+ cells were primarily As and Apr in Plzf −/− controls.

Figure 4.

Analysis of Plzf KO and Plzf/Sall4 Double KO Spermatogonial Phenotype

(A) Representative whole-mount IF of seminiferous tubules from WT and Plzf−/− mice. Images taken along the tubule were stitched together. Areas of intact and germ cell-depleted (degenerated) seminiferous epithelium are indicated.

(B–D) Representative whole-mount IF of Plzf−/− and Plzf−/−; Sall4TAM−KO tubules 10 days post-TAM. Three Plzf−/− and four Plzf−/−Sall4TAM−KO mice were analyzed. Arrowheads in (C) indicate Sall4-expressing (upper panels) and Sall4 KO (lower panels) undifferentiated cells. Dashed line in (D) indicates regenerative GFRα1+ Aal.

Scale bars, 50 μm. Dotted lines indicate tubule profiles.

Acute response of spermatogonia to Sall4 deletion was similar whether Plzf was expressed or not, suggesting that SALL4 function is independent of PLZF. Effects of Sall4 deletion on long-term undifferentiated cell maintenance in a Plzf −/− background was difficult to assess as Plzf loss itself causes germline depletion. However, undifferentiated cells remained active in Plzf −/− tubules at 6–8 weeks, while undifferentiated cell function was lost within 30 days of Sall4 deletion (Figure 3A), supportive of a PLZF-independent role. In addition, alterations in PLZF activity do not contribute substantially to the Sall4 KO phenotype. Given PLZF induction during spermatogonial development (Costoya et al., 2004), Plzf −/− undifferentiated cells may be developmentally abnormal. Definitive assessment of the role of PLZF in adult undifferentiated cells awaits an inducible KO model.

Identification of SALL4 Targets in Undifferentiated Spermatogonia

Having uncovered a role for SALL4 in undifferentiated cells, we sought to define relevant targets. Cultures of undifferentiated spermatogonia were generated from untreated Sall4TAM−KO adults that allowed Sall4 ablation in vitro (Figure 5A) (Hobbs et al., 2010, Seandel et al., 2007). Transplantation of GFP-labeled WT lines confirmed stem cell maintenance in vitro (Figure S5A). Cultured Sall4TAM−KO cells expressed Plzf, Sall4, Gfra1 and Gilz (Figure 5B). Sall4 was deleted in >90% of cells by 4-hydroxy-TAM, while expression of Plzf, Gfra1 and Gilz, were maintained (Figure 5B). PLZF became predominantly cytosolic upon Sall4 deletion (Figure 5B), as in vivo.

Figure 5.

Identification of SALL4 Targets Using Cultured Undifferentiated Spermatogonia

(A) Method for generating cultures of undifferentiated spermatogonia. Spermatogonia were enriched from Sall4TAM−KO testis cell suspensions by αCD9 magnetic selection and plated onto mitotically inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF). Colonies formed within 1–2 weeks and passaged cells were treated with vehicle (Veh) or 4-hydroxytamoxifen (TAM) then analyzed 4 days later.

(B) Representative IF of Veh and TAM-treated Sall4TAM−KO cultures as in (A). Grayscale insets show PLZF localization.

(C) Representative images of Veh and TAM-treated Sall4TAM−KO cultures as in (B). Insets show higher magnification of indicated areas. Mean numbers of cleaved-PARP+ cells per colony are in upper graph. Fifty colonies scored per culture and condition. Lower graph shows relative KI67 levels quantified using ImageJ. One hundred cells scored per culture and condition. Mean values ± SEM from three independent cultures are shown.

(D) qRT-PCR of SALL4-regulated genes from microarray analysis. Sall4TAM−KO cultures were treated with Veh or TAM as in (B). mRNA levels are corrected to b-actin and normalized to Veh-treated sample. Levels of germline marker Ddx4/Vasa and undifferentiated cell marker Pou5f1/Oct4 are included as controls. Five independent cultures were analyzed. Mean values are shown ± SEM.

(E) Western blot of three independent Sall4TAM−KO cultures treated as in (B). Molecular weights (kDa) are indicated. VASA and β-ACTIN were used as loading controls.

(F and G) Representative IF of Sall4TAM−KO cultures treated as in (B). Dashed line indicates Sall4-deleted cells expressing high DUSP4 levels.

(H) Representative flow cytometry of Ctrl and Sall4TAM−KO testis cells 7 days post-TAM. Percentages of EpCAM+ cells within c-KIT− α6-integrin+ undifferentiated gate are indicated.

(I) qRT-PCR of SALL4-regulated genes in undifferentiated cells isolated as in (H). mRNA levels are corrected to b-actin and normalized to Ctrl. Ddx4/Vasa and Pou5f1/Oct4 are included as controls. Mean values ± SEM are shown (n = 6 mice per genotype).

∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Scale bars, 50 μm. See also Figure S5 and Table S1.

A large fraction of cultured Sall4TAM−KO cells persisted following Sall4 deletion, but increased cleaved-PARP+ apoptotic cells were evident 4 days after TAM compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figure 5C). Proliferation was inhibited as demonstrated by KI67 (Figure 5C). Cleaved-PARP+ cells were observed infrequently in TAM-treated cultures from UBC-CreER mice, and KI67 levels were unaffected, excluding Cre-dependent effects (Figure S5B). While effects of Sall4 deletion were more pronounced in culture than in vivo, our data confirm that undifferentiated cell survival and mitotic activity are SALL4 dependent.

To characterize SALL4 targets, TAM-treated Sall4TAM−KO cultures were analyzed by microarray (Table S1). Expression of 496 annotated genes was altered in Sall4-depleted cells. Identified genes are involved in metabolic, cellular, and developmental processes (Figure S5C). Altered expression of a selection was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure 5D). Candidates were selected according to roles in proliferation and apoptosis (Card11, Fbxw13, Foxl1, Id1, Pmaip1, and Tox3), transcriptional regulation (Dmrt2, Egr1, Gfi1, and Onecut2), and signaling (Dusp4 and Inpp5a). SALL4 targets in ESCs (Ctgf, Dusp4, Ifitm1, Klf5, Tdgf1, and Upp1) and genes with roles in undifferentiated spermatogonia (Cxcl12 and Ddit4/Redd1) were included (Hobbs et al., 2010, Kanatsu-Shinohara and Shinohara, 2013, Lim et al., 2008, Rao et al., 2010). Ddx4 (Vasa) and Pou5f1 (Oct4), markers of germline and undifferentiated cells, respectively, were used as controls (Hobbs et al., 2010). While changes in candidate mRNA were confirmed, expression of some genes (Id1, Egr1, Klf5, and Onecut2) was not affected at the protein level (Figure 5E). Importantly, Dusp4, Foxl1, and Gfi1 were upregulated at mRNA and protein levels in Sall4-deleted cells (Figures 5D and 5E). Transcription factor FOXL1 was low in vehicle-treated cells by IF but upregulated upon Sall4 deletion (Figure 5F). The phosphatase DUSP4 was detectable in a subset of control cells but elevated in Sall4-deleted cells (Figure 5G). TAM-treated UBC-CreER cells did not upregulate FOXL1 or DUSP4, controlling for effects of Cre (Figures S5D and S5E).

We next validated whether Sall4 loss in vivo was associated with altered expression of candidates. Respective antibodies performed poorly in tissue IF, so undifferentiated cells were sorted from TAM-treated Sall4TAM−KO and Sall4flox/flox mice for qRT-PCR. The EpCAM+ c-KIT− α6-integrin+ testis fraction comprises a pure population of PLZF+ undifferentiated cells with transplantation capabilities (Takubo et al., 2008). We confirmed enrichment of Gfra1-expressing cells in this fraction, and also high levels of CD9, a stem cell-associated marker (Figures S5F–S5H) (Kanatsu-Shinohara et al., 2004). EpCAM+ c-KIT− α6-integrin+ cells were present as anticipated in Sall4TAM−KO testis 7 days post-TAM, while c-KIT+ differentiating populations were disrupted (Figures 5H and S5I). Genes aberrantly expressed upon Sall4 deletion in vitro (Dusp4, Egr1, Fbxw13, Foxl1, Gfi1, Id1, Inpp5a, and Onecut2) displayed similar perturbations in sorted undifferentiated cells (Figure 5I). Combined, our data revealed SALL4-regulated genes in undifferentiated spermatogonia.

SALL4 Inhibits Foxl1 and Dusp4 Expression by Binding Proximal Promoter Elements

Notable genes were aberrantly expressed in undifferentiated cells upon Sall4 loss. Foxl1 (forkhead box L1) encodes a transcription factor with pro-apoptotic and growth-suppressive roles (Chen et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2013). Dusp4 (dual specificity phosphatase 4) encodes an inhibitor of MAPK signaling that promotes senescence (Hijiya et al., 2016, Schmid et al., 2015, Tresini et al., 2007). Growth-suppressive roles of FOXL1 and DUSP4 in multiple cell types suggested that increased expression would disrupt undifferentiated cell activity. We next tested the ability of SALL4 to regulate these genes and effects of increased expression on undifferentiated cells.

Genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) approaches indicated that SALL4 associates with Dusp4 regulatory regions in ESCs and Dusp4 and Foxl1 promoters in some spermatogonial samples (Lim et al., 2008, Lovelace et al., 2016). However, the ability of SALL4 to target these genes has not been confirmed. As distinct SALL4 DNA binding motifs have been characterized in ESCs and spermatogonia (Lim et al., 2008, Lovelace et al., 2016, Rao et al., 2010), we analyzed Foxl1 and Dusp4 promoters for SALL4 recognition elements. Motifs from spermatogonia were present around and upstream of transcription start sites (TSS) of both genes, while motifs from ESCs were not (Figures 6A and 6B). As SALL4 may bind genes indirectly through PLZF and DMRT1, we scanned promoters for PLZF and DMRT1 sites (Lovelace et al., 2016). The Foxl1 promoter contained one PLZF site, but that of Dusp4 did not contain motifs for either factor. To confirm that Foxl1 and Dusp4 are SALL4 targets, we performed ChIP-qPCR using WT undifferentiated cultures (Figures 6A and 6B). To control for non-specific chromatin pull-down, we measured SALL4 binding to H1foo, an oocyte-expressed gene not bound by SALL4 together with immunoglobulin G (IgG) controls (Yuri et al., 2009). SALL4 associated with regions around the Foxl1 TSS and Dusp4 promoter 0.25-1 kb upstream of the TSS. As a positive control, we analyzed SALL4 binding to known targets Sall1 and Sall3 (Hobbs et al., 2012, Lim et al., 2008, Lovelace et al., 2016). While SALL4 associated with Sall1 and Sall3 promoters plus intronic regions, gene expression was not altered upon Sall4 loss (Figures 6C, S6A, and S6B). Thus, gene binding is not invariably predictive of SALL4-dependent regulation.

Figure 6.

SALL4 Targets Regulate Activity of Cultured Undifferentiated Spermatogonia

(A–C) Analysis of SALL4 binding to Foxl1 (A), Dusp4 (B), and Sall3 (C) in WT cultured undifferentiated cells by ChIP-qPCR. Top panels depict promoter regions and first exon (E1) of genes. Arrows indicate transcription start sites (TSS) and red bars ChIP amplicons. Blue lines are SALL4 binding motifs and green lines PLZF motifs from cultured spermatogonia. Orange lines are SALL4 motifs from ESCs. Graphs show relative enrichment of amplicons from four independent lines normalized to negative control region of H1foo not targeted by SALL4 (-ve Ctrl). IgG controls are included. Mean values ± SEM are shown.

(D) Identification of SALL4 interacting proteins in undifferentiated spermatogonia. Lysates were incubated with magnetic beads conjugated to SALL4 antibody or IgG (control). Immunoprecipitated proteins were identified by MS.

(E) Summary of SALL4-associated proteins from three combined runs from (D).

(F) Confirmation of SALL4-interacting proteins by SALL4 IP from WT cultures and WB. Non-specific IgG control is shown.

(G) WT cultured undifferentiated cells infected with lentivirus containing Myc-tagged Foxl1 and Dusp4. Cells were passaged 2 days after infection and allowed to form colonies for 10 days before analysis. Infection efficiency was 30%–40%. Representative IF of infected cells is shown. Insets: uninfected control cells.

(H) Relative mean colony size of infected cells (+) versus uninfected cells (−) in cultures from (G). Mean values ± SEM are shown (n = 4 lines of infected cells). GFP-infected cells were included as controls.

(I) Representative IF of WT cultures infected with lentivirus containing Myc-tagged Foxl1 or GFP control constructs as in (G). Cells were stained for Myc-tag or GFP to confirm infection (inset).

(J) Relative mean KI67 levels in infected cells from (I) quantified with ImageJ. One hundred cells were quantified from each of six infected WT cultures. Mean values ± SEM are shown.

(K) Representative IF of WT cultures infected with lentivirus containing Myc-tagged Foxl1 and GFP control constructs as in (G). Cleaved caspase-3 staining identified apoptotic cells.

(L) Graph indicates mean number of cleaved caspase-3+ cells per infected spermatogonial colony ± SEM from cultures of (K). One hundred colonies from each of three infected WT cultures were analyzed.

(M) WB of independent WT cultures (no. 1 and no. 2) infected with lentivirus containing Myc-tagged Dusp4 and GFP as in (G). VASA and β-ACTIN were used as loading controls.

(N) Graph indicates relative levels of P-JNK from (M) corrected to total JNK and normalized to GFP-infected cells. Four independent WT cultures were analyzed. Mean values ± SEM are shown.

∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Scale bars, 50 μm. See also Figure S6.

Expression of Foxl1 and Dusp4 was low in controls and induced upon Sall4 deletion (Figures 5F and 5G). Accordingly, the repressive epigenetic marker, trimethyl histone H3 Lys 27 (H3K27Me3), was readily detected on Foxl1 and Dusp4 promoters in WT cells (Figures S6C and S6D). SALL4 can repress genes by recruiting the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase co-repressor (NuRD) complex (Lauberth and Rauchman, 2006, Lu et al., 2009). Mass spectrometry (MS) of SALL4-associated proteins in undifferentiated cultures identified NuRD components plus PLZF and other SALL family proteins (Figures 6D and 6E) (Hobbs et al., 2012, Sakaki-Yumoto et al., 2006), confirmed by immunoprecipitation (IP) and western blot (WB) (Figure 6F). SALL1 was strongly enriched in SALL4 IPs, suggesting that SALL4 functions as a SALL1-SALL4 heterodimer in undifferentiated cells (Sakaki-Yumoto et al., 2006). CBX3 was identified in the MS analysis but was poorly enriched in SALL4 IPs by WB, indicating weak or indirect binding. Our data indicate that SALL4 represses Foxl1 and Dusp4 by binding promoter elements and recruiting NuRD.

Aberrant Foxl1 and Dusp4 Expression Disrupts Activity of Undifferentiated Spermatogonia

Increased expression of Foxl1 and Dusp4 upon Sall4 deletion was predicted to disrupt undifferentiated cell proliferation and survival (Chen et al., 2015, Schmid et al., 2015). To confirm the effects of Foxl1 and Dusp4 we transduced WT cultures with lentivirus containing Myc-tagged constructs (Figure 6G). Compared with GFP-transduced or uninfected controls, colonies from cells overexpressing Foxl1 were smaller, suggesting that FOXL1 inhibits proliferation and/or survival (Figure 6H). Accordingly, Foxl1 overexpression caused reduction in KI67 and increased cleaved caspase-3+ apoptotic cells (Figures 6I–6L). Dusp4 overexpression did not affect colony growth despite its ability to induce cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis via MAPK suppression in other cells (Figure 6H) (Hijiya et al., 2016, Schmid et al., 2015, Tresini et al., 2007). The high growth factor environment in vitro may over-ride negative effects of DUSP4 on MAPK. However, phosphorylated (active) JNK MAPK was decreased in Dusp4-overexpressing cells (Figures 6M, 6N, and S6E). JNK is required for self-renewal downstream of non-canonical Wnt and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Morimoto et al., 2013, Yeh et al., 2011). Although ERK MAPK is a mediator of spermatogonial self-renewal and DUSP4 targets ERK (Hasegawa et al., 2013, Hijiya et al., 2016, Tresini et al., 2007), phospho-ERK levels in Dusp4-transduced and control cells were similar (Figure S6F). Dusp4 thus selectively disrupts self-renewal pathways while Foxl1 inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Aberrant expression of these genes could, in part, account for loss in undifferentiated cell activity following Sall4 deletion.

Discussion

Through development of an inducible Sall4 KO model, we characterized effects of acute Sall4 deletion on adult spermatogonial function. Besides confirming a key role for SALL4 in differentiation (Hobbs et al., 2012), we find that long-term maintenance of undifferentiated cell function is SALL4-dependent and implicates targets Foxl1 and Dusp4 as stem cell regulators (Figure 7). In contrast to rapid depletion of differentiating spermatogonia following Sall4 deletion, undifferentiated cells tolerated SALL4 loss. Coincident with differentiating cell depletion, a regenerative response was initiated from Sall4 KO stem cells characterized by formation of GFRα1+ Aal. However, Sall4-deleted GFRα1+ stem cells lost proliferative capacity over time and were depleted. Spermatogonial recovery was driven from few Sall4-retaining cells. Thus, SALL4 loss does not affect the ability of stem cells to respond to tissue damage but disrupts long-term regenerative capacity.

Figure 7.

SALL4-Dependent Pathways Maintaining Undifferentiated Cell Activity

SALL4 silences Foxl1 and Dusp4 by binding promoter regions and recruiting the NuRD co-repressor. FOXL1 can inhibit spermatogonial proliferation and survival via multiple targets. DUSP4 inhibits JNK, which is required for self-renewal downstream reactive oxygen species (ROS) and non-canonical WNT. Upon Sall4 deletion, FOXL1 and DUSP4 accumulate to block proliferation plus survival and suppress JNK-dependent self-renewal, resulting in progressive stem cell failure.

We characterized two SALL4 targets in undifferentiated cells, Dusp4 and Foxl1, which are tumor suppressors. DUSP4 expression is commonly lost in B cell lymphoma, promoting cell survival by de-repression of JNK (Schmid et al., 2015). Increased DUSP4 expression inhibits ERK and induces senescence, a checkpoint in tumor development (Bignon et al., 2015, Tresini et al., 2007). Both JNK and ERK are linked to spermatogonial self-renewal, although DUSP4 inhibited JNK most effectively in undifferentiated cells (Hasegawa et al., 2013, Morimoto et al., 2013, Yeh et al., 2011). FOXL1 is downregulated in multiple cancers and low expression predicts poor outcome (Chen et al., 2015, Qin et al., 2014, Yang et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2013). Besides promoting growth arrest, FOXL1 induces TRAIL, a mediator of DNA damage-induced apoptosis of undifferentiated spermatogonia (Ishii et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2013). Given conserved roles in spermatogonia, increased Dusp4 and Foxl1 expression upon Sall4 deletion would suppress proliferation, disrupt self-renewal, and promote apoptosis.

Recent studies highlight the complexity of SALL4-dependent gene regulation in spermatogonia (Hobbs et al., 2012, Lovelace et al., 2016). In cultures, SALL4 is co-recruited with PLZF to promoters of genes with roles in undifferentiated cells, including Foxo1, Gfra1, Oct4, and Etv5 (Lovelace et al., 2016). However, expression of these genes was not significantly altered upon Sall4 deletion. PLZF and SALL4 co-bound genomic regions contain PLZF binding sites, indicating that PLZF recruits SALL4 to these targets (Lovelace et al., 2016). However, Sall4 deletion triggered re-localization of PLZF to the cytosol, suggesting that the ability of PLZF to regulate genes is SALL4 dependent. Moreover, response of spermatogonia to SALL4 loss was indistinguishable whether PLZF was present or not, indicating an independent role for SALL4. Further studies are necessary to define the interplay between SALL4, PLZF, and other factors. Interestingly, proximity-ligation assays of WT cultures demonstrated that interaction of SALL4 with PLZF and DMRT1 was highly variable from cell to cell despite homogeneous expression (Figures S6G and S6H), underscoring the dynamic nature of interaction.

While we identify SALL4 targets within undifferentiated cells, it is unclear whether these are relevant for SALL4 function in differentiating cells. SALL4 interacts with DNA methyltransferases, and Sall4 deletion in oocytes results in genomic hypomethylation (Xu et al., 2016, Yang et al., 2012). Given that induction of Dnmt3a and 3b and methylation of self-renewal genes are involved in transition from undifferentiated to differentiated states (Shirakawa et al., 2013), SALL4 may direct methylation of genes that need to be silenced during differentiation. Given that SALL4 is capable of interacting with multiple transcription factors in the germline (Hobbs et al., 2012, Lovelace et al., 2016, Yamaguchi et al., 2015), it will be of interest to characterize the dynamics of SALL4-dependent networks during germ cell maturation.

Experimental Procedures

Mouse Maintenance and Treatment

Sall4flox/flox and Plzf −/− mice are described (Costoya et al., 2004, Sakaki-Yumoto et al., 2006). Ubc-CreER and Z/EG mice were from Jackson Laboratory. For gene deletion and lineage tracing, 6- to 8-week-old mice were injected for two consecutive days with 2 mg TAM (Sigma) in sesame oil intraperitoneally (Matson et al., 2010). To induce regeneration, C57BL/6 adults were injected intraperitoneally with 10 mg/kg busulfan (Cayman Chemical) (Zohni et al., 2012). To detect proliferation, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.4 mg EdU (Thermo Fisher Scientific) 2 hr before harvesting. Transplantation was performed using busulfan-conditioned C57BL6/CBA F1 recipients (Seandel et al., 2007). Cultured cell suspension (10–15 μL) was microinjected via testis efferent ducts. The Monash University Animal Ethics Committee approved animal experiments.

IF

IF of whole mounts, sections, and cultures are as described previously (Hobbs et al., 2012, Hobbs et al., 2015). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Flow Cytometry

Cell preparation for sorting and analysis has been described previously (Hobbs et al., 2012). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Cell Culture

Undifferentiated spermatogonia were cultured on mitomycin-inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblast feeders (Hobbs et al., 2012). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Lentiviral Overexpression

Dusp4 and Foxl1 cDNA (Origene) was sub-cloned by PCR into pCCL-hPGK (Dull et al., 1998). Cultures were infected with lentiviral-containing supernatant (Hobbs et al., 2010). Cells infected with pCCL-hPGK-GFP were used as controls. Colony size was measured using ImageJ.

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

RNA was purified using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Direct-zol MiniPrep Kits (Zymo Research). Tetro cDNA synthesis kits (Bioline) were used for cDNA synthesis. qPCR was run on a Light Cycler 480 (Roche) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara). Primers are in Table S2.

Microarray

RNA was isolated from three independent Sall4TAM−KO cultures treated with TAM or vehicle. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

ChIP

SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kits (Cell Signaling Technologies) were used for ChIP of undifferentiated cultures (Hobbs et al., 2010). Primers are in Table S2. MEME was used to define binding motifs (Machanick and Bailey, 2011). We implemented a threshold for a match of a sequence to a motif by an E value <10, position p value <0.0001, and 90% sequence identity.

CoIP and Western Blotting

CoIP and WB were performed as described previously (Hobbs et al., 2012). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Mass Spectrometry

Lysates from undifferentiated cultures were prepared as described previously (Mathew et al., 2012). SALL4 complexes were immunoprecipitated with Dynabeads coupled with αSALL4 antibody using a Dynabead Coupling Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Dynabeads coupled to rabbit IgG were used for controls. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

In Situ Proximity-Ligation Assay

Cultured spermatogonia on chamber slides were fixed and permeabilized then processed using Duolink In Situ Orange Kits (Sigma-Aldrich).

Statistical Analysis

Assessment of statistical significance was performed with a standard two-tailed t test. Associated p values are indicated as follows: ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001; not significant (ns) p > 0.05.

Author Contributions

A.C., H.M.L., J.M.D.L., J.M., M.R., and R.M.H. conceived and designed the study. A.C., H.M.L., J.M.D.L., J.M., M.S., and R.M.H. performed experiments. A.C., H.M.L., J.M.D.L., M.E., J.M., M.R., and R.M.H. analyzed data. A.C., J.M.D.L., and R.M.H. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ryuichi Nishinakamura for Sall4 floxed mice, Monash Animal Research Platform for animal care, Nicholas Williamson from Bio21 Proteomics Facility for mass spectrometry assistance, Mehmet Özmen of Monash University Statistical Consulting Service for advice on data analysis, and Antonella Papa for helpful discussions. We acknowledge facilities and technical assistance of Monash Micro Imaging, FlowCore, and Monash Health Translation Precinct Medical Genomics Facility. R.M.H. is supported by an ARC Future Fellowship and J.M.D.L. by Stem Cells Australia. J.M. was recipient of a Sigrid Jusélius Foundation Fellowship. M.R. is supported by a NHMRC/Heart Foundation Career Development Fellowship. NHMRC Project Grant APP1046863 to R.M.H. supported this work. The Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute is supported by grants from the State Government of Victoria and Australian Government.

Published: August 31, 2017

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, six figures, and two tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.08.001.

Accession Numbers

The accession number for the microarray data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE98991.

Supplemental Information

References

- Bignon A., Regent A., Klipfel L., Desnoyer A., de la Grange P., Martinez V., Lortholary O., Dalloul A., Mouthon L., Balabanian K. DUSP4-mediated accelerated T-cell senescence in idiopathic CD4 lymphopenia. Blood. 2015;125:2507–2518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-598565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buaas F.W., Kirsh A.L., Sharma M., McLean D.J., Morris J.L., Griswold M.D., de Rooij D.G., Braun R.E. Plzf is required in adult male germ cells for stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:647–652. doi: 10.1038/ng1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Deng M., Ma L., Zhou J., Xiao Y., Zhou X., Zhang C., Wu M. Inhibitory effects of forkhead box L1 gene on osteosarcoma growth through the induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Oncol. Rep. 2015;34:265–271. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costoya J.A., Hobbs R.M., Barna M., Cattoretti G., Manova K., Sukhwani M., Orwig K.E., Wolgemuth D.J., Pandolfi P.P. Essential role of Plzf in maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:653–659. doi: 10.1038/ng1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rooij D.G., Grootegoed J.A. Spermatogonial stem cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1998;10:694–701. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dull T., Zufferey R., Kelly M., Mandel R.J., Nguyen M., Trono D., Naldini L. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J. Virol. 1998;72:8463–8471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassei K., Orwig K.E. SALL4 expression in gonocytes and spermatogonial clones of postnatal mouse testes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gely-Pernot A., Raverdeau M., Teletin M., Vernet N., Feret B., Klopfenstein M., Dennefeld C., Davidson I., Benoit G., Mark M. Retinoic acid receptors control spermatogonia cell-fate and induce expression of the SALL4A transcription factor. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goertz M.J., Wu Z., Gallardo T.D., Hamra F.K., Castrillon D.H. Foxo1 is required in mouse spermatogonial stem cells for their maintenance and the initiation of spermatogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:3456–3466. doi: 10.1172/JCI57984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K., Nakagawa T., Enomoto H., Suzuki M., Yamamoto M., Simons B.D., Yoshida S. Mouse spermatogenic stem cells continually interconvert between equipotent singly isolated and syncytial states. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:658–672. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K., Namekawa S.H., Saga Y. MEK/ERK signaling directly and indirectly contributes to the cyclical self-renewal of spermatogonial stem cells. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2517–2527. doi: 10.1002/stem.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijiya N., Tsukamoto Y., Nakada C., Tung Nguyen L., Kai T., Matsuura K., Shibata K., Inomata M., Uchida T., Tokunaga A. Genomic loss of DUSP4 contributes to the progression of intraepithelial neoplasm of pancreas to invasive carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2612–2625. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs R.M., Fagoonee S., Papa A., Webster K., Altruda F., Nishinakamura R., Chai L., Pandolfi P.P. Functional antagonism between Sall4 and Plzf defines germline progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:284–298. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs R.M., La H.M., Makela J.A., Kobayashi T., Noda T., Pandolfi P.P. Distinct germline progenitor subsets defined through Tsc2-mTORC1 signaling. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:467–480. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs R.M., Seandel M., Falciatori I., Rafii S., Pandolfi P.P. Plzf regulates germline progenitor self-renewal by opposing mTORC1. Cell. 2010;142:468–479. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikami K., Tokue M., Sugimoto R., Noda C., Kobayashi S., Hara K., Yoshida S. Hierarchical differentiation competence in response to retinoic acid ensures stem cell maintenance during mouse spermatogenesis. Development. 2015;142:1582–1592. doi: 10.1242/dev.118695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K., Ishiai M., Morimoto H., Kanatsu-Shinohara M., Niwa O., Takata M., Shinohara T. The Trp53-Trp53inp1-Tnfrsf10b pathway regulates the radiation response of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:676–689. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara M., Shinohara T. Spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal and development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013;29:163–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatsu-Shinohara M., Toyokuni S., Shinohara T. CD9 is a surface marker on mouse and rat male germline stem cells. Biol. Reprod. 2004;70:70–75. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.020867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauberth S.M., Rauchman M. A conserved 12-amino acid motif in Sall1 recruits the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase corepressor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:23922–23931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C.Y., Tam W.L., Zhang J., Ang H.S., Jia H., Lipovich L., Ng H.H., Wei C.L., Sung W.K., Robson P. Sall4 regulates distinct transcription circuitries in different blastocyst-derived stem cell lineages. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelace D.L., Gao Z., Mutoji K., Song Y.C., Ruan J., Hermann B.P. The regulatory repertoire of PLZF and SALL4 in undifferentiated spermatogonia. Development. 2016;143:1893–1906. doi: 10.1242/dev.132761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Jeong H., Kong N., Yang Y., Carroll J., Luo H.R., Silberstein L.E., Yupoma, Chai L. Stem cell factor SALL4 represses the transcriptions of PTEN and SALL1 through an epigenetic repressor complex. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machanick P., Bailey T.L. MEME-ChIP: motif analysis of large DNA datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1696–1697. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R., Seiler M.P., Scanlon S.T., Mao A.P., Constantinides M.G., Bertozzi-Villa C., Singer J.D., Bendelac A. BTB-ZF factors recruit the E3 ligase cullin 3 to regulate lymphoid effector programs. Nature. 2012;491:618–621. doi: 10.1038/nature11548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson C.K., Murphy M.W., Griswold M.D., Yoshida S., Bardwell V.J., Zarkower D. The mammalian doublesex homolog DMRT1 is a transcriptional gatekeeper that controls the mitosis versus meiosis decision in male germ cells. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:612–624. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto H., Iwata K., Ogonuki N., Inoue K., Atsuo O., Kanatsu-Shinohara M., Morimoto T., Yabe-Nishimura C., Shinohara T. ROS are required for mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:774–786. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T., Sharma M., Nabeshima Y., Braun R.E., Yoshida S. Functional hierarchy and reversibility within the murine spermatogenic stem cell compartment. Science. 2010;328:62–67. doi: 10.1126/science.1182868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo D., Cheng Q., O'Connor A.E., DeBoer K.D., Lo C.Y., Beaulieu E., De Seram M., Hobbs R.M., O'Bryan M.K., Morand E.F. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) regulates testicular FOXO1 activity and spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) function. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak A., Guo C., Yang W., Nagy A., Lobe C.G. Z/EG, a double reporter mouse line that expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein upon Cre-mediated excision. Genesis. 2000;28:147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Gong W., Zhang M., Wang J., Tang Z., Quan Z. Forkhead box L1 is frequently downregulated in gallbladder cancer and inhibits cell growth through apoptosis induction by mitochondrial dysfunction. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S., Zhen S., Roumiantsev S., McDonald L.T., Yuan G.C., Orkin S.H. Differential roles of Sall4 isoforms in embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30:5364–5380. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00419-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzankina Y., Pinzon-Guzman C., Asare A., Ong T., Pontano L., Cotsarelis G., Zediak V.P., Velez M., Bhandoola A., Brown E.J. Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaki-Yumoto M., Kobayashi C., Sato A., Fujimura S., Matsumoto Y., Takasato M., Kodama T., Aburatani H., Asashima M., Yoshida N. The murine homolog of SALL4, a causative gene in Okihiro syndrome, is essential for embryonic stem cell proliferation, and cooperates with Sall1 in anorectal, heart, brain and kidney development. Development. 2006;133:3005–3013. doi: 10.1242/dev.02457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid C.A., Robinson M.D., Scheifinger N.A., Muller S., Cogliatti S., Tzankov A., Muller A. DUSP4 deficiency caused by promoter hypermethylation drives JNK signaling and tumor cell survival in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. J. Exp. Med. 2015;212:775–792. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrans-Stassen B.H., van de Kant H.J., de Rooij D.G., van Pelt A.M. Differential expression of c-kit in mouse undifferentiated and differentiating type A spermatogonia. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5894–5900. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seandel M., James D., Shmelkov S.V., Falciatori I., Kim J., Chavala S., Scherr D.S., Zhang F., Torres R., Gale N.W. Generation of functional multipotent adult stem cells from GPR125+ germline progenitors. Nature. 2007;449:346–350. doi: 10.1038/nature06129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakawa T., Yaman-Deveci R., Tomizawa S., Kamizato Y., Nakajima K., Sone H., Sato Y., Sharif J., Yamashita A., Takada-Horisawa Y. An epigenetic switch is crucial for spermatogonia to exit the undifferentiated state toward a Kit-positive identity. Development. 2013;140:3565–3576. doi: 10.1242/dev.094045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takubo K., Ohmura M., Azuma M., Nagamatsu G., Yamada W., Arai F., Hirao A., Suda T. Stem cell defects in ATM-deficient undifferentiated spermatogonia through DNA damage-induced cell-cycle arrest. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuda M., Kadokawa Y., Kurahashi H., Marunouchi T. CDH1 is a specific marker for undifferentiated spermatogonia in mouse testes. Biol. Reprod. 2007;76:130–141. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresini M., Lorenzini A., Torres C., Cristofalo V.J. Modulation of replicative senescence of diploid human cells by nuclear ERK signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:4136–4151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K., Chen X., Yang H., Xu Y., He Y., Wang C., Huang H., Liu B., Liu W., Li J. Maternal Sall4 is indispensable for epigenetic maturation of mouse oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;292:1798–1807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.767061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y.L., Tanaka S.S., Kumagai M., Fujimoto Y., Terabayashi T., Matsui Y., Nishinakamura R. Sall4 is essential for mouse primordial germ cell specification by suppressing somatic cell program genes. Stem Cells. 2015;33:289–300. doi: 10.1002/stem.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Corsello T.R., Ma Y. Stem cell gene SALL4 suppresses transcription through recruitment of DNA methyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:1996–2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F.Q., Yang F.P., Li W., Liu M., Wang G.C., Che J.P., Huang J.H., Zheng J.H. Foxl1 inhibits tumor invasion and predicts outcome in human renal cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014;7:110–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh J.R., Zhang X., Nagano M.C. Wnt5a is a cell-extrinsic factor that supports self-renewal of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:2357–2366. doi: 10.1242/jcs.080903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuri S., Fujimura S., Nimura K., Takeda N., Toyooka Y., Fujimura Y., Aburatani H., Ura K., Koseki H., Niwa H. Sall4 is essential for stabilization, but not for pluripotency, of embryonic stem cells by repressing aberrant trophectoderm gene expression. Stem Cells. 2009;27:796–805. doi: 10.1002/stem.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Tam W.L., Tong G.Q., Wu Q., Chan H.Y., Soh B.S., Lou Y., Yang J., Ma Y., Chai L. Sall4 modulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and early embryonic development by the transcriptional regulation of Pou5f1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:1114–1123. doi: 10.1038/ncb1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., He P., Gaedcke J., Ghadimi B.M., Ried T., Yfantis H.G., Lee D.H., Hanna N., Alexander H.R., Hussain S.P. FOXL1, a novel candidate tumor suppressor, inhibits tumor aggressiveness and predicts outcome in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5416–5425. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohni K., Zhang X., Tan S.L., Chan P., Nagano M.C. The efficiency of male fertility restoration is dependent on the recovery kinetics of spermatogonial stem cells after cytotoxic treatment with busulfan in mice. Hum. Reprod. 2012;27:44–53. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.