Abstract

Problem

Adolescent mothers and their children are at high-risk for depression and the associated negative educational, social, health, and economic outcomes.

Background

However, few pregnant adolescent women with depression receive psychiatric services, especially low-income or racial/ethnic minority adolescent women.

Aim

This qualitative study explores perceptions of depression, psychiatric services, and barriers to accessing services in a sample of low-income, pregnant racial/ethnic minority adolescent women. Our goal was to better understand the experiences of depression during pregnancy for these vulnerable adolescent women, and thereby improve their engagement and retention in services for perinatal depression.

Methods

We recruited 20 pregnant adolescent women who screened positive for depression from 2 public health prenatal clinics in the southeastern United States. Participants were low-income and primarily racial/ethnic minority women between 14 and 20 years old. Data were collected through individual in-depth, ethnographically informed interviews.

Findings

Generally, participants lacked experience with psychiatric services and did not recognize their symptoms as depression. However, participants perceived a need for mood improvement and were interested in engaging in services that incorporated their perspective and openly addressed stigma.

Discussion

Participants reported practical and psychological barriers to service engagement, but identified few cultural barriers. Family perceptions of psychiatric services served as both a barrier and support.

Conclusion

Adolescent women are more likely to engage in psychiatric services if those services reduce practical and psychological barriers, promise relief from the symptoms perceived as most meaningful, and address underlying causes of depression. Culture may affect Latina adolescent women’s perceptions of depression and services.

Keywords: pregnant, adolescent women, depression, qualitative, psychiatric services

Introduction

The United States (U.S.) has one of the highest rates of adolescent pregnancy among industrialized nations, with low-income, racial/ethnic minority adolescents being most affected.1 Perinatal depression (PND), major depression occurring during pregnancy through one-year postpartum, is a debilitating illness with significant educational, economic, health, and social costs. PND increases risk of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality, preterm birth, and enduring negative outcomes for mother, child, and family.2–5 Estimated rates of pregnant adolescent women with PND, ranging from 20–44%, are 2 and 4 times the rate of low-income women and middle-class women, respectively.6–8

Few pregnant adolescent women with depression receive psychiatric services.9,10 Low-income, racial/ethnic minority adolescent women experience the greatest disparities11,12 increasing their risk of future major depression, poverty, and abuse.8,9,13–15 Barriers to psychiatric services and a lack of culturally acceptable services intensify this risk.16,17 However, low-income, minority adolescent women can be engaged if services address their unique needs.12 Reducing disparities in service use and prevalence of PND among low-income adolescent women requires a better understanding of how these adolescent women perceive depression, psychiatric services, and barriers to accessing services.

U.S. Adolescent Mothers’ Perceptions of Pregnancy, Perinatal Depression and Psychiatric Services

For many adolescent women in the U.S., pregnancy marks the entrance into adulthood,18 but also requires interpersonal, social and behavioral changes.18–22 Perceived costs of these lifestyle changes include school dropout, foregoing higher education, entering the workforce, social isolation, ending romantic relationships, single parenthood, losing peer support, being judged negatively, and family stress.18, 20–22 Rewards may include improved relationships with mothers and school officials; love for the child; and developing friendships with other pregnant/parenting adolescent women.18, 21,22 However, costs and benefits differ across socioeconomic and racial/ethnic status.

The available research on adolescent mothers’ perceptions of PND is scant. Studies have identified interpersonal stressors as a primary factor. Adolescent mothers report extreme stress from conflict with parents and/or romantic partners experienced in combination with financial hardship, societal expectations, cultural messages, and/or pubertal changes.23,24 Adolescent women have also reported perceiving extreme stigma around psychiatric illness, particularly depression.

Existing literature on pregnant adolescent women’s perceptions of psychiatric services reports they are shaped by their knowledge, experience, and satisfaction with services. Although few adolescent mothers receive psychiatric services, those that have often report dissatisfaction.25 Limited evidence suggests pregnant adolescent women’s preference for group-based services.26–29 Unfortunately, the chaotic lives of adolescent mothers30 often interfere with attending group interventions. Additionally, trauma history, estimated to be present in at least 84% of low-income adolescent mothers, is counter-indicative of group services.6,31,32

Although not specific to pregnancy, research has suggested that compared with Caucasian adolescent women, racial/ethnic minority adolescent women experience higher rates of depression,33 lower service utilization,34 and higher unmet psychiatric needs.35 Minority adolescent women in the U.S. experiencing depression are more likely to report use of informal, community, faith-based, school-based, or medical resources (e.g., doctors, emergency department) than psychiatric professionals or agencies.36–39 Previous research has found adolescent women’s help-seeking to be influenced by culture, stigma, attribution to non-biological causes, increased somatic symptoms, and “health paranoia”.37,40–42 Based one existing literature minority adolescent women in the U.S. face multiple barriers to psychiatric care use. These include stigma, discrimination, lack of information and transportation, financial, language, family, cultural, and immigration related barriers.34,37–41,43–45 Accordingly, those who receive psychiatric services often terminate prematurely.46

Research examining minority adolescent women’s experiences of PND reported symptoms (anger, irritability, sadness, anxiety, and shame/guilt) were primarily experienced in reference to external circumstances. Noted circumstances include feeling trapped, powerless, or wronged; difficulty acquiring resources; and rejection by family/others.47, PND improvement was associated with pregnancy validation, obtaining resources, successful self-advocacy, boundary setting, and clarification of life transitions.48 Pregnancy in U.S. adolescent mothers was associated with an increased sense of purpose and consciousness of safety.48 Having emotional support from family, particularly the baby’s father, reduced PND risk. However, few adolescent fathers in the U.S. provided support.47,48

Study Objectives

This qualitative study addresses knowledge gaps regarding the experience of U.S. low-income, minority, depressed pregnant adolescent women’s perceptions of pregnancy, depression, and help-seeking. Our study is guided by a critical feminist methodology. We sought to understand the experiences and perceptions of U.S. pregnant depressed adolescent mothers in their own words and from their own worldviews rather than from those of practitioners, administrators, or parents. Our research was guided by the following questions: 1) What are pregnant adolescent women’s perceptions of their current mood? and 2) What are pregnant adolescent women’s perceptions of psychiatric services? As we progressed, a third question emerged and was added to the study: 3) What services beyond psychiatric care are needed by this population?

Participants, Ethics, and Methods

Study Designand and Population

In-depth interviews were conducted by the principal investigator, SB, and a female master of social work (MSW) level social worker, AS. We used convenience sample of 20 pregnant, low-income adolescent women recruited from two public prenatal clinics in the southeastern U.S. Both interviewers had at least MSW level training with a specialization in psychiatric social work and training in ethnographic and qualitative interviewing. Both interviewers had at least 2 years post MSW experience working with low-income mothers in a clinical setting. Participants met the following criteria: income ≤185% federal poverty line; ≤ 32 weeks gestation; 14–20 years old; receiving prenatal care; and score ≥ 10 on the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)49 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the PIs home institution. Interview data was collected prior to intervention services.

Recruitment Procedures and Data Collection

Participants were recruited between December 2009 and September 2010 by project staff, self-referral, and provider referral. Of the 31 adolescent women recruited, 3 declined to participate, 4 did not meet study inclusion criteria, and 2 dropped out prior to the interview. After obtaining informed consent, a research associate administered the EPDS49 to assess probability of PND diagnosis. Adolescent women who met study criteria were invited to complete the in-depth interview within one week of initial screening. Interviews were scheduled with the research associate, AS, who conducted the screening or the PI, SB. Participants were told that the research was being conducted in order to learn more about the experiences of adolescent mothers with depression to inform future programs and services for similar families. Interviews lasted 45–90 minutes and were conducted in private rooms at the prenatal clinics. Interviews were digitally recorded with participant consent. The ethnographically informed in-depth interview was adapted from the PI’s previous research with low-income depressed pregnant women based on current literature, clinical experience of the research team, and beta testing of the interview guide. Open-ended questions asked of all participants addressed perceptions of current problems, mood, psychiatric services history, hopes for services, and barriers to accessing services. Standardized prompts for each were included in the interview guide for each topic (interview guide available upon request). Interviewers were encouraged to use the standardized prompts when necessary but were also allowed to probe as needed based on each participant’s response. The semi-structured interview guide was beta tested and revised prior to implementation. Interview topics informed data analysis. Topics were used to develop predetermined codes used in data analysis.

After completing the qualitative interview, participants were asked to complete a baseline questionnaire. This questionnaire included demographic information and the following instruments used to collect additional data on psychiatric symptoms, social adjustment, and social support. Instruments used to describe our sample include the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD),50 the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD),51 M = 21.83, SD = 6.58, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),52 the Social Adjustment and Support Social and Leisure Domain (SASSLD),53 and the Medical Outcomes Social Support Survey (MOS).54

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim from recordings. Transcript checking was performed prior to analysis. Data were managed using NVivo 7.55 We employed triangulation of data and sources using interviewer field notes collected prior to, during, and after the interviews. Multiple coders were used to ensure study reliability and validity. Analysis followed a descriptive qualitative approach using preexisting codes drawn from prior research and emergent codes. We used an inductive iterative process that involved breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualizing, and categorizing the data.56 The PI, SB, and a research associate, TW, analyzed 25% of the transcripts to develop a codebook through consensus. The codebook was reviewed and modified based on feedback from experts in adolescent psychiatry and PND before final coding.

Two graduate student coders, TW and AB, were trained to greater than 90% reliability with the master coder, SB. The research team conducted evaluations of intercoder reliability at three time points to ensure the codebook was appropriately applied. Intercoder reliability remained > 90% throughout coding. As new codes emerged, these were noted, discussed, and incorporated into the codebook (coding tree available upon request). Reports were produced for each code. The research team analyzed reports to derive patterns and themes, leading to the main findings. Data saturation was achieved prior to coding the final interview. Member checking was not employed. To enhance study validity, expert consultants informed the interpretation of findings. Additionally, analysts reviewed transcripts to search for evidence contradictory to initial findings.57

Results

Respondents were primarily minority adolescent women: 46.5% African American and 46.5% Latina. Mean age was 17.28 (SD = 1.49), average gestational age was 16.85 weeks (SD = 4.63), and 75% of pregnancies were unplanned. Of the 67% not attending school, only one participant had graduated high school. Average household size was 4.2 persons (SD = 2.2), income ranged from less than $10,000 to $40,000–$50,000 annually, and 72.8% of participants reported annual household income less than $20,000. Most participants were unemployed (60%) and 40% had never held a paying job. Among this sample, 50% were cohabitating/married, and 50% were primiparous. All participants reported significant depressive symptoms on self-report (EPDS; M = 14.82, SD = 2.79, cut point = 10; CESD;50 M = 26.36, SD = 10.52, cut point = 16) and observational measures (HRSD;51 M = 21.83, SD = 6.58, cut point = 8). Participants reported high anxiety symptoms (BAI;52 M = 20.77, SD = 12.07, cut point = 7), poor social adjustment (SASSLD;53 M = 2.98, SD = 0.93, cut point = 2.2) and low social support (MOS;54 M = 3.14, SD = 0.73).

Prior to this study, only 30% of participants had a diagnosis of depression (see Table 1). Another 30% were informally diagnosed by self, family, or friends. Notably, most participants had high levels of anxiety, but only one discussed a diagnosis of anxiety. Moreover, 40% of participants had no formal or informal depression diagnosis.

Table 1.

Formal and Informal Diagnosis of Depression and Other Psychiatric Illnesses (N=20)

| Diagnosis | Depression | Bipolar Disorder | Mood Disorder | Panic Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Formal | 30 (6) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Informal | ||||

| Self | 40 (8) | – | – | – |

| Family | 10 (2) | – | – | – |

| Friend | 5 (1) | – | – | – |

| Both Formal and Informal | 20 (4) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) |

| No Diagnosis | 40 (8) | 95 (19) | 95 (19) | 95 (19) |

Perceptions of Current Mood and Depressive Symptoms

The study’s first aim was to understand pregnant adolescent women’s perceptions of mood and the context of their depressive symptoms. In describing perceptions of depressive symptoms, 40% self-diagnosed depression. However, some quickly dismissed their self-diagnosis: “I probably am depressed, but then again, I don’t think so. I wouldn’t want to admit it to myself.” Despite unfamiliarity with criteria diagnosing depression, other participants found it difficult to deny. One stated, “I don’t really know anything like that about depression, but I feel it.”

Although many participants had no prior diagnosis, their perceptions of depression and reported current mood were remarkably similar. Table 2 compares diagnostic criteria with participant-identified responses to queries about current mood and their perceptions of depression. Excluding “psychomotor agitation or retardation,” participants reported experiencing all major depression symptoms. However, some symptoms were experienced differently than described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR).58 For example, rather than reporting “diminished concentration or indecisiveness,” participants reported feeling “overwhelmed” or “stressed.”

Table 2.

Comparison of DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria, Participants’ Experiences of Current Mood, and Participants’ Perceptions of Depression

| DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depression | Perceptions of depression | Experience of current mood |

|---|---|---|

| Depressed mood | Persistent sad, anxious, or empty mood crying all the time, being sad all the time, nervous, down, feeling bad about everything, miserable, hurt |

Persistent sad, anxious, or empty mood crying, sad, worried |

| Irritability or anger angry, moody, mood swings, mean, hateful, aggravated, upset, catch an attitude, took my anger out on other people, out of control, crazy |

Irritability or anger irritable, mad, crazy |

|

| Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities | Anhedonia not really trying to have a good time, don’t want to go anywhere, can’t enjoy children, don’t want to do anything, bored, don’t enjoy anything |

Anhedonia just want to stay in the house all the time, really boring, not wanting to have fun or enjoy myself |

| Isolation, self-isolation wanting to be alone, felt alone, didn’t want to talk to people, don’t want to be bothered, isolated, lonely |

Self-isolation didn’t want to go around/talk to anybody, didn’t want to be bothered |

|

| Significant weight loss or gain or decrease or increase in appetite | Appetite increase Hungry |

Appetite increase and/or decrease poor appetite, make myself eat, eat just one time, makes me eat, get hungry |

| Insomnia or hypersomnia | Hypersomnia just want to lay in bed |

Insomnia and/or hypersomnia wake up in the night, don’t sleep well, sleep all the time, couldn’t get out of bed |

| Psychomotor agitation or retardation. | – | – |

| Somatic complaints Headaches |

Somatic complaints headaches |

|

| Fatigue or loss of energy | Decreased energy, fatigue slowed down, tired all the time, weighing me down |

Decreased energy, fatigue slowed down, lack of energy, just wanted to lie in bed |

| Feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt | Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, helplessness nobody cares about me, blaming myself, I think something is wrong with me, down on myself |

Feelings of guilt blaming myself guilt |

| Diminished concentration or indecisiveness | Overwhelmed stress, hard, frustrated |

Overwhelmed hard, a lot, don’t know what to do |

| Recurrent thoughts of death | Thoughts of death or suicide I wanted to die, If I was depressed I would want to kill myself |

Thoughts of death or suicide; suicide attempts I wanted to hang myself, I just decided to kill myself, I was in the hospital for taking an overdose, and I wanted to die |

| Feelings of hopelessness feel like giving up on everything, didn’t think I was going to make it |

Feelings of hopelessness feel like giving up |

|

| Self-injurious behaviors I tried to hurt myself |

Note: Italics denote language used by participants to describe perceptions and experiences

Participants recognized suicidal ideation as a symptom of depression. Several reported suicidal ideation, attempts, and other self-injurious behaviors and identified feelings of hopeless as an experience of depression. Participants clearly identified depression as having components of irritability or anger, including feeling or acting “crazy.” Participants widely reported perceptions of depression in their descriptions of current mood. Notably, participants also identified idiopathic somatic complaints as part of depression, as exemplified by one participant:

Participant: … wondering what was wrong with me, because I had headaches and everything.

Interviewer: So, you had a lot of headaches and weren’t feeling well. And the doctors did a lot of tests and then they told you, actually it’s…

Participant: It’s depression.

Primary Perceived Problem

Most participants identified their primary problem as related to the context in which the symptoms arose rather than the symptoms themselves, as exemplified in the following quote:

I’m trying to find some place for me and my baby to stay and that’s kind of hard. I’ve been trying to find a job and, being pregnant, a lot of people don’t hire you because they don’t think you can do a lot of stuff. It’s just hard. I worry so much. My mom’s been sick. I’m trying to get my son in daycare. It’s just a lot. I just don’t know what to do anymore and I’m depressed all the time.

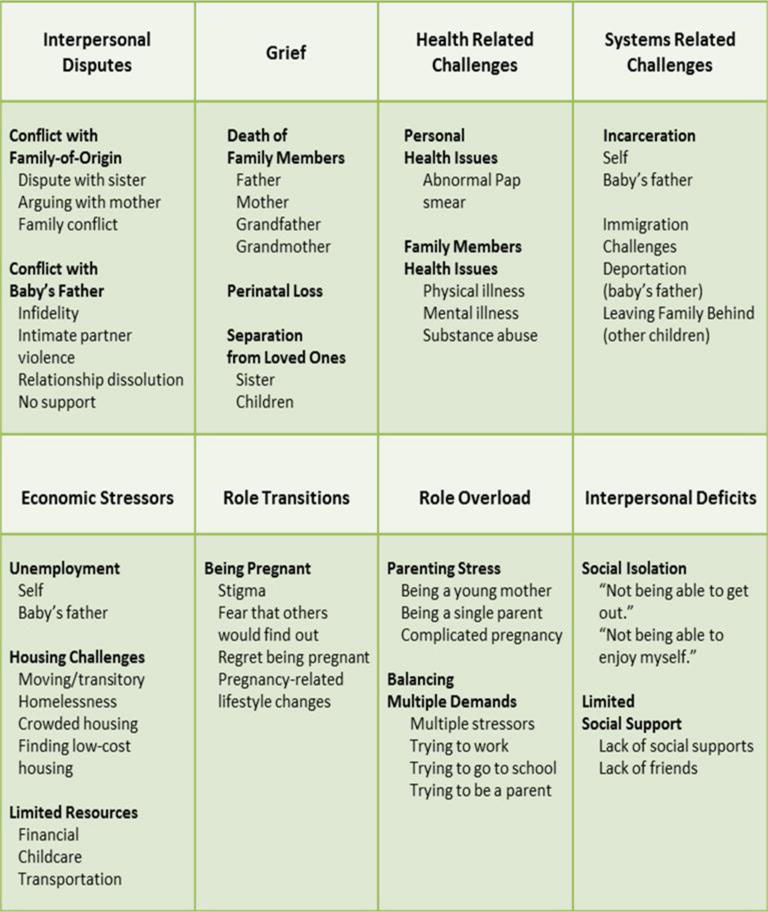

Adolescent women’s perceptions of their primary problem reliably fell into 1 of 8 categories (see Figure 1): interpersonal disputes, grief, health-related challenges, systems-related challenges, economic stressors, role transitions, role overload, and social isolation. No participant identified depression as the primary problem.

Figure 1.

Eight categories of perception of the problem

Within interpersonal disputes, family conflict was most often mother-daughter relationship stress. Most conflict related to participants’ perceptions that their mother had inadequate parenting ability. A participant expressed a common sentiment:

I don’t want to talk down on my Momma but I think she has some kind of illness. She can’t do for herself so how could she do for her kids? … she just doesn’t know how to be a good mother. She tries but she just doesn’t have the ability.

Another subtheme that emerged under interpersonal conflict was conflict with the baby’s father, ranging from lack of support to abuse.

Complicated grief was also a common theme. Nearly 25% of participants described the death of a parent or grandparent as related to their current problems, although associated symptoms did not meet DSM-IV-TR67 definition for bereavement. One participant tearfully recalled her grandfather died during her psychiatric hospitalization. She described missing his funeral as an incredibly difficult experience. Similarly, separation from a loved one was identified as a problem. The following comment was typical of many: “My mom was sick. When my mom died, they took my little sister, her dad did…. When I was with my sister, I was happy. I might be depressed now, but I wasn’t then.”

Personal health was a subtheme that emerged under health-related challenges. Most participants distinguished personal health issues from pregnancy. More often, participants expressed concern about the health of family, including psychiatric and substance disorders. These illnesses were related to many other problems participants identified:

I moved in with [baby’s father] and his family because my family was going through some things because my brother had become schizophrenic. My mom didn’t want me to be in the house with him because he gets violent when he has his moments.

Systems-related challenges focused primarily on criminal/juvenile justice and immigration. Criminal/juvenile justice problems involved incarceration of self and family, including the baby’s father. Participants most frequently entered the juvenile justice system because of emotional or family problems rather than criminal activity. For instance, one participant became entangled in the court system after her mother filed a missing person report despite knowing her daughter was staying with friends while the family was homeless. Another participant was incarcerated following a suicide attempt. Family incarcerations represented compounding stress for participants. As one participant explained, “My dad didn’t want my baby’s father to be in jail for what they accused him of. So we had to find a lawyer and all of that…. everything changed for a while.” Immigration difficulties were also reported. Difficulties included fear of deportation (self or family) or threatened deportation of family (including baby’s father) during the participant’s pregnancy.

Participants identified three economic stressors associated with depressive symptoms: unemployment; housing challenges; and limited resources (financial, childcare, and transportation). Few of these existed in isolation, and many were compounding stressors. One participant described the cumulative nature of economic stressors:

The problems just recently happened. It’s been about two months. That’s when I lost my place and me and my baby were going from place to place. Basically, it was a money thing because I wasn’t working and then I was trying to find a job but my mom was in the hospital. I lost my car and then I lost my place to stay. It’s been a lot.

Similar stories of multiple, compounding economic stressors taxing already fragile social supports were common.

Some participants identified the role transition of being pregnant, rather than depressed, as the primary problem related to changes in mood. Several participants reported fear of seeing family and friends who did not know they were pregnant. Others discussed regrets regarding their pregnancy. One participant noted:

Sometimes I even regret just being pregnant. I regret coming [to the United States]. I came all this way just to have a baby. I left my son in Mexico just to come over here to have a baby and sometimes I regret that.

Others felt they had little choice in being pregnant and worried about how they would care for the child, “Well I really don’t want to be pregnant but I don’t have a choice. I just got to deal with it. And it is going to be hard with two kids.” For many participants, pregnancy concerns were compounded by role overload. Participants acknowledged the challenges of balancing multiple demands such as trying to work or find employment and attend school or being a parent while working or attending school.

History, Perceptions of and Hopes for Psychiatric Services

Table 3 lists participant-reported experiences with past psychiatric services. Just as participants did not distinguish between depression and the interpersonal and contextual problems associated with the onset of depressive symptoms, they did not distinguish between psychiatric and other types of social services.

Table 3.

Service History and Perceptions of Past Services

| Type of Service | % (n) | Negative Perceptions | Positive Perceptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric medications | 30 (6) | Didn’t work/not helpful | Increased energy |

| Ability | Side effects: | ||

| Ambien | stopped eating/lost | Less overwhelmed | |

| Lexipro | weight | ||

| Paxil | overeating | ||

| Prozac | withdrawal | ||

| Xanax | passing out | ||

| Zoloft | Overdosed | ||

| Psychiatrist | 5 (1) | – | – |

| Counseling/therapy | 25 (5) | Asking questions that participants didn’t want to answer | Having someone to talk to |

| Asking questions without offering suggestions or advice | Learning relaxation techniques | ||

| Repeated hospitalization | |||

| Pastoral counseling | 5 (1) | Moral judgment interfered with counseling | Feeling understood |

| No advice given beyond encouragement to pray | |||

| Case management | 5 (1) | – | Flexible scheduling |

| Anger management | 5 (1) | – | – |

| Medical services | 15 (3) | Blaming symptoms on pregnancy hormones | – |

| emergency room | Lack of empathy | ||

| hospitalization | |||

| physician | Missing important personal events while hospitalized | ||

| Rehabilitation/detention center | 10 (2) | Being with juveniles who had committed violent crimes | – |

| Group home | 10 (2) | – | – |

Participants reported service histories that included psychiatric medications. Although participants noted positive experiences with psychiatric medications (e.g., increased energy, feeling less-overwhelmed), some participants found medication unhelpful or experienced negative side effects (e.g., changes in appetite/weight, withdrawal, passing out). One participant reported attempting suicide by overdosing on psychiatric medications.

Nearly 25% of participants reported seeing a therapist for individual treatment. Most participants found this helpful because it provided someone to talk to and they learned important skills (e.g., relaxation techniques). Typical participant comments included, “Being able to talk to my therapist again, at that point in time, helped a lot,” and “My therapist taught me ways to just be calm. When you get angry just meditate or listen to calm music… or just breathe.” However, some participants did not want to answer therapist’s questions or felt that the therapist was asking questions but not providing helpful advice. One participant stated therapy was a negative experience because she was hospitalized, “I thought a therapist just talks to you. I didn’t think they really just keep putting you back in the hospital.”

One participant and her partner received pastoral couples therapy. She appreciated that her pastor encouraged her to pray instead of giving advice. Although she reported generally feeling understood by the pastor, the pastor’s moral judgment ultimately interfered, “I can’t even talk to my pastor now. She basically said that I didn’t want to get married and so she was hurt.”

Several participants received medical-based services (i.e., emergency room, hospitalization, primary care) and reported only negative experiences. Physicians were perceived as lacking empathy and minimizing participants’ experiences by blaming depressive symptoms on pregnancy hormones. On participant explained:

The doctors, they probably don’t really know how I feel about being depressed, because they’ve probably never really been depressed. And, it was kind of hard trying to talk to them about being depressed and being pregnant at the same time because they think it’s just your hormones with you being pregnant. But it’s not, because I’ve been depressed before I got pregnant this time, so I know.

Participants also reported past services that included psychiatry, case management, anger management, detention center stays, and group-home residency. Although participants did not generally expand on these services, one participant described a detention center stay as a highly negative experience:

I really thought I was going to die in detention. I cried every second on the second because I know I’m not bad. I was in there with people who stabbed people! I was like,

“Oh my god! Why am I in here?”

Participants mentioned flexible scheduling as important in receiving services. One woman noted her case manager agreed to meet with her on Saturday. She interpreted the flexible scheduling as a sign of sincerity, “If they are willing to come out on a Saturday to help you, you know they are trying to help you!”

Perceptions of Barriers to and Promoters of Help-Seeking

Participants identified a number of practical, psychological, family, and cultural factors as barriers or promoters of seeking psychiatric services for depression (see Table 4). Practical barriers include transportation, housing instability, competing demands, and history of ineffective services. Some participants described personal decisions to abstain from medication while pregnant as a practical barrier. Moreover, several participants reported they were never offered the option of services for their depressive symptoms. As noted, flexible scheduling is an important practical promoter of service use. Given the complicated lives and needs of participants, psychiatric services with scheduling flexibility are crucial to ensuring they receive needed psychiatric care.

Table 4.

Barriers to and Promoters of Seeking Services for Antenatal Depression

| Type of Barrier/Promoter | Barriers | Promoters |

|---|---|---|

| Practical | Transportation | |

| Transitory/moving often | ||

| Services weren’t offered | ||

| Competing demands | Flexible scheduling | |

| Services (medication) did not work. | ||

| Cannot/will not take medication | ||

| Psychological | Stigma | |

| Fear | ||

| Denial of depression | ||

| Denial of need for services | ||

| Did not want services | ||

| Did not want to talk about problems | ||

| Family | Parent disapproved of services | Family history of services |

| Parent did not think services were working | Parental proactive involvement | |

| Parent forced patient to receive services | ||

| Parent sought hospitalization | ||

| Parent wanted participant to stop services | ||

| Cultural | Marianismo | Marianismo |

Although participants did not mention any psychological promoters of help-seeking, they identified many psychological barriers. Stigma and fear emerged as important, common barriers. Two participant comments were typical of many: “Judgment. Just don’t want anyone to judge me or look down on me,” and “I don’t know. Just…I’m scared.” For many participants, denial was a barrier. These participants did not perceive themselves as depressed or did not think their symptoms required services. For many, acknowledging the need for services was a challenging process. Others were able to identify symptoms and service value, but did not want to engage in services or talk about problems with providers, “I guess I just didn’t want to say all the things on my mind.”

Family played a prominent role in help-seeking. For some participants, a positive family history of psychiatric services promoted help-seeking. One participant explained, “My aunt is on medicine for depression, she told me if I’m so depressed, why not try to get on some depression medicine? It might relieve some of my stress, and I would not be worried about things that much.” Moreover, several participants identified parental support and assistance as an important help-seeking promoter. One participant stated her father helped by scheduling her therapy appointments.

Although parents served as supports for some, most participants perceived parents as barriers to receiving psychiatric services. Parents’ disapproval of and interference in services was a common theme. Participants reported parents disapproved of psychiatric services, often stating the services were not working and the participant should stop services. The following two comments were typical, “My father wanted me to stop going but I wasn’t ready to stop. I guess, in a way, me not being ready to stop therapy and him making me stop anyway made things hard to cope with.” and “I wanted to go and so my mom sent me to the mental clinic and they set me up with this woman …. I talked to her for a little while, but then … my mom said it wasn’t working, but I thought it was. But she said it wasn’t, so I stopped going.” Other participants identified parents’ over-involvement in services as a barrier. One participant perceived her mother forced her to see a therapist, whereas another perceived her mother pressing for her hospitalization, “When we got there for therapy, me and my mom would start arguing. Then my mom would say stuff like, ‘Can’t you put her in the hospital?’” To be perceived as supportive, it was important that family not pressure participants, but instead provide information and assistance to accessing psychiatric services.

For Latina participants, cultural factors were perceived as both barriers and promoters to help-seeking. Marianismo refers to a Latino gender role script whereby Latinas are expected to model behavior after the Virgin Mary. They are to be spiritually and morally untainted, maintain the family, sacrifice for the sake of the family, and be submissive, stoic, dependent, and faithful to their male partners.68 Marianismo served as a barrier to help-seeking when participants faced competing demands and put family needs above their own. However, marianismo promoted help-seeking among participants’ whose perception of pregnancy was congruent with self-care for their babies’ well-being:

So [when you’re pregnant] you’ve got to take care of yourself… And when you’re not pregnant, well, you don’t really care about that.

Additional Service Needs

Low-income pregnant adolescent women lead complicated lives, and psychiatric services merely scratch the surface of their needs. Additional needs emerged consistently, including services to address past and current trauma (including intimate partner violence), criminal justice, immigration, gang involvement, housing, employment, education, childcare, tangible support, and parenting.

During the initial interview, 33% of participants reported trauma history. All but one participant disclosed trauma history during the intervention component of the larger study. Many participants reported abuse by the baby’s father. A typical comment follows,

My husband, when he gets angry or I don’t want to do something, he likes to push me or push me down. He drug me down the stairs one night…. he knew that we were married and he thought he could treat me any way he wanted. He told me I was his property and he owned me. I was hurt because I thought, I’m your wife -you don’t own anybody. He’ll talk about me to his friends in front of my face. Tell them how dumb I am. It’s not just physical things. There’s also emotional abuse.

Several participants reported other traumatic events including the death of a caregiver or boyfriend. Other participants disclosed personally experiencing perinatal loss or being affected by a friend or family members’ loss, “I have an appointment to get an ultrasound and blood work. My mom had heart disease, congestive heart failure, all that kind of stuff and they’re just worried that something might happen. I’ve already had two miscarriages.”

Participants also reported trauma from personal or family gang involvement, “I used to be a gang member…that’s what messed me up.” Gang-related services could be important to consider. Criminal justice/legal services could be beneficial for participants who identified incarceration or legal entanglements of themselves, the baby’s father, or family as significant sources of stress.

Immigration-related issues also emerged. Many Latina participants reported fears related to lack of documentation and deportation from the U.S. for themselves and family. Immigration issues posed substantial barriers to employment for many participants, “I’ve worked in the past in Mexico, but not here. Because I’m not legal to work here.” One participant discussed the daily difficulties she experienced after leaving one of her children in her country-of-origin. A number of participants discussed their baby’s father’s immigration-related challenges, including deportation and reluctance to report domestic violence because of the partner’s undocumented status. Participants also reported multiple economic stressors, indicating their basic needs were often unmet. Services to address housing, employment, education, childcare, and tangible support are needed.

Discussion

By examining adolescent women’s perceptions of depression and psychiatric services in the context of pregnancy, this study fills a critical gap in evidence related to the treatment of PND in U.S. low-income, minority adolescent women. Although all participants had EPDS scores indicating probable depression, few had a diagnosis despite known risk of PND in adolescent women. Existing research supports the reluctance among African American adolescent women to label themselves as depressed, even if they recognize depression.34 However, this reluctance fails to account for only 40% of participants reporting informal diagnosis and why only 30% had a formal diagnosis. Screening and diagnostic efforts still fall painfully short of identifying PND in U.S. adolescent women despite evidence of depression as a significant risk factor mothers and children. Increasing screening efforts is critical because U.S. low-income, minority pregnant adolescent women and others in their natural support system are unlikely to recognize PND.

To improve screening and diagnosis of PND among U.S. adolescent women, it is crucial to understand the language these women use to describe symptoms. Although participants reported symptoms characteristic of major depression, some did not correspond with DSM-IV-TR58 criteria language. Participants described “diminished concentration or indecisiveness” as “overwhelmed,” “stressed,” “frustrated,” “hard,” and “don’t know what to do.” Moreover, participants often described anhedonia as “bored”. It should be noted that the DSM 5 released in 2013 guides current diagnostic standards. However, study design coding and analysis of the study data were conducted prior to the release of the updated version of the DSM 5. Changes to the diagnosis of major depression between DSM-IV-TR and DSM 5 were reviewed and determined not significant enough to impact study findings.

Rather than viewing symptoms as psychiatric, adolescent women were more likely to perceive depressive symptoms as related to interpersonal issues. This perception might be a strength because studies have identified the ability to separate depression from the core-self by identifying outside influences as a potential protective factor for low-income mothers.60 Interpersonal issues accounted for 5 of 8 categories of perceived problems. The remaining three were environmental stressors related to surviving poverty. Pregnant U.S. adolescent women simply may not identify with being depressed as strongly as they identify with having interpersonal problems and poverty-related stress. Therefore, it is critical to make services available that address adolescent women’s perceptions of the problem. These services should include components focused on improving interpersonal coping and reducing the stress of surviving poverty.

Efforts to engage and retain U.S. adolescent mothers in psychiatric services should consider their’ perceptions of current problems and past experiences, including positive and negative experiences of past services. These findings are consistent with implications from recent research on treating PND in adult women. This research stresses the importance of assessing the patient’s beliefs about causes of and services for depression, as well as understanding previous service experiences.61 U.S. adolescent mothers’ are likely reacting to stressors that emerge on a daily basis. These mothers might benefit from services that place priority on environmental and functional stability to ensure the safety of mother and baby. PND impacts adolescent mothers’ ability to manage these stressors making services critical.

Trauma history is prevalent among U.S. pregnant adolescent women and significantly increases risk of PND.6,31 Participants described complex trauma histories including child maltreatment, abandonment, assault, interpersonal violence, and traumatic loss. Clinicians should not underestimate the relevance and potential interconnection of adolescent women’s trauma history with their pregnancies, depression, and service experiences. Adolescent mothers’ perceptions of traumatic events and coping mechanisms are equally important to understanding the extent of their victimization experiences. This understanding is necessary in assessing U.S. adolescent mothers’ ultimate strengths and service needs, but may not be clear in the context of major depression.

Engagement and retention efforts can be enhanced by understanding the factors that inhibit or propel depressed U.S. adolescent mothers to access psychiatric services. Our findings suggest the support or hindrance of families is key to use of psychiatric services. Findings are consistent with results of previous research.62 Engaging the adolescent woman’s family in psychoeducation services could increase engagement and retention.

Given the chaotic lives of low-income, minority pregnant adolescent women in the U.S., it is not surprising that many reported scheduling flexibility was a key factor in their use of services. Additionally, several participants reported PND services were not offered. Clearly, these practical, psychological, and cultural barriers to services engagement and participation must be resolved.

Participants’ focus on interpersonal conflict is not surprising considering the high levels of trauma and chronic stress inherent in their everyday lives. Any history of interpersonal trauma increases the risk for impaired attachment. This can profoundly affect the ability to form and maintain healthy interpersonal relationships, including relationships with service providers. Care should be taken to understand and engage the mother in a way that is genuine, nonjudgmental, and trauma-informed. Findings that service experiences serve as either a barrier or promoter of help-seeking underscores the need for trauma-informed care given the high prevalence in U.S. adolescent mothers.

We also identified the need for complementary services to fully address the needs of adolescent women with PND in the U.S. Providers working with these high-risk mothers should facilitate additional services to address trauma, intimate partner violence, criminal justice involvement, immigration, gang activity, housing, employment, education, childcare, and tangible support. Treating depression outside of the context of these needs is unlikely to improve the well-being of U.S. pregnant adolescent women.

Conclusion

Because this study used a small sample and qualitative methodology, findings cannot be generalized to the population of low-income, minority pregnant adolescent women in the U.S. or internationally. Future research should focus on exploring the generalizability of these exploratory finding in larger samples of U.S. adolescent mothers and adolescent mothers in other countries. Despite these limitations, this work contributes to the limited knowledge on this high-risk group of mothers. In particular, understanding how pregnant adolescent women perceive their depressive symptoms within the broader lived context, particularly regarding interpersonal relationships, is useful in developing appropriate services. Adolescent women seem to express feelings about pregnancy and depression differently than adults, and this difference likely affects how they seek and receive services. Additionally, participants’ descriptions of barriers to service utilization provide a deeper understanding of external forces that might be unique to adolescent women’s experiences in help-seeking. As such, results from this study can inform future research on psychiatric service provision, as well as engagement and retention efforts targeting low-income, racial/ethnic minority pregnant adolescent women experiencing depression.

Statement of Significance.

Problem

Pregnant adolescent women with depression have low levels of engagement and retention in psychiatric services.

What is Already Known

Adolescent mothers and their children are a high-risk group for depression and the associated negative educational, social, health, and economic outcomes. Few pregnant adolescent women with depression receive psychiatric services, especially low-income or racial/ethnic minority adolescent women.

What this Paper Adds

Adolescent mothers do not often recognize the symptoms of depression and have limited experiences with psychiatric services. In order for adolescent women to engage in services practical and psychological barriers as well as the underlying causes of depression should be addressed.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Fast facts: Teen pregnancy in the United States. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/FastFacts TeenPregnancyinUS.pdf.

- 2.Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Rief M. Prenatal depression effects on the fetus and newborn: A review. Infant Behav Dev. 2006;29:445–55. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenberg R, Culhane J, Iams J, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis G, editor. Saving mothers’lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer—2003–2005. London, UK: CEMACH; 2007. Retrieved from http://www.publichealth.hscni.net/publications/saving-mothers-lives-2003-2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmorstein N, Malone S, Iacono W. Psychiatric disorders among offspring of depressed mothers: Associations with paternal psychopathology. Am J Psychiat. 2006;161:1588–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meltzer-Brody S, Bledsoe-Mansori SE, Pollard NP, Killian C, Hamer R, Jackson C, Wessel J, Thorp J. A prospective study of perinatal depression and trauma history in minority adolescents. Am J Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013;211:e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leahy-Warren P, McCarthy G. Postnatal depression: Prevalence, mothers’ perspectives, and treatments. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szigethy EM, Ruiz P. Depression among pregnant adolescents: An integrated treatment approach. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:22–27. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura MA. Births: Preliminary data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Report. 2007;56(7):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Upadhya KK, Ellen JM. Social disadvantage as a risk for first pregnancy among adolescent females in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49:538–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newacheck PW, Hung YY, Park MJ, Brindis CD, Irwin CE. Disparities in adolescent health and health care: Does socioeconomic status matter? Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1238–52. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U. S. Public Health Service. Report of the Surgeon General’s conference on children’s mental health: A national action agenda (Pub. No. 017-024-01659-4) Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Larsen KE, Cox KC. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:585–602. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zisook S, Lesser I, Stewart JW, Wisniewski SR, Balasubramani GK, Fava M, et al. Effect of age of onset on the course of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1539–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond R, Factor R. Treatment-resistant patients or treatment resistant systems? Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:197. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunt C, Andrews G. Drop-out rate as a performance indicator in psychotherapy. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1992;85:275–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spear HJ, Lock S. Qualitative research on adolescent pregnancy: A descriptive review and analysis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2003;18(6):397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(03)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clemmens DA. Adolescent mothers’ depression after the birth of their babies: Weathering the storm. Adolescence. 2002;37(147):551–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrman JW. Adolescent perceptions of teen birth. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:42–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rentschler DD. Pregnant adolescents’ perspectives of pregnancy. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2003;28(6):377–383. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200311000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosengard C, Pollock L, Weitzen S, Meers A, Phipps MG. Concepts of the advantages and disadvantages of teenage childbearing among pregnant adolescents: A qualitative analysis. Pediatrics. 2006;118:503–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3058. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller L, Gur M, Shanok A, Weissman M. Interpersonal psychotherapy with pregnant adolescents: Two pilot studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(7):733–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wisdom JP, Rees AM, Riley KJ, Weis TR. Adolescents’ perceptions of the gendered context of depression: “Tough” boys and objectified girls. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2007;29(2):144–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulder C. Service utilization patterns among adolescent mothers residing in three-generational households. Journal of Social Service Research. 2010;36:414–28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koniak-Griffin D, Anderson NLR, Brecht M, Verzemnieks I, Lesser J, Kim S. Public health nursing care for adolescent mothers: Impact on infant health and selected maternal outcomes at 1 year postbirth. J Adolesc Health. 2012;30:44–54. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaffer MA, Goodhue A, Stennes K, Lanigan C. Evaluation of a public health nurse visiting program for pregnant and parenting teens. Public Health Nurs. 2012;29:218–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2011.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toews ML, Azedjian A, Jorgensen D. “I haven’t done nothin’ crazy lately:” Conflict resolution strategies in adolescent mothers’ dating relationships. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2011;33:180–6. 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yardley E. Teenage mothers’ experiences of formal support services. J Soc Policy. 2009;38:241–57. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinto-Foltz MD, Logsdon MC, Derrick A. Engaging adolescent mothers in a longitudinal mental health intervention study: Challenges and lessons learned. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32:214–9. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2010.544841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Killian-Farrell CL, Rizo CF, Lombardi B, Meltzer-Brody S, Bledsoe SE. Trauma and adolescent perinatal depression risk: Results from a epidemiological study. J Trauma Stress. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulkarni SJ, Lewis CM, Rhodes DM. Clinical challenges in addressing intimate partner violence (IPV) with pregnant and parenting adolescents. J Fam Violence. 2011;26:565–74. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mikolajczyk RT, Bredehorst M, Khelaifat N, Maier C, Maxwell AE. Correlates of depressive symptoms among Latino and non-Latino White adolescents: Findings from the 2003 California Health Interview Survey. BMC Public Health. 2007;21:7–21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breland-Noble A, Burriss A, Poole HK, The AAKOMA PROJECT Advisory Board Engaging depressed African American adolescents in treatment: Lessons from the AAKOMA PROJECT. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:868–79. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho J, Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough R. Parental cultural affiliation and youth mental health service use. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36:529–42. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barker LA, Adelman HS. Mental health and help-seeking among ethnic minority adolescents. J Adolesc. 1994;17:251–63. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brawner BM, Waite RL. Exploring patient and provider level variables that may impact depression outcomes among African American adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;22:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2009.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia CM, Saewyc EM. Perceptions of mental health among recently immigrated Mexican adolescents. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2007;28:37–54. doi: 10.1080/01612840600996257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murry VM, Heflinger CA, Suiter SV, Brody GH. Examining perceptions about mental health care and help-seeking among rural African American families of adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2011;40:1118–31. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Añez LM, Paris M, Bedregal LE, Davidson L, Grio CM. Application of cultural constructs in the care of first generation Latino clients in a community mental health setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:221–30. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bledsoe SE. Barriers and promoters of mental health services utilization in a Latino context: A literature review and recommendations from an ecosystems perspective. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2008;18:151–83. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Breland-Noble AM. Black adolescents. Psychiatr Ann. 2004;34:535–8. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20040701-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandra A, Scott MM, Jaycox LH, Meredith LS, Tanielian T, Bumam A. Racial/ethnic differences in teen and parent perspectives toward depression treatment. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:546–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.10.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Copeland VC. Disparities in mental health service utilization among low-income African American adolescents: Closing the gap by enhancing practitioner’s competence. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2006;23:407–30. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu P, Hoven CW, Cohen P, Liu X, Moore RE, Tiet Q, et al. Factors associated with use of mental health services for depression by children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:189–95. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKay MM, Harrison ME, Gonzales J, Kim L, Quintana E. Multiple-family groups for urban children with conduct difficulties and their families. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1467–68. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shanok AF, Miller L. Depression and treatment with inner city pregnant and parenting teens. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007a;10:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shanok AF, Miller L. Stepping up to motherhood among inner-city teens. Psychol Women Q. 2007b;31:252–61. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cox J, Holden J, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;50:782–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Devins GM, Orme CM, Costello CG, Binik YM, Frizzell B, Stam HJ, et al. Measuring depressive symptoms in illness populations: Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale. Psychol Health. 1988;2:139–56. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weissman MM, Bothwell S. Social adjustment scale by patient self-report. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1976;33:1111–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090101010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.QSR International. NVivo 710 [Computer software] 2006 Available from http://www.qsrinternational.com.

- 56.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedure and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuzel AJ, Like RC. Standards of trustworthiness for qualitative studies in primary care. In: Norton PG, Stewart M, Tudiver F, Bass MJ, Dunn EV, editors. Primary care research: Traditional and innovative approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. pp. 138–58. [Google Scholar]

- 58.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- 59.DeSouza ER, Baldwin J, Koller SH, Narvaz M. A Latin American perspective on the study of gender. In: Paludi MA, editor. Praeger guide to the psychology of gender. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2004. pp. 41–67. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abrahms LS, Curran L. Maternal identity negotiations among low-income women with symptoms of postpartum depression. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:373–85. doi: 10.1177/1049732310385123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henshaw EJ, Flynn HA, Himle JA, O’Mahen HA, Forman J, Fedock G. Patient preferences for clinician interactional style in treatment of perinatal depression. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:936–51. doi: 10.1177/1049732311403499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Davis AA, Rhodes JE, Hamilton-Leaks J. When both parents may be a source of support and problems: An analysis of pregnant and parenting female African American adolescents’ relationships with their mothers and fathers. J Res Adolesc. 1997;7:331–48. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0703_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]