Abstract

Synthetic cathinones found in abused bath salts preparations are chiral molecules. Racemic 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP) are two common constituents of these preparations that have been reported to be highly effective reinforcers; however, the relative contribution of each enantiomer to these effects has not been determined. Thus, male Sprague Dawley rats were trained to respond for racemic MDPV or α-PVP (n=9 per drug), with full dose-response curves for the racemate and the S– and R–enantiomers of MDPV and α-PVP generated under a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Racemic mixtures of both MDPV and α-PVP as well as each enantiomer maintained responding in a dose-dependent manner, with racemic MDPV and α-PVP being equipotent. The rank order of potency within each drug was S–enantiomer > racemate >> R–enantiomer. While both enantiomers of α-PVP were as effective as racemic α-PVP, R–MDPV was a slightly less effective reinforcer than both S– and racemic MDPV. The results of these studies provide clear evidence that both enantiomers of MDPV and α-PVP function as highly effective reinforcers and likely contribute to the abuse-related effects of bath salts preparations containing racemic MDPV and/or α-PVP.

Keywords: bath salts, cathinones, self-administration, enantiomers, rat

Introduction

Racemic mixtures of the synthetic cathinones 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP) are commonly identified in abused bath salts preparations. MDPV and α-PVP are monoamine uptake inhibitors that are selective for the dopamine transporter (DAT) (Baumann et al., 2013; Simmler et al., 2013). Both compounds have been classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration as Schedule I compounds (Drug Enforcement Administration, 2014). Similar to other stimulant drugs of abuse, MDPV and α-PVP have been shown to stimulate locomotor activity, produce cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects, facilitate intracranial self-stimulation, and are readily self-administered (e.g., Fantegrossi et al., 2013; Watterson et al., 2014a; 2014b; Aarde et al., 2015; Kolanos et al., 2015; Gannon et al., 2016; 2017; Collins et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2016).

MDPV and α-PVP are chiral molecules, each with two enantiomers (designated as “R–” and “S–”). Structurally, each enantiomer only differs from the other in its three-dimensional absolute configuration around the chiral center. Pharmacologically, enantiomers can differ from one another in many ways including potency, activity, and mechanism of action. For MDPV, there is inconsistency in the literature with respect to the activity of R–MDPV. For instance, although both enantiomers of MDPV have been shown to inhibit DAT uptake and dose-dependently increase cocaine-appropriate responding in mice trained to discriminate cocaine from saline (although S–MDPV is more potent than R–MDPV) (Kolanos et al., 2015; Gannon et al., 2016), R–MDPV appears to lack cardiovascular effects (at doses up to 3 mg/kg) and fails to facilitate intracranial self-stimulation (at doses up to 10 mg/kg) (Kolanos et al., 2015; Schindler et al., 2016). Although the inability of R-MDPV to facilitate intracranial self-stimulation suggests that it does not contribute to the abuse-related effects of racemic MDPV, the reinforcing effects of each enantiomer of either MDPV or α-PVP have not been reported. Thus, the present study evaluated the self-administration of MDPV, α-PVP, and the R– and S–enantiomers of each drug under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement so that their relative reinforcing potency and effectiveness could be directly compared.

Methods

Subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (275–300 g) obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) were singly housed and maintained in a temperature and humidity-controlled environment on a 10/14-h dark/light cycle with free access to tap water and Purina rat chow. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and the Eighth Edition of the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011).

Surgery

Chronic indwelling catheters were implanted in the left femoral vein under isoflurane anesthesia as previously described (Gannon et al., 2017). Penicillin G (60,000 U/rat; SC) was administered post-surgery to prevent infection. All rats were allowed 5–7 days to recover before initiating experiments. Catheters were flushed daily before (0.2 ml saline) and after (0.5 ml heparinized saline [100 U/ml]) operant sessions.

Apparatus

Standard two-lever operant conditioning chambers (Med Associates, St Albans, VT) situated inside sound attenuating cubicles were used for all experiments. Three LED lights (red, green, and yellow) were located above each lever, and a white houselight was located at the top center of the opposite wall. Drug was delivered via a variable speed syringe pump through Tygon® tubing connected to a stainless steel fluid swivel and spring tether held in place by a counter-balanced arm.

Self-Administration

Illumination of the yellow LED above the active lever (left or right; counterbalanced) signaled drug availability and served as the discriminative stimulus. Completion of the response requirement resulted in a drug infusion (0.1 ml/kg over ~1-sec) paired with the illumination of the houselight and all three lights above the active lever, and initiated a 5-sec timeout. Responding during timeouts or on the inactive lever was recorded but had no scheduled consequence. Rats were trained to respond under a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcement for MDPV or α-PVP (0.032 mg/kg/inf) during daily 90-min sessions. The response requirement increased to an FR5 prior to transitioning rats to a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement where they were maintained for the duration of the experiment. Under this schedule, the response requirements for each successive infusion incremented according to the following equation: Ratio=[5eˆ(inf#*0.2)]−5. The maximum session duration was 12 h, but sessions were terminated if a ratio was not completed within 45 min (i.e., 45-min limited hold). Rats trained to respond for MDPV (n=9) were used to evaluate MDPV (0.0032–0.178 mg/kg/inf), S–MDPV (0.001–0.178 mg/kg/inf), and R–MDPV (0.1–3.2 mg/kg/inf), whereas rats trained to respond for α-PVP (n=9) were used to evaluate α-PVP (0.0032–0.32 mg/kg/inf), S–α-PVP (0.001–0.32 mg/kg/inf), and R–α-PVP (0.1–3.2 mg/kg/inf). The first dose evaluated was 0.032 mg/kg/inf of the racemate, with all remaining doses evaluated in a random order. Each dose was available for at least two consecutive sessions and until stability criteria (±2 infusions from the previous session) were met. All doses for a particular drug were assessed prior to evaluating the next.

Drugs

Racemic MDPV and α-PVP were synthesized by Kenner Rice in the Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD). The enantiomers of both MDPV and alpha-PVP were obtained by optical resolution of the racemate with the appropriate enantiomer of 2-bromotartranilic acid. The optical purity of each of the resolved enantiomers was determined by 400 MHz NMR after the addition of the chiral shift reagent 1-phenyl-2,2,2-trifluoroethanol. In all cases, no optical impurity was detected in any of the 4 resolved enantiomers. The limit of detection of this method was <1.0% as determined by addition of known amounts of optical impurity. Thus, the optical purity of each of the enantiomers was >99%. Our data indicate traces of optical impurity (<1.0% if present at all) in these enantiomers would not influence R/S potency relationships. We have no evidence for any optical impurity in any of the enantiomers. All drugs were prepared fresh daily in 0.9% physiological saline to reduce the likelihood of racemization (see Suzuki et al., 2015).

Data Analysis

Graphical presentations of all data depict the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of the number of infusions obtained at each unit dose. Dose-response data were normalized to the dose condition that maintained the most infusions (i.e., the Emax) for each subject. Normalized dose-response curves were fitted using a linear regression of the data spanning the 20%–80% effect levels to obtain ED50s for individual subjects. ED50 values were considered statistically different between drugs when the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were non-overlapping. One-way ANOVAs, followed by pairwise comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method were used to detect differences in effectiveness among the racemate, S–enantiomer, and R–enantiomer of MDPV or α-PVP. A Student’s t-test was used to detect significant differences between the Emax of MDPV and α-PVP. Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used to generate figures and conduct statistical analyses.

Results

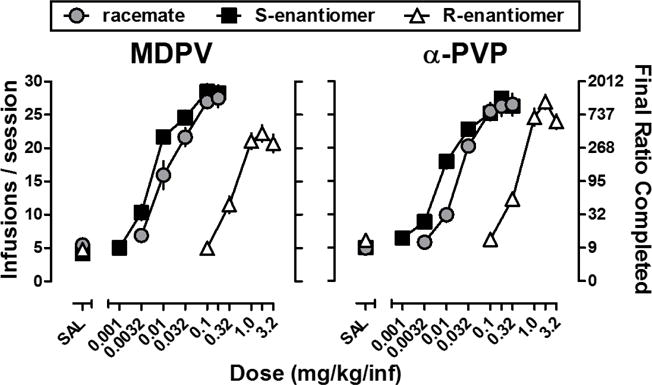

Progressive ratio dose-response curves for MDPV, α-PVP, and their enantiomers are shown in Fig. 1; ED50 and Emax values are provided in Table 1. For MDPV, one-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of drug on the Emax (F[2,16]=19.81, P<0.001), with the Emax for R–MDPV being significantly lower than that for MDPV (P<0.05); Emax values for MDPV and S–MDPV were not significantly different. The Emax for α-PVP was not significantly different from either S– or R–α-PVP. Potency differences were also observed, with S–MDPV being 2.13 (1.58, 2.68)-fold more potent than MDPV, which was 28.86 (20.53, 37.18)-fold more potent than R–MDPV. Similarly, S–α-PVP was 2.05 (1.34, 2.75)-fold more potent than α-PVP, which was 23.04 (16.72, 29.37)-fold more potent than R–α-PVP. Comparisons between MDPV and α-PVP revealed no differences in Emax or potency between MDPV and α-PVP.

Figure 1.

Dose-response curves for the self-administration of racemic (circles), S- (squares), and R-(triangles) MDPV (left panel) or α-PVP (right panel) under a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Horizontal axis: SAL represents data obtained when saline was available for infusion, whereas numbers refer to the unit dose of each drug available for infusion expressed as mg/kg/inf on a log scale. Vertical axis: Left- Total infusions obtained during the session. Right- Final ratio completed during the session. Symbols and error bars depict means ± S.E.M.

Table 1.

ED50 and Emax values for the reinforcing effects of racemic MDPV and α-PVP and their enantiomers.

| ED50 (95% CI) | Emax (± SEM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDPV | α-PVP | MDPV | α-PVP | |

| Racemate | 0.015* (0.012, 0.018) | 0.021* (0.017, 0.027) | 28.3 ± 1.2 | 28.2 ± 1.3 |

| S–enantiomer | 0.008* (0.006, 0.010) | 0.012* (0.009, 0.015) | 29.5 ± 1.2 | 28.7 ± 0.9 |

| R–enantiomer | 0.39* (0.34, 0.44) | 0.45* (0.39, 0.52) | 22.9* ± 1.1 | 27.8 ± 0.8 |

P < 0.05 compared with all drugs (within group). Group sizes: n = 9, MDPV; n = 9, α-PVP.

Discussion

Synthetic cathinone abuse is a worldwide public health concern, with racemic MDPV and α-PVP being two of the most widely abused synthetic cathinones in the United States. Racemic mixtures of MDPV or α-PVP are readily self-administered by rats; however, the reinforcing effects of their enantiomers have not previously been assessed. Therefore, the present study used a PR schedule to quantify and compare the relative reinforcing potency and effectiveness of MDPV, α-PVP, and their respective enantiomers. The results of this study provide strong evidence that both enantiomers of MDPV and α-PVP are highly effective reinforcers and that both enantiomers likely contribute to the maintenance of self-administration by racemic mixtures of MDPV and α-PVP.

Consistent with data reported by Aarde et al. (2015), the present study indicates that MDPV and α-PVP are equipotent and equally effective reinforcers. For both MDPV and α-PVP, the rank order potency to maintain responding was S–enantiomer > racemate >> R–enantiomer, and the S–enantiomer was equally effective as the racemate. Analogous to previous reports with methamphetamine (Yokel and Pickens 1973; Winger et al., 1994), both enantiomers of MDPV and α-PVP were self-administered at high levels. Although the prototypical monoamine transporter inhibitor cocaine is known to have at least one inactive enantiomer, direct comparisons with other inhibitors (e.g., MDPV or α-PVP) are complicated by the fact that cocaine has four chiral centers rather than one. Of note, although R–MDPV was found to be slightly less effective than either MDPV or S–MDPV, the level of responding maintained by R–MDPV is equivalent to that maintained by cocaine or methamphetamine (Gannon et al., 2017), suggesting R–MDPV functions as a highly effective reinforcer.

Since a racemic mixture is composed of approximately 50% of each enantiomer, a 2-fold potency difference between the most potent enantiomer and the racemate would account for the effects of the racemate (assuming the more potent enantiomer is also fully effective). Indeed, S–MDPV and S–α-PVP were ~2-fold more potent than (and equally effective as) MDPV and α-PVP. The self-administration data presented herein for MDPV and its enantiomers parallel the effects of MDPV and its enantiomers on DAT inhibition (Kolanos et al., 2015), providing evidence that the reinforcing effects of MDPV and its enantiomers are related to their ability to inhibit DAT. A similar relationship likely exists for α-PVP and its enantiomers to inhibit DAT; however, these data have not been reported. Although these data suggest that the S–enantiomers could account for the effects of MDPV and α-PVP, the levels of intake maintained by larger unit doses (≥0.032 mg/kg/inf) of MDPV and α-PVP likely result in pharmacologically active levels of R–MDPV and R–α-PVP.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (KCR) and grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA039146 [GTC]; T32 DA031115 [BMG]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared

References

- Aarde SM, Creehan KM, Vandewater SA, Dickerson TJ, Taffe MA. In vivo potency and efficacy of the novel cathinone α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone and 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone: self-administration and locomotor stimulation in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:3045–3055. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3944-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR, Thorndike EB, Hoffman AF, Holy M, et al. Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive ‘bath salts’ products. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(4):552–562. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Abbott M, Galindo K, Rush EL, Rice KC, France CP. Discriminative Stimulus Effects of Binary Drug Mixtures: Studies with Cocaine, MDPV, and Caffeine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;359(1):1–10. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.234252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration. Schedules of controlled substances: temporary placement of 10 synthetic cathinones into Schedule I. Final order. Fed Regist. 2014;79(45):12938–12943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Gannon BM, Zimmerman SM, Rice KC. In vivo effects of abused ‘bath salt’ constituent 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in mice: drug discrimination, thermoregulation, and locomotor activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:563–573. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon BM, Williamson A, Suzuki M, Rice KC, Fantegrossi WE. Stereoselective efffects of abused “bath salt” constituent 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone in mice: drug discrimination, locomotor activity, and Thermoregulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;356(3):615–623. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon BM, Galindo KI, Rice KC, Collins GT. Individual differences in the relative reinforcing effects of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) under fixed and progressive ratio schedules of reinforcement in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;361(1):181–189. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.239376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL, Tirelli E, Witkin JM. Stereoselective effects of cocaine. Behav Pharmacol. 1990;1:347–353. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199000140-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolanos R, Partilla JS, Baumann MH, Hutsell BA, Banks ML, Negus SS, et al. Stereoselective Actions of Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) To Inhibit Dopamine and Norepinephrine Transporters and Facilitate Intracranial Self-Stimulation in Rats. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2015;6(5):771–777. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. eighth. National Academy Press; Washington DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Thorndike EB, Suzuki M, Rice KC, Baumann MH. Pharmacological mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular effects of the “bath salt” constituent 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(24):3492–3501. doi: 10.1111/bph.13640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmler LD, Buser TA, Donzelli M, Schramm Y, Dieu LH, Huwyler J, et al. Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:458–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DA, Negus SS, Poklis JL, Blough BE, Banks ML. Cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects of alphapyrrolidinovalerophenone, methcathinone and their 3,4-methylenedioxy or 4-methyl analogs in rhesus monkeys. Addict Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/adb.12399. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Deschamps JR, Jacobson AE, Rice KC. Chiral resolution and absolute configuration of the enantiomers of the psychoactive “designer drug” 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone. Chirality. 2015;27:287–293. doi: 10.1002/chir.22423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson LR, Burrows BT, Hernandez RD, Moore KN, Grabenauer M, Marusich JA, et al. Effects of α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone and 4-methyl-N-ethylcathinone, two synthetic cathinones commonly found in second-generation “bath salts,” on intracranial self-stimulation thresholds in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014a;18(1) doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson LR, Kufahl PR, Nemirovsky NE, Sewalia K, Grabenauer M, Thomas BF, et al. Potent rewarding and reinforcing effects of the synthetic cathinone 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) Addict Biol. 2014b;19:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winger GD, Yasar S, Negus SS, Goldberg SR. Intravenous self-administration studies with l-deprenyl (selegiline) in monkeys. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;56:774–780. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokel RA, Pickens R. Self-administration of optical isomers of amphetamine and methylamphetamine by rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973;187:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]