Abstract

Signaling proteins and neurotransmitter receptors often associate with saturated chain and cholesterol-rich domains of cell membranes, also known as lipid rafts. The saturated chains and high cholesterol environment in lipid rafts can modulate protein function, but evidence for such modulation of ion channel function in lipid rafts is lacking. Here, using raft-forming model membrane systems containing cholesterol, we show that lipid lateral phase separation at the nanoscale level directly affects the dissociation kinetics of the gramicidin dimer, a model ion channel.

TOC image

Two distinct lifetimes are observed for gramicidin channels in model lipid raft membranes exhibiting lateral domain separation at the nanoscale.

INTRODUCTION

The existence and function of lipid rafts in mammalian cell membranes remain issues of controversy. The association of many membrane proteins with the relatively detergent-resistant membrane fraction of plasma membranes has been well established,1 though the roles of detergents are still issues. Studies of ternary model membrane systems (unsaturated phospholipid, saturated phospholipid, and cholesterol) that separate into liquid ordered (lo) and liquid disordered (ld) domains provide clear evidence for the existence of lipid domains and a firm basis for understanding their properties and their mixing behavior.2 However, while distinct micron-sized domains of different lipid phases are easily demonstrated in model membranes by fluorescence microscopy, such domains are not seen in cell membranes at physiological temperatures, and there is uncertainty as to whether the association of signaling proteins with cholesterol-rich fractions actually occurs in vivo.3 Phase separation in mammalian cell membranes can be demonstrated in membrane blebs depleted of cytoskeletal proteins, but only if cooled well below physiological temperatures.4 Despite the lack of evidence for microscopically visible phase separation, theory and computer simulations5,6 predict the presence of nanoscale separation of lipid clusters within both lo and ld. Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy with live cells demonstrates evidence of hindered diffusion and segregation of lipids at the nanoscale in cell membranes, as well as transient trapping of certain membrane proteins within lipid clusters.7 Trapped proteins are often membrane-associated by palmitoylation and the palmitoyl chain can be associated with small lipid clusters compared to clusters needed to trap transmembrane proteins. Other membrane proteins may be trapped by association with trapped palmitoylated proteins, so lipids and proteins both contribute to formation of special clusters. Moreover, the presence of such clusters in live mammalian cells correlates with activation of the phosphoinositide-3 kinase signaling pathway (PI(3)K/Akt).8 Therefore, both location and, plausibly, function of signaling proteins can be influenced by lipid raft formation even at the nanoscale. However, while the changes in integral features of the membranes were repeatedly shown to modulate channel properties,9 to the best of our knowledge, the ability of nano-sized membrane inhomogeneities to modify channel behavior has not been yet established. Thus, it is of great interest to determine whether, and to what extent, lipid domains at the nanoscale affect channel functioning.

We studied gramicidin A, a well characterized pentadecapeptide produced by Bacillus brevis. Gramicidin inserts into membranes and dimerizes to form cation selective ion channels. The conducting lifetime of these channels is exquisitely sensitive not only to lipid composition,10 but also to compounds that alter membrane mechanics.11, 12 For a lipid raft model, we studied mixtures of dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC), porcine brain sphingomyelin (SPM), and cholesterol (CHL). Porcine brain sphingomyelin is predominantly composed of sphingomyelin with a 16-carbon lipid tail, but contains a heterogeneous variety of sphingomyelins. Giant unilamellar vesicles of the 1/1/1 (mol/mol/mol) mixture exhibit visible phase separation into lo (SPM-rich) and ld (DOPC-rich) domains below 27 °C.13, 14 Above this temperature, separate domains are not visible with light microscopy. However, FRET (Förster Energy Resonance Transfer) and NMR studies suggest the presence of nanoscale domains at higher temperatures, well beyond the microscopically visible miscibility transition.15, 16 In particular, Petruzielo, et al.17 have produced a phase diagram for the SPM/DOPC/CHL mixture, demonstrating enhanced FRET which is consistent with nanodomains extending up to 35 °C in a region of the phase diagram that includes the 1/1/1 mixture used in the present study. Although this is still below physiological temperature, the mixing transitions for lipid mixtures are easily shifted by changes in lipid composition, and real cell membranes are composed of a much more heterogeneous population of lipids than in the present study, as well as many proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC) in chloroform, porcine brain sphingomyelin (SPM), and cholesterol (CHL) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). All reagents were purchased from Sigma. Gramicidin A used for electrophysiology was a generous gift from O. S. Andersen, Cornell University Medical College. Gramicidin used for Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) was purchased from Sigma. CHL and SPM were suspended in chloroform. SPM is insoluble in pure chloroform, so 2% methanol was added.

Gramicidin channel measurements

Membrane bilayers were formed by apposition of two lipid monolayers spread on aqueous solutions of 1 M (mol/L) KCl with 5 mM Hepes at pH 7.4 in a Teflon chamber. Solutions of lipids in chloroform were withdrawn with Hamilton glass syringes, mixed together, evaporated under nitrogen and re-suspended in pentane in 3 mg/ml concentration, with 2% methanol added to solubilize the SPM. The Teflon chamber, with two compartments of 2 ml, was divided by a 15 μm thick Teflon partition (C-Film; CHEMFAB, Merrimack, NH) with a 60–70-μm diameter aperture created by Teflon melting due to proximity to the tip of a hot platinum needle. The aperture in the Teflon film was pretreated with 1% hexadecane in pentane prior to planar membrane formation. DOPC/SPM/CHL lipid mixtures required incubation after addition to the chamber in order to create stable membranes. Incubation times were at least 30 minutes at 42 °C, and sometimes exceeded 90 minutes below 30 °C. Prior to these times, the lipid mixture formed a viscous sheet on the Teflon partition. Stability of DOPC/SPM/CHL membranes was also highly sensitive to batch variation in lipids, especially DOPC. The chamber temperature was controlled by circulating water heated by a thermostatically controlled bath (Lauda E 100) through a brass enclosure surrounding the Teflon chamber. Pulsation artifact from the pump was minimized by including a 10 meter coil of tubing in the line before the enclosure. Temperatures of the aqueous buffer were measured with the probe of a Dagan HCC 100 A heating/cooling bath controller (Dagan Corporation, Minneapolis, MN). It was not possible to record temperatures during an experiment, so the system was calibrated using off-line measurements replicating the experimental conditions with aqueous buffer and lipid layer. At least 10 minutes for equilibration were allowed for every 2 °C change in chamber temperature. This allowed for stable and reproducible chamber temperatures.

The membrane potential was clamped using laboratory-made Ag/AgCl electrodes in 3 M KCl, 1.5% agarose bridges assembled in standard pipette tips. Single channel measurements were performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Inc., Foster City, CA) at 100 mV applied to the membrane in the voltage clamp mode. Data were filtered by a low-pass 8-pole Butterworth filter (Warner Instruments LPF-8) at 2 kHz, and recorded into computer memory using Clampfit (Axon Instruments, Inc.) at a sampling rate of 5 kHz. After bilayer formation stock solutions of gramicidin in ethanol were added at the amount sufficient to give a single-channel activity. (The required gramicidin concentration varied from experiment to experiment, depending upon the amount of lipid in the chamber, lipid batch, the size of the hole in the partition, and temperature, ranging from 3 × 10−13 M to 10−10 M.) Sufficient concentrations of gramicidin were used so that the total amount of ethanol added to the 1.5 ml aqueous volume did not exceed 2 μl. Data were analyzed using pClamp 9.2 software (Axon Instruments, Inc.). A digital 8-pole Bessel low pass filter set at 200 Hz was applied to all records and then single channels were discriminated. Channel lifetimes were collected as described previously18 and calculated by fitting logarithmic exponentials to logarithmically binned histograms.19 Each data-point in Fig. 2 is a mean lifetime of at least 3 independent experiments ± σ. The mean number of events for each experiment on the 1/1/1 mixture was 860 (range 183 to 1853). All lifetime histograms used 10 bins per decade. All conductance histograms used a bin width of 0.1 pA. Fits to histograms used the Maximum Likelihood Estimator with the Simplex Algorithm. To accept a 2-exponential fit, we required the logarithm of the likelihood ratio of the 2-exponential and 1-exponential fits to exceed 18. This ratio follows a chi-square distribution with 2 degrees of freedom.20 A value of 18 corresponds to a probability of < .000221 that the two-channel fit is better by chance than the single channel fit. The likelihood ratio of lifetimes for selected experiments was tested for sensitivity to histogram bin width with histograms ranging from 10 to 20 bins per decade and found to be unchanged.

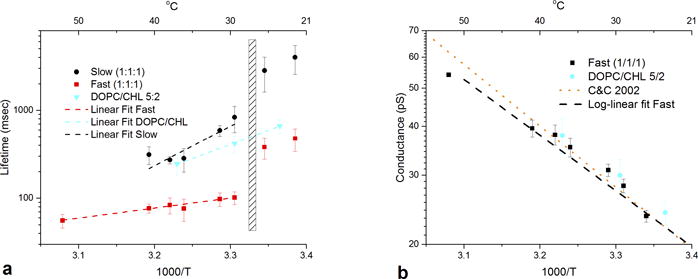

Figure 2.

a) lifetimes of gramicidin channels plotted against inverse temperature. black circles represent lifetimes for slow channels in dopc/spm/chl 1/1/1, red squares represent fast channels in dopc/spm/chl 1/1/1. blue triangles represent lifetimes of gramicidin in dopc/chl 5:2. error bars represent standard deviations of the means. cross hatched area represents the approximate location of the miscibility transition for the 1/1/1 mixture. b) conductance for fast gramicidin channels in the 1/1/1 mixture (black squares) and for channels in dopc/chl 5/2. black dashed line represents a log-linear fit to the fast channel lifetimes (r sq = .96). data from reference (34) for gramicidin in diphytanolyphosphatidylcholine membranes is replotted for comparison (orange dotted line). see si for lifetime and conductance plots against temperature in centigrade.

Calorimetry

Mixtures were compounded with Hamilton syringes from lipids dissolved in chloroform into a vial. Mixtures were heated in a water bath at 55 °C, and the chloroform evaporated under a stream of nitrogen. The vials with dried lipids were placed in vacuum overnight. Lipids were then heated again to 55 °C, and distilled water at 55 °C was added to the vial to achieve the desired lipid concentrations (25 mg/ml for DOPC/SPM/CHL 2/2/1; 30 mg/ml for DOPC/SPM/CHL 1/1/1; DPPC 5 mg/ml). To control for the effect of gramicidin we estimated the concentration of gramicidin in the lipid bilayer used for the electrophysiology experiments as approximately 3 molecules per million molecules of lipid (see Supplementary Information for details of the calculation). To eliminate the concern that gramicidin perturbed the distribution of lipids in the bilayers, we then added 100 times this amount (10−8 M of gramicidin from Sigma) to a sample of 27 mg of lipid (4 × 10−5 M) made as above. Vials were vortexed vigorously for 2 minutes, intermittently returning the vials to the water bath to maintain their temperature. The lipids were then subjected to five cycles of freeze-thaw with liquid nitrogen. This procedure results in multi-lamellar vesicles of uniform size and lamellar thickness.22 After degassing for at least one hour, samples were loaded onto a DSC III differential scanning calorimeter (Calorimetry Sciences Corporation, Linden, Utah). Scans were performed between 60 °C and 5 °C at 1 °/minute with alternating cooling and heating scans, and repeated multiple times to ensure reproducibility. The 2/2/1 mixture produced identical results with both heating and cooling scans; however, the 1/1/1 mixture had large artifacts at low temperatures with heating scans, probably due to the high viscosity of the mixture at these temperatures. Therefore, we display cooling scans. Instrument artifact contaminates the first 10 degrees of the scans, but these artifacts vanish by 50 °C.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

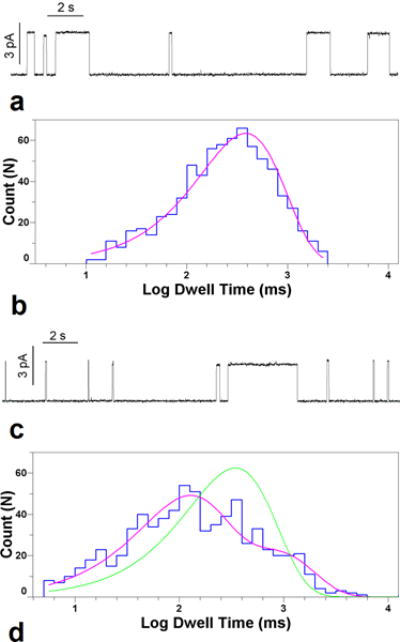

Fig. 1 illustrates the electrophysiology of gramicidin channels inserted into planar bilayers of lipid raft mixtures. Gramicidin in a DOPC/CHL 5/2 mixture (Fig. 1a) produces channels with the features characteristic for single-component lipid bilayers: nearly uniform conductance and lifetimes closely fit by a single exponential distribution (Fig. 1b). A previous study of gramicidin inserted into planar bilayers of a DOPC/distearoylphosphatidylcholine/CHL lipid raft mixture23 demonstrated only a single lifetime at temperatures below the miscibility transition, and simultaneous fluorescence microscopy in this study confirmed that the gramicidin is excluded from the DSPC-rich domains. However, when gramicidin is introduced into planar bilayers of a 1/1/1 mixture of DOPC/SPM/CHL, channels of relatively long duration (slow channels) are mixed with (fast) channels of much shorter duration (Fig. 1c). Approximately 10 times the amount of gramicidin was required to obtain channels in the 1/1/1 mixture compared with the DOPC/CHL 5/2 mixture. It is known that gramicidin in lipid bilayers comprised of lipids with high intrinsic curvature and greater packing stress (e.g., DOPE) requires considerably higher concentration to form channels and demonstrates much shorter channel lifetimes than does gramicidin in a low curvature lipid, such as DOPC,11 so one could have expected to see a larger number of longer lifetime channels in the 1/1/1 mixture.

Figure 1.

a) gramicidin channels in 5/2 dopc/spm/chl at 30 °C, 1 m kcl, 100 mv. horizontal bar is 2 sec in length. vertical bar is 3pa. b) logarithmically binned histogram of gramicidin lifetimes in 5/2/ dopc/chl at 30 °C and single exponential fit to log probability. c) gramicidin channels in 1/1/1 dopc/spm/chl at 32 °C (7 °C above miscibility transition for this mixture)), 1 m kcl, 100 mv. horizontal bar is 2 sec in length. vertical bar is 3pa. d) logarithmically binned histogram of gramicidin lifetimes in 1/1/1 dopc/spm/chl at 32 °C with single exponential (green trace) and double exponential fits (fuchsia trace).

However, the appearance and disappearance of conducting gramicidin channels is a complex phenomenon even in membranes of single lipid composition.24 In the present study, the situation is further complicated by the possibilities of differential partitioning of gramicidin monomers from the bulk into the lipid phases, partitioning between the phases, and the dynamics of phase distribution in the membrane. Indeed, the proportion of fast and slow channels was not always stable within an experiment. Among additional unknowns are the exact chemical composition and volumes of the domains and even the geometries of the boundaries between them, with a possibility that channels form at the domain boundaries. All these factors limit our ability to quantitatively estimate the rate constants of channel formation. It is also important to distinguish between the number of events per unit time and the average probability of finding gramicidin in the dimerized state. This latter quantity is important for the thermodynamic analysis of the dimerization reaction. For the data in Figure 1, the probability that gramicidin is in a slow channel dimer is actually 4 times higher than in a fast channel dimer.

The histogram of channel lifetimes (Fig. 1d) cannot be reasonably approximated by a single exponential model, but requires at least two separate distributions corresponding to processes with different lifetimes. To ensure that the two channel lifetimes were significantly different, we required that the log likelihood ratio between the two-lifetime fit and the single lifetime fit exceeded 18 (p < .0002, Experimental). Most records greatly exceeded this value.

The lifetimes of both fast (red squares) and slow channels (black circles) vary with temperature. Fig. 2a displays channel lifetime plotted against inverse temperature in Kelvin (see Supplementary Information for plots against degrees C). At high temperatures (51.8 °C) only one lifetime is seen. At cooler temperatures, a second, longer lifetime channel emerges. Even at 40.2 °C (13 °C above the reported transition temperature for this mixture) two lifetimes are evident, although only in a minority of experiments (three out of eight). At lower temperatures, 31.3 °C and 29.5 °C, channels with two separate lifetimes are seen in nearly all experiments (11 out of 14). In the region of the miscibility transition, 27 °C to 28 °C, the membrane becomes unstable, with the emergence of large-conductance lipid pores, as previously described in planar bilayers of lipid mixtures.25 This transition is slightly higher than that observed in giant unilamellar vesicles, probably because of the different geometry involved in planar bilayers. However, as Veatch and Keller13 note, the 1/1/1 mixture has considerable sensitivity to minute changes in lipid composition. We also find sensitivity to batch variability in lipids, especially DOPC. Below the miscibility transition, membranes demonstrate limited stability, and the emergence of large numbers of low conductance “mini-channels”26 precludes long recordings and makes analysis difficult. Nonetheless, the presence of two separate lifetime distributions persists at temperatures below the miscibility transition. For comparison, the lifetime of gramicidin channels in bilayers composed of DOPC/CHL 5/2 is also plotted (blue triangles) through this temperature range. Only a single channel lifetime is observable at any temperature.

The data for DOPC/CHL are consistent with the spring model of Lundbaek and Andersen12 for gramicidin-induced deformations in lipid bilayers and can be described as ln (τ) = ΔG/RT + C where τ is the channel lifetime, and ΔG is the height of the transition state barrier represented by the difference between the free energies of gramicidin dimer binding and that of membrane deformation. The data are fit by a straight line (r2 = 0.99), with the slope giving an effective ΔG as 14.7 kcal/mol. It is evident that the data for neither of the lifetimes observed in the 1/1/1 mixture can be fit by this model across the entire temperature range.

We tentatively identify the slow channels as gramicidin inserted into the ld DOPC-rich domains and the fast channels as gramicidin inserted into lo SPM-rich domains or boundary regions because of two observations: 1) The lifetime of DOPC/CHL 5/2 at 36.6 °C is very close to that of the slow channels in this temperature range, and 2) Gramicidin inserted into SPM/CHL (3/2) at 42.3 °C produces very fast channels with a duration under 3 ms (Fig. S5).

For the data above the microscopic miscibility transition (data-points to the left of the rectangle in Fig. 2a), lifetimes of both slow and fast channels are reasonably well fit (r2 = .83 and .97, respectively) by straight lines. The corresponding effective ΔG values can be estimated as 20.6 and 5.2 kcal/mol for the slow and fast channels, respectively. The slope of the slow channel lifetime dependence is higher than that for the DOPC/CHL, with the smallest slope measured for the fast channels (Fig. 2a). It is worth mentioning here that the slopes of the temperature dependences allow only for evaluation of an “effective” height of the barrier. Indeed, the approach assumes a temperature-independent ΔG27 while there are at least two factors suggesting that the actual situation is more complex. The first one is the temperature-induced change of the membrane mechanical parameters, such as thickness and bending rigidity,28 the phenomenon that is presumably quite general and applies to both single-phase and two-phase bilayers. The second one is redistribution of lipids between the phases in the two-phase bilayers with temperature.29 Both will change the “pull” on the gramicidin dimer in a temperature-dependent manner, thus complicating evaluation of ΔG values from the temperature data. In the case of the 1/1/1 system studied here, our interpretation is that the movement of DOPC out of the SPM-rich lo domains with decreasing temperature decreases ΔG for gramicidin in these domains, offsetting the Boltzmann factor. Conversely, the movement of SPM out of the ld DOPC-rich domains increases ΔG in these domains, leading to longer lifetimes.

The membrane mechanics of the 1/1/1 mixture, as experienced by gramicidin, clearly undergo a major shift in the region of the microscopic miscibility transition. A recent study in vesicles of a binary lipid mixture30 demonstrates highly non-linear changes in bending modulus and the relaxation time of marked membrane thickness fluctuations through the mixing transition, in line with the discontinuity in channel lifetimes observed in the present data.

No consistent difference in channel conductance was observed for the two populations of channels at any temperature (see Figs. S3 and S4 for histograms of channel conductance in the 1/1/1 mixture and DOPC/CHL 5/2). How lipid bilayer composition affects conductance in gramicidin channels is still not well understood, as additions of cholesterol,31 cardiolipin,32 and other membrane active agents11, 33 cause obvious changes in gramicidin lifetime, but only very modest changes in gramicidin conductance. This is also true for the channels in PC/PE membranes of increasing PE content, where the 5-fold lifetime decrease at 50% PE is accompanied by barely measurable changes in conductance (See Fig. S6 for a plot of lifetime and conductance vs. PE/PC membrane composition). Fig. 2b displays the plot of gramicidin conductance vs. inverse temperature for the 1/1/1 mixture (black squares) and DOPC/CHL (blue circles). The plot for the 1/1/1 mixture is well fit by a straight line (black dashed line, r2 = 0.96), and the data for DOPC/CHL lies along a parallel line that is not significantly different. For comparison, data from a study of gramicidin potassium conductance in diphytanoylphosphatydlcholine bilayers34 is replotted (orange dotted line – fitting only) and demonstrates nearly identical results. Thus, the temperature dependence of gramicidin conductance does not appear to be greatly affected by lipid composition.

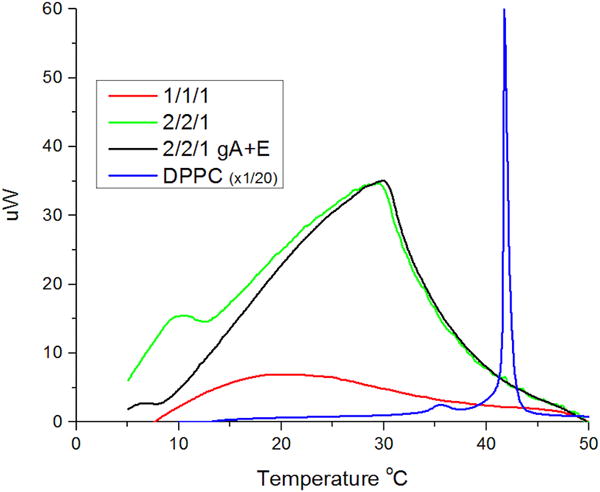

Gramicidin in sufficient concentration can affect the structure of phospholipid bilayers.35 In some ternary raft mixture bilayers it can slightly perturb phase behavior36 but this is reported to happen only at large concentrations (5 mol %). Nevertheless, we wanted to determine whether the much smaller concentrations of gramicidin in the present study might be affecting the mixing transition. Fig. 3 displays differential scanning calorimetry thermograms from multilamellar vesicles of different lipid composition. Vesicles composed of the 1/1/1 mixture (red trace) exhibit a very broad and small increase in heat capacity throughout the mixing transition, as compared with vesicles formed of the 2/2/1 mixture (green trace) which exhibit a clear peak in the thermogram at 30 °C with a gradual decay. The trace for the 2/2/1 mixture is consistent with its reported microscopic miscibility transition of 37 °C13, while the thermogram for the 1/1/1 vesicles indicates continuing phase mixing above the microscopic miscibility transition, consistent with the NMR and FRET studies cited above. Since the peak for the 1/1/1 mixture was so broad, we tested the effect of preparing vesicles of the 2/2/1 mixture with 100 times the concentration of gramicidin and twice the amount of ethanol to that present in the electrophysiology experiments (see Experimental for details). This trace (black) displays no significant difference in the location of the peak, indicating no significant effect of the gramicidin and ethanol on the mixing transition. For reference, we also display the thermogram for dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (blue trace) that undergoes a simple, first order phase transition.

Figure 3.

differential scanning calorimetry of lipid mixtures. scans are records from cooling scans staring at 60 °C and ending at 5° C, at a rate of 1 °C/minute. green line represents dopc/spm/chl 2/2/1 multilamellar vesicle 25 mg/ml. the black line represents dopc/spm/chl multilamellar vesicle 25 mg/ml with 100× the amount of gramicidin and twice the amount of ethanol used in electrophysiology experiments. the red line represents dopc/spm/chl 1/1/1 multilamellar vesicles 30mg/ml. the blue line represents dppc 5 mg/ml at 1/20 the scale for reference.

CONCLUSIONS

The gramicidin ion channel appears to detect the presence of separate nanoscale domains in the 1/1/1 mixture well above the microscopic miscibility transition as reported by fluorescence microscopy. Results obtained from STED fluorescence correlation spectroscopy of live mammalian cells demonstrate local trapping of lipids in nanodomains for periods of up to 10 seconds.37 Of particular interest for neurophysiology, we note that the proportion of cholesterol in nerve cell membranes is quite high, about 43%38 and that cholesterol depletion in live mammalian cells inhibits both raft nanodomain formation and activation of the (PI(3)K/Akt) pathway.8 The present findings finally demonstrate that nanodomains in cholesterol rich membranes also affect ion channel function. While the structure of gramicidin differs from that of mammalian ion channels, many of the fundamental principles of ion conduction through channels were first demonstrated with gramicidin, and its sensitivity to the surrounding lipid environment is a property shared by a significant number of ion channels involved in synaptic signaling, e.g., potassium channels.39 We suggest that perturbations of lipid phase mixing produced by application of membrane active agents40 or hydrostatic pressure41 could affect nervous system function through interactions at the nanoscale. This hypothesis will ultimately require verification with mammalian ion channels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sergey Leikin for the use of his calorimeter.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD.

ABBREVIATIONS

- lo

liquid ordered

- ld

liquid disordered

- PI(3)K/Akt

phosphoinositide-3 kinase

- DOPC

dioleoylphosphatidylcholine

- SPM

porcine brain sphingomyelin

- CHL

cholesterol

- DPPC

dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- τ

channel lifetime

- ΔG

free energy

- R

gas constant

- T

temperature

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Additional figures illustrating channel lifetime and conductance plotted against temperature in Centigrade, amplitude histograms, trace of gramicidin channels in SPM/CHL, and experimental notes. This material is available free of charge at

Author Contributions

All of the authors reviewed the data, edited and approved the final draft of the manuscript. MW performed the electrophysiology and calorimetry. DLW performed the calorimetry. SMB built the temperature control.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The identification of any commercial product or trade name does not imply any endorsement or recommendation by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

References

- 1.Lingwood D, Simons K. Science. 2010;327:46–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1174621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feigenson GW. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenberg D, Goni FM, Heerklotz H. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgart T, Hammond AT, Sengupta P, Hess ST, Holowka DA, Baird BA, Webb WW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3165–3170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611357104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmid F. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1859:509–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meinhardt S, Vink RL, Schmid F. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4476–4481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221075110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggeling C, Ringemann C, Medda R, Schwarzmann G, Sandhoff K, Polyakova S, Belov VN, Hein B, von Middendorff C, Schonle A, Hell SW. Nature. 2009;457:1159–1162. doi: 10.1038/nature07596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lasserre R, Guo XJ, Conchonaud F, Hamon Y, Hawchar O, Bernard AM, Soudja SM, Lenne PF, Rigneault H, Olive D, Bismuth G, Nunes JA, Payrastre B, Marguet D, He HT. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:538–547. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundbaek JA, Collingwood SA, Ingolfsson HI, Kapoor R, Andersen OS. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7:373–395. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neher E, Eibl H. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;464:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(77)90368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinrich M, Rostovtseva TK, Bezrukov SM. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5501–5503. doi: 10.1021/bi900494y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundbaek JA, Andersen OS. Biophys J. 1999;76:889–895. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77252-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veatch SL, Keller SL. Biophys J. 2003;85:3074–3083. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74726-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietrich C, Bagatolli LA, Volovyk ZN, Thompson NL, Levi M, Jacobson K, Gratton E. Biophys J. 2001;80:1417–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathak P, London E. Biophys J. 2011;101:2417–2425. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.08.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filippov A, Oradd G, Lindblom G. Biophys J. 2006;90:2086–2092. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.075150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petruzielo RS, Heberle FA, Drazba P, Katsaras J, Feigenson GW. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828:1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rostovtseva TK, Petrache HI, Kazemi N, Hassanzadeh E, Bezrukov SM. Biophys J. 2008;94:L23–25. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigworth FJS, M S. Biophysical Journal. 1987;52:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horn R. Biophys J. 1987;51:255–263. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83331-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinov I. Normal, Student’s T, Chi-Square and F Statistical Tables. 2016 http://socr.ucla.edu/Applets.dir/Normal_T_Chi2_F_Tables.htm.

- 22.Holland GP, McIntyre SK, Alam TM. Biophys J. 2006;90:4248–4260. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.077289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honigmann A, Walter C, Erdmann F, Eggeling C, Wagner R. Biophys J. 2010;98:2886–2894. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen OS, Bruno MJ, Sun H, Koeppe RE., 2nd Methods Mol Biol. 2007;400:543–570. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-519-0_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blicher A, Wodzinska K, Fidorra M, Winterhalter M, Heimburg T. Biophys J. 2009;96:4581–4591. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Busath D, Szabo G. Biophys J. 1988;53:689–695. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nestorovich EM, Karginov VA, Berezhkovskii AM, Parsegian VA, Bezrukov SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18453–18458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208771109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan J, Tristram-Nagle S, Kucerka N, Nagle JF. Biophys J. 2008;94:117–124. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.115691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veatch SL, Polozov IV, Gawrisch K, Keller SL. Biophys J. 2004;86:2910–2922. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74342-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashkar R, Nagao M, Butler PD, Woodka AC, Sen MK, Koga T. Biophys J. 2015;109:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pope CG, Urban BW, Haydon DA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;688:279–283. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90605-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rostovtseva TK, Kazemi N, Weinrich M, Bezrukov SM. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37496–37506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundbaek JA, Birn P, Tape SE, Toombes GE, Sogaard R, Koeppe RE, 2nd, Gruner SM, Hansen AJ, Andersen OS. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:680–689. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.013573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chernyshev A, Cukierman S. Biophys J. 2002;82:182–192. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75385-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szule JA, Rand RP. Biophys J. 2003;85:1702–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74600-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Periasamy N, Winter R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vicidomini G, Ta H, Honigmann A, Mueller V, Clausen MP, Waithe D, Galiani S, Sezgin E, Diaspro A, Hell SW, Eggeling C. Nano Lett. 2015;15:5912–5918. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takamori S, Holt M, Stenius K, Lemke EA, Gronborg M, Riedel D, Urlaub H, Schenck S, Brugger B, Ringler P, Muller SA, Rammner B, Grater F, Hub JS, De Groot BL, Mieskes G, Moriyama Y, Klingauf J, Grubmuller H, Heuser J, Wieland F, Jahn R. Cell. 2006;127:831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt D, MacKinnon R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19276–19281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810187105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinrich M, Worcester DL. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:16141–16147. doi: 10.1021/jp411261g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Worcester DL, Weinrich M. J Phys Chem Lett. 2015;6:4417–4421. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.