Abstract

Background

Scaling up HIV prevention for people who inject drugs (PWID) using opioid agonist therapies (OAT) in Ukraine has been restricted by individual and structural factors. Extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX), however, provides new opportunities for treating opioid use disorders (OUDs) in this region, where both HIV incidence and mortality continue to increase.

Methods

Survey results from 1613 randomly selected PWID from 5 regions in Ukraine who were currently, previously or never on OAT were analyzed for their preference of pharmacological therapies for treating OUDs. For those preferring XR-NTX, independent correlates of their willingness to initiate XR-NTX were examined.

Results

Among the 1,613 PWID, 449 (27.8%) were interested in initiating XR-NTX. Independent correlates associated with interest in XR-NTX included: being from Mykolaiv (AOR=3.7, 95% CI= 2.3–6.1) or Dnipro (AOR=1.8, 95% CI=1.1–2.9); never having been on OAT (AOR=3.4, 95% CI=2.1–5.4); shorter-term injectors (AOR=0.9, 95% CI 0.9–0.98); and inversely for both positive (AOR=0.8, CI=0.8–0.9), and negative attitudes toward OAT (AOR=1.3, CI=1.2–1.4), respectively.

Conclusions

In the context of Eastern Europe and Central Asia where HIV is concentrated in PWID and where HIV prevention with OAT is under-scaled, new options for treating OUDs are urgently needed. Findings here suggest that XR-NTX could become an option for addiction treatment and HIV prevention especially for PWID who have shorter duration of injection and who harbor negative attitudes to OAT. Decision aids that inform patient preferences with accurate information about the various treatment options are likely to guide patients toward better, patient-centered treatments and improve treatment entry and retention.

Keywords: extended-release naltrexone, patient preferences, opioid dependence, people who inject drugs (PWID), HIV prevention, opioid agonist therapies

1. Introduction

The Eastern European and Central Asian region remain the only region globally where HIV incidence and mortality continue to increase (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), 2016a). Ukraine’s HIV epidemic, emblematic for the region, remains concentrated in people who inject drugs (PWID), mostly of opioids, and in their sexual partners (Kiriazova et al., 2013; Mazhnaya et al., 2014). High methadone coverage is the most cost-effective strategy to avert new HIV infections in Ukraine (Alistar et al., 2011), including in prisoners (Altice et al., 2016). Scale-up of opioid agonist therapies (OAT) in Ukraine began with the introduction of maintenance therapy using buprenorphine (BMT) in 2004 (Bruce et al., 2007), followed by methadone (MMT) in 2008 (Lawrinson et al., 2008). OAT scale-up has not, however, increased appreciably since 2010, despite targets to provide OAT at no cost to 20,000 PWID by 2015 (Dutta et al., 2013); currently only 2.7% of the 340,000 PWID are prescribed it (Degenhardt et al., 2014; Wolfe et al., 2010). Numerous individual and structural factors have impeded OAT scale-up in Ukraine (Bojko et al., 2013; Bojko et al., 2015; Bojko et al., 2016a; Izenberg et al., 2013; Mazhnaya et al., 2016; Mimiaga et al., 2010), including negative attitudes toward OAT by both patients and providers (Bojko et al., 2015; Makarenko et al., 2016; Makarenko et al., 2017c; Polonsky et al., 2015; Polonsky et al., 2016c). MMT and BMT were introduced in Ukraine initially for the prevention of HIV, and not for the treatment of opioid use disorders (OUD).

Extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) was approved to treat alcohol dependence in Ukraine in 2008 and opioid use disorders in 2014. XR-NTX, however, was introduced commercially, unlike MMT and BMT the other two evidence-based medication-assisted therapies (MAT) introduced in 2004 and 2008 for treating opioid use disorders. Because XR-NTX is a complete opioid antagonist, it does not require patients to undergo official “registration” as a drug user, which often results in the loss of one’s driver’s license, employment restrictions (Bojko et al., 2013; Bojko et al., 2015) and promotes police harassment (Bojko et al., 2015; Izenberg et al., 2013; Kutsa et al., 2016; Polonsky et al., 2016a). Once-monthly injections overcome such structural barriers as daily transportation for direct supervision (Alanis-Hirsch et al., 2016; Cousins et al., 2016), but are costly to patients because they are not supported by international donors or provided free by the government.

In March 2016, the Ministry of Health Order 200 that regulates OAT delivery was changed, allowing OAT to be prescribed outside addiction specialty settings, for purchase in pharmacies and take-home doses allowed for 7–10 days. This change opened new opportunities for XR-NTX patients who can now avoid inpatient supervised withdrawal (“detox”) and can taper off opioids using buprenorphine purchased in ambulatory settings. Given the current treatment milieu, XR-NTX can also be administered to incarcerated persons transitioning to the community within inpatient programs that “detox” patients. XR-NTX, as a complete opioid antagonist, might overcome negative attitudes toward OAT (Polonsky et al., 2016c) and be attractive to patients and providers. It also may provide new opportunities for concomitant treatment for patients with both alcohol and opioid use disorders, which co-occur often in Ukraine (Azbel et al., 2013). Last, its pharmacological properties avoid sedation and drug interactions with HIV or tuberculosis medications (Altice et al., 2010), and when not interrupted, prevent overdose.

In the presence of suboptimal OAT scale-up and a changing legal landscape for addiction treatment, we analyzed survey data from an implementation science study focusing on the expansion of MAT in Ukraine. Specifically, the objectives of the study were to better understand PWID’s knowledge about and willingness to receive XR-NTX as an alternative MAT to treat opioid use disorders in Ukraine and to inform patient preferences and alternative strategies for treating opioid use disorders and to guide how to clinically position XR-NTX as an additional strategy to prevent HIV in this especially volatile region where HIV is concentrated in PWID (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), 2016a).

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

Detailed methods for the cross-sectional survey have been published previously (Makarenko et al., 2016; Makarenko et al., 2017b). Briefly, from January 2014 to March 2015, PWID 18 years or older and meeting ICD-10 criteria for OUDs were randomly recruited from five geographically distinct regions of Ukraine. Participants were stratified by their OAT status: ‘currently’, ‘previously’, or ‘never’ on OAT. PWID who were never on OAT were recruited using respondent-driven sampling, while current and previous OAT clients were randomly selected from OAT treatment rosters. Surveys were developed based on formative focus group data, self-administered and collected online using Qualtrics®. A standardized script was provided that described the objective attributes of XR-NTX. The instructions for respondents provided by the interviewer stated, “Naltrexone is a full antagonist of opioid receptors. This means the medication can block receptors and doesn’t allow a person to get high after using heroin or other opioid agonists like morphine, codeine, methadone, etc. Naltrexone is a medication that can be administered as tablets every day. There is also a form of naltrexone, which can be injected and continues to work for about one month. This is extended-release naltrexone is called Vivitrol. After the injection, a person can’t get high from using heroin or other opioid agonists during the month when Vivitrol is within the body.” Trained research assistants were available to clarify any survey item meanings and provide technical assistance. XR-NTX questions assessed awareness of, interest in, and preference for receiving this type of MAT. Participants were compensated 100UAH (~$4) for survey completion. Few, if any, participants approached refused study participation.

2.2. Measures

In addition to demographic and social characteristics, the survey assessed drug use and treatment experiences, HIV status and testing, and standardized measures of alcohol use disorders (Saunders et al., 1993), depression (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977), addiction severity (DAST-10) (Gavin et al., 1989), and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (Ware et al., 1996). HIV and HCV testing and post-test counseling were conducted by licensed medical staff using rapid tests (CITO TEST HIV 1/2/0 and CITO TEST HCV).

Willingness to initiate XR-NTX was the primary outcome. This was assessed by asking respondents if they could choose any MAT available to treat their opioid use disorder, which of the following would they choose to initiate now (all are available in Ukraine): 1) daily sublingual buprenorphine tablet, 2) daily buprenorphine injection, 3) daily methadone tablet, 4) daily methadone liquid, 5) oral naltrexone, or 6) once-monthly XR-NTX injection. For the current analysis we constructed a binary outcome variable, XR-NTX vs. all other available treatment options. Binary and independent correlates of a preference for XR-NTX versus any other treatment option are presented in Table 1. Age and years of drug injection were continuous. The following were binary: last 30-day drug injection frequency (>20 days versus ≤ 20 days), alcohol use disorders (AUDIT ≥4 for women and ≥8 for men) (Saunders et al., 1993), moderate/severe addiction severity (DAST-10 ≥3)(Gavin et al., 1989), moderate/severe depression (CES-D >10)(Radloff, 1977) and previous incarceration. We used previously published methods (Makarenko et al., 2016; Polonsky et al., 2016a; Polonsky et al., 2016b; Polonsky et al., 2016c) for creating two continuous composite variables reflecting both “positive” and “negative” attitudes toward OAT (MMT or BMT).

Table 1.

Characteristics of structured survey participant stratified by experience with opioid agonist treatments, N=1,613

| Characteristic | Opioid Agonist Experience | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current (N=434) | Previous (N=279) | Never (N=900) | ||

| City | <0.0001 | |||

| Kyiv | 140 (32.3) | 79 (28.3) | 198 (22.0) | |

| Odesa | 47 (10.8) | 18 (6.4) | 150 (16.7) | |

| Mykolaiv | 105 (24.2) | 98 (35.1) | 141 (15.7) | |

| Dnipro | 102 (23.5) | 59 (21.2) | 207 (23.0) | |

| Lviv | 40 (9.2) | 25 (9.0) | 204 (22.7) | |

| Age – median (IQR) | 36 (32–43) | 37 (32–44) | 34 (28–41) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | 0.1376 | |||

| Male | 340 (78.3) | 201 (72.0) | 692 (76.9) | |

| Female | 94 (21.7) | 78 (28.0) | 208 (23.1) | |

| Married/in relationship | 0.0671 | |||

| Yes | 168 (38.7) | 104 (37.3) | 294 (32.7) | |

| No | 266 (61.3) | 175 (62.7) | 606 (67.3) | |

| Employment | 0.2057 | |||

| Full time/part time | 204 (47.0) | 147 (52.7) | 401 (44.6) | |

| Temporal/seasonal | 70 (16.1) | 37 (13.3) | 147 (16.3) | |

| Not employed | 160 (36.9) | 95 (34.0) | 352 (39.1) | |

| Registered as a drug user | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 366 (84.3) | 235 (84.2) | 299 (33.2) | |

| No | 68 (15.7) | 44 (15.8) | 601 (66.8) | |

| Self-reported HIV status | <0.0001 | |||

| Positive | 194 (44.7) | 139 (49.8) | 240 (26.7) | |

| Negative | 219 (50.5) | 111 (39.8) | 332 (36.9) | |

| Unknown | 21 (4.8) | 29 (10.4) | 328 (36.4) | |

| Drug treatment experience | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 421 (97.0) | 272 (97.5) | 435 (48.3) | |

| No | 13 (3.0) | 7 (2.5) | 465 (51.7) | |

| Medication-assisted detox experience | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 222 (51.1) | 180 (64.5) | 215 (23.9) | |

| No | 212 (48.9) | 99 (35.5) | 685 (76.1) | |

| Duration of injection drug use | <0.0001 | |||

| >5 years | 428 (98.6) | 274 (98.2) | 735 (81.7) | |

| ≤ 5 years | 6 (1.4) | 5 (1.8) | 165 (18.3) | |

| Injecting drugs in the last 30 days | <0.0001 | |||

| > 20 days | 23 (5.3) | 65 (23.3) | 521 (57.9) | |

| ≤ 20 days | 411 (94.7) | 214 (76.7) | 379 (42.1) | |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | <0.0001 | |||

| No | 335 (77.2) | 188 (67.4) | 466 (51.8) | |

| Yes | 99 (22.8) | 91 (32.6) | 434 (48.2) | |

| Drug Addiction Severity | <0.0001 | |||

| No problem/Low level | 42 (9.7) | 17 (6.1) | 30 (3.3) | |

| Moderate/Severe level | 392 (90.3) | 262 (93.9) | 870 (96.7) | |

| Have been in prison/SIZO | 0.0157 | |||

| Yes | 237 (54.6) | 161 (57.7) | 460 (51.1) | |

| No | 197 (45.4) | 118 (42.3) | 440 (48.9) | |

| Depressive symptoms (moderate to severe) | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 196 (45.2) | 142 (50.9) | 520 (57.8) | |

| No | 238 (54.8) | 137 (49.1) | 380 (42.2) | |

2.3. Statistical Analysis

After bivariate analyses were performed using chi-square test for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables, backwards selection was used in the multivariable logistic regression to identify independent factors associated with being willing to initiate XR-NTX, with covariates significant at p<0.10 in bivariate analyses being included in the final model. This analytical strategy provided the best goodness-of-fit relative to other models. Data for all analyses were weighted based on population estimates in each type of OAT experience (currently on, previously on, and never on OAT) for each city sampled. The population estimates for two OAT groups were derived from OAT registries, while the population size of PWID never on OAT was derived from national estimates, and adjusted based on our sample selection of PWID (Berleva et al., 2012). Weighted multivariable logistic regressions were used to analyze the primary outcome of preferring XR-NTX compared to all other types of MAT. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

2.4. Ethical Oversight

The study was approved by institutional review boards at Yale University and the Gromashevskiy Institute at the National Academy of Medical Sciences.

3. Results

Among the 1,613 PWID recruited, 434 (26.9%) were currently, 279 (17.3%) were previously, and 900 (55.8%) were never on OAT. Though presented elsewhere (Makarenko et al., 2016; Makarenko et al., 2017b), the three PWID groups differed significantly on a number of characteristics, including current and previous OAT clients being significantly older and more likely to have engaged in prior addiction treatment and undergone detox previously, been officially registered as a drug user, have lower injection frequency and injected longer, have lower addiction severity and depressive symptoms, and more likely to have an alcohol use disorder and be HIV-infected.

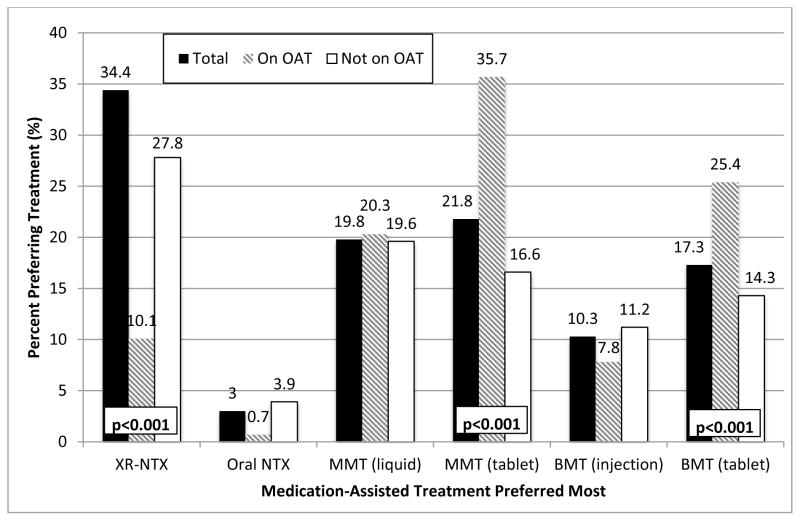

Figure 1 depicts the stated preferences for various types of MAT. There were 449 (27.8%) participants who preferred and would initiate XR-NTX over any other pharmacological treatment for opioid use disorders. Overall, XR-NTX was the most preferred treatment option for OUDs (27.8%), followed by either tablet (21.8%) and liquid (19.8%) formulations of methadone; however, combining any formulation of methadone (41.6%) was the most preferred option. Among current OAT patients, however, methadone (60%), either as liquid (20.3%) or tablet (35.7%), was the most preferred option, while those not on OAT overwhelmingly preferred XR-NTX (34.4%). Significant comparisons of type of preferred MAT for those on and not on OAT included for XR-NTX (10.1% vs 34.4%; p<0.001), methadone tablets (35.7% vs 16.6%; p<0.001) and buprenorphine tablets (25.4% vs 14.3%; p<0.001). Independent correlates of willingness to initiate XR-NTX included geographical location (living in Mykolaiv or Dnipro), never having been prescribed OAT previously, shorter duration of drug injection, and more favorable attitudes towards OAT (Table 2).

Figure 1. Preference for various available medication-assisted therapies to treat opioid use disorders, stratified by experience with opioid agonist therapies (N=1,613)*.

XR-NTX: extended-release naltrexone; NTX: naltrexone; MMT: methadone maintenance therapy; BMT: buprenorphine maintenance therapy. P-value indicates a significant difference between those currently or not currently on an opioid agonist treatment. Unless specified, p-value is not significant comparing participants on and not on opioid agonist treatments.

* Question: «If you were able to choose a medication-assisted therapy as a treatment for your opioid problem, which of the following would you choose?»

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants by treatment preference (XR-NTX vs. any other type of medication-assisted therapies), N=1,613

| Characteristic | Preferred XR-NTX | Bivariate Correlations | Multivariate Correlations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No N=1164 N (%) |

Yes N=449 N (%) |

uOR (95% C.I.) | P-value | aOR (95% C.I.) | P-value | |

| City | ||||||

| Kyiv | 331 (28.4) | 86 (19.2) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Odessa | 163 (14.0) | 52 (11.6) | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | 0.5082 | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | 0.6022 |

| Mykolaiv | 216 (18.6) | 128 (28.5) | 3.7 (2.4–5.8) | <0.0001 | 3.7 (2.3–6.1) | <0.0001 |

| Dnipro | 270 (23.2) | 98 (21.8) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 0.044 | 1.8 (1.1–2.9) | 0.0151 |

| Lviv | 184 (15.8) | 85 (18.9) | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 0.3205 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 0.2648 |

| Age – median (IQR) | 36 (30–42) | 34 (29–41) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.031 | – | – |

| Sex | – | |||||

| Male | 909 (78.1) | 324 (72.2) | Ref. | – | ||

| Female | 255 (21.9) | 125 (27.8) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 0.2226 | ||

| Registered as a drug user | – | – | ||||

| Yes | 700 (60.1) | 200 (44.5) | Ref. | |||

| No | 464 (39.9) | 249 (55.5) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.0558 | ||

| OAT experience | ||||||

| Currently on OAT | 390 (33.5) | 44 (9.8) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Previously on OAT | 204 (17.5) | 75 (16.7) | 2.9 (1.8–4.8) | <0.0001 | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 0.3592 |

| Never on OAT | 570 (49.0) | 330 (73.5) | 4.9 (3.4–7.1) | <0.0001 | 3.4 (2.1–5.4) | <0.0001 |

| Self-reported HIV status | ||||||

| Positive | 431 (37.0) | 142 (31.6) | Ref. | |||

| Negative | 491 (42.2) | 171 (38.1) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 0.2338 | – | – |

| Unknown | 242 (20.8) | 136 (30.3) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.1186 | ||

| Any previous drug treatment experience | ||||||

| Yes | 859 (73.8) | 269 (59.9) | Ref. | 0.3783 | – | – |

| No | 305 (26.2) | 180 (40.1) | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | |||

| Duration of injection drug use – median years (IQR) | 17 (11–24) | 15 (7–21) | 0.97 (0.96–0.99) | 0.0007 | 0.9 (0.9–0.98) | <0.0001 |

| Drug injection frequency (last 30 days) | ||||||

| > 20 days | 405 (34.8) | 204 (45.4) | Ref. | – | – | |

| ≤ 20 days | 759 (65.2) | 245 (54.6) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 0.4914 | ||

| Alcohol use disorder | ||||||

| No | 735 (63.1) | 239 (53.2) | Ref. | – | – | |

| Yes | 429 (36.9) | 210 (46.8) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 0.5597 | ||

| Drug Addiction Severity | ||||||

| Low | 89 (7.7%) | 30 (6.7%) | Ref. | – | – | |

| Moderate to severe | 1075 (92.3%) | 419 (93.3) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | 0.7798 | ||

| Previously incarcerated | ||||||

| Yes | 623 (53.5) | 215 (47.9) | Ref. | – | – | |

| No | 541 (46.5) | 234 (52.1) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 0.0824 | ||

| Composite positive attitudes toward OAT (0–9 scale) – median (IQR) | 7 (4–9) | 4 (0–7) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | <0.0001 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | <0.0001 |

| Composite negative attitudes toward OAT (0–6 scale) – median (IQR) | 5 (3–6) | 3 (2–5) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | <0.0001 | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | <0.0001 |

uOR: unadjusted odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; OAT: opioid agonist therapy (methadone or buprenorphine)

4. Discussion

To our knowledge this is the largest study to examine the preferences toward XR-NTX or any other pharmacological treatments among PWID with opioid use disorders in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. According to the diffusion of innovation theory, which examines market acceptability and uptake of new products like XR-NTX, uptake would typically be slow, but variable depending on efficacy, safety, convenience and cost relative to other options (Golder and Tellis, 2004; Klepper, 1996; Mahajan et al., 1991). In a country where attitudes toward OAT remain quite negative (Polonsky et al., 2016c), willingness to initiate XR-NTX was lower than reported elsewhere (28%), but is still a major stride given that treatment coverage for OUDs is extraordinarily low. Extended-release naltrexone is especially salient as the most preferred option by PWID who are not on OAT – the overwhelming majority of PWID in Ukraine. Assuming cost were not an issue and that sampling was generally random from five regions of Ukraine, this would suggest that coverage could increase 10-fold (current coverage is 2.7%) if PWID opted for XR-NTX because this treatment overcomes many previously identified scale-up barriers like daily supervised administration requirements and the need to register as a drug user, which is required by existing OAT programs. Whether this preference would remain as government regulations have recently changed in Ukraine that allows stable patients who want methadone or buprenorphine to receive it in primary care centers (Morozova et al., 2017b), or by purchase in pharmacies is currently not known, though pilot studies are underway. Importantly, XR-NTX would provide more options for patients to receive treatment and foster scale-up of evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorders. Findings here differ from PWID in high-income settings like Vancouver where 52% were willing to consider XR-NTX (2015) and similarly high among PWID with co-morbid opioid and alcohol use disorders transitioning from criminal justice settings (Di Paola et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2015; Springer et al., 2015; Springer et al., 2014).

Attitudes toward OAT were significantly correlated with willingness to initiate XR-NTX. OAT in this setting is not perceived as a pathway to “recovery” (Polonsky et al., 2016c) but instead, an opioid “substitution”, and the same may be true for XR-NTX since both are pharmacotherapies used to treat opioid use disorders. This finding is supported by a survey of professionals who perceived that either psychological counseling or religion were the most effective treatments for opioid use disorders, with OAT supported only by a quarter of clinicians (Polonsky et al., 2015). Abstinence-based treatment approaches linked to extensive psychological counseling (Elovich and Drucker, 2008) remain dogma and featured prominently by most recovery efforts in Ukraine. This view has pervaded the addiction treatment psyche of PWID, and may partially explain why XR-NTX, or OAT generally, is not viewed more favorably. Another explanation may be that OAT was introduced in the region as an HIV prevention strategy rather than as an effective treatment for addiction. OAT struggles to find its place in the “recovery” literature, although a new National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report found that OAT and recovery are not mutually exclusive (Amaro and Schwartz, 2016).

Russia’s continued influence on addiction treatment and especially OAT in Ukraine and throughout the region is pervasive and its unyielding ban on OAT has undermined OAT scale-up (Bojko et al., 2013; Cohen, 2010; Elovich and Drucker, 2008; Galeotti, 2016; Oakford, 2016; Samet, 2011). Russia does, however, support XR-NTX (Krupitsky et al., 2010a; Krupitsky et al., 2010b), which may partially explain why some PWID endorse XR-NTX (Galeotti, 2016; Oakford, 2016), especially among PWID who have never received OAT. In the absence of a change of policy toward OAT in Russia, strategies that simultaneously increase XR-NTX scale-up for those who might benefit from it would provide both patients and clinicians with more evidence-based options – but would require marked reductions in cost. Even though still prohibitive in terms of cost, the cost for each month of XR-NTX reduced from $600 to $150 since its introduction in Ukraine.

Official governmental registration as a “drug user” remains chief among the many barriers for PWID to receive treatment because registration stigmatizes patients (Morozova et al., 2017a), results in the loss of their driver’s license, restricts employment options and subjects them to police harassment (Bojko et al., 2015; Bojko et al., 2016b; Izenberg et al., 2013). XR-NTX may obviate this requirement because patients may now undergo supervised withdrawal using buprenorphine outside addiction treatment settings for patients who purchase buprenorphine and then initiated on XR-NTX without going through the official registration process.

Willingness to initiate XR-NTX in Ukraine may also be driven by limited or no availability of other forms of OAT. In this regard, Ukraine differs from Russia where any form of OAT is banned and only naltrexone-based therapies are allowed. The result of this ban, low coverage with HIV prevention strategies (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), 2016b) and the minimal coverage of XR-NTX in Russia contribute greatly to Russia being the source of over 80% of all new HIV infections in this region (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2016).

Of interest is that PWID in Mykolaiv and Dnipro, on average, were more interested in XR-NTX relative to PWID in other regions. Regional differences in HIV treatment (Zaller et al., 2015), drug injection patterns (Zaller et al., 2015), addiction treatment and attitudes toward OAT (Makarenko et al., 2017a; Makarenko et al., 2016) are well-described in Ukraine. For example, PWID in Kyiv and Lviv were more willing to enroll on methadone or buprenorphine compared to those in Dnipro, Mykolaiv and Odessa (Makarenko et al., 2016). As new regulations in Ukraine now allow for patients to purchase OAT outside of nationally-funded programs, PWID in Dnipro and Lviv were significantly more likely to be willing to pay for their OAT (Makarenko et al., 2017a). To better understand our current findings, addiction specialists in Mykolaiv and Dnipro have successfully enrolled the highest number of OAT patients and coverage levels in the country (Ukraine Ministry of Health, 2016), supporting the diffusion of innovation theory’s (Mahajan et al., 1991) suggestion that local expertise may differ and that experts who are more open to innovation and change can create new opportunities like introducing new treatments such as XR-NTX. As OAT expands within a community, it should shift attitudes toward drug treatment, and specifically evidence-based treatments, from a moral to a scientific paradigm among the public and professionals.

Decisions about treatment, including MAT for opioid use disorders, are often complex and sensitive to patient preferences (Uebelacker et al., 2016) where there are objective trade-offs between the documented treatment benefits and risks (e.g., stigma, discrimination, convenience and adverse side effects). Given its novelty, in order to improve patients’ ability to understand the safety and efficacy of XR-NTX, informed decision aids (Barry and Edgman-Levitan 2012; Godolphin, 2009; Weinstein, 2005; Weinstein et al., 2007) that provide accurate information about the range of MAT options available for treating opioid use disorders are needed. Shared decision aids that facilitate discussions between providers and patients would extend this practice so that a balanced discussion and therapeutic alliance would further engage patients and clinicians in treatment (Elwyn et al., 2012; Elwyn et al., 2016). Simultaneous education of PWID and their clinicians about the unique attributes about various MAT options may influence the decision to initiate and persist on XR-NTX given the array of available treatment options.

Recommended steps to improve knowledge about XR-NTX for providers and participants in MAT programs in Ukraine and elsewhere include: 1) accurate education about benefits and consequences of XR-NTX; 2) need for humane supervised withdrawal from opioids (rather than inpatient “detox as cold turkey”), perhaps in an outpatient setting using buprenorphine, prior to initiating XR-NTX; 3) cost reductions to make XR-NTX more affordable; 4) expanded training of clinicians to manage PWID treated with XR-NTX; and 5) treatment strategies that optimize retention to avoid overdose when injections are missed. As newer MAT become available, such as 3-month naltrexone (Goonoo et al., 2014) or even longer-acting buprenorphine implants that are effective over a 6-month period (Ling et al., 2010), patient preferences may influence treatment uptake.

5. Limitations

Despite the large sample size and inclusion of PWID throughout many regions of Ukraine, findings here must be interpreted based on known limitations of cross-sectional studies and that stated preferences for treatment were not linked to actual treatment enrollment due to XR-NTX being expensive and not being widely available throughout Ukraine. Though cost is a concern, recent data from Ukraine suggest that PWID would be willing to pay for treatment outside existing addiction specialty treatment settings (Makarenko et al., 2017b). Future studies should examine whether willingness to initiate treatment with XR-NTX is linked to both treatment imitation and retention.

6. Conclusions

Understanding patient preferences, especially as new MAT for treating opioid use disorders emerge, will provide patients with more evidence-based options to improve health and prevent HIV transmission. XR-NTX provides a new and more convenient opportunity than existing OAT options until both personal and structural factors are overcome. Incorporating informed and/or shared decision aids that compare the benefits of available and newly emerging MAT options may greatly enhance MAT scale-up and HIV prevention efforts. Once patients and providers fully understand the benefits and consequences of XR-NTX relative to other treatment options, it may emerge as a viable treatment option to advance addiction treatment and HIV prevention efforts in settings where HIV is concentrated in PWID.

Highlights.

Methadone or buprenorphine maintenance are available in Ukraine, yet few receive it

Moral biases limit the acceptance of medication-assisted treatment (MAT)

Extended-release naltrexone injected monthly may overcome barriers to scaling up MAT

People who inject drugs who have never been on MAT are more likely to prefer Extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX)

XR-NTX provides a new opportunity for treatment

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse for research (R01 DA029910 and R01 DA033679) and career development (K24 DA017072 for FLA, K01 DA037826 for AZ, and K02 DA032322 for SAS) as well as the Global Health Equity Scholars Program funded by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Research Training Grant R25 TW009338 for MJB and MP).

the authors would like to thank the local research assistants for their diligent recruitment efforts and stringent data collection and the people who inject drugs in Ukraine who were willing to share their time and perceptions about a novel pharmacotherapeutic treatment for opioid use disorders.

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript submitted for publication. FLA and SAS designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. RM and FLA prepared the manuscript. IM, AM, AZ, MP conducted the analysis and reviewed the manuscript. LM, SF, SD contributed scientific expertise and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

None for all authors except FLA

FLA Speakers bureau fee: Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Gilead Sciences, Practice Point Communications Institutional grant support: NIH, NIDA, NIAAA, Gilead Foundation, Merck Clinical Trials, SAMHSA, HRSA

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahamad K, Milloy MJ, Nguyen P, Uhlmann S, Johnson C, Korthuis TP, Kerr T, Wood E. Factors associated with willingness to take extended release naltrexone among injection drug users. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10:12. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanis-Hirsch K, Croff R, Ford JH, II, Johnson K, Chalk M, Schmidt L, McCarty D. Extended-release naltrexone: A qualitative analysis of barriers to routine use. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;62:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alistar SS, Owens DK, Brandeau ML. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of expanding harm reduction and antiretroviral therapy in a mixed HIV epidemic: A modeling analysis for Ukraine. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Azbel L, Stone J, Brooks-Pollock E, Smyrnov P, Dvoriak S, Taxman FS, El-Bassel N, Martin NK, Booth R, Stover H, Dolan K, Vickerman P. The perfect storm: Incarceration and the high-risk environment perpetuating transmission of HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Lancet. 2016;388:1228–1248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30856-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376:367–387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Schwartz L. National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine, editor . Measuring Recovery from Substance Use and Mental Disorder. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Azbel L, Wickersham JA, Grishaev Y, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Burden of infectious diseases, substance use disorders, and mental illness among Ukrainian prisoners transitioning to the community. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making — The pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berleva G, Dumchev K, Kasianchuk M, Nikolko M, Saliuk T, Shvab I, Yaremenko O. Estimation of the Size of Populations Most-at-Risk for HIV Infection in Ukraine. ICF International Alliance in Ukraine; Kiev, Ukraine: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bojko MJ, Dvoriak S, Altice FL. At the crossroads: HIV prevention and treatment for people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Addiction. 2013;108:1697–1699. doi: 10.1111/add.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojko MJ, Mazhnaya A, Makarenko I, Marcus R, Dvoriak S, Islam Z, Altice FL. “Bureaucracy and Beliefs”: Assessing the barriers to accessing opioid substitution therapy by people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Drugs Edu Prev Policy. 2015;22:255–262. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2015.1016397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojko MJ, Mazhnaya A, Marcus R, Makarencko I, Fillipovich S, Islam Z, Dvoriak S, Altice FL. The future of opioid agonist therapies in Ukraine: A qualitative assessment of multilevel barriers and ways forward to promote retention in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;66:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce RD, Dvoryak S, Sylla L, Altice FL. HIV treatment access and scale-up for delivery of opiate substitution therapy with buprenorphine for IDUs in Ukraine--programme description and policy implications. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:326–328. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Law enforcement and drug treatment: a culture clash. Science. 2010;329:169. doi: 10.1126/science.329.5988.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins SJ, Radfar SR, Crèvecoeur-MacPhail D, Ang A, Darfler K, Rawson RA. Predictors of continued use of extended-released naltrexone (XR-NTX) for opioid-dependence: An analysis of heroin and non-heroin opioid users in Los Angeles county. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;63:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Mathers BM, Wirtz AL, Wolfe D, Kamarulzaman A, Carrieri MP, Strathdee SA, Malinowska-Sempruch K, Kazatchkine M, Beyrer C. What has been achieved in HIV prevention, treatment and care for people who inject drugs, 2010–2012? A review of the six highest burden countries. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paola A, Lincoln T, Skiest DJ, Desabrais M, Altice FL, Springer SA. Design and methods of a double blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of extended-release naltrexone for HIV-infected, opioid dependent prisoners and jail detainees who are transitioning to the community. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;39:256–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A, Perales N, Semeryk O, Balakireva O, Aleksandrina T, Ieshchenko O, Zelenska M. Futures Group, H.P.P, editor. Lives on the Line: Funding Needs and Impacts of Ukraine’s National HIV/AIDS Program, 2014–2018. Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elovich R, Drucker E. On drug treatment and social control: Russian narcology’s great leap backwards. Harm Reduct J. 2008;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, Cording E, Tomson D, Dodd C, Rollnick S, Edwards A, Barry M. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Frosch DL, Kobrin S. Implementing shared decision-making: Consider all the consequences. Impl Sci. 2016;11:114. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0480-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe. HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe 2015. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; Stockholm, Sweden: 2016. [Accessed on December 13, 2016]. at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/324370/HIV-AIDS-surveillance-Europe-322015.pdf?ua=324371. [Google Scholar]

- Galeotti M. Narcotics and Nationalism: Russian Drug Policies and Futures. In: Brookings FPa., editor. Improving Global Drug Policy: Comparative Perspectives and UNGASS 2016. New York University Center for Global Affairs; New York: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin DR, Ross HE, Skinner HA. Diagnostic validity of the drug abuse screening test in the assessment of DSM-III drug disorders. Br J Addict. 1989;84:301–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godolphin W. Shared decision-making. Healthcare Q. 2009;12:e186–e190. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.20947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder PN, Tellis GJ. Growing, growing, gone: cascades, diffusion, and turning points in the product life cycle. Market Sci. 2004;23:207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Goonoo N, Bhaw-Luximon A, Ujoodha R, Jhugroo A, Hulse GK, Jhurry D. Naltrexone: A review of existing sustained drug delivery systems and emerging nano-based systems. J Control Release. 2014;183:154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izenberg JM, Bachireddy C, Soule M, Kiriazova T, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. High rates of police detention among recently released HIV-infected prisoners in Ukraine: Implications for health outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Global AIDS Update 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: 2016a. [Accessed on May 28, 2016]. at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-AIDS-update-2016_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Prevention Gap Report. Geneva, Switzerland: 2016b. [Accessed on July 14, 2016]. at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2016-prevention-gap-report_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kiriazova TK, Postnov OV, Perehinets IB, Neduzhko OO. Association of injecting drug use and late enrolment in HIV medical care in Odessa Region, Ukraine. HIV Med. 2013;14(Suppl 3):38–41. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepper S. Entry, exit, growth, and innovation over the product life cycle. Am Econ Rev. 1996;86:562–583. [Google Scholar]

- Krupitsky EM, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Efficacy and Safety of Extended Release Naltrexone (NTX-XR) for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence. American Psychiatric Association; New Orleans, LA: 2010a. [Google Scholar]

- Krupitsky EM, Zvartau E, Woody G. Use of naltrexone to treat opioid addiction in a country in which methadone and buprenorphine are not available. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010b;12:448–453. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0135-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsa O, Marcus R, Bojko MJ, Zelenev A, Mazhnaya A, Dvoriak S, Filippovych S, Altice FL. Factors associated with physical and sexual violence by police among people who inject drugs in Ukraine: Implications for retention on opioid agonist therapy. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19:20897. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.4.20897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrinson P, Ali R, Buavirat A, Chiamwongpaet S, Dvoryak S, Habrat B, Jie S, Mardiati R, Mokri A, Moskalewicz J, Newcombe D, Poznyak V, Subata E, Uchtenhagen A, Utami DS, Vial R, Zhao C. Key findings from the WHO collaborative study on substitution therapy for opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS. Addiction. 2008;103:1484–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Friedmann PD, Kinlock TW, Nunes EV, Boney TY, Hoskinson RA, Jr, Wilson D, McDonald R, Rotrosen J, Gourevitch MN, Gordon M, Fishman M, Chen DT, Bonnie RJ, Cornish JW, Murphy SM, O’Brien CP. Extended-release naltrexone to prevent opioid relapse in criminal justice offenders. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1232–1242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, McDonald R, Grossman E, McNeely J, Laska E, Rotrosen J, Gourevitch MN. Opioid treatment at release from jail using extended-release naltrexone: A pilot proof-of-concept randomized effectiveness trial. Addiction. 2015;110:1008–1014. doi: 10.1111/add.12894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Casadonte P, Bigelow G, et al. Buprenorphine implants for treatment of opioid dependence: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1576–1583. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan V, Muller E, Bass F. New product diffusion models in marketing: A review and directions for research. In: NN, Grubler A, editors. Diffusion of technologies and social behavior. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH; New York: 1991. pp. 125–177. [Google Scholar]

- Makarenko I, Mazhnaya A, Marcus R, Bojko MJ, Madden L, Filippovich S, Dvoriak S, Altice FL. Willingness to pay for opioid agonist treatment among opioid dependent people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Int J Drug Policy. 2017a;45:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarenko I, Mazhnaya A, Polonsky M, Marcus R, Bojko MJ, Filippovych S, Springer S, Dvoriak S, Altice FL. Determinants of willingness to enroll in opioid agonist treatment among opioid dependent people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarenko J, Pykalo I, Mazhnaya A, Marcus R, Fillipovich S, Dvoriak S, Springer SA, Altice FL. Treating opioid dependence with extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) in Ukraine: Feasibility and three-month outcomes. Addiction. 2017b doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.05.008. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazhnaya A, Andreeva TI, Samuels S, DeHovitz J, Salyuk T, McNutt LA. The potential for bridging: HIV status awareness and risky sexual behaviour of injection drug users who have non-injecting permanent partners in Ukraine. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18825. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazhnaya A, Bojko MJ, Marcus R, Filippovych S, Islam Z, Dvoriak S, Altice FL. In their own voices: breaking the vicious cycle of addiction, treatment and criminal justice among people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Drugs Edu Prev Policy. 2016;23:163–175. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2015.1127327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA, Dvoryak S, Reisner SL, Needle R, Woody G. “We fear the police, and the police fear us”: Structural and individual barriers and facilitators to HIV medication adherence among injection drug users in Kiev, Ukraine. AIDS Care. 2010;22:1305–1313. doi: 10.1080/09540121003758515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova O, Dvoriak S, Pykalo I, Altice FL. Primary healthcare-based integrated care with opioid agonist treatment: First experience from Ukraine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakford S. [accessed on April 19, 2016];How Russia Became the New Global Leader in the War on Drugs. 2016 http://en.rylkov-fond.org/blog/uncategorized/press-about-us/vice/

- Polonsky M, Azbel L, Wegman MP, Izenberg JM, Bachireddy C, Wickersham JA, Dvoriak S, Altice FL. Pre-incarceration police harassment, drug addiction and HIV risk behaviours among prisoners in Kyrgyzstan and Azerbaijan: Results from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016a;19:20880. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.4.20880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky M, Azbel L, Wickersham JA, Marcus R, Doltu S, Grishaev E, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Accessing methadone within Moldovan prisons: Prejudice and myths amplified by peers. Int J Drug Policy. 2016b;29:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky M, Azbel L, Wickersham JA, Taxman FS, Grishaev E, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Challenges to implementing opioid substitution therapy in Ukrainian prisons: Personnel attitudes toward addiction, treatment, and people with HIV/AIDS. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky M, Rozanova J, Azbel L, Bachireddy C, Izenberg J, Kiriazova T, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Attitudes toward addiction, methadone treatment, and recovery among HIV-infected Ukrainian prisoners who inject drugs: Incarceration effects and exploration of mediators. AIDS Behav. 2016c;20:2950–2960. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1375-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure 1977 [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH. Russia and human immunodeficiency virus--beyond crime and punishment. Addiction. 2011;106:1883–1885. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Altice FL, Brown SE, Di Paola A. Correlates of retention on extended-release naltrexone among persons living with HIV infection transitioning to the community from the criminal justice system. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;157:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Altice FL, Herme M, Di Paola A. Design and methods of a double blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of extended-release naltrexone for alcohol dependent and hazardous drinking prisoners with HIV who are transitioning to the community. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;37:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Bailey G, Herman D, Anderson B, Stein M. Patients’ beliefs about medications are associated with stated preference for methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone, or no medication-assisted therapy following inpatient opioid detoxification. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;66:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukraine Ministry of Health. Report on Socially Dangerous Diseases in Ukraine, 2016. Kyiv, Ukraine: 2016. [Accessed on March 9, 2016]. at: www.moz.gov.ua. [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein JN. Partnership: doctor and patient: Advocacy for informed choice vs. informed consent. Spine. 2005;30:269–272. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000155479.88200.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein JN, Clay K, Morgan TS. Informed patient choice: patient-centered valuing of surgical risks and benefits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:726–730. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: A review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet. 2010;376:355–366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60832-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaller N, Mazhnaya A, Larney S, Islam Z, Shost A, Prokhorova T, Rybak N, Flanigan T. Geographic variability in HIV and injection drug use in Ukraine: Implications for integration and expansion of drug treatment and HIV care. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]