Abstract

Introduction

Pirfenidone film-coated tablets were developed to offer an alternative to the marketed capsule formulation. This study assessed the bioequivalence of the tablet and capsule formulations under fed and fasted states.

Methods

A Phase I, open-label, randomized, four-treatment-period, four-sequence, crossover pharmacokinetics study (NCT02525484) was conducted. Each subject received an 801-mg single dose of pirfenidone as three 267-mg capsules or one 801-mg tablet under fasted and fed conditions. Pirfenidone plasma C max, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ were used to assess bioequivalence.

Results

Forty-four subjects were randomized to treatment. The 801-mg tablet in the fasted state met bioequivalence criteria [90% confidence intervals (CI) 80.00–125.00%] for the GLSM ratios of natural log-transformed C max, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞. Under fed conditions, the 801-mg tablet met the bioequivalence criteria for AUC0–t and AUC0–∞, but slightly exceeded the bioequivalence criteria for the C max (90% CI of 108.26–125.60%). The tablet C max was approximately 17% higher than that of the capsules. In the fed state, the tablet C max, and both AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ were reduced by 39% and 17%, respectively, relative to the fasted state. The tablet and capsules had acceptable tolerability profiles.

Conclusions

The pirfenidone 801-mg tablet met bioequivalence criteria when compared with three 267-mg capsules in the fasted state. The tablet C max was slightly higher relative to capsules in the fed state, but this is not expected to have a clinically meaningful impact on the benefit–risk profile of pirfenidone.

Funding

This work was supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0594-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Bioequivalence, Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Pharmacokinetics, Pirfenidone, Respiratory

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a debilitating, progressive and fatal lung disease [1–3]. Pirfenidone (as a 267-mg capsule) is approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and is recommended in international treatment guidelines for the treatment of IPF in the majority of patients [2, 4, 5].

Although the mechanism of action has not been fully established, pirfenidone is an antifibrotic agent that affects multiple biological pathways in vivo. Pirfenidone attenuates fibroblast proliferation and production of fibrosis-associated proteins and cytokines, and decreases biosynthesis and accumulation of extracellular matrix in response to cytokine growth factors [6–8].

Clinical studies in patients with IPF have shown that pirfenidone reduced the decline in forced vital capacity and the risk of all-cause mortality versus placebo at 1 year [9, 10]. Pirfenidone is generally well tolerated; however, gastrointestinal and skin-related adverse events (AEs) can affect tolerability in some patients, particularly within the first 6 months of treatment [11, 12].

Clinical pharmacokinetic (PK) studies have demonstrated that, after oral administration of pirfenidone in various oral formulations, peak plasma pirfenidone concentration (C max) and area under the plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC) are significantly higher in a fasted versus a fed state [13–15]. The observed reduction in C max in the fed state is of clinical benefit as pirfenidone-related side effects were associated with C max [14, 15]. Therefore, prescribing information recommends taking pirfenidone with food [4, 5].

Gradual dose titration on initiation of pirfenidone can help with the management of AEs and prevent treatment discontinuation [11, 12]. Currently, the pirfenidone capsule is available as a 267-mg capsule and the flexibility offered by the capsule formulation is key to facilitating tailored dosing until patients are established on a stable dose of pirfenidone. The recommended starting dose is 1 × 267-mg capsule three times daily (tid) for 1 week, followed by 2 × 267-mg capsules tid for 1 week, followed by the maintenance dosage of 3 × 267-mg capsules tid [5, 11]. If AEs occur during pirfenidone treatment, temporary dose reduction followed by re-escalation can help to resolve AEs [11].

Once patients are on a stable maintenance dose of 2403 mg/day, they may benefit from having fewer pills to take daily. This could improve medication adherence, which is defined as the degree to which patients follow recommendations on the timing, dosage and frequency of their medications [16]. Poor adherence may be associated with worse health outcomes [17–20] and the prescribed number of dose units of medication daily may be an important factor in influencing adherence, with an increasing number of doses associated with poorer adherence [20–22].

Pirfenidone film-coated 801-mg tablets were developed to provide patients who are tolerating the recommended daily maintenance dose with an alternative to the 267-mg capsule formation. The reduced pill burden of taking 1 × 801-mg tablet tid has the potential to increase adherence in these patients.

The aim of this study was to assess the bioequivalence of pirfenidone after a single-dose oral administration of 1 × 801-mg tablet compared with a single-dose of 3 × 267-mg capsules under fasted and fed states.

Methods

Study Design

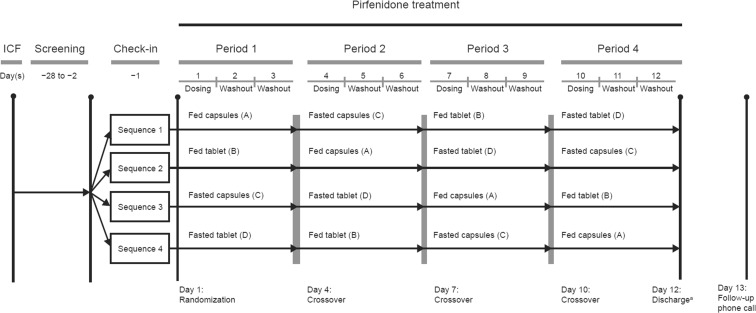

This single-dose, Phase I, open-label, randomized, four-treatment-period, four-sequence, crossover PK study (NCT02525484) was designed to determine the bioequivalence of pirfenidone when administered via a tablet versus a capsule formulation in the fed and fasted states (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study design. ICF informed consent, PK pharmacokinetic

a Discharge after completion of PK blood draws and assessments

Following a screening period of up to 28 days, healthy volunteers aged 18–55 years were randomized to one of four treatment sequences, during which the following treatments were administered as single oral doses (i.e. there was no dose titration as is normally used in patients with IPF; Fig. 1):

Treatment A = pirfenidone 3 × 267-mg capsules in the fed state.

Treatment B = pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet in the fed state.

Treatment C = pirfenidone 3 × 267-mg capsules in the fasted state.

Treatment D = pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet in the fasted state.

Knowledge of the dosage form (i.e. tablet or capsule) would not influence the PK assessment; hence, the study was not blinded to simplify the study conduct. However, persons involved in analyzing the PK data were blinded as to whether the sample was following tablet or capsule administration until the PK parameters were determined. A 4 × 4 Williams study design was used, with the four possible treatment sequences being ACBD, BADC, CDAB and DBCA (Fig. 1). Subjects remained at the clinic for 12 nights, from the day before the first dose of the study drug until 48 h after the last dose of the study drug following completion of safety assessments. Study drug was administered on Days 1, 4, 7 and 10, with a 72-h washout period between the administration of doses to ensure sufficient washout based on a half-life of 2–3 h (Fig. 1).

Under fed conditions, pirfenidone was administered after a high-fat and high-calorie meal, consumed after an overnight fast as per guidance from global regulatory agencies [23, 24]. Each high-fat breakfast consisted of approximately 840 calories, provided from 32 g of protein, 54 g of fat, and 57 g of carbohydrate. A typical breakfast included two fried eggs, two strips of bacon, two slices of toast, two pats of butter, four ounces of hash brown potatoes, and eight fluid ounces of whole milk. Under fasting conditions, pirfenidone was administered after an overnight fast of at least 10 consecutive hours.

To be eligible for participation in the study, subjects were required to be non-smokers, in good health, and with no significant medical history (in the opinion of the investigator). Participants also agreed to abstain from alcohol, caffeine, cruciferous vegetables and strenuous exercise for the duration of the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant local legal and regulatory requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before any study procedures were performed.

Sample Collection

Blood samples (4 mL) for the harvesting of plasma to determine plasma pirfenidone concentrations and PK calculations were drawn in EDTA vacutainer tubes on Days 1, 4, 7 and 10: up to 3 h pre-dose and 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16 and 24 h post-dose.

Bioanalytical Methods

A validated liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometric (LC–MS/MS) method was used to determine the concentration of pirfenidone in K2EDTA-treated plasma samples. Pirfenidone and the deuterium-labeled internal standard, pirfenidone-d5, were extracted from plasma, by means of supported liquid extraction. The LC–MS/MS analysis was carried out with a Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA) Gemini® C18 column on a Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) Prominence® HPLC system coupled with a Sciex (Framingham, MA, USA) API 4000™ triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Pirfenidone concentrations were calculated using a 1/x 2 weighted linear regression over a range from 5.00 to 3000 ng/mL. This method offered acceptable accuracy and precision. Validation methods confirmed that study samples with a pirfenidone concentration above 3000 ng/mL could be measured following dilution, with a dilution quality control sample of 50,000 ng/mL accurately measured after a 100-fold dilution with blank human plasma. There was no evidence of carryover that could adversely affect the quantitation of pirfenidone.

PK and Bioequivalence Analyses

Primary PK parameters in this study included the observed maximum plasma concentration (C max), area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to the time of the last quantifiable concentration (AUC0–t) and AUC from zero extrapolated to infinity (AUC0–∞.). Secondary PK parameters included observed time to reach peak concentration (t max), and elimination half-life (t1/2). PK parameters for pirfenidone were estimated from individual plasma concentration versus time profiles using a non-compartmental approach with Phoenix® WinNonlin® 6.3 (Certara USA, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Bioequivalence between the test treatment (1 × 801-mg pirfenidone tablet) and the reference treatment (3 × 267-mg pirfenidone capsules) was assessed by calculating two-sided 90% confidence intervals (CIs) for the geometric least-squares means (GLSM) ratio between the two treatments for both the fed and fasted states. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the natural log-transformed primary PK measurements: C max, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞. The 90% CIs of the GLSM ratio of the test treatment to the reference treatment were calculated by taking the anti-log of the corresponding 90% CIs for the differences between the means on the log scale. Bioequivalence was established if the 90% CI for the ratio was within bioequivalence limits of 80.00% to 125.00% [23, 24].

Power calculations indicated that a total of 36 subjects would provide 85% power to conclude bioequivalence if the true ratio between the pirfenidone capsule and tablet was 0.95 to 1.05 and the intra-subject coefficient of variation was 0.26. The intra-subject coefficient of variation value was selected based on the largest value reported in a previous PK study of the pirfenidone capsule formulation [14]. To ensure that at least 36 subjects would complete all study periods with adequate PK data, 44 subjects were enrolled in the study.

Safety Evaluation

All AEs (including those leading to treatment discontinuation and of special interest) that occurred on or after the first dose of study medication were recorded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Version 18.0 and listed by dosing condition. Changes from baseline in laboratory parameters and vital signs were also recorded [please refer to the online supplement for details]. A graphical examination of the exposure–response relationship was conducted to explore a potential relationship between drug exposure and the occurrence of AEs.

Results

Subjects

Of 97 subjects screened for inclusion, a total of 44 subjects were randomized to one of the four treatment sequences (Fig. 1). All subjects completed treatment and had blood samples collected at a minimum of 10 time points per treatment period, with at least one sample ≥16 h post-dose. One subject was excluded from the PK analysis for all treatments due to emesis following administration of pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet in the fed state and pirfenidone 3 × 267-mg capsules in the fasted state. Another subject experienced emesis following administration of pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet in the fasted state and was excluded from the PK analyses in the fasted state. Therefore, a total of 43 subjects were included in the PK population in the fed state, and 42 subjects were included in the PK population in the fasted state. All 44 subjects were included in the safety population. Subject demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of subject demographics at baseline

| Treatment sequencea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACBD n = 11 | BADC n = 11 | CDAB n = 11 | DBCA n = 11 | Total n = 44 | |

| Median (min, max) age, years | 33.0 (20, 53) | 28.0 (21, 49) | 41.0 (25, 54) | 38.0 (20, 50) | 33.0 (20, 54) |

| Male, n (%) | 5 (45.5) | 8 (72.7) | 9 (81.8) | 6 (54.5) | 28 (63.6) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 6 (54.5) | 6 (54.5) | 5 (45.5) | 7 (63.6) | 24 (54.5) |

| Black or African American | 5 (45.5) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (36.4) | 3 (27.3) | 17 (38.6) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (6.8) |

| Mean (SD) weight (kg) | 73.9 (13.0) | 71.2 (13.4) | 85.3 (14.1) | 77.8 (11.0) | 77.0 (13.6) |

| Mean (SD) height (cm) | 168.6 (7.1) | 168.8 (8.4) | 177.4 (11.4) | 170.0 (10.3) | 171.2 (9.8) |

| Mean (SD) BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 (3.3) | 24.9 (3.7) | 26.9 (2.3) | 26.9 (2.9) | 26.1 (3.1) |

BMI body mass index, SD standard deviation

aTreatment A = 3 × 267-mg capsules in the fed state; treatment B = 1 × 801-mg tablet in the fed state; treatment C = 3 × 267-mg capsules in the fasted state; treatment D = 1 × 801-mg tablet in the fasted state

PK Analyses

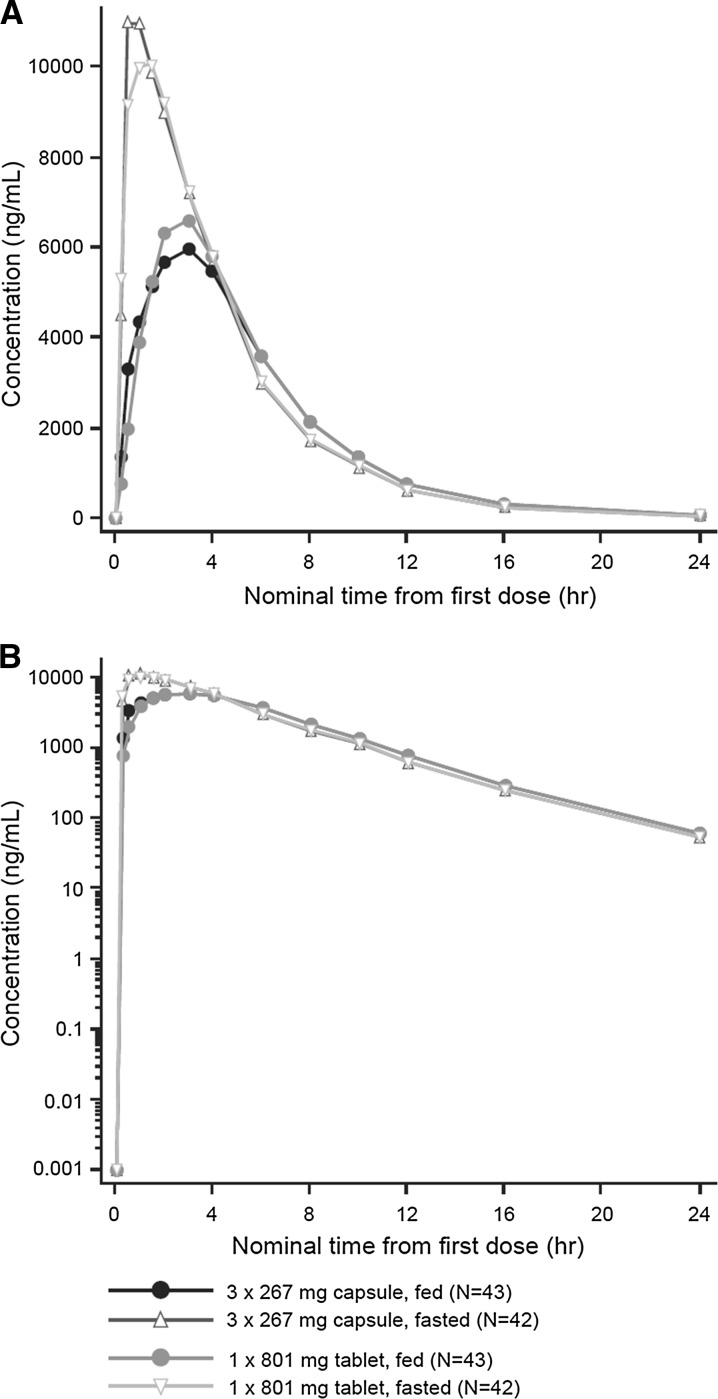

In the fasted state, pirfenidone PK, measured using the geometric mean AUC0–t, AUC0–∞, and C max, was similar between the tablet and capsules (Table 2). Mean pirfenidone plasma concentration–time profiles stratified by treatment are presented in Fig. 2. Median t max were similar between the tablet and capsules (Table 2).

Table 2.

PK parameters of pirfenidone following single-dose administration in the fed and fasted states

| PK parameter | Geometric mean (CV%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fed state (n = 43) | Fasted state (n = 42) | |||

| 3 × 267-mg capsules | 1 × 801-mg tablet | 3 × 267-mg capsules | 1 × 801-mg tablet | |

| C max (ng/mL) | 6560 (25.5) | 7640 (27.9) | 12,500 (27.9) | 12,600 (32.8) |

| AUC0–t (ng h/mL) | 39,500 (36.6) | 40,600 (35.0) | 49,500 (34.5) | 49,200 (35.1) |

| AUC0–∞ (ng h/mL) | 39,800 (37.0) | 40,900 (35.5) | 49,700 (34.9) | 49,400 (35.5) |

| t max (h)a | 3.00 (0.50, 6.00) | 2.05 (1.00, 6.00) | 0.75 (0.25, 2.00) | 1.00 (0.25, 3.00) |

| t 1/2 (h) | 2.75 (0.585) | 2.74 (0.579) | 2.77 (0.589) | 2.77 (0.571) |

AUC 0–∞ area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to infinity, AUC 0–t area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to the time of the last quantifiable concentration, C max peak plasma concentration, CV coefficient of variation, PK pharmacokinetic, t 1/2 terminal elimination half-life, t max time to peak plasma concentration

aMedian (minimum, maximum)

Fig. 2.

Mean plasma concentrationa versus time profiles with a linear and b semi-logarithmic scales. Plasma concentration values below limit of quantitation (BLOQ) were set to zero except when a BLOQ fell between two quantifiable values, in which case it was treated as missing data. One subject who was fasted and fed and one subject who was fasted only were excluded from descriptive statistics calculations because of vomiting within 6 h of dosing

a Mean concentration calculated from individual plasma concentration at the same time point

In the fed state, pirfenidone PK, as measured using the geometric mean AUC0–t and AUC0–∞, was similar between the pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet and the pirfenidone 3 × 267-mg capsules (Table 2). The geometric mean C max for the pirfenidone tablet was approximately 17% higher compared with the capsules [geometric mean (% coefficient of variation) = 7640 (27.9) vs. 6560 (25.5) ng/mL, respectively) (Table 2). Median t max was approximately 1 h shorter with the tablet than the capsules [median (min, max) = 2.05 (1.00, 6.00) vs. 3.00 (0.50, 6.00) h, respectively] (Table 2).

Bioequivalence Analysis

Under the fasted state, standard bioequivalence criteria were met for the GLSM ratios of natural log-transformed C max, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ for the pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet (Table 3). In the fed state, the 90% CI values for the GLSM ratios of natural log-transformed AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ met standard bioequivalence criteria (Table 3). The upper CI value for the natural log-transformed C max for the tablet slightly exceeded the standard bioequivalence criteria (by 0.6%), with a value of 125.60% compared with capsules (Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistical assessment of bioequivalence comparing pirfenidone 3 × 267-mg capsules and 1 × 801-mg tablet in the fed and fasted states

| PK parameter | Tablet vs. capsules, % GLSM ratio (90% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fed state (n = 43) | Fasted state (n = 42) | |

| C max (ng/mL) | 116.61 (108.26, 125.60) | 101.26 (94.41, 108.60) |

| AUC0–t (ng h/mL) | 103.06 (99.55, 106.69) | 99.63 (96.66, 102.69) |

| AUC0–∞ (ng h/mL) | 103.05 (99.54, 106.69) | 99.61 (96.64, 102.68) |

AUC 0–∞ area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to infinity, AUC 0–t area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to the time of the last quantifiable concentration, CI confidence interval, C max peak plasma concentration, GLSM geometric least-squares mean, PK pharmacokinetic

Food Effect

Following administration of the pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet, pirfenidone PK, as measured by AUC0–t and AUC0–∞, was approximately 17% lower in the fed state compared with the fasted state, with 90% CI values of 80.03–85.17% and 80.14–85.29%, respectively (Table 4). Following administration of the tablet, C max values were approximately 39% lower in the fed state compared with the fasted state, with 90% CI values of 55.82–65.67% (Table 4). The effect of food on pirfenidone PK was consistent between the tablet and capsule formulations.

Table 4.

Statistical assessment of bioequivalence comparing pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet in the fed and fasted states

| PK parameter | Feda vs. fastedb, % GLSM ratio (90% CI) |

|---|---|

| C max (ng/mL) | 60.54 (55.82, 65.67) |

| AUC0–t (ng h/mL) | 82.56 (80.03, 85.17) |

| AUC0–∞ (ng h/mL) | 82.68 (80.14, 85.29) |

AUC 0–∞ area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to infinity, AUC 0–t area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to the time of the last quantifiable concentration, CI confidence interval, C max peak plasma concentration, GLSM geometric least-squares mean, PK pharmacokinetic

a n = 43

b n = 42

Safety

A total of 22 (50.0%) subjects experienced at least one AE during the study. All AEs were rated as mild, and no serious AEs, deaths or AEs of special interest (cases of potential drug-induced liver injury and suspected transmission of an infectious agent by the study drug) were reported.

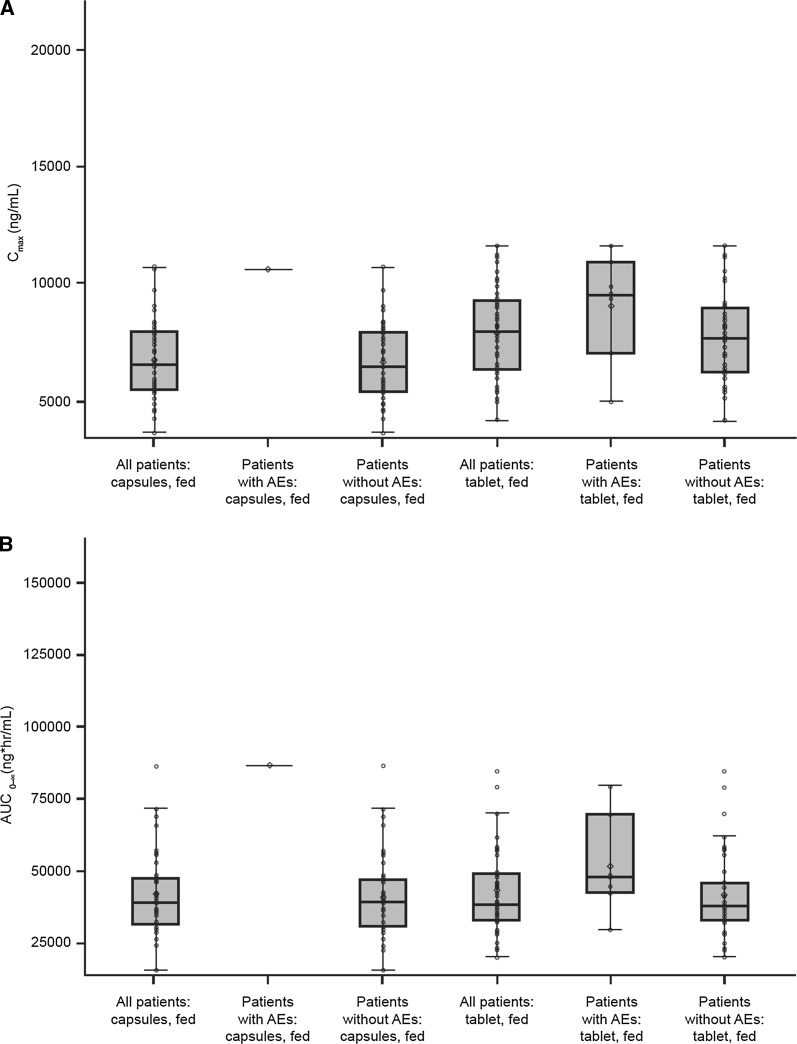

The most frequently (≥2) reported AEs were nausea [13 (29.5%)], dizziness [8 (18.2%)], headache [4 (9.1%)], constipation [4 (9.1%)], vomiting [2 (4.5%)] and dyspepsia [2 (4.5%)] (Table 5). A smaller proportion of subjects experienced AEs in the fed state versus the fasted state for both the tablet [7 (15.9%) vs. 16 (36.4%), respectively] and the capsules [1 (2.3%) vs. 14 (31.8%), respectively]. There was no apparent relationship between drug exposure and AEs based on a graphical examination of the exposure–response relationship (Fig. 3).

Table 5.

Adverse events

| n (%) | Fed state | Fasting state | Totala | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 × 267-mg capsules n = 44 | 1 × 801-mg tablet n = 44 | 3 × 267-mg capsules n = 44 | 1 × 801-mg tablet n = 44 | ||

| Nausea | 0 | 3 (6.8) | 8 (18.2) | 10 (22.7) | 13 (29.5) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 4 (9.1) | 6 (13.6) | 8 (18.2) |

| Headache | 0 | 2 (4.5) | 2 (4.5) | 3 (6.8) | 4 (9.1) |

| Constipation | 0 | 3 (6.8) | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 4 (9.1) |

| Vomiting | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.5) |

| Dyspepsia | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.5) |

| Oral paresthesia | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 1 (2.3) |

| Pollakiuria | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.3) |

| Vulvovaginal pruritus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) |

| Hot flush | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.3) |

aTotal counts are provided for the entire study with each subject counted only once

Fig. 3.

Distribution of a C max and b AUC0–∞ in the fed treatment period by subjects with and without AEs. Box and whisker plot defines the interquartile range; center line is the median; symbol is the mean; whiskers are the upper and lower limits of 1.5 times the interquartile range. Each subject is presented once within each treatment, for all subjects and by AE, reported or not. AE adverse event, AUC 0–∞, area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to infinity, C max peak plasma concentration

Discussion

The EMA bioequivalence guideline suggests that testing under fasted conditions is more sensitive in detecting differences between formulations than under fed conditions. However, the guidelines also suggest that bioequivalence studies should generally be conducted under fed conditions for products recommended for administration with food [23]. Similarly, the FDA recommends conducting bioequivalence studies under fasting and fed conditions for all orally administered immediate-release drug products [24].

In a previous PK study of the pirfenidone capsule formulation in healthy volunteers, the presence of food was associated with a reduction in C max value versus the fasted state, which was correlated with a reduction in gastrointestinal AEs [14]. This finding reflects clinical practice, with patients advised to take pirfenidone with or after a meal; therefore, this study also investigated the PK and bioequivalence of the pirfenidone tablet formulation under fed conditions. Consistent with the previous study, our results indicate that the presence of food reduces the rate and extent of pirfenidone absorption from the tablet formulation. A statistically significant reduction in pirfenidone C max was observed in the fed state versus the fasted state; whereas no statistically significant differences were observed for AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ measurements. The results of this study demonstrate that, in the fasted state, the pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet is bioequivalent to 3 × 267-mg capsules. In the fed state, the bioequivalence criteria were met based on AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ measurements, whereas the upper bound of the 90% CI values for C max (125.6%) was slightly outside the bioequivalence limits (by 0.6%).

The higher C max and shorter median t max with the tablet formulation compared with the capsules suggest that pirfenidone undergoes faster absorption following administration of the tablet compared with the capsules when food is present. It is possible that release of pirfenidone from the capsule at the site of absorption is delayed following a high-fat meal. One hypothesis is that multiple lighter capsules may float in the fed stomach, whereas a single heavier tablet may sink and mix more readily, ultimately delaying gastric emptying for the more buoyant capsules compared with the tablet [25].

The high-fat meal consumed during this study represented extreme dietary conditions, with subjects consuming approximately 800–1000 calories, of which 50% were from fat. EMA and FDA guidelines recommend conducting fed bioequivalence studies using a high-fat, high-calorie meal to provide the greatest effect on gastrointestinal physiology, thereby a maximum food effect on systemic drug bioavailability could be investigated [23, 24]. In practice, dietary conditions would likely be intermediate to the fasted and fed states utilized in this study, and, therefore, the 17% increases in C max between the tablet and capsule formulations are not expected to have a clinically meaningful impact on the benefit–risk profile of pirfenidone in patients with IPF.

During this study, all AEs were mild, with no discontinuations, serious AEs or deaths reported. The results are consistent with the known safety profile of pirfenidone [4, 5]. Overall, a smaller proportion of subjects experienced AEs in the fed state compared with the fasted state with both the tablet and capsule formulations. The observed food effect on the AE profile is consistent with that observed in previous studies for pirfenidone capsules [14], and reinforces the importance of taking pirfenidone with food, as has been noted previously [11]. However, it is notable that, in the fed state, only one AE of hot flush was reported with the capsule. This is in contrast to previous studies of the capsule in the fed state in which more AEs, including nausea and dizziness, were observed [14].

Previous studies suggested that C max and risk of adverse gastrointestinal events were correlated [14]. In this study, under the fasted state, both formulations had similar incidences of AEs and a similar C max was observed between the two dosage forms. In the fed state, a greater proportion of subjects experienced AEs with the tablet formulation compared with the capsule formulation. Although C max was slightly higher with the tablet versus the capsule formulation, there was no apparent relationship between drug exposure and AEs based on a graphical examination of the exposure–response relationship. For the tablet under fed conditions, the mean or median C max (or AUC0–∞) values for the subjects who experienced AEs were trending higher; however, the overall distribution of individual exposure values for these subjects when compared with the subjects without AEs is similar. Taken together, these observations indicate that the slightly higher C max observed with the tablet relative to the capsules in the fed state in this study is not expected to have a clinically meaningful impact on safety.

Clinical studies in patients with IPF have shown that pirfenidone reduces the decline in forced vital capacity and the risk of all-cause mortality versus placebo at 1 year [9, 10]. However, IPF is a chronic, progressive condition that requires long-term treatment. The simplified dosing regimen offered by the pirfenidone 801-mg tablet formulation may enhance longer-term adherence in patients once they are established on the recommended maintenance dose. Additional dose strengths, including 267- and 534-mg tablets, will accommodate the recommended dose titration and flexible dose modification until treatment is stabilized. Assessing the bioequivalence of the highest single dose is in accordance with the EMA and FDA guidelines, which state that it is sufficient to establish bioequivalence with the highest dose [23, 24]. Therefore, the results from this bioequivalence study, together with in vitro dissolution testing, support a biowaiver request for the 267- and 534-mg strengths of pirfenidone tablets.

Although our study was conducted in accordance with EMA and FDA guidelines on the investigation of bioequivalence [23, 24], the limitations of our methodology should be acknowledged. The subjects included in our study were healthy volunteers aged 18–55 years; however, in clinical practice, IPF is most commonly diagnosed in the seventh or eighth decade of life [3, 26, 27]. Patients with IPF have also been shown to have a high burden of comorbidities and concomitant medication [26, 28]. Therefore, it is possible that the AE profile observed in our study might not be representative of the real-world setting. However, it should be noted that the safety profile of the pirfenidone capsule formulation has been extensively characterized [29], and no significant differences in safety profile between the capsule and tablet formulation are anticipated.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results from this study demonstrated bioequivalence between the pirfenidone 1 × 801-mg tablet and pirfenidone 3 × 267-mg capsules in the fasted state in healthy adult volunteers. The small difference in C max between the tablet and the capsules observed in the fed state is not expected to have a clinically meaningful impact on the benefit–risk profile of pirfenidone, while the simplified dosing regimen with tablets may increase adherence to treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Indiana Strombom, an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., San Francisco, CA, USA, who was the safety scientific lead for this project. The authors would like to thank Fabian Schwarb and Neil Parrott, employees of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland, for their invaluable technical and scientific support during the development of the pirfenidone tablet formulation. The authors would like to thank David Kardatzke, an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., San Francisco, CA, USA, for his contribution to the statistical analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Journal and Open Access fees were provided by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Medical Writing

Medical writing support was provided by Catherine Stanton and Gráinne Faherty on behalf of Complete Medical Communications Ltd, funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, had full access to all of the data in the study, and take responsibility for the work as a whole, including the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All named authors have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

Lin Pan is an employee of Roche-Genentech and holds Roche shares. Paula Belloni is an employee of Roche-Genentech and holds Roche shares. Han Ting Ding is an employee of Roche-Genentech and holds Roche shares. Jianshuang Wang is an employee of Roche-Genentech and holds Roche shares. Wendy S. Putnam is an employee of Roche-Genentech and holds Roche shares. Christopher M. Rubino is a consultant to Roche-Genentech, and Executive Vice President of Pharmacometrics at the Institute of Clinical Pharmacodynamics, which had previously received grant funding from InterMune (now Roche). Lin Pan: Contributed to study design, interpretation of PK results, and authoring of CSR. Paula Belloni: Contributed to the review and interpretation of the PK and safety data. Han Ting Ding: Contributed to the analysis of PK and bioequivalence data. Jianshuang Wang: Contributed to the bioanalytical method validation and PK sample analysis. Christopher M. Rubino: Contributed to the design of the study/analysis methods and the interpretation of the results. Wendy S. Putnam: Contributed to study design, interpretation of PK results, and authoring of CSR.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being in the study.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article or as supplementary information files.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/B3E8F0606C5B1C8F.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0594-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the 2011 clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:e3–e19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley B, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:431–440. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0894CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Food and drug administration. Highlights of prescribing information Esbriet. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/208780s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2017.

- 5.European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics: Esbriet. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002154/WC500103049.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2017.

- 6.Schaefer CJ, Ruhrmund DW, Pan L, Seiwert SD, Kossen K. Antifibrotic activities of pirfenidone in animal models. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20:85–97. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Didiasova M, Singh R, Wilhelm J, et al. Pirfenidone exerts antifibrotic effects through inhibition of GLI transcription factors. FASEB J. 2017;31(5):1916–1928. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600892RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knuppel L, Ishikawa Y, Aichler M, et al. A novel antifibrotic mechanism of nintedanib and pirfenidone: inhibition of collagen fibril assembly. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;57(1):77–90. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0217OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of pooled data from three multinational phase 3 trials. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:243–253. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00026-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costabel U, Bendstrup E, Cottin V, et al. Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: expert panel discussion on the management of drug-related adverse events. Adv Ther. 2014;31:375–391. doi: 10.1007/s12325-014-0112-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nathan S, Lancaster L, Albera C, et al. Dose modifications and dose intensity during treatment with pirfenidone. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(Suppl 60):OA1764. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu J, Shang D, Xu X, et al. Effect of grapefruit juice and food on the pharmacokinetics of pirfenidone in healthy Chinese volunteers: a diet-drug interaction study. Xenobiotica. 2016;46:516–521. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2015.1089365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubino CM, Bhavnani SM, Ambrose PG, Forrest A, Loutit JS. Effect of food and antacids on the pharmacokinetics of pirfenidone in older healthy adults. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009;22:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi S, Wu J, Chen H, Chen H, Wu J, Zeng F. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of pirfenidone, an antifibrotic agent, in healthy Chinese volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:1268–1276. doi: 10.1177/0091270007304104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bansilal S, Castellano JM, Garrido E, et al. Assessing the impact of medication adherence on long-term cardiovascular outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S, Shin DW, Yun JM, et al. Medication adherence and the risk of cardiovascular mortality and hospitalization among patients with newly prescribed antihypertensive medications. Hypertension. 2016;67:506–512. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tangkiatkumjai M, Walker DM, Praditpornsilpa K, Boardman H. Association between medication adherence and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2016;21(3):504–512. doi: 10.1007/s10157-016-1312-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies. Evidence for action. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2017.

- 21.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1296–1310. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeder K, Fahey T, Ebrahim S. How can we improve adherence to blood pressure-lowering medication in ambulatory care? Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:722–732. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the investigation of bioequivalence. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2010/01/WC500070039.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2017.

- 24.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Food-effect bioavailability and fed bioequivalence studies. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM126833.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2017.

- 25. Washington N, Washington C, Wilson C. The stomach. In: Washington N, Washington C, Wilson C, editors. Physiological pharmaceutics: barriers to drug absorption. London: Taylor and Francis; 2001. p. 75–108.

- 26.Meltzer EB, Noble PW. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strand MJ, Sprunger D, Cosgrove GP, et al. Pulmonary function and survival in idiopathic vs secondary usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest. 2014;146:775–785. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wuyts W, Dahlqvist C, Slabbynck H et al. Demographics and healthcare utilization of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in a real-world setting: updated findings from 277 patients in the PROOF registry. Poster A1127 presented at the ATS 2017, 2017.

- 29.Lancaster L, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Safety of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: integrated analysis of cumulative data from 5 clinical trials. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2016;3:e000105. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2015-000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article or as supplementary information files.