Abstract

The genomic and metabolic features of Leuconostoc (Leu) mesenteroides were investigated through pan-genomic and transcriptomic analyses. Relatedness analysis of 17 Leu. mesenteroides strains available in GenBank based on 16S rRNA gene sequence, average nucleotide identity, in silico DNA-DNA hybridization, molecular phenotype, and core-genome indicated that Leu. mesenteroides has been separated into different phylogenetic lineages. Pan-genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains, consisting of 999 genes in core-genome, 1,432 genes in accessory-genome, and 754 genes in unique genome, and their COG and KEGG analyses showed that Leu. mesenteroides harbors strain-specifically diverse metabolisms, probably representing high evolutionary genome changes. The reconstruction of fermentative metabolic pathways for Leu. mesenteroides strains showed that Leu. mesenteroides produces various metabolites such as lactate, ethanol, acetate, CO2, mannitol, diacetyl, acetoin, and 2,3-butanediol through an obligate heterolactic fermentation from various carbohydrates. Fermentative metabolic features of Leu. mesenteroides during kimchi fermentation were investigated through transcriptional analyses for the KEGG pathways and reconstructed metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides using kimchi metatranscriptomic data. This was the first study to investigate the genomic and metabolic features of Leu. mesenteroides through pan-genomic and metatranscriptomic analyses, and may provide insights into its genomic and metabolic features and a better understanding of kimchi fermentations by Leu. mesenteroides.

Introduction

Leuconostoc (Leu.) mesenteroides comprises Gram-positive, catalase-negative, facultatively anaerobic, non-spore-forming, and spherical heterofermentative and mostly dextran-producing lactic acid bacteria (LAB), with coccus shapes and relatively low G + C contents1, 2. Leu. mesenteroides members are reported to be mainly responsible for the fermentation of various vegetables, such as kimchi (a Korean fermented vegetable food) and sauerkraut (pickled cabbage), under low temperature and moderate salinity conditions, although some Leu. mesenteroides strains have been isolated from dairy products such as cheese2–6. In particular, Leu. mesenteroides strains were found to be the major LAB, along with Lactobacillus (L.) sakei and Weissella koreensis, present during kimchi fermentation, suggesting that they are well adapted to kimchi fermentation conditions3, 7, 8. Moreover, because Leu. mesenteroides strains produce mannitol, a compound with antidiabetic and anticarcinogenic properties known for imparting a refreshing taste, and bacteriocins during fermentation and have some health improving effects3, 9, 10, they have been considered as starter cultures for kimchi fermentation or potential probiotics in industries11–13.

Although Leu. mesenteroides strains are generally considered to be non-infectious agents in humans, there have been some clinical reports that Leu. mesenteroides might be associated with certain human diseases such as brain abscess, endocarditis, nosocomial outbreaks, and central nervous system tuberculosis14–17. In addition, there is a report that Leu. mesenteroides can cause spoilage in some types of food products18. These reports suggest that further studies on the physiological and fermentative properties of Leu. mesenteroides strains are needed to vouch for the safety and quality of kimchi and sauerkraut products fermented with Leu. mesenteroides.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences have been widely used for the identification and diversity analysis of bacterial species. However, they are not appropriate for bacteria with high 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities such as LAB, suggesting that numerous bacterial strains that have been described as members of Leu. mesenteroides in previous studies, including the previously mentioned clinical reports, may not belong to Leu. mesenteroides. For example, Leu. mesenteroides ssp. suionicum was originally a subspecies member of Leu. mesenteroides due to high 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities (>99.72%), but was reclassified as a new species of the genus Leuconostoc (Leu. suionicum) based on genome comparisons2, 19. With the development of high-throughput and low-cost sequencing technologies, genomic information-based approaches have been extensively considered for the comprehensive understanding of metabolic properties and lifestyle traits of a microorganism. In particular, with the recent explosive increase of genome sequencing data, the concept of pan-genome has been introduced to explore the genomic and metabolic diversity of a given phylogenetic clade20–23. Because a pan-genome describes the entire genomic repertoire, representing all possible metabolic and physiological properties of a given phylogenetic clade and encodes for all possible lifestyles of a bacterial species, a pan-genome analysis provides insights into the genomic and metabolic features as well as a comprehensive understanding of the genome diversities and lifestyle traits of a bacterial species24–29. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the genome diversities and the genomic and metabolic features of Leu. mesenteroides strains using all genomes (pan-genome) of Leu. mesenteroides available in GenBank. In addition, we reconstructed the fermentative metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides strains based on their pan-genome and examined their fermentative metabolic features during kimchi fermentation, through a transcriptomic analysis.

Results and Discussion

Relatedness of Leu. mesenteroides strains based on 16S rRNA gene sequences

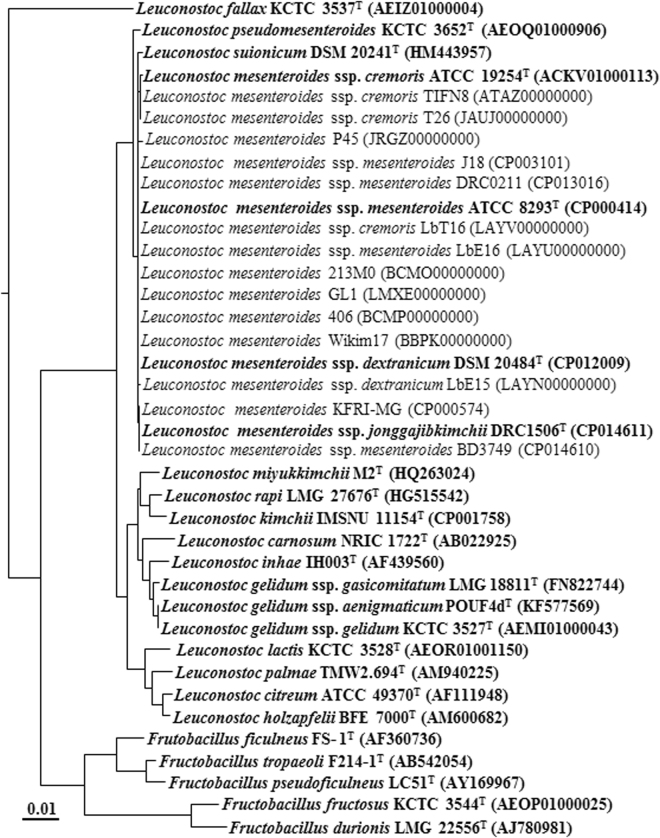

The genomes of all Leu. mesenteroides strains available in GenBank and the type strains of closely related species, Leu. suionicum and Leu. pseudomesenteroides, which had more than 99.54% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities, were retrieved and their general features are described in Table 1. To infer their phylogenetic relationships, a phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences was constructed with other closely related relatives (Fig. 1). All Leu. mesenteroides strains were clustered into a single phylogenetic lineage without any clear lineage differentiation. However, the phylogenetic tree showed that whereas Leu. pseudomesenteroides formed a distinct phylogenetic lineage from Leu. mesenteroides strains, Leu. suionicum, which was recently reclassified as a new species of the genus Leuconostoc from a subspecies of Leu. mesenteroides 2, 19, was not clearly separated from other Leu. mesenteroides strains by the 16S rRNA gene sequences. Currently, Leu. mesenteroides includes four type subspecies with valid published names: Leu. mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides, Leu. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris, Leu. mesenteroides subsp. dextranicum, and Leu. mesenteroides subsp. jonggajibkimchii 2. However, the phylogenetic tree also showed that the four Leu. mesenteroides subspecies were not differentiated by the 16S rRNA gene sequences, suggesting that this method is not appropriate to infer the phylogenetic relationships of Leu. mesenteroides strains. The phylogenetic analysis showed that Leu. fallax formed a clearly distinct phylogenetic lineage from the genera Leuconostoc as well as Fructobacillus (F.), suggesting that Leu. fallax may be reclassified as a new genus.

Table 1.

General features of the genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains and the type strains of closely related taxa used in this study§.

| Strain name in GenBank (accession no.) | Genome statusa (No. of contigs) | Total size (Mb) | G + C content (%) | No. of genes | No. of pseudogenes | Isolation source | Completeness (%)b | Contamination (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. jonggajibkimchii DRC1506T (CP014611–14) | C (4) | 1.98 | 37.72 | 1,957 | 140 | Kimchi | 97.04 | 0.76 |

| Leu. mesenteroides KFRI-MG (CP000574) | C (1) | 1.90 | 37.70 | 1,884 | 23 | Kimchi | 96.78 | 0.40 |

| Leu. mesenteroides P45 (JRGZ00000000) | D (6) | 1.87 | 37.50 | 1,837 | 59 | Pulque | 92.93 | 2.07 |

| Leu. mesenteroides Wikim17 (BBPK00000000) | D (41) | 1.86 | 37.80 | 1,844 | 62 | Kimchi | 97.98 | 0.64 |

| Leu. mesenteroides 406 (BCMP00000000) | D (69) | 2.00 | 37.70 | 2,018 | 82 | Airag | 98.55 | 1.16 |

| Leu. mesenteroides GL1 (LMXE00000000) | D (24) | 1.82 | 38.10 | 1,717 | 41 | Unknown | 96.82 | 0.87 |

| Leu. mesenteroides 213M0 (BCMO00000000) | D (58) | 2.03 | 37.70 | 2,031 | 74 | Airag | 99.39 | 1.74 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. mesenteroides ATCC 8293T (CP000414–15) | C (2) | 2.08 | 37.66 | 2,061 | 30 | Fermenting olives | 99.50 | 0.11 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. mesenteroides J18 (CP003101–05) | C (5) | 2.02 | 37.68 | 1,981 | 31 | Kimchi | 99.50 | 0.18 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. mesenteroides DRC0211 (CP013016–17, CP014602-4) | C (5) | 2.02 | 37.80 | 2,082 | 55 | Kimchi | 99.50 | 1.15 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. mesenteroides BD3749 (CP014610) | C (1) | 1.99 | 37.80 | 1,982 | 24 | Unknown | 98.60 | 2.07 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. mesenteroides LbE16 (LAYU00000000) | D (85) | 2.04 | 37.50 | 2,097 | 123 | Italian soft cheese | 97.91 | 6.79 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. dextranicum DSM 20484T (CP012009–10) | C (2) | 1.85 | 38.04 | 1,876 | 95 | Cheese | 96.67 | 3.10 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. dextranicum LbE15 (LAYN00000000) | D (63) | 2.01 | 37.60 | 2,045 | 103 | Italian soft cheese | 97.69 | 4.26 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. cremoris ATCC 19254T (ACKV01000000) | D (126) | 1.74 | 38.50 | 1,702 | 178 | Hansen’s dried cheese | 96.37 | 0.11 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. cremoris TIFN8 (ATAZ00000000) | D (173) | 1.71 | 38.20 | 1,844 | 513 | Dairy starter cultures | 91.00 | 0.78 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. cremoris LbT16 (LAYV00000000) | D (65) | 1.91 | 37.80 | 1,937 | 183 | Italian soft cheese | 97.48 | 2.19 |

| Leu. mesenteroides ssp. cremoris T26 (JAUJ00000000) | D (130) | 1.83 | 38.40 | 1,930 | 242 | Undefined cheese | 94.77 | 4.48 |

| Leu. suionicum DSM 20241T (CP015247–48) | C (2) | 2.05 | 37.60 | 2,034 | 55 | Unknown | 97.44 | 2.57 |

| Leu. pseudomesenteroides KCTC 3652T (AEOQ00000000) | D (1160) | 3.24 | 38.30 | 3,785 | 1,245 | Cane juice |

§The genome analysis was carried out using the NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/annotation_prok/).

aGenome status: D, draft genome sequence; C, complete genome sequence.

bDetermined by CheckM.

Figure 1.

A phylogenetic tree using the NJ algorithm based on 16S ribosomal RNA sequences showing the phylogenetic relationships among Leuconostoc mesenteroides strains and related taxa. Weissella viridescens NRIC 1536T was used as an outgroup (not shown). The type strains are highlighted in bold. The scale bar equals 0.01 changes per nucleotide.

Relatedness based on average nucleotide identity (ANI) and in silico DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) analyses and general features of Leu. mesenteroides genomes

Because the ANI cut-off value corresponding to 70% DDH threshold used as the gold standard for the delineation of prokaryotic species has been suggested to be approximately 95–96%30–32, ANI values among the genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains, Leu. suionicum, and Leu. pseudomesenteroides were pair-wise calculated (Supplementary Fig. S1). The ANI analysis clearly showed that Leu. pseudomesenteroides KCTC 3652T and Leu. suionicum DSM 20241T shared less than the ANI cut-off value for the prokaryotic species delineation with other Leu. mesenteroides strains, corroborating the results of a previous study2. All Leu. mesenteroides strains shared higher ANI values (97.2–99.5%) than the ANI cut-off value, indicating that they belong to the same species. In silico DDH analysis also showed that all Leu. mesenteroides strains shared higher in silico DDH values (77.5–99.1%) than the 70% DDH threshold, whereas Leu. suionicum DSM 20241T and Leu. pseudomesenteroides KCTC 3652T shared clearly lower in silico DDH values than the 70% DDH threshold for the prokaryotic species delineation with other Leu. mesenteroides strains (Supplementary Fig. S2), confirming that strains DSM 20241T and KCTC 3652T represent new species distinct from other Leu. mesenteroides strains2.

The genome quality assessment conducted by the CheckM software (Table 1) showed that all genomes had ≥91.0% completeness and ≤6.8% contamination values, which satisfied the criteria for the genomes to be considered near complete (≥90%) with medium contamination (≤10%)33. However, the genome of Leu. mesenteroides ssp. cremoris TIFN8 contained numerous pseudogenes with frame shifts, most likely owing to incomplete genes by numerous contigs or high rates of sequencing error, and was therefore excluded from the next pan-genome analysis of Leu. mesenteroides strains. The average size and total gene number of Leu. mesenteroides genomes used for the pan-genome analysis were 1.94 ± 0.1 Mb and 1,940 ± 118, respectively. The genome of Leu. mesenteroides ssp. cremoris ATCC 19254T was the smallest (1.74 Mb), whereas the genome of Leu. mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides ATCC 8293T was the largest (2.08 Mb). The G + C contents of Leu. mesenteroides strains ranged from 37.5% to 38.5%. The number of rRNA and tRNA genes in the completed genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains were 12 and 68–70, respectively.

Pan- and core-genome analysis of Leu. mesenteroides

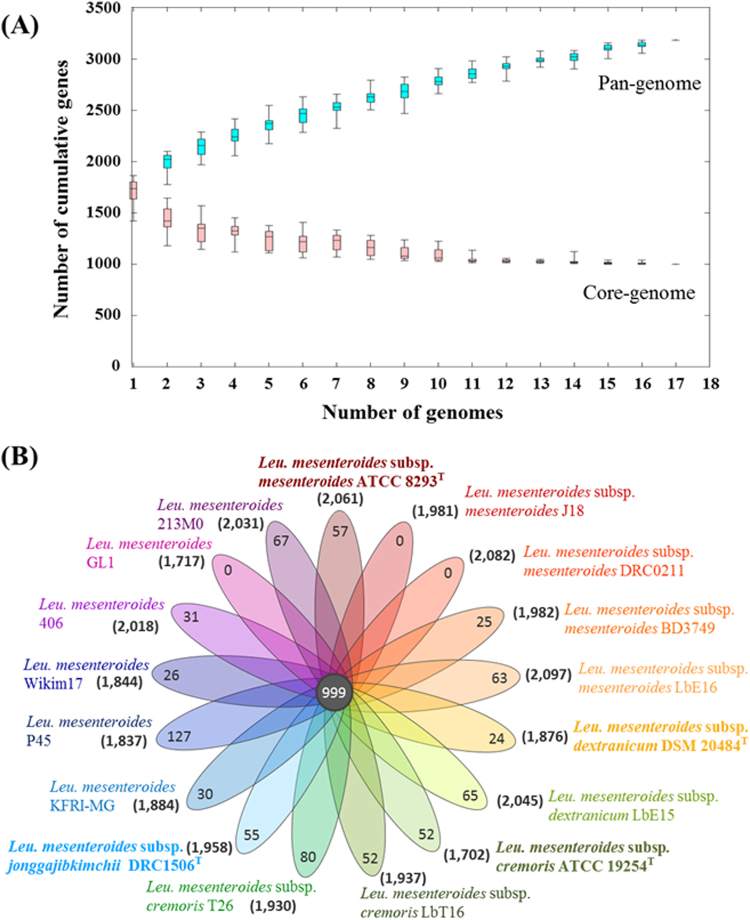

The pan-genome is a powerful concept that can be used to effectively represent the genomic features of a bacterial lineage, and its analysis can provide insights into the genome dynamics and evolution of the lineage as well. Therefore, a pan-genome analysis for Leu. mesenteroides was performed using 17 Leu. mesenteroides genomes (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. S3). The expected gene number for a given number of genomes in a pan-genome analysis can be estimated by a curve fitting represented by the Heaps’ law (n = k*N-α, where n is the expected gene number for a given number of genomes (N) and k is a constant to fit the specific curve)34. According to the Heaps’ law, an α < 1 is representative of an open pan-genome, meaning that each added genome contributes new genes and increases the pan-genome, whereas an α > 1 represents a closed pan-genome, in which the addition of new genomes does not significantly increase the pan-genome. The formula showed that the pan-genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains increases with an α of 0.23, indicating an open pan-genome and suggesting high evolutionary changes in Leu. mesenteroides genomes, through gene loss and gain or horizontal gene transfer (HGT) to adapt efficiently to new environmental conditions. The pan-genome for the 17 Leu. mesenteroides strains contained a total of 3,185 genes consisting of 999 genes in the core-genome, 1,432 genes in the accessory-genome (present in more than two strains), and 754 genes in the unique genome (Supplementary Table S1). Unique genes that differ among Leu. mesenteroides strains, which may reflect different niches and needs for the survival of Leu. mesenteroides strains and may be used in differentiating Leu. mesenteroides strains35.

Figure 2.

Pan- and core-genome plot (A) and flower plot diagram (B) of 17 Leu. mesenteroides strains. An ordered list of the 17 strains was randomly generated and 20 sets of the randomly ordered strains were subjected to pan- and core-genome analysis. The average number of core- and pan-genome sizes were plotted with standard deviations. The pan-genome represents the total genes of genomes in a subset sampled and the core-genome represents the genes shared by all genomes in the same subset. The flower plot diagram represents gene numbers in the core-genome (in the center) and unique-genome (in the petals) of Leu. mesenteroides pan-genome, and in the genome of each Leu. mesenteroides strain (in the parentheses). The type strains of Leu. mesenteroides subspecies are highlighted in bold.

Strain P45 was shown to have the highest number of unique genes (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Table 1), suggesting that this strain may have exchanged genes most actively with other bacterial groups. For example, strain P45 harbors a fructose-bisphosphate aldolase unique gene that is very closely related to the gene homolog of the Leu. pseudomesenteroides genome, with a 99% amino acid sequence identity, which indicates that strain P45 might have gained the gene by HGT from Leu. pseudomesenteroides. Strain P45 harbors another unique gene encoding a peptide ABC transporter ATP-binding protein, possibly conferring it an antibacterial activity as bacteriocin36. The gene has the highest amino acid sequence identity (83%) with a gene homolog of F. pseudoficulneus, indicating that the gene might have also been transferred by HGT. Strain LbT16 has four lactate dehydrogenase genes (ldh), including a unique gene (Supplementary Table 1). This unique ldh gene is most closely related to an ldh gene homolog found on the genome of Leu. pseudomesenteroides, with a 98% amino acid sequence identity, which implies that strain LbT16 might have acquired the gene by HGT. These results suggest that HGT may be one of major mechanisms to foster genome variations or speciation in Leu. mesenteroides strains and their relatives37.

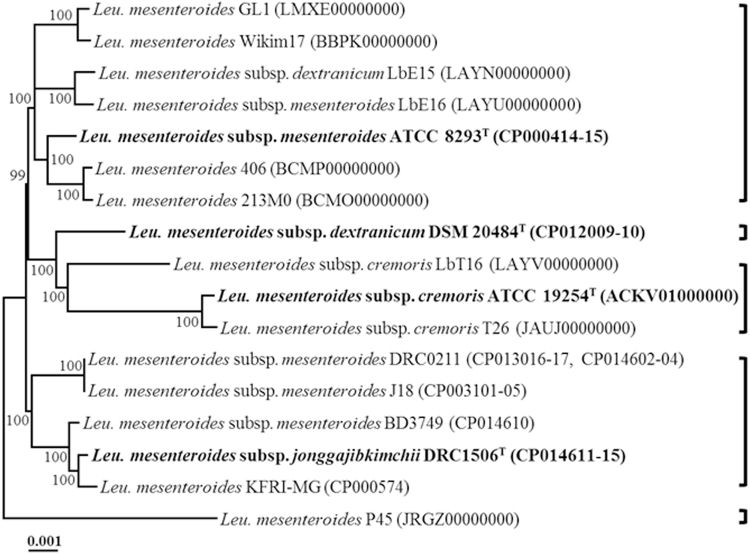

Relatedness of Leu. mesenteroides strains based on core-genomes and molecular phenotypes

To infer the phylogenetic relationships among Leu. mesenteroides strains, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the concatenated amino acid sequences of 999 genes in the core-genome (Fig. 3). Unlike the phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, the phylogenetic tree based on the core-genome showed that Leu. mesenteroides strains have been more clearly separated into different phylogenetic lineages, which were relatively consistent with the hierarchical clustering based on ANI and in silico DDH values of Figs 2 and 3. All strains of the phylogenetic lineage containing Leu. mesenteroides subsp. jonggajibkimchii DRC1506T as the type subspecies were isolated from fermented vegetables (mainly kimchi), which suggests that these lineage members became well adapted to the fermentation environments of vegetables. Strain P45, isolated from a traditional Mexican alcoholic fermented beverage and having the highest number of unique genes, formed a phylogenetic lineage clearly distinct from other Leu. mesenteroides strains, which may reflect a different habitat of strain P45 (alcoholic fermented beverage) from those of other Leu. mesenteroides strains (fermented vegetables).

Figure 3.

A phylogenetic tree with bootstrap values (1,000 replicates) reconstructed using the concatenated amino acid sequences of Leu. mesenteroides core-genome (999 genes) showing the relationships among Leu. mesenteroides strains. Strain names as described in GenBank or validated names are used in the tree and the type strains are highlighted in bold. The bar indicates 0.001 substitutions per site.

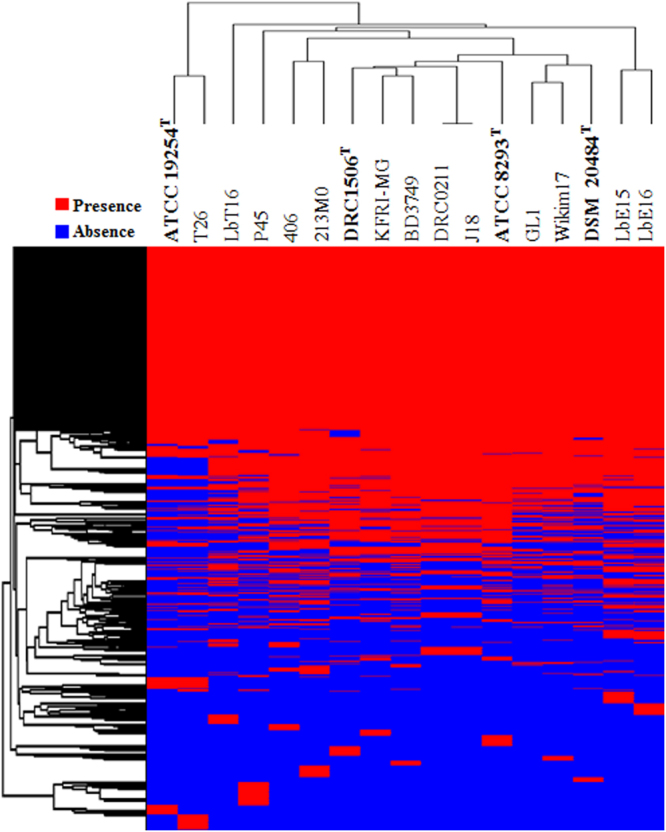

Gene gain or loss, and HGT between the genomes of organisms occur continuously during the evolutionary processes. It is generally accepted that closely related organisms share more orthologous genes, suggesting that evolutionary relationships among Leu. mesenteroides can be inferred by the presence/absence of orthologous genes. A total of 3,185 genes were identified from the genomes of 17 Leu. mesenteroides strains. However, the heat map based on the presence/absence of these genes showed that the hierarchical clustering was slightly different from those based on ANI and in silico DDH values, and core-genomes (Fig. 4), indicating that gene gain or loss and HGT may have occurred among Leu. mesenteroides strains as well as other clade organisms.

Figure 4.

Heat-map and hierarchical clustering of 17 Leu. mesenteroides strains based on the presence (red) or absence (blue) of genes. The type strains of Leu. mesenteroides subspecies are highlighted in bold.

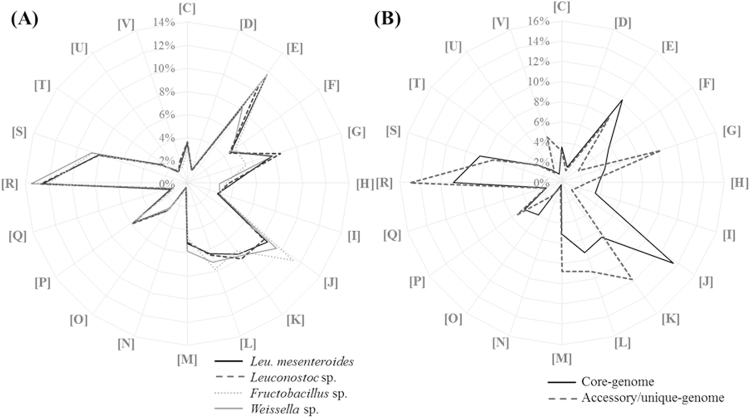

Clusters of orthologous groups (COG) analysis of Leu. mesenteroides genomes

The analysis of functional categories enriched in a pan-genome may provide valuable clues in identifying the selective pressures and evolutionary developments of a bacterial lineage22, 38. Therefore, all genes in the genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains were functionally classified based on their COG categories, and their average abundances were compared with those in the genomes of closely related taxa (Leuconostoc species except for Leu. mesenteroides, Fructobacillus species, and Weissella species) (Fig. 5A). Functional genes belonging to COG categories involved in carbohydrate and energy metabolism, including amino acid transport and metabolism (E); carbohydrate transport and metabolism (G); translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (J); transcription (K); and general function prediction only (R) were enriched in the genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains (>6%). The distribution of functional genes into COG categories in Leu. mesenteroides was relatively similar to those of closely related LAB, suggesting that the distribution of the COG categories may be a general feature of the genomes of LAB that have adapted to similar environmental conditions.

Figure 5.

Comparison of COG functional categories in the pan-genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains and closely related bacterial taxa (Leuconostoc species except for Leu. mesenteroides, Fructobacillus species, and Weissella species) (A) and distribution of the COG functional categories in the core- and accessory/unique-genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains (B). The alphabetic codes represent COG functional categories as follows: C, energy production and conversion; D, cell division and chromosome partitioning; E, amino acid transport and metabolism; F, nucleotide transport and metabolism; G, carbohydrate transport and metabolism; H, coenzyme metabolism; I, lipid metabolism; J, translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis; K, transcription; L, DNA replication, recombination, and repair; M, cell envelope biogenesis, outer membrane; N, cell motility and secretion; O, post-translational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones; P, inorganic ion transport and metabolism; Q, secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism; R, general function prediction only; S, function unknown; T, signal transduction mechanisms; U, intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport; V, defense mechanisms.

A functional characterization of the core- and accessory/unique genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains was also performed, by assigning the core- and accessory/unique genome to a COG functional category, and some clear differences between the core- and accessory/unique-genome were observed (Fig. 5B). As expected, genes involved in housekeeping processes including translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (J); amino acid transport and metabolism (E); nucleotide transport and metabolism (F); lipid transport and metabolism (I); and posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones (O) were more enriched in the core-genome than in the accessory/unique genome. In contrast, COG categories related to energy metabolism or DNA repair, including carbohydrate transport and metabolism (G); transcription (K); DNA replication, recombination, and repair (L); cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (M); general function prediction only (R); and defense mechanisms(V) were more abundant in the accessory/unique-genome than in the core-genome. Higher abundance of genes corresponding to carbohydrate transport and metabolism (G) in the accessory/unique-genome than in the core-genome suggests that the fermentation features of Leu. mesenteroides strains for carbohydrate compounds differ among Leu. mesenteroides strains.

Most Leuconostoc species are intrinsically resistant to vancomycin due to a peculiar cell wall structure with d-lactate instead of d-alanine at the terminal end of peptidoglycans, and not by general antibiotic resistance mechanisms18, 39, 40. It was reported that the d-alanyl-d-alanine ligase that synthesizes d-alanyl-d-alanine in Leu. mesenteroides can also synthesize d-alanyl-d-lactate of the peptidoglycan41, 42. Our analysis revealed that a gene encoding d-alanyl-d-alanine ligase (Enzyme Commission (EC) 6.3.2.4) was identified from the genomes of all Leu. mesenteroides strains at the core genome, which confirms that the vancomycin resistance is a common species feature of Leu. mesenteroides. Because there were some clinical reports of the possible pathogenicity of Leu. mesenteroides, we investigated the presence of virulence genes from the pan-genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains. The genes encoding hemolysin and hemolysin III that have been considered as potential virulence genes were identified from the core genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains43, 44 — any other known potential virulence genes were not identified from the pan-genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains. The two hemolysin and hemolysin III-coding genes were also identified from the genomes of LAB such as L. rhamnosus GG, L. plantarum, and L. sakei that are well-known as safe probiotics. However, our tests showed that Leu. mesenteroides strains J18, DRC0211, DRC1506T, and ATCC 8293T did not show any hemolytic activity (data not shown), which may suggest that Leu. mesenteroides strains do not have pathogenic activities related to hemolysin and hemolysin III genes. However, further studies are needed to investigate the pathogenic possibility of Leu. mesenteroides strains as an infectious agent in humans.

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) and fermentative metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides

To investigate the metabolic features and diversities of Leu. mesenteroides, all functional genes of 17 Leu. mesenteroides strains were cumulatively mapped onto KEGG pathways (Fig. 6). Some sequencing errors in the genome sequencing are generated by base over- or under-call, resulting in frame shift errors in gene sequences, which eventually cause the incorrect description of normal genes as pseudogenes during the genome annotation process. It is inferred that some portions of pseudogenes shown in Table 1 might be caused by genome sequencing errors. Therefore, in this study, genes identified from 15–16 Leu. mesenteroides genomes were defined as soft core-genome and the metabolic pathways identified from more than 15 genomes were considered as common metabolisms in Leu. mesenteroides.

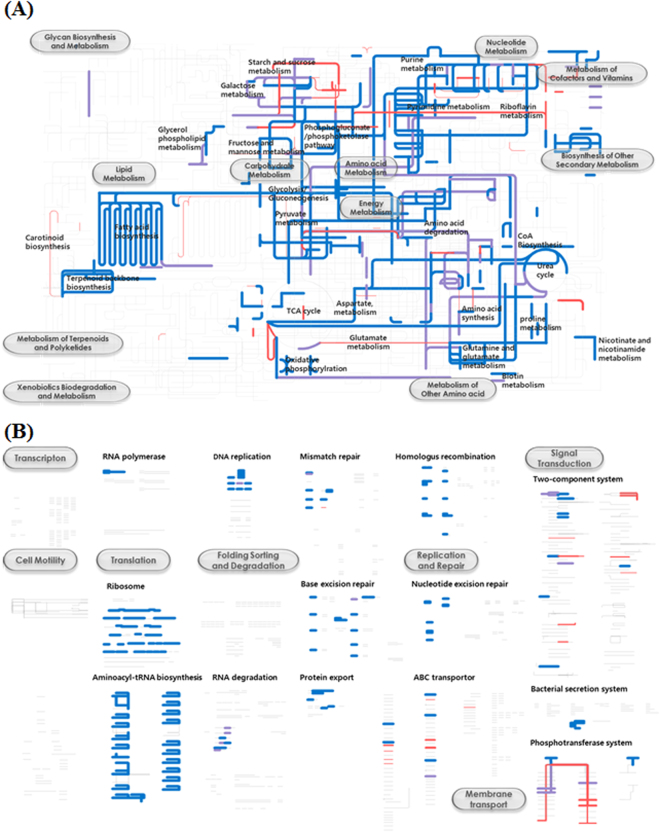

Figure 6.

Metabolic (A) and regulatory (B) pathways of Leu. mesenteroides strains. The pathways were generated using the iPath v2 module based on KEGG Orthology numbers of genes identified from the genomes of 17 Leu. mesenteroides strains. Metabolic pathways identified from all 17 genomes, belonging to the core-genome, are depicted in blue and metabolic pathways identified from 15–16 genomes, belonging to the soft core-genome, are depicted in violet. Metabolic pathways identified from 1–14 genomes, belonging to accessory/unique-genome, are depicted in red. Line thickness is proportional to the numbers of Leu. mesenteroides strains harboring the metabolic pathways.

The KEGG pathway analysis showed that all Leu. mesenteroides strains harbors the 6-phosphogluconate/phosphoketolase pathway, pyruvate metabolism, and incomplete glycolysis pathway and TCA cycle (Fig. 6A), representing the obligate heterolactic fermentation of Leu. mesenteroides. In addition, the KEGG analysis showed that Leu. mesenteroides strains have fatty acid biosynthesis, galactose degradation, fructose and mannose metabolism, purine and pyrimidine metabolism, amino acid metabolism, coenzyme A biosynthesis, and oxidative phosphorylation as common metabolic pathways. Genes associated with starch and sucrose metabolism (Fig. 6A), phosphotransferase systems (PTS), two-component systems, and ABC transporter (Fig. 6B) are present in the accessory- or unique-genome, which suggests that carbohydrate metabolisms may be different between Leu. mesenteroides strains. The KEGG analysis also showed that riboflavin biosynthesis may be different depending on Leu. mesenteroides strains.

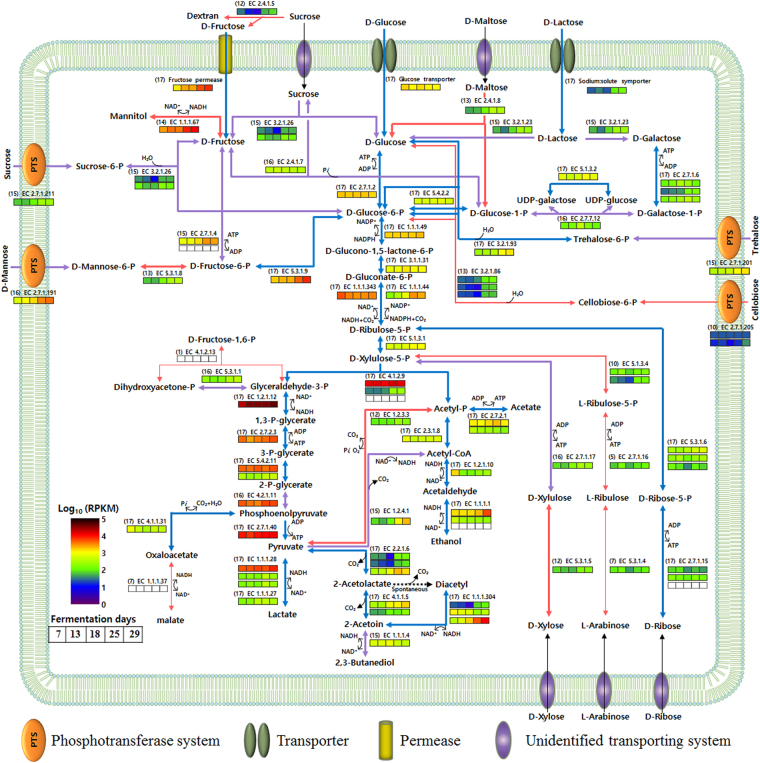

Based on the predicted KEGG pathways and BLASTP analysis of genes related to carbohydrate fermentation, the fermentative metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides strains for carbohydrates were reconstructed (Fig. 7) and genomes deficient for genes encoding proteins forming the reconstructed fermentative metabolic pathways are listed in supplementary Table S2. Diverse carbohydrate transport systems, including sugar phosphotransferase systems (PTS), transporters, and permeases were found from the genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains, indicating that Leu. mesenteroides can metabolize diverse carbohydrates. Genes associated with the metabolism of glucose, fructose, ribose, lactose, sucrose, mannose, and trehalose were identified from the core- or soft core-genome of Leu. mesenteroides, indicating that they may be common carbohydrates metabolized fermentatively by Leu. mesenteroides. Conversely, genes associated with the metabolism of maltose, xylose, arabinose, and cellobiose were identified from the accessory genome of Leu. mesenteroides, indicating that the metabolic ability of Leu. mesenteroides for them may differ between Leu. mesenteroides strains. Most Leu. mesenteroides strains have been reported to produce dextran, a viscous glucose homopolysaccharide with predominantly α-(1,6)-glycosidic linkages, and this can be a common feature of Leu. mesenteroides 45, 46. However, a gene encoding dextransucrase (a glycosyltransferase, EC 2.4.1.5) that synthesizes dextran from sucrose was found from the genomes of 11 Leu. mesenteroides strains, which suggests that the dextran production differs between Leu. mesenteroides strains and is not a common feature of Leu. mesenteroides.

Figure 7.

Proposed fermentative metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides for carbohydrates and their transcriptional expressions during kimchi fermentation. Metabolic pathways that were present in all Leu. mesenteroides strains are depicted in blue (core-genome) and metabolic pathways that were present in 15–16 Leu. mesenteroides strains are depicted in violet (soft core-genome). Metabolic pathways that were present in 1–14 Leu. mesenteroides strains are depicted in red (unique- or accessory-genome). Line thickness in the pathways is proportional to the number of Leu. mesenteroides strains harboring the corresponding genes, which are indicated in parentheses before EC numbers. Carbohydrate transport systems with black arrows indicate unidentified transporting systems that may be present in Leu. mesenteroides genomes. The transcriptional expressions were visualized by heatmaps based on their RPKM values and the white boxes represent no transcriptional expression during kimchi fermentation. Kimchi samples for the metatranscriptomic analysis were obtained at 7, 13, 18, 25, and 29 days. UDP, uridine diphosphate.

The carbohydrate metabolic capabilities of Leu. mesenteroides strains shown in the reconstructed fermentative metabolic pathways were verified using the type strains of four Leu. mesenteroides subspecies (ssp. mesenteroides, ssp. jonggajibkimchii, ssp. dextranicum, and ssp. cremoris) harboring different carbohydrate transport systems and metabolic genes (Supplementary Table S3). All test strains had capabilities to ferment d-glucose, sucrose, and gluconate. The types strains of Leu. mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides and Leu. mesenteroides ssp. jonggajibkimchii that harbor diverse carbohydrate transport systems had capabilities to ferment various carbohydrates including trehalose, d-maltose, d-mannose, d-lactose, l-arabinose, d-xylose, mannitol, and d-ribose, while the type strain of Leu. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris deficient in genes encoding fructokinase (EC 2.7.1.4), β-galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.23), PTS cellobiose transporter subunit IIABC (EC 2.7.1.205), 6-phospho-β-glucosidase (3.2.1.86), maltose phosphorylase (EC 2.4.1.8), and mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (EC 5.3.1.8) did not have a capability to ferment various carbohydrates including fructose, d-lactose, cellulobios, maltose, d-mannose, and mannitol. In addition, the type strain of Leu. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris deficient in glycosyltransferase (EC 2.4.1.5) gene did not produce dextran, while other three Leu. mesenteroides subspecies harboring the gene produced dextran. These test results were in good accordance with their genome-based metabolic properties shown in Fig. 7. However, some fermentation capabilities of the test strains were different from their genome-based metabolic properties. For example, the type strains of Leu. mesenteroides ssp. jonggajibkimchii and Leu. mesenteroides subsp. dextranicum deficient in genes encoding l-arabinose isomerase (EC 5.3.1.4), ribulokinase (EC 2.7.1.16), and ribulose phosphate epimerase (EC 5.1.3.4) had an ability to ferment l-arabinose. In addition, the type strain of Leu. mesenteroides ssp. jonggajibkimchii did not ferment cellobiose although the strain harbors a cellobiose PTS system in its genome, which suggests that we need further studies to explore the functions and expressions of genes and their metabolic properties in Leu. mesenteroides strains.

All genes involved in the 6-phosphogluconate/phosphoketolase pathway, representing the heterolactic fermentation to produce lactate, ethanol, and carbon dioxide were retrieved from the core-genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains (Fig. 7), confirming that the heterolactic fermentation is a common metabolic feature of Leu. mesenteroides. Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (EC 4.1.2.13), which splits fructose 1,6-bisphosphate into dihydroxyacetone-phosphate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, is known as a key enzyme of homofermentative LAB, but deficient in heterofermentative LAB. Despite this, a gene encoding fructose-bisphosphate aldolase was found from Leu. mesenteroides strain P45 harboring the complete heterofermentative pathway. However, because a gene encoding 6-phosphofructokinase (EC 2.7.1.11), another key enzyme for homolactic fermentation that catalyzes the phosphorylation of fructose-6-phosphate to fructose 1,6-bisphosphate, is deficient in strain P45, Leu. mesenteroides strains most likely perform only heterolactic fermentation. It is inferred that the fructose-bisphosphate aldolase coding gene in strain P45 might have been accidentally acquired from a homofermentative LAB through a lateral gene transfer. Pyruvate, originating from glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, a product of d-xylulose-5-phosphate cleavage by phosphoketolase (EC 4.1.2.9) in heterolactic fermentation, is converted into lactate by lactate dehydrogenases with the regeneration of NAD+. Figure 7 shows that Leu. mesenteroides strains harbor three copies of d-lactate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.28) and one copy of l-lactate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.27) in the core-genome, which may support previous reports that Leu. mesenteroides strains produce more d-lactate than l-lactate47. Our genome analysis revealed that a gene encoding the membrane-bound d-lactate dehydrogenase (EC. 1.1.5.12) that is distinct from other general d- or l-lactate dehydrogenases was additionally identified from two Leu. mesenteroides strains (DSM 20284T and Wikim17). It was reported that this membrane-bound d-lactate dehydrogenase oxidizes d-lactate to pyruvate with the generation of two electrons that are eventually transferred into oxygen through an electron transport system under aerobic conditions, not anaerobic conditions48, 49, which suggests that the enzyme might not be associated with the metabolite production during fermentation.

The reconstructed fermentative metabolic pathways showed that, in addition to the conversion of pyruvate to lactate, pyruvate can be alternatively converted into other fermentative metabolites in Leu. mesenteroides strains. Diacetyl and acetoin are known to be important cheese flavors in dairy products50. Genes encoding acetolactate synthase (EC 2.2.1.6), acetolactate decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.5), and diacetyl reductase (EC 1.1.1.304) that convert pyruvate to diacetyl and/or acetoin were found from the core-genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains, indicating that diacetyl or acetoin may be also common major flavoring compounds in fermented foods where Leu. mesenteroides strains are involved. However, 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.4) that converts 2-acetoin to 2,3-butanediol with the regeneration of NAD+ was also found from the soft-core genome. This may suggest that this enzyme can somewhat weaken cheese flavoring intensities in foods fermented by Leu. mesenteroides strains; fermented foods such as kimchi and sauerkraut fermented by Leu. mesenteroides strains do not smell strongly of cheese flavoring. The reconstructed fermentative metabolic pathways also showed that pyruvate can be converted into acetyl-CoA with the production of carbon dioxide and NADH by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (EC 1.2.4.1). A gene encoding the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex was found from the soft core-genome, indicating that acetyl-CoA production from pyruvate may be a common metabolic pathway in Leu. mesenteroides strains. Finally, a gene encoding pyruvate oxidase (EC 1.2.3.3) was found from 12 Leu. mesenteroides genomes, enabling the strains to convert pyruvate into acetyl phosphate (acetyl-P) and carbon dioxide when oxygen is available51, 52.

Acetyl-P is another split product of d-xylulose-5-phosphate by phosphoketolase in the heterolactic fermentation, and it is eventually converted into ethanol with the regeneration of NAD+ or acetate with the production of ATP as the final products, indicating that the final products are decided by reduction potentials (NADH concentrations) inside the cell. Heterofermentative LAB that produce lactic acid, ethanol, and carbon dioxide from glucose generate one mole of ATP per mole of glucose, meaning that they are less competitive than homofermentative LAB that produce 2 moles of ATP per mole of glucose. The reconstructed fermentative metabolic pathways showed that 14 Leu. mesenteroides genomes harbor a gene encoding mannitol dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.67) that produces mannitol9. The remaining three genomes (strains ATCC 19254T, DSM 20484T, and T26) also harbor the gene as a pseudogene, possibly having mannitol dehydrogenase activity because the annotations as pseudogenes can be caused by sequencing errors. Carvalheiro et al.53 reported that strains ATCC 19254T and DSM 20484T produced mannitol through the consumption of fructose, suggesting that they have a mannitol dehydrogenase activity. These results suggest that mannitol production may be a common species feature of Leu. mesenteroides. Mannitol is produced through fructose reduction with the consumption of NADH, which may cause the production of acetate instead of ethanol due to the lack of NADH; one mole of ATP will be additionally produced per 2 moles of mannitol production. This suggests that heterofermentative Leu. mesenteroides with mannitol dehydrogenase activity can be as competitive as homofermentative LAB in terms of energy production during fermentation of vegetables containing fructose8. This is in accordance with the previous results that Leu. mesenteroides was dominant in vegetable fermentations such as kimchi and sauerkraut, which contain fructose7, 54, 55.

Metabolic properties of Leu. mesenteroides during kimchi fermentation

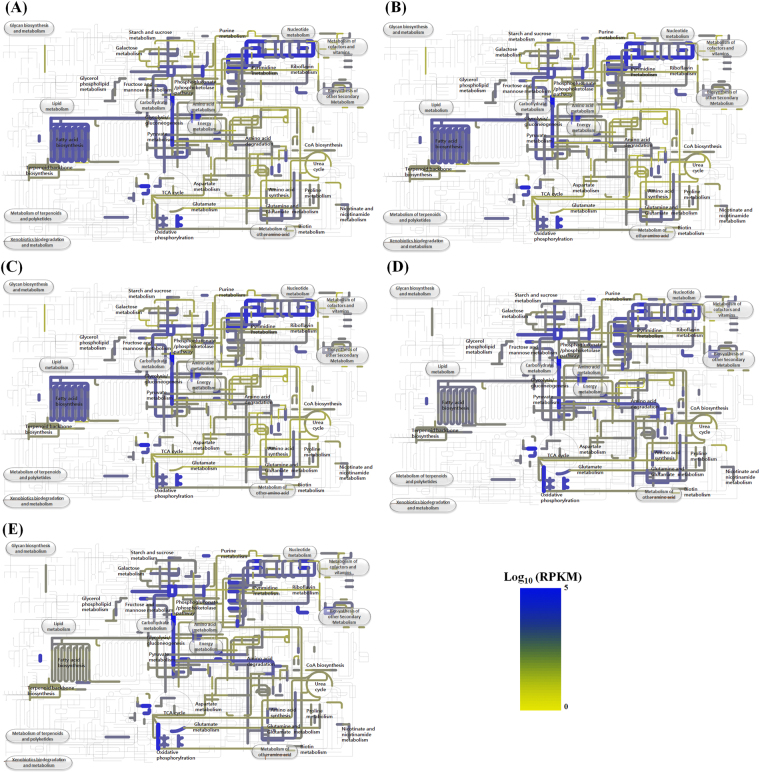

Traditional kimchi that is fermented naturally at low temperatures without any starter is a complex system, with dynamic biological and biochemical changes during fermentation. Because kimchi fermentation is accomplished by a succession of naturally occurring different LAB, fermentative metabolic features of microbial communities during kimchi fermentation process are different every time, which makes it difficult to consistently produce standardized kimchi with high quality. Until now, rational and systematic approaches to control kimchi fermentation for the production of kimchi with uniform quality have not been developed because the understanding of kimchi microbial communities during fermentation has not yet been accomplished. Therefore, comprehensive investigation on the fermentative metabolic features of kimchi LAB during fermentation is indispensable to control kimchi fermentation7, 8, 12. With metatranscriptomic analysis, it is relatively easy to investigate the metabolic features of microbial communities in fermented foods such as kimchi, because these communities are not so complex as those in other natural environments56–59. Therefore, in this study, a transcriptomic analysis was performed to examine the metabolic features of Leu. mesenteroides during kimchi fermentation. Relative abundances (%) of mRNA sequencing reads mapped to the genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains for total LAB mRNA sequencing reads during the kimchi fermentation were calculated. The relative abundances were high at the early kimchi fermentation period and decreased to the lowest value at 18 days as the fermentation progressed (Supplementary Fig. S4), suggesting that members of Leu. mesenteroides are more responsible for kimchi fermentation during the early fermentation period. The metabolic properties of Leu. mesenteroides during kimchi fermentation were investigated by metabolic mapping of the Leu. mesenteroides mRNA sequencing reads onto the KEGG pathways of Leu. mesenteroides strains (Fig. 8). The transcriptomic analysis showed that genes associated with carbohydrate metabolisms, nucleotide metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, riboflavin metabolism, and glutamine and glutamate metabolism were highly expressed during kimchi fermentation. Genes associated with fatty acid biosynthesis, nucleotide metabolism, and amino acid metabolism, probably more related to cell growth, were up-regulated in Leu. mesenteroides during the early kimchi fermentation period, which may explain why Leu. mesenteroides is more abundant at that stage. Conversely, genes associated with oxidative phosphorylation, biosynthesis of other secondary metabolisms, and glutamine and glutamate metabolism were up-regulated during the late kimchi fermentation period. Genes associated with the biosynthesis of riboflavin were highly expressed during the entre kimchi fermentation, suggesting that Leu. mesenteroides may be an important producer of riboflavin during kimchi fermentation.

Figure 8.

Transcriptional expressions of the metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides at 7 (A), 13 (B), 18 (C), 25 (D), and 29 (E) days during kimchi fermentation. The metabolic pathways were generated using the iPath v2 module based on KEGG Orthology numbers identified from the pan-genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains. The transcriptional expression levels of the metabolic pathways are depicted by line thickness and color change based on their RPKM values (based on a log2 scale).

The fermentative metabolic features of Leu. mesenteroides for carbohydrates were more thoroughly investigated by the transcriptomic analysis of respective genes corresponding to the fermentative metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides during kimchi fermentation (Fig. 7). The transcriptomic analysis showed that Leu. mesenteroides in the kimchi samples performed heterolactic fermentation using diverse carbohydrates including glucose, fructose, mannose, trehalose, sucrose, maltose, and cellobiose. All genes corresponding to the heterolactic fermentation to produce lactate, ethanol, and carbon dioxide were highly expressed during the entire kimchi fermentation. The transcriptomic analysis showed that genes associated with the transport of glucose, fructose, and mannose were highly expressed, which suggests that glucose, fructose, and mannose may be major carbon sources during kimchi fermentation. A gene associated with a glucose transporter had relatively high expression during the early kimchi fermentation period, whereas genes associated with the transport of other carbon sources such as fructose, mannose, trehalose, and sucrose were highly expressed during the late fermentation period, which suggests that Leu. mesenteroides uses glucose more preferably than other carbon sources during kimchi fermentation, similar to other LAB60.

Leu. mesenteroides is known to be more responsible for kimchi fermentation during the early fermentation period, and its contribution to kimchi fermentation decreases gradually as the fermentation progresses3, 8. Metatranscriptomic analysis also showed that the transcriptional activity of Leu. mesenteroides was high in the early period and decreased gradually as kimchi fermentation progressed7 (supplementary Fig. S4). In addition, genes associated with cell growth such as fatty acid biosynthesis, nucleotide metabolism, and amino acid metabolism were up-regulated during the early kimchi fermentation period (Fig. 8). However, genes associated with fermentative metabolisms of Leu. mesenteroides for carbohydrates, probably more related to energy production, were generally up-regulated during the late fermentation period (Fig. 7), which may be due to the energy needs of Leu. mesenteroides under stress conditions of kimchi (e.g., low pH, depletion of carbon sources) towards the end of fermentation61. A gene encoding pyruvate oxidase that catalyzes the conversion between pyruvate and acetyl-P was expressed during the kimchi fermentation, although the expression levels were relatively low. Because the conversion from pyruvate to acetyl-P occurs when oxygen is available and kimchi fermentation is processed under anaerobic conditions, the conversion from acetyl-P to pyruvate may be the major direction of pyruvate oxidase in kimchi fermentation. The transcriptome analysis showed that the genes encoding fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (EC 4.1.2.13) and malate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.37), identified from only one genome and seven genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains, respectively, were not expressed during the entire kimchi fermentation period, suggesting that Leu. mesenteroides strains in kimchi may not harbor the genes. The transcriptome analysis also showed that genes encoding acetolactate synthase (EC 2.2.1.6), acetolactate decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.5), and diacetyl reductase (EC 1.1.1.304) that convert pyruvate to diacetyl and/or acetoin were expressed during the kimchi fermentation, indicating that diacetyl and/or acetoin may be major flavoring compounds in kimchi. However, a gene encoding butanediol dehydrogenase that converts 2-acetoin to 2,3-butanediol was also highly expressed, which may explain the weak cheese flavoring intensities of fermented kimchi.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the genomic diversity and features of Leu. mesenteroides strains performing heterolactic fermentation by using the pan-genome of Leu. mesenteroides strains and analyzing their metabolic features through the COG and KEGG analyses. In addition, we reconstructed the fermentative metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides and examined its fermentative metabolic features for various carbohydrates through a metatranscriptomic analysis during kimchi fermentation. This study shows that the pan-genomic and metatranscriptomic analyses of kimchi LAB provide a better understanding of their comprehensive genomic and metabolic features during kimchi fermentation.

Materials and Methods

Genomes used in this study and phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequences

At the time of writing (December 2016), the genome sequences of all Leu. mesenteroides strains and the type strains of Leu. suionicum and Leu. pseudomesenteroides, close relatives of Leu. mesenteroides, available in GenBank were downloaded and quality-assessed using the CheckM software (ver. 1.0.4)33. To infer evolutionary relationships among Leu. mesenteroides strains and their relative taxa, a phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequences was conducted. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of all Leu. mesenteroides strains with whole genome sequencing information in GenBank and their closely related type strains were aligned using the Infernal secondary-structure aware aligner, available in the Ribosomal Database Project (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/)62. A phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences was constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm of the PHYLIP software (ver. 3.695)63. All genome sequences of Leuconostoc sp., Fructobacillus sp., and Weissella sp. were also downloaded from the GenBank database to compare with the genomes of Leu. mesenteroides.

ANI and in silico DDH analyses

Genome-based ANI and in silico DDH analyses were used to evaluate the relatedness among Leu. mesenteroides strains and the type strains of Leu. suionicum and Leu. pseudomesenteroides. The pair-wise ANI values among the genomes, including chromosomes and plasmids, of all Leu. mesenteroides strains and the type strains of Leu. suionicum and Leu. pseudomesenteroides were calculated using a stand-alone software (http://www.ezbiocloud.net/sw/oat)64, with the following recommended parameters: minimum length, 700 bp; minimum identity, 70%; minimum alignment, 50%; BLAST window size, 1000 bp; and step size, 200 bp. The pair-wise in silico DDH values among the whole genomes were computed using the server-based genome-to-genome distance calculator ver. 2.1 (http://ggdc.dsmz.de/distcalc2.php)65, with BLAST+ for genome alignments66. The pair-wise relatedness values of ANI and in silico DDH were visualized as heat-maps and hierarchical clustering using GENE-E (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/GENE-E/).

Pan- and core-genome analyses and a core-genome-based phylogenetic analysis

Pan- and core-genome analyses were performed using a bacterial pan-genome analysis pipeline (BPGA, ver. 1.2)67. The core-genome was extracted from the whole genomes of all Leu. mesenteroides strains using the USEARCH program (ver. 9.0)68, with a 50% sequence identity cut-off, available in BPGA. The concatenated amino acid sequences of the core-genome were aligned using the MUSCLE program (ver. 3.8.31)69. A core-genome-based phylogenetic tree with bootstrap values (1,000 replicates) was constructed based on a maximum likelihood algorithm using the MEGA ver. 7 software70.

Relatedness based on molecular phenotypes and COG analysis

Clustering of functional genes derived from the whole genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains was performed using the USEARCH program against the COG database within BPGA, with a default parameter setting. The clustered outputs were presented as gene presence/absence binary matrices in each genome and they were plotted using the GENE-E program with one minus the Pearson correlation distances for clustering of rows (genes) and columns (genomes).

For the functional characterization of the genomes of Leu. mesenteroides (or the core-genome and accessory/unique-genome of Leu. mesenteroides) and closely related taxa, Leuconostoc sp., Fructobacillus sp., and Weissella sp., functional genes derived from their respective genomes were COG-categorized using the USEARCH program and the portions of genes assigned to each COG category were expressed as relative percentages. For the functional comparison among Leu. mesenteroides and closely related taxa, average values of the relative percentages in each COG category within the taxa were used.

KEGG analysis and reconstruction of fermentative metabolic pathways

Predicted proteins derived from the whole genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains were submitted to BlastKOALA (http://www.kegg.jp/blastkoala/)71 for functional annotation based on KEGG Orthology (KO), and the metabolic and regulatory pathways of Leu. mesenteroides strains based on KO numbers were generated using the iPath v2 module (http://pathways.embl.de/iPath2.cgi#). Metabolic pathways in the KEGG pathways were displayed by line thickness and color based on the numbers of Leu. mesenteroides strains harboring genes with the same KO numbers. To investigate the fermentative metabolic features of Leu. mesenteroides, fermentative metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides strains for carbohydrates were reconstructed based on the predicted KEGG pathways and EC numbers. In addition, the presence or absence of the metabolic genes in each Leu. mesenteroides strain was manually confirmed through BLASTP analyses against the genomes of Leu. mesenteroides strains, using reference protein sequences available in other closely related strains. The carbohydrate fermentation capabilities of Leu. mesenteroides strains were tested by using API 50 CH system (bioMèrieux, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the type strains of four Leu. mesenteroides subspecies [ssp. mesenteroides ATCC 8293T, ssp. jonggajibkimchii DRC 1506T, ssp. dextranicum KACC 12315T (=DSM 20484T), and ssp. cremoris KCTC 3529T (=ATCC 19254T)] harboring different carbohydrate transport systems were used. In addition, dextran production of four Leu. mesenteroides subspecies was evaluated by mucoid properties of colonies grown on MRS agar supplemented with 5% (w/v) sucrose instead of glucose2.

Expressional analysis of Leu. mesenteroides during kimchi fermentation

Kimchi metatranscriptomic sequencing data (deposited in GenBank with the acc. no. of SRX128705) that were obtained at 7, 13, 18, 25, and 29 days of kimchi fermentation in the previous study7 were used to investigate the metabolic features of Leu. mesenteroides during kimchi fermentation. Total mRNA sequencing reads with high quality for each kimchi sample were obtained from the raw metatranscriptomic sequencing data, as described previously7. The total mRNA sequencing reads of each kimchi sample were matched to the genomes of 17 Leu. mesenteroides strains and other kimchi LAB identified from the kimchi samples (Leu. gasicomitatum LMG 18811, Leu. gelidum JB7, Leu. carnosum JB16, L. sakei subsp. sakei 23 K, and Weissella koreensis KACC 15510) that were reported in the previous study7 using the BWA software72, based on the matching criteria of best-match with a 90% minimum identity and 20 bp minimum alignment, and putative Leu. mesenteroides sequencing reads were obtained. RPKM values (read numbers per kb of each coding sequences (CDS), per million mapped reads) for the quantification of the relative gene expressions were calculated based on Leu. mesenteroides mRNA sequencing reads that mapped onto CDS of 17 Leu. mesenteroides strains. Metabolic mapping of Leu. mesenteroides mRNA sequencing reads against the KEGG pathways of Leu. mesenteroides strains was quantitatively performed, and transcriptional expression levels of respective metabolic pathways at each kimchi fermentation time were displayed by line thickness and color change, based on the RPKM values of genes corresponding to the metabolic pathways, as described previously73. In addition, the transcriptional expression profiles of genes corresponding to the fermentative metabolic pathways of Leu. mesenteroides for carbohydrates during kimchi fermentation were indicated by heatmap based on their RPKM values.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the World Institute of Kimchi (KE1702-2), funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning and the Strategic Initiative for Microbiomes in the Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (as part of the multi-ministerial) Genome Technology to Business Translation Program, Republic of Korea.

Author Contributions

C.O.J. conceived the ideas and supervised the work. S.H.L. developed the concepts and B.H.C., K.H.K., and H.H.J. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. B.H.C., S.H.L., and C.O.J. wrote the manuscript. The manuscript has been reviewed and edited by all authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Byung Hee Chun and Kyung Hyun Kim contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-12016-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Se Hee Lee, Email: leesehee@wikim.re.kr.

Che Ok Jeon, Email: cojeon@cau.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Garvie EI. Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris (Knudsen and Sørensen) comb. nov. and Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. dextranicum (Beijerinck) comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1983;33:118–119. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeon, H. H. et al. A proposal of Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. jonggajibkimchii subsp. nov. and reclassification of Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. suionicum (Gu et al., 2012) as Leuconostoc suionicum sp. nov. based on complete genome sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol in press doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.001930 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jung JY, et al. Metagenomic analysis of kimchi, a traditional Korean fermented food. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2264–2274. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02157-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cibik R, Lepage E, Tailliez P. Molecular diversity of Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Leuconostoc citreum isolated from traditional french cheeses as revealed by RAPD fingerprinting, 16S rDNA sequencing and 16S rDNA fragment amplification. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2000;23:267–278. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(00)80014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breidt F., Jr. A genomic study of Leuconostoc mesenteroides and the molecular ecology of sauerkraut fermentations. J Food Sci. 2004;69:30–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2004.tb17874.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Cagno R, Coda R, De Angelis M, Gobbetti M. Exploitation of vegetables and fruits through lactic acid fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2013;33:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung JY, et al. Metatranscriptomic analysis of lactic acid bacterial gene expression during kimchi fermentation. Int J Food Microbiol. 2013;163:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung JY, Lee SH, Jeon CO. Kimchi microflora: history, current status, and perspectives for industrial kimchi production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:2385–2393. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wisselink H, Weusthuis R, Eggink G, Hugenholtz J, Grobben G. Mannitol production by lactic acid bacteria: a review. Int Dairy J. 2002;12:151–161. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(01)00153-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beganović J, et al. Improved sauerkraut production with probiotic strain Lactobacillus plantarum L4 and Leuconostoc mesenteroides LMG 7954. J Food Sci. 2011;76:M124–M129. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eom H-J, Park JM, Seo MJ, Kim M-D, Han NS. Monitoring of Leuconostoc mesenteroides DRC starter in fermented vegetable by random integration of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;35:953–959. doi: 10.1007/s10295-008-0369-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung JY, et al. Effects of Leuconostoc mesenteroides starter cultures on microbial communities and metabolites during kimchi fermentation. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;153:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi Y-J, et al. Potential use of lactic acid bacteria Leuconostoc mesenteroides as a probiotic for the removal of Pb (II) toxicity. J Microbiol. 2017;55:296–303. doi: 10.1007/s12275-017-6642-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albanese A, et al. Molecular identification of Leuconostoc mesenteroides as a cause of brain abscess in an immunocompromised patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3044–3045. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00448-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bou G, et al. Nosocomial outbreaks caused by Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:968. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.070581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vázquez E, et al. Infectious endocarditis caused by Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1998;16:237–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barletta J, et al. Meningitis due to Leuconostoc mesenteroides associated with central nervous system tuberculosis: a case report. Ann Clin Case Rep. 2017;2:1228. [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Paula AT, Jeronymo-Ceneviva AB, Todorov SD, Penna ALB. The two faces of Leuconostoc mesenteroides in food systems. Food Rev Int. 2015;31:147–171. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2014.981825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu CT, Wang F, Li CY, Liu F, Huo GC. Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. suionicum subsp. nov. Int J Syst Evol microbiol. 2012;62:1548–1551. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.031203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Q, Tun HM, Leung FC-C, Shah NP. Genomic insights into high exopolysaccharide-producing dairy starter bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus ASCC 1275. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4974. doi: 10.1038/srep04974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi H, Chun J, Cha C-J. Genomic insights into the taxonomic status of the three subspecies of Bacillus subtilis. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2014;37:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Endo A, et al. Comparative genomics of Fructobacillus spp. and Leuconostoc spp. reveals niche-specific evolution of Fructobacillus spp. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:1117. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2339-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Illeghems K, De Vuyst L, Weckx S. Comparative genome analysis of the candidate functional starter culture strains Lactobacillus fermentum 222 and Lactobacillus plantarum 80 for controlled cocoa bean fermentation processes. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:766. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1927-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng X, Phillippy AM, Li Z, Salzberg SL, Zhang W. Probing the pan-genome of Listeria monocytogenes: new insights into intraspecific niche expansion and genomic diversification. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:500. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hao P, et al. Complete sequencing and pan-genomic analysis of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus reveal its genetic basis for industrial yogurt production. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douillard FP, et al. Comparative genomic and functional analysis of 100 Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains and their comparison with strain GG. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caputo A, et al. Pan-genomic analysis to redefine species and subspecies based on quantum discontinuous variation: the Klebsiella paradigm. Biology Direct. 2015;10:55. doi: 10.1186/s13062-015-0085-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, et al. High correlation between genotypes and phenotypes of environmental bacteria Comamonas testosteroni strains. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:110. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1314-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vernikos G, Medini D, Riley DR, Tettelin H. Ten years of pan-genome analyses. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;23:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goris J, et al. DNA–DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosselló-Móra R, Amann R. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2015. Past and future species definitions for Bacteria and Archaea; pp. 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25:1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tettelin H, Riley D, Cattuto C, Medini D. Comparative genomics: the bacterial pan-genome. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang BK, Cho MS, Park DS. Red pepper powder is a crucial factor that influences the ontogeny of Weissella cibaria during kimchi fermentation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28232. doi: 10.1038/srep28232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giles-Gómez M, et al. In vitro and in vivo probiotic assessment of Leuconostoc mesenteroides P45 isolated from pulque, a Mexican traditional alcoholic beverage. SpringerPlus. 2016;5:708. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ceapa C, et al. The variable regions of Lactobacillus rhamnosus genomes reveal the dynamic evolution of metabolic and host-adaptation repertoires. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8:1889–1905. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frantzen CA, et al. Genomic characterization of dairy associated Leuconostoc species and diversity of Leuconostocs in undefined mixed mesophilic starter cultures. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:132. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Handwerger S, Pucci M, Volk K, Liu J, Lee M. Vancomycin-resistant Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactobacillus casei synthesize cytoplasmic peptidoglycan precursors that terminate in lactate. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:260–264. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.260-264.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rojo-Bezares B, et al. Assessment of antibiotic susceptibility within lactic acid bacteria strains isolated from wine. Int J Food Microbiol. 2006;111:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Il-Park S, Walsh CT. d-Alanyl-d-lactate and d-alanyl-d-alanine synthesis by d-alanyl-d-alanine ligase from vancomycin-resistant Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Effects of a phenlyalanine 261 to tyrosine mutation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9210–9214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuzin AP, et al. Enzymes of vancomycin resistance: the structure of d-alanine-d-lactate ligase of naturally resistant Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Structure. 2000;8:463–470. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ike Y, Hashimoto H, Clewell D. Hemolysin of Streptococcus faecalis subspecies zymogenes contributes to virulence in mice. Infect Immun. 1984;45:528–530. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.2.528-530.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y-C, Chang M-C, Chuang Y-C, Jeang C-L. Characterization and virulence of hemolysin III from Vibrio vulnificus. Curr Microbiol. 2004;49:175–179. doi: 10.1007/s00284-004-4288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hehre EJ, Sugg JY. Serologically reactive polysaccharides produced through the action of bacterial enzymes: I. Dextran of Leuconostoc mesenteroides from sucrose. J Exp Med. 1942;75:339. doi: 10.1084/jem.75.3.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siddiqui NN, Aman A, Silipo A, Qader SAU, Molinaro A. Structural analysis and characterization of dextran produced by wild and mutant strains of Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;99:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li L, et al. Characterization of the major dehydrogenase related to d-lactic acid synthesis in Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides ATCC 8293. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2012;51:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsushita K, Kaback HR. d-lactate oxidation and generation of the proton electrochemical gradient in membrane vesicles from Escherichia coli GR19N and in proteoliposomes reconstituted with purified d-lactate dehydrogenase and cytochrome o oxidase. Biochem. 1986;25:2321–2327. doi: 10.1021/bi00357a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dym O, Pratt EA, Ho C, Eisenberg D. The crystal structure of d-lactate dehydrogenase, a peripheral membrane respiratory enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9413–9418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Passerini D, et al. New insights into Lactococcus lactis diacetyl-and acetoin-producing strains isolated from diverse origins. Int J Food Microbiol. 2013;160:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marty-Teysset C, et al. Proton motive force generation by citrolactic fermentation in Leuconostoc mesenteroides. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2178–2185. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2178-2185.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drider D, Bekal S, Prévost H. Genetic organization and expression of citrate permease in lactic acid bacteria. Genet Mol Res. 2004;3:271–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carvalheiro F, Moniz P, Duarte LC, Esteves MP, Gírio FM. Mannitol production by lactic acid bacteria grown in supplemented carob syrup. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;38:221–227. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0823-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Otgonbayar G-E, Eom H-J, Kim BS, Ko J-H, Han NS. Mannitol production by Leuconostoc citreum KACC 91348P isolated from kimchi. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;21:968–971. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1105.05034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park E-J, et al. Bacterial community analysis during fermentation of ten representative kinds of kimchi with barcoded pyrosequencing. Food Microbiol. 2012;30:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weckx S, et al. Community dynamics of bacteria in sourdough fermentations as revealed by their metatranscriptome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:5402–5408. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00570-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lessard M-H, Viel C, Boyle B, St-Gelais D, Labrie S. Metatranscriptome analysis of fungal strains Penicillium camemberti and Geotrichum candidum reveal cheese matrix breakdown and potential development of sensory properties of ripened Camembert-type cheese. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:235. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolfe BE, Dutton RJ. Fermented foods as experimentally tractable microbial ecosystems. Cell. 2015;161:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Filippis F, Genovese A, Ferranti P, Gilbert JA, Ercolini D. Metatranscriptomics reveals temperature-driven functional changes in microbiome impacting cheese maturation rate. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21871. doi: 10.1038/srep21871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gänzle MG. Lactic metabolism revisited: metabolism of lactic acid bacteria in food fermentations and food spoilage. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2015;2:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2015.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farrand SG, Jones CW, Linton JD, Stephenson RJ. The effect of temperature and pH on the growth efficiency of the thermoacidophilic bacterium Bacillus acidocaldarius in continuous culture. Arch Microbiol. 1983;135:276–283. doi: 10.1007/BF00413481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nawrocki EP, Eddy SR. Query-dependent banding (QDB) for faster RNA similarity searches. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e56. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Felsenstein, J. PHYLIP (phylogeny inference package), version 3.6a, Seattle: Department of genetics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA (2002).

- 64.Lee I, Kim YO, Park S-C, Chun J. OrthoANI: an improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:1100–1103. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk H-P, Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Camacho C, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chaudhari NM, Gupta VK, Dutta C. BPGA-an ultra-fast pan-genome analysis pipeline. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24373. doi: 10.1038/srep24373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jin HM, et al. Genome-wide transcriptional responses of Alteromonas naphthalenivorans SN2 to contaminated seawater and marine tidal flat sediment. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21796. doi: 10.1038/srep21796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.