The results presented in this study show for the first time that the barn owl is able to extract and represent the interaural time difference (ITD) information conveyed by the envelope of a broadband acoustic signal. Like mammals, the barn owl extracts the ITD of the envelope and the carrier of a signal from the same frequency range. These results are of general interest, since they reinforce a trend found in neural signal processing across different species.

Keywords: sound localization, carrier, envelope, auditory arcopallium, extracellular recordings

Abstract

Birds and mammals use the interaural time difference (ITD) for azimuthal sound localization. While barn owls can use the ITD of the stimulus carrier frequency over nearly their entire hearing range, mammals have to utilize the ITD of the stimulus envelope to extend the upper frequency limit of ITD-based sound localization. ITD is computed and processed in a dedicated neural circuit that consists of two pathways. In the barn owl, ITD representation is more complex in the forebrain than in the midbrain pathway because of the combination of two inputs that represent different ITDs. We speculated that one of the two inputs includes an envelope contribution. To estimate the envelope contribution, we recorded ITD response functions for correlated and anticorrelated noise stimuli in the barn owl’s auditory arcopallium. Our findings indicate that barn owls, like mammals, represent both carrier and envelope ITDs of overlapping frequency ranges, supporting the hypothesis that carrier and envelope ITD-based localization are complementary beyond a mere extension of the upper frequency limit.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The results presented in this study show for the first time that the barn owl is able to extract and represent the interaural time difference (ITD) information conveyed by the envelope of a broadband acoustic signal. Like mammals, the barn owl extracts the ITD of the envelope and the carrier of a signal from the same frequency range. These results are of general interest, since they reinforce a trend found in neural signal processing across different species.

the interaural time difference (ITD) is an important cue for azimuthal sound localization (Blauert 1997; Rayleigh 1907; Saberi et al. 1998; Vonderschen and Wagner 2014). Both the carrier signal (fine structure) and the envelope of a sound may contain ITD information. A variety of mammalian species show psychophysical (e.g., Dietz et al. 2009; Ewert et al. 2012; Keating et al. 2013) as well as neural (e.g., Griffin et al. 2005; Joris and Yin 1995; Yin et al. 1984) sensitivity to carrier and envelope ITDs. In the barn owl, sensitivity to the ITD of the carrier signal has been demonstrated (e.g., Hausmann et al. 2009; Moiseff and Konishi 1981), while the possible influence of the stimulus envelope on sound localization behavior and ITD-dependent neural responses has not been investigated. Examining whether such sensitivity to the ITD of the stimulus envelope exists in the barn owl was the goal of this work.

The barn owl is an interesting case for this question because these birds are able to use carrier ITDs over nearly their entire hearing range (Köppl 1997). Thus, in contrast to mammals, barn owls do not need to rely on envelope ITDs to extend the upper limit of ITD-based sound localization (Henning 1974; Joris 2003). Recent studies, however, have indicated that in mammals the use of envelope ITD might not be restricted to high frequencies (Agapiou and McAlpine 2008; Benichoux et al. 2015).

Joris (2003) proposed a method to estimate the contribution of the carrier and the envelope to the representation of ITD. Extending the methods introduced by Joris (2003), Agapiou and McAlpine (2008) systematically varied the interaural correlation of a broadband noise stimulus by changing independently both interaural phase difference (IPD) and ITD. This approach allowed the detection of envelope elements in neural responses by the existence of delay asymmetries. The delay asymmetry describes an envelope ITD-dependent, phase-invariant change in the neural response that is independent of other nonlinear elements like rectification (Agapiou and McAlpine 2008).

We speculated that the asymmetry in the ITD response functions of neurons in the barn owl’s telencephalic auditory arcopallium (AAr) observed by Vonderschen and Wagner (2009, 2012) resembles the delay asymmetry reported by Agapiou and McAlpine (2008) and may be derived from a combination of carrier and envelope inputs. Previous studies demonstrated that AAr neurons respond highly selectively to binaural localization cues (Cohen and Knudsen 1995; Vonderschen and Wagner 2009), and behavioral studies demonstrated the relevance of the forebrain pathway for sound localization (Knudsen et al. 1993; Knudsen and Knudsen 1996; Wagner 1993). We therefore studied the contributions of the stimulus’s carrier and envelope to the responses of ITD-sensitive AAr neurons following Joris (2003). We analyzed delay asymmetry and phase sensitivity in the responses to assess the existence and separability of envelope and carrier contributions, respectively. Our findings indicate that barn owls, like mammals, are able to represent the ITD of both the stimulus carrier and the stimulus envelope.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal treatment.

Seven adult barn owls (Tyto furcata pratincola) of both sexes were used in extracellular electrophysiological recording experiments. All procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal experimentation and were conducted under a permit of the State Agency for Nature, Environment and Consumer Protection (LANUV) Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany. The procedures followed those detailed in Vonderschen and Wagner (2009) and Singheiser et al. (2012). Briefly, the barn owl was food deprived and its general state of health was determined the day before the experiment. On the day of the experiment, the bird was sedated with an intramuscular injection of diazepam (Valium, 1 mg/kg; Ratiopharm, Ulm, Germany) 30 min before anesthesia started. Twenty minutes before the surgery the animal received buprenorphine (Temgesic, 0.06 mg/kg; Essex Pharma, Munich, Germany) as analgesic, and anesthesia was induced by an intramuscular injection of ketamine (20 mg/kg; Ceva, Düsseldorf, Germany). Additionally, atropine (Atropinsulfat, 0.05 mg/kg; Braun, Melsungen, Germany) was administered intraperitoneally to prevent salivation. After anesthesia was induced, the owl was wrapped in a jacket to restrain the animal and reduce the risk of self-induced injuries.

Experiments were conducted in an anechoic chamber (IAC 403 A; Industrial Acoustics, Niederkrüchten, Germany). For the electrophysiological recordings, the head of the anesthetized barn owl was fixed to the recording device via a previously implanted head plate, the scalp was opened, and either a small craniotomy was made at the desired recording location or a previously introduced craniotomy was opened to expose the brain surface. The electrode was placed at the intended location and lowered into the brain. A recording session typically lasted for several hours. Anesthesia was maintained by continuous intramuscular injections of diazepam (1 mg/ml) and ketamine (20 mg/kg) in 2- to 3-h intervals. Anesthesia was monitored visually with an infrared camera within the anechoic chamber as well as by checking the bird’s heart rate and neural activity. The temperature of the anechoic chamber was generally kept above 20°C. At the end of the experiments an additional dose of buprenorphine was injected intramuscularly, the craniotomy was sealed with dental cement and covered with Polyspectran ointment (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX), and the scalp was closed with sutures. Afterwards, the owl was placed in a recovery box, where it was monitored and housed for the next 12–36 h.

Acoustic signals.

Acoustic signals were generated with BrainWare software and System II hardware from Tucker-Davis Technologies (TDT) (Alachua, FL). The stimuli were sampled at 100 kHz. The stimulus duration was 100 ms with 5-ms cosine rise and decay ramps. After digital-to-analog conversion, the signals were attenuated by programmable attenuators, antialias filtered [DA3-4, PA4, FT6 (all TDT)], power amplified (Yamaha AX 590), and presented via calibrated earphones (Sony MDR-E831LP). The earphones were positioned directly behind the owl’s ear flaps abutting the ear canal.

Electrophysiological recordings.

Electrophysiological data were recorded at a sampling rate of 25 kHz with Epoxylite-insulated tungsten microelectrodes (9–12 MΩ or 13–15 MΩ; FHC, Bowdoinham, ME). The recording interval, corresponding to one trial or stimulus repetition, had a duration of 1 s and was divided into three segments. The first segment was 400 ms of silence during which spontaneous activity was measured. The 100-ms-long stimulus was presented in the second segment, followed by 500 ms of silence in the third segment. This paradigm proved to yield adaptation-free responses in earlier experiments (Vonderschen and Wagner 2009). The recorded signals were preamplified, impedance matched, amplified, and filtered (50-Hz notch filter; 300–5,000 Hz band-pass filtered; M. Walsh Electronics, Pasadena, CA), analog-to-digital converted (AD1; TDT), and fed to a computer. Preliminary online analysis and visual spike sorting were done in BrainWare (TDT). Spike sorting was refined off-line also with BrainWare. Spikes were detected with a threshold mechanism. Afterwards, spikes were clustered on the basis of their amplitude and temporal width and the first three elements of a principal component analysis of their shapes. Only spikes from single neurons were included in our analysis. All analyzed neurons had an absolute refractory period of at least 1.42 ms. Following Vonderschen and Wagner (2009), AAr neurons were identified by their general response properties and their position relative to the stereotaxic head mount.

After a unit had been isolated from the background response, the characteristic response properties of the neuron were determined by recording the response to broadband noise (0.1–25 kHz) with varying ITD (−330 to 330 µs, 30-µs steps, 5 repetitions) or interaural level difference (ILD) (−20 to +20 dB, 4-dB steps, 5 repetitions) and tonal stimuli of varying frequencies (~500 to ~12,500 Hz, 498- to 521-Hz steps, 10 repetitions). The response curves resulting from varying ITDs, while stimulating with broadband noise and keeping ILDs constant, are called noise-delay functions (NDFs). Positive ITDs correspond to contralateral leading sounds, while ipsilateral leading sounds were represented by negative ITDs. The neuron’s response threshold was estimated with rate level functions with broadband noise stimuli recorded at the neuron’s best ITD and ILD (60 to −20 dB SPL, 8-dB steps, and 10 repetitions). The threshold was given by the lowest sound level that elicited a response of at least 10% of the maximum response in the rate level function. After the neuron’s response properties and its threshold were determined, NDFs for correlated (NDF0) and anticorrelated (NDF180) noise stimuli (0.1–25 kHz) were recorded (−330 to 330 µs, 30-µs steps, at least 10 repetitions). In the correlated configuration, the signals at the two ears differed only in their ITD, while in the phase-shifted configuration a phase shift of 180° was introduced by multiplying one of the two signals by −1. Like the frequency-response curves, the two NDFs were recorded at the best ILD and 20–30 dB above the neuron’s threshold. For 21 neurons, we recorded additional NDF0 and NDF180, using high-frequency noise stimuli. The high-frequency stimuli were created by high-pass filtering broadband noise stimuli (0.1–25 kHz) with a windowed sinc filter that was combined with a Blackman window (Smith 1999).

| (1) |

The filter’s cutoff frequency (f) was chosen individually for each neuron after examination of the neuron’s frequency-response functions. Cutoff frequencies ranged from 2.5 to 5.5 kHz. The filter length (M) was 1,024. The index, i, ran from 0 to M. The sampling frequency (fs) was 33.3 kHz, defined by the step size of the NDFs (30 µs). K is a constant and was chosen to provide unity gain at zero frequency for the corresponding low-pass filter kernel. To avoid a divide-by-zero error, h(i) equaled 2π(−f)K for i = M/2.

Analysis of neural responses.

Final data analysis was done in MATLAB with custom-written routines (MathWorks, Natick, MA). Neuronal responses were measured as changes in spiking frequency (spk/s). Neural responses were analyzed in 100-ms-wide response windows. Response windows were corrected for the neuron’s response latency. Response latency was determined with peristimulus time histograms with 1-ms bin size. The point in time after stimulus onset at which the neuron’s spiking frequency exceeded the response threshold was defined as response latency. The response threshold was given by the spontaneous activity of the neuron plus two times the standard deviation of the spontaneous activity. The number of action potentials recorded during stimulus presentation was corrected by subtracting the spontaneous activity of the neuron to obtain the stimulus-dependent change in the neuron’s spike rate (Δspike rate).

The examined ITDs ranged from −330 µs to 330 µs with a step size of 30 µs. Mean NDFs were computed by averaging the 10–20 single measurements obtained at each ITD. AAr neurons exhibited highly variable spike rates. To remove ITD-uncorrelated noise, NDFs were low-pass filtered by convolving the NDFs with a windowed sinc function that was combined with a Blackman window (Smith 1999) (see Eq. 1, f = 10 kHz, M = 1,024, fs 33.3 kHz). It should be noted that for the low-pass filter the frequency term −f in Eq. 1 changes to f. In the barn owl, ITDs are detected in the nucleus laminaris by cross-correlating periodic, narrowband inputs. The NDFs recorded in the nucleus laminaris and other downstream nuclei exhibit the same sinusoidal periodicity as the narrowband inputs. Because of the periodicity, the ITD information contained by these NDFs should be unaffected by filtering out spectral components that exceed both the barn owl’s hearing range (10 kHz; Konishi 1973) and its phase-locking limit (9 kHz; Köppl 1997).

Modeling neural responses.

We used modeled NDFs to analyze how the combination of carrier and envelope inputs affects the shape of the NDFs and the delay asymmetry measure. NDFs were modeled for neurons with carrier only, envelope only, and mixed inputs. Similar to the filtering process at the cochlea, the carrier and envelope functions were extracted by band-pass filtering a broadband noise stimulus (0.1–25 kHz; Fig. 1, A and B). We modeled the NDFs of solely carrier-driven neurons by cross-correlating stimulus carrier functions similar to those shown in Fig. 1C (xcorr, MATLAB; MathWorks). Two copies of the same carrier (Fig. 1C; car0/car0) were cross-correlated to model the NDF0 (Fig. 2A), while two anticorrelated carrier functions (car0/car180) were cross-correlated to create the NDF180 (Fig. 2A). Anticorrelation was introduced by multiplying the broadband noise by −1 before carrier and envelope functions were extracted by band-pass filtering. The modeled NDFs ranged from −360 to 360 µs with a step size of 10 µs. For solely envelope-driven neurons (Fig. 3B), NDFs were modeled by cross-correlating two envelope functions (Fig. 1C). A blend of the cross-correlation products of the carrier and the envelope functions was used to model the NDFs of neurons with mixed inputs (Fig. 3C). The NDFs of mixed neurons were generated for varying ratios of envelope and carrier contributions (Fig. 4, A–I). Besides the ratio, we also varied the best ITD of the envelope and carrier inputs. The best ITD is defined as the ITD that exhibits the maximum response in an ITD response function like the NDF. The best ITD was manipulated by introducing a temporal delay between the two carrier or envelope signals before cross-correlation. We also generated rectified NDFs to simulate the effect of nonlinear processes like thresholding on the shape of the NDFs and, subsequently, the delay asymmetry (Fig. 3D). Rectification was introduced after cross-correlation by applying a cubic nonlinearity to the NDF functions. NDFs of nucleus laminaris neurons do not exhibit rectification (Christianson and Peña 2006). Consequently, peripheral rectification, before the cross-correlation-like ITD detection in the nucleus laminaris, could be ignored in our model.

Fig. 1.

Noise stimuli. A: broadband white noise as used in the experiments (0.5–25 kHz). B: band-pass filtered noise. Because of filtering at the level of the cochlea, broadband noise stimuli are split into 1/3-octave-wide frequency bands. The filtering produces a periodic carrier and an aperiodic envelope. C: close up of the carrier (car0) and the envelope (env0) of the band-pass filtered noise shown in B. Besides the band-pass noise, the carrier (car180) and envelope (env180) of a 180° phase shifted noise are also shown. The stimulus carrier is phase sensitive. A 180° phase shift causes an inversion of the carrier (compare gray lines). By contrast, the stimulus envelope is unaffected by the phase shift (compare black lines). The envelope is phase invariant.

Fig. 2.

Envelope extraction and delay asymmetry. A: pair of modeled NDFs (NDF0, NDF180). The NDF envelope functions were extracted by smoothing the min and max functions. The min function is given by the lowest response of the NDF pair at each ITD, while the max function represents the highest response at each ITD. The NDF envelope functions were aligned with the local extrema of the 2 NDFs. Shifting the envelope functions did not affect the envelope’s shape or the output of the cross-correlation analysis. B: cross-correlation function of the 2 NDF envelope functions (black line). The upper and lower envelopes were cross-correlated to determine the delay asymmetry. The delay asymmetry is defined as the ITD shift that maximized the anticorrelation between the upper and lower envelope functions. The minimum of the cross-correlation functions gives the ITD shift that maximizes the anticorrelation and thus the delay asymmetry. The gray line shows the cross-correlation function of the min and max functions. The cross-correlation function exhibited an oscillating high-pass element that is a sampling artifact and is due to the fact that we recorded only 2 NDFs (0 and 180°). Note that the 2 cross-correlation functions are similar with the exception of the oscillating high-pass component. Both functions exhibit the minimum at 0 µs.

Fig. 3.

Carrier and envelope elements in NDFs. A: modeled response of a solely carrier-sensitive neuron. The NDF0 function (solid black line) was generated by cross-correlating 2 copies of the same carrier signal (car0/car0), similar to the one shown in Fig. 1, B and C. The NDF180 (dashed gray line), was created by cross-correlating a carrier (Fig. 1C; car0) and its 180° phase-shifted counterpart (Fig. 1C; car180). The black dotted lines represent the envelope functions of the 2 NDFs. The delay asymmetry (delA) and the correlation (r) of the NDF pair are given at top left of each panel. A neuron that is solely driven by the stimulus carrier has a correlation coefficient of −1 and no delay asymmetry. B: modeled response of a solely envelope-sensitive neuron. The functions and values are the same as in A with the exception that the NDF0 and NDF180 were created by cross-correlating the stimulus envelopes (Fig. 1C, black lines; env0 and env180) instead of the carriers. The stimulus envelope is phase invariant. Thus the NDF0 and NDF180 are similar for a solely envelope-driven neuron. The correlation of the 2 NDFs is close to 1. Note that the NDF180 and the 2 NDF envelopes were shifted to allow an unobstructed view on all 4 curves. C: modeled response of a partly envelope-sensitive neuron. The 2 NDFs were created by mixing the NDF functions shown in A and B in equal ratio. The correlation of a carrier and envelope driven neuron is intermediate, while the delay asymmetry is nonzero. D: rectified responses of a solely carrier-sensitive model neuron. The NDFs are rectified versions of the NDFs shown in A. Rectification decreases anticorrelation (r: −0.53 compared with −1 in A) but does not introduce a delay asymmetry (delA: 0 µs). E–H: cross-correlation functions of the 4 modeled neurons (black lines). The cross-correlation of the upper and lower envelopes was used to determine the neuron’s delay asymmetry. The delay asymmetry is defined as the ITD shift that maximizes the anticorrelation between the upper and lower envelope functions, i.e., the minimum of the cross-correlation function. The panels also show the cross-correlation functions of the min and max functions (gray line) (compare Fig. 2B). I–L: DIFCOR functions of the modeled responses shown in A–D. DIFCOR functions are created by subtracting the NDF180 from the NDF0. The DIFCOR represents the phase-sensitive component of the response. M–P: SUMCOR functions of the modeled NDFs. SUMCOR functions are the sum of the 2 NDFs and represent the phase-tolerant response component.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the envelope and its ITD on delay asymmetry. A–I: modeled NDFs with varying carrier and envelope contributions (black line: NDF0; dashed gray line: NDF180). Envelope contributions increases from top (10%) to bottom (30%), while the best ITD of the envelope component increases from left to right (30 µs, 180 µs and, 330 µs). The best ITD is defined as the ITD that elicits the highest response. The best ITD of the carrier component was kept at 30 µs for all modeled NDFs. The delay asymmetry (DA) and the correlation (r) are given at top left of each panel. Upper and lower NDF envelopes are shown as black dotted lines. J–L: cross-correlation functions computed for increasing envelope contributions (10–30% in 5% steps) and varying best ITDs of the envelope component (J: 30 µs, K: 180 µs; L: 330 µs). Darker curves correspond to smaller envelope contributions, and lighter curves correspond to bigger envelope contribution. Solid lines represent the cross-correlation function for the neurons shown in A–I with 10%, 20%, and 30% envelope contributions, while the 2 dashed lines show the cross-correlation functions for neurons with 15% and 25% envelope contributions (NDFs not shown). Note that for all 3 ITD configurations the position of the cross-correlation’s minimum shifts from 0 µs to more extreme values with increasing envelope contribution.

Detection and quantification of envelope contributions.

The detection and quantification of envelope contributions is hindered by thresholding and other neural processes that cause NDFs to be rectified. Christianson and Peña (2006) introduced the rectification index as a measure for the rectification of NDFs. The rectification index can take values between 0 and 1. A rectification index of 0.5 indicates a lack of rectification, while an index of 0 or 1 indicates negative or positive half-wave rectification, respectively (Christianson and Peña 2006). To compute the rectification index, we first normalized the NDFs so that they ranged from 0 to 1. The rectification index was then computed by averaging the responses at the most extreme ITDs (−330 to −300 µs and 300 to 330 µs). The mean rectification index of the NDF0 and NDF180 was used to classify the AAr neurons. All neurons with a rectification index below 0.2 or above 0.8 were classified as strongly rectified and excluded from further analysis.

To identify neurons that represent the ITD of the envelope, Agapiou and McAlpine (2008) introduced the delay asymmetry. They defined the delay asymmetry as the ITD shift that maximized the anticorrelation between the upper and lower envelope functions of a group of NDFs. Note that the NDF envelope functions mentioned here do not correspond to the previously introduced envelope of the acoustic stimulus (compare Fig. 1C, black lines, to Figs. 2–5, black dotted lines). We determined the neuron’s delay asymmetry by cross-correlating the upper and lower envelope functions. The minimum of the cross-correlation function gives the ITD shift that maximizes the anticorrelation between the two envelope functions. The delay asymmetry can take negative or positive values. In our study, positive delay symmetries indicate that the lower envelope had to be shifted toward positive ITDs to maximize anticorrelation, while negative delay asymmetries demanded a shift toward negative ITDs to maximize anticorrelation. To extract the upper and lower NDF envelope functions we first determined the min and max functions. The min function was given by the minimum response of the two NDFs at each ITD, while the max function was given by the maximum response (Fig. 2A). The cross-correlation product of the min/max functions generally exhibited a high-pass element (Fig. 2B). The high-pass element was a sampling artifact. Unlike Agapiou and McAlpine (2008), we recorded NDFs for two instead of eight different phase configurations (NDF0 and NDF180). To remove the sampling artifact, the min/max functions were smoothed before cross correlation with a three-point averaging filter. From here on we refer to the smoothed min/max functions as the NDFs’ lower and upper envelope functions, respectively (Fig. 2A). The cross-correlation product of the two NDF envelopes lacked the previously observed high-frequency sampling artifact (Fig. 2B, black solid line). For the delay asymmetry extraction, the cross-correlation range was limited to ±480 µs. This guaranteed that the two NDF envelope functions overlapped for a range of at least 180 µs.

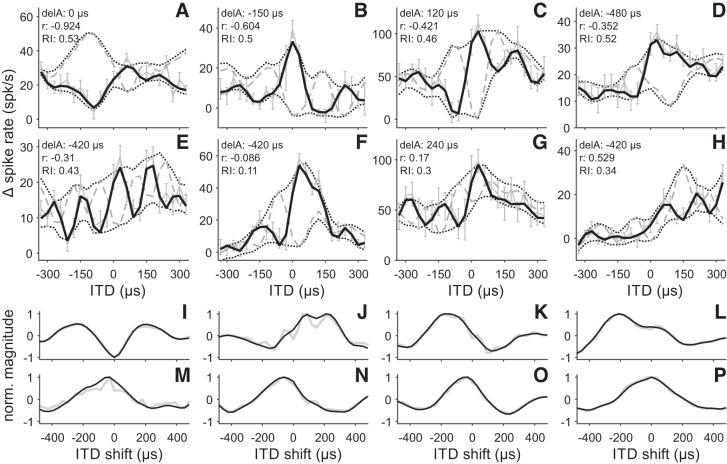

Fig. 5.

Typical NDFs of AAr neurons. A–H: NDFs recorded with correlated (NDF0; black solid lines) and anticorrelated, i.e., 180° phase-shifted (NDF180; gray dashed lines) noise of 8 AAr neurons. NDFs were low-pass filtered at 10 kHz to remove high-frequency noise. For the NDF0, we also included the raw, unfiltered data (light gray lines). Error bars give SE of the change (Δ) in spike rate. Upper and lower NDF envelope functions are shown as black dotted lines. The correlation (r) between the 2 NDFs, the delay asymmetry (delA), and the rectification index (RI) are given at top left of each panel. Note that the correlation of the neurons increases from A to H. I–P: cross-correlation functions of the NDF envelopes shown in A–H (black lines). The position of the cross-correlation’s minimum gives the neuron’s delay asymmetry. Gray lines depict the cross-correlation of the unsmoothed min and max functions (not shown, see Fig. 2).

While the delay asymmetry is a robust indicator of envelope contributions in NDFs, it cannot be used to quantify envelope sensitivity. Following Joris (2003), we used the correlation between the AAr neurons’ responses to correlated (NDF0) and anticorrelated (NDF180) stimuli to quantify their envelope sensitivity. The stimulus envelope is unaffected by changes in the stimulus’s phase (Fig. 1C, black lines). For a purely envelope-sensitive neuron, the NDF0 and the NDF180 will exhibit the same shape (Fig. 3B). The neuron’s response is phase invariant. By contrast, the response of a carrier-sensitive neuron is phase sensitive. The NDF0 and the NDF180 will exhibit an inverted shape (Fig. 3A). We computed the Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient by using MATLAB’s corr function to quantify the phase sensitivity of the neural responses. The correlation coefficient r can take values between −1 and 1. Pure phase-sensitive neurons have a correlation of −1 (Fig. 3A), while pure phase-invariant neurons exhibit a correlation of 1 (Fig. 3B).

Besides the correlation coefficient, we also analyzed DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions to estimate the prevalence of envelope sensitivity. The DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions represent the phase-sensitive and phase-invariant response elements, respectively (Joris 2003). The DIFCOR is computed by subtracting the NDF180 from the NDF0, while the SUMCOR is defined as the sum of the two NDFs (Fig. 3, A–D and I–P). The modulation depth of a function was defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum response, also known as the peak-trough difference. The peak-trough difference of the SUMCOR and DIFCOR functions was given as a percentage of the maximum possible peak-trough difference, which in turn was set by the sum of the peak-trough differences of the NDF0 and NDF180. Comparing the peak-trough difference of the DIFCOR and SUMCOR function allowed us to estimate the relative contributions of the carrier and the envelope to a neuron’s ITD representation.

Phase difference and power spectra were used to assess whether phase invariance and phase sensitivity were restricted to distinct spectral ranges in the AAr. Phase and power spectra of the NDFs were calculated with a step size of 256 Hz using a discrete Fourier transformation algorithm (fft, MATLAB; MathWorks). The phase difference spectra were then computed by subtracting the phase spectra of the NDF180 from the phase spectra of the NDF0. A phase difference of 0 or 360° indicates phase invariance, while a phase difference of ±180° demonstrates phase sensitivity. The phase difference spectra of all neurons that showed envelope elements in their response were averaged to create the mean phase difference spectrum. Not all frequencies of a phase spectrum carry meaningful information. If the energy in a frequency band is low, the phase information of that band will be prone to noise and become random. To avoid noise in the mean phase difference spectrum, low-energy frequency bands were ignored for the averaging process. Frequency bands were considered to be low energy if the corresponding power spectrum exhibited a value below one-third of the power spectrum’s maximum magnitude (see Fig. 10, A–H, black dotted lines). For each frequency (f), the single phase difference spectra (ϕ) were decomposed into their sine and cosine elements. After averaging across all neurons (n = number of neurons), the mean sine and cosine elements were recomposed with the atan2 function (MATLAB; MathWorks) to create the mean phase difference. The variance in the mean phase difference was assessed by its vector strength (r).

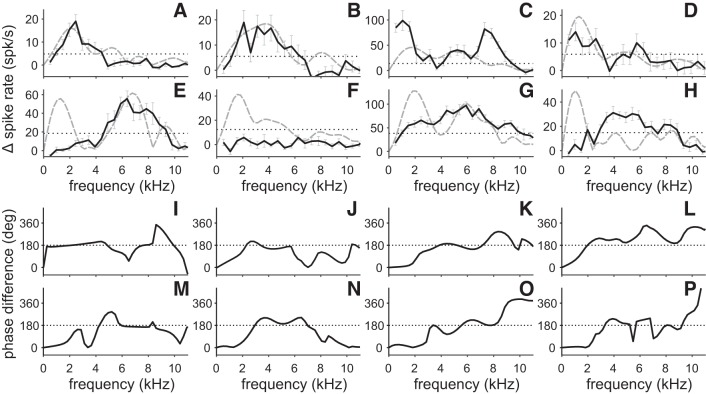

Fig. 10.

Frequency-response functions and phase difference spectra. A–H: frequency-response functions of the 8 example neurons shown in Fig. 5 (black solid lines). Error bars give SE of the change in spike rate. Gray dashed lines represent the power spectrum of the neurons’ NDF0. Power and phase spectra were computed with a discrete Fourier transformation. The 1/3 magnitude level of the frequency spectra is marked by the black dotted line. Only those parts of the power spectrum that exceeded the 1/3 magnitude threshold were considered to carry energy. I–P: phase difference spectra of the same 8 example neurons (black lines). Phase difference spectra were created by subtracting the phase spectrum of the NDF180 from the phase spectrum of the NDF0. A phase difference of ±180 indicates phase sensitivity (dotted lines), while a phase difference of 0 or 360 indicates phase invariance.

| (2) |

The vector strength is a unitless measure of variance. If the phase difference of the examined neurons is highly variable the vector strength will be close to 0, while a vector strength of 1 indicates that all neurons exhibited the same phase difference.

RESULTS

The analyzed data set consists of 146 single AAr neurons recorded from seven adult barn owls of both sexes. Only neurons that were significantly ITD tuned (Kruskal-Wallis test, P ≤ 0.05) were included in the analyzed data set. For 21 of the 146 neurons, we also recorded responses to stimulation with high-pass filtered noise.

Identifying envelope-sensitive responses.

In 2009, Vonderschen and Wagner reported that NDFs of AAr neurons are asymmetrically shaped (compare Fig. 4, B, E, and H, black lines). Their results indicated that the asymmetry in the NDF was due to a combination of a low-pass and a high-pass element with different best ITDs. The periodicity in the high-pass element implied that it represents the ITD of the carrier of high-frequency sounds. The low-pass element in the NDF, however, could derive from either the carrier of a low-frequency sounds or the envelope of a complex sound that falls within the barn owl’s hearing range (0.1–10 kHz). We analyzed the phase sensitivity of ITD representation in AAr neurons to assess whether the reported asymmetry is based on a combination of carrier and envelope inputs.

Because of the sharp spectral selectivity of cochlea hair cells, acoustic stimuli are processed in narrow frequency bands in the barn owl’s early auditory pathway. This band-pass filtering of broadband inputs at the cochlea introduces a periodic carrier and an aperiodic envelope (Hartmann 1997) (Fig. 1, A and B). The carrier of an acoustic stimulus is phase sensitive. A 180° phase shift of the stimulus leads to an inversion of the carrier (Fig. 1C). By contrast, the envelope is phase invariant and thus similar in both phase configurations (Fig. 1C). By analyzing the phase sensitivity of neural responses, the contribution of the carrier and the envelope to the representation of ITDs might be estimated (Joris 2003). We recorded NDFs for two different phase configurations of the stimulus: correlated and anticorrelated. For the correlated configuration, neural responses to varying ITDs of an otherwise diotic noise stimulus were recorded (NDF0). For the anticorrelated configuration (NDF180), the signal presented to one of the two ears was inverted, introducing an additional ITD-independent phase shift of 180°. ITDs are computed in the nucleus laminaris by comparing the inputs to the two ears in a cross-correlational process (Albeck and Konishi 1995). As a consequence, the change in the IPD due to an inversion of one of the two inputs is expected to change the responses of the ITD-detecting neurons in the nucleus laminaris and all downstream neurons, if these are sensitive to changes in the carrier (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, the responses of neurons that only represent the ITD of the envelope will be unaffected by a change in the IPD (Fig. 3B). From here on, we refer to neurons whose NDFs change because of changes in the carrier phase as “carrier sensitive,” while neurons that exhibit phase-invariant elements in their response are called “envelope sensitive.”

The NDF0 and the NDF180 of an ideal carrier-sensitive neuron are horizontal mirror images of each other (Fig. 3A). By contrast, solely envelope-sensitive neurons exhibit identical NDFs for the correlated and anticorrelated stimulus conditions (Fig. 3B). For neurons with a mixed sensitivity, the similarity between the NDFs depends on the ratio of carrier and envelope contributions (Fig. 3C). The similarity of two functions can be quantified by computing their correlation. Joris (2003) used this method to quantify carrier and envelope contributions in ITD-sensitive neurons in the midbrain of cats.

Joris (2003) also computed DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions to separate phase-sensitive and phase-invariant responses, respectively. The DIFCOR is the difference between the response to the correlated stimulus, NDF0, and the response to the anticorrelated stimulus, NDF180, while the SUMCOR is the sum of the two responses (Joris 2003). Neurons with carrier contributions will exhibit phase-sensitive responses and thus a nonflat DIFCOR function (Fig. 3, I, K, and L). Solely envelope-sensitive neurons, on the other hand, will exhibit a flat DIFCOR function (Fig. 3J). The analysis of the SUMCOR function is more complicated. While it still holds true that all neurons with envelope elements exhibit a signal in their SUMCOR function (Fig. 3, N and O), it is not necessarily true that all neurons that lack envelope elements will have a flat SUMCOR function (Fig. 3P).

Correlation coefficients as well as DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions are good tools to quantify phase sensitivity and phase invariance. However, both are limited when it comes to identifying envelope contributions, since not all phase-invariant responses are due to the stimulus envelope. Albeck and Konishi (1995) showed that neurons in the external nucleus of the barn owl’s inferior colliculus (IC) exhibit a nonlinear relationship between interaural correlation and spike rate, most likely due to thresholding of neural inputs from upstream nuclei and nonlinear conversion of membrane potentials (Peña and Konishi 2001, 2002). Nonlinear processes like thresholding introduce phase-invariant response elements. Figure 3D shows the rectified versions of the modeled NDFs presented in Fig. 3A. Despite the lack of envelope contributions, the rectified NDFs are no longer perfectly anticorrelated (Fig. 3D, solid black line and dashed gray lines). Their correlation coefficient r rises to −0.53, and the SUMCOR function is no longer flat (compare Fig. 3, M and P).

Agapiou and McAlpine (2008) introduced the delay asymmetry as a tool for identifying envelope elements in NDFs. In the barn owl, the delay asymmetry is a reliable detector of envelope elements. The only other potential source—a conversion of outputs from ITD-sensitive neurons in upstream nuclei with characteristics phases of 0 and 0.5 (Agapiou and McAlpine 2008)—can be excluded because of a general absence of neurons with characteristic phases of 0.5 in the barn owl’s auditory pathway (Christianson and Peña 2006; Fischer and Konishi 2008; Takahashi and Konishi 1986; Vonderschen and Wagner 2012). Agapiou and McAlpine (2008) defined the delay asymmetry as the ITD shift that maximized the anticorrelation between the upper and lower envelope functions of a group of NDFs. The delay asymmetry was derived by cross-correlating the two envelope functions. The position of the cross-correlation’s minimum determined the delay asymmetry of the neuron (Fig. 2B and Fig. 3, E–H, black lines). We refer to the two envelope functions as NDF envelopes to avoid confusion with the previously introduced envelope of the auditory stimulus (Fig. 1, B and C). The upper and lower NDF envelope functions were extracted by calculating the NDFs’ min and max functions (Fig. 2A). The min function is given by the lowest response of the NDFs at each ITD, while the max function represents the maximum response of the NDF pair at each ITD. The min and max functions were smoothed to create the upper and lower envelope functions, respectively (Fig. 2A). For a solely carrier-sensitive neuron, the two NDF envelopes are perfectly anticorrelated (Fig. 3A). The cross-correlation function exhibits a minimum at 0 ITD (Fig. 3E). By contrast, the NDF envelope functions of envelope-sensitive neurons are highly correlated (Fig. 3, B and C). The cross-correlation functions of these neurons exhibit a maximum at 0 ITD, and thus their delay asymmetry deviates from 0 (Fig. 3, F and G). Rectification, however, does not affect the anticorrelation of the two NDF envelopes (Fig. 3D). Rectified NDFs exhibit a delay asymmetry of 0, despite their phase-invariant response element (Fig. 3H).

The delay asymmetry is a very sensitive measure and can detect even small envelope contributions. However, the exact size of the delay asymmetry depends not only on the size of the envelope element but also on other factors. The spectral composition of the carrier input, the width of the envelope element, which in turn depends on the spectro-temporal structure of the stimulus, and the best ITD of both the carrier and the envelope contributions affect the measured delay asymmetry. Figure 4, A–I, show the modeled NDFs of nine neurons that are carrier- as well as envelope sensitive. Both the size (rows: 10–30%) and the best ITD (columns: 30, 180, and 330 µs) of the envelope contributions were varied. The best ITD of the carrier was kept at 30 µs for all nine neurons. It is important to note that even though the envelope elements of all neurons in a row have the same size (Fig. 4, A–C: 10%, D–F: 20%, and G–I: 30%) the delay asymmetries vary widely. The wide range of delay asymmetry in the modeled neurons demonstrates the influence of the best ITD. If the carrier and the envelope element exhibit the same best ITD (Fig. 4, left), the change in the delay asymmetry with increasing envelope contribution is rather abrupt. In the example, the minimum of the cross-correlation functions switches from ~0 to −200 µs when the envelope contribution increases from 20% to 25% (Fig. 4J). If carrier and envelope contributions have different best ITDs, the changes in the delay asymmetry are more complex and depend on the difference between the best ITD of the carrier and the best ITD of the envelope. The delay asymmetry, i.e., the minimum of the cross-correlation function, can either change abruptly (Fig. 4L) or increase smoothly from 0 to its maximum (Fig. 4K). However, the switch from 0 to nonzero delay asymmetries always happens at lower envelope contribution if carrier and envelope do not exhibit the same best ITD (Fig. 4J: 20–25% compared with Fig. 4K: 10–15% and Fig. 4L: 15–20%). Consequently, the delay asymmetry is an even more sensitive measure for envelope contributions if the best ITDs of the carrier and the best ITD of the envelope do not match.

The examined neurons were classified as envelope sensitive on the basis of their delay asymmetry. The temporal precision of the cross-correlation analysis was limited by the step size of the underlying NDFs (30 µs). To avoid misclassification, only neurons with a delay asymmetry that exceeded ±30 µs were considered to be envelope sensitive. It should be noted that a delay asymmetry between −30 and 30 µs does not rule out the possibility that these neurons have envelope contributions in their responses.

In our study, we observed the same asymmetry in the responses of AAr neurons as reported by Vonderschen and Wagner (2009). Typically, the neural response was higher for contralateral ITDs (>0 µs) (Fig. 5, C–H, black solid lines). Only a few neurons exhibited no asymmetry at all (Fig. 5A) or a higher ipsilateral spike rate (Fig. 5B). A similar trend could be observed for the NDF180. Even though all neurons exhibited a clear change in their response due to the presentation of anticorrelated noise (Fig. 5, black solid and gray dashed lines), most NDF180 still showed a higher spike rate for contralateral ITDs (Fig. 5, C–E, G, and H). The responses of most AAr neurons were composed of a periodic high-pass element and an additional low-pass element. The high-pass element was phase sensitive. Typically, the local maxima of the NDF0 would coincide with the local minima of the NDF180 and vice versa (Fig. 5, A–H). The low-pass element, however, was often phase invariant. The responses of the five neurons shown in Fig. 5, C–E, G, and H, exhibit a high contralateral response for both the NDF0 and the NDF180. In addition, the neuron presented in Fig. 5B exhibited high responses for both NDFs on the ipsilateral side (negative ITDs).

To analyze envelope sensitivity in the AAr we first computed the delay asymmetry to identify and separate neurons with envelope contributions. Even though the delay asymmetry was missing or small in some neurons (Fig. 5, A and I), generally AAr neurons exhibited prominent delay asymmetries (Fig. 5, B–H and J–P). One hundred thirty-seven of the 146 analyzed neurons (93%) had a delay asymmetry that exceeded the threshold used for detecting envelope contributions (Fig. 6A). In addition to the nine neurons with a delay asymmetry between −30 and 30 µs, five other neurons were removed from the data set. The NDFs of these neurons were highly rectified. Strong rectification can be an indication of nonlinear processes like thresholding. Thresholding and other processes complicate the detection and quantification of envelope contributions by adding phase-invariant elements to NDFs that are independent of the stimulus envelope. Furthermore, the NDF envelope of strongly rectified NDFs often exhibited a small modulation depth (lower NDF envelope in Fig. 3D and Fig. 5F). The small modulation depth makes the extraction of the NDF envelope and the subsequent cross-correlation prone to neural noise. All neurons with a rectification index below 0.2 or above 0.8 were classified as negative or positive rectified, respectively. Most AAr neurons had a rectification index between 0.2 and 0.66, with a median of 0.423 (Fig. 6B). The five neurons that exhibited a rectification index below 0.2 were removed from the data. For the remaining 132 AAr neurons, envelope and carrier sensitivity was assessed by analyzing the phase-sensitive and phase-invariant response elements.

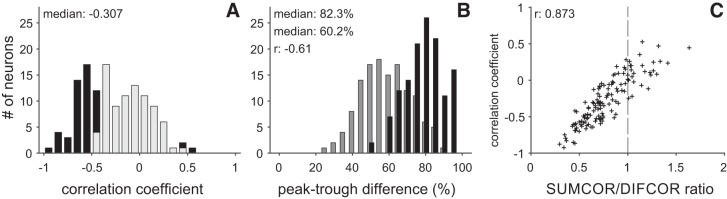

Fig. 6.

Identification of envelope-sensitive neurons. A: distribution of delay asymmetries. Gray dashed line marks the 30 µs cutoff used for classifying neurons. Neurons with a magnitude of delay asymmetry that exceeded 30 µs were classified as envelope sensitive; 137 of the 146 neurons exhibited a magnitude of delay asymmetry of at least 60 µs. B: distribution of rectification indexes. Most neurons exhibited intermediate rectification indexes between 0.2 and 0.6, with a population median of 0.423. Gray dashed line in the distribution of the rectification indexes marks the 0.2 threshold. The 5 neurons that exhibited a rectification index below 0.2 and the 9 neurons with a magnitude of delay asymmetry below 60 µs were removed from further analysis. The remaining 132 neurons of the data set carried envelope-sensitive elements in their responses.

Quantifying phase-sensitive and phase-invariant responses.

The delay asymmetry is an unsuitable tool for quantifying envelope sensitivity. The size of the envelope element does not correlate with the delay asymmetry (Fig. 4). Even small envelope contributions can lead to significant delay asymmetries (Fig. 4, B, E, and F). Thus the delay asymmetry was used to identify envelope-sensitive neurons but not to assess the extent of the envelope contributions. Instead, we measured and quantified the phase-invariant response elements in the NDFs to assess the envelope inputs. It is important to remember that the usefulness of this analysis relies on a prior identification of envelope-sensitive neurons with no or only small rectification in their NDFs. As mentioned above, nonlinear processes could potentially introduce phase-invariant response elements that are independent of the stimulus envelope. These elements could be interpreted as envelope responses. An initial selection of envelope-sensitive neurons based on their delay asymmetry and rectification index is therefore essential to avoid this problem.

Since the envelope of an acoustic stimulus is not affected by a change of the stimulus phase (Fig. 1C), its contribution to neural responses is also not affected by changes in the stimulus phase (Fig. 3, B and C). The phase invariance of a neuron’s response can be measured by calculating the correlation between two NDFs with opposing phase configuration (Joris 2003). We calculated the correlation between the NDF0 and the NDF180 by computing Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient. For a solely envelope-sensitive neuron, the two NDFs exhibit an anticorrelated shape (Fig. 3A). The corresponding correlation coefficient is −1, indicating phase sensitivity. By contrast, envelope-sensitive neurons exhibit phase-invariant NDFs (Fig. 3B) and their correlation coefficient is 1. Neurons with both carrier and envelope contributions have a mixture of phase-sensitive and phase-invariant responses, which causes the correlation coefficient to be intermediate (Fig. 3C).

The majority of the AAr neurons exhibited a negative correlation coefficient (Fig. 5, A–F), while only a small subset showed positive correlation coefficients (Fig. 5, G and H). The correlation coefficients in the population ranged from −0.924 to 0.529 with a median of −0.307 (see Fig. 8A). Two neurons showed a significant positive correlation between the NDF0 and the NDF180 (Fig. 8A; correlation >0). By contrast, 47 neurons exhibited a significant negative correlation between the two NDFs and were classified as phase sensitive (Fig. 8A; correlation <0). Significantly negative correlations demonstrate that the neuron’s response is dominated by phase-sensitive elements, while significantly positive correlations indicate a predominance of phase-invariant elements. An intermediate, nonsignificant correlation coefficient could be due to either a combination of phase-sensitive and phase-invariant elements or noise in the recorded NDFs. Noise decorrelates the two NDFs artificially. This issue was addressed by analyzing only neurons that were significantly tuned to ITDs (see first paragraph of results).

Fig. 8.

Phase sensitivity and envelope contributions. A: distribution of correlation coefficients. Significant coefficients are shown in black (Pearson’s r, P < 0.05). Nonsignificant correlation coefficients are shown in light gray. B: distribution of peak-trough differences of the DIFCOR (black) and SUMCOR (gray) functions. The DIFCOR functions exhibit a significantly higher peak-trough difference than the SUMCOR functions (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.001). The peak-trough differences of the 2 functions were negatively correlated (r: −0.61; Pearson’s r, P < 0.001). C: correlation between the correlation coefficient and the SUMCOR-to-DIFCOR ratio (SUMCOR/DIFCOR). SUMCOR/DIFCOR was calculated by dividing the peak-trough difference of the SUMCOR by the peak-trough difference of the DIFCOR function. A SUMCOR/DIFCOR above 1 indicates an envelope-dominated response, while a ratio below 1 corresponds to a carrier-dominated response (dashed gray line). Correlation coefficient and SUMCOR/DIFCOR were significantly correlated (r: 0.873, Pearson’s r, P < 0.001).

The results of the correlation analysis indicated that the ITD representation in the AAr is dominated by phase-sensitive elements (median r: −0.307; Fig. 8A). The correlation analysis, however, lacks the possibility of a differentiated assessment. The entire information in the NDFs is condensed to a single value. To analyze phase-sensitive and phase-invariant responses separately, we computed the DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions, respectively (Joris 2003). The DIFCOR is defined as the difference in response between the NDF0 and the NDF180. The DIFCOR represents the phase-sensitive responses. The SUMCOR is given by the sum of the two NDFs, and it represents the phase-invariant response elements.

Figure 7 shows the DIFCOR (Fig. 7, A–H) and SUMCOR (Fig. 7, I–P) functions of the same eight neurons presented in Fig. 5. Both DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions were normalized to their maximum peak-trough difference. The maximum peak-trough difference was given by the summed peak-trough difference of the NDF0 and the NDF180. The normalization step allowed an easy comparison of the DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions even across neurons with significantly different response magnitudes (compare Fig. 5, A–H). Most DIFCOR functions exhibited a prominent oscillatory shape with steep slopes (Fig. 7, A–H). In comparison, SUMCOR functions were typically dominated by a low-pass element and exhibited only a small oscillatory high-pass element (Fig. 7, I–P), resulting in more gentle slopes. We used the peak-trough difference of the DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions to assess carrier and envelope contribution, respectively. The DIFCOR functions typically exhibited a higher peak-trough difference than the SUMCOR functions (Fig. 7, A–G and I–O). In some cases, it even exceeded the SUMCOR’s peak-trough difference by a factor of 3 or higher (Fig. 7, A and I). Only a minor subset of neurons exhibited a higher peak-trough difference for the SUMCOR function (Fig. 7, H and P). The same trend observed in single neurons was also apparent in the distributions of the peak-trough differences (Fig. 8B). The DIFCOR functions exhibited a median difference of 82.3%, while the SUMCOR functions had a median peak-trough difference of 60.2%. The difference between the two distributions was highly significant (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.001).

Fig. 7.

DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions. A–H: DIFCOR functions of the same AAr neurons shown in Fig. 5. The DIFCOR was created by subtracting the NDF180 from the NDF0. It represents the phase-sensitive component of the NDFs. I–P: SUMCOR functions of the neurons shown in Fig. 5 (black dashed lines). SUMCOR functions are the sum of the 2 NDFs and represent the phase-invariant response component. DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions were normalized by dividing them by their maximum possible peak-trough difference. The maximum possible peak-trough difference of a neurons is set by the sum of the peak-trough differences of its NDF0 and NDF180. The peak-trough difference (PT) and the best ITD of the DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions are given at top left of each panel. The best ITD of a function is given by the ITD that elicits the highest response. SUMCOR functions were low-pass filtered to remove high-pass components in the response (gray lines) before determination of best ITD. The high-pass artifact arises because SUMCOR and DIFCOR functions are computed from a set of NDFs with only 2 different phase configurations, 0 and 180° phase-shifted.

Theoretically, both the DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions can exhibit a high normalized peak-trough difference close to 1. However, the neurons in our data set exhibited a negative correlation. Neurons with a small peak-trough difference in the SUMCOR generally exhibit a high peak-trough difference in their DIFCOR function and vice versa (r = −0.61, Pearson’s r, P < 0.001). For each neuron, we computed the ratio of the SUMCOR and DIFCOR peak-trough difference to estimate whether its response was dominated by phase-sensitive (carrier) or phase-invariant (envelope) inputs. If a neuron’s response is mostly phase invariant, its SUMCOR function will exhibit a higher peak-trough difference than its DIFCOR function and the SUMCOR-to-DIFCOR ratio will be above 1. If a neuron is predominantly phase sensitive, the SUMCOR-to-DIFCOR ratio will be below 1. The SUMCOR-to-DIFCOR ratio of the AAr neurons was highly correlated to the correlation coefficient of the NDFs, demonstrating that both measures can provide similar results (r = 0.873, Pearson’s r, P < 0.001; Fig. 8C). Neurons with predominantly phase-sensitive inputs are separated from neurons with predominantly phase-invariant inputs by the gray dashed line in Fig. 8C. Most neurons had a prevalence of phase-sensitive inputs as indicated by SUMCOR-to-DIFCOR ratios below 1 (Fig. 8). It is noteworthy that the population of AAr neurons was not divided into a predominantly phase-sensitive and a predominantly phase-invariant group but formed a continuum.

In summary, the majority of neurons exhibited both phase-sensitive and phase-invariant responses. In general, the responses of AAr neurons were more phase sensitive than phase invariant, as indicated by the distributions of both the coefficient of correlation and the peak-trough differences. However, the results on the DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions demonstrate that most AAr neurons have also a phase-invariant response element. Thus both the ITD of the signal carrier and the ITD of the envelope are represented in the AAr.

Vonderschen and Wagner (2009) reported that NDFs in the AAr are composed of two elements with different best ITDs. Thus we analyzed whether the phase-sensitive and phase-invariant responses we observed in the AAr exhibit different best ITDs. The best ITD was directly extracted from the DIFCOR functions, while the SUMCOR functions were smoothed to remove the oscillating high-frequency element before the detection of the best ITD (Fig. 7, I–P). On the level of the population, the best ITDs of the DIFCOR and SUMCOR showed a similar distribution with a preference for contralateral ITDs (ITD > 0 µs). The two distributions peaked at small ITDs close to 0 (Fig. 9A). However, the analysis of the ITD magnitude showed that the SUMCOR functions exhibit significantly larger best ITDs than the DIFCOR functions (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.001). The correlation between the best ITD of the SUMCOR and the best ITD of the DIFCOR was low (r: 0.27). Furthermore, single neurons often showed clear offsets between the best ITD of the DIFCOR and the best ITD of the SUMCOR (Fig. 7). Thus we computed the differences between the best ITD of the two functions for all 132 neurons. The distribution of the ITD differences was broad, with a maximum value of 660 µs and a median of 90 µs (Fig. 9B). Eighty-eight of the 132 neurons (66.7%) exhibited a difference of at least 60 µs, indicating that AAr neurons not only represent the ITD of both the carrier and the envelope but also represent at least two inputs with different best ITDs.

Fig. 9.

Best ITD of DIFCOR and SUMCOR. A: distribution of the best ITDs of the DIFCOR (black bars) and SUMCOR (gray bars) functions. The best ITD is defined as the ITD that elicits the highest response. Both DIFCOR and SUMCOR exhibit mostly positive best ITDs with a peak close to 0. The SUMCOR functions have significantly bigger best ITDs than the DIFCOR functions (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.001). The best ITDs of the 2 functions are only weakly correlated (r = 0.27, Pearson’s r, P < 0.001). B: distribution of ITD differences. The best ITD difference is given by the absolute difference between the best ITD of the DIFCOR and the best ITD of the SUMCOR. The majority of AAr neurons (88 of 132) exhibited a best ITD difference of at least 60 µs.

Spectral decomposition of carrier and envelope contributions.

After we found evidence that AAr neurons represent the ITD of the stimulus envelope, we decided to examine whether the envelope sensitivity was restricted to a certain spectral range. We recorded frequency-response functions and computed the power and phase spectra with a discrete Fourier transformation algorithm. Figure 10, A–H, show the NDF0 power spectrum and the frequency-response functions of the eight example neurons introduced in Fig. 5. Only 103 of the 146 AAr neurons showed significant responses to tonal stimuli (Kruskal-Wallis test, P ≤ 0.05). Most of the 103 AAr neurons that responded to tonal stimuli had broadly tuned frequency-response functions (Fig. 10, A, B, E, G, and H). Interestingly, 35% of the 103 neurons exhibited bimodal frequency response functions like the one presented in Fig. 10, C and D. The majority of the AAr neurons showed an apparent mismatch between their frequency-response curves and their NDF power spectra. Besides the 43 neurons that completely lacked response to tonal stimuli, 41 of the 103 frequency-tuned neurons also exhibited a prominent difference between the NDF power spectra and the recorded frequency-response functions. The difference between the frequency-response functions and the power spectra was typically restricted to frequencies below 3 kHz (Fig. 10, C, E, G, and H).

The observed mismatch between the frequency-response functions and the power spectra in combination with the previously mentioned asymmetric shape of most AAr responses led us to the hypothesis that the low-pass element in the NDFs represents the ITD of the envelope instead of the carrier’s ITD. This would explain why these neurons did not respond to low-frequency tones, despite the low-frequency element in their NDF power spectrum. An envelope contribution would add a low-frequency element to the NDFs but would not appear in the frequency-response function, since tonal stimuli lack envelopes.

We computed phase difference spectra to examine whether the low-pass element in the NDF was indeed due to the stimulus envelope. Phase difference spectra were computed by subtracting the phase spectrum of the NDF180 from the phase spectrum of the NDF0. A phase difference of ±180° indicates phase sensitivity, while a phase difference of 0 or ±360° indicates phase invariance. Figure 10, I–P, shows the phase difference spectra of our eight example neurons. The first neuron (Fig. 10I) exhibited a constant phase difference of ±180° between 256 Hz and 8 kHz with a short interruption at ~6.5 kHz. The phase difference of the seven other neurons was either close to 0 (Fig. 10, K and M–P) or increased slowly from 0 to 180° (Fig. 10, J and L) at frequencies below 2.5 kHz. For frequencies between 3 and 7 kHz, most neurons exhibited an extended range of phase differences around ±180° (Fig. 10, I–P). Note that the only neuron with a constant 180° phase difference is the neuron that lacked envelope contribution in its NDF (delay asymmetry between −30 and 30 µs) (compare Fig. 5A and Fig. 10I).

The phase difference spectra of all 132 envelope-sensitive neurons were averaged to create the mean phase difference spectrum shown in Fig. 11A. To compute the mean spectrum, we used only those sections of the 132 phase spectra that exhibited energy in the corresponding sections of the power spectrum (Fig. 10, A–H). The energy threshold was chosen to be one-third of the power spectrum’s maximum (Fig. 10, A–H). For example, the power spectrum of the neuron shown in Fig. 10B exceeded the threshold between 1 and 6 kHz. Thus only the range from 1 to 6 kHz of the neuron’s phase spectrum was used for the averaging process. In frequency bands with low or no energy, the phase information is prone to noise and therefore becomes random. By removing low-energy frequency ranges before averaging, we minimized the noise in the mean phase difference spectrum. For each frequency, the remaining phase differences (Fig. 11, B–D) were split into a sine and a cosine component. The averaged sine and cosine components were recomposed to get the mean phase difference vector and its vector strength (Fig. 11, B–D). The mean phase difference is represented by the angle of the vector, while the vector’s length represents the vector strength. The vector strength can take values between 0 and 1. A vector strength of 0 indicates a random phase difference, while a vector strength of 1 indicates that all analyzed neurons exhibited the same phase difference (see materials and methods). The vector strength was high at 0.26 and 4.69 kHz (Fig. 11, B and C, vector strength: 0.582) because AAr neurons exhibited a similar phase difference at these frequencies (Fig. 11, B and C). At 8.59 kHz, the vector strength was close to 0, indicating that the phase difference varied across the population at this frequency (Fig. 11D).

Fig. 11.

Mean phase difference spectrum. A: the mean phase difference spectrum (black line) was created by averaging the phase difference spectra of the 132 AAr neurons that exhibited envelope sensitivity. Only the section of the phase spectrum where the neuron’s power spectrum reached at least 1/3 of its maximum magnitude was used for averaging (see dotted lines in Fig. 10). Gray line shows the vector strength of the averaged phase spectrum. B–D: polar plots show the neurons’ phase differences (gray plus signs) at 3 different frequencies (black x-signs in A). The direction of the black line in the center of each polar plot gives the mean phase spectrum at these frequencies, while its length corresponds to the vector strength. The vector strength is a measure for the similarity of the phase difference spectrum across the population. A vector strength of 1 indicates that all neurons have the same phase difference, while a vector strength of 0 indicates a lack of correlation across the population. Values for the averaged phase difference (avg) and the vector strength (VS) are shown at top of each panel.

In the examined AAr neurons, the mean phase difference was close to 0° for frequencies below 1.5 kHz (Fig. 11A). Between 2 and 3 kHz the phase difference changed from 0 to 180°, indicating a shift from phase invariant to phase sensitive. For frequencies above 8 kHz, the phase difference was more variable and varied between 70° and 180°. The vector strength was strongest for frequencies below 500 Hz and exhibited an additional maximum between 3 and 5 kHz (Fig. 11A). At 2 kHz, the vector strength exhibited a minimum that coincides with the change in the mean phase difference from 0 to 180°. Above 5 kHz, the vector strength decreased slowly until it reached its absolute minimum at 8.6 kHz. The minimum at 8.6 kHz was accompanied by a rapid change in the phase difference spectra (Fig. 11A). The low vector strength indicated that the mean phase difference is random at these frequencies and could take any value (0.054; Fig. 11D). The slow decline in vector strength for frequencies above 5 kHz is in accordance with studies on phase-locking in the periphery of the barn owl’s auditory pathway. Köppl (1997) reported a decline in the vector strength of nerve fibers with increasing characteristic frequency. It is not surprising that a weakened phase-locking in high-frequency (>5 kHz) nerve fibers affects the representation of the stimulus carrier (and its phase) in downstream neurons with high-frequency inputs (Fig. 10, B–E, G, and H).

The analysis of the spectral distribution of carrier and envelope sensitivity revealed that the high-pass element (3–8 kHz) of the NDFs was mostly carrier driven, while the low-pass element (<2 kHz) was dominated by phase-invariant envelope contributions. Up to this point, we have only analyzed the spectral distribution of phase sensitivity and phase invariance. The frequency range of the input that actually conveys the phase-invariant envelope element is examined in the final section.

Responses to high-pass filtered noise.

AAr neurons with significant envelope contributions in their ITD representation exhibited a phase-invariant low-pass element. Even though it was obvious at this point that the envelope element caused the phase invariance, it remained unclear whether it was based on low- or high-frequency inputs. Sensitivity to the envelope of both low- and high-frequency sounds can introduce a phase-invariant, low-pass element in the measured NDF. We recorded neural responses to high-pass filtered noise stimuli in a subset of 21 neurons to analyze the frequency range that carried the envelope inputs. The cutoff frequencies for the high-pass filtered stimuli varied between 2.5 and 5.5 kHz and depended on the frequency-response function of the individual neurons. Figure 12 shows the NDF0, NDF180, and their corresponding NDF envelopes of four example neurons (compare Fig. 5, A, D, F, and H, with Fig. 12, A, B, C, and D). All four neurons had a delay asymmetry that exceeded ±30 µs, indicating envelope sensitivity (Fig. 12, E–H). However, the response shown in Fig. 12A exhibits a change in spiking frequency of <1 spike per stimulus presentation. Thus this neuron and two additional neurons were removed because of their weak responses (<10 spk/s). The limitation to high-frequency sounds sometimes altered the shape of the NDFs (Fig. 12D). However, only one neuron lost its envelope component completely when stimulated with high-frequency noise. The remaining 17 neurons exhibited a magnitude in the delay asymmetry of at least 60 µs when stimulated with either broadband or high-pass filtered noise and were thus classified as envelope sensitive (Fig. 13A). The three example neurons shown in Fig. 12, B–D, exhibited a substantial low-pass element in their power spectrum (<3 kHz; Fig. 12, J–L), even though the stimulus noise did not exhibit any power below 2.5 kHz. Suspecting that the low-pass element was due to envelope contributions, we analyzed the phase sensitivity of the responses. Like the broadband NDFs, responses to high-pass filtered stimuli were predominantly phase sensitive. Typically, correlation coefficients were negative (Fig. 12, A–D). They ranged from −0.821 to 0.054, with one outlier at 0.516 (Fig. 13B). The median correlation coefficient was −0.133. A similar trend was apparent in the DIFCOR and SUMCOR data. The peak-trough differences of the SUMCOR functions (Fig. 13C) were significantly lower than the peak-trough differences of the DIFCOR functions (P < 0.01; Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Thus both the correlation coefficient and the DIFCOR/SUMCOR analysis demonstrated that the phase-sensitive inputs dominated the responses of AAr neurons when stimulated with high-frequency noise. Yet single neurons could exhibit prominent phase-invariant elements in their response (Fig. 12B).

Fig. 12.

AAr responses to high-pass filtered noise. A–D: NDF0 (black lines) and NDF180 (gray dashed lines) of the 4 neurons shown in Fig. 5, A, D, F, and H. NDFs were recorded using high-pass filtered noise stimuli. Upper and lower envelope functions are shown as black dotted lines. Delay asymmetry (delA) and correlation coefficients (r) are given at top left of each panel. The cutoff frequency for the high-pass noise stimuli was chosen individually for each neuron depending on its frequency response function (compare Fig. 10). Cutoff frequencies ranged from 2.5 to 5.5 kHz. E–H: cross-correlation functions of the NDF envelope functions shown in A–D (black lines). The position of the cross-correlation’s minimum determines the neurons delay asymmetry. Gray lines depict the cross-correlation functions of the min and max functions (not shown; see Fig. 2). I–L: power spectra of the NDF0 shown in A–D. Power spectra were computed with fast Fourier transformation algorithm.

Fig. 13.

Envelope contributions in responses to high-pass filtered stimuli. A: distribution of delay asymmetries for 18 of the 21 NDF pairs recorded with high-pass filtered noise stimuli. The missing 3 neurons were excluded before the analysis because their maximum response rate did not exceed 10 spk/s (<1 spike per stimulation) (Fig. 12A). Seventeen of the remaining 18 neurons had a magnitude of delay asymmetry of at least 60 µs. Gray dashed line shows the 30 µs threshold used for identifying envelope sensitivity. B: distribution of the correlation coefficients of the 17 envelope-sensitive neurons. C: distribution of peak-trough differences of the 17 DIFCOR (black) and SUMCOR (gray) functions. The DIFCOR functions exhibited significantly higher peak-trough differences than the SUMCOR functions (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.01). D: mean phase difference spectra (black line) of the 17 neurons with a delay asymmetry of at least 60 µs and their corresponding vector strength (gray line). Phase differences of ±180° indicate phase sensitivity (black dotted line), while phase differences of 0 or ±360° indicate phase invariance. E: distribution of the differences between the best ITDs of the DIFCOR and the best ITDs of the SUMCOR. The SUMCOR and DIFCOR functions exhibited a different best ITD in 16 of the 17 envelope-sensitive neurons.

We computed the mean phase difference spectra of the 17 envelope-sensitive neurons to analyze the spectral composition of phase-sensitive and phase-invariant response elements. Below 2 kHz the mean phase difference was zero, while the frequency range between 3 and 7 kHz exhibited a mean phase difference of 180° (Fig. 13D). The vector strength was high in both of these ranges (Fig. 13D). The shift in the mean phase difference from 0 to 180° between 2 and 3 kHz was accompanied by a minimum in the vector strength. At 6 kHz the vector strength started to decrease steadily and stayed low for frequencies above 7 kHz. The mean phase difference changed to 270° in this regime.

Both mean phase difference and vector strength exhibit similar trends for high-frequency and broadband noise stimuli (compare Fig. 13D and Fig. 11A). The small phase difference and the high vector strength at frequencies below 2 kHz are especially interesting. They demonstrate that most AAr neurons exhibit a substantial phase-invariant, low-pass element. Since the high-frequency stimuli used for recording lacked energy in frequencies below 2.5 kHz, it was evident at this point that the phase-invariant, low-pass element derived from the envelope of high-frequency sounds. Finally, we determined the best ITD of the DIFCOR and SUMCOR functions to assess whether carrier and envelope inputs represent different ITDs. Most AAr neurons exhibited a clear offset between the best ITDs of the DIFCOR and SUMCOR. The distribution of ITD differences exhibited a median difference of 165 µs and a maximum of 570 µs (Fig. 13E).

We conclude that single neurons in the barn owl’s AAr not only represent the ITD of both the stimulus carrier and the stimulus envelope simultaneously but are also able to extract both from the same frequency range (>2.5 kHz). Even though they represent the ITD of similar frequency ranges, carrier and envelope contributions often exhibited significantly different best ITDs, demonstrating that AAr neurons combine at least two distinct ITD inputs.

DISCUSSION

Neurons in the barn owl’s forebrain were found to represent both carrier and envelope ITDs, similar to what has been observed in midbrain neurons of mammals (e.g., Agapiou and McAlpine 2008). Even though ITD representation was dominated by the carrier in most AAr neurons, the existence of envelope contributions is of particular interest. It is known that neurons in the barn owl’s auditory pathway represent the temporal structure of the stimulus envelope (Keller and Takahashi 2000). However, our results are the first indication that not only the envelope structure but also its ITD are encoded in the barn owl’s auditory pathway.

The barn owl’s auditory pathway reflects the general auditory pathway known in vertebrates (Carr and Edds-Walton 2008). The early stages of the ITD processing pathway exhibit a high similarity to the pathways of crocodilians (Carr et al. 2009) and birds like the chicken (Köppl and Carr 2008; Kuba et al. 2005; Palanca-Castan and Köppl 2015; Schwarz 1992) and the emu (MacLeod et al. 2006). However, little is known about the processing of localization cues in the forebrain of these species. Thus it remains unclear whether the envelope-based ITD representation reported in this study is representative for the prototype of the avian auditory system. In addition, the barn owl has some specializations allowing for high-frequency carrier-driven sound localization (Wagner et al. 2013) that exceeds the frequency limits of other vertebrates. The most important of these specializations is the ability to phase-lock to the stimulus carrier up to at least 9 kHz (Köppl 1997), which is almost the complete hearing range of this bird (Dyson et al. 1998). This would seem to make envelope sensitivity unnecessary if it functioned to extend the range over which ITDs can be used for sound localization as it does in humans and other mammals. Since envelope- and carrier-based ITD representation are observed in the same frequency range here and in other studies (Agapiou and McAlpine 2008; Joris 2003; Louage et al. 2006), envelope sensitivity most likely has other, probably complementary, functions compared with carrier sensitivity.

Representation of envelope ITDs in the midbrain of mammals has been known for a long time (Agapiou and McAlpine 2008; Batra et al. 1993; Dietz et al. 2013; Joris 2003; Kuwada et al. 2012; Smith and Delgutte 2008; Yin et al. 1984; Zheng and Escabí 2013). A comparison of the response properties of mammalian collicular NDFs with those in the AAr of barn owls yields more similarities than a comparison of the collicular NDFs with NDFs from the barn owl’s midbrain pathway (Agapiou and McAlpine 2008; Vonderschen and Wagner 2009). Specifically, Agapiou and McAlpine (2008) showed that the asymmetric NDFs observed in IC neurons of guinea pigs are due to a combination of carrier-sensitive and envelope-sensitive elements just as we report here for forebrain neurons in the barn owl. How neurons in the early auditory pathway represent the ITD of the stimulus envelope is unknown, since up to now all studies that have analyzed ITD representation in the brain stem have focused on the encoding of carrier ITDs. A fully separated pathway dedicated only to the processing of envelope ITDs seems to be unlikely, though. Theoretically, envelope ITDs could be detected and conveyed by the exact same brain stem neurons that represent carrier ITDs. Recordings in the barn owl’s midbrain support this hypothesis. NDFs recorded in the core of the central nucleus of the IC (ICCcore) seem to be composed of a fast-oscillating, periodic element (i.e., the carrier) and a slow, aperiodic element (i.e., the envelope) (Christianson and Peña 2006). Notably, the two elements seem to represent the same best ITDs. Thus, up to the ICCcore, carrier and envelope ITD information seem to be conveyed by the same neurons. However, the carrier and envelope elements of most AAr neurons exhibited a clear difference in the best ITD. This implies that AAr neurons combine at least two inputs with distinct ITD information. The envelope element in the response of ICCcore neurons could be extracted by low-pass filtering or smoothing of rectified NDFs. A subpopulation of neurons in the lateral shell of the ICC (ICCshell)—which receives inputs from the ICCcore—shows a nonlinear dependence of spiking frequency on interaural correlation (Albeck and Konishi 1995). Such a nonlinearity manifests itself in rectified NDFs. Hence, downstream neurons could extract the envelope ITD from the low-pass filtered output of ICCshell neurons. Cohen et al. (1998) showed that the forebrain pathway receives input from both the ICCcore and the ICCshell. Consequently, AAr neurons have access to both carrier (ICCcore) and envelope (ICCshell) information from separate neural inputs.

The close resemblance of the forebrain NDFs in the barn owl to those in the midbrain of small mammals is interesting, because at the level of the midbrain ITD representation in barn owls and small mammals differ (Lesica et al. 2010). While the exact mechanism of ITD detection in mammals is part of a controversial debate (Grothe et al. 2010; Joris and Yin 2007), ITD detection in barn owls is known to follow the Jeffress model (Jeffress 1948; Wagner et al. 2007). Neurons in the barn owl’s nucleus laminaris detect the ITD by encoding the time delay that maximizes the correlation between the inputs from the left and right ear, respectively (Ashida and Carr 2011; Carr and Konishi 1990). Up to the level of the ICC, ITDs are represented in a Jeffress-like, time-based code (Bremen et al. 2007; Singheiser et al. 2010; Wagner et al. 2002, 2007). Hence, the mixed time- and phase-based code in the AAr depends on a remodeling of the ITD representation along the forebrain pathway (Vonderschen and Wagner 2012, 2014). We argue here that in this process of remodeling envelope information becomes represented in the ITD curves.