Abstract

Importance

Readmission rates declined after announcement of the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP), which penalizes hospitals for excess readmissions for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia.

Objective

To compare trends in readmission rates for target and non-target conditions, stratified by hospital penalty status.

Design, Setting, Participants

Retrospective cohort study of 48,137,102 hospitalizations of 20,351,161 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries over 64 years discharged between January 1, 2008 and June 30, 2015 from 3,497 hospitals. Difference interrupted time series models were used to compare trends in readmission rates by condition and penalty status.

Exposure

Hospital penalty status or target condition under the HRRP.

Outcome

30-day risk adjusted, all-cause unplanned readmission rates for target and non-target conditions.

Results

In January 2008, the mean readmission rates for AMI, HF, pneumonia and non-target conditions were 21.9%, 27.5%, 20.1%, and 18.4% respectively at hospitals later subject to financial penalties (n=2,189) and 18.7%, 24.2%, 17.4%, and 15.7% at hospitals not subject to penalties (n=1,283). Between January 2008 and March 2010, prior to HRRP announcement, readmission rates were stable across hospitals (except AMI at non-penalty hospitals). Following announcement of HRRP (March 2010), readmission rates for both target and non-target conditions declined significantly faster for patients at hospitals later subject to financial penalties compared with those at non-penalized hospitals (AMI, additional decrease of −1.24 (95% CI, −1.84, −0.65) percentage points per year relative to non-penalty discharges; HF, −1.25 (−1.64, −0.65); pneumonia, −1.37 (−0.95, −1.80); non-target, −0.27 (−0.38, −0.17); p<0.001 for all). For penalty hospitals, readmission rates for target conditions declined significantly faster compared with non-target conditions (AMI: additional decline of −0.49 (−0.81, −0.16) percentage points per year relative to non-target conditions, p=0.004; HF: −0.90 (−1.18, −0.62), p<0.001; pneumonia: −0.57 (−0.92,−0.23), p<0.001). By contrast, among non-penalty hospitals, readmissions for target conditions declined similarly or more slowly compared with non-target conditions (AMI: additional increase of 0.48 (0.01, 0.95) percentage points per year, p=0.05; HF: 0.08 (−0.30, 0.46), p=0.67; pneumonia: 0.53 (0.13, 0.93), p=0.01). After HRRP implementation in October 2012, the rate of change for readmission rates plateaued (p<0.05 for all except pneumonia at non-penalty hospitals) with the greatest relative change observed among hospitals subject to financial penalty.

Conclusions

Patients at hospitals subject to penalties had greater reductions in readmission rates compared with those at non-penalized hospitals. Changes were greater for target conditions at penalized hospitals, but not at non-penalized hospitals.

Background

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) was enacted under Section 3025 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in March 2010 and imposed financial penalties beginning in October 2012 for hospitals with higher than expected readmissions for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), congestive heart failure (HF), and pneumonia among their fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries.1 Since the program’s inception, thousands of hospitals have been subjected to penalties now totaling nearly a billion dollars.2,3

A recent examination of trends in readmission rates demonstrated that across all hospitals, readmission rates significantly declined for target conditions (AMI, HF, pneumonia) and non-target conditions, with a greater decline for the former, following announcement of the HRRP.4 It is not known whether trends in readmission rates overall, as well as specifically for target and non-target conditions, differed based upon whether a hospital was subject to penalties under the HRRP. Such information could offer insights into the mechanisms of the effect of HRRP on hospital performance. For example, reductions in readmission that are limited to hospitals later subject to financial penalty and/or that are larger in magnitude for target as compared with non-target conditions would suggest either that hospitals responded to anticipated or actual penalties, or that penalized hospitals with higher baseline readmission rates were more able to achieve reductions. By contrast, more widespread changes would suggest that all hospitals responded to the threat of potential penalties, or were equally able to reduce readmissions. Similarly, comparable reductions in readmission rates among target and non-target conditions would suggest hospitals implemented broad, system-wide interventions to reduce readmissions, whereas selective reductions in readmissions for target conditions would suggest hospitals implemented narrower, condition-specific strategies.

Accordingly, we sought to compare trends in readmission rates for target and non-target conditions among patients hospitalized at hospitals that were and were not penalized under the HRRP.

Methods

Study Cohort

We used Medicare fee for service (FFS) claims data for January 1, 2008 through June 30, 2015 to identify hospital admissions. Study cohorts were defined consistent with CMS methods for public reporting as well as HRRP, the details of which have been published previously.5–7 Briefly, for condition specific measures, we used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to identify discharges of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older with a principal discharge diagnosis of acute AMI, HF, and pneumonia. To define a cohort for non-target conditions, we used methodology for the hospital-wide readmission measure, which has also been described previously.8,9 This measure excludes admissions for medical treatment of cancer and uses ICD-9 codes to assign remaining hospitalizations to one of 5 cohorts – medicine, surgery/gynecology, cardiorespiratory, cardiovascular, and neurology. For this study, we removed hospitalizations for AMI, HF, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and hip or knee arthroplasty surgery from the non-target condition cohort. We excluded COPD and hip or knee arthroplasty surgery patients as these conditions were added to the HRRP program during the study period. We also excluded patients discharged from hospitals that were not eligible for HRRP (psychiatric, rehabilitation, long term care, children’s, cancer and critical access hospitals, as well as all hospitals in Maryland). Patients who died during the hospitalization or did not have at least 30 days of post-discharge enrollment in Medicare FFS were excluded as were patients who left the hospital against medical advice or were enrolled in hospice at the time of admission or at any time in the previous 12 months.

Hospital Penalty Status

We obtained data on which hospitals were subject to penalties at the time HRRP was implemented in October 2012 from the CMS website.10 Hospitals were first privately provided, by CMS, their readmission rates along with national rates for heart failure in August 2008 (calendar year 2006 data), then in April 2009 privately received readmission rates for AMI, HF, and pneumonia (July 2005–June 2008 data), prior to public reporting in July 2009. In April 2010, shortly after the HRRP was announced, hospitals received similar reports for July 2006 to June 2009, which included the first penalty year (initial penalty based upon performance in July 2008 to June 2011). By this time, two of the three years used to determine HRRP penalties had already passed (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Therefore, prior to the actual implementation of HRRP in October, 2012, poor performing hospitals were likely aware of their risk for impending financial penalties.

Outcome

The outcome was discharge-level 30-day risk-adjusted all-cause unplanned readmission. For all calculations of readmission, we used a CMS algorithm to exclude planned readmissions for procedures or diagnoses that are typically elective or scheduled such as maintenance chemotherapy and organ transplant.11,12 If a patient experienced multiple readmissions within the post-discharge period of the index hospitalization, only the first readmission was counted.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of hospitals that were and were not subject to penalties under the HRRP were obtained from the American Hospital Association annual survey (2013) and were compared using Chi-square testing. To examine time trends we calculated a single risk-adjusted monthly readmission rate for each cohort: AMI, HF, pneumonia and non-target conditions, stratifying by discharge from a hospital that received a penalty in fiscal year 2013 or not. We used a single rate for each month to avoid the challenges of estimating and modelling hospital level rates for monthly denominators that were often very low. We estimated the monthly rates for each cohort using a linear probability model, with readmission as dependent variable, all risk factors from the corresponding publicly-reported measure as independent variables, and an indicator for each calendar month. All independent variables except month were centered on their overall mean for the cohort, and the intercept was suppressed to allow all monthly indicators to remain in the model. The coefficients for each month were then used as the estimated adjusted monthly rate for that cohort.

To determine the effect of the HRRP on readmission rates we estimated a set of interrupted time series models using the adjusted monthly rate as the dependent variable. Interrupted time series models can incorporate both overall and trend effects of one or more events, or interruptions, in a long-term trend.13,14 Each model included a monthly time trend variable, indicators for the post-announcement and post-implementation periods, as well as terms for the interaction of announcement and implementation dates with the overall monthly trend during the period after that date. In this approach the overall trend in readmission rate (“time”) is deconstructed into three components – the slope in readmission rates in the pre-HRRP period (Jan 2008 through March 2010); the change in slope in the post-HRRP announcement but pre-HRRP implementation period relative to the pre-HRRP period (April 2010 through September 2012); andthe additional change in slope in the post HRRP implementation period (October 2012 through June 2015), relative to the announcement period. In addition, the coefficient of the time period indicators represents any overall effect independent of changes in the slopes.

We first examined the effect of the HRRP announcement and implementation on trends in readmission rates by constructing eight interrupted time series models: two each for AMI, HF, pneumonia and non-target conditions, stratifying discharges based upon whether they were or were not from hospitals subjected to financial penalties. To determine whether there was a differential effect on discharges from penalty vs. non-penalty hospitals, we then estimated analogous models using as dependent variable the difference in monthly rates for each condition between penalty and non-penalty hospitals (“difference models”). To assess whether there was a differential change in target versus non-target conditions, we estimated another set of difference models using as dependent variable the difference in monthly rates between each target condition and all non-target conditions.

For non-differenced interrupted time series models we used linear regression models with autoregressive error terms. We first estimated a series of models with no independent variables and a range of autoregressive terms to identify the best error structure and then used that structure in the final models. For the differenced outcome interrupted time series models we identified no autoregressive term and used ordinary linear regression. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.3.0 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary NC) and Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp, College Station TX). All tests for statistical significance were 2-tailed and evaluated at a significance level of 0.05. The Yale University Human Investigation Committee accepted a waiver of consent and approved this analysis.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 48,137,102 hospitalizations and 7,964,608 readmissions among 20,351,161 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries discharged between January 1, 2008 and June 30, 2015 from 3,497 hospitals. Characteristics of hospitals that were and were not subject to penalties under the HRRP are shown in eTable 2. As compared with non-penalty hospitals (n=1283, 37%), penalty hospitals (n=2214, 63%) were larger, more likely to be teaching hospitals and had higher proportions of Medicaid patients. The annual number of hospital discharges and readmissions for each target condition and for non-target conditions, stratified by hospital penalty status, is shown in Table 1. The volume of hospitalizations for target conditions and non-target conditions declined gradually over the course of the study period for both penalized and non-penalized hospitals.

Table 1.

Number of hospitalizations and readmissions 2008 to 2015 in each cohort by year stratified by penalty status

| Cohort | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMI hospitalizations | Penalty (n=2209) | 133,483 | 126,890 | 125,658 | 124,379 | 115,804 | 121,660 | 118,236 | 60,415 |

| Non-Penalty (n=1045) | 57,869 | 55,131 | 55,125 | 55,180 | 51,419 | 54,591 | 53,799 | 27,582 | |

| Total (n=3254) | 191,352 | 182,021 | 180,783 | 179,559 | 167,223 | 176,251 | 172,035 | 87,997 | |

|

| |||||||||

| AMI readmissions | Penalty (n=2209) | 27,698 | 26,307 | 25,514 | 24,604 | 21,836 | 21,344 | 20,171 | 10,317 |

| Non-Penalty (n=1045) | 9,694 | 8,812 | 8,763 | 8,890 | 7,928 | 8,020 | 7,713 | 4,098 | |

| Total (n=3254) | 37,392 | 35,119 | 34,277 | 33,494 | 29,764 | 29,364 | 27,884 | 14,415 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Heart failure hospitalizations | Penalty (n=2214) | 335,763 | 339,553 | 334,493 | 320,622 | 280,539 | 293,161 | 289,678 | 155,126 |

| Non-Penalty (n=1108) | 119,039 | 122,125 | 120,523 | 117,305 | 104,812 | 112,545 | 114,485 | 62,040 | |

| Total (n=3322) | 454,802 | 461,678 | 455,016 | 437,927 | 385,351 | 405,706 | 404,163 | 217,166 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Heart failure readmissions | Penalty (n=2214) | 87,625 | 88,818 | 87,304 | 81,449 | 68,746 | 68,621 | 67,247 | 36,170 |

| Non-Penalty (n=1108) | 26,246 | 26,431 | 25,973 | 25,022 | 22,287 | 23,145 | 23,553 | 12,829 | |

| Total (n=3322) | 113,871 | 115,249 | 113,277 | 106,471 | 91,033 | 91,766 | 90,800 | 48,999 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Pneumonia hospitalizations | Penalty (n=2214) | 260,675 | 243,812 | 242,873 | 250,316 | 218,394 | 228,120 | 201,725 | 119,459 |

| Non-Penalty (n=1126) | 105,959 | 98,298 | 97,703 | 101,054 | 89,285 | 94,024 | 85,051 | 51,086 | |

| Total (n=3340) | 366,634 | 342,110 | 340,576 | 351,370 | 307,679 | 322,144 | 286,776 | 170,545 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Pneumonia readmissions | Penalty (n=2214) | 49,529 | 47,510 | 47,380 | 47,872 | 40,181 | 40,091 | 35,482 | 20,061 |

| Non-Penalty (n=1126) | 16,977 | 15,652 | 15,406 | 15,948 | 14,321 | 14,561 | 13,321 | 7,624 | |

| Total (n=3340) | 66,506 | 63,162 | 62,786 | 63,820 | 54,502 | 54,652 | 48,803 | 27,685 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Non-target conditions# hospitalizations | Penalty (n=2214) | 4,213,504 | 4,129,709 | 4,123,491 | 4,095,852 | 3,614,980 | 3,705,051 | 3,571,020 | 1,795,772 |

| Non-Penalty (n=1283) | 1,690,022 | 1,637,626 | 1,627,903 | 1,628,501 | 1,464,849 | 1,533,120 | 1,498,431 | 760,407 | |

| Total (n=3497) | 5,903,526 | 5,767,335 | 5,751,394 | 5,724,353 | 5,079,829 | 5,238,171 | 5,069,451 | 2,556,179 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Non-target conditions# readmissions | Penalty (n=2214) | 709,504 | 693,997 | 694,795 | 688,267 | 591,673 | 589,432 | 571,710 | 286,030 |

| Non-Penalty (n=1283) | 243,216 | 234,063 | 234,023 | 234,951 | 207,235 | 213,928 | 210,175 | 106,518 | |

| Total (n=3497) | 952,720 | 928,060 | 928,818 | 923,218 | 798,908 | 803,360 | 781,885 | 392,548 | |

Includes January 1 through June 30, 2015

Cohort excludes acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hip and knee arthroplasty surgery.

Effect of the HRRP on readmission rates, stratified by hospital penalty status

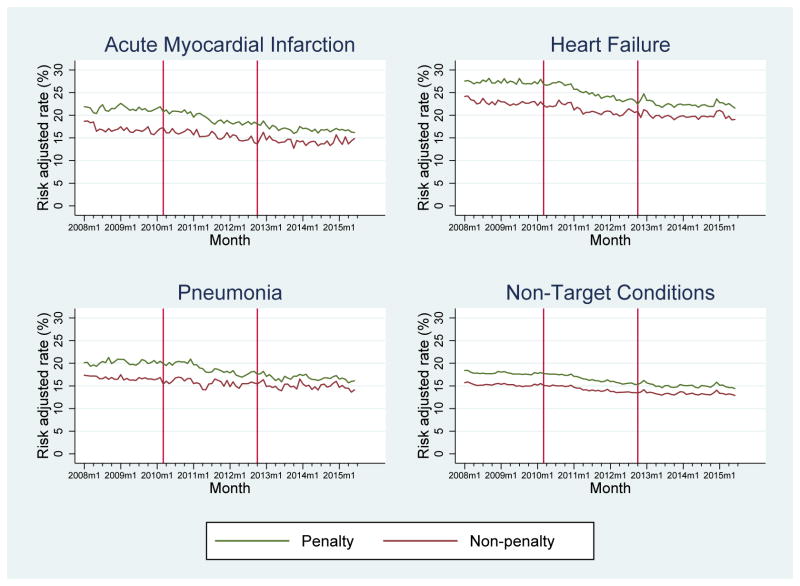

Monthly, risk-adjusted all-cause readmission rates for the three target conditions and the non-target conditions for patients discharged from hospitals that were and that were not subject to the HRRP penalty are shown in the Figure (Panels A–D) and Table 2. In January 2008, the mean readmission rates for AMI, HF, pneumonia and non-target conditions were 21.9%, 27.5%, 20.1%, and 18.4% respectively at hospitals later subject to financial penalties under HRRP and 18.7%, 24.2%, 17.4%, and 15.7% at hospitals not subject to HRRP penalties. Between January 2008 and March 2010, prior to HRRP announcement, readmission rates were stable for target and non-target conditions regardless of penalty status except for AMI, for which readmission rates were declining at 0.78 percentage points per year (95% CI, −1.18, −0.38) among hospitals that were not later subject to penalties. After announcement of HRRP, trends in readmission rates differed significantly based upon hospital penalty status. Specifically, readmission rates declined by 1.30 percentage points per year (95 % CI, −1.88, −0.72) for AMI compared with the pre-announcement period, by 1.72 percentage points per year (95% CI, −2.36, −1.08) for heart failure, and by 1.36 percentage points per year (95% CI, −2.09, −0.63) for pneumonia among patients discharged from hospitals later subject to penalties (p<0.001 for all). In contrast, hospitals not subject to penalties saw no significant change in readmission rates for any of the three target conditions after HRRP announcement (AMI: −0.08 percentage points per year (SE 0.29); HF: −0.45 (95% CI, −1.10, 0.20), pneumonia: −0.03 (95% CI, −1.15, 1.10); p=NS for all).

Figure 1.

Risk adjusted readmission rates stratified by hospital penalty status for acute myocardial infarction (A), heart failure (B), pneumonia (C), and non-target condition (D) cohorts from January 2008 to June 2015. The vertical lines represent announcement of the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (March 2010) and its subsequent implementation (October 2012). Readmission rates are risk-adjusted for age, sex, comorbidity and principal diagnosis (for non-target condition group).

Table 2.

Interrupted Time Series Analysis Stratified by Penalty Status. Results represent annualized percentage rate of change in readmission rates during each specified time interval or the additional absolute change, relative to previous trend, at specific time points.

| Cohort | Pre-HRRP Announcement (January 2008 – March 2010) |

HRRP Announcement (March 2010) |

Post-HRRP Announcement, Pre-HRRP Implementation (April 2010–September 2012) |

HRRP Implementation (October 2012) |

Post HRRP Implementation (October 2012–June 2015) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annualized rate of change (95% CI) |

p- value |

Additional absolute change (95% CI) |

p-value | Annualized rate of change (95% CI) |

p-value | Additional absolute change (95% CI) |

p-value | Annualized rate of change (95% CI) |

p-value | ||

| AMI | Penalty (n=2209) | −0.01 (−0.47, 0.44) | 0.95 | −0.29 (−1.04, 0.45) | 0.44 | −1.30 (−1.88, −0.72) | <0.001 | −0.16 (−0.82, 0.49)) | 0.63 | 0.84 (0.34, 1.34) | 0.001 |

| Non-penalty (n=1045) | −0.78 (−1.18, −0.38) | <0.001 | 0.65 (−0.20, 1.50) | 0.14 | −0.08 (−0.66, 0.50) | 0.79 | −0.10 (−0.80, 0.59)) | 0.77 | 0.70 (0.22, 1.19) | 0.005 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Heart failure | Penalty (n=2214) | −0.03 (−0.55, 0.49) | 0.91 | 0.08 (−0.60, 0.75) | 0.82 | −1.72 (−2.36, −1.08) | <0.001 | −0.07 (−0.72, 0.58) | 0.83 | 1.46 (1.05, 1.86) | <0.001 |

| Non-penalty (n=1108) | −0.43 (−0.96, 0.09) | 0.11 | −0.12 (−1.08, 0.85) | 0.82 | −0.45 (−1.10, 0.20) | 0.18 | 0.04 (−0.63, 0.70) | 0.91 | 0.67 (0.16, 1.17) | 0.009 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Pneumonia | Penalty (n=2214) | 0.22 (−0.37, 0.80) | 0.47 | −0.09 (−0.93, 0.75) | 0.83 | −1.36 (−2.09, −0.63) | <0.001 | −0.12 (−0.94, 0.70) | 0.77 | 0.80 (0.24, 1.36) | 0.005 |

| Non-penalty (n=1126) | −0.27 (−1.26, 0.73) | 0.60 | −0.39 (−1.55, 0.76) | 0.51 | −0.03 (−1.15, 1.10) | 0.96 | −0.01 (−0.76, 0.75) | 0.99 | 0.04 (−0.45, 0.54) | 0.86 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Non-Target Conditions* | Penalty (n=2214) | −0.17 (−0.43, 0.10) | 0.22 | 0.14 (−0.37, 0.65) | 0.60 | −0.81 (−1.23, −0.39) | <0.001 | 0.06 (−0.43, 0.54) | 0.82 | 0.73 (0.41, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Non-penalty (n=1283) | −0.15 (−0.35, 0.05) | 0.14 | 0.05 (−0.33, 0.42) | 0.80 | −0.54 (−0.85, −0.23) | 0.001 | 0.09 (−0.31, 0.49) | 0.66 | 0.57 (0.31, 0.83) | <0.001 | |

Excludes acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hip and knee arthroplasty surgery.

For non-target conditions, we observed more modest but statistically significant declines in readmission rates after announcement of HRRP regardless of whether or not the patient was discharged from a hospital that was penalized (penalty: −0.81 percentage points per year (95% CI, −1.23, −0.39); non-penalty: −0.54 (95% CI, −0.85, −0.23); p<0.001). After HRRP implementation in October 2012, the rate of change for readmission rates plateaued relative to the change observed after announcement but prior to implementation, for both target and non-target conditions among both penalty and non-penalty discharges (p<0.05 for all except pneumonia at non-penalty hospitals), with the greatest relative change observed among hospitals subject to financial penalty. As a result, readmission rates for target and non-target conditions have not significantly changed since October 2012 across hospitals regardless of penalty status.

The results of the difference interrupted time series models, which determine the difference between readmission rates for penalty versus non-penalty hospitals, stratified by condition, are shown in Table 3. Prior to the announcement of the HRRP, readmission rates for patients at hospitals later subject to a penalty were declining less rapidly than those for patients at hospitals not later subject to financial penalties (AMI, increase of 0.72 percentage points per year for penalty hospital discharges vs non-penalty hospital discharges (95% CI, 0.26, 1.19); HF 0.35 (95% CI, 0.04, 0.65); pneumonia, 0.48 (95% CI, 0.15, 0.81); p<0.05 for all). However, between April 2010 and October 2012, after the announcement but prior to the actual implementation of the HRRP, readmission rates began to improve significantly faster for patients at hospitals later subject to financial penalties (AMI, decrease of −1.24 percentage points per year for penalty hospital discharges vs non-penalty hospital discharges (95% CI, −1.84, −0.65); HF, −1.25 (95% CI, −1.64, −0.86); pneumonia, −1.37 (−1.80, −0.95); p<0.001 for all).

Table 3.

Interrupted Time Series Analysis for the Difference Between Penalty and Non-penalty Hospitals. Results represent the difference in the annualized percentage rate of change in readmission rates during each specified time interval or the additional absolute change, relative to previous trend, at specific time points for penalty hospitals relative to non-penalty hospitals.

| Condition | Pre-HRRP Announcement (January 2008 – March 2010) | HRRP Announcement (March 2010) | Post-HRRP Announcement, Pre-HRRP Implementation (April 2010–September 2012) | HRRP Implementation (October 2012) | Post HRRP Implementation (October 2012–June 2015) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in annualized rate of change* (95% CI) | p-value | Difference in additional absolute change* (95% CI) | p-value | Difference in annualized rate of change* (95% CI) | p-value | Difference in additional absolute change* (95% CI) | p-value | Difference in annualized rate of change* (95% CI) | p-value | |

| AMI | 0.72 (0.26, 1.19) | 0.003 | −0.79 (−1.58, 0.00) | 0.051 | −1.24 (−1.84, −0.65) | <0.001 | 0.01 (−0.75, 0.77) | 0.971 | 0.21 (−0.29, 0.70) | 0.406 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Heart failure | 0.35 (0.04, 0.65) | 0.027 | 0.26 (−0.26, 0.78) | 0.321 | −1.25 (−1.64, −0.86) | <0.001 | 0.06 (−0.44, 0.56) | 0.806 | 0.76 (0.43, 1.08) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Pneumonia | 0.48 (0.15, 0.81) | 0.005 | 0.35 (−0.22, 0.92) | 0.223 | −1.37 (−1.80, −0.95) | <0.001 | 0.03 (−0.51, 0.57) | 0.914 | 0.75 (0.40, 1.11) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Non-Target Conditions# | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.07) | 0.828 | 0.12 (−0.02, 0.26) | 0.091 | −0.27 (−0.38, −0.17) | <0.001 | −0.06 (−0.19, 0.07) | 0.368 | 0.18 (0.10, 0.27) | <0.001 |

For patients at penalty hospitals relative to non-penalty hospitals

Excludes acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hip and knee arthroplasty surgery.

For non-target conditions, penalty and non-penalty hospitals were improving at similar rates prior to HRRP announcement (difference of −0.01 percentage points per year (95% CI, −0.09, 0.07), p=0.83). Upon announcement of the HRRP but prior to its implementation, readmission rates began to converge but more modestly than observed for target conditions (relative decrease of −0.27 (95% CI, −0.38, −0.17) percentage points per year for penalty hospital discharges vs non-penalty hospital discharges, p<0.001).

Comparison of the effect of the HRRP on target and non-target conditions, stratified by hospital penalty status

The results of the difference interrupted time series models, which determine the difference for target versus non-target conditions, stratified by hospital penalty status, are shown in Table 4. At hospitals that were subject to financial penalties under HRRP, in the period after announcement of the HRRP, the reductions in readmissions for AMI, HF, and pneumonia were significantly greater than the reductions observed for non-target conditions (AMI: relative decline of −0.49 percentage points per year (95% CI, −0.81, −0.16), p=0.004; HF: −0.90 (95% CI, −1.18, −0.62), p<0.001; pneumonia: −0.57 (−0.92, −0.23), p<0.001). In contrast, at hospitals that were not subject to financial penalties under HRRP, there was no differential improvement in readmission rates for target conditions. Reductions in readmissions were either comparable for the target and non-target conditions or greater for the non-target conditions (AMI: relative increase of 0.48 percentage points per year (95% CI, 0.01, 0.95), p=0.05; HF: 0.08 (95% CI, −0.30, 0.46), p=0.67; pneumonia: 0.53 (95% CI, 0.13, 0.93), p=0.01).

Table 4.

Interrupted Time Series Analysis for the Difference Between Each Target Condition and Non-target Conditions Stratified by Penalty Status. Results represent the difference in the annualized percentage rate of change in readmission rates during each specified time interval or the additional absolute change, relative to previous trend, at specific time points for each target condition, relative to non-target conditions, across hospitals that were and were not subject to penalties under the HRRP.

| Cohort | Pre-HRRP Announcement (January 2008 – March 2010) | HRRP Announcement (March 2010) | Post-HRRP Announcement, Pre-HRRP Implementation(April 2010–September 2012) | HRRP Implementation (October 2012) | Post HRRP Implementation (October 2012–June 2015) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in annualized rate of change* (95% CI) | p-value | Difference in additional absolute change* (95% CI) | p-value | Difference in annualized rate of change* (95% CI) | p-value | Difference in additional absolute change* (95% CI) | p-value | Difference in annualized rate of change* (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| AMI | Penalty | 0.15 (−0.11, 0.40) | 0.26 | −0.45 (−0.89, −0.02) | 0.039 | −0.49 (−0.81, −0.16) | 0.004 | −0.19 (−0.61, 0.22) | 0.364 | 0.09 (−0.18, 0.35) | 0.527 |

| Non-penalty | −0.59 (−0.95, −0.22) | <0.002 | 0.45 (−0.17, 1.08) | 0.154 | 0.48 (0.01, 0.95) | 0.045 | −0.26 (−0.87, 0.34) | 0.384 | 0.06 (−0.33, 0.45) | 0.751 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Heart failure | Penalty | 0.10 (−0.12, 0.32) | 0.37 | −0.02 (−0.39, 0.35) | 0.926 | −0.90 (−1.18, −0.62) | <0.001 | −0.04 (−0.39, 0.32) | 0.835 | 0.72 (0.49, 0.95) | <0.001 |

| Non-penalty | −0.26 (−0.56, 0.04) | 0.09 | −0.16 (−0.67, 0.35) | 0.53 | 0.08 (−0.30, 0.46) | 0.671 | −0.16 (−0.65, 0.33) | 0.516 | 0.14 (−0.17, 0.46)) | 0.371 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Pneumonia | Penalty | 0.37 (0.10, 0.64) | 0.008 | −0.20 (−0.66, 0.25) | 0.375 | −0.57 (−0.92, −0.23) | 0.001 | −0.03 (−0.47, 0.41) | 0.899 | 0.05 (−0.24, 0.33) | 0.744 |

| Non-penalty | −0.12 (−0.44, 0.19) | 0.438 | −0.44 (−0.97, 0.10) | 0.109 | 0.53 (0.13, 0.93) | 0.011 | −0.12 (−0.63, 0.40) | 0.65 | −0.52 (−0.86, −0.19) | 0.003 | |

For target conditions relative to non-target conditions

Discussion

Our longitudinal examination of trends in readmission rates among Medicare beneficiaries demonstrates that the significant reductions in readmission observed after announcement of financial penalties under the HRRP program occurred primarily at hospitals that were subject to financial penalties. Still further, readmission rates for target conditions declined significantly more than rates for non-target conditions at hospitals later subject to HRRP penalties, which suggests that these hospitals specifically focused efforts to improve readmission outcomes for patients admitted for these target conditions. In contrast, at hospitals not subject to financial penalties, readmission rates for non-target conditions had declines comparable with those for target conditions, which suggests that broader, system-wide readmission reduction strategies were more likely to have been employed as opposed to strategies focusing solely on the target conditions. Finally, across all hospitals, readmission rates for target and non-target conditions have not significantly changed since October 2012. These findings have important implications for future policy programs aimed at reducing readmissions and provide insight into the effect of external incentives.

This analysis helps elucidate the mechanism by which financial penalties in the HRRP were effective. Hospital readmission performance for AMI, HF, and pneumonia for 2005–2008 was privately reported to hospitals beginning in April 2009 and publicly displayed on Hospital Compare beginning in July 2009. Yet, readmission rates were stable between January 2008 and March 2010, suggesting minimal effect of public reporting alone. Other studies have found similar results.15 Moreover, announcement of the HRRP in April 2010 was associated with a significant decrease in readmissions, particularly for target conditions and primarily among patients discharged from hospitals that had the highest readmission rates initially and were thus later subject to penalties. Specifically, it appears that the announcement of the policy was associated with improvement because it was coupled with the knowledge that the hospital was likely to face a financial penalty. Low-performing hospitals appear to have proactively responded to the threat of penalties, likely because they were aware of their performance; higher performing hospitals did not respond in the same way, suggesting that they felt less urgency to specifically improve for the target conditions. These results are consistent with a recent survey of hospital leaders, which reported that 66% felt that the HRRP had a major impact on system efforts to reduce readmission rates.16 Policymakers considering payment penalty programs should thus consider whether the results on which they are based are available – ideally in advance of implementation – to the relevant stakeholders. Finally, the fact that the rate of change for 30-day readmission rates have plateaued for all conditions since October 2012 raises a number of important considerations. This may reflect that after initially realizing reductions in readmissions with modest investment and interventions, additional reductions in readmissions may be less feasible or may require larger scale investment with smaller marginal benefit. Still further, hospitals may have assessed the competing financial impact of readmissions on revenue and the potential penalty under the HRRP and determined that the net effect of additional reductions in readmission was not fiscally advantageous. The question of whether additional reductions in readmission rates can be realized and if so, what policy and payment levers will be most effective in doing so remains an important priority for further study.

A recent study demonstrated that in the period after the HRRP, readmission rates for both target and non-target conditions declined significantly, with larger reductions among the former, and that readmission rates did not appear to decline as a consequence of increased use of observation services.17 The current analysis extends this work in a number of ways. First, it incorporates each hospital’s penalty status and suggests important differences in the association of the HRRP with trends in readmission rates based upon whether a hospital was or was not subject to a financial penalty. An overall analysis without regard to penalty status masks the heterogeneity we report and the policy implications that follow. In addition, the present analysis used the publicly reported hospital wide readmission measure cohort as the comparator population (non-target conditions) and excluded patients with the target conditions as well as admissions for COPD and hip-knee replacement surgery as these conditions are now included in HRRP.

There are several limitations to this analysis. First, while the interrupted time series is a valid, quasi-experimental approach to evaluating changes over time, it by design attributes observed changes to a single factor (the HRRP in this instance). Reducing readmissions had been an important priority for several years prior to HRRP and there were several national quality improvement programs focusing on readmission reduction over the time period of this study. For instance, the CMS Partnership for Patient’s Hospital Engagement Networks (starting April 2011) and the CMS Community-based Care Transitions Program (starting February 2012), may have also contributed to the temporal trends.18–20 Nonetheless, those national quality improvement programs were unlikely to have been very effective so early after initiation, and even if they contributed, uptake was likely influenced by knowledge of the impending HRRP penalties. Moreover, most hospitals in the nation participated in Hospital Engagement Networks, yet we observed effects only among penalty hospitals. Second, the disproportionate improvement among patients discharged from penalty hospitals may be a result of “regression to the mean,” in which random variation causing outlier performance is reduced in subsequent periods. If regression to the mean were a substantial influence, however, one would have expected similar regression to the mean among high performing outliers – that is, a worsening of readmission rates among non-penalty hospitals. This effect was not present, reducing the likelihood that regression to the mean explains the results. Third, the precise mechanism for the observed differential improvements is unknown: hospitals with high readmission rates that were responding to the HRRP may have found it easier to reduce readmissions, invested more resources, prioritized readmission reduction interventions to a greater degree, or a combination thereof. Fourth, hospitals were stratified based on penalty status at the time of HRRP implementation in FY2013 even though Medicare reassessed hospitals’ penalty status each fiscal year. However, 84.3% of hospitals retained the same penalty status in both years and hospitals that changed status were subject to much smaller average penalties that those that did not.10,21 As additional longitudinal data become available, analyses of the effects of changing financial penalties over time to further define the association of the HRRP on readmission rates should be undertaken. Fifth, observation stays were not included in this analysis. However, prior work17 has suggested that reductions in readmission were not realized by increasing use of observation stays and therefore it is unlikely that this would have meaningfully affected our study results. Sixth, to the approach does not account for differential coding practices across hospitals or changes in documentation over time which could have affected our results. Seventh, whether the observed reductions in readmissions have been associated with changes in other quality measures, particularly 30-day risk standardized mortality measures, remains an important question that warrants additional study.

Conclusions

In summary, hospitals subject to penalties under HRRP had greater reductions in readmission rates as compared with non-penalized hospitals. Changes were greater for target condition, as compared with non-target conditions, at the penalized hospitals, but not at non-penalized hospitals.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

Was the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) associated with different changes in readmission rates for targeted and non-targeted conditions among penalized and non-penalized hospitals?

Findings

In this longitudinal cohort study of 48,137,102 hospitalizations among 20,351,161 Medicare fee-for-service patients across 3497 hospitals, announcement of the HRRP was associated with significant reductions in readmissions at hospitals later subject to penalties, with significantly larger reductions for target conditions. Hospitals not subject to financial penalties experienced comparable reductions in readmissions for target and non-target conditions. Readmission rates plateaued across all hospitals after implementation of the HRRP.

Meaning

Hospitals subject to penalties under HRRP had greater reductions in readmission rates compared with non-penalized hospitals. Changes were greater for target vs non-target conditions at the penalized hospitals, but not at non-penalized hospitals.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS022882). Dr. Desai is supported by grant K12 HS023000-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Dharmarajan is supported by grant K23AG048331 from the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. He is also supported by grant P30AG021342 via the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, the American Federation for Aging Research, or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation of the manuscript or decision to submit it for publication.

Author Contributions: Drs. Desai and Horwitz had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Desai, Ross, Horwitz

Acquisition of data: Horwitz, Krumholz

Analysis and interpretation of data: Desai, Ross, Kwon, Herrin, Dharmarajan, Bernheim, Krumholz, Horwitz

Drafting of the manuscript: Desai, Horwitz

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Desai, Ross, Kwon, Herrin, Dharmarajan, Bernheim, Krumholz, Horwitz

Statistical analysis: Kwon, Herrin

Obtained funding: Horwitz

Administrative, technical, or material support: Ross, Herrin, Dharmarajan, Bernheim, Krumholz, Horwitz

Study supervision: Horwitz

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: NRD, JSR, JK, JH, KD, SB, HMK and LIH work under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures. NRD, JSR and HMK are recipients of a research agreement from Johnson & Johnson, through Yale University, to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing. JSR and HMK receive research support from Medtronic, through Yale University, to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing and of a grant from the Food and Drug Administration to develop methods for post-market surveillance of medical devices. Dr. Dharmarajan is a consultant for and member of a scientific advisory board for Clover Health. Dr. Krumholz is the founder of Hugo, a personal health information platform and chairs a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth.

References

- 1.Hospital Readmission Reduction Program, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, §3025 (2010).

- 2.Rau J. Half Of Nation’s Hospitals Fail Again To Escape Medicare’s Readmission Penalties. [Accessed 15 October, 2015];Kaiser Health News. 2015 http://khn.org/news/half-of-nations-hospitals-fail-again-to-escape-medicares-readmission-penalties/

- 3.Boccuti C, Casillas G. Aiming for Fewer Hospital U-Turns: The Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program. Kaiser Family Foundation; Jan, 2015. [Accessed 11 May 2016]. Issue Brief. http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/aiming-for-fewer-hospital-u-turns-the-medicare-hospital-readmission-reduction-program/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, Observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(16):1543–1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindenauer PK, Normand SL, Drye EE, et al. Development, validation, and results of a measure of 30-day readmission following hospitalization for pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):142–150. doi: 10.1002/jhm.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Drye EE, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(2):243–252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keenan PS, Normand SL, Lin Z, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.802686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horwitz L, Partovian C, Lin Z, et al. Hospital-wide all-cause unplanned readmission measure: Final technical report. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2012. [Accessed Nov 10, 2016]. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&cid=1219069855841. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwitz LI, Partovian C, Lin Z, et al. Development and use of an administrative claims measure for profiling hospital-wide performance on 30-day unplanned readmission. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10 Suppl):S66–75. doi: 10.7326/M13-3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed Nov 10, 2016];FY 2013 IPPS Final Rule: Hospital Readmission Reduction Program Supplemental Data File. 2013 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html.

- 11.Horwitz LI, Partovian C, Lin Z, et al. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed June 3, 2015];Planned Readmission Algorithm – Version 2.1. 2013 http://hscrc.maryland.gov/documents/HSCRC_Initiatives/readmissions/Version-2-1-Readmission-Planned-CMS-Readmission-Algorithm-Report-03-14-2013.pdf.

- 12.Horwitz LI, Grady JN, Cohen DB, et al. Development and Validation of an Algorithm to Identify Planned Readmissions From Claims Data. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):670–677. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6 Suppl):S38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeVore AD, Hammill BG, Hardy NC, Eapen ZJ, Peterson ED, Hernandez AF. Has Public Reporting of Hospital Readmission Rates Affected Patient Outcomes?: Analysis of Medicare Claims Data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(8):963–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joynt KE, Figueroa JE, Oray J, Jha AK. Opinions on the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program: results of a national survey of hospital leaders. The American journal of managed care. 2016;22(8):e287–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, Observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543–1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brock J, Mitchell J, Irby K, et al. Association between quality improvement for care transitions in communities and rehospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2013;309(4):381–391. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers For Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed May 11, 2016];Community-based Care Transitions Program. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CCTP/

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed May 11, 2016];Hospital Engagement Networks: connecting hospitals to improve care. 2011 https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2011-Fact-sheets-items/2011-12-14.html.

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed Nov 10, 2016];FY 2014 IPPS Final Rule: Hospital Readmission Reduction Program Supplemental Data File. 2014 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.