Abstract

Background/Aims

To estimate and compare price differences between legal and illicit cigarettes in 14 low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMIC).

Design

A cross‐sectional census of all packs available on the market was purchased.

Setting

Cigarette packs were purchased in formal retail settings in three major cities in each of 14 LMIC: Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, the Philippines, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine and Vietnam.

Participants

A total of 3240 packs were purchased (range = 58 packs in Egypt to 505 in Russia). Packs were categorized as ‘legal’ or ‘illicit’ based on the presence of a health warning label from the country of purchase and existence of a tax stamp; 2468 legal and 772 illicit packs were in the analysis.

Measurements

Descriptive statistics stratified by country, city and neighborhood socio‐economic status were used to explore the association between price and legal status of cigarettes.

Findings

The number of illicit cigarettes in the sample setting was small (n < 5) in five countries (Brazil, Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia) and excluded from analysis. In the remaining nine countries, the median purchase price of legal cigarettes ranged from US$0.32 in Pakistan (n = 72) to US$3.24 in Turkey (n = 242); median purchase price of illicit cigarettes ranged from US$0.80 in Ukraine (n = 14) to US$3.08 in India (n = 41). The difference in median price between legal and illicit packs as a percentage of the price of legal packs ranged from 32% in Philippines to 455% in Bangladesh. Median purchase price of illicit cigarette packs was higher than that of legal cigarette packs in six countries (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam). Median purchase price of illicit packs was lower than that of legal packs in Turkey, Ukraine and China.

Conclusions

The median purchase price of illicit cigarettes is higher than that of legal cigarette packs in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, Brazil, Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia appear to have few or no illicit cigarettes for purchase from formal, urban retailers.

Keywords: Cigarette price, countries, developing, economics, illicit cigarettes, tobacco control, tobacco products

Introduction

In 2011, tobacco use killed almost 6 million people 1. Illicit trade of tobacco products is a global problem that weakens tobacco control policies and erodes tobacco tax revenues 2, 3. Illicit trade is, by its nature, difficult to estimate. A 2010 study estimated illicit cigarettes as accounting for 11.6% of the global, 16.8% of low‐income and 9.8% of high‐income countries’ cigarette consumption 4. The growing attention placed on illicit trade is evidenced by the recent adoption of the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control's Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products which lays out strategies governments can use to eliminate illicit trade of tobacco products 5 . The Protocol requires signature by 40 Parties to the Convention to enter into force 5.

Many factors contribute to illicit trade, including corruption and the presence of organized crime in a country 6. The tobacco industry argues against many tobacco control measures, including tobacco tax increases and standardized packaging, on the basis that such initiatives increase illicit trade of tobacco products 7, 8.

The tobacco industry argument that tax increases will lead to an increase in illicit trade stems from the idea that tax increases drive cigarette prices up, leading to incentives to purchase cheaper, illegally obtained cigarettes both within a given country and its neighbors—tax increases ‘may also lead to greater price differences between nearby countries, encouraging tobacco smuggling across borders’ 9. Indeed, the WHO Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products states that illicit trade ‘poses a threat to public health because it increases access to often cheaper tobacco products’ 5. This statement is based probably on findings from the most extensively studied illicit markets—the United States and Europe—settings where illicit trade involves cheaper products 10, 11. However, limited emerging evidence on illicit cigarettes shows that there is also a market for illicit premium brands. For example, a mini‐survey in Vietnam found that smuggled UK‐produced 555 packs were more expensive than Vietnamese‐produced 555 packs, purportedly because foreign cigarettes are perceived as being of higher quality 12. Other research shows that the overall level of smuggling of cigarettes is higher in countries that have lower cigarette prices 4.

Given the lack of systematically collected data on cigarette prices, user surveys [such as the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS)] and extrapolations have been used to estimate prices paid 4, 13. One study using data from the Cigarette Price and Retailer Survey examined cigarette pricing in Southeast Asia based on in‐person surveys of retailers 14. Two studies have used data from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project, in which surveys of smokers were conducted—one study examining the distribution of cigarette prices under different tax structures in 15 countries in which cigarette prices were derived at the country level 15 and one examining the impact of the Malaysia minimum price law on price of legal and illicit cigarettes 16. Another study conducted face‐to‐face surveys where smokers were asked to provide information on their most recently purchased pack, including price 17. Studies examining littered cigarette packs have been used in many contexts to estimate the amount of tax avoidance and evasion; however, these studies are unable to determine what price was paid for these packs 18, 19, 20, 21.

To our knowledge, no academic study has used a systemic protocol in multi‐site, urban retail settings throughout low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) to examine how purchase prices differ between legal and illicit cigarettes. While tobacco control often focuses upon illicit trade at the lower end of the price distribution, we examine the entire price distribution of cigarettes in the retail environment. This study estimates and compares price differences between legal and illicit cigarettes in 14 low‐ and middle‐income countries. This information is important as a step towards understanding more clearly the full illicit cigarette market in LMICs, how it might be influencing the impacts of tobacco control interventions and strategies needed to address this issue.

Methods

Design

Data were derived from the Tobacco Pack Surveillance System (TPackSS) 22. TPackSS data collection was conducted in 2013. TPackSS is a surveillance study that documents systematically a census of tobacco packs available on the market in the 14 LMICs where more than two‐thirds of the world's smokers live 23: Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, the Philippines, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine and Vietnam. In each of the 14 countries, one of every unique tobacco pack was purchased from a sample of retailers located within 12 low, middle and high socio‐economic neighborhoods in three of the country's 10 most populous cities (Supporting information, Tables S1 and S2). The TPackSS data collection protocol is publicly available at: http://globaltobaccocontrol.org/tpackss/resources.

In‐country field staff used a variety of local and national sources, including census and property value data, to create a sampling frame of low, middle and high socio‐economic areas for each city. Field staff generated a comprehensive list of income or property value data at the neighborhood or smallest municipal level for each city, and in some countries where quantitative data were not available a qualitative description about each area was provided. Income and property value ranges were used to establish high, middle and low socio‐economic status (SES) cut‐offs. Neighborhoods or municipal areas that fell within the cut‐offs were categorized as either high, middle or low SES areas. Within these groupings, a sample of four high, middle and low SES neighborhoods were selected based on diverse geographical and residential composition.

Retail types were selected purposively based on having a large tobacco product inventory. A unique tobacco pack was defined as any pack with at least one difference in an exterior feature of the pack including: stick count, size, brand name, colors, cellophane and inclusion of a promotional item.

The project aimed to provide an enumeration of tobacco products on the market at major retailers in the target countries. By focusing upon data collection in highly populated urban areas, we aimed to collect products available to the majority of the populace. TPackSS did not aim to capture a random sample of cigarette packs but rather aimed to maximize breadth by purchasing one of every unique pack available. Further, we did not have an explicit aim to identify the size of the illicit market in a country, but the protocol was structured such that illicit products were purchased. Price in local currency was collected for each tobacco pack purchased, as well as information as to type of product, brand family, stick count, type of retailer purchased from and date purchased.

Sample

For the purposes of these analyses, only cigarettes (including kreteks or clove cigarettes which were observed on the market and collected in nine countries) are included.

Measures

Pack purchase prices were converted from local currency to US dollars (xe.com) to facilitate cross‐country comparison. The minimum, maximum and median price of legal and illicit cigarettes in local currency can be found in Supporting information, Table S3. The conversion rate for the first day of data collection in each country was used for price conversion 24. Prices of cigarettes sold in packs with fewer or more than 20 sticks were scaled to a standardized 20 sticks per pack by calculating the price per individual stick and multiplying by 20.

Packs were first categorized as ‘legal’ or ‘illicit’ based on the presence of a health warning label (HWL) on the pack issued by a country's authority responsible for tobacco product HWL requirements (Table 1). Two independent coders assessed whether a pack had a HWL issued by the country where the pack was purchased, and a third research team member resolved discrepancies.

Table 1.

Identification of legal and illicit cigarette packs, as classified for analysis.

| Pack purchased in country that does not require an indicator of tax paid (in 4 countries where applicable) | Pack has indicator of tax paid in country of purchase (in 10 countries where applicable) | Pack has no indicator of tax paid or indicator of foreign tax paid (in 10 countries where applicable) | Total packs (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pack has HWL from country of purchase |

Legal (n = 707) |

Legal (n = 1750) |

Legala

(n = 11) |

2468 |

| Pack does not have HWL from country of purchase |

Illicit (n = 81) |

Illicit (n = 0) |

Illicit (n = 691) |

772 |

| Total packs (n) | 788 | 1750 | 702 |

The packs in this cell, which had conflicting health warning label (HWL) and tax indication, were further reviewed and classified as legal as the tax stamps appeared to have fallen off the packs during handling or in transit.

Indication of tax paid was used as a secondary indicator of illicit status for all packs purchased in each of the 10 countries that had this requirement. At the time the packs were purchased, eight countries required that an excise tax stamp be placed on tobacco packs sold in the country (Bangladesh, Brazil, Indonesia, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine and Vietnam) and two additional countries required that a statement of ‘tax paid’ or price ‘inclusive of taxes’ be printed on packs (India and Pakistan).

Three countries did not have a tax stamp system in place at the time of purchase (China, Mexico and the Philippines). Egypt's tax stamp system was implemented in December 2013 (the month data were collected in Egypt); however, at that time, tax stamps were only being applied to 50% of packs manufactured for sale in the country 25, and thus we did not use tax stamp data to confirm legality of packs in Egypt.

In coding for an indication of tax paid, packs were categorized as (1) having an indicator of tax paid in the country in which it was purchased or (2) having no indicator of tax paid or indicator of foreign tax paid. For the 10 countries in which an indicator of tax paid was assessed, correlations between the presence of an appropriate HWL and indicator of tax paid in the country in which it was purchased were found to be near perfect or perfect (0.97–1.00) for all countries. Eleven packs with an appropriate HWL but no indication of tax paid (Bangladesh, n = 1; Brazil, n = 7; Thailand, n = 2; Turkey, n = 1) were reviewed further and adhesive residue on the packs suggests that the tax stamp may have fallen off during handling or transit. Therefore, these packs were coded as legal if they displayed an appropriate HWL and illicit otherwise (Table 1). Our methodology for identifying illicit packs is similar to methods used in other studies where illicit packs are identified; among other indicators, those studies used the presence of country excise tax stamps and appropriate health warning labels as characteristics to identify the legal status of packs 17, 26, 27.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics stratified by country, city and SES were conducted to explore the differences in median prices between legal and illicit cigarettes. Median prices were also analyzed using log transformation and international dollars conversion, and the results were consistent. Data analyses were conducted using Stata version 14 28.

Results

A total of 3240 cigarette packs were purchased from a total of 397 retailers. Overall, 23.8% of the cigarette packs purchased (n = 3240) were categorized as illicit (n = 772), ranging from 0% in Brazil and Indonesia to 81.2% in Pakistan. The illicit cigarette sample was small (n < 5) in three other countries: Egypt (n = 3), Mexico (n = 2) and Russia (n = 1). Supporting information, Table S4 shows the number of legal and illicit cigarette packs purchased by neighborhood SES strata.

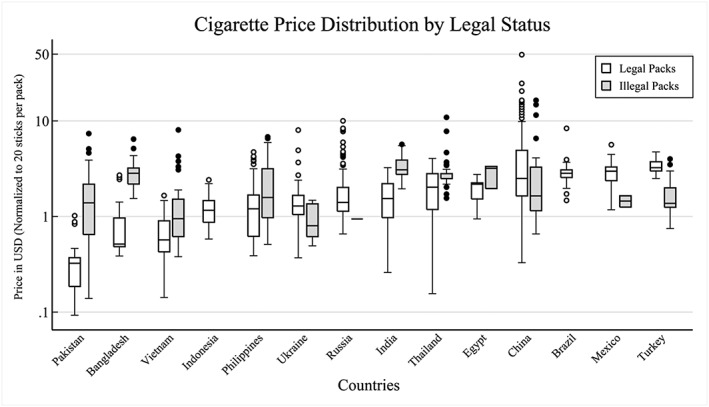

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the price of legal and illegal cigarettes by country; the median price is displayed as a line intersecting each box, the interquartile range (IQR) is demarcated by the lower box (25th percentile) and upper box (75th percentile) and prices outside the middle 50% are marked by the whiskers and outliers (prices outside of 1.5 times the IQR) are denoted as dots. As evidenced in Fig. 1, in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Philippines, India and Thailand the cheapest illicit pack, median purchase price for illicit packs, and costliest illicit pack were all more expensive relative to the same point in the legal price distribution.

Figure 1.

Cigarette pack price country distribution by legal status, ordered by increasing median price of legal packs

The median purchase price of illicit packs was higher than the median purchase price of legal packs in six countries (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam) (Table 2). Median purchase price of legal packs was higher than the median purchase price of illicit packs in three countries (China, Turkey, Ukraine) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Median prices (US$) for illicit and legal packs, ordered by difference in price.

| Country | n | Proportion of illicit packs (%) | Range in price of illicit packs (min, max) | Median price (MAD; n) of illicit packs | Range in price of legal packs (min, max) | Median price (MAD; n) of legal packs | Difference (median illicit pack price–median legal pack price) | Absolute difference as percentage of median price of legal packs (%) | Illicit price to legal price ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 191 | 70.7 | (1.54, 6.43) | 2.83 (0.51; 135) | (0.39, 2.70) | 0.51 (0.24; 56) | 2.32 | 455 | 5.55 |

| India | 135 | 30.4 | (1.95, 5.67) | 3.08 (0.57; 41) | (0.26, 3.24) | 1.54 (0.62; 94) | 1.54 | 100 | 2.00 |

| Pakistan | 382 | 81.2 | (0.14, 7.36) | 1.39 (0.76; 310) | (0.09, 1.02) | 0.32 (0.09; 72) | 1.07 | 334 | 4.34 |

| Egypt | 58 | 5.2 | (1.96, 3.34) | 3.19 (0.69; 3) | (0.94, 2.76) | 2.18 (0.36; 55) | 1.01 | 46 | 1.46 |

| Thailand | 126 | 48.4 | (1.56, 10.91) | 2.81 (0.16; 61) | (0.16, 4.05) | 2.03 (0.81; 65) | 0.78 | 38 | 1.38 |

| Philippines | 143 | 31.5 | (0.51, 6.80) | 1.58 (1.09; 45) | (0.39, 4.74) | 1.20 (0.53; 98) | 0.38 | 32 | 1.32 |

| Vietnam | 147 | 42.9 | (0.38, 8.06) | 0.95 (0.45; 63) | (0.14, 1.66) | 0.57 (0.24; 84) | 0.38 | 67 | 1.67 |

| Russia | 505 | 0.2 | (0.94, 0.94) | 0.94 (0; 1) | (0.66, 10.00) | 1.40 (0.44; 504) | −0.46 | 33 | 0.67 |

| Ukraine | 324 | 4.3 | (0.49, 1.48) | 0.80 (0.37; 14) | (0.37, 8.01) | 1.29 (0.31; 310) | −0.49 | 38 | 0.62 |

| China | 453 | 6.8 | (0.66, 16.42) | 1.64 (1.07; 31) | (0.33, 49.25) | 2.50 (1.64; 422) | −0.86 | 34 | 0.66 |

| Mexico | 134 | 1.5 | (1.25, 1.65) | 1.45 (0.20; 2) | (1.18, 5.64) | 2.98 (0.46; 132) | −1.53 | 51 | 0.49 |

| Turkey | 308 | 21.3 | (0.75, 3.99) | 1.37 (0.37; 66) | (2.49, 4.74) | 3.24 (0.37; 242) | −1.87 | 58 | 0.42 |

| Brazil | 119 | 0.0 | NA | NA (NA; 0) | (1.48, 8.37) | 2.83 (0.26; 119) | NA | NA | n/a |

| Indonesia | 215 | 0.0 | NA | NA (NA; 0) | (0.58, 2.42) | 1.16 (0.30; 215) | NA | NA | n/a |

Median absolute deviation (MAD) and sample size provided in parentheses. No illicit packs were identified from Brazil and Indonesia. Therefore, a difference in medians of price could not be assessed. The illicit pack sample size is small for Egypt, Mexico and Russia. NA = not available.

Throughout countries, we found considerable variation in the extent to which illicit cigarettes are sold at a premium price or at a discount relative to legal pack prices (Fig. 1). Median illicit cigarette prices were between 1.7 to as much as 5.5 times median legal pack prices across the six countries where illicit packs tended to cost more than legal packs. The difference in median price between legal and illicit packs as a percentage of the price of legal packs ranged from 32% in the Philippines to 455% in Bangladesh (Table 2). In the three countries where illicit packs tended to be cheaper than legal packs, median illicit prices were between 0.66 and 0.42 times the median legal pack prices.

To assess the robustness of these findings we calculated the median purchase price differences at the city level and across neighborhood SES levels. The city level results (Supporting information, Table S5) largely mirror the differences found at the country level. There are five exceptions. In China, the median illicit pack price was US$ 0.86 less than median legal pack price, but there was no difference in median prices in Beijing and Guangzhou and the one illicit pack purchased in Chengdu was twice the median legal pack price in that city. The price difference in Cebu City, Philippines which is a tax‐free zone (−0.10) and Hat Yai, Thailand, a city close to the country's border, (−0.08) was the opposite sign relative to the difference in median prices found in those countries.

The neighborhood SES results (Supporting information, Table S6) also largely mirror the country results. The two exceptions are packs purchased in the middle SES neighborhoods of China and the high SES neighborhoods of the Philippines. There is little difference between the illicit and legal median pack prices in these neighborhoods despite the lower median price for illicit packs in China and the higher median price for illicit packs in the Philippines.

In summation, the countries fall into three categories: countries where illicit cigarettes were not found frequently in retail settings (Brazil, Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia), countries where illicit cigarettes tend to be more expensive than legal cigarettes in retail settings (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam) and countries where illicit cigarettes tend to be less expensive than legal cigarettes in retail settings (China, Turkey, Ukraine).

Discussion

This study contributes to the literature on the price of legal and illicit cigarette packs in LMICs and, to our knowledge, is the first to assess systematically the relationship between price and pack legality in multiple LMICs using a standard protocol and actual purchase price data. We found a large variation across countries in terms of the price difference between legal and illicit cigarettes. While it was not the focus of our study, and the proportion of packs purchased should not be interpreted as the volume of illicit packs on the market, the fact that we were able to purchase a substantial number of illicit packs from formal retailers should be noted.

The methodology used in this study has limitations. The sample of packs does not represent the market share of brands in each country, as only one pack of each unique representation was purchased. Therefore, an analysis of price variation throughout packs of the same brand variant was not possible. Given the sample, inferential statistical testing was not possible. The variation observed across countries in terms of discordance between appropriate HWL and indication of tax paid, with Brazil accounting for the majority (seven of 11 packs), may be due to it being our pilot country and, as mentioned previously, we suspect that tax stamps may have fallen off during handling and transit. It was also not possible to verify whether the displayed health warnings were fake or if the indicators of tax paid were counterfeit, and therefore it is possible that some packs coded as legal packs were misclassified. In countries such as Russia, Brazil and Indonesia, which have been reported to have high rates of illicit cigarette trade 4, we would have expected to find illicit cigarettes in the retail environment. This suggests that illicit trade is kept separate from the retail environment or that it is more difficult to identify illicit cigarettes in those countries. At the time of data collection, a track and trace system was in place in Brazil and Turkey 29. Track and trace systems involve placing unique codes or stamps on each tobacco pack that offers access to information (for example, the location of manufacture and intended destination) and allows for monitoring and control of the movement of the product 5. Track and trace systems are a way to control the supply chain and investigate illicit trade 5. While Brazil and Turkey both use digital tax stamps 30, the differences observed between countries with regard to the number of packs categorized as illicit in Turkey and no illicit packs being found in Brazil, may be due to different levels of trace and trace security. Turkey updated its track and trace system in 2014, after data collection was completed 10. Additionally, beyond categorizing packs as illicit and legal, distinctions between categories such as legally imported, smuggled, counterfeit and illicit white cigarettes were not made during coding.

Strengths of the present study include the use of a common protocol throughout many countries and data from a broad sample of packs. Further, prices were obtained by actual purchase of cigarette packs from retailers and do not rely upon consumers' self‐report of how much they paid for their cigarettes which introduces recall bias and potential rounding of numbers. Retailers were instructed explicitly not to pass on any bulk discounts, coupons or other price promotions which were not offered to the regular consumer; this served to ensure that retail conditions were standard across packs and countries.

Results from this study focus upon the range of illicit cigarette prices, reporting on both premium brands as well as low‐priced products. Studies conducted in Europe have used extremely low prices to identify packs as illicit 17 Our study suggests that this criterion may not be valid for use in LMICs where illicit cigarettes are often sold at higher prices than legal cigarettes.

There are a number of potential reasons for our finding that in many countries examined, the average purchase price of illicit cigarettes was higher than legal cigarettes. In countries where a limited number of domestically manufactured brands are sold, smokers may be willing to pay a premium for foreign brands if they are deemed to be higher quality or are viewed as aspirational although this was not directly verifiable in our data. It is also possible that different brands of illicit cigarettes, i.e. cheap brands versus international brands, target different market segments. Additional explanations advanced in the literature but not directly verifiable with our data include differences in level of enforcement, the presence of organized crime 6 and tobacco industry involvement in smuggling operations as a way to penetrate new markets and reduce their tax liability 31, 32, 33, 34, 35. The exception that we found in cities where the price difference was the opposite sign relative to the difference in median prices found in corresponding countries may be due to their proximity to country borders and a tax‐free zone.

Our finding in six countries that illicit cigarette packs cost more than legal packs, at the median, should not be interpreted as a reason to maintain illicit tobacco in a market. In many of these countries, tobacco taxes are very low 36 and this results in extremely low prices for legal cigarettes. Tobacco taxes need to be increased in these countries while at the same time implementing the strategies outlined in the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control's Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products.

Declaration of interests

None.

Supporting information

Table S1 Number of cigarette packs (legal, illicit) purchased, by city and neighborhood.

Table S2 Number of cigarette packs collected and number of retailers from which purchase were made in each country and city.

Table S3 Prices in local currency for illicit and legal packs, standardized to 20 sticks per pack.

Table S4 Number of retailers from which legal and illicit cigarette packs were purchased, by socio‐economic status (SES).

Table S5 Median prices (US$) for illicit and legal packs, by city (in order visited).

Table S6 Median prices (US$) for illicit and legal packs, by neighborhood socio‐economic status (SES).

Acknowledgements

This study would not be possible without the entire TPackSS team, including our coders Ashley Conroy, Cerise Kleb, Adamove Osho and Laura Kroart. We also thank our reviewers for comments that greatly helped strengthen the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Brown, J. , Welding, K. , Cohen, J. E. , Cherukupalli, R. , Washington, C. , Ferguson, J. , and Clegg Smith, K. (2017) An analysis of purchase price of legal and illicit cigarettes in urban retail environments in 14 low‐ and middle‐income countries. Addiction, 112: 1854–1860. doi: 10.1111/add.13881.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2011: Warning about the Dangers of Tobacco [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44616/1/9789240687813_eng.pdf (accessed 15 November 2016) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6muX5gJ5f). [Google Scholar]

- 2. West R., Townsend J., Joossens L., Arnott D., Lewis S. Why combating tobacco smuggling is a priority. BMJ 2008; 337: 1028–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chaloupka F. J., Straif K., Leon M. E. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control 2011; 20: 235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Joossens L., Merriman D., Ross H., Raw M. The impact of eliminating the global illicit cigarette trade on health and revenue. Addiction 2010; 105: 1640–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization . Protocol to eliminate illicit trade in tobacco products [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/80873/1/9789241505246_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 10 July 2015) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6muYfr6Wm). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joossens L. Smuggling and cross‐border shopping of tobacco products in the European Union [internet]. London, UK: Health Education Authority; 1999. Available at: http://www.ash.org.uk/files/documents/ASH_256.pdf (accessed 10 July 2015) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6muZ7Ped6). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rowell A., Evans‐Reeves K., Gilmore A. B. Tobacco industry manipulation of data on and press coverage of the illicit tobacco trade in the UK. Tob Control 2014; 23: e35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith K. E., Savell E., Gilmore A. B. What is known about tobacco industry efforts to influence tobacco tax? A systematic review of empirical studies. Tob Control; 22: 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. British American Tobacco . Pricing and Tax [internet]. n.d. Available at: http://www.bat.com/tax (accessed 1 December 2016) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6muZQcZ5R). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chaloupka F. J., Edwards S. M., Ross H., Diaz M., Kurti M., Xu X. et al. Preventing and Reducing Illicit Tobacco Trade in the United States [internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/pdfs/illicit-trade-report-121815-508tagged.pdf (accessed 3 June 2016) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6muZul5kA). [Google Scholar]

- 11. WHO Framework on Tobacco Control . Combating the Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products From a European Perspective [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/fctc/publications/Regional_studies_paper_3_illicit_trade.pdf (accessed 3 June 2016) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6muaNuO4n). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Joossens L. Vietnam: smuggling adds value. Tob Control 2003; 12: 119–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kostova D., Chaloupka F. J., Yurekli A., Ross H., Cherukupalli R., Andes L. et al. A cross‐country study of cigarette prices and affordability: Evidence from the global adult tobacco survey. Tob Control 2014; 23: e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liber A. C., Ross H., Ratanachena S., Dorotheo E. U., Foong K. Cigarette price level and variation in five Southeast Asian countries. Tob Control 2015; 24: e137–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shang C., Chaloupka F. J., Zahra N., Fong G. T. The distribution of cigarette prices under different tax structures: Findings from the international tobacco control Policy Evaluation (ITC) project. Tob Control 2014; 23 Suppl 1: i23–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liber A. C., Ross H., Omar M., Chaloupka F. J. The impact of the Malaysian minimum cigarette price law: findings from the ITC Malaysia survey. Tob Control 2015; 24 Suppl 3: iii83–iii87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Joossens L., Lugo A., La Vecchia C., Gilmore A. B., Clancy L., Gallus S. Illicit cigarettes and hand‐rolled tobacco in 18 European countries: a cross‐sectional survey. Tob Control 2014; 23: e17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davis K. C., Grimshaw V., Merriman D., Farrelly M. C., Chernick H., Coady M. H. et al. Cigarette trafficking in five northeastern US cities. Tob Control 2014; 23: e62–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Consroe K., Kurti M., Merriman D., von Lampe K. Spring breaks and cigarette tax noncompliance: evidence from a New York City College sample. Nicotine Tob Res 2016; 18: 1773–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chernick H., Merriman D. Using littered pack data to estimate cigarette tax avoidance in NYC. Natl Tax J 2013; 66: 635–668. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Merriman D. The micro‐geography of tax avoidance: evidence from littered cigarette packs in Chicago. Am Econ J Econ Policy 2010; 2: 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith K., Washington C., Brown J., Vadnais A., Kroart L., Ferguson J. et al. The tobacco pack surveillance system: a protocol for assessing health warning compliance, design features, and appeals of tobacco packs sold in low‐ and middle‐income countries. JMIR Public Heal Surveill 2015; 1: e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Campaign for Tobacco‐Free Kids . Global Epidemic: Priority Countries [internet]. Washington, DC: n.d. Available at: http://global.tobaccofreekids.org/en/global_epidemic/country/ (accessed 21 July 2016) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6mubsBJqT). [Google Scholar]

- 24. XE XE Live Exchange Rates [internet]. Available at: www.xe.com (accessed 20 October 2013) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6muc9qCaP). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Egypt imposes stamp tax on cigarettes, price unchanged [internet]. Ahram Online. 21 Dec 2013. Available at: http://english.ahram.org.eg/News/89778.aspx (accessed 3 March 2015) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6mucRpLqX).

- 26. Wherry A. E., McCray C. A., Adedeji‐Fajobi T. I., Sibiya X., Ucko P., Lebina L. et al. A comparative assessment of the price, brands and pack characteristics of illicitly traded cigarettes in five cities and towns in South Africa. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e004562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ketchoo C., Sangthong R., Chongsuvivatwong V., Geater A., McNeil E. Smoking behaviour and associated factors of illicit cigarette consumption in a border province of southern Thailand. Tob Control 2013; 22: 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp, LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control . The protocol to eliminate illicit trade in tobacco products: questions and answers [internet]. n.d. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85380/1/9789241505871_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 13 November 2016) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6mue9tA8r).

- 30. Framework Convention Alliance . The Use of Technology to Combat The Illicit Tobacco Trade [internet]. Framework Convention Alliance; n.d. Available at: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache: KQ_uymVCQI8J:www.fctc.org/publications/bulletins/doc_download/124-technology-and-the-fight-against-illicit-tobacco-trade+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us (accessed 27 March 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 31. Collin J., Legresley E., MacKenzie R., Lawrence S., Lee K. Complicity in contraband: British American Tobacco and cigarette smuggling in Asia. Tob Control 2004; 13: ii104–ii111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee K., Collin J. ‘Key to the future’: British American Tobacco and cigarette smuggling in China. PLOS Med 2006; 3: 1080–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Legresley E., Lee K., Muggli M. E., Patel P., Collin J., Hurt R. D. British American Tobacco and the ‘insidious impact of illicit trade’ in cigarettes across Africa. Tob Control 2008; 17: 339–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakkash R., Lee K. Smuggling as the ‘key to a combined market’: British American Tobacco in Lebanon. Tob Control 2008; 17: 324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Joossens L., Raw M. Cigarette smuggling in Europe: who really benefits? Tob Control 1998; 7: 66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. World Health Organization . WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2013: Enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available at http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2013/en/ (accessed 2 March 2015) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6mudVvkSU). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Number of cigarette packs (legal, illicit) purchased, by city and neighborhood.

Table S2 Number of cigarette packs collected and number of retailers from which purchase were made in each country and city.

Table S3 Prices in local currency for illicit and legal packs, standardized to 20 sticks per pack.

Table S4 Number of retailers from which legal and illicit cigarette packs were purchased, by socio‐economic status (SES).

Table S5 Median prices (US$) for illicit and legal packs, by city (in order visited).

Table S6 Median prices (US$) for illicit and legal packs, by neighborhood socio‐economic status (SES).