Abstract

The DuPage Patient Navigation Collaborative (DPNC) adapted and scaled the Patient Navigation Research Program’s intervention model to navigate uninsured suburban DuPage County women with an abnormal breast or cervical cancer screening result. Recent findings reveal the effectiveness of the DPNC in addressing patient risk factors for delayed follow-up, but gaps remain as patient measures may not adequately capture navigator impact. Using semistructured interviews with 19 DPNC providers (representing the county health department, clinics, advocacy organizations, and academic partners), this study explores the critical roles of the DPNC in strengthening community partnerships and enhancing clinical services. Findings from these provider interviews revealed that a wide range of resources existed within DuPage but were often underused. Providers indicated that the DPNC was instrumental in fostering community partnerships and that navigators enhanced the referral processes, communications, and service delivery among clinical teams. Providers also recommended expanding navigation to mental health, women’s health, and for a variety of chronic conditions. Considering that many in the United States have recently gained access to the health care system, clinical teams might benefit by incorporating navigators who serve a dual working purpose embedded in the community and clinics to enhance the service delivery for vulnerable populations.

Keywords: access to health care, minority health, community-based participatory research, health disparities, breast cancer, cervical cancer

INTRODUCTION

Millions of low-income U.S. adults and recent immigrants fall into a “coverage gap” and remain uninsured (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013, 2014). DuPage County, adjacent to Chicago’s Cook County, has a growing low-income, uninsured population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). However, unlike its urban Cook County counterpart, suburban DuPage has only a limited health care safety net to meet the diverse needs of low-income residents. In 2001, community leaders established the Access DuPage (AD) program, a coalition of hospitals, physicians, local government agencies, human service agencies, and community organizations to provide access to an array of health services for uninsured DuPage residents. Although the uninsured had improved health care access through AD, gaps remain in the delivery of services, especially for cancer and other conditions that require careful coordination of local resources. The DuPage Patient Navigation Collaborative (DPNC), a community-based participatory research partnership between AD and Northwestern University, was developed in response to community leaders’ concerns that low-income women with abnormal breast and cervical screening results lacked supports essential to appropriate follow-up and treatment (Samaras et al., 2014).

BACKGROUND

Funded by a 5-year grant from the National Cancer Institute, the DPNC replicated the Patient Navigation Research Program (PNRP) intervention model—previously tested in multisite efficacy trials (Freund et al., 2008) including in Chicago (Nonzee et al., 2012). Adaptations were made to scale navigation to a county level and support health care for uninsured women through state-funded public health and DuPage volunteer organizations (Lobb et al., 2011). Designated as the DuPage County Illinois Breast and Cervical Cancer Program’s (IBCCP) primary referral option for women enrolled in AD, the DPNC navigator team navigated patients from March 2009 through December 2012. The DPNC navigator team consisted of six ethnically diverse bilingual (English/Spanish and English/Arabic) community navigators with complementary case management experience. Three navigators had master’s degrees in social work or public health as their highest educational attainment, two had bachelor’s degrees (including in social work), and one was a high school graduate (Phillips et al., 2014). Supervision of the navigation team was shared by AD and Northwestern University, with day-to-day coordination provided by a master’s degree–level staff member. All six navigators were full-time salaried employees of AD and received fringe benefits.

Navigators’ roles included making appointment reminder calls; providing informational, logistical, and emotional support; providing interpreter services; and referring patients to community human resource wrap-around services. DPNC community navigators moved freely across multiple clinics/hospitals linking patients with existing community resources and facilitating relationships among community partners. Prior to the start of the intervention, navigators received approximately 80 hours of extensive on-the-job training for this role, including resource and administrative training at AD, research administration at Northwestern, case manager shadowing at the DuPage Health Department, trainings facilitated through community partners, community health workers training, and the national PNRP/American Cancer Society training covering health disparities, role of navigators, cancer knowledge, culture and diversity, communication, introduction to clinical research, mapping resources, and resource management (Calhoun et al., 2010). In addition, navigators received weekly coaching from the investigator team, DuPage County service providers, and project coordinator for the first year of the intervention. For the remainder of the intervention period, navigators attended 1- to 2-hour educational sessions on a quarterly basis on topics such as nutrition, tobacco cessation, and treatment. They also participated in Affordable Care Act training and attended national public health conferences. Greater details about the navigation program are described elsewhere (Phillips et al., 2014).

The evaluation of the DPNC used PNRP timeliness metrics to examine median time to diagnostic resolution among a cohort of uninsured DuPage women receiving free breast or cervical cancer screening through IBCCP and had abnormal screening results. Results suggested that the navigation program was effective in facilitating access to care for these women. Median follow-up time compared favorably to external benchmarks despite the prevalence of timeliness risk factors, and no differences in likelihood of delayed follow-up between Spanish- and English-speaking patients were observed (Lobb et al., 2011). Despite these marks of success for the DPNC, evaluations of navigation programs have primarily focused on patient timeliness measures—time between abnormal screening results and follow-up or between diagnostic resolution and treatment (Battaglia et al., 2012; Caplan, May, & Richardson, 2000; Hoffman et al., 2012; Lawson, Henson, Bobo, & Kaeser, 2000; Markossian, Darnell, & Calhoun, 2012; Paskett et al., 2012; Raich, Whitley, Thorland, Valverde, & Fairclough, 2012; Wells et al., 2012). However, these metrics fail to capture how navigators shape the essential community relationships and health care infrastructure toward timely diagnosis and treatment for uninsured, underserved patients. Qualitative approaches, including interviews with DPNC providers, are necessary to illuminate elements such as a navigation program’s fit and interactions within a health care delivery system, patient navigators’ role as liaison between the community and service providers, and providers’ experiences with the program.

Following the DPNC navigation intervention, we conducted semistructured interviews with key DPNC providers to explore the navigation program’s impact on supporting the development of a county-level partnership and enhancing a health care safety net for uninsured suburban women with abnormal breast or cervical cancer screening results. Specifically, we present perspectives from the health care providers involved to describe how the DPNC navigation program strengthened community programs and partnerships and supported clinical service delivery. In addition, we present providers’ recommendations for future navigation program design.

METHOD

The social-ecological model (Knightbridge, King, & Rolfe, 2006) provided the framework to engage providers across multiple settings (i.e., community clinic, health department) and sectors (i.e., local government, academia, advocacy, private medical providers). Many of these sectors were represented in the DPNC’s community advisory board (CAB) and thus guided project implementation, advised on the study design and implementation, facilitated community buy-in, provided resources, and disseminated findings. Other individuals, such as health care providers with existing relationships with AD and the DuPage Health Coalition, were involved via their roles in delivery of care—providing screening, diagnostic, and treatment options and services for women enrolled in the navigation program.

Following completion of the intervention phase in December 2012, project investigators compiled a roster of DPNC providers to participate in individual interviews to assess their perspectives on the implementation and community impact of the navigation program. Eligible individuals who met the inclusion criteria were men and women 18 years and older who were members of the CAB and/or were medical providers, clinical staff, case managers and social workers, administrative support staff, and executives/directors representing DPNC partner organizations. Hereafter referred to as “providers,” these individuals represented the different elements of the DuPage County safety net. Patients and navigators were not interviewed in this process; their perspectives, including those regarding the navigator–patient relationship and stories from the field, are reported elsewhere (Livaudais et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 2014).

Three trained project staff members, including two of the authors (NH and SP), approached the providers via phone and e-mail between February and May 2013 to schedule in-person or phone interviews. Project staff verbally presented informed consent information, and once a provider provided consent, interviews were conducted using a semistructured interview guide. Motivated by principles of community-based participatory research that included building on the assets within the community, facilitating collaboration of community members, and using partner knowledge to develop action-oriented research (Lobb et al., 2011; Samaras et al., 2014), we organized our interview questions into four core areas: (1) provider’s relation to the patient navigation program, (2) navigation effectiveness, (3) connecting patients with navigators (e.g., the referral process), and (4) program implementation. Relation to patient navigation program included the providers’ affiliation, frequency of contact, type of contact, mutual benefits, and length of involvement with the navigation project. Navigation effectiveness questions touched on outcome measures, targeted populations, and the accessibility of the navigation program. Questions related to the referral process covered the successes and challenges of the hand-off process, that is, how the clinical team assessed the need of patients and referred them to patient navigators as needed. Program implementation questions addressed which components of the program worked well, which needed improvement, and design of future navigation projects. As these were interviews among DPNC providers, other than job title and affiliation, no participant demographic characteristics were collected. Interviews lasted 30 to 40 minutes and were recorded and transcribed by project staff. All participants received a $25 gift card. Study procedures were approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Using the constant comparative method (Glaser, 1965), the authors (ER, NH, SP) examined and coded the transcripts systematically. A priori codes based on the semistructured interview guide were used to develop an initial codebook. Coding via an inductive, constant comparative approach followed until themes emerged, using data analysis software Atlas.ti Version 6.2. Any new codes that were not initially part of the codebook but that emerged inductively through the coding process were added via consensus around concepts of interest that emerged from the data. Themes that emerged were grouped into three higher order thematic categories, generating the domains: (1) strengthening community partnerships, (2) enhancing clinical services, and (3) recommendations for future programing.

RESULTS

Participants’ Background

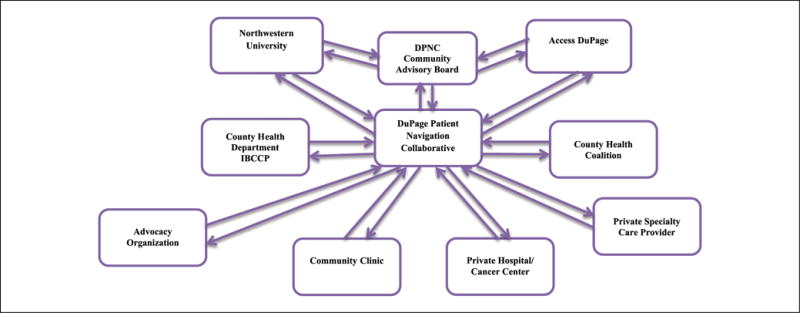

Nineteen DPNC providers were interviewed, representing the various sectors displayed in Table 1 and Figure 1. The rest could not be interviewed primarily due to scheduling conflicts, despite multiple contact attempts made during the 2-month qualitative study period. The extent of the providers’ relationships with the project included CAB membership, supervisory responsibilities of navigation team, and clinical partnerships (e.g., referral or care coordination activities). Providers reported weekly to monthly interaction with navigators, with contact occurring in person, by phone, or through e-mail. Providers gave valuable insights on the critical roles that the DPNC served in strengthening community partnerships and enhancing clinical services, as well as recommendations for the design of future programs.

TABLE 1.

Providers Interviewed (n = 19)

| Sectors | Providers |

|---|---|

| Health department | 2 Nurse practitioners |

| 2 Nurse case managers | |

| 1 Nurse | |

| 2 Directors/managers | |

| Community clinic | 1 Nursing director |

| 1 Social worker | |

| 1 Executive director | |

| Private hospital | 1 Oncology social worker |

| 1 Financial counselor | |

| 1 Breast surgeon | |

| 1 Nurse practitioner | |

| Private specialty care provider | 1 Physician assistant |

| 1 Physician | |

| 1 Officer manager/medical assistant | |

| Advocacy organization | 1 Patient services coordinator |

| Countywide health coalition | 1 President |

FIGURE 1. Relationship Among the DuPage Patient Navigation Collaborative Providers Interviewed.

NOTE: DPNC = DuPage Patient Navigation Collaborative; IBCCP = Illinois Breast and Cervical Cancer Program.

Strengthening Community Programs and Partnerships

At DPNC project inception, we elected to make strengthening community linkages a priority, intending that the project be well integrated into a preexisting collaborative framework. Providers noted that the study was “well designed from start and had [the] right partners at [the] table.” They perceived that DPNC’s collaborative focus facilitated dialogue and more efficient utilization of community resources. As one provider summarized, “We worked off of each other’s skills.” For example, the Why Wait Program (WWP), an IBCCP-funded program offering free breast and cervical cancer screening tests, was a primary resource for patient study recruitment. WWP representatives noted that referring patients for DPNC navigation services enabled them to better serve a high-risk population while freeing up limited resources to serve more clients. Likewise, a health department staff member highlighted that navigators “would [provide patients] with the support that I couldn’t.” Others also highlighted that navigators enhanced support available by directly following up with patients and generally bridging communication among collaborative team members: “Tracking so many people is hard but the PN really helped me out keeping me updated on patients’ status.”

Navigators also managed the often challenging and time intensive efforts to address nonclinical care barriers to treatment. One provider recalls,

I don’t believe I could have done my job effectively without the assistance of the patient navigators […] We had a patient who did not have money for food, shelter, the children were having problems in school … the patient navigator advocated for the patient at the school and at the homeless shelter to help minimize the obstacle of that woman getting to this and that medical appointment.

A provider from the county health department suggested that the DPNC boosted the AD health care safety net, such that “a patient had access to more resources when they were enrolled in AD [now].” Another example of the DPNC increasing linkages to and utilization of community resources is described by a provider from the local American Cancer Society:

The [navigation] program has benefited me by bringing more patients, helping me get comfortable with the language line. We’ve helped them through the road to recovery program, gave patients rides or wigs—[sometimes the] navigator would accompany patients to get their wigs.

A cross-referral process was cited by providers as a strength of this collaborative partnership, as it lever-aged existing services to create cohesiveness. First, it facilitated patient enrollment into other programs and community resources. Second, it expanded the network of providers and thus available services and resources for women enrolled in the DPNC—a provider noted, for example—that partners were generous in accepting referrals of AD patients, especially those in need of specialty care services. Leveraging community resources was perceived by providers as critical, especially during periods of state fiscal instability:

We have greatly benefitted by putting many more of our grant and local tax dollars toward actually serving the women enrolled in the program […] [The program] freed up our staff and our resources to bring in more women [for screenings].

Even initially skeptical partners came to see the program as a resource:

Some of gynecologists and breast specialists were initially unclear on [the] role of navigation and did not see utility [because they] saw it as role that made them more distant from patients in a way that they didn’t wish. [They] came to see [the navigation program] ultimately as having a lot of benefits and [the specialists] looked to patient navigators as resource[s] in a way that they did not in week one.

Enhancement of Clinical Services

In addition to strengthening community partnerships and programs, providers noted that navigators embedded in clinical teams formed strong working relationships with physicians, clinic staff, and support staff, which translated to better teamwork, effective communication, and staff meeting their full clinical capabilities. With respect to teamwork, providers believed that the flexibility of the DPNC referral process allowed providers to make ongoing adjustments and meet the needs of clinical teams. For example, several providers elected to introduce patient navigation services at the screening stage, while others preferred the point when patients were symptomatic/presented abnormality and needed diagnostic testing. In addition, providers indicated that the navigation program enhanced communication in the clinical setting. Trust increased as the program progressed, as providers began to rely more on navigators to communicate specific information to patients as well as to maintain ongoing communications:

We would ask [navigators] for the status updates that is, did you get a hold of the patient? What were the results of the appointment? What are the next steps? […] It wasn’t like I referred the patient to the patient navigator and that was the end of it.

Several providers reported that the navigators enabled clinicians to work to their full clinical capabilities, supporting clinical teams for example, by providing insight to patients’ personal circumstances. As one provider described,

When I get a new patient who has already been working with a patient navigator, the navigator is able to give me a lot of insight as to the family dynamics, the home situation, language barriers, etc. It makes my job much easier.

As noted by another provider: “The case managers and nurses are overworked, so the navigators really helped.” Several providers also described that through the program, they became aware of community resources for patients. Due to time constraints, they often could not facilitate these services themselves, but they were assured that navigators could help address patient concerns. Providers also indicated that navigators supported them by regularly supplementing the information patients received in the clinic. This component was critical because “provider visits are often too brief and patient navigators explain what they heard from the doctor and address questions.”

Providers suggested that navigation services were particularly beneficial to immigrants with limited English proficiency, individuals with limited exposure to the health care system, those with mental health conditions, and the elderly. Providers noted, for example, that patients with language barriers and limited exposure to the health care system often needed direct hands-on assistance (i.e., scheduling appointments, interpreting) as well as emotional support, since they “don’t seem to know enough or what questions to ask.” Providers noted that patients with emotional or behavioral health problems especially benefited from navigation because their conditions often interfered with their decision-making ability, while seniors benefited more from navigation than younger patients because of their isolation and reduced access to information on the web and other sources.

Recommendations for the Future-Program Design and Focus

Overall, providers recognized the advantages of leveraging the established safety net infrastructure and recommended a continued partnership with AD to address the medical needs of low-income DuPage women. In addition, they believed that navigation would benefit other clinical care areas and recommended expanding navigation to other cancers, chronic conditions, mental health, and women’s health. Given the “learning curve for diabetics,” one suggestion was for a diabetes clinic where navigators could work with patients early on in their diagnosis. One provider indicated that while some services were available, case coordination and management were largely unavailable for women’s and mental health needs. One stakeholder recommended,

Any population where you have people with complex needs that have to be coordinated across multiple sites and providers, [often requires] different options of care provision. Care management makes sense and patient navigation [should/must be] a subset of care management.

Although providers had mostly positive views of the navigator program, they did provide recommendations for improvement in areas related to gaps in services after the intervention period, burden of collecting data, and staff turnover. Providers reported that since the end of the intervention period, more patients were not following up with appointments. Clinic staff reported that they were unable to give patients the time previously provided by patient navigators: “My phone calls are very short and I don’t have time to establish a relationship with them. My caseload is out of control.” Toward that end, providers recommended that future initiatives should incorporate supplementary community education and outreach efforts to educate the broader community, particularly in the self-management of chronic conditions. To support their work, a provider indicated that the community resource guide, which was a great resource for patients, should be updated regularly, even after the intervention period. Some providers expressed concerns about the navigator program’s data collection burden. One provider raised that “[It] takes time to keep accurate record and make assessments” and another provider recommended that data collection process should be streamlined. Regarding administrative and clinical staff turnover, one provider recommended, “Ongoing training is essential, maybe quarterly to keep everybody up to speed.”

DISCUSSION

A wide range of resources exist within DuPage, but limited connectivity between resources and underutilization among both patients and providers set the stage for a navigation program that bridges DuPage voluntary organizations and state-funded public health providers to reduce barriers to breast and cervical screening and follow-up care for uninsured immigrant women. Findings from provider interviews revealed that the DPNC strengthened community partnerships and enhanced referral processes, communications, and service delivery among clinical teams. Providers spoke highly of the program and provided recommendations for future patient navigation programming.

Our findings suggest that the DPNC served a central role facilitating conversations and linkages among diverse partners to strengthen suburban DuPage’s health care safety net. This is a significant step toward an elusive one-stop shop model for health and wrap around services, which may particularly benefit under-served patients (Allen et al., 2013). However, as noted by our providers, engaged civic leadership and selecting the right partners at program onset are essential. Fortunately, we learned that health care providers were receptive to collaborating, and in time, those initially skeptical acknowledged that community navigators were assets that enhanced service delivery. This is consistent with findings from studies suggesting that navigators spend a significant portion of their time facilitating patient–provider communication (Clark, Parker, Battaglia, & Freund, 2014; Gabitova & Burke, 2014). As health care providers are often pressed to schedule shorter consultations (Mechanic, McAlpine, & Rosenthal, 2001; Wilson & Childs, 2002), navigators can help optimize providers’ interactions with the underserved patients who often need more dedicated time to address their complex needs (Anderson & Larke, 2009). Moreover, the health care delivery system is increasingly fragmented (Anhang Price, Zapka, Edwards, & Taplin, 2010; Cebul, Rebitzer, Taylor, & Votruba, 2008; Garber & Skinner, 2008), so providers’ perception that navigation was especially beneficial to patients who experience complex barriers to accessing the medical system also speaks to the promise of navigators in fostering patient-centered care.

Yet findings from this study also raise issues regarding the sustainability of patient navigation. After the intervention period, some community partners struggled to meet their program objectives, and clinical teams were unable to fulfill the many roles navigators served. Navigation can be a costly (Bensink et al., 2014), resource-intensive endeavor that extends beyond direct coordination of care to a range of tasks associated with health system repair (Clark et al., 2014), so identifying how to transition patients from initial high-intensity navigator interaction to low-level interaction characterized by longer term peer support or self-management is an important next step for navigator research. We learned that some service providers felt a heavy burden from the navigation project’s data collection process. So, despite the merits of using data collection protocols from existing PNRP studies, it is important to continuously assess the time constraints of service providers to ensure that the research instruments are appropriate for this group of stakeholders. Finally, further research on the cost-effectiveness/cost–benefit of navigators may assist in securing navigator funding to maintain their role on the medical team.

Limitations of this study include potential for social desirability bias from interviewing providers directly involved in the project. Provider interviews provided observations about the program’s partnership building activities, but additional research using social network analysis and outreach metrics (Hunt, Allgood, Sproles, & Whitman, 2013; Knoke & Yang, 2008) could further our understanding of the community impact of the navigation program. Another limitation is that providers had varying lengths of involvement with the overall project, although we believe this provided a nuanced portrayal of the DPNC relevant for future dissemination settings that may feature providers of varying involvement. A third limitation is that the study was conducted in a suburban setting, so results may not generalize to other regions. Future research is needed among different community contexts.

We find providers enthusiastic about expanding navigation to other health conditions, mental health, and women’s health. National data call attention to diabetes and mental health as two areas of concern, especially among Latino populations. Community health worker interventions have demonstrated efficacy in managing chronic conditions such as diabetes, depression, and stress among immigrants (Carrasquillo, Patberg, Alonzo, Li, & Kenya, 2014; McCloskey, 2009; Tran et al., 2014). Considering the millions of previously uninsured or underinsured Americans who have recently gained access to the health care system, clinical teams might benefit by incorporating navigators who serve a dual working purpose embedded in the community and in clinical teams.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, DPNC service providers reflected positively on the navigation program, citing positive benefits to both the community and clinical settings, and desire to see navigation services expanded to other settings. As navigation initiatives expand to other arenas and into larger roles in the health care delivery system, it is important to continually engage community providers and leverage community resources. Millions of Americans have been able to access medical insurance through reform, but large segments of the most vulnerable populations will continue to remain uninsured and will continue to rely on services provided by regional and voluntary organizations.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ Note: We gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for their many contributions to this project: Narissa Nonzee, Charito Bularzik, Kara Murphy, and Richard Endress. We also thank our community advisory board members, Access DuPage, the DuPage County Health Department, and our study participants. This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R24 MD001650).

References

- Allen JD, Mars DR, Tom L, Apollon G, Hilaire D, Iralien G, Zamor R. Health beliefs, attitudes and service utilization among Haitians. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2013;24:106–119. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JE, Larke SC. Navigating the mental health and addictions maze: A community-based pilot project of a new role in primary mental health care. Mental Health in Family Medicine. 2009;6(1):15–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anhang Price R, Zapka J, Edwards H, Taplin SH. Organizational factors and the cancer screening process. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2010;2010:38–57. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia TA, Bak SM, Heeren T, Chen CA, Kalish R, Tringale S, Freund KM. Boston Patient Navigation Research Program: The impact of navigation on time to diagnostic resolution after abnormal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012;21:1645–1654. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensink ME, Ramsey SD, Battaglia T, Fiscella K, Hurd TC, McKoy JM, Mandelblatt S. Costs and outcomes evaluation of patient navigation after abnormal cancer screening: Evidence from the Patient Navigation Research Program. Cancer. 2014;120:570–578. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun EA, Whitley EM, Esparza A, Ness E, Greene A, Garcia R, Valverde PA. A national patient navigator training program. Health Promotion Practice. 2010;11:205–215. doi: 10.1177/1524839908323521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan LS, May DS, Richardson LC. Time to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: Results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1991–1995. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:130–134. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo O, Patberg E, Alonzo Y, Li H, Kenya S. Rationale and design of the Miami Healthy Heart Initiative: A randomized controlled study of a community health worker intervention among Latino patients with poorly controlled diabetes. International Journal of General Medicine. 2014;7:115–126. doi: 10.2147/ijgm.s56250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebul RD, Rebitzer JB, Taylor LJ, Votruba M. Organizational fragmentation and care quality in the US health care system. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2008. Aug, (NBER Working Paper No. 14212). Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w14212.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clark JA, Parker VA, Battaglia TA, Freund KM. Patterns of task and network actions performed by navigators to facilitate cancer care. Health Care Management Review. 2014;39:90–101. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31828da41e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, Dudley DJ, Fiscella K, Paskett E, Roetzheim RG. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: Methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008;113:3391–3399. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabitova G, Burke NJ. Improving healthcare empowerment through breast cancer patient navigation: A mixed methods evaluation in a safety-net setting. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:407. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber AM, Skinner J. Is American health care uniquely inefficient? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2008. Aug, (NBER Working Paper No. 14257). Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w14257.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems. 1965;12:436–445. [Google Scholar]

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Characteristics of poor uninsured adults who fall into the coverage gap. 2013 Retrieved from https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/8528-characteristics-of-poor-uninsured-adults-who-fall-into-the-coverage-gap.pdf.

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The coverage gap: Uninsured poor adults that do not expand medicaid. 2014 Retrieved from https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/8505-the-coverage-gap_uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid.pdf.

- Hoffman HJ, LaVerda NL, Young HA, Levine PH, Alexander LM, Brem R, Patierno SR. Patient navigation significantly reduces delays in breast cancer diagnosis in the District of Columbia. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012;21:1655–1663. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt BR, Allgood K, Sproles C, Whitman S. Metrics for the systematic evaluation of community-based outreach. Journal of Cancer Education. 2013;28:633–638. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0519-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knightbridge SM, King R, Rolfe TJ. Using participatory action research in a community-based initiative addressing complex mental health needs. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoke D, Yang S. Social network analysis. Vol. 154. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson HW, Henson R, Bobo JK, Kaeser MK. Implementing recommendations for the early detection of breast and cervical cancer among low-income women. MMWR Recommendation and Reports. 2000;49(RR-2):37–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livaudais JC, Coronado GD, Espinoza N, Islas I, Ibarra G, Thompson B. Educating Hispanic women about breast cancer prevention: Evaluation of a home-based promotora-led intervention. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:2049–2056. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb R, Opdyke KM, McDonnell CJ, Pagaduan MG, Hurlbert M, Gates-Ferris K, Allen JD. Use of evidence-based strategies to promote mammography among medically underserved women. American Journal of Prevention Medicine. 2011;40:561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markossian TW, Darnell JS, Calhoun EA. Follow-up and timeliness after an abnormal cancer screening among underserved, urban women in a patient navigation program. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012;21:1691–1700. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey J. Promotores as partners in a community-based diabetes intervention program targeting Hispanics. Family Community Health. 2009;32(1):48–57. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000342816.87767.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, McAlpine DD, Rosenthal M. Are patients’ office visits with physicians getting shorter? New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:198–204. doi: 10.1056/nejm200101183440307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonzee NJ, McKoy JM, Rademaker AW, Byer P, Luu TH, Liu D, Simon MA. Design of a prostate cancer patient navigation intervention for a Veterans Affairs hospital. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:340. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskett ED, Katz ML, Post DM, Pennell ML, Young GS, Seiber EE, Murray DM. The Ohio Patient Navigation Research Program: Does the American Cancer Society patient navigation model improve time to resolution in patients with abnormal screening tests? Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012;21:1620–1628. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips S, Nonzee N, Tom L, Murphy K, Hajjar N, Bularzik C, Simon MA. Patient navigators’ reflections on the navigator-patient relationship. Journal of Cancer Education. 2014;29:337–344. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0612-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raich PC, Whitley EM, Thorland W, Valverde P, Fairclough D. Patient navigation improves cancer diagnostic resolution: An individually randomized clinical trial in an underserved population. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012;21:1629–1638. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaras AT, Murphy K, Nonzee NJ, Endress R, Taylor S, Hajjar N, Simon MA. Community-campus partnership in action: Lessons learned from the DuPage County Patient Navigation Collaborative. Program in Community Health Partnerships. 2014;8(1):75–81. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran AN, Ornelas IJ, Kim M, Perez G, Green M, Lyn MJ, Corbie-Smith G. Results from a pilot promotora program to reduce depression and stress among immigrant Latinas. Health Promotion Practice. 2014;15:365–372. doi: 10.1177/1524839913511635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2008–2012 American Community Survey. 2014 Retrieved from http://www2.census.gov/acs2012_5yr/summaryfile/ACS_2008-2012_SF_Tech_Doc.pdf.

- Wells KJ, Lee JH, Calcano ER, Meade CD, Rivera M, Fulp WJ, Roetzheim RG. A cluster randomized trial evaluating the efficacy of patient navigation in improving quality of diagnostic care for patients with breast or colorectal cancer abnormalities. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2012;21:1664–1672. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Childs S. The relationship between consultation length, process and outcomes in general practice: A systematic review. British Journal of General Practice. 2002;52:1012–1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]