Abstract

Psoriasis is caused by a complex interplay between the immune system, psoriasis-associated susceptibility loci, psoriasis autoantigens, and multiple environmental factors. Over the last two decades, research has unequivocally shown that psoriasis represents a bona fide T-cell mediated disease primarily driven by pathogenic T-cells that produce high levels of IL-17 in response to IL-23. The discovery of the central role for the IL-23/T17 cell axis in the development of psoriasis has led to a major paradigm shift in the pathogenic model for this condition. The activation and upregulation of IL-17 in pre-psoriatic skin produces a “feed forward” inflammatory response in keratinocytes that is self-amplifying and drives the development of mature psoriatic plaques by inducing epidermal hyperplasia, epidermal cell proliferation, and the recruitment of leukocyte subsets into the skin. Clinical trial data for monoclonal antibodies against IL-17 signaling (secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab) and newer IL-23p19 antagonists (tildrakizumab, guselkumab, and risankizumab) underscore the central role of these cytokines as predominant drivers of psoriatic disease. We are currently witnessing a translational revolution in the treatment and management of psoriasis. Emerging bispecific antibodies offer the potential for even better disease control, while small molecule drugs may offer future alternatives to the use of biologics and less costly long-term disease management.

Keywords: Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, autoantigens, interleukin-17, interleukin-23, secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, tildrakizumab, guselkumab, and risankizumab

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis vulgaris is a common, chronic inflammatory condition of the skin that affects 2–3% of individuals in the United States.1 Plaque psoriasis, the most common disease variant seen in ~85% of cases, commonly manifests as erythematous plaques with thick scale on the extensor surfaces, trunk, and scalp.2 The severity of psoriasis ranges from mild disease with a limited number of localized inflammatory skin lesions to more severe disease involving widespread plaques that cover more than 10% of the body surface area. Approximately one-third of patients with chronic disease go on to develop psoriatic arthritis, an inflammatory arthritis characterized by asymmetric oligoarthritis, nail disease, enthesitis, and/or dactylitis.3 Other less common psoriasis subtypes include erythrodermic, pustular, guttate, inverse, and palmoplantar psoriasis. The economic burden associated with the care of patients affected by psoriasis is significant and accounts for billions of dollars spent annually in the United States alone.4 As is seen with other chronic medical conditions, psoriasis patients report a tremendous psychosocial burden and experience a significant reduction in their physical activity, cognitive function, and quality of life.5

The etiology of psoriasis is complex and driven primarily by an aberrant immune response in the skin that is modified by genetic susceptibility and various environmental stimuli (e.g. skin trauma, infections, and medications). The detrimental inflammatory events associated with psoriatic disease are not restricted to the skin and account for an increasing number of comorbid conditions, including cardiometabolic disease, stroke, metabolic syndrome (obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes), chronic kidney disease, gastrointestinal disease, mood disorders, and malignancy.6 These disease-associated comorbidities account, in part, for the increased mortality seen in patients with psoriasis and have substantial implications on disease management.7, 8

In the last decade, research discoveries have significantly expanded our understanding of the pathophysiology of psoriasis and have directly led to the development of highly-effective, targeted psoriasis therapies such as those against interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-23. The superiority of these novel agents compared to traditional systemic agents underscore the central importance of the IL-23/type 17 T-cell (T17) axis in psoriatic disease. In this review, we will discuss recent updates in our working model of psoriasis pathogenesis, outline the effects of IL-23/T17 axis signaling on skin biology, and provide an overview of the development and clinical testing of IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis and related chronic inflammatory skin conditions.

PSORIASIS AS A T-CELL MEDIATED, AUTOIMMUNE CONDITION

The requirement of the immune response for the development of psoriasis was suggested by early observations that characteristic skin lesions contained increased numbers of inflammatory cellular infiltrates.9, 10 Additionally, psoriasis patients undergoing bone marrow transplants11 or treatment with immunosuppressive agents like cyclosporine12, 13 and methotrexate14 experienced dramatic improvements in their inflammatory skin lesions. Subsequent experiments found that the inflammatory infiltrate in lesional skin was largely composed of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells.9, 15 However, selective inhibition of activated T-cells in patients via a novel fusion protein made of human IL-2 and diphtheria toxin fragments (DAB389IL-2) provided definitive proof for the pathogenic role of T-cells in psoriasis.16 Multiple proof-of-concept clinical trials targeting the activated immune response in psoriatic skin using abatacept (fusion protein of the Fc region of the immunoglobulin IgG1 and the extracellular domain of CTLA-4),17 alefacept (CD2-directed LFA-3/Fc fusion protein),18 and efalizumab (a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against CD11a)19 also proved effective in reversing the psoriasis phenotype and further established the role of the T lymphocyte in this condition. Such studies laid the groundwork for subsequent clinical trials aimed at other aspects of the immune response and the specific cell signaling pathways outlined in greater detail below.

The mounting evidence for the pathogenic role of the T lymphocyte in psoriasis and the observation that disease was more frequently observed in familial clusters20, 21 led many to conclude that psoriasis was an autoimmune condition with a strong genetic basis. Early genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in the 1980s revealed multiple psoriasis-associated susceptibility loci, the strongest of which was the human leukocyte antigen locus (HLA-C*06:02).22 Since that time, 63 unique susceptibility loci have been identified in psoriasis patients of European descent,23 though these loci only explain approximately 50% of the heritability of psoriasis. Additionally, the absence of expanded T-cell receptor (TCR) clones24 and the failure to identify any consistent exogenous or self-antigens caused others to question the autoimmune basis of psoriasis. However, the recent identification of three psoriasis autoantigens and their potential role in the pathogenesis of this condition has renewed interest in the autoimmune hypothesis.25

Psoriasis Autoantigens

In a recent study of 56 patients, Lande et al.26 found that the peripheral blood in 75% of psoriasis subjects with moderate-to-severe psoriasis contained autoreactive CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells against LL-37/cathelicidin, a cationic antimicrobial peptide (AMP) produced by keratinocytes and other immune cells (e.g. neutrophils) in response to bacterial/viral infections27, 28 or skin trauma.29 The cytokine profile of these autoreactive T-cells revealed increased levels of skin homing receptors (e.g. CLA, CCR6, and CCR10) and a strong IFN-γ and IL-17 phenotype consistent with previous studies examining the T-cell populations found in psoriatic skin.30 Importantly, the authors also showed that LL-37 expression is upregulated in psoriatic plaques, correlates with disease activity, and results in the direct activation of plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells (pDCs and mDCs, respectively) by forming a complex with nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) released following skin trauma.29, 31 These multimeric LL-37-nucleic acid complexes are protected from enzymatic degradation and enter DCs by way of specific toll-like receptors (TLRs). LL-37-mediated activation of DCs in the skin results in the over-production of type I interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β) by pDCs and increased amounts of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-6 by mDCs.31, 32 A similar mechanism for pDC activation has also been described for hBD2, hBD3, and lysozyme.33 This mechanism wherein one or more AMPs released by keratinocytes and other immune cells in response to skin damage or external stimuli provides a framework for how these proteins can break tolerance and promote autoimmunity in individuals with psoriasis.

In 2015, a second potential psoriasis autoantigen, ADAMTSL5, was described by Arakawa et al.34 ADAMTSL5 (also known as a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5 or ADAMTS-like protein 5) is a secreted zinc metalloprotease-related protein35 thought to regulate components of the extracellular matrix.36 Using a reconstituted TCR of an epidermal CD8+ T-cell clone collected from a HLA-C*06:02-positive psoriasis patient, Arakawa et al.34 observed that HLA-C*06:02-restricted melanocytes resulted in TCR activation. The authors also observed a close spatial association between CD8+ T-cells and HLA-C*06:02-restricted melanocytes, which were found to express increased amounts of ADAMTSL5. These findings suggest that the increased number of ADAMTSL5-expressing melanocytes in HLA-C*06:02-positive patients may serve as direct autoimmune targets for pathogenic T17 cell populations in psoriatic skin. This hypothesis is further supported by the finding that ADAMTSL5 stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from psoriasis patients, regardless of HLA-C*06:02 status, resulted in increased expression of IL-17A and IFN-γ in approximately two-thirds of patients compared to healthy controls.34 Importantly, recent results from our laboratory suggest that the possibility of ADAMTSL5 antigen presentation and the subsequent activation of IL-17-producing T-cells in psoriatic skin may involve other immune cell populations, such as keratinocytes and dendritic cells.37, 38

Most recently, PLA2G4D (phospholipase A2 group IVD) was reported as a possible psoriasis autoantigen.39 Unlike related phospholipase enzymes, PLA2G4D is a novel protein found to be upregulated in psoriatic plaques.40, 41 Its expression is elevated in psoriatic keratinocytes and mast cells, and results in the generation of non-peptide, neolipid antigens that are presented on CD1a-expresseing DCs for recognition by autoreactive T-cells.39 These autoreactive T-cells were also found to be enriched in the peripheral blood of psoriasis patients and produced high amounts of IFN-γ and IL-17A when co-incubated with PLA2G4D and CD1a-expressing cells. Unexpectedly, PLA2G4D activity was shown to localize with tryptase in mast cells, and neolipid antigens could be transferred to neighboring antigen presenting cells via mast-cell derived exosomes in a clathrin-dependent manner.39 Theses findings provide convincing evidence for the immunogenicity of non-protein, lipid antigens in psoriasis in addition to traditional peptide antigens such as LL-37 or ADAMTSL5.

In summary, the requirement for T-cells in the development of psoriasis is undeniable. However, the precise mechanisms by which environmental factors and known susceptibility loci trigger the onset of psoriasis is not well understood. The link between psoriasis-related autoreactive T-cells and distinct HLA-restricted autoantigens provides a possible mechanism for disease onset in predisposed individuals. It may also help explain why increased numbers of CD1a+ T-cells found in the peripheral blood of psoriasis patients are also positive for cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA+). Unfortunately, little is known about the exact immune events leading to the loss of immune tolerance in individuals susceptible to psoriasis. It is essential that future studies further explore these molecular mechanisms and carefully characterize the expression profiles of potential autoantigens in all cell types found in the skin and blood of psoriasis patients,38 as well as their relationship to major psoriasis susceptibility loci.

THE PIVOTAL ROLE OF IL-17 IN UPDATED DISEASE MODELS OF PSORIASIS

For many years, psoriasis was primarily characterized as a Th-1 driven disease based on the increased production of IFN-γ by CD4+ T-cells found in psoriatic tissues compared to low production of cytokines that define the Th-2 T-cell subset (i.e. IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13). However, with the characterization of a novel Th17 cell subset discovered in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mouse model commonly used to study multiple sclerosis,42 the field of dermatology research experienced a major paradigm shift in the way chronic inflammatory diseases of the skin were defined. This murine Th17 subset was characterized by its production of IL-17 and IL-22 by CD4+ T-cells. Ultimately, it was discovered that IL-17 blockade results in complete reversal of the molecular and clinical disease features seen in the majority of psoriasis patients, thus placing IL-17 and IL-17-producing T-cells at the center of the current disease model for psoriatic disease (Figure 1). Of note, most IL-22 is synthesized by a distinct Th22 T-cell subset in humans.

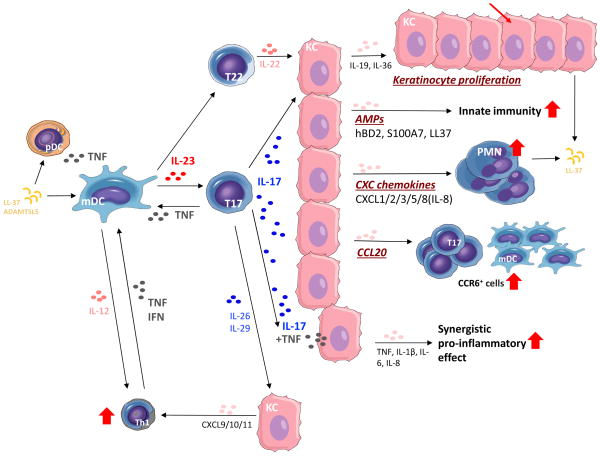

Figure 1. IL-23/T17-mediated effects on epidermal keratinocytes in psoriatic skin.

Schematic showing the broad downstream effects of increased IL-23 and IL-17 signaling on various immune cell populations and keratinocyte biology. Regulated by IL-23, the primary effects of IL-17 on keratinocytes include the indirect induction of epidermal hyperplasia via IL-19 and IL-36, upregulation of the innate immune response and antimicrobial peptides (e.g. hBD2, S100A7, and LL-37), epidermal recruitment of leukocyte subsets (e.g. neutrophils and myeloid dendritic cells/mDCs) via increased production of keratinocyte-derived chemokines, and transcription of multiple pro-inflammatory genes (e.g. TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) that act synergistically with TNF to sustain the inflammatory events in psoriatic skin.

A number of cell types found in the skin make IL-17, including CD4+ T cells (Th17), CD8+ T cells (Tc17), innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), and γδ T cells.43–45 IL-17 production in these cells is “driven” by IL-23, which is principally made by dermal DCs. Following presentation of specific psoriasis autoantigens and/or certain environmental stimuli (e.g. trauma or infection) in the pre-psoriatic skin, T17-producing cells in the skin produce substantial amounts of IL-17 (IL-17A/IL-17F), as well as TNF, IL-26, and IL-29 (IFN-λ1).46 Together, these cytokine signals create a “feed forward” inflammatory response in keratinocytes by activating CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPβ) or delta (C/EBPδ), signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB), which lead to the upregulation of a number of keratinocyte-derived inflammatory products (Figure 2). This “feed forward” response is self-amplifying and, ultimately, drives the development of mature psoriatic plaques by inducing epidermal hyperplasia, regulating epidermal cell proliferation, and recruiting leukocyte subsets into the skin. IL-17 also acts synergistically with TNF to potentiate IL-17-induced transcription of several pro-inflammatory genes (e.g. TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8),47–50 which activate mDCs and promote the differentiation of T17 cells in the skin and draining lymph nodes.32, 51

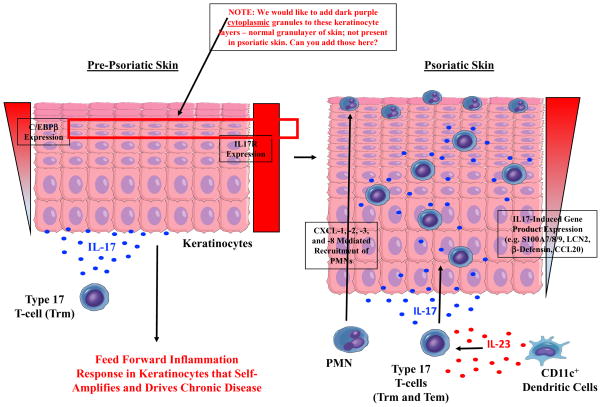

Figure 2. IL-17-driven initiation of feed forward inflammation in keratinocytes and the induction of psoriatic plaques.

A working model of psoriasis showing the activation and upregulation of IL-17 in a Type 17 resident memory T-cell (Trm) in pre-psoriatic skin. The increased production of IL-17 results in activation of the IL-17 receptor (IL17R) on viable keratinocytes and a “feed forward” inflammatory response via activation of IL-17-induced transcription factors (e.g. CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein beta, C/EBPβ). This “feed forward” inflammatory response in keratinocytes is self-amplifying and promotes the development of mature psoriatic plaques via the recruitment of pathogenic immune cells and over-production of IL-17-induced keratinocyte-derived gene products (e.g. S100A7/8/9, human β-defensin 2/hBD2, lipocalin-2/LCN2, and CCL20), which are noticeably increased in the upper layers of the epidermis, and also epidermal hyperplasia. A granular layer can be absent in mature psoriasis lesions, leading to retained nuclei in surface corneocytes (i.e. parakeratosis).

Epidermal hyperplasia, a hallmark of psoriatic plaques, is associated with STAT3 activation and indirectly regulated by IL-17 through the induction of IL-19 and/or IL-36 by keratinocytes.46 The increased proliferation of epidermal keratinocytes is likely further potentiated by IL-22, and possibly IL-20, as both of these cytokines are also activators of STAT3.52, 53 This marked thickening of the rapidly proliferating epidermis is accompanied by retention of the keratinocyte nucleus (parakeratosis), as well as upregulation of IL-17-induced transcription factors (e.g. C/EBPβ or C/EBPδ) and keratinocyte-derived gene products such as S100A7/8/9, human β-defensin 2 (hBD2), lipocalin-2 (LCN2), and CCL20.54 These keratinocyte-derived proteins accumulate and are noticeably increased in the upper spinous and granular layers of the epidermis of psoriatic lesions, paralleling higher expression of C/EBPβ or δ in more well-differentiated keratinocytes (Figure 2). High expression of S100A7 and AMPs creates a skin barrier highly resistant to skin infections, unlike atopic dermatitis which is commonly associated with bacterial and viral infections.

Another primary function of IL-17 in psoriasis is the recruitment of leukocyte subsets into inflamed psoriatic plaques. IL-17 induces keratinocytes to synthesize and release CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, and CXCL8 (i.e. IL-8), which leads to the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages. Infiltrating neutrophils form collections in the upper layers of the epidermis and stratum corneum called Munro’s microabscesses. IL-17A, IL-22, and TNF also stimulate the expression of CCL20 in keratinocytes, which in turn attract CCR6+ cells (e.g. including mDCs and T17 cells) and sustain the inflammatory response via a positive chemotactic feedback loop.55 The IFN-like cytokines (IL-26 and IL-29) secreted by T17 cells also activate STAT1 in keratinocytes leading to the expression of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 which attract Th1 cells into psoriatic skin and sensitize keratinocytes to its own action.56, 57 Psoriatic keratinocytes also synthesize other growth factors which affect connective tissue cells in the dermis; platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), angiopoietin-2, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) likely drive angiogenesis, which accounts for the erythematous skin lesions.58

TNF ANTAGONISTS

TNF is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine that is made by a variety of immune cells found in the skin, including T-cells, keratinocytes, DCs, and macrophages. Its upregulation in the skin of psoriasis patients has been well characterized.59, 60 The clinical efficacy of multiple TNF antagonists (e.g. adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) underscore the importance of this cytokine in the promotion and maintenance of psoriatic skin lesions, though the percentage of patients experiencing dramatic improvement in their skin lesions is significantly lower than those seen with novel IL-17 and IL-23 antagonists.

The efficacy of TNF antagonists in psoriasis is likely related to their indirect effects on IL-23/T17 signaling. One of the primary effects of TNF in psoriasis is its regulation of IL-23. In response to some triggering event in the skin (e.g. trauma or infection), TNF released by pDCs results in the increased production of IL-23 from mDCs. mDCs that produce TNF and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), also known as TIP-DCs, are increased in psoriasis plaques and are the major source of IL-23 in psoriatic skin.30, 61 The increased production of IL-23 by mDCs is the primary signal driving the activation of T17 cells in psoriasis plaques as well as and the broad immune activation observed in proliferating keratinocytes (Figure 1). In addition to its upstream induction of IL-23, TNF also acts synergistically with IL-17 to increase and sustain the upregulation of many psoriasis-related pro-inflammatory genes made by epidermal keratinocytes. In this way, the clinical efficacy of TNF antagonists may be due in large part to their indirect inhibition of the IL-23/T17 signaling pathway in the skin.

RECENTLY APPROVED AND NOVEL THERAPEUTIC AGENTS FOR PSORIASIS

The discovery of the T17 cell population and elucidation of the broad effects of the IL-23/T17 signaling axis on keratinocytes and infiltrating immune cells in the skin has largely shaped the current disease model of psoriasis. Psoriatic disease is, therefore, best understood as a patterned response to chronic activation of the IL-23/T17 pathway. For this reason, current therapeutic strategies are now focused on the development of novel agents that disrupt the IL-23 or IL-17 cytokine signaling. In the subsequent sections of this review, we will discuss the testing and development of several approved IL-17 antagonists, as well as several IL-23 inhibitors currently in development and clinical testing.

IL-17 Inhibition

To date, three IL-17 pathway antagonists have been approved for the treatment of psoriatic disease: secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab. Phase III clinical trials have demonstrated the high efficacy, tolerability, and safety of these inhibitors. The commercialization of the IL-17 antagonists has transformed the way patients with psoriatic disease are being treated in the clinic.

Secukinumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against IL-17A, was the first inhibitor of its kind approved for the treatment of psoriatic disease. Secukinumab was approved in January 2016 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Phase III clinical trials (i.e. ERASURE/FIXTURE62 and CLEAR63, 64 trials) have demonstrated that more than 75% of plaque psoriasis patients treated with secukinumab achieved a 75% improvement in their Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75), with a significant portion also achieving PASI90 and PASI100. In the CLEAR trial,64 nearly 80% of treated patients achieved a PASI90 at week 16 compared to only 58% in a comparison cohort treated with ustekinumab (a selective antagonist of the p40 subunit shared by IL-12 and IL-23). In clinical trials evaluating psoriatic arthritis patients treated with secukinumab (FUTURE-1 and -2),65, 66 just over half of all patients achieved an 20% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology criteria (ACR20) for tender or swollen joints.

Similar to secukinumab, ixekizumab is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody directed against IL-17A. In March 2016, ixekizumab was approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Three double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III studies using ixekizumab for plaque psoriasis (UNCOVER-1, -2, and -3)67, 68 underscored the high efficacy associated with IL-17 blockade in psoriatic disease. Around 80–90% of patients in the UNCOVER trials achieved a PASI75 compared to fewer than 10% and 40–50% in placebo and etanercept arms, respectively. The percentage of psoriatic arthritis patients achieving an ACR20 following treatment with ixekizumab (SPIRIT-P1) is comparable to those from the FUTURE trials for secukinumab;69 the SPIRIT-P2 trial is ongoing and results have not yet been released (ClinicalTrials.gov Registration Number: NCT02349295). The future approval of ixekizumab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis is probable based on the favorable results of the SPIRIT-P1 study.

Brodalumab, a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-17 receptor, was approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in February 2017. Three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III studies evaluating the efficacy of brodalumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: AMAGINE-1, -2, and -3.70, 71 More than 80% of psoriasis patients treated with brodalumab achieved a PASI75 at the primary endpoints of the AMAGINE trials, and brodalumab was shown to be superior to both placebo and ustekinumab. Two clinical trials for the evaluation of brodalumab in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis (AMVISION-1 and -2) have been performed, but study results are not available publicly (ClinicalTrials.gov Registration Numbers: NCT02029495 and NCT02024646).

The available safety information for secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab is reassuring. Common adverse side effects noted in clinical trials include upper respiratory infections, headache, nasopharyngitis, mild neutropenia, Candida albicans mucocutaneous infections, and diarrhea. The association of IL-17 blockade with Candida infections likely reflects the normal role for this cytokine in the innate immune response against this organism; therefore, its absence renders the skin susceptible to overgrowth in the skin and mucosal tissues as observed in patients with inborn errors in IL-17.72 Less common side effects reported were arthralgias, fatigue, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and injection site reactions. The potential association with IL-17 inhibition and gastrointestinal disorders is of interest given that secukinumab and brodalumab testing for the treatment of IBD caused worsening of symptoms in some patients. Lastly, four suicides were reported in the AMAGINE trials for brodalumab raising some concerns regarding the safety of this agent though no causal relationship was ever demonstrated. Nevertheless, the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy was instituted to provide required surveillance for suicide and suicidal ideation in patients treated with brodalumab.

IL-23 Inhibition

As a “master regulator” of T17 cell development, IL-23 inhibition is currently in process using antibodies that target its unique p19 subunit (e.g. tildrakizumab, guselkumab, and risankizumab). Early clinical trials have demonstrated that sufficient inhibition of IL-23p19 results in a rapid resolution of the clinical and histologic features associated with psoriasis similar or even better to that seen with IL-17 blockade.73 In two early clinical studies, relatively long-term treatment responses were observed in some patients with just a single doses of IL-23p19 inhibition;73, 74 this dramatic clinical response may be explained, in part, by promoting trans-differentiation of Th17 cells into regulatory T-cell or Th1 populations.75, 76 Phase III clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of tildrakizumab, guselkumab, and risankizumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are ongoing.

Two Phase III clinical trials (VOYAGE 1 and 2) for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis with guselkumab were recently published.77, 78 Both VOYAGE trials were 48-week studies that compared guselkumab to placebo and adalimumab, though the VOYAGE 2 trial also evaluated the clinical response in psoriasis patients with interrupted treatment (randomized withdrawal and retreatment). Results from the VOYAGE 1 and 2 trials were highly similar and reported a PASI90 response in 73% and 70% of patients, respectively, at week 16 compared to approximately 50% of patients treated with adalimumab. More than one-third of patients treated with guselkumab achieved a PASI100 by week 16 compared to only about 15% of patients treated with adalimumab. Importantly, a separate Phase III study (NAVIGATE trial) performed a head-to-head comparison of guselkumab and ustekinumab, which targets the p40 subunit of both IL-12 and IL-23. In this trial, 51% and 20% of patients treated with guselkumab achieved a PASI90 and PASI100, respectively, whereas only 24% and 8% of patients in the ustekinumab treatment arm achieved a PASI90 and PASI100, respectively.79 A recent Phase II clinical trial further demonstrated the clinical superiority of selective p19 inhibition with risankizumab compared to inhibition of the shared p40 subunit by ustekinumab.80

The most common adverse events reported in Phase III trials with guselkumab were non-serious infections (e.g. upper respiratory infections), nasopharyngitis, headache, arthrlagias, and mild injection site reactions. Rare adverse events included skin or soft tissues abscesses and non-melanoma skin cancers. While the presence of anti-guselkumab antibodies were detected in ~5% of treated patients, no correlation was observed between antibody titer levels and loss of drug efficacy. Additional studies are necessary to better define the long-term efficacy and safety profiles of this class of biologics for the treatment of plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The success of the IL-17 and IL-23 antagonists for the treatment of psoriatic disease has resulted in a modification of the primary clinical outcome being used in clinical trials. The treatment target has been moving to increased clearing of disease such that PASI90 and PASI100 are now considered better targets than PASI75. Still, the mere existence of psoriasis patients who fail to improve with IL-17 or IL-23 blockade highlights the complexity of this chronic inflammatory skin condition. Differences in the expression of specific IL-17 isoforms in various tissues81, 82 and/or the synergistic effects of IL-17 with TNF46 may account for the lack of response in patients with recalcitrant disease. Therefore, inhibition of more than one cytokine may be required to achieve disease resolution in essentially all patients. For example, with synergy of TNF and IL-17 for many inflammatory genes, dual inhibition of these cytokines (e.g. a bi-specific antibody) has been suggested; other bi-specific antibodies target IL-17A and IL-17F combined.83 The compounding of adverse effects and/or the high cost associated with this combination treatment strategy may, however, limit its implementation in traditional clinical settings.

Many patients prefer oral medications over biologics that must be given by injection. Currently approved drugs like methotrexate, cyclosporine, and apremilast are used to treat psoriasis, but these drugs either have overall efficacies that are much lower than biologics (e.g. apremilast induces PASI75 responses in about one-third of moderate-to-severe patients)84 or there is poor tolerability or risk of organ dysfunction with for long-term use. Newer small molecule drugs currently in development are now based on targeting molecules that are more directly related to the IL-23/Type 17 T-cell axis and thus these drugs may be able to improve upon efficacy and safety limitations of existing small molecule drugs. The development and testing of small molecule inhibitors, such as janus kinase (JAK) enzyme and retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γt (RORγt) inhibitors, offer another treatment modality with several advantages over traditional biologic medications. First, small molecules can be administered orally and can be potent inhibitors of specific immune population, such as the T17 subset.85 Second, they are synthetically manufactured and are relatively inexpensive compared to traditional biologic agents. Lastly, these synthetic small molecules access intracellular targets and lack the immunogenic properties associated with fully human or humanized antibodies. Their inhibition of intracellular enzymes, however, also account for their primary disadvantage (i.e. the difficulty in predicting their biological effects and/or their unintended or off-target effects). Several small molecules inhibitors are currently undergoing clinical testing for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis, and it will be interesting to see how these agents compare in head-to-head trials against newer, highly-effective monoclonal antibodies.

In conclusion, our understanding of the immunologic, genetic, and autoimmune characteristics of psoriasis has improved substantially in the last decade. Insights into the importance of the IL-23/T17 signaling pathway have directly led to the development of some of the most effective treatments of psoriasis to date. The translational revolution we are witnessing raises the possibility of novel therapeutic strategies. Emerging bispecific antibodies offer the potential for improved disease control, while small molecule drugs may offer future alternatives to the use of biologics and less costly long-term disease management.

KEY CONCEPTS.

The etiology of psoriasis is due to a complex interplay between the immune system, psoriasis-associated susceptibility loci, psoriasis autoantigens, and multiple environmental factors.

The IL-23/T17 axis represents the central immune pathway driving the development of psoriasis via the downstream effects of increased IL-17.

In response to IL-23, pathogenic T17 cells produce high levels of IL-17 which has broad inflammatory effects on keratinocytes and a variety of immune cells found in the skin.

Increased levels of IL-17 produces a “feed forward” inflammatory response in keratinocytes that is self-amplifying and drives the development of mature psoriatic plaques by inducing epidermal hyperplasia, epidermal cell proliferation, and the recruitment of leukocyte subsets into the skin.

The high efficacy and good safety profile of novel monoclonal antibodies against IL-17 and IL-23 underscore the central role of these cytokines as predominant drivers of psoriasis.

Emerging bispecific antibodies offer the potential for improved disease control, while small molecule drugs may offer future alternatives to the use of biologics and less costly long-term disease management.

Acknowledgments

JEH is supported in part by the Rockefeller University CTSA award grant # KL2TR001865 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program. JEH and JGK are supported in part by grant # UL1TR001866 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AMP

Antimicrobial peptide

- CLA

cutaneous lymphocyte antigen

- C/EBPδ

CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPβ), and delta

- ADAMTSL5

a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- hBD2

human β-defensin 2

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- ILCs

innate lymphoid cells

- IL

interleukin

- JAK

janus kinase

- LCN2

lipocalin-2

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa B

- mDC

myeloid dendritic cells

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PLA2G4D

phospholipase A2 group IVD

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- Trm

resident memory T-cell

- RORγt

retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γt

- STAT1

signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- TLRs

toll-like receptors

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- T17

type 17 T-cell

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Glossary

| Glossary Word | Definition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Surface Area (BSA) | Typically expressed in m2, the formulas by Mosteller

|

||

| CD11a | A cell adhesion protein that forms part of LFA-1, the defective protein in leukocyte adhesion deficiency type I. |

||

| CTLA-4 | An Ig-family transmembrane protein expressed on peripheral T cells following activation. CTLA-4 contains immune tyrosine inhibitory motifs (ITIMs). CTLA-4 inhibits T cells by competing for ligands with CD28 and by associating with SHP-2 and PP2A to affect proximal TCR signaling. CTLA-4 deficiency, an autosomal dominant primary immunodeficiency, results in impaired function of Treg cells, leading to autoimmune cytopenias, enteropathy, interstitial lung disease, recurrent infections, and extra-lymphoid lymphocytic infiltration. |

||

| Cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA) | A homing molecule on T cells that binds to E-selectin on endothelial cells. Its expression is induced by dendritic cells binding to naive T cells in skin draining lymph nodes. |

||

| Dactylitis | Inflammation of an entire digit. When accompanied by soft tissue swelling, the term “sausage digit” is often applied. |

||

| Enthesitis | Inflammation of the enthesis, the site of attachment of a tendon, ligament, or joint capsule onto bone or cartilage. |

||

| Janus kinase (JAK) | A tyrosine kinase family that phosphorylates several cytokine receptors and STATs which allows STAT binding and subsequent STAT activation. JAK3 deficiency causes T-B+ SCID. The four JAK family members are: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2. |

||

| Plasmacytoid dendritic cell | A type of dendritic cell with a distinct histologic morphology that can produce high levels of type I interferon. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are thought to play special roles in antiviral host defense and autoimmunity. |

||

| Retinoic acid receptorrelated orphan receptor γt (RORγt) | A characteristic transcription factor for Th17 development. Its production is induced by TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-1. RORγt is encoded by RORC, but represents a truncated version of the RORγ protein. RORC mutations are associated with susceptibility to mycobacterial disease and candidiasis. |

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

JEH serves as an investigator for Pfizer Inc. JGK has been a consultant to and has received research support from companies that have developed or are developing therapeutics for psoriasis: AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, Idera, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Serono, Sun, Valeant, and Vitae.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gladman DD. Clinical Features and Diagnostic Considerations in Psoriatic Arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:569–79. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic Burden of Psoriasis in the United States: A Systematic Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651–8. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, Mehta NN, Ogdie A, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: Epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, Kurd SK, Shin DB, Wang X, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1493–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.12.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, Mehta NN, Ogdie A, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: Implications for management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bos JD, Hagenaars C, Das PK, Krieg SR, Voorn WJ, Kapsenberg ML. Predominance of “memory” T cells (CD4+, CDw29+) over “naive” T cells (CD4+, CD45R+) in both normal and diseased human skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 1989;281:24–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00424268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bos JD, Hulsebosch HJ, Krieg SR, Bakker PM, Cormane RH. Immunocompetent cells in psoriasis. In situ immunophenotyping by monoclonal antibodies. Arch Dermatol Res. 1983;275:181–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00510050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eedy DJ, Burrows D, Bridges JM, Jones FG. Clearance of severe psoriasis after allogenic bone marrow transplantation. BMJ. 1990;300:908. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6729.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis CN, Gorsulowsky DC, Hamilton TA, Billings JK, Brown MD, Headington JT, et al. Cyclosporine improves psoriasis in a double-blind study. JAMA. 1986;256:3110–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffiths CE, Powles AV, Leonard JN, Fry L, Baker BS, Valdimarsson H. Clearance of psoriasis with low dose cyclosporin. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:731–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6549.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan TJ, Baker H. Systemic corticosteroids and folic acid antagonists in the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis. Evaluation and prognosis based on the study of 104 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:134–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1969.tb15995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang JC, Smith LR, Froning KJ, Schwabe BJ, Laxer JA, Caralli LL, et al. CD8+ T cells in psoriatic lesions preferentially use T-cell receptor V beta 3 and/or V beta 13. 1 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9282–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottlieb SL, Gilleaudeau P, Johnson R, Estes L, Woodworth TG, Gottlieb AB, et al. Response of psoriasis to a lymphocyte-selective toxin (DAB389IL-2) suggests a primary immune, but not keratinocyte, pathogenic basis. Nat Med. 1995;1:442–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0595-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrams JR, Lebwohl MG, Guzzo CA, Jegasothy BV, Goldfarb MT, Goffe BS, et al. CTLA4Ig-mediated blockade of T-cell costimulation in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1243–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krueger GG, Callis KP. Development and use of alefacept to treat psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S87–97. doi: 10.1016/mjd.2003.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebwohl M, Tyring SK, Hamilton TK, Toth D, Glazer S, Tawfik NH, et al. A novel targeted T-cell modulator, efalizumab, for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2004–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farber EM, Nall ML, Watson W. Natural history of psoriasis in 61 twin pairs. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandrup F, Holm N, Grunnet N, Henningsen K, Hansen HE. Psoriasis in monozygotic twins: variations in expression in individuals with identical genetic constitution. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:229–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiilikainen A, Lassus A, Karvonen J, Vartiainen P, Julin M. Psoriasis and HLA-Cw6. Br J Dermatol. 1980;102:179–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1980.tb05690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsoi LC, Stuart PE, Tian C, Gudjonsson JE, Das S, Zawistowski M, et al. Large scale meta-analysis characterizes genetic architecture for common psoriasis associated variants. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15382. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harden JL, Hamm D, Gulati N, Lowes MA, Krueger JG. Deep Sequencing of the T-cell Receptor Repertoire Demonstrates Polyclonal T-cell Infiltrates in Psoriasis. F1000Res. 2015;4:460. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.6756.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawkes JE, Gonzalez JA, Krueger JG. Autoimmunity in Psoriasis: Evidence for Specific Autoantigens. Current Dermatology Reports. 2017;6:104–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lande R, Botti E, Jandus C, Dojcinovic D, Fanelli G, Conrad C, et al. The antimicrobial peptide LL37 is a T-cell autoantigen in psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5621. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanetti M. The role of cathelicidins in the innate host defenses of mammals. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2005;7:179–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–95. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, Chatterjee B, Wang YH, Homey B, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature. 2007;449:564–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowes MA, Suarez-Farinas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:227–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganguly D, Chamilos G, Lande R, Gregorio J, Meller S, Facchinetti V, et al. Self-RNA-antimicrobial peptide complexes activate human dendritic cells through TLR7 and TLR8. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1983–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nestle FO, Conrad C, Tun-Kyi A, Homey B, Gombert M, Boyman O, et al. Plasmacytoid predendritic cells initiate psoriasis through interferon-alpha production. J Exp Med. 2005;202:135–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lande R, Chamilos G, Ganguly D, Demaria O, Frasca L, Durr S, et al. Cationic antimicrobial peptides in psoriatic skin cooperate to break innate tolerance to self-DNA. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:203–13. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arakawa A, Siewert K, Stohr J, Besgen P, Kim SM, Ruhl G, et al. Melanocyte antigen triggers autoimmunity in human psoriasis. J Exp Med. 2015;212:2203–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Apte SS. A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin-type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif (ADAMTS) superfamily: functions and mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31493–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.052340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bader HL, Wang LW, Ho JC, Tran T, Holden P, Fitzgerald J, et al. A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5 (ADAMTSL5) is a novel fibrillin-1-, fibrillin-2-, and heparin-binding member of the ADAMTS superfamily containing a netrin-like module. Matrix Biol. 2012;31:398–411. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonifacio KM, Kunjravia N, Krueger JG, Fuentes-Duculan J. Cutaneous Expression of A Disintegrin-like and Metalloprotease domain containing Thrombospondin Type 1 motif-like 5 (ADAMTSL5) in Psoriasis goes beyond Melanocytes. J Pigment Disord. 2016:3. doi: 10.4172/2376-0427.1000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fuentes-Duculan J, Bonifacio KM, Hawkes JE, Kunjravia N, Cueto I, Li X, et al. Autoantigens ADAMTSL5 and LL37 are significantly upregulated in active Psoriasis and localized with keratinocytes, dendritic cells and other leukocytes. Exp Dermatol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/exd.13378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheung KL, Jarrett R, Subramaniam S, Salimi M, Gutowska-Owsiak D, Chen YL, et al. Psoriatic T cells recognize neolipid antigens generated by mast cell phospholipase delivered by exosomes and presented by CD1a. J Exp Med. 2016;213:2399–412. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiba H, Michibata H, Wakimoto K, Seishima M, Kawasaki S, Okubo K, et al. Cloning of a gene for a novel epithelium-specific cytosolic phospholipase A2, cPLA2delta, induced in psoriatic skin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12890–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quaranta M, Knapp B, Garzorz N, Mattii M, Pullabhatla V, Pennino D, et al. Intraindividual genome expression analysis reveals a specific molecular signature of psoriasis and eczema. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:244ra90. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, Gran B, Zhang GX, Ventura ES, Siglienti I, Rostami A, et al. Differential expression and regulation of IL-23 and IL-12 subunits and receptors in adult mouse microglia. J Neurol Sci. 2003;215:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim J, Krueger JG. The immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Res PC, Piskin G, de Boer OJ, van der Loos CM, Teeling P, Bos JD, et al. Overrepresentation of IL-17A and IL-22 producing CD8 T cells in lesional skin suggests their involvement in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim J, Krueger JG. Highly Effective New Treatments for Psoriasis Target the IL-23/Type 17 T Cell Autoimmune Axis. Annu Rev Med. 2017;68:255–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042915-103905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiricozzi A, Guttman-Yassky E, Suarez-Farinas M, Nograles KE, Tian S, Cardinale I, et al. Integrative responses to IL-17 and TNF-alpha in human keratinocytes account for key inflammatory pathogenic circuits in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:677–87. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teunissen MB, Koomen CW, de Waal Malefyt R, Wierenga EA, Bos JD. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma synergize in the enhancement of proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:645–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Beelen AJ, Teunissen MB, Kapsenberg ML, de Jong EC. Interleukin-17 in inflammatory skin disorders. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:374–81. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282ef869e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang CQ, Akalu YT, Suarez-Farinas M, Gonzalez J, Mitsui H, Lowes MA, et al. IL-17 and TNF synergistically modulate cytokine expression while suppressing melanogenesis: potential relevance to psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2741–52. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, Tato CM, McGeachy MJ, Konkel JE, et al. Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2010;467:967–71. doi: 10.1038/nature09447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Pennino D, Carbone T, Nasorri F, Pallotta S, et al. Th22 cells represent a distinct human T cell subset involved in epidermal immunity and remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3573–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI40202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng Y, Danilenko DM, Valdez P, Kasman I, Eastham-Anderson J, Wu J, et al. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648–51. doi: 10.1038/nature05505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cho KA, Suh JW, Lee KH, Kang JL, Woo SY. IL-17 and IL-22 enhance skin inflammation by stimulating the secretion of IL-1beta by keratinocytes via the ROS-NLRP3-caspase-1 pathway. Int Immunol. 2012;24:147–58. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harper EG, Guo C, Rizzo H, Lillis JV, Kurtz SE, Skorcheva I, et al. Th17 cytokines stimulate CCL20 expression in keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo: implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2175–83. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stephen-Victor E, Fickenscher H, Bayry J. IL-26: An Emerging Proinflammatory Member of the IL-10 Cytokine Family with Multifaceted Actions in Antiviral, Antimicrobial, and Autoimmune Responses. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005624. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolk K, Witte K, Witte E, Raftery M, Kokolakis G, Philipp S, et al. IL-29 is produced by T(H)17 cells and mediates the cutaneous antiviral competence in psoriasis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:204ra129. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heidenreich R, Rocken M, Ghoreschi K. Angiogenesis drives psoriasis pathogenesis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90:232–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haider AS, Cohen J, Fei J, Zaba LC, Cardinale I, Toyoko K, et al. Insights into gene modulation by therapeutic TNF and IFNgamma antibodies: TNF regulates IFNgamma production by T cells and TNF-regulated genes linked to psoriasis transcriptome. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:655–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowes MA, Chamian F, Abello MV, Fuentes-Duculan J, Lin SL, Nussbaum R, et al. Increase in TNF-alpha and inducible nitric oxide synthase-expressing dendritic cells in psoriasis and reduction with efalizumab (anti-CD11a) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:19057–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509736102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zaba LC, Krueger JG, Lowes MA. Resident and “inflammatory” dendritic cells in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:302–8. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, Reich K, Griffiths CE, Papp K, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis--results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thaci D, Blauvelt A, Reich K, Tsai TF, Vanaclocha F, Kingo K, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: CLEAR, a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:400–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blauvelt A, Reich K, Tsai TF, Tyring S, Vanaclocha F, Kingo K, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis up to 1 year: Results from the CLEAR study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:60–9. e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Rahman P, van der Heijde D, et al. Secukinumab Inhibition of Interleukin-17A in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1329–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin CT, Rahman P, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1137–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Langley RG, Luger T, Ohtsuki M, et al. Phase 3 Trials of Ixekizumab in Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1512711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M, van de Kerkhof P, Paul C, Menter A, et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;386:541–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, Okada M, Cuchacovich RS, Shuler CL, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:79–87. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, Blauvelt A, Baran W, Bolduc C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273–86. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, Gordon K, Weglowska J, Puig L, et al. Phase 3 Studies Comparing Brodalumab with Ustekinumab in Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Puel A, Cypowyj S, Bustamante J, Wright JF, Liu L, Lim HK, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science. 2011;332:65–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1200439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sofen H, Smith S, Matheson RT, Leonardi CL, Calderon C, Brodmerkel C, et al. Guselkumab (an IL-23-specific mAb) demonstrates clinical and molecular response in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1032–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, Wagner F, White A, Visvanathan S, et al. Anti-IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: Safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:116–24. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gagliani N, Amezcua Vesely MC, Iseppon A, Brockmann L, Xu H, Palm NW, et al. Th17 cells transdifferentiate into regulatory T cells during resolution of inflammation. Nature. 2015;523:221–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jager A, Kuchroo VK. Effector and regulatory T-cell subsets in autoimmunity and tissue inflammation. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:173–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Randazzo B, Wasfi Y, Shen YK, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: Results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:405–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, Song M, Wasfi Y, Randazzo B, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: Results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:418–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Langley RG, Tsai TF, Flavin S, Song M, Randazzo B, Wasfi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: Results of the randomized, double-blind, Phase 3 NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/bjd.15750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M, Gooderham M, Krueger JG, Lacour JP, et al. Risankizumab versus Ustekinumab for Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1551–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johansen C, Usher PA, Kjellerup RB, Lundsgaard D, Iversen L, Kragballe K. Characterization of the interleukin-17 isoforms and receptors in lesional psoriatic skin. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:319–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Baarsen LG, Lebre MC, van der Coelen D, Aarrass S, Tang MW, Ramwadhdoebe TH, et al. Heterogeneous expression pattern of interleukin 17A (IL-17A), IL-17F and their receptors in synovium of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and osteoarthritis: possible explanation for nonresponse to anti-IL-17 therapy? Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:426. doi: 10.1186/s13075-014-0426-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Torres T, Romanelli M, Chiricozzi A. A revolutionary therapeutic approach for psoriasis: bispecific biological agents. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25:751–4. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2016.1187130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paul C, Cather J, Gooderham M, Poulin Y, Mrowietz U, Ferrandiz C, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis over 52 weeks: a phase III, randomized controlled trial (ESTEEM 2) Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1387–99. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.de Wit J, Al-Mossawi MH, Huhn MH, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Doig K, Kendrick B, et al. RORgammat inhibitors suppress T(H)17 responses in inflammatory arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:960–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]