Abstract

During embryonic development of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), Schwann cell precursors migrate along neuronal axons to their final destinations, where they will myelinate the axons after birth. While the intercellular signals controlling Schwann cell precursor migration are well studied, the intracellular signals controlling Schwann cell precursor migration remain elusive. Here, using a rat primary cell culture system, we show that Dock8, an atypical Dock180-related guanine-nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for small GTPases of the Rho family, specifically interacts with Nck1, an adaptor protein composed only of Src homology (SH) domains, to promote Schwann cell precursor migration induced by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). Knockdown of Dock8 or Nck1 with its respective siRNA markedly decreases PDGF-induced cell migration, as well as Rho GTPase activation, in precursors. Dock8, through its unique N-terminal proline-rich motif, interacts with the SH3 domain of Nck1, but not with other adaptor proteins composed only of SH domains, e.g. Grb2 and CrkII, and not with the adaptor protein Elmo1. Reintroduction of the proline-rich motif mutant of Dock8 in Dock8 siRNA-transfected Schwann cell precursors fails to restore their migratory abilities, whereas that of wild-type Dock8 does restore these abilities. These results suggest that Nck1 interaction with Dock8 mediates PDGF-induced Schwann cell precursor migration, demonstrating not only that Nck1 and Dock8 are previously unanticipated intracellular signaling molecules involved in the regulation of Schwann cell precursor migration but also that Dock8 is among the genetically-conservative common interaction subset of Dock family proteins consisting only of SH domain adaptor proteins.

Keywords: Dock8, Nck1, PDGF, Schwann cell precursor, Migration

Highlights

-

•

Dock8, a Rho family GEF, regulates Schwann cell precursor migration.

-

•

Nck1 adaptor protein regulates Schwann cell precursor migration.

-

•

Dock8 uniquely interacts with Nck1.

-

•

The interaction of Dock8 with Nck1 contributes to migration.

1. Introduction

In the embryonic development of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), Schwann cell precursors migrate along neuronal axons to their final destinations [1], [2]. After birth, they eventually wrap around individual axons to form myelin sheaths. Myelin sheaths are derived from the Schwann cells’ morphologically differentiated plasma membranes and grow to be more than one hundred times larger than the collective surface area of the premyelination Schwann cell plasma membranes [1], [2]. Previous studies have thoroughly explored the intercellular signaling controlling Schwann cell morphological changes in cell migration and axon wrapping. For example, growth factors such as neuregulin-1 (NRG1), neurotrophin-3 (NT3), and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and adhesion molecules such as integrin ligands are provided by peripheral neurons and bind to their cognate receptors expressed on Schwann cells [3], [4], [5], [6]. Their integrated extracellular signals are involved in regulating Schwann cell morphological changes [3], [4], [5], [6]. In contrast, the intracellular signaling controlling these processes is not yet sufficiently understood.

Rho family small GTPases (such as RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42) are central players in controlling cell morphological changes by rearranging cytoskeletal proteins [7], [8]. Similar to Ras GTPases, Rho GTPases act as intracellular molecular switches. Rho GTPases are biologically active when bound to GTP, which enables them to associate with effector molecules; in contrast, they are inactive when bound to GDP, which eliminates or diminishes their ability to bind with effectors [7], [8]. The former reaction is a rate-limiting step [7], [8] and is mediated by guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), which serve as Rho GTPase activators, whereas the latter reaction is mediated by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which serve as Rho GTPase inactivators.

The Rho family GEFs consist of more than 70 members, including the Dbl-family proteins (of various molecular weights) and the Dock180-related proteins (each ~180 kDa) [7], [8], [9], [10]. The Dock180-related proteins are 11 proteins [Dock180 (now designated as Dock1)-Dock11] that are specific for Rac1 and/or Cdc42 [11], [12], [13], [14]. They are subdivided, based on their amino acid sequence homology and their specificity for particular Rho GTPases, into three/four groups: Dock-A/B (Dock1-5), Dock-C (Dock6-8), and Dock-D (Dock9-11) [14]. They are organized by two major common domains of Dock homology regions 1 and 2 (DHR1/2, also known as CZH1/2 or Docker1/2). DHR2 is a catalytic domain whereas DHR1 is thought to bind lipids to assist in recruitment to the plasma membranes [14].

The Dock-A/B members (Dock1-5) have been well characterized. In addition to DHR1/2, their members contain the single Src homology 3 (SH3) domain and the single proline-rich region. These domains are genetically conserved from organisms such as Caenorhabditis elegans to mammals [10] and are involved in the Dock-A/B members’ interactions with the Src homology (SH) domain adaptor proteins CrkII, Grb2, and Nck1 and with other adaptor proteins such as Elmo1 [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Dock1's SH3 domain and proline-rich region engage in domain-domain interactions with CrkII and Elmo1 and are needed not only for migration in fibroblasts and epithelial cells but also for phagocytotic signaling of the “eat-me” signal in the immune system [12], [13], [14]. Other regions of the Dock180-related proteins vary among members in ways that remain to be clarified [12], [13], [14].

Our previous study described how NRG1 binds Schwann cell ErbB3/2 heterodimeric receptors and promotes cell migration specifically through Dock7 [15], [16]. Yet Schwann cells express Dock8, which may or may not be involved in migration induced by growth factor(s) [15]. Here, we show that Dock8 specifically mediates platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-induced Schwann cell precursor migration. The molecule that transmits signals between Dock8 and the PDGF receptor is the adaptor protein Nck1, whose SH3 domain interacts with the proline-rich region of Dock8. These results show that the genetically-conserved protein-protein interaction observed in Dock-A/B members is also used by Dock8.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: polyclonal anti-Dock8 from Takara Bio (Kyoto, Japan); monoclonal anti-Nck1, monoclonal anti-Rac1, and monoclonal anti-Cdc42 from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA); monoclonal RhoA and monoclonal anti-GST tag from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); polyclonal anti-PDGF receptor alpha from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA); polyclonal anti-p75NTR from Promega (Fitchburg, WI, USA); and monoclonal FLAG-tag, monoclonal HA-tag, and monoclonal anti-actin from MBL (Nagoya, Japan). Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from GE Healthcare (Fairfield, CT, USA) or Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). Fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK) or Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

2.2. siRNAs

The target sequences (#1 and #2) for Dock8 were 5′-GAATGTAGGACTTTGCAGC-3′ and 5′-GTTACATCCTGAAACGTCG-3′, respectively. Since siRNA#1 is more effective at knocking down proteins compared to siRNA#2, siRNA#1 was used as Dock8 siRNA except in the first experiment. The target sequence for Nck1 was 5′-GAATGAGCGATTATGGCTC-3′. The target sequence of Photinus pyralis luciferase, as the control, was 5′-AAGCCATTCTATCCTCTAGAG-3′.

2.3. Plasmid constructs

The cDNAs encoding Nck1 (GenBank Acc. No. NM_001291999), Grb2 (GenBank Acc. No. NM_002086), and CrkII (GenBank Acc. No. NM_016823) were amplified from human brain cDNAs (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). These constructs were inserted into the mammalian expression vector pCMV-GST, resulting in the expression of GST-tagged proteins at the N-terminus. Regarding Nck1, two types of constructs carrying functionally-deficient point mutations, one with the mutation in the SH2 domain or the other with the mutation in the SH3 domain (R308K or W38A/W143A/W229A) [17], [18], respectively, were produced using an inverse PCR-based mutagenesis kit (Toyobo Life Science, Osaka, Japan). The mammalian expression plasmids encoding FLAG-tagged Dock8 and HA-tagged Elmo1 (human origins) were constructed as previously described [19]. Mutations into alanine on Dock8's unique proline-rich sequence (P187VPECP192 to AVAECA) were also produced by triple cycles of inverse PCR-based mutagenesis, resulting in the loss of potential SH3 domain ligand activity. The Escherichia coli expression plasmids encoding active Rac1·GTP and Cdc42·GTP-binding domain (CRIB) of Pak1 and active RhoA·GTP-binding domain (RBD) of mDia1 were constructed as previously described [19].

2.4. Schwann cell precursor culture and transfection

Primary Schwann cell precursors or neurons were prepared from dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) of male or female Sprague-Dawley rats (Sankyo Laboratories) on embryonic day 14 and cultured in culture medium at 37 °C, as previously described [19], [20], [21], [22]. The siRNAs and/or plasmids were transfected into primary Schwann cell precursors using Nucleofector II device (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) with Basic Neuron Nucleofector kit (Lonza; a Nucleofector II program A33 protocol). Culture medium was replaced 24 h posttransfection. To confirm cell viability under these experimental conditions, cells were stained with 0.4% trypan blue. Stained attached cells routinely accounted for less than 5% of all cells 48 h posttransfection.

2.5. Schwann cell precursor migration and immunofluorescence

To enable us to mimic Schwann cell precursor migration from ganglia, Schwann cell precursor migration was measured using reaggregated precursors essentially as previously described [22]. Reaggregates were formed by plating Schwann precursor cells on Corning Ultra Low Attachment dishes (Corning, NY, USA) for 4 h and on Petri dishes for 20 h with gentle agitation every 4–6 h. Individual Schwann cells were allowed to migrate out of the reaggregates in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml of PDGFalpha (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), NRG1 (Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN, USA), NT3 (Peprotech), or IGF1 (Life Technologies) on type I collagen-coated dishes. After incubation at 37 °C for 6 h, cells were fixed with 4% PFA solution (Nacalai Tesque), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 solution (Nacalai Tesque), and blocked with Blocking One reagent (Nacalai Tesque). Blocked samples were immunostained with an anti-p75NTR antibody and then with a fluorescence-labeled secondary antibody, and were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The fluorescence images were captured with a DMI4000B fluorescence microscope system (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and analyzed with AF6000 software (Leica). 0.4% Trypan blue-stained attached cells routinely accounted for less than 5% of all cells after incubation for 6 h with each growth factor.

2.6. Cell line culture and transfection

For an interaction assay [19], [20], human embryonic kidney 293T cells (Human Science Research Resources Bank, Tokyo, Japan) were used [19], [20] and transfected using CalPhos transfection reagent (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Immunoprecipitation, affinity-precipitation, and immunoblotting

Cells or tissues were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.5], 3 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethane sulfonylfluoride, 0.01 mM leupeptin, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 0.5% NP-40, and 1% CHAPS), to elute cell and tissue proteins, then centrifuged in a microcentrifuge to obtain clear supernatants [19], [20]. Aliquots of the lysates were used for immunoprecipitation or affinity-precipitation. For immunoprecipitation, the lysates were mixed with an ImmunoCruz resin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) preabsorbed with the respective antibodies, and gently shaken for 2 h or overnight, and washed with lysis buffer. For affinity-precipitation, the same tagged protein-absorbed resin was used following immunoprecipitation. The precipitates or lysates were denatured and placed in SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The electrophoretically separated proteins were transferred to PDVF membrane using Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad), blocked with Blocking One reagent, and immunoblotted first with primary antibodies and then with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The bound antibodies were detected using chemiluminescence detection reagent (Nacalai Tesque). The scanned bands were densitometrically analyzed to identify their quantification using UN-SCAN-IT Gel software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT, USA).

2.8. Affinity-precipitation to detect active Rho GTPases

To detect any active GTP-bound forms of Rho GTPases in the lysates (0.1 mg of the average) of Schwann cell precursors treated with 20 ng/ml of PDGFalpha for 0.5 h, affinity-precipitation was performed using recombinant E. coli-produced GST-tagged CRIB (specific for Rac1·GTP and Cdc42·GTP) or RBD (specific for RhoA·GTP) proteins (0.02 mg of glutathion resin-immobilized recombinant protein per tube) [7], [8], [19]. The affinity-precipitated GTP-bound Rho GTPases were detected using immunoblotting with each anti-Rho GTPase antibody. The amounts of total Rho GTPase proteins in the cell lysates were also compared using immunoblotting. The scanned bands were densitometrically analyzed as a means of quantification.

2.9. Statistical analysis

The values shown in the figure panels represent the means ± standard deviation from separate experiments. Comparisons between two experimental groups were made using the unpaired Student's t-test (**, p<0.01,*, p<0.05). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was followed by a Fisher's protected least significant difference (PLSD) test (**, p<0.01). Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA), GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA, USA), or AnalystSoft StatPlus (Walnut, CA, USA) was used for these statistical analyses.

2.10. Animal studies

Experimental animals were cared for in accordance with the protocol approved by the Japanese National Research Institute for Child Health and Development Animal Care Committee. The gene recombination experiments were carried out in accordance with the protocol approved by the Japanese National Research Institute for Child Health and Development Gene Recombination Committee.

3. Results

3.1. Dock8 is involved in PDGF-mediated Schwann cell precursor migration

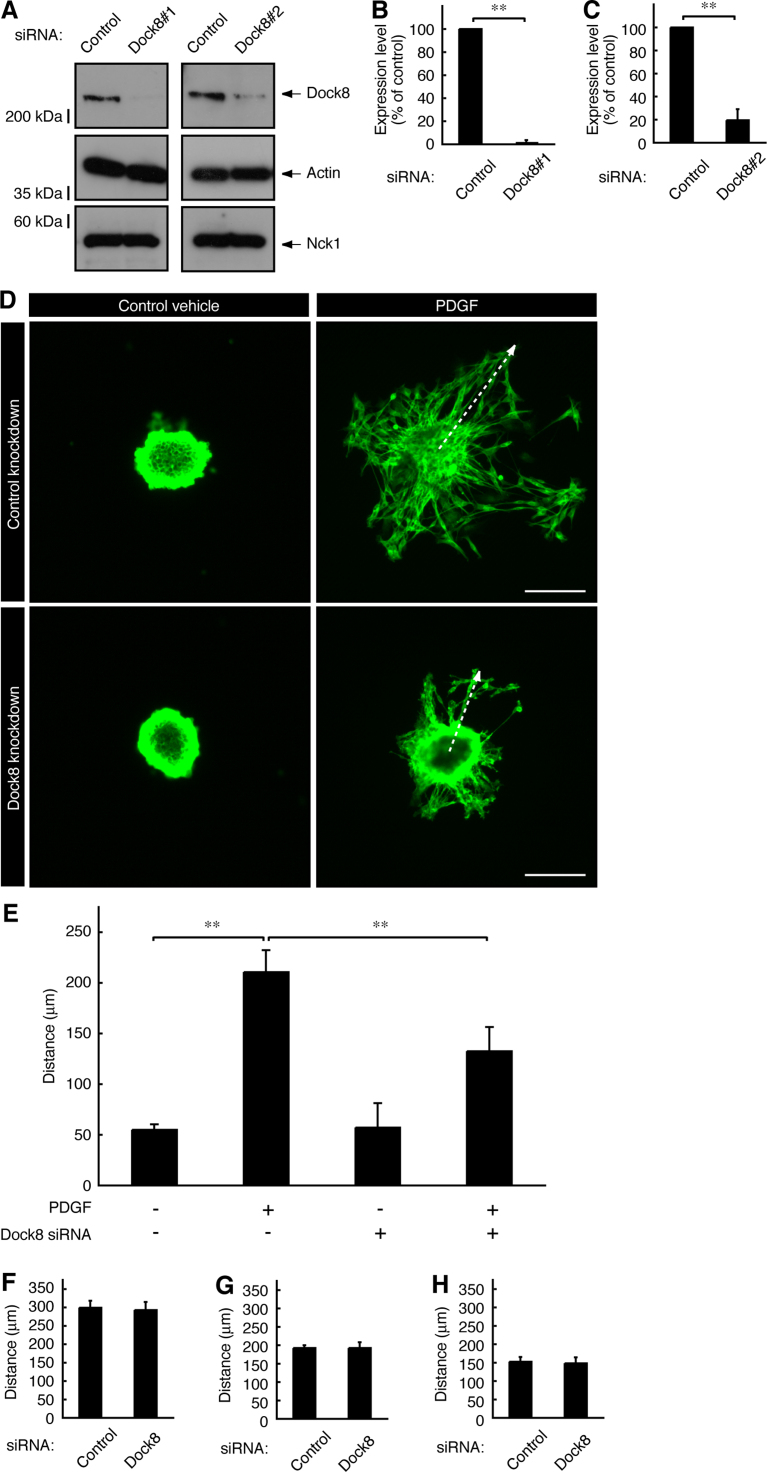

To investigate whether Dock8 is involved in rat Schwann cell precursor migration, we transfected siRNAs (nonoverlapping Dock8#1 and Dock8#2 siRNAs) specific for Dock8 into Schwann cell precursors. Transfection with siRNAs #1 and #2 knocked down expression of Dock8 proteins by approximately 95% and 80%, respectively (Fig. 1A–C). Since Dock8 siRNA#1 was more effective than siRNA#2, we used siRNA#1 in the following knockdown experiments. Transfection with Dock8 siRNA specifically inhibited PDGF-induced migration from Schwann cell precursor reaggregates by approximately 50% (Fig. 1D and E); in contrast, Dock8 knockdown did not affect migration induced by NRG1, NT3, or IGF1 (Fig. 1F–H). These growth factors are known to be involved in migratory activity for Schwann cell lineage cells [2], [13]. Reaggregates seem likely to mimic migration of Schwann cell precursors from the ganglia in mammalian embryonic development [21], [22].

Fig. 1.

Dock8 is involved in the regulation of PDGF-induced Schwann cell precursor migration. (A–C) Primary rat Schwann cell precursors were transfected with Dock8#1, Dock8#2, or control luciferase siRNA. Cell lysates were used for an immunoblotting using the respective antibodies against Dock8 or the control actin or Nck1. The scanned bands were densitometrically analyzed to identify their quantification and were statistically analyzed. Data were evaluated using Student's t-test (**, p<0.01; n=3). In the following experiments, Dock8#1 siRNA was used for Dock8 knockdown. (D, E) The reaggregates of Schwann cell precursors, which were transfected with Dock8 or control siRNA, were placed onto type I collagen-coated dishes and were allowed to migrate outwards from the reaggregates in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml PDGF for 6 h. Schwann cell precursors were immunostained with an anti-p75NTR antibody (green fluorescence). The distance from the center of the reaggregates (indicated by dotted arrows) was measured and statistically analyzed. Data were evaluated using one-way ANOVA (**, p<0.01; n=4). Scale bars indicate 100 µm. (F–H) Similarly, Schwann cell precursor reaggregates were allowed to migrate in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml NRG1 [F], 20 ng/ml NT3 [G], or 20 ng/ml IGF1 [H] for 6 h. Data were evaluated using Student's t-test (**, p<0.01; n=4).

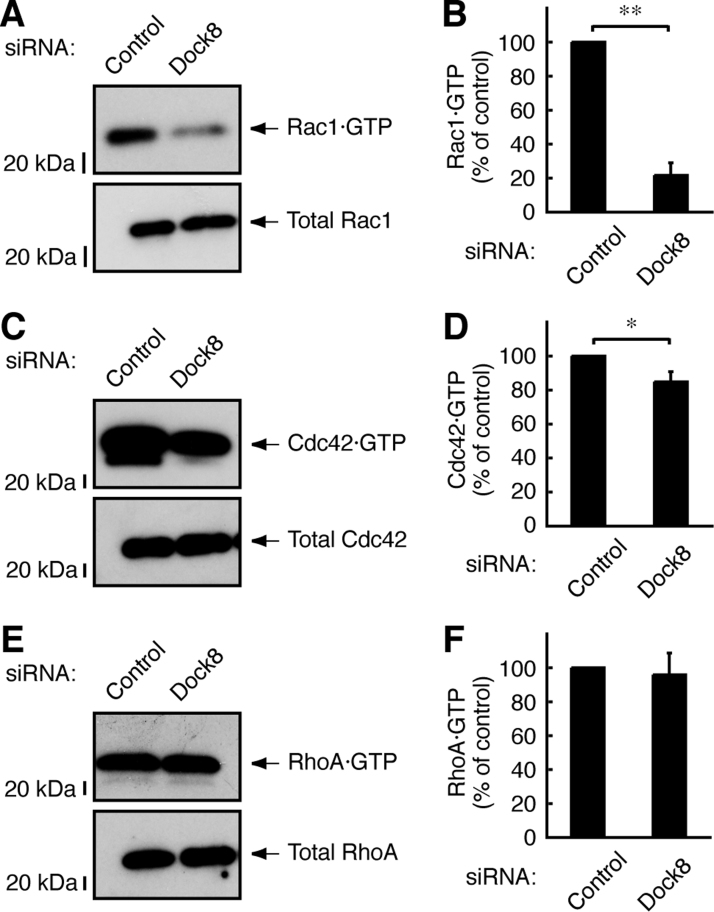

Dock8 is the GEF for Rac1 and Cdc42, but its specificity for Rac1 and Cdc42 is likewise due to cell type or upstream signals [13], [14]. Thus we aimed to explore the effects of Dock8 knockdown on Rac1 and Cdc42 activation. We carried out affinity-precipitation assays using GST-tagged GTP-bound Rac1 and Cdc42 domain of Pak1 (CRIB domain) in the lysates from Schwann cell precursors treated with PDGF. Dock8 knockdown decreased the amount of GTP-bound Rac1 by approximately 70% (Fig. 2A and B). Dock8 knockdown also decreased the amount of GTP-bound Cdc42, but only by approximately 10% (Fig. 2C and D). On the other hand, Dock8 knockdown did not affect GTP-bound RhoA (Fig. 2E and F). Taken together with the results from Fig. 1, these results show that Dock8 preferentially acts upstream of Rac1 and participates in PDGF-mediated Schwann cell precursor migration.

Fig. 2.

Dock8 is involved in the regulation of Rac1 and to the lesser extent Cdc42. (A–D) Schwann cell precursors were transfected with Dock8 or control siRNA. The lysates of cells, which were treated with 20 ng/ml PDGF for 0.5 h, were used for an affinity-precipitation assay using E. coli-produced GST-CRIB in order to precipitate active, GTP-bound Rac1 and Cdc42 specifically. The scanned bands (Rac1 and Cdc42) were densitometrically analyzed. Total GTPases (Rac1 and Cdc42) were also shown. Data were evaluated using Student's t-test (**, p<0.01,*, p<0.05; n=3). (E, F) Similarly, an affinity-precipitation assay with E. coli-produced GST-RBD was performed in order to precipitate active, GTP-bound RhoA specifically. Total RhoA was also shown. Data were evaluated using Student's t-test (**, p<0.01; n=3).

3.2. Nck1 interacts with Dock8 and is involved in PDGF-mediated Schwann cell precursor migration

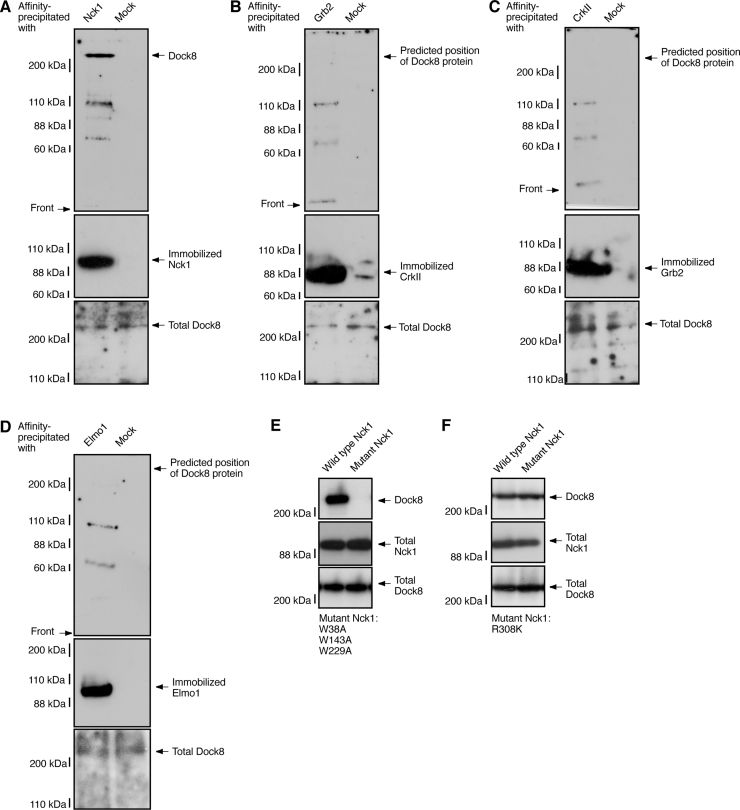

We next sought to identify other protein(s) interacting with Dock8. It has been known that Dock1-Dock5 bind with SH2 and SH3 domain adaptor proteins such as CrkII and the adaptor protein Elmo1 [13], [14]. We first examined whether the SH2 and SH3 domain adaptor proteins interacted with Dock8. We mixed rat sciatic nerve tissue lysates with each of the immobilized SH2 and SH3 domain adaptor proteins, which were first expressed in human embryonic 293T cells and then recovered with ImmunoCruz-resins. Dock8 resulted in affinity-precipitation with Nck1, but not with CrkII and Grb2 (Fig. 3A–C). Dock8 did not interact with Elmo1 (Fig. 3D). We next examined whether the SH2 or SH3 domain contributed to Dock8 interaction. We transfected the plasmid encoding wild type Nck1 or SH3 domain-defective Nck1 mutant (harboring Trp-to-Ala mutation) with Dock8 into 293T cells (Fig. 3E). The lysates were used for precipitation of wild type or mutant Nck1 with Dock8. Dock8 was precipitated with wild type Nck1 but not with SH3 domain-defective Nck1 mutant. In similar experiments, Dock8 was precipitated with SH2 domain-defective Nck1 mutant (harboring Arg-to-Lys mutation, Fig. 3F). Thus Nck1 interacts with Dock8 and their interaction involves Nck1's SH3 domain.

Fig. 3.

Dock8 is specifically affinity-precipitated with Nck1 through Nck1's SH3 domain but not through the SH2 domain. (A–D) The lysates of rat neonatal sciatic nerve tissues were affinity-precipitated with an immobilized GST-tagged Nck1, GST-tagged Grb2, GST-tagged CrkII, or HA-tagged Elmo1 protein. The affinity-precipitates were immunoblotted with an anti-Dock8 antibody. Similarly, adaptor proteins in the precipitates were immunoblotted with an anti-GST or anti-HA antibody. The immunoblots for total Dock8 were also shown. (E) 293T cells were transfected with the plasmids encoding GST-tagged Nck1 (the wild type or the mutant harboring SH3 domain-defective W38A, W143A, and W229A) and FLAG-tagged Dock8. The lysates were used for an immunoprecipitation with an anti-GST antibody and the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with an anti-FLAG antibody (upper panel). Total GST-Nck1 and FLAG-Dock8 were also shown (middle and lower panels). (F) Similarly, 293T cells were transfected with the plasmids encoding GST-Nck1 (the wild type or the mutant harboring SH2 domain-defective R308K) and FLAG-Dock8.

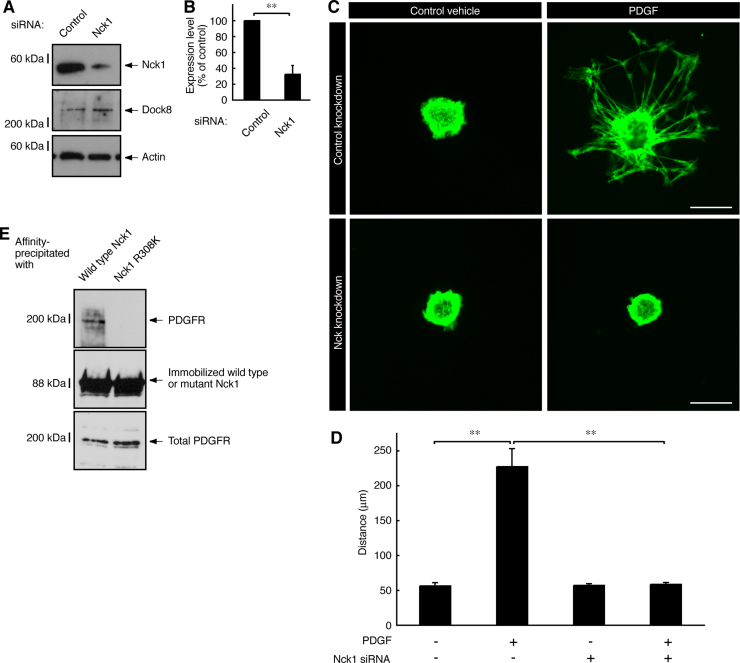

Given that Dock8 interacts with Nck1, we investigated whether Nck1 is involved in Schwann cell precursor migration. We transfected Nck1 siRNA into Schwann cell precursors and confirmed knockdown of Nck1 proteins in Schwann cell precursors (Fig. 4A and B). Nck1 knockdown blocked Schwann cell precursor migration by PDGF (Fig. 4C and D). Under these conditions, PDGF receptor was indeed affinity-precipitated with Nck1 and their interaction occurred through Nck1's SH2 domain (Fig. 4E), supporting the established data regarding the PDGF receptor and Nck1 interaction in other cell types [23].

Fig. 4.

Nck1 is involved in Schwann cell precursor migration by PDGF whose receptor associates with the cognate receptor through Nck1's SH2 domain. (A, B) Schwann cell precursors were transfected with Nck1 or control luciferase siRNA. Cell lysates were used for an immunoblotting using the respective antibodies against Nck1 or the control actin or Dock8. The scanned bands were densitometrically analyzed. Data were evaluated using Student's t-test (**, p<0.01; n=3). (C, D) The reaggregates of Schwann cell precursors, which were transfected with Nck1 or control siRNA, were placed on dishes and were allowed to migrate in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml PDGF. Data were evaluated using one-way ANOVA (**, p<0.01; n=4). Scale bars indicate 100 µm. (E) The lysates of rat neonatal sciatic nerve tissues were affinity-precipitated with an immobilized GST-tagged Nck1 (the wild type or the mutant harboring SH2 domain-defective R308K) protein. The precipitates were also immunoblotted with an anti-GST antibody to detect GST-Nck1. The immunoblot for the total PDGF receptor (designated as PDGFR in the panel) was also shown.

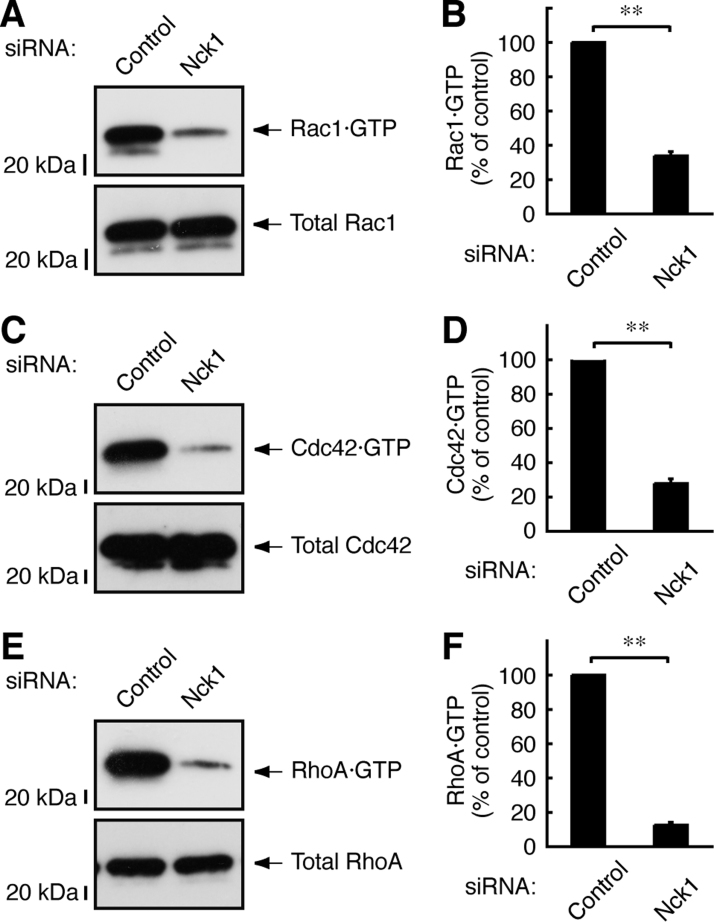

Next, we explored the effects of Nck1 knockdown on Rac1 and Cdc42 activation. Nck1 knockdown decreased the formation not only of GTP-bound Rac1 and Cdc42 but also of GTP-bound RhoA (Fig. 5A–F). The reason why these results do not correlate with those concerning Dock8 knockdown is probably that Nck1 has multiple roles in various cellular events beyond cell morphological changes. In fact, Nck1 knockout results in lethality at an early embryonic developmental stage [24].

Fig. 5.

Nck1 is involved in the regulation of Rho GTPases. (A–D) Schwann cell precursors were transfected with Nck1 or control siRNA. Cell lysates were used for an affinity-precipitation assay using GST-CRIB and for an immunoblotting with an anti-Rho GTPase antibody. Data were evaluated using Student's t-test (**, p<0.01; n=3). (E, F) Similarly, an affinity-precipitation assay using GST-RBD was performed. Data were evaluated using Student's t-test (**, p<0.01; n=3).

3.3. Nck1 interaction with Dock8 is critical for Schwann cell precursor migration

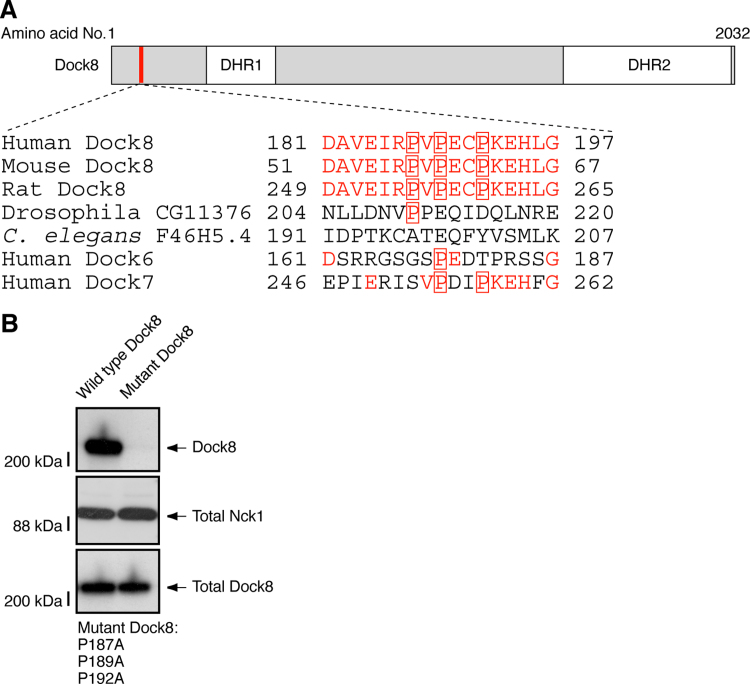

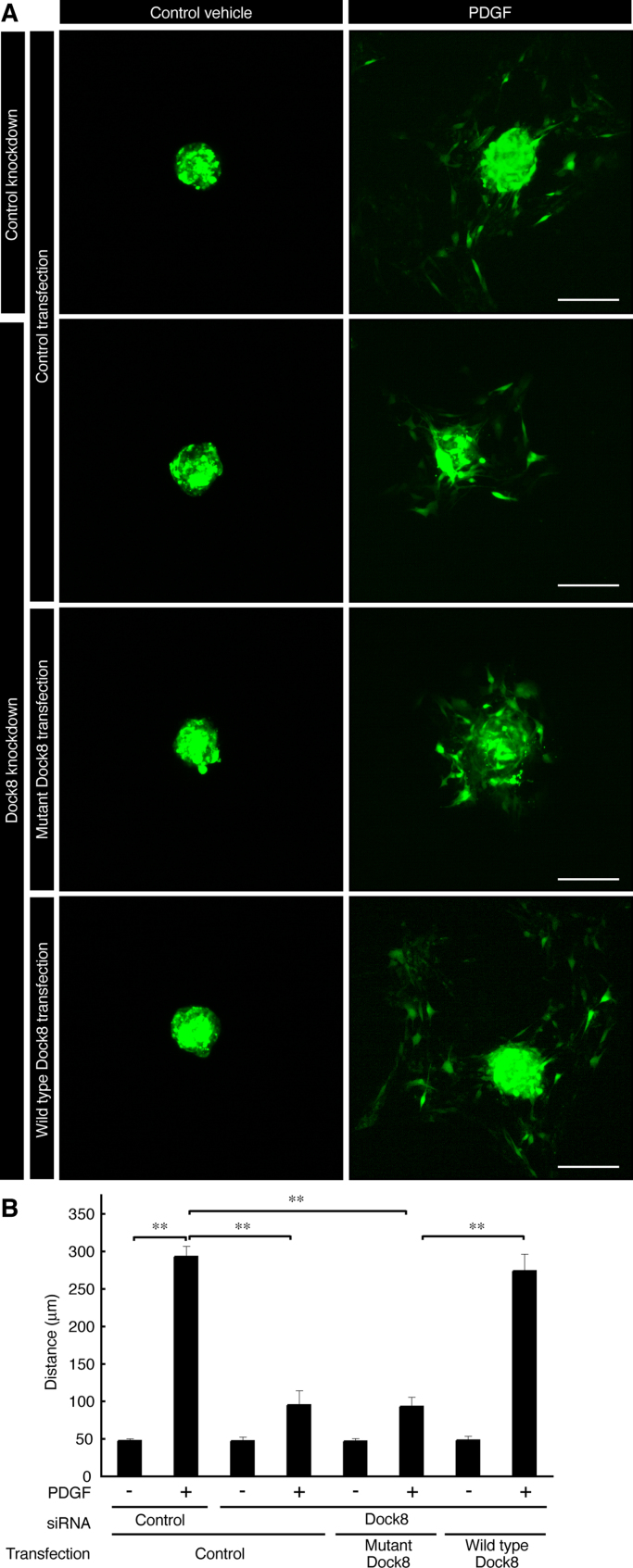

To investigate the role of Nck1 interaction with Dock8 in PDGF-mediated migration of Schwann cell precursors, we produced a mutant construct of Dock8's proline-rich sequence (red-squared proline in Fig. 6A). This mutant did not precipitate with Nck1 (Fig. 6B), in keeping with the result that the SH3 domain of Nck1 participates in this interaction. Thus we cotransfected wild type human Dock8 or this mutant construct into Dock8 or control siRNA-transfected Schwann cell precursors. Reintroduction of the wild type Dock8 construct reversed the siRNA-mediated inhibition of Schwann cell precursor migration, whereas reintroduction of the mutant construct did not restore migration (the 4th panel on the right versus the 3rd panel on the right in Fig. 7A, and the 8th bar versus the 6th in Fig. 7B), indicating that Nck1 interaction with Dock8 plays an important role in PDGF-mediated Schwann cell precursor migration.

Fig. 6.

The proline-rich region of Dock8 is involved in the interaction with Nck1. (A) Domain organizations (unique proline-rich region [red line], DHR1, and DHR2) in human full-length Dock8 (amino acids 1–2032) were depicted. The positions of proline (P, indicated by red squares) in its proline-rich region (amino acids 181–197) were compared to those in other organisms. The amino acids identical to those in human Dock8 were indicated by red characters. (B) 293T cells were transfected with the plasmids encoding FLAG-tagged Dock8 (the wild type or the mutant harboring P187A, P189A, and P192A) and GST-tagged Nck1. The lysates were used for an immunoprecipitation with an anti-GST antibody and the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG antibody (upper panel). Total GST-Nck1 and FLAG-Dock8 were also shown (middle and lower panels).

Fig. 7.

The proline-rich region of Dock8 is involved in PDGF-stimulated Schwann cell precursor migration. (A, B) The reaggregates of Schwann cell precursors, which were co-transfected with Dock8 or control siRNA±the plasmid encoding Dock8 (the wild type or the mutant harboring P187A, P189A, and P192A) and GFP, were placed onto type I collagen-coated dishes and were allowed to migrate outwards from the reaggregates in the presence or absence of 20 ng/ml PDGF for 6 h. The distance from the center of the reaggregates was measured and statistically analyzed. Data were evaluated using one-way ANOVA (**, p<0.01; n=4). Scale bars indicate 100 µm.

4. Discussion

Many previous studies on the molecular mechanisms underlying Schwann cell migration have focused on how intercellular signals between Schwann cells and peripheral neurons promote or inhibit their migration. In contrast, the questions of which intracellular signaling molecules, acting downstream of receptors, control Schwann cell migration and how they control migration are still largely unresolved. Small GTPase family members and regulators act as intracellular switching proteins and play key roles in migration in various cell types; this makes sense given the continuous and dynamic cell morphological changes required by the migration processes [6], [7]. Here, we identify the Rho family GEF Dock8 as the mediator controlling Schwann cell precursor migration. Knockdown of Dock8 in Schwann cell precursors inhibits migration by PDGF but not by NRG1, NT3, or IGF1. Also, Dock8 knockdown preferentially inhibits Rac1, whose activity is essential for cell migration in many other types of cells [7], [8]. Thus Dock8 is required for the regulation of Schwann cell precursor migration; further studies may be needed to understand whether the activity of Dock8 is spatiotemporally regulated during the migration process.

Regulation of migration by Schwann cell growth factor receptors is likely mediated by the respective specific Rho family GEFs. For example, NRG1 binding to Schwann cell ErbB3/2 receptors specifically activates Dock7, upregulating the activities of Rac1 and Cdc42 [15]. Conversely, knockdown of Dock7 largely inhibits NRG1-induced Rac1 and Cdc42 activities. In this case, Dock7 is the ErbB2 receptor substrate; in Dock8, however, the phosphorylation site is not conserved [15]. NT3 activation of Schwann cell TrkC receptor also has the ability to promote the activities of Rac1 and Cdc42 in parallel [25]; but their activation requires two different Dbl-family GEFs. Rac1 activation is mediated by Tiam1 [26], whereas Cdc42 activation is mediated by Dbs [27]. Although the molecular relationship between TrkC and Dock8 remains to be characterized, the specific knockdown of Tiam1 or Dbs by its specific siRNA sufficiently inhibits NT3-induced Rac1 and Cdc42 activation [26], [27]. It is likely that Dock8 specifically acts downstream of Schwann cell PDGF receptor and promotes migration.

Dock8 is the gene product relevant to autosomal recessive Hyper-IgE recurrent infection syndrome. Its deficiency is associated with a variant of combined immunodeficiency [28]. All Dock8 mutations lead to loss of either the Dock8 protein itself or its function. Dock8 protein is not often detected in T lymphocytes in patients. Dock8-deficient T cells exhibit normal cytotoxic activity but impaired proliferation and activation. Dock8 likewise responds to a specific extracellular signal. In each cell type where Dock8 is expressed, Dock8 may be responsible for that cell type's specific extracellular signal, as observed in the relationship between the PDGF receptor and Dock8 in Schwann cell precursors.

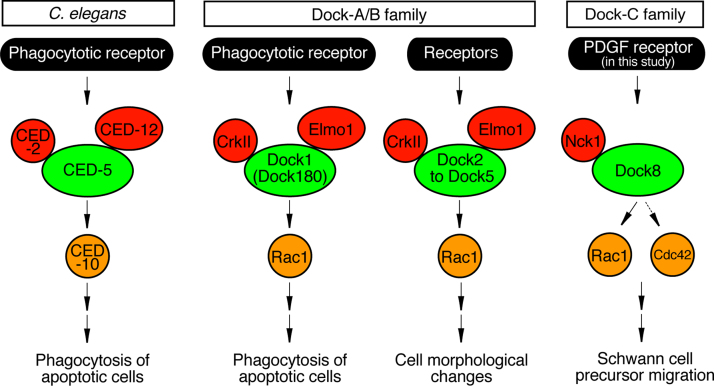

Dock180 is an orthologue of C. elegans cell death-5 (CED-5), which plays the central role in phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. During phagocytosis in C. elegans, CED-5 collaborates with CED-2 and CED-12, which encode mammalian CrkII- and Elmo1-like adaptor proteins, respectively [10], [13]. In Drosophila melanogaster, the Dock180 orthologue Mbc acts in parallel with Elmo and Dcrk to regulate actin cytoskeletal rearrangement in epithelial cells, promoting migration in dorsal closure and morphological differentiation in myogenesis [14]. In mammals, two other CrkII-like adaptor proteins (Grb2 and Nck1) are also known to interact with Dock180 [29], [30]. Despite the genetically-conserved interaction of Dock-A/B members (Dock1-Dock5) with adaptor proteins such as CrkII and Elmo1, Dock-C/D members (Dock6-Dock11) are not able to bind with CrkII and Elmo1. It is likewise known that the Dock-C members Dock6 and Dock7 do not bind with CrkII or Grb2 [15], [19]. Here, we have found that Dock8, another Dock-C member, has the ability to interact with Nck1. Thus the ability to interact with SH2 and SH3 domain adaptor proteins is conserved not only in Dock1-Dock5 but also in Dock8 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Nck1 adaptor protein's interaction with Dock8 is compared with its interactions with other Dock family proteins. C. elegans CED-5 (Dock1 orthologue) and mammalian Dock1-Dock5 (CED-10/Rac1-specific Dock-A/B family members) each form a complex with CED-2 (CrkII) and CED-12 (Elmo1). The complexes containing CED-5 or Dock1 act downstream of receptors controlling phagocytosis as well as other receptors. Among the Rac1 and/or Cdc42-specific Dock-C family members, Dock8 is unique in its interaction with Nck1. Interaction with CrkII-like adaptor proteins is not known in Cdc42-specific Dock-D family members.

Some congenital peripheral demyelinating or dysmyelinating neuropathies are associated with molecules involved in the regulation of the Rho family GTPases, which play a central role in cell morphological changes. Frabin (also known as FYVE, Rho-GEF and pleckstrin homology domain containing 4 [FGD4]), a GEF specifically activating Cdc42, is heterogeneously mutated in autosomal recessive peripheral demyelinating Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease type 4H [31], [32]. The amino acid mutation of Arhgef10 (also called gef10) is linked to a peripheral neuropathy associated with thinly myelinated axons and slowed nerve conduction velocity, similar to the various subtypes of CMT disease [33]. This makes sense as Arhgef10 is a GEF specific for RhoA [34]. In CMT diseases, mutations of Frabin and Arfgef10 are associated with hypomyelination phenotypes. Dock8 and the proteins that interact with it are not currently known to be associated with peripheral neuropathies, but, given that thin myelin sheath organization is often due to defective Schwann cell morphological changes, it will be worth clarifying the relationship of Dock8 and its interacting proteins to peripheral neuropathies.

In the present study, we demonstrate that Nck1's interaction with Dock8, acting downstream of the PDGF receptor, regulates Schwann cell precursor migration. Further studies will allow us to understand the detailed mechanism by which the PDGF receptor, Nck1, and Dock8 regulate Schwann cell precursor migration, but also whether or how they regulate migration under pathological conditions such as injury. Studies in this line may help us to elucidate therapeutic target molecules promoting remyelination after injury or reversing demyelination due to neuropathy through promoting migration of Schwann cell precursors into their proper positions in the nerve tissues.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest.

Author contribution

Y.M. and J.Y. designed this study. J.Y. wrote the paper. Y.M., T.T., and K.K. performed experiments. K.K. and A.T. contributed to animal experiments.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Y. Matsubara, H. Saito, A. Umezawa, and K. Ikenaka for helpful discussion. We also thank S. Kawaguchi for technical assistance. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese MEXT and Japanese MHLW. This work was also supported by grants from Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (the Glial Assembly area and the Comprehensive Brain Science Network area) and partially by grants from the Suzuken Foundation and the Takeda Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at 10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.03.013.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Bunge R.P. Expanding roles for the Schwann cell: ensheathment, myelination, trophism and regeneration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1993;3:805–809. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90157-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirsky R., Jessen K.R. Schwann cell development, differentiation and myelination. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1996;6:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taveggia C., Feltri M.L., Wrabetz L. Signals to promote myelin formation and repair. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010;6:276–287. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira J.A., Lebrun-Julien F., Suter U. Molecular mechanisms regulating myelination in the peripheral nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nave K.A., Werner H.B. Myelination of the nervous system: mechanisms and functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014;30:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salzer J.L. Schwann cell myelination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015;7:a020529. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt A., Hall A. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho GTPases: turning on the switch. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1587–1609. doi: 10.1101/gad.1003302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossman K.L., Der C.J., Sondek J. GEF means go: turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:167–180. doi: 10.1038/nrm1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiyokawa E., Mochizuki N., Kurata T., Matsuda M. Role of Crk oncogene product in physiologic signaling. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 1997;8:329–342. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v8.i4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddien P.W., Horvitz H.R. The engulfment process of programmed cell death in caenorhabditis elegans. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:193–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.022003.114619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Negishi M., Katoh H. Rho family GTPases and dendrite plasticity. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:187–191. doi: 10.1177/1073858404268768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinchen J.M., Ravichandran K.S. Journey to the grave: signaling events regulating removal of apoptotic cells. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:2143–2149. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyamoto Y., Yamauchi J. Cellular signaling of Dock family proteins in neural function. Cell Signal. 2012;22:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurin M., Côté J.F. Insights into the biological functions of Dock family guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Genes Dev. 2015;28:533–547. doi: 10.1101/gad.236349.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamauchi J., Miyamoto Y., Chan J.R., Tanoue A. ErbB2 directly activates the exchange factor Dock7 to promote Schwann cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 2008;181 doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709033. 351-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamauchi J., Miyamoto Y., Hamasaki H., Sanbe A., Kusakawa S., Nakamura A., Tsumura H., Maeda M., Nemoto N., Kawahara K., Torii T., Tanoue A. The atypical guanine-nucleotide exchange factor, Dock7, negatively regulates Schwann cell differentiation and myelination. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:12579–12592. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2738-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W., Katz S., Gupta R., Mayer B.J. Activation of Pak by membrane localization mediated by an SH3 domain from the adaptor protein Nck. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapetina S., Mader C.C., Machida K., Mayer B.J., Koleske A.J. Arg interacts with cortactin to promote adhesion-dependent cell edge protrusion. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:503–519. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyamoto Y., Torii T., Yamamori N., Ogata T., Tanoue A., Yamauchi J. Akt and PP2A reciprocally regulate the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Dock6 to control axon growth of sensory neurons. Sci. Signal. 2013:6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003661. (ra15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamauchi J., Miyamoto Y., Torii T., Takashima S., Kondo K., Kawahara K., Nemoto N., Chan J.R., Tsujimoto G., Tanoue A. Phosphorylation of cytohesin-1 by Fyn is required for initiation of myelination and the extent of myelination during development. Sci. Signal. 2012:5. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002802. (ra69) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratner N., Williams J.P., Kordich J.J., Kim K.A. Schwann cell preparation from single mouse embryos: analyses of neurofibromin function in Schwann cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;407:22–33. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)07003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torii T., Miyamoto Y., Takada S., Tsumura H., Arai M., Nakamura K., Ohbuchi K., Yamamoto M., Tanoue A., Yamauchi J. In vivo knockdown of ErbB3 in mice inhibits Schwann cell precursor migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;452:782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruusala A., Pawson T., Heldin C.H., Aspenström P. Nck adapters are involved in the formation of dorsal ruffles, cell migration, and Rho signaling downstream of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:30034–30044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800913200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fawcett J.P., Georgiou J., Ruston J., Bladt F., Sherman A., Warner N., Saab B.J., Scott R., Roder J.C., Pawson T. Nck adaptor proteins control the organization of neuronal circuits important for walking. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20973–20978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710316105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamauchi J., Chan J.R., Shooter E.M. Neurotrophin 3 activation of TrkC induces Schwann cell migration through the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:14421–14426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336152100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamauchi J., Miyamoto Y., Tanoue A., Shooter E.M., Chan J.R. Ras activation of a Rac1 exchange factor, Tiam1, mediates neurotrophin-3-induced Schwann cell migration. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:14889–14894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507125102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamauchi J., Chan J.R., Miyamoto Y., Tsujimoto G., Shooter E.M. The Neurotrophin-3 Receptor TrkC Directly Phosphorylates and Activates the Nucleotide Exchange Factor Dbs to Enhance Schwann Cell migration. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5198–5203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501160102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farmand S., Sundin M. FarmaHyper-IgE syndromes: recent advances in pathogenesis, diagnostics and clinical care. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2015;22:12–22. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda M., Ota S., Tanimura R., Nakamura H., Matuoka K., Takenawa T., Nagashima K., Kurata T. Interaction between the amino-terminal SH3 domain of CRK and its natural target proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:14468–14472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu N.J., Henkemeyer M. Ephrin-B3 reverse signaling through Grb4 and cytoskeletal regulators mediates axon pruning. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:268–276. doi: 10.1038/nn.2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delague V., Jacquier A., Hamadouche T., Poitelon Y., Baudot C., Boccaccio I., Chouery E., Chaouch M., Kassouri N., Jabbour R., Grid D., Mégarbané A., Haase G., Lévy N. Mutations in FGD4 encoding the Rho GDP/GTP exchange factor FRABIN cause autosomal recessive Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 4H. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:1–16. doi: 10.1086/518428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horn M., Baumann R., Pereira J.A., Sidiropoulos P.N., Somandin C., Welzl H., Stendel C., Lühmann T., Wessig C., Toyka K.V., Relvas J.B., Senderek J., Suter U. Myelin is dependent on the Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 4H disease culprit protein FRABIN/FGD4 in Schwann cells. Brain. 2012;135:3567–3583. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verhoeven K., De Jonghe P., Van de Putte T., Nelis E., Zwijsen A., Verpoorten N., De Vriendt E., Jacobs A., Van Gerwen V., Francis A., Ceuterick C., Huylebroeck D., Timmerman V. Slowed conduction and thin myelination of peripheral nerves associated with mutant Rho guanine-nucleotide exchange factor 10. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:926–932. doi: 10.1086/378159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aoki T., Ueda S., Kataoka T., Satoh T. Regulation of mitotic Spindle Formation by the RhoA Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor ARHGEF10. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material