Abstract

Strapped or “basket-handle” porphyrins have been investigated previously as hemoglobin mimics and catalysts. The facial selectivity of their interactions with axial ligands is a sensitive test for noncovalent bonding. Here the binding of pyridyl ligands to zinc porphyrins with thioester-linked alkyl straps is investigated in solution by NMR spectroscopy and UV–vis titration, and in the solid state by X-ray crystallography. We expected that coordination of the axial ligand would occur on the less hindered face of the porphyrin, away from the strap. Surprisingly, attractive interactions between the strap and the ligand direct axial coordination to the strapped face of the porphyrin, except when the strap is short and tight. The strapped porphyrins were incorporated into π-conjugated cyclic porphyrin hexamers using template-directed synthesis. The strap and the sulfur substituents are located either inside or outside the porphyrin nanoring, depending on the length of the strap. Six-porphyrin nanorings with outwardly pointing sulfur anchors were prepared for exploring quantum interference effects in single-molecule charge transport.

Introduction

Research in the field of molecular electronics was initially focused on the miniaturization of electronic components, such as transistors, to probe the limits of Moore’s law.1,2 However, it was soon realized that, since molecular devices follow the laws of quantum physics, fundamentally new properties and functions may be achieved in these systems.3,4 Recently much effort has been devoted to the exploration of quantum interference (QI) effects in single-molecule electronics.5 There are several possible manifestations of QI, and most experimental studies focus on destructive interference in cross-conjugated molecular wires.6−8 Another form of QI arises from charge transport through two or more spatially separated paths through the same single-molecule junction. If the charge transport is in-phase and coherent then constructive interference will lead to enhanced conductance.5 For example, a symmetric conjugated cyclic molecule diametrically bridged to gold electrodes in a scanning tunneling microscope (STM) would provide two identical pathways for the current and may exhibit constructive QI.9 A structural modification in one of the paths will introduce a phase difference, leading to destructive interference. The application of these concepts to a molecular device forms the basis for a molecular interferometer. This prospect, as well as our interest in understanding the mechanisms of charge transport through single molecules,10 motivated the design of porphyrin nanorings functionalized with anchor groups for binding to STM electrodes.

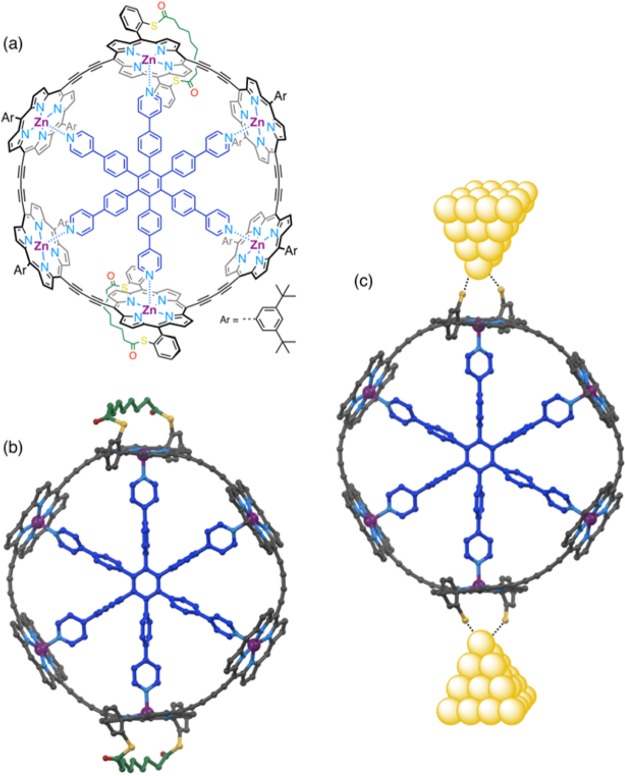

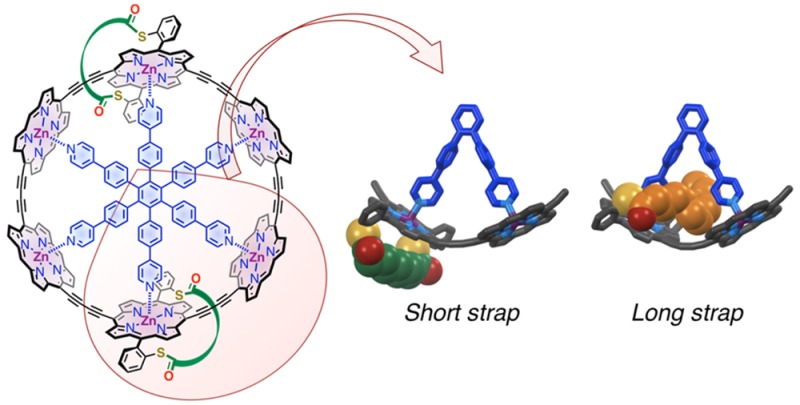

Electronic delocalization and ultrafast energy migration in π-conjugated porphyrin nanorings11−13 mimic the behavior of natural light-harvesting systems and make them interesting targets for the study of charge transport through multiple-path molecules. The six-porphyrin nanoring can easily be prepared by template-directed synthesis.11,14 Recently we showed that this nanoring exhibits antiaromatic and aromatic ring currents around the entire macrocycle in its 4+ and 6+ oxidation states, respectively.15 We have also shown that exchange coupling between paramagnetic copper(II) centers across the diameter of the nanoring provides evidence for QI.16 In order to test for QI in single molecule charge transport, we need to functionalize the nanoring with anchor groups for connection to metal electrodes, which will break the symmetry of the nanoring and introduce new synthetic challenges. The best choice of anchor groups for making electrical connections between molecular wires and gold electrodes in STM junctions is still debated;17,18 the most commonly used anchors include thiols, thioethers, amines, and pyridyl derivatives. Thiol anchors are typically protected as thioacetates, and the thioester bond is spontaneously cleaved in situ on the gold surface to form the S–Au bond.19,20 Our anchoring strategy is derived from the thioacetate approach: we decided to introduce two sulfur anchors on each side of the ring, and to link them via a bis-thioester strap (Figure 1). The sulfur atoms are positioned at the ortho positions of the meso-aryl side groups of the porphyrin. This design was chosen to ensure that the ring will stand vertically on its rim in the junction, with the plane of the six zinc atoms perpendicular to the gold surface. The strap was designed to fulfill two functions: (a) holding both sulfur atoms on the same face of the porphyrin, and (b) making that face sterically hindered to direct binding of the template on the other face of the porphyrin. This strategy was adopted to ensure that the sulfur atoms point outside of the ring for binding to the gold electrodes. The strap is expected to cleave spontaneously on the gold surface, as with -SAc anchors, to form molecular junctions in an STM setup (Figure 1c).19,20

Figure 1.

Target six-porphyrin nanoring functionalized with strapped sulfur anchors on two diametrically opposed porphyrins: (a) chemical structure of the target ring; (b) calculated structure (MOPAC); (c) ring anchored to gold electrodes in a molecular junction. 3,5-Di-tert-butylphenyl side groups and hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity. Color code: C, gray; N, light blue; O, red; S, yellow; Zn, purple; T6 template, dark blue; strap, green.

Strapped or “basket-handle” porphyrins have attracted interest for decades.21−33 They have been designed as models for heme and cytochrome proteins,23,24,34 stereoselective catalysts,35,36 or for the formation of mechanically interlocked structures;32,37,38 however, their interactions with axial ligands remain relatively unexplored. Somewhat counterintuitively, the axial binding sites of the porphyrin away from the strap and near the strap are often referred to as proximal and distal, respectively.39 This terminology originates from synthetic heme models where the strapped (or capped) side of the porphyrin mimics the distal site of hemes with respect to oxygen binding in hemoproteins. Here we prefer to call the two binding sites out (away from the strap; proximal) and in (inside the strap; distal). Due to the bulk of the strap, axial ligands are generally expected to bind to the less hindered out-face, as observed for example for pyridine binding to a phenanthroline-strapped zinc-porphyrin.40 Exceptions to this include cases where the strap has been specially engineered to form a guest-binding pocket,41,42 where ligand-binding on the strapped face is stabilized by hydrogen bonds,43,44 or where the strap contains a coordinating moiety allowing the formation of an intramolecular complex.32,45 The same discrepancy exists in the facial selectivity of guest binding to picket fence-type Zn-porphyrins: steric hindrance on the picket-fenced side often directs pyridine binding to the open (out/proximal) porphyrin face,46,47 although in some cases stabilization by π–π or CH-π interactions48,49 can reverse the face selectivity to the bulky side. In a system described by Mazzanti et al., binding of the pyridine guest even induces an α,β,α,β-to-α,α,α,α atropisomerization of the host porphyrin.48 To the best of our knowledge, no study on the binding mode of nitrogen ligands to Zn-porphyrins with simple alkyl straps has been reported. Straps are typically connected to the porphyrin via oxygen- or nitrogen-based substituents at the ortho position of meso-aryl side groups, while here we describe the synthesis of porphyrin monomer building blocks with various sulfur-based straps.

Results and Discussion

Ortho-Sulfur Substituted Strapped Porphyrin Monomers

Synthesis

The first stage in the synthesis of the strapped six-porphyrin nanorings (Figure 1) is the preparation of strapped porphyrin monomers. Besides the early strategy based on the preparation of a strapped bis-dipyrromethane derivative,21,23 the main synthetic routes to porphyrins strapped across the 5,15-meso positions are (i) preforming the strap as a bridged dialdehyde, which is then reacted with a dipyrromethane to form the strapped porphyrin directly,26,27,33,50 or (ii) preparing a nonstrapped porphyrin with tailored functional groups on 5,15-meso positions and reacting it with a bifunctional bridge to add the strap.25,30,32 In the present case, the strap bridges two sulfur atoms located at the ortho positions of a 5,15-diarylporphyrin (Scheme 1). Employing method (ii) to prepare these systems would involve the potentially difficult separation of two porphyrin atropisomers,22,51−53 so we chose method (i).

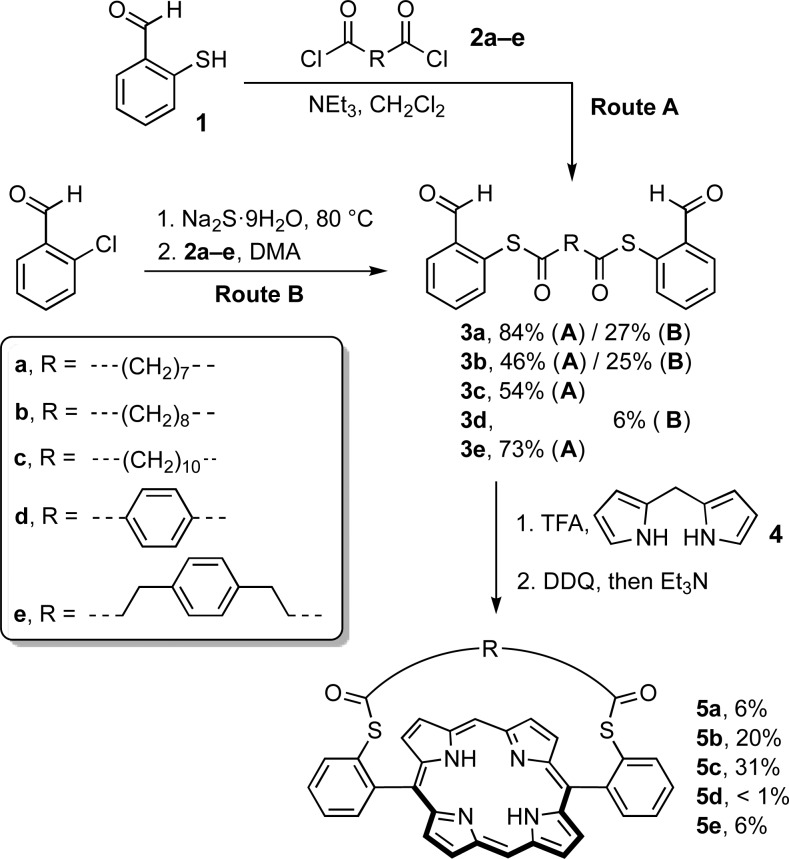

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Strapped Porphyrins 5a–e.

Two routes were explored for the synthesis of the dialdehyde precursors 3a–e, which consist of two benzaldehyde units connected to a central bridge through thioester bonds at their ortho positions (Scheme 1). In Route A, 2-mercaptobenzaldehyde 1 was first prepared following literature procedures.54,55 Then two equivalents of 1 were reacted with diacyl chlorides 2a–e to give the dialdehyde strap precursors 3a–e. Dialdehydes 3a–e were also obtained in a one-pot procedure directly from commercially available 2-chlorobenzaldehyde (route B).56 Treatment of 2-chlorobenzaldehyde with sodium sulfide in N,N-dimethylacetamide at 80 °C gave the corresponding thiolate via aromatic nucleophilic substitution. The diacyl chloride was then added in the same pot, to give the thioester-bridged dialdehydes 3. Route B was generally favored due to the convenience and simplicity of the one-pot procedure, compared to route A, which requires the preparation of oxygen-sensitive 2-mercaptobenzaldehyde 1.54,55

Dialdehydes 3a–e were subjected to classical conditions to form 5,15-diarylporphyrins by reaction with dipyrromethane 4 in the presence of TFA, followed by oxidation with DDQ.57 Initially, a relatively short strap was employed (compounds 3a, C7H14 chain), and the porphyrin condensation was performed using standard concentrations of starting materials 3a (3.5 mM) and 4 (7.0 mM), but the target strapped porphyrin 5a was obtained in only 1% yield. Based on reports that increasing the length or rigidity of the strap can lead to higher yields of porphyrin,26,33 we then investigated straps with longer hydrocarbon chains (compounds 3b, C8H16 chain; and 3c, C10H20 chain, or incorporating a para-phenylene unit (compounds 3d and 3e). Increasing the strap length proved to be advantageous: the porphyrin yield increased from 1 to 8% on extending the hydrocarbon chain from 7 to 10 carbon atoms (Table 1, yield at 3.5 mM). However, in contrast to ether-linked straps,26,58 rigidifying the strap is detrimental to the formation for bis-thioester strapped porphyrins, as compounds 5d and 5e were isolated in less than 1% yield. Odd/even effects in the number of carbon atoms of the strap were not investigated because the precursor to the C9H18 compound is less readily available than 2a–c.

Table 1. Yields of Porphyrin Synthesis: Influence of Concentration and Strap.

Concentration of starting material 3a–e for the porphyrin condensation. Conditions: (i) dialdehyde 3a–e (3.5 mM or 0.35 mM, 1 equiv), dipyrromethane 4 (2 equiv), TFA (2 equiv), DCM, 20 °C, 16 h; (ii) DDQ (3 equiv), 20 °C, 30 min; (iii) NEt3 (2 equiv).

The influence of concentration on the porphyrin yield was investigated, based on the expectation that dilution would favor formation of the strapped porphyrin monomers over longer oligomers.27 We were pleased to find that a 10-fold dilution of the mixture leads to a 4- to 6-fold increase in yield (Table 1). Notably, porphyrin 5c with a linear C10H20 strap was isolated in 31% yield under these conditions. Further screening of reaction conditions showed that the best yields of porphyrins are obtained when the concentration of the dialdehyde starting material 3a–e is in the range 0.28–0.30 mM. Under these conditions porphyrins 5a and 5c are isolated in 8.5% and 33% yield, respectively.

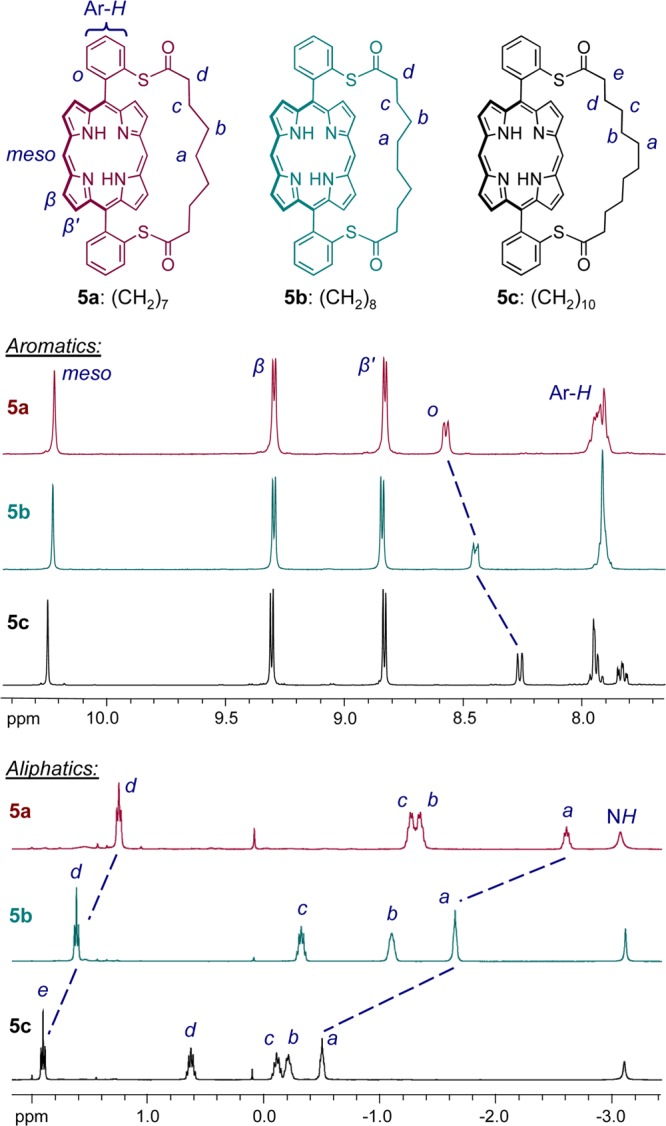

1H NMR: Influence of Strap Length

The 1H NMR spectra of porphyrins 5a–e reflect their C2v-symmetries in solution. The chemical shifts of the meso, beta, and NH protons in compounds 5a–c are typical of 5,15-diarylporphyrins, and are virtually independent of the length of the strap (Figure 2), which indicates that the geometry of the porphyrin ring is unaffected by the strap. The ortho-protons of the meso-aryl groups, on the other hand, are shifted downfield for shorter straps, suggesting that the angle between the porphyrin plane and the aryl ring increases as the strap gets tighter. The strapped structure of compounds 5a–c is confirmed by the significant shielding of the strap protons a–d compared to starting materials 3a–c due to the ring current of the porphyrin. This effect is strongest for the central protons of the strap, which lie above the center of the porphyrin ring. Moreover, the distance between porphyrin ring and strap decreases as the strap gets shorter, as revealed by the increasing shielding of protons a from 5c to 5a. The 1H NMR spectra of these porphyrins suggest that the shortest strap is quite tight, while the longest strap is loose and flexible.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectra of strapped porphyrins 5a–c in CDCl3 (400 MHz, 298 K); the aromatics (top) and aliphatics (bottom) regions are displayed. The chemical shifts of protons a to e highlight the increasing ring current effect of the porphyrin on the strap protons as the strap gets shorter.

Six-Porphyrin Nanorings with Strapped Sulfur Anchors

Synthesis

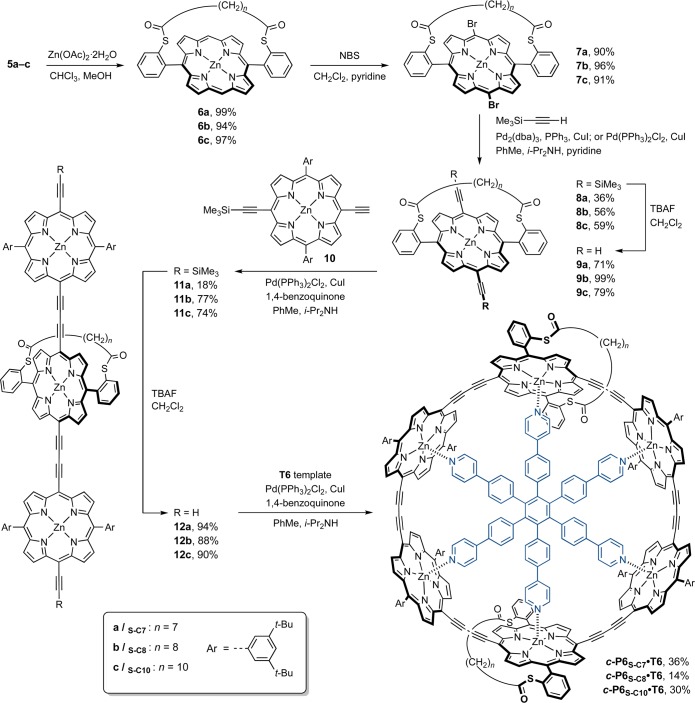

The next stage in the synthetic route consisted in functionalizing the strapped porphyrin monomers in order to incorporate them into conjugated porphyrin nanorings. Typically, six-porphyrin rings are synthesized from ZnII-porphyrin monomers11 or dimers14,59 with terminal acetylenes at the meso positions, which are bound around the hexadentate T6 template before the acetylenes undergo oxidative coupling to give the closed nanoring. In the present case, the synthetic strategy is based on porphyrin trimers composed of a central strapped porphyrin surrounded by two “standard” porphyrins with 3,5-di-tert-butylphenyl side groups.16 These trimers are expected to form a 2:1 complex with T6 to give the six-porphyrin ring with two diametrically opposed strapped porphyrins as the sole six-porphyrin cyclic product after oxidative coupling.

Metalation, bromination, and Sonogashira coupling11 were applied to strapped porphyrins 5a–c to introduce acetylenes at their free meso positions (Scheme 2). First, free-base porphyrins 5a–c were treated with zinc acetate to give strapped ZnII-porphyrins 6a–c in high yields. Bromination with NBS gave dibromo porphyrins 7a–c. In contrast to a recent report on the functionalization of strapped porphyrins,58 the bromination of these compounds proceeded smoothly and in high yields even in the presence of pyridine. Dibromoporphyrins 7a–c were then subjected to Sonogashira coupling with trimethylsilylacetylene, using a catalytic mixture of tris(dibenzylideneacetone)dipalladium(0) (Pd2(dba)3), triphenylphosphine, and copper(I) iodide, to yield the TMS-protected porphyrins 8a–c in moderate yields. Partial decomposition of the starting material was often observed in the Sonogashira coupling, particularly with the short-strapped porphyrin 7a, possibly due to interactions between the palladium catalyst and the sulfur atoms of the strap. Using bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) chloride (PdCl2(PPh3)2) in place of Pd2(dba)3 and triphenylphosphine reduces the decomposition of the starting material.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Six-Porphyrin Nanorings c-P6S–C7-10·T6 Functionalized with Strapped Sulfur Anchors.

The TMS groups of 8a–c were removed using tetrabutylammonium fluoride to give 9a–c, which were reacted with a large excess of monodeprotected porphyrin monomer 10 under oxidative coupling conditions. This reaction yielded the target trimers 11a–c, alongside the dimer, which was separated from the desired product by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). Finally the deprotected trimers 12a–c were obtained by treatment of 11a–c with TBAF, and oxidative coupling in the presence of the T6 template gave the target six-porphyrin nanorings functionalized with strapped sulfur anchors c-P6S–C7–10·T6 in 14–36% isolated yield by size-exclusion chromatography (Scheme 2).

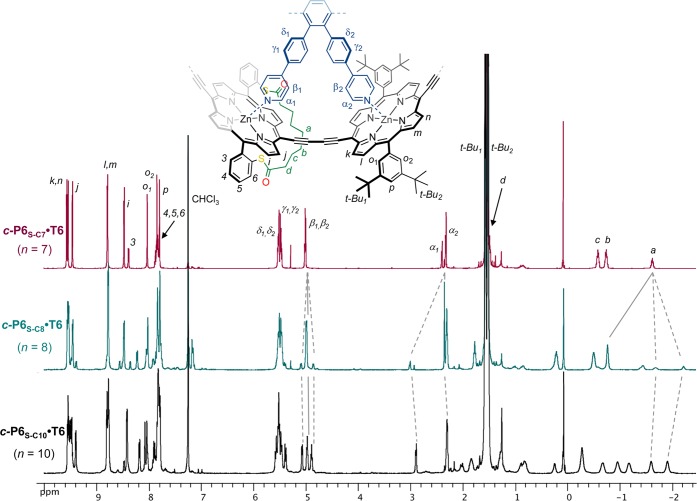

1H NMR Spectroscopy: Strap orientation

While the three porphyrin nanorings c-P6S–C7·T6, c-P6S–C8·T6, and c-P6S–C10·T6 show the expected molecular ions by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, their 1H NMR spectra differ surprisingly (Figure 3). The spectrum of c-P6S–C7·T6 is simple and reflects the expected geometry of the target porphyrin nanoring (Figure 1). The signals were assigned using 2D NMR experiments (COSY and ROESY, see SI Figure S1–S3), and their chemical shifts and multiplicities are consistent with the 1H NMR spectra of previously reported rings.11 For example, the protons of the template experience the ring current of the porphyrins and their signals appear at 2–6 ppm. The splitting of these protons into two sets of signals with 2:1 integration ratios is due to the differentiation of the template legs depending on their binding to strapped or unstrapped porphyrins. The ortho protons of the 3,5-di-tert-butylphenyl side groups are split into two singlets since the protons inside the nanoring are distinct from those outside. The signals of the strapped porphyrin are consistent with the formation of a single product c-P6S–C7·T6 with the expected geometry.

Figure 3.

1H NMR spectra of six-porphyrin nanorings c-P6S–C7–10·T6 (CDCl3, 400 MHz, 298 K). Assignments (based on COSY and NOESY) are given for c-P6S–C7·T6. Dotted lines highlight the appearance of a different product of reduced symmetry in the 1H NMR spectrum of c-P6S–C8·T6. The low-symmetry species is the major product for c-P6S–C10·T6.

However, in the case of c-P6S–C8·T6, the set of signals corresponding to the expected product is accompanied by a second set of signals belonging to a minor product, in a ratio of approximately 1:3. This byproduct has a lower symmetry, as illustrated with the splitting of protons α, β, and a, for example (Figure 3). No separation of the components of c-P6S–C8·T6 could be achieved by analytical GPC, indicating that the isomers have very similar hydrodynamic radii. For c-P6S–C10·T6 the low-symmetry compound is the main product; its signals integrate in a 9:1 ratio to the signals of the expected product. The geminal CH2 strap protons become diastereotopic in the lower symmetry product, and we concluded that the strap is located inside the ring, between two legs of the template, instead of outside the ring as planned in the original design.

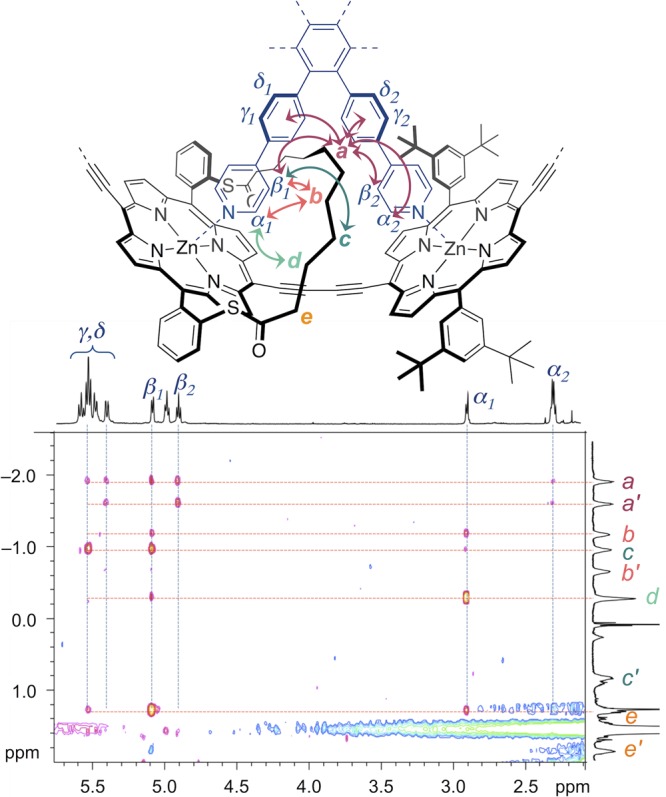

The strap orientation was confirmed by a ROESY NMR experiment on c-P6S–C10·T6. Numerous NOE correlations between protons of the strap and protons of the template were observed (Figure 4), which demonstrates the close proximity of the strap and template. In particular, the central protons of the strap (a) would be located much too far from the template to show any NOE if the strap were oriented outside the ring, but on the contrary, protons a exhibit correlations with five of the template signals. We could not observe any NOE between the strap and the template in the NOESY spectrum of the ring with the short strap, c-P6S–C7·T6 (SI Figure S2–S3). However, we observed a strong NOE between protons α1 of the template and the protons ortho to the porphyrin on the meso-aryl substituents of the strapped porphyrin (protons H3 in Figure 3), which further supports the proposed orientation of the strap outside the ring in this compound.

Figure 4.

Region of 2D-ROESY spectrum (CDCl3, 500 MHz, 298 K) showing NOE correlations between strap and template for c-P6S–C10·T6 (n = 10). NOE-correlated protons are indicated by arrows. Due to their asymmetric environment, the strap protons a–e are diastereotopic and give rise to split signals, for example protons a give two broad signals denoted a and a′ on the vertical 1H NMR trace.

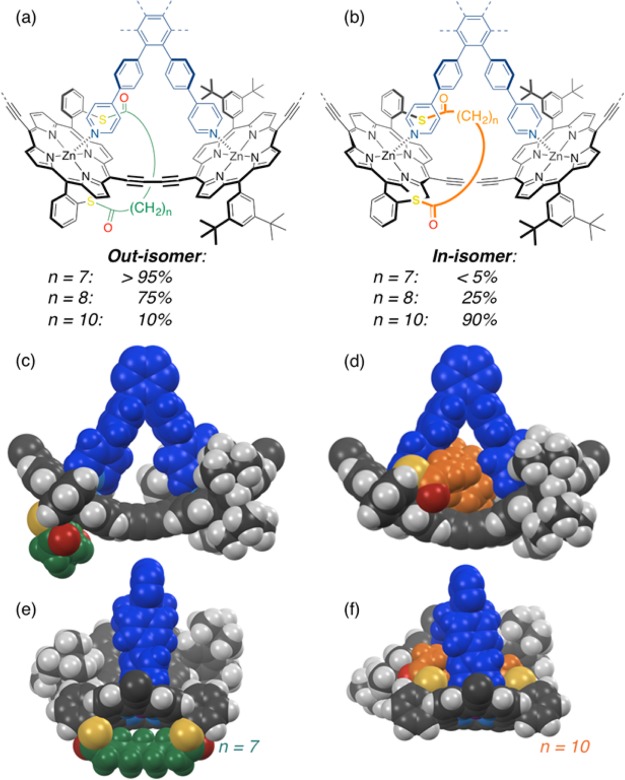

The orientation of the straps and ratios of stereoisomers with straps located inside/outside the rings for compounds c-P6S–C7–10·T6 are summarized in Figure 5. Molecular mechanics calculations show the optimized geometries for portions of the rings with the strap located outside the ring for c-P6S–C7·T6 (short strap) and inside the ring for c-P6S–C10·T6 (long strap). As discussed above, the short strap is geometrically constrained and sits above the center of the porphyrin ring, thereby blocking access so that the template must bind on the other face of the porphyrin, leading to the desired nanoring c-P6S–C7·T6 with sulfur anchors pointing outward. The longer strap, on the other hand, retains some flexibility to bend to the side, allowing template binding on the strapped face of the porphyrin, and resulting in the formation of the nanoring with the undesired orientation of the sulfur atoms pointing toward the center of the ring for c-P6S–C10·T6. The selective formation of this product is probably driven by van der Waals and CH-π interactions between the strap and the template. The mixture of products obtained for c-P6S–C8·T6 shows that the directionality of template binding is the result of a subtle interplay between intermolecular interactions.

Figure 5.

Partial chemical structures of the out- and in-isomers of the porphyrin nanorings c-P6S–C7–10·T6, with the strap oriented respectively outside (a) or inside (b) the ring, between two template legs. The ratios of isomers determined by 1H NMR are indicated for the different strap lengths. Optimized geometries (MOPAC) of the favored binding mode with a short strap ((c),(e); n = 7) and with a long strap ((d),(f); n = 10).

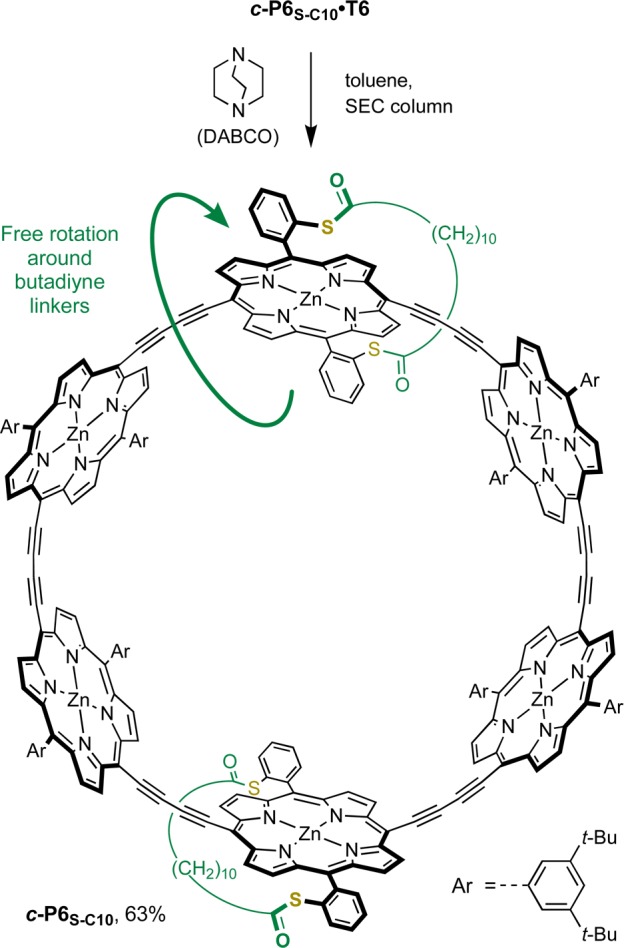

Template Removal

In order to confirm the structure of ring c-P6S–C10·T6, we investigated removal of the template (Scheme 3). It was anticipated that the 1H NMR spectrum of the template-free ring c-P6S–C10 would reflect a higher symmetry than its precursor, since rapid rotation around the butadiyne links in the template-free ring allows the faces of the porphyrins to exchange environment rapidly on the NMR time scale. The binding of the hexa-pyridyl template T6 with cyclic butadiyne-linked six-porphyrin oligomers is highly cooperative, resulting in an extremely high binding constant (∼1036 M–1).60 However, the addition of a large excess of a competing ligand, such as quinuclidine or 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO), displaces T6 to give the template-free ring analogues.11

Scheme 3. Removal of the Template To Yield the Template-Free Nanoring c-P6S–C10.

SEC: size exclusion chromatography, BioBeads SX-1.

The template-ring complex c-P6S–C10·T6 was passed over a size exclusion chromatography (SEC) column in the presence of DABCO (1 M in toluene), to isolate the target ring c-P6S–C10 from the template (Scheme 3). As expected the 1H NMR spectrum of c-P6S–C10 is much simpler than that of c-P6S–C10·T6; splitting is no longer observed for the strap protons, and only one doublet and one triplet are observed for the ortho and para protons of the 3,5-di-tert-butyl aryl groups, respectively (SI Section 4.32). MALDI analysis confirmed the formation of the template-free ring. The simple NMR spectra of the strapped template-free nanoring further supports the proposed structure for the out isomer of c-P6S–C10·T6.

Pyridine Binding to Strapped Zinc-Porphyrin Monomers

1H NMR Study in Solution

Intrigued by the unexpected binding orientation of strap-functionalized porphyrin oligomers to the hexa-pyridyl template T6, we investigated the binding mode of pyridine with strapped Zn-porphyrin monomers. The aim of this study was to determine whether pyridine binds on the strap side or on the opposite side of the porphyrin. We refer to the binding of pyridine to the strapped face of the porphyrin as the in binding mode (distal39), and binding of pyridine to the opposite face as the out binding mode (proximal39).

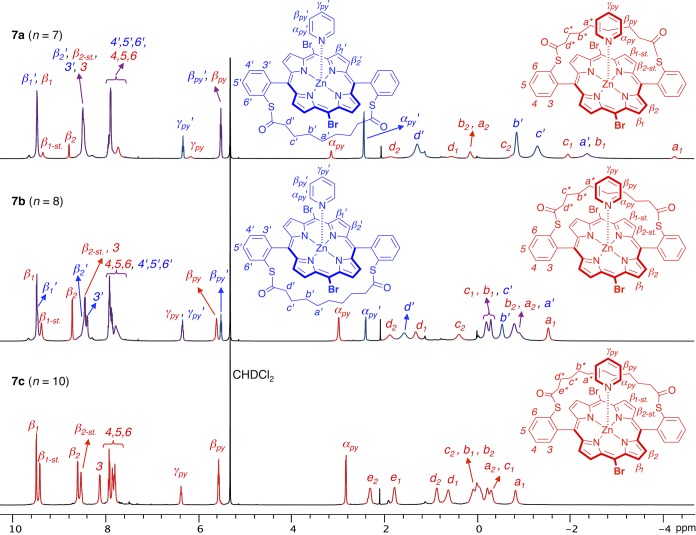

The 1D 1H and 2D COSY and ROESY NMR spectra of 1:1 complexes of the strapped dibromoporphyrins 7a–c with pyridine were measured in CD2Cl2 at 298 and 193 K. At 298 K, the bound pyridine protons gave rise to one set of signals that were significantly shifted upfield compared to free pyridine in solution, due to the ring current of the porphyrin (SI Figure S4). The ROESY spectra at 298 K did not provide any information about the binding mode of the pyridine due the dynamic binding process. However, decreasing the temperature slows down the exchange between bound and unbound pyridine, and the 1H NMR spectra at 193 K proved more informative (Figure 6). At low temperature the in and out complexes give two distinct sets of signals, which were assigned based on symmetry considerations, COSY correlations, and nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) between pyridine and strap protons. The out complexes retain an average C2v symmetry, with two doublets for the beta protons of the porphyrin and 4 or 5 signals for the strap depending on its length. By contrast, in the in complexes, the strap is pushed sideways by the pyridine ligand and the symmetry of the complex is reduced, leading to splitting of the beta proton signals into 4 doublets. In addition, the 1H signals of the strap are also split due to restricted rotational freedom. The assignment of the sets of signals with reduced symmetry to the in complexes was confirmed by the presence of NOEs between the strap and pyridine protons (SI Figure S5–S6).

Figure 6.

1H NMR spectra of 1:1 complexes of strapped dibromoporphyrins 7a–c with pyridine in CD2Cl2 at 193 K (500 MHz). Signals belonging to the out and in complexes are displayed in blue and red, respectively, with overlapping signals displayed in purple. In the in complex, the reduced symmetry of the molecule leads to splitting of the β pyrrole proton signals into 4 doublets (β1-st and β2-st refer to the β protons on the strap side), and restricted conformational freedom leads to splitting of the strap proton signals (noted for example a1 and a2 for the a protons).

For compound 7a (short strap, n = 7) the major isomer is the out complex, consistently with the selective formation of the out isomer of the nanoring c-P6S–C7·T6. The favored binding mode is probably driven by steric hindrance on the strap face, as expected in the initial design. However, the in isomer of the 7a/pyridine complex is also present in solution, and binding of pyridine on the strap face is observed in approximately 23% of complexes according to NMR integrations. For compound 7b (intermediate strap, n = 8), the in complex becomes the major isomer in a 63:37 ratio to the out complex. Finally, for compound 7c (long strap, n = 10), the selectivity for the in complex is virtually complete, and the out isomer is almost undetectable by NMR (Table 2). Even though the flexibility of the longer strap reduces the steric hindrance on the strap face, the complete selectivity for the formation of the in complex is surprising and proves that attractive interactions direct the coordination of pyridine on the strapped face of the porphyrin. These interactions are probably van der Waals or C–H···π interactions between the strap protons and the pyridine ring, and/or C–H···S hydrogen bonding interactions between the sulfur atoms of the strap and the α protons of the pyridine.

Table 2. Ratios of Out and In Isomers in 7a–c/Pyridine Complexes in CD2Cl2 Solution at 193 Ka.

| complex | out isomer | in isomer |

|---|---|---|

| 7a/pyridine | 77% | 23% |

| 7b/pyridine | 37% | 63% |

| 7c/pyridine | <5% | >95% |

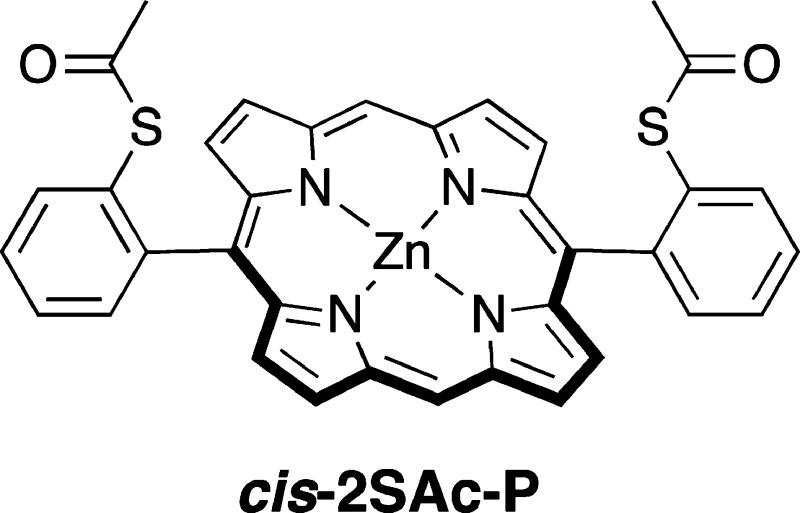

In order to quantify the energy of interactions between the strap and the axial pyridine ligand, we compared the binding constants of three zinc-porphyrins with pyridine: 6a (short strap), 6c (long strap), and their nonstrapped equivalent cis-2SAc-P.61 The binding constants were determined by UV–vis titration in toluene solution at 298 K (see SI for details). We measured a binding constant of 1.2 ± 0.1 × 104 M–1 for cis-2SAc-P, which is in line with values reported for the binding of pyridine to simple zinc-porphyrins.62−64 The lower affinity (7.6 ± 0.1 × 103 M–1) measured for 6a is consistent with the 1H NMR data suggesting that binding to the strapped face of 6a is partially blocked. Binding of pyridine to the long-strapped porphyrin 6c (K = 2.0 ± 0.2 × 104 M–1) is two times stronger than binding to cis-2SAc-P. From the difference in association constants determined for cis-2SAc-P and 6c, we estimate the free energy of the attractive interaction of pyridine to the strap of 6c is about 1.4 kJ mol–1.

The ratios of in/out isomers for the 1:1 complexes of 7a–c with pyridine are shifted toward higher proportions of in species compared to the ratios observed for the isomers of porphyrin nanorings c-P6S–C7–10·T6 (compare ratios in Table 2 with those in Figure 5). This difference may be caused by the lower steric bulk of pyridine compared to the six-legged template T6.

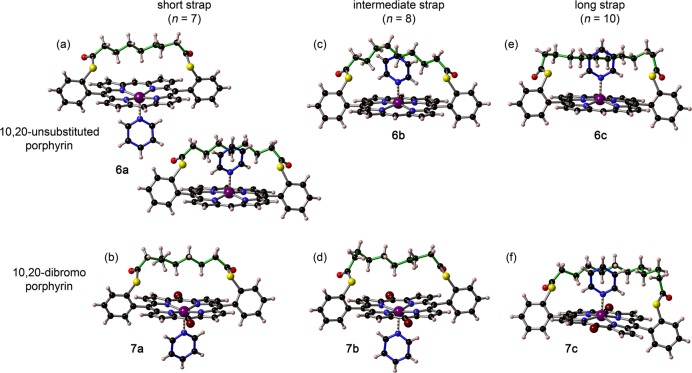

X-ray Diffraction Studies of Strapped Zinc-Porphyrin/Pyridine Complexes

In order to gain more insight into the origin of the selectivity for the in binding mode in strapped Zn-porphyrin/pyridine complexes, the structures of two series of complexes in the solid state were investigated by single-crystal X-ray diffraction.65 Strapped Zn-porphyrins 6a–c (with unsubstituted 10,20 meso positions) and 7a–c (with bromine substituents in 10,20 meso positions) were crystallized by slow diffusion of methanol or acetonitrile vapor into a chloroform solution of the porphyrin in the presence of excess pyridine. The structures of the six complexes as determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction are displayed in Figure 7. The unit cell for 6a (short strap) contains two porphyrin-pyridine complexes. Interestingly, one of the complexes is the in isomer while the other is the out isomer. In the case of the dibrominated analogue 7a, only the out complex crystallizes. These solid-state structures are in remarkably good agreement with the solution study in which a 77:23 ratio of out/in isomers was found for the short strap. Porphyrins with the intermediate strap crystallize either exclusively as the in isomer (6b) or exclusively as the out isomer (7b), which also reflects the behavior in solution where both isomers are present in similar amounts. As expected from the solution NMR spectra, only the in isomers are observed in the crystal state for porphyrins with the long strap (6c and 7c).

Figure 7.

Solid-state structures of 1:1 complexes of pyridine with strapped porphyrin monomers 6a–c and 7a–c from single crystal X-ray diffraction studies. (a),(b) Short strap (n = 7); (c),(d) intermediate strap (n = 8); (e),(f) long strap (n = 10). The unit cell for 6a contains two porphyrin-pyridine complexes. Some disorder is present in the central part of the strap in the crystal structures of 6b and 7c; the minor component is omitted for clarity.

Some disorder is present in the central part of the strap in the crystal structures of 6b and 7c, and only the atomic positions of highest occupancy are shown in Figure 7. This disorder makes it difficult to analyze the interaction between the strap and the pyridine ligand in these complexes. However, the shortest contacts between the CH2 groups of the strap and the C/N atoms of the pyridine ring in 6a, 6b, 6c, and 7c correspond to (C−)H···C distances of 2.9–3.2 Å and (C−)H···N distances of 3.0–3.2 Å. These values are in the expected range for weak C–H···π interactions.66,67 There may also be an attractive interaction between the sulfur atom and the α C–H of the pyridine. Examples of C–H···S interactions are rare,68 but the (C−)H···S distances in the crystal structures of the in complexes of 6a, 6b, 6c, and 7c (3.0–3.2 Å) are consistent with a weak C–H···S hydrogen bonding interaction.

Conclusions

We present the design and synthesis of new porphyrins with linear hydrocarbon straps of different lengths linked to a 5,15-diaryl porphyrin core via thioester bonds, and their incorporation into π-conjugated six-porphyrin nanorings. The conditions of the porphyrin condensation reaction were optimized to reach a 31% yield for the longest strap by reducing the concentration. Intriguing supramolecular behavior was discovered in the template-directed synthesis of strapped nanorings: as the length of the strap is increased, the strapped porphyrins adopted an unexpected orientation with the strap located inside the ring, between two template legs. Solution NMR and UV–vis spectroscopy, and solid-state X-ray crystallography studies, revealed that the facial selectivity in the axial binding of pyridyl-type ligands to strapped porphyrins is the result of a subtle interplay between steric repulsion and attractive interactions, such as van der Waals and weak hydrogen bonding interactions. The free energy of the attractive interaction between the longer strap and pyridine in 6c is only about 1.4 kJ mol–1 at 298 K in toluene. We are currently investigating quantum interference effects in the single-molecule charge transport through the sulfur-functionalized porphyrin nanoring. Experiments to anchor the nanoring with the short straps to gold electrodes via the sulfur atoms and measure its single-molecule conductance are in progress.

Experimental Section

General

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and solvents were used as supplied unless otherwise noted. The starting materials (2-mercaptobenzyl alcohol, thiophenol, diacyl chlorides 2a–d, and 2-chlorobenzaldehyde) were purchased from commercial sources. 2-Mercaptobenzaldehyde 1,54,55 3,3′-(1,4-phenylene)dipropionyl chloride 2e,69−72 dipyrromethane 4,73 hexadentate template T6,14 and zinc 5,15-bis(3,5-bis-tert-butylphenyl)-10,20-bis-trimethylsilylethynylporphyrin11,74,75 were synthesized following (adapted) literature procedures. Dry solvents (THF, CHCl3, DCM, and toluene) were obtained by passing through alumina under N2. Diisopropylamine and diisopropylethylamine were dried over calcium hydride, distilled, and stored under N2 over molecular sieves. NMR data were collected at 400 MHz or at 500 MHz at 298 K. Chemical shifts are quoted as parts per million (ppm) relative to residual CHCl3 (at δ 7.26 ppm for 1H NMR and at δ 77.16 ppm for 13C NMR), and coupling constants (J) are reported in Hertz. trans-2-[3-(4-tert-Butylphenyl)-2-methyl-2-propenylidene]malononitrile (DCTB) was used as a matrix for MALDI-TOF, and the solvent for deposition was either tetrahydrofuran or toluene/5% pyridine. UV–vis-NIR absorbance measurements were recorded at 25 °C using quartz 1 cm cuvettes. Molar absorption coefficients are reported in L mol–1 cm–1. Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was carried out using Bio-Beads S-X1, 200–400 mesh (Bio Rad). Analytical and semipreparative gel permeation chromatography (GPC) was carried out using JAIGEL 3H (20 × 600 mm) and JAIGEL 4H (20 × 600 mm) columns in toluene/1% pyridine as eluent with a flow rate of 3.5 mL/min.

S,S-Bis(2-formylphenyl)nonanebis(thioate) 3a

Route A: 2-Mercaptobenzaldehyde 1 (0.69 g, 5.0 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (45 mL). Azelaic acid dichloride 2a (0.56 g, 2.5 mmol) was added slowly to the stirred solution, followed by triethylamine (0.69 mL, 0.50 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 20 °C under argon for 20 min until completion of the reaction by TLC. Water (50 mL) was added, the organic layer separated, and the aqueous layer further extracted with 2 × 50 mL of DCM. The organic layers were combined, dried with MgSO4, and the solvent evaporated at the rotary evaporator. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica using DCM/cyclohexane 2:1 to 1:0 as eluent. Dialdehyde 3a (0.90 g, 84%) was obtained as a yellow oil that solidified to a gummy off-white solid upon standing.

Route B:56 Na2S·9H2O (25.2 g, 105 mmol) in DMA (500 mL) was stirred at 90 °C for 1 h under argon. 2-Chlorobenzaldehyde (14.1 g, 100 mmol) was slowly added by syringe, and the mixture was stirred at 90 °C for another 30 min. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath, and azelaic acid dichloride 2a (10.7 g, 47.6 mmol) was added dropwise by syringe. The mixture was allowed to warm to 20 °C and stirred for 30 min. Deionized water (500 mL) was added, and the product extracted with DCM (3 × 500 mL). The organic layers were combined, washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, dried with MgSO4, and the solvent evaporated. The crude oily residue was loaded neat on a silica gel column and eluted with cyclohexane/ethyl acetate 95:5 to 90:10. Dialdehyde 3a (6.33 g, 31%) was obtained as a yellow oil that solidified to a gummy off-white solid upon standing.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.22 (s, 2H), 8.04 (dd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (ddd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (m, 2H), 7.49 (dd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.4 Hz, 2H), 2.74 (t, 3J = 7.3 Hz, 4H), 1.74 (tt, 3J = 7.3 Hz, 3J = 7.3 Hz, 4H), 1.41–1.33 ppm (m, 6H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.1, 190.9, 137.0, 136.6, 134.3, 131.2, 130.4, 129.2, 44.0, 28.9, 28.8, 25.5 ppm. HRES-MS: calcd for [C23H24O4S2Na]+ ([M+Na]+) m/z = 451.1008; found 451.1011.

S,S-Bis(2-formylphenyl)decanebis(thioate) 3b

Route A: 2-Mercaptobenzaldehyde 3 (500 mg, 3.62 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (30 mL). Sebacoyl chloride 2b (433 mg, 1.81 mmol) was added slowly to the stirred solution, followed by triethylamine (505 μL, 3.62 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 20 °C under argon for 20 min until completion of the reaction by TLC. Water (50 mL) was added, the organic layer separated, and the aqueous layer further extracted with 2 × 50 mL of DCM. The organic layers were combined, dried with MgSO4, and the solvent evaporated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica using DCM/cyclohexane 2:1 to 1:0 as eluent. Dialdehyde 3b (372 mg, 46%) was obtained as a yellow oil that solidified to a gummy off-white solid upon standing.

Route B:56Na2S·9H2O (17.9 g, 74.6 mmol) in DMA (210 mL) was stirred at 90 °C for 1 h under argon. 2-Chlorobenzaldehyde (8.74 g, 62.1 mmol) was slowly added by syringe, and the mixture was stirred at 90 °C for another 30 min under argon. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath, and sebacoyl chloride 2b (7.44 g, 31.1 mmol) was added dropwise by syringe. The mixture was allowed to warm to 20 °C and stirred for 30 min. Deionized water (500 mL) was added, and the product extracted with DCM (3 × 500 mL). The organic layers were combined, washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, dried with MgSO4, and the solvent evaporated. The crude oily residue was loaded neat on a silica gel column and eluted with cyclohexane/ethyl acetate 95:5 to 90:10. Dialdehyde 3b (3.38 g, 25%) was obtained as a yellow oil that solidified to a gummy off-white solid upon standing.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.22 (s, 2H), 8.04 (dd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (ddd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (m, 2H), 7.49 (dd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.4 Hz, 2H), 2.74 (t, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.73 (tt, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.34 ppm (m, 8H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.3, 191.0, 136.9, 136.6, 134.4, 131.2, 130.4, 129.2, 44.1, 29.1, 29.0, 25.6 ppm. HRES-MS: calcd for [C24H26O4S2Na]+ ([M+Na]+) m/z = 465.1165; found 465.1159.

S,S-Bis(2-formylphenyl)dodecanebis(thioate) 3c

Route A: 2-Mercaptobenzaldehyde 1 (500 mg, 3.62 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (25 mL). Dodecanedioyl dichloride 2c (532 mg, 1.99 mmol) was added slowly to the stirred solution, followed by triethylamine (505 μL, 3.62 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 20 °C under argon for 20 min until completion of the reaction by TLC. Water (50 mL) was added, the organic layer separated, and the aqueous layer further extracted with 2 × 50 mL of DCM. The organic layers were combined, dried with MgSO4, and the solvent evaporated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica using DCM/cyclohexane 2:1 to 1:0 as eluent. Dialdehyde 6c (456 mg, 54%) was obtained as a white solid.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.22 (s, 2H), 8.04 (dd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (ddd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (m, 2H), 7.49 (dd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.3 Hz, 2H), 2.73 (t, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.73 (tt, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.29 ppm (m, 12H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.3, 191.0, 136.9, 136.6, 134.3, 131.3, 130.4, 129.2, 44.1, 29.4, 29.3, 29.0, 25.7 ppm. HRES-MS: calcd for [C26H30O4S2Na]+ ([M+Na]+) m/z = 493.1478; found 493.1470.

S,S-Bis(2-formylphenyl)benzene-1,4-bis(carbothioate) 3d

Route B:56 Na2S·9H2O (15.9 g, 66.0 mmol) in DMA (500 mL) was stirred at 90 °C for 1 h under argon. 2-Chlorobenzaldehyde (9.28 g, 66.0 mmol) was slowly added by syringe, and the mixture was stirred at 90 °C for another 30 min under argon. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath, and terephthaloyl dichloride 2d (6.09 g, 30.0 mmol) was added dropwise by syringe. The mixture was allowed to warm to 20 °C and stirred for 30 min. Deionized water (500 mL) was added, and the product extracted with DCM (3 × 500 mL). The organic layers were combined, washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, dried with MgSO4, and the solvent evaporated. The crude residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography eluted with cyclohexane/DCM 3:1 to 0:1, followed by recrystallization from DCM/CH3CN. Dialdehyde 3d (750 mg, 6%) was obtained as a white solid.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.30 (s, 2H), 8.19 (s, 4H), 8.12 (dd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.72–7.61 ppm (m, 6H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 190.6, 188.4, 140.1, 137.5, 137.0, 134.5, 131.0, 129.9, 129.8, 128.4 ppm. HRES-MS: calcd for [C22H14O4S2Na]+ ([M+Na]+) m/z = 429.0226; found 429.0222.

S,S-Bis(2-formylphenyl)-3,3′-(1,4-phenylene)dipropanethioate 3e

Route A: 2-Mercaptobenzaldehyde 1 (500 mg, 3.62 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (40 mL). 3,3′-(1,4-Phenylene)dipropionyl chloride 2e (492 mg, 1.90 mmol) was added slowly to the stirred solution, followed by triethylamine (505 μL, 3.62 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 20 °C under argon for 30 min until completion of the reaction by TLC. Water (50 mL) was added, the organic layer separated, and the aqueous layer further extracted with 2 × 50 mL of DCM. The organic layers were combined, dried with MgSO4, and the solvent evaporated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica using DCM/cyclohexane 2:1 to 1:0 as eluent. Dialdehyde 3e (610 mg, 73%) was obtained as a white solid.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.05 (s, 2H), 8.03 (dd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (ddd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (m, 2H), 7.45 (dd, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (s, 4H), 3.04 ppm (m, 8H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 195.5, 190.9, 137.9, 136.9, 136.6, 134.3, 130.9, 130.5, 129.2, 128.8, 45.5, 31.1 ppm. HRES-MS: calcd for [C26H22O4S2Na]+ ([M+Na]+) m/z = 485.0852; found 485.0849.

C7–Strapped Free-Base Porphyrin 5a

Dialdehyde 3a (321 mg, 0.750 mmol) and dipyrromethane 4 (219 mg, 1.50 mmol) were dissolved in DCM (2.5 L). The solution was pump-purged with argon, and TFA (115 μL, 1.50 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C under argon for 16 h. DDQ (511 mg, 2.25 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C under argon for 30 min. The solution was concentrated to approximately 100 mL at the rotary evaporator, triethylamine (0.21 mL, 1.5 mmol) was added, and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica using DCM as an eluent. The C7-strapped free-base porphyrin 5a (43 mg, 8.5%) was obtained as a purple microcrystalline solid.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.22 (s, 2H), 9.29 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.83 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.57 (m, 2H), 7.97–7.88 (m, 6H), 1.25 (t, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), –1.24 to –1.37 (m, 8H), –2.61 (p, 3J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), –3.07 ppm (s, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.8, 147.1, 146.1, 145.6, 136.9, 134.4, 132.3, 131.6, 131.1, 129.6, 128.8, 117.1, 105.5, 77.5, 77.4, 77.2, 76.8, 42.8, 26.9, 25.64, 25.59 ppm. HRES-MS: calcd for [C41H35N4O2S2]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 679.2196; found 679.2192. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 409 nm (3.3 × 105), 503 nm (1.6 × 104), 536 nm (4.0 × 103), 576 nm (5.6 × 103), 631 nm (1.2 × 103).

C8–Strapped Free-Base Porphyrin 5b

Dialdehyde 3b (332 mg, 0.750 mmol) and dipyrromethane 4 (219 mg, 1.50 mmol) were dissolved in DCM (2.5 L). The solution was pump-purged with argon, and TFA (115 μL, 1.50 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C under argon for 16 h. DDQ (511 mg, 2.25 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred in the dark at 20° under argon for 30 min. The solution was concentrated to approximately 100 mL at the rotary evaporator, triethylamine (0.21 mL, 1.5 mmol) was added, and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica using DCM as an eluent. The C8-strapped free-base porphyrin 5b (112 mg, 22%) was obtained as a purple microcrystalline solid.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.23 (s, 2H), 9.30 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.84 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.45 (m, 2H), 7.91 (m, 6H), 1.62 (t, 3J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), –0.32 (tt, 3J = 8.0 Hz, 3J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), –1.10 (m, 4H), –1.65 (m, 4H), –3.12 ppm (s, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 197.1, 147.1, 146.0, 145.6, 136.7, 134.7, 132.0, 131.6, 131.0, 129.6, 128.5, 117.1, 105.5, 43.0, 26.7, 26.4, 25.2 ppm. HRES-MS: calcd for [C42H37N4O2S2]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 693.2352; found 693.2347. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 409 nm (3.2 × 105), 503 nm (1.5 × 104), 535 nm (3.4 × 103), 575 nm (4.9 × 103), 630 nm (9.2 × 102).

C10-Strapped Free-Base Porphyrin 5c

Dialdehyde 3c (132 mg, 0.280 mmol) and dipyrromethane 4 (81.9 mg, 0.560 mmol) were dissolved in DCM (1.0 L). The solution was pump-purged with argon, and TFA (43 μL, 0.56 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C under argon for 16 h. DDQ (210 mg, 0.924 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C under argon for 30 min. The solution was concentrated to approximately 50 mL at the rotary evaporator, triethylamine (78 μL, 0.56 mmol) was added, and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica using DCM as an eluent. The C10-strapped free-base porphyrin 5c (66 mg, 33%) was obtained as a purple microcrystalline solid.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.25 (s, 2H), 9.31 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.83 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.26 (d, 3J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.96–7.91 (m, 4H), 7.83 (ddd, 3J = 7.2 Hz, 3J = 6.8 Hz, 4J = 2.2 Hz, 2H), 1.91 (t, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 0.63 (tt, 3J = 7.7 Hz, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), –0.11 (m, 4H), –0.21 (m, 4H), –0.50 (m, 4H), –3.11 ppm (s, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 197.1, 147.3, 145.7, 145.3, 136.4, 135.0, 131.8, 131.7, 130.9, 129.4, 128.1, 117.1, 105.5, 43.1, 27.3, 27.2, 26.9, 25.4 ppm. HRES-MS: calcd for [C44H41N4O2S2]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 721.2665; found 721.2652. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 409 nm (2.7 × 105), 503 nm (1.3 × 104), 535 nm (2.8 × 103), 576 nm (4.3 × 103), 630 nm (8.4 × 102).

1,4-Diethylbenzene-Strapped Free-Base Porphyrin 5e

Dialdehyde 3e (130 mg, 0.280 mmol) and dipyrromethane 4 (81.9 mg, 0.560 mmol) were dissolved in DCM (800 mL). The solution was pump-purged with argon, and TFA (43 μL, 0.56 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C under argon for 16 h. DDQ (210 mg, 0.924 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C under argon for 30 min. The solution was concentrated to approximately 50 mL at the rotary evaporator, triethylamine (78 μL, 0.56 mmol) was added, and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica using DCM as an eluent. The 1,4-diethylbenzene-strapped free-base porphyrin 5e (12 mg, 6.2%) was obtained as a purple microcrystalline solid.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.27 (s, 2H), 9.33 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.89 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.61 (m, 2H), 7.93 (m, 6H), 4.03 (s, 4H), 1.51 (t, 3J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 0.54 (t, 3J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), –3.01 ppm (s, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.6, 147.2, 146.1, 145.6, 136.5, 136.0, 134.9, 132.4, 131.8, 131.1, 129.7, 128.8, 125.7, 117.0, 105.7, 43.8, 29.4 ppm. HRES-MS: calcd for [C44H33N4O2S2]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 713.2039; found 713.2023. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 410 nm (1.7 × 105), 504 nm (1.4 × 104), 536 nm (4.2 × 103), 576 nm (5.1 × 103), 631 nm (1.4 × 103).

C7-Strapped Zinc(II) Porphyrin 6a

C7-strapped free-base porphyrin 5a (660 mg, 0.972 mmol) was dissolved in chloroform (115 mL). A solution of Zn(OAc)2·2H2O (1.07 g, 4.86 mmol) in methanol (15 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C for 16 h. The solution was passed through a plug of silica using chloroform/pyridine 100:1 as an eluent and recrystallized from DCM/pyridine/MeOH to give the C7-strapped zinc(II) porphyrin 6a as its 1:1 complex with pyridine (dark pink solid, 795 mg, 99%).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.14 (s, 2H), 9.28 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.80 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.58 (m, 2H), 7.92–7.85 (m, 6H), 6.41 (m, 1H), 5.62 (m, 2H), 3.17 (m, 2H), 1.26 (t, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), –1.18 (m, 8H), –2.44 ppm (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.9, 150.1, 149.7, 147.7, 144.4, 136.7, 135.8, 134.2, 132.4, 132.0, 131.8, 129.1, 128.1, 122.3, 117.8, 106.2, 43.0, 27.1, 26.1, 25.7 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C41H33N4O2S2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 741.1337; found 741.1665. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 411 nm (3.9 × 105), 539 nm (1.7 × 104), 573 nm (3.2 × 103).

C8-Strapped Zinc(II) Porphyrin 6b

C8-strapped free-base porphyrin 5b (218 mg, 0.315 mmol) was dissolved in chloroform (35 mL). A solution of Zn(OAc)2·2H2O (345 mg, 1.57 mmol) in methanol (3.5 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C for 16 h. The solution was passed through a plug of silica using chloroform/pyridine 100:1 as an eluent and recrystallized from DCM/pyridine/MeOH to give the C8-strapped zinc(II) porphyrin 6b as its 1:1 complex with pyridine (dark pink solid, 247 mg, 94%).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.12 (s, 2H), 9.26 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.82 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.50 (m, 2H), 7.93–7.86 (m, 6H), 1.59 (t, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 4H), –0.24 (m, 4H), –1.20 (m, 4H), –0.27 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.9, 150.2, 149.7, 147.4, 144.3, 136.5, 135.6, 134.4, 132.2, 131.9, 131.8, 129.1, 128.0, 122.1, 117.6, 106.3, 43.2, 27.3, 27.1, 25.4 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C42H35N4O2S2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 755.1493; found 755.1254. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 411 nm (3.9 × 105), 539 nm (1.6 × 104), 572 nm (3.0 × 103).

C10-Strapped Zinc(II) Porphyrin 6c

C8-strapped free-base porphyrin 5c (288 mg, 0.399 mmol) was dissolved in chloroform (40 mL). A solution of Zn(OAc)2·2H2O (438 mg, 2.00 mmol) in methanol (4 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred in the dark at 20 °C for 16 h. The solution was passed through a plug of silica using chloroform/pyridine 100:1 as an eluent and recrystallized from DCM/pyridine/MeOH to give the C10-strapped zinc(II) porphyrin 6c as its 1:1 complex with pyridine (dark pink solid, 333 mg, 97%).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.10 (s, 2H), 9.25 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.82 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.30 (d, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.95–7.79 (m, 6H), 1.94 (t, 3J = 6.9 Hz, 4H), 0.69 (m, 4H), 0.00 (m, 8H), –0.27 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.6, 150.2, 149.6, 146.9, 136.1, 134.9, 131.8, 131.6, 128.9, 127.7, 117.2, 106.1, 43.4, 28.1, 27.8, 27.7, 25.8 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C44H39N4O2S2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 783.1806; found 783.1727. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 411 nm (3.8 × 105), 540 nm (1.6 × 104), 572 nm (2.8 × 103).

C7-Strapped Dibromoporphyrin 7a

To a solution of C7-strapped zinc(II) porphyrin 6a (375 mg, 0.457 mmol) in DCM (55 mL) and pyridine (1 mL), cooled to −5 °C in an ice/NaCl bath, was added NBS (163 mg, 0.913 mmol) in one portion. After stirring in the dark for 10 min, the reaction was allowed to warm to 20 °C and stirred for 1 h; then cyclohexane (55 mL) was added, and the mixture was filtered through a short pad of silica flushed with a mixture of cyclohexane/DCM/pyridine 50:50:1. The solvents were evaporated and the product was recrystallized from DCM/pyridine/CH3CN to give the C7-strapped dibromoporphyrin 7a as its 1:1 complex with pyridine (purple microcrystalline solid, 369 mg, 90% yield).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.56 (d, 3J = 4.7 Hz, 4H), 8.59 (d, 3J = 4.7 Hz, 4H), 8.53–8.44 (m, 2H), 7.93–7.85 (m, 4H), 7.89–7.76 (m, 2H), 6.44 (m, 1H), 5.65 (m, 2H), 2.90 (m, 2H), 1.35 (t, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), –0.88 to –0.95 (m, 8H), –1.93 ppm (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.7, 150.8, 150.4, 147.0, 143.6, 136.8, 136.3, 133.9, 133.3, 133.0, 132.2, 129.4, 128.1, 122.6, 120.0, 105.2, 42.9, 27.3, 26.2, 25.8 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C41H31Br2N4O2S2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 896.9547; found 896.9542. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 428 nm (4.0 × 105), 565 nm (1.6 × 104), 606 nm (6.1 × 103).

C8-Strapped Dibromoporphyrin 7b

To a solution of C8-strapped zinc(II) porphyrin 6b (71 mg, 85 μmol) in DCM (10 mL) and pyridine (0.18 mL), cooled to −5 °C in an ice/NaCl bath, was added NBS (30 mg, 0.17 mmol) in one portion. After stirring in the dark for 10 min, the reaction was allowed to warm to 20 °C and stirred for 1 h; then cyclohexane (10 mL) was added, and the mixture was filtered through a short pad of silica flushed with a mixture of cyclohexane/DCM/pyridine 50:50:1. The solvents were evaporated and the product was recrystallized from DCM/pyridine/CH3CN to give the C8-strapped dibromoporphyrin 7b as its 1:1 complex with pyridine (purple microcrystalline solid, 88 mg, 96% yield).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.54 (d, 3J = 4.7 Hz, 4H), 8.60 (d, 3J = 4.7 Hz, 4H), 8.38 (dd, J = 7.2, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.94–7.77 (m, 6H), 6.42 (m, 1H), 5.64 (m, 2H), 2.91 (m, 2H), 1.61 (t, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), −0.07 to −0.15 (m, 4H), −0.55 to −0.60 (m, 4H), −0.90 to −0.95 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.8, 150.9, 150.4, 146.7, 143.8, 136.6, 136.2, 134.2, 133.3, 133.0, 132.0, 129.3, 128.0, 122.4, 119.9, 105.4, 43.1, 27.4, 27.2, 25.6 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C42H33Br2N4O2S2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 910.9703; found 910.9664. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 428 nm (3.9 × 105), 565 nm (1.6 × 104), 606 nm (6.0 × 103).

C10-Strapped Dibromoporphyrin 7c

To a solution of C10-strapped zinc(II) porphyrin 6c (300 mg, 0.347 mmol) in DCM (40 mL) and pyridine (0.75 mL), cooled to −5 °C in an ice/NaCl bath, was added NBS (124 mg, 0.695 mmol) in one portion. After stirring in the dark for 10 min, the reaction was allowed to warm to 20 °C and stirred for 2 h; then cyclohexane (40 mL) was added, and the mixture was filtered through a short pad of silica flushed with a mixture of cyclohexane/DCM/pyridine 50:50:1. The solvents were evaporated and the product was recrystallized from DCM/pyridine/CH3CN to give the C10-strapped dibromoporphyrin 7c as its 1:1 complex with pyridine (purple microcrystalline solid, 323 mg, 91% yield).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.53 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.62 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.18 (d, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.91 (m, 4H), 7.81–7.77 (m, 2H), 6.47 (m, 1H), 5.68 (m, 2H), 3.18 (m, 2H), 1.98 (t, 3J = 6.9 Hz, 4H), 0.73 (m, 4H), 0.10 (m, 8H), –0.14 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3/0.1% pyridine-d5, 100 MHz): δ = 196.4, 151.0, 150.4, 146.8, 146.4, 136.3, 136.1, 134.7, 133.4, 132.8, 131.7, 129.2, 127.9, 123.0, 119.7, 105.3, 43.5, 28.2, 28.0, 27.8, 25.9 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C44H37Br2N4O2S2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 939.0016; found 939.0018. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 428 nm (3.8 × 105), 565 nm (1.6 × 104), 606 nm (6.4 × 103).

C7-Strapped Bis-TMS Porphyrin 8a

C7-strapped dibromoporphyrin 7a (150 mg, 153 μmol), Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (21.6 mg, 30.6 μmol), and CuI (5.84 mg, 30.6 μmol), were placed in a 2-neck round-bottom flask under argon (three vacuum-argon refill cycles). Toluene (15 mL), diisopropylethylamine (2.4 mL), and pyridine (0.30 mL) were by bubbling with argon for 15 min, and transferred to the round-bottom flask by cannula. Trimethylsilylacetylene (144 μL, 1.02 mmol) was added by syringe. The mixture was stirred at 50 °C under argon atmosphere for 80 min. The solvents were then evaporated, and the residue passed through a short silica gel column using DCM as eluent, to give porphyrin 8a as its 1:1 complex with pyridine (purple solid, 52 mg, 36%).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.54 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.58 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.46 (m, 2H), 7.89–7.85 (m, 6H), 6.52 (m, 1H), 5.79 (m, 2H), 3.65 (m, 2H), 1.34 (t, 3J = 7.3 Hz, 4H), 0.57 (s, 18H), –1.10 (m, 8H), –2.24 ppm (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 197.0, 152.4, 150.2, 147.2, 144.4, 136.7, 136.0, 134.1, 132.2, 132.0, 131.3, 129.2, 128.1, 122.6, 120.4, 108.3, 101.0, 100.9, 42.9, 26.7, 25.7 (2 overlapping signals), 0.5 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C51H49N4O2S2Si2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 933.2127; found 933.1891. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 441 nm (4.0 × 105), 541 nm (3.7 × 103), 581 nm (1.4 × 104), 622 nm (sh, 1.9 × 104), 633 nm (2.8 × 104).

C8-Strapped Bis-TMS Porphyrin 8b

C8-strapped dibromoporphyrin 7b (225 mg, 227 μmol), Pd2(dba)3 (23.5 mg, 22.7 μmol), CuI (8.6 mg, 45 μmol), and PPh3 (11.9 mg, 45.3 μmol) were placed in a 2-neck round-bottom flask under argon. Toluene (20 mL), diisopropylamine (4 mL), and pyridine (0.4 mL) were added, and oxygen was removed by three freeze-pump–thaw cycles. Trimethylsilylacetylene (67 μL, 0.48 mmol) was added by syringe. The mixture was stirred at 55 °C under argon atmosphere for 3 h. The solvents were then evaporated, and the residue passed through a short silica gel column using DCM as eluent. The product was further purified by silica gel chromatography using a cyclohexane/EtOAc/pyridine 10:1:1 mixture as eluent, to give porphyrin 8b as its 1:1 complex with pyridine (purple solid, 131 mg, 56%).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 9.52 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.59 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.38 (m, 2H), 7.91–7.84 (m, 6H), 6.46 (m, 1H), 5.68 (m, 2H), 3.14 (m, 2H), 1.66 (t, 3J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 0.55 (s, 18H), –0.09 (m, 4H), –0.66 (m, 4H), –1.00 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.9, 152.5, 150.3, 146.9, 143.9, 136.6, 136.0, 134.2, 132.1, 131.9, 131.4, 129.2, 128.0, 122.3, 120.3, 108.3, 101.2, 101.1, 77.5, 77.4, 77.2, 76.8, 43.2, 27.2, 27.0, 25.6, 0.5 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C52H51N4O2S2Si2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 947.2283; found 947.2352. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 441 nm (3.9 × 105), 540 nm (3.4 × 103), 581 nm (1.3 × 104), 622 nm (sh, 1.8 × 104), 633 nm (2.7 × 104).

C10-Strapped Bis-TMS Porphyrin 8c

C10-strapped dibromoporphyrin 7c (300 mg, 294 μmol), Pd2(dba)3 (30.4 mg, 29.4 μmol), CuI (11.2 mg, 58.8 μmol), and PPh3 (15.4 mg, 58.8 μmol) were placed in a 2-neck round-bottom flask under argon. Toluene (25 mL), diisopropylamine (5 mL), and pyridine (0.5 mL) were added, and oxygen was removed by three freeze-pump–thaw cycles. Trimethylsilylacetylene (67 μL, 0.48 mmol) was added by syringe. The mixture was stirred at 55 °C under argon atmosphere for 2.5 h. The solvents were then evaporated, and the residue passed through a short silica gel column using DCM as eluent. The product was further purified by silica gel chromatography using a cyclohexane/EtOAc/pyridine 10:1:1 mixture as eluent, to give porphyrin 8c as its 1:1 complex with pyridine (purple solid, 169 mg, 59%).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.51 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.59 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.20 (d, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.93–7.87 (m, 4H), 7.84–7.75 (m, 2H), 6.43 (m, 1H), 5.64 (m, 2H), 3.18 (m, 2H), 1.98 (t, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 0.81–0.71 (m, 4H), 0.54 (s, 18H), 0.24–0.16 (m, 4H), 0.15–0.05 (m, 4H), –0.01 to –0.08 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 196.6, 152.5, 150.4, 146.4, 144.2, 136.3, 136.0, 134.6, 131.9, 131.6, 131.4, 129.1, 127.9, 122.3, 120.2, 108.4, 101.2, 101.1, 43.6, 28.2, 28.1, 27.9, 26.0, 0.5 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C54H55N4O2S2Si2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 975.2596; found 975.2837. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 441 nm (3.9 × 105), 541 nm (3.5 × 103), 583 nm (1.3 × 104), 622 nm (sh, 1.8 × 104), 634 nm (2.8 × 104).

C7-Strapped Bis-Deprotected Porphyrin 9a

C7-strapped bis-TMS porphyrin 8a (52 mg, 56 μmol) was dissolved in DCM (25 mL) and TBAF (0.11 mL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 0.11 mmol) was added. After stirring at 20 °C for 15 min the mixture was passed through a short column of silica gel (DCM/1% pyridine), to give bis-deprotected porphyrin 9a (37 mg, 84%) as a its 1:1 complex with pyridine (dark green solid).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.57 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.60 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.53–8.46 (m, 2H), 7.92–7.80 (m, 6H), 6.92–6.87 (m, 3H), 6.34–6.29 (m, 6H), 5.55–5.50 (m, 6H), 4.10 (s, 2H), 1.40–1.31 (m, 4H), –0.93 to –0.99 (m, 8H), –2.04 to –2.09 ppm (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 196.8, 152.5, 150.4, 147.1, 145.4, 136.8, 136.1, 133.9, 132.4, 132.1, 131.3, 129.3, 128.1, 123.2, 120.4, 99.7, 86.7, 83.4, 43.0, 27.1, 26.1, 25.8 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C45H33N4O2S2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 789.1337; found 789.1344. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 436 nm (3.1 × 105), 575 nm (2.0 × 104), 623 nm (2.1 × 104).

C8-Strapped Bis-Deprotected Porphyrin 9b

C8-strapped bis-TMS porphyrin 8b (80 mg, 78 μmol) was dissolved in DCM (30 mL) and TBAF (0.16 μL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 0.16 mmol) was added. After stirring at 20 °C for 30 min the mixture was passed through a short column of silica gel (DCM), to give the bis-deprotected porphyrin 9b (68 mg, 99%, purple solid) as its 1:1 complex with pyridine.

1H NMR (CDCl3/1% pyridine-d5, 400 MHz): δ = 9.54 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.61 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.43–8.35 (m, 2H), 7.93–7.79 (m, 6H), 4.07 (s, 2H), 1.65 (t, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), –0.09 (tt, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), –0.54 to –0.68 (m, 4H), –0.95 to –1.04 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3/1% pyridine-d5, 100 MHz) δ = 196.7, 152.5, 150.4, 146.8, 136.6, 134.1, 132.3, 131.9, 131.3, 129.2, 128.0, 120.2, 99.9, 86.6, 83.3, 43.2, 27.3, 27.2, 25.5 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C46H35N4O2S2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 803.1493; found 803.1830. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 435 nm (1.8 × 105), 571 nm (9.4 × 103), 622 nm (9.1 × 103).

C10-Strapped Bis-Deprotected Porphyrin 9c

C10-strapped bis-TMS porphyrin 8c (80 mg, 76 μmol) was dissolved in DCM (35 mL) and TBAF (0.15 μL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 0.15 mmol) was added. After stirring at 20 °C for 30 min the mixture was passed through a short column of silica gel (DCM), to give the bis-deprotected porphyrin 13c (63 mg, 91%, purple solid) as its 1:1 complex with pyridine.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.54 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.62 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.20 (d, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.94–7.87 (m, 4H), 7.83–7.74 (m, 2H), 6.41 (m, 1H), 5.65 (m, 2H), 4.06 (s, 2H), 3.24 (m, 2H), 1.98 (t, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 0.81–0.69 (m, 4H), 0.14–0.04 (m, 8H), –0.11 to –0.20 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 196.5, 152.6, 150.5, 146.3, 144.2, 136.3, 136.0, 134.7, 132.1, 131.6, 131.5, 129.1, 127.9, 122.3, 120.1, 99.9, 86.6, 83.5, 43.5, 28.2, 28.0, 27.9, 25.9 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C48H39N4O2S2Zn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 831.1806; found 831.2328. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 435 nm (3.1 × 105), 570 nm (2.6 × 104), 622 nm (2.2 × 104).

Monodeprotected t-Bu Porphyrin 10

Zinc 5,15-bis(3,5-bis-tert-butylphenyl)-10,20-bis-trimethylsilylethynylporphyrin (1.89 g, 2.00 mmol) was dissolved in CHCl3 (750 mL). TBAF (1.0 mL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 1.0 mmol) was diluted in CHCl3 (100 mL), and the resulting solution was slowly added to the porphyrin solution. The mixture was stirred at 20 °C until an ideal statistical mixture was observed by TLC (15 min). The mixture was immediately passed through a plug of silica gel eluted with CHCl3. The mixture of products was further purified by silica gel column chromatography eluted with cyclohexane/pyridine/EtOAc 50:1:1 to 50:3:3, to give the starting material (650 mg, 32%), target monodeprotected product 10 (874 mg, 46%), and bis-deprotected product (358 mg, 20%) as their 1:1 complexes with pyridine (purple solids).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.71 (2 overlapping d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.96 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 8.94 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 8.06 (d, 4J = 1.8 Hz, 4H), 7.84 (t, 4J = 1.8 Hz, 2H), 6.42 (m, 1H), 5.65 (m, 2H), 4.16 (s, 1H), 2.95 (m, 2H), 1.59 (s, 36H), 0.64 ppm (s, 9H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 152.3, 152.1, 150.7, 150.6, 148.6, 143.7, 141.8, 136.0, 133.1, 133.0, 130.9, 130.8, 130.1, 124.0, 122.5, 120.9, 108.7, 100.9, 100.6, 99.0, 87.1, 83.2, 35.2, 31.9, 0.6 ppm. HR-MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C55H61N4SiZn]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 869.3957; found 869.3755. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 435 nm (3.9 × 105), 444 nm (sh, 2.5 × 105), 536 nm (4.2 × 103), 578 nm (1.4 × 104), 620 nm (sh, 2.0 × 104), 631 nm (2.7 × 104).

C7-Strapped Bis-TMS Porphyrin Trimer 11a

Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (18 mg, 26 μmol), CuI (50 mg, 0.26 mmol) and 1,4-benzoquinone (116 mg, 1.07 mmol) were dissolved in toluene (40 mL) and i-Pr2NH (8.5 mL). Monodeprotected t-Bu porphyrin 10 (601 mg, 633 μmol) and C8-strapped bis-deprotected porphyrin 9a (55.0 mg, 63.3 μmol) were dissolved in toluene (40 mL) and i-Pr2NH (1.5 mL), and the porphyrin solution was added to the catalyst mixture. The mixture was stirred at 20 °C for 3 h, then passed through a short silica gel column eluted with DCM/1% pyridine. The mixture of products was purified by SEC column (BioBeads SX1) in toluene/1% pyridine. The target C7-strapped bis-TMS porphyrin trimer 11a (31 mg, 18%) and the dimer of the t-Bu porphyrin were isolated as their 1:3 and 1:2 complexes with pyridine, respectively (dark brown-green solids).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.90 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.80 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.65 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.01 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.90 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.68 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.62–8.52 (m, 2H), 8.06 (d, 4J = 1.9 Hz, 8H), 7.97–7.86 (m, 6H), 7.83 (t, 4J = 1.9 Hz, 4H), 6.67 (t, 3J = 7.6 Hz, 3H), 5.98–5.93 (m, 6H), 3.93–3.88 (m, 6H), 1.58 (s, 72H), 1.47 (t, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 0.61 (s, 18H), –0.73 to –0.78 (m, 8H), –1.76 to –1.81 ppm (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 196.8, 153.3, 153.0, 152.2, 150.9, 150.4, 150.3, 148.7, 147.0, 144.7, 141.7, 137.0, 136.2, 134.0, 133.4, 133.0, 132.7, 132.1, 131.3, 131.0, 130.7, 130.2, 129.4, 128.3, 124.6, 122.9, 121.5, 121.0, 108.6, 101.31, 101.27, 100.9, 99.2, 89.2, 88.2, 82.9, 82.3, 43.2, 35.2, 32.0, 27.4, 26.3, 26.0, 0.6 ppm. MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C155H149N12O2S2Si2Zn3]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 2527.8779 (most abundant isotope); found 2528.1150. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 431 nm (sh, 2.6 × 105), 455 nm (3.5 × 105), 494 nm (2.0 × 105), 586 nm (2.6 × 104), 757 nm (1.8 × 105).

C8-Strapped Bis-TMS Porphyrin Trimer 11b

Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (15 mg, 21 μmol), CuI (41 mg, 0.21 mmol), and 1,4-benzoquinone (93 mg, 0.86 mmol) were dissolved in toluene (35 mL) and i-Pr2NH (7 mL). Monodeprotected t-Bu porphyrin 10 (581 mg, 611 μmol) and C8-strapped bis-deprotected porphyrin 9b (45.0 mg, 50.9 μmol) were dissolved in toluene (35 mL) and i-Pr2NH (1 mL), and the porphyrin solution was added to the catalyst mixture. The mixture was stirred at 20 °C for 3 h, then passed through a short silica gel column eluted with DCM/1% pyridine. The mixture of products was purified by flash silica column chromatography using a gradient of eluents from cyclohexane/EtOAc/pyridine 25:1:1 (elution of the dimer) to 5:1:1 (elution of the trimer). Mixed fractions were further purified by SEC column (BioBeads SX1) in toluene/1% pyridine. The target C8-strapped bis-TMS porphyrin trimer 11b (109 mg, 77%) and the dimer of the t-Bu porphyrin (488 mg) were isolated as their 1:3 and 1:2 complexes with pyridine, respectively (dark brown-green solids).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.91 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.79 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.67 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.02 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.91 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.69 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.53–8.44 (m, 2H), 8.07 (d, 4J = 1.9 Hz, 8H), 7.99–7.86 (m, 6H), 7.84 (t, 4J = 1.9 Hz, 4H), 6.56–6.47 (m, 3H), 5.78–5.73 (m, 6H), 3.20–3.15 (m, 6H), 1.81–1.67 (m, 4H), 1.59 (s, 72H), 0.62 (s, 18H), 0.08–0.03 (m, 4H), −0.40 to −0.45 (m, 4H), −0.72 to −0.77 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 196.9, 153.4, 153.1, 152.2, 150.9, 150.5, 150.3, 148.7, 146.7, 143.9, 141.7, 136.8, 136.2, 134.2, 133.4, 133.0, 132.7, 132.0, 131.3, 131.0, 130.7, 130.1, 129.4, 128.2, 124.6, 122.7, 121.4, 121.0, 108.7, 101.4, 101.3, 101.0, 99.3, 89.1, 88.2, 82.9, 82.4, 43.3, 35.2, 32.0, 27.6, 27.4, 25.7, 0.6 ppm. MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C156H151N12O2S2Si2Zn3]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 2541.8936 (most abundant isotope); found 2541.8623. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 432 nm (2.6 × 105), 455 nm (4.0 × 105), 494 nm (2.3 × 105), 583 nm (2.9 × 104), 744 nm (1.6 × 105).

C10-Strapped Bis-TMS Porphyrin Trimer 11c

Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (1.9 mg, 2.8 μmol), CuI (5.3 mg, 28 μmol), and 1,4-benzoquinone (12 mg, 0.11 mmol) were dissolved in toluene (5 mL) and i-Pr2NH (1 mL). Monodeprotected t-Bu porphyrin 10 (75 mg, 79 μmol) and C10-strapped bis-deprotected porphyrin 9c (6.0 mg, 6.6 μmol) were dissolved in toluene (4 mL), and the porphyrin solution was added to the catalyst mixture. The mixture was stirred at 20 °C for 3 h, then passed through a short silica gel column eluted with DCM/1% pyridine. The mixture of products was further purified by flash silica column chromatography using a gradient of eluents from cyclohexane/EtOAc/pyridine 25:1:1 (elution of the dimer) to 5:1:1 (elution of the trimer), to give the target C10-strapped bis-TMS porphyrin trimer 11c (14 mg, 74%) and the dimer of the t-Bu porphyrin (59 mg) as their 1:3 and 1:2 complexes with pyridine, respectively (dark brown-green solids).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.89 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.79 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.67 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.02 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.92 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.72 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.35–8.28 (m, 2H), 8.07 (d, 4J = 1.8 Hz, 8H), 8.00–7.93 (m, 4H), 7.91–7.85 (m, 2H), 7.84 (t, 4J = 1.8 Hz, 4H), 6.71–6.63 (m, 3H), 6.00–5.91 (m, 6H), 3.94–3.88 (m, 6H), 2.08 (t, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 1.60 (s, 72H), 0.90 (tt, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 0.63 (s, 18H), 0.44–0.37 (m, 4H), 0.30–0.23 (m, 4H), 0.21–0.13 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 196.6, 153.4, 153.0, 152.2, 150.9, 150.4 (2 overlapping signals), 148.7, 146.2, 144.8, 141.7, 136.4, 136.2, 134.6, 133.4, 133.0, 132.5, 131.6, 131.4, 131.0, 130.7, 130.1, 129.3, 128.1, 124.6, 122.8, 121.2, 121.0, 108.7, 101.27, 101.25, 101.0, 99.2, 89.1, 88.2, 83.0, 82.3, 43.7, 35.2, 32.0, 28.4, 28.2, 28.0, 26.1, 0.6 ppm. MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C158H155N12O2S2Si2Zn3]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 2569.9250 (most abundant isotope); found 2569.6738. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 432 nm (2.7 × 105), 455 nm (4.3 × 105), 494 nm (2.5 × 105), 583 nm (3.1 × 104), 744 nm (1.8 × 105).

C7-Strapped Bis-Deprotected Porphyrin Trimer 12a

C7-strapped bis-TMS porphyrin trimer 11a (30 mg, 12 μmol) was dissolved in DCM (10 mL), and TBAF (24 μL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 24 μmol) was added. After stirring at 20 °C for 20 min the mixture was passed through a short plug of silica gel (DCM/pyridine 1%) to give the bis-deprotected trimer 12a as a dark brown-green solid (26 mg, 94%).

1H NMR (CDCl3/1% pyridine-d5, 400 MHz): δ = 9.92 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 9.80 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 9.68 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 9.02 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.93 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.69 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.60–8.53 (m, 2H), 8.06 (d, 4J = 1.8 Hz, 8H), 7.97–7.86 (m, 6H), 7.83 (t, 4J = 1.8 Hz, 4H), 4.17 (s, 2H), 1.58 (s, 72H), 1.48 (t, 3J = 7.0 Hz, 4H), –0.73 to –0.80 (m, 8H), –1.74 to –1.81 ppm (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3/1% pyridine-d5, 100 MHz) δ = 196.8, 153.3, 153.0, 152.3, 150.9, 150.5, 150.2, 148.7, 147.0, 141.7, 137.0, 133.9, 133.4, 133.1, 132.7, 132.1, 131.3, 130.9, 130.7, 130.1, 129.4, 128.2, 124.5, 121.5, 121.0, 100.8, 99.8, 99.3, 89.1, 88.2, 87.0, 83.5, 82.8, 82.4, 43.1, 35.2, 31.9, 27.4, 26.3, 26.0 ppm. MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C149H132N12O2S2Zn3]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 2383.7986 (most abundant isotope); found 2383.6960. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 430 nm (3.0 × 105), 453 nm (4.2 × 105), 495 nm (2.8 × 105), 582 nm (3.5 × 104), 743 nm (1.9 × 105).

C8-Strapped Bis-Deprotected Porphyrin Trimer 12b

C8-strapped bis-TMS porphyrin trimer 11b (50 mg, 18 μmol) was dissolved in DCM (15 mL), and TBAF (36 μL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 36 μmol) was added. After stirring at 20 °C for 45 min the mixture was passed through a short plug of silica gel (DCM) and recrystallized from DCM/CH3CN to give the bis-deprotected trimer 12b as a dark brown-green solid (41 mg, 88%).

1H NMR (CDCl3/1% pyridine-d5, 500 MHz): δ = 9.90 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.78 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.67 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 9.01 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.92 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.70 (d, 3J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 8.48 (m, 2H), 8.06 (d, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 8H), 7.96–7.89 (m, 6H), 7.82 (t, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 4H), 4.17 (s, 2H), 1.77 (t, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.57 (s, 72H), 0.09 (m, 4H), –0.42 (m, 4H), –0.77 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3/1% pyridine-d5, 125 MHz): δ = 196.8, 153.3, 153.0, 152.2, 150.9, 150.5, 150.3, 149.5, 148.7, 146.7, 141.7, 136.7, 136.0, 134.2, 133.4, 133.1, 132.6, 131.9, 131.3, 130.9, 130.7, 130.1, 129.3, 128.1, 124.5, 123.7, 121.4, 121.0, 100.9, 99.8, 99.3, 89.0, 88.2, 87.0, 83.5, 82.7, 82.4, 43.3, 35.2, 31.9, 29.8, 27.5, 27.3, 25.7 ppm. MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C150H135N12O2S2Zn3]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 2397.8145 (most abundant isotope); found 2397.6467. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 430 nm (2.8 × 105), 453 nm (3.9 × 105), 493 nm (2.9 × 105), 579 nm (4.0 × 104), 739 nm (1.6 × 105).

C10-Strapped Bis-Deprotected Porphyrin Trimer 12c

C10-strapped bis-TMS porphyrin trimer 11c (120 mg, 42.8 μmol) was dissolved in DCM (40 mL), and TBAF (86 μL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 86 μmol) was added. After stirring at 20 °C for 45 min the mixture was passed through a short plug of silica gel (DCM) to give bis-deprotected trimer 12c as its 1:3 complex with pyridine (dark brown-green solid, 112 mg, 98%).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 9.90 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 9.79 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 9.69 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 9.02 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.94 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.72 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.35–8.28 (m, 2H), 8.07 (d, 4J = 1.8 Hz, 8H), 8.00–7.93 (m, 4H), 7.91–7.85 (m, 2H), 7.84 (t, 4J = 1.8 Hz, 4H), 7.03–6.93 (m, 3H), 6.41–6.33 (m, 6H), 5.43–5.38 (m, 6H), 4.18 (s, 2H), 2.08 (t, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 1.59 (s, 72H), 0.90 (tt, 3J = 7.1 Hz, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 0.44–0.39 (m, 4H), 0.30–0.21 (m, 4H), 0.20–0.13 ppm (m, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 196.6, 153.4, 153.0, 152.3, 150.9, 150.5, 150.4, 148.7, 146.4, 146.2, 141.7, 136.4, 136.1, 134.6, 133.4, 133.1, 132.5, 131.7, 131.4, 130.9, 130.7, 130.1, 129.3, 128.1, 124.5, 123.1, 121.2, 121.0, 101.0, 99.8, 99.4, 89.0, 88.2, 87.0, 83.5, 83.0, 82.4, 43.7, 35.2, 32.0, 28.4, 28.2, 28.0, 26.1 ppm. MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C152H139N12O2S2Zn3]+ ([M+H]+) m/z = 2425.8457 (most abundant isotope); found 2425.7590. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 429 nm (2.9 × 105), 453 nm (4.4 × 105), 494 nm (2.9 × 105), 581 nm (3.5 × 104), 740 nm (1.9 × 105).

C7-Strapped Porphyrin Nanoring c-P6S–C7·T6

Hexadentate-template T6 (1.3 mg, 1.3 μmol) and C7-strapped deprotected porphyrin trimer 12a (6.1 mg, 2.6 μmol) were dissolved in a mixture of chloroform (1.7 mL) and diisopropylamine (0.09 mL) and sonicated for 2 h. A catalyst solution was prepared by dissolving Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (0.54 mg, 0.77 μmol), CuI (1.5 mg, 7.7 μmol), and benzoquinone (1.1 mg, 0.010 mmol) in a mixture of CHCl3 (1.70 mL) and diisopropylamine (0.10 mL). The catalyst solution was added to the solution of hexadentate template and deprotected porphyrin trimer, and the mixture was stirred at 20 °C for 4 h under N2 atmosphere. The mixture was passed directly through an alumina plug (CHCl3) and the solvents evaporated. Preparative size exclusion chromatography in toluene afforded the C7-strapped porphyrin nanoring c-P6S–C7·T6 as a brown-red solid. (5.0 mg, 67%).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ = 9.58 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 8H), 9.56 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 8H), 9.47 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.81 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.80 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 8.49 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 8H), 8.40 (dd, 3J = 6.6 Hz, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 4H), 8.07–8.02 (m, 4H), 7.91–7.86 (m, 4H), 7.86 (t, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 8H), 7.85–7.82 (m, 8H), 7.81 (t, 4J = 1.7 Hz, 8H), 5.59–5.43 (m, 24H), 5.05–4.99 (m, 12H), 2.44–2.38 (m, 4H), 2.36–2.30 (m, 8H), 1.58 (s, 72H), 1.54 (s, 72H), 1.49 (t, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 8H), –0.58 (tt, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 8H), –0.74 (tt, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 3J = 7.3 Hz, 8H), –1.62 ppm (p, 3J = 7.3 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ = 196.7, 151.6, 151.53, 151.47, 150.24, 150.22, 149.6, 149.1, 148.5, 146.54, 146.52, 146.3, 143.1, 143.0, 141.3, 140.11, 140.05, 138.9, 138.8, 137.0, 133.8, 133.1, 133.00, 132.3, 132.2, 132.0, 130.9, 130.53, 130.50, 129.6, 129.3, 128.0, 125.5, 124.0, 121.9, 121.1, 119.3, 119.2, 100.7, 100.2, 99.9, 96.9, 96.6, 96.0, 89.6, 89.5, 89.2, 42.8, 35.2, 35.1, 32.0, 31.9, 26.7, 25.8, 25.5 ppm. MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C370H308N30O4S4Zn6]+ (M+) m/z = 5758.9 (most abundant isotope); found 5759.0. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 433 nm (sh, 2.3 × 105), 483 nm (4.9 × 105), 769 nm (3.2 × 105), 806 nm (4.4 × 105), 847 nm (3.7 × 105).

C8-Strapped Porphyrin Nanoring c-P6S–C8·T6

Hexadentate template T6 (5.98 mg, 6.00 μmol) and C8-strapped bis-deprotected porphyrin trimer 12b (31.6 mg, 12.0 μmol) were dissolved in CHCl3 (12 mL) and sonicated for 30 min. A catalyst solution was prepared by dissolving Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (2.53 mg, 3.60 μmol), CuI (6.86 mg, 36.0 μmol), and 1,4-benzoquinone (5.19 mg, 48.0 μmol) in CHCl3 (3 mL) and diisopropylamine (77 μL). The template and trimer solution was cooled to 20 °C and the catalysts solution was added. The mixture was stirred at 20 °C for 2 h. The mixture was passed through a plug of alumina using CHCl3 as eluent, then through a SEC column (BioBeads SX1) in CHCl3, to give the C8-strapped porphyrin nanoring c-P6S–C8·T6 as a mixture of isomers in 3:1 ratio based on NMR integration (brown-red solid, 5.0 mg, 14%).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz, major isomer): δ = 9.57 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 8H), 9.54 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 8H), 9.47 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 8H), 8.79 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 16H), 8.49 (d, 3J = 4.5 Hz, 8H), 8.24 (d, 3J = 6.7 Hz, 4H), 8.03 (s, 8H), 7.94–7.78 (m, 12H), 7.85 (s, 8H), 7.80 (s, 8H), 5.54–5.47 (m, 24H), 5.03–4.97 (m, 12H), 2.36–2.31 (m, 12H), 1.78 (t, 3J = 6.6 Hz, 8H), 1.57 (s, 72H), 1.53 (s, 72H), 0.27–0.16 (m, 8H), –0.44 to –0.55 (m, 8H), –0.73 to –0.80 ppm (m, 8H). MALDI-TOF: calcd for [C372H312N30O4S4Zn6]+ (M+) m/z = 5787.0 (most abundant isotope); found 5787.0. UV–vis (CHCl3, 25 °C): λmax (ε) 433 nm (sh, 2.6 × 105), 483 nm (4.9 × 105), 769 nm (3.1 × 105), 805 nm (4.1 × 105), 846 nm (3.6 × 105).

C10-Strapped Porphyrin Nanoring c-P6S–C10·T6