Abstract

This paper offers an integrative understanding of the intersection between “health” and “death” from the perspective of the terror management health model. After highlighting the potential for health-related situations to elicit concerns about mortality, we turn to the question, how do thoughts of death influence health decision-making? Across varied health domains, the answer depends on whether these cognitions are in conscious awareness or not. When mortality concerns are conscious, people engage in healthy intentions and behavior if efficacy and coping resources are present. In contrast, when contending with accessible but non-conscious thoughts of death, health relevant decisions are guided more by esteem implications of the behavior. Lastly, we present research suggesting how these processes can be leveraged to facilitate health promotion and reduce health risk

Keywords: health decision-making, risky behavior, terror management, death, mortality salience

People routinely navigate choices with important consequences for their physical health. They go to the gym, smoke a cigarette with friends, work on their tan, order a salad instead of a double bacon cheeseburger, and get that recommended colonoscopy. Concerns about death would seem relevant to these and other everyday health decisions. Yet it was not until the terror management health model (TMHM) that this relevance was programmatically considered (Goldenberg & Arndt, 2008). The model was born, in fact, from observations of reciprocal neglect. Health psychology largely ignored motivational implications associated with concerns about mortality, while terror management theory (TMT), despite inspiring considerable research about social psychological consequences of this awareness, was relatively silent about decisions with implications for physical health. In the present paper we consider how the TMHM bridges this intersection between health and death. We articulate the theoretical foundation for the model and then highlight insights it has generated for how health-relevant contexts implicate awareness of mortality, how this awareness affects everyday health decisions, and how to foster better health outcomes.

THE GENESIS OF THE TMHM

TMT (Greenberg, Solomon, & Pyszczynski, 1986) builds from a tradition of existential and psychodynamic theory (e.g., Becker, 1973) to posit that people need to psychologically manage the unsettling implications of knowing, not just that death is inevitable, but that it could happen at any time. They do this by identifying with cultural belief systems (i.e., worldviews), which enable people to view themselves as valuable members (i.e., have self-esteem) of a cultural reality that persists beyond their own physical demise. The theory has inspired hundred of studies around the globe and been applied to an array of human social behaviors (see e.g., Pyszczynksi, Solomon, & Greenberg, 2015).

After the initial wave of TMT research, studies increasingly suggested that people defend against conscious and non-conscious awareness of mortality in different ways (Pyszczynksi, Greenberg, & Solomon, 1999). When thoughts of mortality are conscious, people try and remove such thoughts from focal attention. (After all, ending up as fertilizer is a thought on which people generally don’t like to dwell.) Such proximal defenses push death-related thought to the mental background. It is when thoughts of death are active but outside of conscious awareness that people more strongly engage in distal defenses that address the problem of death on an abstract and symbolic level. For example, people cling more vigorously to their cultural beliefs (i.e., worldview defense) and try harder to live up to cultural standards (i.e., self-esteem striving). Proximal and distal defenses are often inferred in experimental research by measuring outcomes immediately after a mortality reminder, or after a delay, respectively. Conceptual and meta-analytic reviews (i.e., statistical approaches that average across different studies) support the unique time course of death thought activation and the distinct effects elicited (e.g., Steinman & Updegraff, 2015).

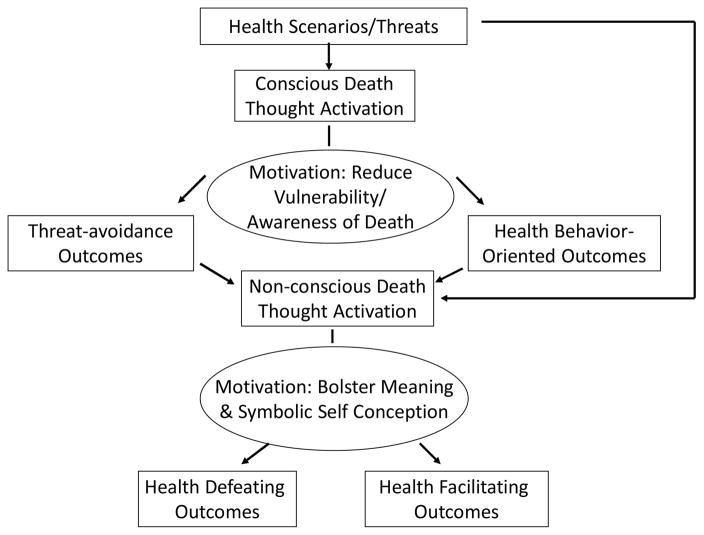

The TMHM (Figure 1) builds from these ideas. It begins with the assumption that health conditions have varying potential to make people think about death. The model then integrates insights about how people manage conscious and non-conscious death-related cognitions with the recognition that health decisions can be influenced by concerns central (or proximal) and more tangential (or distal) to the health context. The foundational idea is that when mortality concerns are conscious, health decisions are largely guided by the proximal motivational goal of reducing perceived vulnerability to a health threat and thus concerns about mortality. In contrast, when mortality cognition is active but outside of focal attention, health relevant decisions are guided by distal motivational goals concerning the symbolic value of the self.

Figure 1.

A Terror Management Health Model

TMHM RESEARCH

The Link between Health and Death

Every time people conduct routine cancer screenings there is the possibility that what they discover could mark the beginning of the end. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that over 60% of people in a population-level survey reported when they think of cancer they automatically think of death (Moser et al., 2014). Even presentations of the word “cancer” that participants report not having seen (i.e., subliminal priming) increase the cognitive availability of death-related thought (Arndt et al., 2007). Performing breast exams for women (Goldenberg et al., 2008), or reading about risks of smoking (Hansen et al., 2010) or unprotected sun exposure (Cooper et al., 2014), also make thoughts about death accessible. But cancer is just one of many health domains sharing this connection. Appeals about binge drinking (Jessop & Wade, 2008), risky-sex (Grover et al., 2010), even insurance advertisements (Fransen et al., 2008), also activate thoughts of death. Such findings prompt the critical question, how do cognitions about mortality influence health decision-making and behavior? Across domains such as tanning, smoking, cancer screening, nutrition, and fitness the answer often depends on whether thoughts of death are in conscious awareness or not.

The Proximal and Distal Health Implications of Mortality Salience

Routledge and colleague’s (2004) studies on sun protection provide an illustration of divergent health-relevant responses to conscious and non-conscious death-related thought. Women reported greater interest in sun protection immediately after answering two short questions about their mortality (vs. a control topic), presumably to reduce vulnerability to a health concern. However, after a delay, they indicated stronger interest in tanning, in line with appearance-based esteem contingencies assessed as part of the experiment.

McCabe et al.’s (2014) studies on product endorsement provide another illustration. One study featured an ostensible taste-test. Participants sampled a brand of bottled water purportedly endorsed by a medical doctor (to appeal to health) or a popular celebrity (to appeal to social status). Immediately after reminders of mortality, participants drank more when the water was endorsed by a medical doctor, whereas after a delay, they drank more of the celebrity-endorsed water. Such effects highlight the distinction in health and esteem motivations that follow from conscious and non-conscious thoughts of death.

Because people are motivated to reduce vulnerability to health concerns when consciously thinking about death, explicit thoughts of mortality render health-promoting (proximal) responses like exercising more, using sun-protection, and getting a screening exam more likely when people have sufficient coping resources, optimism, or beliefs in the efficacy of the behavior (and themselves) to effectively mitigate the health concern. When lacking these resources, people may respond to conscious thoughts of death by avoiding or denying the health threat (e.g., Cooper et al., 2010). Thus, the effect of conscious concerns about mortality on health decisions depends on factors of immediate relevance to the health context, much as has been found with rationally-oriented models of health behavior (e.g., Prentice-Dunn & Rogers, 1986).

In contrast, the relevance of the behavior for esteem and cultural identification often directs health decisions once thoughts of death are no longer conscious. For example, when distracted from mortality reminders, individuals who derive self-esteem from fitness increase exercise intentions (Arndt et al., 2003), whereas those who derive self-esteem from smoking report less interest in quitting (Hansen et al., 2010). These findings mesh well with evidence that self-esteem and self-presentational motives influence health decision-making (e.g., Leary et al., 1994; Mahler et al, 2007), but extend them by demonstrating the role of mortality concerns in these processes. The TMHM further suggests that worldview beliefs function similarly. Consider, for instance, those subscribing to a fundamentalist religious worldview. Terror management processes may play a role in their willingness to rely on faith alone for medical treatment (Vess et al., 2009). Taken together, this work helps to delineate when health decisions will be influenced by factors tangential to the health context, and why people sometimes do the seemingly irrational things they do when it comes to taking care of their health.

LEVERAGING THE TMHM TO IMPROVE HEALTH DECISIONS

The implications of the TMHM framework invite consideration of a number of different ways to improve health decision-making. Indeed, research has begun to examine how death-related cognition can be used as a motivational catalyst to facilitate health promotion and reduce health risk.

Augmenting Conventional Approaches to Health Cognitions

One direction uses conscious death-related thought to bolster the influence of conventional health cognition approaches. For example, Cooper et al. (2014) presented beachgoers with health communications that did or did not highlight the risk of death from skin cancer, and did or did not elaborate on the efficacy of sun-protection to mitigate these risks. When appeals enhanced sun protection efficacy and raised the conscious risk of mortality, sun protection intentions were greater. Such findings offer promise for using explicit mortality concerns to augment educational health campaigns that incorporate fear-related messages.

Notably, there are differing views about the potential of the TMHM to inform research on the use of persuasive fear messages (see Hunt & Shehyrar, 2011; Tannenbaum et al., 2015). When considering this potential, it is important to recognize appeals need not just explicitly mention death to conjure up death-related cognition; implicating serious health consequences can do so as well. Further, whether people are actively thinking about death is an important issue for evaluating whether the appeal encourages “health” or “esteem” based responses and necessitates careful attention. Fine grained measurement of this issue may be necessary, and is likely challenging in the context of much health communication research. But carefully considering the source of fear and the potential for health communications to activate conscious or non-conscious death-related thought may help to illuminate when and why such appeals are effective, when they fall flat, and when they backfire (Ruiter et al., 2014).

Targeting Malleable Bases of Cultural Value

The TMHM suggests that, when mortality concerns are active but not conscious, efforts to change health behavior may benefit from targeting malleable bases of cultural value. For example, when smokers viewed a public service announcement concerning the social consequences of smoking (e.g., “who wants to date someone with bad breath”), participants reminded of mortality had higher quit intentions than observed without mortality reminders (Arndt et al., 2009; also Wong et al., 2016). Conveying positive social norms can also be useful in this regard. Grocery store patrons were reminded of mortality or a control topic, and then visualized exemplars of healthy eaters (i.e., prototypes; Gibbons & Gerrard, 1995) or not. As determined from their shopping receipt, those primed with mortality and healthy eaters purchased healthier foods (McCabe et al., 2015).

The utility of targeting how individuals derive a sense of value in conjunction with mortality reminders also shows promise with safe sun behavior. The guiding idea is that if people can be steered away from thinking of tan skin as attractive, subtle primes of mortality might lead to more interest in sun protection. Using such an approach, Cox et al. (2009) observed requests for sunscreen samples with higher SPF among (Caucasion) beachgoers. Furthermore, framing a UV photograph of participants’ faces as revealing damaging effects on appearance, rather than health, interacted with mortality reminders to lead participants to take more sunscreen samples and report greater intentions to use it (Morris et al., 2014). Thus, there seems to be potential for non-conscious thoughts of mortality to engage healthier behavioral practices if aspects of social value are targeted.

Recognizing the Body Problem

The TMHM also fosters recognition of underappreciated barriers toward promoting health behavior. Goldenberg and colleagues (2000) suggest that the physicality of the body undermines people’s capacity to maintain the symbolic, cultural value of the self as a means to manage concerns associated with mortality. This helps inform when and why people may avoid health behaviors that involve intimate confrontation with the body’s physicality, or creatureliness (e.g., breast self-exams and mammograms, Goldenberg et al., 2008). That these behaviors are not only threatening because of the health implications (i.e., what one might find) but also because of a non-health-related threat suggests that, as with other distal defenses, efforts to foster health behavior may benefit from highlighting the symbolic aspects of the self. Opportunities to affirm symbolic representations of the body may be effective when health contexts elicit both mortality concerns and discomfort with the body’s physicality (Morris et al., 2012).

The Potential for Behavioral Durability

An important question is whether the effects observed in TMHM research are just a brief blip on the behavioral change radar. Concerns about inevitable mortality are an ever-present condition with which people must contend, and moreover, people are reminded of mortality—sometimes blatantly and sometimes subtly—on a routine basis. Two recent studies provide initial insight as to how an enduring influence of awareness of death may affect health behavior as it unfolds over time.

In Morris et al. (2016), when participants were primed with mortality and rode an exercise bike they later reported exercising more in the two weeks that followed than participants not reminded of mortality, and this led them to report basing their self-esteem more on fitness. In a second study, smokers who visualized a prototypical unhealthy smoker after being reminded of mortality reported more attempts to quit smoking in the following three weeks, became more committed to an identity as a non-smoker, and this in turn inspired continued attempts over the next three weeks. These studies lay the groundwork for a longitudinal model in which death-related thought encourages identity-relevant behavior, the behavior fosters more identity-relevance, and this in turn promotes more of the (healthy) behavior.

Becoming Comfortably Numb

Research is also examining other processes through which death-related cognition might influence health-relevant choices. For example, perhaps because of the potential for anxiety involved, death reminders can motivate people to become “comfortably numb” (to borrow from a colleague who borrowed from Pink Floyd) and increase interest in intoxicants like marijuana (Nagar et al., 2015), and alcohol purchasing behavior (Ein-Dor et al., 2013). Such risky behavior may be most likely for those who lack secure terror management buffers. Indeed, night club patrons with low self-esteem drank more alcohol (as indicated by breathalyzer analysis) when primed with mortality reminders (Wisman et al., 2016).

CONCLUSION

The TMHM integrates research on existential motivation, self-threats and psychological defense, risky behavior, fear appeals, and vulnerability, esteem, and normative factors influencing health decision-making. Like other applied theoretical research, the TMHM enriches understanding of the target domain as well as the basic theory. Although additional research is needed on the directions outlined above, the model offers a foundation for understanding how people manage existential insecurity as well as harnessing the effects of death-related thought to engage productive health behavior change.

Acknowledgments

Most of the research reviewed here that involves Jamie Arndt and Jamie Goldenberg was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute R01CA096581.

Footnotes

Recommended Readings

Goldenberg, J.L., & Arndt, J. (2008). (see references).

- A theoretical review paper introducing the terror management health model

Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & Greenberg, J. (2015). (see references).

- A recent comprehensive review of terror management theory research for those interested in the different directions of research inspired by the theory

Spina, M., Arndt, J., Boyd, P., & Goldenberg, J.L. (2016). Bridging health and death: Insights and questions from a terror management health model. In L.A. Harvell & G.S. Nisbett (Eds.), Denying death: An interdisciplinary approach to Terror Management Theory (pp.47–61). New York: Routledge.

- A recent review of terror management health model research

Contributor Information

Jamie Arndt, University of Missouri.

Jamie L. Goldenberg, University of South Florida

References

- Arndt J, Schimel J, Goldenberg JL. Death can be good for your health: Fitness intentions as proximal and distal defense against mortality salience. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:1726–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt J, Cook A, Goldenberg JL, Cox CR. Cancer and the threat of death: The cognitive dynamics of death thought suppression and its impact on behavioral health intentions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:12–29. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt J, Cox CR, Goldenberg JL, Vess M, Routledge C, Cohen F. Blowing in the (social) wind: Implications of extrinsic esteem contingencies for terror management and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:1191–1205. doi: 10.1037/a0015182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker E. The Denial of Death. NewYork: The FreePress; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DP, Goldenberg JL, Arndt J. Examination of the terror management health model: The interactive effect of conscious death thought and health-coping variables on decisions in potentially fatal health domains. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:937–946. doi: 10.1177/0146167210370694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DP, Goldenberg JL, Arndt J. Perceived efficacy, conscious fear of death, and intentions to tan: Not all fear appeals are created equal. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2014;19:1–15. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CR, Cooper DP, Vess M, Arndt J, Goldenberg JL, Routledge C. Bronze is beautiful but pale can be pretty: The effects of appearance standards and mortality salience on sun-tanning outcomes. Health Psychology. 2009;28:746–752. doi: 10.1037/a0016388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ein-Dor T, Hirschberger G, Perry A, Levin N, Cohen R, Horesh H, Rothschild E. Implicit death primes increase alcohol consumption. Health Psychology. 2014;33(7):748–751. doi: 10.1037/a0033880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransen ML, Fennis BM, Pruyn ATH, Das E. Rest in peace? Brand-induced mortality salience and consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research. 2008;61:1053–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Predicting young adults’ health risk behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(3):505–517. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg JL, Arndt J. The implications of death for health: A terror management health model for behavioral health promotion. Psychological Review. 2008;115:1032–1053. doi: 10.1037/a0013326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg JL, Arndt J, Hart J, Routledge C. Uncovering an existential barrier to breast cancer screening. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:260–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg JL, McCoy SK, Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J, Solomon S. The body as a source of self-esteem: The effect of mortality salience on identification with one’s body, interest in sex, and appearance monitoring. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:118–130. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S. Public Self and Private Self. Springer; New York: 1986. The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory; pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Grover KW, Miller CT, Solomon S, Webster RJ, Saucier DA. Mortality salience and perceptions of people with AIDS: Understanding the role of prejudice. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2010;32:315–327. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J, Winzeler S, Topolinski S. When the death makes you smoke: A terror management perspective on the effectiveness of cigarette on-pack warnings. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46(1):226–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt DM, Shehryar O. Integrating terror management theory into fear appeal research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5(6):372–382. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop DC, Wade J. Fear appeals and binge drinking: A terror management theory perspective. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13:773–788. doi: 10.1348/135910707X272790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist. 2009;64(4):241–256. doi: 10.1037/a0015309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Tchividijian LR, Kraxberger BE. Self-presentation can be hazardous to your health: impression management and health risk. Health Psychology. 1994;13(6):461–470. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.6.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Harrell J. Effects of appearance-based intervention on sun protection intentions and self-reported behaviors. Health Psychology. 2003;22(2):199–209. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S, Arndt J, Goldenberg JL, Vess M, Vail KE, III, Gibbons FX, Rogers R. The effect of visualizing healthy eaters and mortality reminders on nutritious grocery purchases: An integrative terror management and prototype willingness analysis. Health Psychology. 2015;34:279–282. doi: 10.1037/hea0000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S, Vail KE, III, Arndt J, Goldenberg JL. Hails from the crypt: A terror management health model investigation of health and celebrity endorsements. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2014;40:289–300. doi: 10.1177/0146167213510745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris KL, Cooper DP, Goldenberg JL, Arndt J, Gibbons FX. Improving the efficacy of appearance-based sun exposure intervention with the terror management health model. Psychology and Health. 2014;29:1245–1264. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.922184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris KL, Cooper DP, Goldenberg JL, Arndt J, Routledge C. Objectification as self-affirmation in the context of a death-relevant health threat. Self and Identity. 2013;12:610–620. [Google Scholar]

- Morris KL, Goldenberg JL, Arndt J, McCabe S. The enduring influence of death on health: Insight from the terror management health model. 2016 Manuscript in Preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Moser RP, Arndt J, Han P, Waters E, Amsellem M, Hesse B. Perceptions of cancer as a death sentence: Prevalence and consequences. Journal of Health Psychology. 2014;19:1518–1524. doi: 10.1177/1359105313494924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagar M, Rabinovitz S. Smoke your troubles away: exploring the effects of death cognitions on cannabis craving and consumption. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(2):91–99. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2015.1029654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW. Protection motivation theory and preventive health: Beyond the health belief model. Health education research. 1986;1(3):153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T, Solomon S, Greenberg J. Thirty Years of Terror Management Theory: From Genesis to Revelation. Advances in experimental social psychology. 2015;52:1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Routledge C, Arndt J, Goldenberg JL. A time to tan: Proximal and distal effects of mortality salience on sun exposure intentions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1347–1358. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiter RA, Kessels LT, Peters GJY, Kok G. Sixty years of fear appeal research: Current state of the evidence. International journal of psychology. 2014;49(2):63–70. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman CT, Updegraff JA. Delay and Death-Thought Accessibility A Meta-Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2015;41:1682–1696. doi: 10.1177/0146167215607843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum MB, Hepler J, Zimmerman RS, Saul L, Jacobs S, Wilson K, Albarracín D. Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychological bulletin. 2015;141(6):1178–1204. doi: 10.1037/a0039729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vess M, Arndt J, Cox CR, Routledge C, Goldenberg JL. Exploring the existential function of religion: The effect of religious fundamentalism and mortality salience on faith-based medical refusals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:334. doi: 10.1037/a0015545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisman A, Heflick N, Goldenberg JL. The great escape: The role of self-esteem and self-related cognition in terror management. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2015;60:121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wong NCH, Nisbett GS, Harvell LA. Smoking is so ew!: College smokers reactions to health- versus social-focused anti-smoking threat messages. Health Communication. 2016 doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1140264. (advance online publication; http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10410236.2016.1140264) [DOI] [PubMed]