Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, allergic disease associated with marked mucosal eosinophil accumulation. EoE disease risk is multifactorial and includes environmental and genetic factors. This review will focus on the contribution of genetic variation to EoE risk, as well as the experimental tools and statistical methodology used to identify EoE risk loci. Specific disease-risk loci that are shared between EoE and other allergic diseases (TSLP, LRRC32) or unique to EoE (CAPN14), as well as Mendellian Disorders associated with EoE, will be reviewed in the context of the insight that they provide into the molecular pathoetiology of EoE. We will also discuss the clinical opportunities that genetic analyses provide in the form of decision support tools, molecular diagnostics, and novel therapeutic approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic, allergic disease associated with marked mucosal eosinophil accumulation.1 Though the presenting symptoms vary with age, EoE persists from childhood into adulthood.1,2 Among other chronic pediatric diseases, EoE has one of the lowest qualities of life.3 The substantial morbidity is likely due, at least in part, to the effects of the severely restricted diets (as part of therapy), the chronic pain, and the frequent need for recurrent invasive interventions (endoscopies), which require general anesthesia in children.3 Removal of specific food types can lead to EoE remission, but food reintroduction can cause disease recurrence as measured by eosinophil accumulation and marked dysregulation of esophageal gene products at the transcript and protein level.

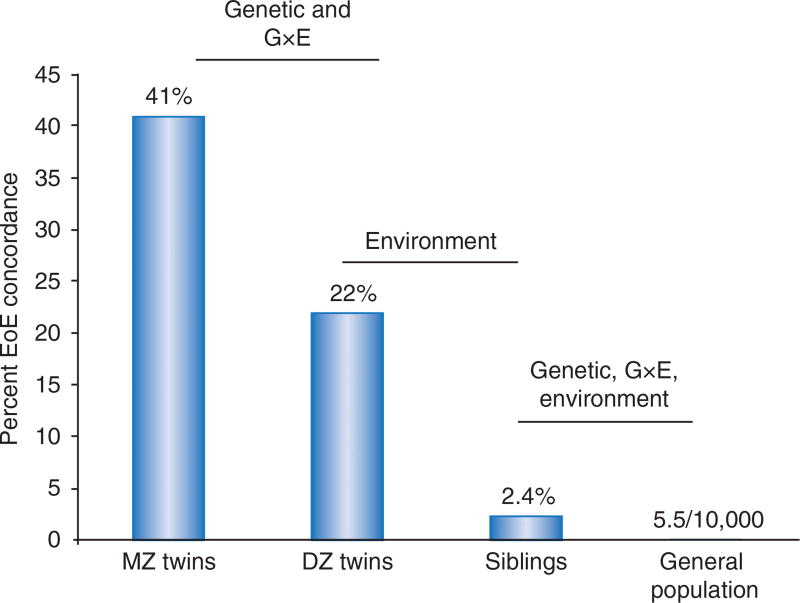

One of the central goals in the allergy field is to understand why individuals develop certain tissue-specific manifestations, such as EoE. The etiology of EoE includes environmental, immunologic, and genetic components.4–6 In order to determine the magnitude of environmental and genetic factors for EoE disease risk, our group has used a classic epidemiologic approach of assessing disease concordance among nonrelated individuals, siblings, dizygotic twins, and monozygotic twins4 (Figure 1). Dizygotic twins have a 22% disease concordance, whereas 2.4% of siblings of patients with EoE have EoE and the general risk of EoE is about (1/2,000) in the overall population. Because dizygotic twins and siblings have the same genetic relatedness, we were able to use this difference to determine that environmental factors contribute 81% towards the phenotypic variance. Similarly, monozygotic twins share 100% of their genetic identity yet have only 41% disease concordance. The EoE disease concordance differences between monozygotic and dizygotic twins revealed a contribution of genetic risk variants that accounts for 15% of the phenotypic variation of disease risk.4

Figure 1.

Concordance of disease in siblings supports role of genetic and environmental etiologic factors for EoE risk. DZ, dizygotic; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; G × E, gene-by-environment; MZ, monozygotic. (From ref. 4.)

Immunologically, Th2-associated signaling pathways (especially those involving interleukin 4 (IL-4)/IL-13 signaling) are critical for the initiation and pathoetiology of EoE. During active disease in humans, IL-13 is induced 16-fold in the esophagi and can induce a well-defined set of EoE-involved transcripts in esophageal cells ex vivo.7 In mice, IL-13 overexpression is sufficient to induce esophageal eosinophilia and other structural esophageal changes, resembling EoE.8,9 Allergic sensitization and exposure is sufficient to generate EoE-like features in mice; notably, intact IL-13 signaling is necessary for allergen-induced esophageal eosinophilia and related esophageal remodeling.10 The reduced integrity of the epithelial cell barrier is a critical cellular mechanism associated with EoE. Eosinophil infiltration into the lamina propria, basal zone and intraepithelial spaces in the esophagus are pathognomonic for EoE;11 however, apart from the IL-5 and IL-13 secretion by activated effector CD4+ T cells (defined by expression of chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on T(H)2 cells-positive (CRTH2(+)), hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase, and CD161,12 the role of eosinophils and other specific immune cells (e.g., mast cells, T regulatory cells, and natural killer cells) in mediating EoE are not clearly defined.13–15

Taken together, the evidence support that EoE disease risk is multifactorial and involves the complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, particularly early life exposure events such as those that are likely to affect microbiome content and diversity.4,16,17 Indeed, the esophagus has its own unique microbiome that is likely different between homeostatis and EoE, and there is emerging evidence that diet can affect intestinal microbiome.16,17 Previous reviews detail the environmental etiology, the clinical presentation and manifestations, and critical molecular pathways of EoE.13,14,18–25 This review will focus on the contribution of genetic variation on EoE risk. Specific EoE-risk loci will be reviewed in the context of what insight they provide into the molecular pathoetiology of EoE. We will highlight the opportunities provided by families with multiplex patterns of EoE inheritance and of single-gene Mendelian disorders that are enriched with patients who also have EoE. We will also discuss the clinical opportunities that genetic analyses provide in the form of decision support tools, molecular diagnostics, and novel therapeutic approaches.

ASSESSING GENETIC VARIATION AND IDENTIFYING EoE-RISK LOCI

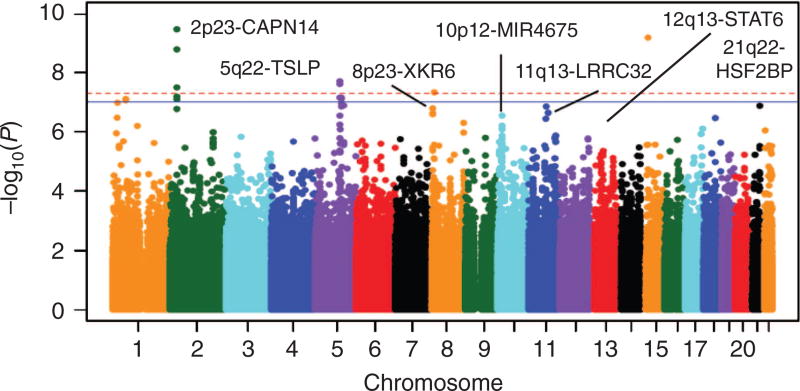

Figure 2 is the Manhattan plot of a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of EoE.5 The variants that are most statistically associated with EoE risk are those with the lowest P-values (and graphed at the top of the figure). Because GWAS involves assessing many different genetic variants in the same case and control populations, the results are a normal distribution of chi-squared statistics and a complementary distribution of P-values. Though an α-error of 0.05 is appropriate for many experimental studies, a multiple testing correction must be applied to account for the million independent sections of the human genome (Pcorrected = 0.05/106).26 The red-dashed line in the Manhattan plot designates “genome-wide significance”—a P-value of 5 × 10−8. For genetic variants that are associated at P-values less than 5 × 10−8, the null hypothesis can be rejected, and the genetic variant can be designated as an EoE-risk variant. Notably, over 90% of genetic variants associated with allergic and immunologic diseases such as EoE are in noncoding regions.5,27–33 Therefore, it is often challenging to identify the molecular mechanisms driving disease risk. Indeed, ascertaining causality in noncoding variants is non-trivial and can be dependent on specific cell types and the presence of specific inflammatory signaling pathways.34

Figure 2.

Results of a genome-wide association study of EoE. Data from 736 subjects with EoE and 9,246 controls over 1,468,075 common genetic variants are graphed in a Manhattan plot. The −log10 P-value of each probability is shown as a function of genomic position on the autosomes. Genome-wide significance (red dashed line; P = 5 × 10−8) and suggestive significance (solid blue line; P = 1 × 10−7) are indicated. CAPN14, Calpain-14; HSF2BP, Heat Shock Transcription Factor 2 Binding Protein; LRRC32, Leucine Rich Repeat Containing 32; MIR4675, microRNA 4675; TSLP, Thymic stromal lymphopoietin; XKR6, XK Related 6. (From ref. 5.)

EoE-RISK LOCI

Both candidate and genome-wide approaches have been used to identify specific genetic loci that increase risk of EoE.13,35 Candidate analyses identified genetic variants at CCL26, FLG, CRLF2, and DSG1 with increased risk of EoE.36–39 GWAS approaches have identified and replicated association of genetic variants at loci encoding TSLP/WDR36, CAPN14, LRRC32/C11orf30, STAT6, and ANKRD27 with EoE risk.32,33,40 Table 1 lists each of the established EoE-risk loci in the context of the encoded gene’s effect sizes and whether the data have been subjected to replication. In a phenotype association study (PheWAS), a set of candidate or genome-wide genetic variants for EoE were assessed for risk of a range of phenotypes, identified from electronic medical records and ICD9 codes. This analysis identified PTEN, TGFBR1/TGFBR2/PBN, and IL5/IL13 as additional EoE-risk loci.41 Many of these EoE-risk loci are also associated with allergic sensitization, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and asthma. A substantial proportion of patients with EoE also have a history of allergic disease, including asthma (~50%), allergic rhinitis (~60%), and atopic dermatitis (40%). This comorbidity of EoE with other allergic diseases does not necessarily mean that the risk loci shared between EoE and other allergic disease are nonspecific; these risk loci may be specific to the esophageal allergic manifestations of EoE. In order to determine whether EoE-risk loci were associated with EoE independently of other atopic diseases, a logistic regression strategy was used in each of the published EoE GWAS. Critically, logistic regression analysis at the 5q22, 11q13, and 12q13 loci, which adjusted for the sensitization status, indicated that the observed association of these loci with EoE was independent of sensitization. These analyses demonstrate an important specific role for these risk loci for EoE as opposed to a nonspecific role for allergic disease.32,42

Table 1.

Statistically significant and replicated EoE genetic risk loci

| EoE genetic risk loci |

Genes encoded |

Odds ratio for most associated SNP at each locus |

Putative genetic mechanism | Pathogenic mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2p23 | CAPN14 | 1.98 | Promoter variant leads to genotype-dependent expression of CAPN14, likely involving epigenetic mechanism | CAPN14 is a regulatory enzyme that is induced by IL-13 and involved in epithelial homeostasis and repair |

| 5q22 | TSLP WDR36 | 0.74 | Multiple risk alleles associated with genotype-dependent expression of TSLP | TSLP induces Th2 cell development and activates eosinophils and basophils |

| 11q13 | LRRC32 C11orf30 | 2.49 | Not described | LRRC32 is a TGF-β binding protein |

| 12q13 | STAT6 | 1.50 | Not described; STAT6 is the primary mediator of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling | STAT6 is a downstream signaling mediator of IL-4Rα |

| 19q13 | ANKRD27 PDCD5 RGS9BP | 1.60 | Not described | ANKRD27 inhibits the SNARE complex; PDCD5 is involved in apoptotic pathways. RGS9BP is not expressed in the esophagus or by immune cells |

Abbreviations: EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Each person can have 0, 1, or 2 risk alleles. In an additive model, EoE risk is a sum of the risk for each risk allele. Risk shown is >1 and hence adjusted for being a common or rare allele.

Established EoE-risk loci associated with other allergic phenotypes

5q22 encodes TSLP and WDR36. TSLP has wide-ranging affects on many different cell types, including epithelial and hematopoietic cells. TSLP plays a critical role in promoting the classical “Th2” responses that drive allergic inflammation. TSLP is overexpressed in the esophagus of patients with active EoE.33,39 Importantly, the EoE-risk alleles are associated with increased TSLP expression.9,33,39 In mouse models of EoE, TSLP secreted from the epithelium is thought to contribute to recruiting basophils. Importantly, depletion of basophils and therapeutic TSLP neutralization is sufficient to resolve established EoE-like disease in mice.43 There is a similar correlation between TSLP expression and basophil accumulation in the esophagi of patients with EoE, and a TSLP genetic variant (identified in the original EoE GWAS33) that results in increased TSLP expression correlates with increased basophil numbers.43 Therapeutic strategies aimed at reversing the dysregulation of TSLP are particularly promising for EoE and other allergic diseases.43–45

11q13 encodes LRRC32 (also known as GARP) and C11orf30 (also known as EMSY).5,32 LRRC32 has a role in latent surface expression of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), and LRRC32 mRNA is highly expressed in activated forkhead box P3 (FOXP3)+ T regulatory cells.46–48 C11orf30 encodes EMSY, which suppresses the transactivation activity of BRCA2.49 EMSY is part of a histone H3-specific methyltransferase complex and may mediate ligand-dependent transcriptional activation by nuclear hormone receptors.49–51 Both EMSY and LRRC32 are expressed in esophageal epithelial cells, and the roles of these genes in EoE are yet to be reported.

12q13 encodes STAT6. STAT6 is a transcription factor that is activated by the allergy-associated cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 and possibly IL-33.52–56 Esophageal epithelial cell lines have intact STAT6 signaling,57–59 and STAT6 drives the expression of many of the genes in the EoE transcriptome.7,58,60 Indeed, STAT6 had a critical and established role in the pathophysiology of EoE before its identification as an EoE-risk locus.32 Inhibitors upstream of STAT6 are being actively pursued, and a confluence of genetic, transcriptional and physiologic evidence supports their potential in treating patients with EoE.61 Examples include dupilibumab (a human monoclonal antibody against the common IL-4 and IL-13 receptor, IL-4Rα), which is in phase-3 clinical trials,62,63 and two inhibitors of IL-13 (humanized anti-IL-13), which are in phase-2 trials.64

EoE-risk loci that are tissue specific

2p23 encodes CAPN14. Calpain 14 belongs to the classical calpain subfamily, a set of calcium-activated intracellular regulatory proteases.42,65 When the 2p23 risk locus was first identified, no published studies assessed calpain 14 expression or function. The GWAS identified this locus and resulted in new and exciting opportunities for understanding EoE pathoetiology and finding novel therapeutic targets. Indeed, calpain 14 expression is relatively limited to the esophagus. CAPN14 is dynamically upregulated as a function of EoE disease activity and after exposure of esophageal epithelial cells to IL-13.66 Calpain 14 overexpression is sufficient to induce EoE-associated morphologic changes in esophageal epithelial cells and has been identified as a regulator of desmoglien 1 (DSG1), an intercellular junctional protein key for barrier formation.67 A regulatory role for calpain 14 in both disease induction and repair has begun to emerge, as there is a proinflammatory effect of both gene silencing and overexpression of CAPN14.67 These data support a model of calpain 14 as being central to EoE and part of a critical feedback loop in the context of IL-13 signaling. Indeed, molecular analysis demonstrates that EoE risk variants at this locus are associated with genotype-dependent expression of calpain 14 in the esophageal biopsies of patients with active EoE.42

19q13 encodes several genes including ANKRD27, PDCD5, and RGS9BP. ANKRD27 (also known as VARP) regulates the trafficking of enzymes involved in melanin processing to the epidermal melanocytes.68,69 ANKRD27 also inhibits the SNARE complex, which could have important implications for apical transport in esophageal epithelial cells and wound healing.70,71 PDCD5 is upregulated during apoptosis, translocating to the nucleus from the cytoplasm.72,73 The encoded protein is hypothesized to be an important regulator of lysine acetyltransferase 5 by inhibiting its proteasome-dependent degradation.73 PDCD5 is implicated in transcriptional regulation, DNA damage response, and cell cycle control.72 RGS9BP encodes a gene product whose expression is limited to the retina, limiting the potential of this gene to be relevant in EoE.74,75 Like other EoE-risk loci, the EoE-risk variants at this locus are noncoding and likely affect gene expression of one or more of the nearby genes by direct effects or by modulation of chromatin structure. Further molecular studies are required to identify the expression of surrounding genes in the esophagus of patients in the context of disease and genotype.

EoE is associated with celiac disease but not the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genetic locus

Celiac disease is linked with EoE;76–80 in fact, a diagnosis of celiac disease increases risk for EoE by at least 25%.78 EoE and celiac disease share common features including that both are food antigen-driven, although there is limited evidence that gluten is a causal food in EoE,81 both involve a pathophysiology that places epithelial cells in the center stage, and both resolve upon removal of causal foods. Unlike celiac disease, there is no evidence that EoE is auto-immune in nature. Celiac disease affects the small intestine through gluten-specific T cells, autoantibodies against tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and tTG-induced neo-antigens. In one study of adult patients with both EoE and celiac disease, a gluten-free diet resolved patients’ esophageal eosinophilia, which raises the possibility of shared pathophysiology in those subjects.76 In another study, gluten removal successfully treated the celiac component but not the EoE component of patients with concurrent disease.78 Altogether, additional studies are required to elucidate the pathoetiological and genetic links between EoE and celiac disease. Over 95% of patients with celiac disease have the HLA-DQ2 allele, and the remaining patients have the HLA-DQ8 allele. Though these specific class-2 human leukocyte antigen genotypes are necessary for celiac disease, they are not sufficient. Over 45 common genetic risk loci apart from the human leukocyte antigen locus on chromosome 6 have been statistically associated with celiac disease risk. Most of the celiac disease-risk loci are shared with other autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis. Unlike celiac disease and the other autoimmune diseases, no human leukocyte antigen association has been identified as increasing disease risk for EoE. Indeed, to date, no common genetic mechanisms linking EoE and celiac disease or any other autoimmune disease have been identified, although increasing evidence for clinical co-occurrence is emerging.82

Families with multiplex inheritance of EoE

Though the majority of patients with EoE do not have parents or siblings with EoE, there are some families in which EoE is inherited in a manner that implicates single, extremely rare genetic mutations. Indeed, the literature contains over 50 examples of these multiplex families in which numerous affected members have pathologically confirmed EoE.4,83 Often, these multiplex families also contain other family members with clinical histories suggesting the presence of EoE (e.g., an uncle with a history of dysphagia without follow-up pathology of his symptoms). Patients within these families had pathologic, clinical, and esophageal gene expression findings consistent with patients with EoE.83 Genetic studies on multiplex EoE families may be complicated by the presence of family members with variable EoE phenotypes, including an EoE-like esophagitis that is devoid of eosinophilia, suggesting partial penetrance of different disease features.84 Nonetheless, these families provide a unique opportunity to identify rare genetic variants and mutations in pathways so important to the etiology of EoE that the variants are not commonly found in the population. Even in cases in which the mutation is only carried by a small proportion of subjects with EoE, therapeutics targeting these pathways might well be effective for a much larger group of patients.

The sequencing of the entire genomes or exomes of these family members with and without disease could lead to significant breakthroughs of monogenetic causes of EoE. Using another approach, a whole-exome sequencing study of 33 unrelated patients with EoE identified esophageal genes with an increased burden of rare, damaging mutations. Strikingly 39 rare genetic variants in 18 genes were identified in this study, and this preliminary analysis indicates enrichment in gene in epithelial differentiation.85

Mendelian diseases associated with EoE

EoE co-occurs with several Mendelian and non-Mendelian disorders (Table 2 and refs 85,86). For example, EoE is enriched in patients with hypermobility-associated connective-tissue disorders including Loeys-Dietz syndrome (also known as Marfan syndrome type II)88 and the hypermobility variant of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.13 Indeed, a diagnosis of EoE increases risk for connective-tissue disease by eightfold.13 Mechanistically, there is enhanced TGF-β production and signaling in both EoE and connective-tissue disease. Genetic mutations that result in single amino acid changes in proteins that bind TGF-β-related proteins have been shown to cause Loeys-Dietz syndrome,88 whereas Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is caused by genetic mutation in collagen-encoding genes.89,90 Notably, TGF-β has been shown to directly regulate the transcription of collagen,91,92 and EoE is associated with both increased production of TGF-β and dysregulated expression of collagen in the esophagus, especially in patients with the connective-tissue disease variant.93,94

Table 2.

Mendelian diseases associated with EoE

| Mendelian disease associated with EoE |

Genetic mutation | Plausible etiologic mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Loeys-Dietz syndrome (LDS) | Mutations in transforming growth factor beta receptors 1 and 2 (TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, respectively) | Enhanced transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type | Unknown—other subtypes of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome are caused by mutations in collagen genes | Disrupted joint and skin development; increased activity of TGF-β due to altered binding by extracellular matrix |

| Severe atopy syndrome associated with metabolic wasting (SAM syndrome) | Homozygous mutations in desmoglein 1 (DSG1) | Disrupted epithelial barrier |

| Netherton’s syndrome | Loss-of-function mutations in skin protease inhibitor, kazal type 5 (SPINK5) | Unrestricted protease activity of kallikrein 5 and 7 (KLK5, KLK7) |

| PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) | Mutations in phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) | Inhibited regulation of the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway |

| Autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome | Deleterious mutations in signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) | Dysregulated response to IL-6 and possibly IL-5 |

| Autosomal recessive form of hyper-IgE syndrome | Loss-of-function mutations in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) | Loss of T-cell homeostasis; lack of durable secondary antibody response against specific antigens |

Homozygous mutations in epithelial adhesion molecule desmoglein 1 (DSG1) causes a severe atopy syndrome associated with metabolic wasting (SAM syndrome) and is indeed associated with EoE.95 Interestingly, DSG1 expression is downregulated in the esophageal epithelia of patients with active EoE (with and without SAM syndrome), and IL-13 treatment of esophageal epithelial cells decreases DSG1 expression.96 In vivo and ex vivo approaches demonstrated that disrupted DSG1 expression has a critical role in the epithelial barrier defects seen in EoE.96 Thus, these human experiments of nature prove that loss of DSG1 is causal of EoE, at least in some patients.

EoE is enriched in patients with Netherton’s syndrome, a disease caused by loss-of-function mutations in the skin protease inhibitor SPINK5 gene.97 Netherton’s syndrome is characterized clinically by the triad of atopic diathesis, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, and a specific hair shaft abnormality termed trichorrhexis invaginata ("bamboo hair").98 SPINK5 is an important regulator of the epidermal proteases kallikrein-related peptidase KLK5 and KLK7. Without SPINK5, the unrestricted KLK protease activity is sufficient to cause substantial disruption of the skin.99 The severe hyperatopy phenotype seen in Netherton’s syndrome, now linked with EoE, highlights the central role that barrier impairment has in EoE.

The PTEN (phosphatase and tensin) hamartoma tumor syndrome is also associated with eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders including EoE.100 PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome is caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor PTEN homolog. PTEN is a critical regulator of the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase signaling pathway through PTEN’s lipid and protein phosphatase activities.101 Unlike the other Mendelian diseases associated with EoE, it is notable that eosinophils express PTEN, which is involved in cytokine signaling, including IL-5 responses.

Autosomal-dominant hyper-IgE syndrome is also associated with EoE and is caused by deleterious mutations in signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Patients develop elevated IgE, staphylococcal abscesses, and pneumonia and markedly higher peripheral eosinophilia.102 STAT3 has a central role in the signaling pathway of growth factors, hormones and multiple cytokines. In the absence of functional STAT3, cells have a dysregulated response to IL-6, leading to a deficit in T-helper 17 cells, central T cell memory and memory B cells.103–105 Though the role of eosinophils in hyper-IgE syndrome is unknown, STAT3 is activated in eosinophils following IL-5 signaling, and a gain-of-function mutation has been identified in lymphocytic hypereosinophilic syndrome.106,107

An autosomal recessive form of hyper-IgE syndrome associated with EoE is caused by loss-of-function mutations in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8).107 These patients have elevated IgE, recurrent infections, severe atopic dermatitis, asthma, food allergy and eosinophilia.108 DOCK8 function is important for T-cell homeostasis, and mouse models have confirmed the necessity of DOCK8 in generating a durable secondary antibody response.109 DOCK8 acts through CDC42 and p21-activated kinase (PAK) to maintain morphologic shape and nuclear integrity in T and natural killer cells during chemotaxis.110DOCK8 is expressed on human eosinophils and putatively plays an important role in their chemotaxis and homeostasis.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS IN GENETIC ANALYSIS OF EoE

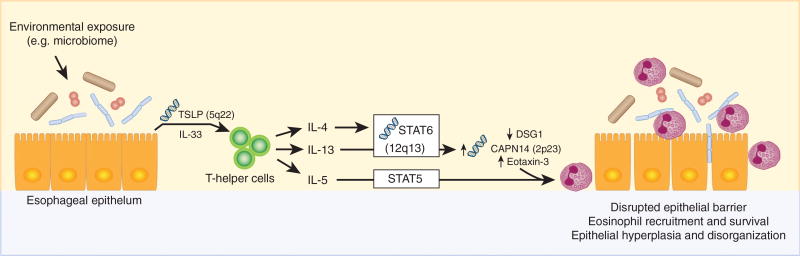

Identifying and replicating EoE-risk loci requires studies with sufficient statistical power to reach the low P-values resulting from the multiple testing correction of genome-wide studies. To date, genome-wide studies of EoE have been moderately powered, but they can be improved by including more independent cohorts of subjects with and without EoE. The next phase of genetic studies needs to not only identify loci but also identify molecular mechanisms driving the genetic associations. Causal variant statistical analysis and genotype-dependent transcriptional analysis are needed to identify candidate mechanisms that can be further tested using genome-edited, patient-derived esophageal culture systems. The EoE-risk loci contain genes with known roles in the pathoetiology of EoE (Figure 3); careful mechanistic studies are important because they will reveal specific molecular pathways that increase disease risk in patients with EoE. Given the important role of early life exposure events as EoE-risk factors,111 a deeper analysis of the microbiome and its interaction with EoE-risk variants is likely to be informative.

Figure 3.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)-risk loci contain genes with known roles in the pathoetiology of EoE. Esophageal epithelial cells secrete thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP, encoded by EoE-risk locus 5q22) and interleukin-33 (IL-33) in response to stimuli from various environmental factors. These cytokines act on T-helper cells, leading to their secretion of allergic cytokines including IL-13, IL-4, and IL-5. IL-5 signals primarily through signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) in eosinophils to promote tissue recruitment and survival. IL-13 signals primarily through signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6, encoded by EoE-risk locus 12q13) and promotes the transcription of calpain-14 (CAPN14, encoded by EoE-risk locus 2p23) and C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 26 (CCL26, also known as eotaxin-3). STAT6-dependent IL-13 signaling also leads to decreased expression of the tight junction protein desmoglein 1 (DSG1). Altogether, these signaling pathways lead to eosinophil recruitment and survival, a disrupted esophageal epithelial barrier, and a disorganized esophageal epithelium.

Moving beyond etiologic, genetic loci that increase risk for disease initiation, these same data sets can be used to perform subphenotypic studies that will identify genetic loci that increase risk for specific disease manifestations. Similarly, pharmacogenomic studies of patients with EoE who are responsive and unresponsive to specific therapeutic strategies (such as swallowed glucocorticoids) are possible with sufficient clinical data associated with the genome-wide genotyping data. Early proof-of-principle examples of this type of test are the correlation of a genetic variant in the TGF-β promoter with responsiveness to swallowed budesonide therapy in a small study of patients with EoE38 and the preliminary identification of a set of esophageal transcripts that predict responsiveness to topical fluticasone.112

Genetic analyses might also help to explain the male predominance of patients with EoE. Around 65% of patients are males.1,113–115 Environmental factors, physiologic differences between males and females, and genetic risk loci on the non-autosomal chromosomes are candidate hypotheses to explain the male predominance, but no definitive studies have explained the sex bias of EoE. Sex-specific genetic analyses of autosomal genetic variation did not reveal risk loci that were statistically significant in a sex-specific manner after applying a genome-wide, multiple-testing correction.5

CLINICAL POTENTIAL OF GENETIC STUDIES OF EoE RISK

The current clinical diagnosis of EoE depends upon careful analysis by trained, often specialized pathologists. The progress presented in the newly available EoE Diagnostic Panel (EDP) allows a clinician to extract RNA from an esophageal biopsy and make a diagnosis on the basis of the expression of a carefully selected set of genes; see www.eogenius.com for details.1,116–118 The EDP was recently assessed in a prospective cohort study, which confirmed the utility and sensitivity of this assay regardless of biopsy location or sample preservative and that it performs well even with only one biopsy.119 Similarly, the EDP facilitates disease characterization in addition to diagnosis. For example, transcriptional signatures from the EDP and other genes can be used to predict the response to particular therapeutics such as swallowed glucocorticoid steroids112 and anti-IL-13.118 A clinical decision support tool using a variety of input data, including genotypes of EoE-risk loci, to help physicians decide who is a strong candidate for endoscopy could greatly reduce the diagnostic odyssey experienced by many families.

To date, each of the studies of genetic loci that increase EoE risk have been performed at a population level using the genotypes of groups of people with and without EoE to identify loci that are statistically different and affect EoE risk in individual patients. In a predictive tool, the results of these studies would be used to create models of cumulative genetic risk for individual patients. For example, the individual effect sizes at 2p23 (odds ratio ~2.0) and 5q22 (odds ratio ~1.5) are still not yet useful for clinicians treating and diagnosing patients with suspected EoE in the clinic. However, by considering all of the risk loci, we are able to identify more clinically relevant risk assessments. For example, if an individual carried the risk variants for both the 2p23 and the 5q22 loci in a homozygous fashion (i.e., the risk variant on each homologous chromosome), that person would have a sevenfold increased risk of EoE compared with the general population (unpublished results). Similarly, tools could be developed to guide treatment of patients with EoE. The discovery of the tissue-specific 2p23 EoE-risk loci encoding calpain 14 has led to substantial opportunities for new therapies and understanding of disease etiology. The potential to find similar tissue-specific, pathoetiologic pathways is driving continuing efforts to fully identify the genetic etiology of EoE.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R37 AI045898, R01 AI124355, R01 DK107502, P30 AR070549, and U19 AI070235; Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease (CURED); Buckeye Foundation; American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED) e10078, and the Sunshine Charitable Foundation and its supporters, Denise A Bunning and David G Bunning. We would like to thank Daniele Goeke, Erin Zoller, Shawna Hottinger, and Amy Lawton for their editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

M.E.R. has received payment from Immune Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Celgene, and Genetech and has an equity interest in PulmOne, NKT Therapeutics, and Immune Pharmaceuticals and royalties from reslizumab (Teva Pharmaceuticals). L.C.K. and M.E.R. are inventors of several patents, owned by Cincinnati Children’s, and a set of these patents relates to molecular diagnostics of eosinophilic esophagitis.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.E.R. and L.C.K. developed, drafted, reviewed, and edited this manuscript.

References

- 1.Liacouras CA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;128:3–20.e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. quiz 21–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuta GT, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–1363. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingerski LM, et al. Health-related quality of life across pediatric chronic conditions. J. Pediatr. 2010;156:639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander ES, et al. Twin and family studies reveal strong environmental and weaker genetic cues explaining heritability of eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014;134:1084–1092.e1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kottyan LC, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of eosinophilic esophagitis provides insight into the tissue specificity of this allergic disease. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:895–900. doi: 10.1038/ng.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kottyan LC, Weirauch MT, Rothenberg ME. Making it big in allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;135:43–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchard C, et al. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;120:1292–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanchard C, Mishra A, Saito-Akei H, Monk P, Anderson I, Rothenberg ME. Inhibition of human interleukin-13-induced respiratory and oesophageal inflammation by anti-human-interleukin-13 antibody (CAT-354) Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2005;35:1096–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuo L, et al. IL-13 induces esophageal remodeling and gene expression by an eosinophil-independent, IL-13R alpha 2-inhibited pathway. J. Immunol. 2010;185:660–669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akei HS, Mishra A, Blanchard C, Rothenberg ME. Epicutaneous antigen exposure primes for experimental eosinophilic esophagitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:985–994. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins MH, et al. Newly developed and validated eosinophilic esophagitis histology scoring system and evidence that it outperforms peak eosinophil count for disease diagnosis and monitoring. Dis. Esophagus. 2016 doi: 10.1111/dote.12470. doi: 101111/dote.12470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen T, Rothenberg ME, Wang YH. Hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase defines a proeosinophilic pathogenic effector human T(H)2 cell subpopulation with enhanced function. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;137:919–921. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothenberg ME. Molecular, genetic, and cellular bases for treating eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1143–1157. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abonia JP, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis: rapidly advancing insights. Annu. Rev. Med. 2012;63:421–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041610-134138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogan SP, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophil function in eosinophil-associated gastrointestinal disorders. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2006;6:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s11882-006-0013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellon ES. The esophageal microbiome in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:364–365. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris JK, et al. Esophageal microbiome in eosinophilic esophagitis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singla MB, Moawad FJ. An overview of the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e155. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill DA, Spergel JM. The immunologic mechanisms of eosinophilic esophagitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16:9. doi: 10.1007/s11882-015-0592-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straumann A. Medical therapy in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2015;29:805–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuta GT, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:1640–1648. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1502863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green DJ, Cotton CC, Dellon ES. The role of environmental exposures in the etiology of eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015;90:1400–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oyoshi MK. Recent research advances in eosinophilic esophagitis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2015;27:741–747. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Travers J, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophils in mucosal immune responses. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:464–475. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis BP, Rothenberg ME. Emerging concepts of dietary therapy for pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2013;9:285–287. doi: 10.1586/eci.13.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson RC, et al. Accounting for multiple comparisons in a genome-wide association study (GWAS) BMC Genomics. 2010;11:724. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farh KK, et al. Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature. 2015;518:337–343. doi: 10.1038/nature13835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurano MT, et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science. 2012;337:1190–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.1222794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jurakic Toncic R, Marinovic B. What is new and hot in genetics of human atopic dermatitis: shifting paradigms in the landscape of allergic skin diseases. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2014;22:313–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ortiz RA, Barnes KC. Genetics of allergic diseases. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 2015;35:19–44. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laprise C, Bouzigon E. The genetics of asthma and allergic diseases: pieces of the puzzle are starting to come together. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;13:461–462. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328364ebc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sleiman PM, et al. GWAS identifies four novel eosinophilic esophagitis loci. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5593. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothenberg ME, et al. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:289–291. doi: 10.1038/ng.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller DE, Patel ZH, Lu X, Lynch AT, Weirauch MT, Kottyan LC. Screening for functional non-coding genetic variants using electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNA-affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) J. Vis. Exp. 2016 doi: 10.3791/54093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sleiman PM, March M, Hakonarson H. The genetic basis of eosinophilic esophagitis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2015;29:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blanchard C, et al. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:536–547. doi: 10.1172/JCI26679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanchard C, et al. Coordinate interaction between IL-13 and epithelial differentiation cluster genes in eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Immunol. 2010;184:4033–4041. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aceves SS, et al. Resolution of remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis correlates with epithelial response to topical corticosteroids. Allergy. 2010;65:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherrill JD, et al. Variants of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and its receptor associate with eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010;126:160–165. e163. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel ZH, et al. The struggle to find reliable results in exome sequencing data: filtering out Mendelian errors. Front Genet. 2014;5:16. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Namjou B, et al. Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) in EMR-linked pediatric cohorts, genetically links PLCL1 to speech language development and IL5–IL13 to eosinophilic esophagitis. Front. Genet. 2014;5:401. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sorimachi H, Hata S, Ono Y. Impact of genetic insights into calpain biology. J. Biochem. 2011;150:23–37. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noti M, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat. Med. 2013;19:1005–1013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahlen SE. TSLP in asthma—a new kid on the block? N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:2144–2145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1404737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Travers J, Rochman M, Miracle CE, Cohen JP, Rothenberg ME. Linking impaired skin barrier function to esophageal allergic inflammation via IL-33. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;138:1381–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun L, Jin H, Li H. GARP: a surface molecule of regulatory T cells that is involved in the regulatory function and TGF-beta releasing. Oncotarget. 2016;7:42826–42836. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fridrich S, et al. How soluble GARP enhances TGFbeta activation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang R, Zhu J, Dong X, Shi M, Lu C, Springer TA. GARP regulates the bioavailability and activation of TGFbeta. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:1129–1139. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cousineau I, Belmaaza A. EMSY overexpression disrupts the BRCA2/RAD51 pathway in the DNA-damage response: implications for chromosomal instability/recombination syndromes as checkpoint diseases. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2011;285:325–340. doi: 10.1007/s00438-011-0612-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livingston DM. EMSY, a BRCA-2 partner in crime. Nat. Med. 2004;10:127–128. doi: 10.1038/nm0204-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haber DA. The BRCA2-EMSY connection: implications for breast and ovarian tumorigenesis. Cell. 2003;115:507–508. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00933-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takeda K, et al. Essential role of Stat6 in IL-4 signalling. Nature. 1996;380:627–630. doi: 10.1038/380627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen XH, et al. Jak1 expression is required for mediating interleukin-4-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate and Stat6 signaling molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:6556–6560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quelle FW, et al. Cloning of murine Stat6 and human Stat6, Stat proteins that are tyrosine phosphorylated in responses to IL-4 and IL-3 but are not required for mitogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:3336–3343. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Shea JJ, Gadina M, Schreiber RD. Cytokine signaling in 2002: new surprises in the Jak/Stat pathway. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S121–S131. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bouffi C, et al. IL-33 markedly activates murine eosinophils by an NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism differentially dependent upon an IL-4-driven autoinflammatory loop. J. Immunol. 2013;191:4317–4325. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vaughn SE, et al. Lupus risk variants in the PXK locus alter B-cell receptor internalization. Front. Genet. 2014;5:450. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu TX, et al. MiR-375 is downregulated in epithelial cells after IL-13 stimulation and regulates an IL-13-induced epithelial transcriptome. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:388–396. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lim EJ, Lu TX, Blanchard C, Rothenberg ME. Epigenetic regulation of the IL-13-induced human eotaxin-3 gene by CREB-binding protein-mediated histone 3 acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:13193–13204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.210724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sherrill JD, et al. Analysis and expansion of the eosinophilic esophagitis transcriptome by RNA sequencing. Genes Immun. 2014;15:361–369. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miklossy G, Hilliard TS, Turkson J. Therapeutic modulators of STAT signalling for human diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013;12:611–629. doi: 10.1038/nrd4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kovalenko P, et al. Exploratory population PK analysis of Dupilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against IL-4Ralpha, in atopic dermatitis patients and normal volunteers. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2016;5:617–624. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Simpson EL, et al. Two phase 3 trials of Dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. f Med. 2016;375:2335–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rothenberg ME, et al. Intravenous anti-IL-13 mAb QAX576 for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Allergy and Clin. Immunol. 2015;135:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Litosh VA, Rochman M, Rymer JK, Porollo A, Kottyan L, Rothenberg ME. Calpain-14 and its association with eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.027. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Konikoff MR, et al. A randomized double-blind-placebo controlled trial of fluticasone proprionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1381–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davis BP, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis-linked calpain 14 is an IL-13-induced protease that mediates esophageal epithelial barrier impairment. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e86355. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ohbayashi N, Yatsu A, Tamura K, Fukuda M. The Rab21-GEF activity of Varp, but not its Rab32/38 effector function, is required for dendrite formation in melanocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:669–678. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tamura K, Ohbayashi N, Maruta Y, Kanno E, Itoh T, Fukuda M. Varp is a novel Rab32/38-binding protein that regulates Tyrp1 trafficking in melanocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:2900–2908. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fukuda M. Multiple roles of VARP in endosomal trafficking: rabs, retromer components and R-SNARE VAMP7 Meet on VARP. Traffic. 2016;17:709–719. doi: 10.1111/tra.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tamura K, Ohbayashi N, Ishibashi K, Fukuda M. Structure-function analysis of VPS9-ankyrin-repeat protein (Varp) in the trafficking of tyrosinase-related protein 1 in melanocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:7507–7521. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.191205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li G, Ma D, Chen Y. Cellular functions of programmed cell death 5. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1863:572–580. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi HK, et al. Programmed cell death 5 mediates HDAC3 decay to promote genotoxic stress response. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7390. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sundermeier TR, Vinberg F, Mustafi D, Bai X, Kefalov VJ, Palczewski K. R9AP overexpression alters phototransduction kinetics in iCre75 mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014;55:1339–1347. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hu G, Wensel TG. R9AP, a membrane anchor for the photoreceptor GTPase accelerating protein, RGS9-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9755–9760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152094799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnson JB, Boynton KK, Peterson KA. Co-occurrence of eosinophilic esophagitis and potential/probable celiac disease in an adult cohort: a possible association with implications for clinical practice. Dis. Esophagus. 2015;29:977–982. doi: 10.1111/dote.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dharmaraj R, Hagglund K, Lyons H. Eosinophilic esophagitis associated with celiac disease in children. BMC Res. Notes. 2015;8:263. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1256-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jensen ET, Eluri S, Lebwohl B, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Increased risk of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with active celiac disease on biopsy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;13:1426–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pellicano R, De Angelis C, Ribaldone DG, Fagoonee S, Astegiano M. 2013 update on celiac disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Nutrients. 2013;5:3329–3336. doi: 10.3390/nu5093329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stewart MJ, Shaffer E, Urbanski SJ, Beck PL, Storr MA. The association between celiac disease and eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kliewer KL, et al. Should wheat, barley, rye, and/or gluten be avoided in a 6-food elimination diet? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;137:1011–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peterson K, Firszt R, Fang J, Wong J, Smith KR, Brady KA. Risk of autoimmunity in EoE and families: a population-based cohort study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016;111:926–932. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Collins MH, et al. Clinical, pathologic, and molecular characterization of familial eosinophilic esophagitis compared with sporadic cases. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008;6:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Straumann A, et al. A new eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)-like disease without tissue eosinophilia found in EoE families. Allergy. 2016;71:889–900. doi: 10.1111/all.12879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rochman M, et al. Profound loss of esophageal tissue differentiation in eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.11.042. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Navabi B, Upton JE. Primary immunodeficiencies associated with eosinophilia. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2016;12:27. doi: 10.1186/s13223-016-0130-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Davis BP, Rothenberg ME. Mechanisms of disease of eosinophilic esophagitis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2016;11:365–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dietz HC. Marfan Syndrome. 2001 Apr 18 [Updated 2014 Jun 12] In: Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews®[Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2017. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1335/ [Google Scholar]

- 89.Syx D, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and clinical variability in musculocontractural Ehlers-Danlos syndrome caused by impaired dermatan sulfate biosynthesis. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:535–547. doi: 10.1002/humu.22774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sobey G. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: how to diagnose and when to perform genetic tests. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015;100:57–61. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sevenich M, Schultz-Ehrenburg U, Orfanos CE. Ehlers-Danolos syndrome: a disease of fibroblasts and collagen fibrils. classification and electron-microscopic findings in five patients (author’s transl) Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1980;267:237–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00403845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fragiadaki M, Ikeda T, Witherden A, Mason RM, Abraham D, Bou-Gharios G. High doses of TGF-beta potently suppress type I collagen via the transcription factor CUX1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2011;22:1836–1844. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lyons JJ, et al. Mendelian inheritance of elevated serum tryptase associated with atopy and connective tissue abnormalities. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014;133:1471–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abonia JP, et al. High prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with inherited connective tissue disorders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;132:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Samuelov L, et al. Desmoglein 1 deficiency results in severe dermatitis, multiple allergies and metabolic wasting. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1244–1248. doi: 10.1038/ng.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sherrill JD, et al. Desmoglein-1 regulates esophageal epithelial barrier function and immune responses in eosinophilic esophagitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:718–729. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brown SJ, McLean WH. Eczema genetics: current state of knowledge and future goals. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2009;129:543–552. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Netherton EW. A unique case of trichorrhexis nodosa; bamboo hairs. AMA Arch. Derm. 1958;78:483–487. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1958.01560100059009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Furio L, Pampalakis G, Michael IP, Nagy A, Sotiropoulou G, Hovnanian A. KLK5 inactivation reverses cutaneous hallmarks of Netherton syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Henderson CJ, et al. Increased prevalence of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014;58:553–560. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Milella M, et al. PTEN: multiple functions in human malignant tumors. Front. Oncol. 2015;5:24. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Crosby K, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 mutation with invasive eosinophilic disease. Allergy Rhinol. (Providence) 2012;3:e94–e97. doi: 10.2500/ar.2012.3.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Farmand S, Sundin M. Hyper-IgE syndromes: recent advances in pathogenesis, diagnostics and clinical care. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2015;22:12–22. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ma CS, et al. Deficiency of Th17 cells in hyper IgE syndrome due to mutations in STAT3. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1551–1557. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Holland SM, et al. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1608–1619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Walker S, et al. Identification of a gain-of-function STAT3 mutation (p.Y640F) in lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndrome. Blood. 2016;127:948–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-654277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hsu AP, et al. Autosomal dominant hyper IgE syndrome. 2010 Feb 23 [Updated 2012 Jun 7] In: Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2017. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK25507/ [Google Scholar]

- 108.Su HC. Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) deficiency. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010;10:515–520. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833fd718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Randall KL, et al. Dock8 mutations cripple B cell immunological synapses, germinal centers and long-lived antibody production. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:1283–1291. doi: 10.1038/ni.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang Q, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:2549–2566. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jensen ET, Dellon ES. Environmental and infectious factors in eosinophilic esophagitis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2015;29:721–729. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Butz BK, et al. Efficacy, dose reduction, and resistance to high-dose fluticasone in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:324–333 e325. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dellon ES. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2014;43:201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dellon ES, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009;7:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030. quiz 1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Franciosi JP, Tam V, Liacouras CA, Spergel JM. A case-control study of sociodemographic and geographic characteristics of 335 children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009;7:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Martin LJ, et al. Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis Symptom Scores (PEESS v2.0) identify histologic and molecular correlates of the key clinical features of disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;135:1519–1528. e1518. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wen T, Dellon ES, Moawad FJ, Furuta GT, Aceves SS, Rothenberg ME. Transcriptome analysis of proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia reveals proton pump inhibitor-reversible allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;135:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wen T, et al. Molecular diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis by gene expression profiling. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1289–1299. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dellon ES, Yellore V, Andreatta M, Stover J. A single biopsy is valid for genetic diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis regardless of tissue preservation or location in the esophagus. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2015;24:151–157. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.242.bsy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]