Abstract

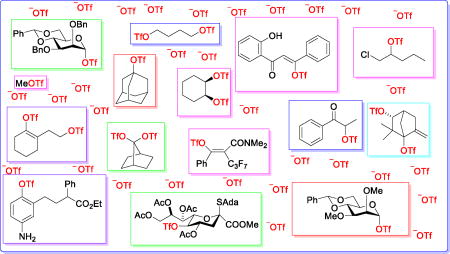

Although the triflate ion is not generally perceived as a nucleophile many examples of its behavior as such exist in the literature. This synopsis presents an overview of such reactions, in which triflate may be either a stoichiometric or catalytic nucleophile, leading to the suggestion that nucleophilic catalysis by triflate may be more common than generally accepted, albeit hidden by the typical reactivity of organic triflates which complicates their observation as intermediates.

Graphical abstract

The trifluoromethanesulfonate anion (triflate, TfO−) is an outstanding leaving group, and is widely used as such in organic chemistry,1–2 and nowhere more so than in carbohydrate chemistry.3–5 Conversely, the use of triflate as nucleophile in substitution reactions, albeit exploited since the very beginnings of triflate chemistry for the formation of simple alkyl triflates,6–8 is rarely considered, even though triflate is widely recognized as a co-ordinating anion in inorganic chemistry.9 This synopsis summarizes the literature on the action of triflate as nucleophile, whether by design or accident, with the aim of dispelling the notion of triflate as an innocent bystander in many reactions.

The powerful nucleofugal capacity of triflate in part arises from its ability to stabilize negative charge. However, literature values for the pKa of triflic acid in water vary over a range from −5.9 through −14, prompting Leito and coworkers to adopt a “crude average” value of −12±5 pKa units.10 Thus, in water, triflic acid is more acidic than bis(pentafluoroethyl)sulfonamide, HBr and HI (pKa: <−2, −9 and −9.5, respectively). Conversely, in organic solvents and in the gas phase although triflic acid is still a very strong acid, its pKa is little different from that of bis(pentafluoroethyl)sulfonamide.10

The ability to observe covalent triflates, whether formed by alcohol triflation or by nucleophilic attack of triflate on electrophiles, depends on the substrate and/or conditions suppressing displacement or solvolysis reactions. This is challenging in view of the triflate ion’s nucleofugal properties, and suggests that nucleophilic reactions of triflate may be more common than is generally believed. Triflate is not on any published scale of nucleophilicity including Mayr’s scale,11–12 which also does not contain mesylate, or iodide. Nevertheless, rate constants for the reaction of mesylate with 1-arylvinyl cations in acetonitrile were found to be ~102-fold less than those of acetate or iodide and some fifteen and seventy five-fold greater than those of bromide or chloride, respectively,13 suggesting that sulfonates may be more nucleophilic than commonly perceived. A computationally-derived intrinsic reactivity index14 affords a ranking of reactivity: Cl−> Br−>>AcO−>MeSO3−>TfO−>MeOH, with the latter two entries relevant to the question of catalysis by triflate in glycosylation and other reactions.

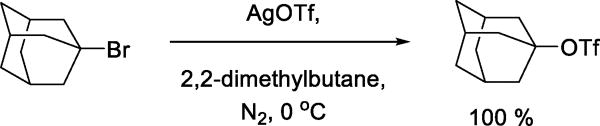

Because of the instability of many organic triflates, it is not surprising that early observations of triflate as nucleophile arose from metathesis reactions of organic halides with silver triflate driven by precipitation of silver halide. Thus, in 1956 Gramstad and Haszeldine reported the preparation of simple alkyl triflates by solvolysis of alkyl halides with silver triflate.6–7 This process, which is applicable to tertiary alkyl triflates, is illustrated with the preparation of 1-adamantanyl triflate (Scheme 1).15–16

Scheme 1.

Triflate Synthesis by Metathesis

The metathesis reaction extends to 1,n-dibromoalkanes for which a kinetic analysis revealed the participation of bridging bromonium ions and even of bridging trifloxy groups.17–18 In the reaction of propyl iodide with silver triflate the ratio of the resulting propyl and isopropyl triflates is solvent dependent.19 Reactions in benzene were slowest and were accompanied by the absence of rearrangement. This was attributed to solvation of the silver ion either i) reducing its electrophilicity and enforcing a more SN2-like transition state for the displacement, or ii) increasing the nucleophilicity of the triflate anion. In a study of the metal triflate-catalyzed hydroalkoxylation of alkenes, silver triflate was demonstrated to react with 1,2-dichloroethane to afford 2-chloroethyl triflate, whose subsequent decomposition yields triflic acid.20

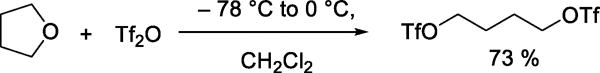

The preparation of simple alkyl triflates by nucleophilic substitution reactions, however, is not limited to metathesis reactions: methyl triflate is obtained by distillation of a mixture of triflic acid and dimethyl sulfate.8 The crystalline 1,4-ditrifloxybutane is obtained by reaction of tetrahydrofuran with triflic anhydride (Scheme 2).8

Scheme 2.

Preparation of 1,4-Ditrifloxybutane

The cleavage of ethers by trifluoroacetyl triflate also affords triflates by nucleophilic attack by triflate on the activated ether.21 Thus, a 1:1 mixture of ethyl trifluoroacetate and ethyl triflate is formed at 0 °C from diethyl ether (Scheme 3). Similarly, tetrahydrofuran afforded 1-trifluoromethanesulfonyl-4-trifluoroacetyl-1,4-butanediol quantitatively on reaction with trifluoroacetyl triflate.

Scheme 3.

Preparation of Ethyl Triflate from Diethyl Ether

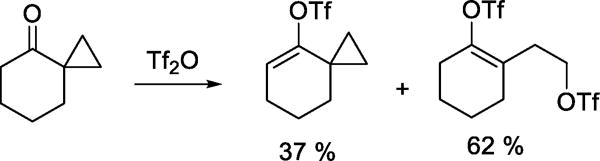

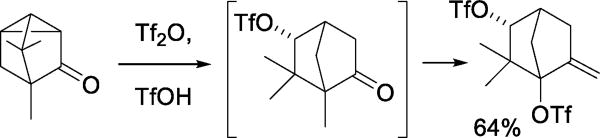

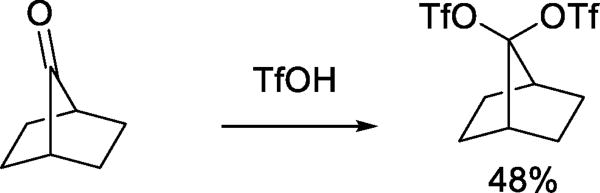

Other early indications of the nucleophilicity of triflate toward reactive cation-like electrophiles include the reaction of a spiro[5.2]octanone with triflic anhydride leading to the formation of two vinyl triflates, one of which involved nucleophilic cleavage of the spirocyclic system (Scheme 4).22 The reaction of β-pericyclocamphanone with a triflic anhydride/triflic acid mixture results in the formation of a rearranged ditriflate (Scheme 5),23 through a process initiated by nucleophilic ring opening of the cyclopropane by triflate, and completed by trapping of a tertiary cation by triflate following a series of 1,2-shifts and dehydrations. Triflate also serves as the nucleophile in the capture of carbenium ions generated by rearrangements of polycyclic aldehydes in the presence of benzoyloxy triflate.16 More interesting in the light of subsequent work on glycosyl triflates is the reaction of 7-norbornanone with triflic anhydride to give the corresponding geminal ditriflate (Scheme 6).24

Scheme 4.

Ring Opening of a Spiro Compound on Treatment with Triflic Anhydride

Scheme 5.

Rearrangement of β-Pericyclocamphanone with a Triflic Acid and Anhydride Mixture

Scheme 6.

Reaction of a Non-enolizable Ketone with Triflic Anhydride

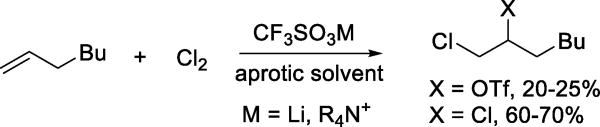

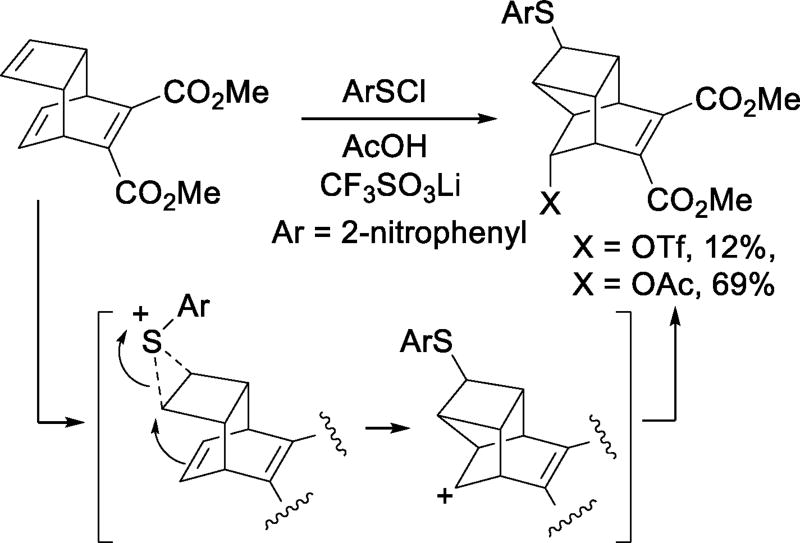

The Zefirov group provided examples of triflate acting as competitive nucleophile for the trapping of a variety carbocation-like electrophiles.25–26 Thus, the addition of halogens (Scheme 7) and arylsulfenyl chlorides to olefins in aprotic solvents, in the presence of lithium or tetraalkylammonium triflate affords the corresponding halo or arylsulfenyl triflates. The additions give the trans-adducts with cyclic alkenes and follow Markovnikov’s rule indicating that triflate acts as nucleophile on cyclic chloronium ions or related species. The addition of (2-nitrophenyl)sulfenyl chloride to a skeletally complex triene in acetic acid in the presence of lithium triflate afforded 12% of an endo-triflate resulting from rearrangement of the initial cationic intermediate together with 69% of the corresponding acetate (Scheme 8). Thus, the triflate anion is insufficiently nucleophilic to compete with the skeletal rearrangement, but does compete with the solvent for capture of the rearranged cation.27

Scheme 7.

Triflate Formation by Electrophilic Addition to Alkenes

Scheme 8.

Competitive Cation Trapping by Triflate in Acetic Acid

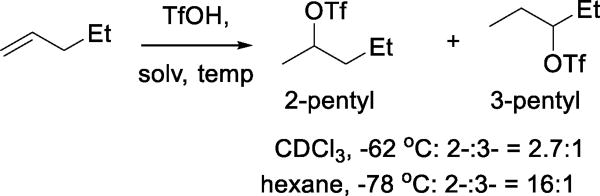

In an investigation into catalyst passivation during isobutene alkylation by olefins, the Markovnikov addition of triflic acid to simple alkenes forming alkyl triflates was investigated by NMR spectroscopy in CDCl3 at −62 °C,28 when even t-butyl triflate could be observed. Recalling the solvent dependence of the silver triflate-alkyl halide metathesis,19 addition to 1-pentene gave a 2.7:1 ratio of 2-pentyl/3-pentyl triflates in CDCl3, but in hexane at −78 °C a ratio of 16:1 was obtained. Thus, trapping of the initial carbenium ion by triflate trumps the 1,2-hydride shift under appropriate conditions (Scheme 9).28

Scheme 9.

Solvent Dependence in the Addition of Triflic Acid to 1-Pentene

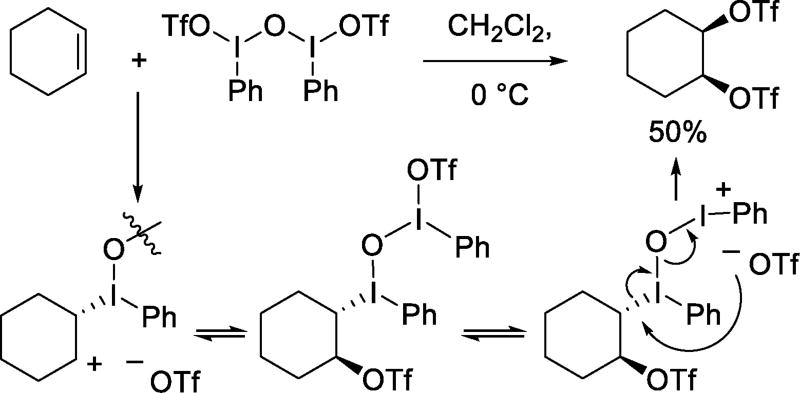

Hypervalent iodine reagent addition to olefins in the presence of lithium triflate can afford the corresponding bistriflates as in the addition of PhI(OAc)2 to 1-hexene when 1,2-ditrifloxyhexane is formed in 15% yield.29 Higher yields are achieved with μ-oxo-bis-phenyliodonium triflate. For example, reaction with cyclohexene affords the cis-1,2-ditriflate in 50% yield (Scheme 10),29–30 in a process arising from SN2-like nucleophilic displacement of an iodonium ion by triflate.

Scheme 10.

Reaction of Alkenes with Zefirov’s Reagent

In another hypervalent iodine-mediated reaction Moriarty and coworkers prepared α-keto triflates from silyl enol ethers and iodosobenzene in the presence of trimethylsilyl triflate. The mechanism involves attack of a silylated iodonium reagent on the enol ether to give an alkyliodonium species, followed by nucleophilic attack by triflate (Scheme 11).31

Scheme 11.

Reaction of a Silyl Enolether with Iodosobenzene and TMSOTf

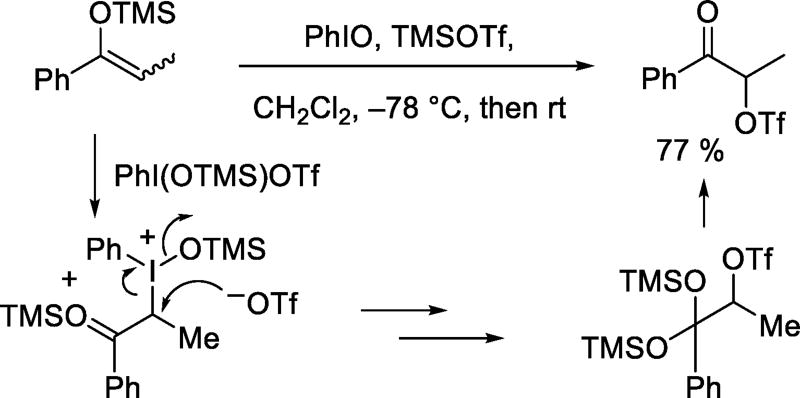

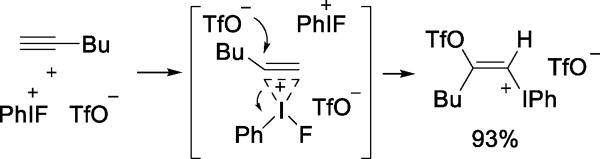

Reaction of various hypervalent iodonium triflates with alkynes affords crystallographically confirmed E-trifloxyvinyl aryliodonium triflates, by a process involving nucleophilic opening of iodonium adducts (Scheme 12).32–34

Scheme 12.

Reaction of Phenylfluoroiodonium Triflate with 1-Hexyne

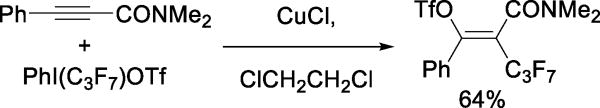

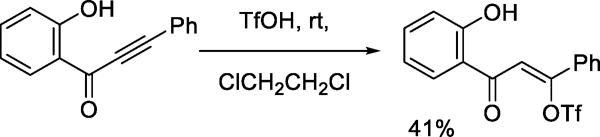

An alternative reaction for the formation of vinyl triflates uses copper-promoted reaction of alkynylarenes with phenyl perfluoroalkyliodonium triflates (Scheme 13). The mechanism invokes addition of a perfluoroalkyl radical to the alkyne generating a vinyl radical that is subsequently oxidized to the corresponding cation before nucleophilic trapping by triflate.35

Scheme 13.

Generation of Fluoroalkyl Vinyl Triflates from Alkynes

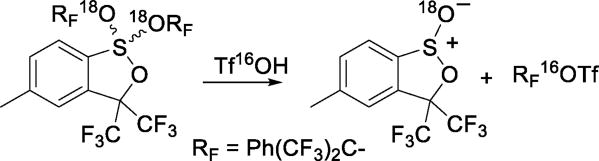

Reaction of certain dialkoxy sulfuranes with triflic acid affords the corresponding triflates in high yield.36 18O-Labelling studies indicated this reaction to proceed via trapping of α,α-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzyl cations by triflate (Scheme 14).

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of Triflates from Sulfuranes

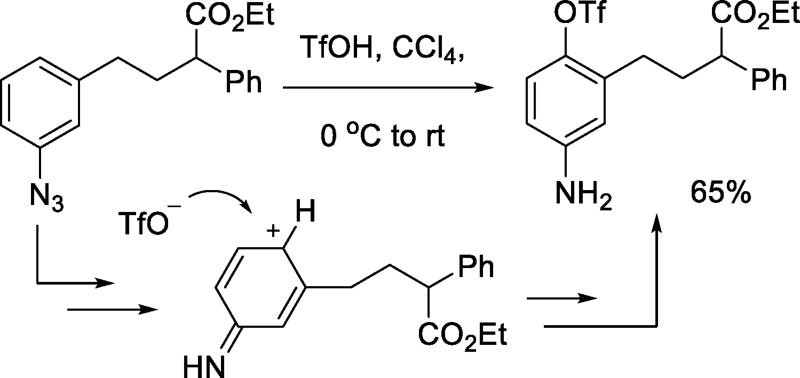

Earlier reports described the generation of aryl triflates by reaction of arenediazonium salts with trimethylsilyl triflate or triflic acid.37–38 More recent examples of the nucleophilicity of the triflate anion toward aryl cation-like electrophiles include the formation of p-aminoaryl triflates on treatment of aryl azides with triflic acid (Scheme 15).39 Vinyl triflates are isolated from the addition of triflic acid to aryl alkynyl ketones (Scheme 16),40 and have been postulated as intermediates in the reaction of benzhydryl triflate with phenylethyne.41

Scheme 15.

Addition of Triflate to Aryl Nitrenium Ions

Scheme 16.

Addition of Triflic Acid to an Aryl Alkynyl Ketone

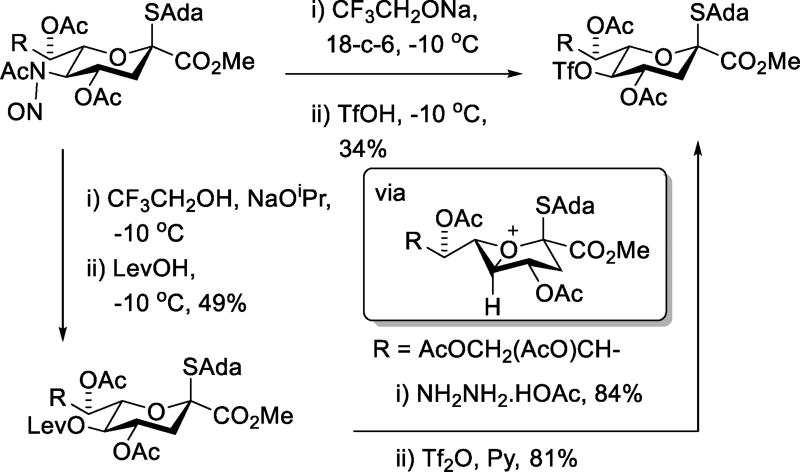

Drawing parallels with Zefirov’s generation of alkyl perchlorates in the nitrous acid-mediated deamination of aminoalkanes,42 we employed triflic acid as proton source and nucleophile in the Zbiral-type43–44 deamination of an N-nitroso-N-acetyl sialic acid derivative (Scheme 17).45 This reaction, which affords a single diastereomer of a stable triflate, appears to proceed via an intermediate 1-oxabicyclo[3.1.0]hexanium ion.44 The use of triflate as nucleophile in this manner is competitive with the more conventional but circuitous use of levulinic acid as nucleophile followed by deprotection and triflation of the residual alcohol (Scheme 17).45

Scheme 17.

Triflate as Nucleophile in Deamination

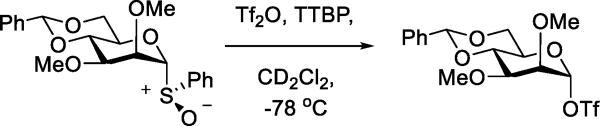

The most widespread use of triflate as nucleophile in preparative chemistry has been in the generation of glycosyl triflates for use as glycosyl donors. Under appropriate conditions, a range of glycosyl donors are readily converted to the corresponding glycosyl triflates. Early work was conducted by Schuerch and coworkers and employed the metathesis of per-O-benzyl-D-glucopyranosyl chloride with silver triflate at −78 °C enabling NMR characterization of the α-glycosyl triflate and studies of its reactivity.46–48 The perceived instability of the glycosyl triflates, however, was such that the majority of the work was conducted with the more stable glycosyl mesylates, tosylates and trifluoroethanesulfonates. Thus it was not until our demonstration by NMR methods of the generation of glycosyl triflates from glycosyl sulfoxides with triflic anhydride at low temperature (Scheme 18),49 that glycosyl triflates were accepted as tools for glycosidic bond formation and the study of glycosylation mechanisms.50–52 Subsequently it was demonstrated that glycosyl triflates may be accessed from many other classes of glycosyl donor by the application of triflate-based promoters. Such methods include the reaction of glycosyl trichloroacetimidates and TMSOTf in dichloromethane/ionic liquid mixtures,53 the reaction of glycosyl fluorides with TMSOTf,54 and the low temperature activation of thioglycosides with sulfenyl triflates and related species,55,56,57 among others.

Scheme 18.

Generation of a Mannosyl Triflate from the Sulfoxide

Many glycosyl triflates have now been characterized by low temperature NMR methods.58–59 The ensuing chemistry of the glycosyl sulfonates has been reviewed58,60–63 and will not be commented on here. It is, however, appropriate to contrast these methods involving nucleophilic attack of triflate on electrophilic glycosylating species, with the early work on the attempted generation of glycosyl triflates by triflation of anomeric hemiacetals. Thus, the activation of tetra-O-benzylglucopyranose with triflic anhydride in the absence of base was determined to involve simple triflic acid-mediated dehydrative coupling, rather than the formation of any intermediate glycosyl triflate.64–65 When such reactions are performed in the presence of collidine, the 1,1’-disaccharide is obtained as reaction of the hemiacetal with the glycosyl triflate is faster than with triflic anhydride.66 Clearly, as with the formation of simple alkyl triflates, methods involving nucleophilic attack of triflate on cation-like electrophiles generated in situ are superior to methods relying on triflation of the corresponding alcohols.

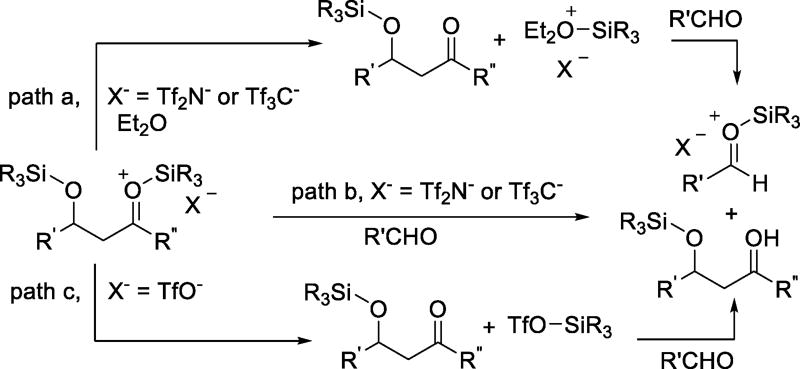

We now turn to the possible role of triflate as nucleophile in processes in which it is only present in catalytic quantities, limiting ourselves to bona fide cases based on experimental evidence. Thus, in an investigation of the role of the conjugate base in Lewis acid-mediated Mukaiyama aldol reactions, Yamamoto and coworkers demonstrated by crossover experiments that the mode of transfer of a trialkylsilyl group from the immediate condensation product to a further molecule of aldehyde is counterion dependent. With trialkylsilyl triflimide and trialkylsilyl tris(triflyl)methide, the transfer of the silyl group occurs either directly or is mediated by the solvent when the reaction is run in diethyl ether (Scheme 19, paths a and b). Conversely, when the catalyst is a trialkylsilyl triflate, silyl group transfer is mediated by the triflate anion and involves reformation of a silyl triflate (Scheme 19, path c). The greater nucleophilicity of triflate as compared to triflimide and Tf3C− was offered in explanation of this difference in pathways.67 Observations by Mathieu and Ghosez also support the notion of the triflate anion being more tightly bound to the trimethylsilyl “cation” than triflimide.68 The divergent pathways observed in the reactions of acyl polysilanes with either TMSOTf or TMSNTf2 were also attributed to the enhanced nucleophilicity of triflate as compared to triflimide.69

Scheme 19.

Counterion-Dependent Pathways for Silyl Transfer in the Mukaiyama Aldol Reaction

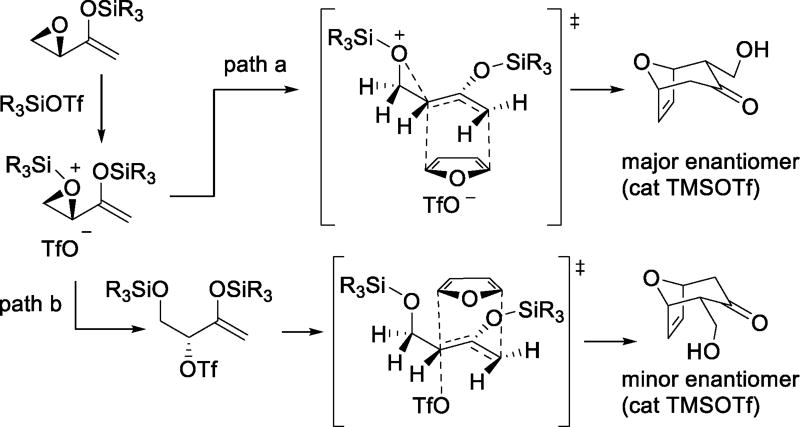

In a study of the formal [4+3] cycloaddition of epoxy enolsilanes with dienes catalyzed by trialkyl silyl triflates, evidence was presented for the intervention of triflate as nucleophile toward the O-silylated epoxide in the formation of the minor enantiomers of both the exo and endo-products. Under typical conditions with catalytic silyl triflate, the major enantiomers of the exo and endo-products are considered to be formed via an asynchronous SN2-like ring opening of the silylated epoxide by the diene with a subsequent barrierless formation of the remaining CC bond (Scheme 20, path a). Conversely, SN2 ring opening of the silylated epoxide by the catalytic triflate followed by SN2-like displacement of the triflate by the diene with subsequent collapse to the cycloadduct gives the minor enantiomers (Scheme 20, path b). The critical role of triflate in this latter process was confirmed by: i) Addition of the diene to a preformed mixture of epoxy enolsilane and TESOTf resulting in predominance of path b (Scheme 20), and reversal of the overall selectivity, and ii) replacement of TESOTf by TES[C6F5)4B], when no loss of enantioselectivity was observed.70

Scheme 20.

Triflate-dependent Enantioselectivity in the Trialkylsilyl Triflate-catalyzed [4+3] Cycloadditions of Epoxy Enolsilanes with Dienes (endo-adducts only illustrated)

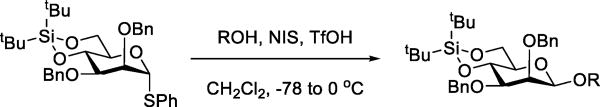

The issue of catalysis by triflate in glycosylation reactions promoted by sub-stoichiometric amounts of triflate-based promoters was raised by Bols and coworkers. These workers discovered that a 4,6-O-silylene protected mannosyl thioglycoside was β-selective in its reactions with alcohols in reactions conducted at room temperature with activation by N-iodosuccinimide and only 10 mol% of triflic acid (Scheme 21).71 This observation, coupled with the parallel identification of a β-selective reaction promoted by silver perchlorate in the absence of triflate, led the authors to propose that the β-selectivity arose not from displacement of an intermediate α-glycosyl triflate, but by β-face attack on a glycosyl oxocarbenium ion in B2,5 conformation. As reported previously, the cognate 4,6-O-benzylidene oxocarbenium ion does access the B2,5 conformation72 and is β-selective in its reactions with C-nucleophiles.73 However, the evidence for the nucleophilicity of perchlorate toward cation-like electrophiles exceeds even that for triflate26 suggesting the intermediacy of a α-glycosyl perchlorate in the triflate-free reaction. Indeed, glycosyl perchlorates were observed spectroscopically more than two decades before glycosyl triflates.74 In a follow up to this work Bols and coworkers applied similar conditions, catalytic in triflate, to the activation of 4,6-O-benzylidene protected mannosyl thioglycosides and sulfoxides with comparable results.75 Also studied was the activation of a 4,6-O-benzylidene protected α-trichloroacetimidate with BF3OEt2 in the presence and absence of triflate. In the complete absence of triflate, β-mannosides were not formed owing to the well-known competing abstraction of fluoride from the reagent,76 but β-mannoside formation was restored on addition of lithium triflate, ultimately leading the authors to remark on the beneficial catalytic effect of the triflate ion.75

Scheme 21.

β-Selective Mannosylation with only Catalytic Triflic Acid

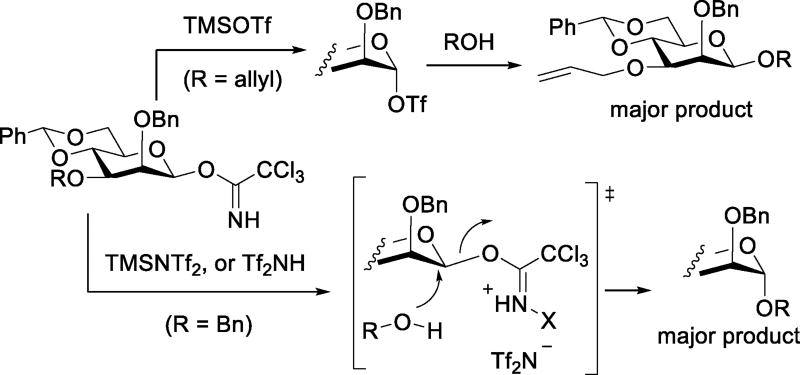

Continuing this thread, Kowalska and Pedersen studied the glycosylation reactions of 4,6-O-benzylidene protected mannosyl trichloroacetimidates with activation by bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide and its N-TMS derivative. Stereoselectivity was found to depend on the configuration of the initial trichloroacetimidate, with substitution taking place mostly with inversion of configuration from either anomer. These observations contrast with earlier work on the activation of comparable 4,6-O-benzylidene protected mannosyl trichloroacetimidates by catalytic TMSOTf, when both anomers were described as giving comparable β-selectivity (Scheme 22).77 This dependence of anomeric selectivity on the promoter was rationalized in terms of the differing nucleophilicity of triflimide and triflate: reactions conducted with a triflimide-based activator involve direct displacement of the activated trichloroacetimidate by the acceptor alcohol,78 albeit a glycosyl triflimide has been tentatively identified by NMR spectroscopy in previous work by Yoshida and coworkers.79 Reactions employing the more nucleophilic triflate progress via the formation of a glycosyl triflate.78

Scheme 22.

Diverging Reaction Pathways on the Activation of β-Mannopyranosyl Trichloroacetimidates with Triflate and Triflimde-Based Promoters

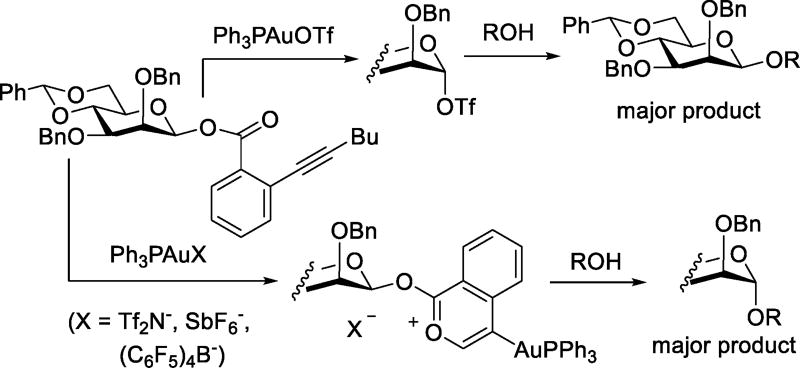

In contemporaneous work, Zhu and Yu investigated the activation of two mannosyl o-alkynyl benzoates with a series of gold complexes.80 With catalytic Ph3PAuOTf both anomers of the donor gave comparable results indicative of a common intermediate, demonstrated to be the α-mannosyl triflate by NMR spectroscopy. Conversely, on activation with the Ph3PAu complexes of triflimide, hexafluoroantimonate, and tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate, the two anomers gave opposite selectivities, both reacting with predominant inversion of configuration. It was demonstrated that activation with the gold complexes afforded the corresponding mannosyloxy isochromenylium-4-gold complexes, which were directly displaced by the incoming acceptor alcohols to afford the glycosides. With triflate as counter-ion, the gold complex is first converted to the anomeric triflate that then serves as the active glycosyl donor (Scheme 23). The striking change in mechanism with counterion not only requires the formation of an intermediate glycosyl triflate, but also that the catalytic triflate competes effectively with the acceptor alcohol as nucleophile for the displacement of the initial gold isochromylium oxy complex.

Scheme 23.

Counterion-dependent Mechanisms in Gold-Catalyzed β-Mannosylations (Illustrated for the β-donor only)

Conclusion

The evidence for the action of triflate as nucleophile toward cation-like electrophiles is considerable and, in stoichiometric processes, covers many areas of organic chemistry and many types of reaction. Good evidence also exists for the role of triflate as a nucleophilic catalyst in several reactions, suggesting that the phenomenon may be widespread even if not always apparent because of the high reactivity of the intermediate covalent triflates. In common with all entities that are effective nucleophilic catalysts, it appears that the activation barriers for both the addition of triflate to a given electrophile and its subsequent departure are low.

Acknowledgments

Support of the NIH (GM62160) for work at Wayne State University on the mechanisms of glycosylation reactions is gratefully acknowledged.

Biographies

Bibek Dhakal

Bibek Dhakal received a BSc degree in Chemistry in 2007 from Tribhuvan University, Nepal, and an MSc degree in Organic Chemistry in 2011 from Osmania University, India. He moved to Wayne State University in 2013 and is currently a PhD candidate in organic chemistry with Professor David Crich. His research focuses on the synthesis of sialic acid donors and their subsequent use in stereocontrolled glycosylation reactions.

Luis Bohé

Luis Bohé is Chargé de Recherche at the CNRS Institute for Natural Products Chemistry in Gif-sur-Yvette, France and maintains a strong interest in synthetic methodology, reaction mechanisms, and glycochemistry.

David Crich

David Crich is Schaap Professor of Organic Chemistry at Wayne State University where he and his coworkers conduct an extensive program of research in the fields of glycochemistry and the design and development of antibiotics for the treatment of multidrug resistant infectious diseases. He is cofounder of the biotech startup Juvabis GmbH.

References

- 1.Howells RD, McCown JD. Chem. Rev. 1977;77:69–92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stang PJ, Hanack M, Subramanian LR. Synthesis. 1982:85–126. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binkley RW, Ambrose MG. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 1984;3:1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binkley ER, Binkley RW. In: Preparative Carbohydrate Chemistry. Hanessian S, editor. Dekker; New York: 1997. pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hale KJ, Hough L, Manaviazar S, Calabrese A. Org. Lett. 2014;16:4838–4841. doi: 10.1021/ol502193j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gramstad T, Haszeldine RN. J. Chem. Soc. 1956:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dafforn GA, Streitwieser A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970;11:3159–3162. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beard CD, Baum K, Grakauskas V. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:3673–3677. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss SH. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:927–942. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raamat E, Kaupmees K, Ovsjannikov G, Trummal A, Kütt A, Saame J, Koppel I, Kaljurand I, Lipping L, Rodima T, Pihl V, Koppel IA, Leito I. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2013;26:162–170. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayr H. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:5095–5111. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayr H, Ofial AR. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:952–965. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrne PA, Kobayashi S, Würthwein E-U, Ammer J, Mayr H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1499–1511. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiyooka S-i, Kaneno D, Fujiyama R. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:4247–4258. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeuchi K, Moriyama T, Kinoshita T, Tachino H, Okamoto K. Chem. Lett. 1980:1395–1398. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeuchi K, Kitagawa I, Akiyama F, Shibata T, Kato M, Okamoto K. Synthesis. 1987:612–615. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman RD, Andreshak JL, Herrlinger SP, Shackelford SA, Hildreth RA, Smith JP. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:3792–3798. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman RD, Andreshak JL, Shackelford SA. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:3771–3775. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beard CD, Baum K. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:3875–3877. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dang TT, Boeck F, Hintermann L. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:9353–9361. doi: 10.1021/jo201631x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forbus TR, Taylor SL, Martin JC. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:4156–4159. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia Fraile A, Garcia Martinez A, Herrera Fernandez A, Sanchez Garcia JM. An. Quim. 1979;75:723–725. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia Martinez A, Garcia Fraile A. An. Quim. 1980;76:127–129. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia Martinez A, Rios IE, Vilar ET. Synthesis. 1979:382–383. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zefirov NS, Koz'min AS, Zhdankin VV, Kirin NM, Yur'eva NM, Sorokin VD. Chem. Script. 1983;22:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zefirov NS, Koz'min AS. Acc. Chem. Res. 1985;18:154–158. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zefirov NS, Koz'min AS, Sorokin VD, Zhdankin VV. Zh. Org. Khim. 1983;19:876–878. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hommeltoft SI, Ekelund O, Zavilla J. Ind. Eng, Chem. Res. 1997;36:3491–3497. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zefirov NS, Zhdankin VV, Dan'kov YV, Sorokin VD, Semerikov VN, Koz'min AS, Caple R, Berglund BA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:3971–3974. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hembre RT, Scott CP, Norton JR. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:3650–3654. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriarty RM, Epa WR, Penmasta R, Awasthi AK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:667–670. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitamura T, Furuki R, Taniguchi H, Stang PJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:703–704. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gately DA, Luther TA, Norton JR, Miller MM, Anderson OP. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:6496–6502. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasumov TM, Pirguliyev NS, Brel VK, Grishin YK, Zefirov NS, Stang PJ. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:13139–13148. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Studer A. Org. Lett. 2017;19:2977–2980. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Astrologes GW, Martin JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:4400–4404. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olah GA, Wu AH. Synthesis. 1991:204–206. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoneda N, Fukuhara T, Mizokami T, Suzuki A. Chem. Lett. 1991:459–460. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinto O, Sardinha J, Vaz PD, Piedade F, Calhorda MJ, Abramovitch R, Nazareth N, Pinto M, Nascimento MSJ, Rauter AP. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:3175–3187. doi: 10.1021/jm101182s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida M, Fujino Y, Doi T. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4526–4529. doi: 10.1021/ol2016934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcuzzi F, Modena G, Melloni G. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:4577–4579. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zefirov NS, Koz'min AS, Kirin VN, Yur'eva NM, Zhdankin VV. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1982;31:2330–2330. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schreiner E, Zbiral E. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1990:581–586. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buda S, Crich D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1084–1092. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhakal B, Buda S, Crich D. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:10617–10630. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kronzer FJ, Schuerch C. Carbohydr. Res. 1973;27:379–390. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lucas TJ, Schuerch C. Carbohydr. Res. 1975;39:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)82649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marousek V, Lucas TJ, Wheat PE, Schuerch C. Carbohydr. Res. 1978;60:85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crich D, Sun S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:11217–11223. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crich D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:1144–1153. doi: 10.1021/ar100035r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang M, Garrett GE, Birlirakis N, Bohé L, Pratt DA, Crich D. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:663–667. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adero PO, Furukawa T, Huang M, Mukherjee D, Retailleau P, Bohé L, Crich D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:10336–10345. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rencurosi A, Lay L, Russo G, Caneva E, Poletti L. Carbohydr. Res. 2006;341:903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia BA, Gin DY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4269–4279. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crich D, Sun S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:435–436. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crich D, Smith M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:9015–9020. doi: 10.1021/ja0111481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rönnols J, Walvoort MTC, van der Marel GA, Codée JDC, Widmalm G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:8127–8134. doi: 10.1039/c3ob41747f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aubry S, Sasaki K, Sharma I, Crich D. Top. Curr. Chem. 2011;301:141–188. doi: 10.1007/128_2010_102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frihed TG, Bols M, Pedersen CM. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:4963–5013. doi: 10.1021/cr500434x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crich D. In: Glycochemistry: Principles, Synthesis, and Applications. Wang PG, Bertozzi CR, editors. Dekker; New York: 2001. pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crich D. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2002;21:663–686. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crich D, Lim LBL. Org. React. 2004;64:115–251. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bohé L, Crich D. In: Selective Glycosylations – Synthetic Methods and Catalysts. Bennett SC, editor. Wiley; Hoboken: 2017. pp. 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lacombe JM, Pavia AA, Rocheville JM. Can. J. Chem. 1981;59:473–481. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pavia AA, Ung-Chhun SN. Can. J. Chem. 1981;59:482–489. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leroux J, Perlin AS. Carbohydr. Res. 1978;67:163–178. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hiraiwa Y, Ishihara K, Yamamoto H. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:1837–1844. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mathieu B, Ghosez L. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:8219–8226. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berry MB, Griffiths RJ, Howard JAK, Leech MA, Steel PG, Yufit DS. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 1. 1999:3645–3650. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krenske EH, Lam S, Ng JPL, Lo B, KuiLam S, Chiu P, Houk KN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:7422–7425. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heuckendorff M, Bendix J, Pedersen CM, Bols M. Org. Lett. 2014;16:1116–1119. doi: 10.1021/ol403722f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang M, Retailleau P, Bohé L, Crich D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14746–14749. doi: 10.1021/ja307266n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moumé-Pymbock M, Crich D. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:8905–8912. doi: 10.1021/jo3011655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Igarashi K, Honma T, Irisawa J. Carbohydr. Res. 1970;15:329–337. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heuckendorff M, Bols PS, Barry C, Frihed TG, Pedersen CM, Bols M. Chem. Commun. 2015:13283–13285. doi: 10.1039/c5cc04716a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suzuki S, Matsumoto K, Kawamura K, Suga S, Yoshida J-i. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3755–3758. doi: 10.1021/ol048524h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weingart R, Schmidt RR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:8753–8758. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kowalska K, Pedersen CM. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:2040–2043. doi: 10.1039/c6cc10076g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yamago S, Yamada H, Maruyama T, Yoshida J-i. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2145–2148. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhu Y, Yu B. Chem. Eur. J. 2015;21:8771–8780. doi: 10.1002/chem.201500648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]