Abstract

Elderly cancer patients treated with ionizing radiation (IR) or chemotherapy experience more frequent and greater normal tissue toxicity relative to younger patients. The current study demonstrates that exponentially growing fibroblasts from elderly (old) male donor subjects (70, 72, 78 years) are significantly more sensitive to clonogenic killing mediated by platinum-based chemotherapy and IR, (~70–80% killing) relative to young fibroblasts (5 months and 1 year; ~10–20% killing) and adult fibroblasts (20 years old; ~10–30% killing). Old fibroblasts also displayed significantly increased (2–4 fold) steady-state levels of O2•−, O2 consumption, and mitochondrial membrane potential as well as significantly decreased (40–50%) electron transport chain (ETC) complex I, II, IV, V, and aconitase (70%) activities, decreased ATP levels, and significantly altered mitochondrial structure. Following adenoviral-mediated overexpression of SOD2 activity (5–7 fold), mitochondrial ETC activity and aconitase activity were restored, demonstrating a role for mitochondrial O2•− in these effects. Old fibroblasts also demonstrated elevated levels of endogenous DNA damage that were increased following treatment with IR and chemotherapy. Most importantly, treatment with the small-molecule, superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic (GC4419; 0.25 µM), significantly mitigated the increased sensitivity of old fibroblasts to IR and chemotherapy and partially restored mitochondrial function without affecting IR or chemotherapy-induced cancer cell killing. These results support the hypothesis that age-associated increased O2•− and resulting DNA damage mediate the increased susceptibility of old fibroblasts to IR and chemotherapy and can be mitigated by GC4419.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Radiation, Electron transport chain, Mitochondria, Superoxide dismutase mimics

Introduction

Cancer incidence and survival rates are expected to increase by over 50% during the next twenty years predominantly due to an aging population and improved therapeutic outcomes (1). By the year 2020, there will be approximately 18,000,000 cancer survivors in the United States (1). Acute and chronic normal tissue injuries resulting from combined modality radiation and chemotherapies represent highly significant treatment limiting complications that are exacerbated in elderly patients (2,3). Currently there are limited data available on the age-associated mechanisms of normal tissue injury associated with ionizing radiation (IR) and chemotherapy as well as few treatment options for preventing or mitigating this injury.

Numerous studies examining pathways that connect the processes governing aging and cancer have focused on cellular oxidative metabolism (4–6). Furthermore, normal tissue injury associated with cancer therapy has been hypothesized to involve alterations to mitochondrial oxidative metabolism leading to increased steady-state levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (7,8). Recently, several studies have utilized mitochondrially targeted antioxidants to mitigate IR-induced skin damage preventing dermatitis, inflammation and fibrosis thereby preserving the antioxidant capacity of the skin following IR exposure (9,10). The mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes (ETCs) located on the inner mitochondrial membrane are believed to be a major metabolic site of ROS production in mammalian cells with 0.1–1% of the electrons that flow through the ETCs predicted to undergo one-electron reductions of oxygen forming O2•− and H2O2 (11). Furthermore increased steady-state levels of ROS are reported to progressively increase with aging (5,7). Mutations in mitochondrial DNA and nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins are known to accumulate during the aging process (12) and are again associated with increased levels of O2•−, H2O2, and genomic instability (13,14). In addition, the age-associated vulnerability of mammalian cells to accumulate DNA damage is also suggested to derive from a progressive decline in DNA repair processes (15). Thus, increased production of O2•− and H2O2 as well as the accumulation of DNA damage along with changes in mitochondrial function (6,7,15) appear to be fundamental to both cancer and aging processes but the relative contribution of O2•− to the increased sensitivity of normal human cells from elderly patients to radiation and chemotherapy is unknown.

The current study demonstrates that exponentially growing early passage human fibroblasts, from elderly (old) male donor subjects (70, 72, 78 years), are significantly more sensitive to clonogenic killing mediated by platinum-based chemotherapy and IR, relative to young fibroblasts from male donor subjects (5 months and 1 year) and/or adult fibroblasts from a male donor subject (20 year old). Furthermore, old fibroblasts also showed significant alterations in mitochondrial ETC and aconitase activities. Mitochondrial ETC activity and aconitase activity were restored by SOD2 overexpression clearly demonstrating a role for mitochondrial O2•− in these effects. Donor age-associated alterations in mitochondrial metabolism were found to be accompanied by down-regulation of mitochondrial ETC gene expression in old fibroblasts. Furthermore, old fibroblasts also demonstrated elevated levels of endogenous DNA damage that were increased following treatment with IR and chemotherapy. Most importantly, treatment with a small-molecule, superoxide-specific SOD mimetic (GC4419) mitigated the increased sensitivity of old fibroblasts to IR and chemotherapy as well as partially restored mitochondrial function without affecting IR or chemotherapy-induced cancer cell killing. These results show age-associated increases in O2•−, DNA-damage, and compromised mitochondrial function result in increased sensitivity of old fibroblasts to IR and chemotherapy that can be inhibited by an SOD mimetic, GC4419, which is currently being studied clinically as a mitigator for oral mucositis in head and neck cancer subjects (NCT02508389). These results support the hypothesis that the use of SOD mimetics in elderly cancer patients undergoing radiation and chemotherapy may have significant benefit in enhancing the tolerability of cancer therapies as well as reducing the chronic toxicities associated with cancer survivorship.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, media and culture conditions

Dermal fibroblasts, from young donor male subjects (5 months and 1 year), adult donor male subject (20 year old) and old donor male subjects (70, 72, 78 years), were obtained from Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, New Jersey). Tissues used to isolate dermal fibroblasts were initially submitted to Coriell from 1973–1982. Cell culture identify was authenticated by PCR using microsatellite and Y-chromosome-specific primer pairs. Dermal fibroblasts were obtained from Coriell between 2015 and 2017. The cells were received at passage 12 (Young), passage 13 (Adult) and passages 14–15 (Old) from the vendor. All cells were maintained at 37°C in 4% O2 and 5% CO2. Mycoplasma was assessed for using the LONZA MycoAlert© Mycoplasma Detection Kit. Low-serum fibroblast basal medium (PCS-201-030) from ATCC (Manassas, VA) was used as the cell culture growth medium. The growth medium was supplemented with additional factors in the fibroblasts growth kit-low serum (PCS-201-041). Cells used in all experiments were frozen in the above mentioned media with 10% FBS and 10% DMSO. Cells were passaged using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA. All cells were grown and maintained at 37°C and 4% O2. Unless specified otherwise, the results were tested in dermal fibroblasts from two young (5 month old and one year old), one adult (20 year old) and three old (70, 72 and 78 years old) male donors. Data were analyzed by taking the pooled mean of the data from the different cell sources in each age group. Exponentially-growing cultures of fibroblasts were used from passages 3–7 (passage 1 was defined as when the cells were received from Coriell) for all experiments.

Radiation, chemotherapy and mimetic treatment

Irradiation was performed on cells plated in 60 or 100 mm dishes with complete media. Typically, cells were allowed to attach for at least 24–48 hours at 4% O2 and 37°C to obtain exponentially growing cultures at around 50–70% confluence for all experiments unless specified otherwise. Cells were irradiated from 2–4 Gy X-rays in the Radiation and Free Radical Research Core laboratory at the University of Iowa. Radiation was given at 1.29 Gy/min and was delivered using a PANTAK HF-320 ortho volt X-ray unit. All in vitro irradiations used 200 kVp x-rays, 15 mA with a filter composed of 0.35 mm copper (Cu) + 1.5 mm aluminium (Al). After irradiation the cells were plated for clonogenic cell survival within an hour. For the experiments in vivo, animals were arranged in lead coffins with only their left legs exposed to the X-ray source. All ions 200 kVp x-rays, 15 mA with a filter composed of 0.35 mm copper (Cu). Radiation was given at 3 Gy/min with the head height at 30 cms delivered using a PANTAK HF-320 orthovolt X-ray unit. Cisplatin (1 mg/mL) (Molecular weight 300) was purchased from Hospira, Inc. (Lake Forest, IL) and carboplatin (10 mg/mL) (Molecular weight 371) was purchased from APP Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC) (Lake Zurich, IL) and were further diluted in H2O prior to use to achieve the desired concentrations. GC4419 (Galera Therapeutics, Molecular weight 483) was prepared at a stock concentration of 10 mM in H2O with 10 mM sodium bicarbonate (pH 7.1–7.4) that was diluted in order to achieve a final concentration of 0.25 µM and was added 72 hours prior to and during the experiment unless specified otherwise. GC4419 (previously known as M40419) is a small molecular weight SOD mimetic specific for dismutation of superoxide with a rate constant of (1 × 107 mol−1 s−1) (16) which is comparable to the native SOD enzyme (1.2 × 109 mol−1 s−1) (17).

Animals and radiation conditions

All young (2 months) and adult mice (7 months) were C57BL/6J obtained from Jackson laboratory (#000664) and the old (31 months) mice were C57BL/6J obtained from Dr. James Martin’s lab at the University of Iowa. All mice were maintained in accordance with ACURF approval #4111207 at the University of Iowa Animal Care facility. Mice were maintained on normal diets and water ad libitum through the course of the experiment. Young, adult and old mice were irradiated with a single dose of 45 Gy X-rays to the right leg in the Radiation and Free Radical Research Core laboratory at the University of Iowa. Radiation was delivered using a PANTAK HF-320 orthovolt X-ray unit as described above. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee IACUC).

Growth Curve, Cell Number and Doubling Time Calculations

Growth curves were generated to determine the rate of proliferation in the exponentially growing young and old fibroblasts. Cells were plated in six-well plates with 50,000 cells/dish. Cell numbers were counted days 1–5 (using Beckman Z1 particle counter; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, California) and the growth curves (cell#/time) were constructed. The doubling time (DT) was calculated from the exponential part of the growth curve using the equation: DT = 0.693*t/ ln (Nt/N0) where t is the time in hours, Nt is number of cells at time t and N0 is the number of cells at the initial time. The average DT is calculated with the doubling times from passages 3–7.

Clonogenic Survival Assay

To determine the effect of age on the reproductive integrity, young and old fibroblasts were plated at 50,000 per 60 mm dish and 48 hours post plating, both floating and attached cells from control or treated dishes were collected by treatment with trypsin (0.25%). Trypsin was inactivated with full fibroblasts media containing 1% FBS and growth factors following which the cells were centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 mins and re-suspended in fresh media. Cell counts were made with a Coulter Counter and the cells were plated at various densities on lethally irradiated feeder cells (see below) and allowed to grow for 10–12 days in complete media at 4% O2. Subsequently, the cells were stained with Coomassie Blue dye, and the colonies of greater than 50 cells on each plate were counted and recorded, and clonogenic cell survival was determined, as described previously (18). Surviving fraction was determined as the number of colonies per plate divided by the number of cells initially added to that plate. Normalized surviving fraction (NSF) was determined as the surviving fraction of any given clonogenic plate from a treatment group divided by the average surviving fraction of the control (untreated) plates within a given experiment.

B1 Feeder Layer Cells

During clonogenic survival assays, both young and old fibroblasts were grown on a feeder layer of lethally irradiated Chinese hamster fibroblasts designated as B1 using the complete fibroblast media recipe containing FBS and growth factors. B1 cells (passage 20–40) are maintained in high glucose DMEM 1X media containing L-glutamine and sodium pyruvate and supplemented with 10% Fetal bovine serum, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 1X MEM non-essential amino acids. The B1 feeders were grown at 21% oxygen and the feeder layer was prepared 24 hours prior to any clonogenic survival assay by irradiating the cells with 30 Gy of X-rays at a dose rate of 27 Gy/min. Each clonogenic experiment had two extra dishes plated with feeder cells to ensure no colony growth at the end of the 10–12 day incubation.

DHE oxidation levels using flow cytometry

Steady-state levels of superoxide were estimated using oxidation of the fluorescent dye, dihydroethidium (DHE) purchased from Invitrogen (Eugene, Oregon) as described previously (13). Following labeling with 10 µM DHE at 37°C for 20–30 min, the samples were analyzed using LSR violet flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immuno-cytometry System, INC., Mountain View, CA) (excitation 405 and 488 nm, emission 585 nm band-pass filter). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 10,000 cells was analyzed per sample and corrected for auto-fluorescence from unlabeled cells. Each sample was normalized to the young fibroblast group, to yield the normalized mean fluorescent intensity (NMFI).

MitoSOX Red oxidation levels using flow cytometry

Estimates of steady-state levels of mitochondrial superoxide in exponentially growing young and old fibroblasts were assessed using the cationic dye MitoSOX red (Molecular probes). Following labelling with 2 µM MitoSOX red, the cells were analyzed using LSR violet flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson) (excitation 488 nm, emission 585 nm bandpass filter). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 10,000 cells was analyzed per sample and corrected for autofluorescence from unlabeled cells. Each sample was normalized to the young fibroblasts to yield the normalized mean fluorescence intensity (NMFI).

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Measurement Using JC-1

Membrane potential of young and old fibroblasts was detected by JC-1 fluorescence. JC-1 was used at a final concentration of 3 µM. The mitochondrial ETC uncoupler CCCP (Carbonyl cyanide m-chloro phenyl hydrazone) was used at 50 µM as the negative control. The red and green fluorescence of 10,000 cells was recorded per sample, and the mean of three samples was calculated for each condition. Each sample was normalized to the young fibroblast group, to yield the normalized Red/Green ratio.

Mitochondrial Electron Chain Complex Activities

Measurements of the ETC complex activities were done as described previously (19,20). Whole cell pellets from exponentially growing cultures were disrupted by sonication and freeze thaw. The assays were performed on a Beckman DU 800 spectrophotometer (Brea, CA). Complex I activity was assayed as the rate of rotenone-inhibitable NADH oxidation as described previously (19,20). Complex II activity was assayed as the rate of reduction of 2, 6-dichloroindophenol by coenzyme Q in the presence and absence of 0.2 M succinate as described previously (19,20). Complex III activity was assayed as the rate of cytochrome c reduction by coenzyme Q2 whereas, complex IV activity was assayed as the rate of cytochrome c oxidation (19,20). Complex V activity assay was performed at 340 nm. The activity was measured by using lactate dehydrogenase and pyruvate kinase as the coupling enzymes. All the ETC complex activities were normalized to citrate synthase activity for mitochondrial content.

Citrate Synthase Activity

Cellular citrate synthase activity was measured using the protocol previously described (21). Protein was quantified using the Lowry assay. 50 µg protein was combined with NADP+ oxaloacetic acid (0.5 mM) and dTNB (0.1 mM). Reactions were monitored at 412 nm for the formation of TNB formed every 30 min for 2 mins. Rates were determined from slopes determined by regression analysis of the data.

Aconitase Activity

Total cellular aconitase activity was measured using the protocol previously described (22). Protein was quantified using the Lowry assay (23). Rates were determined from slopes determined by regression analysis of data.

Isolation of RNA from fibroblasts

Total RNA was isolated from exponentially growing young (5 month old donor) and old (78 year old donor) fibroblasts using the RNeasy mini kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA – Cat # 74104). Briefly, cells were trypsinized with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, washed in DPBS and pelleted. The RNA was isolated using the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA concentration and purity in the eluted samples was quantified using a NanoDrop ND-100 UV spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, LLC – Wilmington, DE).

cDNA synthesis

The extracted RNA was converted to cDNA using the RT2 HT first strand kit from Qiagen (cat # 330401). The cDNA was stored at −20°C until used for real-time PCR profiling using the mitochondrial energy metabolism PCR array from Qiagen (# PAHS008Z).

Gene Expression using the mitochondrial energy metabolism PCR array

Differences in the nuclear-encoded genes of the mitochondrial ETC were determined using the RT2 profiler PCR array from Qiagen (Valencia, CA – Cat # PAHS008Z; accession number: GSE100921). Relative gene expression changes and fold changes were determined using the ΔΔCt method as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Fold-change was quantified as the normalized gene expression in the old fibroblasts (ΔΔCtold) divided by the normalized gene expression in the young fibroblasts (ΔΔCtyoung). Fold-change values greater than two were considered positive or up-regulation, whereas fold change values less than −2 indicated negative or down-regulation in gene expression.

Gene expression changes in the mitochondrial-encoded genes of the ETC using QPCR

25 ng cDNA samples from young and old fibroblasts were used to perform the QPCR analyses of the 13 mitochondrially encoded genes of the ETC. Reactions were performed in triplicate for each of the genes. All primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems including the two ribosomal RNAs (RNR1 & 2). QPCR cycle conditions were 2 minutes at 50°C, 10 minutes at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds of denaturation at 95°C and 60 seconds of annealing/extension at 60°C. Fluorescent signal intensity of PCR products was recorded and analyzed on ABI-7900 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the SDS 2.3 software. The threshold cycle or Ct value within the linear exponential phase of the curve was used to calculate the ΔΔCt value. The RNR2 encoded in the mitochondrial DNA was used as housekeeping gene. Fold-change was quantified as the normalized gene expression in fibroblasts from the 78 year old donor (ΔΔCtold) divided by the normalized gene expression in fibroblasts from the 5 month old donor (ΔΔCt young). Fold-change values greater than 1 were considered positive or up-regulation, whereas fold change values less than −1 indicated negative or down-regulation in gene expression.

Assessing DNA damage levels by γ-H2AX

Relative levels of DNA damage were determined using γ-H2AX using both confocal microscopy and flow cytometry (24). For the flow cytometric analysis, briefly, cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS and fixed overnight in 70% ethanol. Following day, the cells were resuspended in cold PBST (PBS-tween) to rehydrate on ice for 10 mins, centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 mins at 4°C and resuspended overnight in rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho H2AX antibody at 1:800 in PBST purchased from Cell signaling technology (Beverly, MA) (Cat # 2577). The cells were then washed with 2% FBS (fetal bovine serum) in PBS and resuspended in a FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody at 1:200 in PBST for an hour at room temperature. Cells were then rinsed with PBS, centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 mins at 4°C, resuspended in fresh PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry using LSR-violet. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 10,000 cells was analyzed per sample and corrected for autofluorescence from unlabeled cells. Each sample was normalized to the control young fibroblasts to yield the normalized mean fluorescence intensity (NMFI).

For analysis by confocal microscopy, cells were plated on Thermo Scientific™ Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ II Chamber Slide™ System from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY (Cat # 154453PK) at least 24 hours before the experiment. Cells were fixed in 4% PFA (Paraformaldehyde) for 15 mins at 37°C, washed with PBS and blocked in 1% donkey serum in TBST for 30 mins at room temperature. Cells were then treated with a mouse monoclonal anti-phospho H2AX antibody at 1:1000 in TBST purchased from Millipore (Cat # 05–636-I) overnight. The following day, the chambers were washed three times with PBST and resuspended in a FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody at 1:200 in PBST for an hour at room temperature for 2 hours. The samples were then washed three times with TBST and confocal analysis was performed. Hoechst was used as a nuclear stain at 1:1000. Samples were scored in a blinded-fashion and an average of at least 150 nuclei was scored from at least 4 randomly selected areas for each group. The fluorescence intensities were quantified using the ImageJ software.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity assay

SOD activity was determined using the indirect competitive inhibition assay as described previously (25). Briefly, the flux of superoxide generated by the reaction of xanthine & xanthine oxidase was measured using nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT). Increasing concentrations of SOD rapidly converts the superoxide produced to hydrogen peroxide and the rate of NBT reduction is inhibited and can be measured spectrophotometrically at 560 nm. The rate of NBT reduction is calculated as percent inhibition, relative to the NBT reduction in the absence of the sample and the amount of protein causing 50% maximum inhibition is defined as one unit of activity. Exponentially growing young and old fibroblasts were washed and scraped in ice cold PBS and spun down. The dry pellets were then resuspended in DETAPAC buffer (0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.8, 1.34 mM DETAPAC) and MnSOD activity was distinguished from CuZSOD activity using 5 mM NaCN as described (25).

Analysis of mitochondrial morphology using TOM20

Exponentially growing young and old fibroblasts were fixed in 4% PFA for 15 mins at 37°C. Cells were washed 3X with TTBS (tris buffered saline containing tween) and then blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in 4% normal donkey serum and TTBS. Cells were then washed 3X in TTBS and incubated in primary antibody (Rb α-TOM20 – an outer mitochondrial membrane protein) overnight at 4°C. The following day, cells were washed 3x in TTBS and incubated with secondary antibody (dnky α-Rb 488) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were incubated in PBS containing Hoechst 33342 (1:1000, 1ug/ml) for 5 minutes at room temperature and then washed 3X with PBS before imaging.

All groups were imaged in a blinded fashion on a Leica DMI4000B epifluorescence microscope with a 100x oil immersion imaging ~50–100 cells/condition. Images were pre-processed and mitochondrial morphology was analyzed using an ImageJ macro as previously described (26,27). Analyses of the mitochondrial morphology were carried out by an observer blinded to conditions. Shape metrics including form factor (perimeter2/ (4 × π × area) and aspect ratio (long axis/short axis of a best fit ellipse) were determined in all groups. Both the shape metrics have a minimum value of 1 for perfect circular mitochondria. All groups were normalized to the young fibroblast control group.

Mouse Tissue Sample Collection and Staining

Skin samples were collected from both IR exposed and control legs of young, adult and old mice through the University of Iowa Comparative Pathology Core. Each skin tissue was equally divided into two parts, one half of which was fixed in formalin while the other half was frozen in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. Compound (Sakura® Finetek, VWR). The formalin fixed tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for determining changes in epidermal and dermal thickness whereas; the samples frozen in O.C.T. were utilized for DHE staining.

Tissue DHE Staining and Quantification

From OCT-frozen mouse skin tissue, 10 µm sections IR exposed skin was cut and placed on the same slide to control skin for that specific group (For e.g. young control vs. young IR). For comparison between different age groups, sections from the same treatment group but different age groups were placed on the same slide (e.g. young IR vs. adult IR) in order to maintain similar experimental labeling conditions. Tissue sections were stained with 10 µM DHE for 10 min at 37°C in PBS containing 5 mM sodium pyruvate prior to analysis by confocal microscopy using the Olympus Fluoview FV1000 confocal microscope. All sections were imaged at 20X magnification, 37°C using Cy3 as the fluorochrome. For treatment groups, tissue sections were pretreated for 30 min with 0.25 µM GC4419 SOD mimetic or, alternatively, as a positive control, tissue sections were treated with 10 µM antimycin A (AntA) and DHE for 10 min. Each image obtained was quantified by measuring the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of at least 150 cell nuclei, and normalized to young mouse control or the respective young treatment group.

Epidermal and dermal thickness

Skin thickness was measured in the tissue slices from young, adult and old mice both from the IR-exposed and control leg. Sections stained with H&E were used to determine differences in epidermal and dermal layers of the skin. Images were generated using the Olympus BX-61 motorized light microscope at 20X magnification and were scored in a blinded fashion. Epidermal and dermal layers were measured using the arbitrary line function which is integrated in the imaging software Cellsens on the same microscope. At least 30 different (randomly selected) areas were sampled for changes in the epidermal and dermal layers of the skin per treatment group.

Cellular Respiration using Clark Electrode

Oxygen consumption was measured using the Clark electrode in young and old fibroblasts as described previously (28). Exponentially growing young and old fibroblasts were plated at 200,000/dish, grown 48 hours, trypsinized, and resuspended in PBS at 37° and O2 consumption monitored for 30 minutes using the Clark electrode.

Steady-state levels of ATP

ATP production was determined using a kit (Promega, CellTiterGlo) by measuring luminescence on a SpectraMax Microplate reader. Briefly, a cell suspension made during exponential growth phase (50,000 cells/100 µL) was used for the kit based assay. Instructions were followed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A standard curve of ATP concentration vs. luminescence signal was generated with adenosine 5’-triphosphate (ATP) disodium salt hydrate (CAS # 34369-07-8, Sigma Aldrich).

Statistics

Statistics were done using the graph pad prism software. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA for non-parametric measurements. Tukey post-hoc test was performed wherever appropriate. Unless specified otherwise in the figure legend, error bars represent ± standard error of mean (SEM) and statistical significance was defined as ** = p < 0.05.

Results

Old fibroblasts have increased steady-state levels of mitochondrial superoxide

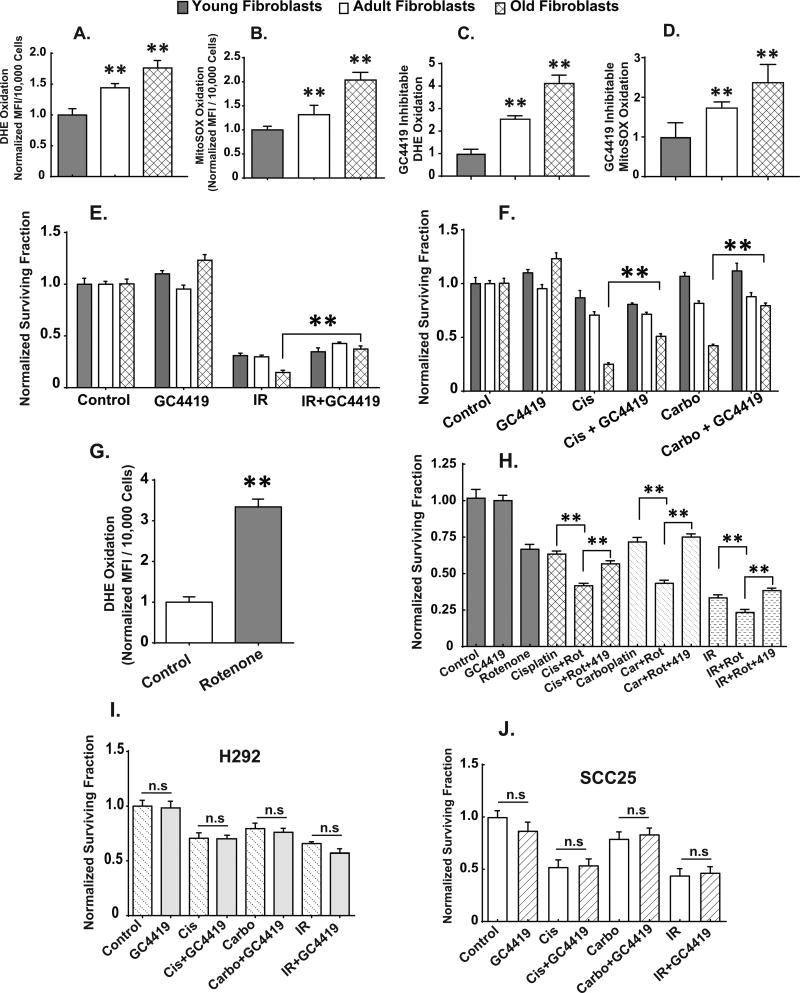

Exponentially growing early passage old fibroblasts demonstrate significantly increased levels of DHE and MitoSOX oxidation relative to young and adult fibroblasts (Figs. 1A and B). In order to confirm that the increased DHE and MitoSOX oxidation in old fibroblasts is caused by an increase in endogenous steady-state levels of O2•−, we utilized the small molecule superoxide specific SOD mimetic, GC4419, developed by Galera Therapeutics Inc., (Supp. Fig. 1A) to inhibit the oxidation of DHE or MitoSOX (16). In the presence of 0.25 µM SOD mimetic, old fibroblasts showed a 4-fold increase in GC4419-inhibitable DHE oxidation (Fig. 1C) and a 3-fold increase in GC4419-inhibitable MitoSOX oxidation (Fig. 1D) clearly demonstrating significantly increased steady-state levels of both cytosolic and mitochondrial superoxide, relative to both young and adult fibroblasts.

Figure 1. Age-associated increases in steady-state levels of superoxide mediate the increased sensitivity of adult and old dermal fibroblasts to radiation and chemotherapy.

Exponentially growing young, adult and old fibroblasts were assayed for DHE (1A) and/or MitoSOX (1B) oxidation in the presence and absence of pretreatment with the superoxide-specific SOD mimetic GC4419 (0.25 µM) or vehicle control for 48 hours. Only the signal that was inhibited by GC4419 is plotted (1C and D) as being indicative of changes in steady-state levels of superoxide. All experiments are N=3 with three technical and biological replicates per group, **=p<0.05 versus young fibroblasts as determined by one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test using GraphPad prism software. Clonogenic cell survival in exponentially growing young, adult and old fibroblasts exposed to 0.25 µM GC4419 48 hours prior to, during and post exposure to radiation (2 Gy X-rays) (1E), cisplatin (0.5 µM for 24 hours) (1F), and carboplatin (2 µM for 24 hours) (1F). Steady-state levels of superoxide in young fibroblasts as determined by DHE oxidation following 24 hour treatment with 0.5 µM rotenone (1G). **=p<0.05 as determined by one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey test vs. control. Rotenone-induced changes in clonogenic cell survival following IR and chemotherapy exposure in young fibroblasts in the presence and absence of 0.25 µM GC4419 for 24 hours before exposure to rotenone and the platinum based chemotherapy drugs (1H). Clonogenic cell survival of H292 (NSCLC) (1I) and SCC25 (head and neck cancer) (1J) exposed to 0.25 µM GC4419 48 hours prior to, during and post radiation, cisplatin and/or carboplatin treatment. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean of N=3 experiments with three technical and biological replicates per group, (n.s) = not significant. Statistical analysis was done using one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test using GraphPad prism.

Enhanced sensitivity of old fibroblasts to chemotherapy and radiation is mediated by superoxide

In vitro, old fibroblasts relative to young fibroblasts demonstrate significantly increased doubling times (Supp. Fig. 1B), decreased ability to undergo population doublings (Supp. Fig. 1C), and decreased plating efficiencies (Supp. Fig. 1D). To determine if there is a difference between young and old fibroblasts in sensitivity to radiation and platinum-based chemotherapy, exponentially growing fibroblasts from young donor male subjects and old donor male subjects were treated with increasing doses of IR or 24 hr exposures to platinum-based chemotherapy and assessed for clonogenic survival. Results indicate that clonogenic survival was significantly reduced in the old fibroblasts relative to the young fibroblasts following treatment with IR or platinum based chemotherapy (Supp. Figs. 1E, 1F and 1G).

When early passage, exponentially growing young, adult and old fibroblasts were exposed to GC4419 (0.25 µM) 24 hours prior to, during, as well as following treatment (in the cloning dishes) with IR and platinum-based chemotherapy, GC4419 was able to significantly protect old fibroblasts, from clonogenic cell killing (Figs. 1E and 1F). Interestingly, no significant differences in clonogenic cell killing were observed in the GC4419-treated young and adult fibroblasts following IR, cisplatin and/or carboplatin treatment, relative to similarly treated cells in the absence of GC4419 (Figs. 1E and 1F).

In order to determine if increasing mitochondrial superoxide could sensitize young fibroblasts to cisplatin, carboplatin, or radiation, young fibroblasts were treated with the electron transport chain blocker, rotenone which is known to increase steady-state levels of mitochondrial superoxide (29,30). Treatment of young fibroblasts with 0.5 µM rotenone for 24 hours led to increased steady-state levels of superoxide as determined by DHE oxidation (Fig. 1G) as well as sensitizing the young fibroblasts to clonogenic cell killing by cisplatin, carboplatin, or IR (Fig. 1H). This rotenone-induced sensitization to IR and chemotherapy was mitigated when the young fibroblasts were treated with 0.25 µM GC4419 before, during, and following exposure to rotenone, IR and the platinum-based chemotherapy drugs (Fig. 1H). These results continue to support the conclusion that young fibroblasts can be sensitized to IR and platinum based chemotherapy by increasing mitochondrial superoxide.

Most importantly, treatment with 0.25 µM GC4419 before, during, and following treatment with IR and platinum-induced killing did not protect exponentially growing human non-small cell lung cancer (H292) or head and neck cancer cells (SCC25) (Figs. 1I and 1J). The ability of GC4419 to selectively protect normal cells from IR and chemotherapy while maintaining tumor cell killing is critical to translating these results.

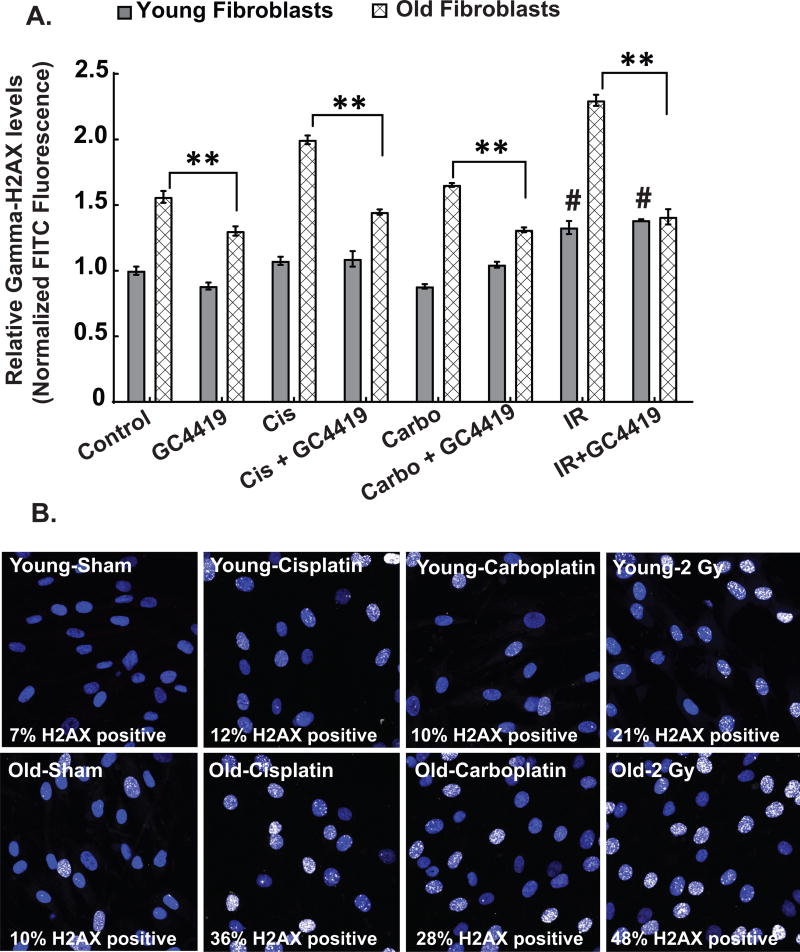

IR and platinum-based chemotherapy-induced DNA damage can be selectively inhibited in fibroblasts by GC4419

Several studies have linked platinum-based chemotherapy agents and IR to DNA damage (31,32). In addition there is a strong mechanistic connection between increased steady-state levels of ROS and DNA damage (8). Consistent with the role of DNA damage in normal tissue injury, exponentially growing old fibroblasts demonstrate increased fluorescence associated with immunoreactive γ-H2AX staining, relative to young fibroblasts that was exacerbated following exposure to IR (1 hr) or platinum-based chemotherapy (24 hr) (Figs. 2A and 2B). More importantly, this increase in fluorescence associated with immunoreactive γ-H2AX staining was partially inhibited by GC4419 (Fig. 2A). These data strongly support the hypothesis that increased sensitivity to IR and platinum based chemotherapy in the old fibroblasts is causally related to increased steady-state levels of O2•− enhancing residual DNA damage. Importantly, GC4419 did not interfere in vitro (Figs. 1G and 1H), or in vivo (33), with the anti-cancer activities of IR or platinum-based chemotherapy.

Figure 2. Age-associated radiation and chemotherapy-induced increased levels of DNA damage are mediated by superoxide.

γ-H2AX levels indicative of DNA damage were measured in young and old fibroblasts using flow cytometry (2A) and/or confocal microscopy (2B) at basal, 60 mins following 2 Gy IR and 24 hours following cisplatin (500 nM) and carboplatin (2µM) exposure. Treatment of exponentially growing cultures of young and old fibroblasts with 0.25 µM of GC4419 for 48 hours suppressed the radiation, cisplatin and carboplatin-induced DNA damage in old fibroblasts (2A). All experiments are N=3 with three technical and biological replicates per group, **=p<0.05 as determined by one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test using GraphPad prism software (flow cytometry) or by using ImageJ to count the γ-H2AX positive cells (white-stained nuclei) for confocal microscopy analysis. #=p<0.05 compared to the young control group. At least 100 cells were counted in each group to get the percentage γ-H2AX positive cells (2B).

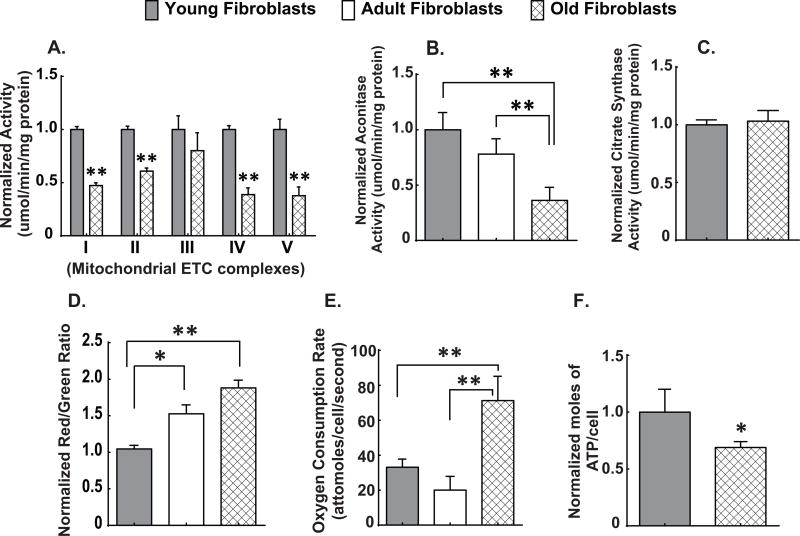

Age-associated alterations in fibroblast mitochondrial oxidative metabolism

Mitochondrial electron transport chains are a major site of O2•− production and disruption of the flow of electrons through ETCs is associated with increased steady-state levels of O2•− (13,14,34,35). Since old fibroblasts have increased steady-state levels of mitochondrial O2•− (Figs. 1A and B), we hypothesized that old fibroblasts would also demonstrate alterations in ETC complex activities. Whole cell homogenates from exponentially growing old fibroblasts demonstrated significantly reduced activities of complex I, II, IV, V (Fig. 3A). Total aconitase activity (normalized to citrate synthase activity) was also significantly decreased in both adult and old fibroblasts relative to young fibroblasts (Fig. 3B). In contrast, there was no significant change in citrate synthase activity, which is a Krebs cycle enzyme used to assess total mitochondrial content (21) (Fig. 3C). Consistent with decreased mitochondrial ETC complex activities and increased levels of O2•− in mitochondria, there was also an increase in mitochondrial membrane potential determined by JC-1 (Fig. 3D), an increase in oxygen consumption (Fig. 3E) and a decrease in steady-state levels of ATP (Fig. 3F) in exponentially growing old fibroblasts, relative to young fibroblasts. These results support the hypothesis that old fibroblasts exhibit significant reductions in mitochondrial metabolic efficiency. Taken together, the results in Figures 1–3 indicate that old fibroblasts (relative to young fibroblasts) demonstrate significant alterations in mitochondrial oxidative metabolism that are accompanied by increased steady-state levels of O2•−, which contribute to differential sensitivity to IR and chemotherapy.

Figure 3. Age-associated disruptions in mitochondrial oxidative metabolism.

Spectrophotometric analysis of mitochondrial ETC complex activities complexes (I–V) (3A) and aconitase activity (3B) as well as citrate synthase activity (3C) in whole cell homogenates of exponentially growing young, adult and old fibroblasts. All values are expressed as normalized activity (umol/min/mg protein). Mitochondrial membrane potential as measured by flow cytometry using JC-1 (3D), oxygen consumption measured using the Clark electrode (3E), and steady-state levels of ATP as measured using a SpectraMax Microplate reader assay (3F). All experiments are N=3 with three technical and biological replicates per group, **=p<0.05 versus young fibroblasts as determined by one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test using GraphPad prism software.

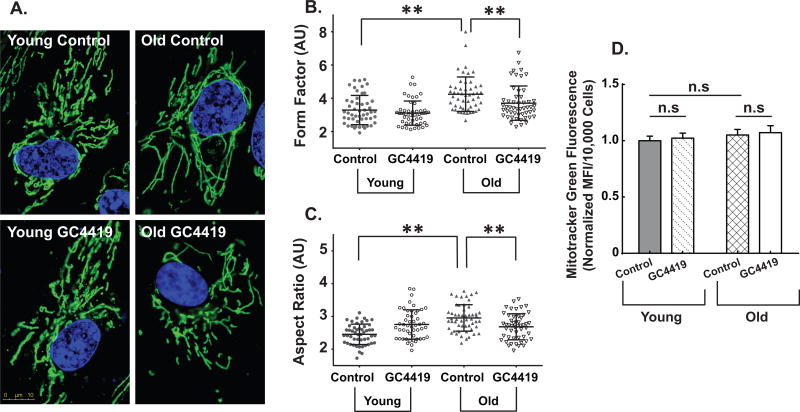

Age-associated changes in mitochondrial morphology and mitochondrial ETC gene expression

Significant age-associated mitochondrial elongation was also noted in exponentially growing old fibroblasts, relative to the young fibroblasts (Fig. 4A). Both mitochondrial form factor (a measure for mitochondrial elongation with a minimum value of 1 for perfectly round mitochondria) (Fig. 4B) and aspect ratio (aspect ratio = major axis/minor axis) (Fig. 4C) were significantly increased in old fibroblasts relative to young fibroblasts. Furthermore, treatment with GC4419 significantly decreased mitochondrial elongation in old fibroblasts making them comparable to young fibroblasts indicating that increased steady-state levels of O2•− mediate the age-associated changes in mitochondrial structure (Figs. 4A, B, and C). In contrast, MitoTracker green levels (a measure of mitochondrial mass) remained unchanged between young and old fibroblasts suggesting no change in overall mitochondrial mass (Fig. 4D). These data support the hypothesis that old fibroblasts undergo changes in mitochondrial morphology to maintain cellular homeostasis and function as well as that O2•− is a mediator of donor age-associated mitochondrial elongation.

Figure 4. Age-associated alterations in mitochondrial morphology are mediated by superoxide.

Mitochondrial morphology in exponentially growing cultures of young and old fibroblasts in the presence and absence of the superoxide-specific SOD mimetic GC4419 (0.25 µM) or vehicle control for 48 hours as assessed by confocal microscopy using the outer mitochondrial protein TOM20 (stained green) and Hoechst 33342 (stained blue for the nucleus) at 100X magnification (4A). Each panel in is a representative image of the respective group (4A). At least 50 cells were quantified from three independent experiments for each group. Mitochondrial morphology was quantified using form factor (4B) and aspect ratio (4C) by FIJI software as described previously by (50,51). Assessment of mitochondrial mass both at basal as well as following treatment with 0.25 µM GC4419 using MitoTracker Green (MTG) (4D). All experiments are N=3 with three technical and biological replicates per group, **=p<0.05 as determined by one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test using GraphPad prism software.

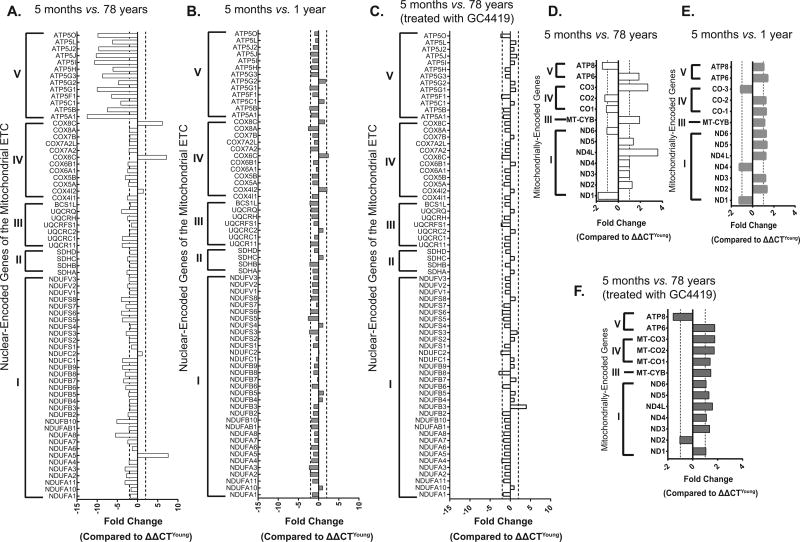

In addition to changes in mitochondrial morphology, exponentially growing fibroblasts from elderly donor patients also showed changes in the stoichiometry of ETC complex gene expression as demonstrated by QPCR arrays performed on both nuclear as well as mitochondrial-encoded genes comparing young (5 month old donor) and old (78 year old donor) fibroblasts. Relative to young fibroblasts (5 month old donor), the old fibroblasts (78 year old donor) demonstrated an age-associated ≥ 2-fold change in expression of 48 nuclear encoded ETC genes (Fig. 5A). In contrast there were only twelve genes that showed a ≥ 2-fold change in the nuclear encoded ETC gene expression between two different young fibroblasts (comparing 5 month old and 1 year old donors) (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, pre-treatment of exponentially growing young and old fibroblasts with GC4419 was able to reduce the number of nuclear genes that demonstrated ≥ 2-fold changes in expression from 48 to 12 (Fig. 5C). Consistent with changes in nuclear encoded ETC genes, old fibroblasts (78 year old donor) demonstrated an age-associated ≥ 2-fold change in expression of two mitochondrial encoded ETC genes (Fig. 5D) while the mitochondrial gene expression between fibroblasts from two young donors (comparing 5 months old to 1 year old) showed no ≥ 2 fold changes (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, pre-treatment of exponentially growing young and old fibroblasts with GC4419 showed no ≥ 2-fold changes in expression of mitochondrial encoded ETC genes (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5. Age-associated alterations in mitochondrial ETC gene expression can be mitigated by GC4419.

Age-associated changes in gene expression of nuclear encoded ETC genes (≥ 2-fold change considered significant) comparing young (5 month old) and old (78 year old donor) fibroblasts (5A) as well as two different young fibroblasts (5 month old and 1 year old donor) (5B). Changes in nuclear-encoded gene expression comparing young (5 month old) and old (78 year old donor) fibroblasts are mitigated following 72 hours treatment with 0.25 µM GC4419 (5C). Changes in gene expression of mitochondrially-encoded ETC genes (≥ a fold change considered significant) comparing young (5 month old) and old (78 year old donor) fibroblasts (5D), two different young fibroblasts (5 month old and 1 year old donor) (5E) and comparing young (5 month old) and old (78 year old donor) fibroblasts following 72 hrs treatment with 0.25 µM GC4419 (5F). The QPCR analyses used 18S or 2RNR for normalization in the nuclear encoded and mitochondrially encoded gene arrays respectively.

Taken together the results in Figures 4 and 5 indicate that structural changes as well as alterations in the stoichiometry of ETC gene expression occur in old fibroblasts (relative to young fibroblasts) that could be related to differences in mitochondrial function and may be also be related to increased steady-state levels of O2•−.

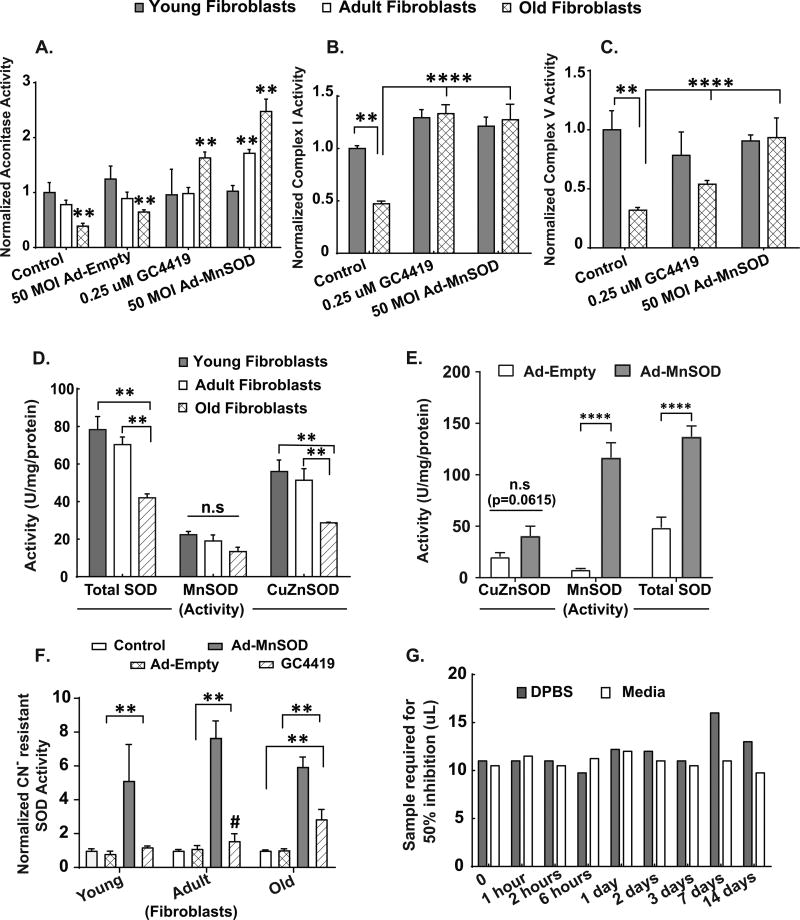

Superoxide mediates alterations in mitochondrial ETC activities

To determine if increased steady-state levels of O2•− could be linked to age-associated changes in mitochondrial metabolism, old fibroblasts were treated with the SOD mimetic, GC4419, or transduced to increase mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase activity (aka, SOD2) using an adenoviral vector (Ad-MnSOD) followed by analysis of aconitase, complex I, and complex V activity (Figs. 6A, 6B and 6C). Interestingly, basal levels of total SOD and CuZnSOD activity showed a significant age-associated decrease in the adult and old fibroblasts relative to the young fibroblasts (Fig. 6D). However, there was no significant difference in CuZnSOD activity of old fibroblasts treated with either 50 MOI Ad-Empty or Ad-MnSOD (Fig. 6E). Treatment of young, adult and old fibroblasts with 50 MOI Ad-MnSOD or 0.25 µM GC4419 resulted in significantly increased cyanide-resistant SOD activity, relative to Ad-Empty vector or vehicle control (Fig. 6F). Both in the adult and old fibroblasts (but not in the young fibroblasts), the increase in cyanide-resistant SOD activity was able to significantly increase the activity of aconitase relative to vector control (Fig. 6A). In addition, overexpression of MnSOD also significantly increased ETC complex I (Fig. 6B) and complex V (Fig. 6C) activities, relative to vector control. Likewise, treatment of old fibroblasts with SOD mimic (GC4419) also significantly increased the activity of aconitase (Fig. 6A), ETC complex I (Fig. 6B) and complex V (Fig. 6C), relative to these activities in vehicle control fibroblasts. Furthermore, the SOD activity of GC4419 was retained in full media and in DPBS for 2 weeks at 37°C in a tissue culture incubator (Fig. 6G) demonstrating the stability of SOD activity in these model systems. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence for the hypothesis that increases in O2•− mediate the age-associated alterations in structure as well as function of mitochondrial ETC and TCA cycle proteins.

Figure 6. Mitochondrial superoxide mediates the age-associated decrease in aconitase, complex I and complex V activities.

Following 48 hours treatment of exponentially growing young, adult and old fibroblasts with vehicle control, 0.25 µM GC4419 or 50 MOI of Ad-MnSOD and Ad-Empty, biochemical activity assays for aconitase (6A), Complex I (6B) and Complex V (6C) were performed on whole cell homogenates. Values in (6A, B and C) are expressed as activity (umol/min/mg protein), normalized to the young control group in each panel. Age-associated changes in endogenous SOD activity (Total, MnSOD and CuZnSOD) in exponentially growing young, adult and old fibroblasts (6D) using the SOD assay as described previously (49). (6E) shows changes in SOD activity (CuZnSOD, MnSOD and Total) in exponentially growing dermal fibroblasts from older patients treated with 50 MOI of Ad-MnSOD or Ad-Empty. Values in (6D) and (6E) are expressed as (U/mg protein), normalized to the young control group. (6F) shows changes in Cyanide (CN-) resistant SOD activity in exponentially growing young, adult and old dermal fibroblasts treated with either 50 MOI of Ad-MnSOD or Ad-Empty or 0.25 uM GC4419. SOD activity of GC4419 was retained in full media and in DPBS for 2 weeks at 37°C in a tissue culture incubator (6G) demonstrating the stability of SOD activity. Data plotted in (6G) shows the amount of sample solution required for 50% of maximum inhibition of NBT reduction (49). All experiments are N=3 with three technical and biological replicates per group, **=p<0.05 as compared to the respective young fibroblast group (or as indicated), **** = p<0.001 determined by one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test using GraphPad prism software.

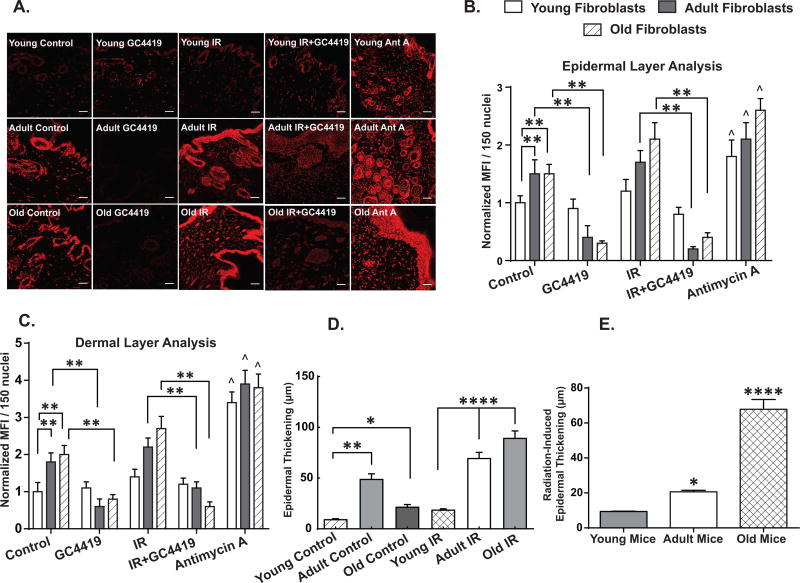

In vivo DHE oxidation and morphological changes in mouse skin following IR

A previously described (36) model of IR-induced cutaneous right hind limb skin injury induced by a single fraction of 45 Gy was delivered to four young (2 months), three adult (7 months) and three old (31 months) C57BL/6J male mice. Skin samples from the irradiated and contralateral unexposed leg, were collected 6 weeks following IR and analyzed for fibrosis as well as oxidative stress markers. Two of the three old mice died within two weeks of IR treatment, while none of the young or adult mice demonstrated mortality. There were no changes in behavior or feeding observed in the 6 weeks following IR exposure in the surviving animals. Skin samples from both adult and old mice showed an increase in basal levels of DHE oxidation relative to young mice (Fig. 7A) in both the dermis (Fig. 7B) and epidermis (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, these increases in basal DHE oxidation in the adult and old mouse skin were significantly attenuated when the sections were treated with GC4419 prior to DHE staining, both in the dermis (Fig. 7B) and the epidermis (Fig. 7C) compared to the young mice. In addition, skin samples from irradiated adult and old mice also showed a significant 2–3 fold increase in DHE oxidation levels in comparison to skin samples from irradiated young mice (Fig. 7A) in both the dermis and epidermis (Figs. 7B and C), the majority of which were inhibited by GC4419 suggesting a causal role for O2•− in the changes in DHE oxidation. No significant change in DHE oxidation was observed in skin samples from the irradiated leg of young mice relative to the skin samples from the un-irradiated leg of the same mice. The increases in DHE oxidation at baseline and following IR exposure in the adult and old mice were accompanied by a significant increase in IR-induced epidermal thickening (Figs. 7D and 7E). These results, combined with the in vitro data (Fig. 1), support the hypothesis that changes in steady-state levels of O2•− could contribute to age-associated skin damage and fibrosis following IR exposure.

Figure 7. Increased IR-induced skin injury in adult and old animals correlated positively with increased GC4419 inhibitable DHE oxidation.

Basal as well as IR-induced DHE oxidation levels in young mice (4 months), adult (9 months) and old (33 months) in the presence or absence of 0.25 µM GC4419 as measured by confocal microscopy at 20X magnification (7A). Scale bar=100 µm. At least 150 nuclei from three independent tissue sections were quantified in a blinded fashion (see methods for details) for each group. Antimycin A was used as a positive control at 10 µM. Quantification of the changes in DHE oxidation levels in both the dermal (7B) as well as the epidermal layers (7C) of mouse skin as normalized to the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of young control group ± SEM. Quantification of endogenous and IR-induced epidermal thickness in the skin samples of young, adult and old mice as analyzed by light microscopy (7D). At least 30 measurements were performed in a blinded fashion on three independent tissue slices per group. The IR-induced changes in epidermal thickening were determined by subtracting the control skin epidermal thickness from the IR-induced thickness of the young, adult and old mice (7E).*=p<0.05, **=p<0.01 and **** = p<0.0001 as compared to young mice, ^=p<0.05 compared to respective control group and as determined by one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey test.

Discussion

Progressive deterioration of mitochondrial function and structure leading to increased steady-state levels of superoxide have been implicated in the degenerative processes associated with aging and onset of cancer as well as the persistent normal tissue injury processes initiated by radiation exposure (7,37–40). However clear demonstrations of specific changes in mitochondrial function and structure leading to the mechanisms underlying increased levels of superoxide and how these changes might contribute to the enhanced normal tissue injury seen in older patients treated with radiation and chemotherapy are lacking (2,3). In addition, mitochondrial fidelity proteins including the sirtuins and several cell-cycle regulatory proteins including p21, p53 and p16INK4A have been shown to govern the process of aging via a mechanism that involves modulation of ROS levels (6,41–43).

In the current study, we demonstrate in exponentially growing normal human dermal fibroblasts that age-associated changes in mitochondrial structure, function, and electron transport chain complex (ETC) activity as well as differential sensitivity to IR and chemotherapy are mediated by increased steady-state levels of mitochondrial O2•−. It has been suggested that aging associated changes in the stoichiometry of ETC protein complexes could change the residence time of electrons at sites accessible to O2 leading to increased one electron reductions of O2 to form superoxide (7). The data in Figures 3 through 6 clearly show on a global level that the stoichiometry of both the activities and expression of genes coding for ETC proteins demonstrate age associated changes that could potentially contribute to increased steady-state levels of superoxide as well as the structural and functional changes seen in mitochondria.

Advanced age is a clinical factor associated with the severity of radiation-induced skin reaction independent of total radiation dose or dose rate (44). In addition, age-associated increased sensitivity to radiation in the skin has been proposed to be related to decreased epidermal turnover, mitosis, malnutrition, or obesity (45) and thus may not be related to the phenomenon being described in this manuscript.

A detailed mechanistic understanding of the role that metabolic production of O2•− plays in the differential toxicity seen in elderly human cells exposed to chemo-radiation could provide a clear biochemical rationale for the development of agents that protect normal tissues from elderly patients during cancer therapy. Using this rationale, we predicted that reducing O2•− levels and maintaining the integrity of DNA in the face of metabolic oxidative stress induced by chemo-radiation could enhance protection of normal human dermal fibroblasts from older subjects. Previous studies have suggested age-associated increased levels of oxidative damage to proteins (46–48) and DNA could potentially contribute to sensitivity to therapy in elderly cancer patients (12,49) but no direct invovlement of superoxide or mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in these processes has been demonstrated. The current study extends these observations and provides strong proof of concept support for the hypothesis that age-associated differences in mitochondrial oxidative metabolism leading to increased steady-state levels of O2•− mediate the age-associated differential susceptibility of human dermal fibroblasts to IR and chemotherapy. Furthermore, the current study also shows that a small molecule SOD mimetic, GC4419, is able to restore metabolic activity and reduce susceptibility to platinum-based chemotherapy, as well as IR injury in fibroblasts from elderly subjects relative to those from young subjects. GC4419 was also able to significantly ameliorate the IR-induced increases in steady-state levels of O2•− in aging skin both in the presence and absence of IR exposure. Importantly, GC4419 did not inhibit human cancer cell killing mediated by IR or platinum-based chemotherapies. The current study supports the hypothesis that a clear mechanistic understanding of the relationship between mitochondrial O2•− metabolism, aging, and cancer therapy response outcomes may provide a useful tool for the protection of normal tissues during combined modality therapies in elderly cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Flow Cytometry Facility as well as the Radiation and Free Radical Research Core for support of these studies. The authors would like to thank Amanda Kalen and Dr. Michael L. McCormick from the Radiation and Free Radical Research Core at the University of Iowa for assistance with irradiations and spectrophotometric assays respectively. The authors would also like to thank Katherine N. Gibson-Corley from the Comparative Pathology Laboratory (CPL) in the Department of Pathology at the University of Iowa for her assistance in processing skin samples from untreated and irradiated mice. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Zita Sibenaller and Timothy Waldron for assistance in the lab and mouse irradiation experiments, respectively. The authors would also like to thank Brett Wagner and Dr. Claire Doskey for helpful advice with Clark electrode and ATP assays respectively. The authors thank Dr. Robert Beardsley and Dr. Jeffery Keene, of Galera Therapeutics, Inc. for their thoughtful review and comments on this manuscript and Gareth Smith for assistance with graphics.

Financial Support Details: This research was also supported in part by the NIH grant P30CA086862 (D.R. Spitz) as well as R01CA111365 (P.C. Goswami), R01NS056244 (S. Strack), T32 CA078586 (D.R. Spitz), and R01CA182804 (D.R. Spitz). This work was also supported in part by ASTRO JF2014-1 (B.G. Allen), a Medical Research Initiative Grant from the Carver Trust (B. G. Allen), The Carver Research Program of Excellence in Redox Biology and Medicine (D.R. Spitz), and the Department of Radiation Oncology at the University of Iowa.

List of Abbreviations

- Ant A

Antimycin A

- ATP

Adenosine Triphosphate

- BSA

Bovine Serum Albumin

- CDCFH2

5-(and-6)-carboxy-2’,7’- dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- DCIP

2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol

- DHE

Dihydroethidium

- DPBS

Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline

- DT

Doubling Time

- ETC

Electron Transport Chain

- FBS

Fetal Bovine Serum

- Gy

Gray

- IR

Ionizing Radiation

- MFI

Mean Fluorescence Intensity

- MnSOD/SOD2

Manganese Superoxide Dismutase

- NAD

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide

- NBT

Nitroblue Tetrazolium

- O2•−

Superoxide

- OCR

Oxygen Consumption Rate

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- Rot

Rotenone

- SOD

Superoxide Dismutase

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: DPR is an employee of Galera Therapeutics Inc. The remaining authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jing W, Zhu H, Guo H, Zhang Y, Shi F, Han A, et al. Feasibility of elective nodal irradiation (ENI) and involved field irradiation (IFI) in radiotherapy for the elderly patients (Aged >/= 70 Years) with esophageal squamous cell cancer: a retrospective analysis from a single institute. PloS One. 2015;10:e0143007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wedding U, Honecker F, Bokemeyer C, Pientka L, Hoffken K. Tolerance to chemotherapy in elderly patients with cancer. Cancer Control: Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2007;14:44–56. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornu M, Albert V, Hall MN. mTOR in aging, metabolism, and cancer. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2013;23:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suliman HB, Piantadosi CA. Mitochondrial quality control as a therapeutic target. Pharmacological Reviews. 2016;68:20–48. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park SH, Ozden O, Jiang H, Cha YI, Pennington JD, et al. Sirt3, mitochondrial ROS, ageing, and carcinogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2011;12:6226–6239. doi: 10.3390/ijms12096226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spitz DR, Azzam EI, Li JJ, Gius D. Metabolic oxidation/reduction reactions and cellular responses to ionizing radiation: a unifying concept in stress response biology. Cancer Metastasis Reviews. 2004;23:311–322. doi: 10.1023/B:CANC.0000031769.14728.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weyemi U, Redon CE, Aziz T, Choudhuri R, Maeda D, Parekh PR, et al. Inactivation of NADPH oxidases NOX4 and NOX5 protects human primary fibroblasts from ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage. Radiation Research. 2015;183:262–270. doi: 10.1667/RR13799.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brand RM, Epperly MW, Stottlemyer JM, Skoda EM, Gao X, Li S, et al. A topical mitochondria-targeted redox-cycling nitroxide mitigates oxidative stress-induced skin damage. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doctrow SR, Lopez A, Schock AM, Duncan NE, Jourdan MM, Olasz EB, et al. A synthetic superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic EUK-207 mitigates radiation dermatitis and promotes wound healing in irradiated rat skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1088–1096. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boveris A. Mitochondrial production of superoxide radical and hydrogen peroxide. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1977;78:67–82. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9035-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton ML, Van Remmen H, Drake JA, Yang H, Guo ZM, Kewitt K, et al. Does oxidative damage to DNA increase with age? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:10469–10474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171202698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slane BG, Aykin-Burns N, Smith BJ, Kalen AL, Goswami PC, Domann FE, Spitz DR. Mutation of succinate dehydrogenase subunit C results in increased O2•−, oxidative stress, and genomic instability. Cancer Research. 2006;66:7615–7620. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dayal D, Martin SM, Owens KM, Aykin-Burns N, Zhu Y, Boominathan A, et al. Mitochondrial complex II dysfunction can contribute significantly to genomic instability after exposure to ionizing radiation. Radiation Research. 2009;172:737–745. doi: 10.1667/RR1617.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikhed Y, Daiber A, Steven S. Mitochondrial oxidative stress, mitochondrial DNA damage and their role in age-related vascular dysfunction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015;16:15918–15953. doi: 10.3390/ijms160715918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuder RM, Zhen L, Cho CY, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Kasahara Y, Salvemini D, et al. Oxidative stress and apoptosis interact and cause emphysema due to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor blockade. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2003;29:88–97. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0228OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forman HJ, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: a comparison of rate constants. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1973;158:396–400. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(73)90636-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:2315–2319. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birch-Machin MA, Briggs HL, Saborido AA, Bindoff LA, Turnbull DM. An evaluation of the measurement of the activities of complexes I-IV in the respiratory chain of human skeletal muscle mitochondria. Biochemical Medicine and Metabolic Biology. 1994;51:35–42. doi: 10.1006/bmmb.1994.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pullman ME, Penefsky HS, Datta A, Racker E. Partial resolution of the enzymes catalyzing oxidative phosphorylation. I. Purification and properties of soluble dinitrophenol-stimulated adenosine triphosphatase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1960;235:3322–3329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrientos A. In vivo and in organello assessment of OXPHOS activities. Methods. 2002;26:307–316. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morton RL, Ikle D, White CW. Loss of lung mitochondrial aconitase activity due to hyperoxia in bronchopulmonary dysplasia in primates. The American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:L127–133. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.1.L127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo LJ, Yang LX. Gamma-H2AX - a novel biomarker for DNA double-strand breaks. In Vivo. 2008;22:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitz DR, Oberley LW. An assay for superoxide dismutase activity in mammalian tissue homogenates. Analytical Biochemistry. 1989;179:8–18. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cribbs JT, Strack S. Functional characterization of phosphorylation sites in dynamin-related protein 1. Methods in Enzymology. 2009;457:231–253. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)05013-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strack S, Cribbs JT. Allosteric modulation of Drp1 mechanoenzyme assembly and mitochondrial fission by the variable domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:10990–11001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.342105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark LC, Wolf R, Granger D, Taylor Z. Continuous recording of blood oxygen tensions by polarography. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1953;6:189–193. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1953.6.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koopman WJ, Verkaart S, Visch HJ, van der Westhuizen FH, Murphy MP, van den Heuvel LW, et al. Inhibition of complex I of the electron transport chain causes O2•−-mediated mitochondrial outgrowth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C1440–1450. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00607.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koopman WJ, Nijtmans LG, Dieteren CE, Roestenberg P, Valsecchi F, Smeitink JA, Willems PH. Mammalian mitochondrial complex I: biogenesis, regulation, and reactive oxygen species generation. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2010;12:1431–1470. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2014;740:364–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vignard J, Mirey G, Salles B. Ionizing-radiation induced DNA double-strand breaks: a direct and indirect lighting up. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2013;108:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sishc BD, Ramnarain D, Eluru S, Saha D, Story M. Superoxide dismutase mimetic GC4419 protects against radiation induced lung fibrosis, exhibits anti-tumor effects, and enhances radiation induced cell killing. Innovations in Cancer Prevention and Research IV, Austin, Texas. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Treberg JR, Quinlan CL, Brand MD. Evidence for two sites of superoxide production by mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:27103–27110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.252502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quinlan CL, Orr AL, Perevoshchikova IV, Treberg JR, Ackrell B, Brand MD. Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:27255–27264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thanik VD, Chang CC, Zoumalan RA, Lerman OZ, Allen RJ, Nguyen PD, et al. A novel mouse model of cutaneous radiation injury. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;127:560–568. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181fed4f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gruber J, Schaffer S, Halliwell B. The mitochondrial free radical theory of ageing-where do we stand? Front Biosci. 2008;13:6554–6579. doi: 10.2741/3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harman D. The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1972;20:145–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clutton SM, Townsend KM, Walker C, Ansell JD, Wright EG. Radiation-induced genomic instability and persisting oxidative stress in primary bone marrow cultures. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:1633–1639. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.8.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberger JS, Epperly MW. Antioxidant gene therapeutic approaches to normal tissue radioprotection and tumor radiosensitization. In Vivo. 2007;21:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ressler S, Bartkova J, Niederegger H, Bartek J, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Jansen-Durr P, Wlaschek M. p16INK4A is a robust in vivo biomarker of cellular aging in human skin. Aging Cell. 2006;5:379–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu D, Xu Y. p53, oxidative stress, and aging. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2011;15:1669–1678. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davalli P, Mitic T, Caporali A, Lauriola A, D’Arca D. (2016) ROS, Cell Senescence, and Novel Molecular Mechanisms in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:3565127. doi: 10.1155/2016/3565127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Denham JW, Hamilton CS, Simpson SA, Ostwald PM, O’Brien M, Kron T, et al. Factors influencing the degree of erythematous skin reactions in humans. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 1995;36:107–120. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(95)01599-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porock D. Factors influencing the severity of radiation skin and oral mucosal reactions: development of a conceptual framework. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2002;11:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nuss JE, Amaning JK, Bailey CE, DeFord JH, Dimayuga VL, Rabek JP, Papaconstantinou J. Oxidative modification and aggregation of creatine kinase from aged mouse skeletal muscle. Aging. 2009;1:557–572. doi: 10.18632/aging.100055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stadtman ER. Role of oxidant species in aging. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;11:1105–1112. doi: 10.2174/0929867043365341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harman D. The free radical theory of aging. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2003;5:557–561. doi: 10.1089/152308603770310202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoeijmakers JH. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:1475–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.