Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurobehavioral condition in childhood that often persists into adulthood.1 Psychostimulant medication has demonstrated efficacy for managing ADHD symptoms in adults2,3

The development of formulations with varying durations of effect has greatly expanded the available treatment options for individuals with ADHD.4 Management of ADHD symptoms in adults may involve treatment with either short-acting (SA) medication, long-acting (LA) medication, or an adjunctive LA + SA (AU) medication regimen. These different formulation dosing regimens provide differing durations of effect and thus differing coverage of symptoms that can impair adult patients in their social, work, school, and/or family settings across the entire day (in early morning, late afternoon, and into the evening)

Few studies, however, have investigated how LA/SA formulations and differing formulation dosing regimens relate to differing medication coverage resulting in symptom impairments in adult patients with ADHD5,6

Objective

The objective of this study is to assess the relationship between unmet daily symptom coverage needs and LA vs. SA vs. AU formulation dosing regimens of adults with ADHD

Methods

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted among adults with ADHD who had been taking prescription psychostimulant medication for treatment of ADHD symptoms

The online survey was developed following a series of qualitative interviews with adults who have ADHD (n = 31) to understand symptoms and life challenges/impairments particular to ADHD. After providing consent, the participants were interviewed by a trained interviewer who used a semistructured interview guide to elicit information regarding the patients’ experiences with ADHD, focusing on identifying burdensome symptom impairments and unmet symptom treatment needs. A draft survey was then tested on a small sample of adults with ADHD (n = 5) using cognitive interviewing methodology, and the content of the survey was finalized based on the feedback received

Participant selection

Participants were recruited in the United States through research participant panels according to the IRB- approved protocol

Participants were eligible for inclusion in the study if all of the following criteria were present at the time of screening:

Online Survey

Participants completed an online survey that lasted approximately 30 minutes. The survey asked questions relating to the participants’ experiences with ADHD treatment and their everyday activities, as well as sociodemographic and clinical questions. All participants provided informed consent and were compensated for their participation

Data Analysis

-

Survey respondents were stratified according to their current treatment:

○ patients receiving short-acting (SA) medication ≤2 times a day (SA group)

○ patients receiving long-acting (LA) medication once a day (LA group)

○ patients who augmented treatment by receiving more than one medication throughout the day, i.e., LA medication more than once a day; LA plus SA medication; or SA medication more than twice a day (AU group)

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each survey question: mean with standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed continuous data; median with range and/or interquartile range for non-normally distributed continuous data; frequency with percentages for categorical data

The statistical significance of differences between subgroups was assessed using independent sample t-tests or Mann-Whitney tests for comparing normally and non-normally distributed continuous data, respectively, between two groups; analysis of variance (ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey tests for pairwise comparisons) and Kruskal-Wallis tests for comparing scores between three or more groups; and chi-squared tests to compare categorical data. Statistical significance was set at the 5% level (P < 0.05)

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 616 treated ADHD participants completed the online survey (SA: 27% [n = 166]; LA: 33% [n = 201]; AU: 40% [n = 249]). The mean (SD) age of all participants was 39.0 (12.4) years and the majority were female (70%), 452 participants (88%) were currently working, and 129 (21%) were currently attending school or taking classes (Table 2)

The distribution of self-reported ADHD severity and the number of comorbidities were similar across the current medication groups, except that participants in the AU medication group were less likely, and those in the LA group more likely, to report having “moderate” ADHD severity (P < 0.005)

TABLE 2. PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS OVERALL AND BY MEDICATION GROUP.

| AH ADHD (N = 616) | SHORT-ACTING (N = 166) | LONG-ACTING (N = 201) | AUGMENTERS (N = 249) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 39.0 (12.4) | 38.8 (13.2) | 40.0 (13.3) | 38.5 (11.1) |

| Range | 18–74 | 19–70 | 18–74 | 18–67 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 183 (29.7) | 44 (26.5) | 52 (25.9) | 87 (34.9) |

| Female | 433 (70.3) | 122 (73.5) | 149 (74.1) | 162 (65.1) |

| Racial background, n (%) | ||||

| White | 551 (89.4) | 154 (92.8) | 183 (91.0) | 214 (85.9) |

| Other | 65 (10.6) | 12 (7.2) | 18 (9.0) | 35 (14.1) |

| Relationship status, n (%) | ||||

| Married or living with a partner | 338 (54.9) | 88 (53.0) | 111 (55.2) | 139 (55.8) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Employed, full time | 349 (56.7) | 96 (57.8) | 107 (53.2) | 146 (58.6) |

| Employed, part time | 66 (10.7) | 17 (10.2) | 20 (10.0) | 29 (11.6) |

| Self-employed | 37 (6.0) | 13 (7.8) | 7 (3.5) | 17 (6.8) |

| Student | 32 (5.2) | 8 (4.8) | 12 (6.0) | 12 (4.8) |

| Stay-at-home parent/homemaker | 33 (5.4) | 2 (1.2) | 18 (9.0) | 13 (5.2) |

| Unemployed | 24 (3.9) | 6 (3.6) | 14 (7.0) | 4 (1.6) |

| Retired | 27 (4.4) | 9 (5.4) | 12 (6.0) | 6 (2.4) |

| Disabled | 48 (7.8) | 15 (9.0) | 11 (5.5) | 22 (8.8) |

| Currently attending school/ taking classes, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 129 (20.9) | 35 (21.1) | 36 (17.9) | 58 (23.3) |

| No | 487 (79.1) | 131 (78.9) | 165 (82.1) | 191 (76.7) |

| Self-reported ADHD severity, n (%) | ||||

| Very mild | 28 (4.5) | 4 (2.4) | 4 (2.0) | 20 (8.0)* |

| Mild | 94 (15.3) | 27 (16.3) | 29 (14.4) | 38 (15.3) |

| Moderate | 338 (54.9) | 94 (56.6) | 126 (62.7) | 118 (47.4) |

| Severe | 128 (20.8) | 33 (19.9) | 35 (17.4) | 60 (24.1) |

| Very severe | 28 (4.5) | 8 (4.8) | 7 (3.5) | 13 (5.2) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.8 (14.6) | 28.9 (15.5) | 28.4 (15.5) | 26.7 (13.3) |

| Range | 0–69 | 2–62 | 3–69 | 0–60 |

| Number of comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| None | 209 (33.9) | 60 (36.1) | 73 (36.3) | 76 (30.5) |

| One | 159 (25.8) | 44 (26.5) | 42 (20.9) | 73 (29.3) |

| Two | 138 (22.4) | 37 (22.3) | 50 (24.9) | 51 (20.5) |

| Three or more | 110 (17.9) | 25 (15.1) | 36 (17.9) | 49 (19.7) |

Note: *P < 0.05,

**P < 0.001 group comparison.

Abbreviations: ADHD, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Medication Experience Related to Duration of Effect

-

Duration of effect was among the top 3 most commonly reported reasons for choosing current treatment. Only doctor’s recommendation differed between the medication groups:

○ Doctor’s recommendation: n = 367, 60% (LA 68% [n = 136]: SA 59% [n = 98]; AU 53% [n = 133]; P < 0.01)

○ Insurance coverage: 48% [n = 298]

○ Duration of effect: 44% [n = 268]

○ Treatment regimen (e.g., dosing frequency or regimen difficulty, etc.): 42% [n = 258]

-

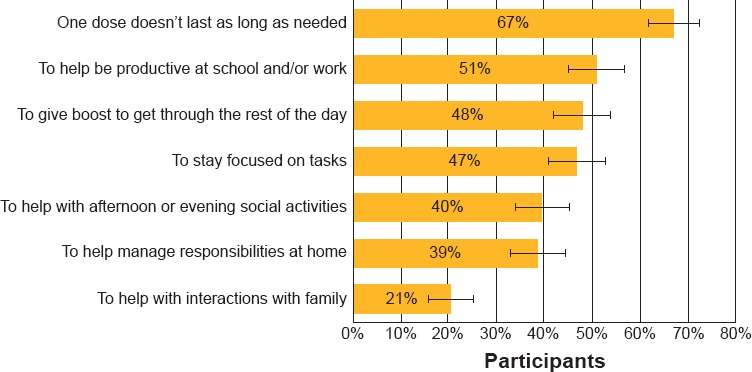

“Duration of effect” was a key factor driving the AU group’s choice to take more than one medication. The most commonly reported reasons for augmenting (Figure 1) were:

○ One dose doesn’t last as long as needed: 67% [n = 50]

○ Helps being productive at work/school: 51% [n = 38]

○ Gives the boost needed to get through the rest of the day: 48% [n = 36]

-

Duration of effect was an important medication characteristic for many patients, influencing their likes and dislikes of their current medication and their ideal medication

○ A majority of respondents (56%) indicated that an ideal medication would last all day, with 27% of respondents reporting that their current medication does not last long enough, and 42% that they have to plan activities around their medication wearing off (Table 3). The need to plan activities was most commonly related to social (53%) and work-related activities (53%)

Respondents in the LA group were most likely to indicate wanting a medication that lasts all day and to report liking how long their medication lasts. However, 34% reported having to plan activities around their medication wearing off

Figure 1.

Reasons for Participants (n = 75) Augmenting Medication

TABLE 3. MEDICATION CHARACTERISTICS RELATED TO DURATION OF EFFECT, OVERALL AND BY MEDICATION GROUP.

| ALL ADHD (N = 616) | SHORT-ACTING (N = 166) | LONG-ACTING (N = 201) | AUGMENTERS (N = 249) | P VALUE SHORT-ACTING VS. LONG-ACTING | P VALUE SHORT-ACTING VS. AUGMENTERS | P VALUE LONG-ACTING VS. AUGMENTERS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Like how long current medication lasts, n (%) | 277 (45.0) | 27 (16.2) | 122 (60.7) | 128 (51.4)† | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.05 |

| Dislike that current medication doesn’t last long enough, n (%) | 164 (26.6) | 34 (20.4) | 19 (9.5) | 111 (44.6)† | <0.01 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Ideal medication would last all day, n (%) | 344 (55.8) | 77 (46.4) | 127 (63.2) | 140 (56.2) | <0.01 | <0.05 | NS |

| Have to plan activities around meds wearing off, n (%) | 257 (41.7) | 64 (38.6) | 69 (34.3) | 124 (49.8) | NS | NS | <0.01 |

Note: †Asked separately for each current medication.

Abbreviation: NS, non-significant.

Medication Wearing Off

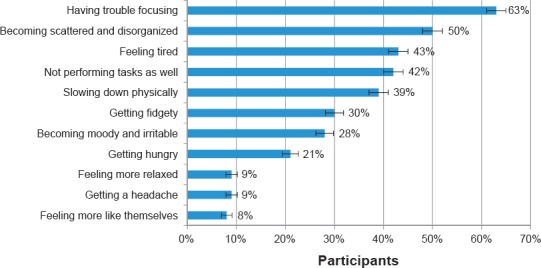

When asked how they noticed that their medication was wearing off, the participants indicated that they experienced a number of symptoms, with 45% [n = 278] of participants indicating they experienced four or more impacts (Figure 2). A minority of participants (7% [n = 42]) could not tell when their medication was wearing off

Figure 2.

Impacts Noticed by Participants When their Medication was Wearing Off

Impact of Medication Wearing Off

Participants commonly noted that the wearing off of their medication had negative effects on various aspects of everyday life, including their relationships (at work/school and socially), their ability to carry out responsibilities (at home or work/school), and their emotional responses and mood, with the largest effect being reported for ability to manage household and work responsibilities, school work/homework, and emotional responses or mood (Table 4)

TABLE 4. EFFECTS OF MEDICATION WEARING OFF, OVERALL AND BY MEDICATION GROUP.

| PARTICIPANTS, N (%) | ALL ADHD (N = 616) | SHORT-ACTING (N = 166) | LONG-ACTING (N = 201) | AUGMENTERS (N = 249) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship with spouse/partner** | ||||

| All negative | 98 (29.4) | 20 (23.3) | 27 (24.3) | 51 (37.5) |

| Not negative/some negative | 235 (70.6) | 66 (76.7) | 84 (75.7) | 85 (62.5) |

| N/A | 283 | 80 | 90 | 113 |

| Relationship with children | ||||

| All negative | 66 (21.9) | 20 (24.1) | 20 (23.3) | 26 (19.7) |

| Not negative/some negative | 235 (78.1) | 63 (75.9) | 66 (76.7) | 106 (80.3) |

| N/A | 315 | 83 | 115 | 117 |

| Ability to be a responsible parent | ||||

| All negative | 66 (21.9) | 22 (25.6) | 19 (22.6) | 25 (18.9) |

| Not negative/some negative | 236 (78.1) | 64 (74.4) | 65 (77.4) | 107 (81.1) |

| N/A | 314 | 80 | 117 | 117 |

| Relationship with parents | ||||

| All negative | 79 (17.1) | 17 (14.7) | 23 (15.9) | 39 (19.4) |

| Not negative/some negative | 383 (82.9) | 99 (85.3) | 122 (84.1) | 162 (80.6) |

| N/A | 154 | 50 | 56 | 48 |

| Friendships | ||||

| All negative | 122 (20.9) | 28 (17.9) | 38 (19.6) | 56 (23.9) |

| Not negative/some negative | 462 (79.1) | 128 (82.1) | 156 (80.4) | 178 (76.1) |

| N/A | 32 | 10 | 7 | 15 |

| Relationship with colleagues | ||||

| All negative | 106 (24.4) | 28 (23.0) | 28 (22.4) | 50 (26.6) |

| Not negative/some negative | 329 (75.6) | 94 (77.0) | 97 (77.6) | 138 (73.4) |

| N/A | 181 | 44 | 76 | 61 |

| Ability to manage household responsibilities | ||||

| All negative | 214 (47.8) | 57 (45.6) | 73 (55.3) | 84 (44.0) |

| Not negative/some negative | 234 (52.5) | 68 (54.4) | 59 (44.7) | 107 (56.0) |

| N/A | 168 | 41 | 69 | 58 |

| Ability to manage responsibilities at work | ||||

| All negative | 250 (49.0) | 63 (43.8) | 78 (49.4) | 109 (52.4) |

| Not negative/some negative | 260 (51.0) | 81 (56.3) | 80 (50.6) | 99 (47.6) |

| N/A | 106 | 22 | 43 | 41 |

| Ability to do schoolwork/homework | ||||

| All negative | 45 (63.4) | 11 (55.0) | 16 (55.5) | 18 (81.8) |

| Not negative/some negative | 26 (36.6) | 9 (45.0) | 13 (44.8) | 4 (18.2) |

| N/A | 545 | 146 | 172 | 227 |

| Emotional response or mood | ||||

| All negative | 235 (39.0) | 58 (35.6) | 79 (40.3) | 98 (40.2) |

| Not negative/some negative | 368 (61.0) | 105 (64.4) | 117 (59.7) | 146 (59.8) |

| N/A | 13 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

Note: *P < 0.05,

**P < 0.001 group comparison.

Burden on Everyday Life

Participants who report being treated for their ADHD still experienced considerable burden. Participants indicated they experienced at least one impact on various aspects of life, including home life (83%, n = 510/616), social life (76%, n = 471/616), relationships (68%, n = 417/616), work (79%, n = 359/452), and school (81%, n = 104/129)

A greater percentage of LA and SA participants versus AU participants reported issues finishing tasks (LA 70% [n = 140]; SA 72% [n = 120]; AU 54% [n = 135]; P = 0.0001), a lack of motivation (LA 59% [n = 118]; SA 49% [n = 81]; AU 41% [n = 102]; P < 0.001), and being organized in daily life (LA 56% [n = 113]; SA 50% [n = 83]; AU 41% [n = 103]; P < 0.01). LA participants were more likely to report forgetfulness (LA 61% [n = 122]; SA 43% [n = 72]; AU 47% [n = 118]; P < 0.01)

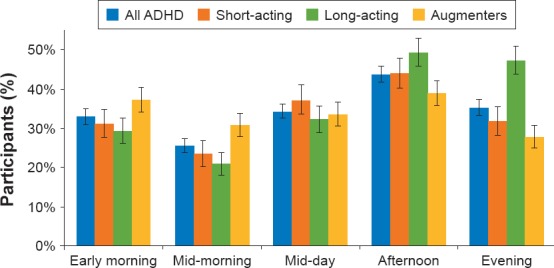

Difficult Time of Day

Close to half of participants reported that the afternoon was the most difficult time of the day (44%, n = 269), with there being no significant difference between the SA, LA, or AU medication groups (44% [n = 73]; 49% [n = 99]; and 39% [n = 97], respectively; Figure 2)

Significantly more participants in the LA (47%, n = 95) than in the AU (28%, n = 70; P < 0.0001) or SA (32% [n = 53]; P < 0.01) groups reported that the evening was a particularly challenging time of the day (Figure 1). Significantly more participants in the AU (31%, n = 77) than in the LA group (21% [n = 42]; P < 0.0001) reported that midmorning was a difficult time of the day

Impairment in Home, Social, and School/Work Settings

Despite receiving medication, ADHD impacted the participants’ home lives. Difficulties were reported in terms of completing tasks (59%, n = 361), keeping the household organized (53%, n = 325), managing household chores (48%, n = 29), sleeping at night (38%, n = 233), and paying bills on time (28%, n=175). LA participants experienced greater difficulties than SA (p<0.05) and AU (P<0.05) participants

The participants reported challenges with various aspects of their social life, including feeling awkward (38%, n = 231), tending to forget names (38%, n = 231), holding conversations (32%, n = 195), and not feeling social (31%, n = 190). The frequency of these challenges did not differ significantly between the treatment groups

The 129 student participants indicated that they experienced a number of difficulties at school, including focusing in class (50%, n = 65) or while doing school work (46%, n = 59), prioritizing tasks (32%, n = 41), and taking notes in class (31%, n = 40). AU participants reported significantly greater difficulty taking notes than SA participants (P < 0.05)

Similarly, the 452 participants who were employed indicated that they experienced a number of difficulties at work, including focusing on tasks (50%, n = 228), being organized (42%, n = 191), being productive (34%, n = 155), forgetting to do simple tasks (31%, n = 141), and completing tasks on time (28%, n = 128)

There is a potential for selection bias as participants were recruited through research participant panels. In addition, a majority of the participants were female, which may limit the generalizability of the results

Participants self-reported their ADHD diagnosis and treatment in our survey without clinician confirmation

Conclusions

Even with medication, ADHD places considerable burden on adults with the condition

Adults with ADHD reported experiencing difficulties across the entire day, in particular during afternoon and evening hours, when medication has worn off and when work, familial, and household responsibilities are present

Duration of effect was a key driver of treatment choice and satisfaction with treatment, with many participants indicating a desire for more adequate coverage, possibly a longer-acting medication with augmentation or a single medication that lasts all day

Optimizing treatment for adults with ADHD involves accounting for specific patient needs for coverage at multiple times of day and appropriate dose optimization. Differences between medications with regard to time of onset and duration of effective action should be considered in order to provide adequate coverage for various activities that may extend over substantial portions of the day, especially into the afternoon and evening, in line with individual needs of each patient

TABLE 1. INCLUSION CRITERIA FOR ADHD PARTICIPANTS.

|

Figure 3.

Most Challenging Time of Day

Footnotes

Presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting, May 20–24, 2017, San Diego, CA.

Disclosure

Drs. Brown, Flood, Sarocco, Atkins, and Khachatryan have no conflict of interest to disclose in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Wender PH, Wolf LE, Wasserstein J. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;931:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Post RE, Kurlansik SL. Am Fcm Physician. 2012;85:890–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weyandt LL, Oster DR, Marraccini ME et al. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2014;7:223–249. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S47013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brams M, Moon E, Pucci M et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1809–1825. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.488553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawson KA, Johnsrud M, Hodgkins P et al. Clin Ther. 2012;34:944–956.e944. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lachaine J, Beauchemin C, Sasane R et al. Postgrad Med. 2012;124:139–148. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2012.05.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]