Abstract

Optically transparent wood, combining optical and mechanical performance, is an emerging new material for light‐transmitting structures in buildings with the aim of reducing energy consumption. One of the main obstacles for transparent wood fabrication is delignification, where around 30 wt % of wood tissue is removed to reduce light absorption and refractive index mismatch. This step is time consuming and not environmentally benign. Moreover, lignin removal weakens the wood structure, limiting the fabrication of large structures. A green and industrially feasible method has now been developed to prepare transparent wood. Up to 80 wt % of lignin is preserved, leading to a stronger wood template compared to the delignified alternative. After polymer infiltration, a high‐lignin‐content transparent wood with transmittance of 83 %, haze of 75 %, thermal conductivity of 0.23 W mK−1, and work‐tofracture of 1.2 MJ m−3 (a magnitude higher than glass) was obtained. This transparent wood preparation method is efficient and applicable to various wood species. The transparent wood obtained shows potential for application in energy‐saving buildings.

Keywords: building materials, delignification, energy saving, lignin, wood

Introduction

Environmentally friendly, energy‐saving buildings are highly appealing from the sustainability perspective in light of a worldwide energetic and environmental crisis. Transparent wood has received much attention, owing to its great potential for application in light‐transmitting buildings, which can partially replace artificial light with sunlight and therefore save energy.1 The merits of transparent wood as a light‐transmitting building element include its origin as a renewable resource, low density (ca. 1.2 g cm−3), high optical transmittance (over 80 %) and haze (over 70 %), low thermal conductivity, and good load‐bearing performance with tough and noncatastrophic failure behavior (no shattering).1, 2 In addition, wood, as a hierarchical material, has great potential for further functionalization from the molecular to the macroscopic scale.3 This concept broadens the applications of wood as a multifunctional material in more advanced technologies, such as diffused‐luminescence wood structures,4 wood structured lasers,5 heat‐shielding wood windows,6 or light‐diffusing layers for solar cells.7

The current approach for preparation of transparent wood1, 2 is based on delignification of the substrate followed by polymer infiltration with a matching refractive index to the wood substrate. In the reported studies, delignification is crucial since lignin accounts for 80–95 % of light absorption in wood.8 Fink treated wood with a 5 % aqueous solution of sodium hypochlorite for 1–2 days to remove colored substances, including lignin.2a Our group reported delignification by treatment with sodium chlorite. The lignin content was strongly decreased from around 25 % to less than 3 %.1a Zhu et al. removed the lignin from wood by cooking in NaOH and Na2SO3 solution, followed by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) treatment, resulting in lignin content less than 3 %.1b Although considered critical in previous publications, delignification processes are time consuming and not necessarily environmentally friendly. Odorous components such as methyl mercaptan, dimethyl sulfide, and hydrogen sulfide are generated during industrial process such as Kraft pulping.9 In addition, the formation of toxic effluents such as chlorinated dioxins during delignification suggests that totally chlorine‐free (TCF) processes are preferred.9b, 10 Meanwhile, it is important to note that lignin accounts for around 30 wt % of the wood, and cross‐links with different polysaccharide in wood in order to confer the structural support.11 Removal of lignin will damage and weaken the wood structure so that handling and fabrication of large substrates become challenging and unpractical. This also limits the number of wood species for transparent wood preparation; pine, for example, breaks into pieces after the delignification step.

Based on the arguments described above, the possibility to make transparent wood without delignification was investigated. Lignin modification by removing only chromophoric structures has the potential for large‐scale transparent wood preparation, regardless of wood species, paving the way for industrialization of transparent wood. Alkaline H2O2 treatment is of interest in this context, since this is known to reduce light absorption in wood, with low delignification.12 During the process, chromophore structures are removed or selectively reacted, while the bulk lignin is preserved. Therefore, the hierarchical wood structure is better preserved. The chlorine‐free reagent H2O2 was therefore used to remove only the chromophores in wood but preserve the main wood structural components. Scheme 1 shows the fabrication of lignin‐retaining transparent wood. Following the alkaline H2O2 treatment, the wood color changed from its characteristic light brown to white with up to 80 wt % of lignin retained in the wood structure. Transparent wood was obtained after infiltration with poly(methyl mecthacrylate) (PMMA), and the optical transmittance and haze were 83 % and 75 %, respectively. The optical properties are comparable with or even better than transparent wood made from a delignified wood template. The preparation process for transparent wood has been significantly improved with a more environmentally friendly and time‐saving process. The applicability to various wood species, including pine, ash and birch, is demonstrated. No problems associated with handling of the wood template occur in contrast with delignification alternative.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of lignin‐retaining transparent wood. Lignin was mainly preserved in the wood structure after lignin‐retaining treatment using alkaline H2O2. By filling the wood structure with PMMA, a piece of transparent wood was obtained. The dimension of the transparent wood in the picture is 100 mm×100 mm×1.5 mm.

Results and Discussion

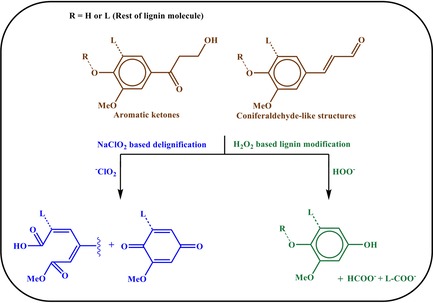

The lack of transparency in wood is mainly due to the porous lumen space at the center of fibrous tracheid and vessel cells, with diameters in the order of tens of micrometers.1a In addition, lignin, tannins, and other resinous compounds absorb light through chromophore groups. Lignin is the main component contributing to the brownish wood color.8 Scheme 2 shows two typical lignin structures, coniferaldehyde and aromatic ketones, which are the main contributors to the wood color.13 In NaClO2‐based delignification processes, the aromatic structure undergoes oxidative ring‐opening reactions to form acidic groups, which make the lignin more soluble in water.14 This is currently the established strategy to prepare wood templates for transparent wood. Alkaline H2O2 treatment removes or selectively reacts chromophore structures, while the bulk lignin is preserved.15 It is an attractive method since it is environmentally friendly and industrially scalable, and results in strong brightness/brightness stability effects in wood pulp.12 The typical reactions are outlined in Scheme 2.16

Scheme 2.

Representative lignin reactions and structures contributing to wood color, as well as the main products of the two routes (NaClO2‐based delignification and alkaline H2O2‐based lignin modification).

The brightness was measured to determine the acceptable value for further transparent wood preparation. To evaluate the wood template preparation methods, various wood species were used including balsa, birch, ash, and pine. The lignin modification method is superior to the delignification process in the following four aspects:

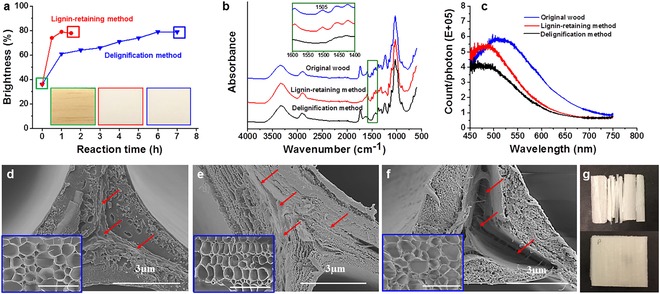

1) The lignin modification method is completed in a short time. When balsa wood was exposed to alkaline H2O2 treatment, the wood brightness increased sharply to 77 % after only 0.5 h. After 1 h, the brightness reached 79 %, which is acceptable for transparent wood preparation. Further increase in the processing time did not increase the brightness beyond 80 %. The wood is white (Figure 1 a) and suitable for transparent wood preparation. During delignification, in contrast, the brightness increased slowly with treatment time. The brightness stabilized at around 80 % after a 6 h process. The appearance of the wood template is similar to the previous sample (Figure 1 a). To make large wood templates for transparent wood, a piece of balsa wood with dimensions of 100 mm×100 mm×3 mm was prepared in 5 h (see the Supporting Information, Figure S1). For comparison, it takes 24 h to make the same size template with the delignification process. With other species, the reaction time was also significantly reduced (Table 1).

Figure 1.

a) Wood brightness before and after lignin modification and delignification; inset images are the photographs of the original wood (left), delignified wood template (middle), and lignin‐modified wood template (right). b) FTIR spectra for original wood, lignin‐modified wood template, and delignified wood template. c) Photoluminescence spectra of original wood, lignin‐modified wood template, and delignified wood template. d–f) SEM images of cell wall structures of original wood (d), lignin‐modified wood template (e), and delignified wood template (f). The inset images are low‐magnification SEM images with scale bars of 100 μm. Red arrows point to the lignin‐rich middle lamella, which is almost empty and open in (f). g) Pine templates with dimensions of 20 mm×20 mm×1.5 mm obtained through delignification (top) and lignin modification (bottom).

Table 1.

Comparisons of two methods (delignification method and lignin modification method) to prepare the wood templates from various wood species for transparent wood fabrication.

| Wood species | Treatment method(s) | Time [h] | Weight loss [wt %] | Lignin content [wt %] | Wet strength[a] ∥ fiber [MPa] | Wet strength[a] ⊥ fiber [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balsa | lignin modification | 2 | 12 | 21.3 | 7.9±1.2 | 0.2±0.09 |

| delignification | 6 | 26.4 | 2.5 | 6.9±1.3 | 0.2±0.04 | |

| Birch | lignin modification | 2 | 10.6 | 20.1 | 14.4±3.3 | 0.8±0.2 |

| delignification | 12 | 25.3 | 3.3 | 1.4±0.4 | 0.07±0.03 | |

| Pine | lignin modification | 8 | 25.0 | 22.3 | 14.4±2.2 | 0.1±0.02 |

| delignification | 18 | 40.9 | 5.2 | –[b] | –[b] | |

| Ash | lignin modification | 4 | 15.5 | 22.4 | 13.9±1.4 | 0.2±0.05 |

| delignification | 18 | 31.1 | 5.3 | 0.8±0.3 | –[b] | |

| Basswood,1b thickness ∥ fiber | delignification and bleach | 12 | – | ≈1.5 | – | – |

| Basswood,1b thickness ⊥ fiber | delignification and bleach | 6 | – | ≈1.5 | – | – |

| Cathay poplar19 | delignification and bleach | 16 | – | – | – | – |

[a] For mechanical test, the samples are cut into dimension of 50 mm×10 mm×1.5 mm before chemical treatment. [b] The samples are too weak to keep the shape for the test. Lignin content of the original wood: pine: 32.5 wt %, birch: 24.2 wt %, balsa: 23.5 wt %, ash: 27.1 wt %.

2) Lignin is largely retained and the wood structure is therefore better preserved. To confirm the presence of lignin in the wood template, both FTIR and photoluminescence microscopy were applied. In the FTIR spectrum, the band at 1505 cm−1 is characteristic of aromatic compounds (phenolic hydroxy groups) and is attributed to aromatic skeleton vibrations from lignin (Figure 1 b). There was no intensity decrease around 1505 cm−1 in the spectrum, which means lignin was largely preserved and only chromophoric regions were affected.17 For the delignified wood template, in contrast, the peak at 1505 cm−1 almost disappeared, proving that lignin was removed from the wood structure. We then used the fact that lignin is photoluminescent and can be excited with UV and visible light with a broad luminescent emission range,18 whereas polysaccharide components in the cell walls are nonfluorescent. The photoluminescence spectra of original wood, and wood templates prepared by the lignin‐retaining and delignification methods are shown in Figure 1 c. The lignin in the original sample shows a broad luminescent spectrum with a peak around 520 nm. A similar broad photoluminescence spectrum was obtained from lignin‐modified wood. The peak showed a blueshift, perhaps due to a change in lignin structure during the treatment. The luminescence intensity decreased only slightly compared to the original wood. This also shows that lignin was largely preserved in the wood structure. For delignified wood, the luminescence spectrum was also obtained due to the lignin residues. However, the intensity was severely decreased, owing to the lignin removal. The photoluminescent microscopy images are shown in Figure S2 to visualize the presence of lignin in the wood template. Klason lignin was measured to determine the lignin loss during the process. The lignin content with the lignin modification method decreased only slightly, from 23.5 wt % to 21.3 wt %, about 80 wt % of the lignin content of the original wood. With the delignification process, the lignin content was decreased significantly from about 23.5 wt % to 2.5 wt %, that is, more than 90 wt % of lignin was removed. FE‐SEM images (Figure 1 d, e) of the cell wall before and after H2O2 treatment did not show substantial micro‐scale damage, not even in the lignin‐rich middle lamella. Delamination of the cell wall occurred at the middle lamella to a very limited extent. This is in accordance with largely preserved lignin distribution. In contrast, severe cell wall delamination occurred after delignification (Figure 1 f). This occurs as the large lignin fraction in the middle lamella, between wood cells, was removed. Cell walls become separated and the open space between them is much larger than the space originally occupied by the middle lamella. The weight‐loss measurement confirms better preservation of the wood composition for all wood species (Table 1).

3) Lignin‐modified wood templates show better mechanical properties. This is essential when conducting large‐scale transparent wood fabrication from various wood species. Lignin is a polymer matrix bonding agent for cellulose fibrils in the cell wall, bonding the nanofibrils and fiber together, endowing the plants with high strength and stiffness. After delignification, the mechanical strength of the wood template was reduced. However, with the lignin modification method, this is not a problem. Wet strength was measured to characterize the mechanical stability handling of the wood template during the fabrication of transparent wood. The wet strengths of the wood templates are listed in Table 1 with force applied both parallel and perpendicular to the fiber direction. Wet strengths for birch, pine, and ash were much higher than for delignified samples. For the low‐density balsa wood templates, the difference was marginal. After delignification, pine and ash usually fall apart even with careful handling. With lignin modification, in contrast, the wood structure is well preserved. Figure 1 g shows images of two pine templates prepared by either lignin modification or delignification, showing the preserved mechanical stability of template obtained from lignin modification. The lignin modification method also better preserved the mechanical integrity of the sample.

4) The lignin modification method is a green process since toxic effluents are minimized. Alternative delignification methods have disadvantage in this respect. For example, the formation of methyl mercaptan, dimethyl sulfide, and hydrogen sulfide in Kraft pulping9 and chlorinated dioxins during NaClO2 treatment9b, 10 are harmful. All aspects considered, the lignin modification method is a better process than delignification, and may bring us a step closer to realization of industrial‐scale manufacturing of transparent wood.

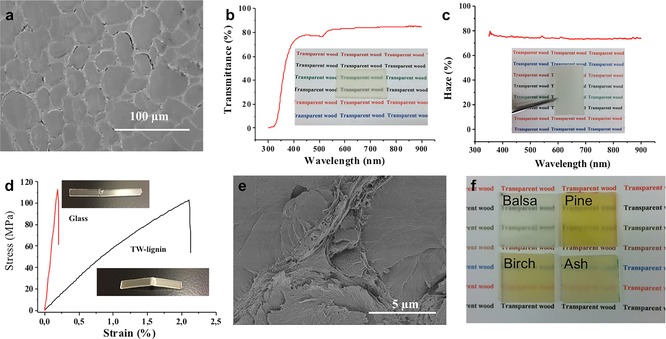

Transparent wood was fabricated based on a lignin‐modified wood template (TW‐lignin). Figure 2 a shows the SEM image of the transparent wood, illustrating the infiltration of pre‐polymerized methyl methacrylate (MMA) into the wood lumen. The resulting transparent wood demonstrated high optical performance. The optical transmittance and haze of balsa TW‐lignin at λ=550 nm were 83 % and 75 % respectively for a specimen thickness of 1.5 mm (Figure 2 b, c). Since haze is the ratio of diffused light transmittance to total transmittance (diffused transmittance+direct transmittance), this means that diffused transmittance dominates, despite the high optical transmittance. High haze is favorable for applications such as solar cells, since the light path in the active layer can be drastically increased. The optical transmittance value for TW‐lignin was similar to that of transparent wood based on the delignified wood template (TW‐delign, 86 %). Nonetheless, the TW‐lignin showed an increase in haze of about 7 % compared with TW‐delign, which is beneficial for solar cells (Figure S3). One may speculate that the increased haze for TW‐lignin may be caused by the comparably large refractive index mismatch between lignin (1.61) and PMMA (1.49). From the data, it is apparent that delignification is not necessary for transparent wood fabrication. Lignin modification by only removing the chromophoric structures is adequate to obtain transparent wood with transmittance and haze values up to 80 % and 75 % respectively. Owing to the synergy between wood and PMMA, transparent wood showed better mechanical properties than both neat PMMA and the neat wood substrate.1a To assess the possibility of transparent wood as a glass replacement in structural applications, a 3‐point bending test was carried out, with stress–strain curves shown in Figure 2 d. Transparent wood showed comparable stress at breakage (100.7±8.7 MPa) with glass (116.3±12.5 MPa), and much higher strain to failure (2.18 %±0.14) than glass (0.19 %±0.02). This leads to one‐order higher work of fracture for transparent wood (1.2 MJ m−3) than glass (0.1 MJ m−3). This is due to the reinforcing wood template skeleton in the composite. The wood–PMMA bond integrity appears favorable at sub‐micrometer scale (Figure 2 e), which leads to good load transfer in the composites. In addition, the nanocellulose reinforcement in the composite prevents brittle fracture (shattering), which is considered a safety problem for glass in applications such as windows. Although glass has a high modulus (62.4±1.0 GPa in our test), it is a brittle material. With the lignin modification method, large transparent wood samples with dimensions of around 100 mm×100 mm×1.5 mm were easily obtained, as shown in Scheme 1. Moreover, transparent wood can be made with many different wood species. Figure 2 f shows the images of transparent wood made from balsa, birch, ash, and pine, respectively. Their corrensponding optical transmittance and optical haze spectra are shown in the Supporting Information (Figure S4). In the case of pine and ash, it is difficult to make transparent wood from delignified wood templates, owing to weakening of the wood structure. In addition, transparent wood also demonstrates lower thermal conductivity (0.23 W mK−1) than glass (1.0 W mK−1). This can bring both economic benefits, by reducing the energy consumption of air‐conditioning systems and extending indoor thermal comfort especially between seasons, and environmental benefits, by decreasing the pollutants emitted from air‐conditioning systems.

Figure 2.

a) SEM image of TW‐lignin, showing the distribution of PMMA in wood lumen space. b) Optical transmittance of TW‐lignin; the inset is a photograph of transparent wood with thickness of 1.5 mm. c) Optical haze of TW‐lignin; the inset is a picture of TW‐lignin with a 5 mm gap between the sample and the underlying paper. d) Three‐point bending calculated stress–strain curves of TW‐lignin and glass; inset images are the fractured samples after test. e) SEM image of TW‐lignin after fracture, demonstrating the ductile fracture. f) Images of lignin‐retaining transparent wood made from balsa, pine, birch, and ash.

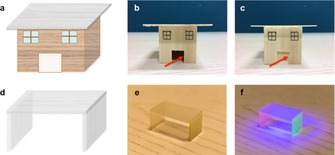

With the combined optical properties, mechanical performance and low thermal conductivity, lignin‐retaining TW is a good candidate for energy‐saving buildings. The energy consumption from lighting systems can be partially replaced by sunlight if a transparent wood roof or window is used. A demonstration of a TW‐based roof is shown in Figure 3 a–c. When a normal wood roof is used on the model house, the inner space is dark and artificial lighting is needed. Transparent wood roof, in contrast, allows light transmission to the interior of the house. Artificial lighting is minimized or not necessary at all in this case. Moreover, with the TW characteristic of high haze, the indoor privacy is also protected at the same time. The low thermal conductivity helps to decrease the heat exchange between the interior and the exterior. This, in turn, reduces the energy consumption that is required for airconditioning systems, for example, and extends indoor thermal comfort, especially between seasons. Another important application for transparent wood is its use in furniture, where both aesthetic and functional properties are sought in modern homes and offices. Figure 3 d–f shows the design of a transparent wood stool. By using quantum dots embedded in a transparent wood panel, diffused luminescence is also possible. This is advantageous for planar light sources and luminescent building construction elements or furniture. Figure 3 f demonstrates the luminescent transparent wood stool.

Figure 3.

a) Design of model house with transparent wood roof. b) Model house with original wood roof, where indoor is dark. c) Model house with transparent wood roof, where indoor is bright. d) Design of transparent wood stool. e) Photograph of a transparent wood stool model. f) Photograph of a luminescent transparent wood stool.

Conclusions

It was demonstrated that delignification is not a necessary step for transparent wood fabrication. In this work, a novel type of high‐lignin content transparent wood samples was prepared from lignin‐retaining wood templates. The wood template preparation was significantly improved by removing only a small fraction of chromophores in an efficient and environmentally friendly process. Up to 80 wt % of the lignin was preserved in the wood template. The preservation of lignin leads to much better mechanical properties compared with delignified samples, and this is favorable for large transparent wood structures made from various wood species. After infiltration and polymerization of PMMA pre‐polymer, transparent wood was obtained with a transmittance and haze up to 83 % and 75 % respectively. The 3‐point bending data showed one‐order of magnitude higher work to fracture of transparent wood (1.2 MJ m−3) compared with glass (0.1 MJ m−3). This results in noncatastrophic failure behavior (no shattering, as in glass), which is highly relevant for building application. By only removing chromophoric structures of lignin, transparent wood can be obtained from various wood species, which is a challenge with present delignification methods.

Experimental Section

Lignin modification

Pine, birch, and ash wood veneer with thickness of 1.5 mm were purchased from Glimakra of Sweden AB. Balsa wood (Ochroma pyramidale) was purchased from Wentzels Co. Ltd, Sweden with dimensions of 100 mm×100 mm×1.5 mm. The lignin modification solution was prepared by mixing chemicals in the following order: deionized water, sodium silicate (Fisher Scientific UK, 3.0 wt %), sodium hydroxide solution (Sigma–Aldrich, 3.0 wt %), magnesium sulfate (Scharlau, 0.1 wt %), DTPA (Acros Organics, 0.1 wt %), and then H2O2 (Sigma–Aldrich, 4.0 wt %). The wood substrates were submerged in the lignin modification solution at 70 °C until the wood became white. The samples were then thoroughly washed with deionized water and kept in water until use.

Sodium chlorite delignification

Delignification was performed according to our previously reported method.1a Wood was delignified by using 1 wt % sodium chlorite (NaClO2, Sigma–Aldrich) in acetate buffer solution (pH 4.6) at 80 °C.20 The reaction continued until the wood became totally white. The delignified samples were carefully washed with deionized water and kept in water until further use.

Transparent wood preparation

Before polymer infiltration, wood samples were dehydrated with ethanol and acetone sequentially. Each solvent‐exchange step was repeated three times. Polymer infiltration for transparent wood fabrication was done according to our previously reported method.1a MMA was pre‐polymerized before infiltration to remove the dissolved oxygen. Pre‐polymerization was carried out at 75 °C for 15 min with 0.3 wt % 2,2′‐azobis(2‐methylpropionitrile) (AIBN, Sigma–Aldrich) as initiator and the solution was then cooled to room temperature. Subsequently, the delignified or bleached wood template was fully vacuum‐infiltrated in pre‐polymerized PMMA solution. Finally, the infiltrated wood was sandwiched between two glass slides, packaged in aluminum foil, and the polymerization was performed in an oven at 75 °C for 4 h. Luminescent transparent wood was prepared according to a previously reported method.4 Briefly, the quantum dots (QDs) were mixed with pre‐polymerized PMMA first, then the lignin‐retaining wood template was fully vacuum‐infiltrated with the pre‐polymerized PMMA/QDs solution in a desiccator under house vacuum. Finally, the infiltrated wood was sandwiched between two glass slides, wrapped with aluminum foil, and heated at 70 °C for 4 h.

Characterization

The cross‐sections of the wood samples were observed by field‐emission scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi S‐4800, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 1 kV. Freeze‐drying was conducted on deionized water washed wood samples. The cross‐section of the samples was prepared by fracturing the freeze‐dried samples after cooling with liquid nitrogen. Three‐point bending tests of the transparent wood and glass were performed by using an Instron 5944 with a 500 N load cell. The tests were carried out with a 10 % min−1 strain rate and span of 30 mm. All samples were cut into strips (5 mm×60 mm) for testing. Lignin content (Klason lignin) in the wood samples was determined according to the TAPPI method TAPPI T 222 om‐02.21 Wood brightness was tested according to ISO brightness 2470‐1, 2009.22 The transmittance and haze were measured according to our previously reported method.1a A light source with wavelengths of 170–2100 nm was applied (EQ‐99 from Energetiq Technology, Inc.). For transmittance measurements, the sample was put in front of an integrating sphere's incident beam input port and the spectrum was then analyzed using light coupled out of the sphere through another port using an optical fiber. Haze measurement was recorded following the “Standard Method for Haze and Luminous Transmittance of Transparent Plastics” (STM D1003).23 Luminescence spectra were measured in a home‐built instrument based on an integrating sphere. The selected excitation wavelength was 440 nm (6 nm linewidth) filtered from the laser‐driven light source (EQ‐99 from Energetiq Technology, Inc.) by a monochromator.24

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from KTH in the European Research Council project No 742733, Wood NanoTech. Ilya Sychugov is acknowledged for support with photoluminescence experiments.

Y. Li, Q. Fu, R. Rojas, M. Yan, M. Lawoko, L. Berglund, ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 3445.

Contributor Information

Dr. Yuanyuan Li, Email: yua@kth.se.

Prof. Lars Berglund, Email: blund@kth.se.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Li Y., Fu Q., Yu S., Yan M., Berglund L., Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 1358–1364; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Zhu M., Song J., Li T., Gong A., Wang Y., Dai J., Yao Y., Luo W., Henderson D., Hu L., Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 5181–5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Fink S., Holzforschung 1992, 46, 403–408; [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Li T., Zhu M., Yang Z., Song J., Dai J., Yao Y., Luo W., Pastel G., Yang B., Hu L., Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1601122. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burgert I., Cabane E., Zollfrank C., Berglund L., Int. Mater. Rev. 2015, 60, 431–450. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li Y., Linnros S. Yu. J. G. C. Veinot. J., Berglund L., Sychugov I., Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1600834. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vasileva E., Li Y., Sychugov I., Mensi M., Berglund L., Popov S., Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1700057. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu Z., Yao Y., Yao J., Zhang L., Zhang C., Gao Y., Luo H., J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 6019. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu M., Li T., Davis C. S., Yao Y., Dai J., Wang Y., AlQatari F., Gilman J. W., Hu L., Nano Energy 2016, 26, 332–339. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Müller U., Rätzsch M., Schwanninger M., Steiner M., Zöbl H., J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2003, 69, 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Das T. K., Jain A. K., Environ. Prog. 2001, 20, 87–92; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Pokhrel D., Viraraghavan T., Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 333, 37–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gavrilescu D., Environ. Eng. Manage. J. 2006, 5, 37. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sjöström E., Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramos E., Calatrava S., Jiménez L., Afinidad 2008, 65, 366–373. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carter H. A., J. Chem. Educ. 1996, 73, 1068. [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Bajpai P., Environmentally Benign Approaches for Pulp Bleaching, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2012; [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Pipon G., Chirat C., Lachenal D., Holzforschung 2007, 61, 628–633. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gellerstedt G., Agnemo R., Acta Chem. Scand. B 1980, 34, 4. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rahimi A., Azarpira A., Kim H., Ralph J., Stahl S. S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 6415–6418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Pandey K., Pitman A., Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2003, 52, 151–160; [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Wójciak A., Kasprzyk H., Sikorska E., Khmelinskii I., Krawczyk A., Oliveira A. S., Ferreira L. F. V., Sikorski M., J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2010, 215, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Donaldson L., Radotic K., J. Microsc. 2013, 251, 178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gan W., Xiao S., Gao L., Gao R., Li J., Zhan X., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3855–3862. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yano H., Hirose A., Collins P., Yazaki Y., J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 2001, 20, 1125–1126. [Google Scholar]

- 21.T. Tappi, 2002–2003 TAPPI Test Methods, 2002.

- 22.ISO brightness, 2470–2471, paper, board and pulps: measurement of diffuse blue reflectance factor; part 1: indoor daylight conditions, 2009.

- 23.D. ASTM, ASTM International, ASTM International, West Conshohoken, PA, 2000.

- 24. Sangghaleh F., Sychugov I., Yang Z., Veinot J. G., Linnros J., ACS Nano 2015, 9, 70977104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary