Abstract

Macrocycles are a structural class bearing great promise for future challenges in medicinal chemistry. Nevertheless, there are few flexible approaches for the rapid generation of structurally diverse macrocyclic compound collections. Here, an efficient method for the generation of novel macrocyclic peptide‐based scaffolds is reported. The process, named here as “MacroEvoLution”, is based on a cyclization screening approach that gives reliable access to novel macrocyclic architectures. Classification of building blocks into specific pools ensures that scaffolds with orthogonally addressable functionalities are generated, which can easily be used for the generation of structurally diverse compound libraries. The method grants rapid access to novel scaffolds with scalable synthesis (multi gram scale) and the introduction of further diversity at a late stage. Despite being developed for peptidic systems, the approach can easily be extended for the synthesis of systems with a decreased peptidic character.

Keywords: cyclization, diversity oriented synthesis, macrocycles, scaffold diversity, solid-phase synthesis

Macrocycles represent an exciting structural class in the quest for new agents for the treatment of diseases. This is illustrated by the fact that macrocyclic natural products (i.e., Cyclosporin, Erythromycin, or Vancomycin) already play an important role in therapy, mostly in the fields of immunology, anti‐infectives, and oncology. Around 70 macrocyclic drugs are currently in clinical use.1

Despite their already prominent role in medicinal chemistry, macrocycles gained renewed attention in pharmaceutical research, mainly due to the fact that an increasing number of targets proved to be ′undruggable′ by small compound libraries, usually employed in high throughput screening campaigns during the last decade. In particular, protein–protein interactions (PPIs), which constitute the majority of the currently progressed challenging targets, have proved difficult ground for RO5 (Lipinski Rule of Five) compounds. This is attributed to the fact that PPIs are characterized by extensive, shallow, and generally lipophilic binding sites scarcely populated by polar hotspots, whereas typical compound libraries mostly address binding sites represented by narrow well‐defined hydrophilic pockets.2, 3

Macrocycles inherently combine two prerequisites to be ideal systems for binding into large, shallow pockets: their size, which allows for large molecular areas of binding sites and the restricted conformational flexibility, which reduces losses in entropy in the event of binding compared to acyclic systems of similar molecular weight.4, 5, 6 Moreover, it has been demonstrated that macrocycles bear the potential for a shift from a mostly hydrophilic to a predominantly lipophilic molecular surface triggered by conformational changes. The shielding or hiding of polar functionality then allows the passive diffusion through a lipophilic biological membrane, which is a remarkable structural feature of Cyclosporin and has been demonstrated to be possible for other macrocycles as well.7, 8 Clearly only very few macrocycles bear the potential to adapt to the polarity of their surroundings and, hence, an unproblematic transmembrane transport driven by diffusion and structure‐based prediction of cell permeability is a very active field of research.9

Despite the undisputed potential delivered by macrocycles, this structural class has been underexploited in the past decades by pharmaceutical development.10, 11, 12 One of the main reasons evidently is the difficult chemical access, especially the challenges being faced with the generation of high numbers of biologically relevant diverse compounds required for HTS (high throughput screening) and the potential for rapid optimization. Even though remarkable efforts have been made in the past to overcome these difficulties, rapid access to macrocyclic libraries is still an unsolved problem.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 The SICLOPPS represents an alternative approach to purely synthetic methodologies and relies on the split‐intein mediated circular ligation, which delivers cyclic peptides in a range of 106 to 107 different systems. Despite the elegance and the convincing numbers, the method suffers from the drawback that all compounds necessarily are peptidic in nature and moreover consist exclusively of the canonical amino acids.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Scaffold diversity is a challenge and even harder to tackle than the generation of unbiased compound diversity. Scaffold diversity is an important prerequisite for screening libraries in the hit finding process. This is highly plausible because an assortment of scaffold diverse molecules will adopt several different shapes rather than a scaffold uniform assortment, which translates into a broader coverage of structural space, hence increasing the chance of the library for addressing a broad range of biological targets.25 Until now there are only very few examples for the generation of scaffold‐diverse macrocyclic libraries in the literature.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33

Here, we report a novel platform for the synthesis of highly scaffold‐diverse macrocyclic libraries using an efficient and uncomplicated protocol that can easily be used for the generation of novel macrocycles with a high degree of biologically relevant structural diversity. For this approach we coined the title “MacroEvoLution”.

Because a robust entry for the generation of macrocycles should be generated and since cyclization is obviously the key step in the synthesis, we chose a cyclization screening approach to ensure an efficient access to macrocyclic scaffolds on a broad scale. Given that only a limited proportion of the linear precursors used would cyclize, a straightforward access to the linear precursors was mandatory. Due to ease, reliability, and the large number of building blocks available to be used, we found that solid‐phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) would be the best way to get rapid access to the linear precursors that determine the class of molecules to be synthesized to cyclic peptides. The number of building blocks to be used for each peptide was restricted to three in order to remain roughly within the generally accepted limits for molecular weight (MW). Cyclic tripeptides synthesized exclusively from α‐amino acids generally are not stable;34 accordingly, only a minor part of the building blocks should comprise these. The selection of building blocks was directed by incorporation of natural product motifs, ensuring biologically relevant structural diversity. In addition to the desired skeletal diversity, a variable decoration scheme for the introduction of side‐chain residues should be applicable that would allow selective diversification at a late stage of synthesis.

The method can be divided into several clear cut steps (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the library production: Preparation of building block pools; SPPS to generate the matrix of linear precursors, cyclization screening and selection of suitable cyclization systems, large‐scale synthesis of linear precursors and subsequent cyclization, deprotection, and final decoration.

-

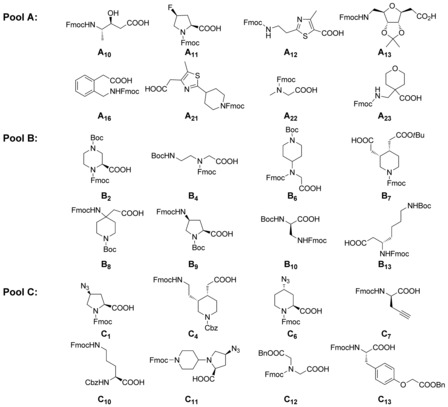

Selection and synthesis of three pools of building blocks (A, B, C). In our case, the selection was mainly based on structural attractiveness and accessibility. Potentially turn‐inducing building blocks were preferred. (Figure 2

Figure 2.

Building blocks used for SPPS.

Building blocks used for SPPS.).

SPPS of the linear precursors using a matrix of the identified building blocks. Based on the assumption that 10 % of all precursors would yield a clean cyclization reaction and with a goal of 50 diverse scaffolds, we decided in favor of an 8×8×8‐matrix (ABC, 512 structures). Standard conditions using the Fmoc‐protocol on TCP resin should be used.

Cyclization through lactamization in solution and screening using LCMS. Despite the possibility of on‐resin cyclization or cyclative cleavage,35 the cyclization reaction should be done in solution to be predictive for later large‐scale reactions (i.e., gram scale). PyBOP ({benzotriazol‐1‐yl‐oxy}tripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate) was chosen as the coupling reagent as a compromise between strong activation needed for difficult coupling and moderate activity, which would prevent possible side reactions caused by a more powerful activation method.

Selection of successful cyclization reactions based on LCMS data.

Resynthesis and cyclization on a larger scale (1–2 g).

Synthesis of final compounds and purification using HPLC (8–12 compounds per scaffold, 10 mg each) by sequential deprotection and decoration.

The methodology described is suitable for the generation of diverse cyclic peptide libraries. It shows, however, a clear perspective for development into a platform for the generation of macrocyclic structures with a lower peptidic character. The application of alternative chemistry during precursor synthesis, or in the cyclization step, seems a straightforward approach in this regard. Conceivable possibilities in this context are the replacement of peptide bonds with aryl ethers by the use of SNAr‐chemistry, the formation of C−C bonds using Pd‐mediated chemistry, or other methods. This expansion of the MacroEvoLution platform is currently ongoing.

For the selection of building blocks, two different sources of structures were used. Commercially available amino acid derivatives were complemented by structures developed in house for other library genesis projects ensuring maximal diversity on the building block level. By design, synthesis includes turn‐inducing elements in order to increase the cyclization rate (like A13, A16, B7, or C4). To implement two selectively addressable exit vectors in every scaffold, three pools were defined. Pool A was defined by having the functionality in place for SPPS (Fmoc‐protected amine, carboxylic acid), Pool B is defined by having additional a Boc‐group or a tert‐butylester unit, and Pool C was defined as having any additional functionality that could be used for decoration orthogonally to Boc/tBu (Cbz, azide, alkyne, Bn‐ester). The actual building blocks selected are depicted in Figure 2.

SPPS was done using standard protocols on a commercial peptide synthesizer at a 6 μmol scale.36 For some sequences, this approach led to termination sequences or massive side‐product formation. Due to the fact that the assortment of building blocks contains a large number of presumably strong turn‐inducing elements, the on‐resin formation of stable secondary structure elements that block the N‐terminus from further elongation might be an explanation. The use of advanced SPPS methods (like microwave‐assisted SPPS) might improve the situation leading to a higher number of linear precursors and consequently a higher rate of cyclization products.

For the cyclization a solution‐phase protocol was chosen to ensure an unproblematic upscale to gram scale later in the process. Because optimization of 512 parallel cyclization reactions was not feasible, standard high dilution conditions (10−3 m) were applied. The cyclization reaction was performed on a 96 well plate (MTP) using PyBOP as the coupling reagent.

For the assessment of the cyclization reaction, LCMS‐sampling was performed using directly the MTPs that were employed for synthesis. Analysis of the collected data gave 100 distinct cyclization systems, which translates into a cumulated (peptide synthesis and cyclization) success rate of 19.5 %. Some examples, representing different ring sizes as well as protection group patterns, are given in Figure 3. Several other sequences are also potential successful systems, though analytical data did not allow unequivocal assignment. Dimerization was a common side reaction, in some cases yielding the main product. Epimerization (presumably on the C‐terminus of the linear precursor) could be detected in several cyclization reactions. Since the cyclization in most cases is a relatively slow reaction and the C‐terminus is activated for an extended period, the occurrence of epimerization was well expected. Whenever epimerization appeared to be an issue, the cyclization system was deprioritized. The distribution over the different building blocks is naturally uneven, because the success rate is a combination of different factors (peptide synthesis, cyclization). Thus, the abundance of building blocks in successful cyclization systems was not analyzed further. The unsuccessful use of B10 was attributed to quality issues of the building block.

Figure 3.

Selected cyclization systems representing different ring sizes (11 to 21‐membered rings) and protection group patterns.

Out of the 100 cyclization systems, 60 were selected based on their composition of building blocks to obtain a maximally diverse selection of macrocyclic scaffolds. Despite the desired number of 50 scaffolds, 60 were chosen to be able to tolerate an attrition rate of 20 % during scale up and library synthesis.

The selected systems were then resynthesized on a larger scale (1–2 mmol). Results from earlier projects presumed there to be challenges for the large‐scale peptide synthesis in comparison to the smaller scale. Large‐scale precursor syntheses were accordingly done on a microwave‐assisted peptide synthesizer, giving excellent results. After resin cleavage, the side‐chain‐protected peptides were subjected to cyclization by simply scaling up the conditions applied for the test reaction, leaving as many parameters as possible untouched. Almost every selected system delivered results comparable or better than the small‐scale reactions. Problems were encountered for A13B6C6, which gave the ring‐opened product after Boc‐deprotection, A13B8C10, which decomposed during hydrogenation, and A22B4C13, for which solubility problems prevented acceptable results in the large‐scale cyclization. In the case of A12B8C13, dimerization gave the main product.

Purification was done after Boc‐deprotection via precipitation from ether removing hydrolysis products originating from the coupling reagent. Introduction of side‐chain moieties was performed mostly according to standard chemistry through acylation or reductive amination of amines and triazole formation of azides or terminal alkynes (a list of reagents used in the final decoration step is given in the Supporting Information).

The choice of the decoration residues for each individual macrocycle was based on the functional groups to be used in the functionalization, Physchem properties of the final products, and diversity considerations. Final products were purified using HPLC. The results of the cyclization screening and the upscaling are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The 100 distinct cyclization systems and the building blocks used in their composition.

| Entry | Scaffold | Building blocks | i)[a] | ii)[b] | Entry | Scaffold | Building blocks | i)[a] | ii)[b] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | A | B | C | ||||||||

| 1 | MEL100 | A16 | B6 | C1 | × | × | 51 | MEL150 | A16 | B9 | C7 | × | × |

| 2 | MEL101 | A10 | B7 | C1 | × | × | 52 | MEL151 | A23 | B9 | C7 | × | × |

| 3 | MEL102 | A13 | B7 | C1 | × | 53 | MEL152 | A10 | B13 | C7 | |||

| 4 | MEL103 | A16 | B7 | C1 | × | × | 54 | MEL153 | A21 | B13 | C7 | × | × |

| 5 | MEL104 | A21 | B7 | C1 | × | × | 55 | MEL154 | A16 | B2 | C10 | ||

| 6 | MEL105 | A13 | B8 | C1 | × | × | 56 | MEL155 | A10 | B4 | C10 | ||

| 7 | MEL106 | A21 | B8 | C1 | × | × | 57 | MEL156 | A16 | B4 | C10 | ||

| 8 | MEL107 | A10 | B9 | C1 | × | × | 58 | MEL157 | A21 | B4 | C10 | ||

| 9 | MEL108 | A13 | B9 | C1 | 59 | MEL158 | A21 | B6 | C10 | × | × | ||

| 10 | MEL109 | A16 | B9 | C1 | × | × | 60 | MEL159 | A10 | B7 | C10 | ||

| 11 | MEL110 | A21 | B9 | C1 | × | × | 61 | MEL160 | A16 | B7 | C10 | ||

| 12 | MEL111 | A21 | B13 | C1 | × | × | 62 | MEL161 | A21 | B7 | C10 | ||

| 13 | MEL112 | A12 | B7 | C4 | 63 | MEL162 | A11 | B8 | C10 | × | × | ||

| 14 | MEL113 | A21 | B7 | C4 | × | × | 64 | MEL163 | A13 | B8 | C10 | ||

| 15 | MEL114 | A22 | B7 | C4 | × | × | 65 | MEL164 | A16 | B8 | C10 | × | × |

| 16 | MEL115 | A10 | B8 | C4 | × | × | 66 | MEL165 | A21 | B8 | C10 | × | × |

| 17 | MEL116 | A11 | B8 | C4 | × | × | 67 | MEL166 | A22 | B8 | C10 | × | × |

| 18 | MEL117 | A16 | B8 | C4 | × | × | 68 | MEL167 | A10 | B9 | C10 | × | × |

| 19 | MEL118 | A21 | B8 | C4 | 69 | MEL168 | A13 | B9 | C10 | ||||

| 20 | MEL119 | A22 | B8 | C4 | × | × | 70 | MEL169 | A21 | B9 | C10 | ||

| 21 | MEL120 | A10 | B9 | C4 | 71 | MEL170 | A21 | B13 | C10 | × | × | ||

| 22 | MEL121 | A12 | B9 | C4 | 72 | MEL171 | A10 | B7 | C11 | × | × | ||

| 23 | MEL122 | A13 | B9 | C4 | × | 73 | MEL172 | A10 | B8 | C11 | |||

| 24 | MEL123 | A22 | B9 | C4 | × | × | 74 | MEL173 | A21 | B8 | C11 | × | × |

| 25 | MEL124 | A10 | B13 | C4 | × | × | 75 | MEL174 | A10 | B9 | C11 | × | × |

| 26 | MEL125 | A21 | B13 | C4 | × | × | 76 | MEL175 | A21 | B9 | C11 | × | × |

| 27 | MEL126 | A22 | B13 | C4 | × | × | 77 | MEL176 | A21 | B13 | C11 | × | × |

| 28 | MEL127 | A13 | B2 | C6 | 78 | MEL177 | A10 | B7 | C12 | ||||

| 29 | MEL128 | A13 | B4 | C6 | × | × | 79 | MEL178 | A11 | B7 | C12 | × | × |

| 30 | MEL129 | A16 | B4 | C6 | 80 | MEL179 | A13 | B7 | C12 | ||||

| 31 | MEL130 | A13 | B6 | C6 | × | 81 | MEL180 | A16 | B7 | C12 | × | × | |

| 32 | MEL131 | A22 | B6 | C6 | 82 | MEL181 | A21 | B7 | C12 | × | × | ||

| 33 | MEL132 | A12 | B7 | C6 | × | × | 83 | MEL182 | A16 | B8 | C12 | × | |

| 34 | MEL133 | A13 | B7 | C6 | 84 | MEL183 | A21 | B8 | C12 | × | × | ||

| 35 | MEL134 | A16 | B7 | C6 | 85 | MEL184 | A16 | B13 | C12 | ||||

| 36 | MEL135 | A21 | B7 | C6 | 86 | MEL185 | A21 | B13 | C12 | × | × | ||

| 37 | MEL136 | A16 | B8 | C6 | 87 | MEL186 | A16 | B2 | C13 | ||||

| 38 | MEL137 | A21 | B8 | C6 | 88 | MEL187 | A10 | B4 | C13 | × | |||

| 39 | MEL138 | A16 | B9 | C6 | 89 | MEL188 | A16 | B4 | C13 | × | |||

| 40 | MEL139 | A13 | B13 | C6 | 90 | MEL189 | A21 | B4 | C13 | ||||

| 41 | MEL140 | A21 | B2 | C7 | 91 | MEL190 | A22 | B4 | C13 | ||||

| 42 | MEL141 | A13 | B4 | C7 | × | × | 92 | MEL191 | A10 | B7 | C13 | ||

| 43 | MEL142 | A16 | B4 | C7 | × | × | 93 | MEL192 | A21 | B7 | C13 | ||

| 44 | MEL143 | A21 | B6 | C7 | × | × | 94 | MEL193 | A12 | B8 | C13 | ||

| 45 | MEL144 | A11 | B7 | C7 | × | × | 95 | MEL194 | A16 | B8 | C13 | ||

| 46 | MEL145 | A12 | B7 | C7 | × | × | 96 | MEL195 | A10 | B9 | C13 | ||

| 47 | MEL146 | A13 | B7 | C7 | 97 | MEL196 | A11 | B9 | C13 | × | |||

| 48 | MEL147 | A16 | B8 | C7 | × | 98 | MEL197 | A13 | B8 | C7 | × | × | |

| 49 | MEL148 | A21 | B8 | C7 | × | × | 99 | MEL198 | A23 | B13 | C6 | × | |

| 50 | MEL149 | A10 | B9 | C7 | × | 100 | MEL199 | A16 | B9 | C11 | × | × | |

[a] Selected 60 scaffolds for the resynthesis at larger scale. [b] Final 50 scaffolds selected. For further details (structures etc.), see the Supporting Information.

Because scaffold diversity was one of the main goals for the generation of this library, a broad distribution of ring sizes was desired. Figure 4 shows the compliance of the MacroEvoLution approach in this respect, though two things should be highlighted. Firstly, for the given selection of building blocks, the portion of cyclization systems in relation to the theoretically achievable number generally rises along with the ring size. Thus, the formation of larger rings (>15) seems to be favored. This could be attributed to the ring strain introduced by the three amide bonds, which is successively relieved in systems of increasing ring size. Secondly, two ring sizes drop out of this trend. Ten‐membered rings were not formed at all despite the fact that 60 such systems are theoretically possible. 18‐Membered rings give a much smaller percentage of successful cyclization than expected from the trend. For this observation the explanation is unclear.

Figure 4.

Analysis of obtained ring sizes. White bar: maximum number of macrocycles of a certain ring size based on the given pool of building blocks. Gray bar: actual number of cyclization systems of a certain ring size obtained. Percentage of cyclization reached in comparison to the maximum number is given above the bars.

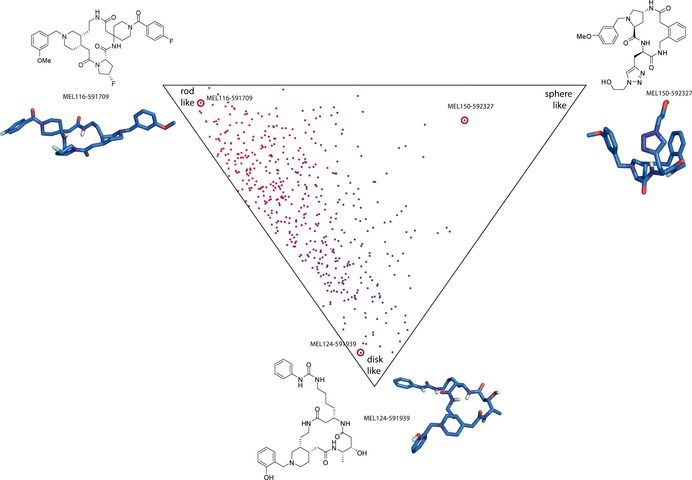

For the visualization of the diversity generated with this library, a principal moments of inertia (PMI) analysis of the actually synthesized compounds was performed (Figure 5). It shows a broad distribution with the majority of compounds being in the region between rod‐ and disc‐like and a significant portion of library members in the sphere‐like region. Sphere‐like conformations are reported to have a higher probability of penetrating biological membranes.3 This result is comparable to analyses of other macrocylic libraries.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

Figure 5.

Principal moments of inertia (PMI) analysis of the MacroEvoLution library products. PMI values were computed on the minimum energy conformation for each compound and normalized PMI ratios are plotted in the triangular scatter plot. The plot shows significant shape diversity. All compounds represented in this diagram were actually synthesized.

The cyclization success rate was calculated from cyclization systems unequivocally identified using LCMS with respect to the 512 possible linear precursors. Bearing in mind that not all 512 possible peptides were available owing to issues during synthesis—only the fact that building block B10 completely failed in peptide synthesis reduced the matrix to 448 linear precursors (8×7×8 matrix)—the cyclization screening gives a surprisingly high cyclization rate. Clearly, this can be attributed to the selection of turn‐inducing motifs into the building block pools, but also shows that the described technique represents a solid and reliable foundation for the generation of novel macrocyclic scaffolds.

In general, the method described gives rapid access to novel cyclic tripeptide scaffolds, but the flexibility of the concept gives a multitude of options for broadening the scope of applications. Completely new scaffolds can easily be identified by simply exchanging the building blocks of one pool with other suitable substitutes. Apart from the possibility of the reduction of the peptidic character, as mentioned above, it should be easy to apply the technique to larger peptides, giving access to the structural space populated by peptide‐based anti‐infectives. Moreover, with slight changes in the protection group scheme and definition of the building block pools, scaffolds carrying three or more exit vectors can be generated for applications like DNA‐encoded library techniques.

We have developed a method for the rapid and systematic generation of novel and structurally diverse macrocyclic scaffolds. The MacroEvoLution building blocks are, in many cases, the essence of AnalytiCon's synthetic library program based on natural product structural elements. In an exemplary approach, 50 newly generated scaffolds were then further derivatized in order to obtain a 500‐membered library. The method offers efficient and very robust access of up to gram amounts of novel macrocyclic scaffolds, which, due to an orthogonal protection scheme, can easily be derivatized further. Because the cyclization tendency and thus accessibility is the selection criterion for the cyclization systems, there arises only little attrition in the scale‐up process. The technique is simple and can be employed without the use of advanced technical equipment. Furthermore, the access to possible building blocks is facile, and a great variety is available either commercially or from the literature. Apart from the inherent peptidic character of the macrocycles, the building blocks themselves determine the characteristics of the resulting cyclization systems. Following investigations will focus on the stepwise reduction of the peptide character by using alternative coupling reactions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steffi Mattuschka and Dani Guthke for indispensable help with LCMS analysis, Dr. Martina Jaensch for data management, and Dr. Christian Dahlhoff and Jan Kretzschmar for help with HPLC purification.

J. Saupe, O. Kunz, L. O. Haustedt, S. Jakupovic, C. Mang, Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 11784.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jörn Saupe, www.ac‐discovery.com

Dr. Christian Mang, Email: c.mang@ac-discovery.com.

References

- 1. Giordanetto F., Kihlberg J., J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 278–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matsson P., Doak B. C., Over B., Kihlberg J., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2016, 101, 42–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doak B. C., Zheng J., Dobritzsch D., Kihlberg J., J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 2312–2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villar E. A., Beglov D., Chennamadhavuni S., Porco J. A., Kozakov D., Vajda S., Whitty A., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 723–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Driggers E. M., Hale S. P., Lee J., Terrett N. K., Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 608–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mallinson J., Collins I., Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 1409–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bockus A. T., Lexa K. W., Pye C. R., Kalgutkar A. S., Gardner J. W., Hund K. C. R., Hewitt W. M., Schwochert J. S., Glassey E., Price D. A., Mathiowetz A. M., Liras S., Jacobson M. P., Lokey R. S., J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4581–4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leung S. S. F., Mijalkovic J., Borrelli K., Jacobson M. P., J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 1621–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Over B., Mattson P., Tyrchan C., Artursson P., Doak B. C., Foley M. A., Hilgendorf C., Johnston S. E., Lee M. D., Lewis R. J., McCarren P., Muncipinto G., Norinder U., Perry M. W. D., Duvall J. R., Kihlberg J., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 1065–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wessjohann L. A., Ruijter E., Garcia-Rivera D., Brandt W., Mol. Diversity 2005, 9, 171–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Madsen C. M., Clausen M. H., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 3107–3115. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marsault E., Peterson M. L., J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1961–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marcaurelle L. A., Comer E., Dandapani S., Duvall J. R., Gerard B., Kesavan S., Lee M. D., Liu H., Lowe J. T., Marie J.-C., Mulrooney C. A., Pandya B. A., Rowley A., Ryba T. A., Suh B.-C., Wei J., Young D. W., Akella L. B., Ross N. T., Zhang Y. L., Fass D. M., Reis S. A., Zhao W.-N., Haggarty S. J., Palmer M., Foley M. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16962–16976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jefferson E. A., Arakawa S., Blyn L. B., Miyaji A., Osgood S. A., Ranken R., Risen L. M., Swayze E. E., J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 3430–3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marsault E., Hoveyda H. R., Gagnon R., Peterson M. L., Vezina M., Saint-Louis C., Landry A., Pinault J.-F., Ouellet L., Beauchemin S., Beaubien S., Mathieu A., Benakli K., Wang Z., Brassard M., Lonergan D., Bilodeau F., Ramaseshan M., Fortain M., Lan R., Li S., Galaud F., Plourde V., Champagne M., Doucet A., Bherer P., Gauthier M., Olsen G., Villeneuve G., Bhat S., Foucher L., Fortin D., Peng X., Bernard S., Drouin A., Deziel R., Berthiaume G., Dory Y. L., Fraser G. L., Deslongchamps P., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 4731–4735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jefferson E. A., Swayze E. E., Osgood S. A., Miyaji A., Risen L. M., Blyn L. B., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 1635–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kleiner R. E., Dumelin C. E., Tiu G. C., Sakurai K., Liu D. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11779–11791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen J., Rong F., Shan B., Chen Y., Li Y., Yu H., Chen L., Kuang T., Li S., Chen Y., Du J., Ai C., Li J., Li X., Shi C., Jiang Z., Long Y., Gao Q., Wang Z., Xu K., Ran X., Yi H., Zhao D., Qiao H., Shen J., Liu B., Liu C., Wu K., Geng X., Tan J., McLeod D., Frost H., Bai G., Goetz G., James F., Whitney-Pickett C., Troutman M., Noe M. C., Guimaraes C., Piotrowski D. W., Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 3298–3301. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tavassoli A., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 38, 30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scott C. P., Abel-Santos E., Wall M., Wahnon D. C., Benkovic S. J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13638–13643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Townend J. E., Tavassoli A., ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 1624–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Osher E. L., Tavassoli A., Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1495, 27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tavassoli A., Benkovic S. J., Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1126–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lennard K. R., Tavassoli A., Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 10608–10614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sauer W. H. B., Schwarz M. K., J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 987–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beckmann H. S. G., Nie F., Hagerman C. E., Johansson H., Tan Y. S., Wilcke D., Spring D. R., Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grossmann A., Bartlett S., Janecek M., Hodgkinson J. T., Spring D. R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 13093–13097; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 13309–13313. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Isidro-Llobet A., Georgiou K. H., Galloway W. R. J. D., Giacomini E., Hansen M. E., Mendez-Abt G., Tan Y. S., Carro L., Sore H. F., Spring D. R., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 4570–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Collins S., Bartlett S., Nie F., Sore H. F., Spring D. R., Synthesis 2016, 48, 1457–1473. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Comer E., Liu H., Joliton A., Clabaut A., Johnson C., Akella L. B., Marcaurelle L. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6751–6756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dandapani S., Lowe J. T., Comer E., Marcaurelle L. A., J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 8042–8048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas G. L., Spandl R. J., Glansdorp F. G., Welch M., Bender A., Cockfield J., Lindsay J. A., Bryant C., Brown D. F. J., Loiseleur O., Rudyk H., Ladlow M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2808–2812; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 2850–2854. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ciardiello J. J., Galloway W. R. J. D., O'Connor C. J., Sore H. F., Stokes J. E., Wu Y., Spring D. R., Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 3567–3578. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gilon C., Mang C., Lohof E., Friedler A., Kessler H. in Houben-Weyl: Methods of Organic Chemistry. Vol. E 22b: Synthesis of Peptides and Cyclic Peptides (Eds.: M. Goodman, A. Felix, L. Moroder, C. Tnoiolo), Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, New York, 2003, pp. 461–542. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nicolaou K. C., Winssinger N., Pastor J., Ninkovic S., Sarabia F., He Y., Vourloumis D., Yang Z., Li T., Giannakakou P., Hamel E., Nature 1997, 387, 268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chan W. C., White P. D., Eds., Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary