Abstract

Objective:

To assess whether progesterone (P4) or osteoblast P4 receptor-acting progestin (P) contributed to estrogen (E) therapy-related increased areal bone mineral density (BMD) in randomized controlled trials (RCT) with direct randomization to estrogen (ET) or estrogen-progestin (EPT) therapy.

Methods:

Systematic literature searches in biomedical databases identified RCT with direct randomization and parallel estrogen doses that measured spinal BMD change/year. Cyclic P4/P was included in this random effects meta-analysis only if for ≥ half the number of E-days.

Results:

Searches yielded 155 publications; five met inclusion criteria providing eight dose-parallel ET-EPT comparisons in 1058 women. Women averaged mid-50 years, <five years into menopause and took conjugated equine E daily at 0.625 mg with/without 2.5 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA). The weighted mean EPT minus ET percentage difference in spinal BMD change was +0.68%/year (95% CI 0.38, 0.97%) (P=0.00001). This result was highly heterogeneous (I2=81%) but this may reflect the small number of studies.

Conclusion:

Estrogen with an osteoblast P4R-acting progestin (EPT) in these five published RCT provides Level 1 evidence that MPA caused significantly greater annual percent spinal BMD gains than the same dose of ET. These data have implications for management of vasomotor symptoms and potentially for osteoporosis treatment in menopausal women.

Keywords: Estradiol, Progesterone, Spine Areal Bone Mineral Density, RCT Meta-analysis, Osteoporosis

Introduction

Menopausal ovarian hormone therapy (OHT), is either estrogen alone (ET) or estrogen-progesterone/progestin treatment (EPT)[1]. OHT has been prescribed for decades to prevent areal bone mineral density (BMD) loss in menopausal women (≥1 year since last flow)[2,3] or to treat osteoporosis[4]. A meta-analysis of ET and EPT randomized controlled trials (RCT) found major increases in BMD and a trend to decreased spine and non-vertebral fractures[2]. This meta-analysis considered ET and EPT as a single therapy, however, which may or may not be justified[2]. Women’s Health Initiative RCT data showed fracture prevention in both ET and EPT vs. their respective placebos[5,6].

Estrogen is the bone-active component of OHT acting as an anti-catabolic agent and decreasing bone resorption[7]. ET also increases gut calcium absorption and indirectly suppresses excess parathyroid hormone production leading to fragility fracture prevention[8,9]. But balanced bone resorption (catabolism) and formation (anabolism) appear optimal for preservation of adult BMD and strength[10]. In osteoporosis treatment - since resorption and formation are coupled at the bone mineralization unit (BMU) level[11] - it is theoretically important to facilitate both. Because of coupling, however, anti-catabolic therapies (such as estrogen, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, selective estrogen receptor modulators and denosumab) also inhibit bone anabolism[12]. An additional bone remodeling complexity is that resorption and formation have differing in vivo time courses; resorption in human bone takes about three weeks while new bone formation in the same BMU takes at least three months[13].

Given estrogen’s proliferative and thus potentially carcinogenic endometrial effects[14], the addition of a progesterone/progestin to estrogen (EPT) is recommended to prevent endometrial hyperplasia/carcinoma in women who have not undergone hysterectomy[15]. Since estradiol and progesterone appear to act synergistically on bone within the normal-length, ovulatory menstrual cycle[16,17], EPT as dual-mechanism therapy may also be advantageous for bone physiology. Endogenous estradiol decreases bone resorption and progesterone appears to increase bone formation[16,18]. Most synthetic, not androgen-derived progestins, e.g. medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) act through osteoblast nuclear progesterone receptors (P4R) and the Wnt/b catenin system to increase osteoblast numbers and bone matrix formation[19].

It is currently controversial whether ET and EPT differ in BMD effects. One of the pioneers of OHT for osteoporosis, asserted that: “progestogens have neither a direct effect on osteoporosis nor an additive effect when used as a component of hormone replacement therapy”[20]. However, other clinician-scientists suggest progestin-specific additions to BMD gains[21,22]. New data now show some non-estrogen anti-catabolic agents have additive BMD effects when paired with anabolic therapy[23].

Our research question was: Is there a difference in the annual change in spinal BMD within RCT in which menopausal women were directly randomized to the same dose of estrogen alone (ET) or with progesterone or an osteoblast P4R-acting progestin (EPT)? We tested the hypothesis that progesterone/progestin would add significantly to estrogen-related spinal BMD gains.

Materials and methods

All included, published articles are assumed to have followed International Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki principles in their conduct of research with human participants.

Literature search strategy

Systematic searches (Supplemental Material) were conducted of RCT in menopausal women using the electronic databases, Ovid MEDLINE (1949 to 2013), Ovid Embase (1974-2013), Google Scholar and Web of Science and updated to 2016. Abstracts from American Society for Bone and Mineral Research meetings were screened, and publication reference lists assessed for additional publications. Medical subject headings and text words were supplemented with synonyms for BMD, RCT, menopausal women and OHT with estrogen/estradiol, progestin/progesterone or both.

Supplemental Material

| Initial Literature search strategy: |

|---|

| 1 proges*.mp. |

| 2 random:.mp. |

| 3 or/1-2 |

| 4 (Norethindrone or Norethisterone).mp. |

| 5 3 not 4 |

| 6 low dos*.mp. |

| 7 5 not 6 |

| 8 exp *Estrogens/ |

| 9 7 and 8 |

| 10 exp *Bone Density/ |

| 11 9 and 10 (151) |

| 12 (bone adj5 chang*).mp. |

| 13 9 and 12 |

| 14 11 or 13 |

| 15 limit 14 to english language |

| 16 adachi *.au. |

| 17 Medroxyprogesterone.mp. |

| 18 16 and 17 |

| 19 liu *.au. |

| 20 17 and 19 |

| 21 8 and 20 (35) |

| 22 (Progesterone or Medroxyprogesterone).mp. |

| 23 estradiol.mp. |

| 24 22 and 23 |

| 25 8 and 24 |

| 26 13 or 14 or 18 or 20 or 21 |

| 27 limit 26 to English language |

| 28 limit 27 to humans |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were eligible if they were RCT in menopausal women directly (ignoring hysterectomy status) comparing estradiol/estrogen plus P4 or an osteoblast P4R-acting progestin (EPT) with estradiol/estrogen alone (ET) and measured spinal BMD change by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) over at least one year with the same estrogen agent/dose in both arms. Eligible RCT used intent-to-treat analysis. The progesterone/progestin dose needed to be for ≥ half the ET duration (i.e. for ≥14 days/28 day ET). For comparability among studies with/without multi-year data, we included only the first year’s data. The progestins, norethisterone and norethisterone acetate were excluded since they are metabolized into estrogen, and likely act through, an osteoblast estrogen as well as a testosterone receptor[24]. Norgestrel and levonorgestrel were excluded because they act through osteoblast androgen receptors. All trial protocols (except for the one in those with hysterectomy[23]) had ethics review-board approved endometrial safety precautions in place.

When publications did not include complete intent-to-treat data, we contacted the authors. Publications in non-English languages were excluded as were studies in premenopausal women or in menopausal women with bone-affecting illnesses or who were taking other bone-active therapies. Non-human studies, review articles, commentaries, letters without original data and cross-sectional studies were excluded.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of participants, dosage schedules and bone mineral density (BMD) values are provided for this Metaanalysis of Spinal BMD Changes per Year on Estrogen Therapy (ET) compared with Estrogen-Progestin Therapy (EPT) in trials that directly randomized women to one or the other group.

| Study Group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +PEPI | Liu | Adachi MPA: 10 | Adachi MPA: 20 | Lindsay CEE: 0.3 | Lindsay CEE: 0.45 | Lindsay CEE: 0.625 | Mizunuma | ||

| Number of Participants | ET* | 168 | 23 | 34 | 34 | 87 | 91 | 84 | 14 |

| EPT^ | 169 | 21 | 33 | 31 | 91 | 87 | 81 | 10 | |

| Age (years) | ET | 56.2 (3.9) | 52.0 (3.8) | 53.5 (7.4) | 53.5 (7.4) | 52.2 (3.9) | 51.9 (3.6) | 52.1 (3.1) | 55.1 (1.2) |

| EPT | 56.4 (3.9) | 52.9 (3.9) | 55.0 (6.8) | 53.6 (7.7) | 51.4 (3.5) | 51.6 (3.9) | 51.5 (4.2) | 53.7 (1.1) | |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | ET | 91 | - | - | - | 90 | 89 | 92 | 0 (100% Asian) |

| EPT | 89 | - | - | - | 88 | 98 | 90 | 0 (100% Asian) | |

| Years Into Menopause (≥1 y with no flow) | ET | - | < 5 | 12.8 (8.8) | 12.8 (8.8) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.9) | 5.1 - |

| EPT | - | < 5 | 12.8 (11.1) | 12.7 (9.4) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.9) | 3.0 - | |

| Dosage (mg unless noted) | ET | 0.625 CEE | 1 mg 17β E2 | 0.625 CEE | 0.625 CEE | 0.3 CEE | 0.45 CEE | 0.625 CEE | 0.625 CEE |

| EPT | 0.625 CEE 2.5 MPA daily | 1 µg 17β E2 10 MPA daily | 0.625 CEE 10 MPA: 15 d/mo. | 0.625 CEE 20 MPA: 15 d/mo. | 0.3 CEE 1.5 MPA daily | 0.45 CEE 2.5 MPA daily | 0.625 CEE 2.5 MPA daily | 0.625 CEE 2.5 MPA daily | |

| Spine BMD at Baseline (g/cm2) | ET | 0.966 (0.146) | 1.140 (0.101) | 1.040 (0.135) | 1.040 (0.135) | 1.140 (0.150) | 1.135 (0.155) | 1.174 (0.153) | 0.842 (0.101) |

| EPT | 0.972 (0.171) | 1.132 (0.146) | 1.047 (0.160) | 1.067 (0.154) | 1.139 (0.145) | 1.152 (0.171) | 1.144 (0.164) | 0.830 (0.107) | |

| Total Hip BMD at Baseline (g/cm2) | ET | 0.860 (0.119) | - | - | - | 0.942 (0.121) | 0.954 (0.136) | 0.979 (0.136) | - |

| EPT | 0.854 (0.13) | - | - | - | 0.944 (0.122) | 0.956 (0.147) | 0.965 (0.144) | - | |

| Femoral Neck BMD at baseline (g/cm2) | ET | - | 0.866 (0.020) | 0.771 (0.121) | 0.771 (0.121) | - | - | - | 0.679 (0.099) |

| EPT | - | 0.873 (0.027) | 0.769 (0.118) | 0.786 (0.114) | - | - | - | 0.661 (0.084) | |

+These are intent-to-treat data from the Postmenopausal Estrogen Progestin Investigation (PEPI);

ET=estrogen alone therapy; EPT= estrogen with progesterone or osteoblast progesterone receptor-acting progestin; BMD=areal bone mineral density; CEE=conjugated equine estrogen; MPA=medroxyprogesterone acetate; mo. = month.

Data collection

All publications were screened for eligibility by two reviewers (JCP and AG) based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Articles were initially selected based on abstracts but final decisions required full texts. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was change in areal BMD in the lumbar spine by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) during the first year of OHT on estrogen alone (ET) or estrogen with progesterone/progestin (EPT) treatment. Primary data were reported as percentage change so this was analysed. BMD total hip (TH) and femoral neck (FN) data were available in a few studies but were insufficient for quantitative synthesis. Meta-analysis of spine BMD percentage change per year was performed using the Cochrane analysis tool Revman (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman).

Results

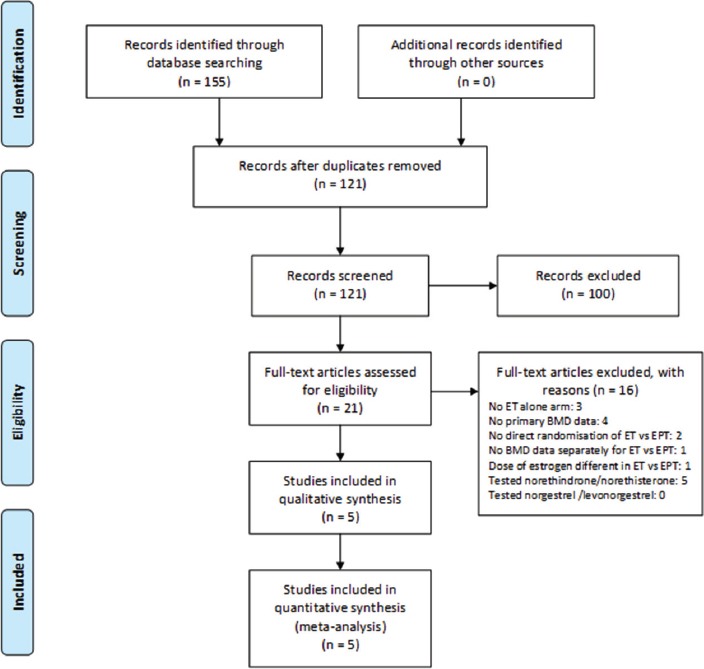

The initial literature search strategy in 2013 retrieved 41 publications of which four were duplicates[25]. A subsequent search in 2016 retrieved 155 publications; 121 remained after removal of duplicates. Following full-text review, five publications were eligible providing eight progesterone/progestin dose comparisons as shown in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1). As per our protocol, studies were excluded for not having direct randomization to ET and EPT (e.g. for having separate placebo arms for EPT and ET as in the Women’s Health Initiative[5,6]). Others were excluded for having no ET arm, for having differing doses of estrogenic hormones in the two arms or because they studied androgenic progestins metabolized to estrogens (norethindrone, norethisterone, or their acetate metabolites)(n=5)[24]. No norgestrel or levonorgestrel studies were found. We excluded the cyclic MPA and cyclic progesterone arms in the Postmenopausal Estrogen-Progestin Investigation (PEPI) trial since these agents were given for only 12 days/month with continuous ET. We excluded trials with: data only for bone biomarkers; non-menopausal women; diseased populations; or cross-sectional designs. Unpublished intent-to-treat analysis data from PEPI[26] were obtained from Drs. Elizabeth Barrett-Connor and Gail Laughlin.

Figure 1.

This PRISMA Chart of Accessed and Eligible publications (1980 to January 2016) in systematic literature searches for controlled trials that have documented changes in spinal areal bone mineral density (BMD) over one year in menopausal women directly randomized to Estrogen-Alone (ET) or to Estrogen-Progestin (EPT) Therapy without regard to hysterectomy status.

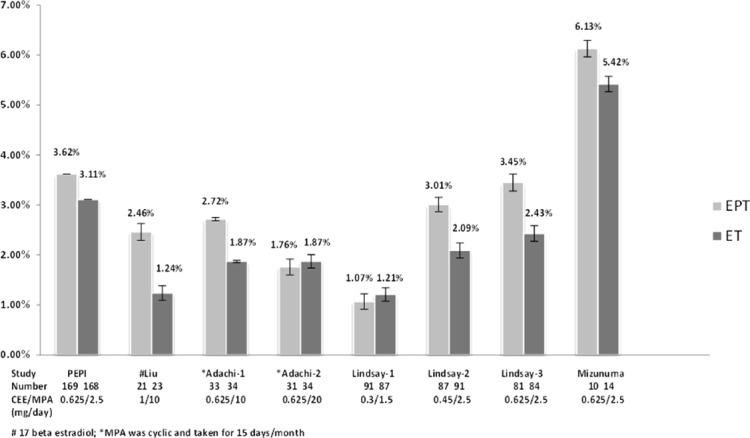

Five eligible RCT provided eight estrogen-dose parallel comparisons and randomized menopausal women directly to ET or EPT; they were published in 1996-2005[26-30]. The primary outcome was DXA-based BMD change in the lumbar spine reported as percentage change per year [%/y] over the first year. The estrogen interventions were primarily conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) in doses of 0.625, 0.45, or 0.3 mg/d; one trial administered 1 mg oral 17β-estradiol/d (E2)[29]. The progesterone/progestin in all eligible studies was MPA in doses of 1.25 to 20 mg with 2.5 mg/d being the most common dose (Figure 2, Table). Most trials prescribed both estrogen and progestin daily; MPA was prescribed cyclically for 15 days/month in one[27].

Figure 2.

Bar graph of Percentage Annual Change in Spinal areal Bone Mineral Density (BMD) from Randomized Controlled Trials of Estrogen-Alone Therapy (ET) versus Estrogen-Progestin Therapy (EPT). The study is identified underneath each bar by the abbreviated name of the study (e.g. PEPI) or the last name of the first author. Below that is the number of women in each arm. Finally, the medication and dose-comparisons are shown as a fraction with the dose of CEE or E2 on top and the dose of MPA on the bottom. Above each bar graph the mean percent change in spine BMD is shown to the nearest tenth of a percentage with SD.

As shown in the Table, participants were in early in menopause (1-11 years since final flow) except those in one[27] who averaged 12.8 years. The PEPI trial did not provide this information[26]. The average age of participants was in the early to mid-50s; women’s ethnicity was primarily Caucasian except for being apparently 100% Asian in one[30]. Baseline mean BMD (SD) values in the lumbar spine (lumbar levels L2-L4), total hip, femoral neck and trochanter are shown by study arm. Trial sizes ranged from >300[26] to fewer than 50 women[29,30]. Trial durations ranged from one to three years with an average duration of two years.

The percentage spinal BMD change per year on each dose-comparison is shown graphically (Figure 2). These data indicate that there was a numerically greater spinal BMD gain on EPT versus ET in all of the comparisons except on 0.3 mg/d CEE or on CEE 0.625 with 20 mg cyclic MPA[27,28]. Percentage changes in the total hip were available in the PEPI[26] and Lindsay[28] trials but no final BMD data were provided; femoral neck change data were reported in the Liu[29], Adachi[27] and Mizunuma[30] trials. Although these hip BMD measurements indicated increases in all active arms, none were reported to be statistically different between ET versus EPT.

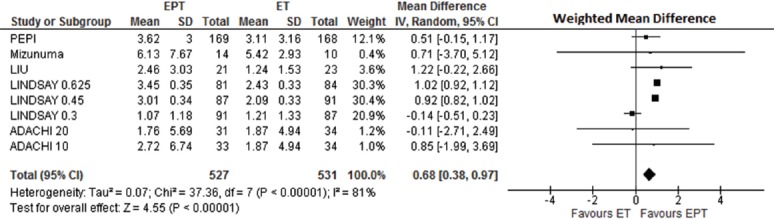

A meta-analysis was performed using a random effects model analyzing the weighted mean differences in percent spinal BMD changes between EPT and ET with results shown as a Forest plot (Figure 3). Within-study EPT arms compared with the ET ones showed a highly significantly greater weighted mean difference in spinal BMD percent change/year (y) documented as +0.68%/y (95% confidence interval 0.38, 0.97%; P=0.0001) on EPT. There also was, however, a highly significant degree of heterogeneity with I2=81%. This may simply reflect the small number of available studies[31]. Or it may be related to differences in mean years into menopause (from 2.3 to 12.8 years), and in race (most Caucasian and one Asian), the differing estrogen and progestin doses as well as varying sample sizes.

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing the Weighted Mean Difference in Percentage Annual Change in Spinal areal Bone Mineral Density (BMD) by Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry on Estrogen-Alone Therapy (ET) versus Estrogen-Progestin Therapy (EPT). This random effects meta-analysis model shows heterogeneity of the studies by I2.

Discussion

This meta-analysis of RCTs that directly assigned menopausal women to estrogen (ET) or to estrogen-progestin treatment (EPT) irrespective of hysterectomy documented that combined estrogen and a progestin therapy (medroxyprogesterone, acting through the P4 osteoblast receptor) caused two-thirds of a percentage greater spinal BMD gain per year than estrogen alone. This is the first time, to our knowledge, that a meta-analysis has been performed of RCT assessing BMD changes in studies that directly randomized menopausal women to ET versus EPT. These data support additive effects of MPA to those of estrogen on gain in spinal BMD. These publications, however, did not provide histomorphometric or bone biomarker data to assess the mechanism for the MPA-added BMD gain. However, all except one (0.3 mg/d) of the estrogen doses are known to suppress bone resorption[28]. RCT biomarker data further show that MPA does not decrease the very high resorption following premenopausal ovariectomy[32]. Since MPA acts through the osteoblast P4R[19], it likely stimulated bone formation[33].

Higher doses of MPA than 10 mg/d, however, may stimulate the osteoblast glucocorticoid receptor (e.g. 20 mg/d cyclic MPA in[27]) thus inhibiting bone formation[34]. MPA may also bind to the osteoblast androgen receptor (AR)[35]; androgens have bone-formation stimulating effects[36]. However, MPA appears to bind more strongly to the P4R than to the AR[35]. Most recently, additional mechanisms have been discovered, by which progesterone and its metabolites influence the effect of estrogen-receptor binding to the nuclear DNA, increasing our understanding of intracellular crosstalk of estrogen and progesterone receptors[37].

These results of estrogen-progestin menopausal therapy parallel observational prospective studies of spine BMD changes in premenopausal women with regular cycles but ovulatory disturbances (estradiol dominant) versus normally ovulatory menstrual cycles (with balanced estradiol and progesterone)[17]. In that analysis, significantly more negative spinal BMD changes (-0.86%/y, p=0.040) occurred in those with usually regular cycles but more frequent ovulatory disturbances and thus absent or lower progesterone levels[17]. This RCT meta-analysis result is also analogous to results of other therapies in which anti-catabolic agents are combined with anabolic ones[23].

An RCT in otherwise healthy, normal-weight premenopausal women with hypothalamic amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea and regular cycles but ovulatory disturbances showed significantly greater spinal BMD gain on cyclic MPA therapy versus placebo (+2.2% vs -2.0%/y; ANOVA P=0.0001)[38]. Thus there already is Level 1 evidence that MPA increases spinal BMD in premenopausal women with abnormal cycles or ovulation.

Although anti-catabolic therapies such as ET, denosumab and various bisphosphonates significantly increase BMD and effectively decrease fractures[39-41], it has been hypothesized that the catabolism/anabolism imbalance or the high mineralization they may cause could increase the risk for “adynamic” or brittle bones[42]. The ideal osteoporosis therapy may be both anti-catabolic and anabolic[23,43].

Fracture prevention is the ultimate goal of osteoporosis therapy, thus the question: is the +0.68%/y greater spinal BMD gain on EPT versus ET clinically important in preventing fragility fractures? A meta-analysis of anti-catabolic therapy-related BMD gains showed that a 1% spinal BMD increase correlated with an 8% decrease in non-vertebral fractures[44]. Although measurements of BMD and bone strength intrinsically differ, these data suggest there may be a greater decrease in fracture risk on EPT than on ET. Women’s Health Initiative hormonal RCT data suggest similar BMD and fracture prevention results on ET and EPT each compared versus its own placebo, but they did not directly compare ET with EPT[5,6]. Long-term WHI follow-up data, however, showed significant hip fracture prevention persisted for a longer duration in those previously on EPT compared with those who were on ET in the past[41].

Anabolic treatment may have a stronger fracture-prevention effect than anti-catabolic therapy; e.g., an RCT recently showed the BMD change/spine fracture prevention effect of parathyroid hormone (anabolic) was greater than that of alendronate (anti-catabolic)[45]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of RCT of incident fracture on OHT suggested greater decreased absolute fracture risk on EPT[1]. Thus the additional BMD gain from osteoanabolic MPA or progesterone co-therapy with an anti-catabolic therapy is likely important for fracture prevention. RCT data are needed and remain to be performed.

It is a strength of this study that we performed comprehensive literature searches and a quantitative comparison of two formerly common hormonal osteoporosis therapies. Although no longer recommended for osteoporosis treatment or prevention[1], EPT or ET continue to be important for treatment of intense menopausal hot flushes/night sweats (vasomotor symptoms, VMS). Another strength is that we limited progestins, given their wide heterogeneity[35], to those acting through the osteoblast P4R.

The limitations of this study are that, despite the millions of menopausal women who have used OHT, only about 1000 women were studied by direct randomization to ET or EPT. It is a limitation that BMD change on ET has primarily been studied with conjugated equine estrogen and only one study in this meta-analysis used oral micronized estradiol. It is also a limitation that EPT in comparison with ET has only been studied with MPA as the progesterone/progestin and not with oral micronized progesterone or the other progestin (e.g. dydrogesterone) neither of which has increased breast cancer risk on estrogen-co-therapy[52]. These data are also limited by their high degree of heterogeneity that is likely biased by the small number of included studies[31]. However, our meta-analysis used a random-effects model that does not assume homogeneity of effects. Therefore these results are likely robust to heterogeneity.

Menopausal OHT, with estradiol and progesterone or other non-MPA progestins, continues to be indicated and commonly used for the treatment of symptomatic menopausal women with VMS[46] although it is no longer considered appropriate for the prevention or treatment of osteoporosis[5,6,47]. Related to this, it is important that a previous 1-year RCT directly comparing CEE versus MPA for VMS effects showed equivalent and effective control of hot flushes/night sweats on both single hormone therapies[48]. Also an RCT of oral micronized progesterone (alone) versus placebo showed significant VMS efficacy[49]. Current gynecology guidelines recommend that estrogen-treated menopausal women without a uterus should not be prescribed progesterone/progestin[46]. VMS treatment, however, is significantly more effective on EPT than ET in a meta-analysis of RCT[50]. A progesterone vs placebo RCT for VMS[49] also showed no significant short-term adverse effects on weight, blood pressure, lipids, coagulation or inflammation[51]. Progesterone with estrogen does not increase breast cancer risk[52,53], although MPA with estrogen does[5]. This breast cancer safety of estrogen/progesterone versus progestins was recently confirmed by systematic review and meta-analysis[54]. Also, estradiol/estrogen or EPT, ideally of bio-identical estradiol and progesterone, will continue to be prescribed for menopausal women who are younger than age 40 or have primary ovarian insufficiency[55].

We currently have many anti-catabolic therapies that increase BMD and prevent fractures. These agents, however, may also have negative immune effects[56]. Although combined anti-resorptive/anabolic therapies (i.e. denosumab or bisphosphonate plus parathyroid hormone) are promising[23], combined therapy increases treatment risks and limitations (e.g. the 2-year limited duration of parathyroid hormone therapy) and most involve a degree of patient burden (e.g. intravenous or subcutaneous injections or the fasting required for oral therapy). The spine BMD effects of these anti-catabolic therapies combined with progesterone deserve examination in randomized controlled trials.

In summary, this meta-analysis in more than 1000 menopausal women randomized directly to either estrogen alone (ET) or estrogen-progestin (EPT) documented that EPT had significantly and importantly greater spinal BMD gains than ET. The relevance of this observation is that, for spinal BMD change, progesterone (or osteoblast progesterone receptor acting progestins) have additive, positive effects with estradiol that are greater than the change on estradiol alone.

Acknowledgements

Drs. Darby Thompson and Harlan Campbell of EMMES Canada (Vancouver, BC) for research inspiration and statistical assistance early in the creation of this meta-analysis. We thank Drs. Gail Laughlin and Elizabeth Barrett-Connor for providing unpublished intent-to-treat data on CEE alone and with daily MPA from the PEPI trial.

Author roles

JcP conceived of the idea, with AG reviewed publications for inclusion, contacted other authors for intent-to-treat data and wrote the original and revised drafts of the manuscript; VRS-K advised on roles of EPT and ET in today’s therapy and reviewed/revised drafts of manuscript; DG created the original search strategy and assisted in the PRISMA Figure; JDA provided advice about potential publications and reviewed/revised drafts of manuscript; SK commented on mechanisms and benefits and drawbacks of osteoporosis therapies; AG performed the follow-up literature search, with JcP decided on publication inclusion, performed the meta-analysis and reviewed/revised drafts of the manuscript. All authors have approved the submitted manuscript.

This Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research-based study was without additional funding.

Footnotes

JC Prior, VR Seifert-Klauss, D Giustini and A Goshtasebi have no conflicts of interest. S Kalyan has financial interests in the form of corporate appointment and also is the Director of Scientific Innovation of Qu Biologics Inc (privately held, clinical stage biotechnology company). J Adachi has financial interests in the form of consultancies with Amgen, Eli Lilly and Merck.

Edited by: F. Rauch

References

- 1.Marjoribanks J, Farquhar C, Roberts H, Lethaby A. Long term hormone therapy for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD004143. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004143.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells G, Tugwell P, Shea B, et al. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. V. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of hormone replacement therapy in treating and preventing osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(4):529–539. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albright F, Smith PH, Richardson AM. Postmenopausal osteoporosis - its clinical features. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1941;116:2465–2474. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eastell R. Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):736–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803123381107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in health postmenopausal women: prinicple results from the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Control trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1701–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riggs BL, Jowsey J, Kelly PJ, Jones JD, Maher FT. Effect of sex hormones on bone in primary osteoporosis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1969;48:1065–1072. doi: 10.1172/JCI106062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aitken JM, Hart DM, Lindsay R. Oestrogen replacement therapy for prevention of osteoporosis after oophorectomy. Br Med J. 1973;3:515–518. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5879.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts NB, Nolan JC, Brennan JJ, Yang HM. Esterified estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. Relationships of bone marker changes and plasma estradiol to BMD changes: a two-year study. Menopause. 2000;7(6):375–382. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilezikian JP, Matsumoto T, Bellido T, et al. Targeting bone remodeling for the treatment of osteoporosis: summary of the proceedings of an ASBMR workshop. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(3):373–385. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parfitt AM. The coupling of bone formation to bone resorption: a critical analysis of the concept and of its relevance to the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Metab Bone Dis Rel Res. 1982;4:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0221-8747(82)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen PR, Andersen TL, Pennypacker BL, Duong LT, Engelholm LH, Delaisse JM. A supra-cellular model for coupling of bone resorption to formation during remodeling: lessons from two bone resorption inhibitors affecting bone formation differently. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;443(2):694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parfitt AM. Quantum concept of bone remodelling and turnover: implications for the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Calc Tiss Res. 1979;28:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02441211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endometrial histology in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. JAMA. 1996;275(5):370–375. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530290040035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prior JC. Progesterone or progestin as menopausal ovarian hormone therapy: recent physiology-based clinical evidence. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2015;22(6):495–501. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalyan S, Prior JC. Bone changes and fracture related to menstrual cycles and ovulation. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2010;20(3):213–233. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v20.i3.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li D, Hitchcock CL, Barr SI, Yu T, Prior JC. Negative Spinal Bone Mineral Density Changes and Subclinical Ovulatory Disturbances - Prospective Data in Healthy Premenopausal Women With Regular Menstrual Cycles. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36(137):147. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxt012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prior JC. Progesterone as a bone-trophic hormone. Endocr Rev. 1990;11:386–398. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-2-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verhaar HJJ, Damen CA, Duursma SA, Schevens BAA. A comparison of the actions of progestins and estrogens on growth and differentiation of normal adult human osteoblast-like cells in vitro. Bone. 1994;15:307–311. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindsay R. The lack of effect of progestogen on bone. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:215–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallagher JC, Kable WT, Goldgar D. Effect of progestin therapy on cortical and trabecular bone: comparison with estrogen. Am J Med. 1991;90(2):171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grey A, Cundy T, Evans M, Reid I. Medroxyprogesterone acetate enhances the spinal bone density response to estrogen in late post-menopausal women. Clin Endocr. 1996;44:293–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.667488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eastell R, Walsh JS. Is it time to combine osteoporosis therapies? Lancet. 2013;382(9886):5–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62166-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemus AE, Enriquez J, Hernandez A, Santillan R, Perez-Palacios G. Bioconversion of norethisterone, a progesterone receptor agonist into estrogen receptor agonists in osteoblastic cells. J Endocrinol. 2009;200(2):199–206. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prior JC, Kalyan S, Seifert-Klauss V. Randomized Trials Show Greater Increases in Bone Mineral Density on Estrogen-Progestin than Estrogen alone-co-therapy increases bone formation. JBMR. 2013;28(Suppl 1) [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of hormone therapy on bone mineral density. Results from the postmenopausal estrogen/progestin interventions (PEPI) trial. JAMA. 1996;276(17):1389–1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adachi JD, Sargeant EJ, Sagle MA, et al. A double-blind randomised controlled trial of the effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone density of women taking oestrogen replacement therapy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:64–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb10651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kleerekoper M, Pickar JH. Effect of lower doses of conjugated equine estrogens with and without medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone in early postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2002;287:2668–2676. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu JH, Muse KN. The effects of progestins on bone density and bone metabolism in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(4):1316–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizunuma H, Okano H, Soda M, et al. Prevention of postmenopausal bone loss with minimal uterine bleeding use low dose continuous estrogen/progestin therapy: a 2-year prospective study. Maturitas. 1997;27:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(97)01110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Hippel PT. The heterogeneity statistic I(2) can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:35. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prior JC, Vigna YM, Wark JD, et al. Premenopausal ovariectomy-related bone loss: a randomized, double-blind one year trial of conjugated estrogen or medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Bone Min Res. 1997;12(11):1851–1863. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.11.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidmayr M, Magdolen U, Tubel J, Kiechle-Bahat M, Burgkart R, Seifert-Klauss V. Progesterone Enhances Differentiation of Primary Human Osteoblasts in Long-Term Cultures. The Influence of Concentration and Cyclicity of Progesterone on Proliferation and Differentiation of Human Osteoblasts in Vitro. Geburtsh Fraunenheilk. 2008;68:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishida Y, Heersche JN. Pharmacologic doses of medroxyprogesterone may cause bone loss through glucocorticoid activity: an hypothesis. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:601–605. doi: 10.1007/s001980200080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanczyk FZ, Hapgood JP, Winer S, Mishell DR., Jr Progestogens used in postmenopausal hormone therapy: differences in their pharmacological properties, intracellular actions, and clinical effects. Endocr Rev. 2013;34(2):171–208. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vandenput L, Swinnen JV, Boonen S, et al. Role of the androgen receptor in skeletal homeostasis: the androgen-resistant testicular feminized male mouse model. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(9):1462–1470. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohammed H, Russell IA, Stark R, et al. Progesterone receptor modulates ERalpha action in breast cancer. Nature. 2015;523(7560):313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature14583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prior JC, Vigna YM, Barr SI, Rexworthy C, Lentle BC. Cyclic medroxyprogesterone treatment increases bone density: a controlled trial in active women with menstrual cycle disturbances. Am J Med. 1994;96:521–530. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cranney A, Guyatt G, Griffith L, Wells G, Tugwell P, Rosen C. Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. IX: Summary of meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(4):570–578. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-9002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cauley JA, Robbins J, Chen Z, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290(13):1729–1738. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.13.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Health Outcomes During the Intervention and Extended Poststopping Phases of the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shane E, Burr D, Ebeling PR, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(11):2267–2294. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cosman F, Eriksen EF, Recknor C, et al. Effects of intravenous zoledronic acid plus subcutaneous teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(3):503–511. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hochberg MC, Greenspan S, Wasnich RD, Miller P, Thompson DE, Ross PD. Changes in bone density and turnover explain the reductions in incidence of nonvertebral fractures that occur during treatment with antiresorptive agents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(4):1586–1592. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Body JJ, Gaich GA, Scheele WH, et al. A randomized double-blind trial to compare the efficacy of teriparatide [recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1-34)] with alendronate in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(10):4528–4535. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The North American Menopause Society. The 2012 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society. [Miscellaneous Article] Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824b970a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, et al. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 2010;182(17):1864–1873. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prior JC, Nielsen JD, Hitchcock CL, Williams LA, Vigna YM, Dean CB. Medroxyprogesterone and conjugated oestrogen are equivalent for hot flushes: a 1-year randomized double-blind trial following premenopausal ovariectomy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112(10):517–525. doi: 10.1042/CS20060266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hitchcock CL, Prior JC. Oral Micronized Progesterone for Vasomotor Symptoms in Healthy Postmenopausal Women - a placebo-controlled randomized trial. Menopause. 2012;19:886–893. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318247f07a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacLennan AH, Broadbent JL, Lester S, Moore V. Oral oestrogen and combined oestrogen/progestogen therapy versus placebo for hot flushes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD002978. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002978.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prior JC, Elliott TG, Norman E, Stajic V, Hitchock CL. Progesterone therapy, endothelial function and cardiovascular risk factors: a 3-month randomized, placebo-controlled trial in healthy early postmenopausal women. PLOS One. 2014;9:e84698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: results from the E3N cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(1):103–111. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9523-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cordina-Duverger E, Truong T, Anger A, et al. Risk of breast cancer by type of menopausal hormone therapy: a case-control study among post-menopausal women in France. PLOS One. 2013;8(11):e78016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asi N, Mohammed K, Haydour Q, et al. Progesterone vs. synthetic progestins and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0294-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crofton PM, Evans N, Bath LE, et al. Physiological versus standard sex steroid replacement in young women with premature ovarian failure: effects on bone mass acquisition and turnover. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;73(6):707–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalyan S, Quabius ES, Wiltfang J, Monig H, Kabelitz D. Can peripheral blood gammadelta T cells predict osteonecrosis of the jaw? An immunological perspective on the adverse drug-effects of aminobisphosphonate therapy. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;28:728–735. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]