Abstract

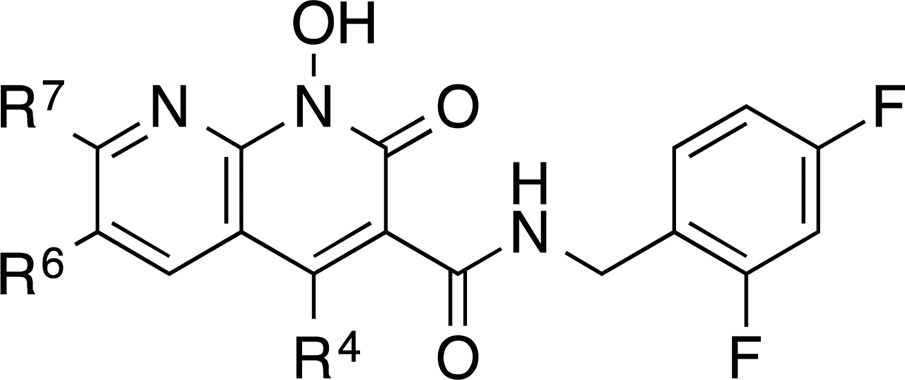

Integrase mutations can reduce the effectiveness of the first-generation FDA-approved integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs), raltegravir (RAL) and elvitegravir (EVG). The second-generation agent, dolutegravir (DTG), has enjoyed considerable clinical success; however, resistance-causing mutations that diminish the efficacy of DTG have appeared. Our current findings support and extend the substrate envelope concept that broadly effective INSTIs can be designed by filling the envelope defined by the DNA substrates. Previously, we explored 1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamides as an INSTI scaffold, making a limited set of derivatives, and concluded that broadly effective INSTIs can be developed using this scaffold. Herein, we report an extended investigation of 6-substituents as well the first examples of 7-substituted analogues of this scaffold. While 7-substituents are not well-tolerated, we have identified novel substituents at the 6-position that are highly effective, with the best compound (6p) retaining better efficacy against a broad panel of known INSTI resistant mutants than any analogues we have previously described.

Introduction

HIV-1 integrase (IN) plays a key role in the viral life cycle, inserting the double-stranded DNA that is generated by reverse transcription of the viral RNA genome into the genome of the host cell.1 Integration is essential for viral replication, and for this reason, IN is a therapeutic target for the treatment of HIV infections. To date, three HIV IN antagonists have been approved for clinical use: raltegravir (RAL, 1), elvitegravir (EVG, 2), and dolutegravir (DTG, 3) (Figure 1).2−4 These drugs belong to a class of compounds called integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) because they inhibit DNA strand transfer (ST), the second step of integration catalyzed by IN, rather than the first step, the 3′-processing reaction (3′-P).5−8 Development of drug resistance mutations is a common problem in antiviral therapy and, not surprisingly, mutations affecting the susceptibility of the virus to RAL and EVG have rapidly emerged.9−11 However, the second-generation inhibitor, DTG, retains potency against some but not all RAL/EVG resistant HIV variants.12−16 Therefore, the development of new small molecules that have minimal toxicity and improved efficacy against the existing resistant mutants remains an important research objective.17

Figure 1.

HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Colored areas indicate regions of intended correspondence.

Retroviral integration is mediated by IN multimers that are assembled on the viral DNA ends, forming a stable synaptic complex, also referred to as the intasome.18−21 The INSTIs only bind to the active site of IN when the processed viral DNA ends are appropriately bound to the intasome.8,22 The way in which INSTIs bind to the intasome was elucidated by solving crystal structures of the orthologous retroviral IN from the prototype foamy virus (PFV).19,23,24 The INSTIs are “interfacial” inhibitors; they bind to the active site of IN and interact with the bound viral DNA following the 3′-processing step.8,19,25 Essential structural features that contribute to the binding of INSTIs include an array of three heteroatoms (highlighted in red, Figure 1) that chelate the two catalytic Mg2+ ions in the IN active site and a halobenzyl side chain (halophenyl portion highlighted in blue, Figure 1) that stacks with the penultimate nucleotide (a deoxycytidine) at the 3′ end of the viral DNA.8,19 We have recently shown that the 1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide motif (4) can serve a useful platform for developing HIV-1 IN inhibitors that retain high efficacy against the RAL/EVG-resistant mutants.26,27 We initially examined the properties of a series of analogues related to structure 4 by varying the substituents at the 4-position. Our objective was to identify compounds that retain efficacy against the mutations Y143R, N155H, and Q148H/G140S, which have been associated with clinical resistance to RAL,27 and some of these mutations also play a role in the development of resistance against DTG.28 This approach yielded compounds including 4a–d, which are approximately equivalent to RAL in their potency against recombinant wild-type (WT) HIV-1 IN in biochemical assays. However, the small molecules also showed improved antiviral efficacies against the Y143R and N155H mutants in cell-based assays.26,27 Although antiviral efficacies against the Q148H/G140S double mutant were also improved relative to RAL, the new compounds were inferior to DTG, prompting us to continue our developmental efforts.

Structural studies using the PFV intasome have revealed that the tricyclic system of DTG is sufficiently extended to make contacts with G187 in the β4−α2 loop of PFV IN (G118 in IN).23 It has been argued that the interactions with this region may contribute to the improved properties of DTG and other second-generation INSTIs.4,23,29,30 Therefore, we considered that adding functionality to either the 6- or 7-positions of 4 could interact with the same region of the catalytic site (highlighted in green and cyan, respectively, in the structures of DTG and 4, Figure 1). In a preliminary work, we modified the 6-position of 4 and showed that adding linear side chains bearing terminal hydroxyl groups can improve antiviral efficacies against the Q148H/G140S double mutant to levels approaching that of DTG.31 Furthermore, depending on the 6-substituent, compounds could retain essentially all of their antiviral potency against a more extensive panel of HIV-1-based vectors that carry the major DTG-resistant IN mutants, including the G118R, T66I, E92Q, R263K, and H51Y single mutants and the H51Y/R263K double mutant.17,32−34 These data have two important implications: First, 6-substituents can have an important role in maintaining antiviral efficacy against resistant mutant forms of IN. Second, compounds that are broadly effective against mutant forms of IN bind in ways that involve substrate mimicry and, when bound, fit within the “substrate envelope”.31,35 However, the data were confined to a small number of 6-modificaitons that had limited chemical diversity. Given the potential promise of 6-substituents, we felt that it was important to more thoroughly examine this position and, accordingly, we describe here an extensive set of 6-modifications (designated as the 6 series analogues, Figure 1). We were also interested in examining substituents at the 7-position of 4 because these could potentially afford an alternate way to engage G118 in the β4−α2 loop of IN. We present the first examination of compounds that have modifications at the 7-position (designated as the 5 series analogues). To provide a more complete SAR study, we have also introduced various functionalities at the 4-position in combination with various 6- and 7-substitutents. These efforts have resulted in one of the most potent and effective compounds that we have developed to date. This work sheds additional light on enzyme–inhibitor interactions that can contribute to retention of efficacy against strains of virus that contain mutant forms of IN resistant to the approved INSTIs.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

To prepare our 7-substituted analogues 5a–i, we employed 2,6-dichloronicotinic acid (7) as the starting material. The 6-chloro group of 7 was converted into the final 7-substituent in two ways. In one route, the 6-chloro moiety was displaced with methoxyl (KOtBu in MeOH),36 and this was followed by esterification of the 3-carboxy group to yield 8 (Scheme 1). In the second route, the 3-carboxyl group of 7 was first converted directly to the 3-methyl ester. In both cases, the 2-chloro group was then displaced with BnONH2 to give the corresponding 2-benzyloxyamine-containing derivatives (10a and 9, respectively). The 6-chloro-substituents of the second series 9 were transformed into the corresponding 6-piperidinyl and 6-morpholino derivatives (10b and 10c, respectively) by heating with DMF solutions of piperidine or morpholine. Using a procedure similar to those we previously reported (Scheme 1),26,27,31 intermediates 10a–c were transformed to the 4-hydroxy (5a–c), 4-amino (5d–f), and 4-[2-(methyl glycinate)] (5g–i) final products.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 4,7-Bis-Substituted Analogues 5a–5i.

Reagents and conditions: (i) KOtBu, MeOH, 65 °C; (ii) H2SO4, MeOH; (iii) BnONH2, DIEA, dioxane, 110 °C; (iv) (b) piperidine or (c) morpholine, DMF, 80 °C; (v) ClCOCH2CO2CH3, TEA, DCM; (vi) NaOMe, MeOH; (vii) 2,4-diF-BnNH2, DMF, 140 °C; (viii) TsCl, DIEA, MeCN; (ix) RNH2, DIEA, DMF, 50 °C, R = 2,4-diMeOBn (a) or CH2CO2Me (b); (x) TFA, DCM; (xi) H2, 10% Pd/C, MeOH.

We transformed the 6-bromo analogues (17a–c, Scheme 2) into a variety of 6-substituted INSTIs by coupling alkynes and alkenes using Sonogashira and Heck coupling chemistries.31 In addition to the 6-substituted products with a 4-hydroxyl (6a), we prepared analogues having a free amine at the 4-position (6b–p) as well as analogues with 4-[2-(methyl glycinate)]amine (6q) and 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)amine (6r–t) (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 4,6-Bis-Substituted Analogues 6a–6t.

Reagents and conditions: (i) TsCl, Et3N, CH3CN; (ii) RNH2, DIEA, DMF, 50 °C, R = 2,4-diMeOBn (DMP) (a), CH2CH2OH (b), or CH2CO2Me (c); (iii) alkyne, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, DIEA, CuI, DMF, 70 °C or alkene, Pd(OAc)2, TEA, PPh3, DMF, 100 °C; (iv) TFA, DCM; (v) H2, 10% Pd/C, MeOH.

Evaluation of New Derivatives Using in Vitro IN Catalytic Assays and Single-Round Virus Replication Assays

We designed compounds 5a–i to examine the effects of substituents at the 4-position (hydroxyl, amine, or methyl glycinate) in combination with modifications of the 7-position (methoxyl, piperidinyl, or morpholino). We evaluated the compounds by in vitro IN activity assays that utilize 32P-radiolabeled oligonucleotides (Table 1).37 We also tested the potency of the compounds in single-round replication assays that employ HIV-1 vectors carrying WT IN. We evaluated the antiviral potencies of a subset of the compounds against HIV-1 vectors carrying the canonical Y143R, N155H, and Q148H/G140S mutations that are associated with high-level HIV-1 resistance to RAL and virological failure in patients (Table 2).17,32−34,38,39 As we recently reported, compounds that lack substituents at the 6- and 7-positions and have a hydroxyl group at the 4-position (5′a) showed lower potencies in the ST assay and poorer antiviral potencies than the corresponding 4-amino-containing compound (5′d) (Tables 1 and 2).26,27 In our current work, we found that a compound with a 4-[2-(methyl glycinate)] modification of the 4-amino group (5′g) retained its enzymatic potency in these assays relative to 5′d. Bulky substituents at the 7-position (5b, 5c, 5e, 5f, 5h. and 5i, Table 1) diminished potency by three orders of magnitude relative to the corresponding unsubsituted analogues (5′a, 5′d, and 5′g, respectively). Although a 7-methoxyl group was better tolerated (compare with 5a, 5d, and 5g), in all cases there was a reduction in the antiviral potency (Table 2).

Table 1. Inhibitory Potencies of Compounds Using an in Vitro IN Assaya.

| in vitro

(IC50 μM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | R4 | R6 | R7 | 3′-P | ST |

| 5′ab | OH | H | H | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.055 ± 0.008 |

| 5a | OH | H | OCH3 | 32 ± 4 | 0.033 ± 0.005 |

| 5b | OH | H | piperidinyl | >333 | 70 ± 16 |

| 5c | OH | H | morpholino | >333 | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

| 5′dc | NH2 | H | H | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.019 ± 0.002 |

| 5d | NH2 | H | OCH3 | 18 ± 2 | 0.011 ± 0.002 |

| 5e | NH2 | H | piperidinyl | >333 | 54 ± 18 |

| 5f | NH2 | H | morpholino | >333 | 54 ± 10 |

| 5′gc | NHCH2CO2CH3 | H | H | 0.71 ± 0.10 | 0.021 ± 0.011 |

| 5g | NHCH2CO2CH3 | H | OCH3 | 20 ± 2 | 0.042 ± 0.005 |

| 5h | NHCH2CO2CH3 | H | piperidinyl | >333 | 96 ± 40 |

| 5i | NHCH2CO2CH3 | H | morpholino | >333 | 6.2 ± 0.8 |

| 6a | OH | (CH2)5OH | H | 14.3 ± 1.1 | 0.012 ± 0.003 |

| 6′bd | NH2 | (CH2)5OH | H | 8.2 ± 1.2 | 0.0027 ± 0.0004 |

| 6b | NH2 | (CH2)3OAc | H | 14.3 ± 2.1 | 0.010 ± 0.002 |

| 6c | NH2 | (CH2)6OBz | H | 143 ± 14 | 3.3 ± 0.6 |

| 6d | NH2 | (CH2)3cHex | H | 289 ± 49 | 3.3 ± 0.5 |

| 6e | NH2 | (CH2)4Ph | H | 42 ± 4 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| 6f | NH2 | (CH2)2Ph | H | 48 ± 4 | 0.014 ± 0.003 |

| 6g | NH2 | (CH2)3N(CH3)2 | H | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 0.014 ± 0.002 |

| 6h | NH2 | (CH2)3O(CH2)2OH | H | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 0.0020 ± 0.0004 |

| 6i | NH2 | (CH2)2CO2H | H | NDe | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

| 6j | NH2 | (CH2)2CON(CH3)2 | H | ND | 0.008 ± 0.001 |

| 6k | NH2 | (CH)2CON(CH3)2 | H | ND | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

| 6l | NH2 | (CH2)2CONHiPr | H | ND | 0.002 ± 0.007 |

| 6m | NH2 | (CH)2CONHiPr | H | ND | 0.006 ± 0.005 |

| 6n | NH2 | (CH2)2CONH(CH2)2OH | H | ND | 0.002 ± 0.001 |

| 6o | NH2 | (CH)2CONH(CH2)2OH | H | ND | 0.007 ± 0.001 |

| 6p | NH2 | (CH2)2CO2CH3 | H | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 0.0031 ± 0.0005 |

| 6q | NHCH2CO2CH3 | (CH2)5OH | H | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

| 6r | NH(CH2)2OH | (CH2)5OH | H | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 0.0025 ± 0.0002 |

| 6s | NH(CH2)2OH | (CH2)5OAc | H | ND | ND |

| 6t | NH(CH2)2OH | (CH2)2CO2CH3 | H | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 0.0031 ± 0.0003 |

Table 2. Antiviral Potencies in Cells Infected with HIV-1 Vectors That Carry WT or Resistant IN Mutantsa.

| EC50 (nM/FCe) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | WT | Y143R | N155H | G140S/Q148H | CC50 (μM) |

| RAL (1)b | 4 ± 2 | 162 ± 16 (41×) | 154 ± 33 (39×) | 1900 ± 300 (475×) | >250 |

| EVG (2)b | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 7.9 ± 2.3 (1×) | 90 ± 18 (14×) | 5700 ± 1100 (891×) | >250 |

| DTG (3)b | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 1.2 (3×) | 3.6 ± 1.3 (2×) | 5.8 ± 0.5 (4×) | >250 |

| 5′ac | 6.2 ± 2.9 | 11 ± 2 (2×) | 31 ± 8 (5×) | 308 ± 125 (50×) | 137 ± 20 |

| 5a | 215 ± 31 | NDf | ND | ND | 12 ± 5 |

| 5′dc | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.6 (2×) | 5.3 ± 2.3 (5×) | 35 ± 9 (32×) | >250 |

| 5d | 30 ± 9 | 62 ± 26 (2×) | 400 ± 101 (13×) | 3600 ± 1600 (120×) | 2.2 ± 0.4 |

| 5′g | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 4.6 ± 2.2 (1×) | 19 ± 7 (5×) | 36 ± 16 (9×) | >250 |

| 5g | 32 ± 13 | 52 ± 13 (2×) | 1260 ± 320 (39×) | ND | 12 ± 3 |

| 6a | 24 ± 4 | 8.3 ± 1.7 (0.3×) | 32 ± 3 (1×) | 29 ± 10 (1×) | >250 |

| 6′bd | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.5 (2×) | 2.4 ± 0.8 (2×) | 9.4 ± 3.6 (7×) | >250 |

| 6b | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.9 (2×) | 5.4 ± 2.5 (4×) | 13 ± 8 (9×) | >250 |

| 6c | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 3.5 ± 1.2 (0.7×) | 5.4 ± 1.9 (1×) | 21 ± 7.8 (4×) | 14.4 ± 4.8 |

| 6d | 53 ± 14 | 112 ± 14 (2×) | 146 ± 37 (3×) | ND | 27.4 ± 3.1 |

| 6e | 11 ± 2 | 4.7 ± 0 (0.4×) | 39 ± 10 (4×) | 128 ± 44 (12×) | 13 ± 2 |

| 6f | 5.6 ± 1.9 | 5.5 ± 2.4 (1×) | 21 ± 5 (4×) | 140 ± 34 (25×) | 18 ± 2 |

| 6g | 6.1 ± 2.1 | 7.0 ± 2.3 (1×) | 29 ± 9 (5×) | 32 ± 5 (5×) | 5.0 ± 1.8 |

| 6h | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.6 (0.8×) | 4.2 ± 1.5 (3×) | 35 ± 3.7 (22×) | >250 |

| 6i | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 1.5 (3×) | 10 ± 3 (5×) | 195 ± 25 (103×) | >250 |

| 6j | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 6 ± 1 (5×) | 6.8 ± 1.6 (5×) | 16 ± 5 (12×) | >250 |

| 6k | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 7.2 ± 0.3 (5×) | 15 ± 2 (9×) | 58 ± 19 (36×) | >250 |

| 6l | 5 ± 1.3 | 8.7 ± 2.2 (2×) | 11 ± 4 (2×) | 13 ± 1 (3×) | >250 |

| 6m | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 11 ± 1 (5×) | 12 ± 3 (6×) | 286 ± 8 (136×) | >250 |

| 6n | 263 ± 52 | ND | ND | ND | >250 |

| 6o | 196 ± 32 | ND | ND | ND | >250 |

| 6p | 0.67 ± 0.15 | 0.67 ± 0.23 (1×) | 2.3 ± 0.2 (3×) | 5.3 ± 1.8 (8×) | >250 |

| 6q | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 1.6 (1×) | 11 ± 2 (3×) | 42 ± 2 (13×) | >250 |

| 6r | 13 ± 4.2 | 12 ± 2 (0.9×) | 15 ± 4 (1×) | 16 ± 7 (1×) | >250 |

| 6s | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 4.1 ± 1 (0.8×) | 10 ± 2 (2×) | 5.3 ± 2.1 (1×) | >100 |

| 6t | 4.1 ± 1 | 3.8 ± 1.9 (0.9×) | 3.9 ± 2.1 (1×) | 16 ± 4 (4×) | >250 |

Cytotoxic concentration resulting in 50% reduction in the level of ATP in human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells; EC50 values obtained from cells infected with lentiviral vector harboring WT or indicated IN mutants as previously reported.

Data has been reported previously.27

Data have been reported previously.26

Data have been reported previously.31

FC, fold change relative to WT = EC50 of mutants/EC50 of WT.

Not determined.

We recently described a series of structurally related 4-amino-containing INSTIs, which possess 6-substituents consisting of primary hydroxyl or sulfone groups tethered by alkyl chains of various lengths.31 The chemical diversity of these substituents was limited. To extend the diversity of the modifications at the 6-position, our current study examines analogues containing tethered acetoxy (6b), benzyloxy (6c), cyclohexyl (6d), phenyl (6e and 6f), dimethylamino (6g), carboxyl (6i), methyl ester (6p), and carboxamido having a variety of alkylamide groups (6j–6o) groups (Tables 1 and 2). Several of the resulting compounds retained low-nanomolar IC50 values in ST reactions. N,N-Dimethylpropylamine (6g, ST IC50 = 14 nM), propanoic acid (6i), propanoic amides (6j–o), and propanoic acid methyl ester (6p) as well as the reverse ester 6b displayed IC50 values of 10 nM or less in the ST assay. Tethering a phenyl ring with an ethylene chain maintained good inhibitory potency (6f, ST IC50 = 14 nM). However, appending phenyl or cyclohexyl groups by increasing spacer lengths reduced potency by as much as three orders of magnitude: three methylenes (cyclohexyl-containing 6d, ST IC50 = 3.3 μM), four methylenes (phenyl-containing 6e, ST IC50 = 2.0 μM), or longer (6c, ST IC50 = 3.3 μM) (Table 1). This result contrasts with our previous finding that appending a phenyl ring using a three-unit chain that contains a sulfone moiety can result in retention of high potency. In the latter case, a cocrystal structure with the PFV intasome revealed that the sulfone group causes the phenyl ring to adopt an unusual π–π stacking orientation, in which it is folded up under the naphthyridine ring system and fills the catalytic space more completely.31

Most 6-substituted analogues in our current study showed low nanomolar potencies against the WT enzyme in the in vitro ST assay and against a WT HIV-1 vector in the single-round infectivity assay (Tables 1 and 2, respectively). However, for the 6-tethered 2-hydroxyethylamides (6n and 6o), in vitro ST inhibitory potencies and antiviral potencies against a vector that replicates using WT IN differed considerably (IC50 < 10 nM as compared to EC50 ≥ 200 nM). Additionally, while analogues 6c, 6d, and 6e showed micromolar ST-inhibitory potencies in the in vitro assay, they were significantly more potent in the antiviral assay. The reasons for these discrepancies are not clear. Among the remaining compounds, 6p, with a 6-(CH2)2CO2CH3 substituent, exhibited the best antiviral profile against the panel of resistant mutants (Table 2). This derivative displayed a modest improvement in antiviral potency against a vector carrying a WT IN (EC50 = 0.67 nM) as compared to 6′b, which had been the most promising compound in work we recently reported.31 Inhibitor 6′b contains a 6-(CH2)5OH group and a primary amine at the 4-position. Adding 4-[2-(methyl glycinate)] or 2-hydroxyethyl substituents to the 4-amino group of 6′b did not improve the inhibitory profiles (compounds 6q and 6r, respectively), nor were the antiviral potencies improved by the addition of a 2-hydroxyethyl substituent to the 4-amino group of 6p to yield 6t (Table 2). Most 6-subsituted analogues were not cytotoxic within the range tested (Table 2). Exceptions were found with 6c, 6d, and 6e, which also showed anomalous discrepancies between their in vitro and antiviral potencies, and with 6f and 6g. The reasons for the greater cytotoxicities of these analogues are not clear.

An important component of our current study is to test the effects of substituents at the 7-position. Given proximity to the metal-chelating 8-aryl nitrogen, we were uncertain of what the effects such modifications would have. Bulky groups at the 7-position (5b, 5c, 5e, 5f, 5h, and 5i) resulted in from two to three orders of magnitude loss of inhibitory potency against the WT enzyme in vitro. These latter data were consistent with the bulky substituents causing a disruption of essential interactions with the catalytic metal ions. Of greater interest was our finding that 7-OCH3 substituents were well tolerated against WT enzyme in in vitro assays (see 5a, 5d, and 5g, Table 1).

Potencies of the New Compounds Against an Extended Set of Drug Resistant IN Mutants

We selected a subset of the analogues (6b, 6p, 6r, 6s, and 6t) for additional evaluation in single-round viral replication assays using HIV-1 vectors harboring single G118R, T66I, E92Q, R263K, and H51Y, or the double H51Y/R263K substitutions associated with DTG resistance (Table 3).17,32−34,38,39 For comparison, we also included 6′b, which was one of the most broadly effective of our previously reported inhibitors.31 The new compounds showed good antiviral potencies against the entire panel of mutants. Although several compounds appear to be promising, the most potent analogue (by a small margin) was the 6-methyl 3-propanoate-containing 6p, which showed a slightly better inhibitory profile against the first panel of mutants (Table 2) while also retaining greater inhibitory potency than DTG against the second, more extended panel of mutants (Table 4).

Table 3. Antiviral Potencies in Cells Infected with HIV-1 Vectors That Carry DTG-Resistant IN Mutantsa.

| EC50 (nM/FCc) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | WT | G118R | T66I | E92Q | R263K | H51Y | H51Y/R263K |

| RAL (1)b | 4 ± 2 | 36 ± 5 (9×) | 2.8 ± 0.4 (0.7×) | 30 ± 10 (8×) | 5.7 ± 2.3 (1×) | 3.4 ± 0.2 (0.9×) | 6 ± 2.3 (2×) |

| EVG (2)b | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 21 ± 10 (3×) | 66 ± 1 (10×) | 154 ± 34 (24×) | 10 ± 6 (2×) | 4.5 ± 2.1 (0.7×) | 53 ± 18 (8×) |

| DTG (3)b | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 13 ± 5 (8×) | 0.9 ± 0.8 (0.6×) | 2.3 ± 0.4 (1×) | 11 ± 3 (7×) | 3.2 ± 0.2 (2×) | 16 ± 2 (10×) |

| 6′bb | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 1.6 (4×) | 0.93 ± 0.24 (0.7×) | 3.8 ± 2.3 (3×) | 2.6 ± 0.1 (2×) | 3.8 ± 0.6 (3×) | 2.6 ± 1.4 (2×) |

| 6b | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 1.4 (4×) | 0.75 ± 0.07 (0.5×) | 1.2 ± 0.1 (1×) | 1.8 ± 0.3 (1×) | 0.8 ± 0.2 (0.6×) | 3.9 ± 1.9 (3×) |

| 6p | 0.67 ± 0.15 | 4.8 ± 1.5 (7×) | 0.53 ± 0.06 (0.8×) | 2.0 ± 1.1 (3×) | 0.5 ± 0.0 (0.7×) | 0.63 ± 0.30 (0.9×) | 2.4 ± 0.8 (3×) |

| 6r | 13 ± 4.2 | 24 ± 8 (2×) | 1.9 ± 0.07 (0.1×) | 6.5 ± 0.8 (0.5×) | 18 ± 2 (1×) | 11 ± 1.4 (0.8×) | 31 ± 10 (2×) |

| 6s | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 15 ± 2 (3×) | 1.2 ± 0.5 (0.2×) | 3.8 ± 1.3 (0.7×) | 3.6 ± 0.9 (0.7×) | 7.4 ± 0.9 (1×) | 15 ± 1.8 (3×) |

| 6t | 4.1 ± 1 | 4.8 ± 0.6 (1×) | 0.62 ± 0.15 (0.2×) | 2.7 ± 1.2 (0.7×) | 6.5 ± 0.8 (2×) | 6.9 ± 2.9 (2×) | 2.5 ± 0.1 (0.9×) |

Table 4. Comparison of Antiviral Potencies and Fold Improvement of Compounds 6′b and 6p Relative to DTG.

| EC50 (nM)a (fold improvementb) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| integrase mutants | DTG (3)c | 6′bc | 6p |

| WT | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.2 (0.81×) | 0.67 ± 0.15 (0.42×) |

| Y143R | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 0.5 (0.71×) | 0.67 ± 0.23 (0.16×) |

| N155H | 3.6 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 0.8 (0.67×) | 2.3 ± 0.2 (0.64×) |

| G140S/Q148H | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 3.6 (1.62×) | 5.3 ± 1.8 (0.91×) |

| G118R | 13 ± 5 | 5.3 ± 1.6 (0.41×) | 4.8 ± 1.5 (0.37×) |

| T66I | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 0.93 ± 0.24 (1.03×) | 0.53 ± 0.06 (0.59×) |

| E92Q | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 2.3 (1.65×) | 2.0 ± 1.1 (0.87×) |

| R263K | 11 ± 3 | 2.6 ± 0.1 (0.24×) | 0.5 ± 0.0 (0.05×) |

| H51Y | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.6 (1.19×) | 0.63 ± 0.30 (0.20×) |

| H51Y/R263K | 16 ± 2 | 2.6 ± 1.4 (0.16×) | 2.4 ± 0.8 (0.15×) |

Crystal Structures of the PFV Intasome in Complex with 5′g, 5g, and 6p

To understand how some of the current analogues interact with the active site of IN, we soaked PFV intasome crystals in the presence of 5′g, 5g, or 6p and refined the resulting structures (Table 5). We recently described a crystal structure of 5′d bound to the active site of PFV intasome.31 The inhibitor 5′g bound to PFV IN differs from the previously reported 5′d structure only in having a N-(methyl 2-glycinate)amine moiety at its 4-position and, predictably, the two compounds bind to the active site in a very similar fashion. Superposition with the DTG-bound structure confirmed that 8-naphthyridine nitrogen and 1-N-hydroxyl of 5′g take the place of the 6-oxo and 7-hydroxyl heteroatoms of DTG. The naphthyridine 2-oxo carbonyl of 5′g corresponds to the ring 8-oxo carbonyl of DTG (Figure 2A).23 However, the 4-N-(methyl 2-glycinate)amine group of 5′g extends into the region which is occupied by the first base of the scissile dinucleotide in viral DNA prior to 3′-P (designated A18 in the crystal structure, Figure 2A), which may be related to the ability of the compound to inhibit the 3′-P reaction.8 Therefore, an extended form of substrate mimicry may arise from the modification at the 4-position of 5′g, which was not seen in the cocrystal structure of 5′d.31 The idea that inhibitors that remain within the “substrate envelope” are particularly effective against resistant forms of the target enzyme was proposed by Schiffer and colleagues and is based on the idea that to be able to support viral replication, any mutant form of a viral enzyme must be capable of binding its normal substrate(s).35 Thus, if the bound inhibitor remains within an envelope defined by the substrate(s), the inhibitor is expected to retain some efficacy against mutant forms of the enzyme.40 Even though the original hypothesis was based on work with protease inhibitors, it seems likely that this principle can be applied broadly to antiviral compounds that bind at the active sites of essential viral enzymes. The 4-N-(methyl 2-glycinate) amine group of 5′g is situated near (within 5 Å) to the side chains of Y212 and P214 (residues corresponding to Y143 and P145 in HIV-1 IN) and to the adenosine base of the 3′ terminal viral DNA residue (A17), which adopts two alternative conformations in the crystal structure (Figure 2B). The interactions with the side chains are much less extensive in the cases of DTG (3) and 5′d. Extension into this region of the catalytic site is also seen with several highly potent INSTIs having diverse structures (see Figure S1 in Supporting Information).

Table 5. X-Ray Data Collection and Refinement Statisticsa.

| 5′g | 5g | 6p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | |||

| space group | P41212 | P41212 | P41212 |

| cell dimensions a, b, c (Å) | 159.6, 159.6, 124.1 | 158.6, 158.6, 123.1 | 160.5, 160.5, 123.8 |

| resolution range (Å) | 71.36–2.55 (2.62–2.55) | 79.29–2.60(2.67–2.60) | 71.77–2.77 (2.84–2.77) |

| Rmerge | 0.062 (1.49) | 0.025 (0.55) | 0.072 (1.075) |

| I/σ(I) | 26.6 (2.0) | 19.5 (1.4) | 18.9 (2.0) |

| completeness (%) | 99.8 (98.8) | 99.9 (99.7) | 98.8 (97.4) |

| redundancy | 11.5 (11.0) | 14.4 (14.2) | 7.2 (7.3) |

| Refinement | |||

| reflections (total/free) | 52565/2601 | 48670/2438 | 40988/2057 |

| R/Rfree | 0.179/0.207 | 0.176/0.204 | 0.177/0.205 |

| no. atoms | |||

| protein, DNA | 5150 | 5129 | 5127 |

| ligand | 159 | 132 | 146 |

| water | 229 | 109 | 87 |

| average B-factors (Å2) | 71.7 | 84.3 | 75.7 |

| protein, DNA | 71.3 | 83.9 | 74.9 |

| ligands | 91.8 | 117.23 | 107.3 |

| water | 67.2 | 78.9 | 68.3 |

| rmsd | |||

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.038 | 0.039 | 0.012 |

| bond angles (deg) | 0.56 | 0.76 | 1.38 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |||

| favored | 99 | 97 | 98 |

| outliers | 0 | 0 | 0.2 |

Each structure was determined from a single crystal. Data for the highest resolution shells are given in parentheses.

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of PFV intasome-bound inhibitors. (A) Bound 5′g (cream) with overlays showing the relative positions of pre-3′-P viral DNA (violet; PDB 4E7I) and DTG (3) (green; PDB 3S3M). The 4-N-(methyl 2-glycinate) moiety of 5′g is circled in red, highlighting its correspondence with the T+2 adenosine (A18) base of pre-3′-P viral DNA. (B) Bound 5′g with its 4-N-(methyl 2-glycinate) moiety shown as transparent spheres. Atoms within 5 Å (Y212 and P214 and A17 of 3′-P DNA) are shown in green as a stick diagram. For both A and B, metal ions are shown as solid blue spheres.

Prior structural studies using the PFV intasome showed that the tricyclic system of DTG makes contacts with G187 in the β4−α2 loop of PFV IN (G118 in IN), and it has been argued that the interactions with this region may contribute to the improved properties of DTG and other second-generation INSTIs.4,23,29,30 As has already been discussed, we thought that it might be possible to make useful contacts with the same region of the catalytic site by adding functionality to the 6- and 7-positions of 4. To this end, we introduced substituents at the 6- and 7-positions of 4 that could potentially recapitulate some of the desirable features of DTG (highlighted in green and cyan, respectively, in the structures of DTG and 4, Figure 1). We obtained the crystal structure of 6p bound to the PFV intasome because it represents the most potent 6-substituted analogue in our current study. The structure revealed that the 6-methyl 3-propanoate side chain of the compound is situated within the region defined by an envelope defined by both the pre-3′-P viral DNA and the host target DNA substrate (Figure 3). This is consistent with our recent report that 6-substituents of the compounds exhibiting the best antiviral profiles against the panel of resistant mutants bind within an envelope defined as the confluence of viral DNA substrates.31 The structure also shows that the methyl carboxylate group of 6p makes van der Waals interactions with the β4−α2 loop of IN, becoming sandwiched between main chain atoms of Q186 and G187 (residues corresponding to HIV-1 N117 and G118, respectively) and the side chain of Y212 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Crystal structures of 6p bound to the PFV intasome. Structures of the pre-3′-P viral DNA (violet; PDB 4E7I) and target complex host DNA substrate (gray; PDB 4E7K) are overlaid. The 6-(methyl 3-propanoate) group of 6p is circled in red, showing its correspondence with aspects of both pre-3′-P viral DNA and the host target DNA. Cofactor Mg2+ ions are shown as blue spheres; the structures of bound viral DNAs have been omitted for clarity.

Figure 4.

Crystal structures of PFV intasome-bound inhibitors. (A) Bound 5g (orange) with superimposed 6p (cyan) and DTG (3) (green; PDB 3S3M) showing closest distance to the Gly187 α-methylene (side chains of Asp186 and Gln187 shown in semitransparent), bound 3′-P DNAs have been omitted for clarity. (B) Superimposed bound 3′-P DNAs associated with A, circled in cyan are the oxygens in the C16–A17 phosphoryl linkages, whose engagement in electrostatic interactions with the side chain imidazole nitrogen of the N224H mutant (corresponding to IN mutant N155H) would be broken on binding of the INSTIs. (C) Bound 5g with superimposed pre-3′-P viral DNA (violet; PDB 4E7I) and target complex host DNA substrate (gray; PDB 4E7K), circled in red is the 7-OCH3, which protrudes outside the substrate envelope. Metal ions are shown as solid blue spheres.

To understand the effects of introducing a 7-OCH3 substituent, we solved the structure of 5g bound to the PFV intasome and overlaid the corresponding structure of DTG bound to the PFV intasome (Figure 4). We observed that the 7-OCH3 group of 5g is approximately 3.6 Å from the G187 residue in the β4−α2 loop, which compares favorably with DTG and 6p (approximately 3.9 and 3.7 Å, respectively, Figure 4A). The 7-OCH3 group of 5g did not appear to significantly alter the position of the metal chelating heteroatoms of 5g relative to 6p. However, it is not immediately obvious why 5g is more susceptible to the N155H mutation compared to 6p or to the more closely related 5′g. Because the N155 residue of HIV-1 IN corresponds to N224 in PFV IN, the X-ray crystal structure with the mutation N224H in PFV IN did show that the side chain of His224 interacts with a phosphoryl oxygen atom in viral DNA and that INSTI binding is accompanied by a loss of this contact.24 The associated energetic penalty may explain the loss potency of some compounds against N155H HIV-1 IN. In the cocrystal structure of PFV intasome with 5g, the location of this phosphoryl oxygen is nearly identical to that seen for 6p, 5′g, and DTG (Figure 4C). The abilities of some INSTIs to readjust in the active site of IN may help explain variations among in their susceptibilities of the different INSTIs to the N155H mutation.23,24,41

Conclusions

Earlier, we reported that the 1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide scaffold represents a potentially attractive platform for the development of INSTIs that retain good antiviral efficacy against a panel of viral vectors carrying resistant mutant forms of IN.26,27 More recently, we began an exploration of the effects of modifying the 6-position of our earlier compounds.31 We found that 6-substituents may play an important role in enhancing the maintenance of antiviral efficacy against drug-resistant mutant forms of IN. Furthermore, the most broadly effective compounds are substrate mimics that fit within the “substrate envelope.″ Our original purpose in synthesizing 6-substituents was to create additional interactions within areas of the catalytic region accessed by the third ring of DTG. However, the range of functionality reported in the prior paper was quite limited, consisting of primary hydroxyl groups tethered by linear polymethylene chains of varying lengths and a single tethered phenyl sulfone. We now report a much more extensive exploration of functionalities at the 6-position as well as the first examination of derivatives with modifications at the 7-position. We also tested whether the compounds could be improved by introduced by varying functionalities at the 4-position.

We observed that −OCH3 groups are somewhat better tolerated than bulky subsituents at the 7-position when examined in vitro against WT enzyme. However, compounds with 7-OMe groups showed significantly reduced antiviral potency when tested against viral vectors that carry the N155H mutation. We found that a variety of substituents can be added at the 6-position, which enhance the antiviral potencies of the compounds against the major RAL-, EVG-, and DTG-resistant IN mutants. Many of these compounds are not cytotoxic at the tested concentrations, and the best analogue, 6p, is the most effective in terms of its ability to inhibit the entire spectrum of IN mutants of any of the compounds we have described. The crystal structure of the PFV intasome with 6p bound supports the idea that interactions with the β4−α2 loop are important and that compounds that bind within the envelope defined by both the viral and host DNA substrates helps the compounds retain broad efficacy. We found that the 4-amine substituent in 5′g accesses a region of the active site of IN that would normally be occupied by the base of the T+2 adenosine of the viral DNA prior to the 3′-P cleavage, providing further support that binding within an envelope defined by the DNA substrates helps the compounds retain broad efficacy. Thus, our results will inform the design and development of next-generation INSTIs with broader efficacy against the known drug resistant mutants.

Experimental Section

General Procedures

Proton (1H) and carbon (13C) NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 400 MHz spectrometer or a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer and are reported in ppm relative to TMS and referenced to the solvent in which the spectra were collected. Solvent was removed by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure, and anhydrous solvents were obtained commercially and used without further drying. Purification by silica gel chromatography was performed using Combiflash with EtOAc–hexanes solvent systems. Preparative high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) was conducted using a Waters Prep LC4000 system having photodiode array detection and Phenomenex C18 columns (catalogue no. 00G-4436-P0-AX, 250 mm × 21.2 mm 10 μm particle size, 110 Å pore) at a flow rate of 10 mL/min. Binary solvent systems consisting of A = 0.1% aqueous TFA and B = 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile were employed with gradients as indicated. Products were obtained as amorphous solids following lyophilization. Electrospray ionization-mass spectrometric (ESI-MS) were acquired with an Agilent LC/MSD system equipped with a multimode ion source. Purities of samples subjected to biological testing were assessed using this system and shown to be ≥95%. High resolution mass spectrometric (HRMS) were acquired by LC/MS-ESI using LTQ-Orbitrap-XL at 30K resolution.

General Procedure I for the Synthesis of Carboxamides (5a–i and 6a–t)

Benzyl protected compounds (13, 15, 16, and 19) (0.1 mmol) were suspended in methanol (10 mL) and ethyl acetate (3 mL). One equivalent of Pd/C (10%) was added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature under hydrogen. When the starting material was disappeared (TLC), the crude mixture was filtered and washed by methanol. The filtrate was concentrated and purified by HPLC to provide final carboxamides (5a–i and 6a–t).

N-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-1,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (5a)

Treatment of 13a as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 30% B to 90% B over 30 min; retention time = 25.5 min) provided 5a as a white fluffy solid (22% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.00 (s, 1H), 10.42 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (dd, J = 8.7, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 9.8, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.83–6.81 (m, 1H), 4.62 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.02 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 378.1 (MH+).

N-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-1,4-dihydroxy-2-oxo-7-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (5b)

Treatment of 13b as outlined in general procedure I, and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 50% B to 90% B over 30 min; retention time = 24.0 min) provided 5b as a white fluffy solid (13% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.52 (bs, 1H), 10.36 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.25–7.19 (m, 1H), 7.04 (dd, J = 9.3, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 4.54 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.74 (s, 4H), 1.61 (bs, 2H), 1.52 (bs, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 431.2 (MH+).

N-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-1,4-dihydroxy-7-morpholino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (5c)

Treatment of 13c as outlined in general procedure I, and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 30% B to 90% B over 30 min; retention time = 24.3 min) provided 5c as a white fluffy solid (30% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.60 (s, 1H), 10.36 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 8.01 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.25–7.19 (m, 1H), 7.06–7.02 (m, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 4.54 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.73 (s, 4H), 3.65 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 433.1 (MH+).

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (5d)

Treatment of 16a as outlined in general procedure I, and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 30% B to 75% B over 30 min; retention time = 22.4 min) provided 5d as a white fluffy solid (37% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.60 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 10.51 (bs, 1H), 8.48 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.22–7.17 (m, 1H), 7.02 (td, J = 8.5, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.94 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 377.1 (MH+).

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-7-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (5e)

Treatment of 16b as outlined in general procedure I, and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 50% B to 70% B over 30 min; retention time = 20.6 min) provided 5e as a white fluffy solid (49% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.63 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 8.19 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.02 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.69 (bs, 4H), 1.59 (bs, 2H), 1.50 (bs, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 430.2 (MH+).

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-7-morpholino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (5f)

Treatment of 16c as outlined in general procedure I, and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 30% B to 65% B over 30 min; retention time = 24.0 min) provided 5f as a white fluffy solid (28% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.62 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 10.27 (bs, 1H), 10.19 (bs, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.02 (td, J = 8.2, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.66 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 8H). ESI-MS m/z: 432.1 (MH+).

Methyl 2-((3-((2,4-Difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-1-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)acetate (5g)

Treatment of 15a as outlined in general procedure I, and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 30% B to 80% B over 30 min; retention time = 23.7 min) provided 5g as a white fluffy solid (20% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.17 (bs, 1H), 10.61 (bs, 1H), 10.45 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.22–7.17 (m, 1H), 7.02 (td, J = 8.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 4.45 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 3.94 (s, 3H), 3.63 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 449.1 (MH+).

Methyl 2-((3-((2,4-Difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-7-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)acetate (5h)

Treatment of 15b as outlined in general procedure I, and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 50% B to 70% B over 30 min; retention time = 22.9 min) provided 5h as a white fluffy solid (29% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.45 (bs, 1H), 10.70 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.22–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.02 (td, J = 8.6, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (bs, 2H), 4.44 (s, 2H), 3.70 (bs, 4H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 1.60 (bs, 3H), 1.51 (bs, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 502.2 (MH+).

Methyl 2-((3-((2,4-Difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-1-hydroxy-7-morpholino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)acetate (5i)

Treatment of 15c as outlined in general procedure I, and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 30% B to 70% B over 30 min; retention time = 26.0 min) provided 5i as a white fluffy solid (18% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.43 (bs, 1H), 10.66 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 10.31 (bs, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.02 (dd, J = 9.8, 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.66 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 4.47 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 4.45 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.66 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 8H), 3.63 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 504.2 (MH+).

N-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-1,4-dihydroxy-6-(5-hydroxypentyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6a)

Treatment of 1-(benzyloxy)-6-bromo-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-4-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide 17a(31) with commercially available pent-4-yn-1-ol as outlined in general procedures J and I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 30% B to 70% B over 30 min; retention time = 23.8 min) provided 6a as a white fluffy solid (46% yield, two steps). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.96 (bs, 1H), 10.52 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 8.70 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.09 (td, J = 8.5, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.63 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 3.37 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.73 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.65–1.59 (m, 2H), 1.46–1.42 (m, 2H), 1.35–1.28 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 434.1 (MH+). HRMS calcd C21H22F2N3O5 [MH+], 434.1522; found, 434.1507.

3-(5-Amino-6-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-8-hydroxy-7-oxo-7,8-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-3-yl)propyl Acetate (6b)

Treatment of 19a as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 30% B to 70% B over 30 min; retention time = 20.6 min) provided 6b as a white fluffy solid (71% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.69 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (s, 1H), 8.57 (s, 1H), 7.42 (dd, J = 15.6, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (t, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 4.05 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 2.00 (s, 3H), 1.97 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 447.1 (MH+). HRMS calcd C21H21F2N4O5 [MH+], 447.1475; found, 447.1477.

6-(5-Amino-6-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-8-hydroxy-7-oxo-7,8-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-3-yl)hexyl Benzoate (6c)

Protection of 1-(benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-4-((2,4-dimethoxybenzyl)amino)-6-(6-hydroxyhex-1-yn-1-yl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide31 (50 mg, 0.073 mmol) using benzoic anhydride (25 mg, 0.11 mmol) in pyridine (0.5 mL) (room temperature, 2 h) provided 6-(8-(benzyloxy)-6-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-5-((2,4-dimethoxybenzyl)amino)-7-oxo-7,8-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-3-yl)hex-5-yn-1-yl benzoate as a white solid (56 mg, 96% yield). [1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.99 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 10.69 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.67 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 8.07–8.05 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.68 (m, 2H), 7.57 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.40–7.36 (m, 4H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 6.86–6.79 (m, 2H), 6.48–6.46 (m, 2H), 5.26 (s, 2H), 4.75 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 4.60 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 4.41 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 2.54 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.99–1.93 (m, 2H), 1.84–1.78 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 787.3 (MH+).] After treatment as outlined in general procedure H and I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 55% B to 75% B over 30 min; retention time = 25.4 min), 6c was provided as a white fluffy solid (45% yield, two steps). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.69 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.54 (s, 1H), 7.94 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (dt, J = 8.7, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.42 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.26–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.06 (dd, J = 9.8, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 4.26 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.70–2.67 (m, 2H), 1.73–1.66 (m, 4H), 1.45–1.42 (m, 2H), 1.39–1.38 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 551.2 (MH+). HRMS calcd C29H29F2N4O5 [MH+], 551.2089; found, 551.2089.

4-Amino-6-(3-cyclohexylpropyl)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6d)

Treatment of 19b as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 50% B to 80% B over 30 min; retention time = 27.5 min) provided 6d as a white fluffy solid (40% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.63 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.47 (s, 1H), 7.36 (dd, J = 15.5, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.00 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.59 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 1.63–1.52 (m, 7H), 1.16–1.00 (m, 6H), 0.82–0.75 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 471.2 (MH+). HRMS calcd C25H29F2N4O3 [MH+], 471.2202; found, 471.2204.

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-6-(4-phenylbutyl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6e)

Treatment of 19c as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 40% B to 80% B over 30 min; retention time = 26.0 min) provided 6e as a white fluffy solid (27% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.69 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (s, 1H), 8.54 (s, 1H), 7.42 (dd, J = 15.5, 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.24–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 3H), 7.07 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.72 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.62 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.69 (dd, J = 14.8, 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.65–1.53 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 479.2 (MH+). HRMS calcd C26H25F2N4O3 [MH+], 479.1889; found, 479.1880.

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-6-phenethyl-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6f)

Treatment of 19d as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 40% B to 80% B over 30 min; retention time = 22.5 min) provided 6f as a white fluffy solid (65% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.69 (bs, 1H), 10.51 (bs, 1H), 8.61 (s, 1H), 8.53 (s, 1H), 7.45–7.42 (m, 1H), 7.35–7.32 (m, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 7.20–7.17 (m, 1H), 7.08–7.05 (m, 1H), 4.52 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 2.99 (bs, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 451.1 (MH+). HRMS calcd C24H21F2N4O3 [MH+], 451.1576; found, 451.1576.

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-6-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6g)

Treatment of 19e as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 30% B to 55% B over 30 min; retention time = 17.2 min) provided 6g as a white fluffy solid (52% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.68 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 10.57 (s, 1H), 8.62 (s, 1H), 8.57 (s, 1H), 7.42 (dd, J = 15.5, 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.27–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.07 (dd, J = 9.8, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.06 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 2.78 (s, 6H), 2.74 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.01 (dt, J = 15.7, 7.8 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 432.2 (MH+). HRMS calcd C21H24F2N5O3 [MH+], 432.1842; found, 432.1824.

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-6-(3-(2-hydroxyethoxy)propyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6h)

Treatment of 19f as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 30% B to 60% B over 30 min; retention time = 20.5 min) provided 6h as a white fluffy solid (86% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.69 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.59 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.52–7.35 (m, 1H), 7.24 (ddd, J = 10.5, 9.4, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (ddd, J = 10.4, 8.1, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.51 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 3.41 (dt, J = 7.5, 5.7 Hz, 4H), 2.76–2.73 (m, 2H), 1.92–1.86 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 449.1 (MH+). HRMS calcd C21H23F2N4O5 [MH+], 449.1631; found, 449.1631.

3-(5-Amino-6-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-8-hydroxy-7-oxo-7,8-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-3-yl)propanoic Acid (6i)

Treatment of 19g with aqueous NaOH and then as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 30% B to 50% B over 30 min; retention time = 19.5 min) provided 6i as a white fluffy solid (80% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.63 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 8.68–8.66 (m, 1H), 8.63–8.60 (m, 1H), 8.57 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.53 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.34 (m, 1H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.04–6.99 (m, 1H), 4.47 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 2.87 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.62 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 419.1 (MH+). HRMS calcd C19H17F2N4O5 [MH+], 419.1162; found, 419.1147.

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-6-(3-(dimethylamino)-3-oxopropyl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6j) and (E)-4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-6-(3-(dimethylamino)-3-oxoprop-1-en-1-yl)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6k)

Treatment of 18e as outlined in general procedures I and H and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 30% B to 45% B over 30 min) provided 6j and 6k as white fluffy solids. For 6j: retention time = 20.7 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.62 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 10.46 (brs, 1H), 8.56 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.00 (td, J = 8.6, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.90 (s, 3H), 2.84 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.74 (s, 3H), 2.65 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 446.2 (MH+). HRMS calcd C21H22F2N5O4 [MH+], 446.1634; found, 446.1617. For 6k: retention time = 24.1 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.63 (s, 1H), 10.53 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.94 (s, 2H), 7.49 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (dd, J = 12.2, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.01 (td, J = 8.9, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.14 (s, 3H), 2.89 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 444.1 (MH+). HRMS calcd C21H20F2N5O4 [MH+), 444.1478; found, 444.1475.

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-6-(3-(isopropylamino)-3-oxopropyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6l) and (E)-4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-6-(3-(isopropylamino)-3-oxoprop-1-en-1-yl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6m)

Treatment of 18f as outlined in general procedures I and H and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 30% B to 45% B over 30 min) provided 6l and 6m as white fluffy solids. For 6l: retention time = 23.0 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.62 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 10.46 (brs, 1H), 8.50 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (s, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.02–6.98 (m, 1H), 4.45 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.76–3.68 (m, 1H), 2.84 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.36 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 0.90 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H). ESI-MS m/z: 460.2 (MH+). HRMS calcd C22H24F2N5O4 [MH+], 460.1791; found, 460.1772. For 6m: retention time = 27.9 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.63 (s, 1H), 10.53 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.84 (s, 1H), 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.01 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.37–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.20–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.00 (td, J = 8.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.66 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.91 (td, J = 13.3, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 1.05 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H). ESI-MS m/z: 458.2 (MH+). HRMS calcd C22H22F2N5O4 [MH+], 458.1634; found, 458.1628.

4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-6-(3-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-3-oxopropyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6n) and (E)-4-Amino-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-6-(3-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-3-oxoprop-1-en-1-yl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6o)

Treatment of 18g as outlined in general procedures I and H and purification by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 20% B to 50% B over 30 min) provided 6n and 6o as white fluffy solids. For 6n: retention time = 22.1 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.56 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.25–7.19 (m, 1H), 7.06 (dd, J = 9.4, 7.7 Hz, 1H), 4.50 (s, 2H), 3.32 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.08 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.92 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.48 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 462.1 (MH+), 484.1 (MNa+). HRMS calcd C21H22F2N5O5 [MH+], 462.1584; found, 462.1562. For 6o: retention time = 23.9 min. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.63 (s, 1H), 10.53 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.85 (s, 1H), 8.83 (s, 1H), 8.09 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.03–6.98 (m, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (brs, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.40 (brs, 2H), 3.20 (dd, J = 11.9, 6.0 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 460.1 (MH+), 482.1 (MNa+). HRMS calcd C21H20F2N5O5 [MH+], 460.1427; found, 460.1421.

Methyl 3-(5-Amino-6-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-8-hydroxy-7-oxo-7,8-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-3-yl)propanoate (6p)

Treatment of 19g as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 30% B to 65% B over 30 min; retention time = 23.4 min) provided 6p as a white fluffy solid (72% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.68 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (s, 1H), 7.42 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.26–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.07 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.58 (s, 3H), 2.95 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 433.1 (MH+). HRMS calcd C20H19F2N4O5 [MH+], 433.1318; found, 433.1311.

Methyl 2-((3-((2,4-Difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-1-hydroxy-6-(5-hydroxypentyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)acetate (6q)

Treatment of 18i as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 30% B to 60% B over 30 min; retention time = 20.5 min) provided 6q as a white fluffy solid (82% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.22 (bs, 1H), 10.05 (bs, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.52 (dd, J = 15.6, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.24–7.11 (m, 1H), 7.00 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 4H), 3.59 (s, 3H), 3.32 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H), 2.62 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.61–1.47 (m, 2H), 1.45–1.33 (m, 2H), 1.32–1.18 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 505.2 (MH+). HRMS calcd C24H27F2N4O6 [MH+], 505.1893; found, 505.1889.

N-(2,4-Difluorobenzyl)-1-hydroxy-4-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-6-(5-hydroxypentyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (6r)

Treatment of 18j as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 25% B to 40% B over 30 min; retention time = 24.5 min) provided 6r as a white fluffy solid (22% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.98 (s, 1H), 10.52 (s, 1H), 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.37 (s, 1H), 7.50–7.47 (m, 1H), 7.24 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.50 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.70 (bs, 2H), 3.61 (bs, 2H), 3.38 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.69 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.63–1.60 (m, 2H), 1.46–1.44 (m, 2H), 1.33–1.24 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 477.2 (MH+). HRMS calcd C23H26F2N4O5 [MH+], 477.1944; found, 477.1944.

5-(6-((2,4-Difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-8-hydroxy-5-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-7-oxo-7,8-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-3-yl)pentyl Acetate (6s)

The mixture of 18j (74 mg, 0.13 mmol), triethylamine (109 μL, 0.79 mmol), and acetic anhydride (37 μL, 0.40 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) was stirred at room temperature (3 h). The crude mixture was purified by silica gel chromatography to provide 5-(8-(benzyloxy)-6-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-5-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-7-oxo-7,8-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-3-yl)pent-4-yn-1-yl acetate as a colorless oil (31 mg, 39% yield). [1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.00 (brs, 1H), 10.69 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 7.41–7.36 (m, 4H), 6.86–6.80 (m, 2H), 5.24 (s, 2H), 4.62 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 4.35 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.94 (dd, J = 10.6, 5.3 Hz, 2H), 3.83 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 2.60 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.11 (s, 3H), 1.90 (p, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 605.2 (MH+).] This compound was treated as outlined in general procedure I and purified by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 30% B to 55% B over 30 min; retention time = 24.1 min) to provide 6s as a white fluffy solid (12% yield, two steps from 18j). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.56 (brs, 1H), 10.29 (brs, 1H), 8.53 (s, 1H), 8.30 (s, 1H), 7.53–7.48 (m, 1H), 7.22 (t, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H), 7.07–7.03 (m, 1H), 4.48 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 4.17–4.15 (m, 2H), 3.81 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 3.38–3.36 (m, 2H), 2.68 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.97 (s, 3H), 1.64–1.57 (m, 2H), 1.47–1.41 (m, 2H), 1.33–1.29 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 519.2 (MH+), 541.1 (MNa+).

Methyl 3-(6-((2,4-Difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-8-hydroxy-5-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-7-oxo-7,8-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-3-yl)propanoate (6t)

Treatment of 18k as outlined in general procedure I and purification by preparative HPLC (linear gradient of 30% B to 50% B over 30 min; retention time = 21.0 min) provided 6t as a white fluffy solid (20% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.09 (bs, 1H), 10.54 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.57 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.43 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (dd, J = 15.4, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.26–7.21 (m, 1H), 7.09–7.05 (m, 1H), 4.50 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (s, 2H), 3.61 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 3.58 (s, 3H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.73 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 477.1 (MH+). HRMS calcd C23H26F2N4O5 [MH+], 477.1580; found, 477.1581.

Methyl 2-Chloro-6-methoxynicotinate (8)

Commercially available 2,6-dichloronicotinic acid 7 (3.1 g, 16 mmol) was added to the mixture of potassium t-butoxide (5.7 g, 48 mmol) in methanol (75 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred (65 °C, 24 h). The reaction mixture was concentrated and acidified using concentrated aqueous HCl. The crude mixture was filtered. The formed solid was collected to provide 2-chloro-6-methoxynicotinic acid as a white solid (2.8 g, 94% yield).36 [1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.33 (bs, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.92 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.52, 164.54, 147.69, 143.80, 120.02, 109.82, 54.86. ESI-MS m/z: 188.0 (MH+).] 2-Chloro-6-methoxynicotinic acid (2.8 g, 15 mmol) was suspended in thionyl chloride (20 mL). The suspension was stirred and refluxed (3 h). The reaction mixture was concentrated. The residue was mixed with methanol (20 mL). The mixture was refluxed (3 h) and concentrated. The crude residue was purified by silica gel chromatography to provide 8 as a colorless oil (2.5 g, 81% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.89 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.56, 164.25, 148.96, 142.60, 118.11, 108.96, 54.30, 52.09.

General Procedure A for the Synthesis of Methyl 2-((Benzyloxy)amino)-nicotinates (9 and 10a)

2-Chloronicotinates (7 and 8) (12 mmol) were mixed with O-benzylhydroxylamine (48 mmol) and DIEA (36 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred (110 °C, 18 h). The crude mixture was purified by silica gel chromatography to provide methyl 2-((benzyloxy)amino)-nicotinates (9 and 10a).

Methyl 2-((Benzyloxy)amino)-6-chloronicotinate (9)

Treatment of methyl 2,6-dichloronicotinate, which was prepared from commercially available 2,6-dichloronicotinic acid 7 in 91% yield based on known method.421H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 163.95, 152.88, 149.74, 142.46, 125.12, 122.79, 52.94.], as outlined in general procedure A provided 9 as a colorless oil (55% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.08 (s, 1H), 8.07–7.97 (m, 1H), 7.52–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.25 (m, 3H), 6.77–6.68 (m, 1H), 5.03 (s, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.13, 159.29, 155.57, 142.02, 135.92, 129.17(2C), 128.45(3C), 114.10, 104.88, 78.29, 52.26. ESI-MS m/z: 293.1 (MH+).

Methyl 2-((Benzyloxy)amino)-6-methoxynicotinate (10a)

Treatment of 8 as outlined in general procedure A provided 10a as a colorless oil (51% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.22 (s, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.45 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.29 (m, 3H), 6.16 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 5.09 (s, 2H), 3.99 (s, 3H), 3.78 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.82, 166.70, 160.47, 142.09, 136.36, 128.81 (2C), 128.42 (2C), 128.26, 101.26, 98.90, 78.39, 53.74, 51.67.

General Procedure B for the Synthesis of 6-Substituted Methyl 2-((Benzyloxy)amino)-nicotinates (10b and 10c)

Methyl 2-((benzyloxy)amino)-6-chloronicotinate (9) (1 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (1 mL). Piperidine or morphiline (4 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred and heated (80 °C, 1 h). The crude mixture was purified by silica gel chromatography to provide 6-substituted methyl 2-((benzyloxy)amino)-nicotinates (10b and 10c).

Methyl 2-((Benzyloxy)amino)-6-(piperidin-1-yl)nicotinate (10b)

Treatment of 9 with piperidine as outlined in general procedure B provided 10b as a colorless oil (88% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.12 (s, 1H), 7.85 (dd, J = 9.0, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.44 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.30 (m, 4H), 6.05 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 5.07 (s, 2H), 3.74 (d, J = 0.7 Hz, 3H), 3.39–3.66 (m, 4H), 1.67–1.65 (m, 2H), 1.63–1.61 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.99, 160.55, 159.92, 140.74, 136.79, 128.74 (2C), 128.60, 128.42, 128.33 (2C), 128.05, 97.10, 94.46, 78.11, 51.22, 45.70, 25.66, 24.74. ESI-MS m/z: 342.2 (MH+).

Methyl 2-((Benzyloxy)amino)-6-morpholinonicotinate (10c)

Treatment of 9 with morpholine as outlined in general procedure B provided 10c as a colorless oil (99% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.13 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.34–7.23 (m, 3H), 5.99 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 5.03 (s, 2H), 3.73 (s, 3H), 3.73–3.71 (m, 4H), 3.63–3.60 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.86, 160.19 (2C), 141.05, 136.70, 128.63 (2C), 128.36 (2C), 128.11, 96.84, 95.76, 78.11, 66.57 (2C), 51.36, 44.73 (2C). ESI-MS m/z: 344.2 (MH+).

General Procedure C for the Synthesis of Methyl Nicotinates (11a–c)

Methyl 3-chloro-3-oxopropanoate (12 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of methyl 2-((benzyloxy)amino)-nicotinates (10a–c) (6 mmol) and triethylamine (12 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (40 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature (1 h). The crude mixture was filtered and the filtrate was concentrated. The crude residue was purified by silica gel chromatography to provide methyl nicotinates (11a–c).

Methyl 2-(N-(Benzyloxy)-3-methoxy-3-oxopropanamido)-6-(piperidin-1-yl)nicotinate (11b)

Treatment of 10b as outlined in general procedure C provided 11b as a yellow oil (76% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.93 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 2H), 7.24–7.23 (m, 3H), 6.49 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.99 (s, 2H), 3.90 (s, 1H), 3.80 (s, 1H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.62 (s, 3H), 3.55–3.56 (m, 4H), 1.61–1.58 (m, 2H), 1.55–1.54 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 442.2 (MH+).

Methyl 2-(N-(Benzyloxy)-3-methoxy-3-oxopropanamido)-6-morpholinonicotinate (11c)

Treatment of 10c as outlined in general procedure C provided 11c as a yellow oil (79% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.04 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.32–7.28 (m, 5H), 6.52 (dd, J = 8.9, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (s, 2H), 3.85–3.83 (m, 1H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.77–3.75 (m, 4H), 3.72–3.71 (m, 1H), 3.68 (s, 3H), 3.60–3.57 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 444.2 (MH+).

General Procedure D for the Synthesis of Methyl Carboxylates (12a–c)

A solution of sodium methanolate (16 mmol, 25% in methanol) was added to a solution of methyl nicotinates (11a–c) (6 mmol) in methanol (4 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature (18 h). The reaction mixture was brought to pH 4 by the addition of aqueous HCl (2N) and stirred (0 °C, 15 min). The crude suspension was filtered, and the solid was collected to provide methyl carboxylates (12a–c).

Methyl 1-(Benzyloxy)-4-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (12a)

Treatment of 10a as outlined in general procedure C and D provided 12a as a white solid (54% yield, two steps). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.20 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.62–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.32 (m, 3H), 6.61 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (s, 2H), 4.05 (s, 3H), 4.00 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.60, 170.32, 167.69, 156.93, 149.75, 136.69, 134.30, 129.68 (2C), 128.94, 128.42 (2C), 107.37, 102.64, 96.48, 77.90, 54.52, 53.01.

Methyl 1-(Benzyloxy)-4-hydroxy-2-oxo-7-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (12b)

Treatment of 11b as outlined in general procedure D provided 12b as a white solid in 62% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 13.91 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (dd, J = 7.4, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 6.49 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 5.18 (s, 2H), 3.98 (s, 3H), 3.75–3.73 (m, 4H), 1.71–1.70 (m, 2H), 1.65–1.63 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.95, 170.00, 160.00, 157.59, 150.44, 135.06, 134.75, 129.66(2C), 128.71, 128.33(2C), 102.62, 98.44, 94.11, 77.47 (2C), 52.65, 46.08, 25.76 (2C), 24.56. ESI-MS m/z: 410.2 (MH+).

Methyl 1-(Benzyloxy)-4-hydroxy-7-morpholino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (12c)

Treatment of 11c as outlined in general procedure D provided 12c as a white solid (84% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.97 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.51 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.33 (m, 4H), 6.60 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 3.72–3.54 (m, 11H). ESI-MS m/z: 412.2 (MH+).

General Procedure E for the Synthesis of Carboxyamides (13a–c)

A solution of methyl carboxylates (12a–c) (0.3 mmol) and (2,4-difluorophenyl)methanamine (1.5 mmol) in DMF (1 mL) was heated (140 °C, 2 h) in microwave reactor. The crude mixture was purified by silica gel chromatography and recrystallized from methanol to provide carboxamides (13a–c).

1-(Benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-4-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (13a)

Treatment of 12a as outlined in general procedure E provided 13a as a white solid (45% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.24 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (dd, J = 8.7, 0.4 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.29 (m, 4H), 6.81–6.73 (m, 2H), 6.62 (dd, J = 8.7, 0.4 Hz, 1H), 5.20 (d, J = 0.6 Hz, 2H), 4.58 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.02 (d, J = 0.5 Hz, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 468.2 (MH+).

1-(Benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-4-hydroxy-2-oxo-7-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (13b)

Treatment of 12b as outlined in general procedure E provided 13b as a white solid (90% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.30 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 10.03 (s, 1H), 8.05 (dd, J = 9.1, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.58–7.56 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.33 (m, 4H), 6.85–6.76 (m, 2H), 6.54 (dd, J = 9.1, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 5.20 (s, 2H), 4.60 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.76–3.74 (m, 4H), 1.71–1.69 (m, 2H), 1.67–1.61 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 521.2 (MH+).

1-(Benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-4-hydroxy-7-morpholino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (13c)

Treatment of 12c as outlined in general procedure E provided 13c as a white solid (89% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.22 (bs, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.50–7.48 (m, 2H), 7.33–7.24 (m, 4H), 6.79–6.69 (m, 2H), 6.48 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 4.56 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 3.73–3.66 (m, 8H). ESI-MS m/z: 523.2 (MH+).

General Procedure F for the Synthesis of p-Methylbenzenesulfonates (14a–c)

Compound 4-hydroxyl analogues (13a–c) (0.5 mmol) were dissolved in CH3CN (3 mL). DIEA (2.8 mmol), CH2Cl2 (2 mL), and p-methylbenzene-1-sulfonyl chloride (1.4 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature (18 h). The mixture crude was purified by silica gel chromatography to provide p-methylbenzenesulfonates (14a–c).

1-(Benzyloxy)-3-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-7-methoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl 4-Methylbenzenesulfonate (14a)

Treatment of 13a as outlined in general procedure F provided 14a as a colorless oil (68% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.53 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 8.01 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.58–7.56 (m, 2H), 7.46–7.44 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.35 (m, 3H), 7.32 (dd, J = 8.6, 0.7 Hz, 2H), 6.83–6.74 (m, 2H), 6.64 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 4.48–4.46 (m, 2H), 4.06 (s, 3H), 2.43 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 622.1(MH+).

1-(Benzyloxy)-3-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-2-oxo-7-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl 4-Methylbenzenesulfonate (14b)

Treatment of 13b as outlined in general procedure F provided 14b as a colorless oil (53% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.83 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (dd, J = 8.8, 3.2 Hz, 3H), 7.58–7.55 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.35 (m, 4H), 7.31–7.29 (m, 2H), 6.82–6.73 (m, 2H), 6.57 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 5.22 (s, 2H), 4.44 (s, 2H), 3.76 (bs, 4H), 2.42 (s, 3H), 1.72–1.69 (m, 2H), 1.66–1.64 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 675.2 (MH+).

1-(Benzyloxy)-3-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-7-morpholino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl 4-Methylbenzenesulfonate (14c)

Treatment of 13c as outlined in general procedure F provided 14c as a colorless oil (27% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.71 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 8.19–8.18 (m, 2H), 7.94 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.36–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.36–7.28 (m, 3H), 6.82–6.74 (m, 3H), 6.55 (dd, J = 9.2, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (s, 2H), 4.43–4.41 (m, 2H), 3.78–3.73 (m, 8H), 2.42 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 677.2 (MH+).

General Procedure G for the Synthesis of 4-Substituted Amines (15a–f, 17d, and 17e)

A solution of p-methylbenzenesulfonates (14a–c and 17b) (0.2 mmol), DIPEA (2 mmol), and methyl 2-aminoacetate hydrochloride or 2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)methanamine (1 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) was stirred and heated (50 °C, 1 h). The crude mixture was purified by silica gel chromatography to provide 4-substituted amines (15a–f, 17d, and 17e).

Methyl 2-((1-(Benzyloxy)-3-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-7-methoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)acetate (15a)

Treatment of 14a with methyl 2-aminoacetate hydrochloride as outlined in general procedure G provided 15a as a white solid (91% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.20 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 10.70 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.56 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.32 (m, 4H), 6.82–6.74 (m, 2H), 6.55 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 5.20 (s, 2H), 4.61 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 4.35 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 4.02 (s, 3H), 3.76 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 539.2 (MH+).

Methyl 2-((1-(Benzyloxy)-3-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-2-oxo-7-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)acetate (15b)

Treatment of 14b with methyl 2-aminoacetate hydrochloride as outlined in general procedure G provided 15b as a white solid (80% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.99 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 10.78 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 7.58–7.55 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.31 (m, 4H), 6.81–6.72 (m, 2H), 6.40 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 5.18 (s, 2H), 4.60 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 4.32 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.71–3.69 (m, 4H), 1.71–1.67 (m, 2H), 1.64–1.59 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 592.2 (MH+).

Methyl 2-((1-(Benzyloxy)-3-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-7-morpholino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)acetate (15c)

Treatment of 14c with methyl 2-aminoacetate hydrochloride as outlined in general procedure G provided 15c as a white solid (63% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.06 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 10.73 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (dd, J = 9.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.53–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.27 (m, 3H), 6.81–6.73 (m, 3H), 6.38 (dd, J = 9.3, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 5.16 (s, 2H), 4.60 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 4.32 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.75–3.73 (m, 4H), 3.68–3.65 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 594.2 (MH+).

1-(Benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-4-((2,4-dimethoxybenzyl)amino)-7-methoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (15d)

Treatment of 14a with (2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)methanamine as outlined in general procedure G provided 15d as a white solid which was directly used in next step. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.88 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 10.77 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (dd, J = 8.9, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.61–7.59 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.24–7.21 (m, 1H), 6.81–6.73 (m, 2H), 6.47–6.42 (m, 3H), 5.24 (s, 2H), 4.67 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 4.56 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 4.02 (s, 3H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.75 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 617.2 (MH+).

1-(Benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-4-((2,4-dimethoxybenzyl)amino)-2-oxo-7-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (15e)

Treatment of 14b with (2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)methanamine as outlined in general procedure G provided 15e as a white solid (65% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.71 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 10.85 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 7.60–7.57 (m, 2H), 7.37–7.32 (m, 4H), 7.27–7.24 (m, 1H), 6.81–6.72 (m, 2H), 6.44–6.42 (m, 2H), 6.30 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 5.20 (s, 2H), 4.64 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 4.55 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.70–3.67 (m, 4H), 1.70–1.66 (m, 2H), 1.63–1.58 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 670.3 (MH+).

1-(Benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-4-((2,4-dimethoxybenzyl)amino)-7-morpholino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (15f)

Treatment of 14c with (2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)methanamine as outlined in general procedure G provided 15f as a white solid which was directly used in next step. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.73 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 10.75 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.52–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.33–7.21 (m, 5H), 6.80–6.71 (m, 4H), 6.30 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 5.16 (s, 2H), 4.63 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 4.51 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 3.73–3.71 (m, 4H), 3.65–3.63 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 672.3 (MH+).

General Procedure H for the Synthesis of Amine Analogues (16a–c, 19b–g)

The 2,4-dimethoxybenzyl protected compounds (15d–f and 18a–h) (0.25 mmol) were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (2 mL). TFA (2 mL) was added at room temperature. The reaction mixture was concentrated. The crude residue was purified by silica gel chromatography to provide amine analogues (16a–c and 19b–g).

4-Amino-1-(benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-7-methoxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (16a)

Treatment of 15d as outlined in general procedure H provided 16a as a colorless oil (72% yield, two steps (general procedures G and H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.60 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (dd, J = 8.7, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (dd, J = 7.3, 2.2 Hz, 2H), 7.36–7.32 (m, 4H), 6.81–6.74 (m, 2H), 6.58 (dd, J = 8.8, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (s, 2H), 4.58 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 4.03 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 467.2 (MH+).

4-Amino-1-(benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-2-oxo-7-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (16b)

Treatment of 15e as outlined in general procedure H provided 16b as a colorless oil (46% yield, two steps (general procedures G and H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.62 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.54–7.52 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.26 (m, 4H), 6.78–6.69 (m, 2H), 6.44 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 4.54 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.70–3.65 (m, 4H), 1.66–1.63 (m, 2H), 1.61–1.57 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 520.2 (MH+).

4-Amino-1-(benzyloxy)-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-7-morpholino-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (16c)

Treatment of 15f as outlined in general procedure H provided 16c as a colorless oil (32% yield, two steps (general procedures G and H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.61 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.49 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.28 (m, 3H), 6.83–6.71 (m, 3H), 6.48 (dd, J = 9.1, 0.7 Hz, 1H),5.18 (s, 2H), 4.58 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.81–3.75 (m, 4H), 3.69–3.67 (m, 4H). ESI-MS m/z: 522.2 (MH+).

Methyl 2-((1-(Benzyloxy)-6-bromo-3-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)acetate (17d)

Treatment of 1-(benzyloxy)-6-bromo-3-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate 17b(31) with methyl glycinate as outlined in general procedure G provided 17d as a white solid (74% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.05 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 10.61 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.39–7.22 (m, 4H), 7.17 (dd, J = 8.9, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 6.85–6.63 (m, 2H), 6.47–6.34 (m, 2H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 4.64 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 4.52 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 3.73 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 587.1, 589.1 (MH+).

1-(Benzyloxy)-6-bromo-N-(2,4-difluorobenzyl)-4-((2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide (17e)

Treatment of 1-(benzyloxy)-6-bromo-3-((2,4-difluorobenzyl)carbamoyl)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate 17b(31) with 2-aminoethan-1-ol as outlined in general procedure G provided 17e as a white solid (93% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.65 (bs, 1H), 10.65 (bs, 1H), 8.64 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 6.79–6.73 (m, 2H), 5.15 (s, 2H), 4.55 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.88–3.86 (m, 2H), 3.78–3.75 (m, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 559.1, 561.1 (MH+).

General Procedure J for the Synthesis of 6-Alkylated Analogues (18a, 18b, 18d, 18i, and 18j) Using Sonogashira Reaction