Abstract

A series of benzenesulfonamides bearing selenourea moieties was obtained considering the ureido-sulfonamide SLC-0111, in Phase I clinical trials as antitumor agent, as a lead molecule. All compounds showed interesting inhibition potencies against the physiologically relevant human (h) carbonic anhydrase (hCAs, EC 4.2.1.1) isoforms I, II, IV, and IX. The most flexible analogues in the series 14–19 showed low nanomolar inhibition constants against hCA I, II, and IX. We assessed selected compounds on the in vitro antioxidant properties and binding modes and evaluated ex vivo human prostate (PC3), breast (MDA-MB-231), and colon-rectal (HT-29) cancer cell lines both in normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

Keywords: Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs), metalloenzymes, glutathione peroxidase, selenoureido, bioisosterism

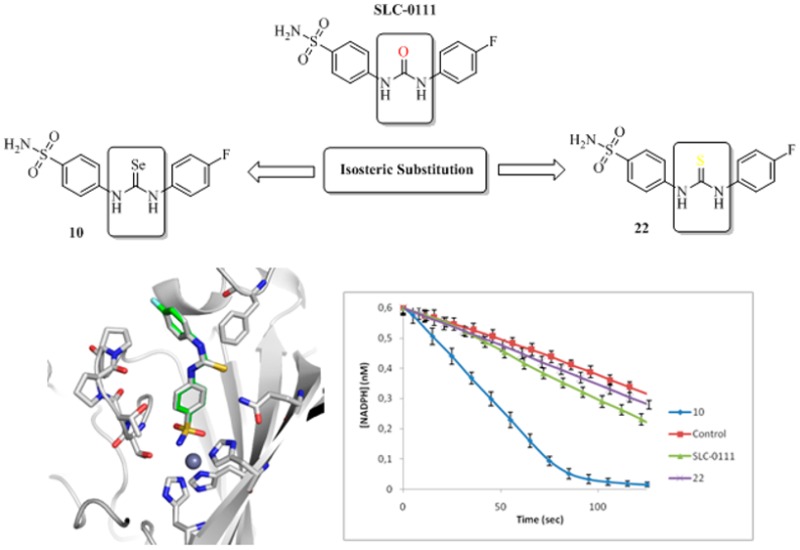

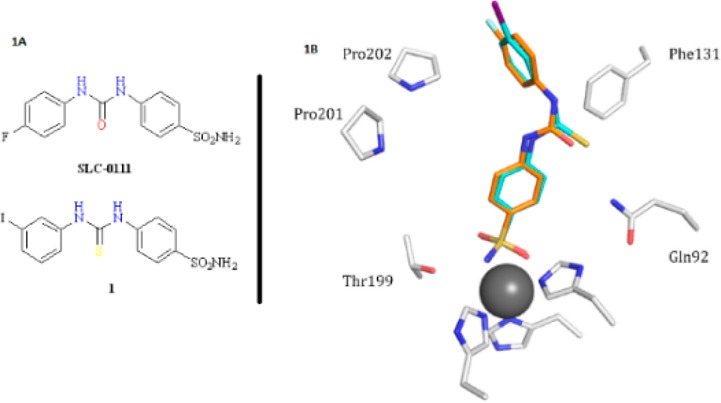

Isosteric replacement is a commonly used approach in medicinal chemistry. It consists in the introduction, within selected lead compounds, of structural modifications (named bioisosteric groups or elements) able to retain the desired biological activity.1,2 Such an experimental approach can be highly reliable when optimizing pharmacological activities, pharmacokinetics and/or selectivity enhancement for a specific biological target.1,2 We recently applied the isosteric replacement to the compound in Figure 1A (SLC-0111),3 which successfully ended Phase I clinical programs for the treatment of patients with advanced hypoxic tumors overexpressing the isoform IX of the human (h) metalloenzyme carbonic anhydrases (CAs, EC 4.2.1.1).4−7

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of the ureido benzenesulfonamide SLC-0111 and its thioureido analogue 1. (B) hCA II–1 complex (cyan) superposed with the hCA II–SLC-0111 complex (orange). Active site residues involved in the binding of inhibitors are labeled, and the zinc ion is shown as a gray sphere.3

These enzymes are highly efficient in reversibly catalyzing the hydration of carbon dioxide into carbonic acid. Such a chemical transformation is deeply involved in various cellular patho/physiological events, which among others include cancerogenesis and progression.8,9

Divalent isosteric substitution of the oxygen in SLC-0111 with the sulfur atom instead (compound 1 in Figure 1A) did not significantly affect the in vitro inhibition profile on hCAs I, II, IX, and XII.3 Rationalization of these data was offered by the superposition of the X-ray cocrystallographic adducts of 1 and SLC-0111 with hCA II (Figure 1B).3 Only a slight distortion of the two structures was observed, with the closer orientation of the C=S moiety in 1 toward the Phe131 residue when compared to the C=O in SLC-0111. The meta-iodophenyl tail did not show any difference when compared to the parent SLC-0111para-fluorophenyl tail.3

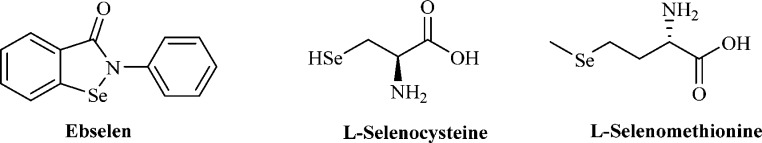

The insertion of selenium instead of oxygen or sulfur is an isosteric replacement widely employed within the medicinal chemistry field.1 Since selenium is an essential element for the human physiology,10,11 all the isosteric replacements based on this element are particularly valuable or with a high potential for obtaining interesting biological effects.1 Various diseases in which oxidative stress is a major factor are strictly associated with selenium deficiency or are endemic in areas with low concentrations of Se.10−12 Tremendous efforts have been directed toward the synthesis of stable organoselenium compounds such as Ebselen, l-Se-Cys, or l-Se-Met (Figure 2) that may serve as antioxidant adjuvants in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, autoimmune diseases, myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, and tumors as the most important.10,12

Figure 2.

Selenium containing small molecules currently used in clinic.10

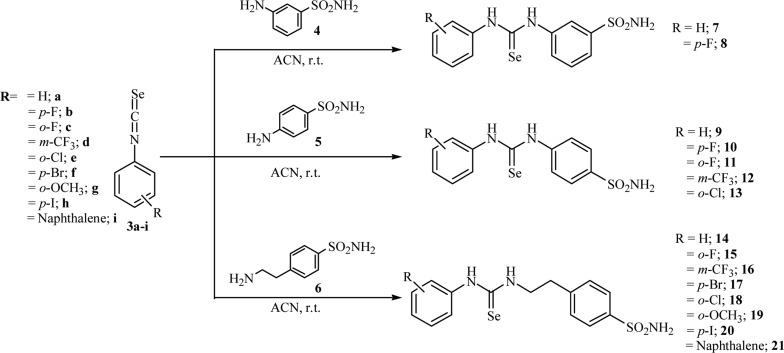

All the pathologies above listed are commonly characterized by an overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which rapidly determine a work overload/depletion of the human antioxidant enzymatic pool, which is mainly constituted by the superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione reductase (GR), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and glutathione (GSH)10,13 An excess of unbuffered ROS determines, at the molecular level, irreversible damages to cellular structures such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids and thus fosters the disease outcome.13−15 In this context, we considered of particular interest the synthesis of a series of SLC-0111 congeners according to the divalent isosteric replacement approach, by means of introduction within the ureido moiety of the ROS scavenger element selenium. The selenoureido containing compounds 7–21 were obtained by standard coupling reactions of the aromatic isoselenocyanates 3a–i with commercially available benzenesulfonamides 4–6 in acetonitrile (ACN) as solvent (Scheme 1).6

Scheme 1. General Synthetic Procedure for Compounds 7–21.

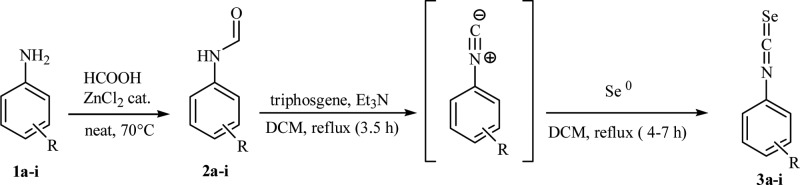

The proper isoselenocyanates 3a–i were obtained in a two-step synthetic procedure (Scheme 2) which involved: (i) N-formylation in high yields of the commercially available aromatic amines 1a–i using catalytic zinc(II) chloride and formic acid under neat conditions16 and (ii) conversion of the formylanilines 2a–i to the corresponding isoselenocyanates 3a–i using the modified Barton’s procedure.17

Scheme 2. General Synthetic Scheme of Compounds 3a–i.

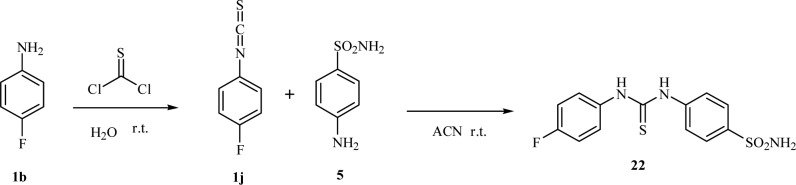

It is noteworthy that the dehydration of formylanilines 2a–i was successfully conducted by the use of the safer and handy solid triphosgene,18,19 and the in situ obtained isocyanides (not isolated) were treated with an excess of selenium (0) powder to afford the desired isoselenocyanates 3a–i.20 In order to asses a proper structure–activity relationship (SAR), the synthesis of the SLC-0111 thioureido analogue 22 was also carried out according to standard procedures (Scheme 3).3

Scheme 3. Synthesis of the Thioureido Derivative 22(3).

All synthesized compounds, 7–22, were tested in vitro for their inhibitory properties against the physiological relevant hCA isoforms (I, II, IV, and IX)3,7−9 by means of the stopped-flow carbon dioxide hydration assay,21 and their activities were compared to the standard carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (CAI) acetazolamide (AAZ) (Table 1).

Table 1. hCA I, II, IV, and IX Inhibition Data of Compounds 7-22 and SLC-0111 by a Stopped-Flow CO2 Hydrase Assay21.

|

KI (nM)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | hCA I | hCA II | hCA IV | hCA IXb |

| 7 | 483.8 | 343.2 | 908.7 | 329.7 |

| 8 | 435.3 | 388.9 | 765.9 | 97.8 |

| 9 | 132.5 | 54.3 | 8627 | 78.9 |

| 10 | 152.3 | 66.3 | 7557 | 63.0 |

| 11 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 902.1 | 5.8 |

| 12 | 32.7 | 6.1 | 734.4 | 15.9 |

| 13 | 7.9 | 4.0 | 268.8 | 3.9 |

| 14 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 1782 | 5.3 |

| 15 | 44.1 | 7.9 | 898.2 | 8.7 |

| 16 | 8.5 | 4.4 | 928.9 | 5.8 |

| 17 | 51.7 | 1.8 | 1409 | 4.8 |

| 18 | 8.3 | 3.5 | 731.2 | 4.8 |

| 19 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 765.9 | 3.1 |

| 20 | 267.4 | 57.6 | 6760 | 54.9 |

| 21 | 501.7 | 91.2 | 5423 | 93.1 |

| 22 | 35.0 | 14.2 | 4797 | 32.1 |

| SLC-0111 | 5080 | 960.0 | 286.0 | 45.0 |

| AAZ | 250 | 12.1 | 74 | 25.8 |

Means from three different assays. Errors were within ±5–10% of the reported values (data not shown).

Catalytic domain.

The following SARs for the hCA isoforms considered are reported: (i) The ubiquitous cytosolic hCA I was inhibited by all compounds with KIs spanning between 5.9 and 501.7 nM. Within the series reported, the compounds bearing the sulfonamide moiety at position 3 of the ring, compounds 7 and 8, or the bulky naphthyl tail moiety 21, resulted as the least active with KI values, respectively, 1.9-, 1.7-, and 2.0-fold higher when compared to the standard CAI acetazolamide (AAZ) (Table 1). Relocation of the primary sulfonamide moiety in compound 7 from the meta to the para position, to afford 9, resulted in a significant enhancement of the inhibitory potency (KIs of 483.8 and 132.5 nM, respectively). The introduction in 9 of the para-fluoro moiety, compound 10, slightly enhanced the KI value 1.15-fold. It is noteworthy that the inhibition potency was greatly improved when the fluoro was introduced in the ortho position (compound 11, KI of 5.9 nM). The nature of the halide did not affect the inhibition potency against the hCA I as the introduction ortho of the chloro atom instead of the fluoro, to afford 13, only slightly increased the KI value to 7.9 nM. Conversely, the introduction of the trifluoromethyl group in the meta position spoiled the inhibition value to 32.7 nM. Among the ethylamino benzenesulfonamides 14–21, the phenyl and the ortho-methoxy-substituted derivatives 14 and 19 resulted in the most active of the series, with KIs of 6.7 and 6.0 nM, respectively. Interestingly, the meta-trifluoromethyl and the ortho-chloro substituted derivatives 16 and 18 slightly differed for their inhibition potencies (KIs of 8.5 and 8.3 nM), respectively. Among the phenyl halide derivatives, the ortho-fluoro 15 and the para-bromo 17 resulted in similar potencies, inhibiting the hCA I with KIs of 44.1 and 51.7 nM, respectively. Substitution of the bromine with the iodine, as in compound 20, was detrimental for the inhibition activity (KI of 267.4 nM). The bioisosteric substitution in SLC-0111 of the oxygen within the ureido moiety with a sulfur or selenium atom instead (compounds 22 and 10, respectively) resulted in an increase of the inhibition potency against the hCA I isoform of 145.1- and 33.4-fold, respectively (Table 1).

(ii) The cytosolic and highly efficient hCA II isoform was effectively inhibited by all compounds synthesized (KI comprised between 3.5 and 388.9 nM), and in analogy to the hCA I, the metanilamide derivatives 7 and 8 were the least potent (KI of 343.2 and 388.9 nM, respectively). Among the sulfanilamide series, the introduction of the para-fluoro moiety within the simple phenyl ring, conversion of 9 to 10, slightly spoiled the inhibition potency (KI of 54.3 and 66.3 nM, respectively). Placement of the fluoro atom in the ortho position, compound 11, resulted in a 10.5-fold increase of the inhibition potency, which was retained when the meta-trifluoromethyl group was introduced instead (compound 12, KI of 6.1 nM) or even reinforced when a ortho-chloro moiety was placed (compound 13, KI of 4.0 nM). Among the ethylaminobenzenesulfonamide series 14–21, all compounds were quite effective in inhibiting the hCA II isoform (KIs spanning between 1.8 and 7.9 nM), with the only exceptions represented by the bulky para-iodo 20 and the naphthyl derivative 21 (KI of 57.6 and 91.2 nM, respectively). As for the hCA II, the bioisosteric substitution of the oxygen atom within the ureido group in SLC-0111 (KI 960 nM) resulted in enhancement of the inhibition potency. As reported in Table 1, KIs of 66.3 and 14.2 nM were obtained when the selenium, compound 10, or the sulfur, compound 22, were introduced.

(iii) The membrane bound hCA IV was the least inhibited among the enzymatic isoforms herein considered and showed KIs spanning between 8627 and 268.8 nM. The introduction in 7 of the fluoro atom in para position, to afford 8, resulted in a 1.2-fold enhancement of the inhibition potency. In analogy, a 1.1-fold inhibition potency increase was reported when the para-fluoro substitution was operated in 9 to afford 10 (KI of 8627 and 7557 nM respectively), and it was further improved when a meta-trifluoromethyl (KI of 734.4 nM) or a ortho-chloro moiety (KI of 268.8 nM) was introduced. Among the ethylaminobenzenesulfonamide series the introduction within the phenyl tail of 14 in ortho position either of a fluoro 15, chloro 18, methoxy 19, or a meta-trifluoromethyl moiety, as in 16, resulted in a significant enhancement of the inhibition potency with KI of 1782, 898.2, 731.2, 765.9, and 928.9 nM, respectively (Table 1). The introduction in 14 of the para-bromo moiety determined only a slight reduction of the inhibition activity against the hCA IV. The bulky para-iodo 20 and naphthyl 21 were the least effective in the series (KI of 6760 and 5423 nM, respectively). The effects of the divalent isosteric substitution in SLC-0111 were detrimental for the inhibition properties against the hCA IV isoform. As reported in Table 1, the parent SLC-0111 showed a KI value of 286 nM, the introduction of the sulfur and the selenium atom within the ureido moiety enhanced the KI value 16.8- and 26.4-fold, respectively.

(iv) The transmembrane and tumor associated hCA IX were effectively inhibited by the compounds herein reported and showed KI values comprised between 3.1 and 329.7 nM. In particular, the introduction of the para-fluoro moiety in 7, to afford 8, resulted in a 3.4-fold decrease of the inhibition value. A slight lower potency increase (1.3-fold) was observed when the para-fluoro moiety was introduced within the sulfanilamide series (conversion of 9 to 10). In analogy to the other enzymes herein considered, the inhibition data showed strictly related to the fluoro regioisomerism. Kinetic data in Table 1 account for a 10.9-fold potency increase when the fluoro moiety was shifted from the para to the ortho position (conversion of 10 to 11). Interestingly, the replacement of the fluoro atom in 11 with the chloro instead, to afford 13, resulted in an increase of the inhibition potency (KIs of 5.8 and 3.9 nM, respectively). The introduction of the meta-trifluoromethyl moiety within the simple phenyl tail on compound 9 to afford 12 was beneficial for the inhibition potency, which showed a 5.0-fold increase (KI of 78.9 and 15.9 nM for 9 and 12, respectively). With the exception of the bulky para-iodo 20 and naphthyl derivative 21 (KI of 54.9 and 93.1 nM, respectively), all compounds within the ethylbenzenesulfonamide series were quite effective in inhibiting the hCA IX and showed KIs spanning between 3.1 and 8.7 nM, thus far more active when compared to the standard CAI AAZ (KI of 25.8 nM). In particular, the introduction in 14 of the ortho-fluoro moiety to afford 15, slightly spoiled the inhibition potency (KI of 5.3 and 8.7 nM, respectively). Conversely the introduction within the phenyl tail in 14 of a meta-trifluoromethyl 16, or para-bromo 17, ortho-chloro 18, and ortho-methoxy 19 moiety, clearly resulted in enhancement of the inhibition potency (KI of 5.8, 4.8, 4.8, and 3.1 nM respectively). SAR relative to the isosteric substitution of the oxygen within the SLC-0111 ureido moiety accounted for an increase of the inhibition potency when the sulfur was introduced (compound 22, KI of 32.1 nM). Conversely, the KI value was 1.4-fold decreased when the selenium was introduced instead (compound 10, KI of 63 nM).

In general, the divalent bioisosteric replacement of the ureido oxygen on SLC-0111 with a sulfur or selenium, compounds 22 and 10, respectively, determined powerful enhancements of the inhibition potencies against the hCA I and II isoforms (Table 1). Any modification at the ureido moiety resulted in a suppression of the inhibition activity against the membrane associated hCA IV (KI of 4797 and 7557 for 22 and 10, respectively). Interestingly, the sulfur derivative 22 resulted in only a slight increase of the inhibition potency against hCA IX (KI of 45.0 and 32.1 nM for SLC-0111 and 22, respectively). Conversely, the introduction of the selenium, as in 10, was detrimental for the activity (KI of 63.0 nM). Although the inhibition potency of the selenium derivative 10 was only 1.4-fold less potent when compared to the parent SLC-0111, it is worth mentioning that the selectivity ratio hCA II/hCA IX of this compound was heavily spoiled (21.3 for SLC-0111 and 1.1 for 10).

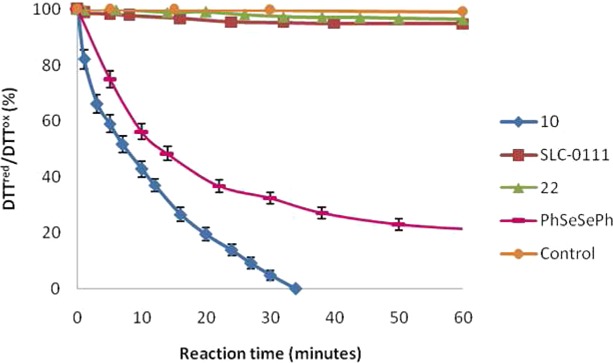

The antioxidant activity of the selenoureido congener of SLC-0111 (compound 10) was evaluated according to literature procedures in catalyzing the reaction between hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and two different thiols such as dithiothreitol (DTT)22−25 and glutathione (GSH).26,27 A preliminary investigation of the GPx-like activity of compound 10 was carried out following the oxidation of DTT in CD3OD by means of 1H NMR. A control experiment was performed in the absence of catalyst. The catalytic activity of (PhSe)2 against DTTred under these conditions was also determined, to compare the activity of the title compound with commonly used standard materials for the GPx assays.28−30 As depicted in Figure 3, when the reaction was performed in the absence of catalyst, 98% of DTTred remained unreacted after 60 min. Conversely, DTT oxidation was complete within 35 min when 10% of the substituted selenourea 10 was added. Under these conditions, the time required to halve the initial concentration of DTTred (T50) was 8 min. Interestingly, according to this test, 10 proved to behave as a better catalyst than (PhSe)2 in that it exhibited a longer reaction time and higher T50 values. Compounds SLC-0111 and 22 did not catalyze the DTT oxidation under the studied conditions, being the kinetic profile comparable with that of the control experiment.

Figure 3.

Oxidation of DTTred with H2O2 in the presence of compounds 10, SLC-0111, and 22. Reaction conditions: [DTTred]0 = 0.14 mM, [H2O2]0 = 0.14 mM, [catalyst] = 0.014 mM, CD3OD = 1.1 mL. 1H NMR spectra were measured at variable reaction time at 25 °C. The relative populations of DTTred and DTTox were determined by integration of the 1H NMR signals. In the control experiment the reaction was run with no catalyst. Reported are the mean ± SD values of three separate experiments.

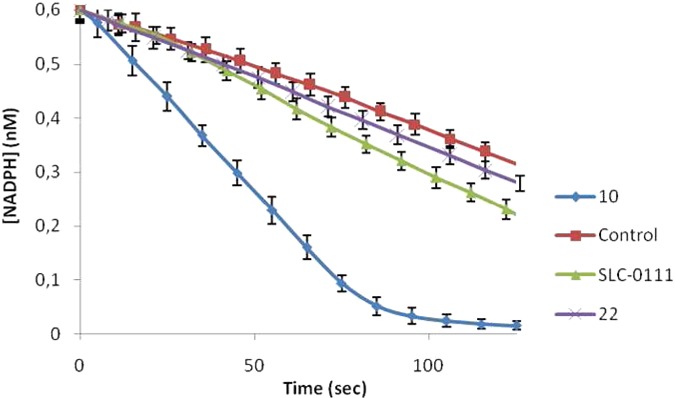

The GPx-like properties of 10 were further confirmed by using the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-coupled assay. In this experiment, GSH was used as a substrate and H2O2 as an oxidant in the presence of NADPH and glutathione reductase (GR).26,27 The reaction was carried out in H2O, and its progress was monitored by UV spectroscopy, measuring the absorbance decreasing at 340 nm due to the consumption of NADPH (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

NADPH-coupled GPx assay for compounds 10, SLC-0111, and 22. Reaction conditions: [NADPH]0 = 0.6 mM, [GSH]0 = 2.0 mM, [H2O2]0 = 5 mM, [GR] = 8 units/mL, [catalyst] = 0.2 mM in pH 7.4 phosphate buffer at room temperature. Reported are the mean ± SD values of three separate experiments.

As above-reported, the NADPH was completely consumed within 100 s in the presence of the selenium containing compound 10. Conversely, the NADPH consumption rate was only slightly higher with respect to the control experiment (no catalyst used) when the sulfur- and oxygen-containing analogues 22 and SLC-0111 were used instead.

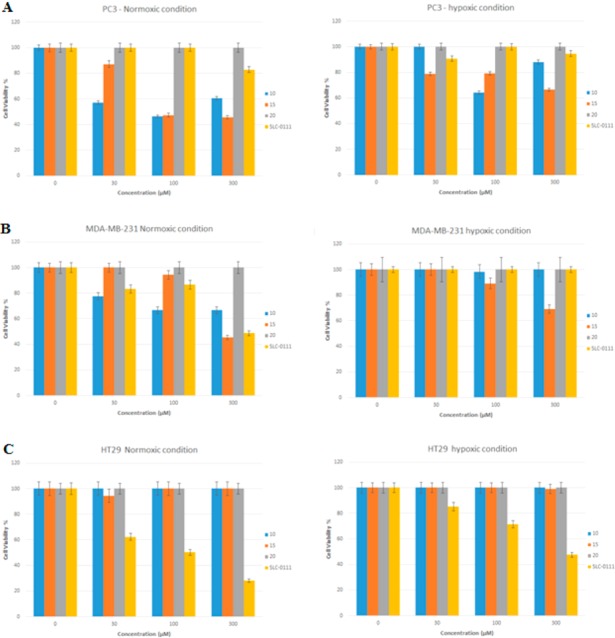

The water-soluble selenoureido containing compounds 10, 15, and 20 were evaluated for their viability effects on human prostate (PC3), breast (MDA-MB-231), and colon cancer (HT-29) cells lines at 30, 100, and 300 μM concentration, incubated for 48 h both under normoxic and hypoxic conditions and using the CA inhibitor SLC-0111 as a reference compound (Figure 4).

In PC3 cells, the selenoureido derivative of SLC-0111 (compounds 10) and the its longer ortho-fluoro derivative 15 significantly reduced cell viability in normoxia (20% oxygen), whereas their effects resulted lower when the experiments were carried out under hypoxic conditions (0.1% oxygen). Compound 20 was ineffective in all sets of experiments, whereas the reference ureido derivative SLC-0111 induced modest mortality and only at the highest concentration (300 μM) in normoxia (Figure 5A). Interestingly, in MDA-MB-231 cells, compound 10 was effective in normoxia at 30 μM and with a profile comparable to the reference SLC-0111. The elongated derivative 15 was successful in reducing cell viability in both conditions of oxygenation, but only at the highest concentration (300 μM). Finally compound 20 was ineffective on the breast cancer cell lines (Figure 5B). As for colon cancer HT-29 cells, all compounds considered (10, 15, and 20) were ineffective in inducing mortality, whereas the reference compounds SLC-0111 strongly reduced cell viability at all concentrations in normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

(A) PC3, (B) MDA-MB-231, and (C) HT-29 were plated at 1 × 104/well. Incubation was allowed for 48 h in normoxic (20% O2) and hypoxic conditions (0.1% O2). Compounds 10, 15, and 20 in comparison with SLC-0111 were tested in the 30–300 μM concentration range. Control condition was arbitrarily set as 100%, and values are expressed as the mean ± SEM of three experiments.

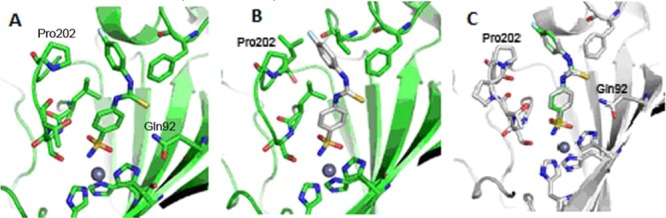

The binding modes of both selenium and sulfur analogues of SLC-0111 (compound 10 and 22, respectively) were determined by means of their X-ray cocrystallographic adducts with the hCA II (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

(A) Active site region of the hCA II–10 complex (PDB 5WEX); (B) hCA II–22 complex (PDB code: 5ULN); (C) superposition of the hCA II–10 and 22.

The difference (Fo–Fc) electron density maps of the hCA II–10 complex revealed a well ordered structure of the benzenesulfonamide section, which became weaker in electron density for the selenoureido and para-fluorobenzene moieties. Instead, the hCA II–22 complex showed clear electron density all through the molecule, thus suggesting a better ordered structure within the enzymatic cleft (Figures S1 and S2, respectively, in the Supporting Information). In both cases, 10 and 22 showed almost identical allocations within the enzyme cavity, with average distances between the two structures (RMSD) of just 0.12 Å across the whole protein (Figure 6). The compounds were buried within the enzyme active site, being coordinated to the Zn(II) ion through the sulfonamide group and orientated toward the hydrophobic half of the pocket. The selenium and sulfur atoms are within 3 Å of the Gln92 side chain and can hydrogen bond to the protein. The 4-fluorophenyl tail of 10 and 22 closely overlays and extends further into the hydrophobic side of the catalytic cleft, with the fluorine closest to Pro202 (within 3.5 Å).

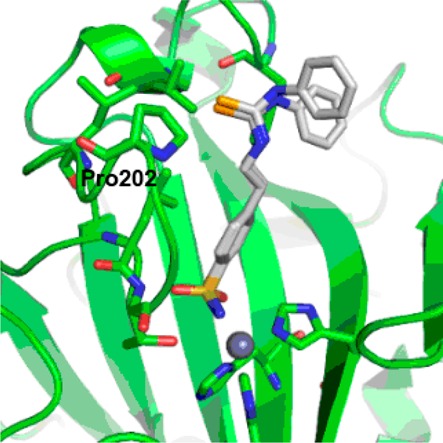

We also determined the binding mode of the longer selenoureido derivative 14 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Active site region of the hCA II–14 complex (PDB code: 5UMC).

The difference (Fo–Fc) electron density maps (Supporting Information, Figure S3) showed that 14 is buried within the enzyme cavity, toward the hydrophobic region of the cleft, where it establishes multiple van der Waals interaction with Phe131, Val135, Leu198, Leu204, and Pro202. The sulfonamide moiety is tightly coordinated to the Zn(II) ion by means of the canonical interactions of all CAs–sulfonamide compounds.3,31 Conversely, to the sulfonamide containing head section, the tail fragment of 14 was somewhat disordered. The N-phenyl moiety was modeled with two different conformations in this structure due to the diffuse electron density present in this region (Figure 7).

In conclusion, we report for the first time the synthesis of a series of derivatives, 7–21, a rarely investigated chemotype in the CA field, as congeners of the CAI inhibitor SLC-0111. All compounds were obtained according to the bioisosteric replacement approach, and its effects on the inhibition potency were examined. The antioxidant activity of the selenium containing CAI 10 was assessed by means of the DTT and GSH oxidation tests. Furthermore, the binding modes of compounds 10, 14, and 22 within the hCA II were determined. Finally, we reported a preliminary cytotoxic assay of selected compounds on prostate, breast, and colon cell lines. The obtained results suggested that multiple mechanisms of action, not yet identified, may take place and are responsible for exerting the compounds’ cytotoxic effects. In the whole, this study clearly opens new perspectives within the CA-dependent diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank OpenEye Scientific Software for a license to use Afitt, the CSIRO Collaborative Crystallization Centre (www.csiro.au/c3) for crystallization, and the Australian Synchrotron and the beamline scientists at the MX-1 and MX-2 beamlines for their support in data collection.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- CAI(s)

carbonic anhydrase inhibitor(s)

- AAZ

acetazolamide

- (h)CA

(human) carbonic anhydrase

- KI

inhibition constant

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- GSH

glutathione

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00280.

Synthetic procedures, characterization of compounds, in vitro kinetic procedure, antioxidant activity procedure, cells viability procedure, X-ray statistics, and difference electron density map of compounds 10, 22, and 14 with hCA II (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Patani A. G.; LaVoie E. J. Bioisosterism: a rational approach in drug design. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 3147–3176. 10.1021/cr950066q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima L. M.; Barreiro E. J. Bioisosterism: a useful strategy for molecular modification and drug design. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 23–49. 10.2174/0929867053363540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomelino C. L.; Mahon B. P.; McKenna R.; Carta F.; Supuran C. T. Kinetic and X-ray crystallographic investigations on carbonic anhydrase isoforms I, II, IX and XII of a thioureido analog of SLC-0111. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 5, 976–981. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safety Study of SLC-0111 in Subjects With Advanced Solid Tumours. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02215850.

- Lou Y.; McDonald P. C.; Oloumi A.; Chia S.; Ostlund C.; Ahmadi A.; Kyle A.; Auf dem Keller U.; Leung S.; Huntsman D.; Clarke B.; Sutherland B. W.; Waterhouse D.; Bally M.; Roskelley C.; Overall C. M.; Minchinton A.; Pacchiano F.; Carta F.; Scozzafava A.; Touisni N.; Winum J. Y.; Supuran C. T.; Dedhar S. Targeting tumor hypoxia: suppression of breast tumor growth and metastasis by novel carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2011, 9, 3364–3376. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacchiano F.; Carta F.; McDonald P. C.; Lou Y.; Vullo D.; Scozzafava A.; Dedhar S.; Supuran C. T. Ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides potently inhibit carbonic an-hydrase IX and show antimetastatic activity in a model of breast cancer metastasis. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1896–1902. 10.1021/jm101541x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacchiano F.; Aggarwal M.; Avvaru B. S.; Robbins A. H.; Scozzafava A.; McKenna R.; Supuran C. T. Selective hydro-phobic pocket binding observed within the carbonic anhydrase II active site accommodate different 4-substituted-ureido-benzenesulfonamides and correlate to inhibitor potency. Chem. Commun. 2010, 44, 8371–8373. 10.1039/c0cc02707c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supuran C. T. Carbonic anhydrases: novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 2, 168–181. 10.1038/nrd2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supuran C. T. Structure and function of carbonic anhydrases. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 2023–2032. 10.1042/BCJ20160115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugesh G.; du Mont W.-W.; Sies H. Chemistry of biologically important synthetic organoselenium compounds. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2125–2179. 10.1021/cr000426w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S.; Manna D.; Mugesh G. Selenium-mediated dehalogenation of halogenated nucleosides and its relevance to the DNA repair pathway. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9298–9302. 10.1002/anie.201503598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapiero H.; Townsend D. M.; Tew K. D. The antioxidant role of selenium and seleno-compounds. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2003, 57, 134–144. 10.1016/S0753-3322(03)00035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen C. E.; Carroll K. S. Cysteine-mediated redox signaling: chemistry, biology, and tools for discovery. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 4633–4679. 10.1021/cr300163e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya A.; Das I.; Chandhok D.; Saha T. Redox regulation in cancer: a double-edged sword with therapeutic potential. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2010, 3, 23–34. 10.4161/oxim.3.1.10095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmaraja A. T. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in therapeutics and drug resistance in cancer and bacteria. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 3221. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A. S.; Kumar A. R.; Sathaiah G.; Luke P. V.; Madabhushi S.; Rao P. S. Facile N-formylation of amines using Lewis acids as novel catalysts. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 7099–7101. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton D. H. R.; Parekh S. I.; Tajbakhsh M.; Theodorakis E. A.; Tse C.-L. A convenient and high yielding procedure for the preparation of isoselenocyanates. Synthesis and reactivity of O-alkylselenocarbamates. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 639–654. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)80783-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotarca L.; Eckert H.. Phosgenathion-A Handbook; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cotarca L.; Delogu P.; Nardelli A.; Sunjic V. Bis(trichloromethyl) carbonate in organic synthesis. Synthesis 1996, 5, 553–576. 10.1055/s-1996-4273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Bolanos J. G.; Lopez O.; Ulgar V.; Maya I.; Fuentes J. Synthesis of O-unprotected glycosyl selenoureas. A new access to bicyclic sugar isoureas. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 4081–4084. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.03.143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifah R. G. The carbon dioxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase. I. Stop-flow kinetic studies on the native human isoenzymes B and C. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 2561–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zade S. S.; Panda S.; Tripathi S. K.; Singh H.-B.; Wolmershäuser G. Convenient synthesis, characterization and GPx-like catalytic activity of novel ebselen derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 2004, 3857–3864. 10.1002/ejoc.200400326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engman L.; Stern D.; Cotgreave I. A.; Andersson C. M. Thiol peroxidase activity of diary1 ditellurides as determined by a ’H NMR method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 9737–9743. 10.1021/ja00051a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tidei C.; Piroddi M.; Galli F.; Santi C. Oxidation of thiols promoted by PhSeZnCl. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 232–234. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaoka M.; Kumakura F. Applications of water-soluble selenides and selenoxides to protein chemistry. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2008, 183, 1009–1017. 10.1080/10426500801901038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumakura F.; Mishra B.; Priyadarsini K. I.; Iwaoka M. A water-soluble cyclic selenide with enhanced glutathione peroxidase-like catalytic activities. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 3, 440–445. 10.1002/ejoc.200901114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual P.; Martinez-Lara E.; Bàrcena J. A.; Lòpez-Barca J.; Toribio F. Direct assay of glutathione peroxidase activity using high-performance capillary electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr., Biomed. Appl. 1992, 581, 49–56. 10.1016/0378-4347(92)80446-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim M.; Muhammad N.; Naeem M.; Deobald A. M.; Kamdem J. P.; Rocha J. B. T. In vitro evaluation of glutathione peroxidase (GPx)-like activity and antioxidant properties of an organoselenium compound. Toxicol. In Vitro 2015, 29, 947–952. 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaoka M.; Tomoda S. A model study on the effect of an amino group on the antioxidant activity of glutathione peroxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 2557–2561. 10.1021/ja00085a040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S.; Kumakura F.; Komatsu I.; Arai K.; Onuma Y.; Hojo H.; Singh B. G.; Priyadarsini K. I.; Iwaoka M. Antioxidative glutathione peroxidase activity of selenoglutathione. Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 2173–2176. 10.1002/ange.201006939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alterio V.; Di Fiore A.; D’Ambrosio K.; Supuran C. T.; De Simone G. Multiple binding modes of inhibitors to carbonic anhydrases: how to design specific drugs targeting 15 different isoforms?. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4421–4468. 10.1021/cr200176r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.