Abstract

Objective:

To establish a system for patient dosimetry audit and setting of local diagnostic reference levels (LDRLs) for nuclear medicine (NM) CT.

Methods:

Computed radiological information system (CRIS) data were matched with NM paper records, which provided the body region and dose mode for NMCT carried out at a large UK hospital. It was necessary to divide data in terms of the NM examination type, body region and dose mode. The mean and standard deviation dose–length products (DLPs) for common NMCT examinations were then calculated and compared with the proposed National Diagnostic Reference Levels (NDRLs). Only procedures which have 10 or more patients will be used to suggest LDRLs.

Results:

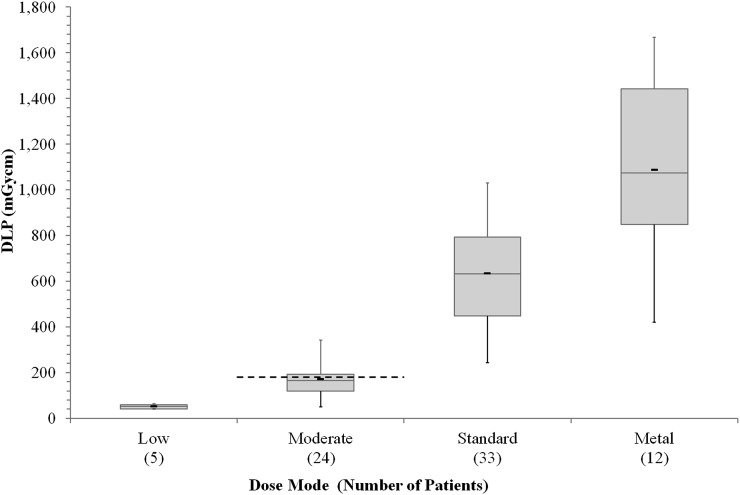

For most examinations, the mean DLPs do not exceed the proposed NDRLs. The bone single-photon emission CT/CT lumbar spine data clearly show the need to divide data according to the purpose of the scan (dose mode), with mean (±standard error) DLPs ranging from 51 ± 5 mGy cm (low dose) to 1086 ± 124 mGy cm (metal dose).

Conclusion:

A system for NMCT patient dose audit has been developed, but there are non-trivial challenges which make the process labour intensive. These include limited information provided by CRIS downloads, dependence on paper records and limited number of examinations available owing to the need to subdivide data.

Advances in knowledge:

This article demonstrates that a system can be developed for NMCT patient dose audit, but also highlights the challenges associated with such audit, which may not be encountered with more routine audit of radiology CT.

INTRODUCTION

Diagnostic reference levels (DRLs) provide a useful tool for monitoring patient exposure to ionizing radiation for imaging purposes. Providing a guide to “good and normal practice”,1 they can be used to investigate consistently high doses, as well as provide a baseline for dose optimization. This is reinforced with a legislative requirement to establish local diagnostic reference levels (LDRLs) in the UK2 and at the European level.3

The use of DRLs is well established in diagnostic radiology, with UK national guidance on their use and implementation having been available for some time.1 UK National Diagnostic Reference Levels (NDRLs) are based on third quartiles of dosimetry data provided from hospitals throughout the UK and are regularly reviewed for planar X-ray, fluoroscopic imaging4 and CT;5 Public Health England formally adopt the NDRLs.6 Guidance for setting of LDRLs is based on mean dosimetry data for patients in the range 50–90 kg, with a mean weight in the range 65–75 kg.1

At a local level, many medical physics departments now have a robust system in place for the analysis of patient dosimetry data for setting and comparing against DRLs for diagnostic radiology. The use of electronic records, such as those produced by Radiology Information Systems, greatly contributes to the scale and efficiency of this process.7,8

The use of X-ray imaging alongside other modalities, such as radiotherapy and nuclear medicine (NM), is now established as standard practice. Hybrid imaging, such as single-photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, is commonly used in NM and its use will undoubtedly increase with time. NDRLs are available for the SPECT and PET component of examinations, in terms of administered activity;9 but, there is currently a lack of information on NDRLs for the CT component. Considering the contribution to the overall patient dose that a CT scan can incur, attention should be given to the establishment of DRLs for the CT component of hybrid imaging. Some previous work has been carried out towards this end for PET/CT,10,11 but less progress has been made for SPECT/CT. As a result, the Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine established a Working Party (WP) to collect data and propose UK NDRL values for the CT component of common SPECT/CT examinations, as well as PET/CT. Although publication of the full report is awaited at the time of writing, the WP has made available the proposed NDRL values, thus providing useful data for comparison of doses12—these are reproduced in Table 1.

Table 1.

Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine Working Party proposed National Diagnostic Reference Levels (NDRLs) for common nuclear medicine CT examinations12

| Examination type | CT purpose | Proposed NDRL |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CTDIvol (mGy) | DLP (mGy cm) | ||

| PET half body | Localization | 4.3 | 400 |

| Parathyroid | Localization | 5.6 | 170 |

| Bone | Localization | 5.6 | 180 |

| Octreotide/metaiodobenzylguanidine | Localization | 5.4 | 240 |

| Thyroid post ablation | Localization | 5.9 | 210 |

| SPECT/PET cardiac | Attenuation correction | 2.0 | 34 |

CTDIvol, CT Dose Index Volume; DLP, dose–length product; PET, positron emission tomography; SPECT, single-photon emission CT.

The present work grew from a desire to carry out informed audit and optimization of NMCT. Early discussions revealed unexpected difficulties not typically encountered when carrying out patient dosimetry analysis for conventional diagnostic radiology CT (which shall be referred to as “radiology CT”). Traditionally, CT data are divided according to anatomy, i.e. the body region being scanned (e.g. head, lumbar spine). However, NMCT is more complex. The first division must be according to the NM examination type (e.g. bone, octreotide, parathyroid). As local NM protocols for some of these examinations include limiting the CT component to the body region of particular interest, a second division is required according to the body region included in the CT scan. Finally, NMCT includes scans for different clinical purposes (attenuation correction, localization and so on) which result in quite different scan protocols. At our centre (a large UK hospital), this has resulted in the development and use of four distinct dose modes depending on scan purpose—these are described in Table 2. In summary, data for analysis must be divided according to NM examination type, the body region being scanned and the dose mode.

Table 2.

CT dose modes developed for nuclear medicine at our centre

| Dose mode | CT purpose | kV | CAREDose4D quality reference mAsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Attenuation correction | 130 | 10–16 |

| Moderate | Localization | 130 | 40 |

| Standard | Diagnostic CT | 130 | 150 |

| Metal | Patients with orthopaedic implants | 130 | 330 |

Values are approximate, as actual value depends on body region.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Data have been collected from examinations performed on the two SPECT/CT scanners [Siemens Symbia T16 (16 slice) and Siemens Symbia T (2 slice)—(Siemens Healthcare, Forcheim, Germany)], and a PET/CT scanner [Siemens Biograph mCT Flow (64 slice)—(Siemens Healthcare, Forcheim, Germany)] at our centre. Both SPECT/CT and the PET/CT scanners utilize tube current modulation (Siemens CAREDose4D). Most examination data were captured in the computed radiological information system (CRIS). CRIS downloads provided information on the NM examination type, date of birth, date of examination and dose–length product (DLP). These downloads provided sufficient information to perform dose analysis for PET/CT and cardiac SPECT/CT examinations, as these are not associated with different dose modes and body regions.

Owing to the low frequency of SPECT/CT examinations compared with radiology CT, data were collected from November 2014 to July 2016; PET/CT data were collected from April to August 2016, i.e. after the installation of the new equipment. In total, data were analyzed for approximately 1300 patients undergoing PET, 2900 patients undergoing cardiac SPECT/CT and 500 other patients undergoing SPECT/CT. For SPECT/CT examinations (excluding cardiac SPECT/CT), NM technologists manually recorded information on paper including the body region, dose mode and CT scanner used. The CRIS data and paper records were matched using the patient identification number and examination date found on both records. For the common SPECT/CT examinations, data were divided in terms of the NM examination type, body region, scanner and dose mode. The mean and standard deviation of DLPs for common NMCT examinations were then calculated. Data were subjectively assessed and any obvious outliers removed from the analysis. Although information was not routinely available on patient weight, paediatric data were identified and removed from the analysis. Only examinations with 10, or more, patients were analyzed. LDRLs will be set and reviewed early in each calendar year in accordance with our local patient dosimetry audit cycle.

RESULTS

Tables 3–5 show how the mean DLP for NMCT examinations compares with proposed NDRLs,12 where available. The mean DLP for fludeoxyglucose PET/CT was a combination of half-body and whole-body scans (as they are not specifically identified on CRIS), whilst the proposed NDRL was based on half-body scans only.

Table 3.

Comparison between mean dose–length product (DLP) and proposed National Diagnostic Reference Levels (NDRLs) for different nuclear medicine (NM) examination types, body region and dose modes for bone single-photon emission CT/CT examinations

| NM examination type | Body region | CT scanner | Dose mode | DLP (mGy cm) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean DLP (number of patients) | Standard deviation | Proposed NDRLs12 | ||||

| Bone | Pelvis | T | Moderate | 105 (15) | 40 | 180 |

| Pelvis | T16 | Standard | 558 (11) | 111 | ||

| Pelvis | T16 | Metal | 1359 (34) | 322 | ||

| T-spine | T | Moderate | 133 (13)a | 40 | 180 | |

| T-spine/L-spine | T | Moderate | 124 (15)a | 26 | 180 | |

| T-spine/L-spine | T16 | Standard | 704 (24) | 306 | ||

| L-spine | T | Moderate | 107 (47) | 33 | 180 | |

| L-spine | T16 | Moderate | 170 (24) | 70 | 180 | |

| L-spine | T16 | Standard | 634 (33) | 226 | ||

| L-spine | T16 | Metal | 1086 (12) | 430 | ||

| Knees | T16 | Standard | 230 (10) | 130 | ||

| Knees | T16 | Metal | 913 (111) | 285 | ||

| Feet/ankles | T | Standard | 153 (10) | 44 | ||

| Feet/ankles | T16 | Standard | 221 (32) | 39 | ||

See Table 6 for updated data following additional validation.

Table 5.

Comparison between mean dose–length product (DLP) and proposed National Diagnostic Reference Levels (NDRLs) for different nuclear medicine (NM) examination types, body region and dose modes for positron emission tomography (PET)/CT examinations

| NM examination type | Body region | CT scanner | Dose mode | DLP (mGy cm) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean DLP (number of patients) | Standard deviation | Proposed NDRLs12 | ||||

| FDG | Whole/half body | PET | Moderate | 346 (1192) | 164 | 400a |

| Brain | PET | Moderate | 563 (30) | 163 | ||

| F-18 choline | Half body | PET | Moderate | 319 (95) | 98 | |

FDG, fludeoxyglucose.

Based on half-body scan.

Table 4.

Comparison between mean dose–length product (DLP) and proposed National Diagnostic Reference Levels (NDRLs) for different nuclear medicine (NM) examination types, body region and dose modes for parathyroid, octreotide and cardiac single-photon emission CT/CT examinations

| NM examination type | Body region | CT scanner | Dose mode | DLP (mGy cm) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean DLP (number of patients) | Standard deviation | Proposed NDRLs12 | ||||

| Parathyroid | Neck | T | Moderate | 66 (19) | 20 | 170 |

| Neck | T16 | Moderate | 120 (42) | 36 | 170 | |

| Octreotide | Abdomen | T16 | Moderate | 280 (15) | 97 | 240 |

| Abdomen/pelvis | T16 | Moderate | 204 (14) | 109 | 240 | |

| Chest/abdomen/pelvis | T16 | Moderate | 377 (32) | 164 | 240 | |

| Head/chest/abdomen/pelvis | T16 | Moderate | 373 (10) | 151 | 240 | |

| Cardiac | Heart | T16 | Low | 34 (2889) | 1 | 34 |

For the Siemens Symbia T16 scanner, sufficient numbers were available for bone SPECT/CT lumbar spine examinations in three of the four dose modes; the distinction between the dose modes is illustrated in Figure 1. Although insufficient numbers were available for more complete analysis, the low-dose mode has also been included on Figure 1 to illustrate this point.

Figure 1.

Mean dose–length product (DLP) data for bone single-photon emission CT/CT lumbar spine examinations in the four dose modes: the thick black markers indicate the mean, the boxes indicate the first and third quartiles, the thin lines inside the boxes indicate the median and the whiskers indicate the smallest and largest values. The dashed line indicates the proposed National Diagnostic Reference Level for localization (moderate dose mode).12

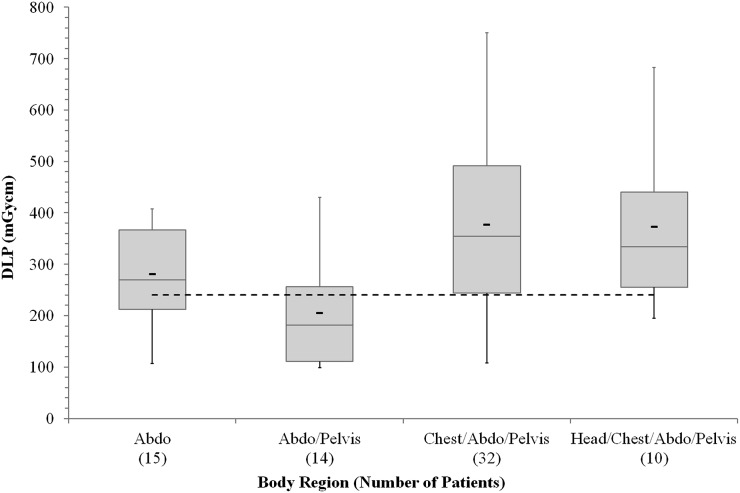

The results for several body regions of octreotide examinations indicate that the proposed NDRL has been exceeded. The results for each body region for which there were sufficient data (all in moderate dose mode) are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mean dose–length product (DLP) data for octreotide single-photon emission CT/CT examinations in four body regions, for the moderate dose mode: the thick black markers indicate the mean, the boxes indicate the first and third quartiles, the thin lines inside the boxes indicate the median and the whiskers indicate the smallest and largest values. The dashed line indicates the proposed National Diagnostic Reference Level.12 Abdo, abdomen.

DISCUSSION

The importance of dividing the data according to dose mode is shown in Figure 1; the four dose modes clearly give rise to four distinct dose ranges. Although there is some overlap in the extremes (i.e. the smallest and largest doses), this is likely due to the use of tube current modulation compensating for different patient sizes. Setting a generic LDRL would therefore be inappropriate. The use of multiple scan purposes (i.e. dose modes) is supported in the latest European Association of Nuclear Medicine guidelines.13 The Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine WP has currently only proposed NDRL values for a limited range of scan purposes—mostly localization (equivalent to moderate dose mode).12

With the exception of some octreotide scans, most of the NMCT examinations have a mean DLP lower than the proposed NDRL. Whilst the proposed NDRLs specify the NM examination type and scan purpose (analogous to dose mode), details of the body region are not provided. SPECT-guided CT [the field of view (FOV) of the CT scan is limited to the specific area of interest on the SPECT scan] is a form of dose optimization and therefore should be, and is, encouraged; for the same patient, scanning a longer length would give rise to a higher DLP, although in some cases it is necessary to include additional anatomy to provide landmarks for fusion of the SPECT and CT images.

For bone SPECT/CT examinations on the Siemens Symbia T scanner in moderate dose mode, the mean DLP for T-spine examinations is comparable with that for T-spine/L-spine (Table 3). This is unexpected, as it would be anticipated that longer scans (i.e. more body regions) would give rise to higher mean DLPs.

It may be the case that the examinations have simply been inconsistently named on paper records. To investigate this further, a post-audit validation was undertaken on the 13 T-spine and 15 T-spine/L-spine bone SPECT/CT examinations on the Siemens Symbia T scanner in moderate dose mode. This involved retrospectively inspecting the CT images and checking that the paper records accurately recorded the body region. As a result of this validation exercise, data for two examinations were removed as they included additional body regions and data for four examinations were corrected between T-spine and T-spine/L-spine (two cases had been labelled as T-spine which should have been labelled T-spine/L-spine and two cases vice versa). The data were then reanalyzed (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of dose–length product (DLP) results for bone single-photon emission CT/CT examinations in moderate dose mode on the Siemens Symbia T Scanner pre- and post-image validation

| Body region | Pre-image validation |

Post-image validation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean DLP (number of patients) | Standard deviation | Mean DLP (number of patients) | Standard deviation | |

| T-spine | 133 (13) | 40 | 125 (12) | 28 |

| T-spine/L-spine | 124 (15) | 26 | 126 (14) | 37 |

This exercise highlights a difficulty in dependence on paper records; a consistent naming convention must be used by all staff involved in scanning patients. Further discussions revealed that the matching of the T-spine and T-spine/L-spine DLPs is due to a tendency to perform a CT scan over a full single FOV of the gamma camera, meaning that the scan lengths are consistent and that it is only the positioning of the FOV which changes.

For octreotide SPECT/CT examinations (Figure 2), the chest/abdomen/pelvis and head/chest/abdomen/pelvis tend to give higher average DLPs, since they are longer scans; they are expected to cover two FOVs of the gamma camera. Unexpectedly, the average DLP for abdomen examinations was higher than that for abdomen/pelvis examinations. However, the numbers are quite low and the ranges overlap suggesting that this may not be statistically significant. It is believed this is related to both of these scans covering a single FOV, meaning that they are of equal scan length. The use of tube current modulation also introduces variation in the results and this is difficult to account for owing to the lack of information on patient weights. Further data collection should help address this with greater confidence.

It is also noted that the Siemens Symbia T16 scanner gives rise to higher mean DLPs than the Siemens Symbia T scanner indicating that there may be scope for further dose optimization, although this could be limited owing to the technology both in terms of relative tube capabilities and number of slices. In terms of tube capabilities, the Siemens Symbia T16 scanner has a maximum current of 345 mA, whereas the Siemens Symbia T scanner has a maximum current of 240 mA, giving the Siemens Symbia T16 scanner an inherent capability to deliver higher DLPs when tube current modulation is used. The multislice nature of the T16 scanner also gives the potential to deliver higher DLPs.14

To avoid the need to divide the data according to body region, dose could be recorded in terms of CT Dose Index Volume (CTDIvol); the proposed NDRLs are also available as CTDIvol.12 CTDIvol, however, is not currently routinely captured in CRIS downloads. Planned CTDIvol data for the CT protocols provide a potential method for comparison, although this may not always reflect the patient-specific values because of the use of automatic tube current modulation which would cause the CTDIvol to vary throughout the scan length.

For fludeoxyglucose PET/CT (half/whole body), the mean DLP was based on a combination of half- and whole-body examinations; half- and whole-body scans are not separated on CRIS. However, it is encouraging that compliance with the proposed NDRL is still being achieved, as the inclusion of full-body data would be expected to increase the mean DLP.

Patient dosimetry for NMCT presents a number of difficulties which may not be encountered for radiology CT. Among these is the necessity to divide the data according to NM examination type, body region and dose mode. In the National Health Service, radiology CT scans are performed approximately 170 times as often as SPECT scans.15 Not all SPECT-capable gamma cameras have CT built in, which means SPECT/CT examinations would be performed even less frequently. Owing to the relatively low frequency of SPECT/CT examinations, obtaining sufficient patient numbers proved challenging; data were collected over a 20-month period, i.e. from November 2014 to July 2016. This was further compounded by the necessity to divide the data into smaller groups. This may cause significant difficulties at many centres, as smaller centres may have to collect data over longer periods, or identify other acceptable dose audit methods to carry out meaningful patient dosimetry analysis.

For radiology CT, examination type, body region and DLP are captured on CRIS and the system can readily be used for patient dosimetry analysis with minimal additional manipulation of the data. However, for NMCT, only the NM examination type (e.g. bone, octreotide, parathyroid) and DLP are captured. It was, therefore, necessary to depend on paper records to capture the remaining information, i.e. body region and dose mode. Since neither CRIS nor the paper records, captured all of the required information, it was necessary to do a manual search. Compounding these issues, different technologists used different terminology to describe a body region, e.g. “lumbar spine” and “L-spine”. This again required manual interrogation of data for a large number of examinations. A final issue with paper records, especially for a new process, is that of compliance. In some cases, not all of the required information was completed and it was necessary to complete this retrospectively.

CONCLUSION

A system has been developed for carrying out a patient dose audit for NMCT and the non-trivial challenges associated with it have been highlighted. Data not recorded on CRIS have been thoroughly interrogated and recorded manually. Whilst this method of audit is labour intensive and is open to the possibility of error in the manual transcription/editing of data, it does provide a useful basis for establishing LDRLs and provides a baseline for dose optimization. Following this audit, further improvements have been put in place to capture more data electronically through the CRIS system, removing the reliance on paper records. Local guidance on consistent naming of body regions has also been put in place to improve accuracy. Compliance with the new system will be closely monitored. LDRLs will be set and reviewed early in each calendar year in accordance with our local patient dosimetry audit cycle. By setting LDRLS, potential avenues for optimization can be identified.

NDRLs are currently proposed only for a limited range of scan purposes (dose modes). However, the importance of auditing in terms of all dose modes has been demonstrated owing to the distinct dose ranges between them. Accounting for body region would also be beneficial, although more data are required to draw firm conclusions on this.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our thanks go to our colleagues in the Nuclear Medicine department for completing the paper records, particularly Kenneth Parker and Samantha Holt for co-ordinating the collection of the data and Sophie Bissel for retrospectively filling the gaps in the data.

Contributor Information

Matthew Gardner, Email: matthew.gardner@uhb.nhs.uk.

Ngonidzashe M Katsidzira, Email: NgonidzasheMichael.Katsidzira@uhb.nhs.uk.

Erin Ross, Email: Erin.Ross@uhb.nhs.uk.

Elizabeth A Larkin, Email: Elizabeth.Larkin@uhb.nhs.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.IPEM. Guidance on the establishment and use of diagnostic reference levels for medical X-ray examinations. Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine. Report number: 88; 2004.

- 2.The ionising radiation (medical exposure) regulations 2000. SI 2000/1059. London, UK: The Stationery Office; 2000.

- 3. European Community. Council Directive 2013/59/EURATOM. Laying down basic safety standards for protection against the dangers arising from exposure to ionising radiation. Off J Eur Union 2013 [Cited 29 September 2016]; Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2014:013:0001:0073:EN:PDF.

- 4.Hart D, Hillier MC, Shrimpton PC. Doses to patients from radiographic and fluoroscopic X-ray imaging procedures in the UK—2010 review. Health Protection Agency. Report number: HPA-CRCE-034, 2012.

- 5.Shrimpton PC, Hillier MC, Meeson S, Golding SJ. Doses from computed tomography (CT) examinations in the UK—2011 review. Public Health England. Report Number: PHE-CRCE-013, 2014.

- 6. Public Health England. National diagnostic reference levels (NDRLs). [Accessed 29 September 2016]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/diagnostic-radiology-national-diagnostic-reference-levels-ndrls/national-diagnostic-reference-levels-ndrls.

- 7.Charnock P, Moores BM, Wilde R. Establishing local and regional DRLs by means of electronic radiographical X-ay examination records. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2013; 157: 62–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/nct125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charnock P, Dunn AF, Moores BM, Murphy J, Wilse R. Establishment of a comprehensive set of regional DRLs for CT by means of electronic X-ray examination records. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2015; 163: 509–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncu235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ARSAC. Notes for guidance on the clinical administration of radiopharmaceuticals and use of sealed radioactive sources. Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee 2016. [PubMed]

- 10.Etard C, Celier D, Roch P, Aubert B. National survey of patient doses from whole-body FDG PET-CT examinations in France in 2011. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2012; 152: 334–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/ncs066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jallow N, Christian P, Sunderland J, Graham M, Hoffman JM, Nye JA. Diagnostic reference levels of CT radiation dose in whole-body PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 238–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.115.160465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bebbington N, Burniston M, Edyvean S, Fraser L, Julyan P, Parkar N, et al. UK national reference doses for CT scans performed in hybrid imaging studies. J Nucl Med 2016; 57(Suppl. 2): 594. [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Wyngaert T, Strobel K, Kampen WU, Kuwert T, van der Bruggen W. The EANM practice guidelines for bone scintigraphy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016; 43: 1723–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-016-3415-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golding SJ. Multi-slice computed tomography (MSCT): the dose challenge of the new revolution. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2005; 114: 303–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/rpd/nch545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHS England. Diagnostic Imaging Dataset Annual Statistical Release 2015/16 2016.