Abstract

Many studies have been performed to investigate the correlation of leptin (LEP) and leptin receptor (LEPR) polymorphisms with breast cancer (BC) risk, however the results are inconclusive. To obtain a more precise estimation, we conducted this meta-analysis. We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases to identify qualified studies. Pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate the association. Eight eligible studies (2,124 cases and 5,476 controls) for LEP G2548A (rs7799039) polymorphism, and thirteen studies (5,282 cases and 6,140 controls) for LEPR Q223R (rs1137101) polymorphism were included in our study. In general, no significant association between LEP G2548A polymorphism and BC susceptibility was found among five genetic models. In the stratified analysis by ethnicity and sources of controls, significant associations were still not detected in all genetic models. For LEPR Q223R polymorphism, we observed that the association was only statistically significant in Asians (G versus A: OR = 0.532, P = 0.009; GG versus AA: OR = 0.233, P = 0.002; GA versus AA: OR =0.294, P = 0.006; GG versus AA+AG: OR =0.635, P = 0; GA+GG versus AA: OR = 0.242, P = 0.003), but not in general populations and Caucasians. In conclusion, LEP G2548A polymorphism has no relationship with BC susceptibility, while LEPR Q223R polymorphism could decrease BC risk in Asians, but not in overall individuals and Caucasians. More multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are required for further investigation.

Keywords: breast cancer, leptin, leptin receptor, polymorphisms

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is a complex and heterogeneous disease and has become a challenging health issue confronted by women worldwide [1, 2]. Previous studies have indicated that obesity is one of the risk factors for postmenopausal women with BC; in addition, weight gain is associated with poor prognosis of premenopausal BC [3, 4]. However, the exact pathogenesis of obesity in the occurrence and development of BC is still unclear. In recent years, leptin, a hormone secreted by adipocytes, has been recognized as one of the plausible mechanisms for carcinogenesis in obese individuals [5].

Leptin is the product of the ob gene that plays a pivotal role in regulating food intake, energy expenditure and neuroendocrine function; furthermore, high levels of leptin have been frequently observed in obese subjects [6, 7, 8]. Several published studies have shown that leptin can regulate endothelial cell proliferation and promote angiogenesis; moreover, it has an association with progression and poor survival of BC [9, 10, 11]. Leptin exerts it physiological action through the leptin receptor which is overexpressed in BC [12]. Genetic variations in some obesity-related genes have been demonstrated to affect BC risk by the levels and functioning of leptin [13, 14, 15]. Over the past few decades, two obesity-related gene polymorphisms have been most commonly reported: LEP G2548A rs7799039, and LEPR Q223R rs1137101. Leptin G2548A polymorphism, located in the promoter region of the leptin gene, has been demonstrated to correlate with variations in serum leptin levels, degree of obesity, as well as cancer susceptibility [16, 17]. LEPR Q223R polymorphism alters amino acid change from neutral to positive that could affect the functionality of the receptor and modifies its signaling capacity [18, 19].

Nevertheless, the studies about rs7799039 and rs1137101 polymorphisms with the risk of BC at present were still controversial: the study by Liu et al. [20] discovered that no significant association between rs7799039 polymorphism and BC risk; while Yan et al. [21] found the Leptin G2548A gene polymorphism played an important role in BC susceptibility, especially among Caucasians. Similarly, results of previous publications for LEPR Q223R rs1137101 and BC risk were also inconsistent [22, 23, 24]. As some new studies published, we conducted this systemic meta-analysis to clarify the role of genetic variants among leptin and leptin receptor in the occurrence and development of BC.

RESULTS

Characteristics of included studies

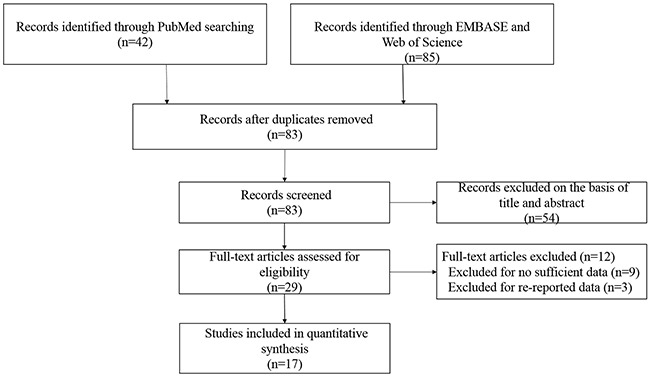

The complete search process is presented in Figure 1. According to the search strategy described in the methods and materials section, 127 publications were preliminaries identified. Then we removed duplicate articles, and eighty-three records remained. After reading titles and abstracts of all the studies, we further excluded fifty-four articles that were obviously unrelated. Then, a total of twenty-nine studies were subject to full-text examination. Consequently, eight eligible studies about LEP G2548A polymorphism and thirteen articles about LEPRQ223R polymorphism were included in our meta-analysis. The characteristics of the eligible studies are presented in Table 1. All these included studies were in accordance with the pathological diagnostic criteria of BC and all the papers were published between 2006 and 2017.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the selection of the studies in this meta-analysis.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| First author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Genotyping method | Number (case/control) | Sources of controls | HWE (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEPG2548A (rs7799039) | |||||||

| Rodrigo et al. [32] | 2017 | Sri Lanka | Caucasian | PCR | 80/80 | PB | 0.890 |

| Cleveland et al. [33] | 2010 | USA | Caucasian | PCR | 1059/1101 | PB | 0.118 |

| Morris et al. [26] | 2013 | Mexico | Mixed | PCR | 130/189 | HB | 0.940 |

| Rostami et al. [34] | 2015 | Iran | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | 203/171 | HB | 0.383 |

| Mahmoudi et al. [35] | 2015 | Iran | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | 45/41 | PB | 0.930 |

| Karakus et al. [36] | 2015 | Turkey | Caucasian | PCR | 199/185 | PB | 0.407 |

| Snoussi et al. [25] | 2006 | Tunisia | Mixed | PCR-RFLP | 308/222 | Unknown | 0.063 |

| Mohammadzadeh et al. [37] | 2015 | Iran | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | 100/100 | HB | 0.065 |

| LEPRQ223R (rs1137101) | |||||||

| Snoussi et al. [25] | 2006 | Tunisia | Mixed | PCR-RFLP | 308/222 | Unknown | 0.162 |

| Woo et al. [38] | 2006 | Korean | Asian | PCR | 45/45 | HB | 0.513 |

| Gallicchio et al. [39] | 2007 | USA | Caucasian | Taqman | 53/872 | PB | 0.260 |

| Han et al. [40] | 2008 | China | Asian | PCR | 240/500 | HB | 0.0009 |

| Okobia et al. [41] | 2008 | Nigeria | African | PCR-RFLP | 209/209 | HB | 0.704 |

| Teras et al. [27] | 2009 | USA | Caucasian | SNP stream | 648/659 | PB | 0.090 |

| Cleveland et al. [33] | 2010 | USA | Caucasian | PCR | 1059/1098 | PB | 0.333 |

| Nyante et al. [42] | 2011 | USA | Mixed | PCR | 1972/1775 | PB | 0.219 |

| Kim et al. [43] | 2012 | Korean | Asian | PCR | 390/447 | HB | 0.975 |

| Mahmoudi et al. [35] | 2015 | Iran | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | 45/41 | PB | 0.730 |

| Wang et al. [44] | 2015 | China | Asian | PCR-RFLP | 150/128 | PB | 0.074 |

| Rodrigo et al. [32] | 2017 | Sri Lanka | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | 80/80 | PB | 0.000 |

| Mohammadzadeh et al. [45] | 2014 | Iran | Caucasian | PCR-RFLP | 100/100 | HB | 0.693 |

HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium for controls; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; PCR-RFLP: polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism; PB: population-based study; HB: hospital-based study.

Meta-analysis results

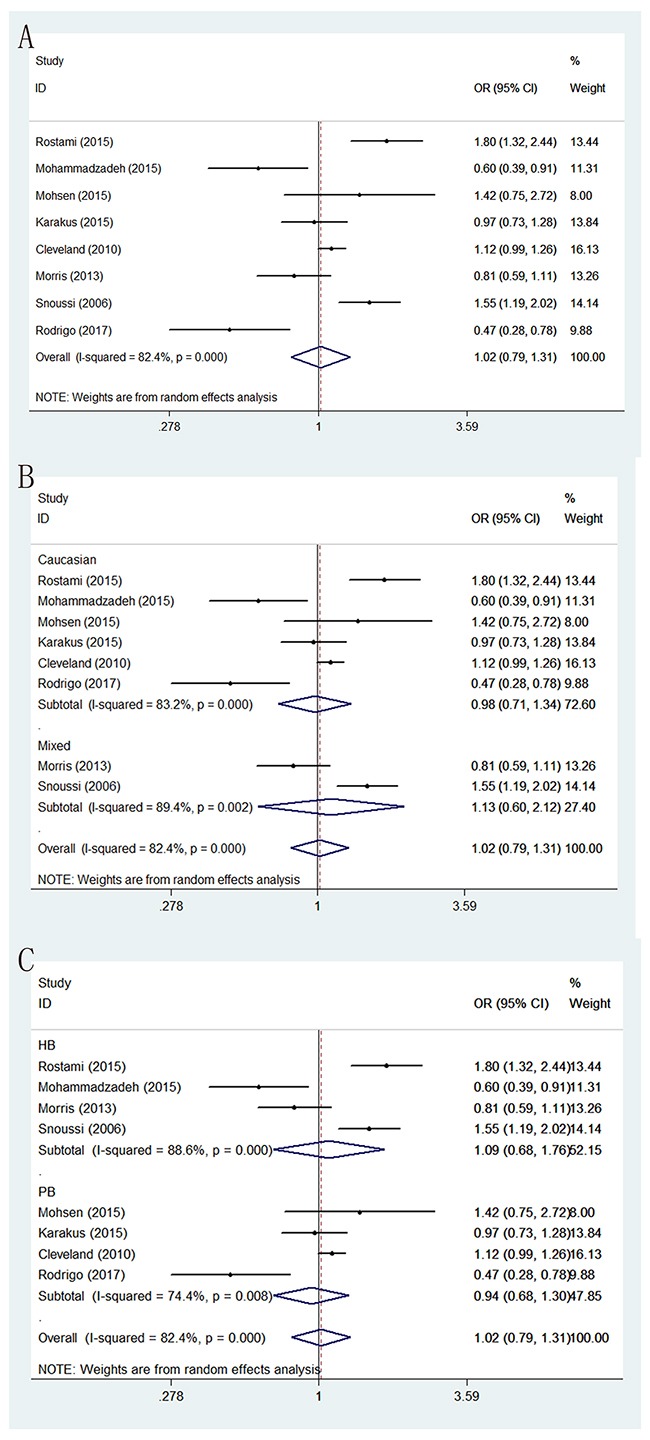

Genotype, distribution and allele frequency of the two polymorphisms are shown in Table 2, and the main results of this meta-analysis are presented in Table 3. For LEP G2548A polymorphism, eight eligible studies with 2,124 BC patients and 2,089 cancer-free controls were finally identified. In general, we did not observe statistically significant association between LEP G2548A polymorphism and BC risk under the genetic models of AA versus GG, GA versus GG, AA+GA versus GG, AA versus GA+GG and G-allele versus A-allele (OR = 1.105 with 95 % CI 0.699-1.749, OR = 0.991 with 95 % CI 0.857-1.147, OR = 1.081 with 95 % CI 0.942-1.241, OR = 1.074 with 95 % CI 0.692-1.668 and OR = 1.02 with 95 % CI 0.792-1.134, respectively). In subgroup analysis by sources of controls, we also found no significant association between LEP G2548A polymorphism and the risk of BC among these five genetic models. Similarly, further stratified analysis by ethnicity showed no significant correlation between LEP G2548A polymorphism and BC susceptibility in all the ethnic groups (Table 3) (Figure 2).

Table 2. Genotype distribution and allele frequency of LEPG2548A (rs7799039) and LEPRQ223R (rs1137101) polymorphisms in cases and controls.

| First author | Genotype (N) | Allele frequency (N) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | |||||||||

| Total | AA | AG | GG | Total | AA | AG | GG | A | G | A | G | |

| LEPG2548A (rs7799039) | ||||||||||||

| Rodrigo et al. | 80 | 32 | 43 | 5 | 80 | 53 | 24 | 3 | 107 | 53 | 130 | 30 |

| Cleveland et al. | 1059 | 226 | 492 | 341 | 1101 | 180 | 561 | 360 | 944 | 1174 | 921 | 1281 |

| Morris et al. | 130 | 22 | 71 | 37 | 189 | 46 | 95 | 48 | 115 | 145 | 187 | 191 |

| Rostami et al. | 203 | 115 | 64 | 24 | 171 | 63 | 77 | 31 | 294 | 112 | 203 | 139 |

| Mahmoudi et al. | 45 | 27 | 11 | 7 | 41 | 17 | 19 | 5 | 65 | 25 | 53 | 29 |

| Karakus et al. | 199 | 49 | 105 | 45 | 197 | 47 | 98 | 40 | 203 | 195 | 192 | 178 |

| Snoussi et al. | 308 | 37 | 152 | 119 | 222 | 11 | 99 | 112 | 226 | 390 | 121 | 323 |

| Mohammadzadeh et al. | 100 | 36 | 55 | 9 | 100 | 52 | 45 | 3 | 127 | 73 | 149 | 51 |

| LEPRQ223R (rs1137101) | ||||||||||||

| Snoussi et al. | 308 | 98 | 145 | 65 | 222 | 102 | 90 | 30 | 341 | 275 | 294 | 150 |

| Woo et al. | 45 | 0 | 12 | 33 | 45 | 0 | 8 | 37 | 12 | 78 | 8 | 82 |

| Gallicchio et al. | 53 | 14 | 24 | 15 | 872 | 278 | 443 | 151 | 52 | 54 | 999 | 745 |

| Han et al. | 240 | 33 | 41 | 166 | 500 | 12 | 78 | 410 | 107 | 373 | 102 | 898 |

| Okobia et al. | 209 | 46 | 107 | 56 | 209 | 56 | 107 | 46 | 199 | 219 | 219 | 199 |

| Teras et al. | 648 | 128 | 332 | 181 | 659 | 125 | 314 | 211 | 588 | 694 | 564 | 736 |

| Cleveland et al. | 1059 | 173 | 521 | 355 | 1098 | 187 | 551 | 360 | 867 | 1231 | 925 | 1271 |

| Nyante et al. | 1972 | 494 | 952 | 526 | 1775 | 416 | 847 | 485 | 1940 | 2004 | 1679 | 1817 |

| Kim et al. | 390 | 8 | 88 | 294 | 447 | 6 | 91 | 350 | 104 | 676 | 103 | 791 |

| Mahmoudi et al. | 45 | 19 | 25 | 1 | 41 | 17 | 18 | 6 | 63 | 27 | 52 | 30 |

| Wang et al. | 150 | 20 | 25 | 105 | 128 | 3 | 19 | 106 | 65 | 235 | 25 | 231 |

| Rodrigo et al. | 80 | 65 | 9 | 6 | 80 | 60 | 6 | 14 | 139 | 21 | 126 | 34 |

| Mohammadzadeh et al. | 100 | 25 | 56 | 19 | 100 | 54 | 40 | 6 | 106 | 94 | 148 | 52 |

Table 3. Meta-analysis results.

| OR | 95%CI | P (OR) | Heterogeneity | Effects model | P(Begg) | P(Egger) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | P | |||||||

| LEPG2548A (rs7799039) | ||||||||

| Total | ||||||||

| A VS G | 1.02 | 0.79-1.31 | 0.878 | 82.4% | 0.000 | R | 0.266 | 0.511 |

| AA VS GG | 1.11 | 0.70-1.75 | 0.669 | 71.3% | 0.001 | R | 0.386 | 0.405 |

| GA VS GG | 0.99 | 0.86-1.15 | 0.908 | 12.2% | 0.335 | F | 0.902 | 0.571 |

| AA+GA VS GG | 1.08 | 0.94-1.24 | 0.276 | 46.1% | 0.072 | F | 0.711 | 0.506 |

| AA VS GA+GG | 1.07 | 0.69-1.67 | 0.750 | 84.7% | 0.000 | R | 0.386 | 0.480 |

| Stratification by ethnicity | ||||||||

| Caucasian | ||||||||

| A VS G | 0.98 | 0.71-1.34 | 0.888 | 83.2% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| AA VS GG | 1.05 | 0.64-1.71 | 0.860 | 63.7% | 0.017 | R | - | - |

| GA VS GG | 0.92 | 0.77-1.08 | 0.304 | 0.0% | 0.703 | F | - | - |

| AA+GA VS GG | 1.02 | 0.87-1.19 | 0.817 | 23.8% | 0.255 | F | - | - |

| AA VS GA+GG | 1.03 | 0.62-1.70 | 0.919 | 86.1% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| Mixed | ||||||||

| A VS G | 1.23 | 0.60-2.12 | 0.71 | 89.4% | 0.002 | R | - | - |

| AA VS GG | 1.39 | 0.28-6.90 | 0.69 | 90.6% | 0.001 | R | - | - |

| GA VS GG | 1.27 | 0.94-1.71 | 0.11 | 33.1% | 0.221 | F | - | - |

| AA+GA VS GG | 1.21 | 0.65-2.25 | 0.55 | 76.0% | 0.041 | R | - | - |

| AA VS GA+GG | 1.27 | 0.31-5.11 | 0.74 | 89.6% | 0.002 | R | - | - |

| Stratification by sources of controls | ||||||||

| Population-based control | ||||||||

| A VS G | 0.94 | 0.68-1.30 | 0.696 | 74.4% | 0.008 | R | - | - |

| AA VS GG | 1.22 | 0.98-1.52 | 0.08 | 22.0% | 0.281 | F | - | - |

| GA VS GG | 0.92 | 0.77-1.10 | 0.34 | 0.00% | 0.711 | F | - | - |

| AA+GA VS GG | 1.00 | 0.85-1.18 | 0.99 | 0.00% | 0.842 | F | - | - |

| AA VS GA+GG | 0.98 | 0.53-1.81 | 0.95 | 84.3% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| Hospital-based control | ||||||||

| A VS G | 1.09 | 0.68-1.76 | 0.711 | 88.6% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| AA VS GG | 1.13 | 0.42-3.09 | 0.806 | 85% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| GA VS GG | 1.18 | 0.90-1.53 | 0.229 | 27.9% | 0.245 | F | - | - |

| AA+GA VS GG | 1.14 | 0.69-1.88 | 0.617 | 67.4% | 0.027 | R | - | - |

| AA VS GA+GG | 1.18 | 0.52-2.67 | 0.698 | 88.7% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| LEPRQ223R (rs1137101) | ||||||||

| Total | ||||||||

| G VS A | 0.93 | 0.76-1.23 | 0.450 | 87.4% | 0.000 | R | 0.69 | 0.702 |

| GG VS AA | 0.88 | 0.59-1.30 | 0.508 | 85.5% | 0.000 | R | 0.537 | 0.680 |

| GA VS AA | 1.02 | 0.78-1.34 | 0.867 | 75.4% | 0.000 | R | 0.837 | 0.864 |

| GG VS AA+GA | 0.93 | 0.74-1.15 | 0.488 | 75.2% | 0.000 | R | 0.855 | 0.764 |

| GA+GG VS AA | 0.94 | 0.69-1.28 | 0.693 | 84.0% | 0.000 | R | 0.373 | 0.681 |

| Stratification by ethnicity | ||||||||

| Caucasian | ||||||||

| G VS A | 1.09 | 0.83-1.43 | 0.534 | 81.8% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| GG VS AA | 1.14 | 0.67-1.96 | 0.627 | 79.0% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| GA VS AA | 1.25 | 0.92-1.69 | 0.147 | 53.7% | 0.055 | R | - | - |

| GG VS AA+GA | 1.05 | 0.70-1.58 | 0.801 | 76.0% | 0.001 | R | - | - |

| GA+GG VS AA | 1.20 | 0.84-1.71 | 0.315 | 71.7% | 0.004 | R | - | - |

| Asian | ||||||||

| G VS A | 0.53 | 0.33-0.86 | 0.009 | 80.0% | 0.002 | R | - | - |

| GG VS AA | 0.23 | 0.09-0.59 | 0.002 | 62.8% | 0.068 | R | - | - |

| GA VS AA | 0.29 | 0.12-0.70 | 0.006 | 51.3% | 0.128 | R | - | - |

| GG VS AA+GA | 0.64 | 0.51-0.79 | 0.000 | 49.5% | 0.115 | F | - | - |

| GA+GG VS AA | 0.24 | 0.10-0.61 | 0.003 | 62.2% | 0.071 | R | - | - |

| Stratification by sources of controls | ||||||||

| Population-based control | ||||||||

| G VS A | 0.89 | 0.76-1.05 | 0.173 | 72.5% | 0.001 | R | - | - |

| GG VS AA | 0.84 | 0.61-1.15 | 0.267 | 68.6% | 0.004 | R | - | - |

| GA VS AA | 0.98 | 0.87-1.10 | 0.671 | 8.50% | 0.364 | F | - | - |

| GG VS AA+GA | 0.88 | 0.70-1.11 | 0.276 | 68.1% | 0.005 | R | - | - |

| GA+GG VS AA | 0.94 | 0.85-1.05 | 0.301 | 42.9% | 0.105 | R | - | - |

| Hospital-based control | ||||||||

| G VS A | 0.93 | 0.50-1.72 | 0.82 | 93.1% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| GG VS AA | 0.96 | 0.21-4.45 | 0.96 | 93.3% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| GA VS AA | 0.87 | 0.29-2.63 | 0.80 | 90.4% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

| GG VS AA+GA | 0.96 | 0.57-1.64 | 0.89 | 68.1% | 0.005 | R | - | - |

| GA+GG VS AA | 0.84 | 0.23-3.44 | 0.79 | 93.7% | 0.000 | R | - | - |

F: fixed effects model; R: random effects model.

Figure 2. Forest plots of associations between rs7799039 and breast cancer risk in the allele contrast genetic model.

(A) the overall populations; (B) stratification by ethnicity; (C) stratification by sources of controls.

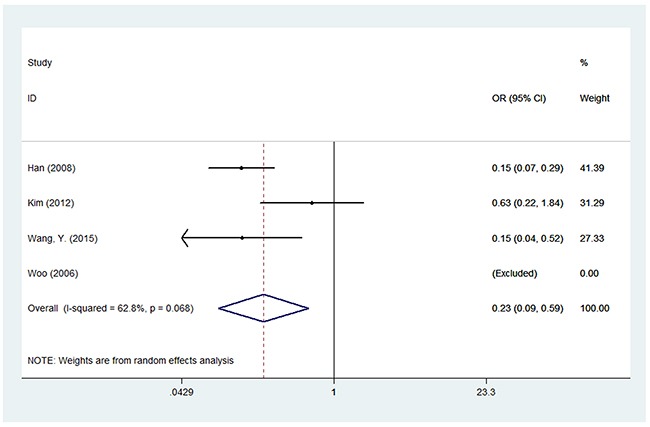

For LEPR Q223R polymorphism, thirteen studies with 5,282 cases and 6,140 controls were used to assess the association between this genetic polymorphism and BC susceptibility. We failed to find a significant association between this polymorphism and BC risk among the five genetic models in overall populations. However, in the subgroup analysis by ethnicity, we found LEPR Q223R polymorphism was associated with a decreased risk of BC among Asians under the five genetic models: G versus A (OR = 0.532, 95% CI = 0.311-0.856, P = 0.009), GG versus AA (OR = 0.233, 95% CI = 0.092–0.59, P = 0.002), GA versus AA (OR = 0.294, 95% CI = 0.124–0.699, P = 0.006), GG versus AA+AG (OR = 0.635, 95% CI = 0.521–0.787, P < 0.001) and GA+GG versus AA (OR = 0.242, 95% CI = 0.097–0.607, P = 0.003), while no meaningful correlation was observed in Caucasians. In addition, we did not observe any association between LEPR Q223R polymorphism and BC risk among the subgroups of population-based controls or hospital-based controls (Table 3) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot of associations between rs1137101 and breast cancer risk among Asians in the homozygote genetic model.

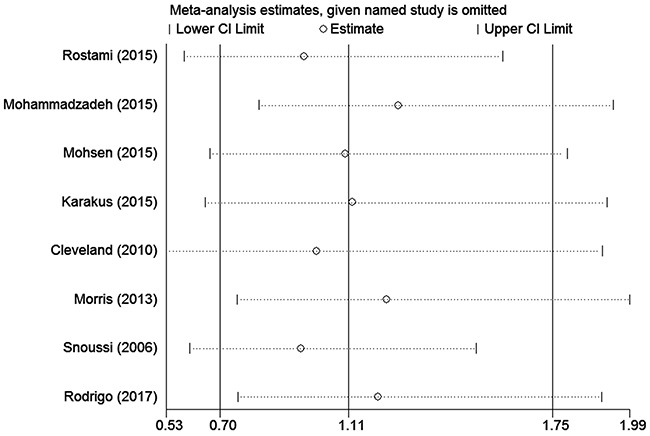

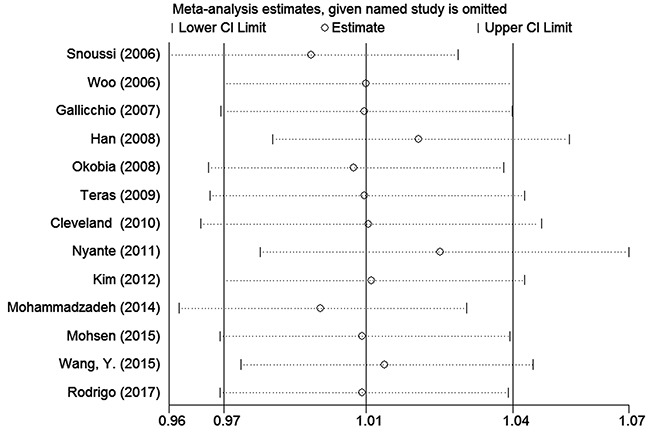

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the stability of the meta-analysis results, sensitivity analysis was performed by deleting one study at a time. After the sensitivity analysis, there was no statistically significant change in the pooled ORs, indicating that our results were reasonable and reliable (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Sensitivity analyses of associations between rs7799039 and breast cancer risk in the homozygote genetic model.

Figure 5. Sensitivity analyses of associations between rs1137101and breast cancer risk in the homozygote genetic model.

Heterogeneity analysis

To determine the heterogeneity among studies in this meta-analysis, we used Q statistic. If the Q test has a P value of < 0.1, we consider significant heterogeneity existed and select random-effects model to perform related statistical analysis; if not, we would use fixed-effects model to carry out our research (Table 3).

Publication bias

Begg's test, Egger's test and funnel plot were carried out to check the publication bias of our studies. All P values of Begg's test and Egger's test were greater than 0.05 (P > 0.05) (Table 3). Besides, no obvious asymmetry could be found in the funnel plot. Therefore, the results did not suggest any evidence of publication bias in this current meta-analysis.

DISCUSSION

With the continuous development of society and the progress of technology, especially the improvement in the field of medicine, the knowledge about BC is constantly updating as time goes on. Recently, obesity has been considered as one of the related factors for BC risk [3, 4]. However, the exact pathogenesis of obesity about this malignancy is still the world's unsolved mystery. Previous published studies have demonstrated that leptin, an adipocyte-derived satiety hormone, is associated with the proliferation, angiogenesis, progression, and poor survival in BC cells, especially in higher grade tumors [5, 7, 9]. Two obesity-related gene polymorphisms (rs7799039, and rs1137101) have been recognized as contributors to BC risk through regulating the level and activity of leptin. Leptin G2548A polymorphism in the promoter region of the leptin gene is a potential source of polymorphism affecting gene expression [16, 17]. LEPR Q223R polymorphism occurs in a region which encodes the extracellular domain of the leptin receptor, acts the function of the receptor, and impairs the ability of leptin to bind to its receptor [18, 19]. To date, the association between rs7799039 and rs1137101 polymorphisms and BC susceptibility remains inconclusive. Therefore, in the cause of a more precise evaluation, we performed this meta-analysis.

LEP G2548A polymorphism, located in the 5’ region of the LEP gene, is implicated in transcription [17]. Several studies have shown that the variants might elevate the serum leptin level through transcriptional level [18]. Snoussi et al. [25] showed that polymorphisms in LEP gene are associated with increased BC risk as well as disease progress, while no association of rs7799039 polymorphism with the risk of BC was observed by another study [26]. We observed no association between LEP G2548A polymorphism and BC risk in general populations, and similar results could be seen in the stratified analysis by ethnicity and sources of controls. In the meta-analysis by Liu et al. [20], three studies were included and the result showed that no significant association between rs7799039 polymorphism and BC risk. Nevertheless, Yan et al. [21] found that the rs7799039 polymorphism plays an important role in BC susceptibility, especially in Caucasians; however, there are some mistakes in her study. First, the study of Vairaktaris et al. [18] is about the association of leptin G2548A polymorphism with increased risk of oral cancer, but not BC. Second, the data in the study of Teras et al. [27] did not seem in accordance with the data provided in their original publication. Compared with them, our study includes two new studies, which will expand the sample size and thus get a more precise evaluation.

Leptin exerted its downstream functioning through binding to leptin receptor [19]. For LEPR Q223R polymorphism, our study showed that no association between this polymorphism and BC risk in overall populations. However, in the subgroup analysis by ethnicity, we found LEPR Q223R polymorphism was associated with a decreased risk of BC among Asians, but not in Caucasians. The differences between Asians and other races may be partly due to the different genetic backgrounds and environments or lifestyles [28]. The same result was found in the meta-analysis by Liu et al. [21] in 2011. Wang et al. [22] observed significant associations between LEPR Q223R polymorphism and BC risk limiting the analysis to studies with controls in agreement with HWE in 2015. Compared with previous published meta-analysis, there was thirteen eligible studies in our study, so our result was more reliable with the larger sample size.

Several potential limitations of this meta-analysis should be addressed. First, our study was conducted without adjustment for several potential confounding variables, because of lacking information including age, smoking status, drinking status, environmental factors, and other habits related to lifestyle, which are known to have significant effects on the risk of BC [29, 30]. Second, there was no study based on Asians background between LEP G2548A polymorphism and the risk of BC, so more studies from different ethnic group should be performed to make our conclusions more persuasive. Last but not least, as a multi-factorial disease, the effect of gene–gene and gene–environmental interactions was not estimated in our study [31].

In summary, LEP G2548A polymorphism has no relationship with BC susceptibility, while LEPR Q223R polymorphism could decrease BC risk in Asians, but not in general individuals and Caucasians. However, given the limited sample size, more multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to clarify the relationships of these polymorphisms with BC risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature and search strategy

We searched PubMed and EMBASE and Web of Science database up to May 1, 2017. The searching strategy was as follows: (breast cancer OR breast carcinoma) AND (polymorphism OR variant OR genotype OR SNP) AND (leptin OR LEP OR LEPR OR leptin gene receptor). The searching was conducted without the limitations of language. Besides, the references of retrieved studies were further examined to identify additional eligible publications.

Inclusion criteria

The studies included in the meta-analysis must meet all the following inclusion criteria: (1) clinical trials studying the association between LEP G2548A, or LEPR Q223R polymorphism and the risk of BC; (2) case-control design; (3) sufficient data for calculation of odds ratio (OR) with confidence interval (CI); (4) all the BC subjects in case groups must be pathologically confirmed. Accordingly, the following exclusion criteria were also used: (1) not case-control studies; (2) abstracts, comments, reviews, meta-analyses, and duplicated publications; (3) no detailed genotyping data; (4) the source of cases and controls, and other essential information were not provided; (5) duplicate studies.

Data extraction

The data from the included studies were independently extracted by two investigators, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion by the research team. The following information was extracted: the first author, year of publication, country of origin, ethnicity, genotyping method, sources of controls, number of cases and controls, and P value for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE).

Statistical analysis

Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to measure the association between these two polymorphisms and BC risk among five genetic models: an allele contrast genetic model, a homozygote genetic model, a heterozygote genetic model, a dominant genetic model, and a recessive genetic model. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by I2 test and Q test. For I2 test, the criteria for heterogeneity were as follows: I2 < 25%, no heterogeneity; 25%-75%, moderate heterogeneity; I2 > 75%, high heterogeneity. If the P value of the Q test was < 0.1, the random-effects model was used; if not, we would select the fixed-effects model to carry out our research. Sensitivity analysis was performed by deleting one study at a time. To evaluate the publication bias, we used Begg's test, Egger's test and funnel plot. Subgroup analysis was performed according to ethnicity and sources of controls. The P value for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was calculated by the chi-square test in the control group in each study. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 10.0 software (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All P values were two sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

GRANT SUPPORT

This study was supported by the Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (grant nos. 2012kw-40-01 and 2014 JM2-8145) and Project of Xi’an Science and Technology Committee SF1416(2).

REFERENCES

- 1.Weigelt B, Reis-Filho JS. Histological and molecular types of breast cancer: is there a unifying taxonomy? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:718–730. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, Gremore TM, Keefe FJ. Psychosocial issues confronting young women with breast cancer. Breast Dis. 2005;23:103–113. doi: 10.3233/bd-2006-23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter CL, Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Bernstein L. Effect of family history, obesity and exercise on breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:96–102. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sellahewa C, Nightingale P, Carmichael AR. Obesity and HER 2 overexpression: a common factor for poor prognosis of breast cancer. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2008;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bao B, Wang Z, Li Y, Kong D, Ali S, Banerjee S, Ahmad A, Sarkar FH. The complexities of obesity and diabetes with the development and progression of pancreatic cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1815:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouloumie A, Drexler HC, Lafontan M, Busse R. Leptin, the product of Ob gene, promotes angiogenesis. Circ Res. 1998;83:1059–1066. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.10.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf G, Chen S, Han DC, Ziyadeh FN. Leptin and renal disease. Am J K Dis. 2002;39:1–11. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.29865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silha JV, Krsek M, Skrha JV, Sucharda P, Nyomba BL, Murphy LJ. Plasma resistin, adiponectin and leptin levels in lean and obese subjects: correlations with insulin resistance. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;149:331–335. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1490331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Artac M, Altundag K. Leptin and breast cancer: an overview. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1510–1514. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferla R, Bonomi M, Otvos L, Jr, Surmacz E. Glioblastoma-derived leptin induces tube formation and growth of endothelial cells: comparison with VEGF effects. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:303. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang G, Platt-Higgins A, Carroll J, de Silva Rudland S, Winstanley J, Barraclough R, Rudland PS. Induction of metastasis by S100P in a rat mammary model and its association with poor survival of breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1199–1207. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleary MP, Ray A, Rogozina OP, Dogan S, Grossmann ME. Targeting the adiponectin: leptin ratio for postmenopausal breast cancer prevention. Front Bioscience (Schol Rd) 2009;1:329–357. doi: 10.2741/S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmandt RE, Iglesias DA, Co NN, Lu KH. Understanding obesity and endometrial cancer risk: opportunities for prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hjartaker A, Langseth H, Weiderpass E. Obesity and diabetes epidemics: cancer repercussions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;630:72–93. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78818-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balistreri CR, Caruso C, Candore G. The role of adipose tissue and adipokines in obesity-related inflammatory diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:802078. doi: 10.1155/2010/802078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Liu P, Guo F, Liu R, Yang Y, Huang C, Shu H, Gong J, Cai M. Genetic G2548A polymorphism of leptin gene and risk of cancer: a meta-analysis of 6860 cases and 7956 controls. J BUON. 2014;19:1096–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suriyaprom K, Tungtrongchitr R, Thawnasom K. Measurement of the levels of leptin, BDNF associated with polymorphisms LEP G2548A, LEPR Gln223Arg and BDNF Val66Met in Thai with metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yapijakis C, Kechagiadakis M, Nkenke E, Serefoglou Z, Avgoustidis D, Vylliotis A, Perrea D, Neukam FW, Patsouris E, Vairaktaris E. Association of leptin -2548G/A and leptin receptor Q223R polymorphisms with increased risk for oral cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:603–612. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0494-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riestra P, Garcia-Anguita A, Torres-Cantero A, Bayonas MJ, de Oya M, Garces C. Association of the Q223R polymorphism with age at menarche in the leptin receptor gene in humans. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:752–755. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C, Liu L. Polymorphisms in three obesity-related genes (LEP, LEPR, and PON1) and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2011;32:1233–1240. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan W, Ma X, Gao X, Zhang S. Association between leptin (-2548G/A) genes polymorphism and breast cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2016;95:e2566. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Yang H, Gao H, Wang H. The association between LEPR Q223R polymorphisms and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang LQ, Shen W, Xu L, Chen MB, Gong T, Lu PH, Tao GQ. The association between polymorphisms in the leptin receptor gene and risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136:231–239. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He BS, Pan YQ, Zhang Y, Xu YQ, Wang SK. Effect of LEPR Gln223Arg polymorphism on breast cancer risk in different ethnic populations: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:3117–3122. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snoussi K, Strosberg AD, Bouaouina N, Ben Ahmed S, Helal AN, Chouchane L. Leptin and leptin receptor polymorphisms are associated with increased risk and poor prognosis of breast carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayra Judith GR, Navarro AD, Arreola SD, Morris MF. The LEP G-2548A polymorphism is not associated with breast cancer susceptibility in obese Western Mexican women. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2013.

- 27.Teras LR, Goodman M, Patel AV, Bouzyk M, Tang W, Diver WR, Feigelson HS. No association between polymorphisms in LEP, LEPR, ADIPOQ, ADIPOR1, or ADIPOR2 and postmenopausal breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2553–2557. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei SF, Chen Y, Xiong DH, Li LM, Deng HW. Ethnic difference in osteoporosis-related phenotypes and its potential underlying genetic determination. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2006;6:36–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen LT, Horby J, Friis E, Pilsgaard B, Jorgensen T. Smoking as a risk factor for wound healing and infection in breast cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:815–820. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carmichael AR. Obesity as a risk factor for development and poor prognosis of breast cancer. BJOG. 2006;113:1160–1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernstein JL, Langholz B, Haile RW, Bernstein L, Thomas DC, Stovall M, Malone KE, Lynch CF, Olsen JH, Anton-Culver H, Shore RE, Boice JD, Jr, Berkowitz GS, et al. Study design: evaluating gene-environment interactions in the etiology of breast cancer - the WECARE study. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R199–214. doi: 10.1186/bcr771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigo C, Tennekoon KH, Karunanayake EH, De Silva K, Amarasinghe I, Wijayasiri A. Circulating leptin, soluble leptin receptor, free leptin index, visfatin and selected leptin and leptin receptor gene polymorphisms in sporadic breast cancer. Endocr J. 2017;64:393–401. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ16-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleveland RJ, Gammon MD, Long CM, Gaudet MM, Eng SM, Teitelbaum SL, Neugut AI, Santella RM. Common genetic variations in the LEP and LEPR genes, obesity and breast cancer incidence and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:745–752. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0503-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rostami S, Kohan L, Mohammadianpanah M. The LEP G-2548A gene polymorphism is associated with age at menarche and breast cancer susceptibility. Gene. 2015;557:154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahmoudi R, Noori Alavicheh B, Nazer Mozaffari MA, Fararouei M, Nikseresht M. Polymorphisms of leptin (-2548 G/A) and leptin receptor (Q223R) genes in Iranian women with breast cancer. Int J Genomics. 2015;2015:132720. doi: 10.1155/2015/132720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karakus N, Kara N, Ulusoy AN, Ozaslan C, Tural S, Okan I. Evaluation of CYP17A1 and LEP gene polymorphisms in breast cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 2015;38:418–422. doi: 10.1159/000438940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohammadzadeh G, Ghaffari MA, Bafandeh A, Hosseini SM, Ahmadi B. The relationship between-2548 G/A leptin gene polymorphism and risk of breast cancer and serum leptin levels in Ahvazian women. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2015;8:100–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woo HY, Park H, Ki CS, Park YL, Bae WG. Relationships among serum leptin, leptin receptor gene polymorphisms, and breast cancer in Korea. Cancer Lett. 2006;237:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallicchio L, McSorley MA, Newschaffer CJ, Huang HY, Thuita LW, Hoffman SC, Helzlsouer KJ. Body mass, polymorphisms in obesity-related genes, and the risk of developing breast cancer among women with benign breast disease. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han CZ, Du LL, Jing JX, Zhao XW, Tian FG, Shi J, Tian BG, Liu XY, Zhang LJ. Associations among lipids, leptin, and leptin receptor gene Gin223Arg polymorphisms and breast cancer in China. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2008;126:38–48. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okobia MN, Bunker CH, Garte SJ, Zmuda JM, Ezeome ER, Anyanwu SN, Uche EE, Kuller LH, Ferrell RE, Taioli E. Leptin receptor Gln223Arg polymorphism and breast cancer risk in Nigerian women: a case control study. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:338. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nyante SJ, Gammon MD, Kaufman JS, Bensen JT, Lin DY, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Hu Y, He Q, Luo J, Millikan RC. Common genetic variation in adiponectin, leptin, and leptin receptor and association with breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:593–606. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1517-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim KZ, Shin A, Lee YS, Kim SY, Kim Y, Lee ES. Polymorphisms in adiposity-related genes are associated with age at menarche and menopause in breast cancer patients and healthy women. Human Reprod. 2012;27:2193–2200. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, Du L, Hem C, Jing J, Zhao X, Wang L, Wang X. Association of expressions and gene polymorphisms of leptin receptor with breast cancer. Cancer Res Clin. 2015;27:740–744. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohammadzadeh G, Ghaffari MA, Bafandeh A, Hosseini SH. Effect of leptin receptor Q223R polymorphism on breast cancer risk. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2014;17:588–594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]