Abstract

Background

Until recently there has been little data available about long-term outcomes of laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. But new randomized controlled trials regarding laparoscopic colorectal surgery have been published. The aim of this study was to compare the short- and long-term oncologic outcomes of laparoscopy and open surgery for rectal cancer through a systematic review of the literature and a meta-analysis of relevant RCTs.

Methods

A systematic review of Medline, Embase and the Cochrane library from January 1966 to October 2016 with a subsequent meta-analysis was performed. Only randomized controlled trials with data on circumferential resection margins were included. The primary outcome was the status of circumferential resection margins. Secondary outcomes included lymph node yield, distal resection margins, disease-free and overall survival rates for 3 and 5 years and local recurrence rates.

Results

Eleven studies were evaluated, involving a total of 2018 patients in the laparoscopic group and 1526 patients in the open group. The presence of involved circumferential margins was reported in all studies. There were no statistically significant differences in the number of positive circumferential margins between the laparoscopic group and open group, RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.89–1.50 and no significant differences in involvement of distal margins (RR 1.13 95% CI 0.35–3.66), completeness of mesorectal excision (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.82–1.82) or number of harvested lymph nodes (mean difference = −0.01, 95% CI −0.89 to 0.87). Disease-free survival rates at 3 and 5 years were not different (p = 0.26 and p = 0.71 respectively), and neither were overall survival rates (p = 0.19 and p = 0.64 respectively), nor local recurrence rates (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.63–1.23).

Conclusions

Laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer is associated with similar short-term and long-term oncologic outcomes compared to open surgery. The oncologic quality of extracted specimens seems comparable regardless of the approach used.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10151-017-1662-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Total mesorectal excision, Rectal cancer, Circumferential resection margin, Survival, Local recurrence, Meta-analysis

Introduction

There has been a constant increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer. Currently it is the most common gastrointestinal malignancy worldwide [1]. Approximately one-third of all large bowel cancers are located in the rectum [1]. So far, the primary treatment option for rectal adenocarcinoma remains surgery, supported by neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy [2, 3].

Over the last two decades, a trend towards minimally invasive surgery in the treatment of rectal cancer has been observed [4]. In selected patients, laparoscopic surgery has been reported to achieve better short-term outcomes, which include: lower postoperative morbidity, reduced intraoperative blood loss, less pain, faster recovery and better quality of life [5–8]. Although there is much evidence supporting laparoscopy in terms of perioperative parameters, little is known of the influence of this surgical technique on long-term outcomes. It is generally accepted that, from the oncologic perspective, disease-free survival is considered a primary endpoint in the assessment of treatment quality in rectal cancer. The most important surgical factors related to long-term oncologic results are clear resection margins and completeness of mesorectal excision. So far, several randomized trials comparing laparoscopic and open surgery have been conducted. However, in most of them the oncologic outcomes are not set as primary endpoints (thus creating potential bias related to underpowering) or full resection details are not reported. Moreover, the evidence on survival after open versus laparoscopic surgery within a randomized controlled trial (RCT) environment is sparse, with these results from high-quality RCTs only recently published [9–11].

Our aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of laparoscopy and open surgery for rectal cancer by systematically reviewing the available literature and conducting a meta-analysis of RCTs comparing short-term and long-term oncologic outcomes.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

In October 2016, a search was conducted by three teams, with two researchers in each, of Medline, Embase and the Cochrane Library, covering a period from January 1966 to October 2016. The search had no language limitations, so that the review would be as comprehensive as possible. A full search strategy for strategy for OVID platform is available in supplement 1. Reference lists of relevant publications were assessed for additional studies. Furthermore, references from other systematic reviews or meta-analyses on the subject were searched.

A study was included when it comprised adult patients, rectal surgery for malignancy and reported on the circumferential resection margin (CRM) status. Only RCTs were included. Studies were excluded if they were not full-text papers, were not RCTs or did not report data on CRM. Studies that fulfilled all the criteria were eligible for further evaluation.

All teams identified and selected citations from the search independently. In case of doubt about inclusion, an attempt was made to reach a consensus within the team. If no consensus was possible, a decision was made by a third member of the group outside that team. Data from included studies were extracted independently by all teams. The study quality and risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures of this systematic review were involved CRM status. Secondary outcome measures were distal resection margin, completeness of mesorectal excision, total number of harvested lymph nodes, 3-year disease-free, 5-year disease-free and overall survival rate as well as local recurrence rate. The quality of mesorectal dissection was classified according to Nagtegaal et al. [12]. For the purpose of subsequent meta-analysis, similarly to Nagtegaal’s original paper ‘complete’ and ‘nearly complete’ mesorectal excisions were grouped together as ‘complete’ and were compared with ‘incomplete’ mesorectal excisions.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using RevMan 5.3 (freeware from the Cochrane Collaboration). Statistical heterogeneity and inconsistency were measured using Cochran’s Q and I 2, respectively. Qualitative outcomes from individual studies were analysed to assess individual and pooled risk ratios (RR) with pertinent 95% confidence intervals (CI) favouring the minimally invasive approach over open surgery and by means of the Mantel–Haenszel fixed-effects method in the presence of low or moderate statistical inconsistency (I 2 ≤ 10%) and by means of a random-effects method (which better accommodates clinical and statistical variations) in the case of high statistical inconsistency (I 2 > 10%). For positive outcomes RR was calculated for ‘non-event’ occurrence. When the study included medians and interquartile ranges, we calculated the mean ± standard deviation (SD) using a method proposed by Hozo et al. [13]. Weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95% CI are presented for quantitative variables using the inverse variance fixed-effects or random-effects method. Statistical significance was observed with a two-tailed 0.05 level for hypothesis and with 0.10 for heterogeneity testing, while unadjusted p values were reported accordingly. This study was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results

The initial reference search yielded 3446 articles. After removing 1721 duplicates, 1725 articles were evaluated through titles and abstracts. This produced 224 papers suitable for full-text review, of which 14 studies met the eligibility criteria [9–11, 14–24]. There were 3 trials (COLOR II, COREAN, CLASICC) in which results were reported in more than one paper. Papers from the same trial were analysed as one study, so that a total of 11 studies were analysed; 2018 patients in the laparoscopic group and 1526 patients in the open group (Table 1). The literature search and study selection is summarized in Fig. 1. Risk of bias in the studies is assessed in Fig. 2. In general, the risk of bias in the studies was low. Due to the nature of the treatment, the blinding of participants and personnel was impossible to perform. The outcome assessment was the main source of bias as most of the studies did not clearly define how and by whom it was performed. The paper with the most potential for bias, Gong et al. [14], has been included in the analysis as it had little impact on heterogeneity.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| First author (Trial name) | Year | Single or multicentre design (SC/MC) | Tumour stage exclusion criteria | Number of participants LAP/OPEN (n) | Female/Male (n) | Mean age LAP/OPEN (years) | Mean distance of the tumour from anal verge LAP/OPEN (cm) | Types of surgery | Neoadjuvant treatment LAP/OPEN n (%) | Ileostomy LAP/OPEN n (%) | Conversion rate n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guillou\Green [18, 19] (CLASICC) | 2005 | MC | Acute intestinal obstruction | 253/128 | ND | ND | ND | TME, APR | ND | ND | 86 (34) |

| Braga [20] | 2006 | SC | T4 | 83/85 | 49/119 | 62.8/65.3 | 9.1/8.6 | TME, APR | 14 (16.9)/12 (14.1) | 22 (26.5)/21 (24.7) | 6 (7.2) |

| Ng [22] | 2008 | SC | T4, size >6 cm | 51/48 | 38/61 | 63.7/63.5 | ND | TME | 0/0 | ND | 5 (9.8) |

| Ng [23] | 2009 | SC | T4, size >6 cm | 76/77 | 68/85 | 66.5/65.7 | ND | APR | ND | ND | 23 (30.3) |

| Lujan [17] | 2009 | SC | T4 | 101/103 | 78/126 | 67.8/66.0 | 5.5/6.2 | TME, APR | 74 (73.0)/79 (77.0) | 48 (47.5)/48 (46.6) | 8 (7.9) |

| Kang\Jeong [16, 24] (COREAN) | 2010 | MC | T4, M1 | 170/170 | 120/220 | 57.8/59.1 | 5.6/5.3 | TME, APR | 170 (100)/170 (100) | 138 (81.2)129 (/75.9) | 2 (1.2) |

| van der Pas\Bonjer [9, 15] (COLOR II) | 2013 | MC | T4 | 699/345 | 385/669 | 66.8/65.8 | ND | PME, TME, APR | 636 (91.0)/317 (92.0) | 243 (34.8)/131 (38.0) | 119 (17) |

| Gong [14] | 2012 | SC | M1 | 67/71 | 60/78 | 58.4/59.6 | ND | TME, APR | ND | ND | 2 (3.0) |

| Ng [21] | 2014 | SC | T4 | 40/40 | 34/46 | 60.2/62.1 | 6.9/7.1 | TME | ND | 20 (50.0)/26 (65.0) | 3 (7.5) |

| Fleshman [10] (ACOSOG Z6051) | 2015 | MC | T4, M1 | 240/222 | 148/314 | 57.7/57.2 | 6.1/6.3 | TME, APR | 236 (98.3)/215 (96.7) | 171 (71.3)/165 (74.3) | 27 (11.3) |

| Stevenson [11] (ALaCaRT) | 2015 | MC | T4 | 238/237 | 162/311 | 65.0/65.0 | ND | TME, APR | 119 (50.0)/117 (49.4) | 68.1/59.5 | 21 (8.8) |

MC multicentre, SC single centre, TME total mesorectal excision (anterior resection), APR abdominoperineal resection, PME partial (upper) mesorectal excision, ND no data, LAP laparoscopic approach, OPEN open approach

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary

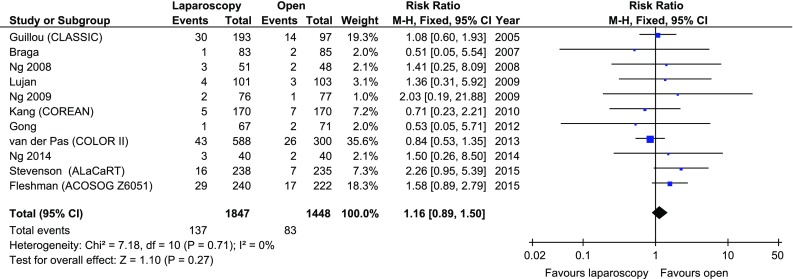

Involved CRMs were reported in all 11 studies. None of the analysed studies showed differences in CRM status between the laparoscopic and open approach. Overall, there were no statistically significant differences in the number of positive CRMs between the laparoscopic group (137/1847 (7.42%)) and the open group (83/1448 (5.73%)), RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.89–1.50, p for effect = 0.27, p for heterogeneity = 0.71, I 2 = 0% (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pooled estimates of involved circumferential resection margins comparing laparoscopy and open surgery. CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, RR risk ratio

Data on involved distal margins were provided in 4/11 studies. None of the analysed studies showed differences in positive distal margins between the laparoscopic and open approach. The analysis revealed no significant differences in distal margin positivity: 6/662 (0.91%) in the laparoscopic group versus 5/645 (0.78%) in the open group, RR 1.13 95% CI 0.35–3.66, p for effect = 0.84, p for heterogeneity = 0.59, I 2 = 0% (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Pooled estimates of involved distal margins comparing laparoscopy and open surgery. CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, RR risk ratio

The data on the completeness of mesorectal excision were reported in 5/11 papers, involving 2339 patients. In 4 papers, the classification proposed by Nagtegaal et al. was used. In the fifth paper, by Ng et al. [21], mesorectal excision was described as complete or incomplete. In the 4 papers which used complete/nearly complete/incomplete classification, complete mesorectal excision occurred in 1093/1308 (83.56%) of laparoscopic cases and 827/951 (86.96%) of open procedures. Nearly complete excision was recorded in 161/1308 (12.30%) laparoscopic and 89/951 (9.36%) open procedures. Incomplete excision was recorded in 54/1308 (4.13%) laparoscopic and 333/951 (3.47%) open procedures. The meta-analysis of all 5 studies reporting completeness of mesorectal excision (complete was combined with nearly complete and compared with incomplete as in Nagtegaal’s classification) revealed no significant differences among the studies: 1290/1348 (95.69%) versus 953/991 (96.17%), RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.82–1.82, p for effect = 0.33, p for heterogeneity = 0.6, I 2 = 0% (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Pooled estimates of completeness of mesorectal excision comparing laparoscopy and open surgery. CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, RR risk ratio

The number of harvested lymph nodes was reported in 9 studies. Kang et al. and van der Pas et al. reported open procedures harvesting a greater number of lymph nodes, whereas Lujan et al. reported the opposite [15, 17, 24]. The remaining studies did not present statistically significant data. Overall, the analysis revealed no statistically significant differences among the studied groups, mean difference = −0.01, 95% CI −0.89 to 0.87, p for effect = 0.98, p for heterogeneity = 0.001, I 2 = 69% (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Pooled estimates of harvested lymph node yield comparing laparoscopy and open surgery. CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, RR risk ratio

The disease-free 3-year survival rate was reported in 5 papers, whereas an overall 3-year survival rate was reported in 6. There were no significant variations among the groups [p = 0.26 and p = 0.18 (Figs. 7, 8)]. Five-year survival and 5-year disease-free survival rates were each reported in by 5 authors. There were no statistically significant differences in 5-year survival rate, p = 0.64. No differences were found in terms of disease-free survival either, p = 0.71 (Figs. 9, 10).

Fig. 7.

Pooled estimates of 3-year disease-free survival rate comparing laparoscopy and open surgery. CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, RR risk ratio

Fig. 8.

Pooled estimates of 3-year overall survival rate comparing laparoscopy and open surgery. CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, RR risk ratio

Fig. 9.

Pooled estimates of 5-year disease-free survival rate comparing laparoscopy and open surgery. CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, RR risk ratio

Fig. 10.

Pooled estimates of 5-year overall survival rate comparing laparoscopy and open surgery. CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, RR risk ratio

The local recurrence rate was reported in 8/11 studies. It ranged from 2.35 to 9.88% in the laparoscopic group, and 4.47–11.11% in the open group. There were no statistically significant variations among the studied groups, RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.63–1.23, p for effect = 0.45, p for heterogeneity = 0.79, I 2 = 0% (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Pooled estimates of local recurrence rate comparing laparoscopy and open surgery. CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom, RR risk ratio

Discussion

We found no difference in circumferential resection margin involvement between laparoscopic and open surgery for rectal cancer. Not difference was found in any other oncological parameter, nor any difference in disease-free or overall survival by 5 years.

The quality of included studies was mostly high and very high. For obvious reasons, none of them blinded the participants and only 5 studies blinded outcome assessors. Although this may create potential bias, one should remember that in surgical RCTs, blinding is either impossible or at the very least, difficult. All analysed studies included groups of patients undergoing laparoscopic resection, no robotic surgery was involved, although there are currently several ongoing trials comparing laparoscopic with robotic surgery registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01736072 (ROLARR), NCT01130233, NCT01985698 (RLOAPR), NCT01591798, NCT02673177 (TRVL), NCT02817126).

The involved CRM rate varied among studies between 1.2 and 15.5% in the laparoscopic group and 1.3–14.43% in the open group. However, there was no overall difference between laparoscopic and open surgery and heterogeneity was low. Differences in CRM involvement between studies may suggest that the quality of surgery varied or (less probably) there were differences in pathologic assessment (there were no pre-operative differences in T stage or use of neoadjuvant therapy between groups). In our meta-analysis, the completeness of total mesorectal excision was similar regardless of the technique used. In a recent meta-analysis by Martínez-Pérez et al. [25], a difference in completeness of mesorectal excision was found favouring open surgery. More studies were included for data extraction in our review and we grouped together ‘complete’ and ‘nearly complete’ resections while Martínez-Pérez et al. compared ‘complete’ resections with a group of flawed excisions (‘nearly complete’ combined with ‘incomplete’). More data are needed to fully establish whether there are differences in overall survival between complete and nearly complete mesorectal excisions.

Abbas et al. [26] highlighted issues that might or might not be relevant to short- and long-term oncologic outcomes in laparoscopic rectal surgery. It was suggested that laparoscopy may be inferior to the open approach due to technical limitations leading to a so-called fulcrum/coning effect during dissection, resulting in positive CRM or incomplete mesorectal excision more often in lower rectal cancers. However, our review we did not find differences in CRM involvement, but only 1 study fully analysed the outcomes in low rectal cancers [15], where statistically different rates of CRM involvement were found in patients with cancer of the lower third of the rectum and interestingly, worse outcomes were observed in the open surgery group (22% involved CRMs in the open group and 9% in laparoscopic group). Certainly, a positive CRM strongly correlates with the height of the tumour [15, 27, 28]. Because of high CRM involvement in low rectal cancers, a novel bottom-up transanal total mesorectal excision has been proposed and currently a multicentre RCT COLOR III trial (NCT02736942) has started to fully assess the oncologic benefits of this approach (estimated primary completion date: May 2020) [29]. There were also differences in conversion rates among studies (1–34%), which confirms the difficulty of the laparoscopic technique and underlines issues with its standardization. High conversion rates are associated with the learning curve and the surgical unit’s experience as well as with tumour stage, which may contribute to worse perioperative outcomes and may also influence survival, although evidence is lacking to draw firm conclusions [30–32].

The number of harvested lymph nodes was similar in the laparoscopic and open group. However, lymph node yield is dependent on many factors such as the tumour itself, the patient, neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy, pathologic assessment [33] and, last but not least, the surgeon [34].

Most importantly, operative technique has no impact on long-term outcomes suggesting that, given the amount of data available further RCTs comparing the laparoscopic and open approach in terms of oncologic outcomes may not be required.

The quality of data in this review has several limitations. In practically all included studies long-term outcomes were not set as a primary endpoint; therefore, most studies were probably underpowered for this parameter. In addition, in most of them involved CRM was used as a universal marker of non-radical operation. However, there is agreement that any involved margin is associated with poor survival. Since distal margins (length and involvement) were not reported in most studies, we were not able to fully assess the R0 resection rate in the analysed groups. According to Parmar et al. [35] in studies involving time to event (survival-type) data, the most appropriate statistics to use are the log hazard ratio and its variance. However, this was not explicitly presented for included studies and we had to compare data after 3 and 5 years post-surgery. Surgeon experience and hospital volume in rectal surgery are important factors influencing outcomes but in this review surgeon experience was not analysed [36–38].

In conclusion, this systematic review with a meta-analysis showed that laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer is associated with similar short-term and long-term oncologic outcomes compared to open surgery. The oncologic quality of specimens seems comparable regardless of the approach used.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Footnotes

M. Pędziwiatr and P. Małczak are equal first authors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10151-017-1662-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Brenner H, Bouvier AM, Foschi R, Hackl M, Larsen IK, Lemmens V, et al. Progress in colorectal cancer survival in Europe from the late 1980s to the early 21st century: the EUROCARE study. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(7):1649–1658. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van de Velde CJ, Boelens PG, Borras JM, Coebergh JW, Cervantes A, Blomqvist L, et al. EURECCA colorectal: multidisciplinary management: European consensus conference colon & rectum. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(1):1.e–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monson JR, Weiser MR, Buie WD, Chang GJ, Rafferty JF, Rafferty J, et al. Practice parameters for the management of rectal cancer (revised) Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(5):535–550. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31828cb66c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Askari A, Nachiappan S, Currie A, Bottle A, Athanasiou T, Faiz O. Selection for laparoscopic resection confers a survival benefit in colorectal cancer surgery in England. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(9):3839–3847. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4686-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arezzo A, Passera R, Scozzari G, Verra M, Morino M. Laparoscopy for rectal cancer reduces short-term mortality and morbidity: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(5):1485–1502. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Wang S, Gao S, Yang C, Yang W, Guo S. Laparoscopic colorectal resection versus open colorectal resection in octogenarians: a systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(3):153–162. doi: 10.1007/s10151-015-1419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ihnát P, Martínek L, Mitták M, Vávra P, Ihnát Rudinská L, Zonča P. Quality of life after laparoscopic and open resection of colorectal cancer. Dig Surg. 2014;31(3):161–168. doi: 10.1159/000363415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujii S, Ota M, Ichikawa Y, Yamagishi S, Watanabe K, Tatsumi K, et al. Comparison of short, long-term surgical outcomes and mid-term health-related quality of life after laparoscopic and open resection for colorectal cancer: a case-matched control study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25(11):1311–1323. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0981-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Haglind E, Group CIS A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):194. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1505367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleshman J, Branda M, Sargent DJ, Boller AM, George V, Abbas M, et al. Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection of stage II or III rectal cancer on pathologic outcomes: the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1346–1355. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevenson AR, Solomon MJ, Lumley JW, Hewett P, Clouston AD, Gebski VJ, et al. Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection on pathological outcomes in rectal cancer: the ALaCaRT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1356–1363. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagtegaal ID, van de Velde CJ, van der Worp E, Kapiteijn E, Quirke P, van Krieken JH, et al. Macroscopic evaluation of rectal cancer resection specimen: clinical significance of the pathologist in quality control. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(7):1729–1734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong J, Shi DB, Li XX, Cai SJ, Guan ZQ, Xu Y. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic total mesorectal excision compared to open surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(48):7308–7313. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, Fürst A, Lacy AM, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(3):210–218. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH, Kim S, Kang SB, Lim SB, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):767–774. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lujan J, Valero G, Hernandez Q, Sanchez A, Frutos MD, Parrilla P. Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery in patients with rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96(9):982–989. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, et al. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1718–1726. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green BL, Marshall HC, Collinson F, Quirke P, Guillou P, Jayne DG, et al. Long-term follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of conventional versus laparoscopically assisted resection in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100(1):75–82. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braga M, Frasson M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Capretti G, Di Carlo V. Laparoscopic resection in rectal cancer patients: outcome and cost-benefit analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(4):464–471. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng SS, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Hon SS, Mak TW, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open total mesorectal excision with anal sphincter preservation for mid and low rectal cancer: a prospective, randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(1):297–306. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng SS, Leung KL, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Teoh AY, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open abdominoperineal resection for low rectal cancer: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2418–2425. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng SS, Leung KL, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Hon SS. Long-term morbidity and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted anterior resection for upper rectal cancer: ten-year results of a prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(4):558–566. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819ec20c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang SB, Park JW, Jeong SY, Nam BH, Choi HS, Kim DW, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): short-term outcomes of an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(7):637–645. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martínez-Pérez A, Carra MC, Brunetti F, de’Angelis N. Pathologic outcomes of laparoscopic vs open mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(4):e165665. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbas SK, Yelika SB, You K, Mathai J, Essani R, Krivokapić Z, et al. Rectal cancer should not be resected laparoscopically: the rationale and the data. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(3):237–240. doi: 10.1007/s10151-017-1596-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rullier A, Gourgou-Bourgade S, Jarlier M, Bibeau F, Chassagne-Clément C, Hennequin C, et al. Predictive factors of positive circumferential resection margin after radiochemotherapy for rectal cancer: the French randomised trial ACCORD12/0405 PRODIGE 2. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(1):82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagtegaal ID, Marijnen CA, Kranenbarg EK, van de Velde CJ, van Krieken JH, Committee PR, et al. Circumferential margin involvement is still an important predictor of local recurrence in rectal carcinoma: not one millimeter but two millimeters is the limit. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(3):350–357. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deijen CL, Velthuis S, Tsai A, Mavroveli S, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Sietses C, et al. COLOR III: a multicentre randomised clinical trial comparing transanal TME versus laparoscopic TME for mid and low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(8):3210–3215. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4615-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Guo H, Guan XD, Cai CN, Yang LK, Li YC, et al. The impact of laparoscopic converted to open colectomy on short-term and oncologic outcomes for colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(2):335–343. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2685-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White I, Greenberg R, Itah R, Inbar R, Schneebaum S, Avital S. Impact of conversion on short and long-term outcome in laparoscopic resection of curable colorectal cancer. JSLS. 2011;15(2):182–187. doi: 10.4293/108680811X13071180406439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allaix ME, Furnée EJ, Mistrangelo M, Arezzo A, Morino M. Conversion of laparoscopic colorectal resection for cancer: what is the impact on short-term outcomes and survival? World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(37):8304–8313. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaw A, Collins EE, Fakis A, Patel P, Semeraro D, Lund JN. Colorectal surgeons and biomedical scientists improve lymph node harvest in colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12(4):295–298. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mekenkamp LJ, van Krieken JH, Marijnen CA, van de Velde CJ, Nagtegaal ID, Investigators PRCatC-oC Lymph node retrieval in rectal cancer is dependent on many factors—the role of the tumor, the patient, the surgeon, the radiotherapist, and the pathologist. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(10):1547–1553. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b2e01f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17(24):2815–2834. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::AID-SIM110>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Etzioni DA, Young-Fadok TM, Cima RR, Wasif N, Madoff RD, Naessens JM, et al. Patient survival after surgical treatment of rectal cancer: impact of surgeon and hospital characteristics. Cancer. 2014;120(16):2472–2481. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aquina CT, Probst CP, Becerra AZ, Iannuzzi JC, Kelly KN, Hensley BJ, et al. High volume improves outcomes: the argument for centralization of rectal cancer surgery. Surgery. 2016;159(3):736–748. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baek JH, Alrubaie A, Guzman EA, Choi SK, Anderson C, Mills S, et al. The association of hospital volume with rectal cancer surgery outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28(2):191–196. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.