SUMMARY

Desensitization of adenosine receptors (ARs) was studied in DDT1 MF-2 cells, which possess both A1- and A2AR, differentially coupled to adenylate cyclase. (−)-N6-(R)-Phenylisopropyladenosine (R-PIA), an A1AR-selective agonist at the appropriate concentrations, desensitized A1AR-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity in a time- (t1/2, 8 hr) and dose-dependent and reversible fashion. This was associated with significant decreases in total A1AR number and in the number of receptors possessing a high affinity for agonist in membrane preparations. The decrease in total A1AR in the membranes from the desensitized cells (~40%) was associated with a 37% increase in A1AR measured in light vesicle preparations, compared with control cells. To test a possible role of phosphorylation in A1AR desensitization, cells were incubated with [32P]orthophosphate, followed by exposure to R-PIA for 18 hr. Subsequent purification of the A1AR indicated a 3–4-fold increase in phosphorylation of A1AR in cells treated with R-PIA, compared with control cells. Desensitization of the A1AR did not alter the levels of αs and α12 proteins or affect the ability of stimulatory effectors, such as isoproterenol, sodium fluoride, and forskolin, to activate adenylate cyclase. These results suggest that uncoupling, downregulation, and phosphorylation of the A1AR contribute, at least in part, to desensitization of this inhibitory receptor. Desensitization of the A2AR was characterized using an A2-selective agonist, 2-[4-(2-{[4-aminopheny1]methylcarbonyl}ethyl)phenyl] ethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (PAPA-APEC). Pretreatment of cells with PAPA-APEC (100 nm) resulted in a rapid loss of agonist stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity (t1/2 of this effect, 45 min). This effect was dose dependent (EC50, ~10 nm) and rapidly reversible. Interestingly, desensitization of the A2AR resulted in no change in receptor number, affinity, or mobility on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Taken together, these data suggest distinct mechanisms of desensitization of A1- and A2ARs in a single cell type.

ARs comprise a group of cell surface receptors that mediate, in part, the physiological effects of adenosine. These receptors are further subdivided into A1 and A2 subtypes, based on the order of potency of various adenosine analogs (1). The coupling of the ARs to adenylate cyclase has been studied extensively (2). In most tissues, A1AR inhibits, whereas A2AR activates, adenylate cyclase. These processes are mediated by the action of ARs on Gi and Gs proteins, respectively, coupled to adenylate cyclase. However, recent studies have shown that A1ARs can also regulate the activity of the voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channel (3), the K+ channel (4), the low-Km cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase (5), guanylate cyclase (6), and phospholipase C (7).

The process of A1AR desensitization has been described previously by work from our laboratory (8, 9) and those of others (10). We have shown that in vivo administration (3–6 days) of the A1AR agonist R-PIA leads to a decrease in A1AR levels in adipocytes, an uncoupling of A1ARs from the Gi proteins, and a heterologous desensitization of receptors coupled to the inhibition of adenylate cyclase (8, 9). Furthermore, there was an augmented response to stimulatory effectors of adenylate cyclase, such as isoproterenol, sodium fluoride, and forskolin. These long term changes were associated with a decrease in the level of the inhibitory Gi proteins and a corresponding increase in the level of the stimulatory Gs protein (8, 9). The in vivo rat adipocyte model, however, limits more detailed characterization of A1AR desensitization. Using rat adipocytes in culture, Green (10) supported these findings concerning A1AR desensitization. However, the level of A1AR measured in these cells was considerably lower than that obtained in freshly prepared rat adipocytes using the identical radioligand (8) or a different radioligand (9, 11), suggesting that adverse biochemical changes might occur after isolation and culturing of adipocytes.

We have recently demonstrated that DDT1 MF-2 smooth muscle cells, derived from hamster ductus deferens, possess high levels of both A1AR and A2AR that are coupled to adenylate cyclase. In this report, we have used these cells to study desensitization of the A1AR and to compare it with the desensitization of the A2AR under identical conditions. Our results show that R-PIA and PAPA-APEC (an A2AR-selective agonist) induce homologous desensitization of the A1AR and the A2AR, respectively. In addition, desensitization of the A1AR was associated with an increased phosphorylation of this receptor subtype.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

Chloramine-T, cAMP, dATP, GTP, ATP, creatinine phosphokinase, HEPES, phosphocreatine, Tris·HCl, isoproterenol, leupeptin, sodium acetate, soybean trypsin inhibitor, pepstatin, benzamidine, PMSF, NaH2PO4, and NaF were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). R-PIA and adenosine deaminase were from Boehringer-Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN). Electrophoresis reagents were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Campbell, CA). DMEM (high glucose), fetal bovine serum, and penicillin-streptomycin were from GIBCO Laboratories, (Grand Island, NY). [3H]XAC (160 Ci/mmol), [α-32P]ATP (30 Ci/mmol), and [γ-32P]ATP were from DuPont-New England Nuclear (Boston, MA). Na125I (carrier free) was from Amersham Corp. (Arlington Heights, IL). All other reagents were of the highest available grade and were purchased from standard sources.

Cell Culture

DDT1MF-2 cells were grown in suspension as previously described (12). Intact cell phosphorylation experiments were performed by first washing cells twice in phosphate-free DMEM and then loading cells for 2 hr with [32P]orthophosphate (0.1 mCi/ml) in this medium, at a concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml. After this, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-free DMEM and resuspended in regular medium (DMEM supplemented with 5% calf serum and 5% fetal bovine serum). Cells were then incubated with or without R-PIA (1 µm) for 18 hr, in the presence of adenosine deaminase (0.3 units/ml).

Membrane Preparation

For 125I-PAPA-APEC and 125I-azidoPAPA-APEC binding, membranes were prepared as previously described (12) and resuspended in 50 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7.2) containing 10 mm MgCl2 (termed 50/10 hereafter) and ~3 units/ml adenosine deaminase. Light vesicles were prepared as previously described (13). Before preparation of the vesicles, cells were first treated with concanavalin A (0.25 mg/ml) for 30 min at 37°, in order to prevent sequestration of the A1AR during the homogenization step.

Membranes used for adenylate cyclase were prepared by centrifuging the Dounce-homogenized cells (as above) at 43,000 × g for 15 min and resuspending the pellet in 75 mm Tris buffer (containing 200 mm NaCl, 12.5 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm dithiothreitol, pH 8.12 at 5°). Membranes were incubated with adenosine deaminase (~3 units/ml) for 15 min at 30°, to eliminate endogenous adenosine, before adenylate cyclase assays were performed. For Western blotting, membranes were obtained from the initial 43,000 × g centrifugation and were solubilized in buffer (10% SDS, 10% glycerol, 20 mm Tris-HCl, 6% β-mercaptoethanol, pH 6.8). This mixture was boiled for 5 min before SDS-PAGE was performed. For A1AR purification and phosphorylation studies, membranes were prepared in lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris·HCl (pH 7.4 at room temperature), 10 µg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 5 µg/ml pepstatin, 50 µm PMSF, 10 µg/ml benzamidine, 5 µg/ml antipain, 10 mm NaF, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mm Na3VO4. All subsequent steps were performed with this buffer containing, in addition, 5 mm EDTA and 125 mm NaCl.

Synthesis of Radioligands

[125I]APNEA and [125I]AZPNEA were synthesized as described previously (14, 15). Radioiodination of PAPA-APEC and the synthesis of 125I-azidoPAPA-APEC were performed as described previously (12, 16).

Radioligand Binding in DDT1 MF2 Cell Membranes

[3H]XAC binding

Membranes (20–40 µg/assay tube) were incubated for 1 hr at 37° with six to eight concentrations of [3H]XAC (0.2–6 nm), in a total volume of 250 µl of 50/10/1 buffer (50 mm Tris·HCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA). This incubation time was optimal to ensure steady state binding, as determined from [3H]XAC association curves (data not shown). Theophylline (10 mm) was used to define nonspecific binding, which normally averaged from 30 to 50% of the total binding. After incubation, membranes were rapidly filtered over 25-mm glass fiber filters (no. 32; Schleicher & Schuell), by vacuum, and were washed three times with 3 ml of ice-cold 50/10/1 buffer containing 0.03% CHAPS. Filters were allowed to extract for at least 12 hr in toluene-based scintillation fluid before counting.

[125I]APNEA binding

Binding experiments were performed, as described above, using 0.2–6 nm [125I]APNEA and ~20–40 µg of membrane protein/assay tube. Incubations were for 1 hr at 37°.

125I-PAPA-APEC binding

Membranes (60–100 µg of protein) were incubated for 1 hr with 125I-PAPA-APEC (0.2–6 nm), in a total volume of 250 µl of 50/10 buffer. Nonspecific binding was defined with 10 mm theophylline and averaged ~50% of total binding at a concentration of the radioligand at the Kd. This concentration of theophylline was optimal and defined a similar level of nonspecific binding as that defined by N-ethylcarboxamide adenosine (100 µm). Separation of the bound radioligands was performed as described above.

Photoaffinity Labeling

[125I]AZPNEA

DDT1 MF-2 cell membranes (~450 µg of protein/ml) from control and R-PIA-treated cells were prepared and photolabeled as previously described (12).

125I-AzidoPAPA-APEC

Labeling of A2AR was performed as previously described (12).

Adenylate Cyclase Assay

Adenylate cyclase activity in DDT1 MF-2 cell membranes (pretreated with adenosine deaminase) was determined as described previously (12, 17).

SDS-PAGE

Electrophoresis was performed according to the method of Laemmli (18), using homogeneous gels, with the stacking gel containing 3% acrylamide and the separating gel 10–15% acrylamide.

Western Blotting

Membrane proteins (40–60 µg) were resolved on a 10% SDS-poly-acrylamide gel, containing 0.13% bisacrylamide, and were then prepared as previously described (9, 19). Antibody AS/7, which recognizes αi1 and αi2 subunits of Gi, and antibody RM/1, which recognizes αs of Gs, were kindly provided by Dr. Allen Spiegel (National Institutes of Health).

Purification of A1AR

A1ARs were partially purified from DDT1 MF-2 cell membranes using a slight modification of the procedure described before (20, 21). These modifications include the use of 25% glycerol and protease inhibitors (10 µg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 5 µg/ml pepstatin, 50 µm PMSF, 10 µg/ml benzamidine, and 5 µg/ml antipain) in the solubilization buffer (50 mm Tris·HCl, 5 mm EDTA, 125 mm NaCl, 1% CHAPS, 0.1% sodium cholate, pH 7.4 at room temperature). Glycerol increased the efficiency of solubilization and the stability of the A1ARs (22). A1ARs from DDT1 MF-2 cells were readily susceptible to degradation after solubilization. In the absence of protease inhibitors, only a 32-kDa protein was observed on SDS-PAGE, without any of the intact (36-kDa) A1AR. By using these protease inhibitors during the membrane preparation and receptor purification steps, this degradation was sufficiently retarded to allow detection of the intact receptor by photoaffinity labeling and iodination (data not shown).

Membranes were solubilized in 50 mm Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4 at room temperature) containing 5 mm EDTA, 125 mm NaCl, 1% CHAPS, 0.1% sodium cholate, 25% glycerol, protease inhibitors (as described above), and phosphatase inhibitors (10 mm sodium fluoride, 1 mm sodium vanadate, and 10 mm sodium phosphate), with a CHAPS to protein ratio of 2.5:1. Solubilization of membrane proteins was effected by sonication for ~100 sec on ice (setting 12, VirSonic 50 sonicator; Virtis). This mixture was centrifuged at 105,000 × g for 45 min, and the supernatant (soluble preparation) was saved and diluted with a 4-fold excess buffer (without CHAPS, cholate, or glycerol), in order to reduce the CHAPS and glycerol concentrations to 0.25% and 6%, respectively. Adenosine deaminase (~0.5 units/ml) was added to the diluted soluble preparation, and this was incubated at room temperature for 15 min before XAC affinity chromatography was performed.

Affinity chromatography was performed by pumping the soluble preparation through the XAC-Affigel at a rate of 8 ml/hr at 4°. This rate ensured recycling of the entire soluble preparation through the Affigel approximately three times. The Affigel was then washed (at 4°) with 6 volumes of 50 mm Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4 at 5°) containing 5 mm EDTA, 125 mm NaCl, 0.25% CHAPS, 6% glycerol, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors (as described above), and this was followed by washing (at room temperature) with 3 volumes of a phospholipid buffer (25 mm Tris·HC1, pH 7.4 at room temperature, 6 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 125 mm NaCl, 15 mm HEPES, 0.05% l-α-phosphatidylcholine, 0.33% CHAPS, 5% glycerol) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (see above). A1ARs bound to the XAC-Affigel were eluted (at room temperature) in 7 ml of the aforementioned phospholipid buffer, containing 5 mm theophylline. Elution was performed by equilibrating the Affigel column with the buffer (by rotation) for 45 min and then pumping the buffer through at a rate of approximately 10 ml/hr. This protocol enabled purification of the A1AR from DDT1 MF-2 cell membranes by 150–300-fold, as assessed by radioligand binding using [3H]XAC. The eluate from the XAC-Affigel was then applied to a 0.4-ml hydroxylapatite column at a flow rate of 15 ml/hr. The column was then washed with about 3 ml of buffer (50 mm Tris, containing 1 mm EDTA, 125 mm NaCl, protease and phosphatase inhibitors as described above, and 0.05% CHAPS, pH 7.4), and this was followed by 2 ml of buffer with 50 mm KH2PO4. Purified A1ARs were eluted from hydroxylapatite columns using buffer (as above) containing 400 mm KH2PO4.

Data Analysis and Protein Determination

Saturation curves were analyzed by a computer-assisted curve-fitting program (23, 24) equipped with a statistical package. Other statistical analyses were performed using the Student’s t test (two-tailed) with an α probability of 0.05. Error bars shown in the text and in the figures are standard errors. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (25), using bovine serum albumin as standard.

Results

Desensitization of A1AR-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase by R-PIA

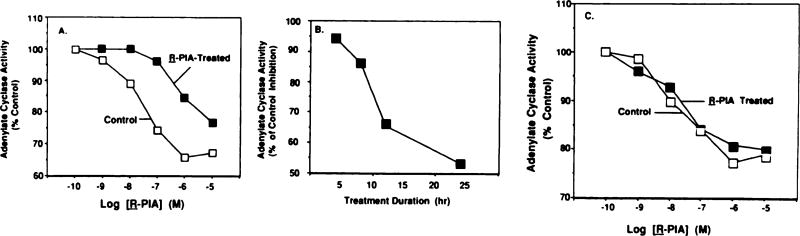

R-PIA produced a dose-dependent inhibition of isoproterenol-stimulated adenylate cyclase activity in membranes prepared from control cells, which was maximal (29.0 ± 2.8% inhibition; five experiments) at 1 µm R-PIA. The IC50 of R-PIA in control membranes averaged 46 ± 2.9 nm. Cells previously treated with R-PIA (1 µm) for 24 hr demonstrated a considerably reduced response to subsequent administration of this agonist. For example, inhibition of isoproterenol-stimulated adenylate cyclase by 1 µm R-PIA (Fig. 1A) was reduced to 15.4 ± 3.2% (five experiments). This attenuated response is not likely due to R-PIA being retained in the membranes after the washing procedure, because incubation with this agonist for a shorter period (e.g., 4 hr) did not result in any significant desensitization of the A1AR (Fig. 1, B and C). Furthermore, the IC50 of R-PIA was shifted to about a 20-fold higher concentration after R-PIA treatment, compared with control.

Fig. 1.

Desensitization of A1AR-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity. A, DDT1 MF-2 cells were treated without (control) or with R-PIA (1 µm) for 24 hr, in the presence of adenosine deaminase. Adenylate cyclase assays were performed as described in Experimental Procedures. This experiment is representative of five experiments showing similar results. B, Time course of desensitization of A1AR. Inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity produced by R-PIA (1 µm) in control versus treated cells was determined at various times during drug treatment. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of three independent experiments at each time point. C, Full R-PIA inhibition curves in control cells and those treated for 4 hr. Data presented are the mean of two experiments.

For all subsequent experiments, 1 µm R-PIA was used to assess A1AR desensitization. Desensitization of the A1AR response was time dependent (Fig. 1B). The attenuation of R-PIA inhibition of adenylate cyclase was only slight at 4 hr but was reduced to ~53% of the control level by 24 hr. Almost full recovery of the inhibitory response was observed by 24 hr after termination of R-PIA treatment. In order to ensure that there were no subtle changes in A1AR inhibitory response after a 4-hr treatment period that were not detectable using a single concentration of R-PIA (1 µm), full inhibition curves were performed at this time point (Fig. 1C). As can be seen, no significant changes in inhibition of adenylate cyclase were observed between the control and treated groups. Desensitization of the A1AR was dependent on the R-PIA concentration used during the incubation period. The inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity was reduced by 11.6%, 50.2%, and 51.7% after treatment of cells with 10, 100, and 1000 nm R-PIA, respectively.

To determine whether desensitization induced by R-PIA was homologous or heterologous, we tested the ability of carbachol (a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor agonist) to inhibit adenylate cyclase in membranes of control cells and cells previously treated with R-PIA. The existence in vas deferens of muscarinic receptors that produce contraction has been described (26, 27). Furthermore, we have detected a low density of muscarinic receptors (approximately 5 fmol/mg of protein) in these cells using the antagonist radioligand N-[3H]methylscopolamine (3 nm). Carbachol (1 mm) inhibited adenylate cyclase activity by 15.9 ± 1.8% (five experiments) in control membranes, whereas inhibition in the treated membranes was slightly but not significantly reduced (p > 0.05), to 10.9 ± 3.4% (five experiments). Thus, R-PIA treatment for 24 hr resulted in homologous desensitization of the A1AR in DDT1 MF-2 cells. However, it is entirely possible that R-PIA treatment for longer periods (>24 hr) might result in heterologous desensitization of A1AR.

Next, the ability of stimulatory effectors (isoproterenol, sodium fluoride, and forskolin) to activate adenylate cyclase activity after desensitization was examined. These experiments were prompted by the previous finding, in intact animals, that A1AR desensitization was associated with an increase in the quantity and activity of the Gs protein. Table 1 shows that the abilities of both isoproterenol and sodium fluoride to stimulate adenylate cyclase activity were not significantly different in control and R-PIA-treated cells. In addition, forskolin-stimulated adenylate cyclase activity was similar in control and treated cells (see legend to Table 1). These data suggest that the levels and activities of Gs and the catalytic subunit were unaltered after desensitization. However, the ability of the selective A2 receptor agonist PAPA-APEC (12, 16) to activate adenylate cyclase was profoundly diminished after exposure to R-PIA (Table 1), suggesting that this agonist desensitizes both A1- and A2AR subtypes. This finding is not surprising, in view of the fact that at 1 µm R-PIA can interact with both A1- and A2ARs (12).

TABLE 1. Fold stimulation by effectors of adenylate cyclase activity in control and R-PIA-treated membranes.

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (four experiments) of fold stimulation over basal. Basal adenylate cyclase activity was 3.0 ± 0.8 pmol/min/mg of protein and 3.7 ± 1.7 pmol/min/mg of protein for control and R-PIA-treated (24 hr, 1 µm) membranes, respectively. Fold stimulation by forskolin (10 µm) was 11.0 and 9.6 for control and treated membranes, respectively (two experiments).

| Stimulation

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Control | Treated | |

|

| ||

| Fold | ||

| Isoproterenol (10 µm) | 9.2 ± 1.7 | 9.4 ± 1.8 |

| NaF (10 mm) | 7.2 ± 1.2 | 6.8 ± 1.3 |

| PAPA-APEC (1 µm) | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.2a |

Statistically significantly different from control (p < 0.05).

Association of desensitization of A1AR response with a decrease in membrane A1AR and an increase in light vesicle A1AR

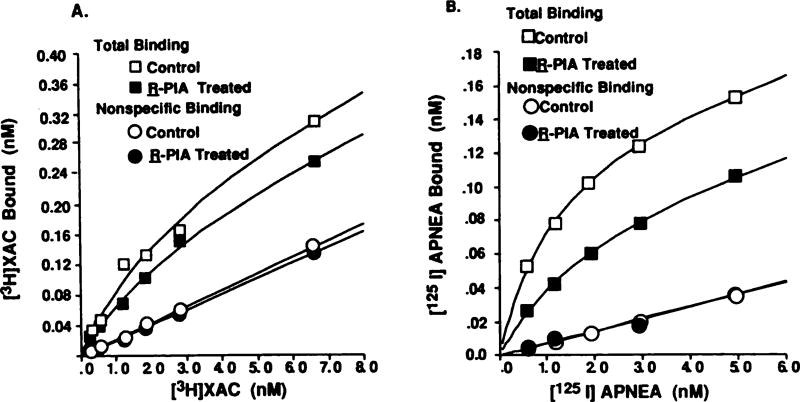

To test whether the desensitization of the A1AR-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase was due to a loss of A1AR, receptor levels were quantitated in membranes from control and treated cells, using the antagonist radioligand [3H]XAC. Fig. 2A shows that both A1AR number and affinity were altered after R-PIA treatment. The maximum number of binding sites (Bmax) estimated was 1.35 ± 0.13 pmol/mg of protein and 0.81 ± 0.02 pmol/mg of protein for control and desensitized cell membranes, respectively. A 2-fold decrease in Kd was also observed in the treated cells (Table 2). This significant decrease in the Kd for [3H]XAC probably reflects a partial uncoupling of the A1AR from its G protein(s) after desensitization. A similar increase in the antagonist binding affinity has been observed after the uncoupling of A1ARs from their G proteins in the presence of guanine nucleotides (11). This loss of receptors was time dependent, with maximal loss (~40%) occurring by 12 hr (Table 3). No further loss of A1AR was observed on increasing the treatment duration to 24 hr. Receptors recovered to control levels 20 hr after termination of R-PIA treatment. Using an agonist radioligand, [125I]APNEA, a 38% loss in agonist binding was observed. This suggests that R-PIA administration resulted in a reduction in total receptor number and a decrease in the number of A1ARs coupled to their G protein(s) (Fig. 2B). This can be further documented using an agonist photoaffinity probe, as demonstrated in Fig. 3, where the quantity of photoaffinity-labeled receptor was decreased to 30 ± 9% of control. In order to better assess receptor uncoupling during the desensitization process, agonist competition curves were performed using the antagonist radioligand [3H]XAC in control and R-PIA-treated membrane preparations. The results shown in Table 4 indicate a significant decrease in the percentage of RH in the treated versus control membranes, indicative of a partial uncoupling of the A1AR from G protein(s).

Fig. 2.

Quantitation of A1ARs in membranes prepared from control and R-PIA (1 µm, 24 hr)-treated cells, using the selective antagonist radioligand [3H]XAC (A) or selective agonist radioligand [125I]APNEA (B). Saturation curves were fitted by computer modeling, according to a one-state fit (19, 20). These curves are representative of five (A) or three (B) independent experiments.

TABLE 2. Effect of 24-hr R-PIA (1 µm) treatment on A1AR in DDT1 MF-2 cell membranes.

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error.

| Radioligand | Control | R-PIA-Treated | na |

|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]XAC | |||

| Bmax (pmol/mg of protein) | 1.35 ± 0.13 | 0.81 ± 0.02b | 5 |

| Kd (nm) | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.2b | 5 |

| [125I]APNEA | |||

| Bmax (pmol/mg of protein) | 0.84 ± 0.62 | 0.52 ± 0.06b | 3 |

| Kd (nm) | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 3 |

n, number of individual experiments performed in control and treated cells.

Statistically significantly different from control (p < 0.05).

TABLE 3. Time course of loss of A1AR after R-PIA (1 µm) treatment.

| Duration | Bmax | na |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| hr | % of control | |

| Treatment | ||

| 4 | 78 ± 16 | 6 |

| 8 | 82 ± 5b | 4 |

| 12 | 59 ± 4b | 4 |

| 24 | 66 ± 6b | 6 |

| Recovery | ||

| 20 | 96 | 2 |

n, number of individual experiments performed in control and treated cells.

Statistically significantly different from control (p < 0.05).

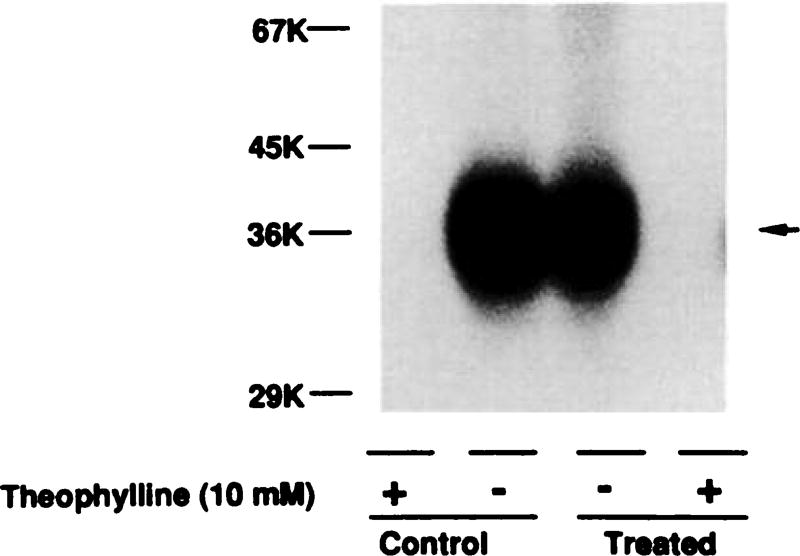

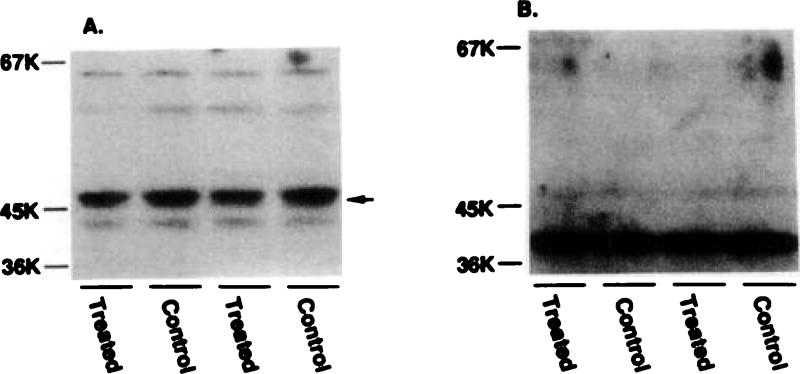

Fig. 3.

Photoaffinity labeling of A1AR using [125I]AZPNEA. Membranes from control cells and cells treated with R-PIA (1 µm) for 24 hr were photolabeled with [125I]AZPNEA and subjected to SDS-PAGE, as described in Experimental Procedures. In order to test whether the migration of A1AR from treated cells was altered, a 50% increase in membrane proteins was added to the treated lanes. This is a representative figure of three independent experiments. After densitometric scanning of the autoradiograph and normalization for the different amounts of protein loaded per lane, incorporation of [125I]AZPNEA in the treated membranes was 40% of control. The average incorporation of [125I]AZPNEA into the desensitized membranes was 30 ± 9% of control (three experiments). Molecular weights of iodinated standards are indicated on the left.

TABLE 4. Effect of R-PIA (1 µm) treatment on R-PIA competition curves.

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of three experiments, using [3H]XAC as the antagonist radioligand, at a concentration of 2.5 nm. KH and KL are the equilibration dissociation constants of the high and low affinity states, respectively. RH is the percentage of receptors in the high affinity state.

| Binding parameters | Control | R-PIA-Treated |

|---|---|---|

| KH (nm) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 1.3 |

| KL (nm) | 228.7 ± 59.8 | 212.7 ± 105.0 |

| RH (%) | 60.3 ± 0.3 | 46.7 ± 4.5a |

Statistically significantly different from control (p < 0.05).

Quantitation of membrane and light vesicle A1ARs after exposure of DDT1 MF-2 cells to R-PIA demonstrated an increase in A1AR number in light vesicle preparations from desensitized cells. The increase in light vesicle A1AR averaged 37.2 ± 8.4%, compared with a 32.5 ± 6.2% loss in membrane receptors in these cells (receptor levels determined by [3H]XAC binding), measured simultaneously. However, the total number of receptors recovered in the light vesicles could only account for about 5–10% of the A1ARs no longer detectable in the membranes. This suggests that a great majority of A1ARs might be sequestered elsewhere and/or degraded during the course of R-PIA treatment.

Association of phosphorylation of A1AR with A1AR desensitization

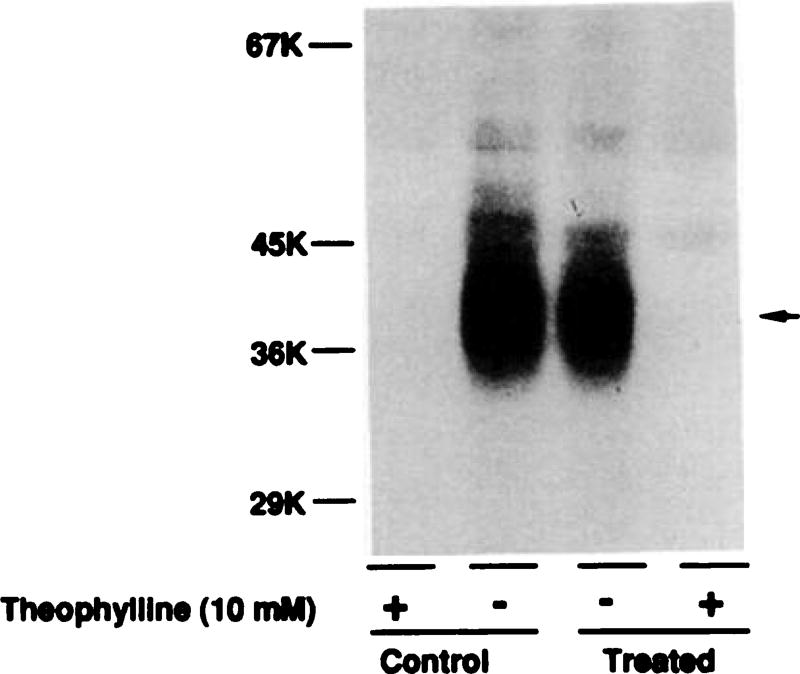

In order to test whether desensitization of the A1AR was associated with receptor phosphorylation, cells were loaded with [32P]orthophosphate and then treated with or without R-PIA for 18 hr. A1ARs were then partially purified from these cells by XAC affinity chromatography, followed by hydroxylapatite chromotography. Initial experiments suggested that A1AR from control and desensitized cells could be purified by XAC-Affigel and by hydroxylapatite chromatography with equal efficiency. Fig. 4 shows that phosphorylation of the A1AR (36 kDa) was greater in cells treated with R-PIA. Similar findings were observed in four additional experiments. R-PIA treatment increased A1AR phosphorylation by about 3–4-fold over control (determined by excising and counting the dried gel). In addition to the 36-kDa protein, R-PIA also enhanced the phosphorylation of a 32-kDa protein. The identity of the 32-kDa protein cannot at present be proven, but we believe it is likely an A1AR fragment that was cleaved from the intact receptor during the purification steps. The finding that its phosphorylation was enhanced by the agonist would support this.

Fig. 4.

Phosphorylation of A1AR in DDT1 MF-2 cells after R-PIA treatment. DDT1 MF-2 cells were incubated with [32P]orthophosphate for 2 hr at 37°, in phosphate-free DMEM. Cells were washed twice and then finally resuspended in DMEM containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 5% calf serum, with or without R-PIA (1 µm). After agonist treatment for 18 hr, cells were solubilized and A1ARs were purified by XAC-Affigel chromatography, followed by hydroxylapatite chromatography. The purified A1AR was resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE. Approximately 70 fmol of A1AR was loaded in the control lane and 40 fmol of A1AR in the R-PIA-treated lane.

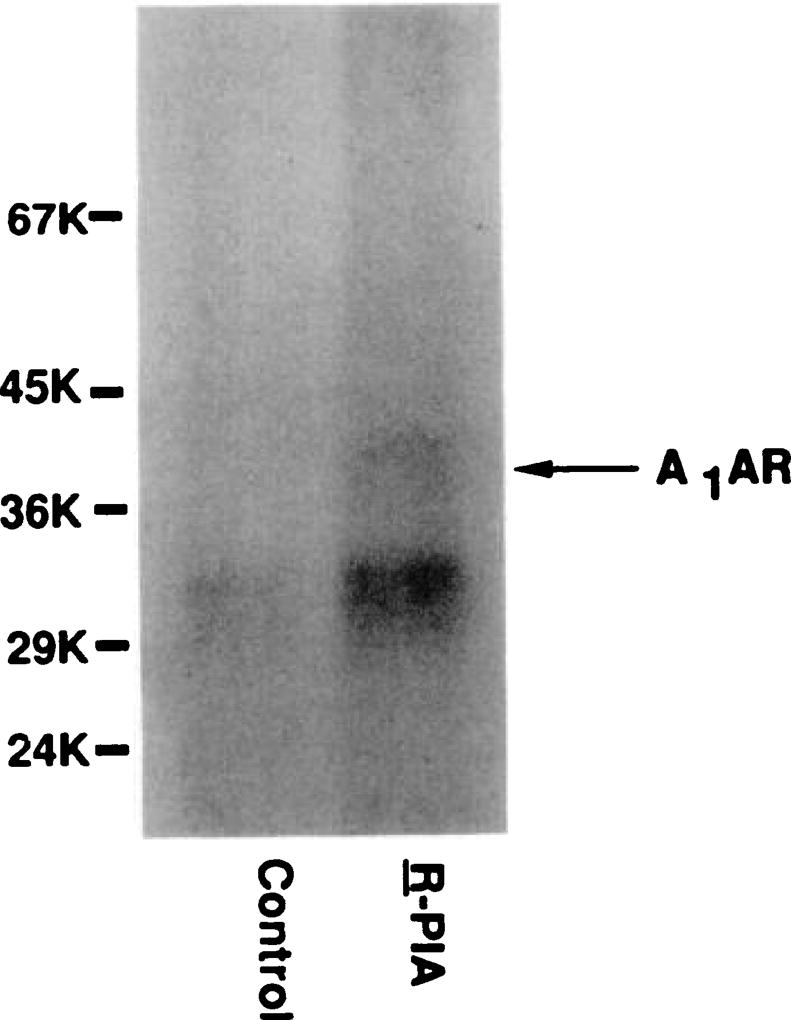

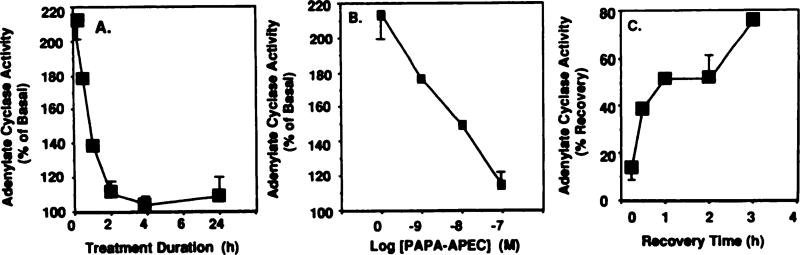

Western blots of Gα proteins in control and R-PIA-desensitized membranes

Desensitization of A1AR after long term agonist treatment both in vivo (8, 9) and in vitro (10) was associated with the regulation of G protein α subunits. In order to test whether changes in the α subunits of the Gs and Gi proteins occurred, cells were exposed to R-PIA for 24 hr, and membranes were assessed with specific antibodies, using Western blotting technique. These cells do not possess detectable levels of the αi1 or αi3 transcripts, as determined by Northern analysis, but possess high levels of the αi2 transcript. Northern blots containing 4 µg of poly(A)+ RNA were used in these studies. Therefore, the single band (40 kDa) on the Western blots recognized by AS/7 is likely the αi2 protein. Fig. 5 shows that the level of this protein was relatively unchanged at a time when A1- and A2ARs were desensitized. The levels of αi2 and αs quantitated by excising and counting the labeled bands were 94 ± 12% (six experiments) and 87 ± 6% (six experiments) of control, respectively. Thus, it appears likely that desensitization of the A1AR is not due to any change in the level of the αi2 protein but an uncoupling of the receptor from this G protein.

Fig. 5.

Quantitation of αi and αs proteins by Western blotting in control and R-PIA-treated cell membranes. A, Membranes (~60 µg/lane) were solubilized and resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, as described previously (9, 19). Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose filters and were probed with antibody AS/7 (1/500 dilution), followed by 125IProtein A (300,000 cpm/ml). B, Filters were probed with the αs-specific antibody RM/1 (1/500 dilution).

Desensitization of the A2AR-mediated stimulation of adenylate cyclase

Because R-PIA treatment could desensitize both A1- and A2ARs (see Table 1), it was of interest to study the desensitization of A2AR in these cells using a selective A2 agonist. Desensitization of A2AR has not been characterized in detail before this study, owing to a lack of selective radioactive probes for this receptor. For these experiments, we used PAPA-APEC, which has been shown previously to bind to A2AR and selectively activate adenylate cyclase in DDT1 MF-2 cell membranes (12).

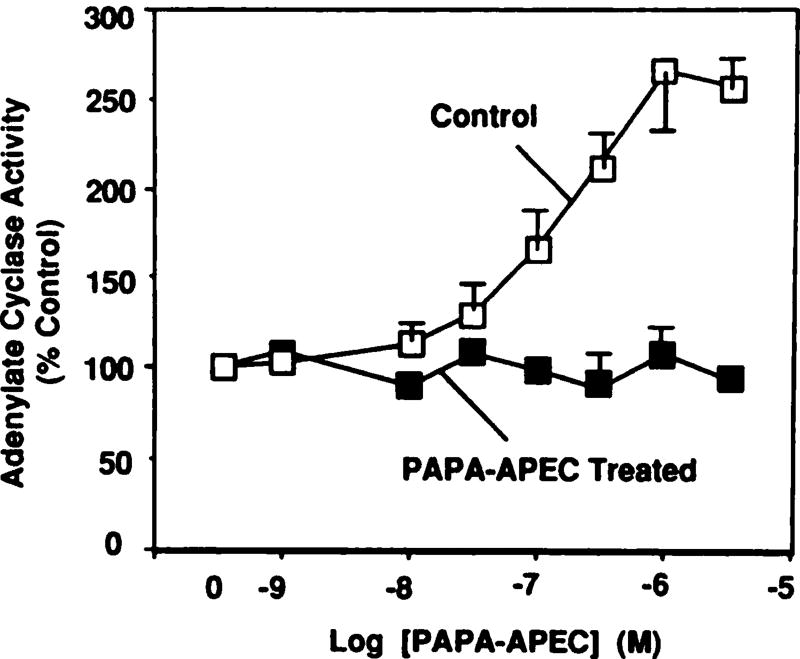

Treatment with PAPA-APEC (100 nm) for 24 hr resulted in a complete loss of the ability of subsequent agonist administration to activate adenylate cyclase (Fig. 6). The loss of the stimulatory action of PAPA-APEC was rapid and was almost complete by 4 hr (Fig. 7A). The t1/2 of A2AR desensitization produced by 100 nm PAPA-APEC was ~45 min. Desensitization of the A2AR response was also dose dependent. The EC50 of PAPA-APEC for inducing desensitization was ~3 nm (Fig. 7B). Recovery from desensitization (after a 4-hr treatment with 100 nm PAPA-APEC) was also rapid, as shown in Fig. 7C. The biphasic nature of the recovery suggests that it might involve multiple processes. It should be noted that PAPA-APEC (100 nm) treatment for 24 hr did not produce any diminution of A1AR-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase, suggesting that desensitization was specific for the A2AR. This is consistent with the fact that PAPA-APEC is at least 500-fold selective for the A2AR over A1AR (12, 16). Therefore, this agonist has the advantage of producing selective A2AR desensitization and allows for interpretation of the present data in the absence of simultaneous desensitization of A1AR.

Fig. 6.

Desensitization of A2AR-mediated activation of adenylate cyclase. Cells were treated with vehicle (control) or with PAPA-APEC (100 nm) for 24 hr, in the presence of adenosine deaminase (0.3 units/ml). Adenylate cyclase activity was assayed as described in Experimental Procedures. Basal activity in control and PAPA-APEC-treated cells averaged 2.2 ± 0.6 and 2.9 ± 1.3 pmol/min/mg of protein, respectively. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of five independent experiments.

Fig. 7.

Desensitization of A2ARs by PAPA-APEC. A, DDT1 MF-2 smooth muscle cells were treated for various time periods with PAPA-APEC (100 nm). Basal adenylate cyclase activity averaged 2.0 pmol/min/mg of protein. PAPA-APEC (1 µm) was used to assess the extent of desensitization. B, Dose dependency of PAPA-APEC-mediated desensitization of activation of adenylate cyclase. Cells were treated with different concentrations of PAPA-APEC (1–100 nm) for 4 hr. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of two to four experiments. C, Time course of recovery from desensitization. Cells were treated with PAPA-APEC (100 nm) for 3 hr, after which they were washed and resuspended in fresh DMEM containing 5% serum and 0.3 units/ml adenosine deaminase. Data presented are the mean ± standard error of two or three independent experiments.

In order to determine whether desensitization of the A2AR is homologous or heterologous, the ability of isoproterenol to stimulate adenylate cyclase activity in control and PAPA-APEC-desensitized cells was tested. Table 5 shows that, whereas stimulation produced by PAPA-APEC was effectively abolished in desensitized membranes, that produced by isoproterenol was unchanged. These data suggest that desensitization of A2AR induced by PAPA-APEC is homologous. In addition, the lack of desensitization to isoproterenol suggests that both the Gs protein and the catalytic subunit of adenylate cyclase were intact after A2AR desensitization.

TABLE 5. Fold stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity in control and PAPA-APEC-treated membranes.

Cells were treated with PAPA-APEC (100 nm) for 24 hr in the presence of adenosine deaminase. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of fold stimulation over basal adenylate cyclase activity (seven experiments).

| Stimulatory effectors | Stimulation

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Control | PAPA-APEC-Treated | |

|

| ||

| Fold | ||

| PAPA-APEC (1 µm) | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1a |

| Isoproterenol (10 µm) | 12.6 ± 1.3 | 12.6 ± 1.1 |

Statistically significantly different from control (p < 0.05).

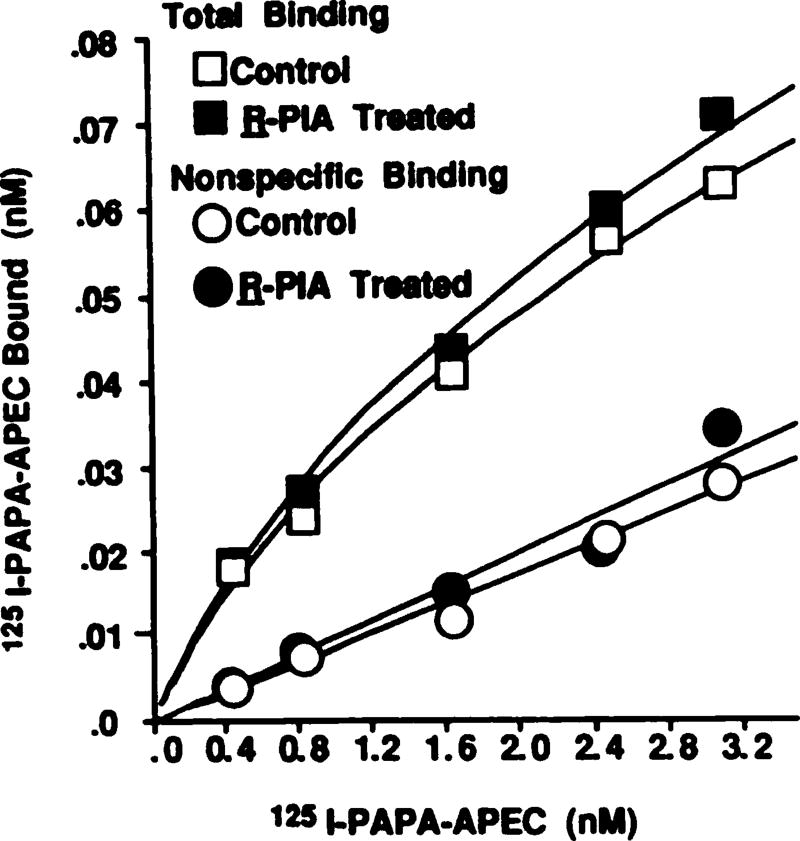

Quantitation of A2AR in control and desensitized DDT1 MF-2 cells

To determine whether a loss or uncoupling of A2AR was responsible for the PAPA-APEC-induced desensitization of the A2AR response, receptors were quantitated using a selective agonist radioligand, 125I-PAPA-APEC (12, 16). Being an agonist, this radioligand should selectively label the high affinity, “coupled” state of the A2AR. To date, no selective A2AR antagonist radioligand is available. Binding of this radioligand to the A2AR was saturable and of high affinity (Fig. 8). Bmax values were relatively unchanged, being 209 ± 29 and 195 ± 18 fmol/mg of protein in control and PAPA-APEC-treated cells, respectively. No significant change in the equilibrium dissociation constants (1.3 ± 0.1 versus 1.0 ± 0.2 nm for control and PAPA-APEC-treated preparations, respectively) were observed. Thus, desensitization of the A2AR activation of adenylate cyclase occurred without a significant loss in the population of receptors that are coupled to the Gs protein.

Fig. 8.

Quantitation of A2ARs using 125I-PAPA-APEC, in membranes from control and PAPA-APEC-treated cells. Cells were treated with PAPA-APEC (100 nm) for 24 hr at 37°. Saturation curves were performed using 125I-PAPA-APEC, as described in Experimental Procedures. Curves were fitted by a computer-assisted program (23, 24), assuming a one-state model. This is representative of five independent experiments showing similar results.

Photoaffinity labeling of A2AR in control and desensitized cells

A2ARs in DDT1 MF-2 cells were labeled by the agonist photoaffinity probe 125I-azidoPAPA-APEC, as described previously (12). After PAPA-APEC-induced desensitization, no significant change in the quantity or the migration of the photolabeled receptor was detected on SDS-PAGE, in accordance with the radioligand binding data (Fig. 9). Furthermore, peptide mapping of the A2AR (using Staphylococcus aureus V8 protease) from control and PAPA-APEC-treated cells showed identical peptide maps (data not shown). These data suggest that no gross alteration in A2AR structure occurred after desensitization.

Fig. 9.

Photoaffinity labeling of A2AR in membranes prepared from control cells and cells treated with PAPA-APEC (100 nm) for 24 hr. Membranes were labeled with the A2AR-selective photoaffinity probe 125I-azidoPAPA-APEC (0.8 nm), as described in Experimental Procedures. Lanes 1 and 2, control membranes in the presence (lane 1) and absence (lane 2) of theophylline (10 mm) during the binding experiment; lanes 3 and 4, treated membranes in the absence (lane 3) and presence (lane 4) of theophylline. Specific 125I-azidoPAPA-APEC counts incorporated in lanes 2 and 3 were 1021 cpm and 1018 cpm, respectively. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

Discussion

This study provides multiple new insights into the process of desensitization of adenosine receptors. First, it demonstrates that both A1- and A2ARs in a single cell can be desensitized by the same ligand (R-PIA, 1 µm) or can be differentially desensitized by PAPA-APEC (A2AR only). Second, the A1AR is phosphorylated during the desensitization process. Third, the time courses for desensitization for the two receptors are quite different, with t1/2 of 45 min for A2AR and ~8 hr for A1AR. Fourth, the A1AR appears to down-regulate (internalize) and uncouple from G proteins, whereas the A2AR does neither.

The decrease in A1AR number is directly paralleled by a loss in A1AR-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase, suggesting that the loss in A1AR may be, at least partially, the mechanism for desensitization. The mechanisms responsible for downregulation remain unclear. Evidence provided in this report suggests an increased internalization of A1AR consequent to agonist exposure. However, because the level of receptor measured in the light vesicles was considerably less than the total receptor loss from the membrane, it is possible that additional receptors were sequestered in a membrane compartment or were degraded in the cytosol.

Phosphorylation of the A1AR occurred after R-PIA treatment of DDT1 MF-2 cells. This modification of the A1AR could account, at least in part, for the attenuated inhibition of adenylate cyclase. Evidence for a role of receptor phosphorylation in the desensitization of the α1-adrenergic (28), muscarinic (29), and β-adrenergic receptors has been reported previously (30). It is not yet clear whether phosphorylation of the A1AR alters its interaction with Gi (leading to uncoupling) or whether this modification enhances its internalization and possibly its degradation.

Unlike the in vivo desensitization model (8, 9), changes in the levels of Giα proteins do not occur after homologous desensitization of A1AR in DDT1 MF-2 cells. Western blot analysis showed no change in the quantity of the αi2 protein in desensitized cells, compared with control cells. This difference might be due to the duration of R-PIA treatment (usually 6 days in intact animals), to tissue differences (adipocytes versus smooth muscle cells), or to alterations in the neurohormonal axis in the intact animal.

Desensitization of A2AR was extremely rapid. Complete desensitization of the stimulatory response was observed after a 4-hr exposure to the agonist. The rapid time course of desensitization is in agreement with that observed in NG108-15 cells after the administration of 2-chloroadenosine (31) and contrasts with the slower progression of A1AR desensitization. These data suggest distinct mechanisms underlying desensitization of A1- and A2ARs. Other receptor systems coupled to the activation of adenylate cyclase, such as the β-adrenergic receptors, have similarly been shown to desensitize rapidly (32–34).

The number of A2ARs remained unchanged in the desensitized cells. Furthermore, because an agonist ligand was used to quantitate these receptors, it also is unlikely that a loss in the agonist-promoted high affinity state of the receptor could account for desensitization. These findings are of interest in light of previous evidence showing tight coupling of the A2AR to adenylate cyclase (35). Evidence from our laboratory also suggests tight coupling of the A2AR-G protein complex, because guanine nucleotides do not regulate the binding of an agonist radioligand to this receptor in DDT1 MF-2 cell membranes1 and bovine striatal membranes (16). We propose, therefore, that the tight interaction between the A2AR and its G protein might diminish its ability to uncouple or be internalized upon prolonged exposure to a stimulatory agonist. Labeling of A2AR with the receptor-selective photoprobe and separation of the labeled species on SDS-PAGE indicated that receptors from both the control and treated groups were of similar intensity and migrated with a molecular mass of 40–42 kDa. These data suggest (although they do not necessarily prove) that the “desensitized” receptor might not be structurally altered. In addition, peptide mapping of labeled A2AR from control and PAPA-APEC-desensitized cell membranes indicates very similar peptide fragments (data not shown), further underscoring the idea that the receptor was not modified by desensitization. Future experiments in other tissues or in different cell lines known to contain adenosine receptors, such as WI-38 fibroblasts (36), will be needed to determine whether these changes are common to all A2ARs or limited to A2ARs in DDT1 MF-2 cells.

In summary, we have demonstrated desensitization of both A1- and A2ARs in DDT1 MF-2 clonal cells. Although both of these receptors are targets of adenosine in vivo, they are structurally and functionally different, in terms of their responses to prolonged agonist challenge. We believe that the use of such a cell culture model will facilitate our understanding of these varied processes involved in the desensitization of adenosine receptors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Linda Scherich for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

V.R. was supported by a National Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellowship (1F32-HL-07888-01), from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, during the course of this study. G.L.S. was supported by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute SCOR Grant (P50HL17670) in Ischemic Disease, in part by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant (RO1HL35134) and Supplement, and by a Grant-in-Aid (880662) from the American Heart Association and 3M Riker.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AR

adenosine receptor

- APNEA

N6-2-(4-amino-3-iodophenyl)ethyladenosine

- AZPNEA

N6-2-(4-azido-3-iodophenyl)ethyladenosine

- XAC

8-{4-[{{[2-aminoethylamino]carbonyl}methyl}oxyl]phenyl}-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- PAPA-APEC

2-[4-(2-{[4-aminophenyl]methylcar-bonyl}ethyl)phenyl]ethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propansulfonate

- A1AR

A1 adenosine receptor

- A2AR

A2 adenosine receptor

- G protein

guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein

- R-PIA

(−)-N6-(R)-phenylisopropyladenosine

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

Footnotes

V. Ramkumar and G. L. Stiles, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Van Calker D, Muller M, Hamprecht B. Adenosine regulates via two different receptors the accumulation of cyclic AMP in cultured brain cells. J. Neurochem. 1979;33:999–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb05236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiles GL. Adenosine receptors and beyond: molecular mechanisms of physiological regulation. Clin. Res. 1990;38:10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperelakis N. Regulation of calcium slow channels of cardiac and smooth muscles by adenine nucleotides. In: Pelleg A, Michelson EL, Freifus LS, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology and Pharmacology of Adenosine and ATP: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Alan R. Liss, Inc.; New York: 1987. pp. 135–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurachi Y, Nakajima T, Sugimoto T. On the mechanism of activation of muscarinic K+ channels by adenosine in isolated atrial cells: involvement of GTP-binding proteins. Pfluegers Arch. 1986;407:264–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00585301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMazancourt P, Guidicelli Y. Guanine nucleotides and adenosine “Ri”-site analogues stimulate the membrane bound low Km cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase of rat adipocytes. FEBS Lett. 1984;173:385–388. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurtz A. Adenosine stimulates guanylate cyclase activity in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:6296–6300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delahaunty TM, Cronin MJ, Linden J. Regulation of GH3-cell function via A1 receptors. Biochem. J. 1988;255:69–77. doi: 10.1042/bj2550069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsons WJ, Stiles GL. Heterologous desensitization of the inhibitory A1 adenosine receptor-adenylate cyclase system in rat adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longabaugh JP, Didsbury J, Spiegel A, Stiles GL. Modification of rat adipocyte A1 adenosine receptor-adenylate cyclase system during chronic exposure to an A1 adenosine receptor agonist: alterations in the quantity of Gsα and Giα are not associated with changes in their mRNAs. Mol. Pharmacol. 1989;36:681–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green A. Adenosine receptor down-regulation and insulin resistance following prolonged incubation of adipocytes with an A1 adenosine receptor agonist. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:15702–15707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramkumar V, Stiles GL. Reciprocal modulation of agonist and antagonist binding to A1 adenosine receptors by guanine nucleotides is mediated via a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;246:1194–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramkumar V, Barrington WW, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Demonstration of both A1 and A2 adenosine receptors in DDT1 MF-2 smooth muscle cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1990;37:149–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sibley DR, Strasser RH, Benovic JL, Daniel K, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of the beta-adrenergic receptor regulates its functional coupling to adenylate cyclase and subcellular distribution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:9408–9412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stiles GL, Daly DT, Olsson RA. The A1 adenosine receptor: identification of the binding subunit by photoaffinity cross-linking. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:10806–10811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stiles GL, Daly DT, Olsson RA. Characterization of the A1 adenosine receptor-adenylate cyclase system of rat cerebral cortex using an agonist photoaffinity ligand. J. Neurochem. 1986;47:1020–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrington WW, Jacobson KA, Hutchison AJ, Williams M, Stiles GL. Identification of the A2 adenosine receptor binding subunit by photoaffinity crosslinking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:6572–6576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salomon Y, Londos C, Rodbell M. A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Anal. Biochem. 1974;58:541–548. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (Lond.) 1970;227:680–683. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramkumar V, Stiles GL. In vivo pertussis toxin and administration: effects on the function and levels of Giα, proteins and their messenger ribonucleic acid. Endocrinology. 1990;126:1295–1304. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-2-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olah ME, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. Purification and characterization of bovine cerebral cortex A1 adenosine receptor. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990;283:440–446. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90665-l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakata H. Purification of A1 adenosine receptor from rat brain membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:16545–16551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wikberg JES, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Solubilization of rat liver alpha1-adrenergic receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1983;32:3171–3178. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeLean A, Hancock AA, Lefkowitz RJ. Validation and statistical analysis of a computer modeling method for quantitative analysis of radioligand binding data for mixtures of pharmacological receptor subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1982;21:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hancock AA, DeLean A, Lefkowitz RJ. Quantitative resolution of beta-adrenergic subtypes by selective ligand binding: application of a computerized model folding technique. Mol. Pharmacol. 1979;16:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higuchi H, Takeyasu K, Uchida S, Yoshida H. Mechanism of agonist-induced degradation of muscarinic cholinergic receptor in cultured vas deferens of guinea pig. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1982;79:67–77. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90576-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manfrid E. Muscarinic M1- and M2-receptors mediating opposite effects on neuromuscular transmission in rabbit vas deferens. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;151:205–221. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leeb-Lundberg LMF, Coteachia S, DeBlasi A, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of adrenergic receptor function by phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:3098–3105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwatra MM, Benovic JL, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Hosey MM. Phosphorylation of chick heart muscarinic cholinergic receptors by the β-adrenergic receptor kinase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4543–4547. doi: 10.1021/bi00437a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouvier M, Leeb-Lundberg LMF, Benovic JL, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of adrenergic receptor by phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:3106–3113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kenimer JG, Nirenberg M. Desensitization of adenylate cyclase to prostaglandin E1 or 2-chloroadenosine. Mol. Pharmacol. 1981;20:585–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strasser RH, Benovic JL, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. β-agonist- and prostaglandin E1-induced translocation of the β-adrenergic receptor kinase: evidence that the kinase may act on multiple adenylate cyclase-coupled receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:6362–6366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark RB, Friedman J, Dixon RA, Strader CD. Identification of a specific site required for rapid heterologous desensitization of the β-adrenergic receptor by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Mol. Pharmacol. 1989;36:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lohse MJ, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG, Benovic JL. Inhibition of β-adrenergic receptor kinase prevents rapid homologous desensitization of β2-adrenergic receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:3011–3015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun S, Levitzki A. Adenosine receptor permanently coupled to turkey erythrocyte adenylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 1979;18:2134–2138. doi: 10.1021/bi00577a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proll MA, Clark RB, Butcher RW. A1 and A2 adenosine receptors regulate adenylate cyclase in cultured human lung fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1986;44:211–217. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(86)90126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]