Highlights

-

•

Neuroendocrine tumors of the extrahepatic bile ducts are extremely rare neoplasms.

-

•

They most commonly occur in young females and usually present with painless jaundice.

-

•

Preoperative diagnosis is difficult because the findings are similar to other biliary malignancies.

-

•

Surgical resection is considered to be the only curative treatment.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine tumours, Extrahepatic bile duct, Unusual biliary tumours, Case report, Surgical treatment

Abstract

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) of the extrahepatic bile ducts are extremely rare neoplasms arising from endocrine cells and have variable malignant potential. They most commonly occur in young females and usually present with painless jaundice.

Presentation of case

Here we present the case of an asymptomatic 57-year-old woman with NET of the common bile duct that was incidentally discovered on abdominal ultrasound during a medical examination. She was admitted to our hospital with a diagnosis of hepatic hilar tumor. Computed tomography revealed the tumor surrounding the hepatic hilum and duodenum. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a filling defect of the common bile duct with morphology suggestive of external compression. Endoscopic ultrasound confirmed a submucosal tumor of the duodenal bulb measuring 30 × 20 mm in size. The patient qualified for surgery with a preoperative diagnosis of submucosal tumor of the duodenal bulb. Intraoperative examination revealed that the tumor location involved the common bile duct and/or cystic duct with no signs of invasion to other organs or metastatic lymph nodes. Excision of the biliary ducts and tumor was followed by Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Histological results showed NET grade 1.

Discussion

Preoperative diagnosis of NETs is difficult because of their rarity. A definitive diagnosis is usually established intraoperatively or after histopathological evaluation.

Conclusion

For these tumors, surgical resection is currently the only treatment modality for achieving a potentially curative effect and prolonged disease-free survival.

1. Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) of the extrahepatic bile ducts are extremely rare with <200 reported cases in the literature since Pilz first described it in 1961 [1]. NETs are neoplasms with variable malignant potential and arise from endocrine cells. The most common sites for primary NETs are the gastrointestinal tract (73.7%) and bronchopulmonary system (25.1%) [2], with only 0.1%–0.4% occurring in the extrahepatic bile ducts [3], [4]. A diagnosis is rarely made during preoperative examinations, and a definitive diagnosis is established intraoperatively or after histopathological evaluation. Here we summarize the clinical course and radiological findings of a patient with an extrahepatic bile duct NET along with a literature review in line with the SCARE criteria [5].

2. Presentation of case

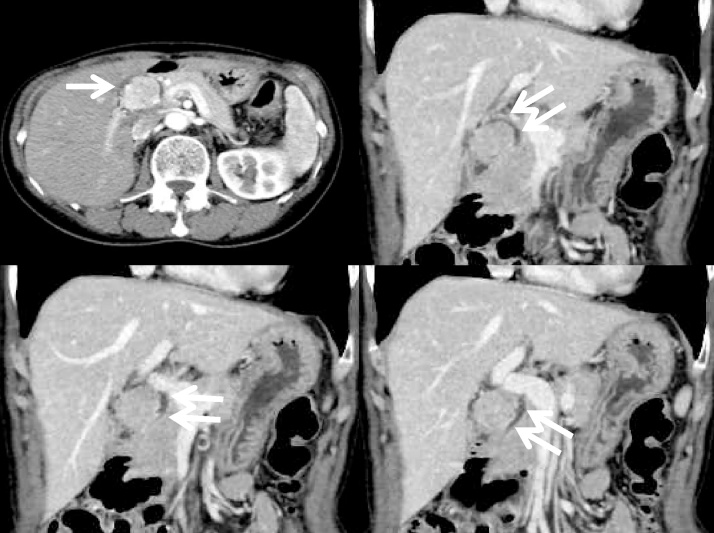

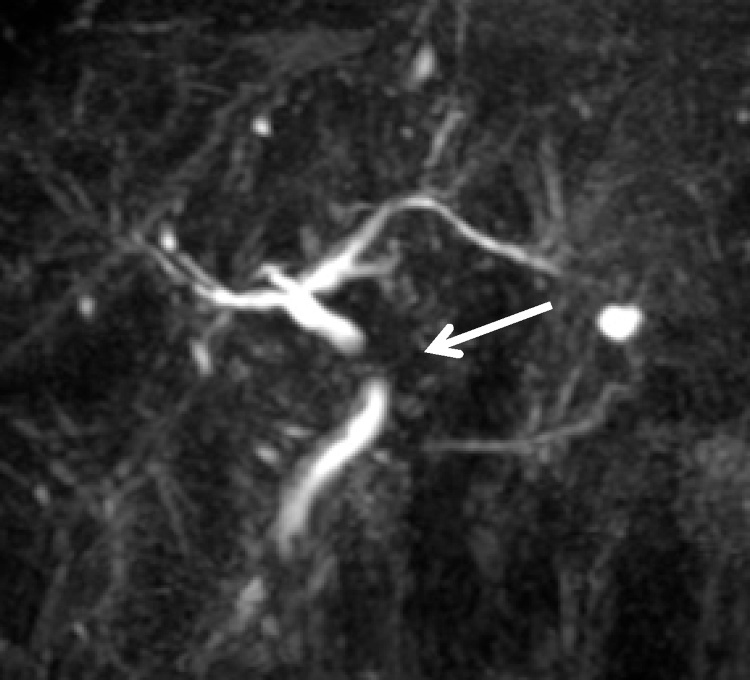

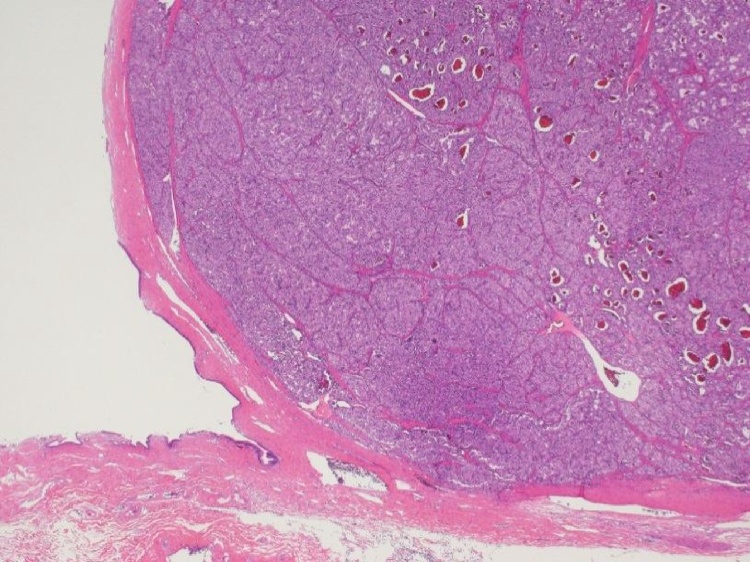

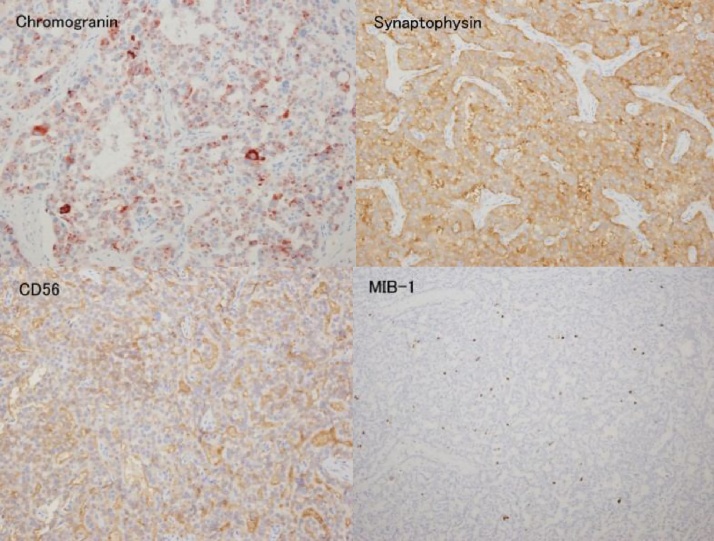

A 57-year-old woman with no past medical and surgical history was referred to our hospital for further examination of positive occult blood in her stools and a hepatic hilar tumor that was diagnosed on abdominal ultrasound during a medical examination. She had no drug and family history. She was admitted to the department of gastroenterology of our hospital in June 2014. On admission, physical examination was unremarkable, and there was no jaundice. Colon biopsy revealed ulcerative colitis; computed tomography (CT) revealed a tumor surrounding the hepatic hilum and duodenum (Fig. 1). Positron emission tomography revealed no abnormal accumulation of 2-deoxy-2-[F-18] fluoro-d-glucose in the upper abdomen. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed a filling defect of the common bile duct with a morphology corresponding to an external compression by the lesion (Fig. 2). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) confirmed the diagnosis of a 30 × 20-mm submucosal tumor of the duodenal bulb (Fig. 3). We did not perform the EUS-guided fine needle aspiration because of the incidence of high false-negative results in submucosal neoplasm. Our preoperative diagnosis was a submucosal duodenal tumor, and benign or malignant biliary tumors were included in the differential diagnosis. Intraoperative examination revealed that the tumor was located around the common bile duct and/or cystic duct, with no signs of invasion to other organs or metastatic lymph nodes. We resected the extrahepatic bile duct. The diagnosis of an intraoperative frozen section was an extrahepatic bile duct NET, and the resection margins and lymph nodes near the tumor were free of tumor. In our treatment strategy for biliary malignancies or other tumors, prophylactic pancreaticoduodenectomy was not performed in case resection margins, and lymph nodes were free of tumor. Therefore, only prophylactic portal lymphadenectomy was added. Histological examination revealed that the tumor, which originated from the intramuscular layer of the common bile duct and was located within the muscle layers, compressed the lumen of the bile duct (Fig. 4). The resection margins and lymph nodes were free of the tumor. Immunohistochemical analysis showed that neoplastic cells were positive for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and CD56 (Fig. 5). The proliferative index (Mib-1) was <2%, and histological analysis showed NET grade 1 (WHO Classification 2010) [6]. The patient’s postoperative clinical course was uneventful; she was discharged on postoperative day 32. She remains well and disease free for 34 months after surgery, with follow-ups and annual CT scans.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography revealed a tumor, with a 3-cm diameter, surrounding the hepatic hilum with the compression of the common bile duct from the outside. The tumor was enhanced in the early phase (single arrow). The extrahepatic bile duct was visible (double arrows).

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed a filling defect of the common bile duct with no dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct.

Fig. 3.

Endoscopic ultrasound showed a 30 × 20-mm submucosal tumor of the duodenal bulb.

Fig. 4.

Histological examination revealed that the tumor, generated from the intramuscular layer of the common bile duct and located within the muscle layers, compressed the lumen of the bile duct.

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical analysis showed that neoplastic cells were positive for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and CD56. The proliferative index (Mib-1) was <2%.

3. Discussion

NETs are distinct neoplasms with characteristic histological, clinical, and biological properties. They are composed of multipotent cells and have the ability to secrete numerous hormonal substances and vasoactive peptides, with serotonin, gastrin, somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, glucagon, and insulin being the most common. However, extrahepatic bile duct NETs rarely induced symptoms associated with these hormones and/or polypeptide secretion (9%) [3]. NETs may arise from argentaffin or Kulchitsky cells, which are now believed to be endoderm in origin [7], [8], [9], [10]. Kulchitsky cells, which are present throughout the gastrointestinal tract, are extremely scarce in the bile duct mucosa, possibly explaining the rarity of extrahepatic bile duct NETs [8], [9]. Chronic inflammatory changes within the bile duct may result in metaplasia of the scattered endocrine cells in the biliary epithelium, which are precursors to extrahepatic bile duct NETs [7], [9].

In a literature review regarding extrahepatic bile duct NET by Nickos et al. [2], the median age was 47 years (range, 6–79 years), with a female (61.5%) predominance. The tumors were symptomatic in 88.5% of patients. The symptoms were mostly related to tumor mass growth, invasion of adjacent structures, or metastases rather than hormone and vasoactive peptide secretion. The most common symptoms were jaundice (60.3%) and pruritus (19.2%), with 9% hormone- and vasoactive peptide-related symptoms. The most frequent sites were the common hepatic duct and distal common bile duct (19.2%), followed by the middle of the common bile duct (17.9%), cystic duct (16.7%), and proximal common bile duct (11.5%). Unlike carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct wherein two-thirds of patients present with metastatic disease, one-third of patients with extrahepatic bile duct NET present with metastases either to the local lymph nodes (19.23%) or to the liver (16.7%) [3], [10]. Therefore, prophylactic lymphadenectomy is considered necessary.

The endocrine nature of the extrahepatic bile duct NETs cannot usually be preoperatively diagnosed because of the absence of detectable serum markers and the lack of hormonal symptoms. Despite technological advances and the availability of many diagnostic imaging modalities, preoperative diagnosis is difficult because the findings are similar to other biliary malignancies. The preoperative diagnosis was reported to be feasible in only four of 78 cases (5.12%) [3]. In two patients, serum blood serotonin levels were elevated. In the other two cases, diagnosis was made from biopsy during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [11], [12]; however, targeting the tumor, particularly submucosal tumor as in this report, is usually difficult. Preoperative differentiation between NET and carcinoma may almost be impossible. Nevertheless, there are some features that differ between the two tumors and that may guide preoperative suspicion of extrahepatic bile duct NETs, which occur more frequently in females and younger patients compared with adenocarcinoma.

Extrahepatic bile duct NETs slowly grow, and aggressive surgical resection is considered to be the only curative treatment [13]. Even in palliative resection cases, medical treatment, including systemic chemotherapies, targeted therapies, somatostatin analogs, liver-directed therapies, such as chemoembolization or thermoablation, and peptide receptor radionuclide therapy, may sometimes achieve disease control [13]. However, these are treatment strategies for gastro-entero-pancreatic NETs and not for extrahepatic bile duct NETs because of their rarity.

Assessing the natural history of this disease, malignant potential of the tumors, and prognosis of these tumors are difficult because cases are rare and long-term follow-up data are often unavailable; these can be assessed only with continued detailed reporting of such cases.

4. Conclusion

Extrahepatic bile duct NETs are difficult to preoperatively diagnose because of their rarity, absence of detectable serum markers, and usual lack of hormonal symptoms. The only currently curative treatment with good long-term results is aggressive surgical resection. Continued reporting of single cases, long-term follow-up, and results of treatment are required.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this report.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Given that this is a case report with no identifiable information included in the manuscript, ethical approval was not obtained.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and its accompanying images. A copy of the written consent form is available for review for the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Author contribution

TA, AN, NS, AA, MW, AS, YT, and YT conceived the idea for the study and helped draft the manuscript. TA, AN, NS, AA, MW, AS, YT, NN, and YT participated in the clinical treatment. HS performed the pathological studies. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Guarantor

Tsuyoshi Abe.

References

- 1.Pilz E. Uber ein karzinoid des ductus choledocus. Zentralbl. Chir. 1961;86:1588–1590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modlin I.M., Shapiro A. An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoids tumors. Cancer. 1997;79:813–819. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<813::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nickos M., Theodossis S.P., Georgia K., Ioannis P., Spiros T.P., Ioannis K. Neuroendocrine tumors of extrahepatic biliary tract. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2014;20:765–775. doi: 10.1007/s12253-014-9808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modlin I.M., Lye K.D., Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934–959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosman F.T., Carneiro F., Hruban R.H., Theise N.D. IARC Press; Lyon: 2010. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamberlain R.S., Blumgart L.H. Carcinoid tumors of the extrahepatic bile duct: a rare cause of malignant biliary obstruction. Cancer. 1999;86:1959–1965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dancygier H., Klein U., Leuschner U., Hubner K., Classen M. Somatostatin-containing cells in the extrahepatic biliary tract of humans. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:892–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gusani N.J., Marsh J.W., Nalesnik M.A., Tublin M.E., Gamblin T.C. Carcinoid of the extra-hepatic bile duct: a case report with long-term follow up and review of literature. Am. Surg. 2008;74:87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrone C.R., Tang L.H., D’ Angelica M., DeMatteo R.P., Blumgart L.H., Klimstra D.S., Jarnagin W.R. Extrahepatic bile duct carcinoid tumors: malignant biliary obstruction with a good prognosis. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2007;205:357–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malecki E.A., Acosta R., Twaddell W., Heller T., Manning M.A., Darwin P. Endoscopic diagnosis of a biliary neuroendocrine tumor. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2009;70:1275–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubert C., Sempoux C., Berquin A., Deprez P., Jamar F., Gigot J.F. Bile duct carcinoids tumors: an uncommon disease but with a good prognosis? Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:1042–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walter T., Brixi-Benmansour H., Lombard-Bohas C., Cadiot G. New treatment strategies in advanced neuroendocrine tumours. Dig. Liver. Dis. 2012;44:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]