Abstract

Elizabethkingia meningoseptica is an emerging, healthcare-associated pathogen causing a high mortality rate in immunocompromised patients. We report the draft genome sequence of E. meningoseptica Em3, isolated from sputum from a patient with multiple underlying diseases. The genome has a length of 4,037,922 bp, a GC-content 36.4%, and 3673 predicted protein-coding sequences. Average nucleotide identity analysis (>95%) assigned the bacterium to the species E. meningoseptica. Genome analysis showed presence of the curli formation and assembly operon and a gene encoding hemagglutinins, indicating ability to form biofilm. In vitro biofilm assays demonstrated that E. meningoseptica Em3 formed more biofilm than E. anophelis Ag1 and E. miricola Emi3, both lacking the curli operon. A gene encoding thiol-activated cholesterol-dependent cytolysin in E. meningoseptica Em3 (potentially involved in lysing host immune cells) was also absent in E. anophelis Ag1 and E. miricola Emi3. Strain Em3 showed α-hemolysin activity on blood agar medium, congruent with presence of hemolysin and cytolysin genes. Furthermore, presence of heme uptake and utilization genes demonstrated adaptations for bloodstream infections. Strain Em3 contained 12 genes conferring resistance to β-lactams, including β-lactamases class A, class B, and metallo-β-lactamases. Results of comparative genomic analysis here provide insights into the evolution of E. meningoseptica Em3 as a pathogen.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40793-017-0269-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Draft genome, Infections, Elizabethkingia meningoseptica, Human isolate

Introduction

10.1601/nm.9258, a Gram-negative, aerobic bacillus, belongs to the family 10.1601/nm.8070 within the phylum Bacteroidaeota [1–3]. Among the three clinically important 10.1601/nm.9465 species (including 10.1601/nm.9258, 10.1601/nm.22689 and 10.1601/nm.9278), 10.1601/nm.9258 has been intensively investigated for its pathogenicity [4–6]. Most of the 10.1601/nm.9258 infections are nosocomial, often transmitted in intensive care units [1, 7]. This bacterium survives in tap water, in disinfection fluid, on wet surfaces of sinks, in ventilators, hemodialysis equipment, catheters, and other medical apparatus. 10.1601/nm.9258 infection causes neonatal meningitis, nosocomial pneumonia, bacteremia, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and skin infections [1, 4, 8]. Moreover, older (age > 65) and immunocompromised patients are more susceptible to infection; case-fatality rates have reached 50% [9].

Infections by 10.1601/nm.9258 are difficult to treat with antimicrobial agents due to multiple drug resistance [4]. Tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and β-lactams have been used to treat patients [10], but increasingly clinical isolates lack susceptibility to these antibiotics [11]. Analysis of the resistome in the related bacterium 10.1601/nm.9278 revealed multiple drug resistance genes [12]. Some antibiotics effective against Gram-positive bacteria such as vancomycin, quinolones, tigecycline, and rifampin have been used for treating 10.1601/nm.9258-infected patients, though the mechanism of action remains unclear [12, 13]. Also, the effectiveness of these antibiotics varied; many patients resolved infection but isolates showed high MICs in vitro, thus the relationship between MICs and clinical response was obscure [14]. Further genome analyses will elucidate the breadth of antibiotic susceptibility and resistance mechanisms in 10.1601/nm.9465 spp.

Differentiation of 10.1601/nm.9465 species using routine morphological and biochemical tests is difficult in clinical laboratories [14]. Comparison of 16S rRNA identity does not provide sufficient resolution to identify and separate these closely-related 10.1601/nm.9465 species [2, 14]. Characterization of 10.1601/nm.9465 species by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry would facilitate it if species reference spectra were added to the database [14]. A limitation is that MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry is not available in many smaller clinical microbiology laboratories. Whole genome analysis facilitates the development of molecular diagnosis tools (such as single nucleotide polymorphisms) that can be potentially useful for small laboratories. In this study, we sequenced, annotated and analyzed a clinical 10.1601/nm.9258 genome, with the aim of providing a better understanding of antibiotic resistance and pathogenesis mechanisms in this pathogen, and of unveiling useful biosystematic molecular markers.

Organism information

Classification and features

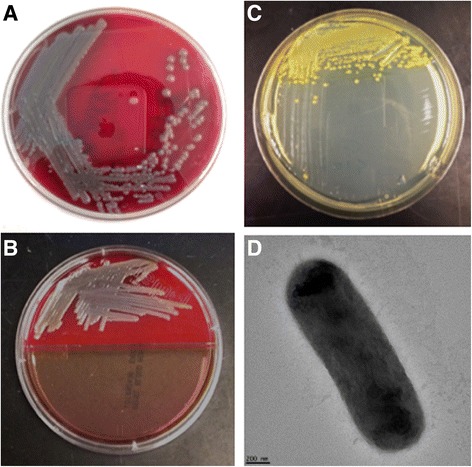

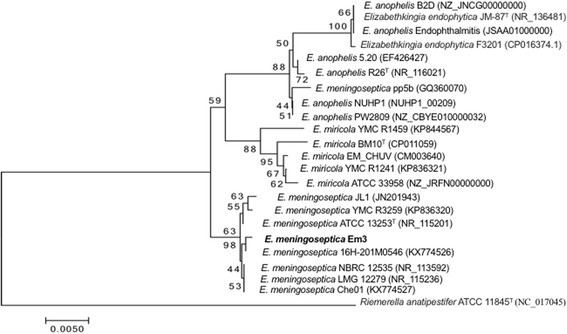

10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 (Fig. 1) was isolated from a sputum sample from a patient with multiple underlying diseases and on life support. E. meningoseptica Em3 is Gram-negative, non-motile and non-spore-forming (Fig. 1 and Table 1). A taxonomic analysis was performed by comparing the 16S rRNA gene sequence to those in the GenBank (Fig. 2). The phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences indicated that strain Em3 was clustered within a branch containing other 10.1601/nm.9258 and departing from the clusters 10.1601/nm.22689 and 10.1601/nm.9278 in the genus 10.1601/nm.9465 (Fig. 2). We further calculated the ANI and DDH values among the representative 10.1601/nm.9465 (Table 2). Our results showed that strain Em3 belongs to 10.1601/nm.9258 because of the high ANI (>95%, cutoff for species differentiation) and DDH (>70%, cutoff for species differentiation) values between strain Em3 and 10.1601/nm.9258 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DATCC+13253 T [15].

Fig. 1.

Demonstration of cell growth, pigment production and micrograph. a Em3 growing on SBA medium; b Demonstration of Em3 grown on SBA medium (control, up part) and MacConkey agar (low part). c Pigment production in Em3 grown on TSA agar. d Scanning electron microscopy image of Em3

Table 1.

Classification and general features of E. meningoseptica Em3

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [37] | |

| Phylum Bacteroidaeota | TAS [3] | ||

| Class Flavobacteriia | TAS [38] | ||

| Order Flavobacteriales | TAS [39] | ||

| Family Flavobacteriaceae | TAS [40] | ||

| Genus Elizabethkingia | TAS [2] | ||

| Species Elizabethkingia meningoseptica | TAS [2] | ||

| Strain Em3 | TAS [2] | ||

| Gram stain | Negative | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rod | IDA | |

| Motility | Non motile | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Non-spore-forming | NAS | |

| Temperature range | 4–40 °C | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 37 °C | IDA | |

| pH range; Optimum | 4–10; 8 | IDA | |

| Carbon source | Heterotroph | IDA | |

| Energy source | Varied; including glucose and mannitol | IDA | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Human | NAS |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Not determined | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | NAS |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Pathogen | NAS |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Michigan, USA | NAS |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | February, 6, 2016 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 42° 43′ 57″ N | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 84° 33′ 20″ W | NAS |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported | NAS |

aEvidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [41]

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree displays the position of E. meningoseptica Em3 (shown in bold) relative to the other type strains of Elizabethkingia based on 16S rRNA. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA v. 7.0.14 using the Neighbor-Joining method [42]. The percentage of replicate trees where the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) is indicated next to the branches. The branch lengths are scaled to the same units as those of the evolutionary distances for inferring the phylogenetic tree. The accession numbers for 16 s rRNA sequences are listed in the parenthesis following selected bacteria: E. meningoseptica LMG 12279 (NR_115236), E. meningoseptica Che01 (KX774527), E. meningoseptica NBRC 12535 (NR_113592), E. meningoseptica ATCC 13253T (NR_115201), E. meningoseptica JL1 (JN201943), E. meningoseptica YMC R3259 (KP836320), E. meningoseptica Em3, E. meningoseptica 16H-201 M0546 (KX774526), E. miricola YMC R1459 (KP844567), E. miricola BM10T (CP011059), E. miricola EM_CHUV (CM003640), E. miricola YMC R1241 (KP836321), E. miricola ATCC 33958 (NZ_JRFN00000000), E. meningoseptica pp5b (GQ360070), E. anophelis NUHP1 (NUHP1_00209), E. anophelis PW2809 (NZ_CBYE010000032), E. anophelis 5.20 (EF426427), E. anophelis R26T (NR_116021), E. anophelis Endophthalmitis (JSAA01000000), Elizabethkingia endophytica JM-87T (NR_136481), Elizabethkingia endophytica F3201 (CP016374.1), E. anophelis B2D (NZ_JNCG00000000) and Riemerella anatipestifer ATCC 11845T (NC_017045)

Table 2.

Percentage of in silico DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH)a and average nucleotide identities (ANI)b among the selected Elizabethkingia genomes

| E. meningoseptica EM3 |

E. anophelis

R26T [43] |

E. meningoseptica

ATCC 13253T [44] |

E. miricola

BM10T [45] |

E. endophytica

JM-87T [46] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. meningoseptica EM3 |

31.90

80.15 |

91.10

98.52 |

31.20

80.44 |

32.70

80.25 |

|

| E. anophelis R26T |

31.90

80.15 |

33.60

80.26 |

68.80

91.52 |

78.60

97.49 |

|

| E. meningoseptica ATCC 13253T |

91.10

98.52 |

33.60

80.26 |

31.40

80.26 |

33.30

80.41 |

|

| E. miricola BM10T |

31.20

80.44 |

68.80

91.52 |

31.40

80.26 |

68.70

91.41 |

|

| E. endophytica JM-87T |

32.70

80.25 |

78.60

97.49 |

33.30

80.41 |

68.70

91.41 |

Nucleotide sequences were downloaded from GenBank. The accession numbers for E. anophelis R26T, E. meningoseptica ATCC 13253T, E. miricola BM10T and E. endophytica JM-87T are NZ_ANIW01000001.1, NZ_ASAN01000001.1, NZ_CP011059.1 and NZ_CP016372, respectively

aIn silico DNA-DNA hybridization was calculated by using Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC) [47]. The percentage of DDH was shown on the top and bolded

bANI values were computed for pairwise genome comparison with using the OrthoANIu algorithm [48]. The percentage of ANI was shown on the bottom

The motility was tested on semi-TSA. The cells of strain Em3 are straight and rods and have a diameter of 0.7 μm and length of 24.0 μm. Strain Em3 grew on TSA, producing yellow pigment (Fig. 1). This bacterium also grew well on SBA with greyish discoloration around the colonies, showing it had the α-hemolytic activity (Fig. 1). 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 did not grow on MacConkey agar, a finding consistent with strain-dependent growth on this medium; e.g., 10.1601/nm.9258 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DCCUG+214 T grew on MacConkey agar whereas other hospital-associated 10.1601/nm.9258 strains did not [2]. Of those strains growing on MacConkey agar, lactose was not utilized [2]. The optimal growth temperature for strain Em3 was 37 °C (Table 1). Carbon source, nitrogen source utilization and osmotic tolerance were assayed by incubating cells in Biolog GEN III microplates at 37 °C overnight (CA, USA). The results showed that 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 did not tolerate 4% NaCl. 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 utilized several carbon sources, including D-maltose, D-trehalose, D-gentibiose, D-melibiose, D-glucose, D-mammose, D-fructose, D-fucose, D-mannitol and D-glycerol. The ability to use D-melibiose can differentiate 10.1601/nm.9258 from 10.1601/nm.22689 and 10.1601/nm.9278 [16]. The inability to grow on cellobiose or citrate was consistent with previous reports [16]. Moreover, 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 utilized D-serine, L-alanine, L-aspartic acid, L-glutamic acid, L-histidine and L-serine when tested on Biolog GEN III microplates.

Extended feature descriptions

Phylogenetic analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S1) was further conducted by using 19 genomes with 1181 core genes per genome (22,439 in total). As expected, 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 grouped together with the selected 10.1601/nm.9258 species and separated from the clusters 10.1601/nm.22689, 10.1601/nm.26899 and 10.1601/nm.9278, a finding similar to the phylogenetic analysis based on 16 s rRNA sequences. Further, both trees (Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Figure S1) show that species 10.1601/nm.22689 and 10.1601/nm.26899 are not separated well, which is consistent with previous reports [17].

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The genome of 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 was selected for whole genome sequencing because of its association with pulmonary disease. Comparison of strain Em3 genome with other 10.1601/nm.9465 species may provide insights into the molecular basis of pathogenicity and metabolic features of this strain. The high-quality draft genome sequence was completed on August 1, 2016 and was deposited to GenBank as a Whole Genome Shotgun project under accession number MDTY00000000 and the Genome OnLine Database with ID Gp0172366 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS 31 | Finishing quality | High-quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | two paired-end 250 bp library |

| MIGS 29 | Sequencing platforms | MiSeq-Illumina |

| MIGS 31.2 | Fold coverage | 50.0X |

| MIGS 30 | Assemblers | SPAdes 3.9.0 |

| MIGS 32 | Gene calling method | NCBI Prokaryotic Genome, Annotation Pipeline |

| Locus Tag | BFF93_ | |

| Genbank ID | MDTY00000000.1 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | October 25, 2016 | |

| GOLD ID | Gp0172366 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJNA338129 | |

| MIGS 13 | Source Material Identifier | CL16–200185 |

| Project relevance | Clinical pathogen |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

For genomic DNA isolation, E. meningoseptica Em3 (CL16–200185, Bureau of Laboratories, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services) culture was grown overnight in 25 mL LB medium at 37 °C with vigorous shaking. DNA was isolated using a Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison). The amount of genomic DNA was measured using a Nanodrop2000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo scientific) and Qubit DNA assay kit. DNA integrity was confirmed by agarose gel assay (1.5%, w/v).

Genome sequencing and assembly

NGS libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq Nano DNA Library Preparation Kit. Completed libraries were evaluated using a combination of Qubit dsDNA HS, Caliper LabChipGX HS DNA and Kapa Illumina Library Quantification qPCR assays. Libraries were combined in a single pool for multiplex sequencing and the pool was loaded on one standard MiSeq flow cell (v2) and sequencing performed in a 2x250bp, paired end format using a v2, 500 cycle reagent cartridge. Base calling was done by Illumina Real Time Analysis [18] v1.18.54 and output of RTA was demultiplexed and converted to FastQ format with Illumina Bcl2fastq v1.8.4.

The Illumina data were assembled into contiguous sequences using SPAdes version 3.9.0 [19], then short contigs (<400 bp) were filtered out. The 11 contigs identified in this strain were therefore submitted to the NCBI database as a Whole Genome Shotgun project.

Genome annotation

Annotation of the 11 contigs was first done through the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Automatic Annotation Pipeline [20]. The predicted CDSs were next translated and analyzed against the NCBI non-redundant database, iPfam, TIGRfam, InterPro, KEGG and COG. The RAST system was used to check the annotated sequences [21, 22]. Additional gene prediction and manual revision was performed by using the IMG/MER platform. 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 genome is available in IMG (genome ID = 2,703,719,242).

Genome properties

The draft genome sequence is 4,037,922 bp long, 36.37% G + C rich and contains 11 scaffolds (Table 4). Of 3729 genes predicted, 3673 encoded proteins and 56 were RNAs. 2585 (69.32%) were assigned a putative function, while the other 1088 (30.68%) were designated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of coding genes into general COG functional categories analyzed by IMG is listed in Table 5. Collectively, the genome features were similar to those in other sequenced 10.1601/nm.9258 (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Table 4.

Genome statistics of E. meningoseptica Em3

| Attribute | Value | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,037,922 | 100 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 3,571,073 | 88.44 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 1,468,714 | 36.37 |

| DNA scaffolds | 11 | NA |

| Total genes | 3729 | 100 |

| Protein coding genes | 3673 | 98.50 |

| RNA genes | 56 | 1.50 |

| Pseudo genes | 0 | 0 |

| Genes in internal clusters | 752 | 20.17 |

| Genes with function prediction | 2585 | 69.32 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1993 | 53.45 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 2740 | 73.48 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 452 | 12.12 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 818 | 21.94 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 0 |

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 186 | 8.58 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 170 | 7.84 | Transcription |

| L | 91 | 4.20 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 21 | 0.97 | Cell cycle control, Cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| V | 81 | 3.74 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 82 | 3.78 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 184 | 8.49 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 10 | 0.46 | Cell motility |

| U | 17 | 0.78 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 110 | 5.08 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 106 | 4.89 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 120 | 5.54 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 184 | 8.49 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 60 | 2.77 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 134 | 6.18 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 96 | 4.43 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 153 | 7.06 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 39 | 1.80 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 203 | 9.37 | General function prediction only |

| S | 105 | 4.85 | Function unknown |

| – | 1736 | 46.55 | Not in COGs |

Insights from the genome sequence

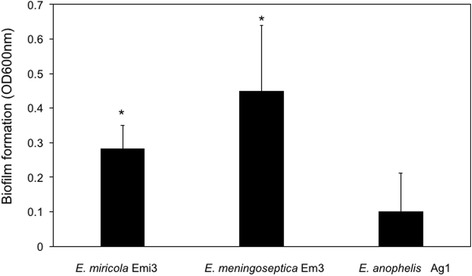

10.1601/nm.9465 bacteria cause sepsis, bacteremia, meningitis or respiratory tract infections in hospitalized patients, indicating that they have the ability to colonize host tissues, suppress the host immune response, and disrupt erythrocytes to obtain nutrients and propagate in the host bloodstream [1, 13, 14]. Genome analysis showed that 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 carried a gene (BFF93_RS1398) encoding a hemagglutinin protein. Hemagglutinins as adhesins are required for virulence in bacterial pathogens [23]. Hemagglutins facilitate infection via adherence to epithelial cell lines from the human respiratory tract in 10.1601/nm.1747 [24]. Darvish et al. showed that filamentous hemagglutinin adhesins were crucial for bacterial attachment and subsequent cell accumulation on target substrates [25]. An in vitro biofilm assay showed that, compared to the mosquito isolate 10.1601/nm.22689 Ag1, clinical isolates 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 and 10.1601/nm.9278 Emi3 formed a higher amount of biofilm (Fig. 3). Furthermore, 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 had better ability to form biofilm than did 10.1601/nm.9278 Emi3. The capacity for strain Em3 to form biofilm was further exemplified by discovery of an operon involved in curli biosynthesis and assembly (BFF93_RS03755, BFF93_RS03760, BFF93_RS03765, BFF93_03725 and BFF93_RS03775). In vitro studies demonstrated that curli fibers participated in bacterial adhesion to target cell surfaces, cell aggregation, as well as biofilm formation [26, 27]. Moreover, some studies showed that curli mediated host cell attachment and invasion in vivo [28]. Curli were involved in inducing the host inflammatory response [29]. It should be noted that this curli synthesis operon is present in 10.1601/nm.9258 while it is absent in 10.1601/nm.9278. Further experiments are warranted to test if the curli gene cluster contributed to biofilm formation in strain Em3 because biofilm formation may involve other genes.

Fig. 3.

In vitro biofilm assay in the selected Elizabethkingia sp. The cells were first cultured by shaking in TSB at 37 °C overnight. The cell density was adjusted to the same OD at 600 nm (0.1). 200 μl of cells were placed on 96-well plates for 24 h. The biofilm assay was carried out using crystal blue staining [49]. Values are mean values for single measurements from eight independent cultures. The error bars are standard deviations. The statistical test was the Student’s t-test. The asterisk indicates a significant difference compared to biofilm formation in E. anophelis Ag1 (p < 0.05).

A cytolysin encoding gene (BFF93_RS16990) was found in the strain Em3 genome, whose product belonged to a thiol-activated, CDC family [30]. CDC as a virulence factor is widely distributed among Gram-positive, opportunistic pathogens [31]. For example, 10.1601/nm.5606 utilized pore-forming CDC to translocate a protein into eukaryotic cells [32]. Disruption of expression of a hemolysin (CDC) gene in the intracellular pathogen 10.1601/nm.5096 reduced virulence in mice, showing that CDC was critical for full virulence [33]. Furthermore, perfringolysin, a CDC toxin, has cytotoxicity and leukostasis activities, allowing the cells to escape from macrophage phagosomes during 10.1601/nm.3991 gas gangrene [34]. Only a few CDCs have been found in Gram-negative bacteria [31], and this is the first report of CDC genes in 10.1601/nm.9258. It should also be noted that this cytolysin gene is located immediately downstream of hmuY, which together comprise part of an iron metabolism gene cluster. Such gene organization was only seen in 10.1601/nm.9258. This CDC protein sequence in strain Em3 shared 87%, 83% and 81% identity to that in 10.1601/nm.9258 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DATCC+13253, 10.1601/nm.9258 B2D and 10.1601/nm.9258 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DNBRC+12535, respectively. It is interesting that it did not have close identity to that in 10.1601/nm.9258 FMS-007 (48%) and 10.1601/nm.9258 502 (48%); it was absent in an 10.1601/nm.9258 strain associated with endophthalmitis [35]. Similarly, it was not conserved in 10.1601/nm.22689 (identity ranging from 0 to 50%) and absent in all 10.1601/nm.9278 species. Such observations may stress that a diverse pathogenesis process exists in various 10.1601/nm.9258 and other 10.1601/nm.9465 species.

Besides a CDC gene in strain Em3 genome, we found that there was a gene encoding the hemolysin with a CBS domain (BFF93_RS14485). Hemolysin can be possibly secreted and involved in lysis of the erythrocytes [35]. The predicted amino acid sequence was conserved in most 10.1601/nm.9258 strains (> 90%). Further examination of hemin-degrading/transporter/utilization proteins led to a discovery of the gene cluster including SAM-dependent methyltransferases (BFF93_RS02055), iron ABC transporter (BFF93_RS02045), hemin-degrading protein (hmuS, BFF93_RS02060), hemin importer ATP-binding protein (BFF93_RS02050) and iron-regulated protein (BFF93_RS02065). Furthermore, there was a gene encoding a hemin receptor (BFF93_RS03140).

Elizabethkiniga infections can be fatal in immune-compromised patients if appropriate antibiotic therapy is delayed or the antimicrobial treatment is not properly provided [9, 14]. However, Elizabethkiniga spp. are multi-drug resistant [4, 13]. The prediction results by CARD and RAST (Table 6) showed that there are at least 31 genes involved in antibiotic resistance including antibiotic inactivation enzymes and related efflux pumps in 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3. Many of them are possibly involved in mupirocin, vancomycin, β-lactam, aminocoumarin, elfamycin, isoniazid, tetracycline and fluoroquinolone resistance (Table 6). Several drugs used to treat Elizabethkiniga-infected patients in the past are not effective anymore [4], which agrees with recent resistome assays in clinical 10.1601/nm.9258 isolates [12]. Genes associated with resistance to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, tetracycline, vancomycin, and chloramphenicol, reported here in strain Em3, are present in most of the studied 10.1601/nm.9465 spp. (Table 6). Remarkably, at least 12 β-lactam resistance genes encoding MBL fold metallo-hydrolases, metallo-β-lactamases and β-lactamases (class A and B) were found in 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 genome (Table 6). Alternatively, antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin, minocycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, rifampin and novobiocin may remain effective due to absence of relevant antibiotic resistance genes in 10.1601/nm.9465 sp. [36]. Therefore, a combination of antimicrobial tests and resistome analysis, combined with rapid identification of infections, will contribute to efficient management for 10.1601/nm.9258 infections in the future.

Table 6.

Antibiotic genes prediction

| E. meningoseptica | E. anophelis | E. miricola | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus number | Gene in Em3 | Putative function | Em3 | 502 | R26 | NUHP1 | ATCC 33958 | EM_CHUV |

| β-lactam | ||||||||

| BFF93_RS01220 | bla GOB-13 | Class B carbapenemase BlaGOB-13 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS04805 | – | β-lactamase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS05700 | – | β-lactamase (EC 3.5.2.6) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS07625 | bla ACME | β-lactamase (BlaACME) VEB-1-like | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS06860 | bla B | BJP β-lactamase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS09265 | – | MBL fold metallo-hydrolase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS06995 | – | β-lactamase (EC 3.5.2.6) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS14540 | – | β-lactamase | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| BFF93_RS12085 | – | β-lactamase (EC 3.5.2.6) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS12510 | – | MBL fold metallo-hydrolase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS14000 | blaB-9 | Class B carbapenemase BlaB-9 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS01365 | – | β-lactamase (EC 3.5.2.6) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sulfonamide | ||||||||

| BFF93_RS00125 | dhfR | Dihydrofolate reductase DHFR | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS17395 | – | Bifunctional deaminase-reductase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS00125 | dhfR | Dihydrofolate reductase DHFR | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS17395 | – | Bifunctional deaminase-reductase protein | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS14765 | folP | Dihydropteroate synthase FolP (EC 2.5.1.15) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Tetracycline | ||||||||

| BFF93_RS08380 | tetA | Tetracycline efflux protein TetA | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS07335 | – | Transmembrane efflux protein | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS12745 | – | Antibiotic transporter | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Macrolide | ||||||||

| BFF93_RS00370 | lolD | Macrolide resistance, ABC transporter | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS05670 | emrB | Erythromycin resistance, EmrB/QacA | + | + | – | – | + | + |

| BFF93_RS05670 | emrB | Erythromycin resistance, EmrB/QacA | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS10830 | emrB | Erythromycin resistance, EmrB/QacA | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS03320 | – | Erythromycin esterase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Quinolone | ||||||||

| BFF93_RS04670 | gyrA | DNA gyrase GyrA subunit A (T83S) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS09245 | gyrB | DNA gyrase GyrB subunit A (M437 L) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS08895 | parE | DNA topoisomerase IV subunit B (M437F/A473L) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Aminoglycoside | ||||||||

| BFF93_RS10790 | ant-6 | Aminoglycoside 6-adenylyltransferase | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Chloramphenicol | ||||||||

| BFF93_RS14765 | catB | Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase CatB | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| BFF93_RS04080 | bcr/cflA | Bcr/CflA efflux pump | + | + | + | + | + | + |

“+” or “-” indicates the presence or absence of genes in the selected Elizabethkingia

Conclusions

The draft genome sequence of 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 isolated from a sputum sample in a patient was sequenced, annotated and described. We found that 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 had novel genes encoding thiol-activated cholesterol-dependent cytolysin, curli and heme metabolism related proteins, showing that 10.1601/nm.9258 Em3 may be a causative agent. Our results also indicated that 10.1601/nm.9258 might be resistant to β-lactam antibiotics due to the production of diverse MBLs and β-lactamases. Furthermore, these β-lactamase encoding genes were also found in other 10.1601/nm.9465 species, indicating that 10.1601/nm.9465 species were important reservoirs of novel β-lactamase genes. Comparative genomics is a crucial approach in the discovery of novel virulence determinants in 10.1601/nm.9465 species. Genome-based approaches contribute to develop novel genetic markers for future molecular diagnosis of 10.1601/nm.9465 infections.

Additional files

Phylogenetic tree of the Elizabethkingia genus. The core genome computed by EDGAR 2.0 [50] was extracted to infer a phylogeny for the 18 Elizabethkingia genomes. The amino acid sequences of the core genome were aligned using MUSCLE v3.8.31 [51], and then used to construct a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method as implemented in the PHYLIP package [52]. The accession numbers for genome sequences are listed in the parenthesis following selected bacteria: E. anophelis R26T (NZ_ANIW01000066), E. anophelis Ag1 (AHHG00000000), E. endophytica CSID 3000516978 (NZ_MAHJ01000016), E. endophytica F3201 (NZ_MAHU01000055), E. endophytica JM-87T (NZ_CP016372), E. anophelis NUHP1 (NZ_CP007547), E. anophelis CSID 3015183678 (NZ_CP014805), E. anophelis FMS007 (NZ_CP006576), E. miricola BM10T (NZ_CP011059), E. miricola CSID_3000517120 (NZ_MAGX01000009), E. miricola GTC862 (NZ_LSGQ01000033), E. meningoseptica ATCC 13253T (NZ_ASAN01000115), E. meningoseptica G4076 (NZ_CP016376), E. meningoseptica CSID_3000515919 (NZ_MAGZ01000024), E. meningoseptica EM1 (NZ_MCJH01000010), E. meningoseptica EM3 (NZ_MDTY01000011), E. meningoseptica EM2 (NZ_MDTZ01000014), E. meningoseptica G4120 (NZ_CP016378), Riemerella anatipestifer ATCC 11845T (NC_017045). (PDF 172 kb)

Genome features for the selected Elizabethkingia. Seven genomes from E. meningoseptica were provided for comparison of size, gene count, CRISPR, GC and coding count. (XLS 21 kb)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr. Jiannong Xu at the New Mexico State University for the provision of E. anophelis Ag1.

Funding

This project was funded by NIH grant R37 AI21884.

Abbreviations

- ANI

Average nucleotide identities

- CDC

Cholesterol-dependent cytolysin

- IMG/MER

Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiome Samples Expert Review

- MALDI-TOF

Matrix assisted laser desorption-ionisation time-of-flight

- MBL

Metallo-β-lactamase

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- SBA

Sheep blood agar

- TSA

Solid trypticase soy agar

Authors’ contributions

SC assembled the genome sequence, analyzed the genome data in public databases for genes of interest and wrote the manuscript. MS performed the experiments and acquired the data. FD wrote and revised the manuscript. EW analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read approved final the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40793-017-0269-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Jean SS, Lee WS, Chen FL, Ou TY, Hsueh PR. Elizabethkingia meningoseptica: an important emerging pathogen causing healthcare-associated infections. J Hosp Infect. 2014;86:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KK, Kim MK, Lim JH, Park HY, Lee ST. Transfer of Chryseobacterium meningosepticum and Chryseobacterium miricola to Elizabethkingia gen. Nov. as Elizabethkingia meningoseptica comb. nov. and Elizabethkingia miricola comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1287–1293. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oren A, da Costa MS, Garrity GM, Rainey FA, Rosselló-Móra R, Schink B, Sutcliffe I, Trujillo ME, Whitman WB. Proposal to include the rank of phylum in the international code of nomenclature of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:4284–4287. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu M-S, Liao C-H, Huang Y-T, Liu C-Y, Yang C-J, Kao K-L, Hsueh P-R. Clinical features, antimicrobial susceptibilities, and outcomes of Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (Chryseobacterium meningosepticum) bacteremia at a medical center in Taiwan, 1999–2006. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:1271–1278. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teo J, Tan SY-Y, Liu Y, Tay M, Ding Y, Li Y, Kjelleberg S, Givskov M, Lin RTP, Yang L. Comparative genomic analysis of malaria mosquito vector associated novel pathogen Elizabethkingia anophelis. Genome Biol Evol. 2014; doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ceyhan M, Celik M. Elizabethkingia meningosepticum (Chryseobacterium meningosepticum) infections in children. Int J Pediatr. 2011;2011:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2011/215237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balm MND, Salmon S, Jureen R, Teo C, Mahdi R, Seetoh T, Teo JTW, Lin RTP, Fisher DA. Bad design, bad practices, bad bugs: frustrations in controlling an outbreak of Elizabethkingia meningoseptica in intensive care units. J Hosp Infect. 2013;85:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luke SPM, Daniel SO, Annette J, Jane FT, Simon A, Hugo D, Alison HH. Waterborne Elizabethkingia meningoseptica in adult critical care. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(1):9–17. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.150139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira GH, Garcia DO, Abboud CS, Barbosa VLB, da PSL S. Nosocomial infections caused by Elizabethkingia meningoseptica: an emergent pathogen. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17:606–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neuner EA, Ahrens CL, Groszek JJ, Isada C, Vogelbaum MA, Fissell WH, Bhimraj A. Use of therapeutic drug monitoring to treat Elizabethkingia meningoseptica meningitis and bacteraemia in an adult. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1558–1560. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirby JT, Sader HS, Walsh TR, Jones RN. Antimicrobial susceptibility and epidemiology of a worldwide collection of Chryseobacterium spp.: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (1997-2001) J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:445–448. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.445-448.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opota O, Diene SM, Bertelli C, Prod'hom G, Eckert P, Greub G. Genome of the carbapenemase-producing clinical isolate Elizabethkingia miricola EM_CHUV and comparative genomics with Elizabethkingia meningoseptica and Elizabethkingia anophelis: evidence for intrinsic multidrug resistance trait of emerging pathogens. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;49:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breurec S, Criscuolo A, Diancourt L, Rendueles O, Vandenbogaert M, Passet V, Caro V, Rocha EPC, Touchon M, Brisse S. Genomic epidemiology and global diversity of the emerging bacterial pathogen Elizabethkingia anophelis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30379. doi: 10.1038/srep30379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau SKP, Chow W-N, Foo C-H, Curreem SOT, Lo GC-S, Teng JLL, Chen JHK, Ng RHY, Wu AKL, Cheung IYY, et al. Elizabethkingia anophelis bacteremia is associated with clinically significant infections and high mortality. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26045. doi: 10.1038/srep26045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kämpfer P, Busse H-J, McInroy JA, Glaeser SP. Elizabethkingia endophytica sp. nov., isolated from Zea Mays and emended description of Elizabethkingia anophelis Kämpfer et al. 2011. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:2187–2193. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doijad S, Ghosh H, Glaeser S, Kämpfer P, Chakraborty T. Taxonomic reassessment of the genus Elizabethkingia using whole-genome sequencing: Elizabethkingia endophytica Kämpfer et al. 2015 is a later subjective synonym of Elizabethkingia anophelis Kämpfer et al. 2011. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:4555–4559. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein CC, Alves JMP, Serrano MG, Buck GA, Vasconcelos ATR, Sagot M-F, Teixeira MMG, Camargo EP, Motta MCM. Biosynthesis of vitamins and cofactors in bacterium-harbouring Trypanosomatids depends on the symbiotic association as revealed by genomic analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comp Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Badretdin A, Chetvernin V, Nawrocki EP, Zaslavsky L, Lomsadze A, Pruitt KD, Borodovsky M, Ostell J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genet. 2008;9 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, Disz T, Edwards RA, Gerdes S, Parrello B, Shukla M, et al. The SEED and the rapid annotation of microbial genomes using subsystems technology (RAST) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D206–D214. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song H, Bélanger M, Whitlock J, Kozarov E, Progulske-Fox A. Hemagglutinin B is involved in the adherence of Porphyromonas gingivalis to human coronary artery endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7267–7273. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7267-7273.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Berg BM, Beekhuizen H, Willems RJL, Mooi FR, van Furth R. Role of Bordetella pertussis virulence factors in adherence to epithelial cell lines derived from the human respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1056–1062. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1056-1062.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darvish Alipour Astaneh S, Rasooli I, Mousavi Gargari SL. The role of filamentous hemagglutinin adhesin in adherence and biofilm formation in Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC19606T. Microb Pathog. 2014;74:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kline KA, Fälker S, Dahlberg S, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. Bacterial adhesins in host-microbe interactions. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:580–592. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yaron S, Römling U. Biofilm formation by enteric pathogens and its role in plant colonization and persistence. Microb Biotechnol. 2014;7(6):496–516. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia MC, Lipke PN, Klotz SA. Pathogenic microbial amyloids: their function and the host response. OA microbial. 2013;1:2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Telford JL, Barocchi MA, Margarit I, Rappuoli R, Grandi G. Pili in gram-positive pathogens. Nat Rev Micro. 2006;4:509–519. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tweten RK. Cholesterol-dependent cytolysins, a family of versatile pore-forming toxins. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6199–6209. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6199-6209.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hotze EM, Le HM, Sieber JR, Bruxvoort C, McInerney MJ, Tweten RK. Identification and characterization of the first cholesterol-dependent cytolysins from gram-negative bacteria. Infect Immun. 2013;81:216–225. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00927-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madden JC, Ruiz N, Caparon M. Cytolysin-mediated translocation (CMT). Cell. 104:143–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Portnoy DA, Jacks PS, Hinrichs DJ. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Brien DK, Melville SB. Effects of Clostridium perfringens Alpha-toxin (PLC) and perfringolysin O (PFO) on cytotoxicity to macrophages, on escape from the phagosomes of macrophages, and on persistence of C. perfringens in host tissues. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5204–5215. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5204-5215.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pradeep BE, Mahalingam N, Manivannan B, Padmanabhan K, Nilawe P, Gurung G, Chhabra A, Nagaraja V. Draft genome sequence of Elizabethkingia meningoseptica, isolated from a postoperative endophthalmitis patient. Genome Announc. 2014;2:e01335–e01314. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01335-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin P-Y, Chu C, Su L-H, Huang C-T, Chang W-Y, Chiu C-H. Clinical and microbiological analysis of bloodstream infections caused by Chryseobacterium meningosepticum in nonneonatal patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3353–3355. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3353-3355.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernardet J-F. Class II. Flavobacteriia class. nov. In: Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ, Ward NL, WWWB L, editors. Bergey’s Manual of systematic bacteriology. 2. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 106–314. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernardet JF, Order I. Flavobacteriales ord. nov. In: Krieg NR, Staley JT, Brown DR, Hedlund BP, Paster BJ, Ward NL, Ludwig W, Whitman WB, editors. Bergey’s Manual of systematic bacteriology. 2. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 105–329. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernardet, Nakagawa and Holmes 2002, 1057. In: Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, vol. 4. 2nd ed. New York: The Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetes, Tenericutes (Mollicutes), Acidobacteria, Fibrobacteres, Fusobacteria, Dictyoglomi, Gemmatimonadetes, Lentisphaerae, Verrucomicrobia, Chlamydiae, and Planctomycetes. Spring; 2011. p. 106–314.

- 41.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 For bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kukutla P, Lindberg BG, Pei D, Rayl M, Yu W, Steritz M, Faye I, Xu J. Draft genome sequences of Elizabethkingia anophelis strains R26T and Ag1 from the midgut of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Genome Announc. 2013;1(6):e01030–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Matyi SA, Hoyt PR, Hosoyama A, Yamazoe A, Fujita N, Gustafson JE. Draft genome sequences of Elizabethkingia meningoseptica. Genome Announc. 2013;1(4):e00444–e00413. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00444-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee D, Kim Y-K, Kim Y-S, Kim T-J. Complete genome sequence of Elizabethkingia sp. Bm10, a symbiotic bacterium of the wood-feeding termite Reticulitermes speratus KMT1. Genome Announc. 2015;3(5):e01181–e01115. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01181-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicholson AC, Humrighouse BW, Graziano JC, Emery B, McQuiston JR. Draft genome sequences of strains representing each of the Elizabethkingia Genomospecies previously determined by DNA-DNA hybridization. Genome Announc. 2016;4(2):e00045–e00016. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00045-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Auch AF, von Jan M, Klenk HP, Göker M. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Stand Genomic Sci. 2010;2(1):117–134. doi: 10.4056/sigs.531120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoon S-H, Ha S-M, Kwon S, Lim J, Kim Y, Seo H, Chun J. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:1613–1617. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwasny SM, Opperman TJ. Static biofilm cultures of Gram-positive pathogens grown in a microtiter format used for anti-biofilm drug discovery. Current protocols in pharmacology / editorial board, SJ Enna (editor-in-chief). 2010, 50:13A.18.11-13A.18.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Blom J, Kreis J, Spänig S, Juhre T, Bertelli C, Ernst C, Goesmann A. EDGAR 2.0: An enhanced software platform for comparative gene content analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; doi:10.1093/nar/gkw255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP - phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic tree of the Elizabethkingia genus. The core genome computed by EDGAR 2.0 [50] was extracted to infer a phylogeny for the 18 Elizabethkingia genomes. The amino acid sequences of the core genome were aligned using MUSCLE v3.8.31 [51], and then used to construct a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method as implemented in the PHYLIP package [52]. The accession numbers for genome sequences are listed in the parenthesis following selected bacteria: E. anophelis R26T (NZ_ANIW01000066), E. anophelis Ag1 (AHHG00000000), E. endophytica CSID 3000516978 (NZ_MAHJ01000016), E. endophytica F3201 (NZ_MAHU01000055), E. endophytica JM-87T (NZ_CP016372), E. anophelis NUHP1 (NZ_CP007547), E. anophelis CSID 3015183678 (NZ_CP014805), E. anophelis FMS007 (NZ_CP006576), E. miricola BM10T (NZ_CP011059), E. miricola CSID_3000517120 (NZ_MAGX01000009), E. miricola GTC862 (NZ_LSGQ01000033), E. meningoseptica ATCC 13253T (NZ_ASAN01000115), E. meningoseptica G4076 (NZ_CP016376), E. meningoseptica CSID_3000515919 (NZ_MAGZ01000024), E. meningoseptica EM1 (NZ_MCJH01000010), E. meningoseptica EM3 (NZ_MDTY01000011), E. meningoseptica EM2 (NZ_MDTZ01000014), E. meningoseptica G4120 (NZ_CP016378), Riemerella anatipestifer ATCC 11845T (NC_017045). (PDF 172 kb)

Genome features for the selected Elizabethkingia. Seven genomes from E. meningoseptica were provided for comparison of size, gene count, CRISPR, GC and coding count. (XLS 21 kb)