Abstract

Background

This review aims to critically appraise and compare the measurement properties of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-specific health-related quality of life instruments.

Methods

Medline, EMBASE and ISI Web of Knowledge were searched from their inception to May 2016. IBD-specific instruments for patients with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis or IBD were enrolled. The basic characteristics and domains of the instruments were collected. The methodological quality of measurement properties and measurement properties of the instruments were assessed.

Results

Fifteen IBD-specific instruments were included, which included twelve instruments for adult IBD patients and three for paediatric IBD patients. All of the instruments were developed in North American and European countries. The following common domains were identified: IBD-related symptoms, physical, emotional and social domain. The methodological quality was satisfactory for content validity; fair in internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, hypotheses testing and criterion validity; and poor in measurement error, cross-cultural validity and responsiveness. For adult IBD patients, the IBDQ-32 and its short version (SIBDQ) had good measurement properties and were the most widely used worldwide. For paediatric IBD patients, the IMPACT-III had good measurement properties and had more translated versions.

Conclusions

Most methodological quality should be promoted, especially measurement error, cross-cultural validity and responsiveness. The IBDQ-32 was the most widely used instrument with good reliability and validity, followed by the SIBDQ and IMPACT-III. Further validation studies are necessary to support the use of other instruments.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12955-017-0753-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Quality of life, Measurement properties, Instrument

Background

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are characterized by chronic, uncontrolled and relapsing inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, which encompasses Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is defined as a broad, multidimensional concept comprising patients’ physical health (including disease), psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and relationship to their environment [1, 2]. The evaluation of HRQoL for patients with IBD in clinical research and clinical practice enhances the understanding of the disease impact and the effects of treatments on the disease. Thus, the evaluation of HRQoL should be recognized as an important outcome indicator by patients and their clinicians.

Up to now, a large number of IBD-specific HRQoL instruments have been developed and validated for the IBD patients [3–7]. These instruments have been used to assess patients’ understanding of IBD symptoms and the subjective perception of the illness in clinical practice and research [3, 4]. They have also been used to compare the effect of treatment strategies and to provide evidence for health policy makers [3–5].

Several researchers have conducted reviews that measure the HRQoL of patients with IBD [3–8]. However, the reviews only enrolled some of the instruments, while other instruments are commonly ignored. The measurement properties and methodological quality of measurement properties should be evaluated systematically for clinical practitioner and researchers. We aimed to comprehensively collect all of the eligible IBD-specific HRQoL instruments to gain an understanding of their measurement properties. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to critically appraise and compare the measurement properties of the instruments to help clinicians and researchers select an appropriate instrument.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study was conducted following the guideline of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA statement) [9]. Articles were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) Types of patients: Patients diagnosed as CD, UC or IBD were enrolled. Patients with other diseases (infectious colitis, ischemic colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, etc.) were excluded. (2) Types of instruments: The HRQoL instruments developed and validated for patients with CD, UC or IBD were eligible. HRQoL was defined as a broad, multidimensional concept comprising patients’ physical health (including disease), psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and relationship to their environment. Both the self-administered and rater-administered instruments were included. The instruments for child or adult patients were included. (3) Types of languages: The full-text articles were published in English. General HRQoL instruments were excluded, such as the SF-36. Disease-specific instruments not related or only partially related to IBD were also excluded, such as the gastrointestinal quality of life index [10].

Literature search

The following relevant electronic databases were searched for English-language articles: Medline (via Pubmed) and EMBASE. The search period was from the inception of the databases to May 31th 2016. The search strategy for Medline (see Additional file 1: Appendix S1) consisted of 3 types of search terms for the following: (1) IBD, UC or CD; (2) HRQoL; and (3) measurement properties. The latter two filters were developed according to the syntax established by Kotecha et al. [11].

In addition, Google Scholar was used to search for relevant articles and literature. The citations of the reviews and the references of included articles were also checked. The patient-reported outcome and quality of life instruments database (website: https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/) was searched for eligible instruments. Two review authors (XLC, FBL) independently performed the literature search. Disagreements between the two authors were resolved by discussion with another author (LHZ).

Literature extraction

A set of questions regarding the characteristics of the instruments were drafted. The characteristics were as follows: Which type of disease does the instrument assess (IBD, UC or CD)? How is the instrument administered (self-administered or rater-administered)? How long does it take to complete (completion time)? At what time does it measure the HRQoL of the patients (recall period)? How many items does it contain? What is the form of the item (response options: including Likert or visual analogue scale [VAS])? What is the range of the scores? What domains does it contain? Are classical test theory and item response theory applied? Data about the first author, year of publication, the full and abbreviated names of the instrument and the country of origin (the first version) were also collected.

The methodological quality of measurement properties was assessed according to the consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments (COSMIN) checklist with a 4-point scale [12–14]. The COSMIN had the following items: internal consistency, reliability (test-retest reliability), measurement error, content validity, structural validity, hypothesis testing, cross-cultural validity, criterion validity and responsiveness. For each instrument, the measurement properties were rated as “poor”, “fair”, “good” or “excellent” based on predefined criteria [12–14]. The definitions of measurement properties for measurement properties based on COSMIN checklist are shown in Additional file 1: Appendix S2. The following measurement properties of the instruments were also evaluated: reliability (internal consistency, test-retest reliability), content validity (interviews/focus groups, pilot test), structural validity (convergent/divergent, discriminant), criterion validity and responsiveness.

The methodological quality of measurement properties was based on the original version, except that cross-cultural validity was based on the translated versions. Two of the three review authors (XLC, LHZ or YW) independently performed the article selection, screened and extracted the characteristics of the instruments and assessed the measurement properties. Disagreements between the two authors were resolved by discussion with another author (TWL or XYL).

Results

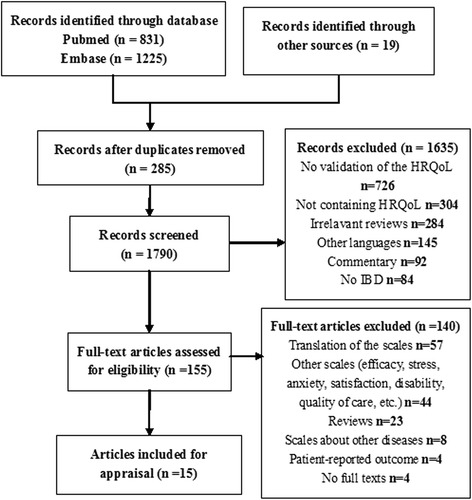

In total, 2075 articles were identified through the search, and 155 potential articles were included for the full text evaluation (Fig. 1). After manually evaluating the full text, 19 IBD-specific HRQoL instruments were identified. The Crohn’s and colitis quality of life questionnaire [15], inflammatory bowel disease impact and symptom scales [16], the Crohn’s disease patient-reported outcomes [17] and ulcerative colitis patient-reported outcomes [18] were excluded due to the lack of full text. At last, 15 articles investigating 15 IBD-specific instruments were included [19–33]. Among them, three instruments were for paediatric IBD patients, and the others were for adult IBD patients.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the search strategy

The basic characteristics of the included instruments are shown in Table 1. The quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IMPACT) [19, 34], IMPACT-II [20, 35] and IMPACT-III [21, 36] were IMPACT series instruments. The IMPACT series instruments were for paediatric IBD patients. The 32-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ-32) [22, 37], the 36-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ-36) [24], the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (SIBDQ) [23, 38] and the 9-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ-9) [25] were IBDQ series instruments. All the instruments were developed for patients with IBD, except the Crohn’s life impact questionnaire (CLIQ) for patients with CD [33]. All of the instruments were developed in North American and European countries. All of the instruments were self-administered. Four instruments also had rater-administered versions [22, 23, 25, 29]. Response options in 9 instruments were Likert scales [21–25, 27, 28, 31, 32], and others were VAS scales.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included instruments

| Instrument | Author | Year | Full name | Country | Type of disease | Mode of administration | Recall period | Completion time | Number of items | Response options | Number of domains | What scores | Range of scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For paediatrics | |||||||||||||

| IMPACT | Griffiths AM [19] | 1999 | The Quality-of-Life Index for Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Canada | PIBD | Self | NA | 10 ~ 15 min | 33 | 7 cm VAS | 6 | Total, domain | 0 ~ 231(worst-best) |

| IMPACT-II | Loonen HJ [20] | 2002 | The Quality-of-Life Index for Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease II | Netherlands | PIBD | Self | Past 2 weeks | 10 ~ 15 min | 35 | 7 cm VAS | 6 | Total, domain | 0 ~ 245(worst-best) |

| IMPACT-III | Ogden CA [21] | 2008 | The Quality-of-Life Index for Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease III | UK | PIBD | Self | Past 2 weeks | 10 ~ 15 min | 35 | 0–4 Likert | 5 | Total, domain | 0 ~ 100(worst-best) |

| For adults | |||||||||||||

| IBDQ-32 | Guyatt G [22] | 1989 | The 32-item Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | Canada | IBD | Self, rater | Past 2 weeks | NA | 32 | 1–7 Likert | 4 | Total, domain | 32 ~ 224(worst-best) |

| SIBDQ* | Irvine EJ [23] | 1996 | The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | Canada | IBD | Self, rater, IVRS | Past 2 weeks | <10 min | 10 | 1–7 Likert | 4 | Total, domain | 10 ~ 70(worst-best) |

| IBDQ-36 | Love JR [24] | 1992 | The 36-item Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | Canada | IBD | Self | Past 2 weeks | NA | 36 | 1–7 Likert | 5 | Total, domain | 1 ~ 7(worst-best) |

| IBDQ-9* | Alcalá MJ [25] | 2004 | The 9-item Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | Spain | IBD | Self, rater | Past 2 weeks | NA | 9 | 1–7 Likert | 1 | Total | 0 ~ 100(worst-best) |

| RFIPC | Drossman DA [26] | 1991 | The Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns | USA | IBD | Self | Today | NA | 25 | 100-mm VAS | 4 | Total, domain | 0 ~ 100(best-worst) |

| CCQIBD | Farmer RG [27] | 1992 | The Cleveland Clinic Questionnaire for Inflammatory Bowel Disease | USA | IBD | Self | Past 2 months | 15 ~ 20 min | 47 | 1–5 Likert | 4 | Total | 31 ~ 90(worst-best) |

| PIBDQL | Martin A [28] | 1995 | The Padova Inflammatory Bowel Disease Quality of Life | Italy | IBD* | Self | NA | NA | 29 | 0–3 Likert | 4 | Total, domain | 0 ~ 87(best-worst) |

| CGQL | Fazio VW [29] | 1999 | The Cleveland Global Quality of Life | USA | IBD* | Self, rater | Today | NA | 3 | 0–10 VAS | 3 | Total, domain | 0 ~ 1(worst-best) |

| SHS | Hjortswang H [30] | 2001 | The Short Health Scale | Sweden | IBD | Self | NA | NA | 4 | 100-mm VAS | 4 | domain | 0 ~ 100(best-worst) |

| EIBDQ | Smith GD [31] | 2002 | The Edinburgh Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | UK | IBD | Self | Past 2 weeks | NA | 13 | 0–1 or 0–3 Likert | 3 | Domain | NA(NA) |

| CLIQ | Wilburn J [33] | 2015 | The Crohn’s Life Impact Questionnaire | UK | CD | NA | NA | NA | 36 | NA | 2 | Total, domain | NA(best-worst) |

| CUCQ | Alrubaiy L [32] | 2015 | The Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis questionnaire | UK | IBD | Self | Past 2 weeks | <10 min | 8 | 0–3 Likert | 1 | Total | NA(best-worst) |

CCQIBD Cleveland Clinic Questionnaire for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (named by the author), CD Crohn’s disease, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, IVRS administration of interactive voice response system, NA not available, PIBD paediatric inflammatory bowel disease, Rater rater-administered, Self self-administered, UC ulcerative colitis, VAS visual analogue scale

IBD*: IBD patients after surgeries, including ileostomy, ileocolonic resection, proctocolectomy and ileoanal anastomosis, restorative proctocolectomy, ileal pouch anal anastomosis; Netherlands*: data from the Netherlands, Norway, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, Greece and Israel;

The SIBDQ* and IBDQ-9* were short versions of the IBDQ-32 and IBDQ-36, respectively

The numbers of domains in the 15 instruments varied from 1 to 6 (Table 2). For the instruments of paediatric IBD, the IMPACT series instruments contained four domains: IBD-related symptoms, physical functioning, emotional functioning and social functioning. For adult IBD patients, some instruments contained the above four domains, whereas some only contained one or two domains. In total, of 55 domains were obtained from all the instruments. (1) Among them, 19 domains were about IBD-related symptoms, which contained bowel or intestinal symptoms (10 domains), systemic symptoms or impairment (6 domains), other symptoms (2 domains) and disease complications (1 domain). (2) Fifteen domains were related to physical functioning or general wellbeing, comprising general quality of life or general wellbeing (5 domains), body image or body stigma (4 domains), functional functioning or impairment (2 domains), energy (2 domains), activity limitations (1 domain) and sexual intimacy (1 domain). (3) Nine domains were about emotional functioning, comprising emotional functioning or impairment (6 domains), disease-related worry (2 domains) and embarrassment (1 domain). (4) Ten domains were about social functioning, containing social functioning (6 domains), social impairment (2 domains) and treatment (2 domains). Another two domains were about information [31] and the total score of the IBDQ-9 (unidimensional) [25].

Table 2.

Domains of the included instruments

| Instrument | IBD-related symptoms (No. of items) | Physical functioning or general wellbeing (No. of items) | Emotional functioning (No. of items) | Social functioning (No. of items) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For paediatrics | ||||

| IMPACT | Bowel impairment (6), systemic impairment (2) | Body image (3) | Emotional impairment (11) | Functional/social impairment (11), treatments (3) |

| IMPACT-II | IBD symptoms (7), systemic symptoms (3) | Body image (3) | Emotional functioning (7) | Social functioning (12), treatment (3) |

| IMPACT-III | IBD symptoms (5) | Body image (4), energy (4) | Embarrassment (6), worries/concerns about IBD (13) | – |

| For adults | ||||

| IBDQ-32 | Bowel symptoms (10), systemic symptoms (5) | – | Emotional functioning (12) | Social functioning (5) |

| SIBDQ | Bowel symptoms (3), systemic symptoms (2) | – | Emotional functioning (3) | Social functioning (2) |

| IBDQ-36 | Bowel symptoms (8), systemic symptoms (7) | Functional impairment (7) | Emotional functioning (8) | Social impairment (6) |

| RFIPC | Impact of disease (13), complications of disease (4) | Body stigma (2), sexual intimacy (3) | – | – |

| CCQIBD | Medical/symptoms (9) | Affect/life in general (11), functional/economic (12) | – | Social/recreational (15) |

| PIBDQL | Intestinal symptoms (8), systemic symptoms (7) | – | Emotional functioning (9) | Social functioning (5) |

| CGQL | – | Quality of life (1), quality of health (1), energy level (1) | – | – |

| SHS | Symptom burden (1) | General wellbeing (1) | Disease-related worry (1) | Social functioning (1) |

| EIBDQ | Bowel-specific symptoms (6), disease-specific symptoms (5) | – | – | Information (2)* |

| CLIQ | – | QOL (27), activity limitations (9) | – | – |

The IBDQ-9 had only one domain: total score. The CUCQ did not report the domain

Information (2)* in the EIBDQ did not belong to social functioning

-: no domain

The methodological quality of measurement properties based on the COSMIN checklist with 4-point scale ratings is shown in Table 3. All of the instruments were developed and assessed based on classical test theory. Item response theory was also used in the IBDQ-9 and CLIQ. (1) Most of the instruments scored “excellent” or “good” for content validity. The items of these instruments were mainly from interviews with patients, review of the literature and professional experience. The pilot study was used to ensure the applicability of the items in the seven instruments. The domains of these instruments mainly contained IBD-related symptoms, physical, emotional and social functioning (Table 2). For example, the IBDQ-32 contained bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional and social domains [22]. (2) Most of the instruments scored “good” or “fair” for internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, hypotheses testing and criterion validity. For example, structural validity was rated in 12 instruments. Among them, two instruments scored “excellent” [25, 33], three scored “good” [21, 26, 31], five scored “fair” [19, 20, 22–24] and two scored “poor” [29, 30]. (3) Most of the instruments scored “fair” or “poor” for measurement error, responsiveness and cross-cultural validity. The reasons for responsiveness scoring “fair” or “poor” included: the magnitude of the correlations or differences was not stated; and the criterion for change was not considered as a reasonable gold standard. The reasons for cross-cultural validity scoring “poor” and “fair” included: whether the two translators work independently was not reported; whether the items translated forward and backward was not reported; how differences between the original and translated versions were resolved was not described in detail; the cultural relevance of the translation was not checked; and differential item function between language groups was not assessed.

Table 3.

COSMIN checklist with 4-point scale ratings of the included instruments

| Instrument | Internal consistency | Reliability | Content validity | Measurement error | Structural validity | Hypotheses testing | Criterion validity | Cross-cultural validity | Responsiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For paediatrics | |||||||||

| IMPACT | ** | *** | **** | ** | ** | **** | *** | NA | NA |

| IMPACT-II | ** | *** | **** | ** | ** | *** | *** | ** | NA |

| IMPACT-III | **** | *** | **** | ** | **** | *** | *** | *** | NA |

| For adults | |||||||||

| IBDQ-32 | *** | *** | **** | ** | ** | *** | *** | **** | ** |

| SIBDQ | ** | ** | *** | * | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| IBDQ-36 | ** | NA | ** | NA | ** | * | NA | NA | NA |

| IBDQ-9 | ** | ** | *** | ** | *** | **** | *** | * | **** |

| RFIPC | **** | ** | **** | ** | **** | ** | ** | *** | * |

| CCQIBD | NA | * | *** | NA | NA | * | ** | NA | NA |

| PIBDQL | NA | NA | ** | NA | NA | * | NA | *** | NA |

| CGQL | *** | NA | *** | NA | * | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| SHS | ** | ** | ** | ** | * | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| EIBDQ | *** | NA | **** | NA | *** | ** | *** | NA | NA |

| CLIQ | **** | *** | **** | ** | *** | *** | *** | NA | NA |

| CUCQ | ** | *** | *** | ** | NA | ** | *** | NA | **** |

*Poor, **Fair, ***Good, ****Excellent, NA: not available

The results were based on the original version, except that cross-cultural validity was based on the translated versions

The measurement properties of the instruments are shown in Table 4. (1) The IMPACT series instruments (IMPACT, IMPACT-II and IMPACT-III) were used to assess the HRQoL of paediatric IBD patients. The IMPACT series instruments, especially IMPACT-II and IMPACT-III, had good content validity and were translated into other languages. They were easily administered and contained the main domains (symptoms, physical, emotional and social domains). (2) The IBDQ-32 was considered to be of good measurement properties (content validity) and was proven to be valid, reliable and responsive. The IBDQ-32 contained the main domains: symptom, social and emotional domains. Furthermore, the IBDQ-32 was the most widely used and was translated and back-translated into a variety of languages. (3) The rating form of IBD patient concerns (RFIPC) had good content validity, internal consistency and internal consistency and acceptable responsiveness. Although the original version did not report the responsiveness, its responsiveness was confirmed in the translated version [39]. The RFIPC contained symptoms and emotional domains but did not contain emotional or social domains. (4) The SIBDQ, IBDQ-9, Cleveland global quality of life (CGQL), short health scale (SHS), Edinburgh inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (EIBDQ) and Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis questionnaire (CUCQ) were short instruments, which were all easily administered and could be completed in a short time. The IBDQ-9, SIBDQ, CUCQ and SHS had good measurement properties. The SIBDQ and IBDQ-9 were short versions of the IBDQ-32 and IBDQ-36, respectively. The SIBDQ was used in the UK, the US, Germany and Spain [40–43]. The SIBDQ contained symptoms, emotional and social domains. The IBDQ-9 was used in Spain and Iran [25, 44], which only contained one domain (total score). The SHS contained symptom burden, general wellbeing, disease-related worry and social functioning. The SHS was used in England, Norway and Sweden [45–47]. The CUCQ was used only in the UK, which should be further evaluated in other languages [32]. (5) For the IBDQ-36, the Cleveland clinic questionnaire for inflammatory bowel disease (CCQIBD) and Padova inflammatory bowel disease quality of life (PIBDQL), limited evidence was available for their measurement properties.

Table 4.

Measurement properties of the included instruments

| Internal consistency | Test-retest reliability | Interviews/focus groups | Pilot test | Convergent/divergent | Discriminant validity | Measurement error | Criterion validity | Responsiveness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For paediatrics | |||||||||

| IMPACT | 0.96 | ICC: 0.90 | (1) Interview with 82 patients (2) Based on IBDQ (3) Item generation, reduction, and selection procedure |

Pilot study, wording of question | Correlation with (1) Current disease activity: −0.54 (2) Colitis symptom score: −0.40 (3) PCDAI: −0.63 (4) Disease activity pattern: −0.43 |

Higher scores for the patients with quiescent disease (P < 0.005) | Test-retest coefficients were calculated. | Correlation with (1) Piers-Harris Happy domain: 0.61 (2) CHQ-87: 0.67 |

NA |

| IMPACT-II | 0.57 to 0.86 | ICC: 0.67 to 0.91 | Based on IMPACT | Pilot studies | NA | Higher scores in the patient with severe, moderate symptoms (P < 0.05) | Test-retest coefficients were calculated. | Correlations with Tacqol (1) Item: 0.44 to 0.63 (2) Domain: 0.46 to 0.72 |

NA |

| IMPACT-III | (1) Factor analysis conducted; (2) 0.74 to 0.88 |

ICC: 0.66 to 0.84 | Based on IMPACT | Pilot study (20 patients) | Paper and computer versions were comparable | Lower scores in the patient with severe, moderate symptom (P < 0.05) | Test-retest coefficients were calculated. | Correlations with domain of CHQ-87: 0.47 to 0.72 | NA |

| For adults | |||||||||

| IBDQ-32 | 0.70 | ICC: 0.90 to 0.99 | (1) Interview with 97 patients (2) The most frequent and important items |

NA | Correlated with CDAI (r = −0.67) | Lower scores in patients who required surgery (P < 0.05) | Standard deviations of the score changes were of similar magnitude | Correlation of changes in IBDQ and other measures were similar (P < 0.05) | Sensitivity to change for the improved or deteriorated patients (P < 0.05) |

| SIBDQ | (1) 0.78 (2) 92% and 90% of the variance in CD and UC were explained |

r: 0.65 | Based on IBDQ-32 | NA | Correlation with (1) SCCAI: −0.42 to −0.85 (2) Seo index: −0.41 to −0.64 |

Lower scores in the patients with moderate-severe relapse (P < 0.05) | Those with unchanged disease status showed no significant difference. | Correlation with the IBDQ-32 (P < 0.05) | (1) Sensitivity to change (P < 0.05) (2) decreased by −0.93 for the relapsed patients |

| IBDQ-36 | NA | NA | Based on interviewer-administered measure | NA | NA | Lower score for IBD patients than the control (P < 0.05) | NA | NA | NA |

| IBDQ-9 | (1) Rasch analysis conducted; (2) UC: 0.95; CD: 0.91 |

(1) r: 0.76 for UC, 0.86 for CD (2) ICC: 0.82 for UC, 0.84 for CD |

Based on IBDQ-36 | Pilot test | (1) Item-total correlation: 0.59 to 0.85 (2) Correlation with clinical indices of activity: UC (r = 0.70) and CD (r = 0.70) |

Lower scores in the patients with moderate-severe relapse (P < 0.01) | Scores of the first and second questionnaires correlated significantly | Correlation with IBDQ-36: 0.91 | (1) Sensitivity to change (P < 0.01) (2) effect size: UC = −2.67, CD = −5.29 |

| RFIPC | (1) Factor analysis conducted; (2) 0.79 to 0.91 |

(1) r* (instrument): 0.87 (2) r (item): 0.47 to 0.79 |

(1) 45-min interview (2) items expressed by IBD patients |

Add 3 items using pilot study | Associated with greater disease severity, female gender, and lower educational status. | Worse scores for the patients with lower educational status, greater disease severity, female patients and UC patients (P < 0.05) | Test-retest coefficients were calculated. | Associated with SCL-90 (P < 0.05) | NA |

| CCQIBD | NA | r: 0.75 to 0.95 | (1) Based on other instruments (2) Review of the literature and professional experience |

NA | NA | Lower scores for Crohn’s surgical patients (P < 0.05) | NA | Associated with sickness impact profile (P < 0.05) | NA |

| PIBDQL | NA | NA | Comprehensive definition of the patients’ health | NA | PIBDQL scores had relationship with daily stools and CDAI score (P < 0.05) | (1) Higher scores for the surgical patients (P < 0.05) (2) Lower scores for patients than healthy people (P < 0.05) |

NA | NA | NA |

| CGQL | 0.866 | NA | Structured interview | NA | NA | Lower scores in the patients with 0 ~ 5 years after surgery (P < 0.05) | NA | Correlation with SF-36: 0.31 to 0.74 (P < 0.05) | Sensitivity to change (P < 0.001) |

| SHS | NA | r: 0.71 to 0.91 | Theoretic model was presented. | NA | Correlation with PGWB: −0.51 to −0.78 | Higher scores for the patients in relapse (P < 0.001) | Test-retest coefficients were calculated. | Correlation with (1) IBDQ: −0.41 to −0.78 (2) RFIPC: 0.50 to 0.78 |

Change in SHS was related with change in disease activity P < 0.05) |

| EIBDQ | (1) Factor analysis conducted (2) Variance extracted: 63% (3) 0.55 to 0.86 |

NA | Comprehensive review of the IBD literature | Pilot study | Correlation with CDAI (1) CD: 0.52 (2) UC: 0.30 |

NA | NA | Correlation with SF-36 (1) CD: 0.48 (2) UC: 0.32 |

NA |

| CLIQ | 0.91–0.93 Rasch analysis conducted, Unidimensional |

Reproducibility: 0.91 | Literature review, qualitative interviews | Pilot study | Correlation with (1) NHP: 0.53–0.80 (2) U-FIS: 0.79 |

The QOL in different disease severity patients were significant | Test-retest coefficients were calculated. | Significant differences in CLIQ scores were observed | NA |

| CUCQ | 0.88 | ICC: 0.94 | Review the literature, consultation with patients and experts | Pilot study (20 patients) | Correlation with (1) HBI: 0.38 (2) SCCAI: 0.35 |

NA | Test-retest coefficients were calculated. | Correlations with EQ5D (r = 0.58), SF-12 (0.63 and 0.65) | (1) Sensitivity to change (P < 0.05) (2)Responsiveness ratio: 0.64 (3) standardized response mean: 0.89 |

*r: correlation coefficients; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; NA: not available

CDAI: Crohns disease activity index; CHQ-87: Child Health Questionnaire–Child Form 87; EQ5D: EuroQol 5 dimensions; HBI: Harvey Bradshaw index; NHP: Nottingham Health Profile; PCDAI: paediatric Crohn’s disease activity index; PGWB: psychological general wellbeing; SCCAI: simple clinical colitis activity index; SCL-90: The Symptom Check-List-90; SF-12: The 12-item short-form health survey; SF-36: The 36-item short-form health survey; Tacqol: TNO-AZL Children’s Quality of life questionnaire; U-FIS: Unidimensional Fatigue Impact Scale

The translated versions of the instruments are shown in Table 5. (1) For the instruments of paediatric IBD, the IMPACT-II had 3 translated versions [48–50]. The IMPACT-III had 4 translated versions [51–54]. (2) For the instruments of adult IBD, the IBDQ-32 and RFIPC were the most widely used worldwide. The IBDQ-32 has been translated and validated in 93 languages [55–70] and was found to be reliable and valid in some languages. The IBDQ-32 was also used as an important outcome in randomized controlled trials [71–75]. The RFIPC had at least 6 translated versions [76–82]. The SIBDQ had 4 translated versions [40–43]. The IBDQ-9 [44], IBDQ-36 [83, 84], PIBDQL [85] and CGQL [86] also had translated versions.

Table 5.

Translated versions of the instruments

| Instrument | Translated versions |

|---|---|

| IMPACT-II | Canadian English [48], US English [49] and Finnish [50] |

| IMPACT-III | Canadian English [51], US English [52], Croatian [53] and Swedish [54] |

| IBDQ-32 | UK English [55, 56], Dutch [57], Portuguese [58], Greek [59], Swedish [60], Norwegian [61], Japanese [62], German [63], Mandarin [64, 65], Korean [66], Lebanese [67], Brazilian [68], Italian [69] etc. |

| SIBDQ | UK English [40], German [41], US English [42] and Spanish [43] |

| IBDQ-36 | Spanish [83, 84] |

| IBDQ-9 | Spanish [25], and Iranian [44] |

| RFIPC | Swedish [76, 77], Norwegian [78], Spanish [79], French [80], Italian [81] and Greek [82] |

| PIBDQL | English [85] |

| CGQL | Hindi [86] |

| SHS | Norwegian [45], English [46] and Swedish [47] |

Other instruments did not have translated versions

Discussion

The present review summarizes an overview of 15 IBD-specific HRQoL instruments with respect to their measurement properties and the methodological quality based on the COSMIN checklist.

According to the results of the COSMIN checklist, most of the instruments did not include all the methodological quality. Only content validity was assessed properly in most of the included instruments. Most of the instruments scored “good” or “fair” for internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, hypotheses testing and criterion validity. The information regarding measurement error, responsiveness and cross-cultural validity was limited or was of poor measurement property because they did not reach the required criteria or because of insufficient information. Our results were consistent with other instruments appraised by the COSMIN criteria, such as irritable bowel syndrome-specific QOL instruments [87]; rheumatoid arthritis-specific QOL instruments [88]; and QOL instruments for infants, children and adolescents with eczema [89]. Most of the IBD-specific instruments did not show adequate methodological quality. One reason for this was that most of the IBD-specific HRQoL instruments were developed before 2010. However, COSMIN guidelines were developed approximately 2010 [12–14]. Therefore, older articles could not follow COSMIN guidelines, and their measurement properties might be underestimated.

Based on the results of the measurement properties and translated versions of the included instruments, some instruments had good psychometric characteristics and were widely used. (1) For paediatric IBD-specific instruments, most of the measurement properties were tested properly, especially the IMPACT-III [21]. The IMPACT-III had the same items as the IMPACT-II. However, The IMPACT-III was on a 0–4 Likert scale, which was easily understood by children. The IMPACT-III was translated into at least 4 translated versions [51–54]. The IMPACT-III was recommended to assess the HRQoL for paediatric IBD patients. (2) For the adult IBD instruments, the IBDQ-32 and SIBDQ (short version of IBDQ-32) had good measurement properties. The two instruments had excellent content validity and proved to be valid, reliable and responsive. The two instruments contained symptoms, emotional and social domains. The two instruments were used widely. The IBDQ-32 has been translated and validated in 93 languages. The SIBDQ was used in the UK, the US, Germany and Spain [40–43]. The IBDQ-9, CGQL, SHS, EIBDQ and CUCQ were all short instruments, which had relatively high methodological quality. However, they had fewer translated versions. The IBDQ-36, CCQIBD, PIBDQL, CGQL and EIBDQ had the lowest measurement properties. The PIBDQL and CGQL instruments were developed and assessed based on IBD patients receiving surgery, and they were translated into other languages. The EIBDQ had not been translated into other languages, which limited its use.

Compared with reviews of IBD-specific instruments published by other authors [3–8], our review had the following advantages. (1) Our review included more eligible IBD-specific HRQoL instruments. For example, the review conducted by Alrubaiy et al. enrolled 10 instruments [8]. Among them, only five instruments were about HRQoL instruments, while others were burden or disability instruments, such as the Crohn’s disease burden questionnaire, the IBD disability score and the IBD disability index. (2) Our review fully evaluated the measurement properties, including content reliability, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, measurement error, convergent/divergent, discriminant validity, criterion validity, cross-cultural validity and responsiveness. Previous reviews did not evaluate criterion validity, discriminant validity or cross-cultural validity for each instrument [8]. Criterion validity and discriminant validity are important features for the instrument. Criterion validity reflects the extent to which scores on a particular instrument relate to a gold standard. Discriminant validity refers to how well the scale can discriminate between different features of the participants.

All of the IBD-specific instruments were developed in North American and European countries. This is likely because the highest incidence and prevalence rates of IBD are in Europe and North America [90]. Another reason might be associated with the popularity of the QOL concepts and the standard procedure for QOL development [91, 92]. In developing countries, researchers mainly focused on translating and back-translating the IBD-specific instruments and used them to assess the QOL of IBD patients.

Although there was a lack of consensus regarding the specific domains among all of the instruments, the common domains measured in the instruments were identified: IBD-related symptoms, physical functioning or general wellbeing, emotional functioning and social functioning. These domains were consistent with the concepts of the common scales, such as the WHOQOL and FACT-G [92–94]. The typical manifestation of IBD included diarrhea with blood, fever, abdominal pain and malnutrition. These symptoms are the most frequently occurring, meaning that the domains contribute the most important information to the IBD-specific instruments.

The limitations of this study were as follows: (1) Non-English articles were not enrolled because of language restrictions; thus, the restriction resulted in limited negative evidence for this study; (2) Articles about the original language were used to assess the measurement properties of the included instruments. The translated articles were not used for the assessment of measurement properties; and (3) Some articles about clinical trials may have been excluded in this review, which resulted in a limited ability to examine responsiveness.

Conclusions

This review better guides the use of IBD-specific HRQoL instruments and helps clinicians and researchers choose appropriate IBD instruments. The measurement properties scored low for some IBD-specific HRQoL instruments. Based on the characteristics, measurement properties and applications of the instruments, the IBDQ-32 was the most widely used and had the strongest evidence of being reliable, valid and responsive for adult IBD patients. As a short instrument, the SIBDQ also had good measurement properties and was widely used. The IMPACT-III had good measurement properties and was widely used for paediatric IBD patients. For worldwide use of the new instruments, it is necessary to develop instruments according to the standard procedures (for example, the COSMIN) and make sure their measurement properties had excellent or good ratings. New instruments for IBD should take into account IBD-related symptoms and physical, emotional and social domains.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Min Xu in Hong Kong Baptist University for searching the full texts of the corresponding instruments.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 81774451; 81403296, 81373786), the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Guangdong Province Colleges and Universities (YQ2015041), the Young Talents Foundation of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (QNYC20140101), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2017A030313827) and the Guangdong High Level Universities Program of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine.

Availability of data and materials

All the data are available in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CCQIBD

Cleveland clinic questionnaire for inflammatory bowel disease;

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- CGQL

Cleveland global quality of life

- CLIQ

Crohn’s life impact questionnaire

- COSMIN

Consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments

- CTT

Classical test theory

- CUCQ

Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis questionnaire

- EIBDQ

Edinburgh inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel diseases

- IBDQ-32

32-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- IBDQ-36

36-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- IBDQ-9

9-Item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- IMPACT

Quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease

- IMPACT-II

Quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease II

- IMPACT-III

Quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease III

- IRT

Item response theory

- PIBDQL

Padova inflammatory bowel disease quality of life

- QOL

Quality of life

- RFIPC

Rating form of IBD patient concerns

- SHS

Short Health Scale

- SIBDQ

Short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

- VAS

Visual analogue scale

Additional file

Appendix S1 and Appendix S2. (DOC 80 kb)

Authors’ contributions

XLC carried out the design, assessed the measurement properties of the instruments and wrote and modified the manuscript. LHZ assessed the measurement properties of the instruments, wrote and modified the manuscript. YW helped to extract the data and assessed the measurement properties. TWL and XYL helped to extract the characteristics of the studies. ZKH and YH helped to interpret the results. CWM performed the statistical analyses. FBL carried out the design and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12955-017-0753-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xin-Lin Chen, Email: chenxlsums@126.com.

Feng-Bin Liu, Email: liufb163@163.com.

References

- 1.Saxena S, Orley J. Quality of life assessment: the World Health Organization perspective. European psychiatry. 1997;12:263s–266s. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)89095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Power M, Bullinger M, Harper A. The World Health Organization WHOQOL-100: tests of the universality of quality of life in 15 different cultural groups worldwide. Health Psychol. 1999;18:495–505. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.18.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munkholm P, Pedersen N. Evaluation of quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. In: In: Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: From Epidemiology and Immunobiology to a Rational Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approach.

- 4.Veríssimo R. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. In: In: Inflammatory Bowel Disease - Advances in Pathogenesis and Management.

- 5.Irvine EJ. Quality of life of patients with ulcerative colitis: past, present, and future. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:554–565. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wexner SD, Frattini JC: Quality of life in Crohn's disease. In: Handbook of Disease Burdens and Quality of Life Measures.

- 7.Pallis AG, Mouzas IA. Instruments for quality of life assessment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:682–688. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(00)80330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alrubaiy L, Rikaby I, Dodds P, Hutchings HA, Williams JG. Systematic review of health-related quality of life measures for inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:284–292. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmulling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H. Gastrointestinal quality of life index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg. 1995;82:216–222. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotecha D, Ahmed A, Calvert M, Lencioni M, Terwee CB, Lane DA. Patient-reported outcomes for quality of life assessment in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of measurement properties. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–549. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RW, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:651–657. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9960-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alrubaiy L, Hutchings HA, Williams JG. Protocol for a prospective multicentre cohort study to develop and validate two new outcome measures for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003192. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rauchensteiner S, Miltenburger C, Schaefer M. PGI25 Development and validation of patient reported outcomes measurement scales for Crohn's disease: the inflammatory bowel disease impact and symptom scales (IBDIMSYS) Value Health. 2007;10:A359. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3015(10)65274-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins PD, Harding G, Patrick DL, Revicki DA, Globe G, Viswanathan HN, Trease S, Fitzgerald K, Borie DC, Leidy NK. Tu1124 Development of the Crohn's Disease Patient-Reported Outcomes (CD-PRO) Questionnaire. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S-768. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins PD, Harding G, Patrick DL, Revicki DA, Globe G, Viswanathan HN, Trease S, Fitzgerald K, Borie DC, Leidy NK. Tu1123 Development of the Ulcerative Colitis Patient-Reported Outcomes (UC-PRO) Questionnaire. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S-768. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffiths AM, Nicholas D, Smith C, Munk M, Stephens D, Durno C, Sherman PM. Development of a quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: dealing with differences related to age and IBD type. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:S46–S52. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loonen HJ, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF, de Haan RJ, Bouquet J, Derkx BHF. Measuring quality of life in children with inflammatory bowel disease: the impact-II (NL) Qual Life Res. 2002;11:47–56. doi: 10.1023/A:1014455702807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogden CA, Abbott J, Aggett P, Derkx BH, Maity S, Thomas AG. Pilot evaluation of an instrument to measure quality of life in British children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:117–120. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000304467.45541.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine E, Singer J, Williams N, Goodacre R, Tompkins C. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804–810. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(89)80080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Love JR, Irvine EJ, Fedorak RN. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:15–19. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alcalá MJ, Casellas F, Fontanet G, Prieto L, Malagelada J. Shortened questionnaire on quality of life for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:383–391. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200407000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Patrick DL. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701–712. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farmer RG, Easley KA, Farmer JM. Quality of life assessment by patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cleve Clin J Med. 1992;59:35–42. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.59.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin A, Leone L, Fries W, Naccarato R. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1995;27:450–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fazio VW, O'riordain MG, Lavery IC, Church JM, Lau P, Strong SA, Hull T. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;230:575–584. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Tysk C, Blomberg B, Almer S, Ström M. The short health scale: a valid measure of subjective health in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;41:1196–1203. doi: 10.1080/00365520600610618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith GD, Watson R, Palmer KR. Inflammatory bowel disease: developing a short disease specific scale to measure health related quality of life. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39:583–590. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7489(01)00042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alrubaiy L, Cheung WY, Dodds P, Hutchings HA, Russell IT, Watkins A, Williams JG. Development of a short questionnaire to assess the quality of life in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:66–76. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jju005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilburn J, McKenna SP, Twiss J, Kemp K, Campbell S. Assessing quality of life in Crohn's disease: development and validation of the Crohn's life impact questionnaire (CLIQ) Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2279–2288. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otley A, Smith C, Nicholas D, Munk M, Avolio J, Sherman PM, Griffiths AM. The IMPACT questionnaire: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:557–563. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200210000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loonen HJ, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF, Koopman HM, Derkx HHF. Quality of life in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease measured by a generic and a disease-specific questionnaire. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogden CA, Akobeng AK, Abbott J, Aggett P, Sood MR, Thomas AG. Validation of an instrument to measure quality of life in British children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:280–286. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182165d10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irvine EJ. Quality of life-measurement in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:36–39. doi: 10.3109/00365529309098355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irvine EJ, Feagan BG, Wong CJ. Does self-administration of a quality of life index for inflammatory bowel disease change the results? J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Moum B, Bernklev T. Worries and concerns among inflammatory bowel disease patients followed prospectively over one year. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:492034. doi: 10.1155/2011/492034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Barton JR, Welfare MR. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire is reliable and responsive to clinically important change in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2921–2928. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rose M, Fliege H, Hildebrandt M, Körber J, Arck P, Dignass A, Klapp B. Validation of the new German translation version of the "short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire" (SIBDQ) Z Gastroenterol. 2000;38:277–286. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-14868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lam MY, Lee H, Bright R, Korzenik JR, Sands BE. Validation of interactive voice response system administration of the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:599–607. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.López-Vivancos J, Casellas F, Badia X, Vilaseca J, Malagelada JR. Validation of the Spanish version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire on ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Digestion. 1999;60:274–280. doi: 10.1159/000007670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samsamikor M, Daryani NE, Asl PR, Hekmatdoost A. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized, double-blind. Placebo-controlled Pilot Study Arch Med Res. 2015;46:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jelsness-Jørgensen L-P, Bernklev T, Moum B. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: translation, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change of the Norwegian version of the short health scale (SHS) Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1671–1676. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDermott E, Keegan D, Byrne K, Doherty GA, Mulcahy HE. The short health scale: a valid and reliable measure of health related quality of life in English speaking inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohn's Colitis. 2013;7:616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stjernman H, Grännö C, Järnerot G, Ockander L, Tysk C, Blomberg B, Ström M, Hjortswang H. Short health scale: a valid, reliable, and responsive instrument for subjective health assessment in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:47–52. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otley AR, Griffiths AM, Hale S, Kugathasan S, Pfefferkorn M, Mezoff A, Rosh J, Tolia V, Markowitz J, Mack D. Health-related quality of life in the first year after a diagnosis of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:684–691. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perrin JM, Kuhlthau K, Chughtai A, Romm D, Kirschner BS, Ferry GD, Cohen SA, Gold BD, Heyman MB, Baldassano RN. Measuring quality of life in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: psychometric and clinical characteristics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:164–171. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812f7f4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haapamäki J, Roine RP, Sintonen H, Kolho KL. Health-related quality of life in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease related to disease activity. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:832–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otley AR, Xu S, Yan S, Olson A, Liu G, Griffiths AM. IMPACT-III is a valid, reliable and responsive measure of health-related quality of life in pediatric Crohn's disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:S49. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000256260.38116.4a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Disease activity, behavioral dysfunction, and health-related quality of life in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1581–1586. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdovic S, Mocic Pavic A, Milosevic M, Persic M, Senecic-Cala I, Kolacek S. The IMPACT-III (HR) questionnaire: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in Croatian children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn's Colitis. 2013;7:908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Werner H, Landolt MA, Buehr P, Koller R, Nydegger A, Spalinger J, Heyland K, Schibli S, Braegger CP. Validation of the IMPACT-III quality of life questionnaire in Swiss children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.W-y C, Garratt AM, Russell IT, Williams JG. The UK IBDQ- a British version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: development and validation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:297–306. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Han SW, McColl E, Steen N, Barton JR, Welfare MR. The inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a valid and reliable measure in ulcerative colitis patients in the north east of England. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:961–966. doi: 10.1080/003655298750026994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Russel MG, Pastoor CJ, Brandon S, Rijken J, Engels L, Van der Heijde D, Stockbrügger RW. Validation of the Dutch translation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ): a health-related quality of life questionnaire in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 1997;58:282–288. doi: 10.1159/000201455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pontes RMA, Miszputen SJ, Ferreira-Filho OF. Miranda C, Ferraz MB. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: translation to Portuguese language and validation of the "inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire"(IBDQ) Arq Gastroenterol. 2004;41:137–143. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032004000200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vlachonikolis IG, Pallis AG, Mouzas IA. Improved validation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire and development of a short form in Greek patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1802–1812. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Tysk C, Blomberg B, Almer S, Ström M. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire in Swedish patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:77–85. doi: 10.1080/00365520150218093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernklev T, Moum B, Moum T. Inflammatory bowel south-eastern Norway Group of G. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: translation, data quality, scaling assumptions, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change of the Norwegian version of IBDQ. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1164. doi: 10.1080/003655202760373371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hashimoto H, Green J, Iwao Y, Sakurai T, Hibi T, Fukuhara S. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Japanese version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1138–1143. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hauser W, Dietz N, Grandt D, Steder-Neukamm U, Janke KH, Stein U, Stallmach A. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire IBDQ-D, German version, for patients with ileal pouch anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie. 2004;42:131–140. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-812835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ren WH, Lai M, Chen Y, Irvine EJ, Zhou YX. Validation of the mainland Chinese version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ) for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:903–910. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leong RWL, Lee YT, Ching JYL, Sung JJY. Quality of life in Chinese patients with inflammatory bowel disease: validation of the Chinese translation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:711–718. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim WH, Cho YS, Yoo HM, Park IS, Park EC, Lim JG. Quality of life in Korean patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease and intestinal Behcet's disease. Int J Color Dis. 1999;14:52–57. doi: 10.1007/s003840050183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abdul-Baki H, ElHajj I, El-Zahabi L, Azar C, Aoun E, Zantout H, Nasreddine W, Ayyach B, Mourad FH, Soweid A. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Lebanon. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;13:475–480. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oliveira S, Zaltman C, Elia C, Vargens R, Leal A, Barros R, Fogaça H. Quality-of-life measurement in patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving social support. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:470–474. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ciccocioppo R, Klersy C, Russo ML, Valli M, Boccaccio V, Imbesi V, Ardizzone S, Porro GB, Corazza GR. Validation of the Italian translation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maleki I, Taghvaei T, Barzin M, Amin K, Khalilian A. Validation of the Persian version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ) in ulcerative colitis patients. Caspian J Intern Med. 2015;6:20–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kennedy AP, Nelson E, Reeves D, Richardson G, Roberts C, Robinson A, Rogers AE, Sculpher M, Thompson DG. A randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness and cost of a patient orientated self management approach to chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:1639–1645. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schreiber S, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Kamm MA, Boivin M, Bernstein CN, Staun M, Thomsen OØ, Innes A. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of certolizumab pegol (CDP870) for treatment of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:807–818. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, Sutherland LR, Thomson AB, Williams CN, Nilsson L, Persson T. Oral budesonide as maintenance treatment for Crohn's disease: a placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Canadian inflammatory bowel disease study group. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:45–51. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van Assche G, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, D'Haens G, Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Ternant D, Watier H, Paintaud G, Rutgeerts P. Withdrawal of immunosuppression in Crohn's disease treated with scheduled infliximab maintenance: a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1861–1868. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hjortswang H, Strom M, Almeida RT, Almer S. Evaluation of the RFIPC, a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire, in Swedish patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:1235–1240. doi: 10.3109/00365529709028153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jaghult S, Saboonchi F, Johansson U-B, Wredling R, Kapraali M. Factor structures of the Swedish version of the RFIPC: investigating the validity of measurements of IBD Patients' worries and concerns. Gastroenterology Research. 2010;3:191–200. doi: 10.4021/gr247w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Torp R, Moum BA. Chronic fatigue is associated with impaired health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:106–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Torres EA, Pérez C, Chinea B, Arroyo J, Aponte N, Guzmán A, Magno P, Provenzale D. Evaluation of the rating form for inflammatory bowel diseases patients concerns (RFIPC) spanish translation in Puerto Ricans with IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;118:2643. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blondel-Kucharski F, Chircop C, Marquis P, Cortot A, Baron F, Gendre J-P, Colombel F. Health-related quality of life in Crohn's disease: a prospective longitudinal study in 231 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2915–2920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Levenstein S, Li Z, Almer S, Barbosa A, Marquis P, Moser G, Sperber A, Toner B, Drossman DA. Cross-cultural variation in disease-related concerns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1822–1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Argyriou K, Roma E, Kapsoritakis A, Tsakiridou E, Oikonomou K, Manolakis A, Potamianos S. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: translation, validation, and first implementation of the Greek version. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:6267175. doi: 10.1155/2017/6267175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Casellas F, Alcalá MJ, Prieto L, Miró JR, Malagelada JR. Assessment of the influence of disease activity on the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease using a short questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:457–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Casellas F, Arenas JI, Baudet JS, Fabregas S, Garcia N, Gelabert J, Medina C, Ochotorena I, Papo M, Rodrigo L. Impairment of health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a Spanish multicenter study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:488–496. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000159661.55028.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scarpa M, Victor CJ, O'Connor BI, Cohen Z, McLeod RS. Validation of an English version of the Padova quality of life instrument to assess quality of life following ileal pouch anal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:416–422. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0775-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Somashekar U, Gupta S, Soin A, Nundy S. Functional outcome and quality of life following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis in Indians. Int J Color Dis. 2010;25:967–973. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0974-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee J, Lee EH, Moon SH. A systematic review of measurement properties of the instruments measuring health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:2985–2995. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee J, Kim SH, Moon SH, Lee EH. Measurement properties of rheumatoid arthritis-specific quality-of-life questionnaires: systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2779–2791. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0716-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Heinl D, Prinsen CAC, Sach T, Drucker AM, Ofenloch R, Flohr C, Apfelbacher C. Measurement properties of quality-of-life measurement instruments for infants, children and adolescents with eczema: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:878–889. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:S3–S9. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000195385.19268.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Powers JH, Scott JA, Rock EP, Dawisha S, O'Neill R, Kennedy DL. Patient-reported outcomes to support medical product labeling claims: FDA perspective. Value Health. 2007;10:S125–S137. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.The WHOQOL Group The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1569–1585. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.WHOQoL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 94.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available in the manuscript.