Abstract

The mesenchymal epithelial transition factor receptor (MET) is a potential therapeutic target in a number of cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In NSCLC, MET pathway activation is thought to occur via a diverse set of mechanisms that influence properties affecting cancer cell survival, growth, and invasiveness. Preclinical and clinical evidence suggest a role for MET activation as both a primary oncogenic driver in subsets of lung cancer, and as a secondary driver of acquired resistance to targeted therapy in other genomic subsets. In this review, we explore the biology and clinical significance behind MET exon 14 (METex14) alterations and MET amplification in NSCLC, the role of MET amplification in the setting of acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in EGFR-mutant NSCLC, and the history of MET pathway inhibitor drug development in NSCLC, highlighting current strategies that enrich for biomarkers that are likely to be predictive of response. While previous trials that focused on MET pathway-directed targeted therapy in unselected or MET overexpressing NSCLC yielded largely negative results, more recent investigations focusing on METex14 alterations and MET amplification have been notable for meaningful clinical responses to MET inhibitor therapy in a substantial proportion of patients.

Introduction

Phase III randomized trials of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy for EGFR-mutant and ALK-rearranged lung cancers have documented improvements in response and progression-free survival (PFS),1, 2 and seven TKIs have gained regulatory approval for the treatment of patients with these tumors. The treatment landscape continues to evolve as durable responses to targeted therapy have been reported in a growing number of other genomic subsets.3, 4

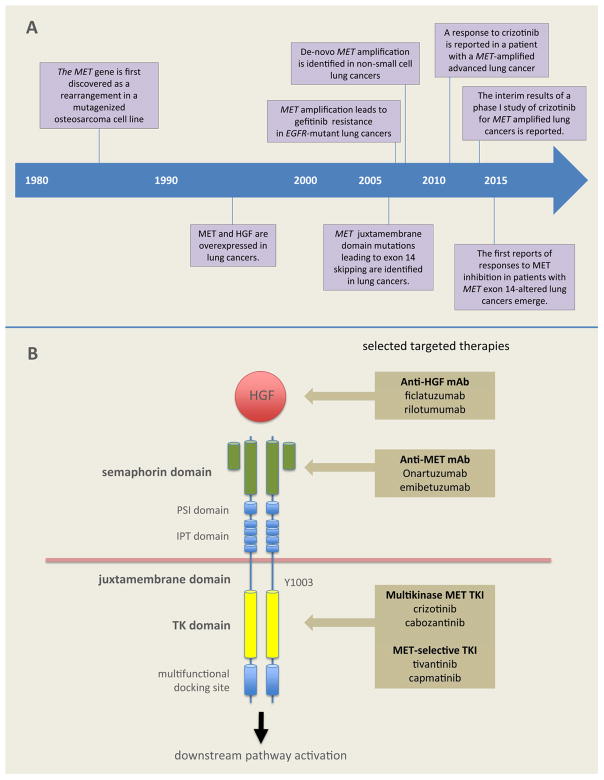

The path to approval of targeted therapy for lung cancers with alterations of the MET gene, however, has not been straightforward. First discovered in the mid-1980s, the MET pathway was found to be dysregulated in lung cancer in the 1990s (Figure 1A).5, 6 More than twenty agents targeting MET or its ligand, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), have undergone preclinical and clinical study, but findings have ranged from impressively large responses in molecularly pre-selected subtypes of NSCLC in single-arm trials to the prominent failure of large phase III studies in different trial populations.

FIGURE 1.

A. Timeline of discovery in lung cancers harboring alterations of the MET pathway. B. The MET receptor and selected MET pathway-directed targeted therapies CEP7, centromeric portion of chromosome 7; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IPT, immunoglobulin-plexin transcription; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MET, mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor; PSI, plexin semaphoring integrin domain; TK, tyrosine kinase; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

This review summarizes MET pathway dysregulation in lung cancers and critiques different scientific methods and clinical trial approaches taken for translating these into predictive biomarkers of benefit from MET inhibition.

The MET pathway and targeted therapy

The MET gene, located on chromosome 7q21–q31, is approximately 125 kilobases long, with 21 exons.7, 8 The 150 kDa MET polypeptide undergoes glycosylation to a 190 kDa glycoprotein that functions as a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase.8 The extracellular region of MET contains semaphorin, cysteine-rich, and immunoglobulin domains; the intracellular region consists of a juxtamembrane domain, a tyrosine kinase catalytic domain, and a carboxyterminal docking site (Figure 1B).9, 10

MET is activated when the HGF ligand binds to the MET receptor, inducing homodimerization and phosphorylation of intracellular tyrosine residues.8 This activates downstream RAS/ERK/MAPK, PI3K-AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, and STAT signaling pathways. Depending on the cellular context, these pathways can drive cell proliferation, survival, migration, motility, invasion, angiogenesis, and the epithelial to mesenchymal transition.9, 11 In embryonic development, MET and HGF are important in placental trophoblast and hepatocyte formation.12 In adults, both are broadly expressed in a variety of tissues, and can be upregulated in response to tissue injury.8

Dysregulation of the MET pathway in lung cancer occurs via a variety of mechanisms including gene mutation, amplification, rearrangement, and protein overexpression. MET was first discovered as an oncogene, with the identification of a TPR-MET fusion in a mutagenized osteosarcoma cell line. The fusion oncoprotein lacked the juxtamembrane Y1003 and was unaffected by c-Cbl recruitment and ubiquitination.13 A KIF5B-MET fusion has since been detected by The Cancer Genome Atlas via RNA sequencing in a sample from a patient with lung adenocarcinoma,14 however, MET rearrangements are likely to be rare events in lung cancers.

Several agents have been developed to target MET or HGF (Figure 1B). These are divided into small molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies. The small molecule TKIs are further subdivided into multikinase and selective MET inhibitors. Examples of multikinase MET-inhibitors include crizotinib, cabozantinib, MGCD265, AMG208, altiratinib, and golvatinib. Selective MET inhibitors include the ATP-competitive agents capmatinib and tepotinib (MSC2156119J),15, 16 and the ATP-non-competitive agent tivantinib.17 Monoclonal antibody therapy is divided into anti-MET antibodies (e.g. onartuzumab and emibetuzumab [LY2875358]),18–20 and anti-HGF antibodies (e.g. ficlatuzumab [AV-299] and rilotumumab [AMG 102]).10, 21

Recognizing the diversity of putative alterations resulting in MET pathway activation in NSCLC, the challenge has been to determine the best way to distinguish a true sensitizing MET signature, either as a primary driver state or as a co-driver state in the setting of acquired resistance to EGFR-directed therapy. For diagnostic purposes, this would involve selection from a combination of continuous and potentially overlapping MET-related biomarkers.

MET as a primary driver in NSCLC

By analogy with ALK rearrangements and EGFR mutations, it is conceivable that some NSCLCs may be primarily driven by, and therefore addicted to, the MET pathway alone. In the presence of an active MET-inhibitor, precedent from other driver states suggests monotherapy against MET should display clear evidence of anti-cancer activity. To date, two partially overlapping MET-related states in NSCLC have shown promise: MET exon 14 (METex14) alterations and MET gene amplification.

METex14-altered lung cancers

While tumors such as sporadic and hereditary renal cell carcinomas harbor activating mutations of the MET kinase domain,22 lung cancers commonly harbor mutations in the extracellular/juxtamembrane domains.23 The extracellular semaphorin domain is thought to be required for receptor activation and dimerization,24 however, the relevance of mutations in this domain remains unclear. In contrast, juxtamembrane domain mutations often result in METex14 alterations.

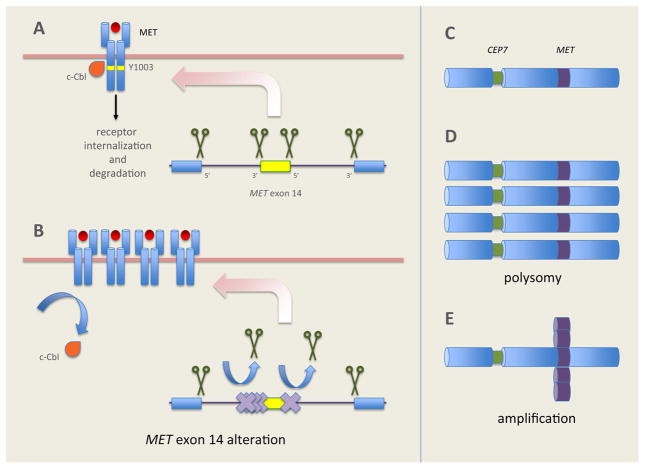

Cancers with METex14 alterations, a prime example of the association between aberrant splicing and oncogenesis, were initially reported in small cell lung cancer and NSCLC in 2003 and 2005, respectively.25, 26 Normally, introns flanking METex14 in pre-mRNA are spliced out, resulting in mRNA containing METex14 that is translated into a functional MET receptor (Figure 2A). METex14 encodes part of the juxtamembrane domain containing Y1003 the c-Cbl E3 ubiquitin ligase binding site.27 Ubiquitination tags the MET receptor for degradation. Juxtamembrane domain mutations that disrupt splice sites flanking METex14 result in aberrant splicing (Figure 2B). These mutations result in METex14 skipping, producing a truncated MET receptor lacking the Y1003 c-Cbl binding site. Losing this binding site results in decreased ubiquitination and degradation of the MET protein, sustained MET activation, and oncogenesis.28 Decreased degradation of the MET receptor is thought to potentially cause MET overexpression on some tumors that is detectable by methods such as immunohistochemistry (IHC).

FIGURE 2.

The pathobiology of METex14 alterations and MET amplification CEP7, centromeric portion of chromosome 7; IPT, immunoglobulin-plexin transcription; MET, mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor; METex14, mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor exon 14; PSI, plexin semaphoring integrin domain

METex14 alterations are extremely diverse. Base substitutions or indels disrupt several gene positions important for splicing out introns flanking METex14,29 including the branch point, polypyrimidine tract, 3′ splice site of intron 13, and the 5′ splice site of intron 14.27, 28, 30 The Cancer Genome Atlas project identified METex14 alterations resulting in incomplete splicing from the mature mRNA, leaving low-level expression of un-truncated MET.31 Notably, point mutations or deletions within METex14 can affect the Y1003 residue, resulting in c-Cbl binding site loss-of-function without necessarily causing METex14 skipping.29–31

The diversity of METex14 alterations presents challenges for diagnostic testing.12, 29 Algorithms for molecular profiling will need to rapidly move toward comprehensive clinical sequencing platforms permitting routine detection of these mutations.32 Currently, DNA-based broad, hybrid-capture next generation sequencing (NGS) represents the most commonly used tool. RNA-based sequencing using anchored multiplex polymerase chain reaction,33 or NanoString (Seattle, WA) technology provide complementary tools.32 It should be noted that NGS is a platform, not a standardized test, and detection of specific genomic alterations crucially depends on the primers within the NGS panel. It cannot be assumed that the wide array of METex14 variants will be equally detected (or detected at all) by every NGS panel used in clinical practice. Similarly, RNA-based testing, although a means of getting around the underlying variety of DNA-based changes by focusing on the more uniform resultant RNA-related splice-altered message, is not routinely performed in the clinic. Furthermore, the amount of tissue available after DNA-based NGS can be scant and inadequate for further RNA-based testing. Future diagnostic investigation must explore tests that will detect these changes in a manner suitable for widespread clinical use.

Lung cancers harboring METex14 alterations have been found to overexpress MET via IHC (3+ in 100% of cells in select cases).32 MET overexpression is not found in all cases documented in the literature. In one series, stage IV METex14-altered lung cancers were more likely to display strong MET IHC expression compared to stage IA-IIIB METex14-altered lung cancers.30 Rapid initial IHC screening has been proposed to narrow the population to undergo more comprehensive molecular profiling. To estimate the validity of this approach, better data on the prevalence of MET IHC 3+ cases that contain METex14 variants are required.34

METex14 alterations are detected in 3–4% of lung adenocarcinoma samples (Table 1),29, 31 a prevalence comparable to ALK-rearranged lung cancers.35 These mutations occur in tumors from older patients with a lower percentage of never-smokers compared to patients with tumors harboring other oncogenes.30 In a series of 687 Asian patients with resected NSCLC, METex14 alterations were poor prognostic factors for overall survival (OS).34

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of MET exon 14 alterations and MET amplification in NSCLC using different testing methods

| Study | Genomic alteration | Diagnostic method | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| METex14 alterations | |||

| Cancer Genome Atlas. 201431 | Exon 14 alterations | WES | 4.3% (10/230) |

| Frampton et al. 201529 | Exon 14 alterations | Parallel DNA sequencing | 3% (131/4,402) |

| Okuda et al. 200850 | Exon 14 alterations | Direct sequencing | 1.7% (3/178) |

| Onozato et al. 200927 | Exon 14 alterations | Direct sequencing | 3.3% (7/211) |

| Tong et al. 201634 | Exon 14 alterations | Direct sequencing | 2.6% (10/392) |

|

| |||

| MET-amplification | |||

| Cancer Genome Atlas. 201431 | Somatic copy-number | WES | 5.2% (12/230) |

| Capuzzo et al. 200948 | MET copy-number ≥5 (polysomy + gene amplification | FISH | 11.1% (48/435) |

| MET copy-number ≥5 (gene amplification only) | 4.1% (18/435) | ||

| Okuda et al. 200850 | MET copy-number >3 | qRT-PCR | 5.6% (12/213) |

| Tong et al. 201634 | MET/CEP7 ratio ≥5 | FISH | 1.0% (4/392) |

| Onozato et al. 200927 | MET amplification | qRT-PCR | 1.4% (2/148) |

| MET Splice mutations | Direct sequencing | 3.3% (7/211) | |

FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; MET, mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor; METex14, mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor exon 14; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; WES, whole-exome sequencing

METex14 alterations are mutually exclusive with other lung cancer drivers, suggesting they represent a true oncogenic driver state.29 In a study of 933 patients with nonsquamous NSCLC,30 no patients with METex14 alterations had activating mutations in KRAS, EGFR or ERBB2, or rearrangements involving ALK, ROS1 or RET.30 In contrast, METex14 alterations can overlap with other alterations such as MET and MDM2 amplification. METex14 alterations can co-occur with MET copy-number gain/amplification, with the frequency of overlap being heavily influenced by the definition of amplification used.34

While many cases of METex14 alterations are found in lung adenocarcinomas, these events have a much higher incidence in pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas. About 20–30% of sarcomatoid carcinomas harbor METex14 alterations.34, 36 In one series, these were more likely to be associated with sarcomatoid carcinomas with an adenocarcinoma component,36 suggesting the possibility of a shared tumor origin. The therapeutic implications of METex14 alterations in sarcomatoid carcinomas are discussed below.

METex14 alterations are likely to be highly predictive of response to MET inhibition (Table 2). Dramatic and durable partial responses (PRs) to crizotinib were first reported in mid-2015 in patients with advanced lung cancers with METex14 alterations.32 The same authors reported a complete metabolic (PERCIST) response to cabozantinib therapy (stable disease by RECIST). Durable PRs to capmatinib or crizotinib have been reported in patients with advanced METex14-altered lung cancers.29 Subsequent case reports have confirmed these observations using different MET TKIs and in all NSCLC histologies.30, 37–40

TABLE 2.

Case reports of NSCLCs with MET exon-14 alterations responding to MET inhibitors

| Reference | Age/sex | Smoking history | METex14 alteration | MET IHC | MET-amplification | Agent | Best response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awad et al. 201630 | 64 F | Never | Splice donor mutation | NA | Yes | Crizotinib | PR |

| Frampton et al. 201529 | 82 F | Former | Splice donor mutation | 3+ | Yes | Capmatinib | PR |

| Frampton et al. 201529 | 66 F | Former | Splice donor mutation | 3+ | Not tested | Capmatinib | PR |

| Jenkins et al. 201537 | 86 M | Never | Splice acceptor deletion | 2+ | NA | Crizotinib | PR |

| Jorge et al. 201538 | 68 F | Former | Splice donor mutation | NA | NA | Crizotinib | PR |

| Lee et al. 201540 | 61 M | Never | Splice donor deletion | NA | NA | Crizotinib | PR |

| Liu et al. 201536 | 74 F | Former | Splice site mutation | NA | NA | Crizotinib | PR |

| Mahjoubi et al. 201639 | 67 F | Never | Splice donor mutation | NA | NA | Crizotinib | PR |

| Mendenhall et al. 201572 | 76 F | Former | Splice donor mutation | NA | NA | Crizotinib | PR |

| Paik et al. 201532 | 65 M | Former | Splice donor mutation | NA | NA | Crizotinib | PR |

| Paik et al. 201532 | 78 M | Former | Splice donor deletion | 3+ | NA | Crizotinib | PR (lung) PD (liver) |

| Paik et al. 201532 | 80 F | Never | Splice donor mutation | 3+ | Yes | Cabozantinib | CR (PERCIST) |

| Paik et al. 201532 | 90 F | Never | Splice donor mutation | NA | NA | Crizotinib | PR |

| Waqar et al. 201573 | 71 M | Former | Splice donor mutation | NA | No | Crizotinib | PR |

CR, complete response; F, female; IHC, immunohistochemistry; M, male; MET, mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor; METex14, mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor exon 14; NA, not applicable/available; PERCIST, Positron Emission Tomography Response Criteria in Solid Tumors; PR, partial response

Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas were thought to be relatively refractory to cytotoxic chemotherapies however, a dramatic PR was reported in a patient with advanced pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma harboring both a METex14 alteration and MET amplification. No responses to an anti-MET or anti-HGF monoclonal antibody in a lung cancer patient with a METex14 alteration have been reported, although such a response is not unlikely given our knowledge of these tumors’ biology, coupled with preclinical data supporting the use of these agents.28

Reports of response to MET inhibitors have prompted drug development plans focused on molecular enrichment for METex14 alterations. The phase I trial that resulted in approval of crizotinib for ALK- and ROS1-rearranged lung cancers (NCT00585195) is currently treating advanced lung cancer patients with METex14 alterations in an enriched cohort.41 Of 18 response-evaluable patients, at the latest available data cutoff, 8 patients experienced a confirmed PR (overall response rate 44%, 95% CI: 22–69%) with tumor shrinkage in 14/18 patients.41 We look forward to studies of potential mechanisms of acquired resistance to MET TKIs, but already MET D1228N has been reported as a putative mechanism.42

MET-amplified lung cancers

MET amplification is thought to dysregulate MET pathway signaling via protein overexpression and constitutive kinase activation. Identification of MET copy-number gains in the setting of acquired resistance to EGFR TKI therapy in lung cancer stimulated interest in these alterations.

MET copy-number gains arise from two distinct processes: polysomy and amplification.43 High polysomy occurs when there are multiple copies of chromosome 7 in tumor cells, secondary to factors such as chromosomal duplication.44 True amplification occurs in the setting of focal or regional gene duplication, via processes such as breakage-fusion-bridge mechanisms.45 As opposed to polysomy, amplification is thought to represent a state of true biologic selection for MET-activation as an oncogenic driver. Additionally, each type of MET gene copy-number change represents a continuous variable. Placing a cut-point to define ‘positivity’ may dramatically alter the reported frequency, overlap with other NSCLC subtypes, and ultimately affect its potential to act as a predictive biomarker for benefit from MET inhibition.

Using FISH, the MET/CEP7 ratio can be used to distinguish between polysomy and true amplification. In polysomy, each copy of MET is associated with a corresponding centromere, preserving the MET/CEP7 ratio as copy-number increases.43 In true MET-amplification, copy-number increases without an increase in CEP7, and the MET/CEP7 ratio increases.43 Broad, hybrid-capture NGS assays are able to detect amplification events. Copy-number changes can be identified by comparing sequence coverage of targeted regions in tumors relative to a diploid normal sample, and select platforms have been validated against tumor samples that previously tested positive for amplification of other genes such as ERBB2 via FISH.46, 47 As with FISH, copy-number gains detected via NGS are reported as continuous variables, and cutoffs can vary significantly between assays. In contrast to FISH, NGS and anchored multiplex PCR may provide additional information on other, potentially clinically relevant, concurrent genomic alterations.33

No consensus on the definition of MET positivity based on gene copy-number has yet been reached. Examples of a positive MET FISH result include ≥5 MET signals per cell (Cappuzzo scoring system),48 and a MET/CEP7 ratio of ≥2 (PathVysion).34, 49 MET amplification has also been classified via the MET/CEP7 ratio as low (≥1.8, ≤2.2), intermediate (>2.2, <5), and high (≥5), summarized in Table 3. Variation of classification-thresholds between studies complicates comparisons of reported MET-amplification/copy-number gain relative to the underlying frequency, associated factors and outcomes from therapy, although more rigorous data are now emerging.11

TABLE 3.

MET/CEP7 ratio and classification of MET amplification (Garcia, L. University of Colorado, personal communication)

| MET/CEP7 ratio | MET amplification classification | Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

| <1.8 | Negative | 92.6 |

| ≥1.8–≤2.2 | Low | 3.6 |

| >2.2–<5.0 | Intermediate | 3.0 |

| ≥5.0 | High | 0.8 |

| Total | – | 100.0 |

CEP7, centromeric portion of chromosome 7; MET, mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor

The reported prevalence of de-novo MET amplification in NSCLC ranges from 1–5%, depending on the level of preselection, the assay, and the positivity cut-point used (Table 1).27, 29, 48, 50, 51 In adenocarcinoma, since most true oncogenic drivers are mutually exclusive, so called ‘oncogene overlap analysis’ was used in 1164 cases to see if there was a level of MET copy-number gain, using either the mean number of copies of MET/cell (which would include high polysomy cases) or the MET/CEP7 ratio, that could define a group where the degree of overlap with other known oncogenic drivers (EGFR, KRAS, ALK, ERBB2, BRAF, NRAS, ROS1, or RET) disappeared.52 Across all levels of mean MET/cell increase (low: ≥5, <6; intermediate: ≥6, <7; high ≥7) oncogene overlap occurred in 41–63% of cases. Similarly, using the MET/CEP7 ratio, at both low (≥1.8, ≤2.2) and intermediate (>2.2, <5) levels of MET-amplification, oncogene overlap occurred in 52% and 50% of cases, respectively. However, zero oncogene overlap was seen in the high MET amplification category (MET/CEP7 ≥5). Only this high-level amplification category was associated with a dramatic response rate to crizotinib. These data suggest that high MET copy-number (MET/CEP7 ratio ≥5) represents the best case for a true MET copy-number gain-dependent MET-driven state, whereas lower or different MET copy-number definitions of positivity may more likely represent MET as a coincident event.52

There are two important issues related to exploring MET amplification as a predictive biomarker for benefit from MET inhibition. The first is that MET/CEP7 ≥5 represented only 0.34% of adenocarcinomas in a large series,52 ~10% of the frequency of METex14 variants in the same population. The second is that the degree of benefit in this population independent of METex14 mutations remains under investigation. METex14 alterations harbor concurrent high-level MET copy-number gain in ~20% of cases, with the degree of overlap increasing (just as with other known oncogenes) as less stringent definitions of MET amplification are used.30, 32, 34 The case for METex14 variants to act as predictive biomarkers in the absence of MET amplification seems to have been made, as responses in this setting have been documented. Whether MET amplification is only a surrogate for some cases of METex14 (in which case testing should focus exclusively on the METex14 approach) or can truly function as an independent MET-addicted state capable of driving clinical responses without METex14 changes (requiring an all-inclusive testing approach for actionable abnormalities in lung cancer, in addition to METex14 testing) is undetermined. Therefore, testing for both MET amplification and METex14 changes should be conducted in all MET-TKI trials, then used to retrospectively investigate differential responses based on MET amplification status. As both MDM2 and CDK4 amplification are strongly coincident with METex14 alterations,29 a similar approach could be taken to investigate MET-TKI response with concurrent MDM2 and CDK4 amplification.

The first report of a response to MET inhibition in a patient with a de-novo MET-amplified lung cancer was published in 2011. The patient was a 77-year-old female with a 45 pack-year history of smoking and advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Her cancer had high-level MET amplification via FISH (MET/CEP7 ratio >5). She was treated on the phase I trial of crizotinib (NCT00585195) and achieved a dramatic and durable PR.53 Preliminary results were presented in 2014and showed PRs in 1/6 (16.7%) patients with intermediate-level MET amplification (MET/CEP7 >2.2, <5) and in 3/6 (50%) patients with high-level MET amplification (MET/CEP7 ≥5).54 Responses were not seen in patients with low-level MET amplification (MET/CEP7 ≥1.8 to ≤2.2).

MET as a co-driver in NSCLC

There is significant cross-talk between the MET pathway and other signaling pathways. Historically, many investigators have chosen to explore combination MET- and EGFR-inhibitor therapy in clinical trials of patients with NSCLCs (Table 4). This strategy was partially based on the synergy of MET and EGFR in driving oncogenesis in both EGFR wild-type lung and mutant lung cancer models in the setting of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs.55, 56 In 2007, MET amplification was found to be associated with acquired resistance to first-generation EGFR TKIs.57 While the majority of EGFR-mutant lung cancers develop resistance to EGFR TKI therapy via acquired T790M mutation, activation of the MET pathway as a bypass tract represents a distinct acquired resistance mechanism driven by ERBB3-dependent PI3K pathway activation. MET exon 14 alterations are generally thought to be mutually exclusive with other major lung cancer drivers and have not been associated with acquired resistance to EGFR TKI therapy in EGFR-mutant lung cancers.27

TABLE 4.

Clinical experience with select MET- and HGF-directed targeted therapies

| Agent | Target(s) | Patients | Phase | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multikinase MET TKIs | ||||

| Crizotinib | MET, ALK, ROS1 |

Crizotinib monotherapy Patients with MET exon 14-altered and MET-amplified NSCLC |

I/II | MET exon 14-altered NSCLC: responses observed in 8/18 (44%) patients; MET-Amplified NSCLC: At data cut-off, partial responses were observed in 1/6 (16.7%) patients with a MET/CEP7 ratio >2.2–<5 and in 3/6 (50%) patients with a MET/CEP7 ratio ≥554 |

| Cabozantinib | MET, RET, ROS1, VEGFR2 |

Erlotinib +/− cabozantinib Patients with non-squamous NSCLC and no EGFR mutation. MET expression assessed by IHC |

II | Overall improvement in PFS with cabozantinib but MET IHC score was not predictive.74 |

|

| ||||

| MET-Selective TKIs | ||||

| Tivantinib | MET |

Erlotinib +/− tivantinib MARQUEE: Western cohort of patients with non-squamous NSCLC. Not selected based on MET analysis |

III | Tivantinib was not associated with any improvement in OS, although PFS was increased in the tivantinib group compared with erlotinib alone.65 |

|

Erlotinib +/− tivantinib ATTENTION: East Asian cohort of patients with non-squamous NSCLC. Not selected based on MET analysis |

III | Tivantinib was not associated with any improvement in OS, although PFS was increased in the tivantinib group compared with erlotinib alone. Trial terminated early due to an increase of interstitial lung disease in the tivantinib group.17 | ||

| Capmatinib | MET |

Gefitinib + capmatinib Patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC, refractory to EGFR-TKIs, and MET amplification or MET overexpression |

Ib/II | Partial responses in 15% [6/41] of patients, all with either high MET amplification or MET overexpression15 |

|

| ||||

| Anti-MET Monoclonal Antibody | ||||

| Onartuzumab | MET |

Erlotinib +/− onartuzumab Patients with stage IIIB or IV NSCLC. MET expression evaluated at baseline |

II | Onartuzumab plus erlotinib did not show an OS advantage, but the MET-positive subgroup did.20 |

|

Erlotinib +/− onartuzumab Patients with previously treated MET-positive stage IIIB or IV NSCLC |

III | Stopped for futility as there was no improvement in OS, PFS or ORR.19 | ||

| Emibetuzumab (LY2875358) | MET |

Emibetuzumab monotherapy Patients with locally advanced or metastatic CRPC with bone metastasis, RCC, NSCLC, and HCC. Patients with RCC, NSCLC, and HCC were required to have ≥50% of tumor cells to be ≥2+ for MET expression by IHC |

I | In patients with NSCLC, the disease control rate (PR + SD) was 26% (5/19), and the median duration of disease stabilization was 3.9 months (range 2.5–6.4) in NSCLC.18 |

|

| ||||

| Anti-HGF Monoclonal Antibody | ||||

| Ficlatuzumab | HGF |

Gefitinib +/− ficlatuzumab Asian patients with stage IIIB or IV pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Patients were not selected based on MET analysis |

II | Failed to demonstrate significant improvement in PFS and overall response.21 |

| Rilotumumab | HGF |

Erlotinib + rilotumumab Patients with recurrent or progressive NSCLC. Not selected based on MET analysis |

II | Ongoing (NCT01233687). |

+/−, with or without; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CEP7, centromeric portion of chromosome 7; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FLT3, Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MET, mesenchymal epithelial transition receptor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; RET, ret proto-oncogene; RON, Recepteur d’Origine Nantais; SD, stable disease; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Unfortunately, significant variation in preselection criteria for defining those potentially sensitive to EGFR and MET inhibition has contributed to some confusion over the results of trials combining EGFR and MET inhibition in NSCLC.

Combination trials not focused on EGFR-mutant patients

Increased expression of MET alone is sufficient to induce oncogenic transformation in vitro and in vivo.58, 59 While overexpression of both MET and HGF have been identified in unselected NSCLC specimens, the role of increased expression alone as a clinically-relevant oncogenic driver has come into question.5, 6 The prevalence of MET overexpression in unselected NSCLCs ranges from 15 to 70%.60–63 This frequency depends on the antibody, assay, and the positivity cut-point. While MET protein expression has been associated with poor prognostic outcomes in lung cancer,60, 64 it has thus far served as a poor predictive biomarker of response to targeted therapy.

Interest in the treatment of patients with MET overexpressing lung cancers was initially piqued by a subset analysis of a phase II combination trial of erlotinib and onartuzumab.20 In this study, unselected second-line advanced NSCLC patients were randomized to erlotinib ± onartuzumab. While the co-primary endpoints of OS (HR 0.80, p=0.34) and PFS (HR 1.09, p=0.69) were not met in the overall population, patients whose tumors expressed higher levels of MET (IHC 2–3+) showed an improvement in both PFS (HR 0.53, p=0.04) and OS (HR 0.37, p<0.05).20

Disappointingly, a subsequent phase III trial randomizing 499 advanced NSCLC patients with MET overexpressing tumors (IHC 2–3+) to erlotinib ± onartuzumab was terminated early due to futility.19 The primary endpoint of OS was not different between groups (HR 1.27, p=0.07).19 Median OS was numerically decreased in patients that received combination therapy, suggesting the possibility of harm.19

Two phase III combination studies of tivantinib, which had reported anti-MET activity, that treated largely unselected NSCLC patients did not meet their primary endpoint. The ATTENTION trial randomized 307 patients with advanced, EGFR wild-type, non-squamous NSCLC to erlotinib with or without tivantinib. While the study was terminated early secondary to an increased incidence of interstitial lung disease in the tivantinib arm, the primary endpoint of OS was not significantly different between groups (HR 0.89, p=0.43).17 The MARQUEE trial randomized 1,048 patients with advanced, non-squamous NSCLC to erlotinib ± tivantinib. This trial was terminated early due to an interim analysis revealing futility, and the primary endpoint of OS did not differ between groups (HR 0.98, p=0.81).65 While the secondary endpoint of PFS was improved by the combination in both trials, the absolute difference compared to single-agent erlotinib was small.65 Of note, tivantinib is thought to potentially function as a mitotic spindle poison.66

Recently, a phase II study randomizing 118 advanced, EGFR wild-type, NSCLC patients to erlotinib, cabozantinib, or both in combination reached its primary endpoint of PFS (HR 0.38, p<0.05 for cabozantinib vs erlotinib; HR 0.35, p<0.05 for combination vs erlotinib). Unlike the MET-selective inhibitor tivantinib that was tested in the ATTENTION and MARQUEE studies, cabozantinib is a multikinase inhibitor with activity against several other potentially sensitive subgroups that may have been contained within this trial population, including both ROS1- and RET-rearranged lung cancers. This cohort of patients did not undergo comprehensive molecular profiling to rule out the presence of these alterations or other events, such as METex14 alterations. The contribution of these potentially undetected cases to these results remains unclear.

MET inhibition in EGFR-mutant patients

The prevalence of MET amplification in EGFR-mutant lung cancers with acquired resistance to EGFR TKI therapy was initially reported at 15–20%.57, 67 A subsequent series noted a lower prevalence at 5%, and found that MET amplification overlapped with other resistance mechanisms such as EGFR T790M acquisition or small cell transformation.68 Unsurprisingly, the acquisition of MET amplification has also been reported as a mechanism of resistance to third generation EGFR TKI therapy in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer patients.69

Clinical trials preselected or enriched for EGFR-mutant NSCLC exploring combined MET and EGFR inhibition have either focused on the EGFR TKI-naive setting as a means of preventing MET-driven resistance, or the acquired resistance setting, with varying degrees of preselection to identify a MET-co-driven state at the time of its emergence. The former approach does not depend on having specific biomarkers of MET activation. As an EGFR TKI is associated with significant benefit in an EGFR-mutant TKI naive population, clinical investigations must rely on randomized data to make the case for combination therapy being superior to monotherapy with an EGFR TKI. In addition, this approach, with PFS as the primary endpoint, is inherently dependent on the expected underlying frequency of MET activation that would otherwise emerge in order to size the study to detect a change compared to the benefit from an EGFR TKI alone. The lower the frequency of MET as a predicted mechanism of acquired resistance, the larger the study must be to prove the combination adds unequivocal benefit. In a phase II trial comparing emibetuzumab ± erlotinib, the objective response rate (ORR) was higher in both the combination and monotherapy arms, 3.8% and 4.8%, respectively, for patients with ≥ 60% of MET positive cells by IHC (n=74) than for patients with ≥ 10% positive cells (n=89) where ORR was 3.0% in the combination arm and 4.3% in the monotherapy arm.70 In the acquired resistance setting, the same challenges associated with defining the appropriate method and positivity cut point for identifying MET gene copy-number gain as a primary driver apply to defining MET positivity as a co-driver state. Data converging with the primary driver literature recently emerged from a small phase II study in EGFR-mutant patients with acquired resistance to an EGFR TKI who were then treated with the combination of gefitinib and capmatinib. When new biopsies at the time of acquired resistance were analyzed, the response rate to the combination was 40% among those with a MET copy-number ≥5 (ratio was not reported), but zero among those with copy-number <5.15 Clinical trials focusing on combination MET and EGFR inhibitor therapy for patients with acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs employing differing degrees of MET preselection are ongoing.71

Conclusions

While research into the MET pathway as a driver of oncogenesis has stretched well over three decades, advances in technology and appropriate patient selection have reinvigorated the search for an effective targeted therapeutic for lung cancers harboring METex14 alterations and/or MET amplification as their primary oncogenic driver. Attempts to define the criteria for optimal use of a MET and EGFR inhibitor combination where MET acts as a targetable co-driver, particularly in EGFR-mutant patients, continue. Ongoing and future drug development plans with a strong focus on molecular enrichment are likely to succeed in this arena. Both patients and providers look forward to eventual regulatory approval.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Ash Dunne at inScience Communications (Chester, UK), Wendy Sacks and Thierry Deltheil at ACUMED® (New York, NY and Tytherington, UK) and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Alexander Drilon: None

Federico Capuzzo: None

Sai Hong Ignatius Ou: Consultant for Pfizer, Roche/Genentech/Chugai, AstraZeneca, Boehringer

Ingelheim; Speaker honorarium for Roche/Genentech, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim

D. Ross Camidge: Honoraria from Pfizer and Eli Lilly

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167–2177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drilon A, CSS, RS, et al. Phase II study of cabozantinib for patients with advanced RET-rearranged lung cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33 (suppl; abstr 8007) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farago AF, Le LP, Zheng Z, et al. Durable Clinical Response to Entrectinib in NTRK1-Rearranged Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1670–1674. doi: 10.1097/01.JTO.0000473485.38553.f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ichimura E, Maeshima A, Nakajima T, et al. Expression of c-met/HGF receptor in human non-small cell lung carcinomas in vitro and in vivo and its prognostic significance. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1996;87:1063–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1996.tb03111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegfried JM, Weissfeld LA, Luketich JD, et al. The clinical significance of hepatocyte growth factor for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1915–1918. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y. The human hepatocyte growth factor receptor gene: complete structural organization and promoter characterization. Gene. 1998;215:159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skead G, Govender D. Gene of the month: MET. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:405–409. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Organ SL, Tsao MS. An overview of the c-MET signaling pathway. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2011;3:S7–S19. doi: 10.1177/1758834011422556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comoglio PM, Giordano S, Trusolino L. Drug development of MET inhibitors: targeting oncogene addiction and expedience. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:504–516. doi: 10.1038/nrd2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finocchiaro G, Toschi L, Gianoncelli L, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of MET deregulation in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:83. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.03.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui JJ. Targeting receptor tyrosine kinase MET in cancer: small molecule inhibitors and clinical progress. J Med Chem. 2014;57:4427–4453. doi: 10.1021/jm401427c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peschard P, Fournier TM, Lamorte L, et al. Mutation of the c-Cbl TKB domain binding site on the Met receptor tyrosine kinase converts it into a transforming protein. Mol Cell. 2001;8:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stransky N, Cerami E, Schalm S, et al. The landscape of kinase fusions in cancer. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4846. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y-L, Yang JC-H, Kim D-W, et al. Safety and efficacy of INC280 in combination with gefitinib (gef) in patients with EGFR-mutated (mut), MET-positive NSCLC: A single-arm phase lb/ll study. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2014;32:8017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bladt F, Friese-Hamim M, Ihling C, et al. The c-Met Inhibitor MSC2156119J Effectively Inhibits Tumor Growth in Liver Cancer Models. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6:1736–1752. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshioka H, Azuma K, Yamamoto N, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of erlotinib with or without a c-Met inhibitor tivantinib (ARQ 197) in Asian patients with previously treated stage IIIB/IV nonsquamous nonsmall-cell lung cancer harboring wild-type epidermal growth factor receptor (ATTENTION study) Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2066–2072. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banck MS, Chugh R, Natale RB, et al. Abstract A55: Phase 1 results of emibetuzumab (LY2875358), a bivalent MET antibody, in patients with advanced castration-resistant prostate cancer, and MET positive renal cell carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [abstract]. Mol Cancer Ther; Proceedings of the AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference: Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics; 2015 Nov 5–9; Boston, MA. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; 2015. p. A55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spigel DR, Edelman MJ, O’Byrne K, et al. Onartuzumab plus erlotinib versus erlotinib in previously treated stage IIIb or IV NSCLC: Results from the pivotal phase III randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled METLung (OAM4971g) global trial. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2014;32:8000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spigel DR, Ervin TJ, Ramlau RA, et al. Randomized phase II trial of onartuzumab in combination with erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4105–4114. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mok TSK, Park K, Geater SL, et al. A randomized phase (Ph) 2 study with exploratory biomarker analysis of ficlatuzumab (F) a humanized hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) inhibitory MAB in combination with gefitinib (G) versus G in Asian patients (pts) with lung adenocarcinoma (LA) Ann Oncol. 2012;23:ix399, 1198P. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt L, Duh FM, Chen F, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1997;16:68–73. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnaswamy S, Kanteti R, Duke-Cohan JS, et al. Ethnic differences and functional analysis of MET mutations in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5714–5723. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong-Beltran M, Stamos J, Wickramasinghe D. The Sema domain of Met is necessary for receptor dimerization and activation. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma PC, Kijima T, Maulik G, et al. c-MET mutational analysis in small cell lung cancer: novel juxtamembrane domain mutations regulating cytoskeletal functions. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6272–6281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma PC, Jagadeeswaran R, Jagadeesh S, et al. Functional expression and mutations of c-Met and its therapeutic inhibition with SU11274 and small interfering RNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1479–1488. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onozato R, Kosaka T, Kuwano H, et al. Activation of MET by gene amplification or by splice mutations deleting the juxtamembrane domain in primary resected lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:5–11. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181913e0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong-Beltran M, Seshagiri S, Zha J, et al. Somatic mutations lead to an oncogenic deletion of met in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:283–289. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frampton GM, Ali SM, Rosenzweig M, et al. Activation of MET via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to MET inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:850–859. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Awad MM, Oxnard GR, Jackman DM, et al. MET exon 14 mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer are associated with advanced age and stage-dependent MET genomic amplification and c-Met overexpression. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:721–730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paik PK, Drilon A, Fan PD, et al. Response to MET inhibitors in patients with stage IV lung adenocarcinomas harboring MET mutations causing exon 14 skipping. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:842–849. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng Z, Liebers M, Zhelyazkova B, et al. Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat Med. 2014;20:1479–1484. doi: 10.1038/nm.3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong JH, Yeung SF, Chan AW, et al. MET amplification and exon 14 splice site mutation define unique molecular subgroups of Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma with poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2016 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw AT, Engelman JA. ALK in lung cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1105–1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu X, Jia Y, Stoopler MB, et al. Next-Generation Sequencing of Pulmonary Sarcomatoid Carcinoma Reveals High Frequency of Actionable MET Gene Mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:794–802. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jenkins RW, Oxnard GR, Elkin S, et al. Response to crizotinib in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma harboring a MET splice site mutation. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015;16:e101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorge SE, Schulman S, Freed JA, et al. Responses to the multi-targeted MET/ALK/ROS1 inhibitor crizotinib and co-occurring mutations in lung adenocarcinomas with MET amplification or MET exon 14 skipping mutation. Lung Cancer. 2015;90:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahjoubi L, Gazzah A, Besse B, et al. A never-smoker lung adenocarcinoma patient with a MET exon 14 mutation (D1028N) and a rapid partial response after crizotinib. Invest New Drugs. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10637-016-0332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee C, Usenko D, Frampton GM, et al. MET 14 Deletion in Sarcomatoid Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Detected by Next-Generation Sequencing and Successfully Treated with a MET Inhibitor. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:e113–114. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drilon A, Camidge DR, Ou SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of crizotinib in patients (pts) with advanced MET exon 14-altered non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 (suppl; abstr 108) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heist RS, Sequist LV, Borger D, et al. Acquired Resistance to Crizotinib in NSCLC with MET Exon 14 Skipping. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1242–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawakami H, Okamoto I, Okamoto W, et al. Targeting MET amplification as a new oncogenic driver. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6:1540–1552. doi: 10.3390/cancers6031540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albertson DG, Collins C, McCormick F, et al. Chromosome aberrations in solid tumors. Nat Genet. 2003;34:369–376. doi: 10.1038/ng1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hellman A, Zlotorynski E, Scherer SW, et al. A role for common fragile site induction in amplification of human oncogenes. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng DT, Mitchell T, Zehir A, et al. MSK-IMPACT: A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1023–1031. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cappuzzo F, Marchetti A, Skokan M, et al. Increased MET gene copy number negatively affects survival of surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1667–1674. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka A, Sueoka-Aragane N, Nakamura T, et al. Co-existence of positive MET FISH status with EGFR mutations signifies poor prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Lung Cancer. 2012;75:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okuda K, Sasaki H, Yukiue H, et al. Met gene copy number predicts the prognosis for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2280–2285. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frampton GM, Ali SM, Rosenzweig M, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) of advanced cancers to identify MET exon 14 alterations that confer sensitivity to MET inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33 (suppl; abstr 11007) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noonan SA, Berry L, Lu X, et al. Identifying the appropriate FISH criteria for defining MET copy number driven lung adenocarcinoma through oncogene overlap analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1293–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ou SH, Kwak EL, Siwak-Tapp C, et al. Activity of crizotinib (PF02341066), a dual mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor, in a non-small cell lung cancer patient with de novo MET amplification. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:942–946. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821528d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Camidge DR, Ou SH, Shapiro G, et al. Efficacy and safety of crizotinib in patients with advanced c-MET-amplified non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32 (suppl; abstr 9070) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puri N, Salgia R. Synergism of EGFR and c-Met pathways, cross-talk and inhibition, in non-small cell lung cancer. J Carcinog. 2008;7:9. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.44372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsubara D, Ishikawa S, Sachiko O, et al. Co-activation of epidermal growth factor receptor and c-MET defines a distinct subset of lung adenocarcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2191–2204. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patane S, Avnet S, Coltella N, et al. MET overexpression turns human primary osteoblasts into osteosarcomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4750–4757. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang R, Ferrell LD, Faouzi S, et al. Activation of the Met receptor by cell attachment induces and sustains hepatocellular carcinomas in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1023–1034. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park S, Choi YL, Sung CO, et al. High MET copy number and MET overexpression: poor outcome in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27:197–207. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma PC, Tretiakova MS, MacKinnon AC, et al. Expression and mutational analysis of MET in human solid cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:1025–1037. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsao MS, Yang Y, Marcus A, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor is predominantly expressed by the carcinoma cells in non-small-cell lung cancer. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:57–65. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.21133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsuta K, Kozu Y, Mimae T, et al. c-MET/phospho-MET protein expression and MET gene copy number in non-small cell lung carcinomas. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:331–339. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318241655f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dimou A, Non L, Chae YK, et al. MET gene copy number predicts worse overall survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scagliotti G, von Pawel J, Novello S, et al. Phase III multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tivantinib (ARQ 197) plus erlotinib versus erlotinib alone in previously treated patients with locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2667–2674. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.7317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katayama R, Aoyama A, Yamori T, et al. Cytotoxic activity of tivantinib (ARQ 197) is not due solely to c-MET inhibition. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3087–3096. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turke AB, Zejnullahu K, Wu YL, et al. Preexistence and clonal selection of MET amplification in EGFR mutant NSCLC. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2240–2247. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Planchard D, Loriot Y, Andre F, et al. EGFR-independent mechanisms of acquired resistance to AZD9291 in EGFR T790M-positive NSCLC patients. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2073–2078. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Camidge DR, Moran T, Demedts I, et al. A randomized, open-label, phase 2 study of emibetuzumab plus erlotinib (LY+E) and emibetuzumab monotherapy (LY) in patietns with acquired resistance to erlotinib and MET diagnostic positive (MET Dx+) metastatic NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34 doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2022.03.003. abstr 9070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thress KS, Paweletz CP, Felip E, et al. Acquired EGFR C797S mutation mediates resistance to AZD9291 in non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR T790M. Nat Med. 2015;21:560–562. doi: 10.1038/nm.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]