Abstract

One of the exciting advances in modern medicine and life science is cell-based neurovascular regeneration of damaged brain tissues and repair of neuronal structures. The progress in stem cell biology and creation of adult induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells has significantly improved basic and pre-clinical research in disease mechanisms and generated enthusiasm for potential applications in the treatment of central nervous system (CNS) diseases including stroke. Endogenous neural stem cells and cultured stem cells are capable of self-renewal and give rise to virtually all types of cells essential for the makeup of neuronal structures. Meanwhile, stem cells and neural progenitor cells are well-known for their potential for trophic support after transplantation into the ischemic brain. Thus, stem cell-based therapies provide an attractive future for protecting and repairing damaged brain tissues after injury and in various disease states. Moreover, basic research on naïve and differentiated stem cells including iPS cells has markedly improved our understanding of cellular and molecular mechanisms of neurological disorders, and provides a platform for the discovery of novel drug targets. The latest advances indicate that combinatorial approaches using cell based therapy with additional treatments such as protective reagents, preconditioning strategies and rehabilitation therapy can significantly improve therapeutic benefits. In this review, we will discuss the characteristics of cell therapy in different ischemic models and the application of stem cells and progenitor cells as regenerative medicine for the treatment of stroke.

Keywords: Stem cells, Transplantation, Regeneration, Survival, Differentiation, Stroke, Pre-conditioning, Trophic support

Introduction

Stem cell therapy has been considered in basic and clinical stroke research fields to be a promising regenerative medical treatment and a more promising approach for brain injury induced by different types of strokes. Stem cells (either endogenous neural stem cells or induced pluripotent stem cells e.g. iPS cells) have the potential of replacing damaged cells in the brain. Cell replacement strategies have been proposed and tested in many stroke models across decades of research in animal models. In addition, multipotent and pluripotent stem cells have shown beneficial paracrine effects, which can reduce cell death and provide growth/trophic support to host cells and regenerative activities in the host brain.

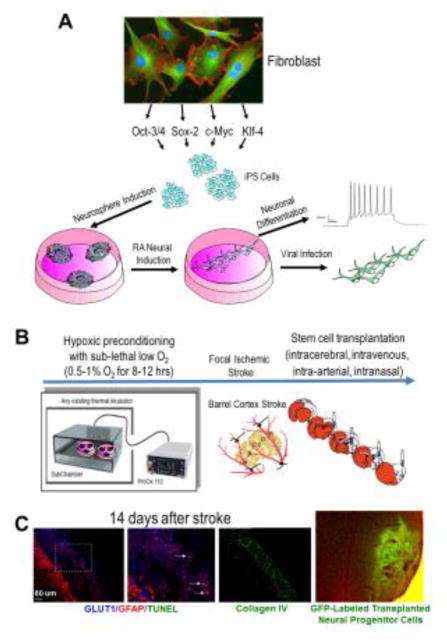

Induction of iPS cells from somatic cells (e.g. fibroblasts) with transcriptional factors (Oct-3/4, Sox-2, c-Myc and Klf-4) has shown promising translational potential. Similar to embryonic stem (ES) cells, iPS cells can be expanded in vitro and induced into neurospheres, neural progenitors, and mature neurons. Neuronally-differentiating ES/iPS cells and ES/iPS-derived neural progenitors have been extensively tested in transplantation therapies for the treatment of stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), spinal cord injury (SCI) and neurodegenerative diseases. It is generally agreed that transplanted cells may provide morphological and functional benefits via multiple mechanisms including, but not limited to, cell replacement, trophic support, immunosuppression/anti-inflammation, stimulation of endogenous signaling for neural plasticity and regeneration, and regulatory interactions with endogenous cells such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Horie et al., 2015; McDonald and Howard, 2002; Volpe et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2013). Based on promising results and better understanding on the therapeutic mechanisms, translational studies and clinical trials using stem cells including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), umbilical cord stem cells (UCSCs), adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs), iPS cells, and many others are being tested for clinical applications.

In this review, we will focus on neural progenitor cells derived from ES, adult brain and iPS cells, and widely tested MSCs. Their mechanism of action and beneficial effects after stroke in animal models and human studies will be reviewed. Regarding transplantation therapy, we will discuss the efforts to improve the survival, neuronal differentiation and therapeutic potential of transplanted cells, post-transplantation cell distribution, and effects related to repairing the neurovascular unit. Cell delivery methods will be discussed highlighting the recent advances in non-invasive intranasal delivery of cells. We will also introduce functional and behavioral improvements after stem cell transplantation therapy.

Regenerative Medicine for the Treatment of Stroke

Stroke is the fifth leading cause of death and the number one cause of disability in the adult population in the United States (Mozaffarian et al., 2015). With an average of one victim every 40 seconds, almost 795,000 individuals experience a stroke every year in the United States, accounting for approximately one out of every 18 deaths (Mozaffarian et al., 2015; Roger et al., 2012). Of all stroke cases, 87% are ischemic in nature and the rest are hemorrhagic. In ischemic stroke, a clot occludes a brain vessel (most commonly the middle cerebral artery or its branches) and blood flow to the brain region supplied by that vessel is ceased, causing a cascade of pathological events associated with energy failure, acidosis, excessive glutamate release, elevated intracellular Ca2+ levels, generation of free radicals (especially after reperfusion), blood-brain-barrier (BBB) disruption, inflammation and eventually massive excitotoxic cell death composed of necrosis, apoptosis, autophagy and likely concurrent mixed forms of cell death involving hybrid mechanisms (Durukan and Tatlisumak, 2007; Li et al., 2013a; Puyal et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2002). Hemorrhagic stroke, on the other hand, occurs when a blood vessel ruptures in the brain leading to intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) (Ferro, 2006). ICH, with the associated edema, makes the outcome of hemorrhagic stroke more serious than ischemic stroke. Approximately 10% of ischemic stroke victims and 38% of hemorrhagic stroke victims die within 30 days.

Despite an estimated cost of more than 70 billion dollars in 2010 (Roger et al.), stroke therapy remains very limited and dependent predominantly on supportive therapies. The only FDA-approved treatment for acute stroke patients is tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA). t-PA administered within the 4.5-hr treatment window breaks down the vessel clot, allowing reperfusion of the infarcted/penumbral area. Late t-PA administration, can cause intracranial hemorrhage and is thus contraindicated in hemorrhagic stroke. As such, t-PA is applicable for only about 2% of stroke patients who meet the criteria for t-PA treatment. Evidently, there is a critical and urgent need for effective therapies for acute as well as chronic stroke patients (Wahlgren et al., 2008).

Many drugs that show significant neuroprotection in animal models have failed to replicate in human clinical trials. Erythropoietin (EPO), for example, has shown significant neuroprotection in animal models of stroke (Bernaudin et al., 1999; Keogh et al., 2007; Leist et al., 2004; Li et al., 2007a; Li et al., 2007b; Prass et al., 2003; Tsai et al., 2006) and has even shown positive protection in a small clinical trial where t-PA was not used (Ehrenreich et al., 2002). However, it failed to improve outcomes and may have detrimental effects in patients receiving systemic thrombolysis (Ehrenreich et al., 2009). Mild and moderate hypothermia (therapeutic hypothermia) has provided significant neuroprotection in animal models of stroke (van der Worp et al., 2007). In contrast, therapeutic hypothermia is considered one of very few therapies that had promising potential as a clinical treatment for stroke patients, based on consistent beneficial effects observed in animal models of ischemic and hemorrhage stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Benefits have also been replicated in clinical settings for the treatment of heart ischemia after cardiovascular arrest, term neonates after hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and children with TBI (Jeon, 2014; Lampe and Becker, 2011; Luehr and Etz, 2014; Pietrini et al., 2012; Tissier et al., 2012).

Stem Cells Are Pluripotent/Multipotent Cells Capable of Tissue Repair

Emerging research interests have been focused on protective and regenerative strategies using stem cells and neural progenitors cells in the sub-acute and chronic phases after stroke. Stem cells are defined as cells which can both self-renew and differentiate into other cell types. Pluripotent stem cells, such as ES and iPS cells, can differentiate into any cell type of the three germ layers. In contrast, multipotent stem cells, such as hematopoietic stem cells, have a more lineage-restricted differentiation potential. Undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells can theoretically proliferate indefinitely in vitro, avoiding the senescence observed in cultures of adult multipotent stem cells (Gadalla et al., 2015).

Since their first isolation in 1998 by Dr. Thomson (Thomson et al., 1998), storms of ethical disputes have arisen around human ES cells. Due to the fact that they are derived from the inner cell mass of human blastocysts, human ES cells have raised many ethical concerns. Research progress and funding for human ES cells have been significantly hampered and thus, mainstream stem cell research has turned to alternative non-blastocyst derived cell sources. Along these same lines, different cocktails of transcriptions factors and small molecules have been developed whose expression or addition of various gene products can induce a pluripotent state in terminally differentiated somatic cells such as fibroblasts (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Yu et al., 2007).

Ethical concerns and the fear of rejection when using allogeneic cells have prevented clinical trials using ES cells, but the introduction of iPS cells has spurred research into the personalized use of pluripotent cells as a therapy for neurodegenerative disorders (Crook et al., 2015; Inoue et al., 2014). These induced pluripotent cells can differentiate into cell types of the three germ layers. Recently, novel protocols have been developed for creating neurons or neural precursors directly from fibroblasts, astrocytes or other terminally differentiated cells while avoiding a pluripotent cell state (Caiazzo et al.; Lujan et al., 2012; Marro et al., 2011; Pfisterer et al.; Vierbuchen et al.).

Stem cell transplantation has proven to be beneficial in injury models such as myocardial infarction and heart failure, with promising work in animal models translating to success in human clinical trials (Lee and Terracciano; Wollert and Drexler; Yin et al., 2014). In this review, we use the words “stem cells transplantation” to refer to all cell transplantation using stem cells and stem cell-derived neural progenitor cells. In fact, undifferentiated pluripotent cells such as ES cells are not used directly for transplantation because of their high risk of tumorigenesis. Meanwhile, transplantation of multipotent bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) has been extensively evaluated for tumorigenesis but no tumor formation has been observed using these cells.

The clinical use of BMSCs in neurologic injury models, such as spinal cord injuries (Watanabe et al., 2015; Yoon et al., 2007) and neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis (Ghobrial et al., 2014; Su et al., 2006), have demonstrated beneficial effects. It is unclear whether the observed improvements arise from cell engraftment or the replacement of damaged tissues. Considerable evidence has shown that bone marrow derived stem cells release trophic factors that show pro-survival and pro-regeneration effects in ischemic regions and promote endogenous repair mechanisms, particularly with regard to angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Furthermore, tissue engraftment in Parkinson’s disease has provided a proof-of-concept for cell replacement (Hallett et al., 2014; Lindvall and Kokaia, 2009), leading researchers to believe that stem cell therapies can eventually be used to replace damaged tissue resulting from neurological injuries and disorders.

In rodent models of focal ischemic stroke, endogenous neural stem cells in the sub-ventricular zone (SVZ) are recruited to the infarct site and form newborn neurons (Fig. 1). However, the efficiency of this endogenous repair mechanism is very low and the number of new cells that can survive and differentiate into mature neurons is insufficient for effective repair of damaged brain tissue. Neural stem cells (NSCs) can be isolated from the adult brain and after proliferation and neural differentiation under culture conditions, differentiated neural progenitor cells (NPCs) can be transplanted into the ischemic brain (Fig. 1). These transplanted cells can differentiate into neural and vascular cells and, by secreting trophic factors, reduce cell death and increase endogenous neurogenesis and angiogenesis (Hess and Borlongan, 2008; Wei et al., 2005b; Yu and Silva, 2008). Cells derived from the bone marrow (Chopp and Li, 2002) or umbilical cord blood (Taguchi et al., 2004; Vendrame et al., 2004) have also been used in rodent models of stroke. Improvements observed in such studies seem to have come primarily from trophic effects or enhancement of endogenous regeneration rather than replacement of damaged neuronal tissue. This idea is supported by the fact that functional improvements occur even when the homing of intravenously infused BMSCs is very low (~1%) so it appeared that cells did not need to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to provide beneficial effects (Borlongan et al., 2004).

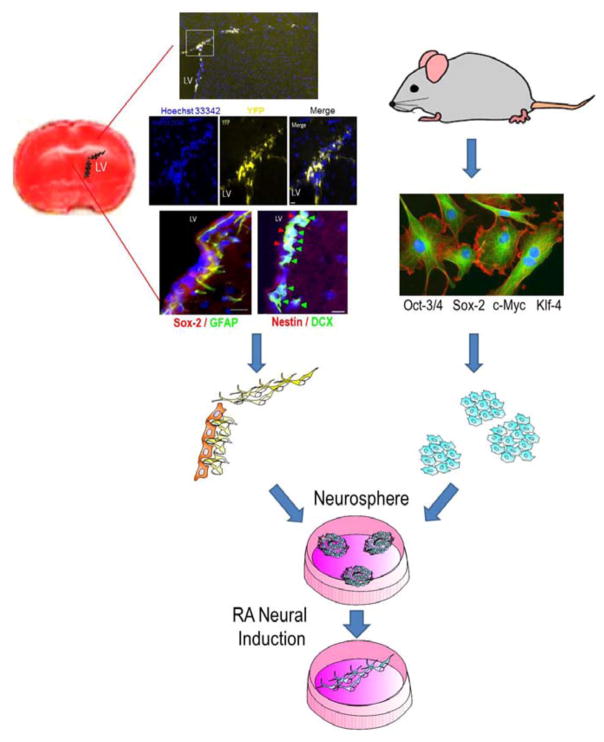

Figure 1. Neural stem cells from the SVZ and induced pluripotent stem cells from somatic cells.

The brain coronal section with TTC staining (red) shows the SVZ region. Immunohistochemical images show multiple markers for neural stem cells in the lateral ventricle SVZ 14 days after an ischemic insult. Using Nestin-Cre-ERT2/Rosa-YFP transgenic mice, the YFP+ cells indicate neural stem cells from the SVZ. Neural progenitors were DCX+ and Nestin+ while neural stem cells were GFAP+ and SOX-2+. Hoechst staining (blue) shows cell nuclei in the lateral ventricle SVZ. These neural stem/progenitors cells can be isolated, cultured and differentiated into neurons. Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells can be induced from rodents or humans using a set of reprogramming factors such as Oct-3/4, Sox2, cMyc, and Klf4. iPS cells can also be expanded and differentiated into different cell types including neurons.

Neural precursor cells that have been used in rodent models include conditionally immortalized cell lines derived from human fetal tissue (Pollock et al., 2006; Stevanato et al., 2009), carcinomas (Bliss et al., 2006; Hara et al., 2008), fetal neuronal stem cells (Zhang et al., 2009a), mouse neural precursors derived from the post-stroke cortex (Nakagomi et al., 2009), and precursors derived from mouse (Theus et al., 2008a; Wei et al., 2005; Yanagisawa et al., 2006) or human (Daadi et al., 2008b; Kim et al., 2007b) embryonic stem cells. Undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells are normally treated with a neural induction protocol before transplantation to gain cell lineage direction as well as reduce the risk of tumorigenesis (Newman et al., 2005). After neural induction, neural progenitor cells are either injected into the circulation (intravenously or intra-arterially) or directly into the ischemic brain (intracerebrally, intracranially, or intranasally) and have been shown to improve functional outcomes in rodent models of stroke.

Neuronal Differentiation of Stem Cells

In the absence of differentiation cues, pluripotent stem cells can remain in a state of continuous self-renewal in culture. Murine and human ES and iPS cells have the potential to differentiate into any of the three primary germ layers including the ectodermal layer responsible for neural development (Doetschman et al., 1985). Neural progenitors can further differentiate into any of the neural cell types, including glial cells and neurons (Reubinoff et al., 2001). The differentiation outcome greatly depends on the microenvironment in the cell culture (Watt and Hogan, 2000). Specific neuronal subtypes (dopaminergic, GABAergic, etc.) can be cultivated in a controlled microenvironment with specific substrates and media components. There are many different ways to differentiate mouse pluripotent cells into neurons depending on the neuronal subtype of interest (i.e. midbrain dopaminergic (Lee et al., 2000; Maxwell and Li, 2005), serotonergic (Lee et al., 2000; Lu et al., 2016), forebrain (Jing et al., 2011), radial glia (Glaser and Brustle, 2005; Gorris et al., 2015).

Among different protocols for mouse stem cells, differentiation using the vitamin A derivative, retinoic acid (RA), is the most commonly used method (Bain et al., 1995; Fraichard et al., 1995; Francis and Wei, 2010; Guan et al., 2001; Rohwedel et al., 1999) (Fig. 1B). RA plays a role in the developing mammalian embryo and specifies the anterior-posterior body plan (Horschitz et al., 2015; Kessel and Gruss, 1991). Anteriorly, RA induces Hox gene expression (Kessel and Gruss, 1991; Marshall et al., 1992; Simeone et al., 1991) and has specific effects on rhombomere development in the CNS (Marshall et al., 1992). RA interacts with Cellular RA-Binding Proteins (CRABP) which bind to nuclear RA receptors. There are two families of RA receptors (RARs and RXRs) (Rohwedel et al., 1999). RARs include RAR-α, RAR-β and RAR-γ. During neuroectodermal differentiation, RAR-α and RAR-β mRNA are upregulated suggesting that neural differentiation requires these receptor subtypes (Rohwedel et al., 1999). The binding of RA to its receptor activates the transcription of downstream target genes leading to neural lineage selection. In pluripotent cell differentiation, RA induction activates neural-specific transcription factors, signaling molecules, and RA-inducible genes resulting in the production of different neuron sub-types such as GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons (Guan et al., 2001). The RA neural induction method produces both glial cells and neurons. Neurons derived in this method show mature neuronal morphology, express mature neuronal markers such as neuronal nuclei (NeuN) and neurofilament and exhibit neuronal electrophysiology profiles that include mature sodium currents, potassium currents, and action potentials (Bain et al., 1995).

Undifferentiated mouse ES and iPS cells are regularly maintained in a self-renewing, proliferating state in the presence of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) which suppresses differentiation and is required for the maintenance of pluripotency (Vidal et al., 2015; Williams et al., 1988). Neural induction using the “4+/4−” RA protocol takes eight days in vitro. After LIF withdrawal, cells are grown in suspension to form three dimensional spherical aggregates of cells known as embryonic bodies (EB). No RA is included in the medium for the first 4 days of EB culture (termed “4−”), but it is added in the last four days (termed “4+”). This treatment induces EBs to form neurospheres which are then dissociated and plated on an adherent substrate (laminin, Matrigel or fibronectin) to allow terminal neuronal differentiation and neurite extension. These cells will express neuronal markers such as the M subunit of neurofilament and class III β-tubulin protein within a few days. Most of the neurons derived in this fashion will express functional Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels and fire action potentials (Bain et al., 1995).

Neural cells can also be obtained from pluripotent stem cells through lineage selection (Guan et al., 2001). In this method, differentiation into cell types of all three germs layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) occurs in the EBs (Guan et al., 2001). Neuroectodermal cells are selected with serum withdrawal, as well as the inclusion of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) to increase proliferation of neural progenitor cells. Neural differentiation factors and survival-promoting factors (SPF) (interleukin-1β, TGF-β, GDNF and many others) are then added for further differentiation of neural cells into specified neuronal cell types (Guan et al., 2001).

There are also several other protocols for the neuronal differentiation of mouse ES and iPS cells. One particular protocol makes use of mouse stromal supportive cells for neuronal induction (Barberi et al., 2003). Murine bone marrow–derived stromal feeder MS5 cells (Itoh et al., 1989) are mesenchymal stem cells that were originally derived to support the long-term growth and expansion of hematopoietic stem cells, but have also been found to induce a neuro-ectodermal lineage fate in mouse ES cells. In brief, undifferentiated murine ES cells are seeded at a very low density on MS5 cells in serum replacement and cultured for 7 days with bFGF added in the last two days. Co-culture of mouse ES with MS5 cells induces the expression of neural markers (Nestin and Musashi) as early as day 6. Further terminal differentiation can yield different neural subtypes (glial cells, dopaminergic, serotonergic, and GABAergic neurons) depending on the patterning factors used after neural induction. Although RA strongly induces neuronal formation in mouse ES cells, its use in transplantation therapy is unclear. Neuronal induction of the MS5 cell line produces cortical pyramidal neurons that connect with their correct targets in vivo after transplantation (Ideguchi et al., 2010). These graft-to-host axonal connections, however, did not occur when cells were differentiated using RA. The MS5 protocol may thus be more appropriate for use in cell replacement strategies using murine cells.

Human ES and iPS Cell Differentiation

Human ES and iPS cells have the potential to differentiate into all human cell lineages including neurons, making them an attractive cell source for studying disease mechanisms and for drug screening as well as cell transplantation therapy in neurodegenerative diseases such as stroke (Fig. 2). As with mouse pluripotent cells, several approaches have been developed for the neural induction of human pluripotent cells (Suzuki and Vanderhaeghen, 2015). The neuralizing effect of RA, for example, is not the same between human and mouse pluripotent cells. However, like their mouse counterparts, human cells can be differentiated either as EBs in suspension or in adherent culture. We will discuss two differentiation protocols because of their widespread use and proven efficiency.

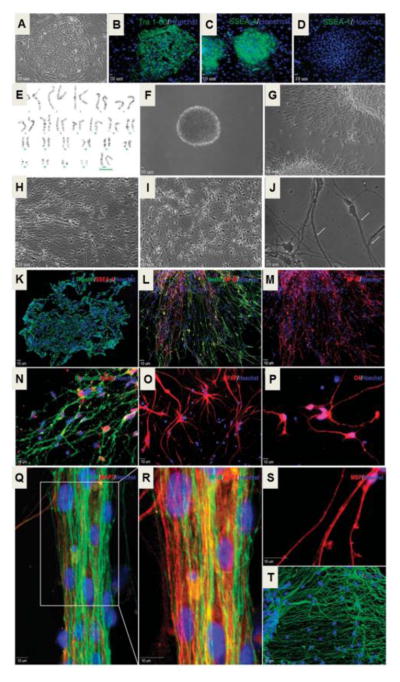

Figure 2. Neural gene expression in differentiating human ES cell-derived neural progenitor cells.

Neural differentiation of UCO6 human ES cells (hESCs). A. Typical colony of hESCs (passage 70). B–D. Colonies express pluripotent markers TRA-1-60 (B) and SSEA4 (C), but are negative for SSEA-1 (D). E. Normal karyotypic analysis of passage 75 UCO6 colonies. F. Twenty-eight day old floating neurospheres (~200 μm in size). G–J. After beginning terminal differentiation, cells exhibit increasingly neuronal morphology after 1 day (G), 7 days (H) and 14 days (I). Cells exhibit significant neurite extensions and many dendritic spines form (white arrows) after 21 days of terminal differentiation (J). K. Cells exhibit high expression of the neural precursor marker Nestin (green) and very low expression of SSEA-4 (red) 1 day after cell adhesion. L and M. Three days into terminal differentiation, Nestin (green) positive, elongated cells begin to express medium chain neurofilament (NF-M; red). N. Seven days after plating, the neuronal markers βIII-tubulin (green) and NeuN (red) were highly expressed. O. Expression of the astrocyte marker GFAP is observed after 7 days. P. Very few O4-positive immunoreactive cells were found in these cells. Q and R. Extensive NF-M (green) and microtubule-associate protein-2 (MAP2; red) immunoreactive projections were present in cells of at 21 days into differentiation. S. Twenty eight days after plating, some projections are positive for myelin-binding protein (MBP), indicating axonal myelination. T. Extensive beds of GFAP-positive astrocytes can also be observed after 28 days into terminal differentiation. All blue staining indicates Hoechst-positive nuclei. Adopted from Figures 1 and 2 in Francis and Wei, 2010 in compliance with the journal’s copyright policy.

After the first isolation of human ES cells in 1998, efforts were focused on their neuronal differentiation based on the knowledge accumulated from the development of the human nervous system. One of the earliest efforts was led by Zhang and Thomson utilizing EB formation (Zhang et al., 2001). In this protocol, human ES cell colonies are dissociated into smaller clusters of cells and grown in human ES cell media without bFGF in low adherence plates. When EBs form, they are grown for four days before being plated on tissue culture plastic in a neural induction media. After neural rosette formation (~8–10 days), rosettes are re-suspended and expanded as neurospheres in medium containing bFGF. Prior to neurosphere formation, cells in the rosette structures express neural markers such as Nestin and Musashi-1. After expansion, these cells are plated on laminin, with mature neuronal markers detectable within 7–10 days. Further differentiation will yield more neurons and, after longer periods in culture, glial cells. This protocol was one of the earliest methods used to generate neural cells from human ES cells and has successfully been applied to human iPS cells (Hu et al., 2010).

Despite its high efficiency, the EB protocol usually involves several weeks of expansion to obtain large numbers of neural precursors before differentiation into neurons and glial cells. In an attempt to overcome this time limitation and avoid the heterogeneous signals encountered by cells in aggregates, Chambers et. al. developed an adherent protocol for the neural differentiation of human ES and iPS cells that produces large numbers of neural precursors in approximately 15 days (Chambers et al., 2009). In brief, human ES or iPS cells are dissociated into single cells and grown on Matrigel in the presence of Rho associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, which reduces apoptosis and increases human pluripotent cell survival after dissociation (Watanabe et al., 2007). When they become confluent, the cells are grown in a knock-out serum replacement media for five days. This medium is supplemented with two inhibitors of the SMAD signaling pathway, Noggin and SB431542. The media is then sequentially changed to neural induction media (increasing amounts of N2 media) for a total of six days. Consequently, neural rosette-like structures are formed and can be further differentiated into neurons of different subtypes. Unlike the EB based protocol, this adherent protocol yields Pax-6 positive neural precursors in more than 80% of the cells, with little need to separate rosettes from cells that have differentiated into other lineages. When used with hiPS cells, the EB protocol had a significantly reduced efficiency and increased variability as compared to hES cells (Hu et al., 2010). On the contrary, the dual inhibition protocol significantly promotes neural differentiation from multiple human ES and iPS cell lines, (Kim et al., 2010) indicating more consistent results with this protocol. In our investigations, we have shown that Noggin can be replaced with the small molecule dorsomorphin in this protocol, greatly reducing the cost for neuronal differentiation of human cells (Drury-Stewart et al., 2012). Dorsomorphin has been used to enhance neural differentiation in suspension cultures (Kim et al., 2010; Morizane et al., 2011) and has been shown to induce efficient neural differentiation alone in adherent culture (Zhou et al., 2010).

Strategies to Enhance Cell Survival after Transplantation: Genetic Modification and Hypoxic Preconditioning

Genetic manipulation of transplanted cells has been tested for enhancing the cell survival after transplantation (Doeppner et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2005). Expression of pro-survival factors shows significant effects on enhancing graft viability after transplantation. For example, we reported in our early research that transplantation of ES cell-derived neural progenitor cells over-expressing the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 survived much better than control cells after ischemic stroke in rats (Wei et al., 2005). Compared to controls, Bcl-2 expressing progenitors also exhibited greater neuronal differentiation and better neurological and behavioral outcomes after stroke (Fig. 3) (Wei et al., 2005). This approach of over-expressing pro-survival genes in transplanted cell has been actively investigated by a number of groups (Chen et al., 2012; Leu et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011). However, this type of genetic engineering requires the alteration of DNA sequences in stem cells, generally by inserting the gene(s) of interest into the genome. While this method can be highly efficient, manipulating the genome of stem cells increases the risk of tumorigenesis in a population of cells with an already established risk of tumor formation.

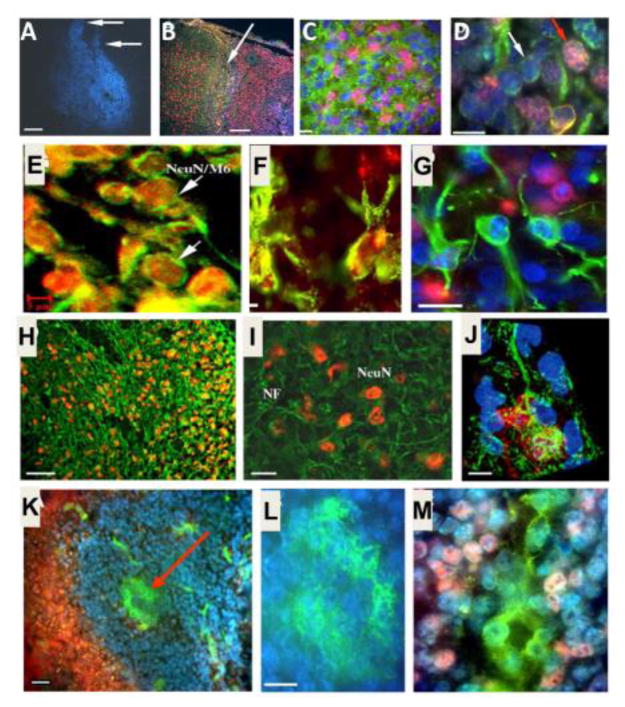

Figure 3. ES cell survival and differentiation after transplantation into the ischemic brain.

Immunohistochemical staining 7 days after intracranial transplantation (14 days post-ischemia). A. Distribution of transplanted ES cells in the post-ischemic basal ganglia revealed by pre-labeled Hoechst (blue) staining. B. Distribution of transplanted ES cells in the post-ischemic cortex. Hoechst-positive ES cells (blue) were present next to undamaged tissue (arrow and the area to the left). NeuN (red) staining shows endogenous neurons in non-ischemic cortical region (left of the arrow) and differentiated neuron-like cells in the ischemic region (right of the arrow). The NeuN staining on the right appears pink in color due to overlap with the blue Hoechst 33342 staining. C. Mouse cell-specific antibodies M2 and M6 (both green) and Hoechst 33342 staining (blue) verified the transplant origin of cells surviving 7 days in the rat host ischemic cortex. NeuN staining (pink) identified differentiated neuronal cells. D. Higher magnification of a confocal image shows the double labeling of Hoechst (blue) and mouse antibody M2/M6 (green) that confirms murine origin of these cells (white arrow). The triple-labeled cells with the additional staining of NeuN (pink) identify ES cell-derived neurons (red arrow). E. Confocal images of NeuN staining (red), mouse antibody M6 staining (green), and overlapped double staining (yellow) show neuronal cells originated from transplanted ES cells in a transplantation area. Scale bar equals 800, 200, 20, 10 and 5 μm, in A, B, C, D and E, respectively. F. and G. Differentiations of transplanted ES cells in the host ischemic cortex and striatum. ES cells were labeled with BrdU or Hoechst 33342 prior to transplantation. The double labeling of BrdU (red) and GFAP (green) identified differentiated astrocytes of ES cell origin (F). An image taken from (G) an 8-μm section shows Hoechst-prelabeled ES cells double stained either with NeuN (red) or GFAP (green), consistent with ES cell differentiation into neurons and astrocytes. Scale bar = 20 μm. H–J. Dendrite growth after ES cell transplantation in the ischemic cortex. NeuN-positive cells and apical dendrite distribution in the ipsilateral cortex. Seven weeks after ES cell transplantation, NeuN and NF double immunostaining in the ischemic core region of the ipsilateral cortex under an inverted fluorescence microscope. Many NeuN-positive cells (yellow or orange) were surrounded by NF labeled processes (green). A confocal image of NeuN/NF-positive ES cell in the 8-Am-thick slice of ischemic cortex. The cell body was positive to NeuN staining (red), cell processes were positive to NF staining (green). The Hoechst labeling (blue) showed several transplanted ES cells. Scale bar = 60 μm in H, 20 μm in I, 10 μm in J. K–M. ES cell-derived Glut-1-positive cells in the ischemic region. Seven days after transplantation, the ischemic core was filled with ES cells (Hoechst-positive, blue) and contained Glut-1-positive vascular-like structures of endothelial cells (green; arrow). Scale bar = 50 μm. Enlarged view of a vascular structure in K (L), positively stained with Glut-1 (green). Scale bar = 10 Am. Glut-1-positive endothelial cells (green) were also co-labeled with Hoechst (blue), verifying their origination from transplanted ES cells (M). The pink color is from neighboring NeuN-positive cells. Images were taken using an inverted fluorescence microscope. Adopted from Figures in Wei et al., 2005 in compliance with the journal’s copyright policy.

Other techniques have been developed to increase survival of stem cell grafts after transplantation. Instead of over-expressing exogenous genes in transplanted cells, we developed an alternative strategy stimulating endogenous mechanisms to promote the survival and regenerative properties of transplanted cells (Pignataro et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2005b). In cardiomyocyte ischemia, an early exposure of the heart to brief episodes of ischemia protected the myocardium against a later prolonged ischemic insult (Murry et al., 1986). We showed that pretreatment of ES or iPS cell-derived neural progenitor cells in low oxygen condition (0.1–1% O2) for 8–12 hrs markedly enhanced their tolerance to OGD insult in vitro and after transplantation into the ischemic brain (Fig. 4). The pro-survival and an enhanced homing to the ischemic brain were later demonstrated using BMSCs (Theus et al., 2008b; Wei et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2013).

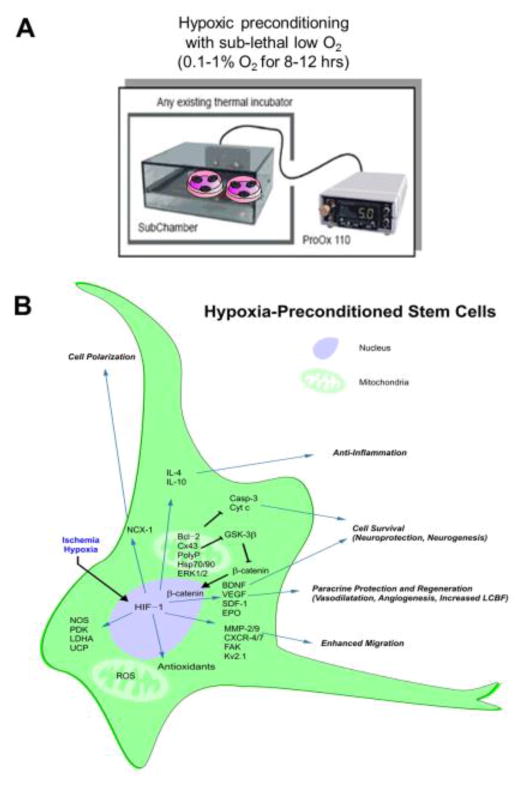

Figure 4. Hypoxic preconditioning of stem cells or neural progeinitor cells and the mechanis of action.

A. Neuronally-differentiated cells or BMSCs were subjected to hypoxic preconditioning priming treatment before to be used for cell therapy. Cells were placed in a hypoxic chamber (0.1–1% O2) for 8–12 hrs before transplantation. B. Potential mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of hypoxic preconditioning. The hypoxic preconditioning strategy was designed to mimic and utilize endogenous protective mechanisms to promote neuroprotection, tissue regeneration and brain function recovery. Hypoxic preconditioning directly induces HIF-1α/β upregulation that increases BDNF, SDF-1, VEGF, EPO and many other genes which can stimulate neurogenesis, angiogenesis, vasodilatation and increase cell survival. HIF-1 expression regulates antioxidants, survival signals and other genes related to cell adhesion, polarization, migration, and anti-inflammatory responses. Abbreviation in the figure: BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; Casp, caspase; Cx43, connexin-43; CXCR, CXC chemokine receptor; Cyt c, cytochrome c; EPO, erythropoietin; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; HIF-1, hypoxia-inducible factor-1; Hsp, heat shock protein; IL-4, interleukin-4; IL-10, interleukin-10; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NCX-1, sodium-calcium exchanger-1; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; PDK, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; polyP, polyphosphate; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SDF-1, stromal-derived factor-1; UCP, uncoupling protein; VEGF, vascular endothelial

Numerous investigations have demonstrated the effectiveness of hypoxic/ischemic preconditioning in virtually all types of cells, organs, and in animals (Gross and Auchampach, 1992; Yu et al., 2006). Preconditioning has been successfully applied in cell therapy to protect the transplanted cells from apoptosis and increase their survival after transplantation in vivo. Hypoxic preconditioning (HP) was performed by exposing cells to non-lethal hypoxia (0.1–1%) for certain hours before transplantation, which is very effective in increasing transplanted cell survival and improving overall functional recovery after stroke or myocardial infarction (MI) (Hu et al., 2011b; Hu et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2015; Theus et al., 2008a; Wei et al., 2012). HP has also shown enhancement of cell differentiation in culture and after transplantation (Sart et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2015). Non-lethal exposure to hypoxic conditions is believed to activate the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) pathway, increasing expression of HIF-1α-dependent genes. Expression of a number of trophic factors is increased, including brain-derived and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF and GDNF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor FIK-1, erythropoietin (EPO) and its receptor EPOR, and stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1) and CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) (Wei et al., 2012) (Fig. 4). With a greater translational significance, these beneficial effects of HP have been demonstrated in iPS cell-derived neural progenitor cells (Fig. 5A and 5B).

Figure 5. Neuronal differentiation of iPS cells with hypoxic preconditioning and transplantation into the ischemic brain.

A. Somatic cells such as fibroblasts can be reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells with specific transcription genes. These cells can be differentiated into mature and fucntional neurons, firing repetitive actiona potentials and can be manipulated with gene modification. B. At the later stage of neural induction, cells are subjected to non-lethal hypoxic preconditioning treatment and then ready for translantation into the ischemic brain. C. Demonstration of implanted cells in the ischemic core and peri-infect region. Immunohistochemial staining show remaining and/or regenerated vasculartures (GLUT1 (blue) and Collagen IV (green) staining) and the formation of a glia score (GAFP, red) surrounding the ischemic core 14 days after sensorimotor cortex stroke. Green flourescence GFP labeled iPS-derived neural progenitor cells were implanted into the ischemic core and peri-infarct regions;. these hypoxic preconditioned cells survived well several weeks after transplantation.

Pharmacological preconditioning is an alternative way by exposing stem cells of pharmacological agents or trophic/growth factors to increase their in vivo survival. Diazoxide (Afzal et al., 2010), minocycline (Sakata et al., 2012), and SDF-1 (Pasha et al., 2008) can all enhance stem cell survival after transplantation in stroke or MI animal models.

In Vitro and Animal Models for the Study of Ischemic Stroke

There are many in vivo and in vitro models used to study stroke and stem cell therapy. While successes in treating stroke in animal models have been unreliable when translated to human clinical trials, ischemic stroke models are necessary to understand the pathophysiology of stroke progression and provide initial information for the development of appropriate therapeutics. In vitro model of oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD) mimics the hypoxic and energy crisis that occur during acute ischemic injury. Hence, this model is widely accepted and tested for studies of cell death, mitochondrial dynamics, and reperfusion/reoxygenation injuries.

In vitro investigations using cell culture models allow the understanding of the basic cellular, molecular and biochemical mechanisms without the systemic influences of an in vivo model. The OGD technique, applied to cultures of pure primary neurons or mixed cultures of glia and neurons, is the most commonly used in vitro model of stroke (Tornabene and Brodin, 2016). Depriving cultured neurons of oxygen and glucose supplies simulates, to a certain extent, in vivo ischemic conditions. Briefly, growth medium is replaced with a physiological solution like Ringer’s solution and cultures are placed in an airtight chamber with low oxygen (0.1 – 1.0%). After certain duration of times (usually one to several hours depending on the degree of hypoxia and cell types), cells are then returned to their normal culture conditions. Cell death and survival are assessed after an appropriate “reperfusion” period, usually in 24 hours. Sometimes, cell death is measured after a prolonged time of OGD without “reperfusion”. Cell death induced by different OGD episodes may be mediated or dominated by distinctive mechanisms, e.g. necrotic and apoptotic pathways (Jones et al., 2004)(Agudo-López et al., 2010). OGD can be used with different cell types, including ES cell-derived neural precursors and glial cells, to study their mechanisms of survival and differentiation under an ischemia-like condition. For example, researchers used OGD to study a nuclear translocator (ARNT) in ES cells in response to hypoxia (Maltepe et al., 1997). In vivo models allow us to study stroke within the scope of a comprehensive biological system. Here, we will discuss some major in vitro and in vivo stroke models used in preclinical research.

Inducing stroke in animals allows researchers to reproduce stroke conditions in vivo together with the related systemic influences. This allows for the study of stroke pathology and pathophysiology and the exploration for optimal conditions (survival, timing, and location) for experimental cell transplantation therapies. Animal models for the study of ischemic stroke primarily vary by their methods of induction, location, duration, and, correspondingly, the severity of ischemic injury and functional deficits (Ingberg et al., 2016; Molinari, 1988). Ischemic stroke models can be divided into two broad categories: focal and global ischemia. Focal ischemia is more commonly seen in clinical cases and widely tested in basic research. It is induced by an acute occlusion of specific vessels to cause damage in affected brain regions. Focal ischemia can be modeled with transient or permanent occlusions and the extent of damage can be small or large depending on the occlusion of the artery and the anatomy of cerebral vassal networks. The word “global ischemia” is used when all cerebral blood flow including that of the vertebral arteries cease. Clinically, global ischemia occurs during suffocation, cardiac arrest or after bilateral common carotid artery (CCA) occlusions. The middle cerebral artery (MCA) is the most commonly affected vessel in stroke patients. Accordingly, the most common models of ischemic stroke in rodents involve the occlusion of MCA. Here, we will discuss several models of ischemic stroke.

Focal Ischemic Stroke Models

Middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) of rodents

The MCAO model is widely used and accepted because it most closely resembles human stroke conditions. The original method for inducing this stroke was the Tamura method for occluding the proximal MCA in the rat, causing ischemic damage in the cortex and basal ganglia (Tamura et al., 1981a, b). This procedure requires an invasive subtemporal craniotomy. The intraluminal method, on the other hand, requires no craniotomy and is thus less invasive (Longa et al., 1989). A neck incision is made and a nylon intraluminal suture is introduced through the external carotid artery to occlude the MCA. This procedure is reversible and can be varied with a thicker (2–0) or thinner (4–0) suture thread (Longa et al., 1989; O’Brien and Waltz, 1973). Both models induce relatively large brain injuries involving cortex and/or subcortical regions or even an entire half hemisphere.

Using MCAO models, stem cell transplantation studies have been extensively performed during the past 20 years. Neuroprotective effects of therapeutic benefits in reducing infarct volume, and improving functional outcomes during acute and chronic phases can be examined. It is difficult, however, to evaluate neurovascular damage and neuronal circuit reestablishment at structural and network levels in severe stroke models. To this end, small stroke modes are more suitable for morphological examinations of neural network structural repair.

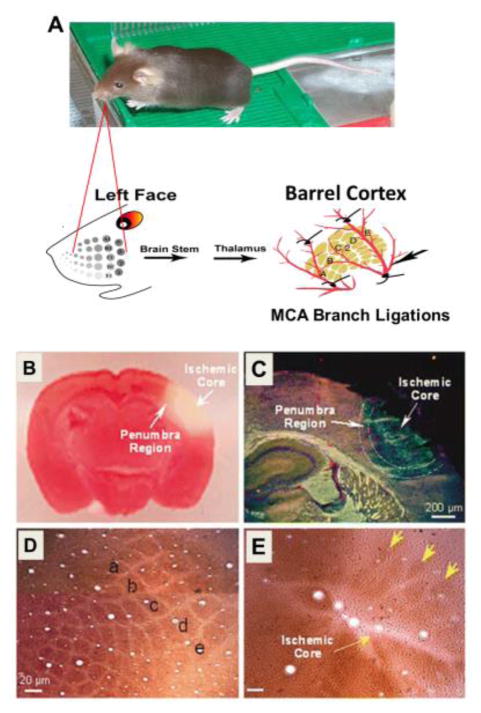

Barrel cortex stroke and small stroke models

Barrel cortex stroke is a small focal stroke model, involving occlusions of distal branches of the MCA. According to American Heart Association, small strokes are common in clinical cases (~40% of total cases)(Lloyd-Jones et al., 2010). In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to develop and study small stroke models (Liu et al., 2012; Llovera et al., 2014; Pevsner et al., 2001). This shift appears not only due to clinical relevance, but also for the advantage of the feasibility of examining structural and neural network repair after a well controlled focal cerebral ischemia. Small ischemic strokes can be induced by ligations of the distal branches of MCA. A typical small stroke model in rats was initially reported by Ling Wei in 1995 (Liu et al., 2012) (Fig. 6). In this model, the barrel cortex and its vasculature are visualized using intrinsic optical signal imaging based on the mechanism that stimulation of the contralateral whiskers increases the local cerebral blood flow (LCBF) in the barrel cortex. The distal branches of the MCA around the barrel cortex are identified and then ligated with 10-0 sutures. In recent years, variations of the small barrel stroke models have been reported. In the mouse, the main branch of the MCA is permanently occluded combined with transient bilateral occlusions of the CCA. This simplified surgery procedure is sufficient to reduce the local blood flow and cause infarct formation in the affected sensorimotor cortex. The infarct volume induced by this procedure is relatively larger than the original barrel cortex stroke; it retains all the advantages of a small stroke model but also allows for functional and behavioral tests of the sensorimotor cortex in rodents.

Figure 6. Small stroke model of barrel cortex ischemia in rodents.

A. Focal ischemic insult to the barrel cortex is induced by permanent occlusion of the distal branches of the right or left middle cerebral artery combined with transient ligations of bilateral common carotid arteries. The barrel cortex is identified by the optical imaging in responding to whisker stimulation. B. Ischemia-induced barrel cortex infarct formation and cell death. Middle cerebral artery branch ligations induced a focal ischemic infarct and cell death in the barrel cortex. Selective damage occurred to the right barrel cortex region shown as a negative (white) area in triphenyl tetrazolium staining (red) 24 hrs after ischemia. The pink area between the normal cortex and ischemic core represents the bordering penumbra area. C. In the immunohistochemical image, Glut-1 staining (red) shows vascular endothelial cells in the penumbra and normal brain tissues. NeuN (blue) indicates neurons. Ischemic core shows the autofluorescence associated with damaged tissue. D and E. Cytochrome oxidase staining revealed the barrel column structures in the context of a normal cortex (D) and undergone ischemic damage (E). The lowercase letters “a”–”e” in image D illustrate the characteristic pattern of barrel distribution in the cortex. Fourteen days after ischemia, most of the barrel column structures disappear except a few barrel-like clumps (arrowhead) preserved in the peripheral region of the barrel cortex (E).

Since the whisker-thalamus-barrel cortex neuronal pathway and the relationship between the barrel cortex and whisker activity had been well defined (Woolsey et al., 1996), the barrel cortex and the sensorimotor cortex stroke models are ideal for examining the intracortical and thalamo-cortical neuronal morphological connections and functional recovery. For example, the corner test can be used to test the functional deficit of affected whiskers after stroke (Langhauser et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2002). In this test, when facing toward a 30° corner wall, normal control animals turn equally to the right or left whereas stroke animals turn more frequently toward the non-impaired side (ipsilateral to infarcted brain)(Zhang et al., 2002). Moreover, our group has used whisker stimulation as a physical rehabilitation treatment during chronic phase of stroke. It was shown that the target-specific peripheral activity reduced cell death and increased trophic/growth factors in the peri-infarct region of the cortex. Consequently, the physical therapy enhanced neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and functional recovery after ischemic stroke (Li et al., 2011; Li et al., 2008a; Whitaker et al., 2007).

Other focal ischemic stroke models in rodents

There are several other ways to induce focal ischemia including the photothrombotic (Schmidt et al., 2015), autologous clot (Jin et al., 2014; Taupin and Gage, 2002), and endothelin-1 (Roome et al., 2014) methods (Table 1). The photothrombotic method is a non-invasive method in which a photosensitive dye is intravenously injected into the animal (Chen et al., 2004; De Ryck et al., 1996; Eichenbaum et al., 2002). To induce thrombotic occlusion, the distal MCA is irradiated by a laser to activate microthromboses. A significant strength of this model is that it allows MCA occlusion in awake animals. In the thromboembolic stroke model, the embolus is created by removing the arterial blood from a donor into tubing of predetermined size. The clots are formed by alternating the blood through different syringes with saline. In the technique described by Zhang and colleagues, the clot was introduced into the external carotid artery (ECA) to be lodged into the origin of the MCA (Zhang et al., 1997). A drawback of thromboembolic models is the difficulty for precise control of reperfusion and larger variations in infarct formation (Wang et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 1997). In the Endothelin-1 model, the vasoconstrictor peptide Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is injected into the brain. This peptide reduces blood flow and induces ischemic injury (Windle et al., 2006). This model can induce transient to semi-permanent focal ischemia, but reperfusion in this model still requires characterization (Biernaskie et al., 2001). It was reported that systemic inflammation continues to impair reperfusion via endothelin dependent mechanisms (Murray et al., 2014). ET-1 can be injected intracerebrally or topically applied onto the brain into an area of interest like the motor cortex (Windle et al., 2006). It can also be injected next to the MCA to induce larger ischemic injury (Biernaskie et al., 2001).

Table 1.

Focal ischemic stroke models.

| Model | Surgical procedures | Species/Ages | Major pathological change | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photothrombosis | intravascular photocoagulation and inducing occlusion of the irradiated vessels with secondary tissue ischemia | Rat/Adult | Localized focal injury that may depend on injection site. Massive T cell and macrophage infiltration, controlled lesion in cortical areas, fast blood-brain barrier disruption and vasogenic edema | (Rosenblum and El-Sabban, 1977); (Watson et al., 1985) |

| MCA Occlusion | thrombembolic MCAO: injecting clots that were formed in vitro or by endovascular instillation of thrombin for in situ clotting | Rat/Adult/Neonate Mouse/Adult Dogs/Adult Sheep/Adult Monkey/Adult | Severe stroke model can cause half hemisphere damage in suture MCAO; Vascular endothelial damage, platelet activation and subsequent thrombotic vessel occlusion | (Tamura et al., 1981a); (Nagasawa and Kogure, 1989); (Chen et al., 1986); (Boltze et al., 2008); (Fan et al., 2012) |

| Endothelin Stroke | cortical application of ET-1 | Rat/Adult | Necrotic, apoptotic and hypertrophic neurons and neurons with pyknosis in surrounding penumbra | (Robinson et al., 1990); Masaki et al (1992); Macrae et al. (1993); (Sharkey et al., 1993); Fuxe et al. (1997) |

| Barrel Cortex Stroke | permanently ligating 3 to 6 branches of MCA, temporarily occluding CCA | Mouse/6–8 wk; Rat/Adult/Neonate | First ischemic model specifically targeting the barrel cortex and suitable for whisker functional studies; Infarct formation in rodent somatosensory barrel cortex, vascular endothelial damage, and platelet activation | (Wei et al., 1995); (Luo et al., 2008); (Jiang et al., 2016) |

Abbreviation in the Table: BBB, blood-brain barrier; BMSC, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell; CCA, common carotid artery; ES, embryonic stem cells; ET-1, endothelin-1; iPS, induced pluripotent stem cells; LCBF, local cerebral blood flow; MCA, middle cerebral artery; NSC, neural stem cells; PN, postnatal.

Global Ischemia Models

Two-vessel occlusion model

In this model, histopathological ischemic damage to the forebrain is induced by bilateral occlusion of the CCA in conjunction with systemic hypotension (down to 50 mm Hg) to attenuate forebrain blood flow in the animal (Pulsinelli and Brierley, 1979). Hypotension is induced by arterial or central venous exsanguinations along with CCA clamping. The occluding clamps are removed and the shed blood is then used to reperfuse the brain (Smith et al., 1984). Injury to specific brain areas depends on the duration of exposure to the ischemic conditions. The hippocampus, caudate-putamen, and cerebral cortex can all be affected, depending on the duration of the ischemia (Smith et al., 1984). This occlusion technique can produce a reversible and reliable forebrain ischemia.

Four-vessel occlusion model

This model is carried out in two stages. First, reversible clamps are loosely placed around the CCA and the vertebral arteries are electro-cauterized (Pulsinelli and Brierley, 1979). After 24 hours, the CCA clamps are tightened (Pulsinelli and Brierley, 1979). This results in loss of body responsiveness, with approximately 75% of animals losing their righting reflex. Within minutes after CCA clamping, isoelectric activity appears on electroencephalography (EEG). Reperfusion is allowed when the clamps on the CCA are removed, at which point animal activity is restored. Histopathology reveals that neuronal damage occurs within 20 to 30 minutes of ischemia. Damage usually appears in the hippocampus, striatum, and posterior neocortex (Pulsinelli and Brierley, 1979). Unlike the two-vessel method, this method is only partly reversible because the vertebral arteries are cauterized. Another drawback to this model is that it has a higher risk of inducing seizures, which voids data if seizure is not the research target of the study.

Stem Cell/Neural Progenitor Transplantation in Animal Models

An appropriate selection of the animal model is important for reaching the goal of an investigation. For example, different stroke models may be suitable for investigations on neuroprotection or regeneration or neurovascular/neural network repair. An ischemic insult that damaged sub-cortical regions including the hippocampus and dentate gyrus may not be feasible for a study relying on the neurogenesis in the subgranular zone (SGZ). In addition to test the efficacy of cell therapies, one of the goals of preclinical cell transplantation studies is to optimize transplantation parameters so that the transplanted cells survive, migrate, differentiate and integrate with host cells appropriately in vivo. Two important parameters to be considered for transplanting any cell type are the administration route and the timing of delivery. These parameters may vary by cell type and the model of ischemic stroke. Before translating cell therapy into human patients, transplantation parameters need to be verified in different animal models. The STEPS committees have set out guidelines for preclinical studies pointing out the need for a well-characterized cell population, dose-response studies, and tests in different models of at least two species (de Mello et al., 2015).

Intracerebral/Intracranial transplantation

Identifying a favorable microenvironment for stem cell transplantation allows for increased survival of the graft. Some have suggested that transplanting cells into the penumbra is a more successful approach because the penumbra provides a more favorable microenvironment for the graft (Johnston et al., 2001; Theus et al., 2008a; Wei et al., 2005). An alternative for avoiding stem cell transplantation into the cytotoxic stroke core is to transplant cells into the hemisphere contralateral to the infarct (Modo et al., 2002b). It was shown in rats that a greater percentage of cells survived in the contralateral somatosensory cortex and striatum compared to those from ipsilateral or intraventricular injections (Modo et al., 2002b). This strategy may be useful based on the observation that endogenous neural stem cells and exogenous transplanted cells have the ability to migrate to the ischemic infarct region (Arvidsson et al., 2002; Li et al., 2008a; Modo et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2009b).

Our recent investigation on the cell fate after stroke, however, provided a different rationale for selecting the transplantation site. We showed in the sensorimotor cortex stroke and several other stroke models that inside the ischemic core, normal or even higher levels of BDNF and VEGF remained for many days after stroke. Some NeuN-positive cells with intact ultrastructural features of synapses and axons resided in the core 7–14 days post stroke. BrdU-positive but TUNEL-negative neuronal and endothelial cells were detected in the core where extensive extracellular matrix infrastructure developed. Active regenerative niche was identified inside the core many days after stroke. These data suggest that the ischemic core is an actively regulated brain region with residual and newly formed viable neuronal and vascular cells acutely and chronically after at least some types of ischemic strokes (Jiang et al., 2016). The microenvironment of ischemic core several days and weeks after stroke provides certain cellular support, blood flow supply and strong trophic factor endorsements for cells to survive while the remaining and regenerating neurovascular infrastructure may be utilized as therapeutic targets for repairing damaged neurovascular unit and neuronal networks. With recent progress in priming transplanted cells using the preconditioning strategy, preconditioned cells are more tolerant and survive better even after transplantation into the ischemic core (Theus et al., 2008a; Wei et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2015). It appears that for the purpose of tissue repair, the development of transplanted cells with greater survival and regenerative properties will have the advantage of implanting cells into the brain area(s) where they are needed (Fig. 5C).

Intravascular administration

Stem cells may also be administered systemically through the vasculature. While this strategy is less invasive and does not necessitate craniotomy, vascular administration adds the requirement that cells must cross the blood brain barrier and home to the brain injury site. Vascular delivery of cells can be either intravenous or intra-arterial. There are advantages and disadvantages to both methods. While less invasive than intra-arterial delivery, the intravenous route delivers the cells through the systemic and pulmonary circulations where cells are more likely to be entrapped in other organs (spleen, liver, and lungs). Intra-arterial delivery, on the other hand, circumvents the systemic circulation. Li and colleagues reported that 21% of cells entered the brain with intra-arterial administration compared to only 4% of cells with intravenous administration (Biernaskie et al., 2001). Similarly, Guzman and colleagues reported that 1300 cells/mm2 populate the infarct area after intra-arterial administration compared to only 74 cells/mm2 after intravenous delivery (Guzman et al., 2008). Bone marrow mesenchymal cells systemically infused into ischemic rats have been reported to migrate to the site of injury (Eglitis et al., 1999; Samper et al., 2013). Some reports also showed potential neuronal differentiation of the transplanted cells after intravascular administration (Chen et al., 2001a). The homing of BMSCs to the brain lesion site, however, is generally very low (~1%) (Arbab et al., 2012) and neuronal differentiation is uncertain or difficult for these multipotent cells although some recent work reported improved differentiation from these cells (Kitada, 2012). Intravenous injection of human neural stem cells into an ischemic rat led to incorporation of some cells into the ischemic infarct. However, transplanted stem cells were also trapped in other organs such as the kidney, lung, and spleen. Within the brain, transplanted neural stem/progenitor cells were also found in the cortex, along the corpus callosum, and in the hippocampus (Chu et al., 2003).

Trophic factors may improve the homing of transplanted cells to the brain region. For example, it was demonstrated that the intravascular injection of bone marrow stem cells coupled with subsequent injections of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and stem cell factor (SCF) increased cell homing to the brain and neuronal differentiation (Corti et al., 2002; Piao et al., 2009). With G-CSF and SCF, more transplanted bone marrow cells could arrive at the ischemic brain, suggesting that bone marrow-derived stem cell therapy supplemented with other neurotrophic factors is a potential strategy in the stroke treatment.

This is also supported by our observation that a parathyroid hormone (PTH) can mobilize stem cells from the bone marrow and promote the homing of these cells to the brain. We showed that after 6 days of PTH treatment, there was a significant increase in bone marrow derived CD-34/Fetal liver kinase-1 (Flk-1) positive endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) in the peripheral blood. PTH treatment significantly increased the expression of trophic/regenerative factors including VEGF, SDF-1, BDNF and Tie-1 in the brain peri-infarct region. Angiogenesis, assessed by co-labeled Glut-1 and BrdU vessels, was significantly increased in PTH-treated ischemic brain compared to vehicle controls. PTH treatment also promoted neuroblast migration from the subventricular zone (SVZ) and increased the number of newly formed neurons in the peri-infarct cortex (Wang et al., 2014).

In any event, the route of intravenous administration has been effective in preclinical and clinical trials. In one study, IV administration of cord blood stem cells in rat stroke animals resulted in improvement in motor functional recovery as assessed by the Rota-rod test (Chen et al., 2001b). Similarly, intra-arterial administration of mesenchymal stem cells improved the NSS score and performance in the adhesive-removal test of stroke rats (Biernaskie et al., 2001). IV administration of autologous MSCs has already been shown to be safe and appears to be effective in small clinical trials in human stroke patients (Suarez-Monteagudo et al., 2009; Wise et al., 2014). The PTH-treated mice mentioned above showed significantly better sensorimotor functional recovery compared to stroke controls. It is possible that mobilizing endogenous bone marrow-derived stem cells/progenitor cells is an alternative regenerative treatment after ischemic stroke (Wang et al., 2014).

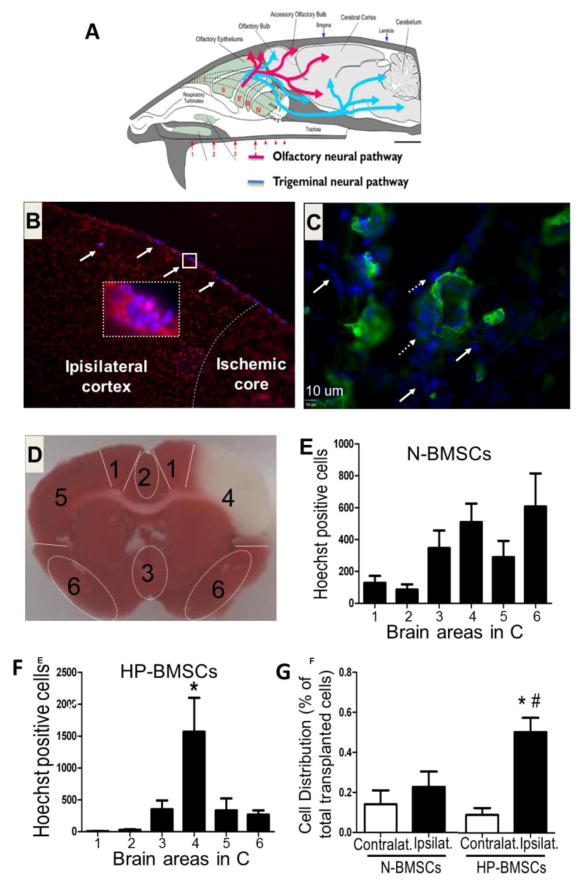

Intranasal administration

The intranasal delivery route is a non-invasive method for bypassing the blood-brain barrier (BBB). It has been used clinically and in pre-clinical research to administer drugs, peptides/proteins, and a variety of factors (Fig. 7A). In cell transplantation therapy, intranasal delivery of stem cells is a new avenue of investigation. Intranasal delivery offers two major advantages that show great clinical potential for the treatment of stroke. Transplanted cells essentially move from the nasal mucosa into the CNS through the cribriform plate and migrate into the brain parenchyma along the olfactory neural pathways and blood vessels (Fig. 7A). In this procedure, the membrane permeation enhancers (like hyaluronidase) are often needed (Lochhead and Thorne, 2011). It was shown that rat MSCs reached the brain only one hour after intranasal delivery through either the rostral migratory stream (RMS) or the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Danielyan et al., 2009). Complete reproducibility of cell distribution, however, still need verification and improvement for different cells.

Figure 7. Distribution of BMSCs after intranasal delivery into the ischemic brain and the effect of hypoxic preconditioning.

The intranasal administration is an established method for drug delivery. A. The drawing illustrates how therapeutics may bypass the BBB via from the intranasal space and distribute in brain regions. B. Immunohistochemical staining reveals the distribution of transplanted cells after intranasal delivery of BMSCs in a stroke mouse brain. BMSCs (blue color from pre-labeled Hoechst 33342) were seen in the cortex near the ischemic core. The morphology of pre-labeled cells can be better seen under higher magnification (400 X, magenta cells, inserts images). C. collagen IV (green) was used to show brain blood vessels. Transplanted cells (blue) were found inside vessels, lining vessels (dashed arrows), or deposited outside the vessels (arrows). D. Distribution of BMSCs in different brain regions was measured and quantified by counting Hoechst 33342 dye positive cells in different brain regions. The assigned number for each brain area is shown in the brain section stained with TTC. Area 4 is the ischemic core region. E and F. N-BMSCs or HP-BMSCs (1 X 106) were delivered via intranasal administration 24 hrs after stroke. One and half hrs later, host brain cells (propidium iodide, PI, red, see B) and transplanted BMSCs (Hoechst 33342, blue) were counted. N-BMSCs showed a random distribution pattern (E) while HP-BMSCs (F) selectively home to the ischemic cortex (area 4 in D). G. The bar graphs summarize the percentage of cells that reached the ischemic brain region 1.5 hrs after intranasal delivery compared to all the cells found in the other brain region. Significantly higher percentage of HP-BMSCs was seen in the ispilateral side of the brain. N=6, *. p<0.05 vs. HP-BMSC in contralateral brain, #. p<0.05 vs. N-BMSC in the ispilateral brain (I think * and # need to be clarified). Revised from Figures in Wei et al., 2013 in compliance with the journal’s copyright policy.

We demonstrated for the first time that hypoxic preconditioning is a promising or even essential strategy for intranasal delivery of stem cells and neural progenitor cells (Hu et al., 2011b) (Fig. 7B–7G). In focal ischemic stroke mice, intranasally delivered hypoxia preconditioned (HP) BMSCs arrived at the ischemic cortex and deposited outside of vasculatures only 1.5 hrs after administration. In comparison to non-HP BMSCs prepared under normoxic condition (N-BMSCS), HP-treated BMSCs (HP-BMSCs) expressed high levels of genes associated with migratory activities, including the CXC chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2), and MMP-9. HP-BMSCs showed enhanced migratory activities in vitro and increased homing to the infarct cortex when compared with N-BMSCs. Three days after transplantation (four days after stroke), BMSC transplantation decreased cell death in the peri-infarct cortex. Mice receiving HP-BMSCs showed significantly reduced infarct volumes compared to stroke mice receiving N-BMSCs. HP-BMSC-treated mice performed much better than N-BMSC- and vehicle-treated animals (Wei et al., 2013). Furthermore, we demonstrated in a neonatal stroke model of rats that intranasally delivered BMSCs showed beneficial effects on brain development after stroke and that rat pups receiving HP-BMSCs developed better sensorimotor activity, olfactory functional recovery, and performed better in social behavioral tests (Wei et al., 2015). Recently, we showed that intranasal delivery of HP-BMSCs enhanced neurogenesis and angiogenesis after intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke in mice (Sun et al., 2015).

Timing of Stem Cell Transplantation

The environment of the brain after stroke is constantly changing. Timing of stem cell delivery is an essential parameter to be considered before transplantation. Unfortunately, the optimal time for transplantation in animal models and consequently in patients is poorly defined. Stem cell transplantation has been performed in the order of hours to weeks after stroke induction depending mainly on the investigator. Early time transplantation (e.g. <24 hours) after stroke has been tested and some reported neuroprotective effects (Chu et al., 2005a; Vendrame et al., 2004). In an investigation on intrastriatal transplantation of human NSCs, it was shown that cells transplanted at 2 days after stroke survived better than those transplanted 6 weeks after stroke (Darsalia et al., 2011). Transplanting greater numbers of grafted NSCs did not result in a greater number of surviving cells or increased neuronal differentiation. It is now widely believed that several days after the onset of stroke is an appropriate time window for cell transplantation therapy. Based on the understanding of the time course of excitotoxicity, brain edema, inflammatory reaction, and trophic factor expressions, we and many others have typically transplanted cells at 7 days after stroke, at which point the extracellular glutamate has returned to lower levels, brain edema subsided, and the microenvironment in the post-stroke brain has entered into a pro-regeneration stage (Schmidt and Minnerup, 2016). Coincidentally, reported clinical trials with autologous MSCs have been limited by the time needed to expand cells to the point that an appropriate cell numbers are available, which normally takes several days or longer (Honmou et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2010). Very delayed time points of cell transplantation (several months after stroke) are also clinically relevant, but few pre-clinical investigations have focused on the chronic phases. More research remains to be carried out to delineate the optimal strategies for cell transplantation for chronic stroke patients.

Mechanisms Underlying Stem Cell Therapy

Neuroprotective effect and reduction of infarct volume

Investigations on transplantation of neural stem/progenitor cells at early and sub-acute phases after stroke report neuroprotective effects of reducing infarct volume (Takahashi et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2015). The infarct reducing effect can be observed in the acute phase after stroke. Using intracerebral injection and i.v. infusion, we and others have shown that BMSCs have the potential of reducing brain infarction and neuronal cell death and improving functional recovery after ischemic stroke. Since the homing of BMSCs to the brain tissues is very low after i.v. infusion, the mechanism of action of this treatment is likely due to increased diffusible trophic and growth factors such as BDNF, NGF and VEGF (Chau et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2015).

Endogenous repair mechanisms

Stem cell transplantation provides a supplement to the endogenous repair that may occur after ischemia. It is now generally recognized that the adult brain has the ability to regenerate neurons. As early as 1961, Smart first demonstrated that the adult mammalian brain showed neurogenic activity (Smart, 1961). It is apparent now that the adult brain has several niches for neurogenesis, particularly the subventricular zone (SVZ) lining the lateral ventricles and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus (Altman, 1962, 1969; Kaplan and Hinds, 1977; Kempermann et al., 2004; Taupin and Gage, 2002). Under normal physiological conditions, neural progenitors from the SVZ migrate to the olfactory bulb (Kornack and Rakic, 2001) comprising the rostral migratory stream (RMS). These neural progenitors migrate in chains and differentiate into interneurons in the olfactory bulb where they functionally integrate themselves into the existing neural circuitry (Altman, 1969).

Several types of brain injuries including seizure, stroke, and traumatic brain injury can up-regulate progenitor proliferation (Ernst and Christie, 2006; Parent et al., 1997; Rola et al., 2006). Under ischemic conditions, proliferation of neural progenitors increases in the SGZ and the SVZ (Kuge et al., 2009; Li et al., 2008b; Li et al., 2010). Neural progenitors from the SGZ do not seem to migrate to areas of injury after stroke, but those from the SVZ are diverted laterally from the RMS to the site of the injury. Neurogenesis peaks at 3 and 4 weeks after ischemic insult in the SVZ and the SGZ, respectively. Migration of progenitors from the SVZ to the site of injury peaks at around 4 weeks (Kuge et al., 2009).

The adult brain’s endogenous neurogenic machinery requires a coordinated effort between the SVZ, chemotactic factors, and the vasculature to replace dead or dying cells. The process of neuroblast migration relies greatly on the upregulation of chemotactic factors at the injury site and the physical scaffolding provided by blood vessels. Cells of the neurovascular unit (neurons, astrocytes, and endothelial cells) and cells recruited from the systemic circulation produce chemotactic factors including but not limited to SDF-1α, BDNF, and VEGF (Behar et al., 1997; Imitola et al., 2004; Pencea et al., 2001; Robin et al., 2006; Thored et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007). Ohab and colleagues emphasized the importance of the neurovascular niche in which neural progenitors associate with vasculature to migrate to the site of ischemic damage, showing that capillary endothelial cells in the infarct area release factors like SDF-1 and Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) (Ohab et al., 2006). Under normal conditions, approximately half of the cells migrating to the olfactory bulb are in close proximity and contact with vasculature (Bovetti et al., 2007) and this association continues when cells are diverted from the RMS. Progenitors migrate to the ischemic injury using blood vessels as a scaffold and chemotactic factors as a guide (Ohab et al., 2006). SDF-1 in particular is a potent chemo-attractant, which is upregulated in the stroke infarct in a gradient fashion to guide migrating cells (Li et al., 2008a). Migration from the SVZ to the infarct occurs in chains and as individual cells (Zhang et al., 2009b). It was shown that neural progenitors extending from the border of the SVZ towards the infarcted striatum at a rate of 28.67±1.04 μm/h (Zhang et al., 2009b). Doublecortin (DCX)-positive migrating progenitor cells move along with and cluster around the vasculature. It was observed that 35% of progenitors were within 5 μm of a blood vessel.

Nonetheless, the neurogenic activity induced new cells usually do not survive well during the migration and after arrival at the injury site (Capowski et al., 2007; Daadi et al., 2008a; Kim et al., 2007a; Roy et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2008). The repair capability of newly formed neurons is very limited and does not suffice for an effective tissue repair after brain injury (Grégoire et al., 2015). For example, it was calculated that about 80% of the newly born neurons die in the striatum stroke model and that endogenous regeneration only replaces about 0.2% of dead striatal neurons (Arvidsson et al., 2002). Thus, the need for novel therapies to replace lost tissue is immense. Using the spatial and cell type specific optogenetic technique, we showed in a transgenic mouse expressing the light-gated channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) in glutamatergic neurons that optogenetic stimulation of the glutamatergic activity in the striatum triggered glutamate release into SVZ region, increased proliferation of SVZ neuroblasts mediated by AMPA receptor activation and Ca2+ increases in these cells. After stroke, optogenetic stimuli to the striatum for 8 days promoted cell proliferation and the migration of SVZ neuroblasts into the peri-infarct cortex with increased neuronal differentiation and improved long-term functional recovery. It was suggested that the striatum-SVZ neuronal regulation via a semi-phasic volume transmission mechanism may be a therapeutic target to directly promote SVZ neurogenesis after stroke(Song et al., 2017)(Song et al., 2017).

Trophic support and attenuation of inflammation

Adult and embryonic stem cells can enhance the survival of the surrounding tissue by providing trophic factor support. Trophic factors secreted by transplanted cells can provide trophic support to the injured parenchyma (Calió et al., 2014; Dillon-Carter et al., 2002; Johnston et al., 2001). As an example, a large proportion of neural stem cells transplanted into the murine cochlea were found to express neurotrophins such as GDNF and BDNF. The release of these factors provided protection and support to the surrounding cells (Bang, 2016; Iguchi et al., 2003).

Transplanted adult marrow-derived MSCs release cytokines and trophic or growth factors that have autocrine and paracrine effects (Caplan and Dennis, 2006; Haynesworth et al., 1996; Malgieri et al., 2010). MSCs have been shown to secrete colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1), stem cell factor, bFGF, nerve growth factor (NGF), and VEGF (Chen et al., 2002a; Labouyrie et al., 1999; Laurenzi et al., 1998; Majumdar et al., 1998; Villars et al., 2000). Such secreted factors reduce host cell death and attenuate inflammatory processes (Tse et al., 2003). Interestingly, injecting BMSC-conditioned media into the brain after stroke led to functional benefits, indicating that trophic support is a major mechanism by which MSCs contribute to functional recovery (Caplan and Dennis, 2006; Chen et al., 2002b; Li et al., 2002).

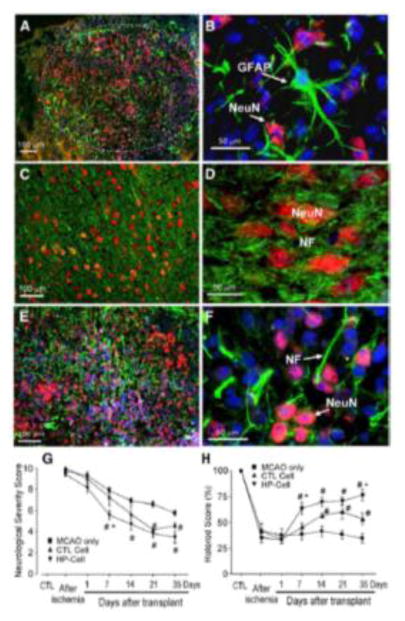

Cell differentiation, replacement and integration after transplantation

Cell differentiation and integration after transplantation is an important aspect of cell therapy. Neural cells have a greater potential to functionally integrate into the existing host circuitry if they differentiate into the appropriate neuronal phenotype (Lam et al., 2014). Several studies have examined the in vivo differentiation of transplanted stem cells (Fig. 8). In one systemic study, murine ES cell-derived neural precursors differentiated into different neuronal sub-types including cholinergic (1.4% of all grafted cells), serotonergic (1.8% of all grafted cells), GABAergic neurons (>50% of all grafted cells), and striatal neurons (1.4% of all grafted cells) after transplantation into the infarcted region. For the reason that is unclear, the percentage of excitatory glutamatergic neurons was not evaluated in this study. At 12 weeks after transplantation, 25% of the remaining transplanted cells were NeuN-positive while 8% were positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a marker of astrocytes. Transplanted cells also exhibited voltage-gated Na+, Ca2+ and K+ currents. While continued proliferation after transplantation was detected, no tumors were detected at 4 or 12 weeks (Buhnemann et al., 2006).

Figure 8. Neural differentiation of transplantation of ES-NPCs and functional benefits after stroke.