Abstract

The major protein associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD) is α-synuclein, as it can form toxic amyloid-aggregates that are a hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases. α-Synuclein is a substrate for several different posttranslational modifications (PTMs) that have the potential to affect its biological functions and/or aggregation. However, the biophysical effects of many of these modifications remain to be established. One such modification is the addition of the monosaccharide N-acetyl-glucosamine, O-GlcNAc, which has been found on several α-synuclein serine and threonine residues in vivo. We have previously used synthetic protein chemistry to generate α-synuclein bearing two of these physiologically relevant O-GlcNAcylation events at threonine 72 and serine 87 and demonstrated that both of these modifications inhibit α-synuclein aggregation. Here, we use the same synthetic protein methodology to demonstrate that these same O-GlcNAc modifications also inhibit the cleavage of α-synuclein by the protease calpain. This further supports a role for O-GlcNAcylation in the modulation of α-synuclein biology, as proteolysis has been shown to potentially affect both protein aggregation and degradation.

Keywords: O-GlcNAc, α-Synuclein, Calpain, Proteolysis, Parkinson’s disease

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

O-GlcNAc modification (O-GlcNAcylation) refers to the modification of serine or threonine side chains by the monosaccharide N-acetyl-glucosamine (Figure 1A).1,2 This posttranslational modification occurs on intracellular proteins and has been found in the nucleus, cytosol, and mitochondria. This modification is added by the enzyme O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and is removed by the enzyme O-GlcNAcase (OGA),3 neither which display a strong preference for any particular amino acid sequence. Many different classes of proteins are known to be modified by O-GlcNAc, including several of the proteins that are known to form toxic aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases,4 suggesting that O-GlcNAc may affect the normal and/or pathological functions of these proteins. Notably, Vocadlo and co-workers demonstrated that enzymatic O-GlcNAcylation of the microtubule stabilizing protein tau inhibited its aggregation in vitro.5 Furthermore, they developed a potent small-molecule inhibitor of OGA, Thiamet-G, that can raise O-GlcNAcylation levels in both cells and in vivo. Treatment of an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model with this inhibitor resulted in lower levels of tau hyperphosphorylation, a hallmark of tau aggregation, and fewer protein aggregates in the mouse brains.5,6 Together these results support a potential therapeutic strategy where increasing O-GlcNAcylation levels will slow protein aggregation and the progression of disease.

Figure 1.

O-GlcNAc modification and calpain cleavage of α-synuclein. (A) O-GlcNAc modification is the dynamic addition of N-acetyl-glucosamine to serine and threonine residues of intracellular proteins. (B) α-Synuclein, the major aggregating protein in Parkinson’s disease, is O-GlcNAcylated at several residues in vivo. (C) Monomeric α-synuclein has been shown to be proteolytically cleaved by the enzyme calpain after several residues.

We have focused on the roles of posttranslational modifications, including O-GlcNAcylation, on the aggregation and degradation of α-synuclein, the major aggregating protein in Parkinson’s disease (PD) and related Lewy body dementias.7 α-Synuclein is 140 amino acids in length and is enriched at pre-synaptic termini, where it appears to play a role in vesicle trafficking and membrane remodeling.8 α-Synuclein exists as a natively unstructured protein in the cytosol but will form an extended α-helix when it comes into contact with cellular membranes,9–11 and this equilibrium is likely important for its normal functions. During the progression of neurodegeneration, however, α-synuclein forms β-sheet rich aggregates that contain amyloid fibers.12 Several point mutants of α-synuclein that increase its aggregation have been identified that cause early-onset PD, demonstrating a causative role for this process in human disease.13–17 Notably, a growing set of data shows that these fibers can spread along neuronal connections where they can seed the aggregation of additional protein.18,19 α-Synuclein is subjected to a range of posttranslational modifications that can play important roles in PD.20 While enzymatic modification of α-synuclein has enabled the analysis of certain modifications, their site-specific installation using synthetic protein chemistry has played an instrumental role in the evaluation of modified α-synuclein biochemistry.21 For example, Brik, Lashuel, and we used protein chemistry to demonstrate that ubiquitination of α-synuclein can inhibit its aggregation and promote its degradation by the proteasome.22–25 We also used a similar chemical strategy to show that these effects are dependent on the site of modification and that the ubiquitin-like modifier SUMO will also inhibit α-synuclein aggregation.26 In the case of O-GlcNAcylation, a variety of in vivo proteomics experiments have identified many different O-GlcNAcylation sites on α-synuclein (Figure 1B).27–30 We have previously used synthetic protein chemistry to prepare α-synuclein with O-GlcNAcylation at two of these sites, threonine 72 (T72) and serine 87 (S87).31,32 Using a variety of biochemical experiments, we found that neither of these modifications inhibit the interaction of α-synuclein with membranes; however, both modifications inhibit protein aggregation, with O-GlcNAcylation at T72 having a stronger inhibitory effect.

Here, we use synthetic protein chemistry to explore the potential cross-talk between these modifications and another critical posttranslational modification of α-synuclein, proteolytic cleavage. While the majority of aggregated α-synuclein in the brains of PD patients is full-length, several truncations have been observed.33,34 Many of these cleavages remove the C-terminal region of α-synuclein and increase protein aggregation in vitro and in over expression experiments.35 Although it is not exactly clear which proteases are responsible for the cleavage of α-synuclein in vivo, several different enzymes have been implicated. One of those enzymes is the calcium-dependent protease calpain. Calpain has been shown to cleave soluble α -synuclein to generate several different fragments including C-terminal truncated forms, 1–57, 1–73, 1–75, and 1–83 (Figure 1C).36 Notably, these cleavage sites lie within the region of α-synuclein that is necessary for aggregation and therefore inhibit aggregation in vitro.37 Additionally, α-synuclein fibers can be cleaved near the C-terminus after residues 114 and 122, which promotes the seeded aggregation of additional soluble protein.37 The same α-synuclein fragments are found in PD brains where they co-localize with calpain,38 and the levels of calpain activity are correlated with disease progression in PD mouse models.39,40 Given, the close proximity of the some calpain cleavage sites to O-GlcNAc modification at T72 and S87, we chose to directly test if these O-GlcNAcylation events would affect α-synuclein proteolysis. To accomplish this goal, we first used an expressed protein ligation strategy to prepare site-specifically O-GlcNAcylated α-synuclein, which we then incubated with calpain. As expected, we found that this protease can rapidly cleave unmodified α-synuclein to generate the previously identified protein fragments. In contrast, both sites of O-GlcNAcylation strongly inhibited proteolysis, and the minor cleavage products that were formed differed between the two modified α-synuclein proteins. These results suggest that in addition to its direct inhibitory effect on protein aggregation, α-synuclein O-GlcNAcylation has the potential to inhibit α-synuclein proteolysis.

2. Results and Discussion

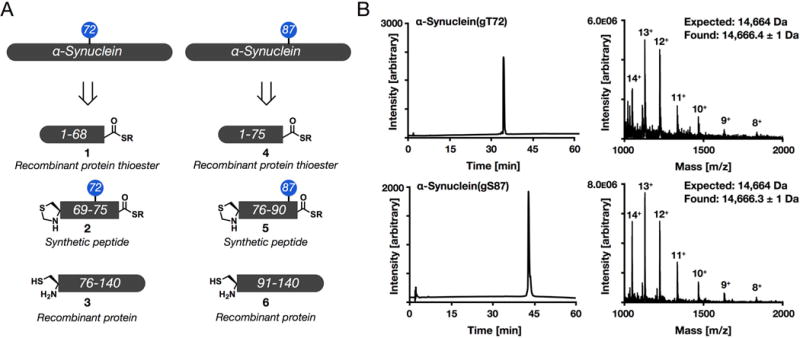

In order to prepare α-synuclein with O-GlcNAcylation at either T72 or S87, we followed our previously published synthetic routes. α-Synuclein O-GlcNAcylated at T72, α-synuclein(gT72), was retrosynthetically deconstructed (Figure 2A) into a recombinant protein thioester 1 consisting of residues 1–68, a synthetic O-GlcNAcylated peptide 2 (residues 69–75), and a recombinant protein 3 (residues 76–140) with an N-terminal cysteine residue. Likewise, α-synuclein(gS87) can be constructed (Figure 2A) from a recombinant protein thioester 4 (residues 1–75), a glycopeptide thioester 5 (residues 76–90), and a recombinant protein 6 corresponding to residues 91–140. For both proteins, the recombinant thioesters were prepared using intein-fusions. More specifically, the synuclein fragments were cloned as in-frame genetic fusions to an engineered DnaE intein from Anabaena variabilis and a histidine-tag for purification developed by the Muir lab.41 These proteins were heterologously expressed in E. coli, followed by purification by nickel chromatography, and thiolysis of the intein. The corresponding protein thioesters (1 and 4) where then isolated by RP-HPLC and concentrated by lyophilization. The glycopeptides 2 and 5 were prepared by solid phase peptide synthesis on commercially available Dawson Dbz resin, which enables the generation of peptide thioesters. Notably, these peptides contained a N-terminal thioproline residue to prevent auto-ligation. The O-GlcNAcylated serine and threonine building blocks were prepared from the corresponding Fmoc-protected amino acids and glucosamine using a thioglycoside approach.42 Recombinant proteins 3 and 6 were expressed in E. coli followed by RP-HPLC purification, and conveniently the initiator methionine residues were removed during expression. With these proteins in hand, iterative ligation reactions were carried out by first reacting fragments 2 and 3 or 5 and 6, followed by removal of the N-terminal protecting group. After purification by RP-HPLC these proteins were then incubated with the appropriate protein thioester (either 1 or 3) to give full-length α-synuclein. Finally, radical-based desulfurization was use to transform the cysteine residues required for the ligation reactions to the native alanine residues, resulting in α-synuclein(gT72) or α-synuclein(gS87) with no primary sequence mutations. These synthetic proteins were purified by RP-HPLC and the identities were confirmed by ESI-MS as previously described (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Synthesis of α-synuclein bearing site-specific O-GlcNAcylation. (A) α-Synuclein bearing an O-GlcNAc modification at either threonine 72 (T72) or serine 82 (S87) was retrosynthetically deconstructed into two recombinant proteins and a synthetic peptide that were assembled by native chemical ligation. (B) Both protein products were characterized by RP-HPLC and ESI-MS.

To determine if O-GlcNAcylation at T72 or S87 affected α-synuclein cleavage by calpain, we used both SDS-PAGE and RP-HPLC. Recombinant calpain (2 units mL−1) was incubated with 50 μM concentrations of either unmodified α-synuclein (from recombinant expression), α-synuclein(gT72), or α-synuclein(gS87) in HEPES buffer containing 5 mM DTT (pH = 7.2) at 37 °C for up to 30 min. After different lengths of time (0, 5, 10, 15, and 30 min), the enzymatic reactions were quenched by addition of SDS-containing loading buffer and heating to 100 °C for 10 min. The proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and then detected by colloidal silver staining and imaged on a ChemiDoc XRS (Bio-Rad) (Figure 3). As expected, wild-type α-synuclein was rapidly degraded while, α-synuclein(gT72) and α-synuclein(gS87) were very resistant to cleavage. Interestingly, the pattern of cleavage bands that appear at lower molecular weights are different for the two O-GlcNAcylated proteins, indicating that the site of the modification can play a role in the inhibition. In an effort to identify the calpain-dependent cleavage products that were formed, we also analyzed the enzymatic reaction by RP-HPLC and ESI-MS. The same reactions were initiated and allowed to proceed for 30 min. At this time, the reactions were quenched by heating at 100 °C for 10 min. Upon cooling, 100 uL of reaction was directly injected into the HPLC and fractions were collected for mass analysis (Figure 4). Consistent with SDS-PAGE, no full-length, unmodified α-synuclein was detected after 30 min of incubation with calpain. The major peaks detected in the unmodified cleavage reaction were analyzed by ESI-MS and corresponded to known cleavage sites of calpain after residues 57, 73, 75, and 83. Consistent with our SDS-PAGE analysis, full-length α-synuclein(gT72) and α-synuclein(gS87) were identified as the main peak in their respective chromatograms. The majority of the small cleavage products that were analyzed by ESI-MS did not produce strong signals due to their low abundance. However, we were able to identify cleavage of α-synuclein(gT72) after residue 33 and α-synuclein(gS87) after residue 57. Cleavage after residue 33 is notable, as it has not been observed from the proteolysis of unmodified α-synuclein.

Figure 3.

O-GlcNAcylation blocks the cleavage of α-synuclein by calpain. Unmodified α-synuclein or O-GlcNAcylated protein, α-synuclein(gT72) or α-synuclein(gS87), were incubated with calpain for the indicated lengths of time before termination of the enzymatic reaction by addition of SDS-loading buffer. The proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by colloidal silver staining.

Figure 4.

Identification of the α-synuclein-derived fragments after calpain cleavage. (A) Unmodified α-synuclein was incubated with calpain for 30 min and the enzymatic reaction was then quenched by heating to 100 °C. Protein fragments were then separated by RP-HPLC and identified using ESI-MS. (B and C) α-Synuclein(gT72) or α-synuclein(gS87) were subjected to calpain cleavage and analysis as in A.

3. Conclusion

Here, we have described the further application of synthetic protein chemistry to investigate the roles of posttranslational modifications on proteins. Specifically, we demonstrate that α-synuclein that has been site-specifically O-GlcNAcylated is notably resistant to cleavage by the enzyme calpain, which has been shown to proteolyze α-synuclein in vitro and potentially in PD. The exact consequences of calpain proteolysis are unknown in PD. α-Synuclein fragments that can result from calpain cleavage have been found in aggregates from diseased brains,38 but cleavage of α-synuclein at many of the sites in the middle of the protein are known to generate fragments that do not aggregate in vitro.37 In vivo models of PD show that calpain activity correlates with severity of the disease phenotype, but this could be due to reasons other than α-synuclein cleavage.39,40 Therefore, the exact physiological consequences of O-GlcNAc blockage of α-synuclein proteolysis is not clear. However, since O-GlcNAc directly inhibits protein aggregation, we believe that it should still be viewed as an overall protective modification. Additionally, we predict that O-GlcNAc could similarly inhibit the cleavage of α-synuclein by the as of yet unidentified proteases that generate aggregation-prone protein fragments of α-synuclein in PD. Notably, O-GlcNAcylation is able to inhibit α-synuclein cleavage at sites that are fairly distant in the primary protein sequence. For example, while α-synuclein(gS87) is only cleaved at low levels after residue 57. This suggests that O-GlcNAc is not simply acting as steric bulk in the active site of calpain. We believe that this is due to the natively unfolded nature of α-synuclein, which we predict can cause non-specific interactions with a variety of proteins. These interactions that mediate some of the binding to calpain could be distant from the protease active site, enabling other areas of α-synuclein to be cleaved. Our previous experiments with O-GlcNAcylation and protein aggregation indicate that this modification promotes the solubility of α-synuclein, which could explain our results here by preventing non-specific interactions with calpain. In summary, we have used synthetic protein chemistry to demonstrate that O-GlcNAcylation of α-synuclein can have site-specific inhibitory effects on its cleavage, with potentially important implications for the generation of aggregation-prone fragments in PD.

4. Experimental Section

4.1 Peptide Synthesis

All peptides were synthesized using standard Fmoc solid-phase chemistry on Dawson Dbz AM® (Novabiochem, 0.49 mmol g-1) resin using HBTU (5 eq, Novabiochem) and DIEA (10 eq, Sigma) in DMF for 1 hr. For activated glycosylated amino acids, 2 eq of monomer in 3 mL DMF was coupled overnight. When peptides were completed, acetyl groups were deprotected with hydrazine monohydrate (80% v/v in MeOH) twice for 30 min with mixing. Following deprotection, Dawson linker peptides were activated with p-nitrophenyl-chloroformate (5 eq in DCM, 1.5 hr, mixing) followed by treatment with excess DIEA (0.5 M in DMF) for 30 min to cyclize the Dbz linker. All peptides were then cleaved (95:2.5:2.5 TFA/H2O/Triisopropylsilane) for 3.5 h at room temperature, precipitated out of cold ether and lyophilized. Following lyophilization, crude peptides were resuspended in thiolysis buffer (150 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM MESNa, pH 7.0) and incubated at room temperature for 2 h prior to purification. All peptides were purified by reverse-phase HPLC using preparative chromatography, characterized by mass analysis using ESI-MS, and sequence purity was assessed by analytical HPLC.

4.2 Protein Expression and Purification

General expression and purification methods were similar to those previously reported. Briefly, BL21(DE3) chemically competent E. coli (VWR) were transformed with plasmid DNA by heat shock and plated on selective LB agar plates containing 50 μg mL-1 kanamycin (C-terminus) or 100 μg mL-1 ampicillin (N-terminus). Single colonies were then inoculated, grown to OD600 of 0.6 at 37 °C shaking at 250 rpm, and then expression was induced with IPTG (final concentration: 0.5 mM) at 25 °C shaking at 250 rpm for 18 h. Pellets were harvested by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C) and lysed. C-terminus was acidified (pH 3.5 with HCl), centrifuged, dialyzed against 3 × 1 L of 1% acetic acid in water (degassed with N2, 1 hr per L), and purified by HPLC. N-terminus was loaded onto a Ni-NTA purification column (HisTrap FF Crude, GE Healthcare) and eluted fractions were dialyzed against 3 × 1 L (100 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1mM TCEP HCl, pH 7.2) and concentrated. Sodium mercaptoethane sulfonate (MESNa) was added to a final concentration of 200 mM along with fresh TCEP (2 mM final concentration) overnight to generate the protein thioester, and then purified by HPLC. Pure protein fragments were characterized by analytical RP-HPLC and ESI-MS.

4.3 Expressed Protein Ligation

General ligation and purification methods were similar to those previously reported. Briefly, C-terminal fragment (2 mM) and peptide fragment (4 mM) were dissolved in ligation buffer (300 mM NaH2PO4, 6 M guanidine HCl, 100 mM MESNa, 1 mM TCEP, pH 7.8) and allowed to react at room temperature. Following completion, as monitored by HPLC, the pH was adjusted to 4 with HCl and methoxylamine was added (final concentration 100 mM) to deprotect the N-terminal thiazolidine group. Following HPLC purification, N-terminal fragment (8 mM) and ligation product fragment (2 mM) were dissolved in ligation buffer, and following completion was purified by HPLC. Finally, radical desulfurization was carried out using desulfurization buffer (200 mM NaH2PO4, 6 M guanidine HCl, 300 mM TCEP, pH 7.0) containing 2% v/v ethanethiol, 10% v/v tertbutyl-thiol, and the radical initiator VA-061 (as a 0.2 M stock in MeOH). The reaction was heated to 37 °C for 15 h and then purified by RP-HPLC to yield synthetic α-synuclein.

4.4 Proteolysis Reaction

Cleavage of purified α-synuclein proteins (50 μM, 150 μL reaction volume) was carried out using calpain (EMD Millpore, 2 units mL−1) in buffer containing 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and 5 mM dithiothreitol at 37 °C. Calpain cleavage was initiated by the addition of calcium (1 mM final concentration). Aliquots were removed from the reaction mixture and quenched with SDS-containing loading buffer at various time points, heated at 100 °C for 10 min, and stored at −20 °C until SDS-PAGE was performed.

4.5 Silver Staining

SDS-PAGE was performed using 16.5% Criterion Tris-Tricine polyacrylamide precast gels. Silver staining of the gels was performed in accordance with the instructions provided in the Pierce Silver Stain Plus. Briefly, the resolved proteins were fixed by incubating the gel in 200 ml of fixative enhancer solution (30% ethanol, 10% acetic acid, 60% deionized distilled water) for 30 min at 25 °C. Following that, the gel was rinsed twice with 10% ethanol for 10 min and twice with 10% deionized distilled water for 10 min. Gel was then subjected to sensitizer solution (100uL sensitizer in 50 mL deionized distilled water) for 1 minute followed by washing with deionized distilled water for 2 min. Next, gel was stained (1 mL enhancer in 50 mL stain solution) for 30 min followed by washing with deionized distilled water for 1 min. Lastly, gel was developed (1 mL enhancer in 50 mL developer) for 2 min followed by a 5% acetic acid wash for 10 min. Stained gel was then imaged using ChemiDoc XRS (Bio-Rad).

4.6 HPLC/ESI-MS Analysis

Reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) analysis was performed on digested proteins following a 30 minute incubation with calpain. Briefly, the reactions were quenched by heating to 100 °C for 30 min followed by direct injection onto the HPLC (0–70% buffer B over 60 min). The chromatogram was monitored at 210 nm and fractions were collected for ESI-MS. Each individual fraction was then acquired on an API 3000 LC/MS-MS system to identify the corresponding cleaved peptide products. buffer A: 0.1% TFA in H2O, buffer B: 0.1% TFA, 90% ACN in H2O.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM114537 to M.R.P.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zachara NE, Hart GW. Chem Rev. 2002;102:431–438. doi: 10.1021/cr000406u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bond MR, Hanover JA. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:869–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vocadlo DJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuzwa SA, Vocadlo DJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:6839–6858. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00038b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuzwa SA, Shan X, Macauley MS, Clark T, Skorobogatko Y, Vosseller K, Vocadlo DJ. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:393–399. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuzwa SA, Macauley MS, Heinonen JE, Shan X, Dennis RJ, He Y, Whitworth GE, Stubbs KA, McEachern EJ, Davies GJ, Vocadlo DJ. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:483–490. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lashuel HA, Overk CR, Oueslati A, Masliah E. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrn3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emanuele M, Chieregatti E. Biomolecules. 2015;5:865–892. doi: 10.3390/biom5020865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jao CC, Hegde BG, Chen J, Haworth IS, Langen R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19666–19671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807826105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varkey J, Isas JM, Mizuno N, Jensen MB, Bhatia VK, Jao CC, Petrlova J, Voss JC, Stamou DG, Steven AC, Langen R. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32486–32493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizuno N, Varkey J, Kegulian NC, Hegde BG, Cheng N, Langen R, Steven AC. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:29301–29311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink AL. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:628–634. doi: 10.1021/ar050073t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, Stenroos ES, Chandrasekharappa S, Athanassiadou A, Papapetropoulos T, Johnson WG, Lazzarini AM, Duvoisin RC, Di Iorio G, Golbe LI, Nussbaum RL. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krüger R, Kuhn W, Müller T, Woitalla D, Graeber M, Kösel S, Przuntek H, Epplen JT, Schöls L, Riess O. Nature Genet. 1998;18:106–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarranz JJ, Alegre J, Gómez-Esteban JC, Lezcano E, Ros R, Ampuero I, Vidal L, Hoenicka J, Rodriguez O, Atarés B, Llorens V, Gomez Tortosa E, del Ser T, Muñoz DG, de Yebenes JG. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:164–173. doi: 10.1002/ana.10795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chartier-Harlin M-C, Kachergus J, Roumier C, Mouroux V, Douay X, Lincoln S, Levecque C, Larvor L, Andrieux J, Hulihan M, Waucquier N, Defebvre L, Amouyel P, Farrer M, Destée A. Lancet Neurol. 2004;364:1167–1169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Peuralinna T, Dutra A, Nussbaum R, Lincoln S, Crawley A, Hanson M, Maraganore D, Adler C, Cookson MR, Muenter M, Baptista M, Miller D, Blancato J, Hardy J, Gwinn-Hardy K. Science. 2003;302:841. doi: 10.1126/science.1090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brettschneider J, Tredici KD, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:109–120. doi: 10.1038/nrn3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recasens A, Dehay B. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:159. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oueslati A, Fournier M, Lashuel HA. Prog Brain Res. 2010;183:115–145. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)83007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pratt M, Abeywardana T, Marotta N. Biomolecules. 2015;5:1210–1227. doi: 10.3390/biom5031210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hejjaoui M, Haj-Yahya M, Kumar KSA, Brik A, Lashuel HA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;50:405–409. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haj-Yahya M, Fauvet B, Herman-Bachinsky Y, Hejjaoui M, Bavikar SN, Karthikeyan SV, Ciechanover A, Lashuel HA, Brik A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:17726–17731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315654110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier F, Abeywardana T, Dhall A, Marotta NP, Varkey J, Langen R, Chatterjee C, Pratt MR. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5468–5471. doi: 10.1021/ja300094r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abeywardana T, Lin YH, Rott R, Engelender S, Pratt MR. Chem Biol. 2013;20:1207–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abeywardana T, Pratt MR. Biochemistry. 2015;54:959–961. doi: 10.1021/bi501512m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Udeshi ND, O’Malley M, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Hart GW. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:153–160. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900268-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alfaro JF, Gong C-X, Monroe ME, Aldrich JT, Clauss TRW, Purvine SO, Wang Z, Camp DG, Shabanowitz J, Stanley P, Hart GW, Hunt DF, Yang F, Smith RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:7280–7285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200425109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z, Park K, Comer F, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Saudek CD, Hart GW. Diabetes. 2009;58:309–317. doi: 10.2337/db08-0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris M, Knudsen GM, Maeda S, Trinidad JC, Ioanoviciu A, Burlingame AL, Mucke L. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1183–1189. doi: 10.1038/nn.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marotta NP, Lin YH, Lewis YE, Ambroso MR, Zaro BW, Roth MT, Arnold DB, Langen R, Pratt MR. Nat Chem. 2015;7:913–920. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis YE, Galesic A, Levine PM, De Leon CA, Lamiri N, Brennan CK, Pratt MR. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:1020–1027. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, West N, Colla E, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Marsh L, Dawson TM, Jäkälä P, Hartmann T, Price DL, Lee MK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2162–2167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406976102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu C-W, Giasson BI, Lewis KA, Lee VM, Demartino GN, Thomas PJ. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22670–22678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson JP, Walker DE, Goldstein JM, de Laat R, Banducci K, Caccavello RJ, Barbour R, Huang J, Kling K, Lee M, Diep L, Keim PS, Shen X, Chataway T, Schlossmacher MG, Seubert P, Schenk D, Sinha S, Gai WP, Chilcote TJ. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29739–29752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mishizen-Eberz AJ, Guttmann RP, Giasson BI, Day GA, III, Hodara R, Ischiropoulos H, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ, Lynch DR. J Neurochem. 2003;86:836–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mishizen-Eberz AJ, Norris EH, Giasson BI, Hodara R, Ischiropoulos H, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ, Lynch DR. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7818–7829. doi: 10.1021/bi047846q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dufty BM, Warner LR, Hou ST, Jiang SX, Gomez-Isla T, Leenhouts KM, Oxford JT, Feany MB, Masliah E, Rohn TT. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1725–1738. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crocker SJ, Smith PD, Jackson-Lewis V, Lamba WR, Hayley SP, Grimm E, Callaghan SM, Slack RS, Melloni E, Przedborski S, Robertson GS, Anisman H, Merali Z, Park DS. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4081–4091. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04081.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diepenbroek M, Casadei N, Esmer H, Saido TC, Takano J, Kahle PJ, Nixon RA, Rao MV, Melki R, Pieri L, Helling S, Marcus K, Krueger R, Masliah E, Riess O, Nuber S. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:3975–3989. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah NH, Dann GP, Vila-Perelló M, Liu Z, Muir TW. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11338–11341. doi: 10.1021/ja303226x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marotta NP, Cherwien CA, Abeywardana T, Pratt MR. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:2665–2670. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]