Abstract

Hemangioblastomas (HBs) are uncommon tumors characterized by the presence of inactivating alterations in the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene in inherited cases and by infrequent somatic mutation in sporadic entities. We performed whole exome sequencing on 11 HB patients to further elucidate the genetics of HBs. A total of 270 somatic variations in 219 genes, of which there were 86 mutations in 67 genes, were found in sporadic HBs, and 184 mutations were found in 154 genes in familial HBs. C: G>T: A and T: A>C: G mutations are relatively common in most HB patients. Genes harboring the most significant mutations include PCDH9, KLHL12, DCAF4L1, and VHL in sporadic HBs, and ZNF814, DLG2, RIMS1, PNN, and MUC7 in familial HBs. The frequency of CNV varied considerably within sporadic HBs but was relatively similar within familial HBs. Five genes, including OTOGL, PLCB4, SCEL, THSD4 and WWOX, have CNVs in the six patients with sporadic HBs, and 3 genes, including ABCA6, CWC27 and LAMA2, have CNVs in the five patients with familial HBs. We found new genetic mutations and CNVs that might be involved in HBs; these findings highlight the complexity of the tumorigenesis of HBs and pinpoint potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of HBs.

Keywords: Hemangioblastomas, von Hippel-Lindau gene, whole exome sequencing, copy number variation, single nucleotide variant

Introduction

Hemangioblastomas (HBs) are highly vascularized neoplasms; they account for only 1–2.5% of all tumors in the central nervous system (CNS) [Conway and others 2001; Hussein 2007; Lonser and others 2003]. They often reside in a strikingly limited subset of CNS locations, including the cerebellum, brainstem, retina, and spinal cord. Due to their unique location and the existence of rich vascular networks in these areas, HBs can cause bleeding and rupture, or they can become symptomatic with/without an associated cyst. Therefore, CNS-HBs are a major cause of morbidity and mortality [Shehata and others 2008].

HBs are benign tumors with characteristic and well-described histopathological features, including rapid proliferation of vascular and stromal cells, which are regarded as the underlying neoplastic cells [Hussein 2007]. However, the ontogenesis of HBs remains a mystery for nearly a century since the discovery of HBs. Consequently, the World Health Organization has not classified HBs as neoplasms [Louis and others 2007]. Accordingly, exploration of the oncogenesis of HB will not only shed light on its etiology, pathology, and diagnosis, it will also provide useful insight into treating it.

HBs occur sporadically or in von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. Although there are vast differences between the two subtypes of HBs in terms of genetics, age of onset, clinic recurrence, and other involved organs, they share identical histopathology. Germline mutations or aberrations in the VHL gene have been identified as the root cause of VHL disease. It has been estimated that only approximately 4% of VHL gene carriers are asymptomatic [Beitner and others 2011; Catapano and others 2005], with CNS-HBs occurring in up to 60–80% of VHL patients [Maher and others 1990; Richard and others 2000; Wanebo and others 2003]. It is also thought that there were 4–25% of seemingly sporadic HBs are VHL somatic mutations [Fukino and others 2000; Hes and others 2000; Neumann and others 1989]. These observations indicate that a dysfunctional or absent VHL protein (pVHL) could be involved in the tumorigenesis of HB, but it alone might not be enough to induce the lesions [Ma and others 2011; Nordstrom-O’Brien and others 2010]. Additional genetic variations that may contribute to the tumorigenesis of HB have not yet been identified [Nordstrom-O’Brien and others 2010; Sims 2001].

Furthermore, identified mutations span the entire VHL gene and occur in nearly every codon [Nordstrom-O’Brien and others 2010]. Dysfunctional or absent pVHL has organ-specific expression and age-dependent penetrance. Moreover, different types of VHL mutations could also influence tumorigenesis. For example, VHL deletions and protein truncating mutations appear to confer a higher risk of CNS-HBs than missense mutations [Cybulski and others 2002; Franke and others 2009; Maher and others 1996; Maranchie and others 2004]. Previous studies have indicated the importance of different pathways in the development of HB neoplasms as well as the existence of additional unknown genetic alterations that might drive disease progression [Dulaimi and others 2004]. In this study, we performed a whole exome sequencing to explore the possible genetic variations that may contribute to the tumorigenesis of HBs.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

Eleven HB samples and the corresponding peripheral blood samples (including six sporadic HBs and five familial HBs, respectively) were selected randomly from the sample bank in the Department of Neurosurgery, Huashan Hospital, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University. These patients underwent resection of CNS-HBs between November 2008 and June 2015 at our hospital. All the specimens were ultimately diagnosed by experienced neuropathologists. The five patients with familial HBs were from three families. All of the familial HB patients had a family history of HBs, and VHL mutations were identified in genetic testing. All the sporadic HB patients had no family history of HB, showed no clinical signs of VHL HBs, and did not show any VHL mutation. This research was approved by the institutional review board of Huashan Hospital (KY2009-313). Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Extraction of DNA

In this study, the sample detection included concentration, sample integrity and purification of the extracted DNA. Concentration was detected using a fluorometer or a Microplate Reader (Qubit Fluorometer, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Sample integrity and purification were detected by Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (concentration of agarose gel: 1%, voltage: 150 V, electrophoresis time: 40 min). Library construction followed the standard commercial guidelines. Briefly, 1 μg–2μg of genomic DNA was randomly fragmented using Covaris AFA process to an average size of 250–300 bp. Fragments were end repaired, and an extra A base was added to the 3′ end. Illumina adaptors were ligated to the fragments, and proper cycles of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification were applied to each sample after ligation. DNA was quantified using either Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer or the Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). We used the required amount of pre-capture library for each capture reaction. Agilent SureSelect, NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Hybridization and Wash kits (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) were used for whole-exome capture following the standard manufacturer’s protocol.

Exome Capture and Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the tumor and blood of each of the 11 patients, and then it was fragmented randomly. After electrophoresis, DNA fragments of the desired length were gel purified. Adapter ligation and DNA cluster preparation were performed and the samples were subjected to Solexa sequencing [Mardis 2008; Wang and others 2008; Wheeler and others 2008]. WES was performed using the Complete Genomics (CG) platform, which utilizes two proprietary technologies, DNA nanoball (DNB) sequencing and combinatorial probe-anchor ligation (cPAL). The results showed a high concordance with the Illumina platform and a high sensitivity [Lam and others 2012; Porreca 2010]. To minimize the likelihood of systematic bias in the sampling, two paired-end libraries with an insertion size of 500 bp were prepared for all the samples and then they subjected to whole exome sequencing. This resulted in at least 30-fold haploid coverage for each sample. Raw image files were processed using the Illumina pipeline for base calling with default parameters, and the whole exome sequences of each individual patient were generated as 90-bp-paired-end reads.

We used the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner program [Li and Durbin 2009] to map the raw sequencing data for each individual to the human reference genome (build hg19). We then used Picard to sort and mark duplicated reads. Gene mutations or alterations in peripheral blood were considered to be nonspecific genetic variations and were excluded from the final analyses. The SNVs were detected by VarScan [Koboldt and others 2009]. P-values were calculated by Fisher’s exact test on the read counts, using reference and variant allele [Koboldt and others 2009]. The CNVs of the normal samples and the tumor samples were detected by in-house pipeline CNV-Detection (BGI-Tech, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) based on the Broad Institute’s Segseq algorithm [Chiang and others 2009]. Segseq can detect breakpoints at any read position. The segments were iteratively joined by eliminating the breakpoints. Statistical significance was calculated based on the number of reads in the tumor and normal samples in the entire segment. This enables a more accurate estimation of statistical significance because of the increased number of aligned reads [Chiang and others 2009]. We then used ANNOVAR to annotate the variant results [Wang and others 2010], based on which subsequent advanced analysis could be conducted. Quality control (QC) was performed at each stage of the analysis pipeline.

Results

Basic Characteristics of the Study Participants

The basic characteristics of the 11 study participants are presented in Table 1. Six of the participants had sporadic HB, and five had familial HB. Of the participants with familial HB, patient 21 and 23 came from the same family while patient 24 and 25 were from a different family. Four of the patients were female (three had sporadic HB and one had familial HB), and the HBs appeared in different locations.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the HB patients.

| Patient ID | Age | Sex | Type of HB | Features of HB (location and VHL-related presentation) | Family history of HB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 60 | F | Sporadic | Left cerebellum HB | No |

| 12 | 26 | F | Sporadic | Fourth veutficula HB | No |

| 13 | 56 | M | Sporadic | Cerebellum HB | No |

| 14 | 56 | M | Sporadic | Left CPA HB | No |

| 15 | 59 | M | Sporadic | Right cerebellum HB | No |

| 16 | 47 | F | Sporadic | Left cerebellum HB | No |

| 21 | 47 | F | Familial HB | Posterior cranial fossa HBs (bilateral renal cell carcinoma) | Yes, mother |

| 22 | 32 | M | Familial HB | T6–7 HB (5 yrs after cerebellum HB operation, multiple cysts in the left kidney and pancreas) | Yes, father and sister |

| 23 | 25 | M | Familial HB | Multiple HBs in medulla oblongata and cerebellum sample from the cerebellum | Yes, mother |

| 24 | 39 | M | Familial HB | Cerebellum HB | Yes, mother and sister |

| 25 | 25 | M | Familial HB | Multiple cranial HBs in sample from the cerebellum | Yes, mother and cousin |

CPA, ; VHL, ; F, female; M, Male; HB, hemangioblastoma

Single Nucleotide Variation

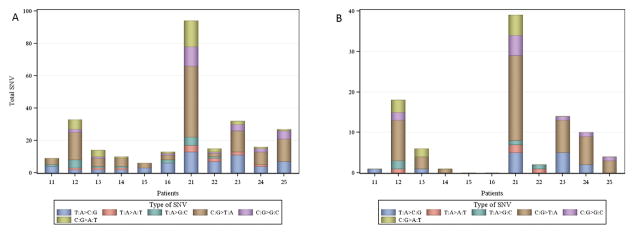

We identified a total of 270 somatic single nucleotide variation (SNV) mutations in the 11 tumors, of which 67 (26.8%) might affect protein coding (61 missense, five nonsense and one splice site; Table 2). These 270 somatic mutations are in 219 genes, with four genes (MAP4K3, NBPF20, PGM5, and ZNF814) having two mutations and 47 mutations located in intergenic regions. We found that, for most of the patients in this study, C: G>T: A transitions were the most common mutation in individual HB samples; however, the T: A>C: G mutation were also very common in many HB patients (Fig. 1A). Some patients, such as patient 12 and patient 21, have more mutations in the coding regions (Fig. 1B). An examination based on HB type indicated that there were 86 mutations in the patients with sporadic HBs (mean 14.3), of which 51 represent novel mutations, and 184 mutations in the patients with familial HBs (mean 36.8), of which 139 represent novel mutations (Table 2). The 86 mutations in the sporadic HBs are in 67 genes with 19 mutations in the intergenic regions (Supplementary Fig. 1). The 184 mutations in the familial HBs are in 154 genes with two genes (MAP4K3 and ZNF814) having two mutations each and 28 mutations in the intergenic regions (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Somatic single nucleotide variants in patients with HBs.

| Patients | Missense | Nonsense | Splice site | Other | Total mutation | Novel mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 1 |

| 12 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 19 | 33 | 29 |

| 13 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14 | 9 |

| 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 11 | 10 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 2 |

| Total | 16 | 2 | 1 | 67 | 86 | 51 |

| 21 | 27 | 2 | 0 | 65 | 94 | 81 |

| 22 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 15 | 5 |

| 23 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 23 | 32 | 29 |

| 24 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 16 | 12 |

| 25 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 27 | 12 |

| Total | 45 | 3 | 0 | 136 | 184 | 139 |

Patients 11–16 were those with sporadic HBs, and patient 21–25 were those with familial HBs.

HB, hemangioblastomas.

Fig. 1. Distribution of single nucleotide variants in patients with HBs.

A: Distribution of all single nucleotide variants.

B: Distribution of single nucleotide variants in coding regions.

Patients 11–16 were those with sporadic HBs, and patient 21–25 were those with familial HBs.

HB, hemangioblastoma; SNV, single nucleotide variant

Genes with the Most Significant Mutations

For sporadic HBs, the most significant mutation (c.2639C>G; p=3.22×10−11) is found in the PCDH9 gene. Other genes harboring strongly significant mutations for familial HBs include KLHL12, DCAF4L1, and VHL (all p<5×10−8). For familial HBs, the most significant mutation (c.1010C>T; p=6.18×10−40) is found in the ZNF814 gene, which also harbors a synonymous mutation (p=1.01×10−22). Other genes harboring strongly significant mutations for familial HBs include DLG2, RIMS1, PNN and MUC7 (all p<5×10−19; for the complete list of significant mutations, please see online Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2).

Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 schematically illustrate two identified somatic mutation networks for sporadic HBs and familial HBs, respectively. In sporadic HBs, we identified several statistically significant networks that are involved in different functions, such as the spliceosomal complex (P=3.77×10−5) and RNA splicing (P=1.66×10−4). In the VHL HBs, we did not identify any network that was found to be statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate.

Copy Number Variations

We detected a large number of copy number variations (CNVs) in all the HB samples across the chromosomes. Specifically, we identified a total of 26,072 CNVs in patients with sporadic HB (Supplementary Fig. 5) and 8,000 CNVs in patients with familial HBs (Supplementary Fig. 6). The frequency of CNVs varied considerably among patients with sporadic HBs: one patient (patient 13) had 13,310 CNVs and one patient (patient 15) had 4,167 CNVs, while patient 16 only had 707 CNVs across the genome. In contrast, the frequency of CNVs was generally lower and relatively similar among patients with familial HB: on average, there were 1,600 CNVs per patient; patient 21 had the smallest number of CNVs (1358) and patient 22 had the largest number of CNVs (1,901).

We identified five genes, OTOGL, PLCB4, SCEL, THSD4, and WWOX, which has CNVs in the six patients with sporadic HB (Table 3). We identified three genes, ABCA6, CWC27, and LAMA2, with CNVs in the five patients with familial HBs (Table 4).

Table 3.

The five genes having CNV in all of the six patients with sporadic HBs.

| Gene | Chr | Start | End | Copy Ratio | Type | Patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTOGL | 12 | 80707425 | 80714079 | 1.70 | amplification | 11 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80764407 | 80765658 | 1.99 | amplification | 11 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80661063 | 80665359 | 0.66 | deletion | 12 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80730572 | 80732809 | 0.53 | deletion | 12 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80496991 | 80605596 | 1.71 | amplification | 13 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80660659 | 80663966 | 1.26 | amplification | 13 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80750095 | 80831570 | 1.26 | amplification | 14 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80672958 | 80703998 | 0.60 | deletion | 15 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80707447 | 80714034 | 0.63 | deletion | 15 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80714535 | 80717256 | 0.45 | deletion | 15 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80752478 | 80761196 | 0.59 | deletion | 15 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80762203 | 80770863 | 0.71 | deletion | 15 |

| OTOGL | 12 | 80722584 | 80726771 | 1.31 | amplification | 16 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 9255315 | 9317733 | 1.38 | amplification | 11 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 9353750 | 9364815 | 1.45 | amplification | 11 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 9215047 | 9317649 | 0.69 | deletion | 12 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 9449377 | 9453533 | 0.61 | deletion | 12 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 8862743 | 9287807 | 1.89 | amplification | 13 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 9287952 | 9364795 | 1.28 | amplification | 13 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 9382481 | 9388309 | 1.48 | amplification | 13 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 9343176 | 9351983 | 1.36 | amplification | 14 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 9346283 | 9364729 | 0.74 | deletion | 15 |

| PLCB4 | 20 | 9299560 | 9318813 | 1.32 | amplification | 16 |

| SCEL | 13 | 78137954 | 78143397 | 1.35 | amplification | 11 |

| SCEL | 13 | 78201874 | 78210222 | 0.45 | deletion | 12 |

| SCEL | 13 | 77904169 | 78124018 | 2.00 | amplification | 13 |

| SCEL | 13 | 78133951 | 78142864 | 1.28 | amplification | 13 |

| SCEL | 13 | 78130942 | 78133692 | 0.60 | deletion | 14 |

| SCEL | 13 | 78178371 | 78217054 | 1.32 | amplification | 14 |

| SCEL | 13 | 78176890 | 78191481 | 0.73 | deletion | 15 |

| SCEL | 13 | 78196903 | 78208368 | 0.50 | deletion | 15 |

| SCEL | 13 | 78042366 | 78125039 | 1.38 | amplification | 16 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71548883 | 71581017 | 0.69 | deletion | 11 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71704021 | 71731836 | 0.67 | deletion | 11 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71903510 | 71939503 | 0.55 | deletion | 12 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71411565 | 71446614 | 1.68 | amplification | 13 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71550735 | 71630571 | 1.57 | amplification | 13 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71634234 | 71700371 | 1.58 | amplification | 13 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71704946 | 71834240 | 1.90 | amplification | 13 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71834244 | 71950228 | 1.35 | amplification | 13 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71953052 | 72020695 | 1.68 | amplification | 13 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 72037749 | 72041318 | 0.68 | deletion | 14 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 71603850 | 71633595 | 0.66 | deletion | 15 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 72039196 | 72050246 | 0.73 | deletion | 16 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78285500 | 78323808 | 1.40 | amplification | 11 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78267224 | 78289780 | 0.56 | deletion | 12 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78083567 | 78142310 | 1.40 | amplification | 13 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78151058 | 78387973 | 1.54 | amplification | 13 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78466792 | 78789897 | 1.64 | amplification | 13 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78792488 | 78859135 | 1.68 | amplification | 13 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78867130 | 79245296 | 1.65 | amplification | 13 |

| WWOX | 16 | 79246081 | 79340769 | 1.76 | amplification | 13 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78128470 | 78136040 | 0.48 | deletion | 14 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78466467 | 78482962 | 1.27 | amplification | 15 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78642591 | 78714289 | 1.41 | amplification | 16 |

| WWOX | 16 | 78873601 | 79034196 | 1.26 | amplification | 16 |

CNV, copy number variation

Table 4.

The three genes having CNV in all of the five patients with familial HBs.

| Gene | Chr | Start | End | Copy Ratio | Type | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA6 | 17 | 67091701 | 67101720 | 1.32 | amplification | 21 |

| ABCA6 | 17 | 67087558 | 67101675 | 1.28 | amplification | 22 |

| ABCA6 | 17 | 67110783 | 67124511 | 1.30 | amplification | 22 |

| ABCA6 | 17 | 67060848 | 67077218 | 0.72 | deletion | 23 |

| ABCA6 | 17 | 67114246 | 67120997 | 1.28 | amplification | 24 |

| ABCA6 | 17 | 67098740 | 67101581 | 0.60 | deletion | 25 |

| CWC27 | 5 | 64081466 | 64084760 | 1.63 | amplification | 21 |

| CWC27 | 5 | 64079888 | 64110852 | 1.38 | amplification | 22 |

| CWC27 | 5 | 64064936 | 64070739 | 0.65 | deletion | 23 |

| CWC27 | 5 | 64291614 | 64313873 | 0.63 | deletion | 24 |

| CWC27 | 5 | 64096124 | 64100055 | 0.71 | deletion | 25 |

| LAMA2 | 6 | 129419549 | 129467874 | 1.44 | amplification | 21 |

| LAMA2 | 6 | 129475563 | 129478619 | 1.61 | amplification | 21 |

| LAMA2 | 6 | 129591600 | 129601349 | 1.53 | amplification | 22 |

| LAMA2 | 6 | 129774271 | 129777347 | 1.68 | amplification | 22 |

| LAMA2 | 6 | 129475586 | 129478619 | 0.62 | deletion | 23 |

| LAMA2 | 6 | 129794354 | 129799655 | 1.47 | amplification | 24 |

| LAMA2 | 6 | 129377950 | 129389401 | 0.67 | deletion | 25 |

CNV, copy number variation

Discussion

In this study, we performed whole exome sequencing (WES) on six patients with sporadic HBs and five patients with familial HBs to explore the potential genetic variations that may contribute to the tumorigenesis of HBs. We identified many mutations, the majority of which represent novel mutations, in both sporadic HBs and familial HBs. We found a large number of CNVs in many patients with sporadic HBs, but fewer CNVs in patients with familial HBs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first WES study to examine potential genetic variations for HBs.

Nowadays, WES has become a very powerful strategy in the discovery of rare causal variants of inherited diseases and in the identification of additional somatic genetic variations that may account for unexplained heritability [Cirulli and Goldstein 2010]. In this study, we screened and identified a number of potential new mutations in patients with HBs. For example, in patients with familial HBs, we found mutations in ZNF814, DLG2, RIMS1, PNN, and MUC7. Further studies are needed to examine whether andhow these additional genetic mutations contribute to HB tumorigenesis and if they are associated with age-dependent penetrance of HBs with synergetic inactivation of VHL. In sporadic HBs, we found the most significant mutations in PCDH9, KLHL12, and DCAF4L1 but not in VHL. The exact roles of these genetic mutations need to be elucidated. Taken together, our findings provide additional insights into the genetic basis of HBs, and they enhance our understanding of the complexity of the clinical phenotypes of HBs.

CNVs are considered to be a significant source of genetic diversity, and they can influence phenotypic variability, such as disease susceptibility[Diskin and others 2009]. Many of the genes harboring the identified genetic variations are also implemented in different tumor-related pathways. For example, we found CNVs in WW domain-containing oxidoreductase (WWOX) in the six patients with sporadic HBs. WWOX is located at 16q23.3–24.1, an area with a high frequency of gene deletions or chromosomal alterations. WWOX is a tumor suppressor gene that regulates multiple cancer-related pathways [Aqeilan and Croce 2007; Salah and others 2010]. It exerts its cancer-suppressing function by suppressing the carcinogenic effects of oncogenes [Gaudio and others 2006], and/or by inducing cell apoptosis via activation of other tumor suppressor genes[Aqeilan and others 2004]. WWOX loses its expression in various tumors [Lewandowska and others 2009]. Previous studies have reported that the CNVs in WWOX are associated with increased risk of lung cancer and gliomas in a Chinese population [Yang and others 2013; Yu and others 2014]. We found that there were five common CNVs in WWOX (http://dgv.tcag.ca/dgv/app/home?ref=GRCh37/hg19), none of which were among the list of CNVs that we identified in patients with sporadic HBs. Therefore, the CNVs we found in this study represent novel CNVs in WWOX that might be involved in the function of WWOX with respect to its role in cancer suppression and HB-tumorigenesis for sporadic HBs. Importantly, because the CNVs we identified in WWOX did not occur in the matched peripheral blood DNA, the occurrence of CNVs in WWOX within sporadic HBs might be due to acquired environment influences. Future studies are needed to explore the potential mechanism of the identified CNVs in influencing the function of WWOX.

A recent study identified a reverse relationship between CNVs and mutations in 12 types of cancer such as glioblastoma multiformae and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and it found that tumors can roughly be divided into two classes based on somatic genetic variations: the M class predominantly has mutations while the C class predominantly has CNVs [Ciriello and others 2013]. Overall all, we found a large number of CNVs (mean=4345) but a relatively smaller number of mutations (mean= 14) in patients with sporadic HBs; in contrast, we found significantly fewer CNVs (mean=1,600) but relatively more mutations (mean=37) in familial HBs. However, we did not observe this inverse relationship in some of the individual patients. For example, we identified a large number of CNVs in patient 13 who had sporadic HB (n=13,310), but he had an average number of SNVs (n=14). Another sporadic HB patient (patient 16) had the least number of CNVs (n=707), but an average number of SNVs (n=13). These results highlight the genetic heterogeneity underlying the tumorigenesis of HB.

We identified several mutations/CNVs in genes that are involved in angiogenesis, such as vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and VEGFC. VEGFA, located at 6p12, is a member of the cysteine knot family of growth factors, and it is produced by most cells in the body[Ferrara 2004]. It is well known for its essential role in the growth of blood vessels and for its involvement in angiogenesis in brain tumors [Jain and others 2007]. A recent study also reported that VEGFA was over-expressed in HB tissues in comparison to normal surrounding tissues from the same patients [Kruizinga and others 2016]. We also observed many mutations/CNVs in the intergrin (ITG) gene family, such as ITGA8, ITGA1, ITGB5, and ITGB8. ITGB8, located on the cytogenetic band 7p21.1 of the human chromosome 1, can prevent neuronal apoptosis that is induced by deprivation of oxygen-glucose, and inhibition of ITGB8 leads to down regulation of VEGF [Zhang and others 2012]. ITGB8 is also involved in the management of neurovascular physiology. Its removal in perivascular cells leads to the inability to regulate the active phases of blood vessel growth, leading to problems with neurovascular homeostasis [Salajegheh 2016]. Suppression of ITGB8 can promote tumor growth and angiogenesis [Fang and others 2011]. Many of the other genes that we identified in the ITG family also play important functions regarding angiogenesis or the pathogenesis of various types of tumors [Salajegheh 2016]. These findings suggest potential pharmacological targets for the prevention and/or treatment of HBs.

Our study has some limitations. First, the sample size is rather limited. This prevented us from differentiating driver mutations from passenger mutations [Tokheim and others 2016]. More studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate our findings. Second, the patients in this study were from a single hospital in China, and it is uncertain as to whether our findings can be generalized to patients of different races/ethnicities. Third, although we identified many genetic variations that might contribute to the tumorigenesis of HBs, in this exploratory analysis, we did not examine the underlying mechanisms. Future studies are also needed to investigate how multiple genetic variants interact with each other in the development of HBs. Finally, in this study, we used VarScan to detect the SNVs. Previous research indicated that this caller had a sensitivity >70% in whole-exome sequencing [Kroigard and others 2016], and had medium specificities [Cai and others 2016]. It exhibited advantages in comparison with other callers in the detection of somatic SNVs with high frequencies. However, because we did not perform analytical validation of the identified somatic variants, we cannot rule out the possibility of false positive findings. Various factors, such as sample preparation, exome enrichment laboratory procedure and random/systematic sequencing and alignment errors, can lead to false positive findings. We are conducting an ongoing study which aims at including more patients with HBs to validate the findings from this study.

In summary, we performed WES in six patients with sporadic HBs and five patients with familial HBs. We found many SNVs and CNVs, many of which were reported to play essential roles in angiogenesis or the pathogenesis of cancers. Our findings highlight the complexity of the pathogenesis of HBs, even in patients with familial HBs. Future studies exploring the underlying mechanisms will further illustrate how multiple genetic variations lead to the initiation and progression of HB, and they can help pinpoint therapeutic targets for the treatment of HBs.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1. Somatic mutations in the 6 patients with sporadic HBs.

The left column represents genes harboring somatic mutations. Each other column represents an individual patient with sporadic HBs.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Somatic mutations in the 5 patients with familial HBs.

The left column represents genes harboring somatic mutations. Each other column represents an individual patient with familial HBs.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 3. An identified somatic mutation network for sporadic HBs.

Network was constructed using genes harboring significant somatic mutations in patients with sporadic HBs.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 4. An identified somatic mutation network for familial HBs.

Network was constructed using genes harboring significant somatic mutations in patients with familial HBs.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 5. Distribution of copy number variations (CNV) across chromosomes in patients with sporadic HBs.

Each row represents an individual patient, and the columns represent different chromosomes.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 6. Distribution of copy number variations (CNV) across chromosomes in patients with familial HBs.

Each row represents an individual patient, and the columns represent different chromosomes.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement

This work was supported by grants from the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (15411951800, 15410723200) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81172392).

Dr. Jingyun Yang’s research was supported by NIH/NIA R01AG036042 and the Illinois Department of Public Health.

List of abbreviations

- ANNOVAR

Annotate Variation

- CNS

central nervous system

- CNV

copy number variation

- HB

hemangioblastoma

- SNV

single nucleotide variant

- WES

Whole exome sequencing

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Aqeilan RI, Croce CM. WWOX in biological control and tumorigenesis. Journal of cellular physiology. 2007;212(2):307–310. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aqeilan RI, Pekarsky Y, Herrero JJ, Palamarchuk A, Letofsky J, Druck T, Trapasso F, Han SY, Melino G, Huebner K, Croce CM. Functional association between Wwox tumor suppressor protein and p73, a p53 homolog. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(13):4401–4406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400805101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitner MM, Winship I, Drummond KJ. Neurosurgical considerations in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18(2):171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Yuan W, Zhang Z, He L, Chou KC. In-depth comparison of somatic point mutation callers based on different tumor next-generation sequencing depth data. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36540. doi: 10.1038/srep36540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catapano D, Muscarella LA, Guarnieri V, Zelante L, D’Angelo VA, D’Agruma L. Hemangioblastomas of central nervous system: molecular genetic analysis and clinical management. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(6):1215–1221. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000159646.15026.d6. discussion 1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang DY, Getz G, Jaffe DB, O’Kelly MJ, Zhao X, Carter SL, Russ C, Nusbaum C, Meyerson M, Lander ES. High-resolution mapping of copy-number alterations with massively parallel sequencing. Nat Methods. 2009;6(1):99–103. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriello G, Miller ML, Aksoy BA, Senbabaoglu Y, Schultz N, Sander C. Emerging landscape of oncogenic signatures across human cancers. Nature genetics. 2013;45(10):1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/ng.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli ET, Goldstein DB. Uncovering the roles of rare variants in common disease through whole-genome sequencing. Nature reviews Genetics. 2010;11(6):415–425. doi: 10.1038/nrg2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway JE, Chou D, Clatterbuck RE, Brem H, Long DM, Rigamonti D. Hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome and sporadic disease. Neurosurgery. 2001;48(1):55–62. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200101000-00009. discussion 62–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulski C, Krzystolik K, Murgia A, Gorski B, Debniak T, Jakubowska A, Martella M, Kurzawski G, Prost M, Kojder I, Limon J, Nowacki P, Sagan L, Bialas B, Kaluza J, Zdunek M, Omulecka A, Jaskolski D, Kostyk E, Koraszewska-Matuszewska B, Haus O, Janiszewska H, Pecold K, Starzycka M, Slomski R, Cwirko M, Sikorski A, Gliniewicz B, Cyrylowski L, Fiszer-Maliszewska L, Gronwald J, Toloczko-Grabarek A, Zajaczek S, Lubinski J. Germline mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene in patients from Poland: disease presentation in patients with deletions of the entire VHL gene. J Med Genet. 2002;39(7):E38. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.7.e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diskin SJ, Hou C, Glessner JT, Attiyeh EF, Laudenslager M, Bosse K, Cole K, Mosse YP, Wood A, Lynch JE, Pecor K, Diamond M, Winter C, Wang K, Kim C, Geiger EA, McGrady PW, Blakemore AI, London WB, Shaikh TH, Bradfield J, Grant SF, Li H, Devoto M, Rappaport ER, Hakonarson H, Maris JM. Copy number variation at 1q21.1 associated with neuroblastoma. Nature. 2009;459(7249):987–991. doi: 10.1038/nature08035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulaimi E, Ibanez de Caceres I, Uzzo RG, Al-Saleem T, Greenberg RE, Polascik TJ, Babb JS, Grizzle WE, Cairns P. Promoter hypermethylation profile of kidney cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(12 Pt 1):3972–3979. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Deng Z, Shatseva T, Yang J, Peng C, Du WW, Yee AJ, Ang LC, He C, Shan SW, Yang BB. MicroRNA miR-93 promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis by targeting integrin-beta8. Oncogene. 2011;30(7):806–821. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocrine reviews. 2004;25(4):581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke G, Bausch B, Hoffmann MM, Cybulla M, Wilhelm C, Kohlhase J, Scherer G, Neumann HP. Alu-Alu recombination underlies the vast majority of large VHL germline deletions: Molecular characterization and genotype-phenotype correlations in VHL patients. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(5):776–786. doi: 10.1002/humu.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukino K, Teramoto A, Adachi K, Takahashi H, Emi M. A family with hydrocephalus as a complication of cerebellar hemangioblastoma: identification of Pro157Leu mutation in the VHL gene. J Hum Genet. 2000;45(1):47–51. doi: 10.1007/s100380050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudio E, Palamarchuk A, Palumbo T, Trapasso F, Pekarsky Y, Croce CM, Aqeilan RI. Physical association with WWOX suppresses c-Jun transcriptional activity. Cancer research. 2006;66(24):11585–11589. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hes F, Zewald R, Peeters T, Sijmons R, Links T, Verheij J, Matthijs G, Leguis E, Mortier G, van der Torren K, Rosman M, Lips C, Pearson P, van der Luijt R. Genotype-phenotype correlations in families with deletions in the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene. Hum Genet. 2000;106(4):425–431. doi: 10.1007/s004390000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein MR. Central nervous system capillary haemangioblastoma: the pathologist’s viewpoint. Int J Exp Pathol. 2007;88(5):311–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RK, di Tomaso E, Duda DG, Loeffler JS, Sorensen AG, Batchelor TT. Angiogenesis in brain tumours. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(8):610–622. doi: 10.1038/nrn2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt DC, Chen K, Wylie T, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Mardis ER, Weinstock GM, Wilson RK, Ding L. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(17):2283–2285. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroigard AB, Thomassen M, Laenkholm AV, Kruse TA, Larsen MJ. Evaluation of Nine Somatic Variant Callers for Detection of Somatic Mutations in Exome and Targeted Deep Sequencing Data. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruizinga RC, van Marion DM, den Dunnen WF, de Groot JC, Hoving EW, Oosting SF, Timmer-Bosscha H, Derks RP, Cornelissen C, van der Luijt RB, Links TP, de Vries EG, Walenkamp AM. Difference in CXCR4 expression between sporadic and VHL-related hemangioblastoma. Familial cancer. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9879-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam HY, Clark MJ, Chen R, Natsoulis G, O’Huallachain M, Dewey FE, Habegger L, Ashley EA, Gerstein MB, Butte AJ, Ji HP, Snyder M. Performance comparison of whole-genome sequencing platforms. Nature biotechnology. 2012;30(1):78–82. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska U, Zelazowski M, Seta K, Byczewska M, Pluciennik E, Bednarek AK. WWOX, the tumour suppressor gene affected in multiple cancers. Journal of physiology and pharmacology : an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society. 2009;60(Suppl 1):47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, Chew EY, Libutti SK, Linehan WM, Oldfield EH. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361(9374):2059–2067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Zhang M, Chen L, Tang Q, Tang X, Mao Y, Zhou L. Hemangioblastomas might derive from neoplastic transformation of neural stem cells/progenitors in the specific niche. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(1):102–109. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher ER, Webster AR, Richards FM, Green JS, Crossey PA, Payne SJ, Moore AT. Phenotypic expression in von Hippel-Lindau disease: correlations with germline VHL gene mutations. J Med Genet. 1996;33(4):328–332. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.4.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, Benjamin C, Harris R, Moore AT, Ferguson-Smith MA. Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Q J Med. 1990;77(283):1151–1163. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/77.2.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maranchie JK, Afonso A, Albert PS, Kalyandrug S, Phillips JL, Zhou S, Peterson J, Ghadimi BM, Hurley K, Riss J, Vasselli JR, Ried T, Zbar B, Choyke P, Walther MM, Klausner RD, Linehan WM. Solid renal tumor severity in von Hippel Lindau disease is related to germline deletion length and location. Hum Mutat. 2004;23(1):40–46. doi: 10.1002/humu.10302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis ER. Next-generation DNA sequencing methods. Annual review of genomics and human genetics. 2008;9:387–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann HP, Eggert HR, Weigel K, Friedburg H, Wiestler OD, Schollmeyer P. Hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. A 10-year study with special reference to von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. J Neurosurg. 1989;70(1):24–30. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.1.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom-O’Brien M, van der Luijt RB, van Rooijen E, van den Ouweland AM, Majoor-Krakauer DF, Lolkema MP, van Brussel A, Voest EE, Giles RH. Genetic analysis of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(5):521–537. doi: 10.1002/humu.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porreca GJ. Genome sequencing on nanoballs. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28(1):43–44. doi: 10.1038/nbt0110-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard S, David P, Marsot-Dupuch K, Giraud S, Beroud C, Resche F. Central nervous system hemangioblastomas, endolymphatic sac tumors, and von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23(1):1–22. doi: 10.1007/s101430050024. discussion 23–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salah Z, Aqeilan R, Huebner K. WWOX gene and gene product: tumor suppression through specific protein interactions. Future Oncol. 2010;6(2):249–259. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salajegheh A. Angiogenesis in Health, Disease and Malignancy. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata BM, Stockwell CA, Castellano-Sanchez AA, Setzer S, Schmotzer CL, Robinson H. Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: an update on the clinico-pathologic and genetic aspects. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15(3):165–171. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31816f852e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims KB. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: gene to bedside. Curr Opin Neurol. 2001;14(6):695–703. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokheim CJ, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Karchin R. Evaluating the evaluation of cancer driver genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(50):14330–14335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616440113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanebo JE, Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Oldfield EH. The natural history of hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(1):82–94. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.1.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang W, Li R, Li Y, Tian G, Goodman L, Fan W, Zhang J, Li J, Zhang J, Guo Y, Feng B, Li H, Lu Y, Fang X, Liang H, Du Z, Li D, Zhao Y, Hu Y, Yang Z, Zheng H, Hellmann I, Inouye M, Pool J, Yi X, Zhao J, Duan J, Zhou Y, Qin J, Ma L, Li G, Yang Z, Zhang G, Yang B, Yu C, Liang F, Li W, Li S, Li D, Ni P, Ruan J, Li Q, Zhu H, Liu D, Lu Z, Li N, Guo G, Zhang J, Ye J, Fang L, Hao Q, Chen Q, Liang Y, Su Y, San A, Ping C, Yang S, Chen F, Li L, Zhou K, Zheng H, Ren Y, Yang L, Gao Y, Yang G, Li Z, Feng X, Kristiansen K, Wong GK, Nielsen R, Durbin R, Bolund L, Zhang X, Li S, Yang H, Wang J. The diploid genome sequence of an Asian individual. Nature. 2008;456(7218):60–65. doi: 10.1038/nature07484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DA, Srinivasan M, Egholm M, Shen Y, Chen L, McGuire A, He W, Chen YJ, Makhijani V, Roth GT, Gomes X, Tartaro K, Niazi F, Turcotte CL, Irzyk GP, Lupski JR, Chinault C, Song XZ, Liu Y, Yuan Y, Nazareth L, Qin X, Muzny DM, Margulies M, Weinstock GM, Gibbs RA, Rothberg JM. The complete genome of an individual by massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nature. 2008;452(7189):872–876. doi: 10.1038/nature06884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Liu B, Huang B, Deng J, Li H, Yu B, Qiu F, Cheng M, Wang H, Yang R, Yang X, Zhou Y, Lu J. A functional copy number variation in the WWOX gene is associated with lung cancer risk in Chinese. Human molecular genetics. 2013;22(9):1886–1894. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Fan J, Ding X, Li C, Wang J, Xiang Y, Wang QS. Association study of a functional copy number variation in the WWOX gene with risk of gliomas among Chinese people. International journal of cancer. 2014;135(7):1687–1691. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Qu Y, Tang B, Zhao F, Xiong T, Ferriero D, Mu D. Integrin beta8 signaling in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Neurotoxicity research. 2012;22(4):280–291. doi: 10.1007/s12640-012-9312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Somatic mutations in the 6 patients with sporadic HBs.

The left column represents genes harboring somatic mutations. Each other column represents an individual patient with sporadic HBs.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Somatic mutations in the 5 patients with familial HBs.

The left column represents genes harboring somatic mutations. Each other column represents an individual patient with familial HBs.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 3. An identified somatic mutation network for sporadic HBs.

Network was constructed using genes harboring significant somatic mutations in patients with sporadic HBs.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 4. An identified somatic mutation network for familial HBs.

Network was constructed using genes harboring significant somatic mutations in patients with familial HBs.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 5. Distribution of copy number variations (CNV) across chromosomes in patients with sporadic HBs.

Each row represents an individual patient, and the columns represent different chromosomes.

HB, hemangioblastoma.

Supplementary Fig. 6. Distribution of copy number variations (CNV) across chromosomes in patients with familial HBs.

Each row represents an individual patient, and the columns represent different chromosomes.

HB, hemangioblastoma.