Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the associations of nighttime sleep duration and midday napping with risk of depressive symptoms incidence and persistence among middle-aged and older Chinese. Data from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, CHARLS (2011–2013), were analyzed. Depressive symptoms were identified by the 10-item version of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CESD-10). Multivariate binary logistic regression models were fitted. There were 7156 individuals with CESD-10 scores < 10 and 3896 individuals with CESD-10 scores ≥ 10 at baseline included in this study. After controlling for potential covariates, nighttime sleep duration <6 hours was associated with high risk of incident depressive symptoms (OR = 1.450, 95%CI: 1.193, 1.764 for middle aged population, and OR = 2.084, 95%CI:1.479, 2.936 for elderly) and persistent depressive symptoms (OR = 1.404, 95%CI: 1.161, 1.699 for middle aged population, and OR = 1.365, 95%CI: 0.979, 1.904 for elderly). For depressed individuals, longer midday napping (≥60 minutes) was associated with lower persistent depressive symptoms (OR = 0.842, 95%CI: 0.717, 0.989). Our study concluded that short nighttime sleep duration was an independent risk factor of depressive symptoms incidence and persistence. Depressed individuals with long midday napping were more likely to achieve reversion than those who have no siesta habit.

Introduction

Depression is a common psychiatric disorder, affecting an estimated 350 million people worldwide1. In China, about 40% of elderly aged ≥60 years had reported depressive symptoms2. Depression is associated with decreased physical, cognitive and social function. Moreover, most persons with depression remain untreated, and experience fluctuating symptom levels over time3, leading to increased risk of morbidity and suicide4. It is predicted that depression would be the second leading cause of disability by 20205. The prevention and treatment of depression have become a hot topic in the field of public health.

Sleep, as a very important health-related factor, has been found to play a role in the development of many diseases6–8 and even all-cause mortality9. As for the role of night sleep duration in incidence of depression, a recent meta-analysis10 of prospective studies concluded that excessively short or long sleep duration was associated with incidence of depression in adults. However, among the 7 studies included in this meta-analysis, 6 studies were carried out in the United States, the seventh, conducted in Japan, had no statistically significant results11. Actually, evidences for the longitudinal association of sleep duration with depression among Asians were very limited. In addition, as far as we know, only three previous studies focused on the effect of sleep duration on persistence of depression, and they have drawn conflicting conclusions: two of them indicated that only short sleep was associated with the persistence of depression12,13, while the rest one study reported a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and the persistent depression14.

Midday napping is prevalent in China, especially among older adults and is widely accepted as a healthy lifestyle from a cultural perspective15. Although accumulative evidence from western populations showed that daytime napping might be a marker of underlying health problems16, some experts think that, unlike the nap in the morning or evening, appropriate midday napping, might be restorative and could relieve stress17,18. To date, the effect of midday napping on depression has not been explored in-depth.

In this 2-year long longitudinal study, we aimed to investigate whether nighttime sleep duration and midday napping were independently associated with incidence and persistence of depressive symptoms among Chinese aged ≥45 years.

Methods

Participants

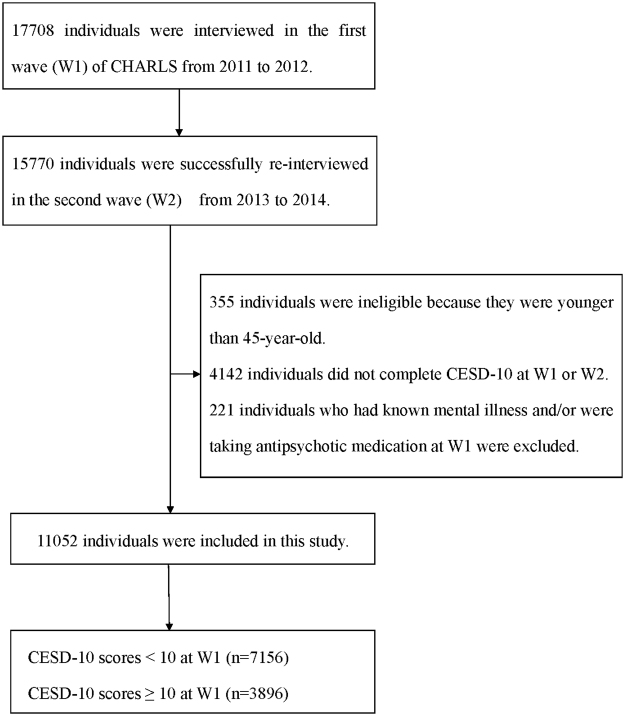

The data analyzed in this study were derived from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationally representative survey on community-based population aged 45 years or older. The CHARLS was conducted by the National School of Development at Peking University. Details for the procedures of its multistage stratified sampling were described elsewhere19. Briefly, the survey included two waves covering 150 county-level units distributed in 28 provinces of China except Tibet. Data for participants’ demographic characteristics, health-related behaviors and lifestyles, health condition, as well as anthropometric and laboratory measurements were collected by well-trained clinicians in a face-to-face, computer-aided personal interview (CAPI) manner. A total of 17,708 individuals agreed to participate in the baseline (wave 1, W1) survey from 2011 to 2012, resulting in a respondent rate of 80%. The second wave (wave 2, W2) survey successfully re-interviewed 15,770 people among them from 2013 to 2014. In the current analyses, 355 individuals who were younger than 45-year-old, 4142 individuals who did not complete depression measurements at W1 or W2, as well as 221 individuals who had known mental illness and/or were taking antipsychotic medication at W1 were excluded. Thus, there were 11,052 individuals included in the final sample (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Participants’ flow in the study.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were identified by using the 10-item version of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CESD-10), which had high validity and reliability in Chinese population20. The time frame for the CESD-10 questions refers to the week prior to the interview. There were 4 Likert scale answers varying from “rarely or none of the time (<1 day)” to “most or all of the time (5–7 days)” for each item. For the 8 negatively worded items, the answers were coded as 0, 1, 2, 3 scores from “<1 day” to “5–7 days”, while for the 2 positively worded items, the answers were reverse- coded. The sum total is 0–30 and that a total score of ≥10 was defined as clinically significant depressive symptoms.

Among individuals with total CESD-10 score <10 at W1, those who were subsequently diagnosed as having depression by a medical doctor or who endorsed the CESD-10 scores ≥10 at W2 were grouped as incidence of depressive symptoms, and the rest were grouped as non- depressive symptoms. Among individuals with CESD-10 scores ≥10 at W1, those who were taking anti-depressant medicine or CESD-10 scores ≥10 at W2 were grouped as persistent depressive symptoms, and the rest were grouped as reversion of depressive symptoms.

Sleep duration

Self-reported sleep duration was ascertained with the following question: “During the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night (average hours for one night)?” and “During the past month, how long did you take a nap after lunch?” Considering the different sleep habits between middle aged and elderly population, a sleep duration of 7–9 hours21 per night for middle aged population (45–65 years old) and 7–8 hours11 for elderly (≥65 years old) were chosen as the referent categories. Nighttime sleep duration was categorized as <6 hours, 6–7 hours, 7–9 hours and >9 hours for middle aged population, and <6 hours, 6–7 hours, 7–8 hours and >8 hours for elderly. Midday napping was classed as none, <60 minutes and ≥60 minutes. Lack of midday napping (none) was chosen as the ref.22.

Covariates

Our covariates included age, gender, educational level, marital status, body mass index (BMI), cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking and social activity. Educational level was categorized as illiterate (those who had no formal education), literate (those who did not finished primary school but were capable of reading and/or writing), primary education (those who had finished 6 years of education), middle school education and above (those who had finished more than 6 years of education). Marital status was allocated into two categories: single and married, which “single” included “separated”, “divorced”, “widowed”, and “never married”. BMI was derived by taking body weight (in kilogram) divided by height (in meter) squared. Cigarette smoking was classed as ‘never’(those who had never chewed tobacco, smoked a pipe, smoked self-rolled cigarettes, or smoked cigarettes/cigars), ‘former’ (those who had ever smoked, but has totally quit) or ‘current’ (those who still smoked). And alcohol drinking was classed as ‘never’ (those who had never drank alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, or liquor or had never drank more than once a month), ‘former’ (those who had ever drank more than once a month, but has quit), ‘current’ (those who still drank more than once a month but less than twice a day) or ‘frequent’ (those who drank more than twice a day). Social activity was ascertained with frequencies of 10 items of social activities (e.g. interacting with friends, playing Ma-jong, chess, cards, going to community club, etc.). The answer with “never”, “not regularly”, “almost every week”, or “almost daily”, was coded as 0, 1, 2 or 3 scores. The total social activity score was constructed by summing the responses to each item, with a possible range from 0 to 30.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for baseline characteristics of the participants were presented according to depressive status. The longitudinal associations of participants’ characteristics with depressive symptoms were first tested by using univariate binary logistic regression models. To estimate the independent effect of baseline sleep duration on incidence or persistence of depressive symptoms, three kinds of binary logistic regression models were fitted: model 1, univariate; model 2: adjusted for age and gender; model 3, adjusted for variables in model 2 plus marital status, education, drinking status, smoking status, BMI, social activity. All analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Statistical significance was defined by setting the type I error rate at α = 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

A total of 7156 participants with the CESD-10 scores <10 were classified as free of depressive symptoms at baseline. During the follow-up period, the cumulative incidence of depressive symptoms was 18.6%. Female gender (p < 0.001), lower educational level (p < 0.001), never drinking (p = 0.022), never smoking (p = 0.007), and less social activity (p < 0.001) were associated with higher incidence of depressive symptoms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 7156 participants with CES-D 10 score <10 at W1.

| Independent Variable | Overall n = 7156 | Incidence of Depression at W2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no (n = 5823) | yes (n = 1333) | |||

| Age, year (mean ± SD), n = 7156 | 58.12 ± 8.94 | 58.14 ± 8.95 | 58.06 ± 8.91 | 0.867 |

| Gender (%), n = 7149 | ||||

| Male (ref.) | 3843 | 3240(84.3) | 603(15.7) | — |

| Female | 3306 | 2578(78.0) | 728(22.0) | <0.001 |

| Education (%),n = 7155 | ||||

| Illiterate | 1473 | 1128(76.6) | 345(23.4) | <0.001 |

| Literate | 1122 | 880(78.4) | 242(21.6) | <0.001 |

| Primary education | 1657 | 1344(81.1) | 313(18.9) | <0.001 |

| Above junior school (ref.) | 2903 | 2471(85.1) | 432(14.9) | — |

| Marital status (%), n = 7156 | ||||

| Married (ref.) | 6556 | 5351(81.6) | 1205(18.4) | — |

| Single | 600 | 472(78.7) | 128(21.3) | 0.076 |

| Drinking status (%), n = 6748 | ||||

| Never | 4724 | 3764(79.7) | 960(20.3) | 0.025 |

| Former | 395 | 327(82.8) | 68(17.2) | 0.506 |

| Current | 1266 | 1079(85.2) | 187(14.8) | 0.757 |

| Frequent (ref.) | 363 | 307(84.6) | 56(15.4) | — |

| Smoking status (%), n = 7154 | ||||

| Never | 4151 | 3320(80.0) | 831(20.0) | 0.007 |

| Former | 659 | 562(85.3) | 97(14.7) | 0.120 |

| Current (ref.) | 2344 | 1939(82.7) | 405(17.3) | — |

| Social activity, score (mean ± SD), n = 7144 | 1.63 ± 2.18 | 1.69 ± 2.20 | 1.40 ± 2.07 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD), n = 6141 | 23.85 ± 3.92 | 23.88 ± 3.84 | 23.70 ± 4.27 | 0.192 |

CESD-10, the 10-item version of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale; W1, wave 1; W2, wave 2; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index.

There were 3896 participants with the CESD-10 scores ≥10 at baseline. Of these, 46.1% had reversion of depressive symptoms while the rest had persistent. As shown in Table 2, female gender (p < 0.001), lower educational level (p < 0.001), single marital status (p = 0.049), never drinking (p = 0.003) and never smoking (p < 0.001) were associated with higher risk of persistent depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 3896 participants with CES-D 10 score μ ≥ 10 at W1.

| Demographics | Overall n = 3896 | Persistent Depression at W2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no (n = 1798) | yes (n = 2098) | |||

| Age, year (mean ± SD), n = 3896 | 59.37 ± 8.98 | 59.57 ± 9.17 | 59.20 ± 8.81 | 0.172 |

| Gender (%), n = 3895 | ||||

| Male (ref.) | 1537 | 810(52.7) | 727(47.3) | — |

| Female | 2358 | 987(41.9) | 1371(58.1) | <0.001 |

| Education (%) | ||||

| Illiterate | 1233 | 521(42.3) | 712(57.7) | <0.001 |

| Literate | 836 | 336(40.2) | 500(59.8) | <0.001 |

| Primary education | 908 | 457(50.3) | 451(49.7) | 0.318 |

| Above junior school (ref.) | 919 | 484(52.7) | 435(47.3) | — |

| Marital status (%), n = 3896 | ||||

| Married (ref.) | 3318 | 1553(46.8) | 1765(53.2) | — |

| Single | 578 | 245(42.4) | 333(57.6) | 0.049 |

| Drinking status (%), n = 3728 | ||||

| Never | 2798 | 1221(43.6) | 1577(56.4) | 0.003 |

| Former | 277 | 137(49.5) | 140(50.5) | 0.183 |

| Current | 511 | 272(53.2) | 239(46.8) | 0.511 |

| Frequent (ref.) | 142 | 80(56.3) | 62(43.7) | — |

| Smoking status (%), n = 3896 | ||||

| Never | 2513 | 1090(43.4) | 1423(56.6) | <0.001 |

| Past | 303 | 156(51.5) | 147(48.5) | 0.908 |

| Current (ref.) | 1080 | 552(51.1) | 528(48.9) | — |

| Social activity, score (mean ± SD), n = 3891 | 1.25 ± 1.85 | 1.27 ± 1.87 | 1.24 ± 1.83 | 0.774 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD), n = 3364 | 23.19 ± 4.00 | 23.29 ± 3.95 | 23.10 ± 4.03 | 0.140 |

CESD-10, the 10-item version of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale; W1, wave 1; W2, wave 2; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index.

Table 3 lists the results of logistic regression analyses for individuals without depressive symptoms at baseline. After adjustment for potential confounders, shorter nighttime sleep duration was independently associated with increased incidence of depressive symptoms in each model. Compared with reference sleep duration, the fully adjusted ORs (95% CI) of nighttime sleep duration <6 h were 1.450 (1.193, 1.764) for middle aged population and 2.084 (1.479, 2.936) for elderly, respectively. No models showed significant effect of longer nighttime sleep on incidence of depressive symptoms. Model 1 suggested that compared with lack of siesta, midday napping ≥60 minutes was associated with lower risk of depressive symptoms incidence (OR = 0.872, 95% CI: 0.762, 0.998). However, after adjustment for more covariates, the association had no statistical significance.

Table 3.

Longitudinal association of nighttime sleep duration/midday napping with incident depressive symptoms in 7156 participants with CES-D 10 score <10 at W1.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR 95%CI | OR 95%CI | OR 95%CI | |

| Nighttime Sleep Duration, hour | |||

| age 45–65 (n = 5505) | |||

| <6 | 1.641(1.380,1.951) * | 1.634(1.373,1.944) * | 1.450(1.193,1.764) * |

| 6–7 | 1.160(0.977,1.377) | 1.172(0.986,1.394) | 1.205(0.995,1.459) |

| 7–9 (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >9 | 1.294(0.910,1.840) | 1.275(0.895,1.816) | 1.015(0.676,1.52) |

| age ≥65 (n = 1651) | |||

| <6 | 1.903(1.398,2.592) * | 1.922(1.411,2.619)* | 2.084(1.479,2.936) * |

| 6–7 | 1.571(1.134,2.176) * | 1.586(1.144,2.199)* | 1.602(1.115,2.301) * |

| 7–8 (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >8 | 1.497(0.958,2.340) | 1.512(0.967,2.364) | 1.104(0.639,1.905) |

| Midday Napping, minute | |||

| 0 (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| <60 | 0.925(0.785,1.091) | 0.960(0.813,1.133) | 0.987(0.821,1.187) |

| ≥60 | 0.872(0.762,0.998) * | 0.888(0.776,1.018) | 0.925(0.795,1.077) |

Model1 unadjusted.

Model 2 adjusted for age, gender.

Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 + marital status, education, drinking status, smoking status, BMI, social activity.

Bold for p ⩽ 0.05.

*for p ⩽ 0.05.

CESD-10, the 10-item version of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale; W1, wave 1; OR, odds ratio; BMI, body mass index.

The longitudinal associations between sleep duration and persistent depressive symptoms in logistic regression models are summarized in Table 4. The association between nighttime sleep duration <6 h and persistent depressive symptoms were significant (OR = 1.404, 95%CI: 1.161, 1.699) for middle aged population and suggestive significant (OR = 1.365, 95%CI: 0.979, 1.904) for elderly. Long sleep showed no significant effect on persistent depressive symptoms. Additionally, individuals who reported ≥60 minutes of midday napping were more likely to achieve reversion of depressive symptoms than those who have no midday napping habit (OR = 0.842, 95%CI: 0.717,0.989).

Table 4.

Longitudinal association of nighttime sleep duration/midday napping with persistent depressive symptoms in 3896 participants with CES-D 10 score ≥10 at W1.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR 95%CI | OR 95%CI | OR 95%CI | |

| Nighttime Sleep Duration, h | |||

| age 45–65 (n = 2842) | |||

| <6 | 1.450(1.222,1.721) * | 1.432(1.206,1.702) * | 1.404(1.161,1.699)* |

| 6–7 | 1.089(0.885,1.340) | 1.091(0.886,1.345) | 1.056(0.839,1.330) |

| 7–9 (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >9 | 0.822(0.547,1.236) | 0.808(0.536,1.219) | 0.649(0.404,1.042) |

| age ≥65 (n = 1054) | |||

| <6 | 1.375(1.018,1.856) * | 1.389(1.025,1.881) * | 1.365(0.979,1.904) |

| 6–7 | 0.927(0.631,1.362) | 0.983(0.665,1.453) | 0.875(0.570,1.344) |

| 7–8 (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >8 | 0.747(0.448,1.243) | 0.765(0.458,1.279) | 0.733(0.405,1.325) |

| Midday Napping, min | |||

| 0 (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| <60 | 0.983(0.821,1.178) | 1.012(0.843,1.214) | 0.975(0.797,1.193) |

| ≥60 | 0.840(0.728,0.970) * | 0.854(0.739,0.987) * | 0.842(0.717,0.989) * |

Model1 unadjusted.

Model 2 adjusted for age, gender.

Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 + marital status, education, drinking status, smoking status, BMI, social activity.

Bold for p ⩽ 0.05.

* for p ⩽ 0.05.

CESD-10, the 10-item version of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale; W1, wave 1; OR, odds ratio; BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

The results from this large prospective study, including 11,052 participants, indicate that compared with reference sleep duration, shorter baseline self-reported nighttime sleep duration was associated with higher incidence and persistence of depressive symptoms 2 years later, among middle-aged and older Chinese. Besides, for depressed individuals at baseline, longer midday napping was associated with a lower risk of persistent depressive symptoms.

Our findings about adverse effect of short nighttime sleep on incidence of depressive symptoms were consistent with the previous literature23. Similar to 5 analogous studies11,23–25, we didn’t find any significant relationship between long sleep duration and incidence of depressive symptoms either. However, after pooling the 5 studies involving 23,663 participants, the meta-analysis10 found that long sleep duration was significantly associated with increased risk of depression. The power of a single study was limited possibly because of the small sample size for long sleep duration in community-based population. For example, in our sample, only 284 participants reported nighttime sleep >9 h. Yamada22,26 reported the J-curve relation between daytime nap duration and incidence of type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome or cardiovascular disease, but linear relationship between daytime nap duration and all-cause mortality. However, there is no previous study specialize on midday napping and depression. We first reported no effect of midday napping on incident depressive symptom.

As far as we know, there have been few studies that have investigated the longitudinal association of nighttime sleep duration with persistence of depression. Different from our conclusion, a 2-year cohort study reported that both short and long sleep duration were important predictors of persistent depressive disorder14. Nevertheless, the other two prospective studies found short sleep duration was associated with persistent depression, while long sleep showed no association with depression12,13, which were similar to our observation. It is interesting that our results suggested the benefits of long midday napping on reversion of depressive symptoms. However, there is no previous study on the same topic to be reference.

The mechanisms underlying the association between sleep and depression are still not fully understood. Several potential mechanisms exist by which reduced nighttime sleep duration may increase the risk of incident and persistent depressive symptoms. Firstly, physical tiredness and/or psychological fatigue at daytime caused by poor nighttime sleep27 may disrupt circadian rhythms and/or cause hormonal alterations, resulting in incidence of depression28,29. Secondly, growing evidences suggested that short/long sleep duration was associated with increase of inflammation level, which has been observed in depressed patients compared to non-depressed population. Low-grade chronic inflammation maybe a key biological pathway to link the sleep and depressive symptoms30,31. Thirdly, some researchers suggested that short nighttime sleep could be a part of the prodrome of a mental disorder32 or a residual symptom of a prior disorder33.

A major strength of this study was its large sample size from a prospective cohort, allowing a much greater possibility of reasonable conclusions. As is well-known, the relationship between sleep and depression is bidirectional and complicated. On the one hand, extreme sleep duration is usually considered as a symptom of depression34,35. On the other hand, instead of being a symptom, poor sleep may be a risk factor of depression36. Longitudinal design can give more information about the direction of causality. Based on this kind of study design, we observed not only the incidence of depressive symptoms in a normal population but also the persistent status in participants with depressive symptoms.

There were some limitations to consider. Firstly, Sleep duration was assessed at W1 over the previous 1 month. Consideration was not given to possible change in sleep duration between W1 and W2. Secondly, the cognitive status of the participants was not determined and the response of the cognitively-impaired patients may not be reliable. Thirdly, there were 27.3% of eligible participants excluded due to incomplete CESD-10 data. Their inclusion, otherwise, could have modified the association between sleep duration and depressive symptoms as found in the present analysis. Fourthly, the lack of comprehensive information on sleep complaints, snore, and other confounders limited our further investigation into the relationship between sleep duration and depressive symptoms. Fifthly, the items related to “cigarette smoking” in the questionnaire did not set a time frame for “current” and “former” that limited the evidence emerging from the study.

Conclusion

In summary, results from this study indicated that short nighttime sleep duration was an independent risk factor of incident and persistent depressive symptoms. Depressed individuals with long midday napping were more likely to achieve reversion of depression symptoms than those who have no siesta habit.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the Chinese CDC for making the survey and making it available online freely, and all the participants for providing these data. This research project was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371024).

Author Contributions

Y.W. and D.Z. contributed to study design and data interpretation. Y.L., L.Z., T.W. and Y.S. prepared the database. Y.L. and L.Z. performed data analysis. Y.L. and Y.W. wrote the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Yujie Li and Yili Wu contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Perera S, et al. Light therapy for non-seasonal depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open. 2016;2:116–126. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.001610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ni Y, Tein JY, Zhang M, Yang Y, Wu G. Changes in depression among older adults in China: A latent transition analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;209:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beekman AT, et al. The natural history of late-life depression: a 6-year prospective study in the community. Archives of general psychiatry. 2002;59:605–611. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.M249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birney AJ, Gunn R, Russell JK, Ary DV. MoodHacker Mobile Web App With Email for Adults to Self-Manage Mild-to-Moderate Depression: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4:e8. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Y, Zhai L, Zhang D. Sleep duration and obesity among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep medicine. 2014;15:1456–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang L, et al. Sleep Duration and Midday Napping with 5-Year Incidence and Reversion of Metabolic Syndrome in Middle-Aged and Older Chinese. Sleep. 2016;39:1911–1918. doi: 10.5665/sleep.6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang L, et al. Longer Sleep Duration and Midday Napping Are Associated with a Higher Risk of CHD Incidence in Middle-Aged and Older Chinese: the Dongfeng-Tongji Cohort Study. Sleep. 2016;39:645–652. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang D. Nighttime sleep duration, 24-hour sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21480. doi: 10.1038/srep21480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhai L, Zhang H, Zhang D. Sleep Duration and Depression among Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Depression and anxiety. 2015;32:664–670. doi: 10.1002/da.22386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoyama E, et al. Association between depression and insomnia subtypes: a longitudinal study on the elderly in Japan. Sleep. 2010;33:1693–1702. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.12.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glozier N, et al. Short sleep duration in prevalent and persistent psychological distress in young adults: the DRIVE study. Sleep. 2010;33:1139–1145. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pigeon WR, et al. Is insomnia a perpetuating factor for late-life depression in the IMPACT cohort? Sleep. 2008;31:481–488. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Mill JG, Vogelzangs N, van Someren EJ, Hoogendijk WJ, Penninx BW. Sleep duration, but not insomnia, predicts the 2-year course of depressive and anxiety disorders. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2014;75:119–126. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao, Z. et al. The effects of midday nap duration on the risk of hypertension in a middle-aged and older Chinese population: a preliminary evidence from the Tongji-Dongfeng Cohort Study, China. Journal of hypertension32, 1993-1998; discussion 1998, doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000291 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Tanabe N, et al. Daytime napping and mortality, with a special reference to cardiovascular disease: the JACC study. International journal of epidemiology. 2010;39:233–243. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhand R, Sohal H. Good sleep, bad sleep! The role of daytime naps in healthy adults. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2006;12:379–382. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000245704.92311.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milner CE, Cote KA. Benefits of napping in healthy adults: impact of nap length, time of day, age, and experience with napping. Journal of sleep research. 2009;18:272–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61–68. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) American journal of preventive medicine. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang S, et al. Relationship of Sleep Duration with Sociodemographic Characteristics, Lifestyle, Mental Health, and Chronic Diseases in a Large Chinese Adult Population. Journal of clinical sleep medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2017;13:377–384. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada T, Shojima N, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T. J-curve relation between daytime nap duration and type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome: A dose-response meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2016;6:38075. doi: 10.1038/srep38075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gehrman P, et al. Predeployment Sleep Duration and Insomnia Symptoms as Risk Factors for New-Onset Mental Health Disorders Following Military Deployment. Sleep. 2013;36:1009–1018. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paudel M, et al. Sleep Disturbances and Risk of Depression in Older Men. Sleep. 2013;36:1033–1040. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maglione JE, et al. Subjective and objective sleep disturbance and longitudinal risk of depression in a cohort of older women. Sleep. 2014;37:1179–1187. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada T, Hara K, Shojima N, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T. Daytime Napping and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality: A Prospective Study and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Sleep. 2015;38:1945–1953. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen J, Barbera J, Shapiro CM. Distinguishing sleepiness and fatigue: focus on definition and measurement. Sleep medicine reviews. 2006;10:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luik AI, et al. 24-Hour Activity Rhythm and Sleep Disturbances in Depression and Anxiety: A Population-Based Study of Middle-Aged and Older Persons. Depression and anxiety. 2015;32:684–692. doi: 10.1002/da.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Noorden MS, van Fenema EM, van der Wee NJ, Zitman FG, Giltay EJ. Predicting outcome of depression using the depressive symptom profile: the Leiden Routine Outcome Monitoring Study. Depression and anxiety. 2012;29:523–530. doi: 10.1002/da.21958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prather AA, Vogelzangs N, Penninx BW. Sleep duration, insomnia, and markers of systemic inflammation: results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) Journal of psychiatric research. 2015;60:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall MH, et al. Association between sleep duration and mortality is mediated by markers of inflammation and health in older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Sleep. 2015;38:189–195. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Judd LL, et al. A prospective 12-year study of subsyndromal and syndromal depressive symptoms in unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:694–700. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jansson-Frojmark M, Lindblom K. A bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression, and insomnia? A prospective study in the general population. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2008;64:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alcantara C, et al. Sleep Disturbances and Depression in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2016;39:915–925. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendlewicz J. Sleep disturbances: core symptoms of major depressive disorder rather than associated or comorbid disorders. The world journal of biological psychiatry: the official journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. 2009;10:269–275. doi: 10.3109/15622970802503086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiebe ST, Cassoff J, Gruber R. Sleep patterns and the risk for unipolar depression: a review. Nature and science of sleep. 2012;4:63–71. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S23490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]