Abstract

Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide-based photodetectors have demonstrated potential for the next generation of 2-dimensional optoelectronics. However, to date, their sensitivity has not been superior to that of other technologies. Here we report an ultrasensitive two-dimensional photodetector employing an in-plane phototransistor with an out-of-plane vertical MoS2 p–n junction as a sensitizing scheme. The vertical built-in field is introduced for the first time in the transport channel of MoS2 phototransistors by facile chemical surface doping, which separates the photo-excited carriers efficiently and produces a photoconductive gain of >105 electrons per photon, external quantum efficiency greater than 10%, responsivity of 7 × 104 A W−1, and a time response on the order of tens of ms. This taken together with a very low noise power density yields a record sensitivity with specific detectivity of 3.5 × 1014 Jones in the visible and a broadband response up to 1000 nm.

Photodetectors based on 2D transition metal dichalcogenides exhibit ever increasingly competitive performance, yet not superior to that of alternative technologies. Here, the authors devise a MoS2-based phototransistor with an out-of-plane junction, yielding a record detectivity combined with broadband response.

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have emerged as a new optoelectronic platform with the promise to enable optoelectronic functionalities1–11 in the 2D form factor leveraging some unique properties, including their high optical absorption coefficient, favorable direct band gap, high carrier mobility12–14, mechanical flexibility, and potential for large scale growth and processing15, 16. So far, many efforts have been made to develop TMDs 2D-based photodetectors with ultrafast response17 and high responsivity11, with a view to enable their widespread application in remote sensing, camera imaging and optical communications. TMDs-based photodiodes with p–n junctions have been fabricated with transferred van der Waals heterostructures18 or chemical vapor deposition grown hybrids19; however, they are also characterized by low responsivity due to the absence of a photo-gain mechanism or by persistent photoconductivity which is unsuitable for photodetector applications. Until now photodetectors based entirely on 2D-TMDs have not outperformed other established technologies and the reported sensitivities have thus far been below that of alternative hybrid20–23 or standard silicon photodetectors. Reaching compelling sensitivity in 2D-TMDs photodetectors has been impeded by the absence of an intrinsic sensitization mechanism.

Here, we present an all-2D-based photodetector that consists of an out-of-plane (vertical) p–n MoS2 homojunction that acts as the photo-sensitizing layer of the underlying n-type MoS2 transistor. The internal built-in field created from the p–n junction facilitates the photo-excited carrier separation and leads to a significant photo-gating effect. As a result this hybrid detector yields a responsivity of 7 × 104 A W−1 and a record measured detectivity of 3.5 × 1014 Jones with a time response on the order of 10 ms demonstrating the highest sensitivity of 2D-based photodetector to date11, 24–35.

Results

Device scheme

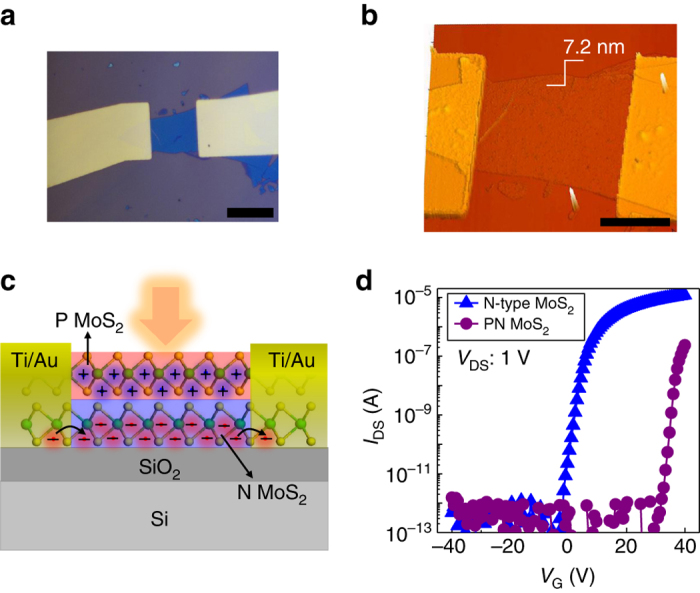

The few layer MoS2 flakes were exfoliated on the SiO2/Si substrate using the micromechanical exfoliation method. The Ti (2 nm)/Au (50 nm) electrodes were then fabricated by E-beam lithography and metal evaporation technique. After annealing the devices under N2 atmosphere at 150 °C for 2 h to improve the contact quality, the electrical and photosensitive properties were then measured before and after surface doping at room temperature and ambient environment. The optical microscope and atomic force microscopy images of the device are shown in Fig. 1a, b, respectively. The thickness of the device is measured 7.2 nm, suggestive of a 10-layer thick MoS2 channel. To form the MoS2 PN junction in the out-of-plane (vertical) direction of the device channel (Fig. 1c), we employed electronic doping. P-type doping techniques for MoS2 have been reported recently including plasma treatment36, 37, niobium physically doping38, 39, and gold chloride (AuCl3) chemically doping40–42. Among them, AuCl3 doping is one of the most facile approaches for P-type doping of MoS2 and has therefore been employed in this work. Here, we used low-concentrated AuCl3 solutions as P dopants to contain the P-type doping of MoS2 on the top layers of the few layer MoS2 channel. Optimization of the amount of doping has been executed and a concise summary of the progressive doping towards a totally p-type MoS2 channel is shown in the Supplementary Fig. 1. From the transfer characteristics under dark before and after doping as shown in Fig. 1d, the threshold voltage (V T) shifts dramatically from −3 V to 30 V due to the depletion of charges across the PN junction in which electrons from N-MoS2 are compensated by the holes of the P-MoS2, to equilibrate the Fermi level, forming a depletion region and essentially result in a more intrinsic MoS2 channel (Fig. 1d). The effective carrier density calculated from the transfer characteristics drops from 5.6 × 1017 cm−3 to 2.8 × 1014 cm−3 after the formation of the PN MoS2 transistor channel. The calculated mobility after the doping process is slightly reduced from 47 cm2 V−1 s−1 to 13.5 cm2 V−1 s−1, likely due to increased impurity scattering, yet it still remains high enough to serve the purpose of a highly performing phototransistor.

Fig. 1.

MoS2-based phototransistors with an out-of-plane PN homojunction. a Optical microscopy image of the few layer MoS2-based device with Ti/Au as source and drain electrodes, the scale bar is 20 µm. b Atomic force microscopy image of the device depicting a thickness of 7.2 nm. The scale bar is 10 µm. c Schematic diagram of the device after surface doping under light illumination consisting of P-MoS2 on top surface and N-MoS2 underneath. The photo-excited holes remain trapped in P-MoS2 while the electrons transport and recirculate in N-MoS2 channel. d Transfer characteristics of the pure N-MoS2 detector and surface doped device with an out-of-plane PN junction, showing the V T shift towards positive-gate voltage

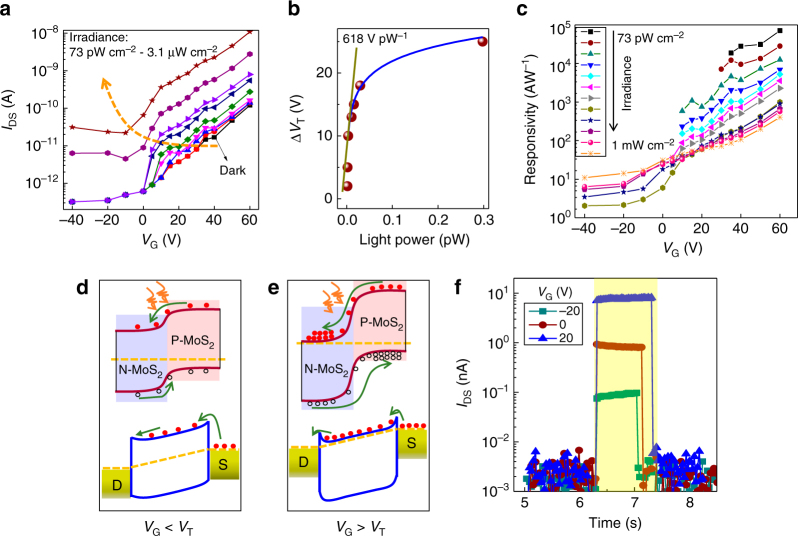

Operation mechanism and responsivity

Now we turn to the underlying mechanism of photodetection in the PN junction-sensitized MoS2 photodetector. In this device, the bottom N-MoS2 serves as the carrier transport channel while the top P-MoS2 is effectively isolated from the metal contacts due to the large Schottky barrier37. Upon light illumination, photo-generated carries in the PN junction are spatially separated under the internal built-in field of the junction with holes transferred to the P-type region and electrons populating the N-type MoS2 channel (Fig. 1c). This acts effectively as a photo-gating effect where the presence of these charges modulates the conductance of the N-MoS2 channel. By applying drain source bias V DS, photo-generated electrons drift and recirculate in the N-MoS2 channel before they recombine with the holes present in the P-MoS2. The recombination is retarded due to the formation of the built-in field across the out-of-plane PN junction giving rise to the possibility of photoconductive gain as the ratio of the carrier lifetime τ life over the transit time τ transit. Figure 2a shows the back-gate dependence of source drain current under dark and light illumination at different intensities. V T shifts gradually from 30 V to −10 V with increasing light intensity due to the accumulation of photo-generated electrons in the N-MoS2 channel under illumination. The V T change (∆V T) induced by the photo-gating effect is plotted in Fig. 2b and reaches a value as high as 618 V pW−1. The ∆V T shift provides a direct measure of the external quantum efficiency (EQE) given as the number of photo-generated charges transferred to the N-type MoS2 channel per single incident photon. The equation that describes this is given as:

| 1 |

where Q is the number of photo-induced charges; q is the elementary charge; n is the number of incident photons per second; P is the incident optical power; C is the capacitance which can be given by equation C = ε 0 ε r A/d, where ε 0 is vacuum dielectric constant, ε r (3.9) and d (285 nm) are dielectric constant and thickness of SiO2, respectively, A is active area of the detector; , where λ is the wavelength, h is the Planck’s constant, c is the speed of light, and τ is the time constant of the detector; here is 618 V pW−1. Based on this calculation the EQE is estimated at ~10% at 635 nm for an experimentally measured time constant of 50 ms at the same experimental conditions that the detector has been characterized. This EQE value is several orders of magnitude higher than prior reports in 2D semiconductors6, 8, 43–46 and it is rather remarkable considering a photodetector thickness of only 7 nm thanks to the very high absorption of the 2D-TMD active layer.

Fig. 2.

Underlying mechanism of photodetection in the detector. a Back-gate dependence of drain current under dark and different irradiance intensities, the orange dash arrow shows the V T shift towards negative gate voltage with increasing illumination intensity due to the photo-gating effect. b V T shift (∆V T) as a function of light power on the detector, the blue line is the non-linear fitting at relatively high light power regime and the dark yellow line shows a slope as high as 618 V pW−1 at low light power. c Responsivity of the device as a function of back gate at V DS of 10 V and under varying irradiance, demonstrating the increased responsivity and more sensitive detection capability by applying large-positive gate voltage. d Energy band diagram of the out-of-plane PN junction at the interface (top panel) and the N-MoS2 transport channel (bottom panel) with applied bias under V G < V T. e The same with d but under V G > V T showing the more efficient charge separation and recirculation due to the larger built-in field and negligible contact barrier. f Temporal response of the device at different back-gate voltage and V DS of 10 V and under irradiance of 31.7 µW cm−2

The electrical response of the detector upon illumination is determined by its responsivity defined as:

| 2 |

in units of A W−1, where I ph is the photocurrent; P is the incident light power density and S is the active area. Figure 2c shows the responsivity dependence of the detector on the backgate voltage at various optical intensities reaching a value as high as 7 × 104 A W−1 for the lowest incident detectable power of the detector at 0.25 fW. The detector operates most sensitively at a back-gate voltage in the range of 40–60 V which is close to the maximum transconductance point. The dependence of responsivity on the backgate bias can be explained from the schematic diagram of the energy band of the device under negative and positive gate with the applied bias shown in Fig. 2d, e, respectively. Due to the charge screening effect of the N-MoS2 underneath47, the back-gate modulates mainly the Fermi level in the N-MoS2 channel, leaving the top P-MoS2 layer unaffected. At negative gate bias, the N-MoS2 is depleted with the Fermi level falling at the middle of the band gap. Thus the built-in field of the out-of-plane PN junction is reduced due to the lack of electrons in the N-MoS2 to compensate the holes of the P-MoS2. This leads to a low built-in field, essential for efficient charge separation (top panel in Fig. 2d) as well as a large Schottky barrier contact between the drain source electrodes and the N-MoS2 channel that further hinders charge recirculation and therefore gain (bottom panel in Fig. 2d). On the other hand, the built-in field increases by applying a positive gate bias with the Fermi level in the N-MoS2 moving towards the conduction band. This facilitates a more efficient charge separation across the PN junction (top panel in Fig. 2e) as well as the possibility of gain in view of the formation of Ohmic contacts of the N-MoS2 channel with the drain and source electrodes (bottom panel in Fig. 2e). The gate-modulated Fermi level and effective contact barrier height is consistent with previous reports11, 48, the decreased effective contact barrier by increasing the back gate is due to the reduced depletion width (i.e., sharp band bending near the contact) that improves the thermionic emission or thermally assisted tunneling process. The significant charge transport reported in the out-of-plane direction of MoS2 49, 50 also supports the effective charge separation and transfer under the built-in field in the out-of-plane PN junction reported herein.

To confirm the above mechanism and to ensure that the transistor channel is governed by the N-type MoS2 whereas the P-type MoS2 serves as a sensitizing layer, we have also implemented an insulating Al2O3 window layer to prevent the p-type doping of the MoS2 near the contacts and ensure that the source and drain electrodes are in contact solely with the N-type MoS2 channel. These detectors performed equally well with the ones reported in the main text (Supplementary Fig. 2). Further doping of the devices with and without Al2O3 window was also carried out to heavily dope the MoS2 channel and eventually collapse the formation of the PN junction. Responsivity and sensitivity deteriorated significantly upon this (Supplementary Figs. 3, 4) due to the absence of the photo-sensitizing scheme in this case, which further confirms the important contribution of the out-of-plane MoS2 PN junction to the high performance reported.

Temporal response and sensitivity

The temporal photo-response of the detector is measured under different back-gate values (Fig. 2f), yielding a relaxation timescale of 10 ms, significantly faster than that of pure MoS2 photodetectors (Supplementary Fig. 5 and refs. 11, 25) at irradiance of tens of μW cm−2. To determine the gain of the detector defined as:

| 3 |

we first consider the τ transit, which is inversely proportional to the electron mobility and can be defined as , where L is length of the channel, µ is the mobility and V DS is the applied bias; thus the transit time is calculated to be ~32 ns. From the temporal response of the sensitized detectors at much lower irradiance levels (shown in Fig. 3b), the carrier lifetime is estimated on the order of 50 ms. As a result, multiple electrons are recirculated in the MoS2 channel following a single electron–hole photo-generation, leading to a photoconductive gain on the order of 105. This allows us then to estimate the EQE of the detector from the formula:

| 4 |

where λ is the wavelength, q is the elementary charge, h is the Planck’s constant, and c is the speed of light. Based on this, the EQE of the detector is calculated at 9% in very good agreement with the calculation of EQE based on the ∆V T shift.

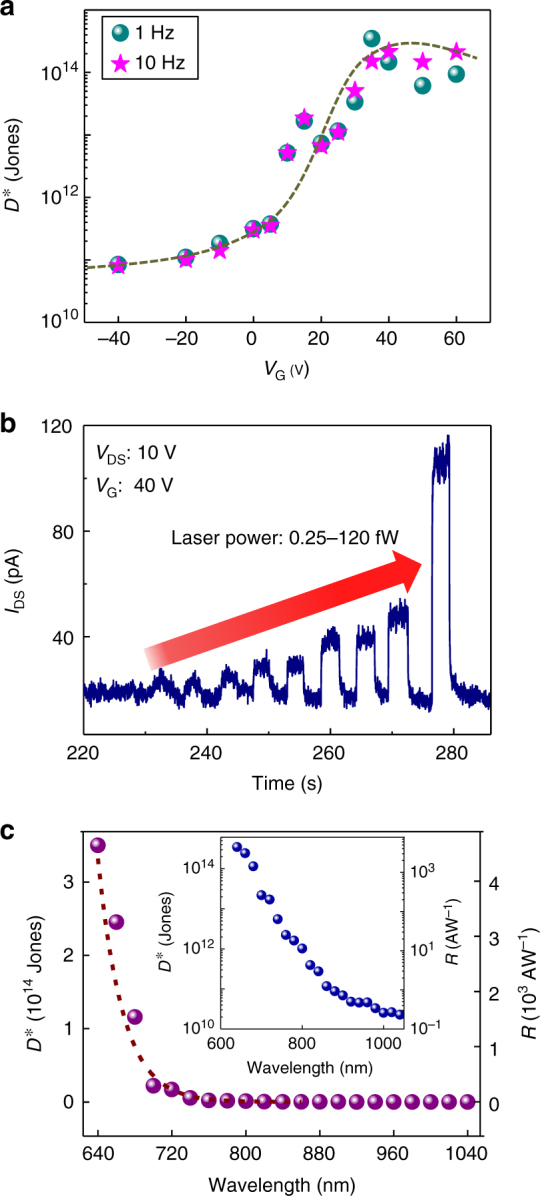

Fig. 3.

Ultrahigh sensitivity and spectrum. a Specific detectivity as a function of back-gate voltage at V DS of 10 V and optical modulated frequency of 1 Hz and 10 Hz, the dash line is a guide to the eye. b Time dependence of photo-response with increasing irradiance showing a direct measurement of laser power as low as 0.25 fW. c Spectral detectivity and responsivity under irradiance of 1 nW cm−2 and at V DS of 10 V and V G of 35 V, the insert is the spectrum with log scale for y-axis showing the extended spectrum to near-infrared region (1000 nm) with high sensitivity

Besides the high responsivity recorded, another key feature for ultrasensitive photodetection is the low noise current floor. The details of the noise analysis of the photodetector is summarized in Supplementary Fig. 6. Briefly, with applying a constant drain bias and back gate, the time-resolved dark current is measured. By taking the Fourier transform of dark current traces, the noise power densities are obtained as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6b, then the noise spectral densities S n are extracted at frequencies of 1 Hz and 10 Hz under exactly the same conditions as the optical measurements were performed (same V G and V DS), resulting in noise values between 0.1 pA Hz−1/2and 1.4 pA Hz−1/2 in the whole back-gate range (Supplementary Fig. 6c). To experimentally assess the sensitivity of the detector, we measured the specific detectivity which is defined as:

| 5 |

in units of cm Hz1/2 W−1 (or Jones), where NEP is the noise equivalent power in W, R is the responsivity in A W−1, A is the active area of the detector in cm2, B is the noise bandwidth in Hz, and S n is the noise current spectral density of the detector in A Hz−1/2. Figure 3a illustrates the as function of the back-gate voltage. increases with increasing backgate to reach its maximum value at the point which the maximum transconductance of the N-type MoS2 transistor coincides with the maximum EQE of the detector and the preservation of low-dark current. In this regime the reaches a value range of 1 × 1013 Jones to 3.5 × 1014 Jones at modulation frequencies of 1 Hz and 10 Hz, respectively, the highest recorded to date for any 2D-based photodetector. This high results from the highly efficient charge separation, large photoconductive gain as well as the very low noise spectral density in this class of 2D-only based photodetectors. The reported is higher by at least two orders of magnitude over prior reports of 2D materials based photodetectors11, 24–35 and on par with bulky silicon photomultiplier detectors51. Thanks to the high sensitivity of the detector we have directly measured optical power as low as 0.25 fW using an source-measure unit (SMU)-based semiconductor parameter analyser (Fig. 3b) which determines the noise equivalent power (NEP) of the detector in broad bandwidth conditions that is compatible with and used in standard complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) readout electronics. Considering an integrated noise bandwidth of 50 Hz that corresponds to the sampling rate of 20 ms, the is found to be ~5.2 × 1013 Jones, the highest ever reported and directly measured under broad bandwidth conditions in any class of 2D-based photodetector. The reported photodetector exhibits a greater than 1013 Jones for wavelengths up to 700 nm. Due to the multilayer nature of the MoS2 selected as the transport channel and absorption layer, the optical spectral coverage of our detectors is extended from visible to near-infrared region (Fig. 3cc) in agreement with the band gap of ~1.2 eV of multilayer MoS2 1, 12.

Discussion

This work reports an ultrasensitive detector comprising solely 2D-TMDs materials enabled by band engineering in the out-of-plane direction through doping. It is noted that the optimized thickness of MoS2 in this work was found to be 7–11 nm (see details in Supplementary Figs. 7–9). The formation of the out-of-plane PN junction serves as a novel sensitizing mechanism for 2D-TMDs phototransistors and paves the way towards the use of the concept in other 2D semiconductors or in combination of those to facilitate sensitization, particularly those possessing low band gap to extend the spectral coverage of the 2D materials realm.

Methods

Device fabrication

The MoS2 crystals were purchased from the 2D semiconductors corporation. The few layer MoS2 was then exfoliated with PDMS tape on Si/SiO2 (285 nm) wafer using the micromechanical exfoliation method. Before the device fabrication, the substrate with MoS2 on top was soaked into acetone for 2 h at 60 °C to remove the residual glue. Metal contacts were then fabricated by the laser writing lithography, and Ti (2 nm) and Au (50 nm) electrodes were evaporated by e-beam and thermal evaporation, respectively. Finally, the devices were annealed at 150 °C for 2 h under high purity of N2 atmosphere to improve the contact quality. For the devices with Al2O3 window, both electrodes were covered by insulating Al2O3 with atomic layer deposition technique (ALD) (Savannah 200, Cambridge Nanotech). The ALD process was performed in 300 cycles leading to ~30 nm of oxide thickness.

AuCl3 solution preparation and surface doping

The synthesis of AuCl3 dopant is according to the previous reports40–42. Briefly, 30 mg gold chloride (AuCl3) powders (≥99.99 %, Sigma Aldrich) were dissolved in the 5 ml nitromethane (≥95 %, Sigma Aldrich), then the solutions (20 mM) were sonicated for 3 h at 60 degrees followed by filtration to filter the large Au aggregates. The 20 mM AuCl3 solutions were then diluted with different concentration (10 mM and 5 mM). Note that all operations were performed in glove box to protect the reagents from the air environment. About 3–5 drops of 5 mM AuCl3 solutions were dropped on the SiO2/Si substrate with MoS2 devices on top and spin-coated at 3000 rpm for 1 min, then baked on the hotplate at 100 °C for 5 min.

Device characterization

All the measurements were performed in ambient conditions using an Agilent B1500A semiconducting device analyzer. For spectral photo-response measurements the devices were illuminated with fiber-coupled and spectrally filtered light from a supercontinuum light source (SuperKExtreme EXW-4, NKT Photonics). Responsivity and temporal response times were measured under short-pulsed light at a wavelength of 635 nm from a four-channel laser controlled with an Agilent A33220A waveform generator. Several dark current traces were measured with the Agilent system (Agilent B1500A) under exactly the same conditions as the optical measurements were performed (same V G and V DS) at a sampling rate of 50 Hz. We obtained the noise spectral density by calculating the Fourier transformation of dark current traces.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, through the “Severo Ochoa” Programme for Centres of Excellence in R&D (SEV-2015-0522), support by Fundacio Cellex Barcelona, and CERCA Programme / Generalitat de Catalunya. Furthermore, the research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union H2020 Programme under grant agreement n°696656 Graphene Flagship, the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) and the “Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional” (FEDER) through grant MAT2014-56210-R as well as AGAUR under the SGR grant (2014SGR1548).

Author contributions

G.K. supervised the study. N.H. fabricated and characterized the devices. G.K. and N.H. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00722-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang QH, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kis A, Coleman JN, Strano MS. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotech. 2012;7:699–712. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koppens FHL, et al. Photodetectors based on graphene, other two-dimensional materials and hybrid systems. Nat. Nanotech. 2014;9:780–793. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mak KF, Shan J. Photonics and optoelectronics of 2D semiconductor transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Photon. 2016;10:216–226. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2015.282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britnell L, et al. Strong light-matter interactions in heterostructures of atomically thin films. Science. 2013;340:1311–1314. doi: 10.1126/science.1235547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Withers F, et al. Light-emitting diodes by band-structure engineering in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:301–306. doi: 10.1038/nmat4205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pospischil A, Furchi MM, Mueller T. Solar-energy conversion and light emission in an atomic monolayer p-n diode. Nat. Nanotech. 2014;9:257–261. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furchi MM, Polyushkin DK, Pospischil A, Mueller T. Mechanisms of photoconductivity in atomically thin MoS2. Nano Lett. 2014;14:6165–6170. doi: 10.1021/nl502339q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross JS, et al. Electrically tunable excitonic light-emitting diodes based on monolayer WSe2 p–n junctions. Nat. Nanotech. 2014;9:268–272. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koperski M, et al. Single photon emitters in exfoliated WSe2 structures. Nat. Nanotech. 2015;10:503–506. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, et al. Strong light-matter coupling in two-dimensional atomic crystals. Nat. Photon. 2015;9:30–34. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2014.304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Sanchez O, Lembke D, Kayci M, Radenovic A, Kis A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat. Nanotech. 2013;8:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mak KF, Lee C, Hone J, Shan J, Heinz TF. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:136805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.136805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radisavljevic B, Radenovic A, Brivio J, Giacometti V, Kis A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotech. 2011;6:147–150. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui X, et al. Multi-terminal transport measurements of MoS2 using a van der Waals heterostructure device platform. Nat. Nanotech. 2015;10:534–540. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumcenco D, et al. Large-area epitaxial monolayer MoS2. ACS Nano. 2015;9:4611–4620. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang K, et al. High-mobility three-atom-thick semiconducting films with wafer-scale homogeneity. Nature. 2015;520:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature14417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massicotte M, et al. Picosecond photoresponse in van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Nanotech. 2016;11:42–46. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee C-H, et al. Atomically thin p-n junctions with van der Waals heterointerfaces. Nat. Nanotech. 2014;9:676–681. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, et al. Persistent photoconductivity in two-dimensional Mo1−xWxSe2–MoSe2 van der Waals heterojunctions. J. Mater. Res. 2016;31:923–930. doi: 10.1557/jmr.2016.35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konstantatos G, et al. Hybrid graphene-quantum dot phototransistors with ultrahigh gain. Nat. Nanotech. 2012;7:363–368. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kufer D, et al. Hybrid 2D-0D MoS2-PbS quantum dot photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:176–180. doi: 10.1002/adma.201402471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikitskiy I, et al. Integrating an electrically active colloidal quantum dot photodiode with a graphene phototransistor. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11954. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huo N, Gupta S, Konstantatos G. MoS2-HgTe quantum dot hybrid photodetectors beyond 2 µm. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1606576. doi: 10.1002/adma.201606576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin Z, et al. Single-layer MoS2 phototransistors. ACS Nano. 2011;6:74–80. doi: 10.1021/nn2024557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HS, et al. MoS2 nanosheet phototransistors with thickness-modulated optical energy gap. Nano. Lett. 2012;12:3695–3700. doi: 10.1021/nl301485q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi W, et al. High-detectivity multilayer MoS2 phototransistors with spectral response from ultraviolet to infrared. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:5832–5836. doi: 10.1002/adma.201201909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, et al. High-gain phototransistors based on a CVD MoS2 monolayer. Adv. Mater. 2013;25:3456–3461. doi: 10.1002/adma.201301244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kufer D, Konstantatos G. Highly sensitive, encapsulated MoS2 photodetector with gate controllable gain and speed. Nano Lett. 2015;15:7307–7313. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miao J, et al. Surface plasmon-enhanced photodetection in few layer MoS2 phototransistors with Au nanostructure arrays. Small. 2015;11:2392–2398. doi: 10.1002/smll.201403422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, et al. Ultrasensitive and broadband MoS2 photodetector driven by ferroelectrics. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:6575–6581. doi: 10.1002/adma.201503340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon J, et al. Giant photo amplification in indirect-band gap multilayer MoS2 phototransistors with local bottom-gate structures. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:2224–2230. doi: 10.1002/adma.201404367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen C, et al. Highly responsive MoS2 photodetectors enhanced by graphene quantum dots. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11830. doi: 10.1038/srep11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roy K, et al. Graphene-MoS2 hybrid structures for multifunctional photoresponsive memory devices. Nat. Nanotech. 2013;8:826–830. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, et al. Ultrahigh-gain photodetectors based on atomically thin graphene-MoS2 heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:3826. doi: 10.1038/srep03826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu H, et al. High responsivity and gate tunable graphene-MoS2 hybrid phototransistor. Small. 2014;10:2300–2306. doi: 10.1002/smll.201303670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue F, et al. p-type MoS2 and n-type ZnO diode and its performance enhancement by the piezophototronic effect. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:3391–3398. doi: 10.1002/adma.201506472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nipane A, Karmakar D, Kaushik N, Karande S, Lodha S. Few-layer MoS2 p-type devices enabled by selective doping using low energy phosphorus implantation. ACS Nano. 2016;10:2128–2137. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b06529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laskar MR, et al. p-type doping of MoS2 thin films using Nb. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014;104:092104. doi: 10.1063/1.4867197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suh J, et al. Doping against the native propensity of MoS2: degenerate hole doping by cation substitution. Nano Lett. 2014;14:6976–6982. doi: 10.1021/nl503251h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X, et al. P-type polar transition of chemically doped multilayer MoS2 transistor. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:2345–2351. doi: 10.1002/adma.201505154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi MS, et al. Lateral MoS2 p-n junction formed by chemical doping for use in high-performance optoelectronics. ACS Nano. 2014;8:9332–9340. doi: 10.1021/nn503284n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li HM, et al. Ultimate thin vertical p-n junction composed of two-dimensional layered molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6564. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xia F, Mueller T, Lin Y-M, Valdes-Garcia A, Avouris P. Ultrafast graphene photodetector. Nat. Nanotech. 2009;4:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mueller T, Xia F, Avouris P. Graphene photodetectors for high-speed optical communications. Nat. Photon. 2010;4:297–301. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2010.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gabor NM, et al. Hot carrier-assisted intrinsic photoresponse in graphene. Science. 2011;334:648–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1211384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baugher BWH, Churchill HOH, Yang Y, Jarillo-Herrero P. Optoelectronic devices based on electrically tunable p-n diodes in a monolayer dichalcogenide. Nat. Nanotech. 2014;9:262–267. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castellanos-Gomez A, et al. Electric-field screening in atomically thin layers of MoS2: the role of interlayer coupling. Adv. Mater. 2013;25:899–903. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Das S, Chen H, Penumatcha AV, Appenzeller J. High performance multilayer MoS2 Transistors with scandium contacts. Nano Lett. 2013;13:100–105. doi: 10.1021/nl303583v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu WJ, et al. Highly efficient gate-tunable photocurrent generation in vertical heterostructures of layered materials. Nat. Nanotech. 2013;8:952–958. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu WJ, et al. Vertically stacked multi-heterostructures of layered materials for logic transistors and complementary inverters. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:246–252. doi: 10.1038/nmat3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dereniak, E. L. & Boreman, G. D. Infrared Detectors and Systems (Wiley publishing, 1996).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.