Abstract

The advent of immunotherapy is currently revolutionizing the field of oncology, where different drugs are used to stimulate different steps in a failing cancer immune response chain. This review gives a basic overview of the immune response against cancer, as well as the historical and current evidence on the interaction of radiotherapy with the immune system and the different forms of immunotherapy. Furthermore the review elaborates on the many open questions on how to exploit this interaction to the full extent in clinical practice.

INTRODUCTION

Only recently, it was noticed that radiotherapy and immunotherapy together can lead to a more effective anti-tumour response than each of the both modalities apart. The interactions between radiation and immune system have become a new area of intense research within cancer research programmes. The goal of this review is to provide the reader an overview of the new strategy combining radiotherapy with immunotherapy, including its earlier development, its current state and the next steps required to bring this new approach to a success in general clinical practice.

BASIC OVERVIEW OF THE ANTI-TUMOUR IMMUNE RESPONSES

A cancer cell is characterized by the loss of its normal regulatory processes, which gives rise to uncontrolled cell growth and formation of metastases.1 90% of cancer deaths are not related to primary tumour but rather attributable to metastatic disease.2 The molecular basis of this distinct behaviour is governed by aberrant proteins, also called oncoproteins, regulating several biological processes such as cytostasis and differentiation, viability and apoptosis, proliferation and motility, gene regulation, deoxyribonucleic acid repair etc.1,3,4

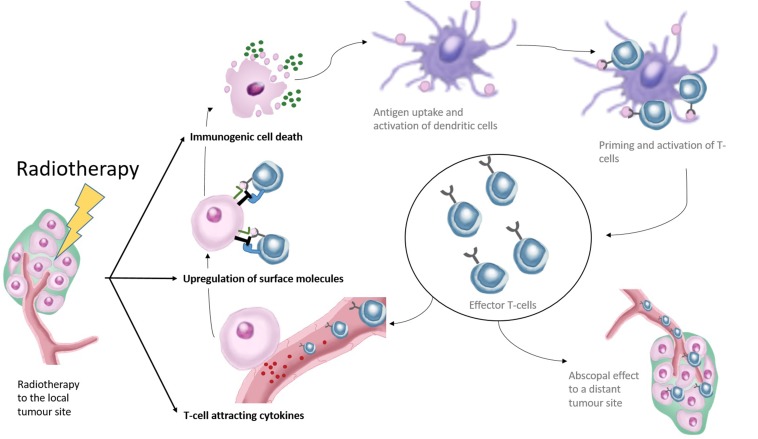

Normally, the immune system protects the host against the formation of cancer, following a process known as the cancer immunity cycle.5 First, specific antigens are released by the cancer cells which are picked up by antigen-presenting dendritic cells to activate and prime naïve T lymphocytes. Hereby, a very specific reactivity against antigens from the tumour cells is generated. Subsequently, these activated T cells infiltrate a tumour to recognize and destroy the cancerous cells. Then, dendritic cells pick up antigens of dying cancer cells again, restarting the whole process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

This figure shows the effects of radiotherapy in relation to the cancer immune cycle. Radiotherapy affects the immune response by induction of immunogenic cell death releasing new antigens to the components of the immune system. This subsequently leads to improved priming and activation of effector T cells. Radiotherapy further leads to increased expression of surface molecules on the irradiated cancer cells making them more vulnerable to cytotoxic T-cell-mediated cell killing. Finally, radiotherapy leads to the release of cytokines attracting T cells towards the irradiated tumour. Improved influx of effector T cells and improved T-cell killing of cancer cells could result in new antigen presented to the components of the immune system.

Among several subclasses of T lymphocytes, there are two major subtypes governing the cellular immunity against cancer: the cytotoxic or CD8+ T cells and the T-helper (Th) or CD4+ cells. Progenitor Th cells can differentiate in two different subtypes: (a) the effector Th (Th1) cell, which stimulates the dendritic cells and the cytotoxic T cells using surface receptors and by producing ligands such as CD40L and IL2, respectively,6–8 and (b) the regulatory Th cell or Treg, recognized by nuclear FOXp3 expression,9,10 which hamper the immune response. The physiological function of the latter is to protect against autoimmunity.11

In cancer, however, the above-described normal immune response is deregulated, allowing cancer cells to escape from the immune system and survive. As the cancer immunity cycle is a very complex sequential process, it can fail when at least one essential link is disrupted. The reason for a failed immune response can be diverse and several mechanisms allowing the tumour to escape exist. Such possibilities are, for example, “tumour foreignness” questioning whether there are enough neoantigens that make it possible for the tumour to be recognized as foreign; general immune status of the patients defining if there are enough lymphocytes to combat the tumour; hampered intratumoural immune cell infiltration; the presence of immune T-cell checkpoints and ligands blocking cytotoxic T-cell activity, among many others (for more details, see the cancer immunogram12).

THE PAST: FIRST INDICATIONS OF AN INTERACTION BETWEEN RADIOTHERAPY AND THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

A strong relation between the radiosensitivity of the irradiated tumour (murine fibrosarcoma) and the immunocompetence of the host has already been described in a pre-clinical research article dating back to 1979. The dose needed to control the tumour in 50% (TCD50) of immunosuppressed mice was about double the dose that was needed in immunocompetent mice.13 Consistent with these results, chemoradiotherapy in mice bearing tumours from tumourigenic tonsillar epithelial cells was more efficient in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice than in their immunosuppressed C57BL/6 rag-1-deficient counterparts.14

Radiotherapy has always been regarded as a highly effective but local therapy for cancer. However, >20 case reports in the whole medical literature describe tumour regressions outside of the radiation treatment fields.15 This effect was referred to as the abscopal effect, derived from the Latin word ab scopus meaning on a distant site. The underlying mechanism of these off-target effects remained obscure, and because of their rareness, these events were regarded as medically not relevant. In the early days, several pre-clinical studies evaluated the effect of local irradiation on distant tumour sites, but the results were not consistent; both inhibition and acceleration of the non-irradiated tumour sites were seen.16

Although these findings were interesting, they went without much attention within the scientific community. That is, until the breakthrough of immunotherapy within the field of oncology, which started in 2010 with a Phase III trial investigating ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma, showing for the first time a survival benefit.17 The following period was a rollercoaster of clinical successes, with immunotherapy being declared the scientific breakthrough of the year in 2013 by the Science magazine.18 During this period, two case reports were published of a patient progressive under ipilimumab, now showing responses to radiotherapy outside the irradiated area which were linked to a response of the immune system.19,20 The events described in these case reports were consistent with earlier pre-clinical work demonstrating a synergy between CTLA-4 blockade and radiotherapy.21,22 Also, at the same time, a Phase I trial was published combining stereotactic body radiation therapy together with high dose of IL2 in renal cell carcinoma and melanoma. The authors found a response rate that was much higher than what would be expected based on historical data from IL2-based treatment alone.23 The promising results of these clinical studies raised a lot of interest in the field of immunotherapy including in combination with radiation.

THE PRESENT: IMMUNOTHERAPY AS STANDARD OF CARE, AND EXTENSIVE PRE-CLINICAL EVIDENCE ON THE INTERACTION OF RADIOTHERAPY WITH IMMUNOTHERAPY

Over the past few years numerous Phase III trials have demonstrated immunotherapy to confer an overall survival benefit in advanced, recurrent or metastatic melanoma,17,24 non-small-cell lung cancer,25–29 renal cell cancer,30 head and neck cancer,31 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder32 and prostate cancer.33 In general, these therapies did show a favourable toxicity profile. Clearly, based on these results one can say that a corner has been turned and a new era in oncology has begun. However despite these successes, not surprisingly, these immunotherapies show only benefit in a limited number of patients because they affect only very specific points/processes in the cancer immunity cycle, and in addition, resistance mechanisms by tumour cells may be acquired during therapy or may be elicited by the tumour microenvironment. Apart from Sipuleucel-T (Provenge®) in prostate cancer, which is an active cellular-based vaccine,33 the other forms of immunotherapy depend on checkpoint blockade. These are very specific antibody-based checkpoint inhibitors such as CTLA-4-directed ipilumumab or PD-1/PD-L1 axis inhibitors such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab and atezolizumab. In essence, CLTA-4 inhibitors work by blocking a specific inhibitory interaction between the dendritic cell and the T cell.34 PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors block a specific inhibitory interaction between the effector T cell and the cancer and/or dendritic cell, which normally leads to inhibition of T-cell growth and loss of effector functions.35

On the momentum of the success of these new forms of immunotherapies, several efforts were made to study the interaction of radiotherapy and the immune system in more depth, aiming to exploit the current immunotherapy successes even further. How radiotherapy contributes to an enhanced immune response has been reviewed in detail elsewhere.36–39 A recent and extended review focusing on the molecular pathways involved can be found here.40 To summarize, radiotherapy has been shown to trigger the immune response by (1) induction of immunogenic cell death (ICD) broadening up the immune repertoire of T cells, (2) recruitment of T cells towards the irradiated tumour and (3) increasing vulnerability towards T-cell-mediated cell killing (Figure 1). ICD is associated with a pre-mortem stress response allowing the cell to attract the attention of the immune system.39 This process allows the immune system to distinguish cell death from a pathogenic process (e.g. viral infection or cancer) or cell death in the context of normal tissue homeostasis.39 ICD is characterized by the release of tumour-associated antigens in the form of apoptotic bodies and debris, together with adenosine triphosphate, calreticulin, HBMG-1, which induce dendritic cell recruitment and result in their activation, antigen uptake and maturation.37–39 By doing so, radiotherapy delivers new antigens to the adaptive immune system, promoting the priming and generation of new anti-tumour T cells. Secondly, radiation recruits effector T cells towards the tumour by releasing T-cell-attracting chemokines such as CXCL-9 and CXCL-10.41 Interestingly, CXCL-10 secretion has also been linked to the process of ICD through type I interferon signalling.39 Thirdly, radiotherapy induces a transient overexpression of MHC class I and Fas surface receptors rendering tumour cells more vulnerable to cytotoxic T-cell killing.42–45 However, obviously, radiotherapy alone is not sufficient to induce curative anti-tumour immune response especially against metastatic cancer, highlighting the need for combinatorial immunotherapy approaches to boost immune system.

Numerous pre-clinical studies reported improvement of the local radiotherapy and/or abscopal response with CTLA-4 inhibitors.21,22,46–49 Interestingly, a retrospective case series on 101 patients treated with ipilimumab seems to confirm these findings. Of these 101 patients, 70 patients received concurrent radiotherapy. These 70 patients showed a significant increase in overall survival over the patients who did not receive concurrent radiotherapy, as well as increases in response.50 The interaction of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition with radiotherapy has also been reported to enhance both local51–55 and abscopal effects.53,56 Furthermore, in the context of radiotherapy, there seems to be a clinical rationale to combine PD-1-directed therapy and CTLA-4 as both immunotherapeutic agents activate non-redundant immune mechanisms.48 IL2 is a cytokine with an essential role in the activation of immune response. Although it also stimulates proliferation of regulatory T cells, it also activates cytotoxic T and natural killer cells resulting in an activation of the immune system augmenting together with radiotherapy local as well as abscopal tumour responses.57 As IL2 is associated with significant morbidity (capillary leak syndrome, ischaemia, flu-like syndromes),58 efforts were made to reduce its toxicity by making its delivery more tumour specific.59 These tumour-targeting “immunocytokines”, such as NHS-IL2 (targeting free deoxyribonucleic acid) and L19-IL2 (targeting external domain B (EDB) of fibronectin in newly formed vessels), have shown to enhance local radiotherapy effects.60–62 L19-IL2 was only effective in tumours expressing EDB, and the effect was greatly dependent on the presence of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.62,63 However, even in a MHC class I-deficient tumour model, where cancer cytotoxicity is not dependent on specific antigen-targeted activity of the CD8+ T cells but rather on natural killer cell activity, an additive effect of radiotherapy over L19-IL2 alone was seen.60 Our research group has also found an abscopal effect of radiotherapy/L19-IL2 combination on secondary non-irradiated tumours (Personal communication Dr Rekers, presented at ESTRO 35, 2016). These results are in line with an earlier clinical study evaluating high dose IL2 treatment with stereotactic radiotherapy showing much higher than expected clinical response rates for an extended period of time.23

These promising data provided a rationale for the start of a multitude of currently running clinical trials (>70), testing combinations of radiotherapy (fractionated or stereotactic body radiation therapy) together with CTLA-4 inhibition, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition, vaccination or cytokine treatment such as IL2, anti-transforming growth factor-beta or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Recent overviews of ongoing radiotherapy–immunotherapy trials are provided elsewhere;64–66 for an up-to-date version, see clinicaltrails.gov.

THE FUTURE: INTEGRATING RADIOTHERAPY AND IMMUNOTHERAPY IN THE CLINICAL SETTING

To optimize a radiotherapy regimen or treatment in the context of immunotherapy, several factors need to be considered. These are optimal fractionation schedule and dosing, the timing between radiotherapy and immunotherapy, the radiotherapy technique to deliver the dose, implications for the clinical target volume (CTV), lesion selection and safety.

When considering fractionation and dose to be combined with immunotherapy, one must first consider the goal of the treatment approach: does the treatment aim for an improved local effect or to create an abscopal effect on the non-irradiated (micro) metastasis? As described above, radiotherapy stimulates the immune system by broadening up the immune repertoire of T cells (vaccination effect), by attracting T cells to the irradiated site (homing effect) and by rendering irradiated cells more vulnerable towards T-cell-mediated cell kill (vulnerability effect). It is expected that only the broadened immune repertoire is useful for the immune system to produce a generalized systemic response, meaning that the underlying biology is different and perhaps more critical when one aims for an abscopal response. Several groups have investigated different fractionation schedules and doses. Gandhi et al67 provided recently a very extensive review on the matter. Several authors describe a dose-dependent increase of cell surface molecules such as FAS, MHC1 or ICAM142,44,45 using doses varying between 1 and 50 Gy in humans (HCT116 colorectal carcinoma and Mel JuSo melanoma) and murine (MC38 colon carcinoma) cell lines. As these receptors are important for T-cell vulnerability, they are presumed in the first place to be important for enhancing the local effect of radiotherapy. When comparing fractionated (5 × 3 Gy) and single-dose (15 Gy) radiotherapy in a B16 melanoma model in their capacity to activate dendritic cells in the lymph nodes (as measured by activation/priming of a hybrid reporter T-cell line), it was demonstrated that 15-Gy single dose was more efficient.41 By contrast, in a similar tumour model (B16-OVA melanoma), another group showed T-cell priming, this time measured by an INFγ Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSpot assay on splenic T cells, to be more efficient with 2 × 7.5 Gy than 15-Gy single dose.68 Several groups did also investigate the impact of fractionation when combining radiotherapy with immunotherapy. Dewan et al21 showed that while all fractionation schedules showed comparable local tumour control as monotherapy in combination with CLTA-4 inhibition, 3 × 8 Gy was superior to 5 × 6 or 1 × 12 Gy in a TSA breast and MCA38 colon carcinoma model, with respect to local tumour control and abscopal response. Clinical data from a retrospective review in patients with melanoma receiving ipilimumab suggested fraction doses ≤3 Gy to be associated with abscopal responses.69 By contrast, work from our group investigating the interactions of the L19-IL2 immunocytokine with radiotherapy in a C51 tumour model show that a larger dose per fraction is more efficient to induce an abscopal response, as only 1 × 15 Gy and not 5 × 5 or 5 × 2 Gy was able to induce tumour cure of the non-irradiated tumours. However, fractionated irradiation was as efficient as single-dose irradiation in eradication of the primary locally irradiated tumours (unpublished data). To conclude, fractionation and dose are of vital importance to maximize the effect of associated immunotherapy, but no consensus exists on which schedule is optimal. The conflicting results from the literature let us presume that optimal fractionation is highly context dependent, and therefore conclusions should be cautiously drawn. Insights may come from clinical trials, evaluating local and/or abscopal response to (different kinds of) immunotherapy combined with different fractionation schedules. This is, however, a cumbersome procedure and only allows for indirect measurement of the immune-stimulating radiotherapy effect. As tumour response is not only dependent on the radiotherapy schedule but also on the elements in the cancer immune cycle, the impact of choosing the right fractionation schedule when looking at local or abscopal tumour control will be diluted. More elegant and straightforward ways to evaluate the efficiency of different fractionation schedules therefore may rely on innovative new biomarker approaches, such as the release of immunogenic cell death-related chemokines and cytokines70 in blood or biopsies, or on methods allowing large-scale measurement of extension in the T-cell repertoire—novel techniques based on barcode-labelled peptide-MHC-1 multimers are able to screen >1000 T-cell specificities in a single sample.71 Such an approach could allow us to compare the impact and efficiency of different radiotherapy schedules on increasing the variety of specific T-cell responses towards different tumoural antigens.

Treatment techniques such as volumetric modulated arc therapy better shape the volume around the target tissue but also lead to a low-dose bath to a large part of the body.72 Lymphocytes are among the most radiosensitive cells in the body with a D10 (dose to reduce the total amount of surviving cells to 10% of the initial value) of around 3 Gy only.73 In this context, the dose to the tumour-draining lymph nodes and the timing of the fractionation may be of importance, especially in daily fractionated schedules. The normal transit time of a naïve helper of cytotoxic T lymphocyte is 12 h to a day.74 However, when confronted with a dendritic cell-presenting antigen, these T cells remain in contact with the dendritic cell and undergoes a “blasting” transformation. This process again takes another 24 h, even before clonal expansion ensues.75,76 For cytotoxic T cells, however, it was shown that the stable interaction with the dentritic cell was dispensable, still allowing to undergo successful effector differentiation, but long-lived memory was hampered.77 It is possible that even a low dose given in short daily intervals to the lymph nodes may interfere with the priming process of T lymphocytes and its memory functions. The impact of the low-dose bath and daily fractionation to date is unknown and needs further investigation.

Integration of radiotherapy within an immunotherapy schedule may also need rethinking of the classical definitions of target volumes. When, for example, in a more diffusely metastatic patient radiotherapy is added as a form of immune adjuvant, it may not be necessary to expand the target volumes for microscopic tumour extension (CTV or CTV margins) or apply wide margins around the volume to account for deviations in daily treatment setup (planning target volume or planning target volume margins), as it may suffice to irradiate a part of the tumour to induce immune stimulation. The narrower margins would allow for better sparing of the organs at risk, to reduce complication probability. This approach, which is theoretically promising, however, needs validation in clinical trials.

Little is known on the selection of the right target for radiotherapy in the context of creating an abscopal effect together with immunotherapy. Some authors proposed a mathematical model to predict the lesions with the highest potential.78 This model was based on T-cell trafficking and the assumption that abscopal effects can only be achieved when activated T cells from the irradiated tumour can reach the distant sites in sufficient numbers. However, with no clinical data sets to validate this virtual model, extreme care should be taken before using this model in practice, as it lacks many other important parameters determining abscopal responses.79

The timing seems to be of essential importance when embedding radiotherapy into an immunotherapy approach to get the most optimal results. The ideal timing between immunotherapy and radiotherapy depends on the mechanism of action of the specific form of immunotherapy.52,80 For example, Young et al80 investigated the optimal timing of radiation in combination with an OX-40 agonist antibody and a CLTA-4 antagonist antibody. Best results were seen when CTLA-4 was given before radiotherapy. Nonetheless, other authors did find synergistic activity also for CTLA-4 inhibition when given concurrently or sequentially with radiotherapy.21,22 By contrast, OX-40-based immunotherapy worked best when given immediately following radiotherapy.80 The authors proposed that OX-40 would function by boosting antigen-specific T-cell numbers,80,81 whereas anti-CTLA-4 would rather function as a downregulator of regulatory T cells.80,82 Therefore, OX40 inhibition would be most beneficial just following radiation-induced antigen release. It is possible that in the case of CTLA-4 inhibition, antigen release created by radiotherapy is most efficient only when the regulatory T-cell fractions are depleted first. Dovedi et al52 investigated the ideal treatment sequence for inhibition of the PD-1 axis, and found the best effect was found when the PD-L1 was given concurrently or immediately following the radiotherapy. Delaying the PD-L1 infusions for 1 week abrogated the interaction between radiotherapy and PD-1 axis inhibition.83 Inhibition of the PD-1 axis increases the lytic activity of the cytotoxic T cells.35 Therefore, an optimal interaction is expected just at that moment when radiotherapy temporarily induces surface ligands on the cancer cell increasing its vulnerability to T-cell attacks.42–45 The authors also showed that radiotherapy temporarily induced overexpression of PD-1 axis molecules on the tumour cells as well as on the tumour-infiltrating T cells.52 Inhibition of the PD-1 axis is therefore expected to be most efficient when it attenuates the radiation-induced immune response most efficiently, in close temporal relation to the radiation treatment.

Hypoxia is associated with both radioresistance and immune suppression.84,85 This hypoxia can be quantified by hypoxia positron emission tomography tracers such as HX4, FAZA or F-MISO.86,87 Unravelling these resistance mechanisms associated with hypoxia could lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, reducing hypoxia with hypoxia-targeting drugs88,89 could potentially lead to a reduction of immunosuppresion in the tumour microenvironment. Currently, this is an area of active investigation in our research team.

Finally, only limited clinical information is available on the different combinations of immunotherapy and radiotherapy. It is possible that radiation-induced acute toxicity, which is associated with an inflammatory response, could be aggravated by an activation of the immune system following immunotherapy.90 Kroeze et al91 recently reviewed the evidence on stereotactic radiotherapy and concurrent anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Regarding the combination with anti-CTLA4 and cranial stereotactic irradiation, they seem to show that the approach is safe, although the available studies are small. Very limited data are available on the combination of extracranial stereotactic radiotherapy with anti-CTLA4. Regarding the combination of concurrent anti-PD-1/PD-L1, they concluded that there was insufficient data to allow for conclusions. Following this report Levy et al92 published the results of a small Phase I/II trial investigating the combination of the PD-L1 inhibitor durvalumab with conventional and stereotactic radiotherapy. The combination was well tolerated. Kwon et al93 evaluated the combination of 8-Gy conventional radiotherapy followed by ipilimumab vs placebo in a large Phase III trial of metastatic castration-resistant patients with prostate cancer. Although the primary end point (overall survival) was negative, they did not see a higher-than-expected toxicity of the radiotherapy–ipilimumab combination than what would be expected from ipilimumab alone. Two small Phase I trials showed that NHS-IL2- or IL2-based immunotherapy could be safely administered following conventional61 or high-dose stereotactic radiotherapy,23 respectively. The combination of stereotactic radiotherapy followed by L19-IL2 is currently under evaluation in our Phase I trial (NCT02086721). To summarize, the available data show no indication of induction of excessive toxicity of radioimmunotherapy over immunotherapy alone. However, as data are mostly immature and limited, prudence remains imperative.90 Therefore, it is advised to test these combinations preferably within the context of a clinical trial.

CONCLUSION

The advent of immunotherapy is currently revolutionizing the field of oncology, where different drugs are used to stimulate different steps in a failing cancer immune response chain. Extensive pre-clinical data have shown that radiotherapy can synergize with these agents by broadening up the immune repertoire in T cells (vaccination effect), by attracting T cells to the irradiated site (homing effect) and by rendering irradiated cells more vulnerable towards T-cell-mediated cell kill (vulnerability effect). There are many open questions on how to integrate radiotherapy into an immune treatment in patients in the most optimal fashion; these questions are about optimal fractionation and dose, target volume, treatment technique, timing and safety. A plethora of clinical trials are currently ongoing investigating these radiotherapy–immune interactions in patients.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

PL is a member of the advisory board of DualTpharma. DDR is a member of the advisory board of Merck, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Genentech and Roche for which Maastro Foundation received honoraria.

FUNDING

PL received a research grant received by Philogen. Authors acknowledge financial support from ERC advanced grant (ERC-ADG-2015, n° 694812 - Hypoximmuno) and the European Program H2020 (ImmunoSABR - n° 733008).

Contributor Information

Evert J Van Limbergen, Email: evert.vanlimbergen@maastro.nl.

Dirk K De Ruysscher, Email: dirk.deruysscher@maastro.nl.

Veronica Olivo Pimentel, Email: v.olivopimentel@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Damiënne Marcus, Email: d.marcus@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Maaike Berbee, Email: maaike.berbee@maastro.nl.

Ann Hoeben, Email: ann.hoeben@mumc.n.

Nicolle Rekers, Email: nicolle.rekers@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Jan Theys, Email: jan.theys@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Ala Yaromina, Email: ala.yaromina@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Ludwig J Dubois, Email: ludwig.dubois@maastrichtuniversity.nl.

Philippe Lambin, Email: philippe.lambin@maastro.nl.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011; 144: 646–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart BW, Wild CP, eds. World cancer report. Lyon, France: WHO Press, World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, Hodgson B, Sharma RA. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2008; 8: 193–204. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. The molecular basis of cancer-cell behavior. Molecular biology of the cell. 5th edn. New York, NY: Garland Science; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 2013; 39: 1–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson EB, Livingstone AM. Cutting edge: CD4+ T cell-derived IL-2 is essential for help-dependent primary CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol 2008; 181: 7445–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenberger SP, Toes RE, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Melief CJ. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40-CD40L interactions. Nature 1998; 393: 480–3. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/31002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Miller JF, Heath WR. Induction of a CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte response by cross-priming requires cognate CD4+ T cell help. J Exp Med 1997; 186: 65–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.186.1.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 2003; 299: 1057–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1079490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 330–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ni904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills KH. Regulatory T cells: friend or foe in immunity to infection? Nat Rev Immunol 2004; 4: 841–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blank CU, Haanen JB, Ribas A, Schumacher TN. Cancer immunology. The “cancer immunogram”. Science 2016; 352: 658–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slone HB, Milas L. Effect of host immuno capability on radiocurability and subsequent transplantability of a murine fobrosarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 1979; 63: 1229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spanos WC, Nowicki P, Lee DW, Hoover A, Hostager B, Gupta A, et al. Immune response during therapy with cisplatin or radiation for human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 135: 1137–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2009.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynders K, Illidge T, Siva S, Chang JY, De Ruysscher D. The abscopal effect of local radiotherapy: using immunotherapy to make a rare event clinically relevant. Cancer Treat Rev 2015; 41: 503–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Formenti SC, Demaria S. Systemic effects of local radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10: 718–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70082-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 711–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1003466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science 2013; 342: 1432–3. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.342.6165.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, Yamada Y, Yuan J, Kitano S, et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 925–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1112824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiniker SM, Chen DS, Reddy S, Chang DT, Jones JC, Mollick JA, et al. A systemic complete response of metastatic melanoma to local radiation and immunotherapy. Transl Oncol 2012; 5: 404–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1593/tlo.12280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N, Dewyngaert JK, Babb JS, Formenti SC, et al. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 5379–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-09-0265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demaria S, Kawashima N, Yang AM, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Allison JP, et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11(2 Pt 1): 728–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seung SK, Curti BD, Crittenden M, Walker E, Coffey T, Siebert JC, et al. Phase 1 study of stereotactic body radiotherapy and interleukin-2—tumor and immunological responses. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 137ra74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, Dummer R, Wolchok JD, Schmidt H, et al. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1845–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1611299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park K, Ciardiello F, von Pawel J, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 255–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32517-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1823–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 1540–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1627–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 123–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1504627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1803–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1510665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Jr, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1856–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1602252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellmunt J, De Wit R, Vaugh DJ. Keynote-45: open-label, phase III study of pembrolizumab versus investigator's choice of paclitaxel, docetaxel, or vinflunine for previously untreated advanced urothelial cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2016; 4(Suppl. 2): 2. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 411–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1001294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fong L, Small EJ. Anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 antibody: the first in an emerging class of immunomodulatory antibodies for cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 5275–83. doi: https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2008.17.8954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okazaki T, Chikuma S, Iwai Y, Fagarasan S, Honjo T. A rheostat for immune responses: the unique properties of PD-1 and their advantages for clinical application. Nat Immunol 2013; 14: 1212–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.2762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernstein MB, Krishnan S, Hodge JW, Chang JY. Immunotherapy and stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (ISABR): a curative approach? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016; 13: 516–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demaria S, Golden EB, Formenti SC. Role of local radiation therapy in cancer immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol 2015; 1: 1325–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gameiro SR, Jammeh ML, Wattenberg MM, Tsang KY, Ferrone S, Hodge JW. Radiation-induced immunogenic modulation of tumor enhances antigen processing and calreticulin exposure, resulting in enhanced T-cell killing. Oncotarget 2014; 5: 403–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galluzzi L, Buque A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2017; 17: 97–111. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrera FG, Bourhis J, Coukos G. Radiotherapy combination opportunities leveraging immunity for the next oncology practice. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 65–85. doi: https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lugade AA, Sorensen EW, Gerber SA, Moran JP, Frelinger JG, Lord EM. Radiation-induced IFN-gamma production within the tumor microenvironment influences antitumor immunity. J Immunol 2008; 180: 3132–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Camphausen K, Liu K, Scott T, Coleman CN, et al. Irradiation of tumor cells up-regulates Fas and enhances CTL lytic activity and CTL adoptive immunotherapy. J Immunol 2003; 170: 6338–47. doi: https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chakraborty M, Abrams SI, Coleman CN, Camphausen K, Schlom J, Hodge JW. External beam radiation of tumors alters phenotype of tumor cells to render them susceptible to vaccine-mediated T-cell killing. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 4328–37. doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garnett CT, Palena C, Chakraborty M, Tsang KY, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Sublethal irradiation of human tumor cells modulates phenotype resulting in enhanced killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 7985–94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA, Groothuis TA, Chakraborty M, Wansley EK, et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2006; 203: 1259–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20052494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belcaid Z, Phallen JA, Zeng J, See AP, Mathios D, Gottschalk C, et al. Focal radiation therapy combined with 4-1BB activation and CTLA-4 blockade yields long-term survival and a protective antigen-specific memory response in a murine glioma model. PLoS One 2014; 9: e101764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu L, Wu MO, De la Maza L, Yun Z, Yu J, Zhao Y, et al. Targeting the inhibitory receptor CTLA-4 on T cells increased abscopal effects in murine mesothelioma model. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 12468–80. doi: https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.3487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Twyman-Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A, Rengan R, Pauken KE, Stelekati E, et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature 2015; 520: 373–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshimoto Y, Suzuki Y, Mimura K, Ando K, Oike T, Sato H, et al. Radiotherapy-induced anti-tumor immunity contributes to the therapeutic efficacy of irradiation and can be augmented by CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model. PLoS One 2014; 9: e92572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koller KM, Mackley HB, Liu J, Wagner H, Talamo G, Schell TD, et al. Improved survival and complete response rates in patients with advanced melanoma treated with concurrent ipilimumab and radiotherapy versus ipilimumab alone. Cancer Biol Ther 2017; 18: 36–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15384047.2016.1264543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herter-Sprie GS, Koyama S, Korideck H, Hai J, Deng J, Li YY, et al. Synergy of radiotherapy and PD-1 blockade in Kras-mutant lung cancer. JCI Insight 2016; 1: e87415. doi: https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.87415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dovedi SJ, Adlard AL, Lipowska-Bhalla G, McKenna C, Jones S, Cheadle EJ, et al. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Res 2014; 74: 5458–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-14-1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, Beckett M, Darga T, Weichselbaum RR, et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 687–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1172/jci67313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeng J, See AP, Phallen J, Jackson CM, Belcaid Z, Ruzevick J, et al. Anti-PD-1 blockade and stereotactic radiation produce long-term survival in mice with intracranial gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013; 86: 343–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharabi AB, Nirschl CJ, Kochel CM, Nirschl TR, Francica BJ, Velarde E, et al. Stereotactic radiation therapy augments antigen-specific PD-1-mediated antitumor immune responses via cross-presentation of tumor antigen. Cancer Immunol Res 2015; 3: 345–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.cir-14-0196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park SS, Dong H, Liu X, Harrington SM, Krco CJ, Grams MP, et al. PD-1 restrains radiotherapy-induced abscopal effect. Cancer Immunol Res 2015; 3: 610–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.cir-14-0138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yasuda K, Nirei T, Tsuno NH, Nagawa H, Kitayama J. Intratumoral injection of interleukin-2 augments the local and abscopal effects of radiotherapy in murine rectal cancer. Cancer Sci 2011; 102: 1257–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01940.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwartz RN, Stover L, Dutcher J. Managing toxicities of high-dose interleukin-2. Oncology (Williston Park) 2002; 16(Suppl. 13): 11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neri D, Sondel PM. Immunocytokines for cancer treatment: past, present and future. Curr Opin Immunol 2016; 40: 96–102. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rekers NH, Zegers CM, Yaromina A, Lieuwes NG, Biemans R, Senden-Gijsbers BL, et al. Combination of radiotherapy with the immunocytokine L19-IL2: additive effect in a NK cell dependent tumour model. Radiother Oncol 2015; 116: 438–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2015.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van den Heuvel MM, Verheij M, Boshuizen R, Belderbos J, Dingemans AM, De Ruysscher D, et al. NHS-IL2 combined with radiotherapy: preclinical rationale and phase Ib trial results in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer following first-line chemotherapy. J Transl Med 2015; 13: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zegers CM, Rekers NH, Quaden DH, Lieuwes NG, Yaromina A, Germeraad WT, et al. Radiotherapy combined with the immunocytokine L19-IL2 provides long-lasting antitumor effects. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 1151–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-14-2676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rekers NH, Zegers CM, Germeraad WT, Dubois L, Lambin P. Long-lasting antitumor effects provided by radiotherapy combined with the immunocytokine L19-IL2. Oncoimmunology 2015; 4: e1021541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang J, Demaria S, Formenti S. Current clinical trials testing the combination of immunotherapy with radiotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2016; 4: 51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-016-0156-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mehta S, Illidge T, Choudhury A. Immunotherapy with radiotherapy in urological malignancies. Curr Opin Urol 2016; 26: 514–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/mou.0000000000000335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marshall R, Popple A, Kordbacheh T, Honeychurch J, Faivre-Finn C, Illidge T. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer—an unheralded opportunity? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2017; 29: 207–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gandhi SJ, Minn AJ, Vonderheide RH, Wherry EJ, Hahn SM, Maity A. Awakening the immune system with radiation: optimal dose and fractionation. Cancer Lett 2015; 368: 185–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schaue D, Ratikan JA, Iwamoto KS, McBride WH. Maximizing tumor immunity with fractionated radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 83: 1306–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chandra RA, Wilhite TJ, Balboni TA, Alexander BM, Spektor A, Ott PA, et al. A systematic evaluation of abscopal responses following radiotherapy in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab. Oncoimmunology 2015; 4: e1046028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garg AD, Galluzzi L, Apetoh L, Baert T, Birge RB, Bravo-San Pedro JM, et al. Molecular and translational classifications of DAMPs in immunogenic cell death. Front Immunol 2015; 6: 588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bentzen AK, Marquard AM, Lyngaa R, Saini SK, Ramskov S, Donia M, et al. Large-scale detection of antigen-specific T cells using peptide-MHC-I multimers labeled with DNA barcodes. Nat Biotechnol 2016; 34: 1037–45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teoh M, Clark CH, Wood K, Whitaker S, Nisbet A. Volumetric modulated arc therapy: a review of current literature and clinical use in practice. Br J Radiol 2011; 84: 967–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/22373346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakamura N, Kusunoki Y, Akiyama M. Radiosensitivity of CD4 or CD8 positive human T-lymphocytes by an in vitro colony formation assay. Radiat Res 1990; 123: 224–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mandl JN, Liou R, Klauschen F, Vrisekoop N, Monteiro JP, Yates AJ, et al. Quantification of lymph node transit times reveals differences in antigen surveillance strategies of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109: 18036–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211717109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bousso P, Robey E. Dynamics of CD8+ T cell priming by dendritic cells in intact lymph nodes. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 579–85. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ni928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Obst R. The timing of T cell priming and cycling. Front Immunol 2015; 6: 563. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Henrickson SE, Perro M, Loughhead SM, Senman B, Stutte S, Quigley M, et al. Antigen availability determines CD8(+) T cell-dendritic cell interaction kinetics and memory fate decisions. Immunity 2013; 39: 496–507. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Poleszczuk JT, Luddy KA, Prokopiou S, Robertson-Tessi M, Moros EG, Fishman M, et al. Abscopal benefits of localized radiotherapy depend on activated T-cell trafficking and distribution between metastatic lesions. Cancer Res 2016; 76: 1009–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Demaria S, Formenti SC. Can abscopal effects of local radiotherapy be predicted by modeling T cell trafficking? J Immunother Cancer 2016; 4: 29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-016-0133-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Young KH, Baird JR, Savage T, Cottam B, Friedman D, Bambina S, et al. Optimizing timing of immunotherapy improves control of tumors by hypofractionated radiation therapy. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0157164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schoenhals JE, Seyedin SN, Tang C, Cortez MA, Niknam S, Tsouko E, et al. Preclinical rationale and clinical considerations for radiotherapy plus immunotherapy: going beyond local control. Cancer J 2016; 22: 130–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/ppo.0000000000000181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Simpson TR, Li F, Montalvo-Ortiz W, Sepulveda MA, Bergerhoff K, Arce F, et al. Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J Exp Med 2013; 210: 1695–710. doi: https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20130579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dovedi SJ, Illidge TM. The antitumor immune response generated by fractionated radiation therapy may be limited by tumor cell adaptive resistance and can be circumvented by PD-L1 blockade. Oncoimmunology 2015; 4: e1016709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Noman MZ, Hasmim M, Messai Y, Terry S, Kieda C, Janji B, et al. Hypoxia: a key player in antitumor immune response. A review in the theme: cellular responses to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2015; 309: C569–79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00207.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Overgaard J. Hypoxic radiosensitization: adored and ignored. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 4066–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.12.7878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Peeters SG, Zegers CM, Lieuwes NG, van Elmpt W, Eriksson J, van Dongen GA, et al. A comparative study of the hypoxia PET tracers [(18)F]HX4, [(18)F]FAZA, and [(18)F]FMISO in a preclinical tumor model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015; 91: 351–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.09.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wack LJ, Monnich D, van Elmpt W, Zegers CM, Troost EG, Zips D, et al. Comparison of [18F]-FMISO, [18F]-FAZA and [18F]-HX4 for PET imaging of hypoxia—a simulation study. Acta Oncol 2015; 54: 1370–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186x.2015.1067721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dubois LJ, Niemans R, van Kuijk SJ, Panth KM, Parvathaneni NK, Peeters SG, et al. New ways to image and target tumour hypoxia and its molecular responses. Radiother Oncol 2015; 116: 352–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilson WR, Hay MP. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2011; 11: 393–410. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Antoni D, Bockel S, Deutsch E, Mornex F. Radiotherapy and targeted therapy/immunotherapy. Cancer Radiother 2016; 20: 434–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canrad.2016.07.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kroeze SG, Fritz C, Hoyer M, Lo SS, Ricardi U, Sahgal A, et al. Toxicity of concurrent stereotactic radiotherapy and targeted therapy or immunotherapy: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2017; 53: 25–37. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Levy A, Massard C, Soria JC, Deutsch E. Concurrent irradiation with the anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 immune checkpoint blocker durvalumab: single centre subset analysis from a phase 1/2 trial. Eur J Cancer 2016; 68: 156–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kwon ED, Drake CG, Scher HI, Fizazi K, Bossi A, van den Eertwegh AJ, et al. Ipilimumab versus placebo after radiotherapy in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that had progressed after docetaxel chemotherapy (CA184-043): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 700–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70189-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]