Significance

Observations at different times during extensional faulting cycles show dramatically different deformation. Available coseismic and postseismic observations bear little resemblance to the topography of rifted zones, yet this topography is the end result of repeated earthquakes. During earthquakes, and during periods decades later, there is little evidence of rift flank, or range-front deformation, yet strong bending and uplift of these features ultimately define extended terranes. Numerical modeling incorporating gravity and the principle of isostatic balance predicts strong vertical forces during the first decade after a significant earthquake that are preferentially focused beneath range fronts. We conclude these forces are responsible for characteristic rift topography. This hypothesis is testable with intermediate period geodetic observations that are rare for extensional earthquakes.

Keywords: rifting, finite-element modeling, earthquakes, crustal deformation, Basin and Range

Abstract

In the Basin and Range extensional province of the western United States, coseismic offsets, under the influence of gravity, display predominantly subsidence of the basin side (fault hanging wall), with comparatively little or no uplift of the mountainside (fault footwall). A few decades later, geodetic measurements [GPS and interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR)] show broad (∼100 km) aseismic uplift symmetrically spanning the fault zone. Finally, after millions of years and hundreds of fault offsets, the mountain blocks display large uplift and tilting over a breadth of only about 10 km. These sparse but robust observations pose a problem in that the coesismic uplifts of the footwall are small and inadequate to raise the mountain blocks. To address this paradox we develop finite-element models subjected to extensional and gravitational forces to study time-varying deformation associated with normal faulting. Stretching the model under gravity demonstrates that asymmetric slip via collapse of the hanging wall is a natural consequence of coseismic deformation. Focused flow in the upper mantle imposed by deformation of the lower crust localizes uplift, which is predicted to take place within one to two decades after each large earthquake. Thus, the best-preserved topographic signature of earthquakes is expected to occur early in the postseismic period.

With its repeating series of parallel ranges rising sharply above deep valleys, the Basin and Range province is one of Earth’s most distinctive terranes (Fig. 1). However, this active ∼10–15-Ma-old (1) landscape bears little resemblance to present-day measures of deformation. During earthquakes, the basins drop (2), but the ranges show little or no rise. Satellite ranging [GPS, interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR)] shows areas of broad uplift and subsidence that do not directly correspond with topography. We use numerical modeling techniques constrained with observations over three periods: coseismic (deformation during earthquakes), postseismic (deformation after earthquakes), and multiseismic (topography resulting from repeated earthquakes). We further constrain our models with the concept of isostasy, the gravitational equilibrium that must ultimately result from any vertical change to the Earth’s surface. The addition of this constraint allows us to produce a single unifying model that explains variations in fault-related deformation over time.

Fig. 1.

Characteristic basin and range topography, with narrow chains of ranges interspersed by basins. (Upper, Inset) Cross-section model of the Warner Range and its bent range front (3, 35). (Lower) The range blocks are bent as a result of repeated faulting along their fronts rather than being tilted. In this example, a single block is faced on either side by normal faults, has no significant internal faulting, and both sides are bent upward (36).

Observations

The Basin and Range province topography was built in response to broad crustal extension between the Sierra Nevada ranges to the west, and the Colorado Plateau to the east. Repeated earthquakes on dipping (45°–60°) faults offset crystalline bedrock ranges (fault footwalls) against basins filled with sediment (fault hanging walls) (Fig. 1), meaning that roughly half of the resulting deformation is vertical. Cumulative slip on these faults (faults that accommodate extension are called normal faults) can be up to ∼10 km in magnitude, and is the result of many hundreds of earthquakes. We thus term this deformation as multiseismic. Observations and modeling results show mountain blocks that are tilted or bent upward over a width of about 10 km (Fig. 1). Wider mountain blocks (∼20 km) display more bending, which requires permanent rock deformation, probably in part expressed by myriad minor faults and joints (3, 4).

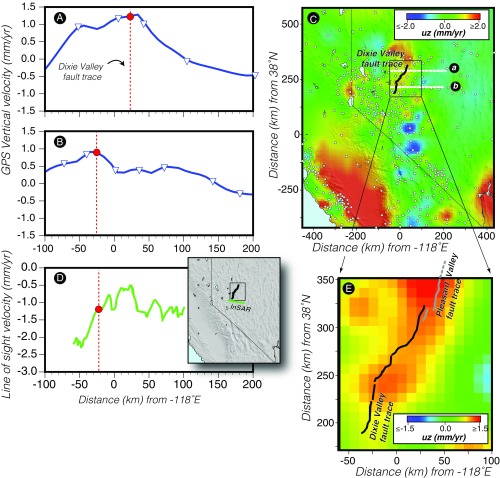

Deformation measured over the span of decades (postseismic period) using remote sensing methods shows a very different pattern than the topography. Combined GPS and InSAR observations (5, 6) show broad areas of uplift and subsidence in the vicinity of a chain of magnitude (M) ∼ 7 earthquakes that struck central Nevada between 1915 and 1954 (7, 8). The areal extent of vertical deformation observed over this period spans across both basins and ranges and can be 100–200 km in width (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Geodetic measures of central Basin and Range Province uplift during the past two decades (5, 6). Uplift tends to be symmetric around relatively recently ruptured faults (1954 in this case), which differs from the sharp topographic signal marked by range-front faults (Fig. 1). A and B show west-to-east uplift profiles vs. distance along the transects marked a and b on the map panel in C. An InSAR profile is also shown in D, and a close-up contour map around the Dixie Valley fault is shown in E.

However, a different deformation mode is observed during individual earthquakes (coseismic period). Highly concentrated subsidence (10–15 km wide) of the basins is observed (9–13) whereas the ranges are stable, or rise very slightly (Fig. 3). These observations are based on leveling surveys recorded in Nevada before and after the 1954 M = 7.2 Fairview Peak and M = 6.5 Dixie Valley earthquakes, and in Idaho before and after the 1983 M = 6.9 Borah Peak earthquake. Clearly, the evolution from seismic slip on faults to the final topographic signature of crustal extension passes through different temporal phases. We develop a physical hypothesis based on isostasy and crustal lithospheric rheology, and test it using finite-element models.

Fig. 3.

Observations of coseismic deformation. In these three examples where there exist pre- and postearthquake leveling lines (10, 12), it is evident that the coseismic vertical deformation consists almost entirely of subsidence of the hanging walls (basins). Virtually no range uplift is observed, which is counter to the bent and elevated ranges observed in the topography (Fig. 1).

Conceptual Model

Conceptually, the process begins with elastic rebound, which in normal faulting requires a horizontal withdrawal of mass from the fault zone and thus an unloading of the footwall (14, 15) (Fig. 4). Isostatic forces and inflow of lower crust and upper mantle then cause a postseismic upward-directed bulging, focused initially near the fault zone and later, after several decades, becomes broader. The basin side is repeatedly dropped with each large earthquake.

Fig. 4.

Conceptual model that describes faulting of an elastic crust under extension floating in a denser, ductile substrate. (A) A downward-directed gravitational load combined with expanding lateral boundaries causes elastic stretching of the brittle upper crust in an extending tectonic setting. The net density is decreased in any fixed reference crustal section as a result. (B) Frictional resistance on a normal fault is overcome and an earthquake occurs. That rupture concentrates the previously distributed density decrease into the volume that contains the fault. (C) The hanging wall (basin side) collapses during the earthquake, and the volume containing the fault tries to float upward because it is suddenly less dense. (D) Ductile rock flows in beneath the faulted region as a new isostatic balance is achieved, and the faulted region bulges upward.

Isostasy in the Earth’s crust means that its shallowest elastic parts float in the denser, hotter, and more ductile substrate below. These floating masses find their equilibrium heights over time, with that duration depending on the rheology of the substrate. Basic isostatic calculations, wherein the sudden mass change after an earthquake (1-m slip event) is treated in theoretical floating vertical columns, predict an upward directed force of ∼70 MPa applied across the narrow zone of postfaulting mass change (Fig. 4). Additionally, stress transferred from primary earthquake slip (16) onto the continuation of a shear zone into the deep crust can cause afterslip and additional deformation (17).

A distinction regarding continental dip–slip faults that cause elevation changes emerges because of isostasy. Faults form and fail as a result of differences in the magnitudes and directions of the principal stresses in the crust, typically at a frictionally dependent angle inclined 30°–60° to the least compressive stress direction (18). In compressional (thrust) faulting, the least stress is vertically inclined, and the greatest stress is oriented horizontally, whereas strike–slip faulting regimes have horizontally directed greatest and least stresses. In extensional settings, the least stress is oriented horizontally, and greatest stress is the vertical gravitational load. This means that faults that change the elevation profile also create postearthquake vertically directed isostatic forces, which add stress to the fault that just failed. Upward-directed isostatic forces result from unloading of the fault zone in extensional settings and downward-directed isostatic forces result from loading of the fault zone in compressional settings (19). Both actions thus increase the differential stresses that lead to fault failure. Isostatic loading is expected to be more rapid and important in extensional settings because higher heat flow, thinner crust, and increased lower crust and upper mantle mobility (20) enable a more immediate response than in convergent terranes where a cooler, more rigid rheology can resist isostatic forces.

Isostatic reloading of faults has energy balance implications because dip–slip faults are stressed both by tectonic plate motions and by the act of faulting itself. The additional isostatic stress must be shed as aftershocks, postseismic slip, by increasing magnitudes of subsequent earthquakes, or a progressive decrease in recurrence intervals. Our conceptual model therefore hypothesizes that additional isostatic stressing acting on normal faults is responsible for the signature deformation that characterizes the Bain and Range province and other rift zones.

Numerical Model

A numerical model that is allowed to freely respond to forces that represent our best understanding of those acting in the Earth’s crust can yield revealing results provided the solutions are not overly guided, or overly sensitive to parameter choices. Gravity is the driving force acting on the crust, and the primary feature of extensional terranes is that their boundaries can expand laterally, enabling the crust to collapse under its weight. We develop a simple finite-element model under these conditions (21), with layers based on physical properties of rock subjected to gravity, and with boundaries that expand laterally at observed rates (22). The model has three layers (Fig. 5): a brittle, breakable upper-crustal layer (15 km thick), a 15-km-thick ductile lower crustal layer where strain is accommodated primarily by flow, and a 170-km-thick upper mantle layer that is deep enough to prevent the bottom model boundary from affecting results. A breakable upper-crustal layer is necessary to best replicate the long-term plastic deformation of a fractured and faulted shallow crust (21). We find the best fit to geodetic observations if the lower-crustal layer is stronger than the upper mantle, as have many other Basin and Range studies (6, 23–30). We embed a 45° dipping normal fault through the upper crust, and permit shear on a deeper extension of the fault into the lower crust.

Fig. 5.

Numerical model of normal fault behavior (21). (A) The model consists of three layers: a 15-km-thick elastic but breakable upper crust, a 15-km-thick ductile lower-crustal layer, and a ductile upper mantle thick enough (170 km) that its boundaries do not affect the solution. A 45° dipping normal fault is embedded in the upper crust in the middle of the model that continues as a shear zone into the lower crust. The model can collapse under gravity when its edges are allowed to expand. (B) The model matches observed coseismic subsidence of the fault hanging wall, and stability of the fault foot wall. (C) In a subsequent test, a 1-m slip event on the fault is imposed, which is equivalent to an M ∼ 7 earthquake. The fault is immediately locked, and the postseismic isostatic effects are calculated for a period 10 y after the earthquake. Strong uplift forces beneath the fault footwall are predicted. Localized variability in vector directions in the upper crust is caused by element fracture. (D) By 60 y after the earthquake (∼present-day observation period after the 1954 Nevada earthquake series), the model predicts a broader uplift effect that spans ∼100 km either side of the fault, and that (E) agrees (red dots show modeled uplift rates) with GPS observations (blue dots with measurement uncertainties plotted as error bars). Outlier points are the result of plastic element fracture in the upper crust. (F) A model of long-term extensional faulting is shown, where the fault is allowed to slip continuously, simulating many earthquakes. This results in the uplifted bent range fronts that characterize the Basin and Range province.

We can use this model to study effects of faulting over the coseismic, postseismic, and multiseismic time frames. The first simulation has a model with a locked normal fault, gravitational load, and expanding boundaries. After extensional stresses are allowed to build, we release the fault, which slips, and the footwall collapses as observed following real earthquakes (Fig. 5B). The second simulation is similar to the first except that the fault is prescribed to slip 1 m, simulating an M ∼ 7 earthquake. The fault is then locked and the postseismic response of the lithosphere to fault slip and isostasy is tracked over time (Fig. 5 C–E). Predictions from the model include an early phase of asymmetric uplift focused primarily under the footwall (Fig. 5C) that diminishes with time. By 60 y after faulting, which is equivalent to the present-day observation period for GPS and InSAR (5, 6) after the 1954 central Nevada earthquakes, a broad upwarp is predicted (Fig. 5D) that matches observations (Fig. 5E). In the final simulation, we allow the fault to slip continuously, mimicking repeated earthquakes over many millions of years. This test replicates the distinctive rifting signature of uplifted and bent ranges (Fig. 5F). A simple finite-element model can thus reproduce deformation observed on coseismic, postseismic, and multiseismic time scales, but a mystery still persists.

Summary and a Challenge

When in the seismic cycle do isostatic forces express themselves? Our numerical model predicts that the strongest uplift should occur beneath the ranges almost immediately after faulting, with a short (∼10-y) delay required for ductile rocks to begin flowing. The early postseismic uplift is predicted, but to the authors’ knowledge has not yet been observed. Geodetic uplift observations do not cover this period in the Basin and Range province, but instead verify the upwarping that affects a wider region than an individual faulted range front.

Our long-term simulations show that, to get the narrow basin–range topography and bent ranges, the isostatically derived topography of narrow basins and uplifted ranges must occur entirely by slip on faults. However, these simulations cannot pinpoint when in the seismic cycle isostatic forces are expressed as fault slip. The reason for this is that we cannot know the frictional locking behavior of the ruptured faults over time. If the fault locks up immediately after the earthquake and stays locked until the next one, then both the hanging wall and footwall will be uplifted as a result of isostasy. An energy-balance implication of this scenario is that each subsequent earthquake would either have to be slightly larger than the prior, or come sooner. This is because tectonic stressing is essentially monotonic, while each isostatic response would compound stress accumulation. However, this scenario of converting gravitational potential energy only into earthquakes on a single fault is likely an oversimplification given the many strain modes in the Earth.

Deformation from isostatic stress may occur as postearthquake aseismic creep, or as aftershocks. Postearthquake creep has been observed in extensional settings (31), but more observations are needed to know if this is a general occurrence. A global study finds that the earthquake magnitude–frequency distribution on normal faults differs from other modes in a statistically significant way, with an increased rate of smaller earthquakes relative to larger (32). One interpretation of this feature is that normal fault earthquake rupture surfaces are smaller than other earthquake modes (15). Another interpretation is that there are more aftershocks (which tend to be smaller events) associated with normal fault mainshocks. Increased aftershock rates could be a response to isostatic forces, and may help to shape Basin and Range topography. Evidence from paleoseismology in the central Italy extensional regime suggests that large and moderate earthquakes reruptured the same normal fault system during a 15-d period in 1703 (33). A similar rerupturing occurred within the same fault system during the 2016 Central Italy earthquake sequence (34). In the authors’ opinion, these questions can be resolved by a rapid geodetic deployment following the next large normal fault earthquake, hence the challenge.

Acknowledgments

Bill Hammond and one anonymous reviewer provided constructive and helpful comments.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Colgan JP, Dumitru TA, Miller EL. Diachroneity of Basin and Range extension and Yellowstone hotspot volcanism in northwestern Nevada. Geology. 2004;32:121–124. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martel SJ, Stock GM, Ito G. Mechanics of relative and absolute displacements across normal faults, and implications for uplift and subsidence along the eastern escarpment of the Sierra Nevada, California. Geosphere. 2014;10:243–263. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colgan JP, Shuster DL, Reiners PW. Two-phase Neogene extension in the northwestern Basin and Range recorded in a single thermochronology sample. Geology. 2008;36:631–634. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compton RR. Analysis of Pliocene-Pleistocene deformation and stresses in northern Santa Lucia Range, California. Bull Geol Soc Am. 1966;77:1361–1380. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammond WC, Blewitt G, Li Z, Plag H-P, Kreemer C. Contemporary uplift of the Sierra Nevada, western United States, from GPS and InSAR measurements. Geology. 2012;40:667–670. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gourmelen N, Amelung F. Postseismic mantle relaxation in the Central Nevada Seismic Belt. Science. 2005;310:1473–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.1119798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doser DI. Earthquake processes in the Rainbow Mountain-Fairview Peak-Dixie Valley, Nevada region 1954-1959. J Geophys Res. 1986;91:12572–12586. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doser DI. Source parameters of earthquakes in the Nevada Seismic Zone, 1915-1943. J Geophys Res. 1988;93:15001–15015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitten CA. Geodetic measurements in the Dixie Valley area. Bull Seismol Soc Am. 1957;47:321–325. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meister LJ, Burford RO, Thompson GA, Kovach RL. Surface strain changes and strain energy release in the Dixie Valley-Fairview Peak area, Nevada. J Geophys Res. 1968;73:5981–5994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koseluk RA, Bischke RE. An elastic rebound model for normal fault earthquakes. J Geophys Res. 1981;86:1081–1090. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein RS, Barrientos SE. Planar high-angle faulting in the Basin and Range: Geodetic analysis of the 1983 Borah Peak, Idaho, earthquake. J Geophys Res. 1985;90:11355–11366. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodgkinson KM, Stein RS, Marshall G. Geometry of the 1954 Fairview Peak-Dixie Valley earthquake sequence from a joint inversion of leveling and triangulation data. J Geophys Res. 1996;101:25437–25457. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vening Meinesz FA. Les graben africains, resultat de compression ou de tension dans la croute terrestre? Inst R Colon Belge, Bull Seances. 1950;21:539–552. French. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doglioni C, Carminati E, Petricca P, Riguzzi F. Normal fault earthquakes or graviquakes. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12110. doi: 10.1038/srep12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein RS. The role of stress transfer in earthquake occurrence. Nature. 1999;402:605–609. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freed AM. Earthquake triggering by static, dynamic, and postseismic stress transfer. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2005;33:335–367. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson EM. The Dynamics of Faulting and Dyke Formation. Oliver and Boyd; Edinburgh: 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogfjord S, Langston CA. The Meckering earthquake of 14 October 1968: A possible downward propagating rupture. Bull Seismol Soc Am. 1987;77:1558–1578. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusznir NJ, Park RG. Continental lithosphere strength: The critical role of lower crustal deformation. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ. 1986;24:79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson GA, Parsons T. Vertical deformation associated with normal fault systems evolved over coseismic, postseismic, and multiseismic periods. J Geophys Res. 2016;121:2153–2173. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond WC, Blewitt G, Kreemer C. Steady contemporary deformation of the central Basin and Range Province, western United States. J Geophys Res. 2014;119:5235–5253. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollitz FF, Peltzer G, Bürgmann R. Mobility of continental mantle: Evidence from postseismic geodetic observations following the 1992 Landers earthquake. J Geophys Res. 2000;105:8035–8054. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wernicke BP, Friedrich AM, Niemi NA, Bennett RA, Davis JL. Dynamics of plate boundary fault systems from Basin and Range Geodetic Network (BARGEN) and geologic data. GSA Today. 2000;10:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hetland EA, Hager BH. Postseismic relaxation across the Central Nevada Seismic Belt. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:2394. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammond WC, Thatcher W. Contemporary tectonic deformation of the Basin and Range province, western United States: 10 years of observation with the Global Positioning System. J Geophys Res. 2004;109:B08403. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freed AM, Bürgmann R, Herring T. Far-reaching transient motions after Mojave earthquakes require broad mantle flow beneath a strong crust. Geophys Res Lett. 2007;34:L19302. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bürgmann R, Dresen G. Rheology of the lower crust and upper mantle: Evidence from rock mechanics, geodesy, and field observations. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2008;36:531–567. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammond WC, Kreemer C, Blewitt G. Geodetic constraints on contemporary deformation in the northern Walker Lane: 3. Central Nevada seismic belt postseismic relaxation. Spec Pap Geol Soc Am. 2009;447:33–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang W-L, Smith RB, Puskas CM. Effects of lithospheric viscoelastic relaxation on the contemporary deformation following the 1959 Mw 7.3 Hebgen Lake, Montana, earthquake and other areas of the intermountain seismic belt. Geochem Geophys Geosyst. 2013;14:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riva REM, et al. Viscoelastic relaxation and long-lasting after-slip following the 1997 Umbria-Marche (Central Italy) earthquakes. Geophys J Int. 2007;169:534–546. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schorlemmer D, Wiemer S, Wyss M. Variations in earthquake-size distribution across different stress regimes. Nature. 2005;437:539–542. doi: 10.1038/nature04094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galli P, Galadini F, Calzoni F. Surface faulting in Norcia (central Italy): A paleoseismological perspective. Tectonophysics. 2005;403:117–130. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiaraluce L, et al. The 2016 Central Italy seismic sequence: A first look at the mainshocks, aftershocks, and source models. Seismol Res Lett. 2017;88:757–771. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duffield WA, Weldin RD. 1976. Mineral Resources of the South Warner Wilderness, Modoc County, California, US Geological Survey Bulletin (United States Government Printing Office, Washington, DC), Vol B1385, p 31.

- 36.Van Buer N. 2012. Preliminary Geologic Map of the Sahwave and Nightingale Ranges, Churchill, Pershing, and Washoe Counties, Nevada, Open File Report 12-2 (Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, Reno, NV), p 12.