Significance

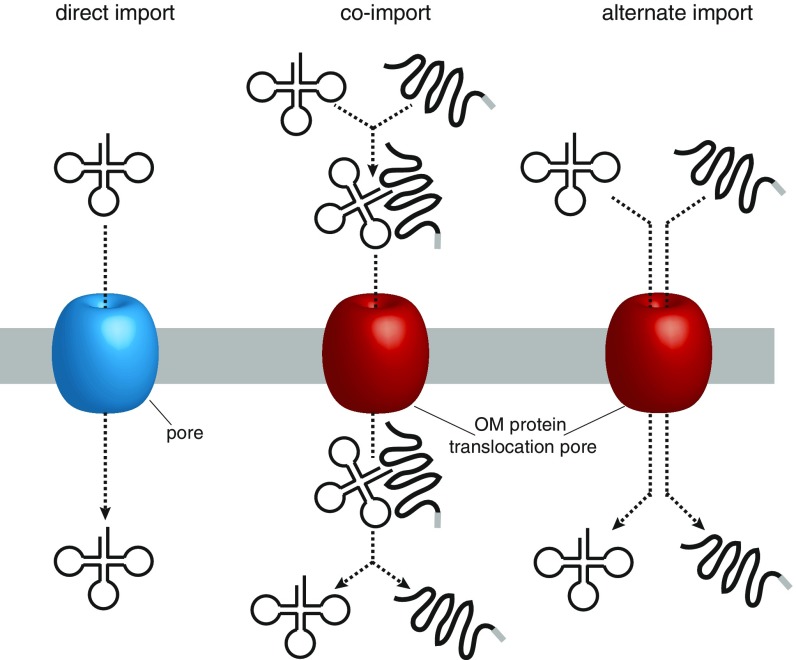

In most eukaryotes mitochondrial function requires not only import of proteins but also import of at least some tRNAs. Trypanosomes are extreme in that they lack mitochondrial tRNA genes, and therefore must import all of their mitochondrial tRNAs from the cytosol. Here we show that in trypanosomes both proteins and tRNAs use the same β-barrel protein pore to be translocated across the mitochondrial outer membrane. Moreover, we show that tRNA import can be uncoupled from protein import. Based on these results, we propose the “alternate import model,” in which tRNAs use the same outer membrane import pore as proteins but are imported as naked molecules. The model combines features of the previously proposed “coimport” and “direct import” models.

Keywords: mitochondrial tRNA import, mitochondrial protein import, trypanosomes, mitochondrial outer membrane, RNA

Abstract

Mitochondrial tRNA import is widespread, but the mechanism by which tRNAs are imported remains largely unknown. The mitochondrion of the parasitic protozoan Trypanosoma brucei lacks tRNA genes, and thus imports all tRNAs from the cytosol. Here we show that in T. brucei in vivo import of tRNAs requires four subunits of the mitochondrial outer membrane protein translocase but not the two receptor subunits, one of which is essential for protein import. The latter shows that it is possible to uncouple mitochondrial tRNA import from protein import. Ablation of the intermembrane space domain of the translocase subunit, archaic translocase of the outer membrane (ATOM)14, on the other hand, while not affecting the architecture of the translocase, impedes both protein and tRNA import. A protein import intermediate arrested in the translocation channel prevents both protein and tRNA import. In the presence of tRNA, blocking events of single-channel currents through the pore formed by recombinant ATOM40 were detected in electrophysiological recordings. These results indicate that both types of macromolecules use the same import channel across the outer membrane. However, while tRNA import depends on the core subunits of the protein import translocase, it does not require the protein import receptors, indicating that the two processes are not mechanistically linked.

Mitochondria derive from an endosymbiotic event between an archaeon and a bacterium ≈2 billion y ago (1–3). While mitochondria have maintained their own genome, it encodes only a small number of proteins (4, 5). Most mitochondrial proteins (>95%) are encoded in the nucleus, and after their synthesis in the cytosol imported into the organelle. Mitochondrial protein import has been studied in great detail and the machineries as well as the mechanisms of the process are well understood (6–9).

The mitochondrial genomes of many eukaryotes lack a complete set of tRNA genes and it has been shown that this lack is compensated for by import of a small fraction of the corresponding cytosolic tRNAs (10–12). Moreover, it has been postulated that even in organisms such as mammals, whose mitochondrial genome encodes a complete set of mitochondrial tRNAs, some apparently redundant tRNAs may be imported into mitochondria (13, 14). Furthermore, some studies indicate that mammals import the 5S rRNA (15–17) and the RNA subunit of RNase P (18–20). The function of these imported RNAs is unclear as the imported 5S rRNA has not been detected in the structure of the mammalian mitoribosome (21, 22), and a protein-only RNase P has been characterized in mammalian mitochondria (23).

In contrast to mitochondrial protein import, mitochondrial tRNA import is poorly understood. It has experimentally mainly been studied in yeast, plants, and trypanosomatids, and two general models have been proposed of how the process might work. In the first model, the tRNA is coimported with a mitochondrial precursor protein along the protein import pathway. This model applies to the tRNALys of yeast and has been elucidated in detail (24–26). In the second more vaguely defined model, which appears to apply to plants and protozoa (27–29), as well as to some tRNAs that appear to be imported into mammalian mitochondria (13, 14), tRNAs are directly imported independent of ongoing protein import and thus do not use the same translocation channel as proteins (11, 12).

The parasitic protozoan Trypanosoma brucei is an excellent system to study mitochondrial tRNA import. Unlike most other eukaryotes, its mitochondrial genome does not encode any tRNAs, indicating that all of its organellar tRNAs—more than 30 different species—must be imported from the cytosol in quantities sufficient to support mitochondrial translation (28–30).

The protein import machinery of the T. brucei mitochondrion has recently been characterized and was shown to be highly diverged compared with other eukaryotes (31). Thus, protein import across the outer membrane (OM) is mediated by the archaic translocase of the OM (ATOM), a complex consisting of six subunits (32, 33). [More recently TbLOK1, initially identified as a mitochondrial morphology protein, was also shown to be a component of the ATOM complex, raising the number of subunits to seven (34).] The core subunits of the ATOM complex include ATOM40 and ATOM14, which are remotely related to Tom40 and Tom22 of other eukaryotes, as well as ATOM12 and ATOM11, which are exclusively found in trypanosomatids (31). These core subunits are associated with the two receptors ATOM46 and ATOM69, which are unique to trypanosomatids. With the exception of ATOM46, which is required for growth at elevated temperature only, all ATOM subunits are essential. To elucidate whether tRNA import in T. brucei complies with the direct import or the coimport model, we investigated whether subunits of the OM protein translocase are required for the process and whether tRNA import is coupled to protein import. The results show that: (i) some but not all essential subunits of the OM protein translocase are required for tRNA import, (ii) that tRNAs and proteins use the same pore for import, and (iii) that tRNA import likely is not coupled to protein import.

Results

In Vivo Import of tRNAs Depends on ATOM Core Subunits.

Mitochondrial tRNA import in trypanosomatids has been studied using both in vivo (35–37) and in vitro assays (27, 38–41). However, even though it is known that in vivo import of tRNAs requires cytosolic factors (42), in vitro import has only been analyzed in the absence of cytosolic fractions. It therefore remains unclear to which extent these in vitro systems reflect the in vivo situation. To be sure to obtain physiologically meaningful results, we focused on an in vivo approach, which consisted of measuring tRNA steady-state levels in RNAi cell lines ablated for the individual ATOM components.

Inhibition of tRNA import will result in reduced steady-state levels of mitochondrial tRNAs. However, a possible confounding factor might be that in the absence of protein import, mitochondrial translation will eventually also be inhibited. If tRNAs are not used in translation they might be unstable, which would result in a decreased steady-state level even though tRNA import is not affected. Fig. S1 shows that this is not the case, as the steady-state levels of mitochondrial tRNAs is not affected in an RNAi cell line that is unable to synthesize mitochondrial proteins due to the absence of the mitochondrial translation elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) (43). This indicates that the steady-state levels of mitochondrial tRNAs are indeed a good proxy to estimate the efficiency of import.

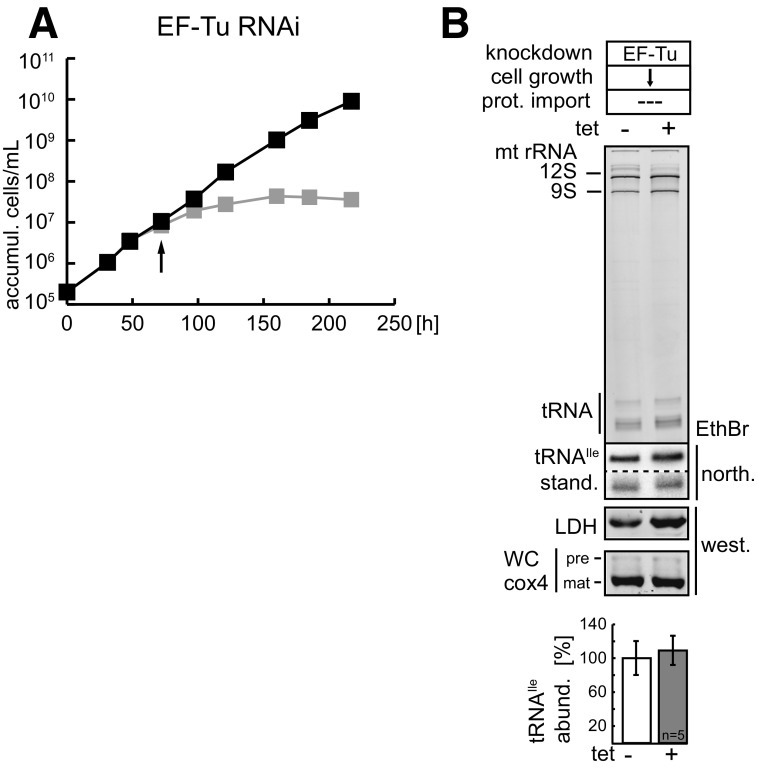

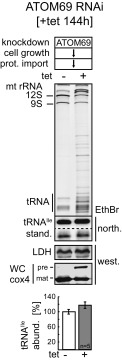

Fig. S1.

Ablation of EF-Tu does not affect mitochondrial tRNA import. (A) Growth curve of the procyclic form of the uninduced (black) and induced (gray) EF-Tu–RNAi cell line. The EF-Tu–RNAi cell line has been previously characterized (43). (B) RNAi-mediated ablation of EF-Tu impairs growth but not mitochondrial protein import. The EthBr gel shows mitochondrial RNA extracts separated on 8 M urea/10% polyacrylamide gels that were isolated from uninduced and induced cell lines (see arrow in growth curve, A). The positions of the 12S and 9S mitochondrial rRNAs and the tRNA region are indicated. The two panels below show the corresponding Northern blots probed either for tRNAIle or the short synthetic RNA molecule (stand.) that was used as an internal standard for the yield of the RNA preparation. The panel below the Northern blots shows an immunoblot of the same mitochondrial fractions probed for LDH. It serves as a quality control for the intactness and yield of the mitochondria present in the digitonin-extracted pellet fractions. The graph at the bottom shows the quantification of the abundance of the tRNAIle normalized to the levels of the short synthetic RNA molecule. The mean of five replicates is shown. Bar, average deviation. accumul., accumulation; north., Northern blot; prot., protein; west., Western blot.

Thus, to determine tRNA steady-state levels, mitochondrial RNA from different uninduced and induced ATOM subunit-RNAi cell lines (32) was isolated from equal cell equivalents of digitonin-extracted pellets. To prevent pleiotropic effects, the induced cell lines were analyzed at the onset of the growth phenotype (Fig. S2). As an internal control for the yield of the multistep RNA purification protocol, 1 pmol of a short synthetic RNA molecule was added to each pellet before RNA isolation. Subsequently, the RNA samples were separated on gels, visualized by ethidium bromide-staining, and analyzed by Northern hybridization for the presence of the efficiently imported tRNAIle (30). In addition, protein samples of the digitonin-extracted pellets were analyzed on immunoblots for the levels of lipoamide dehydrogenase (LDH). LDH is a soluble protein of the mitochondrial matrix. Its recovery in the pellet fractions indicates the structural integrity of the mitochondria after digitonin extraction. Moreover, LDH has a long half-life and its mitochondrial steady-state levels, in contrast to many other mitochondrial proteins, are only affected at late time points after ablation of protein import. Thus, its abundance at early times of induction after RNAi is proportional to the amounts of mitochondria. The steady-state levels of the tRNAIle in uninduced and induced RNAi cell lines was quantified on Northern blots and normalized with the levels of the synthetic RNA molecule that serves as a control for the RNA extraction. All experiments were replicated four to six times to allow for statistical analysis.

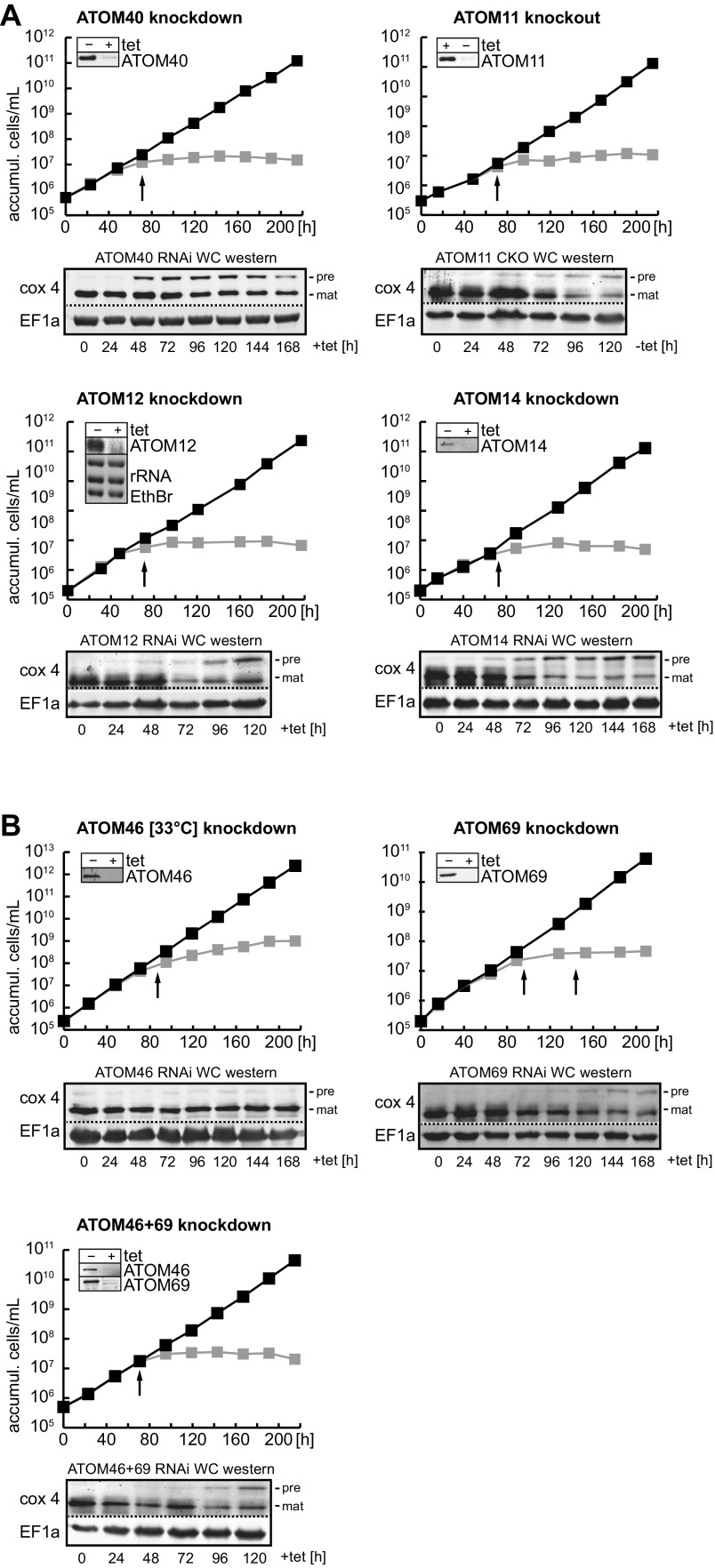

Fig. S2.

Ablation of ATOM subunits affects growth and mitochondrial protein import. Growth curves of uninduced (−tet) and induced (+tet) procyclic forms of the indicated knockdown cell lines for ATOM core (A) and ATOM receptor subunits (B), respectively. The ablated protein is indicated at the top of the graph. Cells were grown at 27 °C and in the case of ATOM46 at 33 °C. All experiments are based on tet-inducible RNAi cell lines, except for ATOM11 for which a conditional knockout cell line was used. This cell line allows depletion of ATOM11 in the absence of tet. (Insets) Immunoblots confirming successful knockdowns. In the case of ATOM12 the knockdown was confirmed by Northern blots. Black arrows indicate the time at which the tRNA import phenotype was assayed (Fig. 1). Below each graph an immunoblot depicting the steady-state levels of Cox4 at the indicated days of induction is shown. Both the accumulation (accumul.) of unprocessed precursor (pre) of Cox4 and the decline of its mature form (mat) are a proxy for the inhibition of mitochondrial protein import (57).

In a first set of experiments we focused on the pore-forming ATOM40 and the core subunits ATOM11, ATOM12, and ATOM14. As previously shown, knockdown of these proteins leads to a growth arrest under all tested conditions, including in an engineered bloodstream form cell line that can grow in the absence of mitochondrial DNA. Moreover, concomitant with the growth arrest an inhibition of mitochondrial protein import was observed both in vitro and in vivo (32) (Fig. S2A).

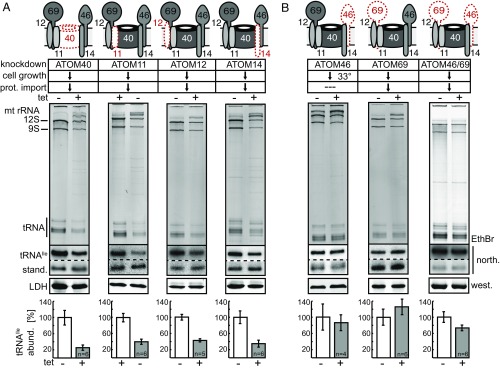

As evident from Fig. 1A, down-regulation of any of the four tested ATOM subunits resulted in a significant reduction of the amounts of mitochondrial tRNAIle, which likely is due to an inhibition of mitochondrial tRNA import. The ethidium bromide-stained gel shows that the same reduction is seen for the entire tRNA region, indicating that all tRNAs behave the same. With 75% the reduction of the tRNAIle levels in the absence of ATOM40 was slightly higher than the ≈60% observed for ATOM11, ATOM12, and ATOM14. Thus, these results show that tRNA import becomes drastically reduces in the absence of any of the four tested ATOM complex core subunits, suggesting they are directly or indirectly required for mitochondrial tRNA import.

Fig. 1.

In vivo import of tRNAs depends on ATOM core but not on ATOM receptor subunits. (A) The sketch at the top shows a model of the ATOM complex and denotes which of the ATOM core subunits were knocked down (dashed red line). The table summarizes the previously established phenotypes of the indicated cell lines regarding growth and mitochondrial protein import (32) (downward arrow, reduced) (see also Fig. S2). All experiments are based on tetracycline (Tet)-inducible RNAi cell lines, except for ATOM11 in procyclic cells for which a conditional knockout cell line was used. This cell line allows depletion of ATOM11 in the absence of Tet. The ethidium bromide-stained (EthBr) gels below the table show mitochondrial RNA extracts separated on 8 M urea/10% polyacrylamide gels that were isolated from the indicated uninduced and induced cell lines. The positions of the 12S and 9S mitochondrial rRNAs and the tRNA region are indicated. The two panels below show the corresponding Northern blots probed either for tRNAIle or the short synthetic RNA molecule (stand.) that was used as an internal standard for the yield of the RNA preparation. The panel below the Northern blots shows an immunoblot of the same mitochondrial fractions probed for LDH. It serves as a quality control for the intactness and yield of the mitochondria present in the digitonin-extracted pellet fractions. The graph at the bottom shows the quantification of the abundance of the tRNAIle normalized to the levels of the short synthetic RNA molecule that was used to control for the yield of the RNA extraction. The mean of four to six replicate experiments (as indicated) is shown. Bar, average deviation. (B) As in A, but RNAi cell lines for the ATOM receptor subunits ATOM46 and ATOM69 were tested. Ablation of ATOM46 did not impair growth at 27 °C. However, a growth arrest was observed at 33 °C, which is why the experiment was performed at 33 °C. abund., abundance; north., Northern blot; prot., protein; west., Western blot.

In many RNAi cell lines, a set of bands larger than the mitochondrial rRNAs are visible on the ethidium bromide-stained gel. In some cases these bands are enriched in the induced RNAi cell lines (Fig. 1A). The Northern analysis in Fig. S3 shows that these bands are not unprocessed mitochondrial rRNAs, as they do not hybridize with a mitochondrial rRNA-specific probe. Rather, they correspond to cytosolic rRNAs, suggesting that in the absence of protein import cytosolic ribosomes are recruited to the surface of mitochondria.

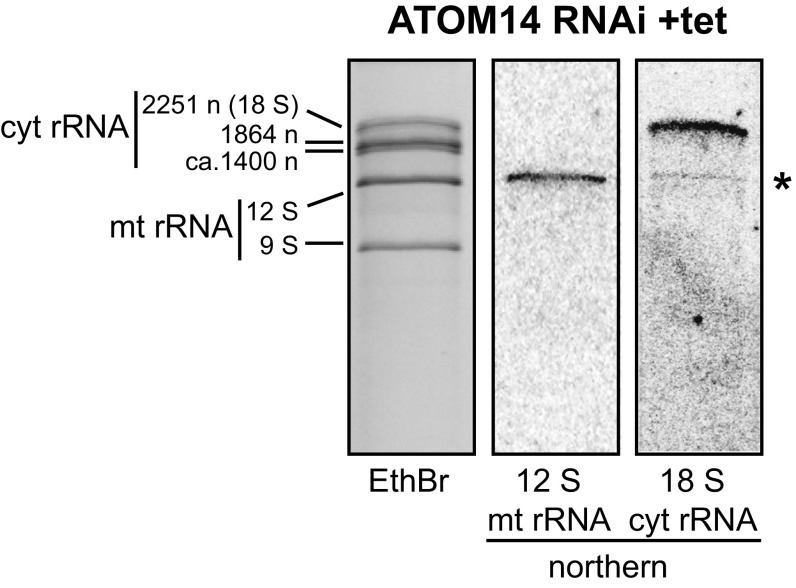

Fig. S3.

The high molecular bands above the mitochondrial rRNAs are contaminating cytosolic rRNAs. (Left) Magnification of the top region of the EthBr gel of the induced ATOM14-RNAi cell line (same gel as shown in Fig. 1A). The three large cytosolic rRNAs and their respective sizes are indicated. (Center) Northern blot of the same region blot probed for the 12S mitochondrial rRNA using the oligonucleotide 5′-AGGAGAGTAGGACTTGCCCT-3′. (Right) The same Northern blot was stripped and reprobed for the cytosolic 18S rRNA using the oligonucleotide 5′-TGGTAAAGTTCCCCGTGTTGA-3′. The asterisk indicates the residual signal of the 12S rRNA that was left after stripping of the blot.

In Vivo Import of tRNAs Does Not Require ATOM Receptor Subunits.

In a second set of experiments, we asked whether the protein receptor subunits ATOM46 and ATOM69 are also required for tRNA import. The role of these two proteins in protein import has previously been studied (32). Their large cytosolic domains bind mitochondrial precursor proteins with distinct but in part overlapping specificities. ATOM69, as all ATOM core subunits, is essential for growth under all conditions and for mitochondrial protein import in vivo. ATOM46-depleted cells grow normally at the standard temperature of 27 °C but show a growth arrest at the elevated temperature of 33 °C (32) (Fig. S2B). In the ATOM69/ATOM46 double-knockdown cell line, the growth phenotype is stronger than in the ATOM69-RNA cell line and in vitro import of proteins is inhibited as well (32). Thus, regarding growth and protein import, the ATOM69/ATOM46 double-knockdown cell line shows the same phenotypes as the ones observed after ablation of any of the ATOM core subunits discussed in the previous paragraph.

Fig. 1B shows that, in contrast to the core subunits, ablation of the receptor subunit ATOM69 did not lead to reduced steady-state levels of mitochondrial tRNAs. This was not only the case at the time when the growth arrest becomes evident (Fig. 1B), but also 2 d after appearance the growth phenotype (Fig. S4). At this later time point, protein import is completely abolished and the cells may start to suffer from secondary effects caused by the lack of imported proteins.

Fig. S4.

Ablation of ATOM69 for 6 d does not abolish mitochondrial tRNA import. Same as Fig. 1B but RNAi induction of the ATOM69 cell line was done until 2 d after the appearance of the growth arrest (see second arrow in the ATOM69-RNAi cell line growth curve in Fig. S2B). The panel showing the accumulation of the precursor of Cox4 is also shown. abund., abundance; north., Northern blot; prot., protein; west., Western blot.

The same results were obtained when cells ablated for ATOM46 were assayed at 33 °C. Importantly, the simultaneous down-regulation of both receptor subunits also had only a negligible effect on mitochondrial tRNA levels (Fig. 1B). These data indicate that while tRNA import requires the ATOM core subunits, it is independent of the protein import receptors ATOM46 and ATOM69. Thus, in the ATOM46/ATOM69 double-knockdown cell line, tRNA import has been uncoupled from protein import. These results strongly suggest that the inhibition of mitochondrial tRNA import observed after ablation of the individual ATOM core subunits (Fig. 1A) is a consequence of a nonfunctional ATOM complex.

OM Proteins Reduced in Abundance in ATOM Subunit-Lacking Cells.

The analysis of the results in Fig. 1 is complicated by the fact that ablation of a specific ATOM subunit affects the steady-state levels of the other subunits in a complex way (32). To better define the role of ATOM40, ATOM11, and ATOM12 in tRNA import, we compared the effects their ablation has on the previously characterized OM proteome (44) using mitochondria-enriched digitonin pellets of uninduced and induced RNAi cell lines in combination with stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC). Fig. 2 shows all proteins of the OM proteome whose levels were reduced more than twofold upon ablation of the indicated ATOM subunits as follows. (i) Ablation of ATOM40 lead to greatly reduced levels of ATOM14, ATOM11, ATOM46, and ATOM69 (Fig. 2A). The down-regulated protein import receptors ATOM46 and ATOM69 cannot be responsible for the phenotype as their individual or combined ablation does not affect tRNA import (Fig. 1B and Fig. S4). Thus, the proteomic analysis of the ATOM40 RNAi cell line firmly links tRNA import to the ATOM complex. However, it is not clear whether the inhibition of import is due to individual or combined ablation of ATOM40, ATOM14, and ATOM11. (ii) Ablation of ATOM11, while affecting tRNA import, does not reduce the levels of any other ATOM subunits besides the receptors ATOM46 and ATOM69, suggesting it might have a direct role in mitochondrial tRNA import (Fig. 2B). (iii) The inhibition of tRNA import observed in the ATOM12-RNAi cell line is likely due to ATOM12 itself, which is most efficiently down-regulated. The only other ATOM subunit whose level is more than twofold reduced is ATOM14 (Fig. 2C).

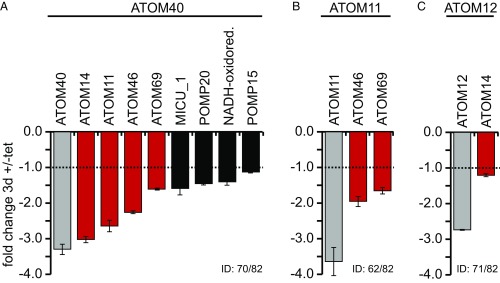

Fig. 2.

OM proteins reduced in abundance in ATOM subunit-lacking cells. (A) Abundance changes in OM proteins of procyclic T. brucei induced by conditional ablation of ATOM40 (A), ATOM11 (B), and ATOM12 (C), respectively, were analyzed by SILAC-MS. Time of induction is indicated by the arrows in Fig. S2. The graph shows all OM proteins quantified in at least two of the three replicates (P < 0.05) that were down-regulated more than twofold in ablated cells (SDs are indicated). ID indicates how many of the 82 mitochondrial OM proteins (44) were identified in the corresponding experiments. Gray columns, target of ablation; red columns, ATOM subunits; white columns, other proteins; MICU1, mitochondral calcium uptake 1; oxidored., oxidoreductase; POMP, protein of the OM proteome. Data for ATOM40 are from ref. 57.

The data shown in Fig. 2 allow a critical examination of the possibility that the observed tRNA import inhibition in the ATOM40-, ATOM11-, and ATOM12-RNAi cell lines might be an indirect effect, caused by reduced import of a hypothetical OM tRNA import factor that is not an ATOM subunit. In all RNAi cell lines shown in Fig. 1A, tRNA import is reduced by at least 2.5-fold, indicating that, if a hypothetical tRNA import factor would be responsible for the phenotype, its level should be reduced to the same extent. However, except for the ATOM subunits (Fig. 2, red bars), there are only very few proteins that are more than twofold down-regulated in any of the three proteomically analyzed RNAi cell lines. Four candidates are found in the ATOM40-RNAi cell lines, namely MICU, POMP20, the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase Tb927.11.9930, and POMP15 (Fig. 2A). Finally, in the ATOM11- and ATOM12-RNAi cell lines, no proteins, other than ATOM11 and ATOM12 itself, are sufficiently down-regulated to explain the observed reduction in tRNA import (Fig. 2 B and C).

More than 35 different tRNAs need to be imported into the trypanosome mitochondrion in quantities sufficient to support organellar translation (30). Thus, in analogy to mitochondrial protein import, factors that mediate tRNA import across the OM are likely abundant proteins. The coverage of the OM proteome we reached in our proteomic analyses was 76–87%, indicating that all abundant OM proteins were detected. Thus, the results shown in Fig. 2 strongly suggest that the tRNA import phenotypes observed in the RNAi cell lines shown in Fig. 1A are a direct consequence of the ablation of ATOM complex subunits and not caused by reduced levels of a hypothetical as yet unknown tRNA import factor in the OM.

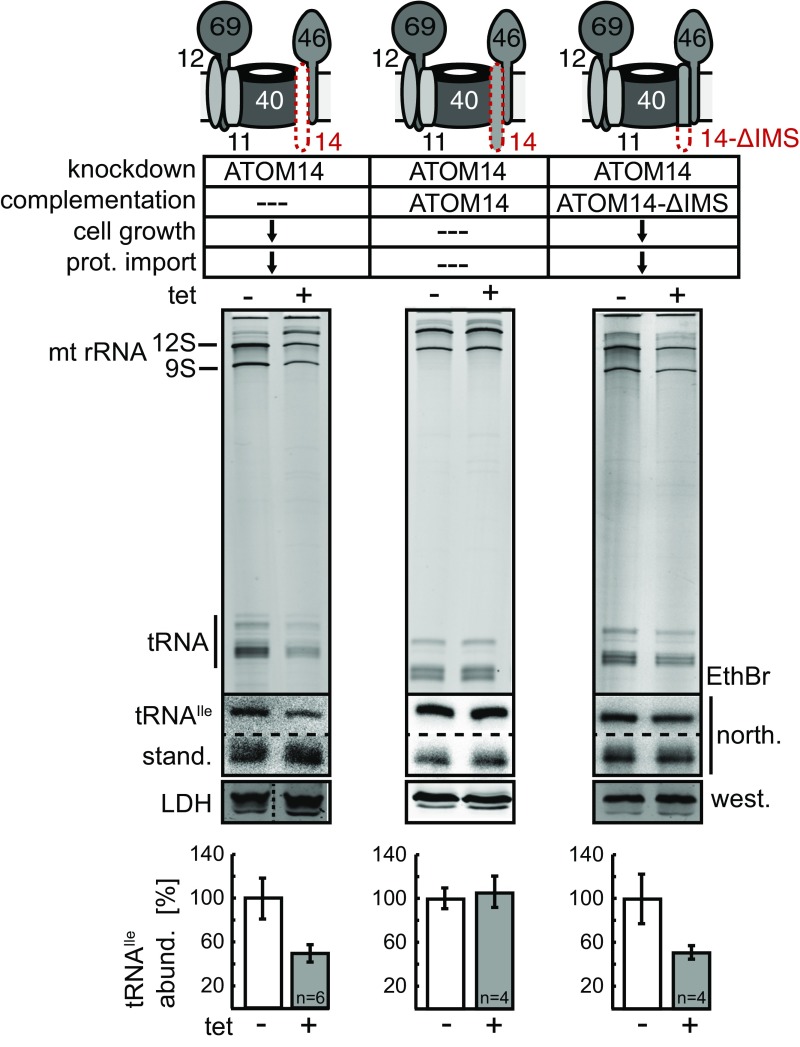

tRNA Import Requires the Intermembrane Space Domain of ATOM14.

Depletion of individual ATOM core subunits has variable effects on the architecture of the high molecular weight ATOM complex (32). It has previously been shown that replacement of full-length ATOM14, the remote Tom22 ortholog of T. brucei, with a truncated variant that lacks the C-terminal intermembrane space (IMS) exposed domain results in a growth arrest and inhibits mitochondrial protein import (45). However, in contrast to the cell line where the entire ATOM14 is depleted, the assembly of the high molecular weight ATOM complex is not affected in the cells expressing the truncated ATOM14 variant (45). We thus asked the question if this protein-import–incompetent ATOM complex is still able to translocate tRNA. As shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. S5, this was not the case. Knockdown of ATOM14 using an RNAi cell line targeting the 3′UTR of the ATOM14 mRNA reduced the tRNA steady-state levels to similar values as the cell line used in Fig. 1A, where the RNAi was directed against the ORF. Expression of the truncated ATOM14 variant in the background of the ATOM14 3′UTR-RNAi cell line, however, showed the same reduction of tRNA import, indicating that the protein-import–defective ATOM complex is also defective for tRNA import. The control in which the 3′UTR cell line was complemented with full-length ATOM14 behave like wild-type, as would be expected. In summary, these results suggest a direct involvement of the IMS-domain of ATOM14 in both protein and tRNA import.

Fig. 3.

tRNA import requires the intermembrane space domain of ATOM14. As in Fig. 1, but tRNA import was compared between an induced ATOM14 3′UTR-RNAi cell line (Left) and the same cell line complemented with either full length ATOM14, or a ATOM14 variant lacking the IMS domain (ATOM14-ΔIMS). It has previously been shown that the IMS domain of ATOM14 is required for growth and mitochondrial protein import, as shown in Fig. S5 (45). abund., abundance; north., Northern blot; prot., protein; west., Western blot.

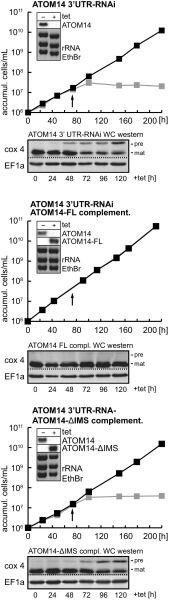

Fig. S5.

Controls for the complementation experiments shown in Fig. 3. Growth curves of ATOM14 3′UTR RNAi cell line and its derivatives ectopically expressing full-length ATOM14 (ATOM14-FL) or a truncated variant thereof that lacks the C-terminal IMS domain (ATOM14-ΔIMS). The Insets depict Northern blots verifying the efficiency of the RNAi and the expression of the ectopically expressed ATOM14 variants. accumul., accumulation.

Obstruction of the ATOM40 Pore Abolishes tRNA Import.

The β-barrel protein ATOM40, which has some similarity to Tom40 of other eukaryotes (46, 47), forms the pore across which proteins are translocated across the OM. Fig. 1A shows that ablation of ATOM40 impedes mitochondrial tRNA import, which raises the question whether import of tRNAs and proteins uses the same OM pore.

We have recently shown that by expression of a fusion protein comprised of the N-terminal 160 aa of mitochondrial LDH fused to mouse dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), followed by a C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA)-tag, we can produce an import intermediate that is stuck in the import pore (48). Under standard conditions, the fusion protein (LDH-DHFR-HA) is completely translocated into the mitochondrial matrix across both mitochondrial membranes. However, in the presence of the folic acid analog aminopterin, the DHFR adopts a conformation that is structurally rigid and therefore cannot be imported. Addition of aminopterin to a cell line expressing LDH-DHFR-HA therefore results in the formation of an intermediate that blocks the import channels in both the ATOM complex and the protein translocase of the inner membrane. It has been shown that in these cell lines, further import of mitochondrial proteins is abolished (48).

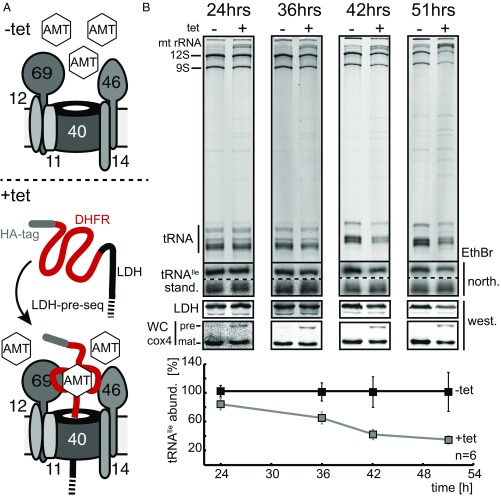

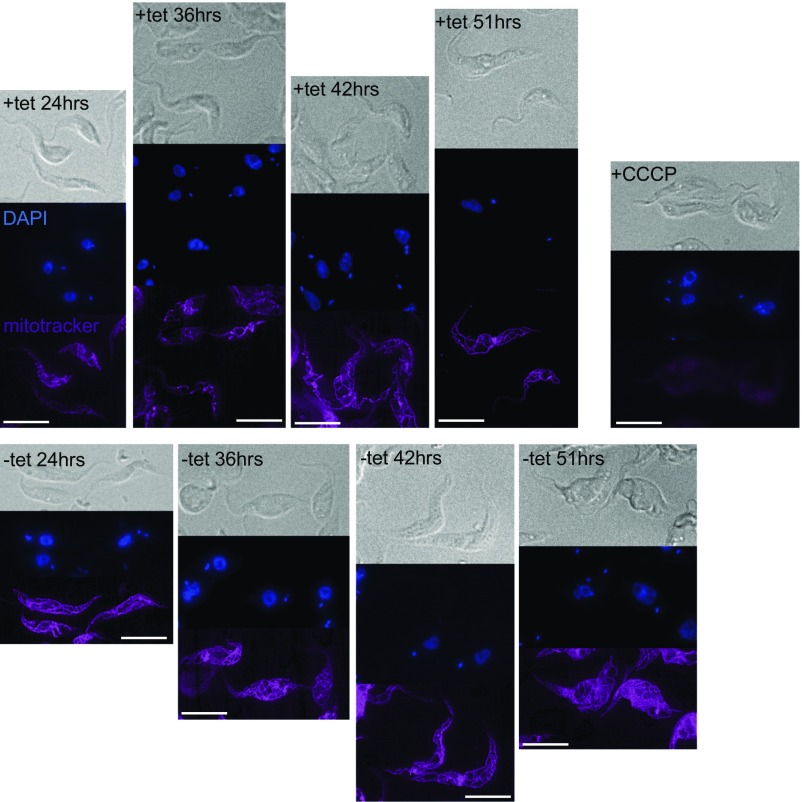

In the experiment shown in Fig. 4, we compared the kinetics of mitochondrial tRNA abundance between two cell cultures. Both were incubated with aminopterin but only one received tetracycline and thus expressed the LDH-DHFR-HA fusion protein. Aminopterin slows down cell growth; however, for the duration of the experiment the mitochondrial integrity and the membrane potential were not compromised, as verified by Mitotracker staining (Fig. S6). The Lower panels of Fig. 4 show that expression of LDH-DHFR-HA in the presence of aminopterin lead to the formation of the LDH-DFHR-HA import intermediate, which blocked further import of proteins as evidenced by the accumulation of unprocessed cytochrome oxidase subunit 4 (Cox4) precursor on immunoblots. Northern analysis shows a dramatic decline of the levels of the imported tRNAIle that is specific for the cells in which LDH-DFHR-HA is expressed and the import intermediated is formed. The decline increases the longer the channel gets blocked by the import intermediate, and is seen for the entire tRNA region visualized on the ethidium bromide-stained gels. These results strongly suggest that proteins and tRNAs use the same pore for import across the OM.

Fig. 4.

Obstruction of the ATOM40 pore abolishes tRNA import. (A) The sketch shows how in cells treated with aminopterin (AMT) expression of the LDH-DHFR-HA fusion protein generates an import intermediate that is stuck in the ATOM40 protein import channel (48). (B) The EthBr gels show mitochondrial RNA extracts isolated from cells grown in the presence of aminopterin that either do (+tet) or do not express the LDH-DHFR-HA fusion protein (−tet) for the time indicated. The two panels below show the corresponding Northern blots probed either for tRNAIle or the short synthetic RNA molecule (stand.) that was used as an internal standard. Below the Northern blots, immunoblots of the same mitochondrial fractions probed for LDH are shown. The lowest panel depicts an immunoblot probed for the imported protein Cox4. The positions of unprocessed Cox4 (pre), indicative of the nonimported protein, and mature Cox4, corresponding to the imported protein are indicated. The graph at the bottom shows the mean of the abundance of the tRNAIle normalized to the levels of the short synthetic RNA molecule in six replicates of either uninduced cells (−tet) or cells induced (+tet) for the indicated times. Bar, average deviation. abund., abundance; north., Northern blot; prot., protein; west., Western blot.

Fig. S6.

Blocking the ATOM complex by an import intermediate does not abolish the mitochondrial membrane potential. Cells expressing the LDH-DHFR-HA fusion protein (+tet) that were grown in the presence of aminopterin for 24–51 h, to induce the protein import intermediate, were monitored for their membrane potential and mitochondrial morphology using Mitotracker staining. Control cells (−tet) grown under the same conditions, in the presence of aminopterin, but which did not express LDH-DHFR-HA, were also analyzed. Ablation of the membrane potential of uninduced cells by CCCP serves as a negative control. (Scale bars, 10 µm.)

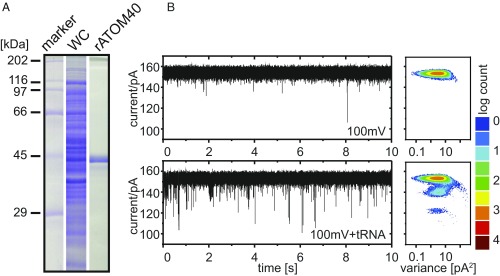

tRNA Influences Conductance of the Recombinant ATOM40 Pore.

From the in vivo data we concluded that ATOM40 might represent the channel that translocates tRNAs across the OM. Our efforts to demonstrate a direct interaction between tRNAs and ATOM40 by gel-shift assays or flotation experiments using vesicles containing recombinant ATOM40 were unsuccessful. This is likely due to the fact that the interaction between the tRNA and its import channel is transient.

Thus, to measure direct interaction between ATOM40 and tRNAs we performed electrophysiology experiments. We have previously shown that ATOM40 forms a hydrophilic pore of large conductance and high open probability, and that addition of the N-terminal presequence of a substrate protein induced transient pore closure (49). Thus, we analogously expressed and purified recombinant ATOM40 to near homogeneity (Fig. 5A) and reconstituted individual ATOM40 molecules into planar lipid bilayers for single-channel current measurement. Fig. 5B shows a representative experiment with ATOM40 displaying the typical conductivity of approximately 1.5 nS with few gating events at a holding potential of 100 mV (Fig. 5B, Upper). Instead of adding a presequence peptide as in the previous study, we added isolated tRNAs to the sample. Fig. 5B shows that, just as for the peptide, this resulted in channel flickering, indicating that interaction of the added tRNAs with recombinant ATOM40 induced temporary closure or obstruction of the ATOM40 channel (Fig. 5B, Lower). These results are consistent with the results of the LDH-DHFR-HA/aminopterin experiment (Fig. 4) and indicate that import of tRNAs and proteins across the mitochondrial OM use the same import pore.

Fig. 5.

tRNA influences conductance of the recombinant ATOM40 pore as measured by single channel electrophysiology experiments. (A) Recombinant ATOM40 (rATOM40) was purified from E. coli to near homogeneity under denaturing conditions (WC, whole cell lysate). (B, Upper) rATOM40 was reconstituted into a planar lipid bilayer and displays its typical electrophysiological characteristics (1.5 ns, few gating events) (49). (Lower) Addition of tRNA to both sides of the chamber induced frequent but temporary closure of the rATOM40 channel.

Discussion

We have investigated how trypanosomal tRNAs are translocated across the mitochondrial OM under physiological conditions. Our results reveal a tight connection between mitochondrial tRNA and protein import. Ablation of any of the core subunits of the ATOM complex, the trypanosomal analog of the TOM complex in other eukaryotes, also abolished tRNA import. Replacement of ATOM14 with a truncated variant did not disturb the overall architecture of the ATOM complex (45) but inhibited both protein and tRNA import. Finally, when the mitochondrial protein import channels are blocked by an import substrate whose C-terminal moiety cannot be unfolded (48), we see a concomitant reduction of protein and tRNA import.

At a first glimpse these results appear to support the coimport model, which posits that tRNAs associate with mitochondrial precursor proteins and that the resulting tRNA/protein complexes are imported along the protein import pathway. However, a closer look also reveals discrepancies that are not in line with the coimport model. Ablation of the protein import receptor ATOM69 or combined ablation of both receptors, ATOM69 and ATOM46, inhibited protein import and caused a growth arrest (32), but did not affect mitochondrial tRNA import, showing that in T. brucei it is possible to uncouple protein from tRNA import. This contrasts with import of the tRNALys into yeast mitochondria, the best-studied example of the coimport model. Here, ablation of the protein import receptor Tom20, the trypanosomal analog of which is ATOM69, abolished import of the tRNALys since the precursor of mitochondrial lysyl-tRNA synthetase, which serves as carrier for the process, could no longer be imported (24).

Nevertheless, it is presently not possible to exclude the coimport model for the translocation of trypanosomal tRNAs across the OM with certainty. However, should it apply, our results impose strong constraints on the properties of a hypothetical tRNA-binding carrier protein. It would need to be imported into mitochondria independently of the two protein import receptors ATOM46 and ATOM69. Presently no such protein is known.

Based on in vitro import experiments, it has been proposed that the direct import model applies for mitochondrial tRNA import in plants. Antibody inhibition experiments indicate that the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) is the pore, or at least a component thereof, that translocates tRNAs across the mitochondrial OM (50). However, interestingly, components of the protein import system, such as Tom20 and Tom40, also appear to be involved in the process. The direct import model implies that the tRNAs, which will be imported into mitochondria, can directly interact with the translocation pore. This prediction was experimentally confirmed in potato, where imported tRNAs were shown to differentially bind to recombinant versions of the two VDAC isoforms (51).

In summary, our results show that mitochondrial tRNA import across the OM in T. brucei has features of both the coimport model, as well as the direct import model. Thus, it might be useful to introduce a third intermediate model, where tRNAs and proteins are imported by the same machinery and even use the same import pore, but where tRNA import is nevertheless not coupled to protein import (Fig. S7). This third model implies that imported tRNAs will directly, although probably transiently, interact with the protein import channel, and possibly with other components of the protein import machinery. Indeed the results of electrophysiological single-channel measurements indicate that bulk tRNAs can transiently block isolated ATOM40 pores in the absence of any of the other ATOM subunits. Moreover, our results suggest that tRNAs may also interact with the IMS domain of ATOM14.

Fig. S7.

Models for tRNA import across the OM. (Left) “Direct import” model: tRNAs are imported into mitochondria as naked molecules, across a pore that is distinct from the protein translocase pore (e.g., VDAC in plants). (Center) “Co-import” model: tRNAs binds to a mitochondrial precursor protein (e.g., mitochondrial lysyl-tRNA synthetase in yeast) and is coimported with the protein across the protein import channel (Tom40 in yeast). Gray bar, mitochondrial targeting sequence. (Right) “Alternate import“ model, tRNAs are imported into mitochondria as naked molecules across the protein import pore (e.g. ATOM40 in Trypanosoma brucei). In this model translocation of tRNAs is uncoupled from the translocation of proteins.

The present study focuses on the mitochondrial OM and provides no information of how tRNAs are translocated across the inner membrane. In a highly controversial study in Leishmania tropica, a close relative of T. brucei, a protein complex of the inner membrane, termed RIC, one component of which is the α‐subunit of the F1–ATP synthase complex, has been implicated in tRNA import (52, 53). A more recent in vivo study, on the other hand, challenges these results and suggests that import of tRNAs across the inner membrane requires TbTim17, the core subunit of the trypanosomal inner membrane translocase (TIM complex) (48), which is consistent with the idea that tRNAs and proteins may also use the same pore for transport across the inner membrane (54).

We conclude that the trypanosomal ATOM complex has a dual function: it translocates not only proteins but also tRNAs across the OM of mitochondria. However, a single ATOM complex likely either transports proteins or tRNAs, but not both simultaneously. In wild-type cells there are up to four distinct ATOM complexes of different molecular weights. The main difference between them is the extent to which they are associated with the protein import receptors ATOM46 and ATOM69 (32). It is tempting to speculate that the ATOM complex showing the lowest molecular weight, which is termed the core complex and that essentially lacks the receptor subunits, might be specialized for mitochondrial tRNA import, whereas the ATOM complexes of higher molecular weight might mainly be engaged in protein import.

In the T. brucei mitochondrial protein, import is essential under all conditions, as in all other eukaryotes. Mitochondrial translation and therefore mitochondrial tRNA import was shown to be essential in both procyclic and bloodstream forms of T. brucei. The trypanosomal ATOM complex, which mediates both protein and tRNA import and to a large part is composed of trypanosome-specific subunits, is therefore an excellent novel drug target.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic Cell Lines.

All cell lines are based on procyclic T. brucei strain 29-13. Cells were grown at 27 °C in SDM-79 containing 10% (vol/vol) FCS. The tetracycline-inducible RNAi cell lines for ATOM12, ATOM14, ATOM40, ATOM46, ATOM69, the double-knockdown ATOM46/69 and the conditional knockout cell line ATOM11 have been describe before (32, 33). Transfection and generation of clonal cell lines was achieved as described previously (55). The ATOM14 3′UTR RNAi cell line and the complementation of this cell line with the truncated ATOM14 lacking the IMS domain is described in ref. 45. The cell line expressing the import intermediate LDH-DHFR-HA fusion protein used to produce the import intermediate was described in ref. 48.

Monitoring of Mitochondrial tRNA Abundance.

The RNAi cell lines were induced by addition of 1 µg/mL tetracycline to the medium. Induction time for ATOM12, ATOM14, ATOM40, and ATOM46/A69 RNAi cell lines was 3 d. The ATOM69 RNAi cell line was induced for 4 and 6 d, whereas the ATOM46 cell line was induced for 3.5 d at 33 °C. The conditional knockout cell line for ATOM11 was assayed 3 d after removal of tetracycline. Induction times were chosen to coincide with the onset of the growth phenotypes (45). Equal numbers (1–2 × 108) of uninduced and induced cells were harvested and a mitochondria-enriched fraction was prepared using digitonin extraction and RNase A digestion (30). Subsequently 1 pmol of an RNA oligonucleotide (5′-GGAGCUCGCCCGGGCGAGGCCGUGCCAGCUCUUCGGAGCAAUACUCGGC-3′, 49 nt) was added to each sample. It serves as an internal standard for the yield of the RNA extraction. Finally, mitochondrial RNA was isolated using the acid guanidinium method (56). The resulting RNA fractions were separated on denaturing 10% polyacrylamide gels containing 8 M urea and stained with ethidium bromide. Gels were electroblotted (200 mA for 14–18 h) onto charged nylon membranes (Genescreen Plus Hybridization Transfer Membrane), UV cross-linked (250 mJ/cm2), and probed for tRNAIle and the RNA oligonucleotide (49-mer; see above), which served as internal standard. The blots were hybridized in 6× SSPE (60 mM NaH2PO4, 0.9 M NaCl, 6 mM EDTA) containing 5× Denhardt’s and 0.5% (wt/vol) SDS at 55 °C for 14–18 h with 10 pmol of 5′-labeled oligonuceotides (tRNAIle: 5′-TGCTCCCGGCGGGTTCGAA-3′; internal standard: 5′-GCCGAGTATTGCTCCGAAG-3′) using γ[32P]ATP and the polynucleotide kinase forward reaction. The Northern blots were analyzed and quantified using a PhosphorImager. The signal corresponding to the tRNAIle was normalized to the signal of the internal standard. For each quantified signal, the mean and SEs of four-to-six independent replicates were calculated and plotted on the graphs. Samples for SDS/PAGE and subsequent immunoblot analysis were collected after the digitonin fractionation. Immunoblots were probed for LDH and Cox4. For the stalling of the ATOM complex by the import intermediate, formed by LDH-DHFR-HA, the cells were grown in the presence of 250 µM aminopterin, and induced with tetracycline for 24–51 h before mitochondrial RNA isolation.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis.

LC-MS analysis of mitochondria-enriched fractions generated from tetracycline-treated and untreated SILAC-labeled ATOM40-, ATOM11-, or ATOM12-RNAi cells (n = 3) was performed as previously described (57). Briefly, proteins were acetone-precipitated and separated by SDS/PAGE followed by colloidal Coomassie staining. Gel lanes were cut and proteins were in-gel digested using trypsin (37 °C, overnight) after reduction and alkylation of cysteine residues. Peptide samples were dried in vacuo and resuspended in 0.1% TFA for LC-MS analysis on an Orbitrap Elite instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) connected to an UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Full MS spectra (m/z 370–1,700) were acquired in the orbitrap at a resolution of 120,000 (at m/z 400). For acquisition of MS/MS spectra, low-energy collision-induced dissociation of isolated multiply charged peptides was performed in the linear ion trap. Data were analyzed using MaxQuant (58) (v1.5.5.1) and its integrated search engine Andromeda (59). MS/MS data were searched against all entries for T. brucei TREU927 (TriTryp database, v8.1; 11,067), to which the 18 mitochondrially encoded proteins (dna.kdna.ucla.edu/trypanosome/seqs/index.html) were added, using the following parameters: tryptic specificity (maximum of two missed cleavages; Trypsin/P); mass tolerances, 4.5 ppm for precursor, and 0.5 Da for fragment ions; fixed modification, carbamidomethylation of cysteine; variable modifications, N-terminal acetylation and methionine oxidation; heavy labels, Arg10 and Lys8. Proteins were identified based on at least one unique peptide (minimum length, 7 aa) and a false-discovery rate of 0.01 applied to both peptide and protein level. Proteins were quantified based on unique peptides and with a minimum ratio count of one. The options “requantify” and “match between runs” were enabled.

Immunofluorescence.

For immunofluorescence, 1 × 107 of aminopterin-treated cells that do or do not express LDH-DHFR-HA were incubated with 250 nM MitoTracker Red CM-H2-XRos (Molecular Probes) for 20 min at 27 °C. As negative control, uninduced cells were incubated with 100 µM carbonylcyanid-m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) for 20 min to dissipate the membrane potential. Subsequently the cells were fixed in 1× PBS/4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 1× PBS/0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min and immunofluorescence was done as described previously (60). Slides were mounted using Vectashield containing 1.5 µg/mL DAPI (Vector Laboratories). The images were obtained from a Leica DMI6000 B microscope.

Recombinant Protein Purification and Reconstitution.

Recombinant (r) ATOM40 was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) and purified from inclusion bodies using immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography in combination with Ni2+ at denaturing conditions (8 M urea) and an additional anion exchange chromatography step, as described previously (49). Affinity purified rATOM40 was solubilized in 2% (wt/vol) SDS and reconstitution was carried out as described previously (49).

Single Channel Recordings from Planar Lipid Bilayers.

Planar lipid bilayer measurements of reconstituted rATOM40 were essentially performed as described previously (49, 61). Briefly, single-channel currents were measured in standard buffer conditions (250 mM KCl, 10 mM Mops/Tris pH 7) in the absence and presence of 150 µM tRNA (bulk tRNA from baker’s yeast; Roche) on both sides of the bilayer using a GeneClamp 500 amplifier and the CV-5-1G headstage (Axon Instruments). Filtering was conducted with the inbuilt four-pole Bessel low-pass filter (5 kHz). Data were recorded at a sampling rate of 50 kHz using a DigiData 1200 (Axon Instruments) and Clampex 9 software.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elke Horn and Kurt Lobenwein for technical assistance. M.N. and A.H. were supported by fellowships from the Peter und Traudl Engelhorn foundation. Research in the laboratory of A.S. was supported by Grant 138355, and in part by the National Centers for Competence in Research “RNA & Disease,” both funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. Research in the B.W. group was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal & State Governments (EXC 294 BIOSS Centre for Biological Signalling Studies), and the European Research Council (Consolidator Grant 648235).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1711430114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Archibald JM. Endosymbiosis and eukaryotic cell evolution. Curr Biol. 2015;25:R911–R921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams TA, Foster PG, Cox CJ, Embley TM. An archaeal origin of eukaryotes supports only two primary domains of life. Nature. 2013;504:231–236. doi: 10.1038/nature12779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koonin EV, Yutin N. The dispersed archaeal eukaryome and the complex archaeal ancestor of eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:a016188. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. Mitochondrial evolution. Science. 1999;283:1476–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen JF. Why chloroplasts and mitochondria contain genomes. Comp Funct Genomics. 2003;4:31–36. doi: 10.1002/cfg.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz C, Schendzielorz A, Rehling P. Unlocking the presequence import pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chacinska A, Koehler CM, Milenkovic D, Lithgow T, Pfanner N. Importing mitochondrial proteins: Machineries and mechanisms. Cell. 2009;138:628–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt O, Pfanner N, Meisinger C. Mitochondrial protein import: From proteomics to functional mechanisms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:655–667. doi: 10.1038/nrm2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marom M, Azem A, Mokranjac D. Understanding the molecular mechanism of protein translocation across the mitochondrial inner membrane: Still a long way to go. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808:990–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salinas T, Duchêne AM, Maréchal-Drouard L. Recent advances in tRNA mitochondrial import. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfonzo JD, Söll D. Mitochondrial tRNA import—The challenge to understand has just begun. Biol Chem. 2009;390:717–722. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider A. Mitochondrial tRNA import and its consequences for mitochondrial translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:1033–1053. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060109-092838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubio MA, et al. Mammalian mitochondria have the innate ability to import tRNAs by a mechanism distinct from protein import. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9186–9191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804283105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercer TR, et al. The human mitochondrial transcriptome. Cell. 2011;146:645–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smirnov A, et al. Mitochondrial enzyme rhodanese is essential for 5 S ribosomal RNA import into human mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30792–30803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smirnov A, et al. Two distinct structural elements of 5S rRNA are needed for its import into human mitochondria. RNA. 2008;14:749–759. doi: 10.1261/rna.952208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Entelis NS, Kolesnikova OA, Dogan S, Martin RP, Tarassov IA. 5 S rRNA and tRNA import into human mitochondria. Comparison of in vitro requirements. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45642–45653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang G, Shimada E, Koehler CM, Teitell MA. PNPASE and RNA trafficking into mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:998–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Ameln S, et al. A mutation in PNPT1, encoding mitochondrial-RNA-import protein PNPase, causes hereditary hearing loss. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang G, et al. PNPASE regulates RNA import into mitochondria. Cell. 2010;142:456–467. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amunts A, Brown A, Toots J, Scheres SHW, Ramakrishnan V. Ribosome. The structure of the human mitochondrial ribosome. Science. 2015;348:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greber BJ, et al. Ribosome. The complete structure of the 55S mammalian mitochondrial ribosome. Science. 2015;348:303–308. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holzmann J, et al. RNase P without RNA: Identification and functional reconstitution of the human mitochondrial tRNA processing enzyme. Cell. 2008;135:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarassov I, Entelis N, Martin RP. An intact protein translocating machinery is required for mitochondrial import of a yeast cytoplasmic tRNA. J Mol Biol. 1995;245:315–323. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarassov I, Entelis N, Martin RP. Mitochondrial import of a cytoplasmic lysine-tRNA in yeast is mediated by cooperation of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial lysyl-tRNA synthetases. EMBO J. 1995;14:3461–3471. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolesnikova OA, et al. Suppression of mutations in mitochondrial DNA by tRNAs imported from the cytoplasm. Science. 2000;289:1931–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapushoc ST, Alfonzo JD, Rubio MAT, Simpson L. End processing precedes mitochondrial importation and editing of tRNAs in Leishmania tarentolae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37907–37914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpson AM, Suyama Y, Dewes H, Campbell DA, Simpson L. Kinetoplastid mitochondria contain functional tRNAs which are encoded in nuclear DNA and also contain small minicircle and maxicircle transcripts of unknown function. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5427–5445. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.14.5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hancock K, Hajduk SL. The mitochondrial tRNAs of Trypanosoma brucei are nuclear encoded. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19208–19215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan THP, Pach R, Crausaz A, Ivens A, Schneider A. tRNAs in Trypanosoma brucei: Genomic organization, expression, and mitochondrial import. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3707–3717. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3707-3716.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mani J, Meisinger C, Schneider A. Peeping at TOMs-diverse entry gates to mitochondria provide insights into the evolution of eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:337–351. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mani J, et al. Mitochondrial protein import receptors in kinetoplastids reveal convergent evolution over large phylogenetic distances. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6646. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pusnik M, et al. Mitochondrial preprotein translocase of trypanosomatids has a bacterial origin. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1738–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desy S, Mani J, Harsman A, Käser S, Schneider A. TbLOK1/ATOM19 is a novel subunit of the noncanonical mitochondrial outer membrane protein translocase of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Microbiol. 2016;102:520–529. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crausaz Esseiva A, Maréchal-Drouard L, Cosset A, Schneider A. The T-stem determines the cytosolic or mitochondrial localization of trypanosomal tRNAsMet. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2750–2757. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauser R, Schneider A. tRNAs are imported into mitochondria of Trypanosoma brucei independently of their genomic context and genetic origin. EMBO J. 1995;14:4212–4220. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lima BD, Simpson L. Sequence-dependent in vivo importation of tRNAs into the mitochondrion of Leishmania tarentolae. RNA. 1996;2:429–440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherrer RL, Yermovsky-Kammerer AE, Hajduk SL. A sequence motif within trypanosome precursor tRNAs influences abundance and mitochondrial localization. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9061–9072. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9061-9072.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubio MA, Liu X, Yuzawa H, Alfonzo JD, Simpson L. Selective importation of RNA into isolated mitochondria from Leishmania tarentolae. RNA. 2000;6:988–1003. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200991519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nabholz CE, Horn EK, Schneider A. tRNAs and proteins are imported into mitochondria of Trypanosoma brucei by two distinct mechanisms. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2547–2557. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaneko T, et al. Wobble modification differences and subcellular localization of tRNAs in Leishmania tarentolae: Implication for tRNA sorting mechanism. EMBO J. 2003;22:657–667. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouzaidi-Tiali N, Aeby E, Charrière F, Pusnik M, Schneider A. Elongation factor 1a mediates the specificity of mitochondrial tRNA import in T. brucei. EMBO J. 2007;26:4302–4312. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cristodero M, et al. Mitochondrial translation factors of Trypanosoma brucei: Elongation factor-Tu has a unique subdomain that is essential for its function. Mol Microbiol. 2013;90:744–755. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niemann M, et al. Mitochondrial outer membrane proteome of Trypanosoma brucei reveals novel factors required to maintain mitochondrial morphology. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:515–528. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.023093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mani J, Rout S, Desy S, Schneider A. Mitochondrial protein import - Functional analysis of the highly diverged Tom22 orthologue of Trypanosoma brucei. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40738. doi: 10.1038/srep40738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zarsky V, Tachezy J, Dolezal P. Tom40 is likely common to all mitochondria. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R479–R481, author reply R481–R482. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pusnik M, et al. Response to Zarsky et al. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R481–R482. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harsman A, et al. The non-canonical mitochondrial inner membrane presequence translocase of trypanosomatids contains two essential rhomboid-like proteins. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13707. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harsman A, et al. Bacterial origin of a mitochondrial outer membrane protein translocase: New perspectives from comparative single channel electrophysiology. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:31437–31445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.392118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salinas T, et al. The voltage-dependent anion channel, a major component of the tRNA import machinery in plant mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18362–18367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606449103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salinas T, et al. Molecular basis for the differential interaction of plant mitochondrial VDAC proteins with tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:9937–9948. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goswami S, et al. A bifunctional tRNA import receptor from Leishmania mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8354–8359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510869103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schekman R. Editorial expression of concern: A bifunctional tRNA import receptor from Leishmania mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004225107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tschopp F, Charrière F, Schneider A. In vivo study in Trypanosoma brucei links mitochondrial transfer RNA import to mitochondrial protein import. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:825–832. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCulloch R, Vassella E, Burton P, Boshart M, Barry JD. Transformation of monomorphic and pleomorphic Trypanosoma brucei. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;262:53–86. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-761-0:053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peikert CD, et al. Charting organellar importomes by quantitative mass spectrometry. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15272. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cox J, et al. Andromeda: A peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1794–1805. doi: 10.1021/pr101065j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneider A, et al. Subpellicular and flagellar microtubules of Trypanosoma brucei brucei contain the same alpha-tubulin isoforms. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:431–438. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.3.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bartsch P, Harsman A, Wagner R. Single channel analysis of membrane proteins in artificial bilayer membranes. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1033:345–361. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-487-6_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]