Abstract

A new method for amino acid homologation by way of formal C–C bond functionalization is reported. This method utilizes a 2-step/1-pot protocol to convert α-amino acids to their corresponding N-protected β-amino esters through quinone-catalyzed oxidative decarboxylation/in situ Mukaiyama–Mannich addition. The scope and limitations of this chemistry are presented. This methodology provides an alternative to the classical Arndt–Eistert homologation for accessing β-amino acid derivatives. The resulting N-protected amine products can be easily deprotected to afford the corresponding free amines.

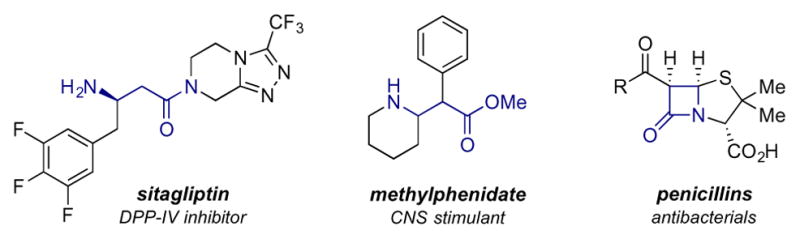

In recent years, research focused on the utilization of β-amino acid derivatives has received significant attention owing to their unique ability to resist degradation by proteases and stabilize protein secondary structure. β-amino acids are used to synthesize designer β-peptides (many of which are regarded as promising antibacterial1 and anti-HIV agents2) and a wide range of FDA-approved pharmaceutical agents (Figure 1). The increasing importance of these molecules has fueled a growing interest in the development of new methods for their preparation.3, 4

Figure 1.

β-Amino Acid Derivatives in FDA-Approved Therapeutics.

Among the established methodologies for β-amino acid synthesis, α-amino acid homologation is the most commonly employed, presumably because it utilizes inexpensive, bio-renewable starting materials (Scheme 1). Classical methods, such as the Arndt–Eistert homologation,5 the Kowalski ester homologation6 and the Kolbe reaction,7 have proven to be useful tools for converting α-amino acids into their corresponding β-amino esters. While these reactions, and their contemporary counterparts,8 have been broadly employed, they typically require many synthetic operations, utilize costly or toxic reagents, and proceed through highly reactive intermediates. We sought to develop an alternative protocol to promote such homologations by utilizing quinone organocatalysis to facilitate the transformation of α-amino acids into their corresponding N-protected β-amino ester derivatives by way of decarboxylative functionalization.9

Scheme 1.

Classical Amino Acid Homologation and This Work.

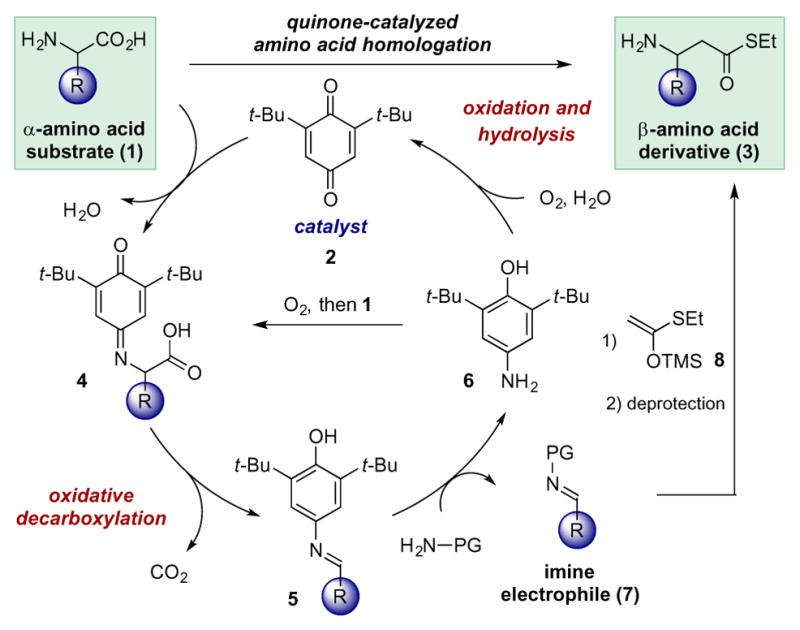

In nature, quinone cofactors are commonly employed by copper amine oxidases to enable the conversion of primary amine substrates to their corresponding carbonyl derivatives.10,11 Several recent reports have highlighted the ability of quinone cofactor mimics to enable the catalytic aerobic oxidation of primary amines.12,13,14 We sought to explore the possibility of using quinone catalysis to promote a formal C–C functionalization through oxidative decarboxylation of α-amino acids,15 followed by sequential nucleophilic addition to yield β-amino ester derivatives (Scheme 2). In such a process, we envisioned that a quinone catalyst (2) and an α-amino acid (1) would condense to generate iminoquinone 4. This intermediate would undergo quinone-enabled oxidative decarboxylation to deliver N-aryl imine 5, which would in turn participate in transimidation with an appropriately selected amine (H2N–PG) to furnish N-protected imine 7. The reduced catalyst (6) would then be returned to the catalytic cycle through reaction with molecular oxygen and 1 (or oxygen and water, both possibilities are shown). Imine 7 could then participate in a subsequent reaction with silyl ketene (thio)acetal 8 to deliver, after removal of the protecting group, the desired homologation product (3). The proposed reaction represents a significant departure from traditional cofactor chemistry wherein pyridoxal phosphate-type catalysts are employed in amino acid decarboxylation events.16 Herein we report the development of this method and its application to the efficient synthesis of β-amino ester derivatives.

Scheme 2.

Proposed Method for Quinone-Catalyzed Amino Acid Homologation.

We began by examining the potential of amino acid substrates to undergo oxidative decarboxylation in the presence of a quinone catalyst (Table 1). Quinone 2 was selected for initial studies because of it’s established ability to enable the aerobic oxidation of amines.17 Valine, phenylalanine, serine and phenylglycine were first tested (entries 1–4, only phenylglycine results shown) with entry 4 providing initial conditions to promote imine formation for only the α-aryl amino acid. The addition of triethylamine as a base resulted in a slight improvement in reaction efficiency (entry 5, 42% yield) that was furthered by elevation of the reaction temperature (entry 6, 68% yield). With this result in hand, we sought to address issues with substrate solubility under these initial conditions. Not surprisingly, the use of polar organic solvents (entries 1–6) or water (entry 7) failed to dissolve the entire reaction mixture. This led us to explore the use of biphasic conditions (entries 8–11). Increasing the catalyst loading to 10 mol% provided imine 7a in 91% yield (entry 9). The temperature could be reduced under these conditions, with no loss of reaction efficiency (entries 10 and 11). While there was some evidence to the contrary,18 we anticipated that water may interfere with subsequent Mukaiyama–Mannich additions. Fortunately, ethanol proved to be an equally viable solvent for promoting decarboxylative imine formation at slightly higher temperatures (entries 12 and 13) and it could be easily removed under reduced pressure prior to imine additions. Unfortunately, all natural amino acids tested failed to provide the desired imine under the current reaction conditions.19 Examination of a range of quinone catalysts failed to improve this result.20 p-Anisidine can be replaced by a variety of N-protected amines to allow access to a wide range of imine products; these studies are detailed in the supporting information.

Table 1.

Optimization of Quinone-Catalyzed Oxidative Decarboxylation Protocol.19

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | solvent | temperature | catalyst | base | yielda |

| 1 | 1,4-Dioxane | 50°C | 5% | - | 0% |

| 2 | THF | 50°C | 5% | - | 0% |

| 3 | CH3CN | 50°C | 5% | - | 0% |

| 4 | DMSO | 50°C | 5% | - | 39% |

| 5 | DMSO | 50°C | 5% | Et3N | 42% |

| 6 | DMSO | 80°C | 5% | Et3N | 68% |

| 7 | H2O | 80°C | 5% | Et3N | 63% |

| 8 | CH3CN:H2O (1:1) | 80°C | 5% | Et3N | 74% |

| 9 | CH3CN:H2O (1:1) | 80°C | 10% | Et3N | 90% |

| 10 | CH3CN:H2O (1:1) | 50°C | 5% | Et3N | 84% |

| 11 | CH3CN:H2O (1:1) | 50°C | 10% | Et3N | 91% |

| 12 | EtOH | 50°C | 10% | Et3N | 70% |

| 13 | EtOH | 70°C | 10% | Et3N | 92% |

Determined by 1H NMR using methyl benzoate as an internal standard.

Next we investigated in situ Mukaiyama–Mannich addition21 using silyl ketene (thio)acetal 8 and the imine generated through oxidative decarboxylation of phenylglycine. After evaluating a variety of Lewis and Brønsted acid catalysts, we found that tetrafluoroboric acid was an effective promoter of the desired addition,22 providing thioester 9a in 74% yield from phenylglycine (eq. 1). This sequential oxidative decarboxylation/Mukaiyama–Mannich addition protocol provides a new methodology for amino acid homologation via decarboxylative functionalization.

|

(1) |

With optimized conditions for the oxidative decarboxylation/Mukaiyama–Mannich sequence in hand, we examined the substrate scope by assessing the efficiency of this process using a variety of amino acids (Table 2). A wide range of phenylglycine derivatives with variable substitution patterns was subjected to the optimal reaction conditions. The 2-methyl derivative displays significantly reduced reaction efficiency, presumably due to the steric hindrance caused by the methyl substituent (entry 2, 56%). The 2-chloro derivative delivered the homologation product in excellent yield (entry 3, 95% yield), presumably owing to an attenuation of the steric effect noted in entry 2 by replacement with a smaller chlorine atom.21 Meta- and para- substituted aryl glycine derivatives generally afforded good to excellent yields (entries 4–9, 72–94% yield). Notably, electronic effects do not appear to influence reaction efficiencies as electron-rich and electron-poor substrates all provided good yields of the desired product (entries 5, 6 and 7–9, respectively, 72–94% yield). 2-thiophenylglycine is also compatible under the optimized conditions (entry 10, 77% yield), proving that electron-rich heteroaryl glycine derivatives are also suitable substrates, despite the potential for competitive arene oxidation.24

Table 2.

Amino Acid Scope using Silyl Ketene (Thio)acetal Nucleophile 8.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | product | yealda |

| 1 |

|

9a, R = H, 74% |

| 2 | 9b, R = Me, 56% | |

| 3 | 9c, R = Cl, 95% | |

| 4 |

|

9d, 78% |

| 5 |

|

9e, R = Me, 89% |

| 6 | 9f, R = OMe, 88% | |

| 7 | 9g, R = F, 84% | |

| 8 | 9h, R = Cl, 94% | |

| 9 | 9i, R = Br, 94% | |

| 10 |

|

9j, 77% |

Isolated yields.

Encouraged by these results, we next extended the scope of the oxidative decarboxylation/Mukaiyama–Mannich addition sequence by employing gem-dimethyl silyl ketene acetal nucleophile 10 (Table 3). To our delight, when phenylglycine was employed as the substrate, the corresponding β-amino ester 11a was obtained in excellent yield (entry 1, 89% yield). Similar substituent effects on reaction efficiency were observed in this series when compared to those above (Table 2). Interestingly, ortho-substitution has a more prominent influence on the efficiency observed in this series of reactions (entry 2 and entry 3, 15% yield and 65% yield, respectively). This likely results from increased steric bulk of the silyl ketene acetal nucleophile leading to a reduced rate of addition, thereby enabling competitive proto-desilylation. Once again, electron-rich and electron-poor aryl glycines are well tolerated (entries 4–10, 80–94% yield).

Table 3.

Amino Acid Scope using Silyl Ketene Acetal Nucleophile 10.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | product | yealda |

| 1 |

|

11a, R = H, 89% |

| 2b | 11b, R = Me, 15% | |

| 3 | 11c, R = Cl, 65% | |

| 4 |

|

11d, 94% |

| 5 |

|

11e, R = Me, 80% |

| 6 | 11f, R = OMe, 83% | |

| 7 | 11g, R = F, 80% | |

| 8 | 11h, R = Cl, 87% | |

| 9 | 11i, R = Br, 85% | |

| 10 |

|

11j, 82% |

Isolated yields.

Determined by 1H NMR using methyl benzoate as an internal standard.

Diastereoselective decarboxylative functionalizations have also been explored (eq. 2). Here, stereochemically pure (thio)silyl ketene acetal (12) couples with phenylglycine to provide thioester 13 in good yield with modest stereoselectivity (70% yield, 4:1 dr).

|

(2) |

In order to carry out a true amino acid homologation, we sought to transform the N-PMP protected β-amino ester products 9a and 11a into synthetically useful derivatives 14 and 15, respectively (eq. 3). These transformations were accomplished in high yields by using CAN to promote cleavage the PMP group,25 thereby delivering the corresponding products of direct amino acid homologation (14 and 15).

|

(3) |

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that sequential quinone-catalyzed oxidative decarboxylation/Mukaiyama–Mannich addition provides an efficient method for α-amino acid homologation under mild reaction conditions (20 substrates, 15–95% yield). By employing different silyl ketene acetal nucleophiles, a variety of β-amino ester derivatives can be readily prepared. Notably, this is the first example of quinone-catalyzed C–C bond cleavage, a reaction that represents a significant departure from biochemical transformations that utilize quinone cofactors to convert α-amino acids into the corresponding α-keto acids. Future work will focus on the development of quinone catalysts that will address current limitations in the substrate scope.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the NSF (EPS-0993806) and The University of Kansas is gratefully acknowledged. Additional support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health Graduate Training Program in Dynamic Aspects of Chemical Biology Grant T32 GM08545 from NIGMS (to B. J. H.). Support for NMR instrumentation was provided by NIH Shared Instrumentation Grants No. S10OD016369 and S10RR024664, and NSF Major Research Instrumentation Grant No. 0320648. We thank Dr. Justin Douglas for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- 1.For a related review, see: Cheng RP, Gellman SH, DeGrado WF. Chem Rev. 2001;101:3219. doi: 10.1021/cr000045i.

- 2.Stephens OM, Kim S, Welch BD, Hodsdon ME, Kay MS, Schepartz A. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13126. doi: 10.1021/ja053444+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For selected reviews, see: Juaristi E, Soloshonok VA. Enantioselective Synthesis of β-Aminoacids. 2. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2005. Bandala Y, Juaristi E. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2009. p. 291.Sleebs BE, Van Nguyen TT, Hughes AB. Org Prep Proced Int. 2009;41:429.Weiner B, Szymanski W, Janssen DB, Minnaard AJ, Feringa BL. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1656. doi: 10.1039/b919599h.Chhiba V, Bode M, Mathiba K, Brady D. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2014. p. 297.

- 4.For selected recent examples, see: Cheng J, Qi X, Li M, Chen P, Liu G. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2480. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00719.Faulkner A, Scott JS, Bower JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:7224. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03732.

- 5.(a) Arndt F, Eistert B. Ber dtsch Chem Ges. 1935;68:200. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ellmerer-Mueller EP, Broessner D, Maslouh N, Tako A. Helv Chim Acta. 1998;81:59. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kowalski CJ, Haque MS, Fields KW. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:1429. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolbe H. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem. 1860;113:125. [Google Scholar]

- 8.For selected examples, see: Guichard G, Abele S, Seebach D. Helv Chim Acta. 1998;81:187.Yang H, Foster K, Stephenson CRJ, Brown W, Roberts E. Org Lett. 2000;2:2177. doi: 10.1021/ol006146k.Cesar J, Sollner Dolenc M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:7099.Gray D, Concellón C, Gallagher T. J Org Chem. 2004;69:4849. doi: 10.1021/jo049562h.Koch K, Podlech J. Synth Commun. 2005;35:2789.Hughes AB, Sleebs BE. Helv Chim Acta. 2006;89:2611.Pinho VD, Gutmann B, Kappe CO. RSC Adv. 2014;4:37419.

- 9.For selected examples of decarboxylative functionalization of amino acid derivatives, see: Paradkar VM, Latham TB, Demko DM. Synlett. 1995:1059.Laval G, Golding BT. Synlett. 2003:542.Burger EC, Tunge JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10002. doi: 10.1021/ja063115x.Noble A, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:11602. doi: 10.1021/ja506094d.Zuo Z, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5257. doi: 10.1021/ja501621q.Zuo Z, Cong H, Li W, Choi J, Fu GC, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:1832. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13211.

- 10.(a) Corey EJ, Achiwa K. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:1429. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mure M, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:7117. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mure M, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8698. [Google Scholar]; (d) Mure M, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8707. [Google Scholar]

- 11.For selected reviews see: Klinman JP. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27189.Mure M. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:131. doi: 10.1021/ar9703342.

- 12.(a) Largeron M, Fleury MB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:5409. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wendlandt AE, Stahl SS. Org Lett. 2012;14:2850. doi: 10.1021/ol301095j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yuan H, Yoo WJ, Miyamura H, Kobayashi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:13970. doi: 10.1021/ja306934b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.For a related example involving the aerobic oxidation of secondary amines, see: Wendlandt AE, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:11910. doi: 10.1021/ja506546w.

- 14.For a relevant review, see: Wendlandt AE, Stahl SS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:14638. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505017.

- 15.Related amino acid decarboxylations have been observed in stoichiometric reactions that enable the synthesis of benzoxazoles from amino acids and ortho-quinones, see: Vander Zwan MC, Hartner FW, Reamer RA, Tull R. J Org Chem. 1978;43:509.Vinsova J, Horak V, Buchta V, Kaustova J. Molecules. 2005;10:783. doi: 10.3390/10070783.

- 16.For a selected review: Eliot AC, Kirsch JF. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074021.

- 17.Leon MA, Liu X, Phan JH, Clift MD. Eur J Org Chem. 2016;26:4505. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Iimura S, Nobutou D, Manabe K, Kobayashi S. Chem Commun. 2003:1644. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hamada T, Manabe K, Kobayashi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7768. doi: 10.1021/ja048607t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For results of quinone catalyzed oxidative decarboxylation of natural amino acids, see supporting information.

- 20.For studies involving other quinone catalysts, see the supporting information.

- 21.For a selected review on Mannich reactions, see: Kobayashi S, Mori Y, Fossey JS, Salter MM. Chem Rev. 2011;111:2626. doi: 10.1021/cr100204f.

- 22.For selected Mannich-type reactions with tetrafluoroboric acid, see: Akiyama T, Takaya J, Kagoshima H. Adv Synth Catal. 2002;344:338.Yamanaka M, Itoh J, Fuchibe K, Akiyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6756. doi: 10.1021/ja0684803.

- 23.Eliel EL, Wilen SH, Mander LN. Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds. Wiley; New York: 1994. p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mock WL. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:7610. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onodera G, Toeda T, Toda N-n, Shibagishi D, Takeuchi R. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:9021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.