Abstract

Herein, we report a new approach to bio-inspired catalyst design are reported. The molecular catalyst employed in these studies is based on the robust and selective Re(bpy)(CO)3Cl-type (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine) homogeneous catalysts which have been extensively studied for their ability to reduce CO2 electrochemically or photochemically in the presence of a photosensitizer. These catalysts can be highly active photocatalysts in their own right. In this work, the bipyridine ligand was modified with amino acids and synthetic peptides. These results build on earlier findings wherein the bipyridine ligand was functionalized with amide groups to promote dimer formation and CO2 reduction by an alternate bimolecular mechanism at lower overpotential (ca. 250 mV) than the more commonly observed unimolecular process. The bio-inspired catalysts were designed to allow for the incorporation of proton relays to support reduction of CO2 to CO and H2O. The coupling of amino acids tyrosine and phenylalanine led to the formation of two structurally similar Re catalyst/peptide catalysts for comparison of proton transport during catalysis. This article reports the synthesis and characterization of novel catalyst/peptide hybrids by molecular dynamics (MD simulations of structural dynamics), NMR studies of solution phase structures, and electrochemical studies to measure the activities of new bio-inspired catalysts in the reduction of CO2.

Introduction

Global energy consumption continues to increase with the concomitant depletion of petrochemical fuel sources.1 The need for sustainable energy sources continues to generate interest in the development of alternative energy production and storage methods.2–9 The electrochemical reduction of CO2 to liquid fuels or fuel precursors is an attractive route since it could potentially complete a carbon neutral fuel cycle and some of the reduction products are capable of being used directly as fuels.1 While the incorporation of proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) is important for overcoming the relatively high energy thermodynamic energy requirements for the multiproton and multielectron reduction of CO2, the kinetic penalties associated with higher-order reduction products make these transformations challenging for small molecule catalysts.2,10–12

Advances in the area of CO2 reduction have been focused on the production of small molecules such as CO,13–15 formate/formic acid,13,14 and oxalate16. The two-electron/two-proton reduction of CO2 to CO and H2O has garnered particular interest because of the utility of CO as a precursor to liquid fuels useful to the current energy infrastructure through the Fischer-Tropsch process.17 Small molecule electrocatalysis offers a way to tune the redox potentials and selectivity of catalysts in a way not possible with heterogeneous materials through the identification of key mechanistic intermediates and structure/reactivity relationships.1,18 Several homogeneous electrocatalysts based on transition metals have been studied in the past few decades for their ability to reduce CO2 to CO.16,19–23 Of particular interest are the robust photo- and electrocatalysts of the type Re(bpy)(CO)3Cl (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine), which have been shown to efficiently and selectively reduce CO2 to CO.1,22,24,25 This catalyst shows increased activity when electron-donating tert-butyl groups are introduced at the 4 and 4′- positions of bpy.15,26 They also have higher turnover frequencies (TOF) with the addition of weakly acidic Brønsted or Lewis acids in solution and are selective for the reduction of CO2 over the thermodynamically preferred product, H2.11,27 Accordingly, appending proton sources directly to the backbone of the catalysts has been proven a successful method for improving activity, while not impeding the selectivity, for the proton-dependent reduction of CO2 to CO by these rhenium-based electrocatalysts.27,28

The joining the proton source with the catalyst in a single molecule is congruent with the evolutionary adaption of reductive metalloenzymes. For example, two metalloenzymes capable of catalyzing the reduction of CO2 are carbon monoxide dehydrogenases and formate dehydrogenase, both of which show high TOF (> 10,000 s−1) and operate at near thermodynamic potentials (<100 mV from the E0 for their respective reactions).30–32 The structures of these proteins place active sites in a higher-order structure capable of shuttling substrate and products to and from the active sites while excluding solvent molecules, leading to greater catalytic efficiency. Our long-term goal is to develop smaller, biomimetic catalysts that recapitulate these capabilities and advantages.

Indeed, bio-inspired modification of small molecule electrocatalysts has been investigated in recent years in a variety of systems.33 Some work sought to replicate active sites in small molecules; for example, Helm et al. have synthesized electrocatalysts that incorporate pendent bases to facilitate acid-base chemistry during catalysis yielding on of the most active proton reduction catalysts to date.34 Other work has focused on incorporating proton sources directly into the ligand framework.33,35 Previously, we have shown that the use of hydrogen-bonding motifs and amino acid residues can switch the dominant catalytic pathway for CO2 reduction from a unimolecular one to a bimolecular one.36 This change lowers the observed catalytic potential by ~250 mV. Further improvement in activity is observed when proton sources are incorporated into the ligand backbone.37

Here, we report the syntheses and catalytic activity of a series of rhenium-bipyridyl catalyst derivatives, which feature new hydrogen-bonding motifs capable of promoting supramolecular assembly in solution, containing local proton sources, and are amenable to standard solid phase on-resin peptide synthetic (SPPS) techniques. To accomplish this, we began by investigating a Re(bpy) catalyst modified with a single acetamidomethyl group to compare with previous results on di-functionalized complexes. Subsequent investigations focused on the development of a non-natural catalyst-containing amino acid that was stable with respect to peptide synthetic conditions before synthesizing a pentameric peptide as the initial catalyst-peptide hybrid.

Results and Discussion

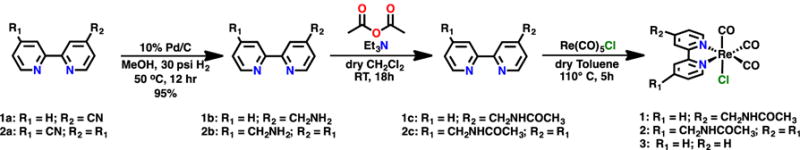

1. Simplest peptide mimic is capable of hydrogen-bonding to alter mechanism

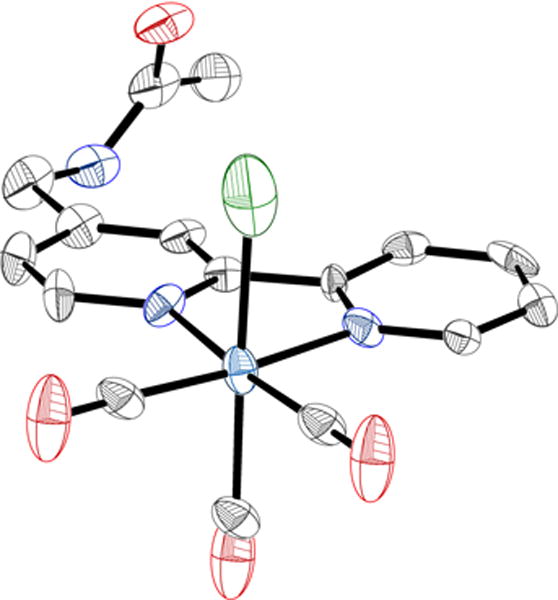

The Re(bpy)(CO)3Cl catalyst was altered to contain the most basic element of peptide bonds: a single amide group. The acetoamidomethyl group was substituted at the 4-position of bpy for complex 1 and compared to the previously reported symmetrically di-substituted analogue 2 (Scheme 1).36 The symmetrically and asymmetrically nitrile-substituted bpy ligands (1a and 2a) were hydrogenated to afford the aminomethyl- substituted ligands (1b and 2b) via an identical procedure (eExperimental Section). The aminomethyl groups were then acylated with acetic anhydride to form the acetoamidomethyl-containing ligands. Subsequent metalation with Re(CO)5Cl in anhydrous toluene generated complexes 1 and 2.36 Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by vapor diffusion of pentanes into a solution of complex 1 in dichloromethane (Figure 1). The molecular structure obtained from these diffraction studies was in agreement with all other characterization methods and in agreement with that proposed in Scheme 1. The electrochemical catalytic results are reported below.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Re(CO)3(acetamidomethylbpy)Cl and bipyridine analogues.

Figure 1.

Single-crystal X-ray crystallographically determined molecular structure of 1. C = gray, N = blue, O = red, H = white, Cl = green; thermal ellipsoids shown at 50%.

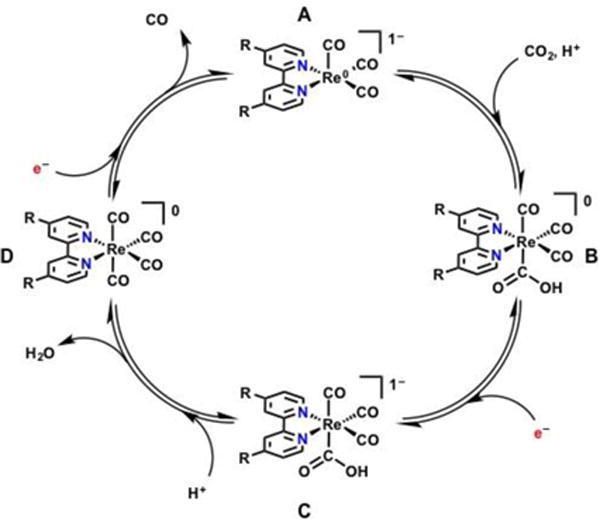

1.1 Single site electrocatalytic mechanism invokes doubly reduced anionic species

To establish context for the catalytic behavior of 1 and the additional amino acid- and peptide-containing complexes described below, it is necessary to review reported mechanisms for electrocatalysis with Re(bpy)-based complexes. The first mechanism is a unimolecular catalytic cycle that invokes a single catalyst active site being reduced by two electrons and subsequently interacting directly with CO2 (Scheme 2). This single-site catalytic scheme is shown in Scheme 238 and is based in part on results obtained by stopped-flow IR experiments and computational methods.39–41 The five-coordinate anion A reacts with 1 equivalent of CO2 and a single proton (H+) to form a hydroxycarbonyl ReI–CO2H species B. Under the applied potential where the anionic five-coordinate A is produced, the most likely pathway from B is predicted to be for a single electron reduction to occur, localized in the bpy ligand, forming a reduced hydroxycarbonyl species C. The increased basicity of O upon reduction in the anionic (ReI–CO2H)− species C (in comparison to B) accelerates protonation and subsequent C–O bond cleavage to generate the tetracarbonyl species D and H2O. The neutral tetracarbonyl species D is a 19 e− species and will rapidly lose 1 equivalent of CO before an additional one electron reduction regenerates the active species, A.

Scheme 2.

The monomeric, electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 invokes a 2-electron reduction of CO2 from one doubly reduced catalyst post halide exchange yielding CO and H2O as products. Adapted from Machan et al.38

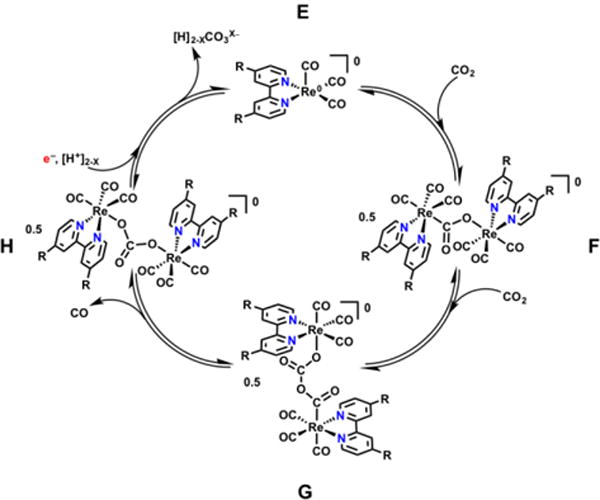

1.2 Bimolecular electrocatalytic mechanism invokes two singly reduced hydrogen-bond bridged catalysts

Previous studies in our laboratory have shown that the use of both methylacetoamidomethyl substituents and acylated amino acid residues at the 4,4′-positions of the Re(bpy)(CO)3Cl catalyst core is sufficient to alter the catalytic mechanism.38 Interestingly, this occurs through formation of a dimeric hydrogen-bonded structure, which is made favorable by the generation of a mixed-valent ReI-Re0 state at the first of four features evident in the cyclic voltammogram (CV).36 The bimolecular mechanism proposed for Re(bpy)-based complexes produces different products compared to the unimolecular mechanism. In particular, two equivalents of CO2 are converted to CO and CO32− through an apparent reductive disproportionation reaction (Scheme 3). This mechanism requires two equivalents of the Re catalyst to each be reduced by one electron to produce the neutral species E and supply the two electrons necessary for the reduction of CO2. A bridging CO2 adduct, F, can then form, followed by the insertion of a second equivalent of CO2 in a head-to-tail fashion to form species G. The extrusion of CO from G, followed by loss of CO32−[H] from H, and further reduction, complete the catalytic cycle for the bimolecular mechanism.42–44 Complex 3 (Figure 1), which does not contain hydrogen-bonding moieties, has been shown to produce H2O as the co-product and were otherwise consistent with the unimolecular mechanism.36

Scheme 3.

The proposed mechanism for the dimeric reduction of CO2 which is second order in catalyst and produces CO32– as a co-product instead of H2O. Adapted from Machan et al.36

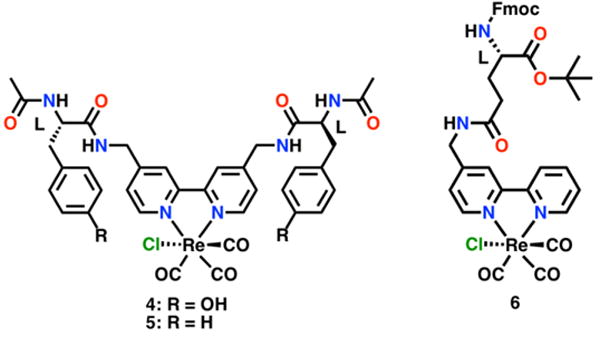

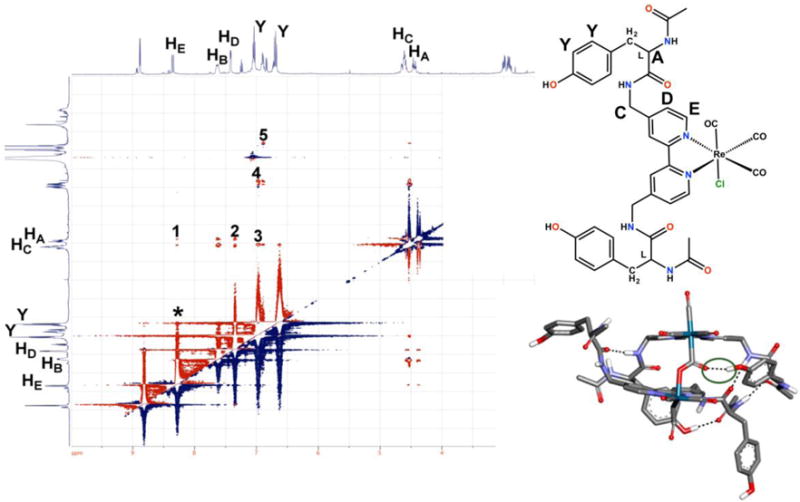

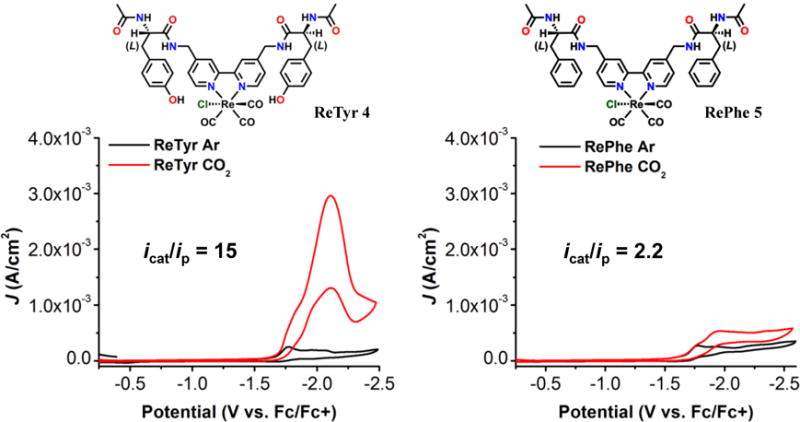

Based on the results obtained with the di-functionalized acetamidomethyl derivatives, we sought to investigate whether pendent amino acid-based proton sources could be incorporated to increase catalytic activity without disrupting the bimolecular mechanism. Previously, evidence of the bimolecular mechanism was observed during investigations of acylated di-tyrosine (di-Try) (4) and di-phenylalanine (di-Phe) (5) modified catalysts (Figure 2).37 Like the acetamidomethyl-based derivative 1, the catalytic product analysis for 4 and 5 showed CO32− and CO as productsAs mentioned previously, these co-products are indicative of a reductive disproportionation mechanism as seen in Scheme 3..37 Molecular dynamics simulations, 2D NMR experiments, and infrared spectroelectrochemical (IR-SEC) experiments showed evidence of dimerization through hydrogen-bonding interactions. For instance, a through-space ROESY experiment using the Tyr-modified catalyst, 4, suggested a stable configuration on the NMR timescale where the catalyst arm adopted a folded configuration that placed the phenol moiety close to the amide backbone and bpy ligand (Figure 3). This type conformation is relevant to catalytic conditions, where this arrangement would allow the pendent proton source to interact with bound substrate. Consistent with this interpretation, conformations that placed these functional groups in close proximity were observed along the trajectory of microsecond-scale MD simulations for a CO2-bound dimer (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Catalyst-modified amino acid complexes. Compounds 4 and 5 exhibit intra- and inter-molecular hydrogen-bonding and 4 further contains an internal proton source as it features a di-Tyrosine substituent on the bipyridine (di-Tyr).37 Notably 6 is capable of being incorporated into a peptide as it is stable towards common Fmoc SPPS.

Figure 3.

2D ROESY pulsed field gradient NMR experiment of the ReTyr catalyst 4 highlighting the < 6 Å through-space interactions of the side chain to the bipyridine ring on the NMR time scale. Also shown is one of the relevant configurations from MD simulations in explicit MeCN with hydrogen bonds shown by dotted lines. Adapted from Machan et al.37

Our prior report on 4 also supported the dimerization mechanism through spectroscopic evidence that suggested the existence of a mixed-valent state37, consistent with CV experiments which estimated a comproportionation constant Kc ~3 times greater than that for 2.36 In this case, the unitless comproportionation constant Kc is measured by the difference in the E0 for the first two of four observed redox features and reflects the stability of the mixed-valent state dimer relative to the two isovalent monomer states; larger values indicate greater stability. The use of N,N-dimethylformamide (N,N-DMF) instead of acetonitrile (MeCN) as a solvent disrupted the bimolecular mechanism in all cases (1, 2, 4, and 5), which is thought to be a consequence of competitive hydrogen bonds between solvent molecules and the catalyst backbone.

An electrocatalytic reaction is expected to have a Nernstian rate dependence proportional to the difference between the applied potential and the thermodynamic potential; a consequence of lowering the applied driving force is often the concomitant lowering of the catalytic rate. As described above, the use of methyl acetamidomethyl groups (1; 2) and simple acylated amino acid residues like Tyr and Phe (4; 5) was found to lower the catalytic potential by changing the mechanism from unimolecular to bimolecular. A continuing challenge for this work is then to match and exceed the rates possible via the unimolecular mechanism that operates at a greater overpotential. Inspired by the success of the Tyr-modified catalyst, 4, in which the phenol side chain of Tyr acted as a pendent proton source, we sought to explore new proton-relay-containing peptide configurations.

1.3 Hydrogen-bonding-capable catalysts reduce CO2 at more positive potentials via bimolecular mechanism

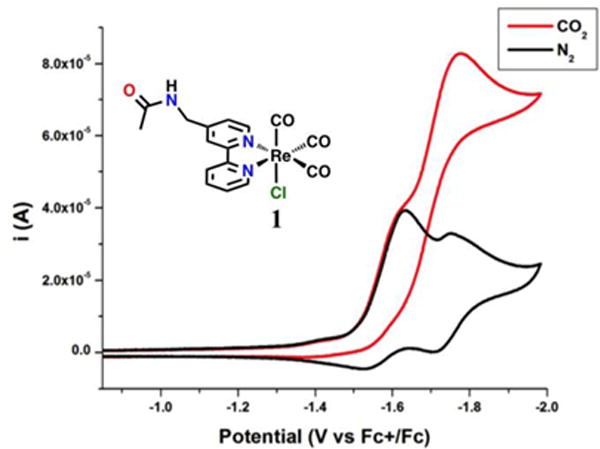

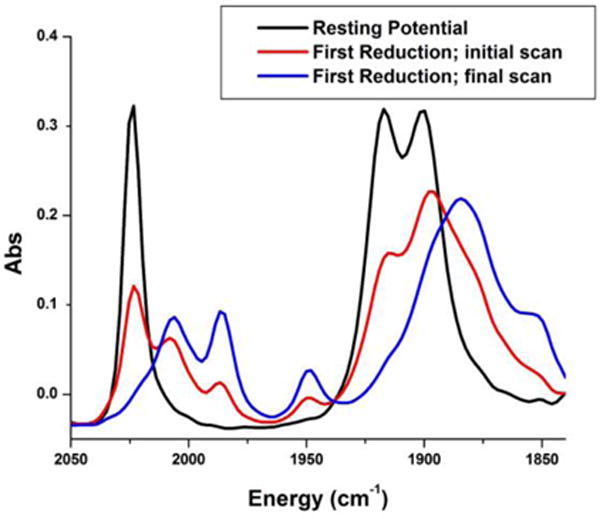

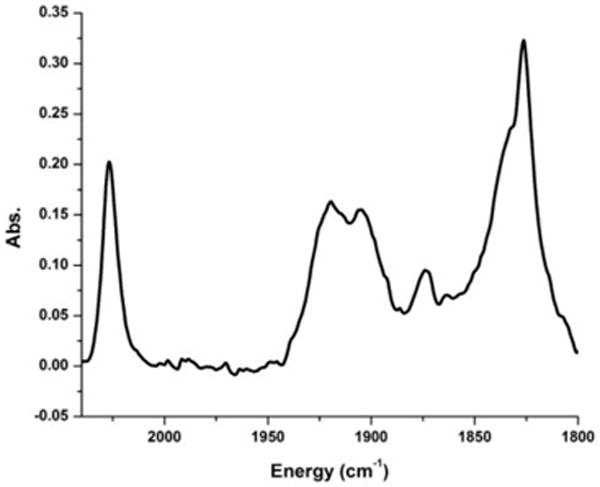

Invoking the bimolecular mechanism templated by hydrogen-boding groups, complex 1 was investigated electrochemically for the catalytic reduction of CO2. In the CV, two single-electron reduction waves were observed (–1.64 V and –1.76 V vs Fc/Fc+) for 1 that were at more positive potentials than those of the control complex 3 (–1.85 V, –2.20 V vs Fc/Fc+) (Figure 5).36 This shift in the observed potentials in MeCN solution for 1 is evidence of the bimolecular pathway.36 Catalytic current was observed under CO2 saturation conditions at an analogous potential (Ep = –1.76 V vs Fc/Fc+) to that observed previously for 2 (Ep = –1.88 V vs Fc/Fc+).36 Indeed, subsequent IR-SEC experiments showed that when the cell potential was set to the potential of the first reduction observed by CV (~–1.8 V vs Fc/Fc+), spectroscopic features consistent with the metal-metal Re0–Re0 dimer are observed (1985, 1948, 1896, 1885, and 1851 cm−1; Figure 6). For reference, the Re0–Re0 dimer of 2 generated during IR-SEC was found to have IR-active carbonyl modes at 1984, 1942, 1875, 1865, and 1842 cm−1; notably, the amide IR mode in 2 shifted from 1685 cm−1 at resting potential to two new bands at 1675 and 1668 cm−1, consistent with a hydrogen-bonding interaction.36

Figure 5.

CV of 1 in acetonitrile under gas saturation conditions with nitrogen (black) and carbon dioxide substrate (red). Conditions: 0.1 M TBAPF6/MeCN; 1 mM complex glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode; 100 mV/s. Referenced to internal ferrocene.

Figure 6.

IR-SEC of 1 in MeCN. At less negative potentials than the first reduction potential observed (–1.65 V vs Fc/Fc+ in the CV) (black) bands consistent with a pseudo-C3v octahedral fac-rhenium tricarbonyl species are observed. Holding the potential at (–1.64 V), the first reduction (red) quickly passes the single reduced species and instead generates a species consistent with a Re0–Re0 dimer at (1985, 1948, 1896, 1885, and 1851 cm−1) (blue) within ~1 minute. Conditions: 0.1 M TBAPF6/MeCN; 1 mM catalyst. glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, bare metal Ag+/Ag pseudoreference electrode.

2. Single amino acids can be utilized to incorporate simple proton relay functions into the catalyst

After determining the effect peptide bonds had on catalysis, the next step was to develop synthetic methods for integrating peptide-length amino acids into the catalyst backbone. The first step was to develop a starting material amenable to hand-coupling methods (by manual or automated synthesis) to make the synthetic procedure generalizable. As the amino acid count increases in peptide sequences, the possible peptide-catalyst conformations increase exponentially. Therefore, choice of sequence may be important for further development and optimization, leading to a need for this kind of generalizable method.

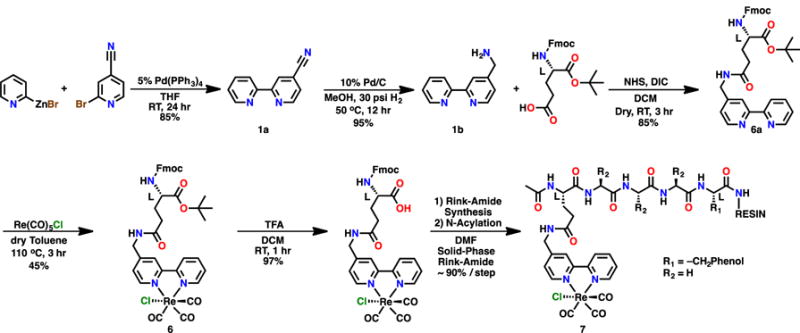

The asymmetrically modified bpy was synthesized from two different halogenated pyridine rings via a high-yielding Negishi coupling reaction (85%).45 The resulting mono-nitrile substituted catalyst was reduced to a methylamine in a heterogeneous mixture of palladium on carbon in methanol pressurized in a Parr reactor to 30 psi H2 over 3 days. The desired 4-aminomethyl-bpy product was purified from the crude reaction mixture by acid-base extraction techniques and used immediately. Using monoamine 1b it is possible to incorporate a wide variety of bio-reminiscent functional groups through condensation and carbodiimide coupling reactions, achieving the goal of a generalizable method. To synthesize the catalyst-containing amino acid, the compound 1b was attached to the side chain of a protected glutamic acid in an N-hydroxysuccinimide-assisted carbodiimide coupling involving the terminal primary amine at the 4-position on the bpy ligand. The side chain was modified so that the non-natural catalyst-containing amino acid would have minimal effects on the synthesis of peptides at the C- and N- termini. Following metalation with Re, this non-natural catalyst-containing amino acid (6) was then electrochemically and spectroscopically investigated (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Full synthetic scheme of catalyst-containing amino acid 6 capable of being incorporated into Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis and pentameric polypeptide catalyst (7) containing active catalyst and weak Brønsted acid source via incorporated tyrosine.

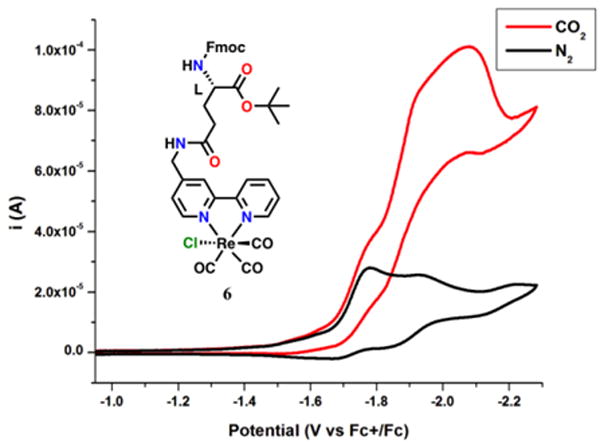

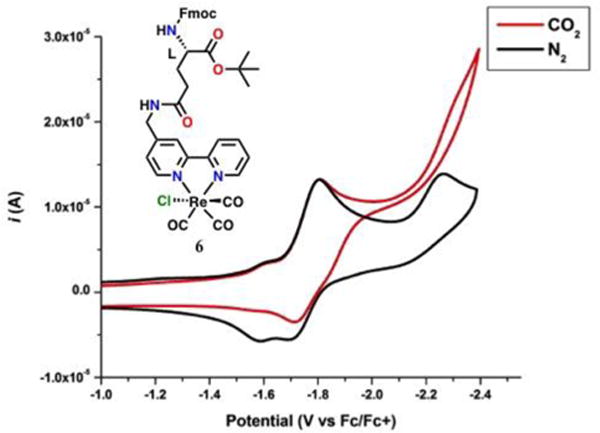

The CV of 6 revealed multiple redox features (–1.78 V, –1.95 V and –2.20 V vs Fc+/Fc; Figure 7). The first two features were assigned to the an initial reduction localized on the bpy ligand of 6, followed by the reduction of the mixed-valent hydrogen-bonded-dimeric species generated in situ, as was seen in the previously described bimolecular mechanism.36 Under CO2 saturation conditions, catalytic current was observed at the second of these reduction features (Ep = –1.95 V vs Fc/Fc+), which is diagnostic of the bimolecular mechanism. As was described previously, this mechanism could be disrupted by repeating the CV’s in N,N-DMF (Figure 8), reverting to only two redox features at –1.78 V and –2.22 V (vs Fc/Fc+). Similarly, under CO2 saturation in N,N-DMF, catalytic current was observed at the second potential (Ep = –2.22 V vs Fc/Fc+), a shift of approximately 270 mV from otherwise identical conditions in MeCN. This is consistent with altering the catalytic pathway from the hydrogen bond-assisted bimolecular reduction of CO2 in MeCN to the unimolecular mechanism in the hydrogen bond-disrupting solvent N,N-DMF.

Figure 7.

CV of 6 in MeCN in saturation conditions with nitrogen (black) and carbon dioxide substrate (red). Conditions: 0.1 M TBAPF6/MeCN; 1 mM complex glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag/AgCl pseudoreference electrode; 100 mV/s. Referenced to internal ferrocene standard.

Figure 8.

CV of 6 in N,N-DMF in saturation conditions with nitrogen (black) and carbon dioxide substrate (red) showing the change in the second reduction potential to more negative potentials versus CV’s in MeCN. Conditions: 0.1 M TBAPF6/N,N-DMF; 1 mM complex glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag/AgCl pseudoreference electrode; 100 mV/s. Referenced to internal ferrocene standard.

3. The catalyst-containing amino acid is amenable to SPPS and when incorporated into a peptide, retains catalytic activity

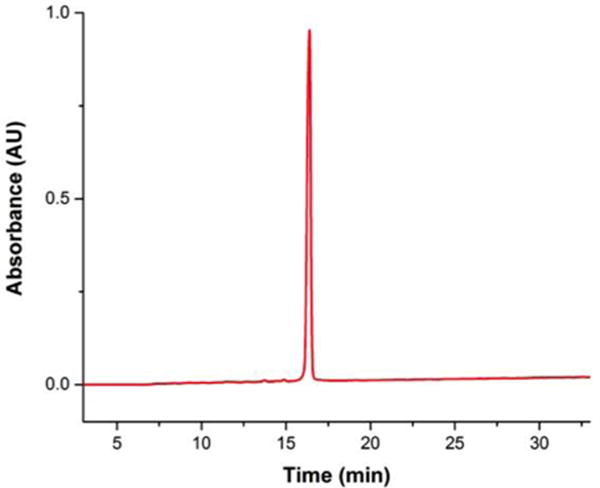

The non-natural glutamic acid described above can be used a precursor for the synthesis of various peptides in a fashion that is modular. As a starting point, we explored a pentameric sequence to test if the electrocatalyst could survive SPPS conditions and to see if the flexibility of the amino acid sequence had an effect on catalytic activity when placed between the electrocatalyst and a pendent proton source. The initial sequence synthesized by standard Fmoc SPPS using a Rink-amide resin was YAAA-6-N-Acyl.46 The C-terminal residue is a Tyr which contains a phenolic proton on its side chain and the N terminal residue is the non-natural glutamic acid that contains the catalyst (6) with the N-terminal amine having been capped with an acyl group. The peptide was synthesized by first swelling the resin in DMF and removing the Fmoc protecting group with 4-methyl piperidine. The peptide was synthesized by coupling the carboxylic acid terminus to the N-terminus on the resin. The amino acids were activated with HATU prior to addition in excess with respect to the DMF swelled resin. Between each coupling, the resin was washed with DMF and subjected to Fmoc deprotection conditions to reveal the free amine for further coupling. The final amino acid for each sequence was the non-natural glutamic acid containing the catalyst (6). It was first dissolved in a trifluoroacetic acid (TFA):DCM mixture (9:1) for 15 minutes to remove the o-tert-butyl protecting group and generate a free carboxylic acid for coupling. The catalyst-containing non-natural amino acid was then precipitated with diethyl ether and washed with excess water and diethyl ether to yield a yellow crystalline powder. The deprotected catalyst amino acid was then prepared the same way the natural amino acids were for incorporation into solid phase peptide synthesis. After coupling, the peptide was N-terminally acylated with acetic anhydride and the completed peptide cleaved from the resin with TFA. Subsequent addition of diethyl ether precipitated a solid with the catalyst-containing pentameric peptide 7 (Scheme 4). The isolated solid 7 was purified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a gradient 25:75 to 40:60 of MeCN:Water (0.1% TFA) on a preparative C12 column (Figure 9). The peptide could be characterized by NMR, and solution IR characterization showed the broad bands for the rhenium fac-tricarbonyl core at 2027, 1920, and 1903 cm−1 (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Analytical HPLC trace of 7 monitored at 214 nm in a gradient of 25 to 40 % MeCN in water(0.1%TFA) over 30 minutes.

Figure 10.

IR of the peptide 7 showing the rhenium tricarbonyl core. The three higher frequency modes are consistent with the rhenium tricarbonyl core (2027, 1920, and 1903 cm−1) while the lower frequency modes are attributed to the other carbonyls in the peptide backbone.

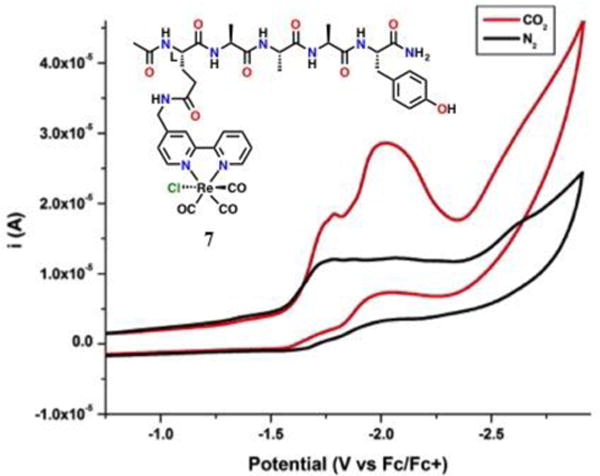

Catalyst 7 was investigated electrochemically in MeCN: several broad redox features were observed by CV at –1.75 V, –2.05 V and –2.60 V vs Fc/Fc+ (Figure 11). Under CO2 saturation conditions, an increase in current was obtained at several redox features, consistent with a catalytic current response. The multiple catalytic waves observed for 7 suggest that under these conditions both the unimolecular and bimolecular mechanisms are operative. Indeed, catalytic Ep was predominantly observed at two potentials: –1.75 V and –2.05 V vs Fc/Fc+, which is consistent with a bimolecular and unimolecular catalytic response, respectively. The catalyst precipitated on the electrode under all conditions, preventing accurate spectroelectrochemical measurements and controlled potential electrolysis experiments to determine efficiency. To further understand this behavior, especially the comparison to the Tyr-modified catalyst, we next examined the catalyst by experimental 2D NMR and computational methods.

Figure 11.

CV of 7 in acetonitrile in saturation conditions with nitrogen (black) and carbon dioxide substrate (red). Conditions: 0.1 M TBAPF6/MeCN; 0.25 mM complex glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag/AgCl pseudoreference electrode; 100 mV/s. Referenced to internal ferrocene standard.

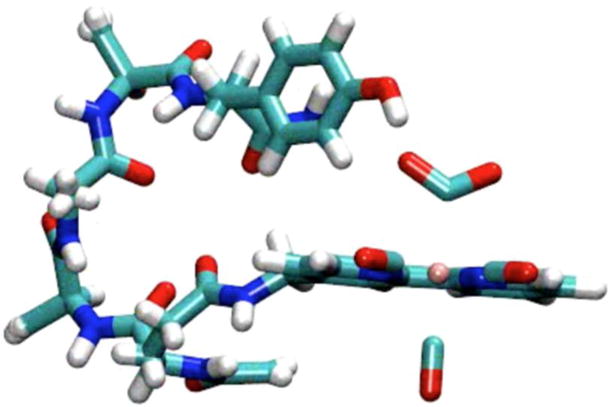

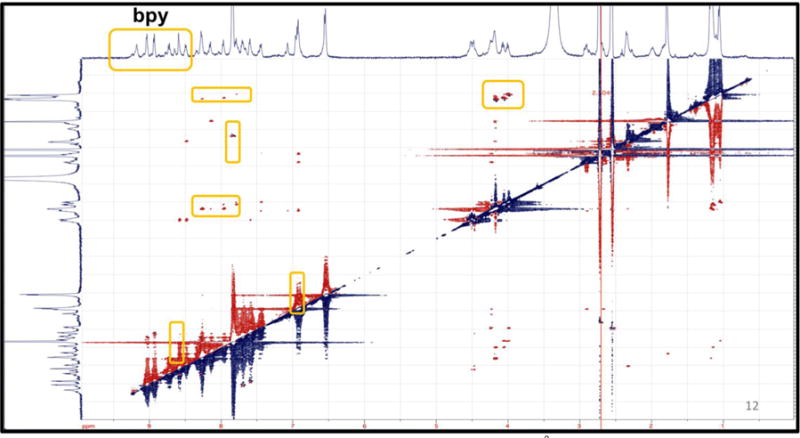

A snapshot (Figure 12) taken from the trajectory of the 100 ns MD simulation of 7 in explicit MeCN shows that interactions between the catalyst core and pendent amines are possible and may be templated by internal hydrogen-bonding. Similarly to the case of 4, ROESY 2D NMR evidence supports the existence of related conformations on the NMR timescale. The crosspeaks highlighted in Figure 13 identify how the bipyridine interacts with the furthest amino acid containing the proton source (tyrosine), which is consistent with a conformation similar to that shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Snapshot of MD simulation of 7 reduced by a single electron in explicit MeCN. Simulation may show internal hydrogen-bonding. Species is a CO2 bound anionic non-radical state.

Figure 13.

2D ROESY NMR experiment highlighting < 6Å through space interactions between the backbone amines and the bipyridine ligand.

Unfortunately, the catalytic activity observed for 7 did not represent a significant improvement over that observed for 6. This may be, in part, the result of slower diffusion times for 7 (1.54 × 10−5 cm/s) versus 9.8 × 10−6 for 6 in MeCN solution; as determined by DOSY NMR. Because of the large parameter space enabled by a pentameric peptide sequence, we are currently exploring additional structures to further understand the relevant design principles.

Conclusions

The results described here summarize attempts to optimize the rate of electrochemical CO2 reduction for Re(bpy)-based catalysts by probing proton-relay-containing peptide configurations as part of the ligand backbone. Electrochemical experiments, supplemented by 2D NMR and MD simulations, indicate that at a length of five amino acids, the peptide backbone can adopt conformations with intramolecular interactions on the NMR timescale. Experimental results suggest that this alters catalysis from the symmetrically modified system, allowing both the unimolecular and bimolecular mechanisms to operate on the CV timescale. Further studies exploring this hypothesis to optimize catalytic rate are ongoing.

Hydrogen-bonding was shown to be mechanistically relevant for the short peptide-bond-mimicking sequence synthesized in this report. The single acetamidomethyl moiety in catalyst 1 was enough to form a hydrogen-bond-bridged dimeric catalyst structure on the CV timescale, thereby altering the pathway for CO2 reduction from unimolecular to bimolecular with concomitant lowering of the overpotential. To probe the role of hydrogen-bonding and proton relays in structures with larger ligand backbones, the catalyst was then incorporated into a pentameric peptide structure to expand on prior results obtained using single amino acids as simple proton relays. For this purpose, the side chain of a protected glutamic acid (Glu) was modified with a Re-based CO2 reduction electrocatalyst and determined to be stable with respect to peptide synthesis conditions and its electrochemical properties were investigated. Importantly, this approach enables electrocatalyst attachment at arbitrary points in an amino acid sequence. Studies to explore new configurations and sequences are ongoing.

Experimental

General

1H and 13C{1H} (1D and 2D) NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz or 500 MHz Varian spectrometer at 298 K and referenced to solvent shifts. Data manipulations were completed using MestReNova, ACD, or iNMR software. Infrared spectra were taken on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700 or a Bruker Equinox 55 spectrometer. HPLC was performed on Jupiter 4u Proteo 90A Phenomenex column (150 × 4.60 mm) with a binary gradient using a Hitachi-Elite LaChrom L-2130 pump equipped with a UV-Vis detector (Hitachi-Elite LaChrom L-2420). ESI-MS data obtained at the UCSD Molecular Mass Spectrometry facility. Microanalyses were performed by NuMega Resonance Labs or Midwest Microlabs for C, H, and N.

Solvents and chemicals

All solvents were obtained from Fisher Scientific. Dry solvents were dried in house by storing in a moisture free environment and dried on a custom drying system running through two alumina columns prior to use. All compounds were obtained from Fisher Scientific or Sigma-Aldrich and used as obtained unless otherwise specified. 4,4′-dicyano-2,2′-bipyridine was obtained from HetCat and used without further purification. Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6, Aldrich, 98%) was recrystallized from CH3OH twice and dried at 90°C overnight before use in electrochemical experiments.

Computational Methods

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were carried out with the Gromacs 4.6 software package47 using explicit MeCN or N,N-DMF solvent at 298 K. All bonded and non-bonded parameters that do not involve a rhenium element were assigned from the General Amber Force Field48. Quantum methods were used to optimize the dimer structure and generate bonded parameters involving central rhenium atom. Non-bonded parameters for rhenium in the octahedral configuration were obtained from the Universal Force Field49. Partial atomic charges were derived by fitting the electrostatic potential produced by quantum calculations using the restrained electrostatic potential approach50. Restraints were placed on the angles of O–C–Re to maintain the proper positions of the carbonyl groups.

Quantum calculations were carried out in the Gaussian 09 program51 using the pure density functional theory (DFT) functional M06-L52 in conjunction with the conductor-like polarizable continuum model53. Restricted wave functions RM06-L were employed for closed shell systems and unrestricted theory UM06-L was employed for open-shell systems. The 6-31++G(d,p) Pople basis set was selected for all the light atoms (H, C, N, O, and Cl), and the LANL2DZ (Los Alamos National Laboratory 2 double ζ) effective core potential (ECP) as well as the corresponding basis set were used on the rhenium center.

Synthetic Methods

Re(4,4′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine)(CO)3Cl (3) was prepared according to literature procedure.2 Re(4,4′-bis(acetoamidomethyl)-2,2′-bipyridine)(CO)3Cl (2), and aminomethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (1b) were prepared according to literature procedures45,54 All peptide synthesis was done using standard Fmoc peptide synthesis techniques.46 Tyrosine (4) and Phenylalanine (5) modified rhenium catalysts were synthesized via previously published techniques.37

4-methylacetoamidomethyl-2,2′-bipyridine, 1c

A round-bottom flask was charged with 4-aminomethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (1.0 g, 5.4 mmol) and triethylamine (0.20 mL, 1.4 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (250 mL). To this solution, acetic anhydride (0.54 mL, 5.6 mmol) was added dropwise. The reaction was stirred vigorously for 16 hours under an N2 atmosphere. After this time, the reaction was quenched with dilute aqueous Na2CO3 (50 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 100 mL) and CH2Cl2 (2 × 100 mL). The organic layers were combined and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. Incomplete reactions as determined by 1H NMR were loaded onto neutral alumina and purified chromatographically on a Combiflash® silica column with a 0 to 10% CH3OH in CHCl3 gradient over 60 min. The eluent was monitored by UV-Vis at 254 nm and 280 nm for the product. Yield: 0.19 g, 80%. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 400 MHz): δ 8.65 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.58 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.39 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.31 (sh s, 1H, ArH), 7.82 (sh t, 1H, ArH), 7.32 (sh t, 1H, ArH), 7.22 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 6.23 (br s, 1H, ArCH2NHC(O)CH3), 5.32 (s, 2H, CD2Cl2), 4.49 (br mult, 2H, ArCH2NHC(O)CH3), 2.03 (sh s, 3H, ArCH2NHC(O)CH3), 1.25 (br, grease), 0.00 (sh s, TMS). %. 13C {1H} NMR (CD2Cl2, 500 MHz): δ 171.6 (ArCH2NHC(O)CH3), 156.1 (ArCC), 155.9 (ArCC), 149.5 (ArCH), 149.3 (ArCCH2), 149.1 (ArCH), 137.8 (ArCH), 124.4 (ArCH), 123.0 (ArCH), 122.0 (ArCH), 120.1 (ArCH) 53.8 (CD2Cl2), 42.8 (ArCH2NHC(O)CH3), 23.0 (-NHC(O)CH3). ESI-MS (m/z) [M+H]+: Calcd. 228.1. Found: 228.1.

Re(4-methylacetoamidomethyl-2,2′-bipyridine)(CO)3Cl, 1

An oven-dried 100 mL pear-shaped flask with a stir bar was charged with 4-acetoamidomethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (1c) (0.100 g, 0.44 mmol), Re(CO)5Cl (0.170 g, 0.45 mmol), and dry toluene (50 mL) under inert atmosphere (N2). This flask was attached to a reflux condenser and heated to reflux for 4 h during which time the solution turned from white to yellow. When the flask had cooled, solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The resulting yellow solid was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/hexanes at –20 °C to yield a yellow microcrystalline powder. Yield: 0.68 g, 43% 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 500 MHz): δ 9.00 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.90 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.22 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.12 (sh s, 1H, ArH), 8.06 (sh t, 1H, ArH), 7.54 (sh t, 1H, ArH), 7.40 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 6.23 (br s, 1H, ArCH2NHC(O)CH3), 5.32 (s, 2H, CD2Cl2), 4.52 (br mult, 2H, ArCH2NHC(O)CH3), 2.06 (sh s, 3H, ArCH2NHC(O)CH3), 1.52 (sh s, H2O), 0.00 (sh s, TMS). ESI-MS (m/z) [M+Na+]+: Calcd. 556.0. Found: 556.2.

4-(L-Fmoc-glutamic acid-Otbu)-amidmethyl-2,2′-bipyridine, 6a

An oven-dried 500 mL round bottom flask with a stir bar was charged with (L)-4-((((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)-5-(tert-butoxy)-5-oxopentanoic acid (side chain deprotected L-glutamic acid) (2.42 g; 5.7 mmol) and 500 mL CH2Cl2 (DCM). The solution was sparged with N2 and left under an N2 atmosphere for the rest of the synthesis to prevent water from entering the reaction. N-hydroxysuccinimide (0.66 g; 5.7 mmol), diisopropylcarbodiimide (0.9 mL; 5.7 mmol), and triisopropylamine (0.25 g; 1.0 mmol) were dissolved in minimal amounts of DCM and added to the glutamic acid solution whereupon a white precipitated suspended in solution was observed. After 15 minutes of stirring, the 4-aminomethyl-2,2′-bipyridine (1b) (1.0 g, 5.3 mmol) was added in one portion and allowed to react for 2 hours. The product was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 100 mL) and DCM (2 × 100 mL). The organic layers were combined and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. Incomplete reactions as determined by 1H NMR were loaded onto neutral alumina and purified chromatographically on a deactivated Combiflash® silica column (deactivated by washing with triethylamine) with a 0 to 70 % Ethyl Acetate in hexanes gradient over 60 min. The eluent was monitored by UV-Vis at 254 nm and 280 nm for the product. Yield: 2.72 g; 85% 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 8.62 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.59 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.35 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.28 (sh s, 1H, ArH), 7.80 (sh t, 1H, ArH), 7.72 (sh d, 2H, ArH-Fmoc), 7.56 (sh t, 2H, ArH-Fmoc), 7.37 (br t, 2H, ArH-Fmoc), 7.29 (br t, 2H, ArH-Fmoc), 7.27 (sh m, 1H, ArH), 7.26 (sh s, CHCl3), 7.25 (br m, 1H, ArH), 6.68 (br s, 1H, Ar(Fmoc)CH2NHC(O)CH), 5.76 (br d, 1H, ArCH2NHC), 4.53 (sh t, 2H, FmocCH2), 4.37 sh d, 2H, ArCH2NHC(O)CH2–), 4.24 (br t, 1H, FmocCH2NHCHCCH2–), 4.17 (sh t, 1H, FmocHCH2O–), 4.1 (q, EtOAc), 2.33 (br m 2H, –NHCHCH2CH2C(O)–), 2.04 (s, EtOAc), 1.75 (br m –NHCHCH2CH2C(O)–), 1.45 (sh s, 9H, –CH3), 1.25 (t, EtOAc), 0.00 (sh s, TMS). ESI-MS (m/z) [M+Na+]+: Calcd. 593.3. Found: 593.5.

Re[4-(L-Fmoc-glutamicacid-Otbu)-amidmethyl-2,2′-bipyridine](CO)3Cl, 6

An oven-dried 100 mL pear-shaped flask was charged with the bipyridine-modified glutamic acid 6a (264.5 mg, 0.45 mmol), Re(CO)5Cl (162 mg, 0.45 mmol), and dry toluene (25 mL) under inert atmosphere (N2). This flask was attached to a reflux condenser and heated to reflux for 4 h during which time the solution turned from white to yellow. When the flask had cooled, solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The resulting yellow solid was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/hexanes at –20 °C to yield a yellow microcrystalline powder.

Yield: 0.180 g, 45% 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 8.62 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.59 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.28 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.20 (sh d, 1H, ArH), 8.13 (sh s, 1H, ArH), 7.73 (br t, 2H, ArH-Fmoc), 7.54 (br m, 2H, ArH-Fmoc), 7.38 (br m, 4H, ArH-Fmoc), 7.28 (br m, 2H, ArH), 7.26 (sh s, CHCl3), 7.06 (br m, 1H, Ar(Fmoc)CH2NHC(O)CH), 6.93 (br m, 1H, ArCH2NHC), 5.70 (br t, 1H, FmocHCH2O–), 4.45 (br m, 1H, FmocCH2NHCHCCH2–), 4.41 (br d, 2H, FmocCH2), 4.19 (br t, 2H, ArCH2NHC(O)CH2–),2.33 (br m 2H, –NHCHCH2CH2C(O)–), 1.85 (br m 2H, –NHCHCH2CH2C(O)–), 1.56 (s, H2O), 1.46 (sh s, 9H, –CH3), 0.00 (sh s, TMS). ESI-MS (m/z) [M – Cl− + MeOH]+: Calcd. 895.2. Found: 895.6. Elemental Analysis for C39H38Cl3N4O8Re∙(CH2Cl2) Calc’d: C 47.64, H 3.90, N 5.70; Found: C 46.67, H 4.03, N 6.20.

Tyrosine-Alanine-Alanine-Alanine-GluRebpy-Acyl 7

The peptide was synthesized according to standard Fmoc solid phase synthesis techniques46 on a Rink amide resin. All couplings other than the non-natural amino acid containing the catalyst (6) were completed on an AAPPTec Focus XC automated synthesizer. The final coupling of the catalyst was done with the by hand using the same standard techniques as follows. Complex 6 was prepared for coupling by deprotecting the carboxylic acid with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA): DCM mixture (9:1) for 15 minutes to remove the o-tert-butyl protecting group. The complex was then coupled in three portions using a 3-fold excess of catalyst each time in the coupling solution using HATU as the coupling reagent. The final step (after removal of the final N-terminal Fmoc protecting group) was the acylation of the peptide with excess acetic anhydride in DCM. The peptide 7 was removed from the resin in 7 mL of 100% TFA for 15 minutes. The resin was washed with 3mL of TFA and the catalyst containing peptide was precipitated with excess cold ether (100 mL) and allowed to precipitate further overnight in the –20 °C freezer. The peptide was purified by HPLC using a 25 to 40% MeCN in water (with 0.1%TFA). Yield: 0.110 g. ESI-MS (m/z) [M – Cl− + MeCN]+: Calcd. 1001.2. Found: 1002.4.

Electrochemistry

All electrochemical experiments were conducted using a BASi Epsilon potentiostat. A single-compartment, 3-electrode cell was used with oven-dried stir bar and needle to control the atmosphere. A 3 mm diameter glassy carbon (GC) electrode from BASi was employed as the working electrode (WE). The counter electrode (CE) was a platinum (Pt) wire. The reference electrode (RE) was a silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode separated from solution by a Vycor or Coralpor tip. Experiments were run with and without an added ferrocene as an internal standard. All solutions were either in dry MeCN or dry DMF and contained 0.5 to 1 mM of catalyst and 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6) as the supporting electrolyte, unless otherwise noted. Experiments were purged with N2 or CO2 (to saturation at 0.28 M) before CV’s were taken and stirred in between successive experiments. All experiments were reported referenced an internal ferrocene standard except for the bulk electrolysis experiments, which used the pseudo-RE Ag/AgCl behind a Vycor or Coralpor tip.

Infrared Spectroelectrochemistry

The infrared-spectroelectrochemical data was taken in-house via a previously published setup.55,56 For all data presented herein, a Pine Instrument Company model AFCBP1 bipotentiostat was employed. As the potential was scanned, thin layer bulk electrolysis was monitored by Fourier-Transform Reflectance IR off the electrode surface. All experiments were conducted in 0.1 M TBAPF6/MeCN solutions with catalyst concentrations of ~3 mM (unless otherwise noted) prepared under a nitrogen atmosphere. The IR-SEC cells used (working electrode/counter electrode/reference electrode) were GC/Ag/Pt. This resulted in all potentials being referenced to a pseudoreference electrode, bare metal Ag+/Ag (~+200 mV from the Fc+/Fc couple).

X-ray Crystallography

Single crystal X-ray diffraction studies reported herein were carried out on a Bruker Kappa APEX-II CCS diffractometer equipped with MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). The Paratone oil suspended crystals were mounted on a Cryoloop. The data was collected under a stream of N2 gas at 100(2) K using ω and ϕ scans. Data were integrated using the Bruker SAINT software program and scaled using SADABS software. A complete phasing model consistent with the molecular structure was produced by SHELXS direct methods. Non-hydrogen atoms were reined anisotropically by full matrix least squares (SHELXL-97).57 All hydrogen atoms were determined using a riding model with positions constrained to their parent atom using the appropriate FHIX command. Crystallographic data is in supplementary information (Table 1 and .cif file).

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

CVs of 4 and 5 in acetonitrile under saturation conditions with nitrogen (black) and carbon dioxide substrate (red). The increase in current under CO2 saturation conditions in the case of complex 4 is attributed to the phenol acting as a local proton source. Conditions: 0.1 M TBAPF6/MeCN; 1 mM complex, glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode; 100 mV/s. Referenced to internal ferrocene. This figure is adapted from Machan et al.37

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support for this work from the AFOSR through a Basic Research Initiative (BRI) grant (FA9550-12-1-0414). We also would like to thank Prof. Arnie Rheingold and Dr. Curtis Moore for assistance with X-ray crystallographic studies. S.A.C. thanks support from an NSF-GRFP award. We also acknowledge the Molecular Mass Spectrometry Facility at UCSD where the MS-data was obtained. MKG acknowledges funding from National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM61300). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Additional information regarding species synthesized herein, including electrochemical responses, IR-SEC, and crystallographic data is available free of charge online at

Notes:

The authors declare no competing financial interest. MKG has an equity interest in, and is a cofounder and scientific advisor of VeraChem LLC.

References

- 1.Lewis NS, Nocera DG. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:15729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603395103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smieja JM, K CP. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:9283. doi: 10.1021/ic1008363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibrahim HIA, Perron J. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2008;12 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeman F. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:7558. doi: 10.1021/es070874m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stolaroff JKK, W D, Lowry GV. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:2728. doi: 10.1021/es702607w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu K, MKC I, Gabriel J, Tsang SCE. ChemSusChem. 2008;1:893. doi: 10.1002/cssc.200800169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhown ASF, C B. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:8624. doi: 10.1021/es104291d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang TL, S K, Wright A. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:6670. doi: 10.1021/es201180v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costentin CR, M, Saveant J-M. Chem Soc Rev. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benson EE, K CP. Chem Commun. 2012;48:7374. doi: 10.1039/c2cc32617e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smieja JM, B EE, Kumar B, Grice KA, S C, Seu AJMM, Mayer JM, Kubiak CP. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:15646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119863109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinberg DR, Gagliardi CJ, Hull JF, Murphy CF, Kent CA, Westlake BC, Paul A, Ess DH, McCafferty DG, Meyer TJ. Chemical Reviews. 2012;112:4016. doi: 10.1021/cr200177j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolinger CM, Story N, Sullivan BP, Meyer TJ. Inorganic Chemistry. 1988;27:4582. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaplin RPS, Wragg AA. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry. 2003;33:1107. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smieja JM, Kubiak CP. Inorganic Chemistry. 2010;49:9283. doi: 10.1021/ic1008363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angamuthu R, Byers P, Lutz M, Spek AL, Bouwman E. Science. 2010;327:313. doi: 10.1126/science.1177981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balonek CM, Lillebø AH, Rane S, Rytter E, Schmidt LD, Holmen A. Catalysis Letters. 2010;138:8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson EE, Kubiak CP, Sathrum AJ, Smieja JM. Chemical Society Reviews. 2009;38:89. doi: 10.1039/b804323j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smieja JM, Sampson MD, Grice KA, Benson EE, Froehlich JD, Kubiak CP. Inorganic Chemistry. 2013;52:2484. doi: 10.1021/ic302391u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiao J, Liu Y, Hong F, Zhang J. Chemical Society Reviews. 2014;43:631. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60323g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hori Y, Wakebe H, Tsukamoto T, Koga O. Electrochimica Acta. 1994;39:1833. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan BP, Bolinger CM, Conrad D, Vining WJ, Meyer TJ. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1985:1414. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher BJ, Eisenberg R. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1980;102:7361. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar B, Smieja JM, Kubiak CP. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2010;114:14220. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawecker J, Lehn J-M, Ziessel R. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1984;0:328. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grice KA, Kubiak CP. In: Advances in Inorganic Chemistry. Michele A, van Rudi E, editors. Vol. 66. Academic Press; 2014. p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhugun I, Lexa D, Savéant J. -M. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1996;100:19981. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong K-Y, Chung W-H, Lau C-P. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 1998;453:161. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Hagan M, Shaw WJ, Raugei S, Chen S, Yang JY, Kilgore UJ, DuBois DL, Bullock RM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:14301. doi: 10.1021/ja201838x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang V, Ragsdale SW, Armstrong FA. Metal ions in life sciences. 2014;14:71. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reda T, Plugge CM, Abram NJ, Hirst J. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:10654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801290105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Can M, Armstrong FA, Ragsdale SW. Chemical Reviews. 2014;114:4149. doi: 10.1021/cr400461p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dutta A, DuBois DL, Roberts JAS, Shaw W. J Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:16286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416381111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helm ML, Stewart MP, Bullock RM, DuBois MR, DuBois DL. Science. 2011;333:863. doi: 10.1126/science.1205864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azcarate I, Costentin C, Robert M, Savéant J-M. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2016;138:16639. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machan CW, Chabolla SA, Yin J, Gilson MK, Tezcan FA, Kubiak CP. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2014;136:14598. doi: 10.1021/ja5085282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Machan CW, Yin J, Chabolla SA, Gilson MK, Kubiak CP. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2016;138:8184. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Costentin C, Passard G, Savéant J-M. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2015;137:5461. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sampson MD, Nguyen AD, Grice KA, Moore CE, Rheingold AL, Kubiak CP. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2014;136:5460. doi: 10.1021/ja501252f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beley M, Collin JP, Ruppert R, Sauvage JP. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1984:1315. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machan CW, Sampson MD, Chabolla SA, Dang T, Kubiak CP. Organometallics. 2014;33:4550. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sampson MD, Froehlich JD, Smieja JM, Benson EE, Sharp ID, Kubiak CP. Energy & Environmental Science. 2013;6:3748. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keith JA, Grice KA, Kubiak CP, Carter EA. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:15823. doi: 10.1021/ja406456g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benson EE, Sampson MD, Grice KA, Smieja JM, Froehlich JD, Friebel D, Keith JA, Carter EA, Nilsson A, Kubiak CP. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2013;52:4841. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan BP, Bolinger CM, Conrad D, Vining WJ, Meyer TJ. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1985;0:1414. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayashi Y, Kita S, Brunschwig BS, Fujita E. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:11976. doi: 10.1021/ja035960a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agarwal J, Fujita E, Schaefer HF, Muckerman JT. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012;134:5180. doi: 10.1021/ja2105834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fang Y-Q, Hanan GS. Synlett. 2003;2003:0852. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis. Oxford University Press; New York: p. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pronk S, Pall S, Schulz R, Larrson P, Bjelkmar P, Apostolov R, Shirts MR, Smith JC, Kasson PM, van der Spoel D, Hess B, Lindahl E. Bioinformatics. 2013;29 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang JM, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rappe AK, Casewit CJ, Colwell KS, Goddard WA, III, Skiff WM. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10024–10035. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell W, Kollman PA. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Jr, M JA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian, Inc. Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:194101. doi: 10.1063/1.2370993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barone V, Cossi M. J Phys Chem A. 1998;102:1995. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beer PD, Szemes F, Passaniti P, Maestri M. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:3965. doi: 10.1021/ic0499401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Machan CW, Sampson MD, Chabolla SA, Dang T, Kubiak CP. Organometallics. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zavarine IS, Kubiak CP. J Electroanal Chem. 2001;495:106. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sheldrick G. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 2008;64:112. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.