Abstract

Background

Treatment decisions in kidney transplantation requires patients and clinicians to weigh the benefits and harms of a broad range of medical and surgical interventions, but the heterogeneity and lack of patient-relevant outcomes across trials in transplantation makes these trade-offs uncertain, thus, the need for a core outcome set that reflects stakeholder priorities.

Methods

We convened 2 international SONG-Kidney Transplantation stakeholder consensus workshops in Boston (17 patients/caregivers; 52 health professionals) and Hong Kong (10 patients/caregivers; 45 health professionals). In facilitated breakout groups, participants discussed the development and implementation of core outcome domains for trials in kidney transplantation.

Results

Seven themes were identified. Reinforcing the paramount importance of graft outcomes encompassed the prevailing dread of dialysis, distilling the meaning of graft function, and acknowledging the terrifying and ambiguous terminology of rejection. Reflecting critical trade-offs between graft health and medical comorbidities was fundamental. Contextualizing mortality explained discrepancies in the prioritization of death among stakeholders – inevitability of death (patients), preventing premature death (clinicians), and ensuring safety (regulators). Imperative to capture patient-reported outcomes was driven by making explicit patient priorities, fulfilling regulatory requirements, and addressing life participation. Specificity to transplant; feasibility and pragmatism (long-term impacts and responsiveness to interventions); and recognizing gradients of severity within outcome domains were raised as considerations.

Conclusions

Stakeholders support the inclusion of graft health, mortality, cardiovascular disease, infection, cancer, and patient-reported outcomes (ie, life participation) in a core outcomes set. Addressing ambiguous terminology and feasibility is needed in establishing these core outcome domains for trials in kidney transplantation.

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplantation offers many patients with end-stage kidney disease improvements in survival and quality of life that vastly exceed being on dialysis1,2. Globally, 80 000 kidney transplants are performed each year, with most high-income countries achieving a 1-year graft survival rate of more than 95%3–5. Unfortunately, similar success is yet to be seen in long-term graft survival, which remains at 50–70% at 10 years6–10. Also immunosuppression after transplantation is associated with an increased risk of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and infection11–14. Consequently, treatment decisions require patients and clinicians to weigh the risks of mortality, graft survival, medical comorbidities, symptoms, and quality of life.

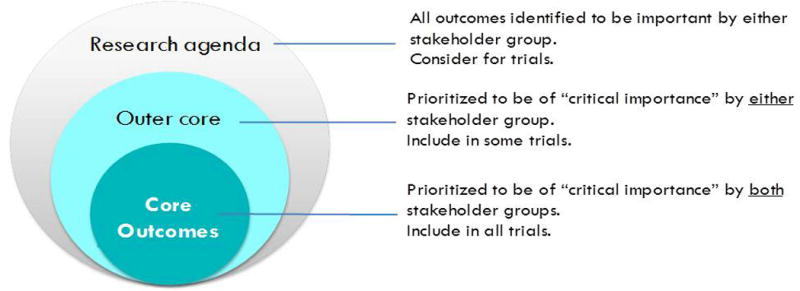

The plethora of outcomes, selective reporting of positive results, and omission of patient-centered outcomes in trials conducted in kidney transplant recipients, and that are mostly short-term15–20, make these trade-offs uncertain. A core outcome set that reflects the priorities of patients and health professionals has been demonstrated to improve the relevance and reliability of clinical trials21–26. A core outcome set is a consensus-based standardized set of outcomes that should be reported, as a minimum, in all clinical trials in a specific area of health27 (Figure 1). Researchers can add outcomes based on other considerations such as responsiveness to the intervention, resource constraints, and regulatory compliance. In the past decade, core outcome sets have been established across many medical disciplines25,27–32, which have improved reporting in trials33.

Figures 1.

Conceptual schema of core outcomes (adapted from OMERACT)

The Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology – Kidney Transplantation (SONG-Tx) was initiated in 2015 and is focused on developing core outcome domains (ie, what to measure) for all trials in kidney transplantation.17 Having completed an international Delphi survey34 to identify critically important outcome domains by all stakeholder groups, a consensus workshop was convened for patients, caregivers and health professionals to review the potential core outcome domains. This workshop report describes stakeholder reflections and deliberations on the core outcomes domains in kidney transplantation, and recommendations for the way forward.

METHODS

Context and scope

Two SONG-Tx consensus workshops were convened: 1 in Boston during the American Transplant Congress (June 13th 2016), and 1 in Hong Kong at The Congress of The Transplantation Society (August 20th 2016). Prior to the workshops, we conducted an online 3-round Delphi survey to identify outcome domains that patients, caregivers and health professionals prioritized as critically important for all trials in kidney transplantation. A brief overview of the SONG-Tx Delphi survey is provided to set the context for the workshop discussion. The full study will be published separately. The Delphi survey included outcome domains reported in trials in kidney transplantation (as identified in our systematic review) and from previous studies with kidney transplant recipients16,35–39. In total, 461 patients/caregivers and 557 health professionals from 79 countries participated. The critically important outcome domains (mean scores 7–9 on a 9-point Likert scale) common to both groups were: graft loss, graft function, acute rejection, chronic rejection, death, infection, cancer (nonskin), cardiovascular disease, skin cancer, and ability to work.

Participants and contributors

We invited patients and caregivers with current or previous experience of kidney transplantation, and health professionals (physicians [nephrologists, surgeons, and psychiatrists], nursing and allied health professionals, researchers, regulators, and industry representatives) with expertise in kidney transplantation. To maximize potential for dissemination and implementation, we also invited key decision-makers in professional societies (eg, The Transplantation Society, American Society of Transplantation, American Society of Transplant Surgeons, Asian Society of Transplantation, British Transplant Society, European Society of Transplantation, and the Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand); regulatory agencies (eg, Food and Drug and Administration [FDA], Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]), funding organisations (eg, National Institutes for Health [NIH]), guideline organisations (eg, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes), renal registries, and editorial roles in transplantation journals.

In total, 69 (17 patients/caregivers and 52 health professionals) attended the Boston Workshop, and 55 (10 patients/caregivers and 45 health professionals) attended the Hong Kong workshop. Patients/caregivers were from the host countries, United States and Hong Kong. The 87 health professionals were from 22 countries including the United States (n=26), Australia (n=21), United Kingdom (n=6), Canada (n=4), Singapore (n=4), China-Hong Kong (n=3), 2 each from Belgium, France, Germany, India, Norway, Philippines, Spain, South Korea, Austria, Japan, New Zealand, Pakistan, Switzerland (n=1), Thailand (n=1), The Netherlands (n=1), and Vietnam (n=1). Ten health professionals attended both workshops.

Workshop program and process

Participants received a copy of the program and materials 1 week prior to each workshop. During the workshop, we presented the SONG-Tx process and the preliminary results of the SONG-Tx Delphi Survey. To promote exchange of diverse perspectives and knowledge, attendees were allocated to break out groups (Boston, 6 groups; Hong Kong, 5 groups) with a mix of patients/caregivers and health professionals (from different disciplines and countries). At least 1 member of the SONG-Tx Steering Group or Executive Committee was present in each group to provide clarification as needed. The facilitators/co-facilitators received a run sheet (Supplemental File 2) at a preworkshop briefing session.

Facilitators asked attendees for initial reflections and feedback, focusing on the 10 critical outcome domains identified in the SONG-Tx Delphi Survey (listed above). Three to 5 core outcome domains are recommended for feasibility, however 4 of the critical outcomes were all graft-related. Also, among the 10 critical outcome domains, only 1 (ability to work) was patient-reported (ie, assesses how the patient feels or functions from their perspective)40–42. Therefore, we included questions about combining graft-related outcomes, and including patient-reported outcomes. Each group presented a summary of their discussion to the full group, which was facilitated by JG (Boston) and JCC (Hong Kong). All discussions were audio-taped and transcribed in full.

AT reviewed the transcripts line-by-line and used HyperResearch (ResearchWare Inc. United States. Version 3.0) software to identify and code concepts inductively from the transcripts. Similar concepts were grouped into themes reflecting the range of perspectives on identifying core outcome domains in kidney transplantation. The preliminary analysis was sent to the facilitators to ensure that the range and depth of perspectives were included. Also, we sent a copy of the draft report to all investigators to obtain additional feedback, which was integrated into the final report.

RESULTS

Synthesis of Workshop Discussion

The discussion was summarized into 7 major themes: reinforcing the paramount importance of graft outcomes, reflecting critical trade-offs, contextualizing mortality, imperative to capture patient-reported outcomes, specificity to transplantation, feasibility and pragmatism, and recognizing gradients of severity. For each theme, we described the diversity of opinion, which may not necessarily reflect the views of all participants. Supplementary File 3 shows the groups that contributed to each theme. Brief references are made to the Delphi survey results as necessary. Selected quotations supporting each theme are provided in Table 1. Table 2 provides a summary of recommendations based on the workshop discussions.

Table 1.

Quotations from workshop discussions to illustrate each theme

| Theme | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Reinforcing the paramount importance of graft outcomes |

Prevailing dread of dialysis

|

| Graft survival is a top ranked issue and of

course acute rejection, chronic rejection and graft function, all relate

to the fear of graft loss. – H1 Graft failure is the 1 that matters, graft function is a surrogate of graft survival. – H4 When someone says they’re going to give me a kidney, or have a transplant, I didn’t even think about GFRs or anything like that. P4 We don’t want to go back on dialysis again. P8 We thought that the difference between graft loss, and how high patients rated it was almost a reflection of quality of life being important because the difference in quality of life between dialysis and transplant is so great. – TTS Plenary | |

|

| |

|

Distilling the meaning of graft

function

| |

| None of it [graft loss,

rejection] is good news. Some of it maybe can be dealt with a

little better than others. It’s not over necessarily until

it’s over. To me it’s all the same. –

P2 What level of GFR change makes you worried. We haven’t really defined those in a patient focussed way in a way that actually reflects the implications of them. H6 What’s the most important, the level or the fact that it remains stable over the years. – H8 Level of the graft, that it’s normal. – P8 (reply) | |

|

| |

|

Terrifying and ambiguous terminology

of rejection

| |

| We throw the words chronic rejection around

and there’s not a lot we can do. Maybe patients are hearing

those messages more frequently, the futility of treatment, the lack of

treatments and lack of things that you can do to intervene and

there’s all this uncertainty. How many times do you hear,

‘when’s my graft going to go?’ –

H1 When I have graft rejection, if it is not treated, there is no way to treat it, then my final outcome is death. – P7 I’m mystified by chronic graft rejection because that’s not an issue, I’m not sure what it is, maybe it’s conflating graft loss and graft function – H1 Our biological epidemiological understanding of chronic graft rejection is very flimsy compared to almost everything else on this list probably even compared to the patient reported measures. We believed its real but it’s very hard to come to consensus about when it’s there, its severity, and what we know now I think will be very different to what we will know in 5 years, so if I was going to combine something or downgrade something in favour of something else, that would be my choice – H5 | |

|

| |

| Reflecting critical trade-offs | If you’re really interested in side

effects, you cut down your doses to nothing, and your long term survival

suffers. – H2 Both patients and providers felt that clinical complications of immunosuppression such as infection, cancer and cardiovascular disease were critical to include as core outcomes. – ATC plenary I have taken my immunosuppressant drugs for a long time and I have got a lot of side effects I have got a lot more considerations whether to get my 2nd transplant. - P10 |

|

| |

| Contextualizing mortality |

Inevitability of death

|

| The doctors are more interested in death, and

you really can’t stop death because we’re all eventually

going to die at some point, whereas a healthy graft will prevent that

day from coming for a very long time, so I don’t really know

that death should even be in there because we’re all going to

die eventually. – P1 For my partner his attitude is even if his 1st transplant only lasted a year, he would have had a year without dialysis, and he would have lived that long and he will say nobody expected me to live this long. He’s gained something, he sort of cheated death, so if death comes a little bit later it’s a different thing. – C1 Death is not a core issue. As long as I have the organ, I can live quite well, but if my graft is not functioning well, I have to go back to my previous life that is dialysis, but I won’t die. I won’t die because of the loss of my organ. So I would not be afraid of death, but I would be afraid of the loss of my graft and I would have to come back to dialysis. So this is a matter of quality of life. Everyone has to face death, what I would like to have is a good quality of life rather than to face death. – P11 | |

|

| |

|

Preventing premature death

| |

| As a physician what we’re trying to do

is to prevent early death, before someone’s time. When we see a

patient we transplanted, 3 months later the graft was functioning but

the patient died of a heart attack that’s a terrible outcome and

that’s what we’re trying to prevent. –

H1 As a doctor we have a kind of inherent problem with death. We try to fight death. We are trained to put back life. – H1 There is a slightly unique aspect about the kidney transplant and that is if someone dies be it cardiovascular even immediately after transplant, that’s a kidney that could have gone to somebody else, so it’s not just the patient, we’re also protecting the kidney. – H1 Patients may looking at it in terms of I’m an older individual, if I live 5 years, I’m doing really quite well whereas if I’m 25 and I live 5 years, that’s a poor outcome. It’s not sophisticated enough really as a single endpoint. – H10 | |

|

| |

|

Ensuring safety and quality

| |

| Death is also a safety issue for us when we

look at new drugs. – H1 Regulators tend to be very cognisant of safety issues but the patients and the physicians are telling us that the most important things are retaining a graft, so if there’s a drug that’s being reviewed for approval, and it has some safety issues, that needs to be balanced against the potential for that drug to prolong graft function versus some risk of death. – ATC Plenary I was a little stunned that death wasn’t at the top. As transplanters, death is very important. Any death within a year at my institution requires a formal debriefing and conversation as to what happened. H11 | |

|

| |

| Imperative to capture patient-reported outcomes |

Making patient priorities

explicit

|

| If you have a functioning graft you generally

have a good quality of life, that’s generally true but not

always true and that would completely be glossed over, things like side

effects of drugs, so, I’m sort of a bit uncomfortable with

saying oh that’s covered by graft function. –

H5 The kidney patient doesn’t wake up every morning and worry about whether their graft is going to fail. They wake up worried about, annoyed that they can’t screw the lid back on the tacrolimus top after they’ve taken it because of the tremor. So really important to consider patient reported outcome measures. – ATC plenary I work at this grocery store and I’m always getting germs, pink eye, they just don’t understand the aspect of suppressed immune systems, they think it’s a joke. The social aspect of it is totally missing, they give you the kidney they say go for it, and then you gain 50 pounds because of your prednisone, your appetite comes back up and nobody ever told me, if you have a transplant, I mean I felt great but 50 pounds, 30 years later its diabetes, cataracts, and the long term side effects of all the drugs, and cataracts and crystals with the cyclosporine, so as you say quality of life,. – P5 In our country (Korea), quality of life will be 1 of the main issue to understand the success of a graft, especially if you are doing living kidney transplant, quality of life is very important for us. – H11 | |

|

| |

|

External mandates

| |

| What I get from discussions with the FDA is

that it is very important to have patient-reported outcomes. How the

patient feels, functions, and survives. Actually in some of the other

areas like HIV, aspects such as feels, functions and survives, or

medication nonadherence in some of these trials, is used to enrich the

trials.– H8 So CMS in the US just released a new criteria as a part of QAPI? They’re requiring centres to look at quality of life, so they want centres to capture that and have that as a part of 1 of the metrics that they will evaluate you on so when they come and do your site visits. Transplant centres. they’re beginning to realise this as they get their QAPI surveys, there’s going to be a lot of interest in trying to figure out how do we do that so I, there will be a lot of buy in to try to figure out what that means. - H4 [In the US we have] the quality assessment program improvement, a requirement from our regulatory agencies to make sure we’re constantly assessing our transplant centres outcomes in different ways and they have very recently put a new emphasis on the patient side of things, with a focus on trying to understand how transplant patients quality of life after the transplant has it improved, are we making a difference, are we doing things like we said we should so that’s a new thing. – H4 In ANZDATA, we are interested in recording it for every patient but the problem is there’s so many ways you can record it and no one really agrees on it and most of them would not be practical to do in that many people every year but if something kind of came out of SONG-HD or PD or Transplant, this is what we recommend, we would pilot it. – H5 | |

|

| |

|

Life participation

| |

| The ability to work and quality of life are 2

different things I suppose. For me the ability to work is that I am able

to work and I can find a job if I want to and I physically I have the

capacity, ability to work. But quality of life is something different. I

have the ability to work but that doesn’t mean that I really

need to work or financially, I want to work. Because some patients want

early retirement to enjoy life more. – P10 Some people work to pay bills and some people work because it’s what they want to do. It’s essential to keep people motivated by giving them something, to have a sense of purpose in their lives, whether or not they are being paid for it. – P1 You’re talking about the ability to live your life. – C1 I can only say quality of life is important and I can remember it was worse before the transplant. I couldn’t walk any distance, I couldn’t breathe, and since I’ve received a kidney, I’m now walking miles, and just as much as I could do, to live life is very important to me. – P2 I think of what he wants to do with his life which is why I ranked ability to work very high. You want to have the ability to do something, not necessarily paid work, it could be volunteer work, or family, something that makes you feel fulfilled, and then also gives you a reason for overcoming the challenges you need to overcome when you’re having a transplant. – C3 When I see my patients back on annual visits a good question just in the back of my mind, are you doing everything that you want to do. – H7 Going back to work is not my utmost priority, my priority is to enjoy life. – P10 Maybe it’s as simple as asking patients whether, how well they are able to participate in the life that they want to lead because it’s going to be different for different people. – H9 | |

|

| |

| Specificity to transplantation | I’ve got a bit of a problem with an

outcome of transplantation that you can treat with antidepressants.

– H4 I wasn’t sure whether people were ranking by some combination of seriousness and attributable risk or both. For example skin cancer, I don’t think of it as a likely sequelae of organ transplantation if it were common then I would be inclined to rate if very seriously. I wondered the extreme for example, if shark attack was on there, it would clearly be devastating but not because you’re at an increased risk. – H5 |

|

| |

| Feasibility and pragmatism |

Achievability of long-term

impacts

|

| We’re seeing an increase in trying to

get better grafts and get better initial functioning in the hope that

will lead to better outcomes. If you’re going to ask the surgeon

please give us cancer, cardiovascular disease 5 years out, we’re

going to get a lot of papers that won’t be able to comply with

what the core outcomes. I’m not saying that they’re not

important, I wonder whether there should be a difference between the

type of trial or the type of study and the necessity of which kind of

outcomes need to go in there. – H2 Pharma was saying you don’t have an outcome in a year that we can measure, we’re not really going to invest in drug development in that field so if the goal is clinical trials, how are we going to use this to build into clinical trials? Death is very rare in the 1st year, it’s really 1%, 2%, graft loss is 2% in a year, so things like graft function is something that people are looking at within a 1 to 2 year window of measure as a way of getting sufficient differentiating that you would actually have a sample size that is feasible. – H10 In the UK, we are moving towards a situation where quite a few trials are being funded by the government so there’s no longer the necessity for them to be short term outcomes and there’s the requirement increasingly for the trials to be linked to the national registry so for example, death, cancer rates, can be followed for 5 to 10 years in a cohort that had been intervened or randomised in 1 way. We need to change the focus on how we think about trials, away from short term 6 months, 12 month outcomes, to something we are building, which has a large population that we have enrolled and we have got 5–10 year follow up but it means it takes a long time to answer the question and obviously things change over time, but certainly that’s the way that the national institute of funding is working now so 1 of the issues is not just about the outcome you measure but the duration of time of the trial and how you might measure those outcomes, instead of the traditional way of having just a CRF or eCRF and it might be that you pool the data from different registries. We have the advantages as in Canada we have a national database of everything so you can pool it and link 1 thing to another, but I think there should, that should be 1 way of going. – H10 Belatacept can be an example where they had to go out to 5 years, follow up and continued follow up in order to get to a result that is looking interesting to people so therefore industry will fund longer term studies if that’s the way they’re going to get their product marketed so therefore we should be trying to encourage industry not to just fund things just for 3, 6 to 12 months, we should, maybe partnership with NIH in the States, or NIHR in the UK for example, would mean that you could persuade them to fund things for longer and get longer term outcome measures as well. – H10 | |

|

| |

|

Responsiveness to

interventions

| |

| But if you’re looking at literature

from the past 20 to 40 years, about 95% of the trials will be

drug trials, very limited proportion of trials would be surgical trials,

so those are underrepresented and in those trials we should define short

term outcomes like delayed graft function, function of the kidney,

needing dialysis within the hospital stay, technical graft failures, and

much less about what is kidney function a few years down the road

because as a surgeon we don’t have that, we can’t wait

that long to decide on whether a technique is correct or not. I do not

doubt the importance of outcomes that are here they are all important in

any study, probably should in an ideal world probably be reporting all

of them and follow patients for 10 years and then decide whether or not.

In reality the time isn’t there so may main question is if there

is a ranking order, should all of these core outcomes be a necessity or

should it be, a necessity to report the top 3 or the top 4, I

don’t know. – H2 Skin cancer in a preservation of organs study is not going to be meaningful. – H6 | |

|

| |

| Recognizing gradients of severity | Infection is rated high but can they define

infections because a urinary tract infection is 1 problem, but,

devastating CMV is another. – H7 Disease caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, it’s a very wide definition. – H7 If you’ve got a colon cancer, that’s a bigger deal than skin cancer. – H11 |

H, health professional, P, patient, C, caregivers, number indicated is Group ID (1 – 6 Boston, 7–11 Hong Kong), plenary, quotation was from the full group discussion at the respective workshop

Table 2.

Summary of workshop recommendations to consider in establishing core outcome domains for trials in kidney transplantation

| Clarification of context and principles |

|---|

| • Clarify that core outcome domains

are based on the shared priorities of patients, caregivers and health

professionals in the context of shared decision making. • Acknowledge the range of criteria considered for selecting outcomes for trials (eg, feasibility, responsiveness to an intervention). • Emphasize that other outcome domains are important and core outcomes represent those that are absolutely critical for all trials, as prioritized by patients, caregivers and health professionals. • Explain that core outcomes are not required to be used as primary outcomes (ie, a core outcome does not have to be used as primary outcome to estimate the sample size necessary for an adequately powered study). • Clarify that researchers are not limited to using the core outcome set and can add other outcomes that are relevant to the trial. • Recognize that outcome domains encompass specific outcomes that range in severity, which can be addressed in the next phase of developing core outcome measures. |

|

|

| Core outcome domains for kidney transplantation |

|

|

| • The core outcome domains should

include graft health, medical comorbidities, patient-reported outcomes,

and mortality. • Ensure that terms and definitions for outcome domains are clear, meaningful, and appropriately understood by all stakeholders. • Consider combining graft-related outcomes (graft loss, graft function, acute rejection, and chronic graft rejection) into 1 outcome domain so other critically important outcome domains may be potentially elevated in to the set of core outcome domains to report in trials. Graft outcomes may be disaggregated and addressed separately at the stage of identifying core outcome measures for graft health. • Undertake further work to determine the meaning and reasons for the high priority of graft function among patients, and provide justification for any potential consideration of including this surrogate outcome as a core outcome. • Patient-reported outcome domains should include dimensions that are prioritized by patients and these may capture the burden of symptoms, as well as the patient’s goals. “Ability to participate in meaningful life activities” fulfils these criteria and could be proposed as a patient-reported core outcome domain. • Patient-reported outcome measures should be validated in the kidney transplant population, and across countries and healthcare contexts, cultures and languages. |

Reinforcing the paramount importance of graft outcomes

As expected by participants, graft-related outcomes (graft loss, graft function, acute rejection, and chronic rejection) were the overriding priorities among stakeholders. From the patients’ perspective, graft outcomes were the same – all a threat to graft survival, and the importance placed on this was underpinned by a dread of dialysis. Health professionals drew distinctions between different pathophysiology or causes of chronic rejection.

Prevailing dread of dialysis

Graft loss signalled a dominating fear and aversion to dialysis. For patients, this was the top priority over death and a matter of quality of life. Some patients were “willing to risk not surviving a transplant rather than go on dialysis.” For patients, the possibility of graft failure was an ongoing concern and some questioned whether the drugs would threaten graft survival. Health professionals suggested that long waiting times for transplantation explained the high priority given to graft survival, particularly in countries with very limited access to kidney transplantation.

Distilling the meaning of graft function

Patients stated that graft function was equivalent to not requiring dialysis. It was important that the graft was functioning well or working normally. Health professionals noted that graft function may be a “surrogate” of outcomes that were of direct importance (eg, graft survival, hospitalization, well-being) and questioned whether function mattered on its own. They speculated that patients assumed that graft function (ie, creatinine) was an indicator of graft loss and return to dialysis and reasoned that glomerular filtration rate (GFR) did not necessarily change how the patients felt. Change/stability in kidney function was regarded by health professionals as more important than the “absolute” value as some patients may have suboptimal kidney function but remain stable. They suggested that graft function should be defined in a “patient-focused” way.

Terrifying and ambiguous terminology of rejection

Health professionals believed that the term “rejection” carried catastrophic connotations and were aware that patients could misunderstand rejection invariably as graft loss. Also, the notion of rejecting their donor’s kidney implied guilt. Some patients believed that rejection could be managed with medications but if left untreated could result in death. Health professionals elaborated on different pathways and consequences of the different types of rejection such as cellular versus antibody mediated rejection which garnered attention in terms of risk for graft loss; and they speculated that patients may not be aware of these differences. Although some forms of acute rejection were readily treatable, they suggested that it was still an important outcome particularly if there was an equivalence of treatments. Chronic rejection was consistently regarded by health professionals as ill-defined and not easily measurable. However, the uncertainties in the “multifactorial causes…and flimsy biological epidemiological understanding of chronic graft rejection” and lack of effective treatment, was thought to explain the high importance.

Whilst there were important distinctions among graft-related outcomes, participants suggested that they could be consolidated into 1 domain – graft health, and the specific outcomes may have addressed in the subsequent phrase of developing the specific core outcome measure for graft health. Also, combining graft outcomes into 1 domain would potentially allow for other patient-reported outcomes to be included in the core outcome set.

Reflecting critical trade-offs

Participants reiterated that core outcomes should encompass the trade-offs between graft health and clinical complications of immunosuppression as these were “2 sides of the same coin.” Health professionals emphasized the importance of infection, cancer, and cardiovascular disease as they were the main causes of death, and the main areas of focus for physicians. Kidney transplantation would not cure other comorbidities or complications such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease. One patient said, “I have taken my immunosuppressant drugs for a long time and I have got a lot of side effects. I have got a lot more considerations whether to get my 2nd transplant.” However, participants acknowledged that rare outcomes may be underemphasized by patients who had not experienced that particular outcome.

Contextualizing mortality

In the Delphi survey, health professionals gave higher importance to mortality than patients/caregivers and this discrepancy suggests a more nuanced view of death.

Inevitability of death

Patients regarded death as inevitable and an ongoing risk even if they did not want to die. Ultimately, death could not be prevented, whereas, efforts could be made to prevent graft failure. Even if a graft failed, they would survive on dialysis, to which some regarded as worse than death – “everyone has to face death, what I would like to have is a good quality of life rather than to face death.” Some felt they had already “faced” or “cheated” death so it was no longer a primary concern. One patient articulated, “I don’t think we would ever mind that doctors want to avoid death. That’s your point, of being advocates for life. We’re advocates for our own lives.”

Preventing premature death

Health professionals emphasized their responsibility to prevent early death, for example death caused by a cardiovascular event immediately posttransplant. They admitted having difficulty accepting death and “frightened of killing someone with immunosuppression.” Also, health professionals were conscious to protect the kidney particularly given the organ scarcity. They cautioned against conceptualizing death as a single endpoint, and advised to distinguish early/unexpected death from expected death relative to the patient’s age.

Ensuring safety and quality

For regulators, mortality was a safety issue in drug development though some clinicians urged that this should be “balanced against the potential for drugs to prolong graft function” as it was the top priority for patients and physicians. Also, health professionals routinely included death as a quality parameter. One physician explained, “death within a year at my institution requires a formal debriefing and conversation as to what happened. I was a little surprised that wasn’t number 1.” Some health professionals also highlighted the increased risk of mortality on dialysis.

Imperative to capture patient-reported outcomes

Making patient priorities explicit

Although quality of life, in terms of both well-being and functioning, were recognized to be implicit in graft-related outcomes and medical complications, the need to explicitly include patient-reported outcomes was undisputed – “we need to elevate quality of life into the core outcome set, to give patients a voice.” This would overtly and comprehensively capture the balance between mortality and graft survival, and quality of life/burden of side effects. Some patients were more concerned about lifestyle impacts due to immunosuppression, rather than the graft function. Quality of life was also regarded as an important measure of success of a graft. Some suggested that rating scales should be designed such that it would address quality of life dimensions that patients prioritized to be most important. Using generic surveys that broadly assessed all domains of quality of life negated the need to develop an exhaustive list, however others noted that there a good parameter for specific transplant related quality of life was lacking, and that quality of life was too vague. They suggested distilling quality of life into the most important dimensions. Stakeholders emphasized the need to be cognizant of cultural sensitivities and relevance if it was to be applied globally, considering cultural differences.

External mandates

Health professionals also remarked on the increasing focus on patient-reported outcomes among regulatory/funding agencies, and registries. They specifically referenced the US NIH investment into patient-reported outcome measures through the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), US FDA drug approval requirements to include PROMS; new requirement from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Quality and Assurance and Performance Improvement for centres to assess quality of life; and plans in the European Dialysis and Transplant Registry and Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry to incorporate patient-reported outcomes. Quality adjusted life years also necessitated quality of life measures for policy decisions.

Life participation

Ability to work was the most important patient-reported outcome domain in the Delphi survey, however, it did not apply across all age groups or life stages, and social systems. Thus, participants suggested expanding the scope to encompass the range of life activities that gave patients a sense of fulfilment, enjoyment, control, and hope. While being able to work provided a purpose and “normality” in life, and encompassed multiple psychosocial aspects, patients/caregivers agreed that this should be broadened to include life activities in view of the expectation that transplant enabled patients to live their life and to do everything they wanted to do. One caregiver noted that the ability to participate in life motivated patients and gave them a reason for overcoming the challenges in living with a transplant. Health professionals also supported widening the scope to life participation with specific suggestions including studying, hobbies, house work, caring for the family, and social activities. Assessing ability to participate in meaningful activities was amenable to a measure that allowed patients to define their goals and milestones, and to capture the impact of symptoms and complications (eg, gastrointestinal problems, pain, sleep disturbance, vision problem). Whilst other outcome domains such as cognition and depression were important, these were regarded as relevant to achieving life participation.

Specificity to transplantation

Health professionals were uncertain about assigning priority to outcomes that were not perceived to be directly specific or attributable to transplantation. For example, they argued that depression may not be considered as a core outcome as anyone could have depression and it was not a transplant-related outcome. For skin cancer, 1 participant questioned if people “were ranking by some combination of seriousness and attributable risk (ie, as a sequelae of transplantation), or both,” and hypothesized that higher priority for outcomes may reflect regional variations in risk in the general population eg, the “epidemic of skin cancer in Australia.”

Feasibility and pragmatism

Achievability of long-term impacts

Although long-term outcomes such as cardiovascular disease and cancer were important, health professionals believed that mandating reporting was difficult to achieve as the time required to show a difference could be extensive and important events such short-term graft loss and mortality (ie, within a year posttransplant) were rare. Trials were predominantly short-term. Also, in some countries (such as the Philippines), many kidney transplant recipients were lost to follow up in clinical settings. Health professionals suggested considering interim outcomes such as biomarkers, or diabetes or blood pressure as predictors of cardiovascular disease. However, they understood that “patients may want outcomes that might not be captured within a short period of time and satisfy the requirements set by regulatory agencies,” and advocated for outcomes relevant to patients with other outcomes selected for specific trials. The recent changes in funding structures, namely in the UK, supporting long-term trials, and requirements to link trials with national registries were also noted. Health professionals urged for more efforts to persuade industry as well as to partner with funding agencies to support longer-term trials.

Responsiveness to interventions

Some health professionals were convinced that outcomes should be selected based on potential responsiveness to the interventions, and outcomes relevant to a trial of immunosuppressive agents, lifestyle interventions, surgical techniques or organ perfusion would differ. However, core outcome domains were emphasized to be about relevance to decision making. Although triallists may want to know whether an intervention works, end-users ie, patients and clinicians, want to whether the intervention affects the outcomes they regard as important. Primary outcomes may be selected on feasibility, and appropriateness for the intervention, but the omission of outcomes that stakeholders regard as critical could not be justified.

Recognizing gradients of severity

Health professionals were concerned that some outcome domains were broad and encompassed multiple outcomes with a spectrum of consequences, and this may have had implications for how participants rated its importance. For example, surgical complications could range from minor complications to those that required additional surgical intervention. Infections could range from a urinary tract infection to a more serious infection such as CMV. However, this is true for most outcome domains, and for feasibility, specific outcomes are necessarily combined. Health professionals also considered that expectations about an outcome may differ based on the quality of transplantation (eg, from a living donor and a deceased extended criteria donor), which needed to be considered in establishing a core outcome domain.

DISCUSSION

Stakeholders agreed that core outcome domains for kidney transplantation should include graft health, mortality, cardiovascular disease, infection, cancer, and patient-reported outcomes (ie, life participation) based on their direct relevance for decision-making. Graft survival was unequivocally the dominant priority for patients/caregivers and health professionals, a tangible outcome that offered quality of life gains compared to dialysis. Health professionals deliberated on the importance of graft function in terms of impact on the patients’ functioning and well-being, and validity in predicting graft loss. They also raised concerns about the potential misinterpretation and obscurities around the term and meaning of rejection. The discussions from the workshop showed that patients were focused on well-being and avoiding dialysis, and viewed death as inevitable. Preventing premature death was upheld as a core responsibility among health professionals, and for regulators was a necessary safety consideration.

In the Delphi survey, no patient-reported outcome met the criteria for inclusion as a core outcome domain34. In these consensus workshops, all stakeholder groups advocated for patient-reported outcomes driven by patient priorities and goals, and capturing symptom burden. Patients emphasized that kidney transplantation could enable them to do activities that provided them with a sense of self-value, purpose, fulfilment and enjoyment, and the narrower conceptualization of “ability to work” is not pertinent to all patients (students or retirees). The ability to participate in meaningful activities may be an appropriate patient-reported outcome domain, as it should be relevant to all ages and social systems. Health professionals noted that patient-reported outcomes were increasingly required by regulatory and funding agencies. Similarly, in a recent Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) meeting, participants suggested that patients should be involved as partners during all stages in developing core outcomes measures, and highlighted the importance of validating measures across countries, cultures, and languages43.

Some health professionals challenged outcomes that may not be regarded as “transplant-specific” and raised concerns about the feasibility of including long-term outcomes and outcomes that would not be responsive to specific interventions. Indeed, few trials are beyond 1 year in duration15. However, novel trial designs such as pragmatic trials conducted in clinical settings, and registry-based trials that capitalize on recruitment and follow up structures of registries, are gaining traction, and may overcome these concerns44–51. Importantly, it should be acknowledged that triallists and other stakeholders may have different perspectives (eg, to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention) and considerations about what outcomes to select for trials (eg, based on feasibility, responsiveness, regulatory requirements, cost-efficiency, and ensuring quality and safety). These workshops provided further clarification about the context and implementation of core outcomes. In the context of decision making, patients and clinicians want to whether the intervention affects the outcomes they regard as important. As such, core outcomes should reflect the shared priorities of patients and health professionals and be reported in all trials (in kidney transplantation), regardless of the expected effect of an intervention.

The recommendations arising from this workshop (Table 2) will be taken forward in establishing core outcome domains to be reported in trials conducted in kidney transplant recipients. Following from this this, we will identify the core outcome measure for each of these outcome domains. This should facilitate better understanding, acceptance and uptake of core outcome domains so clinical trials report outcomes that are important to patients and clinicians, and inform shared-decisions about treatment in kidney transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank The Transplantation Society for providing the venue for the SONG-Tx Hong Kong Workshop during the 26th International Congress of The Transplantation Society.

We acknowledge, with permission, all the attendees listed below who attended the consensus workshops.

SONG-Tx Boston 2016 Consensus workshop: Ajay Israni, Alan Leichtman, Allan Massie, Allison Tong, Allyson Hart, Angelique Ralph, Beatrice Oakley, Benedicte Sautenet, Bert Kasiske, Camilla Hanson, Caren Rose, Chris Watson, Christine Murphy, Christophe Legendre, Dana Basken, David Rosenbloom, David Shakespeare, Devin Peipert, Fritz Diekmann, Gabriel Danovitch, Germaine Wong, Gerry Chipman, Greg Knoll, Hallvard Holdaas, Heidi Basken, Ina Jochmans, Jamie Wells, Jayme Locke, Jennifer Trofe-Clark, Jenny Shen, Jeremy Chapman, Jessica Ryan, John Gill, John Kanellis, John Scandling, Joseph Kacoyannakis, Kjersti Lonning, Klemens Budde, Klemens Meyer, Krista Lentine, Linda Rosenbloom, Ling-Xin Chen, Lorelei Basken, Lorna Marson, Marc Cavaillé-Coll, Matthias Buchler, Michael Germain, Michael Murphy, Nicole Evangelidis, Peter Friend, Peter Reese, Phil Clayton, Phil O’Connell, Rainer Oberbauer, Randall Morris, Robert Bulger, Robert Steiner, Rosemary Kacoyannakis, Roslyn Mannon, Sabina De Geest, Sheila Jowsey-Gregoire, Siah Kim, Sobhana Thangaraju, Stephen Fader, Steve Alexander

SONG-Tx Hong Kong 2016 Consensus workshop: Beatriz Dominguez-Gil, Benedicte Sautenet, Benita Padilla, Brian Chu Yuen Tse, Camilla Hanson, Chi Yan Yuen, Choi Fong Hau, Curie Ahn, Deneb Cheung, Dirk Kuypers, Fabian Halleck, Frank Dor, Germaine Wong, Greg Knoll, Hai An Ha Phan, Janet Hui, Jeremy Chapman, Jif Wong, Joen Hui, Jonathan Craig, John Gill, Hatem Amer, Helen Pilmore, Jayme Locke, Jongwon Ha, Kai Ming Chow, Klemens Budde, Kirsten Howard, Lalitha Raghuram, Lin Ping, Lionel Rostaing, Marina Ng, Madeleine Didsbury, Maggie Ma, Martin Howell, Mirjam Tielen, Nga Lun Mok, Nick Larkins, Paul Harden, Penny Allen, Peter Stock, Peter Nickerson, Richard Allen, Romina Danguilan, Ron Shapiro, Samuel Fung, Shigeru Satoh, Stephen McDonald, Tahir Aziz, Teck Chuan Voo, Terence Kee, Vasant Sumethkul, Vathsala Anantharaman, Vivekanand Jha, Allison Tong

Funding: This project is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant 1128564 and Program Grant 1092597. AT is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship 1106716.

ABBREVIATIONS

- (FDA)

Food and Drug and Administration

- (CMS)

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- (GFR)

Glomerular filtration rate

- (NIH)

National Institutes for Health

- (SONG)

Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology

Authors’ specific contributions:

AT participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and drafted the manuscript.

JG participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

KB participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

LM participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

PPR participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

DR participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

LR participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

GW participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

MAJ participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

TLP participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

AW participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

JCC participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

BS participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

NE participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

AFR participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

CSH participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

JIS participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

KH participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

KM participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

RP participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

SF participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

MM participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

CR participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

JR participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

LXC participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

MH participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

NL participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

SK participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

ST participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

AJ participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

JRC participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis, and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Garcia GG, Harden P, Chapman JR. The global role of kidney transplantation. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):e36–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. Organ donation and transplantation activities. 2014 http://www.transplant-observatory.org/data-reports-2014/. Updated April 2016. Accessed 14th December 2016.

- 4.Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2562–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamb KE, Lodhi S, Meier-Kriesche HU. Long-term renal allograft survival in the United States: a critical reappraisal. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(3):450–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stegall MD, Gaston RS, Cosio FG, Matas A. Through a glass darkly: seeking clarity in preventing late kidney transplant failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(1):20–29. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014040378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matas AJ, Gillingham KJ, Humar A, et al. 2202 kidney transplant recipients with 10 years of graft function: what happens next? Am J Transplant. 2008;8(11):2410–2419. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ojo AO, Morales JM, González-Molina M, et al. Comparison of the long-term outcomes of kidney transplantation: USA versus Spain. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(1):213–220. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nankivell BJ, Kuypers DR. Diagnosis and prevention of chronic kidney allograft loss. Lancet. 2011;378(9800):1428–1437. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60699-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pippias M, Stel VS, Aresté-Fosalba N, et al. Long-term kdiney transplant outcomes in primary glomerulomephritis: analysis from the ERA-EDTA registry. Transplant. 2016;100(9):1955–1962. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam NN, Kim SJ, Knoll GA, et al. The risk of cardiovascular disease is not increasing over time despite aging and higher comorbidity burden of kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101(3):588–596. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong G, Chapman JR, Craig JC. Death from cancer: a sobering truth for patients with kidney transplants. Kidney Int. 2014;85(6):1262–1264. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peraldi MN, Berrou J, Venot M, et al. Natural killer lymphcytes are dysfunctional in kidney transplant recipients on diagnosis of cancer. Transplantation. 2015;99(11):2422–2430. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai R, Collett D, Watson CJ, Johnson PJ, Moss P, Neuberger J. Impact of cytomegalovirus on long-term mortality and cancer risk after organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99(9):1989–1994. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones-Hughes T, Snowsill T, Haasova M, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy for kidney transplantation in adults: a systematic review and economic model. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(62):1–594. doi: 10.3310/hta20620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howell M, Wong G, Rose J, Tong A, Craig JC, Howard K. The consistency and reporting of quality of life outcomes in trials of immunosuppressive agents in kidney transplantaiton: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;57(6):762–774. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong A, Budde K, Gill J, et al. Standardized outcomes in nephrology - transplantaiton: a global initiative to develop a core outcome set for trials in kidney transplantation. Transplant Direct. 2016;2(6):e79. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lachenbruch PA, Rosenberg AS, Bonvini E, Cavaillé-Coll MW, Colvin RB. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in renal transplantation: present status and considerations for clinical trial design. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(4):451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight SR, Morris PJ, Schneeberger S, Pengel LH. Trial design and endpoints in clinical transplant research. Transplant Int. 2016;29(8):870–879. doi: 10.1111/tri.12743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight SR, Hussain S. Variability in the reporting of renal function endpoints in immunosuppression trials in renal transplantation: time for consensus? Clin Tranpslant. 2016;30(12):1584–1590. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gargon E, Gurung B, Medley N, et al. Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):156–165. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon L, Strand V, Idzerda L. OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007;26(8):38. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke M. Standardising outcomes for clinical trials and systematic reviews. Trials. 2007;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. Core Outcome Set-STAndards for Reporting: The COS-STAR Statement. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter ME, Larsson S, Lee TH. Standardizing patient outcomes measurement. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(6):504–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1511701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorst SL, Gargon E, Clarke M, Blazeby JM, Altman DG, Williamson PR. Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectivness research: an updated review and user survey. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapadia MZ, Joachim KC, Balasingham C, et al. A core outcome set for chidlren with feeding tubes and neurologic impairment: a systematic review. Pediatr. 2016;138(1):e20153967. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moza A, Benstoem C, Autschbach R, Stoppe C, Goetzenich A. A core outcome set for all types of cardiac surgery effectiveness trials: a study protocol for an international eDelphi survey to achieve consensus on what to measure and the subsequent selection of measurement instruments. Trials. 2015;16:545. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1072-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duffy JM, van’t Hooft J, Gale C, et al. A protocol for developing, disseminating, and implementing a core outcome set for pre-eclampsia. Trials. 2016;6(4):274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iyengar S, Williamson PR, Schmitt J, et al. Development of a core outcome set for clinical trials in rosacea: study protocol for a systematic review of the literature and identification of a core outcome set using a Delphi survey. Trials. 2016;17(1):429. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1554-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaiser U, Kopkow C, Deckert S, Sabatowski R, Schmitt J2. Validation and application of a core set of patient-relevant outcome domains to assess the effectiveness of multimodal pain therapy (VAPAIN): a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e008146. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkham JJ, Boers M, Tugwell P, Clarke M, Williamson PR. Outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis randomised trials over the last 50 years. Trials. 2013;14:324. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sautenet BTA, Manera KE, Chapman JR, et al. Developing consensus-based priority outcome domains for trials in kidney transplantation: a multinational Delphi survey with patients, caregivers and health professionals. Transplantation. 2017 doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001776. press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobbels F, Wong S, Min Y, Sam J, Kalsekar A. Beneficial effect of belatacept on health-related quality of life and perceived side effects: results from the BENEFIT and BENEFIT-EXT trials. Transplantation. 2014;98(9):960–968. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howell M, Tong A, Wong G, Craig JC, Howard K. Important outcomes for kidney transplant recipients: a nominal group and qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(2):186–196. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.02.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howell M, Wong G, Rose J, Tong A, Craig JC, Howard K. Eliciting patient preferences, priorities and trade-offs for outcomes following kidney transplantation: a pilot best-worst scaling survey. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e008163. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jamieson NJ, Hanson CS, Josephson MA, et al. Motivations, challenges, and attitudes to self-management in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(3):461–478. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laupacis A, Pus N, Muirhead N, Wong C, Ferguson B, Keown P. Disease-specific questionnaire for patients with a renal transplant. Nephron. 1993;64(2):226–231. doi: 10.1159/000187318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson EC, Eftimovska E, Lind C, Hager A, Wasson JH, Lindblad S. Patient reported outcome measures in practice. Br Med J. 2015;350:g7818. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Her M, Kavanaugh A. Patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24(3):327–334. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283521c64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Published December 2009. Accessed 9th December 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Kirwan JR, Bartlett SJ, Beaton DE, et al. Updating the OMERACT filter: implications for patient-reported outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(5):11011–11015. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wachtell K, Lagerqvist B, Olivecrona GK, James SK, Fröbert O. Novel trial designs: lessons learned from thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in scandinavia (TASTE) trial. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(1):11. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0677-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fröbert O, Lagerqvist B, Olivecrona GK, et al. Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(17):1587–1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hilton J, Mazzarello S, Fergusson D, et al. Novel methodology for comparing standard-of-care interventiosn for patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(12):e1016–1024. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Boer IH, Kovesdy CP, Navaneethan SD, et al. Pragmatic clinical trials in CKD: opportunities and challenges. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(10):2948–2954. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015111264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newman AB, Avilés-Santa ML, Anderson G, et al. Embedding clinical interventions into observational studies. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;46:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.James S, Rao SV, Granger CB. Registry-based randomized clinical trials–a new clinical trial paradigm. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(5):312–316. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olsen SF, Østerdal ML, Salvig JD, et al. h oil intake compared with olive oil intake in late pregnancy and asthma in the offspring: 16 y of registry-based follow-up from a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(1):167–175. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao SV, Hess CN, Barham B, et al. A registry-based randomized trial comparing radial and femoral approaches in women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the SAFE-PCI for Women (Study of Access Site for Enhancement of PCI for Women) trial. JACC Cadiovas Interv. 2014;7(8):857–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.