Abstract

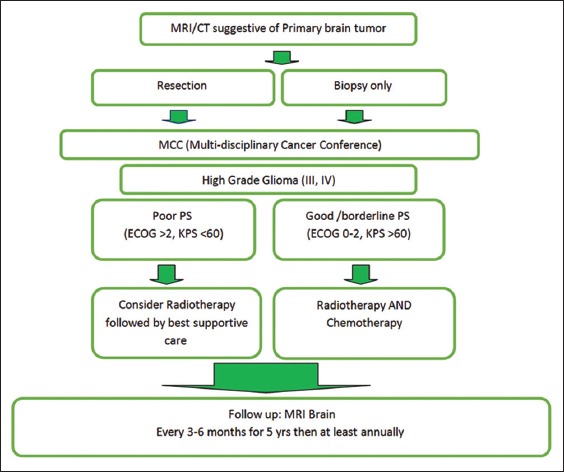

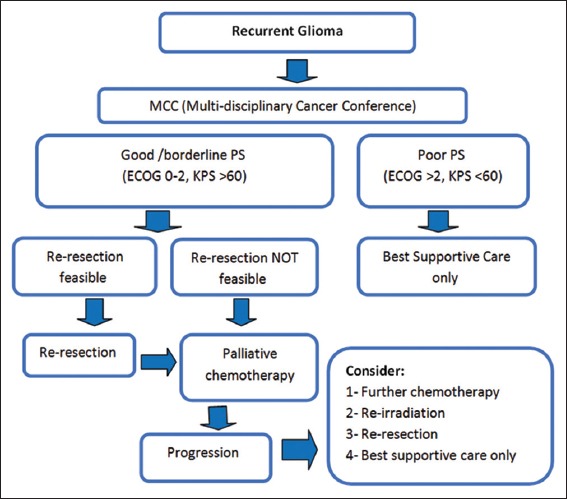

The treatment recommendations provided in this manuscript are intended to serve as a knowledge base for clinicians and health personals involved in treating patients with high-grade malignant glioma. In newly diagnosed patients, complete resection or biopsy is required for histological characterization of the tumor, which in turn is essential to decide the treatment strategy. In patients with good or borderline performance score, radiotherapy (RT), and chemotherapy are the preferred management. In patients with poor performance score, RT with best possible supportive care is the mainstay of the management. All patients have to undergo brain magnetic resonance imaging procedure quarterly or half-yearly for 5 years and then on an annual basis. In patients with recurrent malignant glioma, wherever possible re-resection or re-irradiation or chemotherapy can be considered along with supportive and palliative care. High-grade malignant glioma should be managed in a multidisciplinary center with the best of the possible care that is available based on the evidence as discussed in this manuscript.

Keywords: Guidelines, management, high-grade, glioma, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Primary malignant brain tumors in the adults are uncommon. It represents 2-3% of all adult tumors in Saudi Arabia. The yearly incidence of primary malignant brain tumors is 1-2/100 000 with a slight predominance in males.1 The most common primary malignant brain tumor is malignant glioma. It may develop at all ages, with the peak incidence in the 5th and 6th decades of life. They are quite heterogeneous group of tumors with varied outcomes and treatment approaches. They range from low-grade tumors that are slow-growing to high-grade tumors that are aggressive and virtually incurable.

We searched the PubMed database search to obtain the key literature in high-grade glioma, published between January 2014 and April 2016 using the following search keywords; high-grade glioma, glioblastoma, and anaplastic glioma. The PubMed database was chosen because it is most widely used resource for medical literature. The search results were narrowed by selecting studies including human participants published in English. The result was confined to the following article types: Clinical trial, Phase III, guidelines, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trials (RCT), and systematic review. The PubMed resulted in 406 citations, and their potential relevance was examined and reviewed.

Patients with high-grade glioma usually present with progressive neurologic signs and symptoms that vary according to the size, location, and rate of growth of the tumor. Common symptoms are headache (~50%) and seizure (~20-30%). Other common symptoms include memory loss, motor weakness, visual symptoms, language deficit, and cognitive, and personality changes.2 Factors influencing prognosis are age, tumor grade, Karnofsky performance status (KPS), the number of molecular alterations3,4 and the extent of initial surgical resection. The influence of clinical factors such as age and KPS on outcome was identified in glioblastoma patients using recursive partitioning analysis.4 Both tumor type and histologic grade are well-recognized prognostic factors in high-grade glioma. In general, astrocytic tumors tend to behave more aggressively than oligodendroglial tumors, and Grade IV tumors (i.e., glioblastoma) behave more aggressively than Grade III tumors (i.e., anaplastic).5

Recently, a number of biomarkers including gene expression analysis, have been found to be useful for prognostication. For example methylation of methyl guanine methyl transferase (MGMT) predict better survival rate in patients with high-grade glioma, particularly in elderly patients.6,7 MGMT enzyme handles DNA-repair following alkylating agent chemotherapy. Combined loss of chromosomes 1p and 19q improves survival and responsiveness to therapy in oligodendroglial tumors.8 Mutations in the enzyme isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and IDH2 improves overall survival, independent of other established prognostic factors, especially in anaplastic gliomas.9

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are the non-invasive imaging modalities of choice for characterizing high-grade gliomas and for target volume delineation.10,11 CT helps in the assessment of calcified and hemorrhagic lesions as well as those that may involve bone. While, contrast-enhanced MRI is superior because of its higher soft tissue resolution and multiplanar imaging capabilities. Advanced MRI techniques, including MR spectroscopy, MR perfusion, and functional imaging are also routinely performed for pre-operative grading of gliomas and to follow treatment response.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies gliomas into four histological grades.12 This manuscript focuses only on high-grade gliomas, which includes WHO Grade IV tumors (glioblastoma and its variants) and Grade III tumors (anaplastic astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and oligoastrocytoma).13

Role of Surgery in High-grade Gliomas

A tissue diagnosis by biopsy or surgery is mandatory before commencing definitive therapy.14 In majority of the patients, maximal safe resection is the preferred initial approach for both diagnosis and management.15-18 Maximal safe surgical resection with an aim for the preservation of neurologic function19 results in improved functional status and possibly, with prolonged survival.20 Surgery is done under blue light with a fluorescent marker 5-aminolevulinic acid for the tumor increases the probability of complete resection rate and progression-free survival.21 A biopsy is normally considered when the lesion is not amenable to resection, or if the patient’s overall clinical condition is not fit for surgery. Deep brain biopsies with accurate tumor localization particularly in focal lesions are made possible by combined use of computerized imaging and stereotactic devices.22,23 Positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy have been used to characterize metabolically active areas of tumor, and thereby increasing the accuracy of stereotactic brain biopsy.24,25

There are no RCT to establish the benefit of maximal surgical resection over a more limited resection. Quite a few number of studies have failed to show a benefit with extensive surgical resection (either subtotal resection vs. biopsy, or complete vs. subtotal resection).26-28 However, other studies have suggested that maximal resection (particularly gross total resection) does improve survival.21,29-36 Resection provides a larger, more representative tissue sample for detailed analysis, therefore increasing the likelihood of an accurate diagnosis, which in turn can help to tailor further therapies. Debulking surgery may lead to rapid tapering and discontinuation of steroids, thereby reducing steroid-related complications, debulking before radiotherapy (RT) or chemotherapy may improve the response to post-operative adjuvant treatments.37 Considering the above findings, we recommend initial maximal surgical resection in patients with high-grade glioma.

Pre-operative functional MRI or PET can optimize tumor volume definition and minimize operative injury to critical areas, such as motor and speech areas.38 Intraoperative imaging is used to characterize residual tumor after the initial resection and thereby can be used to guide further surgery with minimal collateral damage to normal brain tissues.39 However, such techniques have not been shown to improve survival in patients with high-grade gliomas.40 Despite the recent advances in surgical techniques, local recurrences are common even in patients undergoing an apparent complete resection of the tumor. This is because high-grade gliomas tend to have cancer cells infiltrating white matter fibers and the perivascular spaces well beyond the tumor border as defined by the surgeon or by current multimodality imaging including multiparametric MRI and mulitracer PET studies.41,42

Role of Adjuvant RT in Glioblastoma

Adjuvant radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy is considered the standard of care following surgery for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Adjuvant RT improves local control and survival after surgical resection.43,44 Post-operative RT field should include tumor bed, residual enhancing tumor, and edema with a margin except for patients with KPS <50, where they will receive whole brain RT.45,46 RT consists of fractionated regimen, delivering a total dose of 60 Gy in 30 daily treatments, 1 treatment per day, 5 treatments per week over 6 weeks for patients with good KPS.47-49 For patients with age ≥60 and KPS >50, RT will consist of 40 Gy in 15 daily treatments, 1 treatment per day, 5 treatments per week over 3 weeks.50 For patients with KPS <50, RT will consist of 30 Gy in 10 daily treatments to the whole brain, 1 treatment per day, 5 treatments per weeks over 2 weeks.47 Treatment should start within 4-6 weeks of surgery. There is no evidence that hyper fractionation or accelerated fractionation or higher dose improves outcome.47-51

Acute expected radiation-induced toxicities include hair loss, fatigue, and erythema, or soreness of the scalp. Potential acute toxicities include nausea and vomiting as well as a temporary aggravation of glioma symptoms such as headaches, seizures, and weakness. Early delayed radiation effects include lethargy and transient worsening of existing neurological deficits occurring 1-3 months after RT treatment. Late, delayed effects of RT include radiation necrosis, endocrine dysfunction, and radiation-induced neoplasms.

Role of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Glioblastoma

Adjuvant chemotherapy improves overall survival in patients with glioblastoma either alone or in combination with RT.52 Temozolomide (TMZ) is the most commonly used drug in the glioblastoma treatment regime. It is an imidazotetrazine derivative of the alkylating agent dacarbazine. It undergoes rapid chemical conversion in the systemic circulation at physiological pH to the active compound, monomethyl triazeno imidazole carboxamide. It exhibits dose-dependent antitumor activity by targeting DNA replication. TMZ has demonstrated activity against recurrent and newly diagnosed glioma. Stupp et al. have shown the benefit of RT plus concomitant and adjuvant TMZ for glioblastoma.53 The combination of TMZ plus RT has shown improvement in overall survival compared with RT alone in a 5 years follow-up study (overall survival 27% vs. 11% and 10% vs. 2% at 1 and 5 years, respectively).54 For those with MGMT methylation, the 2-year survival rates were 49% and 24% with combination therapy and with RT alone, respectively, while for those without MGMT methylation, the 2-year survival rates were 15% and 2%, respectively.54,55 Benefits from adjuvant TMZ were observed in all patient subsets, including those over 60 years and those with other poor prognostic factors.

Adverse Effects of TMZ

Hematological

Moderate to severe thrombocytopenia is the most common hematologic adverse effect, occurring in approximately 10-20% of patients.56 Moderate to severe lymphopenia and neutropenia occur in 5-15% of patients at the completion of 6 weeks of daily TMZ with concomitant RT.57 Patients are at risk for Pneumocystis pneumonia due to selective CD4+ T cell depletion; the risk is increased in patients receiving corticosteroids and in those receiving prolonged daily dosing regimens. All patients being treated with daily TMZ during RT should receive Pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis until recovery of lymphopenia.58,59

Non-hematological

Common non-hematologic side effects are nausea, anorexia, and fatigue. Fatal and severe hepatotoxicity have been reported, and liver function tests should be performed at the beginning, during and at the end of the treatment.60 TMZ is moderately emetogenic, and premedication with an oral serotonin 5-HT3 antagonist should be provided in all patients during adjuvant therapy. Other rare but life-threatening idiosyncratic reactions reported are hypersensitivity pneumonitis, allergic skin reactions, opportunistic infections, aplastic anemia, myelodysplasia, and treatment-related acute myeloid leukemia.41,42

Concomitant TMZ Dosing During RT Treatment

Daily dose of TMZ for concomitant therapy is 75 mg/m2 (oral) taken 1 h before each session of RT during weekdays. During weekends without RT, the drug is taken in the morning.54 The treatment schedule is for 6 weeks. In the case of delays in the delivery of the RT, TMZ is given for a maximum of 7 weeks. The dose administered is determined using the body surface area and rounded to the nearest 5 mg.

Dose Adjustments During Concomitant TMZ Treatment

During the concomitant treatment, no dose reductions will be made. Delay and discontinuation will be decided according to toxicity criteria given by CTCAE grading (version 4).61 Treatment should be delayed until normalization in the following conditions: Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <1.0 × 109/L, platelet count <100 × 109/L and Grade 3 non-hematological toxicities other than fatigue, alopecia, nausea, and vomiting. However, the delay may not exceed 2 weeks, if toxicity is ongoing at that time, concomitant treatment with TMZ must be discontinued. TMZ treatment will be discontinued in Grade 4 non-hematological toxicity and if the ANC goes <0.5 × 109/L or the platelet count goes below 25 × 109/L.

TMZ Dosing During Adjuvant Treatment

Adjuvant TMZ treatment will be started 4 weeks after the end of concomitant chemoRT. TMZ is administered orally once a day for five consecutive days (days 1-5). The starting dose for the first cycle will be 150 mg/m2/day (dose level 0) with a single dose escalation to 200 mg/m2/day (dose level +1) in subsequent cycles if no significant toxicity is observed in the first cycle. Dose can be reduced one level to 100 mg/m2/day (dose level -1) depending of toxicity. One cycle is defined as 28 days, and a maximum of 6 cycles will be administered. Adjuvant TMZ treatment is planned for a maximum of 6 cycles. Other schedules of TMZ have not been shown to be more effective than the standard post-RT schedule of five every 28 days in the adjuvant setting.62,63 Based on NOA-08 and Nordic trails, elderly patients who are not candidates for TMZ concomitant with RT followed by adjuvant TMZ should be treated with RT (e.g., 15 doses of 2·66 Gy) alone for an unmethylated gene promoter or TMZ (5/28) alone for the methylated promoter.64,65

Dose Adjustments During Adjuvant TMZ Treatment

During adjuvant treatment, TMZ dose interruptions, as well as modifications, are allowed based on toxicity observed during the prior treatment cycle. If multiple toxicities are seen, the dose administered should be based on the dose reduction required for the most severe grade of any single toxicity. No dose reductions below 100 mg/m2 are allowed. If 100 mg/m2 is not tolerated, the patient should stop treatment. Once a dose has been reduced, no dose re-escalation is allowed.

Bevacizumab plays a key role in the growth of the abnormal vasculature observed in high-grade gliomas and other tumors. In the Avaglio study, the patients were randomly assigned to receive bevacizumab or placebo in conjunction with radiation and TMZ. After the completion of radiation, the patients underwent 6 cycles of monthly TMZ plus bevacizumab or placebo every 2 weeks, which were followed by maintenance bevacizumab or placebo every 3 weeks until further development. The results obtained showed that the enhanced median progression-free survival for patients treated with bevacizumab compared with placebo. On the other hand, an increase was also observed in the rate of adverse events with serious implications in patients treated with bevacizumab compared with placebo.66-74

In the radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) study, patients were randomly assigned to receive bevacizumab or placebo opening at week 4 of standard chemoradiation with TMZ, which was followed by 6-12 cycles of maintenance TMZ plus bevacizumab or placebo. Although the results did not meet the required threshold, the median progression-free survival was enhanced in patients. In addition, the bevacizumab group experienced the worse quality of life, and a sharp decline in neurocognitive function compared with the placebo group.75,76

Therefore, the results determined showed that the regular use of bevacizumab in combination with standard radiation and TMZ was not recommended in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. This is further backed by the fact that there was no significant survival benefit for bevacizumab when used as initial therapy and the increased risk of toxicity was noted with regard to combination therapy.77

Role of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Anaplastic Astrocytoma

Based on the NOA-04 trial findings, chemotherapy with TMZ or PCV (procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine) is as effective as RT in the treatment of anaplastic astrocytomas. Patients with high-grade astrocytoma benefit from implantation of carmustine wafers at the time of surgical resection of the tumor as they improve survival by 8-11 weeks.78-80 Adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery and RT improves disease-free survival.52,81 There are two large multicenter phase III trials in progress examining various combinations of RT and concomitant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed anaplastic glioma with or without 1p/19q co-deletion (NCT00887146, NCT00626990), but results from these trials will not be available for several years.

Role of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Anaplastic Oligodendroglial Tumors

Oligodendroglial tumors represent 5-20% of all glioma. All suspected oligodendrogliomas must undergo histological confirmation, as radiological features alone are inadequate for diagnosis and staging.82,83 Despite the prolonged clinical course seen with these tumors, the outcome is usually poor. Patients with Grade III oligodendroglial tumors have a better outcome than those with anaplastic astrocytoma. Oligodendroglial tumors carry certain favorable molecular markers, such as 1p19q co-deletion and IDH mutations. Maximal gross surgical resection is recommended where technically feasible, as it increases survival.84,85

Two randomized Phase III trials (EORTC 26951 trial and RTOG 9402 trial) have shown that a combination of both RT and PCV following surgical resection improves overall survival on long-term follow-up in the subset of patients with 1p19q co-deletion.86-88 Other molecular subgroups such as IDH and MGMT may still benefit from adding chemotherapy to RT.89,90 At a median follow-up of 60 months in both trials8,91,92 progression-free survival was significantly prolonged with adjuvant PCV compared to RT alone, but no significant difference was achieved in overall survival.78 Oligodendroglial tumors are more chemotherapy sensitive than astrocytic tumors.93 Based on NOA4 trial results, the efficacy of PCV regimen and TMZ regimen was similar in patients with glioma, but long-term follow-up is not yet available.5 TMZ is preferred over the PCV regimen in most practice, based on its convenience of administration and better tolerability, although PCV remains an option for anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors.

Management of Recurrent High-grade Gliomas

Despite the survival benefit of adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy in high-grade glioma, the outcome of this disease is poor, and the majority of patients relapse. The treatment options for such patients have to be individualized assessing the benefit/risk ratio.

Early Progression Versus Pseudo Progression

Disease progression is often difficult to distinguish from radiation necrosis or other radiation-induced imaging changes. Distinguishing them is important to prevent inappropriate discontinuation of an effective treatment regimen. Pseudoprogression is a treatment-related effect with MRI features mimicking true tumor progression, usually occurring within 3 months of completion of chemoradiation94,95 in 15-30% of patients.96,97 Advanced MRI techniques, particularly MR spectroscopy and perfusion imaging when combined with the conventional MRI are sometimes helpful to differentiate between pseudoprogression or true progression. The diagnosis is often made retrospectively, based on improvement or stabilization of imaging findings in the setting of continuation of the initial chemotherapy (TMZ) for at least 6 months as suggested by Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology working group.82 Patients with imaging evidence suggesting disease progression within 3 months after completion of chemoradiotherapy should continue their planned adjuvant chemotherapy unless there is evidence of clinical deterioration or until there is evidence of further disease progression on imaging.

Median overall survival of the patient with recurrent high-grade gliomas is <1 year. Although further interventions such as re-resection, re-irradiation, and systemic therapy can benefit some patients, all treatments are palliative and associated with risks and side effects. Regardless of whether subsequent treatment is pursued, patients should be offered maximal supportive care, including palliative care and hospice as appropriate. One of the important prognostic factors for benefit from further interventions is the performance status.98-100 Other factors include the extent of disease, the histologic grade, the relapse-free interval, and recurrence pattern (i.e., local vs. diffuse).100-105

Local Therapy

The impact and selection of patients for a debulking re-resection are not firmly established. Selected patients with a large tumor exerting symptomatic mass effect may benefit from re-resection. The most significant predictor of longer survival after re-resection is a good performance status. Other favorable prognostic predictors include young age, recurrence-free interval, and the extent of the second surgical resection.106,107 The role of re-irradiation in patients with recurrent glioblastoma is unclear. On retrospective data, some patients with small recurrent tumors and a good performance status may benefit from re-irradiation.58

Palliative Systemic Therapy

Palliative systemic therapy has been tried with systemic agents such as bevacizumab, nitrosoureas, and re-challenge with TMZ.

Bevacizumab

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays an important role in the development of the abnormal vasculature observed in high-grade gliomas and other tumors. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds circulating VEGF and prevents its interaction with VEGF receptors on the cell surface. Bevacizumab acts by increasing the delivery of chemotherapy to the tumor.108 Bevacizumab has shown significant promise in Phase II studies as a single agent or in combination with irinotecan or lomustine in patients with high-grade gliomas.108-110 The objective response rates with bevacizumab alone or in combination with irinotecan were 28% and 38%, respectively, and the 6-month progression-free survival rates and overall survival were 43% and 50%, and 9.2 and 8.7 months, respectively. With longer follow-up, the 12 and 24-month survival rates were 38% and 17% on both treatment arms, which appeared to be better than historical control series.108

In patients who progress on bevacizumab monotherapy, we suggest the continuation of bevacizumab and addition of a cytotoxic agent. In patients who progress while receiving bevacizumab plus chemotherapy, a continuation of bevacizumab beyond progression and a change of chemotherapy agent to a drug with a different mechanism of action may be utilized in patients with good performance status. The two clinical trials that led to the approval of bevacizumab for recurrent high-grade glioma used a dose of 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks. There is no difference in progression-free or overall survival when patients with high-grade glioma are treated with doses ranging from 5 to 15 mg/kg every 2-3 weeks.111 Less frequent dosing can be more convenient for patients since many of them have a neurologic disability that makes travel difficult. Bevacizumab is associated with cardiovascular effects such as hypertension, thromboembolism, intracranial hemorrhage and left ventricular dysfunction, and non-cardiovascular effects, such as proteinuria, delayed wound healing and bleeding.112

Nitrosoureas

For patients who were previously treated with TMZ and are not candidates for bevacizumab, nitrosourea-based chemotherapy is a reasonable alternative. Nitrosoureas either as single agents such as lomustine or in combination regimens such as PCV have shown effectiveness in Phase II studies of previously treated patients and are reasonable options.112,113 The combination regimen of PCV was compared with TMZ in a Phase III trial in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma.115 There was no difference in progression-free survival or overall survival.

Figure 1.

Newly diagnosed glioma pathway

Figure 2.

Recurrent glioma pathway

TMZ re-challenge

TMZ using a different dosing schedule has been addressed in Phase II studies of patients with recurrent high-grade glioma with mixed results.103-110 In general, patients who have relapsed several months after completion of adjuvant TMZ and whose tumors have MGMT methylation are the best candidates for re-challenge with TMZ. In Phase II study (RESCUE), use of daily TMZ (50 mg/m2/day for up to 1 year) was studied in 120 patients.114 For patients with glioblastoma, the 6-month progression-free survival ranged from 15% to 29%, depending on whether progression occurred during or after the original adjuvant TMZ treatment. For patients with an anaplastic glioma, the 6-month PFS was 36% with dose-intense TMZ.

Supportive Care

Optimal supportive care is important in the management of all patients with recurrent or progressive high-grade glioma, whether or not they are planned for further therapy. Steroids and antiepileptic drugs are commonly used in glioma patients for management of edema and seizures. Patients with a very low functional and poor performance status, including those who are non-ambulatory and fully dependent for activities of daily living, have a very poor prognosis and are best managed with maximal supportive care and palliative care alone.

Conclusions

Histopathological diagnosis is mandatory to characterize the tumor grade. Complete surgical resection as feasible is the primary treatment in all cases of high-grade glioma. RT with TMZ is the treatment of choice for glioblastoma. In a patient with anaplastic glioma, RT and adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered. In anaplastic oligodendroglioma, TMZ is the preferred regimen compared to PCV, based on its convenience of administration and better tolerability. However, PCV remains an option for anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors. Despite the administration, majority of patients relapse. The treatment options for such patients may include further interventions such as re-resection, re-irradiation, and systemic therapy, or maximal supportive care only.

References

- 1.Cancer Incidence Report, Saudi Arabia 2010. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health Saudi Cancer Registry. 2010. [Last accessed on 2016 April]. Available from: http://www.chs.gov.sa/Ar/mediacenter/NewsLetter/2010%20Report%20(1).pdf .

- 2.Chang SM, Parney IF, Huang W, Anderson FA, Jr, Asher AL, Bernstein M, et al. Patterns of care for adults with newly diagnosed malignant glioma. JAMA. 2005;293:557–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorlia T, Van Den Bent MJ, Hegi ME, Mirimanoff RO, Weller M, Cairncross JG, et al. Nomograms for predicting survival of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma:Prognostic factor analysis of EORTC and NCIC trial 26981-22981/CE.3. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:29–38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamborn KR, Chang SM, Prados MD. Prognostic factors for survival of patients with glioblastoma:Recursive partitioning analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2004;6:227–35. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wick W, Hartmann C, Engel C, Stoffels M, Felsberg J, Stockhammer F, et al. NOA-04 randomized phase III trial of sequential radiochemotherapy of anaplastic glioma with procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine or temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5874–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerstner ER, Yip S, Wang DL, Louis DN, Iafrate AJ, Batchelor TT. Mgmt methylation is a prognostic biomarker in elderly patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neurology. 2009;73:1509–10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bf9907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reifenberger G, Hentschel B, Felsberg J, Schackert G, Simon M, Schnell O, et al. Predictive impact of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma of the elderly. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1342–50. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kouwenhoven MC, Gorlia T, Kros JM, Ibdaih A, Brandes AA, Bromberg JE, et al. Molecular analysis of anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors in a prospective randomized study:A report from EORTC study 26951. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:737–46. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2009-011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:765–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly PJ, Daumas-Duport C, Kispert DB, Kall BA, Scheithauer BW, Illig JJ. Imaging-based stereotaxic serial biopsies in untreated intracranial glial neoplasms. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:865–74. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.6.0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornton AF, Jr S, andler HM, Ten Haken RK, McShan DL, Fraass BA, La Vigne ML, et al. The clinical utility of magnetic resonance imaging in 3-dimensional treatment planning of brain neoplasms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;24:767–75. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90727-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myint PK, May HM, Baillie-Johnson H, Vowler SL. CT diagnosis and outcome of primary brain tumours in the elderly:A cohort study. Gerontology. 2004;50:235–41. doi: 10.1159/000078346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metcalfe SE, Grant R. Biopsy versus resection for malignant glioma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001:CD002034. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vuorinen V, Hinkka S, Färkkilä M, Jääskeläinen J. Debulking or biopsy of malignant glioma in elderly people - A randomised study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2003;145:5–10. doi: 10.1007/s00701-002-1030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawaya R. Extent of resection in malignant gliomas:A critical summary. J Neurooncol. 1999;42:303–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1006167412835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shapiro WR. Treatment of neuroectodermal brain tumors. Ann Neurol. 1982;12:231–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410120302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Black PM. Brain tumors. Part 1. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1471–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105233242105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barker FG, 2nd, Curry WT, Jr, Carter BS. Surgery for primary supratentorial brain tumors in the United States 1988 to 2000: The effect of provider caseload and centralization of care. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7:49–63. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, Wiestler OD, Zanella F, Reulen HJ ALA-Glioma Study Group. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma:A randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:392–401. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paleologos TS, Dorward NL, Wadley JP, Thomas DG. Clinical validation of true frameless stereotactic biopsy:Analysis of the first 125 consecutive cases. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:830–5. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel N, Sandeman D. A simple trajectory guidance device that assists freehand and interactive image guided biopsy of small deep intracranial targets. Comput Aided Surg. 1997;2:186–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grosu AL, Weber WA, Franz M, Stärk S, Piert M, Thamm R, et al. Reirradiation of recurrent high-grade gliomas using amino acid PET (SPECT)/CT/MRI image fusion to determine gross tumor volume for stereotactic fractionated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:511–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried I, Nenov VI, Ojemann SG, Woods RP. Functional MR and PET imaging of rolandic and visual cortices for neurosurgical planning. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:854–61. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.5.0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quigley MR, Maroon JC. The relationship between survival and the extent of the resection in patients with supratentorial malignant gliomas. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:385–8. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199109000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coffey RJ, Lunsford LD, Taylor FH. Survival after stereotactic biopsy of malignant gliomas. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:465–73. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan GG, Goodman GB, Ludgate CM, Rheaume DE. The treatment of adult supratentorial high grade astrocytomas. J Neurooncol. 1992;13:63–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00172947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreth FW, Thon N, Simon M, Westphal M, Schackert G, Nikkhah G, et al. Gross total but not incomplete resection of glioblastoma prolongs survival in the era of radiochemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:3117–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simpson JR, Horton J, Scott C, Curran WJ, Rubin P, Fischbach J, et al. Influence of location and extent of surgical resection on survival of patients with glioblastoma multiforme:Results of three consecutive Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) clinical trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;26:239–44. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR, Gokaslan ZL, Shi W, DeMonte F, et al. Amultivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme:Prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:190–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.2.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bucci MK, Maity A, Janss AJ, Belasco JB, Fisher MJ, Tochner ZA, et al. Near complete surgical resection predicts a favorable outcome in pediatric patients with nonbrainstem, malignant gliomas. Cancer. 2004;101:817–24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood JR, Green SB, Shapiro WR. The prognostic importance of tumor size in malignant gliomas:A computed tomographic scan study by the Brain Tumor Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:338–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.2.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pichlmeier U, Bink A, Schackert G, Stummer W ALA Glioma Study Group. Resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme:An RTOG recursive partitioning analysis of ALA study patients. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:1025–34. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devaux BC, O'Fallon JR, Kelly PJ. Resection, biopsy, and survival in malignant glial neoplasms. A retrospective study of clinical parameters, therapy, and outcome. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:767–75. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.5.0767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laws ER, Parney IF, Huang W, Anderson F, Morris AM, Asher A, et al. Survival following surgery and prognostic factors for recently diagnosed malignant glioma:Data from the Glioma Outcomes Project. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:467–73. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.3.0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glantz MJ, Burger PC, Herndon JE, 2nd, Friedman AH, Cairncross JG, Vick NA, et al. Influence of the type of surgery on the histologic diagnosis in patients with anaplastic gliomas. Neurology. 1991;41:1741–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.11.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pirotte B, Goldman S, Dewitte O, Massager N, Wikler D, Lefranc F, et al. Integrated positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging-guided resection of brain tumors:A report of 103 consecutive procedures. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:238–53. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kubben PL, Ter Meulen KJ, Schijns OE, Ter Laak-Poort MP, Van Overbeeke JJ, Van Santbrink H. Intraoperative MRI-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme:A systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1062–70. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barone DG, Lawrie TA, Hart MG. Image guided surgery for the resection of brain tumours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;28:CD009685. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009685.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giese A, Bjerkvig R, Berens ME, Westphal M. Cost of migration:Invasion of malignant gliomas and implications for treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1624–36. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albert FK, Forsting M, Sartor K, Adams HP, Kunze S. Early postoperative magnetic resonance imaging after resection of malignant glioma:Objective evaluation of residual tumor and its influence on regrowth and prognosis. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:45–60. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hochberg FH, Pruitt A. Assumptions in the radiotherapy of glioblastoma. Neurology. 1980;30:907–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.9.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallner KE, Galicich JH, Krol G, Arbit E, Malkin MG. Patterns of failure following treatment for glioblastoma multiforme and anaplastic astrocytoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16:1405–9. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franceschi E, Cavallo G, Scopece L, Paioli A, Pession A, Magrini E, et al. Phase II trial of carboplatin and etoposide for patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1038–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fine HA, Wen PY, Maher EA, Viscosi E, Batchelor T, Lakhani N, et al. Phase II trial of thalidomide and carmustine for patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2299–304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauman GS, Gaspar LE, Fisher BJ, Halperin EC, Macdonald DR, Cairncross JG. A prospective study of short-course radiotherapy in poor prognosis glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;29:835–9. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta T, Sarin R. Poor-prognosis high-grade gliomas:Evolving an evidence-based standard of care. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:557–64. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00853-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marijnen CA, Van den Berg SM, Van Duinen SG, Voormolen JH, Noordijk EM. Radiotherapy is effective in patients with glioblastoma multiforme with a limited prognosis and in patients above 70 years of age:A retrospective single institution analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2005;75:210–6. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roa W, Brasher PM, Bauman G, Anthes M, Bruera E, Chan A, et al. Abbreviated course of radiation therapy in older patients with glioblastoma multiforme:A prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1583–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whittle IR, Basu N, Grant R, Walker M, Gregor A. Management of patients aged >60 years with malignant glioma:Good clinical status and radiotherapy determine outcome. Br J Neurosurg. 2002;16:343–7. doi: 10.1080/02688690021000007650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stewart LA. Chemotherapy in adult high-grade glioma:A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 12 randomised trials. Lancet. 2002;359:1011–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, Van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study:5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–66. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerber DE, Grossman SA, Zeltzman M, Parisi MA, Kleinberg L. The impact of thrombocytopenia from temozolomide and radiation in newly diagnosed adults with high-grade gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:47–52. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2006-024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grossman SA, Ye X, Lesser G, Sloan A, Carraway H, Desideri S, et al. Immunosuppression in patients with high-grade gliomas treated with radiation and temozolomide. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5473–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.NCCN Clinical practice Guidelines in Oncology. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections. Washington: National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN); 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 April]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/infections.pdf . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van den Bent MJ, Erdem-Eraslan L, Idbaih A, De Rooi J, Eilers PH, Spliet WG, et al. MGMT-STP27 methylation status as predictive marker for response to PCV in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas. A report from EORTC study 26951. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5513–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dixit S, Baker L, Walmsley V, Hingorani M. Temozolomide-related idiosyncratic and other uncommon toxicities:A systematic review. Anticancer Drugs. 2012;23:1099–106. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328356f5b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0. [Last accessed on 2016 April]. Available from: http://www.evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/About.html .

- 62.Gilbert MR, Wang M, Aldape KD, Stupp R, Hegi ME, Jaeckle KA, et al. Dose-dense temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma:A randomized phase III clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4085–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Armstrong TS, Wefel JS, Wang M, Gilbert MR, Won M, Bottomley A, et al. Net clinical benefit analysis of radiation therapy oncology group. 0525:A phase III trial comparing conventional adjuvant temozolomide with dose-intensive temozolomide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4076–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C, Felsberg J, Tabatabai G, Simon M, et al. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly:The NOA-08 randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:707–15. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70164-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Omuro A, Beal K, Gutin P, Karimi S, Correa DD, Kaley TJ, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab, temozolomide, and hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5023–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, Henriksson R, Saran F, Nishikawa R, et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:709–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, Wefel JS, Blumenthal DT, Vogelbaum MA, et al. Arandomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taphoorn MJ, Henriksson R, Bottomley A, Cloughesy T, Wick W, Mason WP, et al. Health-related quality of life in a randomized phase III study of bevacizumab, temozolomide, and radiotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2166–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khasraw M, Ameratunga MS, Grant R, Wheeler H, Pavlakis N. Antiangiogenic therapy for high-grade glioma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;22:CD008218. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008218.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malmström A, Grønberg BH, Marosi C, Stupp R, Frappaz D, Schultz H, et al. Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma:The Nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:916–26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Valtonen S, Timonen U, Toivanen P, Kalimo H, Kivipelto L, Heiskanen O, et al. Interstitial chemotherapy with carmustine-loaded polymers for high-grade gliomas:A randomized double-blind study. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:44–8. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199707000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Westphal M, Hilt DC, Bortey E, Delavault P, Olivares R, Warnke PC, et al. Aphase 3 trial of local chemotherapy with biodegradable carmustine (BCNU) wafers (Gliadel wafers) in patients with primary malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2003;5:79–88. doi: 10.1215/S1522-8517-02-00023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Giese A, Kucinski T, Knopp U, Goldbrunner R, Hamel W, Mehdorn HM, et al. Pattern of recurrence following local chemotherapy with biodegradable carmustine (BCNU) implants in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2004;66:351–60. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000014539.90077.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee AW, Kwong DL, Leung SF, Tung SY, Sze WM, Sham JS, et al. Factors affecting risk of symptomatic temporal lobe necrosis:Significance of fractional dose and treatment time. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ohgaki H, Dessen P, Jourde B, Horstmann S, Nishikawa T, Di Patre PL, et al. Genetic pathways to glioblastoma:A population-based study. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6892–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cairncross JG, Ueki K, Zlatescu MC, Lisle DK, Finkelstein DM, Hammond RR, et al. Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1473–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.19.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perry A. Oligodendroglial neoplasms:Current concepts, misconceptions, and folklore. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001;8:183–99. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Juratli TA, Lautenschläger T, Geiger KD, Pinzer T, Krause M, Schackert G, et al. Radio-chemotherapy improves survival in IDH-mutant, 1p/19q non-codeleted secondary high-grade astrocytoma patients. J Neurooncol. 2015;124:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1822-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van den Bent MJ, Brandes AA, Taphoorn MJ, Kros JM, Kouwenhoven MC, Delattre JY, et al. Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine chemotherapy in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma:Long-term follow-up of EORTC brain tumor group study 26951. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:344–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cairncross JG, Wang M, Jenkins RB, Shaw EG, Giannini C, Brachman DG, et al. Benefit from procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine in oligodendroglial tumors is associated with mutation of IDH. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:783–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Van den Bent MJ, Carpentier AF, Brandes AA, Sanson M, Taphoorn MJ, Bernsen HJ, et al. Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine improves progression-free survival but not overall survival in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas:A randomized European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2715–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cairncross G, Berkey B, Shaw E, Jenkins R, Scheithauer B, et al. Intergroup Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial. Phase III trial of chemotherapy plus radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone for pure and mixed anaplastic oligodendroglioma:Intergroup Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial 9402. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2707–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cairncross G, Macdonald D, Ludwin S, Lee D, Cascino T, Buckner J, et al. Chemotherapy for anaplastic oligodendroglioma. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2013–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.10.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.O'Brien BJ, Colen RR. Post-treatment imaging changes in primary brain tumors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2014;16:397. doi: 10.1007/s11912-014-0397-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Chalmers L, Van Horn A, Sloan AE. Early necrosis following concurrent Temodar and radiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:81–3. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9241-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Young RJ, Gupta A, Shah AD, Graber JJ, Zhang Z, Shi W, et al. Potential utility of conventional MRI signs in diagnosing pseudoprogression in glioblastoma. Neurology. 2011;76:1918–24. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821d74e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, Cloughesy TF, Sorensen AG, Galanis E, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas:Response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1963–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Harsh GR, 4th, Levin VA, Gutin PH, Seager M, Silver P, Wilson CB. Reoperation for recurrent glioblastoma and anaplastic astrocytoma. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:615–21. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198711000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barker FG, 2nd, Chang SM, Gutin PH, Malec MK, McDermott MW, Prados MD, et al. Survival and functional status after resection of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:709–20. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kappelle AC, Postma TJ, Taphoorn MJ, Groeneveld GJ, Van den Bent MJ, van Groeningen CJ, et al. PCV chemotherapy for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Neurology. 2001;56:118–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Keles GE, Lamborn KR, Chang SM, Prados MD, Berger MS. Volume of residual disease as a predictor of outcome in adult patients with recurrent supratentorial glioblastomas multiforme who are undergoing chemotherapy. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:41–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.1.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rostomily RC, Spence AM, Duong D, McCormick K, Bland M, Berger MS. Multimodality management of recurrent adult malignant gliomas:Results of a phase II multiagent chemotherapy study and analysis of cytoreductive surgery. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:378–88. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gutin PH, Phillips TL, Wara WM, Leibel SA, Hosobuchi Y, Levin VA, et al. Brachytherapy of recurrent malignant brain tumors with removable high-activity iodine-125 sources. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:61–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.1.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lederman G, Wronski M, Arbit E, Odaimi M, Wertheim S, Lombardi E, et al. Treatment of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme using fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery and concurrent paclitaxel. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000;23:155–9. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200004000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dirks P, Bernstein M, Muller PJ, Tucker WS. The value of reoperation for recurrent glioblastoma. Can J Surg. 1993;36:271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Landy HJ, Feun L, Schwade JG, Snodgrass S, Lu Y, Gutman F. Retreatment of intracranial gliomas. South Med J. 1994;87:211–4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199402000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Young B, Oldfield EH, Markesbery WR, Haack D, Tibbs PA, McCombs P, et al. Reoperation for glioblastoma. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:917–21. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.55.6.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wong ET, Gautam S, Malchow C, Lun M, Pan E, Brem S. Bevacizumab for recurrent glioblastoma multiforme:A meta-analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9:403–7. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, Duic P, Royce C, Stroud I, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:740–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, Mikkelsen T, Schiff D, Abrey LE, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4733–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Taal W, Oosterkamp HM, Walenkamp AM, Dubbink HJ, Beerepoot LV, Hanse MC, et al. Single-agent bevacizumab or lomustine versus a combination of bevacizumab plus lomustine in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (BELOB trial):A randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:943–53. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cloughesy TV. Updated safety and survival of patients with relapsed glioblastoma treated with bevacizumab in the BRAIN study (abstract #2008) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:181s. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Raizer JJ, Grimm S, Chamberlain MC, Nicholas MK, Chandler JP, Muro K, et al. A phase 2 trial of single-agent bevacizumab given in an every-3-week schedule for patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas. Cancer. 2010;116:5297–305. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Brandes AA, Bartolotti M, Tosoni A, Poggi R, Franceschi E. Practical management of bevacizumab-related toxicities in glioblastoma. Oncologist. 2015;20:166–75. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schmidt F, Fischer J, Herrlinger U, Dietz K, Dichgans J, Weller M. PCV chemotherapy for recurrent glioblastoma. Neurology. 2006;66:587–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000197792.73656.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chamberlain MC. Salvage therapy with lomustine for temozolomide refractory recurrent anaplastic astrocytoma:A retrospective study. J Neurooncol. 2015;122:329–38. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1714-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Brada M, Stenning S, Gabe R, Thompson LC, Levy D, Rampling R, et al. Temozolomide versus procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine in recurrent high-grade glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4601–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Perry JR, Bélanger K, Mason WP, Fulton D, Kavan P, Easaw J, et al. Phase II trial of continuous dose-intense temozolomide in recurrent malignant glioma:RESCUE study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2051–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Khan RB, Raizer JJ, Malkin MG, Bazylewicz KA, Abrey LE. A phase II study of extended low-dose temozolomide in recurrent malignant gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2002;4:39–43. doi: 10.1215/15228517-4-1-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Cavallo G, Bertorelle R, Gioia V, Franceschi E, et al. Temozolomide 3 weeks on and 1 week off as first-line therapy for recurrent glioblastoma:Phase II study from gruppo italiano cooperativo di neuro-oncologia (GICNO) Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1155–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wick A, Felsberg J, Steinbach JP, Herrlinger U, Platten M, Blaschke B, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of temozolomide in an alternating weekly regimen in patients with recurrent glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3357–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Abacioglu U, Caglar HB, Yumuk PF, Akgun Z, Atasoy BM, Sengoz M. Efficacy of protracted dose-dense temozolomide in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2011;103:585–93. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kong DS, Lee JI, Kim JH, Kim ST, Kim WS, Suh YL, et al. Phase II trial of low-dose continuous (metronomic) treatment of temozolomide for recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:289–96. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Norden AD, Lesser GJ, Drappatz J, Ligon KL, Hammond SN, Lee EQ, et al. Phase 2 study of dose-intense temozolomide in recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:930–5. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Han SJ, Rolston JD, Molinaro AM, Clarke JL, Prados MD, Chang SM, et al. Phase II trial of 7 days on/7 days off temozolmide for recurrent high-grade glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:1255–62. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]