Abstract

Background and Aims Partially mycoheterotrophic plants are enriched in 13C and 15N compared to autotrophic plants. Here, it is hypothesized that the type of mycorrhizal fungi found in orchid roots is responsible for variation in 15N enrichment of leaf tissue in partially mycoheterotrophic orchids.

Methods The genus Epipactis was used as a case study and carbon and nitrogen isotope abundances of eight Epipactis species, fungal sporocarps of four Tuber species and autotrophic references were measured. Mycorrhizal fungi were identified using molecular methods. Stable isotope data of six additional Epipactis taxa and ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic basidiomycetes were compiled from the literature.

Key Results The 15N enrichment of Epipactis species varied between 3·2 ± 0·8 ‰ (E. gigantea; rhizoctonia-associated) and 24·6 ± 1·6 ‰ (E. neglecta; associated with ectomycorrhizal ascomycetes). Sporocarps of ectomycorrhizal ascomycetes (10·7 ± 2·2 ‰) were significantly more enriched in 15N than ectomycorrhizal (5·2 ± 4·0 ‰) and saprotrophic basidiomycetes (3·3 ± 2·1 ‰).

Conclusions As hypothesized, it is suggested that the observed gradient in 15N enrichment of Epipactis species is strongly driven by 15N abundance of their mycorrhizal fungi; i.e. ɛ15N in Epipactis spp. associated with rhizoctonias < ɛ15N in Epipactis spp. with ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes < ɛ15N in Epipactis spp. with ectomycorrhizal ascomycetes and basidiomycetes < ɛ15N in Epipactis spp. with ectomycorrhizal ascomycetes.

Keywords: Ascomycetes, basidiomycetes, carbon, Epipactis, mycorrhiza, nitrogen, Orchidaceae, partial mycoheterotrophy, stable isotopes, Tuber

INTRODUCTION

Partial mycoheterotrophy (PMH) is a trophic strategy of plants defined as a plant’s ability to obtain carbon (C) simultaneously through photosynthesis and mycoheterotrophy via a fungal source exhibiting all intermediate stages between the extreme trophic endpoints of autotrophy and mycoheterotrophy (Merckx, 2013). However, all so far known partially mycoheterotrophic plants feature a change of trophic strategies during their development. In addition to all fully mycoheterotrophic plants, all species in the Orchidaceae and the subfamily Pyroloideae in the Ericaceae produce minute seeds that are characterized by an undifferentiated embryo and a lack of endosperm. These ‘dust seeds’ are dependent on colonization by a mycorrhizal fungus and supply of carbohydrates to facilitate growth of non-photosynthetic protocorms in this development stage termed initial mycoheterotrophy (Alexander and Hadly, 1985; Leake, 1994; Rasmussen, 1995; Rasmussen and Whigham, 1998; Merckx et al., 2013). At adulthood these initially mycoheterotrophic plants either stay fully mycoheterotrophic (e.g. Neottia nidus-avis) or they become (putatively) autotrophic or partially mycoheterotrophic. With approximately 28^000 species in 736 genera the Orchidaceae is the largest angiosperm family with worldwide distribution constituting almost a tenth of described vascular plant species (Chase et al., 2015; Christenhusz and Byng, 2016) making initial mycoheterotrophy the most widespread fungi-mediated trophic strategy. Nevertheless, PMH has been detected not only in green Orchidaceae species, but also in Burmanniaceae, Ericaceae and Gentianaceae (Zimmer et al., 2007; Hynson et al., 2009; Cameron and Bolin, 2010; Merckx et al., 2013; Bolin et al., 2015).

Analysis of food webs and clarification of trophic strategies with δ13C and δ15N stable isotope abundance values have a long tradition in ecology (DeNiro and Epstein, 1978, 1981). DeNiro and Epstein coined the term ‘you are what you eat – plus a few permil’ (DeNiro and Epstein, 1976) to highlight the systematic increase in the relative abundance of 13C and 15N at each trophic level of a food chain. Gebauer and Meyer (2003) and Trudell et al. (2003) were the first to employ stable isotope natural abundance analyses of C and N to distinguish the trophic level of mycoheterotrophic orchids from surrounding autotrophic plants.

Today, stable isotope analysis together with the molecular identification of fungal partners have become the standard tools for research on trophic strategies in plants, especially orchids (Leake and Cameron, 2010). Since the first discovery of partially mycoheterotrophic orchids (Gebauer and Meyer, 2003), the number of species identified as following a mixed type of trophic strategy has grown continuously (Hynson et al., 2013, 2016; Gebauer et al., 2016). One of the relatively well-studied orchid genera in terms of stable isotopes and molecular identification of mycorrhizal partners is the genus Epipactis Zinn (Bidartondo et al., 2004; Tedersoo et al., 2007; Hynson et al., 2016). Epipactis is a genus of terrestrial orchids comprising 70 taxa (91 including hybrids) (The Plant List, 2013) with a mainly Eurasian distribution. Epipactis gigantea is the only species in the genus native to North America, and Epipactis helleborine is naturalized there. All Epipactis species are rhizomatous and summergreen and they occur in various habitats ranging from open wet meadows to closed-canopy dry forests (Rasmussen, 1995). PMH of several Epipactis species associated with ectomycorrhizal fungi (E. atrorubens, E. distans, E. fibri and E. helleborine) has been elucidated using stable isotope natural abundances of C and N. They all turned out to be significantly enriched in both 13C and 15N (Hynson et al., 2016). Orchid mycorrhizal fungi of the Epipactis species in the above-mentioned studies were ascomycetes and basidiomycetes simultaneously ectomycorrhizal with neighbouring forest trees, and in some cases additionally basidiomycetes belonging to the polyphyletic rhizoctonia group well known as forming orchid mycorrhizas have also been detected (Gebauer and Meyer, 2003; Bidartondo et al., 2004; Abadie et al., 2006; Tedersoo et al., 2007; Selosse and Roy, 2009; Liebel et al., 2010; Gonneau et al., 2014). Epipactis gigantea and E. palustris, the only two Epipactis species colonizing open habitats and exhibiting exclusively an association with rhizoctonias, showed no 13C and only minor 15N enrichment (Bidartondo et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 2007).

The definition of trophic strategies in vascular plants is restricted to an exploitation of C and places mycoheterotrophy into direct contrast to autotrophy. The proportions of C gained by partially mycoheterotrophic orchid species from fungi have been quantified by a linear two-source mixing-model approach (Gebauer and Meyer, 2003; Preiss and Gebauer, 2008; Hynson et al., 2013). Variations in percental C gain of partially mycoheterotrophic orchids from the fungal source are driven by plant species identity placing, for example, the leafless Corallorhiza trifida closely towards fully mycoheterotrophic orchids (Zimmer et al., 2008; Cameron et al., 2009) and by physiological and environmental variables such as leaf chlorophyll concentration (Stöckel et al., 2011) and light climate of their microhabitats (Preiss et al., 2010). Carbon gain in the orchid species Cephalanthera damasonium, for example, can range from 33 % in an open pine forest to about 85 % in a dark beech forest (Gebauer, 2005; Hynson et al., 2013).

Far less clear is the explanation of variations in 15N enrichment found for fully, partially and initially mycoheterotrophic plants, but also for putatively autotrophic species (Gebauer and Meyer, 2003; Abadie et al., 2006; Tedersoo et al., 2007; Preiss and Gebauer, 2008; Selosse and Roy, 2009; Liebel et al., 2010, Hynson et al., 2013). This 15N enrichment was found to be not linearly related to the degree of heterotrophic C gain (Leake and Cameron 2010; Merckx et al., 2013). Using the linear two-source mixing-model approach to obtain quantitative information of the proportions of N gained by partially mycoheterotrophic orchid species from the fungal source, some species even exhibited an apparent N gain above 100 % (Hynson et al., 2013). Reasons for this pattern remained unresolved and could just be explained by lacking coverage of variability in 15N signatures of the chosen fully mycoheterotrophic endpoint due to different fungal partners (Preiss and Gebauer, 2008; Hynson et al., 2013).

Here, we hypothesize that the type of mycorrhizal fungi in the roots of orchid species (i.e. ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes, ectomycorrhizal ascomycetes or basidiomycetes of the rhizoctonia group) is responsible for the differences in 15N enrichment measured in leaf bulk tissue. We used the genus Epipactis as case study due to already existing literature on their mycorrhizal partners and natural abundance stable isotope values and extended the data to six additional Epipactis taxa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study locations and sampling scheme

Eight Epipactis taxa were sampled at nine sites in the Netherlands and Germany in July 2014 following the plot-wise sampling scheme proposed by Gebauer and Meyer (2003). Leaf samples from flowering individuals of all Epipactis species in this survey were taken in five replicates (resembling five 1-m2 plots) together with three autotrophic non-orchid, non-leguminous reference plant species each (listed in Supplementary Data Table S1). Epipactis helleborine (L.) Crantz and E. helleborine subsp. neerlandica (Verm.) Buttler were sampled at three locations in the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. Epipactis helleborine was collected at ruderal site 1 (52°0′N, 4°21′E) dominated by Populus × canadensis Moench. and forest site 2 (52°11′N, 4°29′E at 1 m elevation) dominated by Fagus sylvatica L. Epipactis helleborine subsp. neerlandica was collected at dune site 3 (52°8′N, 4°20′E at 10 m elevation), an open habitat with sandy soil dominated by Salix repens L. and Quercus robur L. Samples of E. microphylla (Ehrh.) Sw. and E. pupurata Sm. were collected from two sites (forest sites 4 and 5) with thermophilic oak forest dominated by Quercus robur south of Bamberg, north-east Bavaria, Germany (49°50′–49°51′N, 10°52′–11°02′E at 310–490 m elevation). Epipactis distans Arv.-Touv., E. leptochila (Godfery) Godfery, E. muelleri Godfery and E. neglecta (Kümpel) Kümpel (Fig. 1a) were collected at four sites (forest sites 6–9) dominated by dense old-growth stands of Fagus sylvatica with a sparse cover of understorey vegetation in the Nördliche Frankenalb, north-east Bavaria, Germany (49°35′–49°39′N, 11°23′–11°28′E at 450–550 m elevation). Sampling yielded a total of 45 leaf samples from eight Epipactis species and 135 leaf samples from 17 neighbouring autotrophic reference species (Table S1).

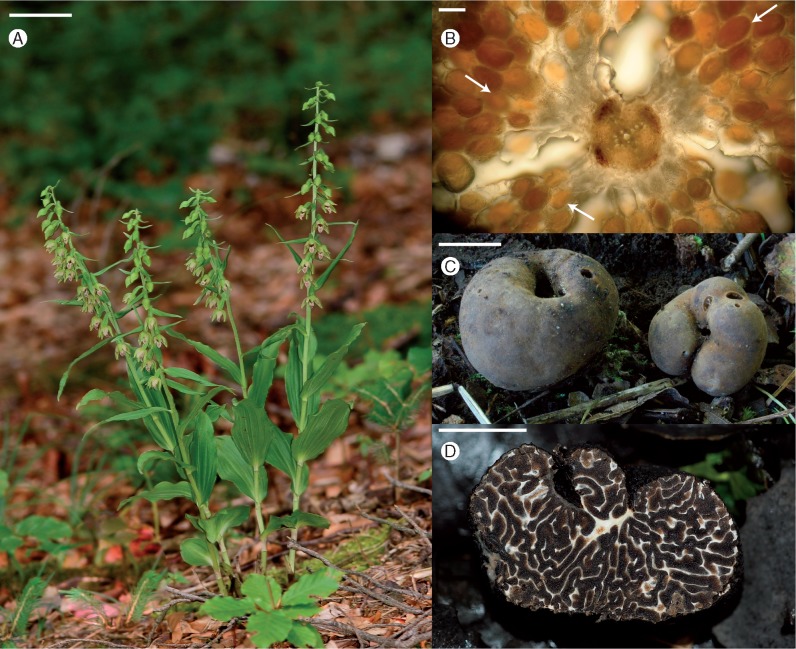

Fig. 1.

(A) Epipactis neglecta at forest site 9 in the Nördliche Frankenalb in July 2009. Scale bar = 5 cm. Image courtesy of Florian Fraaß. (B) Light micrograph showing a transverse section of a root of Epipactis neglecta. Fungal colonization is visible as exodermal, outer and inner cortex cells filled with fungal hyphae, indicated by white arrows. Scale bar = 100 µm. (C) Ascocarps of Tuber excavatum. Scale bar = 1 cm. (D) Cross-section of an ascocarp of Tuber brumale. Scale bar = 1 cm.

To complete the already existing isotope abundance data of fungal fruit bodies, sporocarps of species in the true truffle ascomycete genus Tuber were sampled opportunistically at forest sites 7–9 and a further adjacent site dominated by Fagus sylvatica (49°40′N, 11°23′E) (Preiss and Gebauer, 2008; Gebauer et al., 2016) in December 2014. In total, 27 hypogeous ascocarps in the four ectomycorrhizal species Tuber aestivum Vittad. (n = 5), Tuber excavatum Vittad. (n = 19) (Fig. 1c), Tuberbrumale Vittad. (n = 1) (Fig. 1d) and Tuber rufum Pico (n = 2) were retrieved with the help of a truffle-hunting dog. Wherever possible, autotrophic plant species were sampled as references together with the sporocarps (n = 25) or were used from the previous sampling of Epipactis specimens from the same sites (n = 45).

Fungal DNA analysis

Of all species besides E. helleborine, two roots per sampled Epipactis individual were cut, rinsed with deionized water, placed in CTAB buffer (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) and stored at –18 °C until further analysis. Root cross-sections (Fig. 1b) were checked for presence and status of fungal pelotons in the cortex cells. Two to six root sections per Epipactis individual were selected for genomic DNA extraction and purification with the GeneClean III Kit (Q-BioGene, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region was amplified with the fungal-specific primer combinations ITS1F/ITS4 and ITS1/ITS4-Tul (Bidartondo and Duckett, 2010). All positive PCR products were purified with ExoProStart (GE Healthcare, Amersham, UK) and sequenced bidirectionally with an ABI3730 Genetic Analyser using the BigDye 3·1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and absolute ethanol/EDTA precipitation. The same protocol was used for molecular analysis of oven-dried fragments of Tuber ascocarps. All DNA sequences were checked and visually aligned with Geneious version 7·4·1 (http://www.geneious.com, Kearse et al., 2012) and compared to GenBank using the BLAST program (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). GenBank accession numbers for all unique DNA sequences are KX354284–KX354297.

Of all individuals of E. helleborine, one root per sampled Epipactis individual was cut, rinsed with deionized water, placed in CTAB buffer and stored at –18 °C until further analysis. The entire root of each Epipactis individual sampled was used for genomic DNA extraction following the protocol of Doyle and Doyle (1987).The nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 2 (nrITS2) region was amplified with the fungal-specific primers fITS7 (Ihrmark et al., 2012) and ITS4 (White et al., 1990). Ion Xpress labels were attached to the primers for individual sample identification. Tags differed from all other tags by at least two nucleotides. Fusion PCRs were performed using the following programme: 98 °C/3 min, 35 cycles of 98 °C/5 s, 55 °C/10 s, 72 °C/30 s, and 72 °C/5 min. One microlitre of DNA template was used in a 25-µL PCR containing 14·3 µL MQ water, 5 µL of 5× buffer, 0·5 µL dNTPs (2·5 mm), 1·25 µL of reverse and forward primers (10 mm), 0·5 µL MgCl2 (25 mm), 0·75 µL BSA (10 mg mL–1) and 0·5 µL Phire II polymerase (5^U µL–1). Primer dimers were removed by using 0·9× NucleoMag NGS Clean-up and Size Select beads (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) to which the PCR products were bound. The beads were washed twice with 70 % ethanol and resuspended in 30 µL TE buffer. Cleaned PCR products were quantified using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer DNA High Sensitivity Chip. An equimolar pool was prepared of the amplicon libraries at the highest possible concentration. This equimolar pool was diluted according to the calculated template dilution factor to target 10–30 % of all positive Ion Sphere particles. Template preparation and enrichment were carried out with the Ion OneTouch system, using the OT2 400 Kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol 7218RevA0. The quality control of the Ion OneTouch 400 Ion Sphere particles was done using the Ion Sphere Quality Control Kit using a Life Qubit 2·0. The enriched Ion Spheres were prepared for sequencing on a Personal Genome Machine (PGM) with the Ion PGM Hi-Q Sequencing Kit as described in protocol 9816RevB0 and loaded on an Ion-318v2 chip (850 cycles per run). The Ion Torrent reads produced were subjected to quality filtering by using a parallel version of MOTHUR v. 1.32.1 (Schloss et al., 2009) installed at the University of Alaska Life Sciences Informatics Portal. Reads were analysed with threshold values set to Q ≥ 25 in a sliding window of 50 bp, no ambiguous bases, and homopolymers no longer than 8 bp. Reads shorter than 150 bp were omitted from further analyses. The number of reads for all samples was normalized and the filtered sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97 % sequence similarity cut-off using OTUPIPE (Edgar et al., 2011). Putatively chimeric sequences were removed using a curated dataset of fungal nrITS sequences (Nilsson et al., 2008). We also excluded all singletons from further analyses. For identification, sequences were submitted to USEARCH (Edgar, 2010) against the latest release of the quality checked UNITE+INSD fungal nrITS sequence database (Kõljalg et al., 2013). Taxonomic identifications were based on the current Index Fungorum classification as implemented in UNITE.

Stable isotope abundance and N concentration analysis

Leaf samples of eight Epipactis taxa (n = 45) and autotrophic references (n = 160) were washed with deionized water and Tuber ascocarps (n = 27) were surface-cleaned of adhering soil. All samples were dried to constant weight at 105 °C, ground to a fine powder in a ball mill (Retsch Schwingmühle MM2, Haan, Germany) and stored in a desiccator fitted with silica gel until analysis. Relative C and N isotope natural abundances of the leaf and sporocarp samples were measured in dual element analysis mode with an elemental analyser (Carlo Erba Instruments 1108, Milano Italy) coupled to a continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (delta S Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) via a ConFlo III open-split interface (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) as described by Bidartondo et al. (2004). Measured relative isotope abundances are denoted as δ values that were calculated according to the following equation: δ13C or δ15N = (Rsample/Rstandard–1) × 1000 [‰], where Rsample and Rstandard are the ratios of heavy to light isotope of the samples and the respective standard. Standard gases were calibrated with respect to international standards (CO2 vs PDB and N2 vs N2 in air) by use of the reference substances ANU sucrose and NBS19 for the carbon isotopes and N1 and N2 for the nitrogen isotopes provided by the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria). Reproducibility and accuracy of the isotope abundance measurements were routinely controlled by measuring the laboratory standard acetanilide (Gebauer and Schulze, 1991). Acetanilide was routinely analysed with variable sample weight at least six times within each batch of 50 samples. The maximum variation of δ13C and δ15N both within and between batches was always below 0·2 ‰.

Total N concentrations in leaf and sporocarp samples were calculated from sample weights and peak areas using a six-point calibration curve per sample run based on measurements of the laboratory standard acetanilide with a known N concentration of 10·36 % (Gebauer and Schulze, 1991).

Literature survey

We compiled C and N stable isotope natural abundance and nitrogen concentration data of five additional Epipactis species and their autotrophic references from all available publications (Gebauer and Meyer, 2003; Bidartondo et al., 2004; Abadie et al., 2006; Zimmer et al., 2007; Tedersoo et al., 2007; Liebel et al., 2010; Johansson et al., 2014; Gonneau et al., 2014): Epipactis atrorubens (Hoffm.) Besser (n = 11), Epipactis distans Arv.-Touv. (n = 4), Epipactis fibri Scappat. and Robatsch (n = 29), Epipactis gigantea Douglas ex. Hook (n = 5) and Epipactis palustris (L.) Crantz (n = 4) and additional data points of Epipactis helleborine (L.) Crantz (n = 21) and Epipactis leptochila (Godfery) Godfery (n = 4) yielding a total of 78 further data points for the genus Epipactis and 161 data points for 26 species of photosynthetic non-orchid references (Supplementary Data Table S2).

The C and N stable isotope and nitrogen concentration data of 11 species of ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes (n = 37) and four species of saprotrophic basidiomycetes (n = 17) sampled opportunistically at forest site 10 were extracted from Gebauer et al. (2016) (Table S2).

A separate literature survey was conducted to compile fungal partners forming orchid mycorrhiza with the Epipactis species E. atrorubens, E. distans, E. fibri, E. gigantea, E. helleborine, E. helleborine subsp. neerlandica, E. microphylla, E. palustris and E. purpurata (from Bidartondo et al., 2004; Selosse et al., 2004; Bidartondo and Read, 2008; Ogura-Tsujita and Yukawa, 2008; Ouanphanivanh et al., 2008; Shefferson et al., 2008; Illyés et al., 2009; Tĕšitelová et al., 2012; Jacquemyn et al., 2016) (Table S3).

Calculations and statistics

To enable comparisons of C and N stable isotope abundances between the Epipactis species sampled for this study, data from the literature and fungal sporocarps, we used an isotope enrichment factor approach to normalize the data. Normalized enrichment factors (ε) were calculated from measured or already published δ values as ε = δS − δREF, where δS is a single δ13C or δ15N value of an Epipactis individual, a fungal sporocarp or an autotrophic reference plant, and δREF is the mean value of all autotrophic reference plants by plot (Preiss and Gebauer, 2008). Enrichment factor calculations for sporocarps of ectomycorrhizal ascomycetes (ECM A), ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes (ECM B) and saprotrophic basidiomycetes (SAP) sampled at forest site 10 were enabled by extracting stable isotope data of autotrophic references from previous studies (n = 158) (Gebauer and Meyer, 2003; Bidartondo et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 2007, 2008; Preiss et al., 2010; Gebauer et al., 2016). The δ13C and δ15N values, enrichment factors ε13C and ε15N, and N concentrations of eight Epipactis species, sporocarps of ECM ascomycetes (ECM A) and autotrophic references from this study and six Epipactis species, sporocarps of ECM basidiomycetes (ECM B), saprotrophic basidiomycetes (SAP) and autotrophic references from the literature are available in Tables S1 and Table S2, respectively.

We tested for pairwise differences in isotopic enrichment factors (ε13C and ε15N) and N concentrations between the Epipactis species and their corresponding autotrophic reference plants using a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test. We repeated the Mann–Whitney U-test to test for pairwise differences between fungal sporocarps and autotrophic references in ε13C, ε15N and N concentrations. We used the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis H-test in combination with a post-hoc Mann–Whitney U-test for multiple comparisons to test for differences in isotopic enrichment factors and N concentrations between sporocarps of ECM A, ECM B and SAP. The P values were adjusted using the sequential Bonferroni correction (Holm, 1979). For statistical analyses we used the software environment R [version 3.1.2 (Pumpkin Helmet) (R Development Core Team, 2014)] with a significance level of α = 0·05.

RESULTS

Fungal DNA analysis

Pelotons apparent as dense coils of fungal hyphae were not visible in all roots of the 31 Epipactis individuals examined. Yet for all Epipactis species studied here, associations with ectomycorrhizal (ECM) non-rhizoctonia fungi were found. All eight Epipactis species investigated here were associated with obligate ECM B [Inocybe (Fr.) Fr., Russula Pers., Sebacina epigaea (Berk. and Broome) Neuhoff] or obligate ECM A (Tuber, Wilcoxina) (Table 1). Epipactis helleborine was associated with both obligate ECM B and ECM A at the two sites, but for its subspecies neerlandica only ECM B Inocybe could be identified as a fungal partner. The obligate ECM B Sebacina epigaea and ECM A Cadophora Lagerb. and Melin were associated with E. microphylla. The obligate ECM basidiomycetes Russula heterophylla (Fr.) Fr. and Inocybe were detected in the roots of E. purpurata at forest site 5. Roots of E. distans were colonized by the obligate ECM A Wilcoxina rehmii Chin S. Yang and Korf. Epipactis leptochila and E. neglecta formed orchid mycorrhizas exclusively with the ECM A Tuber excavatum and E. muelleri associated with Tuber puberulum Berk. and Broome.

Table 1.

Orchid mycorrhizal fungi identified from roots of seven Epipactis species from nine sites in Germany and the Netherlands (ECM A = ascomycetes forming ectomycorrhizas, ECM B = basidiomycetes forming ectomycorrhizas); L is Ellenberg’s light indicator value (Ellenberg et al., 1991) and n is the number of Epipactis individuals sampled

| Species | L | Site | n | Pelotons | Mycorrhizal fungi | Type of mycorrhizal fungi | Best match sequence/ accession number (UDB-UNITE, others GenBank) | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epipactis helleborine (L.) Crantz* | 3 | Ruderal site 1 | 1 | NA | Helotiales | ECM A | DQ182433 uncul. Helotiales | 98·9 |

| NA | Inocybe sp. | ECM B | HE601882·1 uncul. Inocybe | 99·4 | ||||

| NA | Sebacina sp. | ECM B | UDB013653 Sebacina | 99·7 | ||||

| Epipactis helleborine (L.) Crantz* | 3 | Forest site 2 | 1 | NA | Thelephoraceae | ECM B | UDB013578 Tomentella-Thelephora | 97·7 |

| NA | Helotiales | ECM A | DQ182433 uncul. Helotiales | 98·9 | ||||

| NA | Tomentella sp. | ECM B | AJ879656·1 uncul. Ectomycorrhiza (Tomentella) | 96·5 | ||||

| NA | Inocybe sp. | ECM B | JX630876 uncul. Inocybe | 98·5 | ||||

| NA | Tuber rufum | ECM A | EF362475 Tuber rufum | 100 | ||||

| NA | Inocybe sp. | ECM B | HE601882·1 uncul. Inocybe | 99·4 | ||||

| NA | Tuber sp. | ECM A | AJ510273 uncul. Tuber sp. | 99·6 | ||||

| NA | Sebacina sp. | ECM B | UDB007522 Sebacina | 99·6 | ||||

| Epipactis helleborine subsp. neerlandica (Verm.) Buttler | NA | Dune site 3 | 1 | no | Inocybe sp. | ECM B | JF908119·1 Inocybe splendens | 90 |

| Epipactis microphylla (Ehrh.) Sw. | 2 | Forest site 4 | 5 | yes | Sebacina epigaea | ECM B | KF000457·1 Sebacina epigaea | 100 |

| yes | Cadophora sp. | ECM A | JN859252·1 Cadophora sp. | 99 | ||||

| Epipactis purpurata Sm. | 2 | Forest site 5 | 5 | no | Russula heterophylla | ECM B | DQ422006·1 Russula heterophylla | 99 |

| no | Inocybe sp. | ECM B | KF679811·1 Inocybe sp. | 91 | ||||

| Epipactis distans Arv.-Touv. | NA | Forest site 6 | 5 | yes | Wilcoxina rehmii | ECM A | DQ069001·1 Wilcoxina rehmii | 99 |

| Epipactis leptochila (Godfery) Godfery | 3 | Forest site 7 | 5 | yes | Tuber excavatum | ECM A | HM151977·1 Tuber excavatum var. intermedium | 99 |

| yes | Tuber excavatum | ECM A | HM151993·1 Tuber excavatum | 99 | ||||

| Epipactis muelleri Godfery | 7 | Forest site 8 | 5 | yes | Tuber puberulum | ECM A | FN433157·1 Tuber puberulum | 100 |

| AF106891·1 Tuber oligospermum | 99 | |||||||

| Epipactis neglecta (Kümpel) Kümpel | NA | Forest site 9 | 5 | yes | Tuber excavatum | ECM A | HM151977·1 Tuber excavatum var. intermedium | 99 |

Data from Ion Torrent sequencing.

The species identities of the true truffles determined by macroscopic and microscopic identification could be confirmed by nrITS sequencing and BLAST analysis (Table 2). Tuber excavatum extracted from the roots of E. leptochila at forest site 7 and T. excavatum ascocarps collected from the same site had identical nrITS sequences and could be the same genets. The nrITS sequences of T. excavatum var. intermedium extracted from the roots of E. neglecta at forest site 9 and sporocarps of T. excavatum var. intermedium from the same site were also identical.

Table 2.

Molecular identification of Tuber sporocarps collected at four forest sites in Germany

| Species | Site | Best match sequence/accession number (UDB-UNITE, others GenBank) | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tuber aestivum Vittad. | Forest site 8 | JF926117·1 Tuber aestivum | 99 |

| Forest site 10 | JQ348411·1 Tuber aestivum | 98 | |

| Tuber brumale Vittad. | Forest site 10 | NA | NA |

| Tuber excavatum Vittad. | Forest site 7 | HM151993·1 Tuber excavatum | 99 |

| Forest site 8 | HM151982·1 Tuber excavatum | 99 | |

| Forest site 9 | HM151977·1 Tuber excavatum var. intermedium | 99 | |

| Tuber rufum Pico | Forest site 8 | AF106892·1 Tuber rufum | 98 |

| Forest site 10 | AF132506·1 Tuber ferrugineum | 99 |

Stable isotope abundance and N concentration analysis

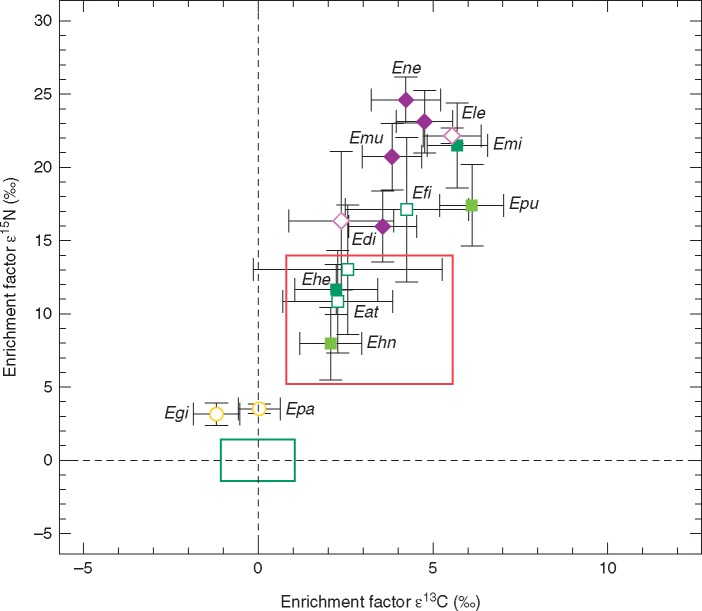

Pairwise Mann–Whitney U-tests showed that all Epipactis species sampled in this study were significantly enriched in 13C and 15N relative to their respective autotrophic reference species (Fig. 2, Table 3). Enrichment of the Epipactis species in this survey varied between 2·07 ± 0·89 ‰ (E. helleborine subsp. neerlandica) and 6·11 ± 0·91 ‰ (E. purpurata) in 13C and between 7·98 ± 2·46 ‰ (E. helleborine subsp. neerlandica) and 24·60 ± 1·57 ‰ (E. neglecta) in ε15N (Table S1). Epipactis helleborine, E. helleborine subsp. neerlandica, E. purpurata, E. distans, E. leptochila, E. muelleri and E. neglecta (µ = 2·38 ± 0·44 mmol g d. wt−1) had significantly higher N concentrations than their respective autotrophic references (µ = 1·42 ± 0·32 mmol g d. wt−1). N concentrations in the leaves of E. microphylla (1·51 ± 0·32 mmol g d. wt−1) were only slightly but not significantly higher than the species’ references (1·34 ± 0·25 mmol g d. wt−1) (U = 48; P = 0·395) (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Mean enrichment factors ε13C and ε15N ± 1 s.d. of two Epipactis species associated with rhizoctonia fungi (yellow circles; Egi = E. gigantea, Epa = E. palustris), two Epipactis species associated with ECM basidiomycetes (light green squares; Ehn = E. helleborine ssp. neerlandica, Epu = E. purpurata), four Epipactis species associated with ECM ascomycetes and basidiomycetes (dark green squares; Eat = E. atrorubens, Ehe = E. helleborine, Efi = E. fibri; Emi = E. microphylla) and four Epipactis species forming orchid mycorrhizas exclusively with ectomycorrhizal ascomycetes (purple diamonds; Edi = E. distans, Ele = E. leptochila, Emu = E. muelleri, Ene = E. neglecta). All open symbols indicate isotope data extracted from the literature (Tables S2). The green box represents mean enrichment factors ±1 s.d. for the autotrophic reference plants that were sampled together with the Epipactis species (REF, n = 296, see Tables S1 and S2) whereas mean ε values of reference plants are zero by definition. The red box represents mean enrichment factors ±1 s.d. of all partially mycoheterotrophic orchid species associated with ectomycorrhizal fungi (ε13Cmean = 3·18 ± 2·38 and ε15Nmean = 9·61 ± 4·40) published since 2003 that were available from the literature (Hynson et al., 2016).

Table 3.

Results from pairwise comparisons for enrichment factors ε15N, ε13C and nitrogen concentration (mmol g d. wt–1) between Epipactis species and sporocarps of ECM ascomycetes, ECM basidiomycetes and SAP fungi and their autotrophic references using the Mann-Whitney U-test

| Species | ε15N |

ε13C |

N concentration |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | P | U | P | U | P | |

| Epipactis helleborine (L.) Crantz | 300 | <0·001 | 265 | <0·001 | 280 | <0·001 |

| Epipactis helleborine subsp. neerlandica (Verm.) Buttler | 75 | <0·001 | 67 | 0·008 | 66 | 0·011 |

| Epipactis microphylla (Ehrh.) Sw. | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 | 48 | 0·395 |

| Epipactis purpurata Sm. | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 |

| Epipactis distans Arv.-Touv. | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 | 73 | <0·001 |

| Epipactis leptochila (Godfery) Godfery | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 |

| Epipactis muelleri Godfery | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 |

| Epipactis neglecta (Kümpel) Kümpel | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 | 75 | <0·001 |

| Epipactis atrorubens (Hoffm.) Besser* | 275 | <0·001 | 246 | <0·001 | 275 | <0·001 |

| Epipactis distans Arv.-Touv.* | 48 | 0·004 | 47 | 0·002 | 45 | 0·008 |

| Epipactis fibri Scappat. and Robatsch* | 348 | <0·001 | 344 | <0·001 | 287·5 | 0·001 |

| Epipactis gigantea Douglas ex Hook.* | 93·5 | 0·003 | 14 | 0·017 | 99 | <0·001 |

| Epipactis helleborine (L.) Crantz* | 1596 | <0·001 | 1329 | <0·001 | 1469 | <0·001 |

| Epipactis leptochila (Godfery) Godfery* | 16 | 0·029 | 16 | 0·029 | 16 | 0·029 |

| Epipactis palustris (L.) Crantz* | 48 | 0·001 | 26 | 0·862 | NA | NA |

| Sporocarps of ECM ascomycetes | 6155 | <0·001 | 6132 | <0·001 | 5549 | <0·001 |

| Sporocarps of ECM basidiomycetes | 5209 | <0·001 | 5835 | <0·001 | 4776 | <0·001 |

| Sporocarps of SAP fungi | 2300 | <0·001 | 2686 | <0·001 | 2302 | <0·001 |

Epipactis species for which data have been extracted from the literature.

For data of Epipactis species extracted from the literature, pairwise tests confirmed significant enrichment of E. atrorubens, E. distans, E. fibri, E. leptochila and E. helleborine in both ε13C and 15N relative to their autotrophic references (Table 3). For E. palustris a significant enrichment in 15N was detected (U = 48; P = 0·001) but not for 13C (U = 26; P = 0·862). Epipactis gigantea was significantly depleted in 13C (U = 14; P = 0·017) and enriched in 15N (U = 93·5; P = 0·003) relative to autotrophic references. Enrichment of the Epipactis species compiled from the literature varied between −1·19 ± 0·66 ‰ (E. gigantea) and 4·25 ± 1·77 ‰ (E. fibri) in 13C and between 3·15 ± 0·75 ‰ (E. gigantea) and 22·16 ± 0·49 ‰ (E. leptochila) in 15N (Table S2). The N concentrations of all Epipactis species extracted from the literature (µ = 2·70 ± 0·69 mmol g d. wt−1) were significantly higher than of leaves of their autotrophic reference plant species (µ = 1·38 ± 0·72 mmol g d. wt−1) (Table 3; Table S2). No N concentration data were available for E. palustris.

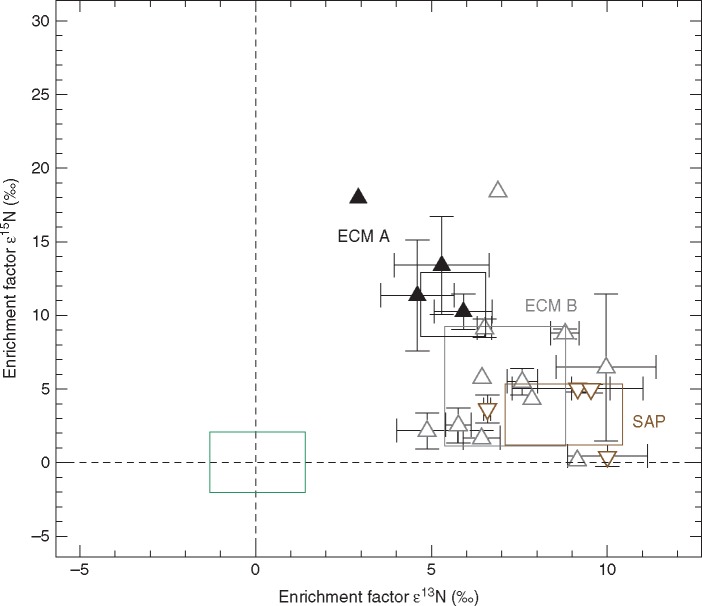

Pairwise Mann–Whitney U-tests showed that sporocarps of ECM A, ECM B and SAP were significantly enriched in 13C and 15N relative to their respective autotrophic reference species (Table 3). Enrichment factors of ascocarps of the obligate ECM A ranged between 3·51 ‰ (T. brumale) and 5·90 ± 0·71 ‰ (T. excavatum) for 13C and between 10·12 ± 1·25 ‰ (T. excavatum) and 16·74 (T. brumale) for 15N (Table S1). A non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis H-test showed that sporocarps of Tuber species were significantly more enriched in 15N than the sporocarps of obligate ECM B (P < 0·001) and sporocarps of SAP (P < 0·001). 15N enrichment of ECM and SAP was not significantly different (P = 0·61). Sporocarps of SAP were more enriched in 13C than the sporocarps of both ECM B (P = 0·008) and ECM A (P < 0·001). The 13C enrichment of sporocarps of ECM B was also significantly higher than of ECM A (P < 0·001). Average enrichment of the sporocarps of obligate ECM A was 5·62 ± 0·93 ‰ in 13C and 10·74 ± 2·18 ‰ in 15N and for the sporocarps of the obligate ECM B was 7·10 ± 1·73 ‰ in 13C and 5·19 ± 4·04 ‰ in 15N. Sporocarps of SAP were enriched by 3·26 ± 2·07 ‰ in 15N and 8·77 ± 1·67 ‰ in 13C.

Sporocarps of all fungal types (ECM A: x̄ = 2·90 ± 0·38 mmol g d. wt−1; ECM B: x̄ = 2·81 ± 0·95 mmol g d. wt−1; SAP: x̄ = 4·783 ± 1·854 mmol g d. wt−1) had significantly higher N concentrations than their autotrophic reference plant species (x̄ = 1·54 ± 0·40 mmol g d. wt−1) (ECM A: U = 5549; P < 0·001; ECM B: U = 4776; P < 0·001; SAP: U = 2302; P < 0·001) but no significant differences could be detected in the N concentrations of sporocarps of obligate ECM A and ECM B (P = 0·199). The N concentrations of sporocarps of SAP were significantly higher than in ECM A (P = 0·042) and ECM B (P = 0·006).

DISCUSSION

Fungal DNA analysis and stable isotope natural abundances – Epipactis species

In this study we provide the first stable isotope data for E. helleborine subsp. neerlandica, E. purpurata, E. microphylla, E. muelleri and E. neglecta. We infer PMH as the nutritional mode of these Epipactis species associated with ECM fungi for the first time as they are significantly enriched in 13C relative to their autotrophic reference plants (Fig. 2, Table 3) but show a smaller 13C enrichment than fully mycoheterotrophic Orchidaceae (8·03 ± 0·13 ‰ in Hynson et al., 2016). Furthermore, we confirm the PMH shown for E. distans, E. helleborine and E. leptochila in earlier studies (Gebauer and Meyer, 2003; Bidartondo et al., 2004; Abadie et al., 2006; Liebel et al., 2010; Johansson et al., 2014; Hynson et al., 2016). Differences in 13C enrichment between the individual species might be driven by the respective plant species identity or morphology with, for example, E. microphylla having rather narrow leaves and thus a smaller total photosynthetic surface area making this Epipactis species more reliant on fungal carbon. Furthermore, the light climate at a respective site is usually mirrored in the 13C enrichment in leaf tissue of orchid species partnering with ECM fungi: 13C enrichment is correlated with decreasing light availability as the proportion of carbon derived from fungi increases in partially mycoheterotrophic orchids associated with ECM fungi (Preiss et al., 2010). Epipactis microphylla and E. purpurata, which were sampled from closed-canopy oak forests, exhibit the highest 13C enrichment and are characterized by a low Ellenberg light indicator value (L) of 2 typical for shade plants (Ellenberg et al., 1991). The value of L ranges from 1 to 9, where 1 indicates plants growing in deep shade (1–30 % light availability relative to irradiance above the forest canopy) and 9 indicates plants growing in full light (>50 % light availability relative to irradiance above the canopy) (Ellenberg et al., 1991). Epipactis leptochila (L 3), E. neglecta, E. muelleri (L 7) and E. distans exhibited a slightly lesser enrichment in 13C, mirroring the light-limited conditions of dense Fagus sylvatica stands. Epipactis helleborine (L 3) and E. helleborine subsp. neerlandica showed only minor enrichment in 13C owing to the relatively open conditions of a ruderal site and a sand dune habitat. The 13C enrichment in E. distans, E. fibri, E. helleborine and E. atrorubens (L 6) calculated from published data was intermediate with high standard deviations probably owing to sampling at several habitats with different light regimes. Epipactis gigantea and E. palustris (L 8) sampled from open habitats showed no significant enrichment in 13C, reflecting high light availability and rhizoctonias as fungal partners (Bidartondo et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 2007).

For the observed gradient in 15N enrichment we infer a strong relationship between the specific fungal host group and the respective Epipactis species. The 15N enrichment in orchids arises as a result of receiving N mobilized and assimilated by fungi from different sources (Gebauer and Meyer, 2003; Bidartondo et al., 2004). We can differentiate the status of 15N enrichment of Epipactis species according to the mycorrhizal fungi associated with the Epipactis species.

Epipactis gigantea and E. palustris, the only Epipactis species solely associated with rhizoctonia fungi, exhibit minor but significant enrichment in 15N (Bidartondo et al., 2004; Zimmer et al., 2007). Epipactis helleborine subsp. neerlandica associated with the ECM B Inocybe (Table 1) shows a modest enrichment in 15N that lies in the range documented for orchid species associated with ECM fungi in general (Hynson et al., 2016). An exception here is E. purpurata shown to partner with the ECM B Russula heterophylla and Inocybe sp., exhibiting high 15N enrichment (Table 1). However, the ECM A Wilcoxina has also been documented in a previous study to host E. purpurata (Tĕšitelová et al., 2012) and may have been missed here. Epipactis species such as E. atrorubens and E. helleborine associated with a wide array of both ECM A and ECM B (Table 3) show a modest enrichment in 15N in the same range. The 15N enrichment in E. fibri and E. microphylla that mainly partner with Tuber species in addition to a wide array of ECM B and ECM A is even above the so far documented mean 15N enrichment of all orchid species associated with ECM fungi. However, it remains unclear which proportion of fungal N might originate from which exact fungal partner in Epipactis taxa that associate with several different mycorrhizal fungi. We detected the highest 15N enrichment in E. distans, E. muelleri, E. leptochila and E. neglecta for which we exclusively identified ECM A such as Wilcoxina rehmii and Tuber (Table 1). Such a high enrichment in 15N has never been documented before for any other orchid species regardless of fungal partner. Nevertheless, both the mean 15N enrichment of 7·5 ‰ of Epipactis species exclusively associated with ECM B relative to sporocarps of ECM B and the mean 15N enrichment of 9·6 ‰ of Epipactis species exclusively associated with ECM A relative to sporocarps of ECM A exceed by far the estimated increase of 2·2–3·4 ‰ δ15N in the consumer versus its diet per trophic level in usual food chain interactions (VanderZanden and Rasmussen, 2001; McCutchan et al., 2003; Fry, 2006).

Still, the observed pattern of 15N enrichment correlating with the presence of ECM A as orchid mycorrhizal fungi in a wide set of Epipactis species in our study challenges the conclusion by Dearnaley (2007) that the simple presence of ascomycete fungi in orchid roots does not necessarily indicate a functional association at least in this case study.

Total N concentrations in the leaves of all Epipactis species except of E. microphylla were significantly higher than in the leaves of autotrophic reference species (Table 3; Table S2) and our finding here confirms the overall picture that mean N concentrations in partially mycoheterotrophic Orchidaceae are generally twice as high as in autotrophic plants (Hynson et al., 2016).

Stable isotope natural abundances – fungal species

Our results confirm the findings by Hobbie et al. (2001) and Mayor et al. (2009) that ECM fungi are significantly more enriched in 15N and depleted in 13C than saprotrophic fungi but we here provide further isotopic evidence to distinguish ECM A and ECM B: ECM A are significantly more enriched in 15N and depleted in 13C compared to ECM B (Fig. 3). Possible explanations for the observed pattern lie in the truffle genomic traits (Martin et al., 2010). Fungal genomics allows for a reverse ecology approach, enabling the autecology of a fungal species to be predicted from its genetic repertoire. Tuber melanosporum Vittad., an example of a true truffle species of high economic value and therefore entirely sequenced, has a large genome (125 Mb) but few protein-coding genes (approx. 7500), exhibiting a low similarity to genomes of other already genetically analysed fungi. In their study on genome size of 172 fungal species, Mohanta and Bae (2015) report an average genome size of 46·48 Mb with a mean number of 15^431·51 protein coding genes for basidiomycetes and a mean genome size of 36·91.Mb and 11129·45 protein coding genes for ascomycetes. Furthermore, the sequence similarity of proteins predicted for T. melanosporum was only significant for three out of 7496 predicted proteins compared to other ascomycete species (Martin et al., 2010). The ascomycete phylum separated approx. 450 Mya from other ancestral fungal lineages, indicating why truffles (T. melanosporum in particular) might have a different enzymatic setup (Martin et al., 2010).

Fig. 3.

Mean enrichment factors ε13C and ε15N ± 1 s.d. as calculated for sporocarps of four ECM ascomycete Tuber species (filled black upward triangles), 11 ECM basidiomycete species (open grey upward triangles) and four saprotrophic basidiomycete species (open brown downward triangles). All open symbols indicate data extracted from Gebauer et al. (2016) (Table S2). The green box represents mean enrichment factors ±1 s.d. for the autotrophic reference plants that were sampled at the same sites as the fungal sporocarps (REF, n = 228, see Tables S1 and S2) whereas mean ε values of reference plants are zero by definition. The black, grey and brown boxes represent mean enrichment factors ±1 s.d. of the ECM ascomycetes (ECM A), ECM basidiomycetes (ECM B) and saprotrophic basidiomycetes (SAP), respectively.

We also find that SAP fungi are more enriched in 13C compared to ECM fungi as they act as decomposers whereas ECM fungi receive carbon from their hosts (Mayor et al., 2009; Gebauer et al., 2016). We furthermore observe here that ECM B are more enriched in 13C than ECM A and explain the perceived pattern by a possibly wider suite of decomposing enzymes of ECM B compared to ECM A. For example, the ECM A T. melanosporum has many fewer glycoside hydrolase-encoding genes compared to saprotrophic fungi (Martin et al., 2010).

Here we showed that ECM A of the genus Tuber are significantly more enriched in 15N than ECM B and SAP fungi. Our results confirm the high δ15N values published by Hobbie et al. (2001) for Tuber gibbosum Harkn. (15·1 ‰) and the ECM ascomycete Sowerbyella rhenana (Fuckel) J. Moravec (17·2 ‰) sampled in Oregon, USA, that are to our knowledge the only so far published stable isotope abundance data for ECM ascomycetes. A relationship between an increase in 15N enrichment with increasing soil depth exploitation of fungi and increase of recalcitrance of soil organic matter has previously been shown and corresponds well with the hypogeous nature of the ECM A species from literature records and findings of this study (Nadelhoffer and Fry, 1988; Gebauer and Schulze, 1991; Taylor et al., 1997). Taylor et al. (1997) reported the highest δ15N values for the ECM B Suillus bovinus (L.) Kuntze (11·1 ‰) and Cortinarius traganus var. finitimum Fr. (15·4 ‰), two species of which ECM was reported to occur throughout the organic layer and down into mineral layers of the subsoil (Taylor et al., 1997; Rosling et al., 2003). Furthermore, we hypothesize the existence of a different set of exoenzymes for access to recalcitrant N compounds in soil organic matter for ECM A, providing ECM A access to N sources unavailable for most ECM B. Recalcitrant soil organic matter is known to become increasingly enriched in 15N with ongoing N decomposition (Nadelhoffer and Fry, 1988; Gebauer and Schulze, 1991). Different physiology in soil organic matter decomposition by ECM B and ECM A is a matter for future investigations.

ConclusionS

In summary, we highlight a true functional role of ascomycete fungi in the roots of Epipactis species. This finding emerged from the unique 15N enrichments found for those Epipactis spp. associated solely with ECM A and the simultaneous finding of unique 15N enrichment of ascomycete sporocarps. Based on this finding we also conclude that the linear two-source mixing model approach to estimate N gains from the fungal source requires knowledge of both the fungal identity and N isotope composition. The relationship between fungal types and 15N enrichment of Epipactis ssp. appears to be as follows: 15N enrichment in Epipactis spp. associated with orchid mycorrhizal rhizoctonias < 15N enrichment in Epipactis spp. associated with ECM B < 15N enrichment in Epipactis spp. associated with ECM A and B < 15N enrichment in Epipactis spp. exclusively associated with ECM A. Thus, we can now no longer exclude that all mycorrhizal orchids, irrespective of the identity of their fungal host, cover all of their N demands through the fungal source. Based on comparisons of 15N enrichments in initially mycohe-terotrophic protocorms and partially mycohe terotrophic adults of E. helleborine, a full coverage of the N demand by partially mycoheterotrophic orchids was proposed by Stöckel et al. (2014). Our findings extend this hypothesis to adults of ten additional species of Epipactis and urge for further studies of other orchid genera.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org and consist of the following. Table S1: single and mean δ15N and δ13C values, single and mean enrichment factors ε15N and ε13C, and single and mean total nitrogen concentration data of all original plant and fungal samples in this study. Table S2: single and mean δ15N and δ13C values, single and mean enrichment factors ε15N and ε13C, and single and mean total nitrogen concentration data of all plant and fungal samples extracted from the literature. Table S3: orchid mycorrhizal fungi detected in the roots of Epipactis species extracted from all available publications

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Christine Tiroch (BayCEER – Laboratory of Isotope Biogeochemistry) for technical assistance with stable isotope abundance measurements and Johannes Schott for sample preparations. We thank Hermann Bösche, Florian Fraass, Adolf Riechelmann, Rogier van Vugt and Theo Westra for information about the locations of the Epipactis species of this survey and truffle-hunting dog ‘Snoopy’ for having such a keen nose. We also thank the Regierung von Oberfranken and the Regierung von Mittelfranken for authorization to collect the orchid and truffle samples. Dutch samples were collected under ‘ontheffing Flora en Faunawet F/75A/2009/038’ and with permission of Harrie van der Hagen (Dunea). This work was supported by the German Research Foundation DFG [GE565/7-2].

LITERATURE CITED

- Abadie J-C, Püttsepp Ü, Gebauer G, Faccio A, Bonfante P, Selosse M-A. 2006. Cephalanthera longifolia (Neottieae, Orchidaceae) is mixotrophic: a comparative study between green and nonphotosynthetic individuals. Canadian Journal of Botany 84: 1462–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C, Hadly G. 1985. Carbon movement between host and mycorrhizal endophyte during the development of the orchid Goodyera repens Br. New Phytologist 101: 657–665. [Google Scholar]

- Bidartondo MI, Duckett JG. 2010. Conservative ecological and evolutionary patterns in liverwort-fungal symbioses. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277: 485–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidartondo MI, Read DJ. 2008. Fungal specificity bottlenecks during orchid germination and development. Molecular Ecology 17: 3707–3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidartondo MI, Burghardt B, Gebauer G, Bruns TD, Read DJ. 2004. Changing partners in the dark: isotopic and molecular evidence of ectomycorrhizal liaisons between forest orchids and trees. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 271: 1799–1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin JF, Tennakoon KU, Bin Abdul Majid M, Cameron DD. 2015. Isotopic evidence of partial mycoheterotrophy in Burmannia coelestis (Burmanniaceae). Plant Species Biology doi:10.1111/1442-1984.12116. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DD, Bolin JF. 2010. Isotopic evidence of partial mycoheterotrophy in the Gentianaceae: Bartonia virginica and Obolaria virginica as case studies. American Journal of Botany 97: 1272–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DD, Preiss K, Gebauer G, Read DJ. 2009. The chlorophyll-containing orchid Corallorhiza trifida derives little carbon through photosynthesis. New Phytologist 183: 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase MW, Cameron KM, Freudenstein JV,. et al. 2015. An updated classification of Orchidaceae. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 177: 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Christenhusz MJM, Byng JW. 2016. The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa 261: 201. [Google Scholar]

- Dearnaley JDW. 2007. Further advances in orchid mycorrhizal research. Mycorrhiza 17: 475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNiro MJ, Epstein S. 1976. You are what you eat (plus a few permil): the carbon isotope cycle in food chains. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs 834–835. [Google Scholar]

- DeNiro MJ, Epstein S. 1978. Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 42: 495–506. [Google Scholar]

- DeNiro M, Epstein S. 1981. Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 45: 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J, Doyle J. 1987. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin 19: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2010. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26: 2460–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. 2011. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27: 2194–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg H, Weber HE, Düll R, Wirth V, Werner W, Paulissen D. 1991. Zeigerwerte von Pflanzen in Mitteleuropa. Scripta Geobotanica 18: 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Fry B. 2006. Stable isotope ecology. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer G. 2005. Partnertausch im dunklen Wald–Stabile Isotope geben neue Einblicke in das Ernährungsverhalten von Orchideen In: Auerswald K, ed. Auf Spurensuche in der Natur: Stabile Isotope in der ökologischen Forschung. Rundgespräche der Kommission für Ökologie Bd. 30. München, Germany: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer G, Meyer M. 2003. 15N and 13C natural abundance of autotrophic and myco-heterotrophic orchids provides insight into nitrogen and carbon gain from fungal association. New Phytologist 160: 209–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer G, Schulze E-D. 1991. Carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios in different compartments of a healthy and a declining Picea abies forest in the Fichtelgebirge, NE Bavaria. Oecologia 87: 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer G, Preiss K, Gebauer AC. 2016. Partial mycoheterotrophy is more widespread among orchids than previously assumed. New Phytologist 211: 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonneau C, Jersáková J, de Tredern E. et al. 2014. Photosynthesis in perennial mixotrophic Epipactis spp. (Orchidaceae) contributes more to shoot and fruit biomass than to hypogeous survival. Journal of Ecology 102: 1183–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie EA, Weber NS, Trappe JM.. 2001. Mycorrhizal vs saprotrophic status of fungi: the isotopic evidence. New Phytologist 150: 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. 1979. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics 6: 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hynson NA, Preiss K, Gebauer G, Bruns TD. 2009. Isotopic evidence of full and partial myco-heterotrophy in the plant tribe Pyroleae (Ericaceae). New Phytologist 182: 719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynson NA, Madsen TP, Selosse M-A, et al. 2013. The physiological ecology of mycoheterotrophy In: Merckx V, ed. Mycoheterotrophy: the biology of plants living on fungi. New York: Springer, 297–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hynson NA, Schiebold JM-I, Gebauer G.. 2016. Plant family identity distinguishes patterns of carbon and nitrogen stable isotope abundance and nitrogen concentration in mycoheterotrophic plants associated with ectomycorrhizal fungi. Annals of Botany 118: 467–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihrmark K, Bödeker ITM, Cruz-Martinez K. et al. 2012. New primers to amplify the fungal ITS2 region - evaluation by 454-sequencing of artificial and natural communities. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 82: 666–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illyés Z, Halász K, Rudnóy S, Ouanphanivanh N, Garay T, Bratek Z. 2009. Changes in the diversity of the mycorrhizal fungi of orchids as a function of the water supply of the habitat. Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality 83: 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemyn H, Waud M, Lievens B, Brys R. 2016. Differences in mycorrhizal communities between Epipactis palustris, E. helleborine and its presumed sister species E. neerlandica. Annals of Botany 118: 105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson VA, Mikusinska A, Ekblad A, Eriksson O.. 2014. Partial mycoheterotrophy in Pyroleae: nitrogen and carbon stable isotope signatures during development from seedling to adult. Oecologia 177: 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, et al. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kõljalg U, Nilsson RH, Abarenkov K, et al. 2013. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Molecular Ecology 22: 5271–5277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake JR. 1994. Tansley Review No. 69 - The biology of myco-heterotrophic (‘saprophytic’) plants. New Phytologist 127: 171–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake JR, Cameron DD. 2010. Physiological ecology of mycoheterotrophy. New Phytologist 185: 601–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebel HT, Bidartondo MI, Preiss K. et al. 2010. C and N stable isotope signatures reveal constraints to nutritional modes in orchids from the Mediterranean and Macaronesia. American Journal of Botany 97: 903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, Kohler A, Murat C. et al. 2010. Périgord black truffle genome uncovers evolutionary origins and mechanisms of symbiosis. Nature 464: 1033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor JR, Schuur EA, Henkel TW. 2009. Elucidating the nutritional dynamics of fungi using stable isotopes. Ecology Letters 12: 171–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutchan JH, Lewis WM Jr, Kendall C, McGrath CC. 2003. Variation in trophic shift for stable isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. Oikos 102: 378–390. [Google Scholar]

- Merckx VSFT. 2013. Mycoheterotrophy: an introduction In: Merckx V, ed. Mycoheterotrophy: the biology of plants living on fungi. New York: Springer, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Merckx VSFT, Freudenstein J V, Kissling J. et al. 2013. Taxonomy and classification In: Merckx V, ed. Mycoheterotrophy: the biology of plants living on fungi. New York: Springer, 19–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanta TK, Bae H. 2015. The diversity of fungal genome. Biological Procedures Online 17: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadelhoffer KJ, Fry B. 1988. Controls on natural nitrogen-15 and carbon-13 abundances in forest soil organic matter. Soil Science Society of America Journal 52: 1633–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson RH, Kristiansson E, Ryberg M, Hallenberg N, Larsson K-H. 2008Intraspecific ITS variability in the Kingdom Fungi as expressed in the international sequence databases and its implications for molecular species identification. Evolutionary Bioinformatics 4: 193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura-Tsujita Y, Yukawa T. 2008. Epipactis helleborine shows strong mycorrhizal preference towards ectomycorrhizal fungi with contrasting geographic distributions in Japan. Mycorrhiza 18: 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouanphanivanh N, Merényi Z, Orczán ÁK, Bratek Z, Szigeti Z, Illyés Z. 2008. Could orchids indicate truffle habitats? Mycorrhizal association between orchids and truffles. Acta Biologica Szegediensis 52: 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Preiss K, Gebauer G. 2008. A methodological approach to improve estimates of nutrient gains by partially myco-heterotrophic plants. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies 44: 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss K, Adam IKU, Gebauer G. 2010. Irradiance governs exploitation of fungi: fine-tuning of carbon gain by two partially myco-heterotrophic orchids. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277: 1333–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. 2014. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen HN. 1995. Terrestrial orchids from seed to mycotrophic plant. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen HN, Whigham DF. 1998. The underground phase: a special challenge in studies of terrestrial orchid populations. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 126: 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rosling A, Landeweert R, Lindahl BD, et al. 2003. Vertical distribution of ectomycorrhizal fungal taxa in a podzol soil profile. New Phytologist 159: 775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T,. et al. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75: 7537–7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selosse M-A, Roy M. 2009. Green plants that feed on fungi. Trends in Plant Science 14: 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selosse M-A, Faccio A, Scappaticci G, Bonfante P. 2004. Chlorophyllous and achlorophyllous specimens of Epipactis microphylla (Neottieae, Orchidaceae) are associated with ectomycorrhizal Septomycetes, including Truffles. Microbial Ecology 47: 416–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shefferson RP, Kull T, Tali K. 2008. Mycorrhizal interactions of orchids colonizing Estonian mine tailings hills. American Journal of Botany 95: 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöckel M, Meyer C, Gebauer G. 2011. The degree of mycoheterotrophic carbon gain in green, variegated and vegetative albino individuals of Cephalanthera damasonium is related to leaf chlorophyll concentrations. New Phytologist 189: 790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöckel M, Tĕšitelová T, Jersákova J, Bidartondo MI, Gebauer G. 2014. Carbon and nitrogen gain during the growth of orchid seedlings in nature. New Phytologist 202: 606–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AFS, Högbom L, Högberg M, Lyon AJE, Näsholm T, Högberg P. 1997. Natural 15N abundance in fruit bodies of ectomycorrhizal fungi from boreal forests. New Phytologist 136: 713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedersoo L, Pellet P, Kõljalg U, Selosse M-A. 2007. Parallel evolutionary paths to mycoheterotrophy in understorey Ericaceae and Orchidaceae: ecological evidence for mixotrophy in Pyroleae. Oecologia 151: 206–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tĕšitelová T, Tĕšitel J, Jersáková J, Ríhová G, Selosse M-A. 2012. Symbiotic germination capability of four Epipactis species (Orchidaceae) is broader than expected from adult ecology. American Journal of Botany 99: 1020–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Plant List. 2013. Version 1.1 http://www.theplantlist.org/ (accessed 15 June 2016).

- Trudell SA, Rygiewicz PT, Edmonds RL. 2003. Nitrogen and carbon stable isotope abundances support myco-heterotrophic nature and host-specificity of certain chlorophyllous plants. New Phytologist 160: 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderZanden MJ, Rasmussen JB. 2001. Variation in δ15N and δ13C trophic fractionation: implications for aquatic food web studies. Limnology and Oceanography 46: 2061–2066. [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics In: Innis M, Gelfand D, Sninsky J, White T, eds. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. New York: Academic Press, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer K, Hynson NA, Gebauer G, Allen EB, Allen MF, Read DJ.. 2007. Wide geographical and ecological distribution of nitrogen and carbon gains from fungi in pyroloids and monotropoids (Ericaceae) and in orchids. New Phytologist 175: 166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer K, Meyer C, Gebauer G. 2008. The ectomycorrhizal specialist orchid Corallorhiza trifida is a partial myco-heterotroph. New Phytologist 178: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.