Abstract

The study aimed to document the utility of the absolute number of natural killer cells as a biomarker in paediatric orbital myositis (OM). Extracted data from four children with OM included demographics, laboratory values, imaging and treatment response. Stored sera (−80°C) were tested for IgG4 levels in three cases and antibody to Coxsackie B in two cases. Their first symptom was at 14.4±1.2 years (mean±SD). At diagnosis three had creatine phosphokinase (CPK) of 97.3±44.2, aldolase of 8.5±2.8 (n=2), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 13±2.8 (n=2) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 21.3±2.9. IG4 level was 87.7±66 (normal=8–89 mg/dL); two sera (patients 1and4) were positive (>1:8 dilution) for anti-Coxsackievirus antigen B5. The CD3-CD16+CD56+ natural killer absolute count was 96.7±28.7 (lower limit of normal=138), increasing to 163±57.2 with disease resolution in three patients. The fourth patient was followed elsewhere. CT showed involvement of bilateral superior oblique, lateral rectus or the left medial rectus muscles. Treatment included intravenous methylprednisolone, methotrexate (n=2) and other immunosuppressants. Paediatric OM disease activity was associated with initially low absolute CD3-CD16+CD56+ natural killer cell counts, which normalised with improvement. We speculate (1) infection, such as Coxsackie B virus, may be associated with paediatric OM; and (2) the absolute count of circulating CD3-CD16+CD56+ natural killer lymphocytes may serve as a biomarker to guide medical therapy.

Keywords: pediatric orbital myositis, NK cells, biomarker, coxsackie B

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Orbital myositis is a rare type of idiopathic orbital inflammation in children.

In orbital myositis, serum levels of muscle enzymes are often normal and there are no known biomarkers of disease activity.

Treatment of orbital myositis typically includes corticosteroids and sometimes a steroid sparing agent such as methotrexate.

What does this study add?

In our study we found that absolute number of circulating CD3-CD16+CD56+ natural killer cells paralleled disease activity in children with orbital myositis.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Our study provides preliminary evidence that the absolute level of CD3-CD16+CD56+ natural killer cells may serve as a disease biomarker and a guide for immunosuppressive therapy in children with orbital myositis.

Introduction

Orbital myositis (OM), diffuse or focal inflammatory disease of the extraocular muscles, is rare in children, more typically presenting in the third decade with a female predominance.1–3 OM falls into the category of ‘idiopathic orbital inflammation’, formerly orbital pseudotumour,1 and is one of the juvenile inflammatory myopathies.4 OM can be idiopathic, but has been reported in systemic diseases, including sarcoidosis, Graves’ disease, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis and IgG4-related disease, and may occur following infection.5 6 The clinical presentation of OM may include orbital or periorbital pain, impaired ocular movement, diplopia and eyelid swelling.7 While an acute unilateral presentation is typical, bilateral and recurrent involvement has been described.7 8 Paediatric OM differs from adult OM in that bilateral involvement, uveitis and papilloedema are more common in children.7 8 Children may present with systemic symptoms including fever, malaise and anorexia.9 Elevated IgM and IgG Coxsackie antibodies at the onset of OM have been reported.10 Paediatric orbital inflammatory disorders account for 6%–17% of total reported orbital inflammatory disorders,5 of which 8% is OM.3 8–16 Serum levels of muscle enzymes are often normal; there are no known biomarkers of disease activity. However, we had previously observed that the absolute number of natural killer (NK) cells (CD3-CD16+CD56+) was an indicator of immune activity in 55% of children with juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM).17 The goal of this pilot study was to assess the absolute count of circulating NK cells as a potential guide for immunosuppressive therapy in paediatric OM.

Methods

After obtaining institutional review board (IRB) approval (IRB# 2014–15728), a retrospective review was performed of patients in the Cure JM Center database at the Ann & Robert H Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. Of 511 paediatric inflammatory myopathies, 4 had OM (0.78%). Data collected included age, gender, sex, diagnosis, laboratory values, imaging studies, pathology and treatment response. Duration of untreated disease (DUD) was defined as time (months) from onset of first symptoms to date of the first medication. The absolute levels of CD3-CD16+CD56+ NK cells via flow cytometry were determined using standard methods in the Diagnostic Immunology Laboratory. Residual sera (stored at −80°C) were tested for IgG4 levels and antibody to Coxsackievirus B (two patients).

Results

Subjects

All were Caucasian; two were female. The first symptom onset was at 14.4±1.2 (mean±SD) years; the mean DUD was 0.28±0.26 months at first visit. One child, patient 3, presented after disease resolution (table 1).

Table 1.

Cases of paediatric orbital myositis from 2006 to 2012

| Case | Age at presentation (years) | Gender | Muscle involvement | Treatment modalities | Other systemic diagnosis |

| 1 | 15.02 | M | Left superior oblique | Prednisone, methotrexate | N |

| 2 | 15.13 | M | Right superior oblique, left superior medial rectus and bilateral lateral rectus muscles | Prednisone, methylprednisolone, adalimumab | Undifferentiated granulomatous disease of ocular muscles |

| 3 | 19.67 | F | Left medial rectus | Methylprednisolone, prednisone | N |

| 4 | 13.93 | F | Right lateral rectus | Prednisone, methylprednisolone, methotrexate | N |

Laboratory data

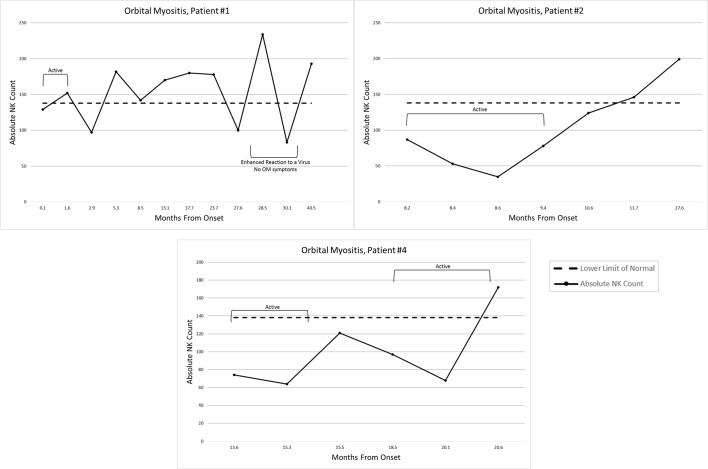

At diagnosis/first visit of the active OM, the following were the laboratory values (n=3 except where noted, mean±SD): CPK: 97.3±44.2 (26–268); aldolase: 8.5±2.8 (>8.5) (n=2); ALT: 13±2.8 (n=2); AST: 21.3±2.9; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): 176±52.4; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)=6±4; neopterin: 6.3±0.14 (<10 is abnormal) (n=2); and von Willebrand factor antigen: 133±14.1 (n=2). IgG4 levels were 125 mg/dL for patient 1, 11 mg/dL for patient 2 and 127 for patient 3 (mean IgG4 87.7±66, with normal range=8–89 mg/dL). Myositis-specific antibodies were negative (Oklahoma Research Institute). Patients 1 and 4 had elevated Coxsackievirus B5 antibody titres (both titres 1:16, with negative being <1:8); the remaining two patients’ sera were not tested (quanty not suffficient(sera); QNS). The absolute number of circulating CD3-CD16+CD56+ NK cells was 96.7±28.7 at diagnosis/first visit (lower limit of normal=138), increasing to the normal range of 163±57.2 with active disease resolution (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Absolute CD3-CD56+/16+NK cell counts over time in children with orbital myositis. NK, natural killer.

Muscle involvement

CT studies documented involvement of left and right superior oblique, left and right lateral rectus, and left medial rectus. One child had multiple orbital muscle abnormalities (table 1).

Clinical course

Patient 1

In March 2007, a 15-year-old human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27+ boy was presented with 3 days of left eye swelling and pain, redness, diplopia and ptosis; trauma or injury was denied. He had been treated for chalazion with tobramycin/dexamethasone drops and cefuroxime for possible preseptal cellulitis with worsening symptoms. Family history was positive for ankylosing spondylitis (father). He had mild erythema of the left eyelid with swelling, but no tenderness or drainage. CT of the orbits showed OM of the left superior oblique muscle and no periorbital or intraorbital mass. His dramatic response to oral prednisone (60 mg daily) was followed by a recurrence of OM in April 2007, 1 day after completing his prednisone taper. After reinstitution of oral prednisone with methotrexate added as a steroid sparing agent, he was weaned off all medications and remained asymptomatic.

Patient 2

A 15-year-old boy with a history of right OM 8 months prior was presented in October 2006 with bilateral eye pain (right first, then left), horizontal diplopia with left gaze and headache for 1 month. Physical exam showed left eye proptosis with reactive pupils, intact extraocular muscles and conjunctival injection. CT orbit showed new abnormal enlargement of right superior oblique muscle and left superior medial and lateral rectus muscles. The patient improved with intravenous methylprednisolone (1000 mg daily for 3 days), but eye pain and left proptosis returned and he required additional weekly intravenous steroids and methotrexate. Concurrently, he had a cyst removed from the pinna of his left ear, followed by left Bell’s palsy. Eventual biopsy of ocular muscle was reported as granulomatous change, leading to an evaluation for inflammatory bowel disease, which was negative. This was responsive to a tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor, after which he had slightly depressed circulating levels of IgG=498 (613–1295) and IgA=37.2 (69–309), but normal IgM=61.7 (53–334) and IgE=6.13 (<192).

Patient 3

In March 2010, a 19-year-old girl came to rheumatology with left knee pain and a history of OM. On exam, she had decreased internal rotation of the left knee. X-ray identified a lytic lesion with sclerotic margin within the posterolateral cortex of the left distal femoral metaphysis. The absolute NK count was normal at 264. The patient had a history of OM. In March 2006, age 15, she had sudden onset of left eye pain, photophobia, horizontal diplopia and redness. Her left eye displayed injected medial sclera, pain with lateral/upward/medial gaze, photophobia and mild proptosis. Diagnosed with cellulitis, she did not improve with antibiotics. Repeat CT documented a left medial rectus rim-enhancing hypodense mass (figure 2). Ophthalmology stopped antibiotics and intravenous methylprednisolone and oral prednisone started with sustained resolution after 1 month of therapy.

Figure 2.

Patient 3. Axial contrast-enhanced orbital CT demonstrates marked swelling of the left medial rectus muscle with a more focal peripherally enhancing mass in the mid-muscle belly (white arrow). There is mild induration of the left retrobulbar fat with slight proptosis.

Patient 4

A 14-year-old girl with a history of OM was seen in the rheumatology clinic in April 2012. In March 2011, she had a sudden-onset right ocular headache. A CT scan of the orbits showed mild right periorbital soft tissue swelling and bilateral sphenoid sinus disease for which she received amoxicillin/clavulanate; the enlargement of the right lateral rectus muscle improved rapidly with oral prednisone (50 mg daily) with a taper off of steroids 1 month later. In January 2012, she developed recurrent similar symptoms and required another course of prednisone. She had recurrence of disease again in March 2012 and April 2012 and required initiation of methotrexate. At last follow-up (2012), her disease was in remission.

Discussion

The presentation of OM can mimic an infectious process such as orbital cellulitis, which can delay proper treatment. Patients with orbital cellulitis usually have high fever and a prompt response to antibiotic therapy. However, they can also have eyelid erythema, ptosis and impaired motor function of one or more extraocular muscles, similar to OM.3 The differential diagnosis of paediatric OM also includes rhabdomyosarcoma, thyroid eye disease, leukaemia, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, tuberculosis, histiocytosis, ruptured dermoid cyst, arteriovenous malformations and paranasal sinus mucocele.7–15

OM has traditionally been a diagnosis of exclusion based on clinical and radiographic data.7 8 The utility of biopsy in children with OM disease is unclear.16 This may be due, in part, to an early case series of children with OM in which permanent functional impairment seemed more frequent in children who had undergone surgical exploration.15 When histopathology is obtained, it is usually non-specific, with chronic, polymorphic inflammatory infiltrate, and occasionally sclerosing or granulomatous variants.7 Biopsy is probably best reserved for cases that are not responding as expected to therapy, or when a neoplastic process is under consideration. A prompt response to high-dose corticosteroids is typical, but steroid tapering must be done with caution, for brisk tapering frequently results in disease recurrence. Successful treatment of OM with adalimumab has also been reported.14

Finally, commonly used laboratory tests for inflammatory muscle disease do not appear to be reliable indicators of disease activity in children with OM. However, the absolute number of circulating NK cells, an immune biomarker associated with disease activity in some children with JDM17 18 but not others,19 also paralleled the clinical course of the children with OM. NK cells have a wide range of functions as a mainstay of innate immunity, for example, against viral infections and in tumour surveillance. The absolute NK cell (CD3-CD16+CD56+) number and function is moderately reduced in systemic lupus erythematosus, in children with untreated Graves’ disease or other paediatric autoimmune diseases.20 The presence of IgG antibodies to Coxsackievirus B5 in the two patients with OM tested is intriguing, for elevated neutralising antibodies to Coxsackie B2 and B4 were identified in sera from children with JDM.21 In this study, NK numbers were consistently depressed during active disease and returned to normal range as the OM responded to therapy. This is preliminary evidence that the absolute level of NK cells may serve as a guide for immunosuppressive therapy in children with OM. A larger study of the role of NK cells in the pathophysiology of OM and their utility as biomarkers of disease activity in paediatric OM is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The submission of this manuscript was facilitated by the expert assistance of Brittany Hudanick, our senior administrator.

Footnotes

Contributors: MRB: Performed the chart review, abstracted the data, performed a PubMed search, compiled the references and wrote the manuscript which she has now reviewed for resubmission. GAM: Data manager, retrieved and evaluated the individual data, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and has approved the revision. She prepared the sequential graph of available natural killer cells for the revision. MCA: Project coordinator, prepared the IRB for this study which allowed its execution, arranged for the testing of the residual sera for the IgG4 and Coxsackievirus antibodies. She reviewed the manuscript and approves of the final draft. BR: Ophthalmologist who identified the children with OM and referred them to LP for further investigation. He has reviewed the manuscript and approves of the final draft. MER: Radiologist who selected the appropriate documentation for the OM patient presented. She has reviewed the final draft of the manuscript and has agreed with the changes made. LP: Pediatric rheumatology with experience in NK cell reactivity in children with JDM. She has seen each of the patients, collected and identified the data to be assessed, reviewed MRB manuscript and has approved the last edition of the manuscript and its figures, which are included.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: IRB of the Ann & Robert H Lurie Children's Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Please direct enquiries regarding additional data to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Fraser CL, Skalicky SE, Gurbaxani A, et al. Ocular myositis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2013;13:315–21. 10.1007/s11882-012-0319-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Costa RM, Dumitrascu OM, Gordon LK. Orbital myositis: diagnosis and management. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2009;9:316–23. 10.1007/s11882-009-0045-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yan J, Qiu H, Wu Z, et al. Idiopathic orbital inflammatory pseudotumor in Chinese children. Orbit 2006;25:1–4. 10.1080/01676830500505608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rider LG, Katz JD, Jones OY. Developments in the classification and treatment of the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2013;39:877–904. 10.1016/j.rdc.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Belanger C, Zhang KS, Reddy AK, et al. Inflammatory disorders of the orbit in childhood: a case series. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;150:460–3. 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wallace ZS, Khosroshahi A, Jakobiec FA, et al. IgG4-related systemic disease as a cause of "idiopathic" orbital inflammation, including orbital myositis, and trigeminal nerve involvement. Surv Ophthalmol 2012;57:26–33. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Avni-Zauberman N, Tripathy D, Rosen N, et al. Relapsing migratory idiopathic orbital inflammation: six new cases and review of the literature. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:276–80. 10.1136/bjo.2010.191866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abd-Rashid R, Hussein A, Yunus R, et al. Recurrent bilateral orbital myositis: case report and review of the literature. Ann Trop Paediatr 2011;31:173–80. 10.1179/1465328111Y.0000000004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang TS, Sunkara SM, Cooley AS. Adolescent with right orbital swelling and proptosis. Idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:677–8. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gil P, Gil J, Paiva C, et al. Medical and Surgical Treatment in Pediatric Orbital Myositis Associated with Coxsackie Virus. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med 2015;:1–4 Art ID 917275 10.1155/2015/917275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spindle J, Narang S, Purewal B, et al. Atypical idiopathic orbital inflammation in a young girl. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;29:e86–e88. 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318275b649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hankey GJ, Silbert PL, Edis RH, et al. Orbital myositis: a study of six cases. Aust N Z J Med 1987;17:585–91. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1987.tb01264.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spindle J, Tang SX, Davies B, et al. Pediatric Idiopathic Orbital Inflammation: Clinical Features of 30 Cases. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2016;32:270–4. 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adams AB, Kazim M, Lehman TJ. Treatment of orbital myositis with adalimumab (Humira). J Rheumatol 2005;32:1374–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mottow LS, Jakobiec FA. Idiopathic inflammatory orbital pseudotumor in childhood. I. Clinical characteristics. Arch Ophthalmol 1978;96:1410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mombaerts I, Rose GE, Garrity JA. Orbital inflammation: Biopsy first. Surv Ophthalmol 2016;61:664–9. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pachman LM, Geraci N, Morgan GA, et al. Absolute number of circulating CD3-CD56+/CD16+ natural killer (NK) cells, a potential biomarker of disease activity in Juvenile Dermatomyositis (JDM). Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:S225. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller ML, Lantner R, Pachman LM. Natural and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in children with systemic lupus erythematosus and juvenile dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 1983;10:640–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ernste FC, Crowson CS, de Padilla CL, et al. Longitudinal peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets correlate with decreased disease activity in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1200–11. 10.3899/jrheum.121031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Popko K, Górska E. The role of natural killer cells in pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Cent Eur J Immunol 2015;40:470–6. 10.5114/ceji.2015.56971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Christensen ML, Pachman LM, Schneiderman R, et al. Prevalence of Coxsackie B virus antibodies in patients with juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1365–70. 10.1002/art.1780291109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]