Abstract

Background:

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) affects people in childhood (childhood onset) or in adulthood (adult onset). Observational studies that have previously compared childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE were often restricted to 1 ethnic group, or to a particular area, with a small sample size of patients. We aimed to systematically compare childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE through a meta-analysis.

Methods:

Electronic databases were searched for relevant publications comparing childhood-onset with adult-onset SLE. Adverse clinical features were considered as the endpoints. The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the methodological quality of the studies and RevMan software (version 5.3) was used to carry out this analysis whereby risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were used as the statistical parameters.

Results:

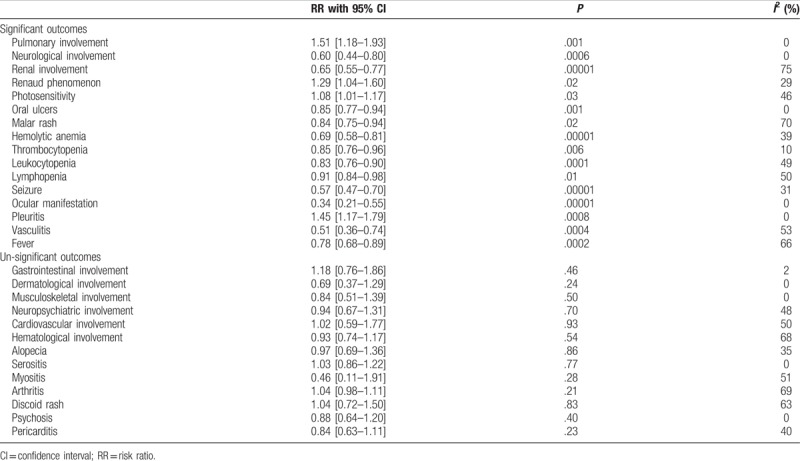

A total number of 10,261 participants (1560 participants with childhood-onset SLE and 8701 participants with adult-onset SLE) were enrolled. Results of this analysis showed that compared with childhood-onset SLE, pulmonary involvement was significantly higher with adult-onset SLE (RR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.18–1.93; P = .001), whereas renal involvement was significantly higher with childhood-onset SLE (RR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.55–0.77; P = .00001). Raynaud phenomenon and photosensitivity were significantly higher in adult-onset SLE (RR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.04–1.60; P = .02) and (RR: 1.08, 95% CI: 1.01–1.17; P = .03), respectively. Malar rash significantly favored adult-onset SLE (RR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.75–0.94; P = .002). Childhood-onset SLE was associated with significantly higher hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytopenia, and lymphopenia. Seizure and ocular manifestations were significantly higher with childhood-onset SLE (RR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.47–0.70; P = .00001) and (RR: 0.34, 95% CI: 0.21–0.55; P = .00001), respectively, whereas pleuritis was significantly higher with adult-onset SLE (RR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.17–1.79; P = .0008). Vasculitis and fever were significantly higher with childhood-onset SLE (RR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.36–0.74; P = .0004) and (RR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.68–0.89; P = .0002) respectively.

Conclusion:

Significant differences were observed between childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE, showing the former to be more aggressive.

Keywords: adult-onset, childhood-onset, clinical features, hematological manifestations, renal diseases, seizures, systemic lupus erythematosus

1. Introduction

Autoimmune diseases have not well been studied through randomized controlled trials. However, even if small prospective, retrospective, and case–control studies were commonly used to study those diseases, they have gradually been able to show the impact of autoimmune diseases on the population.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is one among the common autoimmune disorders affecting a large number of female patients.[1] Even if it is often misdiagnosed or remains undiagnosed by physicians, several important classifications have been proposed according to recent guidelines.[2] The diagnosis of SLE is based on 17 important criteria, whereby a diagnosis of SLE could be made based on 4 of the criteria, including at least 1 of the 11 clinical criteria and 1 of the 6 immunological criteria or by a biopsy-proven nephritis compatible with SLE in the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) or anti-double stranded DNA antibodies (ds-DNA).[3]

SLE affects people in childhood (childhood-onset) or in adulthood (adult-onset). However, observational studies that have previously compared childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE were often restricted to 1 ethnic group,[4] or to a particular area,[5] with a small sample size of patients.[6] Childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE were not compared on an International or most probably on a worldwide basis (including patients from different parts of the world) to know whether the differences could be applied throughout any population. Therefore, we aimed to systematically compare childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE using a large number of patients that were extracted from studies based on different regions, with different ethnic groups, in order to obtain a generalized outcome.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources and searched strategies

Data sources included

-

(1)

MEDLINE/PubMed database of medical research articles;

-

(2)

EMBASE database;

-

(3)

Cochrane library;

-

(4)

www.ClinicalTrials.gov;

-

(5)

Reference lists of suitable publications;

-

(6)

Google scholar;

-

(7)

Official websites of several journals of rheumatology.

2.2. Searched strategies

The following terms were used in the search process:

-

(1)

“systemic lupus erythematosus,” “childhood,” and “adult”;

-

(2)

“systemic lupus erythematosus” and “childhood”;

-

(3)

“systemic lupus erythematosus” and “adult-onset”;

-

(4)

“childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus”;

-

(5)

“adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus”;

-

(6)

“childhood onset systemic lupus erythematosus” and “adult onset systemic lupus erythematosus.”

The abbreviation “SLE” was also used in this search process to replace its full-form.

Only English publications were searched.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that satisfied the inclusion criteria were

-

(1)

Studies that compared childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE;

-

(2)

Studies that reported clinical outcomes which were observed between childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE;

-

(3)

Studies that reported their data in the form of dichotomous data (number of events), which could be used in this analysis.

Studies were excluded based on the fact that

-

(1)

They did not compare childhood-onset with adult-onset SLE;

-

(2)

They did not report adverse clinical outcomes as their endpoints;

-

(3)

They reported data in a form that could not be used in this meta-analysis;

-

(4)

They were duplicate studies or replicated themselves through different searched databases.

2.4. Types of participants, outcomes, and definitions

This analysis involved participants with childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE, respectively. Onset of SLE before the age of 17 years was classified as childhood-onset, whereas SLE onset after the age of 17 years, but before the age of 50 years, was considered as adult-onset SLE in this analysis. Late-onset participants who acquired SLE after the age of 50 years were not included.

Endpoints that were assessed were first of all based on systemic involvement such as

-

(1)

Pulmonary involvement;

-

(2)

Gastrointestinal involvement;

-

(3)

Dermatological involvement;

-

(4)

Neurological involvement;

-

(5)

Musculoskeletal involvement;

-

(6)

Neuropsychiatric involvement;

-

(7)

Renal involvement;

-

(8)

Cardiovascular involvement;

-

(9)

Hematological involvement;

-

(10)

In addition, detailed clinical manifestations were also assessed.

2.5. Rheumatological and connective tissue manifestations

-

(1)

Raynaud phenomenon

-

(2)

Photosensitivity

-

(3)

Alopecia

-

(4)

Serositis

-

(5)

Myositis

-

(6)

Oral ulcers

-

(7)

Arthritis

-

(8)

Malar rash

-

(9)

Discoid rash

2.6. Hematological manifestations

-

(1)

Hemolytic anemia

-

(2)

Thrombocytopenia

-

(3)

Leukocytopenia

-

(4)

Lymphopenia

2.7. Central nervous system manifestations

-

(1)

Seizure

-

(2)

Psychosis

2.8. Other clinical manifestations

-

(1)

Pericarditis

-

(2)

Ocular manifestations

-

(3)

Pleuritis

-

(4)

Vasculitis

-

(5)

Fever.

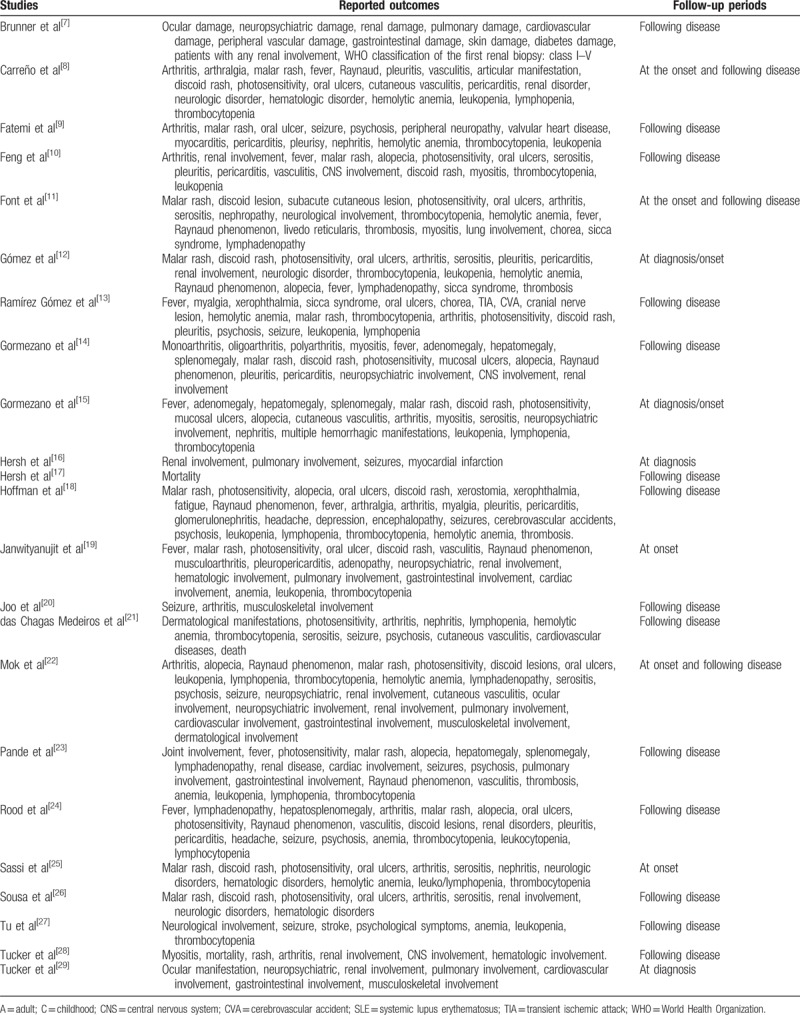

The clinical features that were reported in each study have been summarized in Table 1.[7–29]

Table 1.

Types of participants, outcomes, and follow-up.

2.9. Data extraction and review

Data were extracted by 2 independent reviewers (PKB and AK). All the relevant information to be used in this analysis was collected. The clinical features that were reported, the age of disease onset, the types of participants, the total number of participants that were extracted from each study, the total number of events that were reported, were all recorded. As baseline features of the participants were seldom reported, we could not include these data in our analysis.

During this data extraction and data collection process, if ever any disagreement occurred, it was discussed between the 2 reviewers. However, if a final decision could not be made, the third reviewer (FH) was called to discuss and solve the issue.

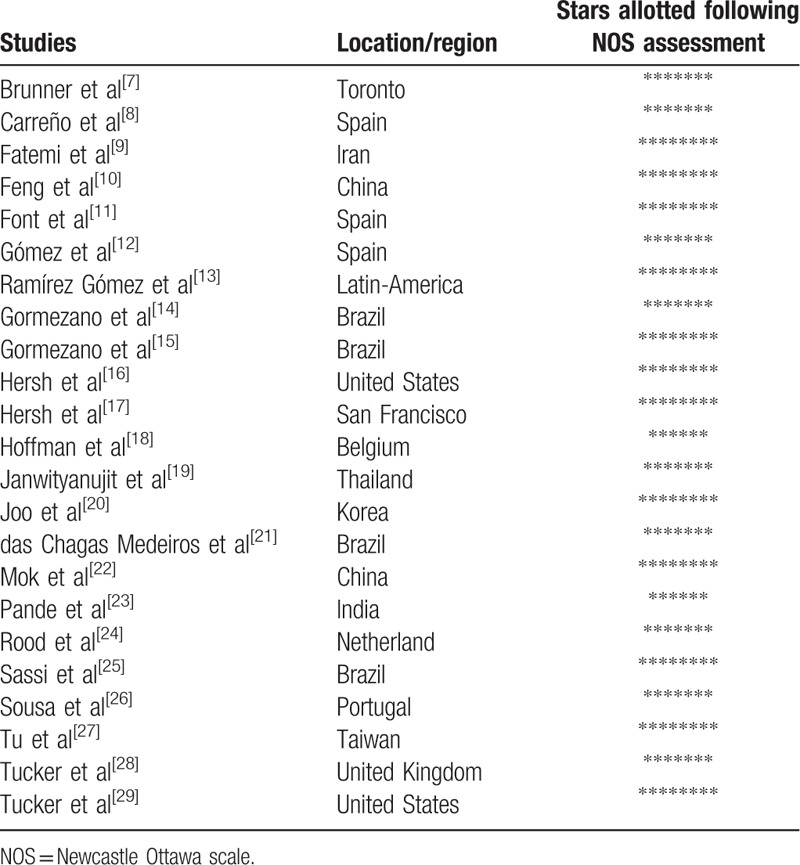

As all the studies which were included in this analysis were observational studies, the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the methodological quality of the studies. NOS has been refined on the basis of expertise and experience whereby it was used in several projects.[30]

NOS assessment involved a minimum number of zero star to a maximum number of 9 stars depending on the quality of the study being assessed. The region where these studies were conducted and the number of stars allotted following the NOS assessment have been listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study assessment using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

2.10. Statistical analysis

The latest version of the RevMan software (version 5.3) was used to carry out this analysis whereby risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were used as the statistical parameters. However, a short coming that often affects meta-analyses is the presence of inconsistency across studies during subgroup analysis.[31] Hence, the Q statistic test and the I2 statistic test were used to assess heterogeneity.

Statistically significant value was less or equal to 0.05.

Significance of I2: A low percentage of I2 denoted a low level of heterogeneity.

Fixed effects model: used if I2 was less than 50%.

Random effects model: used if I2 was greater than 50%.

Ethical approval was not necessary for this analysis.

Publication bias was visually assessed by observing funnel plots.

3. Results

3.1. Searched outcomes

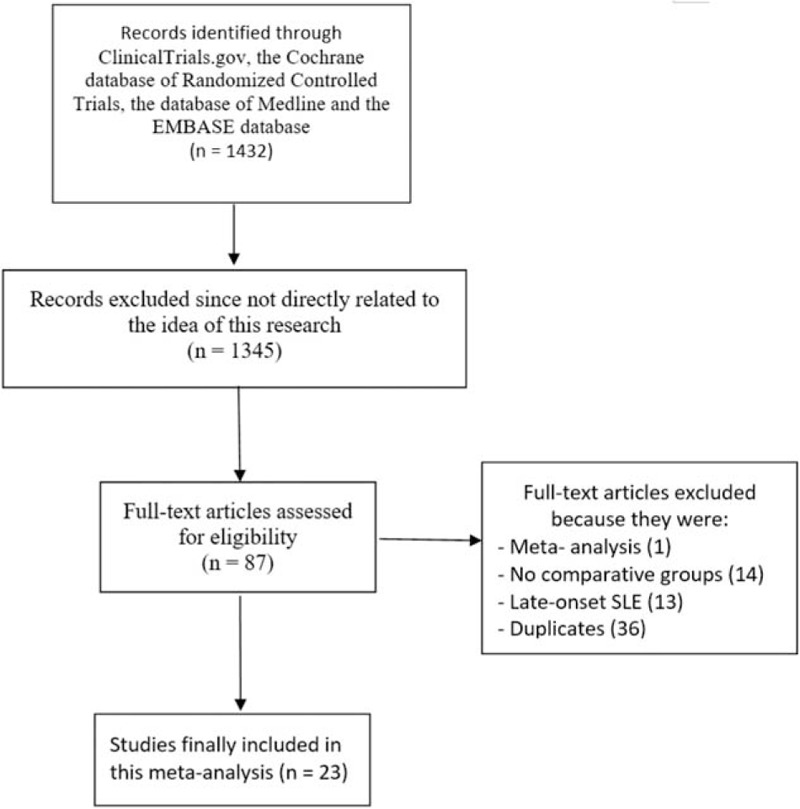

The PRISMA study guideline was used.[32] A total number of 1432 publications were obtained. A first elimination was directly carried out based upon assessment of the titles and abstracts whereby 1345 articles were rejected. Further eliminations were based on

-

(1)

the study was a meta-analysis (1);

-

(2)

the studies did not include any comparative group (14);

-

(3)

the studies involved late-onset SLE participants (13);

-

(4)

the studies were duplicates (36).

Finally, only 23 articles[7–29] were selected for this analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram representing the study selection.

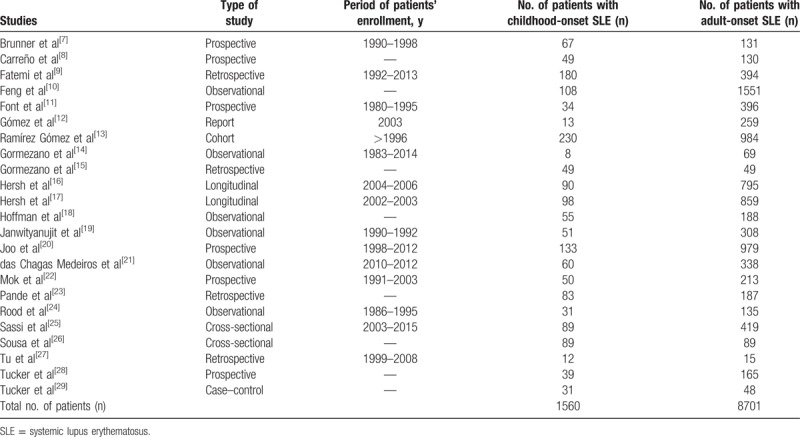

3.2. Main features of the studies which were included

The types of study that were reported, the number of participants who were classified in the childhood-onset and the adult-onset SLE groups, respectively, and the time period of patients’ enrollment have all been listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Main features of the studies which were included.

A total number of 10,261 participants (1560 participants with childhood-onset SLE and 8701 participants with adult-onset SLE) who were enrolled from the year 1980 to 2013 were included in this analysis.

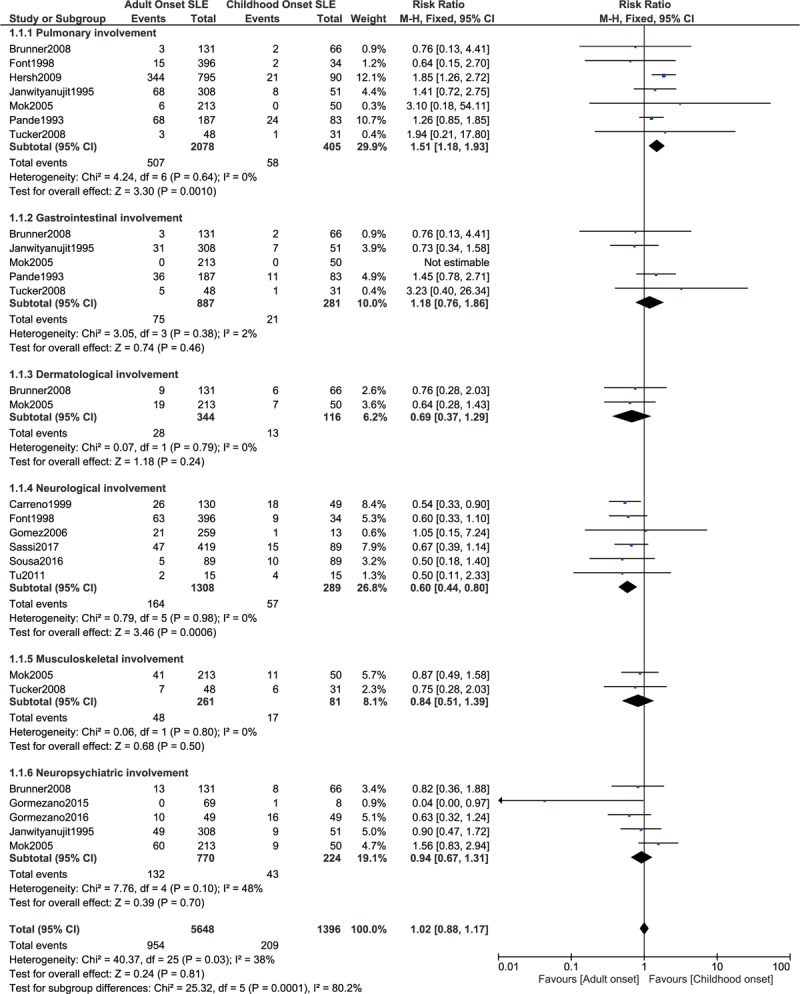

3.3. System involvement

Results of this current analysis showed that compared with childhood-onset SLE, pulmonary involvement was significantly higher with adult-onset SLE with RR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.18 to 1.93; P = .001, I2 = 0% (Fig. 2). Gastrointestinal involvement, dermatological involvement, musculoskeletal involvement, and neuropsychiatric involvement as a whole were not significantly different between childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE with RR: 1.18, 95% CI: 0.76 to 1.86; P = .46, I2 = 2%, RR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.37 to 1.29; P = .24, I2 = 0%, RR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.51 to 1.39; P = .50, I2 = 0% and RR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.67 to 1.31; P = .70, I2 = 48%, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2. However, neurological involvement was significantly higher in childhood-onset SLE with RR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.44 to 0.80; P = .0006, I2 = 0% (Fig. 2). A fixed effects model was used to assess these outcomes.

Figure 2.

System involvement between childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE (part 1).

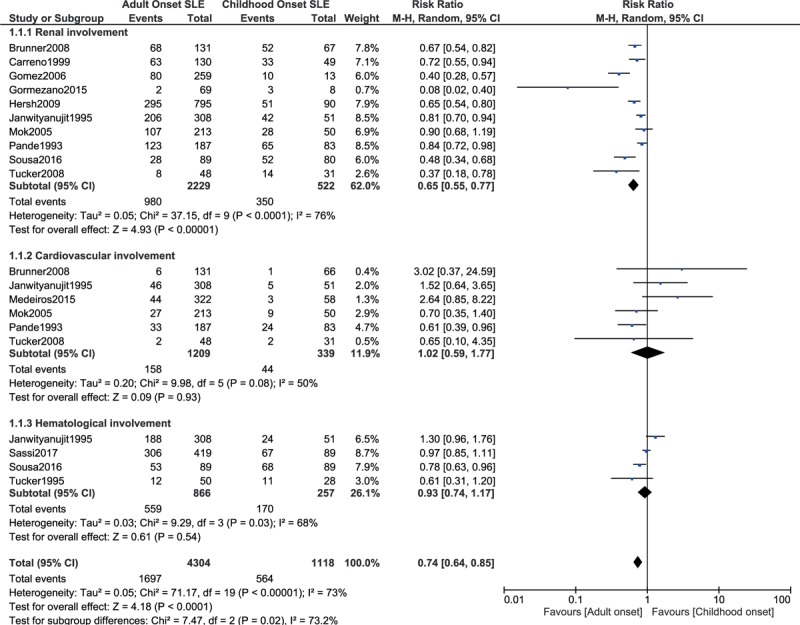

A random effects model was used to assess several other outcomes. This analysis showed renal involvement to be significantly higher with childhood-onset SLE with RR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.55 to 0.77; P = .00001, I2 = 76% as shown in Fig. 3. However, cardiovascular and hematological involvement as a whole were not significantly different with childhood-onset or adult-onset SLE with RR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.59–1.77; P = .93, I2 = 50% and RR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.17; P = .54, I2 = 68%, respectively (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

System involvement between childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE (part 2).

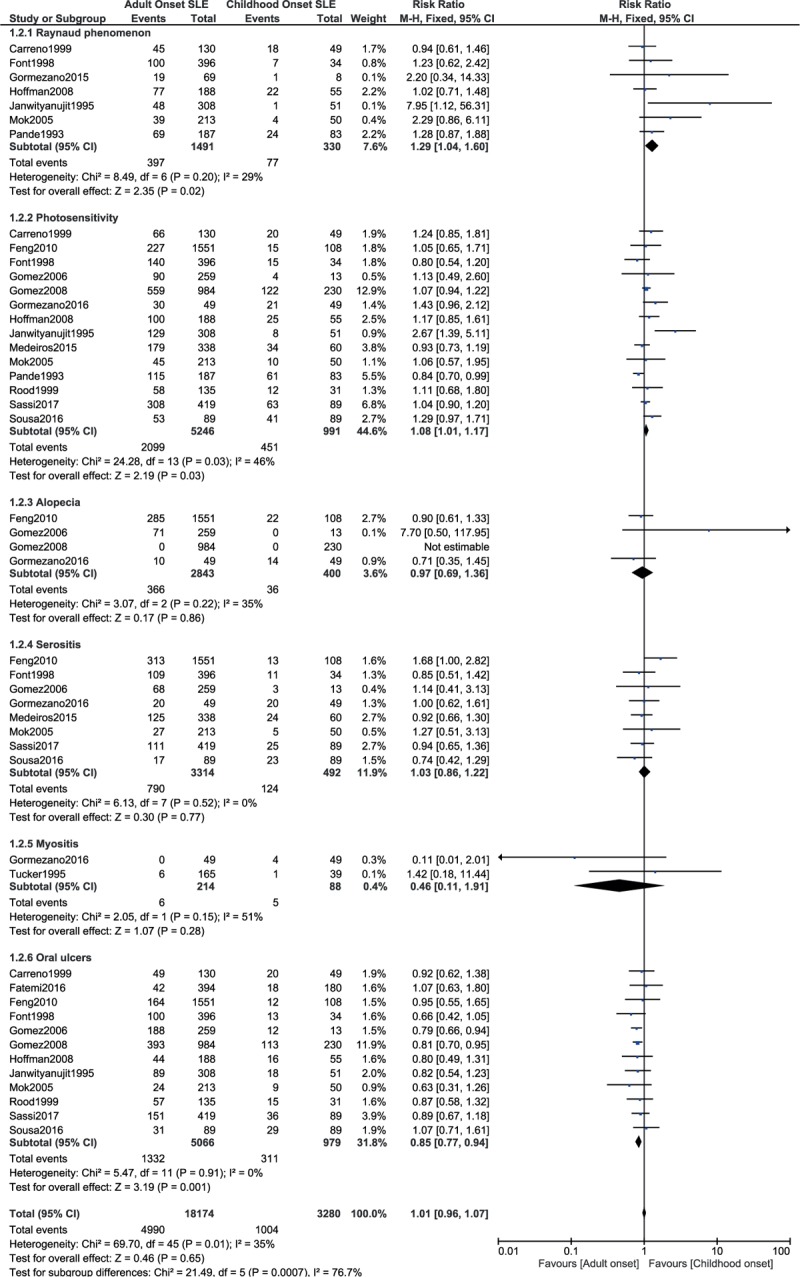

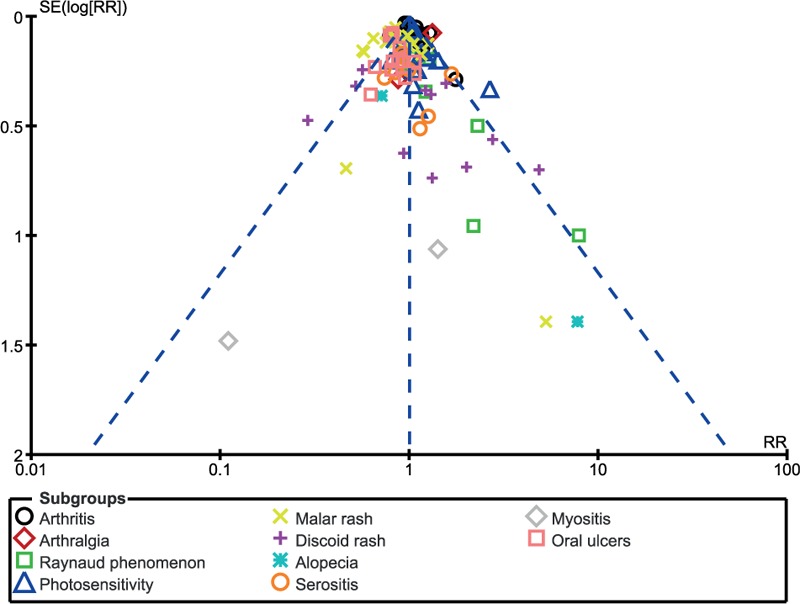

3.4. Rheumatological and connective tissue involvement

Raynaud phenomenon and photosensitivity were significantly higher in adult-onset SLE with RR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.60; P = .02, I2 = 29% and RR: 1.08, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.17; P = .03, I2 = 46%, respectively (Fig. 4). On the contrary, oral ulcers were significantly higher with childhood-onset SLE with RR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.77 to 0.94; P = .001, I2 = 0% (Fig. 4). However, alopecia, serositis, and myositis were not significantly different with RR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.69 to 1.36; P = .86, I2 = 35%, RR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.86 to 1.22; P = .77, I2 = 0%, and RR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.11 to 1.91; P = .28, I2 = 51%, respectively (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Rheumatological and connective tissue manifestations (part 1).

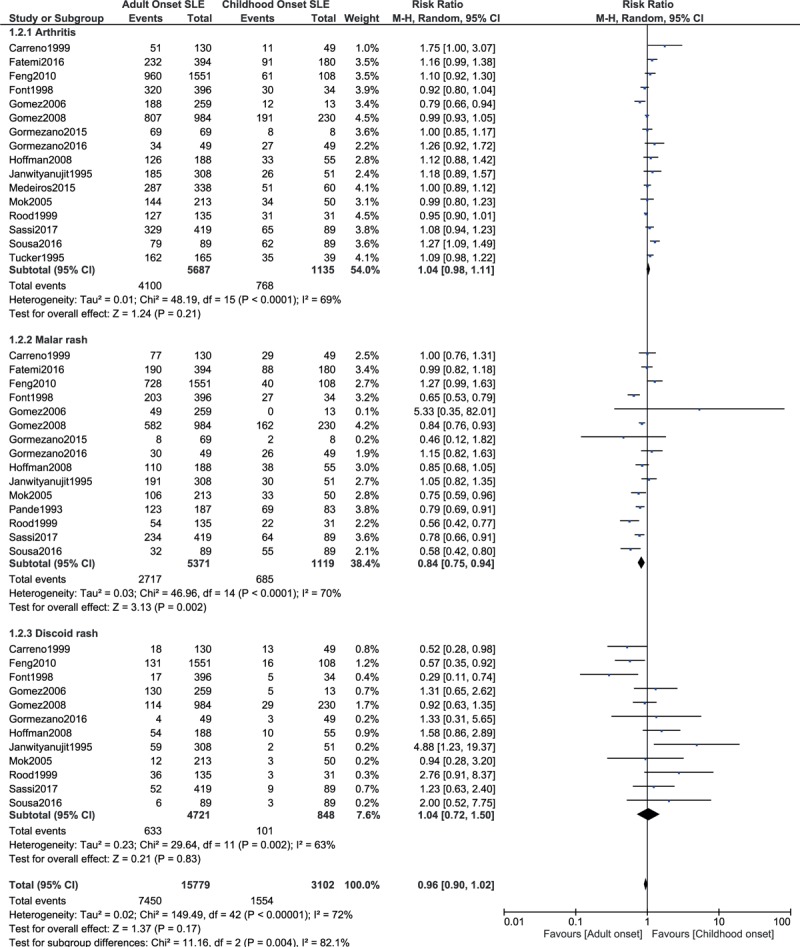

This current result also showed malar rash to significantly favored adult-onset SLE and affected patients with childhood-onset SLE to a higher extent with RR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.75 to 0.94; P = .002, I2 = 70% (Fig. 5). However, arthritis and discoid rash were similarly manifested between childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE with RR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.98 to 1.11; P = .21, I2 = 69% and RR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.72 to 1.50; P = .83, I2 = 63%, respectively (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Rheumatological and connective tissue manifestations (part 2).

3.5. Hematological manifestations

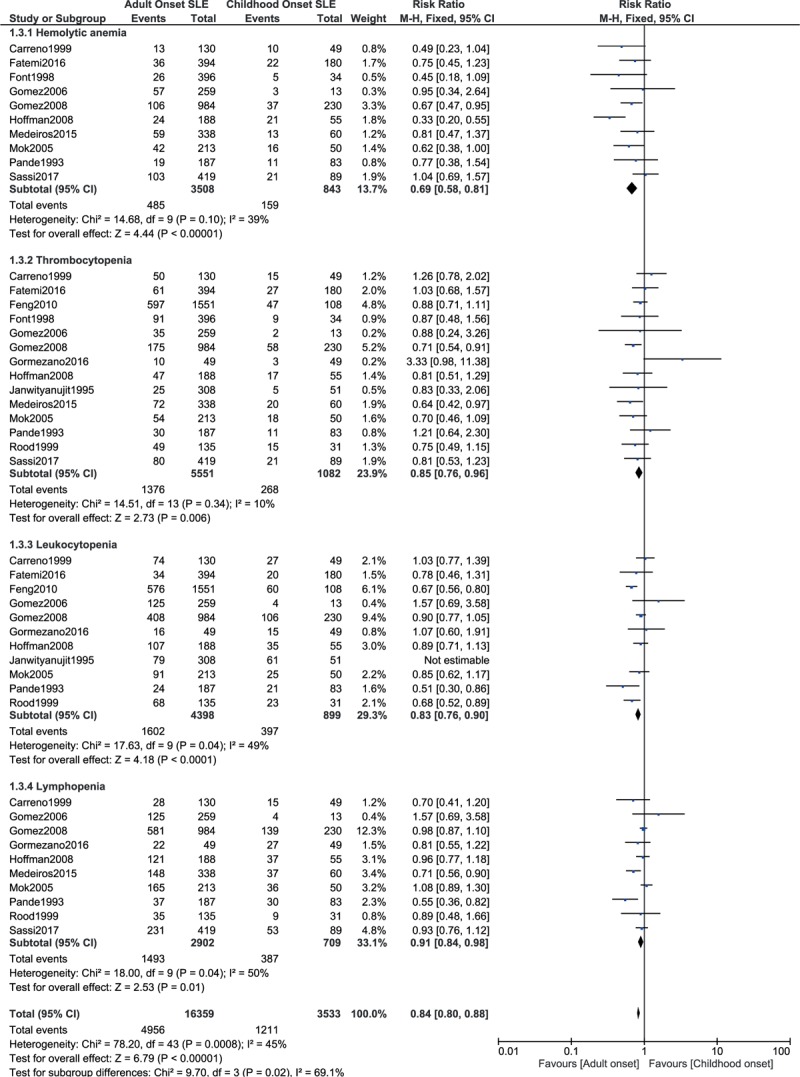

When hematological involvement was further subdivided, childhood-onset SLE was associated with significantly higher hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukocytopenia, and lymphopenia with RR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.58 to 0.81; P = .00001, I2 = 39%, RR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.76 to 0.96; P = .006, I2 = 10%, RR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.76 to 0.90; P = .0001, I2 = 49%, and RR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.84 to 0.98; P = .01, I2 = 50%, respectively (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Hematological manifestations.

3.6. Nervous system manifestations

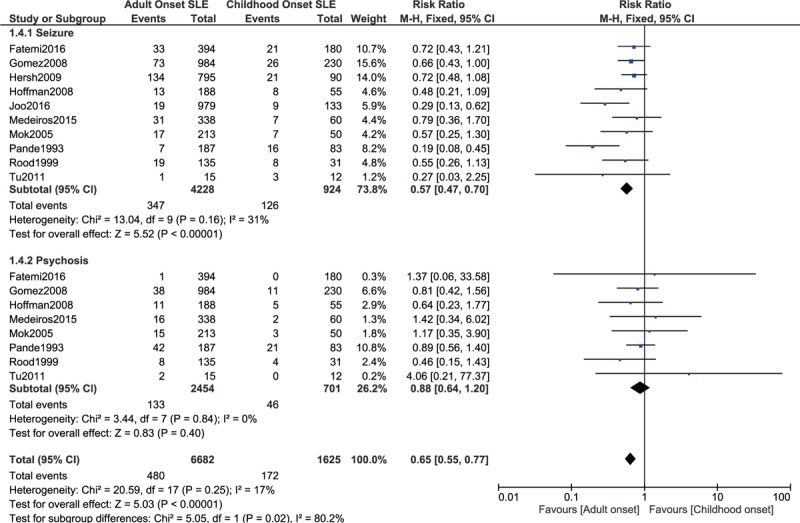

Seizure was significantly higher with childhood-onset SLE with RR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.47 to 0.70; P = .00001, I2 = 31%. However, no significant difference was observed with psychosis, with RR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.64 to 1.20; P = .40, I2 = 0% (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Nervous system manifestations.

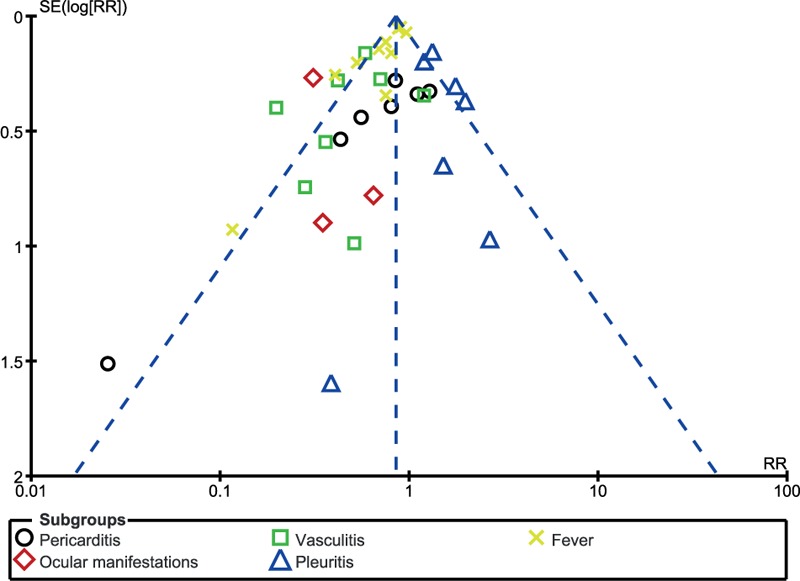

3.7. Other clinical manifestations

Ocular manifestation was significantly higher with childhood-onset SLE, with RR: 0.34, 95% CI: 0.21 to 0.55; P = .00001, I2 = 0%, whereas pleuritis was significantly higher with adult-onset SLE with RR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.17 to 1.79; P = .0008, I2 = 0%. However, pericarditis was similarly manifested with RR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.63 to 1.11; P = .23, I2 = 40%.

Vasculitis and fever were significantly higher with childhood-onset SLE, with RR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.36 to 0.74; P = .0004, I2 = 53% and RR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.68 to 0.89; P = .0002, I2 = 66%, respectively.

Significant and un-significant outcomes are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of this analysis.

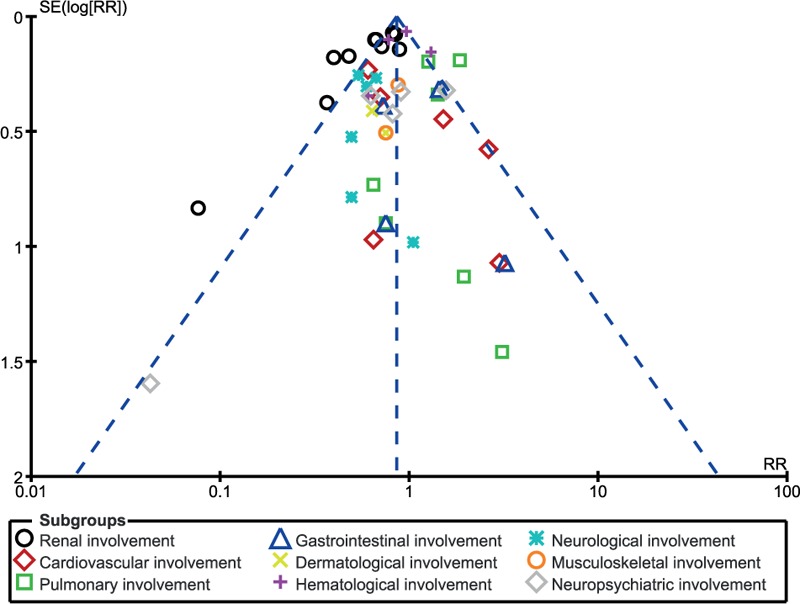

3.8. Publication bias

A visual assessment of the 3 funnel plots, which were obtained from RevMan, showed a low to moderate risk of publication bias across the studies that assessed the relevant clinical endpoints. The funnel plots have been represented in Figs. 8 to 10.

Figure 8.

Funnel plot showing publication bias.

Figure 10.

Funnel plot showing publication bias.

Figure 9.

Funnel plot showing publication bias.

4. Discussion

In this analysis, we aimed to compare the clinical features that were associated with childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE using a large number of participants, which was obtained from several corners around the world. The current results showed significantly more adverse features to be associated with childhood-onset SLE when compared with adult-onset SLE. Neurological and renal involvement were more significant with childhood-onset SLE. Even fever significantly favored adult-onset SLE compared with childhood-onset SLE. When hematological manifestation was further analyzed, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and lymphopenia were significantly higher with childhood-onset SLE. However, pulmonary involvement, Raynaud phenomenon, and photosensitivity were significantly higher with adult-onset SLE.

A recent meta-analysis comparing the differences in autoantibody profiles and disease activity and damage score associated with childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE showed increased anti-ds DNA and anticardiolipin antibodies to be significantly associated with childhood-onset SLE.[33] The authors also suggested more disease activity in this category of SLE patients than adult-onset SLE. This current analysis has further supported their conclusion proving that more adverse clinical manifestations were present with childhood-onset SLE. Another meta-analysis comparing cutaneous manifestations between early-onset versus late onset SLE showed the latter to be associated with less severe outcomes.[34] However, this current analysis did not involve patients with late-onset (elderly) SLE.

A review article based on the recent updates on the differences between childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE showed the latter to be 10 times more common than the former in United States. However, the authors mentioned that childhood-onset SLE was more severe.[35] Another review article based on the similarities and differences between childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE showed higher prevalence of renal involvement (nephritis) and central nervous system involvement in children than in adults, further supporting the results of this current analysis.[36] The authors also suggested that additional steroid use and more aggressive treatment strategy should be considered in childhood-onset SLE. Moreover, data from the 2002 to 2010 cycles of the Lupus Outcomes Study showed childhood-onset SLE to significantly increase the risk of not working in adulthood, despite of full control of the disease.[37]

This current analysis showed childhood-onset SLE to be more aggressive; therefore, specific therapy with better management should be reserved to this particular subgroup. A few studies showed hematuria to significantly increase the mortality rate in participants with childhood-onset SLE that might have been due to complications associated with the renal organ.[38] However, other studies have concluded that patients with childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE with renal involvement should both be carefully monitored to prevent unwanted outcomes.

This analysis satisfied all the criteria which are relevant for a good systematic review and meta-analysis. The methodological quality of the studies which were included were assessed. Robust results which match with the clinical literature were obtained. In addition, the current results have been generalized, and not limited to a specific ethnic group or region.

4.1. Novelty

This analysis is new because of several reasons:

-

(1)

It is the first meta-analysis comparing clinical manifestations that were observed between childhood-onset versus adult-onset SLE; in contrast, a previously published meta-analysis only compared the laboratory features.

-

(2)

This analysis includes a very large number of participants from different regions, thus, representing a generalized result that is not affected by a particular region or ethnic group.

-

(3)

This idea is important in clinical medicine; the word SLE has often been heard, but, childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE, and their influence on clinical features might show something new to the readers.

-

(4)

This analysis is very informative, showing a lot of data and results that are related to the differences between these 2 onset-periods of SLE, representing a new feature.

4.2. Limitations

This analysis also has several limitations:

-

(1)

In those patients to whom clinical features were not reported following the course of the disease, clinical features at onset of the disease were considered relevant.

-

(2)

All the data which were extracted were obtained from observational studies, which could be another limitation.

-

(3)

Moderate to less severe heterogeneity was reported in several of the subgroups assessing the clinical features.

5. Conclusion

Significant differences were observed between childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE. Childhood-onset SLE was associated with significantly higher adverse clinical features whereby neurological involvement, renal involvement, oral ulcers, malar rash, vasculitis, fever, ocular, and hematological manifestations were significantly higher, whereas pulmonary involvement, Raynaud phenomenon, and photosensitivity were significantly higher with adult-onset SLE. However, no significant difference was observed in gastrointestinal involvement, cardiovascular involvement, discoid rash, psychosis, alopecia, serositis, and arthritis.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence intervals, RR = risk ratios, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

Authorship: PKB, AK, and FH were responsible for the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the initial manuscript, and revising it critically for important intellectual content. PKB wrote this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding/support: This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81560046), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (No. 2016GXNSFAA380002), Scientific Project of Guangxi Higher Education (No. KY2015ZD028), Science Research and Technology Development Project of Qingxiu District of Nanning (No. 2016058), and Lisheng Health Foundation pilotage fund of Peking (No. LHJJ20158126).

The authors declare that they do not have any competing interests.

References

- [1].Brinks R, Hoyer A, Weber S, et al. Age-specific and sex-specific incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus: an estimate from cross-sectional claims data of 2.3 million people in the German statutory health insurance 2002. Lupus Sci Med 2016;3:e000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tiao J, Feng R, Carr K, et al. Using the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria to determine the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74:862–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2677–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Budhoo A, Mody GM, Dubula T, et al. Comparison of ethnicity, gender, age of onset and outcome in South Africans with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2017;26:438–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nikpour M, Bridge JA, Richter S. A systematic review of prevalence, disease characteristics and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in Australia: identifying areas of unmet need. Intern Med J 2014;44:1170–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Al Dhanhani AM, Agarwal M, Othman YS, et al. Incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus among the native Arab population in UAE. Lupus 2017;26:664–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Brunner HI, Gladman DD, Ibañez D, et al. Difference in disease features between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Carreño L, López-Longo FJ, Monteagudo I, et al. Immunological and clinical differences between juvenile and adult onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 1999;8:287–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fatemi A, Matinfar M, Smiley A. Childhood versus adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: long-term outcome and predictors of mortality. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Feng JB, Ni JD, Yao X, et al. Gender and age influence on clinical and laboratory features in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: 1,790 cases. Rheumatol Int 2010;30:1017–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Font J, Cervera R, Espinosa G, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in childhood: analysis of clinical and immunological findings in 34patients and comparison with SLE characteristics in adults. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57:456–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gómez J, Suárez A, López P, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in Asturias, Spain: clinical and serologic features. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:157–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ramírez Gómez LA, Uribe Uribe O, Osio Uribe O, et al. Childhood systemic lupus erythematosus in Latin America. The GLADEL experience in 230 children. Lupus 2008;17:596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gormezano NW, Silva CA, Aikawa NE, et al. Chronic arthritis in systemic lupus erythematosus: distinct features in 336 paediatric and 1830 adult patients. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:227–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gormezano NW, Kern D, Pereira OL, et al. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in systemic lupus erythematosus at diagnosis: differences between pediatric and adult patients. Lupus 2017;26:426–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hersh AO, von Scheven E, Yazdany J, et al. Differences in long-term disease activity and treatment of adult patients with childhood- and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hersh AO, Trupin L, Yazdany J, et al. Childhood-onset disease as a predictor of mortality in an adult cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:1152–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hoffman IE, Lauwerys BR, De Keyser F, et al. Juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: different clinical and serological pattern than adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:412–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Janwityanujit S, Totemchokchyakarn K, Verasertniyom O, et al. Age-related differences on clinical and immunological manifestations of SLE. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 1995;13:145–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Joo YB, Park SY, Won S, et al. Differences in clinical features and mortality between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective single-center study. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1490–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].das Chagas Medeiros MM, Bezerra MC, Braga FN, et al. Clinical and immunological aspects and outcome of a Brazilian cohort of 414 patients with systemiclupus erythematosus (SLE): comparison between childhood-onset, adult-onset, and late-onset SLE. Lupus 2016;25:355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mok CC, Mak A, Chu WP, et al. Long-term survival of southern Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study of all age-groups. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005;84:218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pande I, Sekharan NG, Kailash S, et al. Analysis of clinical and laboratory profile in Indian childhood systemic lupus erythematosus and its comparison with SLE in adults. Lupus 1993;2:83–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rood MJ, ten Cate R, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, et al. Childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical presentation and prognosis in 31 patients. Scand J Rheumatol 1999;28:222–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sassi RH, Hendler JV, Piccoli GF, et al. Age of onset influences on clinical and laboratory profile of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sousa S, Gonçalves MJ, Inês LS, et al. Clinical features and long-term outcomes of systemic lupus erythematosus: comparative data of childhood, adult and late-onset disease in a national register. Rheumatol Int 2016;36:955–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tu YL, Yeh KW, Chen LC, et al. Differences in disease features between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus patients presenting with acute abdominal pain. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011;40:447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tucker LB, Menon S, Schaller JG, et al. Adult- and childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of onset, clinical features, serology, and outcome. Br J Rheumatol 1995;34:866–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tucker LB, Uribe AG, Fernández M, et al. Adolescent onset of lupus results in more aggressive disease and worse outcomes: results of a nested matched case-control study within LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LVII). Lupus 2008;17:314–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. [cited October 19, 2009]. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm [Google Scholar]

- [31].Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Livingston B, Bonner A, Pope J. Differences in autoantibody profiles and disease activity and damage scores between childhood- and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012;42:271–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Medlin JL, Hansen KE, Fitz SR, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cutaneous manifestations in late- versus early-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;45:691–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mina R, Brunner HI. Update on differences between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Papadimitraki ED, Isenberg DA. Childhood- and adult-onset lupus: an update of similarities and differences. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2009;5:391–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lawson EF, Hersh AO, Trupin L, et al. Educational and vocational outcomes of adults with childhood- and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: nine years of follow up. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:717–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fatemi A, Matinfar M, Saber M, et al. The association between initial manifestations of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and the survival. Int J Rheum Dis 2016;19:974–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]