Abstract

Background

Screening older veterans in Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) primary care clinics for risky drinking facilitates early identification and referral to treatment.

Objective

This study compared two behavioral health models, integrated care (a standardized brief alcohol intervention co-located in primary care clinics) and enhanced referral care (referral to specialty mental health or substance abuse clinics), for reducing risky drinking among older male VAMC primary care patients. VAMC variation was also examined.

Method

A secondary analysis of longitudinal data from the Primary Care Research in Substance Abuse and Mental Health for Elderly (PRISM-E) study, a multisite randomized controlled trial, was conducted with a sample of older male veterans (n = 438) who screened positive for risky drinking and were randomly assigned to integrated or enhanced referral care at five VAMCs.

Results

Generalized estimating equations revealed no differences in either behavioral health model for reducing risky drinking at a 6-month follow-up (AOR: 1.46; 95% CI: 0.42–5.07). Older veterans seen at a VAMC providing geriatric primary care and geriatric evaluation and management teams had lower odds of risky drinking (AOR: 0.24; 95% CI: 0.07–0.81) than those seen at a VAMC without geriatric primary care services.

Conclusions

Both integrated and enhanced referral care reduced risky drinking among older male veterans. However, VAMCs providing integrated behavioral health and geriatric specialty care may be more effective in reducing risky drinking than those without these services. Integrating behavioral health into geriatric primary care may be an effective public health approach for reducing risky drinking among older veterans.

Keywords: Older veterans, behavioral medicine, risky drinking, PRISM-E, multisite randomized controlled trial, integrated behavioral health care

Introduction

According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, roughly 40% of adults age 65 or older consume alcohol and approximately 9.2% misuse alcohol (1). Alcohol misuse encompasses the full spectrum of alcohol problems including risky, binge, and problem drinking (2). Risky drinking, which is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and chronic health problems (3–5), is defined as seven or more drinks per week for older adults (6). Binge drinking, which is defined as greater than four drinks for women or five drinks for men daily (7), increases risk for accidental injury (8). Problem drinking is defined as alcohol consumption that results in adverse alcohol-related consequences (9), including legal, medical, or work-related difficulties.

Alcohol misuse among older adults can adversely affect major organ systems, cognition, mental health, and overall well-being (10,11). Age or disease-related changes in major organs (12) can decrease alcohol tolerance, metabolism, distribution, and elimination leading to adverse alcohol-related consequences at lower levels of consumption (13). Common alcohol-related consequences among older adults include falls, memory problems, and adverse alcohol–prescription drug interactions requiring emergency medical attention and/or hospitalization (10,12,14). Interactions between alcohol and prescription drugs, especially those prescribed for diabetes, hypertension, anxiety, and depression, can alter medication effectiveness, lead to misdiagnosis, and result in life-threatening medical complications (10,12). Risky drinking among older adults may contribute to declines in cognition, slowed reaction times, and changes in spatial perception and balance—all posing dangers for older adults who drive or live alone (14).

Alcohol misuse later in life may have a bidirectional relationship with mental illness (15). Age-related physiological changes combined with excessive alcohol consumption exacerbate mental health disorders and may lead to complications with psychotropic medications (12,14,15). Increased alcohol consumption is associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (16). Depressive symptoms in older adults are also associated with alcohol dependence (11).

Older veterans receiving care at Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) may have increased risk for alcohol misuse compared to other older adults. On average, veterans receiving care at VAMCs are sicker, with both increased morbidity and mortality compared to civilians and other veterans (17). Veterans seen at VAMCs reportedly have more medical conditions, outpatient visits, hospital admissions, poorer health, and higher rates of alcohol misuse than the general population (17). Due to military, deployment, and war-related stressors, veterans’ symptoms and diseases may present earlier in life and are often more chronic and severe (18), which raises concerns about veterans consuming alcohol to cope with chronic pain, insomnia, depression, anxiety, or other conditions. With the average veteran being a 64-year-old male and the US veteran population projected to be 15.5 million by 2035 (19,20), screening older veterans for alcohol misuse may improve geriatric practice and patient outcomes in VAMC primary care (12).

Integrating behavioral health into VAMC primary care clinics is an efficient and effective public health approach for screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) of older veterans at risk for alcohol misuse (21,22). Because alcohol misuse can adversely affect patient outcomes, implementing effective alcohol treatments in VAMCs is critical to ensuring quality patient-centered care (23,24). However, VAMC variation has been found in the implementation of integrated mental health care, screening and prevalence of mental health diagnoses, and treatment of chronic diseases among older veterans (25,26). Thus, treatment outcomes for integrated behavioral health care may differ by VAMC.

Behavioral health interventions have been effective in reducing alcohol misuse in older adults as well as younger and older veterans (27,28). Primary Care Research in Substance Abuse and Mental Health for Elderly (PRISME) studies found a reduction in average weekly drinking and binge drinking among older adults receiving both integrated care and enhanced referral care (3,29,30), with no differences by treatment group. Zanjani and colleagues (30) using PRISM-E data from three VAMCs with 12-month follow-up data grouped older male veterans into problematic at-risk drinkers and non-problematic at-risk drinkers. Problematic at-risk drinkers had reductions in average weekly drinking and binge drinking at 3, 6, and 12 months. Non-problematic at-risk drinkers had reductions in weekly drinking at 6 and 12 months, and number of binge episodes only at 6 months. In both VAMCs and community-based primary care clinics (nine sites), Oslin et al. (31) found that both integrated and enhanced referral care reduced risky drinking after 3 and 6 months of treatment, with integrated care resulting in increased treatment engagement defined as at least one visit with a behavioral health provider from the assigned behavioral health model.

Extending PRISM-E findings, this study examined (1) the main effects of treatment and VAMC site on risky drinking and (2) differences in change over time between treatment groups. This study differed from prior PRISM-E studies by comparing integrated care and enhanced referral care for reducing risky drinking among older male veterans seen in five large, demographically diverse VAMCs over 6 months. Other PRISM-E studies used only one (32) or three (30) VAMCs, or a combination of VAMCs and community-based primary care clinics (31), whereas the current study uses a sample of older male VAMC primary care patients whose morbidity, mortality, and eligibility for health care differ from the general population receiving care in community-based primary care clinics. No other PRISM-E study examined risky drinking outcomes across all five VAMCs. The Andersen–Newman Model of Health Services Utilization (33) suggests that the organization and structure of health-care systems determine access, provision, and volume of health services received by patients. Thus, we hypothesized that risky drinking outcomes would vary by VAMC.

Methods

This study was a secondary analysis of longitudinal data from PRISM-E, a multisite randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing two behavioral health models among primary care patients aged 65 and older who screened positive for depression, anxiety, and/or risky drinking in civilian and VAMC primary care clinics. Older adults were randomized to either integrated or enhanced referral behavioral health care using a permuted blocks design stratified by site, major diagnostic category, and age group (65–74 years or ≥75 years). See Levkoff et al. (34) for a detailed description of PRISM-E. Given PRISM-E’s main goal was to identify the relative effectiveness of integrated and enhanced referral care on reducing behavioral health problems, there was no usual care or control group (34). Institutional review board approval was received from the University of South Carolina.

Sample

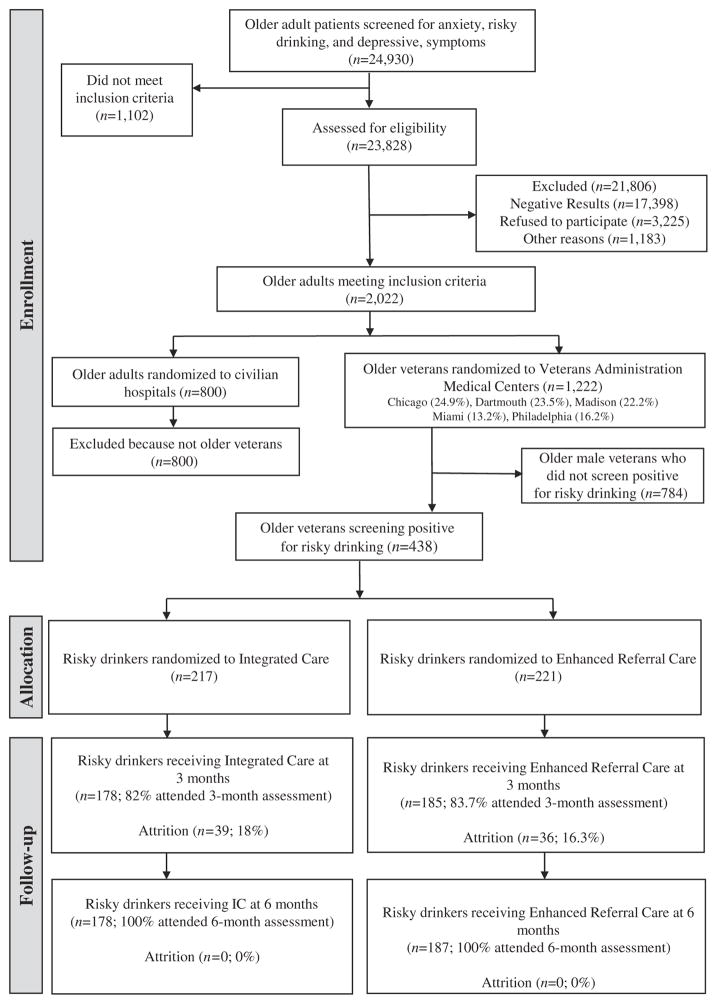

For this study, the intention-to-treat sample included older male veterans seen in primary care clinics who screened positive for risky drinking (n = 438) at five VAMCs located in Chicago, Dartmouth, Madison, Miami, and Philadelphia. Two VAMC sites had well-established integrated care or enhanced referral care models prior to the beginning of PRISM-E and were already assigning patients to these treatments by social security number (SSN; even or odd) and continued using this process throughout the study. Analysis of sociodemographic characteristics of these older male veterans revealed that the SSN method was comparable to randomization (34). Figure 1 displays a flow diagram of randomization of older male veterans who screened positive for risky drinking to integrated and enhanced referral care in the current study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of randomization of older male veterans to behavioral health models.

Behavioral health treatment models

Type of behavioral health model, integrated care or enhanced referral care, was the primary independent variable. Both integrated and enhanced referral care models were offered at all five VAMCs for 6 months prior to randomization to ensure full implementation of the models prior to study initiation. Integrated care included (1) mental health and/or substance abuse (behavioral health) services co-located in primary care clinics, (2) communication between the primary care provider (PCP) and behavioral health provider about the behavioral health evaluation and treatment plan, and (3) availability of a standardized brief alcohol intervention consistent with the recommendations of the Treatment Improvement Protocol Series (TIP #26), Substance Abuse Among Older Adults (35) that included up to three 20–30-min face-to-face counseling sessions addressing reasons for drinking, drinking cues, reasons to cut down or quit, and a drinking agreement in the form of a prescription (31). Integrated care providers at each site were licensed behavioral health professionals, including psychiatrists, clinical social workers, nurses, and case managers. There were varying levels of expertise in substance abuse treatment, but each behavioral health provider received a brief alcohol intervention training by two PRISM-E investigators during a 4-hour interactive session with new staff being trained by on-site personnel. Veterans with both risky drinking and anxiety or clinically significant depressive symptoms received treatment for comorbid conditions simultaneously (31). Prevalence of comorbid conditions included risky drinking and depressive symptoms (n = 56), risky drinking and anxiety (n = 28), and risky drinking, depressive symptoms, and anxiety (n = 55).

Enhanced referral care included (1) behavioral health evaluation and treatment by licensed behavioral health providers at a location designated as a mental health or substance abuse clinic (i.e., not co-located with VAMC primary care clinics), (2) coordinated follow-up with the primary care clinic if the patient missed the first scheduled behavioral health appointment, and (3) transportation assistance to behavioral health appointments. To ensure implementation fidelity, enhanced referral care sites had to meet specific criteria to facilitate adequate and timely behavioral health care, including (1) a clearly defined referral process from PCP to behavioral health providers, (2) methods for patients to make an appointment at the specialty clinic, (3) an initial appointment for patients within 4 weeks of randomization, (4) contact with patients if they missed appointments after the initial evaluation, and (5) a process for emergency or urgent consults.

Measures

Risky drinking

The primary dependent variable, risky drinking, was measured at baseline, 3, and 6 months across all VAMCs. Risky drinking was assessed with the Alcohol Quantity/Frequency Scale (36) and was defined as consumption of more than seven drinks weekly or more than four drinks daily more than twice in a 3-month period (7,34), given that some veterans may underreport their drinking. Risky drinking was measured as a dichotomous (yes/no) variable.

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was measured with the Alcohol Quantity/Frequency Scale (36) and assessed the number of drinks in the past week and number of binge episodes in the past 3 months. Binge drinking was defined as more than five drinks daily. Number of drinks and binge drinking was measured at baseline, 3, and 6 months.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (37), which is a self-report measure of depressive symptoms with a cut point of ≥16 indicating the presence of clinically significant depressive symptoms. Higher scores indicated more severe depressive symptomatology. The CES-D has good psychometric properties in healthy and medically ill older adults (38,39). Internal consistency reliability for this study was 0.76.

Anxiety

Anxiety symptoms were measured with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (40), which is a 21-item self-report inventory assessing the severity of anxiety symptoms in psychiatric populations. Scores range from 0 to 63 with higher scores indicating more severe levels of anxiety (41). Cut points include 0–9 for minimal, 10–16 for mild, 17–29 for moderate, and 30–63 for severe anxiety (42). The BAI has demonstrated high internal consistency and test–retest reliability (40,42,43), and psychometric properties have demonstrated its utility as a brief screening instrument for older psychiatric patients (41). Internal consistency reliability for this study was 0.96.

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographics included age in years, race (black, white, other), employment status (employed = yes, unemployed = no), Medicare (yes/no), Medicaid (yes/no), VA benefits (yes/no), and VA percent eligibility (100%, 99–50%, <50%). VAMC site was recorded by interviewers at each location, which included Chicago, Dartmouth, Madison, Miami, and Philadelphia.

Treatment Engagement

The number of mental health and substance abuse visits measured treatment engagement. Mental health visits for anxiety and depression and substance abuse visits for risky drinking were self-reported for the prior 3 months at 3 and 6-month follow-up and measured as a count variable. Three brief alcohol intervention sessions were the recommended number of sessions for older male veterans assigned to each behavioral health model (31).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables by total sample and by behavioral health model. For categorical variables, univariate analyses included frequency distributions, whereas measures of central tendency and dispersion were computed for continuous variables. Correlations and chi-square tests examined differences in sociodemographics, alcohol consumption, and treatment engagement by behavioral health model. Treatment engagement was also examined by behavioral health model across VAMC sites. Prevalence of risky drinking was estimated by behavioral health model at baseline, 3, and 6 months. For depressive symptoms, both the cut point and continuous score were used in descriptive statistics, but in multivariate analyses, only the continuous variable was used. Because no significant differences were found in sociodemographics and attrition across behavioral health models, missing data were not imputed.

Longitudinal analyses were conducted for risky drinking (baseline, 3, and 6 months) using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to model the probability of risky drinking (main effect), VAMC site variation over time (VAMC site × time, treatment group × VAMC site), and change in risky drinking over time (treatment group × time, treatment group × VAMC site × time). Risky drinking was tested as a discrete outcome (yes/no).

Four exploratory GEE models were estimated without covariates to test the main effects of treatment, time, and VAMC site, as well as treatment × time, VAMC site × time, treatment × VAMC site, and treatment × VAMC site × time interactions for risky drinking. All interactions were nonsignificant and excluded from the final model for parsimony with the exception of the treatment × time interaction. Final GEE models with covariates for risky drinking included the main effects of treatment, VAMC site, and time, and the treatment × time interaction. Identities of VAMC sites were masked in results to maintain confidentiality. Final models are reported in Table 3. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.

Table 3.

Generalized estimating equations model predicting the effectiveness of behavioral health models on risky drinking.

| Variables | Risky drinkinga

|

|

|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | |

| Integrated model (ref = enhanced) | 1.46 | 0.42–5.07 |

| Depressive Symptoms b* (ref = no) | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 |

| Black (ref = White) | 0.62 | 0.22–1.76 |

| Other | 0.76 | 0.12–4.81 |

| Employment (ref = no) | 1.61 | 0.68–3.80 |

| Time 6M (ref = 3M) | 0.72 | 0.45–1.17 |

| VAMC 2 (ref = VAMC 1) | 1.05 | 0.30–3.60 |

| VAMC 3 | 0.89 | 0.26–3.09 |

| VAMC 4* | 0.24 | 0.07–0.81 |

| VAMC 5 | 1.40 | 0.43–4.57 |

| Integrated Model × 6M | 0.86 | 0.43–1.72 |

AOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence intervals; M: months.

Dichotomous measure of risky drinking defined as more than seven drinks weekly or more than four drinks daily more than twice in a 3-month period.

Depressive symptoms measured as a continuous score on the Center for Epidemiologic Scale-Depression (CES-D; Radloff, 1977).

p < 0.05.

Results

Figure 1 reports attrition by behavioral health model. Attrition was determined by identifying older veterans not receiving the brief alcohol intervention per their assigned behavioral health model (i.e., integrated care or enhanced referral care) at 3-month and/or 6-month follow-up. There was no attrition from 3-month to 6-month follow-up for both behavioral health models (see Figure 1).

Sociodemographics, alcohol consumption, and treatment engagement

Table 1 reports sociodemographics, alcohol consumption, and treatment engagement by total sample and behavioral health model. Male veterans (n = 438) aged 65–88 years old (Mage = 71.8, sd = 5.0) were randomized to integrated (n = 217; 49.5%) or enhanced referral (n = 221; 50.5%) behavioral health models at Chicago, Dartmouth, Madison, Miami, and Philadelphia VAMCs. The majority of veterans were either White (72.3%) or African-American (26.0%), unemployed (78.3%), receiving Medicare (n = 371; 85.5%), and receiving VA benefits (n = 313; 73.1%) with a less than 50% disability rating (71.2%). Almost one-third (31.7%) did not have a high school diploma, 28.7% had a high school diploma, and 39.7% had completed some college or had a college degree. Only 6.2% received Medicaid. On average, older veterans had mild anxiety symptoms, but an overwhelming majority (87.2%) had clinically significant depressive symptoms. There were no significant differences in baseline socio-demographic characteristics by behavioral health model.

Table 1.

Sociodemographics, alcohol consumption, and treatment engagement among older male veterans by behavioral health treatment model.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 438) n (% of total) |

Behavioral health models

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated (n = 217) n (% of total) |

Enhanced referral (n = 221) n (% of total) |

||

| Age (m, sd) | 71.9 (5.0) | 72.2 (5.0) | 71.8 (4.9) |

| Race | |||

| African-American | 89 (26.0) | 48 (28.2) | 41 (23.7) |

| White | 248 (72.3) | 119 (70.0) | 129 (74.6) |

| Other | 6 (1.7) | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.7) |

| Education | |||

| Less than HS diploma | 138 (31.6) | 77 (35.5) | 61 (27.9) |

| HS diploma/GED | 125 (28.7) | 64 (29.5) | 61 (27.9) |

| Some college or more | 173 (39.7) | 76 (35.0) | 97 (44.2) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/Partnered | 235 (53.8) | 115 (53.0) | 120 (54.6) |

| Divorced | 74 (16.9) | 31 (14.3) | 43 (19.6) |

| Separated | 20 (4.6) | 11 (5.1) | 9 (4.1) |

| Widowed | 85 (19.5) | 48 (22.1) | 37 (16.8) |

| Never married | 23 (5.3) | 12 (5.5) | 11 (5.0) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 95 (21.7) | 45 (20.7) | 50 (22.6) |

| Unemployed | 343 (78.3) | 172 (79.3) | 171 (77.4) |

| VA benefits (yes) | 313 (73.1) | 157 (74.4) | 156 (71.9) |

| VA disability % | |||

| 100% | 27 (15.9) | 13 (16.5) | 14 (15.4) |

| 50–99% | 22 (12.9) | 9 (11.4) | 13 (14.3) |

| <50% | 121 (71.2) | 57 (72.2) | 64 (70.3) |

| Medicare (yes) | 371 (85.5) | 179 (83.6) | 192 (87.3) |

| Medicaid (yes) | 26 (6.1) | 17 (8.0) | 9 (4.3) |

| Anxietya (m, sd) | 2.6 (7.5) | 2.5 (7.4) | 2.6 (7.7) |

| CES-D scoreb (m, sd) | 15.7 (7.0) | 15.7 (7.0) | 15.7 (7.0) |

| CES-D score ≥16b (yes) | 382 (87.2) | 187 (86.2) | 195 (88.2) |

| Number of drinks, past week, 3Mc (m, sd) | 11.7 (11.4) | 11.8 (12.4) | 11.6 (10.9) |

| Number of drinks, past week, 6Mc (m, sd) | 11.4 (11.4) | 11.7 (12.6) | 11.0 (10.1) |

| Number of binges, past 3Md (m, sd) | 22.6 (29.7) | 21.6 (29.0) | 23.5 (30.5) |

| Number of binges, past 3M, 3Md (m, sd) | 12.9 (24.8) | 10.3 (21.0) | 15.3 (27.8) |

| Number of binges, past 3M, 6Md (m, sd) | 12.9 (25.4) | 12.4 (25.3) | 13.4 (25.5) |

| Number of MHSA visits past 3M, 3Me (m, sd) | 1.7 (2.0) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.7 (2.0) |

| Number of MHSA visits past 3M, 6Me (m, sd) | 3.5 (10.4) | 1.0 (1.7) | 3.7 (11.0) |

| VAMC site | |||

| VAMC 1 | 109 (24.9) | 60 (27.7) | 49 (22.2) |

| VAMC 2 | 103 (23.5) | 50 (23.0) | 53 (24.0) |

| VAMC 3 | 97 (22.2) | 44 (20.3) | 53 (24.0) |

| VAMC 4 | 58 (13.2) | 28 (12.9) | 30 (13.6) |

| VAMC 5 | 71 (16.2) | 35 (16.1) | 36 (16.3) |

Other: Asian, Hispanic/Latino, Other/Mixed; HS: high school; GED: general educational development; VA: Veterans Affairs; M: months; MHSA: mental health/substance abuse; VAMC: Veterans Administration Medical Center. Totals may not equal 100 because of missing values.

Anxiety measured as a severity score with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI, Beck et al., 1988).

Depressive symptoms measured as a continuous score and cut point of ≥16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Scale-Depression (CES-D; Radloff, 1977).

Number of drinks measured by the Alcohol Quantity/Frequency Scale (Werch, 1989).

Binges defined as four or more drinks in 1 day and measured by the Alcohol Quantity/Frequency Scale (Werch, 1989).

Data collected only at 3 and 6 months.

High levels of alcohol consumption were found among older male veterans who screened positive for risky drinking. At baseline, older veterans reported an average of 17.9 drinks weekly and 22.6 binge episodes over the past 3 months, which was consistent across behavioral health models. The number of drinks and binge episodes weekly decreased from baseline to 6-month follow-up. The number of past week drinks and binge episodes did not differ over time by behavioral health model. The average number of mental health or substance abuse visits over 3 months was 1.7 visits at 3-month follow-up and 3.5 visits at 6-month follow-up.

Unadjusted prevalence of risky drinking

The unadjusted prevalence of risky drinking revealed that risky drinking decreased among older veterans assigned to both behavioral health models over time. For integrated care, risky drinking decreased from 100% to 61.8% at 3 months and from 61.8% to 52.8% at 6 months. For enhanced referral care, risky drinking decreased from 100% to 59.5% at 3 months and from 59.5% to 52.9% at 6 months.

Treatment engagement across VAMCs

Table 2 reports treatment engagement by behavioral health model across VAMC sites. For both integrated and enhanced referral care, the majority of older veterans at each VAMC had less than the recommended three behavioral health visits at 3- and 6-month follow-up. Overall, 9.2% (n = 20) and 3.2% (n = 7) of older veterans assigned to integrated care and 5.9% (n = 13) and 3.6% (n = 8) of older veterans assigned to enhanced referral care reported receiving three or more behavioral health visits at 3- and 6-month follow-up, respectively. Only 1.8% (n = 4) of older veterans assigned to integrated care and 1.4% (n = 3) of older veterans assigned to enhanced referral care reported receiving three or more behavioral health visits at both 3- and 6-month follow-up. Across all VAMCs, 12.4% (n = 27; range by VAMC: 0–16.7%) of older veterans assigned to integrated care and 9.5% (n = 21; range by VAMC: 0–19.4%) of those assigned to enhanced referral care reported receiving three or more behavioral health visits from baseline to 6-month follow-up. Of all older veterans in the study (N = 438), only 11% (n = 48) reported receiving three or more behavioral health visits from baseline to 6-month follow-up.

Table 2.

Treatment engagement by behavioral health model across Veterans Affairs Medical Centers.

| Characteristicsa | Behavioral health models (N = 438)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated care (n = 217)

|

Enhanced referral care (n = 221)

|

|||||||||

| VAMC 1 (n = 60) | VAMC 2 (n = 50) | VAMC 3 (n = 44) | VAMC 4 (n = 28) | VAMC 5 (n = 35) | VAMC 1 (n = 49) | VAMC 2 (n = 53) | VAMC 3 (n = 53) | VAMC 4 (n = 30) | VAMC 5 (n = 36) | |

| Number of MHSA visits past 3M, 3M (m, sd) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.4 (2.1) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.1 (0.3) |

| Number of MHSA visits past 3M, 6M (m, sd) | 2.2 (1.3) | 1.1 (3.1) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.0 (0.7) | 1.3 (1.0) | 3.2 (3.3) |

| Number of MHSA visits past 3M, 3Mb(% of VAMC) | ||||||||||

| 0 MHSA visits | 2 (3.3) | 7 (14.0) | 12 (27.3) | 9 (32.1) | 3 (8.6) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (9.4) | 4 (13.3) | 0 (0) |

| 1–2 MHSA visits | 16 (26.7) | 20 (40.0) | 11 (25.0) | 7 (25.0) | 10 (28.6) | 5 (10.2) | 11 (20.8) | 13 (24.5) | 10 (33.3) | 10 (27.8) |

| ≥3 MHSA visits | 10 (16.7) | 3 (6.0) | 2 (4.5) | 1 (3.6) | 4 (11.4) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (10.0) | 7 (19.4) |

| Number of MHSA visits past 3M, 6Mb(% of VAMC) | ||||||||||

| 0 MHSA visits | 7 (11.7) | 17 (34.0) | 14 (31.8) | 6 (21.4) | 5 (14.3) | 4 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 9 (17.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 1–2 MHSA visits | 16 (26.7) | 1 (2.0) | 28 (31.8) | 10 (35.7) | 8 (22.9) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (3.8) | 10 (18.9) | 5 (16.7) | 1 (2.8) |

| ≥3 MHSA visits | 4 (6.7) | 3 (6.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (3.3) | 3 (8.3) |

VAMC: Veterans Affairs Medical Center; M: months. Identities of VAMCs were masked to maintain confidentiality.

Data collected only at 3 and 6 months.

Number of MHSA visits were self-reported for past 3 months at 3- and 6-month follow-up. Totals not equal to 100% due to missing data. Differences not examined due to low cell counts.

GEEs of behavioral health models and risky drinking

Table 3 reports the final GEE model with covariates for risky drinking which examined the main effects of treatment, time, and VAMC site, as well as the interaction effect of treatment × time. The main effects of treatment and time were nonsignificant as well as the treatment × time interaction. However, the main effects of VAMC site and depressive symptoms were significant. Older male veterans seen at VAMC 4 had lower odds of risky drinking (AOR: 0.24; 95% CI: 0.07–0.81) compared to those seen at VAMC 1. Older veterans with more severe depressive symptoms had greater odds of risky drinking (AOR: 1.03; 95% CI: 1.01–1.05) compared to those with less severe depressive symptoms. As depressive symptoms increased, older male veterans were more likely to engage in risky drinking.

Discussion

This study compared the effectiveness of integrated care behavioral health models in the reduction of risky drinking and variation by VAMC among older male veteran primary care patients. No differences in treatment effectiveness for reducing risky drinking were found between integrated and enhanced referral care models at 3 and 6 months. These findings are consistent with previous PRISM-E studies on civilian older adults and a combination of older adults seen at civilian community-based primary care clinics and VAMCs (3,31,32). The reduction in risky drinking also differed by VAMC, which has clinical implications for the integration of behavioral health in geriatric primary care.

In addition to prior PRISM-E studies, our findings are also consistent with other RCTs of primary-care-based interventions to reduce risky drinking in older adults. Unlike PRISM-E, which compared integrated and enhanced referral care—neither of which were usual care, these RCTs compared various intervention models with usual care (44–47). In all trials, there were significantly higher reductions in alcohol misuse for integrated care compared to usual care. In Project SHARE (44), a 12-month educational intervention reduced risky drinking for older adults compared to a usual care control arm. In Project GOAL (47), a brief physician advice intervention with follow-up calls from nurses reduced 7-day alcohol consumption and frequency of binge episodes compared to a usual care control arm at 12-month follow-up, a reduction which persisted at 24-month follow-up (46). In the Healthy Living as You Age (HLAYA) (45) intervention, which included personalized reports and physician feedback along with health educator calls at 2, 4, and 8 weeks, alcohol consumption in the intervention group decreased more than in the usual care group at 12-month follow-up. Thus, our findings build upon evidence supporting the integration of behavioral health into primary care and replicated these findings among older male veterans seen in VAMC primary care clinics.

Consistent with the Anderson–Newman model (33), the reduction in risky drinking differed by VAMC. Prior VA research suggests that organizational factors can present both barriers and facilitators to quality care, diffusion of evidence-based treatments, treatment effectiveness, and patient outcomes (48). In this study, four out of five VAMCs offered geriatric specialty services which included geriatric primary care, extended care, geriatric evaluation and management (GEM) teams, home-based primary care, and/or care coordination—all of which may influence health services utilization and patient outcomes among older male veterans. Older veterans seen at one VAMC with comprehensive geriatric services, including geriatric primary care, extended care, care coordination, and an interdisciplinary GEM (49) team, were significantly less likely to be risky drinkers than those seen at a VAMC without geriatric primary care during the study period. Although the other three VAMCs with geriatric services did not differ from the VAMC without geriatric primary care in the reduction of risky drinking, those VAMCs did not have GEM. Compared to usual care, GEM teams at VAMCs have been found effective in improving number of clinic visits, depressive symptoms, social activity, pain, mental health, and general well-being among older veterans (49,50). However, limited evidence exists on the effectiveness of GEM on risky drinking among older veterans. Our findings suggest that integrated behavioral health and GEM may be promising public health approaches for reducing risky drinking among older veterans. Future research should examine the combined effectiveness of integrated behavioral health and comprehensive geriatric services in reducing risky drinking among older veterans.

Three VAMCs with geriatric services did not significantly differ from a VAMC without geriatric primary care in reducing risky drinking among older veterans. Perhaps factors unobserved in our study such as variations in treatment fidelity, patient–provider ratios, urban and rural locale, number of participants residing in remote areas, specific geriatric services, and attrition across sites partially accounted for our nonsignificant findings. Aging-in-place services and technologies (51) in local communities and civilian health systems within and between Veteran Integrated System Networks (VISN) may also differ, which are other system-level factors that may result in VAMC site variation. Older male veterans may also receive additional health services in civilian health systems because they are dual health care users (i.e., VA and Medicare and/or Medicaid coverage)—a factor which may also influence patient outcomes and vary by VISN and VAMC. Because VAMC primary care protocols and patients vary by site (25,26), future RCTs should assess whether integrated or enhanced referral care is most effective after controlling for patient, provider, VISN, and VAMC characteristics using multilevel modeling.

Our study has noteworthy strengths that include a multisite RCT that allows for the prediction of longitudinal outcomes. Older male veterans in this study were also seen in primary care clinics at five large, demographically diverse VAMCs from multiple VISNs. Limitations include attrition bias. In a previous PRISM-E study, Oslin et al. (31) found low integrated care treatment engagement with 43% of patients receiving at least one brief alcohol intervention session and only 9% receiving the recommended three sessions. Overall, only 11% of older veterans assigned to either integrated or enhanced referral care in this study reported receiving three or more behavioral health visits between baseline and 6-month follow-up. Thus, attrition may have reduced statistical power to detect treatment and interaction effects. The lack of a no-treatment control group limits our ability to know whether risky drinking would have declined in older veterans over time without treatment. Objective measures of risky drinking and treatment engagement via a medical chart review could have reduced recall bias resulting from self-reported data. Risky drinking in older male veterans may also be underestimated in this study because older male veterans may underreport alcohol use (52). Older male veterans seen in VAMC primary care may also be sicker (17) and thus may consume more alcohol to cope with medical and psychological symptoms. Findings may also not generalize to older women veterans. Future research in VAMC primary care clinics should include a veteran population that has more gender, racial, ethnic, and war cohort diversity.

The PRISM-E study protocol was consistent with screening and brief intervention recommendations of the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders (53). Thus, our findings have implications for prevention of risky drinking among older veterans and support current VA initiatives to increase access to quality care by providing SBIRT in primary care to identify risky drinking in veterans (54–56). Early identification of risky drinking may reduce functional impairment among veterans and decrease their need for supportive services. A brief alcohol intervention for risky drinking can also decrease the likelihood of adverse alcohol–prescription drug interactions (57) and facilitate better patient outcomes and healthy aging among older veterans.

Findings from the current study have implications for future research, professional training, and health policy. Assessment of motivation for change prior to and during treatment could provide additional evidence about the effectiveness of both integrated and enhanced referral care, as well as the identification of relapse risk factors and trajectories. Perhaps the use of motivational interviewing with both integrated and enhanced referral care models as recommended by the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders (53) would increase treatment engagement over time and build upon evidence about the effectiveness of these behavioral health models. Because women are the fastest growing veteran group, future RCTs should examine the effectiveness of integrated behavioral health in VAMC primary care on risky drinking among women veterans. Organizational and translational research are needed to identify associations between organizational characteristics, diffusion of integrated behavioral health, and treatment effectiveness, which could facilitate the identification of key VAMC characteristics associated with patient outcomes and system-level changes that promote translation of evidence-based treatments.

Though more research is needed, both integrated and enhanced referral care models show promise as interventions that may reduce risky drinking in older male veterans. Both have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality and promote healthy aging in veterans. Professional training in integrated and enhanced referral care could further enhance treatment effectiveness and physician training programs in addiction medicine (58,59). Given that both integrated and enhanced referral care models are interdisciplinary, training is also needed for allied health professionals such as nurses, psychologists, and social workers. Professional behavioral health training focusing on veteran populations could also build the behavioral health workforce in civilian communities (60,61). As the veteran population ages and a new generation of veterans becomes eligible for VA health care, we need effective, quality behavioral health care for those who defended our nation’s freedoms.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant number K01DA037412; PI: Nikki R. Wooten, PhD). PRISM-E was a collaborative research study funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), with additional support and collaboration from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA), and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

Dr. Wooten is a lieutenant colonel in the US Army Reserves with over 28 years of military service but did not complete this study as a part of her official military duties. The opinions herein are solely the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the US Department of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the Health Resources Services Administration, the US Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, or any entity of the federal government.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] Results from the 2010 national survey on drug use and health: summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: 2011. NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 114658. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonas D, Garbutt J, Amick H, Brown J, Brownley K, Council C, Viera A, et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U. S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:645–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, Ware JH, Miles KM, Arean PA, Chen H, et al. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1455–1462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin JC, Karno MP, Barry KL, Blow FC, Davis JW, Tang L, Moore AA. Determinants of early reductions in drinking in older at-risk drinkers participating in the intervention arm of a trial to reduce at-risk drinking in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:557–568. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA] [last accessed 13 Jan 2015];Older Adults. 2015 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/

- 7.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA] Rethinking drinking. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saitz R. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:596–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heuberger RA. Alcohol and the older adult: a comprehensive review. J Nutr Elder. 2009;28:203–235. doi: 10.1080/01639360903140106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aira M, Hartikainen S, Sulkava R. Community prevalence of alcohol use and concomitant use of medication—a source of possible risk in the elderly aged 75 and older? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:680–685. doi: 10.1002/gps.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blow FC, Serras AM, Barry KL. Late-life depression and alcoholism. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;1:14–19. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blow FC, Barry KL. Alcohol and substance misuse in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:310–319. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meier P, Seitz HK. Age, alcohol metabolism and liver disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;11:21–26. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f30564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuccalà G, Onder G, Pedone C, Cesari M, Landi F, Bernabei R, Cocchi A, et al. Dose-related impact of alcohol consumption on cognitive function in advanced age: results of a multicenter survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1743–1748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oslin DW. Alcohol use in late life: disability and comorbidity. J Psychiatry Neurol. 2000;13:134–140. doi: 10.1177/089198870001300307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rinfrette ES. Treatment of anxiety, depression, and alcohol disorders in the elderly: social work collaboration in primary care. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2009;6:79–91. doi: 10.1080/15433710802633569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agha Z, Lofgren R, VanRuiswyk J, Layde P. Are patients at veterans affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252–3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durai UNB, Chopra MP, Coakley E, et al. Exposure to trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in older veterans attending primary care: comorbid conditions and self-rated health status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1087–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo L. Affairs USDoV, editor. Veteran population projection model: VetPop2014. Washington, DC: National Center for Veterans Statistics and Analysis, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2015. Retrieved at https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Social Work Policy Institute. Enhancing the well-being of America’s veterans and their families. Washington, DC: National Association of Social Workers; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Post EP, Metzger M, Dumas P, Lehmann L. Integrating mental health into primary care within the Veterans Health Administration. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:83. doi: 10.1037/a0020130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeiss AM, Karlin BE. Integrating mental health and primary care services in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15:73–78. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorocco KH, Ferrell SW. Alcohol use among older adults. J Gen Psychol. 2006;133:453–467. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.453-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:828–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gellad WF, Good CB, Amuan ME, Marcum ZA, Hanlon JTV. Facility-level variation in potentially inappropriate prescribing for older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1222–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valenstein M, Taylor KK, Austin K, Kales HC, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Benzodiazepine use among depressed patients treated in mental health settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:654–661. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemke S, Moos RH. Treatment and outcomes of older patients with alcohol use disorders in community residential programs. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:219. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemke S, Moos RH. Outcomes at 1 and 5 years for older patients with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oslin DW, Ross J, Sayers S, Murphy J, Kane V, Katz IR. Screening, assessment, and management of depression in VA primary care clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanjani F, Mavandadi S, TenHave T, Katz I, Durai NB, Krahn D, Llorente M, et al. Longitudinal course of substance treatment benefits in older male veteran at-risk drinkers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:98–106. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oslin DW, Grantham S, Coakley E, Maxwell J, Miles K, Ware J, Blow FC, et al. Prism-E: comparison of integrated care and enhanced specialty referral in managing at-risk alcohol use. Psych Serv. 2006;57:954–958. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.7.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zanjani F, Zubritsky C, Mullahy M, Oslin D. Predictors of adherence within an intervention research study of the at-risk older drinker: PRISM-E. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;19:231–238. doi: 10.1177/0891988706292757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005;83 Online only. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levkoff S, Chen H, Coakley E, Herr EC, Oslin DW, Katz I, Bartels SJ, et al. Design and sample characteristics of the PRISM-E multisite randomized trial to improve behavioral health care for the elderly. J Aging Health. 2004;16:3–27. doi: 10.1177/0898264303260390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Substance abuse for older adults. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1998. DHHS #SMA 98–3179. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werch C. Quantity-frequency and diary measures of alcohol consumption for elderly drinkers. Subst Use Misuse. 1989;24:859–865. doi: 10.3109/10826088909047316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turvey C, Wallace R, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:139–148. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kabacoff RI, Segal DL, Hersen M, Van Hasselt VB. Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the state-trait anxiety inventory with older adult psychiatric outpatients. J Anxiety Disord. 1997;11:33–47. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(96)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fydrich T, Dowdall D, Chambless DL. Reliability and validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory. J Anxiety Disord. 1992;6:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steer RA, Ranieri WF, Beck AT, Clark DA. Further evidence for the validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory with psychiatric outpatients. J Anxiety Disord. 1993;7:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ettner SL, Xu H, Duru OK, Ang A, Tseng C, Tallen L, Barnes A, et al. The effect of an educational intervention on alcohol consumption, at-risk drinking, and health care utilization in older adults: the project SHARE study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:447. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore AA, Blow FC, Hoffing M, Welgreen S, Davis JW, Lin JC, Ramirez KD, et al. Primary care-based intervention to reduce at-risk drinking in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2011;106:111–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.French MT, Mundt MP, Roebuck MC, Manwell LB, Barry KL. Brief physician advice for problem drinking among older adults: an economic analysis of costs and benefits. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:389–394. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleming MF, Manwell LB, Barry KL, Adams W, Stauffacher EA. Brief physician advice for alcohol problems in older adults: a randomized community-based trial. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:378–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oishi S, Marshall N, Hamilton AB, Yano EM, Lerner B, Scheuner MT. Assessing multilevel determinants of adoption and implementation of genomic medicine: an organizational mixed-methods approach. Genet Med. 2015;17:919–926. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burns R, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Graney MJ. Interdisciplinary geriatric primary care evaluation and management: two-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rao AV, Hsieh F, Feussner JR, Cohen HJ. Geriatric evaluation and management units in the care of the frail elderly cancer patient. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:798–803. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenfield EA. Using ecological frameworks to advance a field of research, practice, and policy on aging-in-place initiatives. Gerontologist. 2012;52:1–12. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Livingston M, Callinan S. Underreporting in alcohol surveys: whose drinking is underestimated? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs & U.S. Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of substance use disorders. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/ [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wray LO, Szymanski BR, Kearney LK, McCarthy JF. Implementation of primary care-mental health integration services in the Veterans Health Administration: program activity and associations with engagement in specialty mental health services. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19:105–116. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zivin K, Pfeiffer PN, Szymanski BR, Valenstein M, Post EP, Miller EM, McCarthy JF. Initiation of primary care —mental health integration programs in the VA health system: associations with psychiatric diagnoses in primary care. Med care. 2010;48:843–851. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e5792b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson-Lawrence V, Zivin K, Szymanski BR, Pfeiffer PN, McCarthy JF. VA primary care–mental health integration: patient characteristics and receipt of mental health services, 2008–2010. Psych Serv. 2012;63:1137–1141. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore AA, Whiteman EJ, Ward KT. Risks of combined alcohol/medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC. Alcohol screening and brief intervention: dissemination strategies for medical practice and public health. Addiction. 2000;95:677–686. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9556773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gordon AJ, Alford DP. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) curricular innovations: addressing a training gap. SubstAbuse. 2012;33:227–230. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.640156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wooten NR. Military social work: opportunities and challenges for social work education. J Soc Work Educ. 2015;51:S6–S25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors. Addressing the substance use disorder service needs of returning veterans and their families: the training needs of state alcohol and other drug agencies and providers. Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 2009. [Google Scholar]